Submitted:

29 March 2025

Posted:

31 March 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

2.2. Solution Preparation

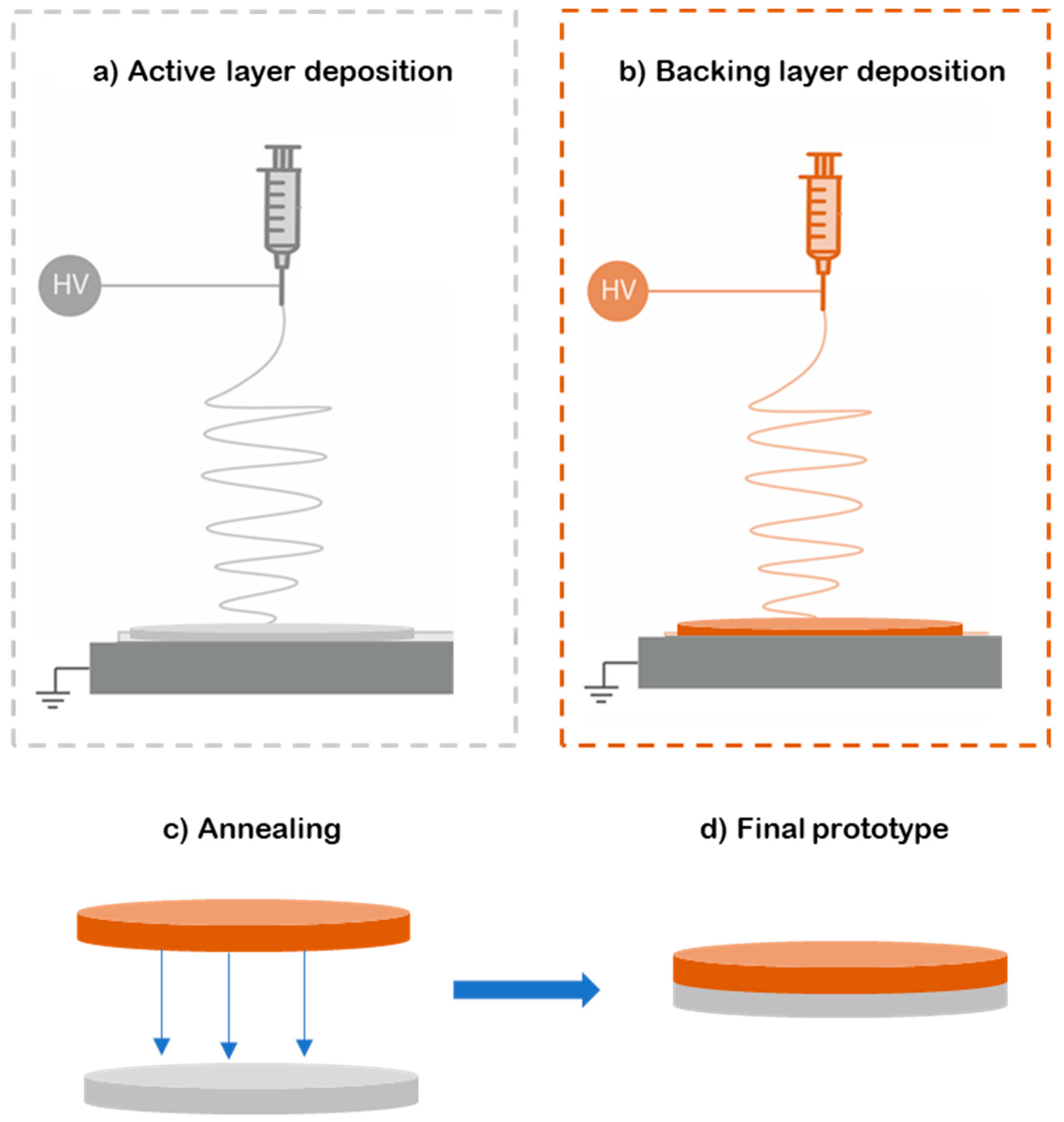

2.3. Electrospinning

2.4. Human Skin Sample Preparation

2.5. Characterization

2.5.1. Fibre Morphology (SEM)

2.5.2. In-Vitro Release Assessment of Caffeine Patches Using Franz Diffusion Cell

- Fourier transform infrared (FTIR)

