1. Introduction

Ankle sprains are among the most common musculoskeletal injuries, and several cases involve damage to the lateral ligament complex [

1,

2]. While appropriate treatment and rehabilitation during the acute phase typically restore function, inadequate management or repeated injuries can lead to chronic ankle instability (CAI) [

3,

4]. CAI is associated with sensory deficits and altered muscle activation patterns, ultimately impairing neuromuscular control [

5,

6,

7]. These impairments may increase the risk of falls and limit sports performance [

5,

6,

7]. Although rehabilitation programs targeting ankle strength and proprioception have been implemented, many individuals with CAI continue to experience functional deficits and recurrent episodes of instability [

8,

9,

10,

11]. These persistent impairments may be attributed to residual neuromuscular deficits, altered proprioception, and disruptions in central neuromuscular coordination, including compromised core stability. Recent studies suggest that although balance and strength training can improve functional outcomes [

8], they may not adequately address the role of proximal muscle activation, particularly in the diaphragm and hip flexors. This highlights the need for rehabilitation strategies that incorporate local joint mechanics and central neuromuscular control to enhance functional recovery in individuals with CAI.

Recent epidemiological investigations have underscored the substantial impact of ankle sprains on public health, noting that ankle sprains account for a significant percentage of emergency department visits worldwide [

12]. The high prevalence of ankle sprains across various age groups and activity levels highlights the urgent need for a deeper understanding of both the acute injury mechanisms and the long-term consequences that can lead to CAI [

13,

14]. Furthermore, economic analyses indicate that CAI incurs not only substantial direct costs, including healthcare expenditures but also significant indirect costs, such as lost work productivity, collectively imposing a considerable burden on the society [

15].

Recent studies have suggested that local ankle instability can influence the central functions of the trunk and hip, potentially affecting core muscle activation and balance control [

16,

17]. Of particular interest is the diaphragm, which serves not only as the primary muscle of inspiration but also plays a key role in regulating intra-abdominal pressure and maintaining trunk stability [

18,

19]. The diaphragm coordinates with deep core muscles such as the multifidus, transversus abdominis, and pelvic floor muscles to control posture and stabilise proximal muscle groups [

20,

21]. Previous research has demonstrated that diaphragmatic function affects postural control by regulating intra-abdominal pressure and enhancing trunk stability [

18,

22,

23]. Dysfunction of this system has been linked to impaired motor control, reduced diaphragm contractility, and potential risks of musculoskeletal instability and injury, as observed in individuals with CAI and increased respiratory demand [

18,

23].

Research has indicated that individuals with CAI may exhibit reduced diaphragmatic function, which may contribute to impaired postural control [

24,

25]. Therefore, assessments and interventions for CAI should address not only the muscles surrounding the ankle but also the function of the deep core muscles, including the diaphragm.

Anatomically, the diaphragm is directly connected to the iliopsoas (comprising the psoas major and iliacus), suggesting a potential bidirectional relationship between these muscles [

26,

27]. As the primary hip flexor, the iliopsoas is essential for walking, running, and maintaining posture [

28,

29,

30,

31,

32]. If impaired diaphragmatic function inhibits iliopsoas activation, it may increase the risk of re-spraining or impair athletic performance in individuals with CAI.

This study investigated the effects of diaphragmatic function on hip flexor activity in patients with CAI. Specifically, this study seeks to answer the following questions:

- (i).

Iliopsoas activity between the affected (sprained) and contralateral (control) sides during maximal isometric hip flexion under three breath-holding conditions: end-expiration, end-inspiration, and intermediate state.

- (ii).

The activity and torque output of the other hip flexor muscles (rectus femoris, sartorius, and tensor fasciae latae) were measured to determine whether a reduction in iliopsoas activity affected force production.

- (iii).

Propose a comprehensive rehabilitation strategy for individuals with CAI based on these findings.

This study aimed to bridge the gap in the existing research on neuromuscular control deficits in CAI and provide a foundation for future clinical applications. Specifically, incorporating diaphragm function assessments into CAI evaluations may refine rehabilitation strategies by addressing their impact on hip flexor activity. By examining the interaction between diaphragmatic function and iliopsoas activation, this study aimed to enhance our understanding of musculoskeletal injuries, emphasising both local joint mechanics and central neuromuscular coordination in rehabilitation approaches. Clarifying the relationship between the diaphragmatic function and hip flexor activation may contribute to the development of targeted rehabilitation strategies. Incorporating diaphragmatic training into CAI rehabilitation programs can improve functional stability, reduce re-injury rates, and enhance athletic performance.

2. Results

2.1. Hip Flexor Muscle Activity

Electromyographic (EMG) signals from the four hip flexor muscles showed that the root mean square (RMS) value of the iliopsoas on the affected side was significantly lower than that on the control side during end inspiration (P < 0.05). This finding suggests that diaphragmatic activity during inspiration may influence iliopsoas activation in patients with CAI. In contrast, no significant differences were observed between the sides during end-expiration and intermediate conditions (P > 0.05), indicating that the impact of breath-holding on iliopsoas activation may be phase-dependent. Additionally, no significant differences were found between the affected and control sides for the rectus femoris, sartorius, and tensor fasciae latae under any breath-holding condition (P > 0.05), suggesting that this effect was limited to the iliopsoas rather than affecting all hip flexors.

Table 1 presents the detailed RMS values for each muscle under different breath-holding conditions on both the affected and control sides.