2.5.3. Differential Scanning Calorimetry (DSC)

2.5.4. Wide-Angle X-Ray Scattering (WAXS)

2.5.5. Kinetic Modelling of Ex-Vivo Human Skin Permeation

3. Results and Discussion

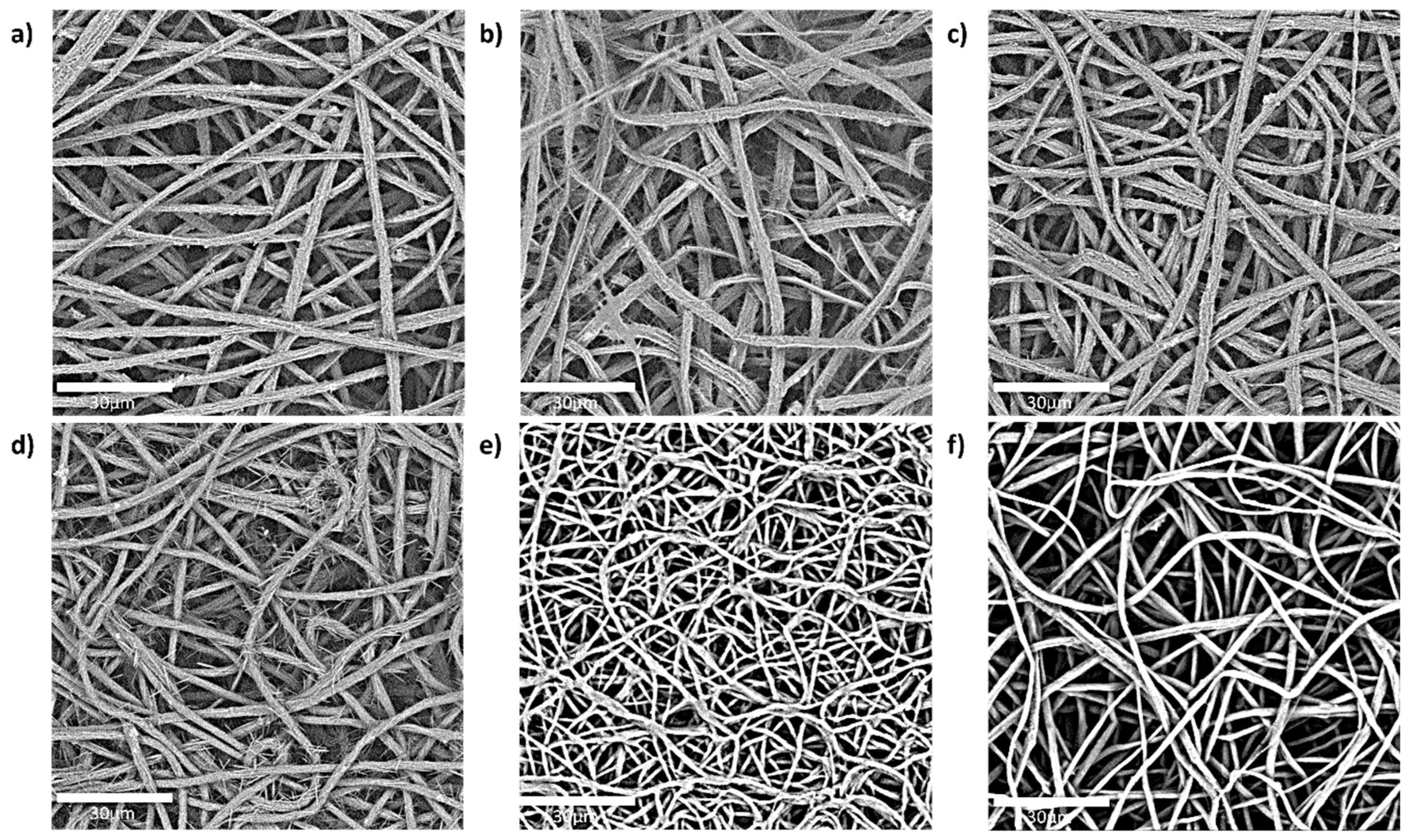

3.1. Fibre Morphology (SEM) of the Active Layer

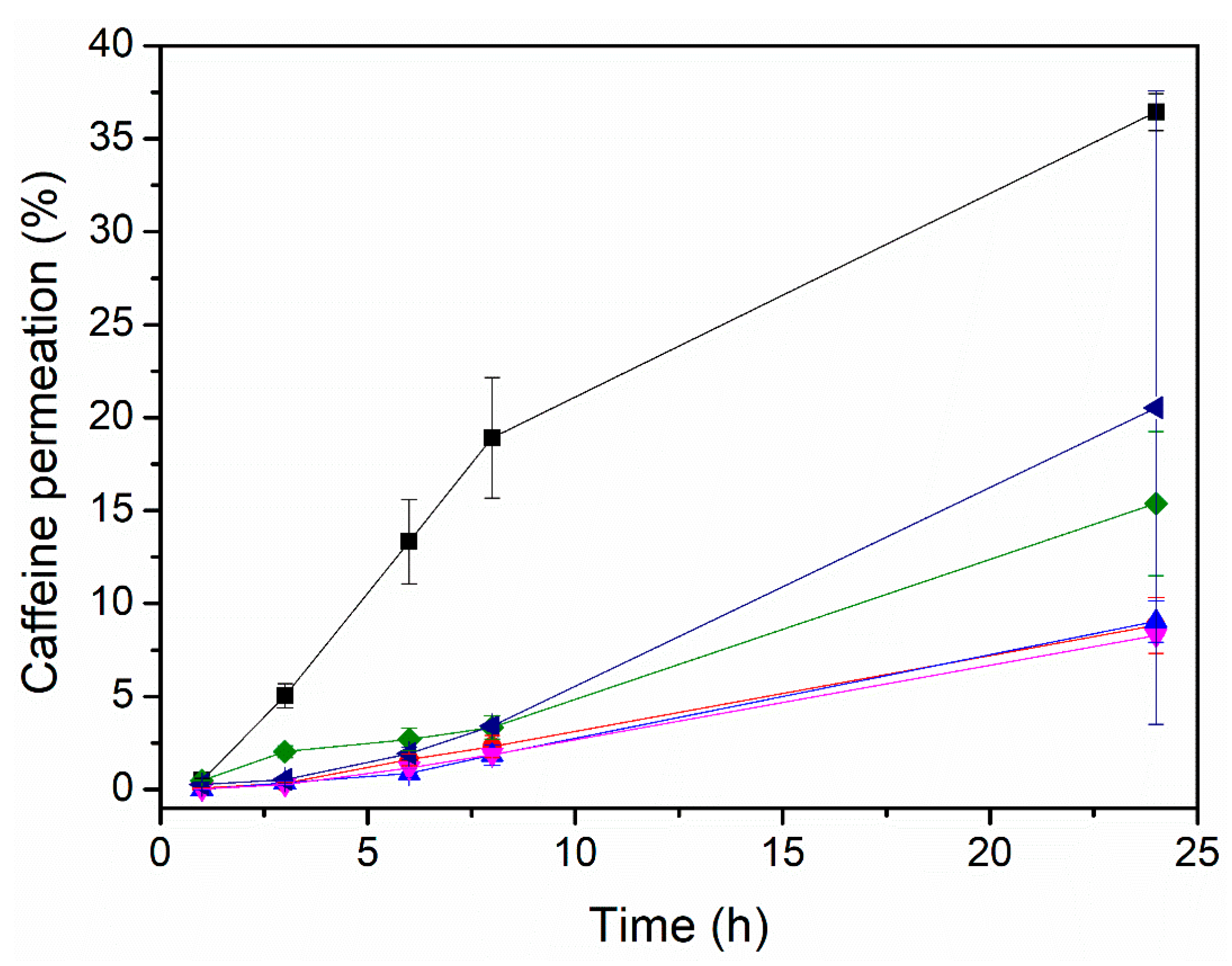

3.2. Effect of the Enhancer on the Permeation of Caffeine

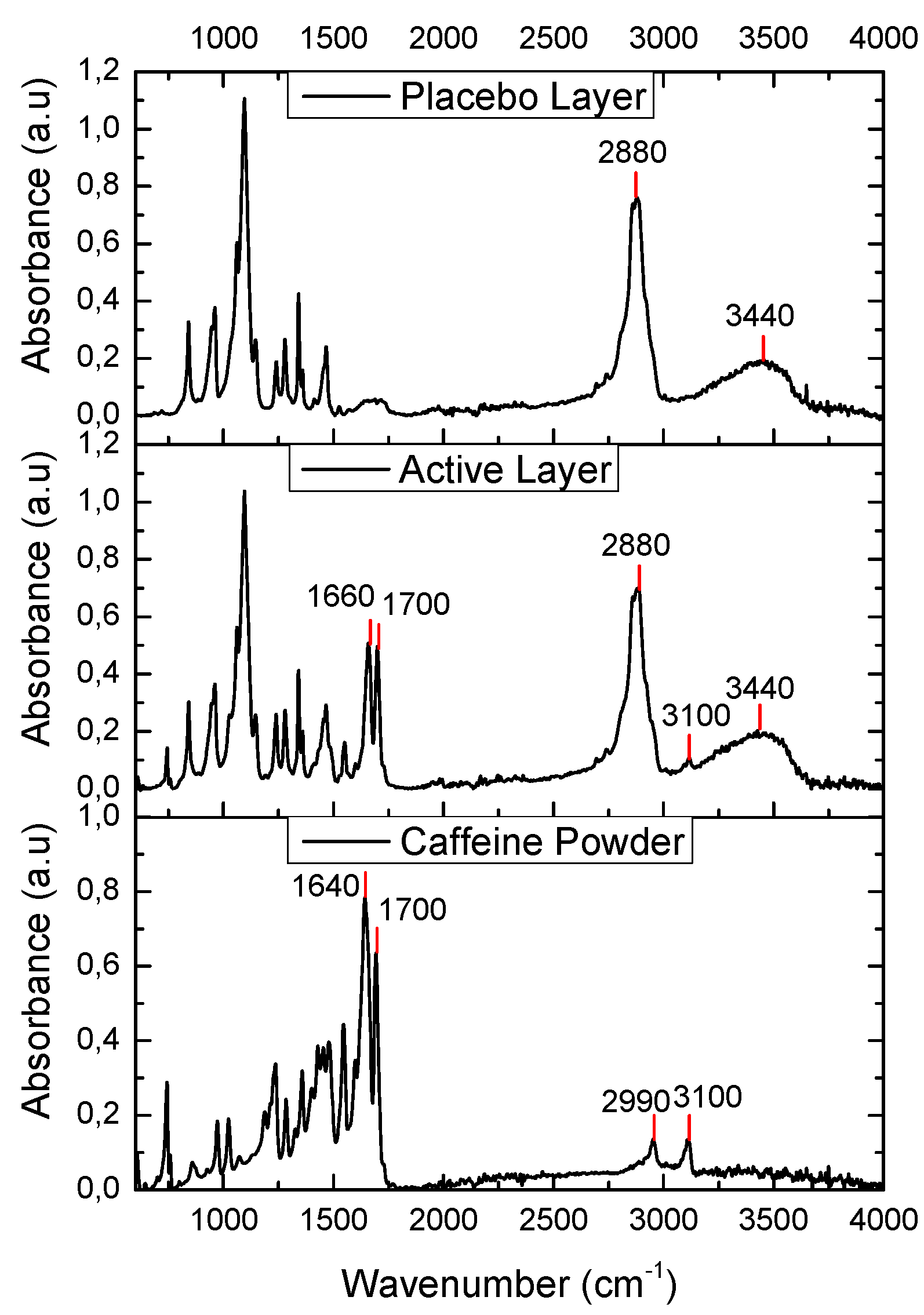

3.3. Fourier Transform Infrared (FTIR)

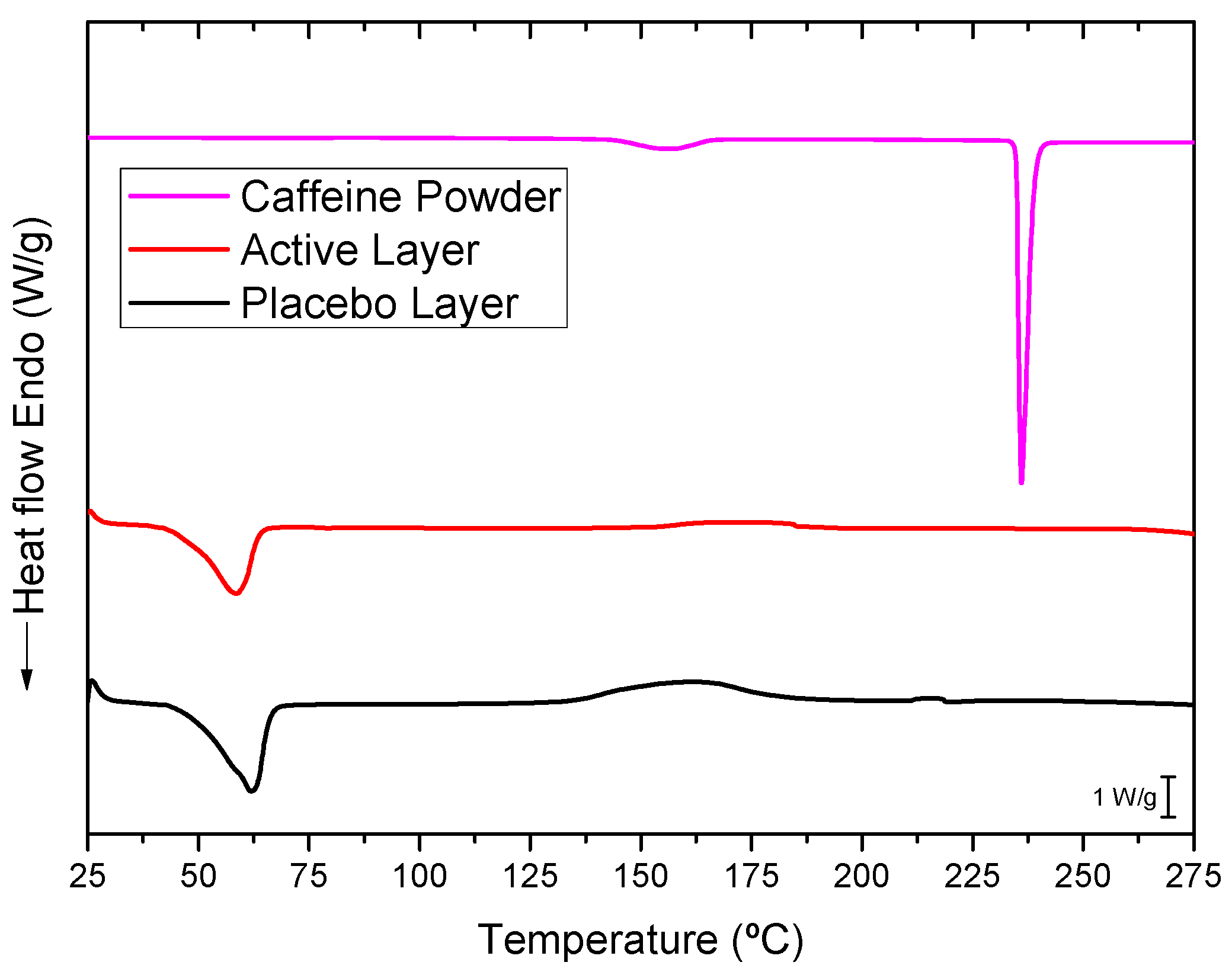