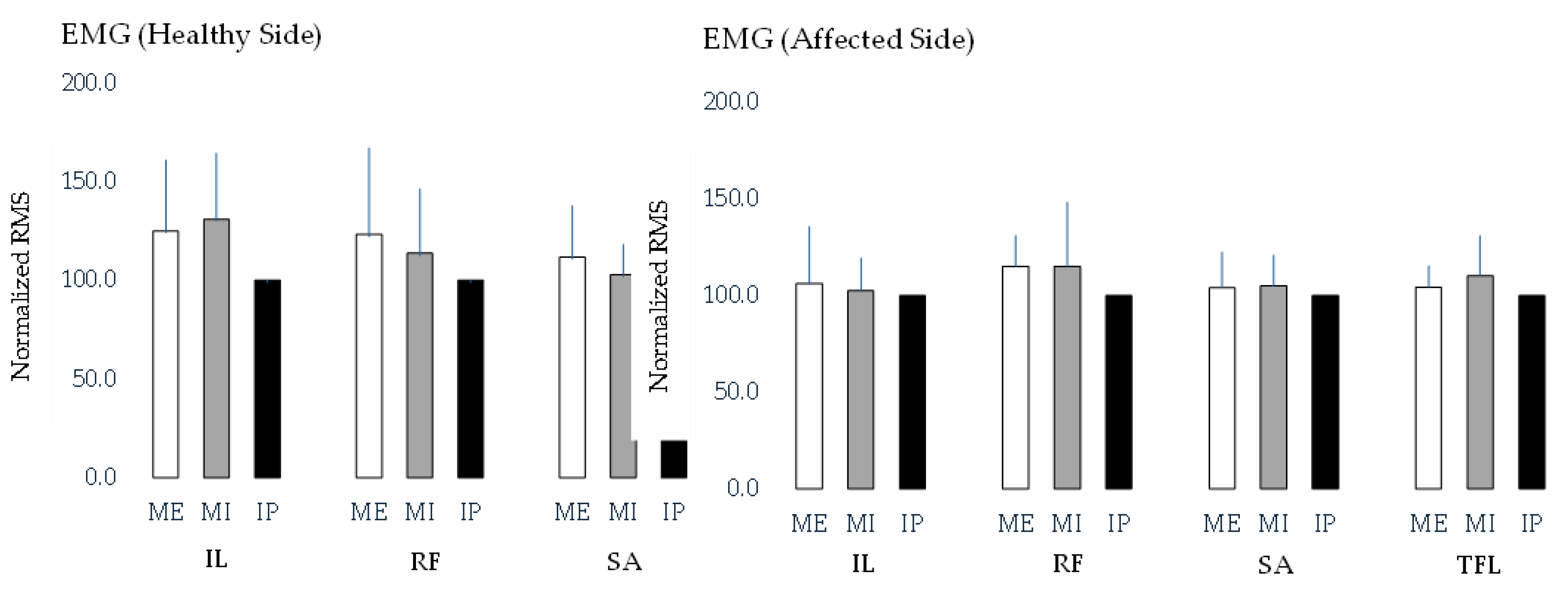

Figure 1 compares the RMS values of the hip flexor muscles under different breath-holding conditions on both the affected and control sides. However, no significant differences in RMS values were observed across the breath-holding conditions on either side.

The table presents the root mean square (RMS) values of the four hip flexor muscles—iliopsoas (IL), rectus femoris (RF), sartorius (SA), and tensor fasciae latae (TFL)—measured under three breath-holding conditions: maximum expiration (ME), maximum inspiration (MI), and an intermediate position (IP). The values are reported as mean ± standard deviation. A significant difference in iliopsoas RMS values was observed between the affected and healthy sides during inspiration, with the healthy side showing significantly higher values (p < 0.05). However, no significant differences were found between the affected and healthy sides for the other hip flexor muscles under any breath-holding condition. These findings suggest that diaphragmatic activity during inspiration may selectively influence iliopsoas activation, whereas other hip flexors remain unaffected. These data provide insights into muscle activation patterns and the potential influence of the respiratory state on hip flexor function in individuals with chronic ankle instability.

Figure 1.

Comparison of root mean square (RMS) values of hip flexor muscles across different breath-holding conditions for the healthy and affected sides.

Figure 1.

Comparison of root mean square (RMS) values of hip flexor muscles across different breath-holding conditions for the healthy and affected sides.

The bar graph illustrates the RMS values of the four hip flexor muscles—iliopsoas (IL), rectus femoris (RF), sartorius (SA), and tensor fasciae latae (TFL)—measured under three breath-holding conditions: maximum expiration (ME), maximum inspiration (MI), and an intermediate position (IP). Separate comparisons were conducted for each muscle across breath-holding conditions on the healthy and affected sides. However, no significant differences in RMS values were found across breath-holding conditions for any of the muscles on either side. These findings suggest that the breath-holding state does not significantly alter hip flexor muscle activation in individuals with chronic ankle instability.

2.2. Torque Measurements

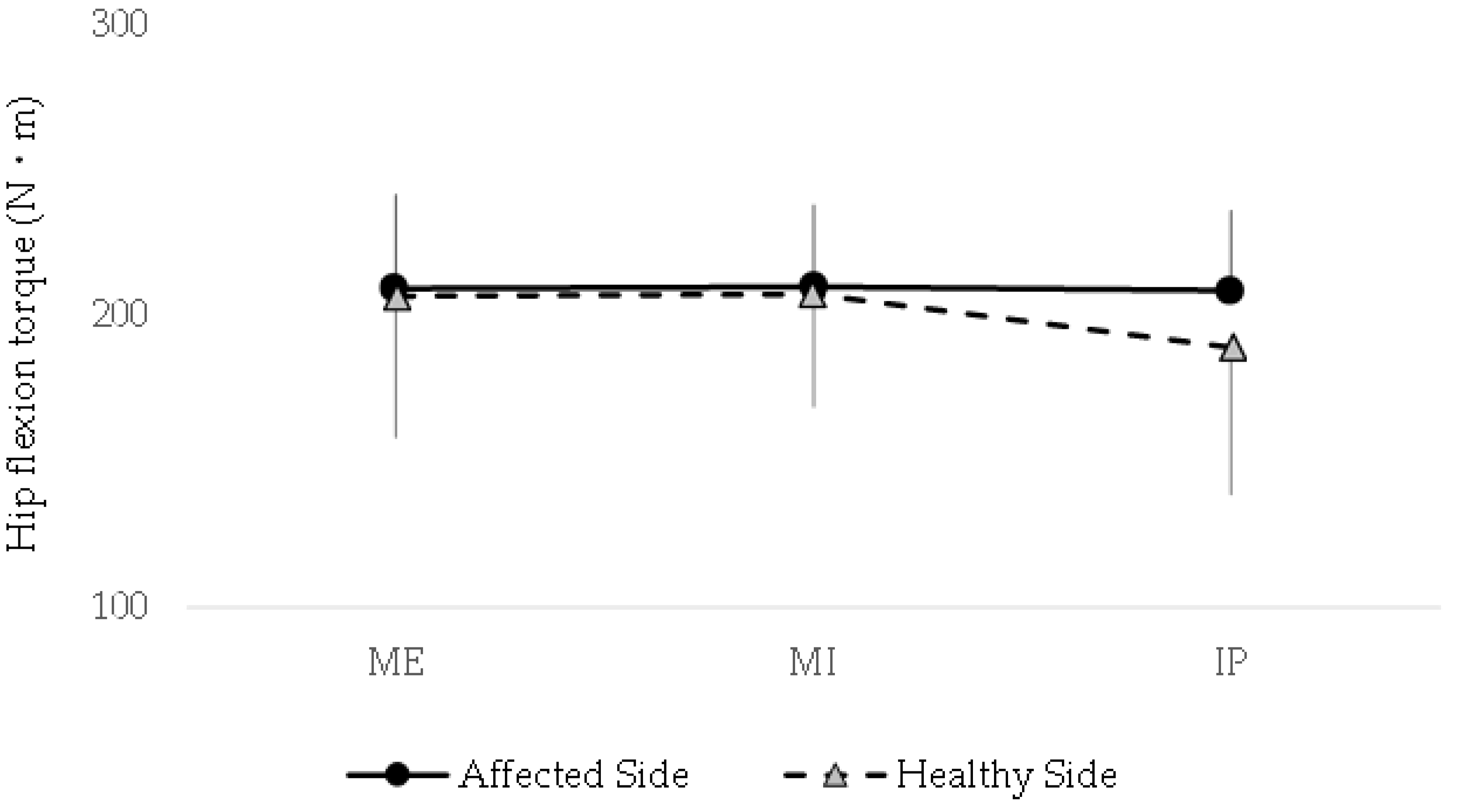

The peak isometric hip flexion torque did not differ significantly between the affected and control sides under any of the three breath-holding conditions (P > 0.05). Additionally, no significant within-group differences were found when comparing the torque values across breath-holding conditions on either side.

Figure 2 shows the detailed torque values, demonstrating that the respiratory state has no measurable impact on the maximal hip flexion strength in individuals with CAI. These findings suggest that, unlike muscle activation patterns, peak torque generation remains consistent regardless of the breath-holding condition.

The line graph depicts torque values for both sides across various breath-holding conditions: maximum expiration (ME), maximum inspiration (MI), and an intermediate position (IP). No significant differences in peak isometric hip flexion torque were observed between the affected and healthy sides under any condition (P > 0.05). Additionally, within-group comparisons revealed no significant variations in torque across breath-holding conditions for either side. These findings suggest that the respiratory state does not influence maximal hip flexion strength in individuals with chronic ankle instability, in contrast to its potential effect on muscle activation patterns.

3. Discussion

This is the first study to evaluate the effect of breath-holding conditions on iliopsoas activity in individuals with CAI, revealing a significant reduction in muscle activity on the affected side during end-inspiration. This finding suggests that impaired diaphragmatic function may suppress iliopsoas activity, potentially contributing to the altered neuromuscular coordination in the lumbopelvic region. These results highlight the need of considering diaphragm function in rehabilitation programs for CAI, as its dysfunction could compromise not only postural stability but also lower-limb motor control.