3.4. Differential Scanning Calorimetry (DSC)

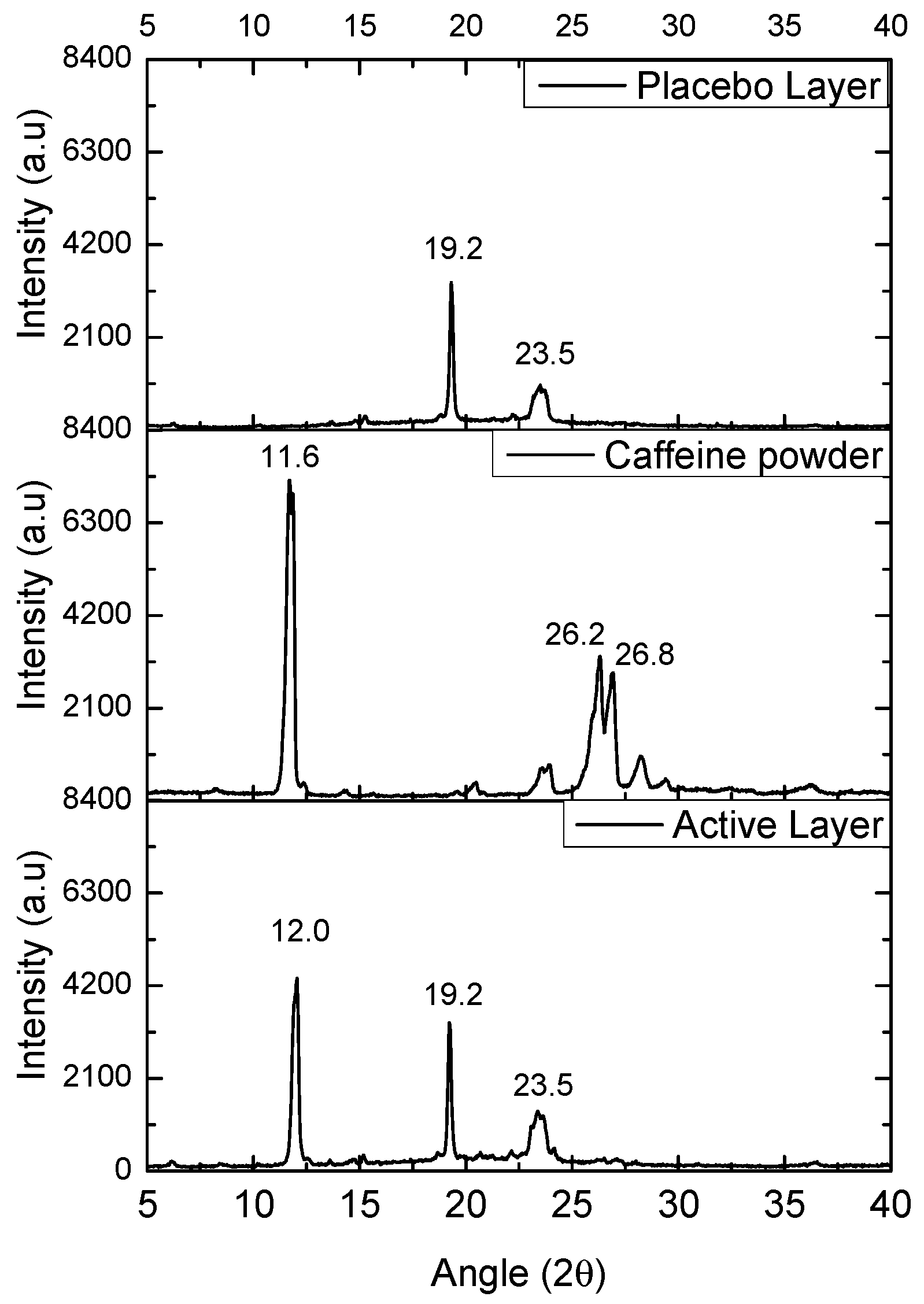

3.5. Wide-Angle X-Ray Scattering (WAXS)

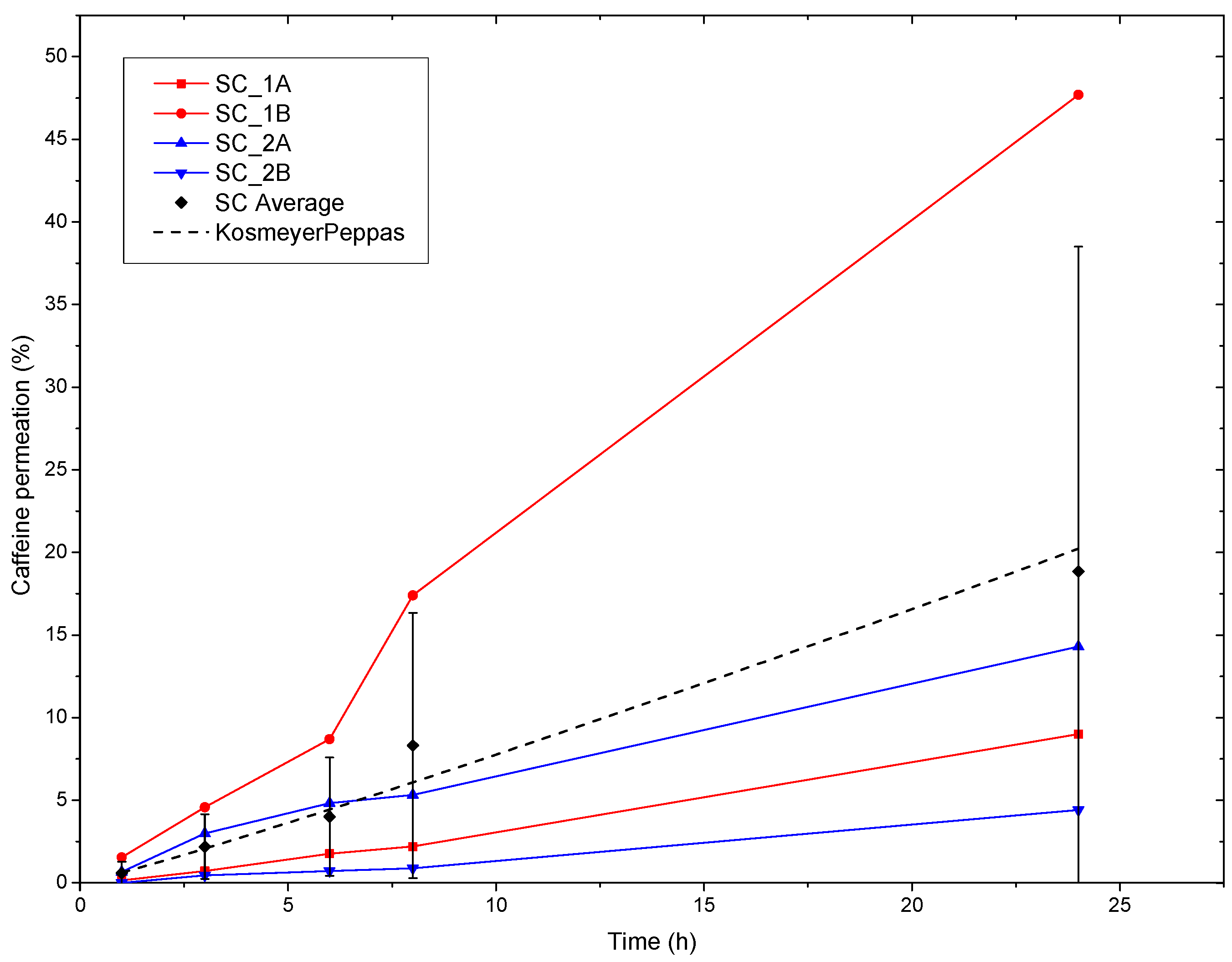

3.6. Ex-Vivo Human SC Permeation and Modelling of Caffeine

4. Conclusions

Acknowledgements

References

- Ramadon, D.; McCrudden, M.T.C.; Courtenay, A.J.; Donnelly, R.F. Enhancement strategies for transdermal drug delivery systems: current trends and applications. Drug Deliv. Transl. Res. 2022, 12, 758–791. [CrossRef]