3.1. Relationship Between Diaphragm Function and Iliopsoas Activity

The diaphragm plays a key role not only in respiration but also in maintaining intra-abdominal pressure and trunk stability [

33,

34]. During end inspiration, the diaphragm is nearly maximally contracted, requiring coordinated action with the deep core muscles, including the multifidus, transversus abdominis, and pelvic floor muscles [

35,

36]. Optimal coordination between these muscles is essential for stabilising the lumbopelvic region and facilitating efficient movement. In individuals with CAI, prolonged pain avoidance and joint instability may disrupt this motor chain, impairing deep-core muscle control [

37,

38,

39]. These impairments can lead to compensatory movement patterns, reduced postural stability, and inefficient force transmission during functional tasks. The observed reduction in iliopsoas activity on the affected side during end-inspiration suggests that impaired diaphragmatic contraction and compromised intra-abdominal pressure regulation may underlie this phenomenon.

Additionally, given its anatomical connection to the diaphragm [

26,

27], weakened iliopsoas may further contribute to movement asymmetry and reduced functional performance. Further investigation into the neuromuscular mechanisms responsible for this selective reduction in muscle activity is warranted, particularly under dynamic conditions, such as walking or jumping. Future studies should explore whether targeted diaphragmatic training can enhance iliopsoas activation and improve overall motor control in individuals with CAI.

3.2. Comparison With Other Hip Flexor Muscles and Impact on Force Production

No significant differences were found between the affected and control sides for the rectus femoris, sartorius, and tensor fasciae latae across all breath-holding conditions, and no differences were observed in the hip flexion torque. This finding suggests that these secondary hip flexors may compensate for reduced iliopsoas activation, ensuring that overall torque production remains unaffected under static conditions.

These results suggest that compensatory activation of other hip flexor muscles may maintain overall torque production despite reduced iliopsoas activity [

40,

41]. However, during prolonged dynamic contractions or multi-joint movements, such as stair climbing or sports activities, diminished iliopsoas activity may have a more pronounced effect on performance [

32,

42,

43,

44]. The iliopsoas plays a crucial role in both speed and force production during hip flexion [

45], and its dysfunction can result in reduced power output, slower movement execution, and compensatory activation of secondary hip flexors during locomotion. Furthermore, long-term compensatory recruitment of the rectus femoris, sartorius, and tensor fasciae latae can lead to muscle imbalances, disrupt overall lower-limb coordination, and increase the risk of additional musculoskeletal issues.

3.3. Comparison With Clinical Implications and Rehabilitation Applications

Our findings provide new insights into the rehabilitation of CAI. Traditional rehabilitation approaches typically focus on strengthening the muscles surrounding the ankle and improving balance [

46,

47]. However, impaired coordination of the diaphragm and deep core muscles [

24,

25] may also contribute to reduced activity or coordination of proximal muscles such as the iliopsoas [

48,

49,

50]. This dysfunction can lead to decreased lumbopelvic stability, inefficient force transfer during movement, and compensatory patterns, which may further compromise lower-limb mechanics.

Clinically, incorporating diaphragmatic breathing exercises to enhance diaphragmatic function and intra-abdominal pressure regulation, combined with core stability training targeting the multifidus, transversus abdominis, and pelvic floor muscles, may improve functional connectivity between the diaphragm and iliopsoas. Restoring proper neuromuscular control in the lumbopelvic region may help optimise postural stability, reduce compensatory muscle activation, and improve movement efficiency in individuals with CAI.

Additionally, functional training aimed at improving coordination between the diaphragm and iliopsoas during dynamic activities such as walking, running, and cutting manoeuvres may help reduce the risk of re-sprains and enhance movement efficiency. Dynamic exercises that integrate breathing techniques with lower-limb movements, such as resisted breathing drills during gait training or plyometric activities, may be effective in reinforcing this neuromuscular connection. Furthermore, incorporating breathing control strategies into sports-specific drills, such as acceleration-deceleration tasks or change-of-direction exercises, may further optimise functional performance and prevent injury.

Appropriate movement-based assessments of diaphragmatic function are essential to assess the effectiveness of these interventions and better understand their underlying mechanisms. Movement-based assessments of diaphragmatic function, such as inspiratory muscle testing, diaphragmatic ultrasonography, and spirometry, could provide deeper clinical insights into their contribution to lower-limb stability and neuromuscular control. Combining these assessments with EMG analysis of the iliopsoas and other hip stabilisers would allow for a more comprehensive evaluation of the interplay between respiratory mechanics and proximal muscle activation.

3.4. Limitations

This study has certain limitations. First, the small sample size constrains the generalisability of the findings, highlighting the need for future research with larger and more diverse cohorts to improve the statistical robustness and validate the results across different populations. Second, the study focused exclusively on static maximal isometric contractions, limiting the understanding of how diaphragmatic function influences iliopsoas activity during dynamic movement. Given that functional activities involve continuous postural adjustments and varying muscle demands, examining this interaction during real-world movements, such as walking, running, or jumping, would provide more ecologically valid insights.

Furthermore, we used surface electromyography (sEMG) to assess muscle activation. Although sEMG is valuable, it does not directly measure the diaphragmatic function. Employing more precise imaging modalities, such as ultrasound or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), could provide a more comprehensive assessment of diaphragmatic movement and its mechanical contribution to neuromuscular control. In addition, integrating respiratory motion tracking with electromyography and kinematic analyses may offer deeper insights into the interplay between breathing mechanics and lower-limb function. Such multimodal approaches could help elucidate whether diaphragmatic dysfunction contributes to movement asymmetries or compensatory patterns in individuals with CAI.

Addressing these limitations requires future research exploring diaphragmatic function under more dynamic and ecologically valid conditions by incorporating advanced measurement techniques and larger sample sizes.

3.5. Future Directions

Future research should investigate the interaction between the diaphragm and iliopsoas during dynamic tasks and assess the role of diaphragmatic function across a broader range of activities. For instance, studies exploring diaphragmatic engagement during high-intensity locomotor tasks, such as sprinting, sudden acceleration, deceleration, or agility drills, could provide deeper insights into its role in motor control and movement efficiency. Examining its contribution to stability during unilateral stance or load-bearing activities would further clarify its impact on lower-limb function. Additionally, integrating real-time respiratory monitoring with EMG and motion capture analysis would offer a more comprehensive understanding of how breathing patterns influence hip flexor activation and whether altered diaphragmatic function leads to compensatory movement strategies.

Furthermore, randomised controlled trials are necessary to evaluate the effectiveness of rehabilitation programs aimed at enhancing diaphragmatic function in patients with CAI. Interventions incorporating diaphragmatic breathing exercises, intra-abdominal pressure training, and functional movement drills should be examined to determine their effects on neuromuscular coordination, injury prevention, and athletic performance. Future trials should also assess individualised training protocols to determine whether tailored diaphragmatic interventions yield superior outcomes compared with generalised rehabilitation approaches. Including control groups following standard rehabilitation protocols would facilitate direct comparison and provide clear evidence of their efficacy.

Longitudinal studies assessing whether improvements in diaphragmatic function correlate with reduced re-sprain rates and enhanced functional outcomes would further strengthen the clinical relevance of this study. Additionally, investigating the potential neuromechanical link between diaphragmatic function and spinal alignment, pelvic stability, and limb symmetry may provide further insight into broader musculoskeletal implications. Exploring whether enhanced diaphragmatic function contributes to improved proprioception, balance, and postural stability could broaden its applicability beyond CAI rehabilitation to musculoskeletal health. Finally, interdisciplinary research combining sports science, biomechanics, and respiratory physiology could help to develop a more integrative framework for optimising movement performance and injury prevention.

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Relationship Between Diaphragm Study Design and Participants

This cross-sectional observational study investigated the relationship between breath-holding conditions and hip flexor muscle activity in patients with a history of chronic ankle sprain (CAS). This study specifically targeted adults diagnosed with functional ankle instability, which was confirmed through clinical evaluation using the Cumberland Ankle Instability Tool and the anterior drawer test.