- Shi, Y.; Xu, S.; Dong, A. Design and in vitro evaluation of transdermal patches based on ibuprofen-loaded electrospun fiber mats. 2013, 333–341. [CrossRef]

- Trommer, H.; Neubert, R.H.H. Overcoming the stratum corneum: The modulation of skin penetration. A review. Skin Pharmacol. Physiol. 2006, 19, 106–121. [CrossRef]

- van Smeden, J.; Janssens, M.; Gooris, G.S.; Bouwstra, J.A. The important role of stratum corneum lipids for the cutaneous barrier function. Biochim. Biophys. Acta - Mol. Cell Biol. Lipids 2014, 1841, 295–313. [CrossRef]

- Moghadam, S.H.; Saliaj, E.; Wettig, S.D.; Dong, C.; Ivanova, M. V; Huzil, J.T.; Foldvari, M. Effect of Chemical Permeation Enhancers on Stratum Corneum.pdf. 2013.

- Prausnitz, M.R.; Langer, R. Transdermal drug delivery. Nat. Biotechnol. 2008, 26, 1261–1268. [CrossRef]

- Kováčik, A.; Kopečná, M.; Vávrová, K. Permeation enhancers in transdermal drug delivery: benefits and limitations. Expert Opin. Drug Deliv. 2020, 17, 145–155. [CrossRef]

- Dragicevic, N.; Maibach, H.I. Percutaneous penetration enhancers chemical methods in penetration enhancement: Modification of the stratum corneum. Percutaneous Penetration Enhanc. Chem. Methods Penetration Enhanc. Modif. Strat. Corneum 2015, 1–411. [CrossRef]

- Arellano, A.; Santoyo, S.; Martn, C.; Ygartua, P. Surfactant effects on the in vitro percutaneous absorption of diclofenac sodium. Eur. J. Drug Metab. Pharmacokinet. 1998, 23, 307–312. [CrossRef]