A total of eleven participants (six males, five females; mean age: 28.5 ± 4.2 years) were recruited based on the following inclusion criteria:

A history of CAS with onset at least six months prior to the study.

Subjective instability reported in one ankle.

A clear distinction between affected and unaffected limbs, allowing side-to-side comparisons

No history of ankle surgery or other major lower-limb interventions in the past year.

Engagement in moderate or high levels of physical activity was defined as participation in sports or recreational exercise at least once a week.

No history of other lower-limb musculoskeletal conditions, such as knee or hip disorders.

All procedures were conducted in accordance with the ethical standards outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Kanazawa Orthopaedic Sports Medicine Clinic Ethics Committee (approval number: Kanazawa-OSMC-2020-004). Written informed consent was obtained from all participants before the commencement of the study.

4.2. Muscle Measurement and Equipment

4.2.1. sEMG

sEMG signals were recorded from four hip flexor muscles: the iliopsoas (IL), rectus femoris (RF), sartorius (SA), and tensor fasciae latae (TFL). Active electrodes (MQ8/16 16-bit EMG amplifier; Kissei Comtec, Nagano, Japan), measuring 1.0 × 1.0 mm, were applied with an interelectrode distance of 10 mm. The high impedance of the electrodes ensured accurate bioelectrical signal capture even during dynamic movements. The system digitised the signals near the electrodes, minimised noise, and reduced preprocessing time. The EMG signals were recorded at a sampling rate of 2,000 Hz using a telemetry system (MQ16; Kissei Comtec) and analysed using a dedicated software (Kine Analyser; Kissei Comtec).

4.2.2. Electrode Placement

Electrodes were placed over specific anatomical landmarks to ensure accurate measurement of muscle activity. Each muscle was placed as follows:

Iliopsoas: 3–5 cm distal to the anterior superior iliac spine (ASIS), with ultrasound guidance used to confirm proper subfascial placement.

Rectus femoris: midpoint between the anterior inferior iliac spine (AIIS) and upper edge of the patella.

Sartorius: Along the line connecting the ASIS and medial tibial condyle, approximately 8 cm distal to the ASIS.

Tensor fasciae latae: Midpoint between the ASIS and apex of the greater trochanter.

The electrodes were aligned with the muscle fibres, and a reference electrode was placed on the right patella to ensure consistency. Before electrode placement, the skin was shaved, cleaned with alcohol, and lightly abraded to reduce impedance and enhance the signal quality.

During each trial, the muscle activity was recorded continuously for 5 s, after which the signals were full-wave rectified and processed using a bandpass filter (10–500 Hz) to remove unwanted noise and improve signal clarity.

4.2.3. Isokinetic Dynamometer

A Cybex isokinetic dynamometer was used to measure the peak torque during maximal isometric hip flexion. The participants were placed in the supine position with the hip at 0° and the knee flexed at 90° to effectively isolate the hip flexor muscles. Adjustable stabilisation straps were applied over the trunk and pelvis to prevent compensatory movements and to ensure accurate force measurements.

4.2.4. Experimental Conditions (Breath-Holding Conditions)

Muscle activity and torque were measured under three distinct breath-holding conditions:

End expiration (functional residual capacity state)

End inspiration (maximum lung inflation state)

Intermediate state (resting expiration level)

For each condition, the participants performed a 5-s maximal isometric hip flexion, with measurements recorded for both the affected (sprain history) and control limbs.

The sequence of breath-holding conditions was randomised for each participant to ensure randomisation and to prevent order effects. A rest period of 3 min was provided between trials to prevent fatigue and maintain consistency in muscle performance.

A spirometer was used to monitor respiratory patterns to verify adherence to breathing conditions, and oxygen saturation and heart rate were continuously monitored for safety purposes.

4.3. Data Analysis

4.3.1. EMG Analysis

For each trial, the central 3-s period during which the participant maintained a stable maximal effort was extracted for analysis. The root mean square (RMS) value of the EMG signal, which serves as an indicator of muscle activation, was calculated.