- Ibrahim, M.M.A.; Sammour, O.A.; Hammad, M.A.; Megrab, N.A. In vitro evaluation of proniosomes as a drug carrier for flurbiprofen. AAPS PharmSciTech 2008, 9, 782–790. [CrossRef]

- Xu, W.; Liu, C.; Zhang, Y.; Quan, P.; Yang, D.; Fang, L. An investigation on the effect of drug physicochemical properties on the enhancement strength of enhancer: The role of drug-skin-enhancer interactions. Int. J. Pharm. 2021, 607, 120945. [CrossRef]

- Schulz, M.; Fussnegger, B.; Bodmeier, R. Drug release and adhesive properties of crospovidone-containing matrix patches based on polyisobutene and acrylic adhesives. Eur. J. Pharm. Sci. 2010, 41, 675–684. [CrossRef]

- Teno, J.; Pardo-Figuerez, M.; Figueroa-Lopez, K.J.; Prieto, C.; Lagaron, J.M. Development of Multilayer Ciprofloxacin Hydrochloride Electrospun Patches for Buccal Drug Delivery. J. Funct. Biomater. 2022, 13, 170. [CrossRef]

- Pardo-Figuerez, M.; Teno, J.; Lafraya, A.; Prieto, C.; Lagaron, J.M. Development of an Electrospun Patch Platform Technology for the Delivery of Carvedilol in the Oral Mucosa. Nanomaterials 2022, 12, 438. [CrossRef]

- Patel, M.; Patel, A.; Desai, J.; Patel, S. Cutaneous Pharmacokinetics of Topically Applied Novel Dermatological Formulations. AAPS PharmSciTech 2024, 25, 1–18. [CrossRef]

- Kushwaha, R.; Palei, N.N. Transdermal Drug Delivery Systems: Different Generations and Dermatokinetic Assessment of Drug Concentration in Skin. Pharmaceut. Med. 2024, 38, 407–427. [CrossRef]

- Gaydhane, M.K.; Sharma, C.S.; Majumdar, S. Electrospun nanofibres in drug delivery: advances in controlled release strategies. RSC Adv. 2023, 13, 7312–7328. [CrossRef]

- Dziemidowicz, K.; Sang, Q.; Wu, J.; Zhang, Z.; Zhou, F.; Lagaron, J.M.; Mo, X.; Parker, G.J.M.; Yu, D.G.; Zhu, L.M.; et al. Electrospinning for healthcare: recent advancements. J. Mater. Chem. B 2021, 9, 939–951. [CrossRef]

- Yu, D.G.; Shen, X.X.; Branford-White, C.; White, K.; Zhu, L.M.; Annie Bligh, S.W. Oral fast-dissolving drug delivery membranes prepared from electrospun polyvinylpyrrolidone ultrafine fibers. Nanotechnology 2009, 20. [CrossRef]

- Joiner, J.B.; Prasher, A.; Young, I.C.; Kim, J.; Shrivastava, R.; Maturavongsadit, P.; Benhabbour, S.R. Effects of Drug Physicochemical Properties on In-Situ Forming Implant Polymer Degradation and Drug Release Kinetics. Pharmaceutics 2022, 14. [CrossRef]

- Luraghi, A.; Peri, F.; Moroni, L. Electrospinning for drug delivery applications: A review. J. Control. Release 2021, 334, 463–484. [CrossRef]

- Pant, B.; Park, M.; Park, S.J. Drug delivery applications of core-sheath nanofibers prepared by coaxial electrospinning: A review. Pharmaceutics 2019, 11. [CrossRef]

- Weiser, T.W. Caffeine as analgesic adjuvant. In Treatments, mechanisms, and adverse reactions of anesthetics and analgesics; Elsevier, 2022; pp. 63–72.

- Sumedha, V.; Shiva, S.; Manikantan, S.; Ramakrishna, S. European Journal of Medicinal Chemistry Reports Pharmacology of caffeine and its effects on the human body. Eur. J. Med. Chem. Reports 2024, 10, 100138. [CrossRef]

- Visconti, M.J.; Haidari, W.; Feldman, S.R. Therapeutic use of caffeine in dermatology: A literature review. J. Dermatology Dermatologic Surg. 2020, 24, 18–24. [CrossRef]

- Herman, A.; Herman, A.P. Caffeine’s mechanisms of action and its cosmetic use. Skin Pharmacol. Physiol. 2012, 26, 8–14. [CrossRef]

- Avizheh, L.; Peirouvi, T.; Diba, K.; Fathi-Azarbayjani, A. Electrospun wound dressing as a promising tool for the therapeutic delivery of ascorbic acid and caffeine. Ther. Deliv. 2019, 10, 757–767. [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Kanjwal, M.A.; Lin, L.; Chronakis, I.S. Electrospun polyvinyl-alcohol nanofibers as oral fast-dissolving delivery system of caffeine and riboflavin. Colloids Surfaces B Biointerfaces 2013, 103, 182–188. [CrossRef]

- Illangakoon, U.E.; Gill, H.; Shearman, G.C.; Parhizkar, M.; Mahalingam, S.; Chatterton, N.P.; Williams, G.R. Fast dissolving paracetamol/caffeine nanofibers prepared by electrospinning. Int. J. Pharm. 2014, 477, 369–379. [CrossRef]

- .

- Seif, S.; Franzen, L.; Windbergs, M. Overcoming drug crystallization in electrospun fibers - Elucidating key parameters and developing strategies for drug delivery. Int. J. Pharm. 2015, 478, 390–397. [CrossRef]

- Naik, A.; Pechtold, L.A.R.M.; Potts, R.O.; Guy, R.H. Mechanism of oleic acid-induced skin penetration enhancement in vivo in humans. J. Control. Release 1995, 37, 299–306. [CrossRef]

- Silvertein, R.M.; Webster, F.X.; Kiemle, D.. Silverstein - Spectrometric Identification of Organic Compounds; Wiley, Ed.; 7th ed.; 2005; ISBN 0-471-39365-2.

- Sarfraz, A.; Simo, A.; Fenger, R.; Christen, W.; Rademann, K.; Panne, U.; Emmerling, F. Morphological Diversity of Caffeine on Surfaces : Needles and Hexagons Published as part of a virtual special issue of selected papers presented at the 2010 Annual Conference of the. Cryst. Growth Des. 2011, 583–588.

- Eman, A.; Namjoshi, S.; Mohammed, Y.; Roberts, M.S.; Grice, J.E.. Synergistic Skin Penetration Enhancer and Nanoemulsion Formulations Promote the Human Epidermal Permeation of Caffeine and Naproxen. Journal of Pharmaceutical Sciences, 2016, Volume 105, Issue 1, 212 – 220.

without enhancer,

without enhancer,  oleic acid,

oleic acid,  polyethylene glycol,

polyethylene glycol,  polyethylene glycol and oleic acid,

polyethylene glycol and oleic acid,  propylene glycol and oleic acid, and

propylene glycol and oleic acid, and  polyethylene glycol and eucalyptol oil.

polyethylene glycol and eucalyptol oil.

without enhancer,

without enhancer,  oleic acid,

oleic acid,  polyethylene glycol,

polyethylene glycol,  polyethylene glycol and oleic acid,

polyethylene glycol and oleic acid,  propylene glycol and oleic acid, and

propylene glycol and oleic acid, and  polyethylene glycol and eucalyptol oil.

polyethylene glycol and eucalyptol oil.

| Sample ID | Ratio Polymer/API/Enhancer (w/w) |

Solvents and ratio (w/w) |

|---|---|---|

| PEO_CAF | 80/20 | Chloroform/MeOH (80:20) |

| PEO_CAF_OA | 70/20/10 | |

| PEO_CAF_PEG | 64/20/16 | |

| PEO_CAF_PG_OA | 56/20/14/10 | |

| PEO_CAF_PEG_OA | 56/20/14/10 | |

| PEO_CAF_PEG_EUC | 60/20/15/5 |

| Sample ID | Flow-rate (mL/h) |

Voltage V+/V- (kV) |

Needle-to collector distance (cm) |

|---|---|---|---|

| PEO_CAF | 10 | 20/-5 | 20 |

| PEO_CAF_OA | 10 | 20/-10 | 20 |

| PEO_CAF_PEG | 10 | 20/-10 | 20 |

| PEO_CAF_PG_OA | 10 | 20/-10 | 20 |

| PEO_CAF_PEG_OA | 10 | 20/-10 | 20 |

| PEO_CAF_PEG_EUC | 10 | 20/-10 | 20 |

| BL (PCL) | 20 | 15/-2 | 15 |

| Sample ID | Fibre size (µm) | Caffeine at fibre surface |

| PEO_CAF | 2.1 ± 0.5 | Yes |

| PEO_CAF_OA | 2.8 ± 0.4 | Yes |

| PEO_CAF_PEG | 2.3 ± 0.4 | Yes |

| PEO_CAF_PG_OA | 2.2 ± 0.4 | Yes |

| PEO_CAF_PEG_OA | 1.1 ± 0.2 | No |

| PEO_CAF_PEG_EUC | 1.7 ± 0.2 | No |

| Sample ID | Initial Caffeine (mg/cm2) | Permeated caffeine (mg/cm2) |

|---|---|---|

| PEO_CAF | 1.33 | 0.15 ± 0.01 |

| PEO_CAF_OA | 1.87 | 0.17 ± 0.02 |

| PEO_CAF_PEG | 1.85 | 0.31 ± 0.08 |

| PEO_CAF_PG_OA | 1.95 | 0.17 ± 0.04 |

| PEO_CAF_PEG_OA | 2.02 | 0.73 ± 0.02 |

| PEO_CAF_PEG_EUC | 1.69 | 0.41 ± 0.34 |

| ID | Korsmeyer-Peppas | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| K | n | r2 | |

| PEO_CAF_PEG_OA patch | 0.63 | 1.09 | 0.96 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).