The RMS values obtained in the intermediate breathing condition were normalised to 100% of the relative values calculated for the end-expiration and end-inspiration conditions to facilitate comparisons across conditions. This normalisation approach ensured that individual variations in absolute muscle activity did not confound comparative analysis.

4.3.2. Torque Analysis

The peak torque values recorded during each 5-s maximal isometric contraction were extracted and compared across the three breath-holding conditions. Additionally, torque differences between the affected and control limbs were examined to assess the impact of breathing patterns on force generation.

4.3.3. Statistical Analysis

A paired t-test was used to compare the muscle activity and torque between the affected and control sides for each breath-holding condition. Differences across breath-holding conditions were assessed using repeated-measures analysis of variance (ANOVA) with Bonferroni post hoc tests. Statistical significance was set at P < 0.05. All analyses were performed using the SPSS software (IBM SPSS Statistics 27).

5. Conclusions

This study investigated the influence of different breath-holding conditions on iliopsoas and other hip flexor muscle activities in individuals with CAI. Given the close anatomical and functional relationship between the diaphragm and deep core muscles, including the iliopsoas, understanding how respiratory mechanics influence lower-limb muscle activation is crucial for optimising rehabilitation strategies.

The results showed that during the end-inspiration condition, iliopsoas muscle activity on the affected side was significantly lower than that on the control side (p < 0.05). In contrast, no significant differences were observed in the activation levels of the other hip flexor muscles (rectus femoris, sartorius, and tensor fasciae latae) between the affected and control sides under any breathing conditions. Additionally, no significant differences were found in peak hip flexion torque across breath-holding conditions.

These findings suggest that altered diaphragmatic function may selectively affect iliopsoas activity in individuals with CAI, potentially due to compromised neuromuscular coordination between the diaphragm and the deep core muscles. The reduction in iliopsoas activation during end-inspiration may indicate dysfunctional intra-abdominal pressure regulation, which is essential for stabilising the lumbopelvic region during movement.

From a clinical perspective, these results highlight the importance of incorporating targeted exercises that enhance deep core muscle coordination, including that of the diaphragm, into rehabilitation programs for individuals recovering from ankle sprain. Traditional rehabilitation protocols often focus on proprioception, strength, and balance training. However, addressing respiratory mechanics may provide an additional avenue for improving neuromuscular control and reducing the risk of reinjury.

Future research should explore the underlying mechanisms linking diaphragmatic function to iliopsoas activation in greater detail using advanced imaging techniques, such as dynamic ultrasound or MRI, to assess diaphragmatic motion during breathing tasks. Intervention studies should be conducted to evaluate the effectiveness of diaphragmatic training, breathing control techniques, and deep core stabilisation exercises in enhancing iliopsoas function and improving overall movement efficiency.

Such insights could have important applications in both sports and clinical settings, helping develop more comprehensive rehabilitation strategies aimed at preventing reinjury, optimising performance, and promoting long-term musculoskeletal health in individuals with CAI.

Author Contributions

Conceptualisation, T.J.; methodology, T.J.; software, T.J.; validation, T.J. and S.N.; formal analysis, T.J.; investigation, T.J., S.N., M.W., and Y.H.; resources, T.J.; data curation, T.J.; writing—original draft preparation, T.J.; writing—review, and editing, T.J., J.O., N.S., and T.F.; visualisation, T.J.; supervision, T.J.; project administration, T.J. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The authors received no funding for this study.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Kanazawa Orthopaedic Sports Medicine Clinic Ethics Committee (approval number: Kanazawa-OSMC-2020-004).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all the participants involved in the study. Written informed consent was obtained from the patients for publication of this paper.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank all those who contributed to this study. We express our gratitude to our families for their unwavering support and encouragement throughout this study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Declaration of generative AI and AI-assisted technologies in the writing process

Statement: During the preparation of this work the authors used the generative AI tool / ChatGPT in order to assist with editing. After using this tool/service, the authors reviewed and edited the content as needed and takes full responsibility for the content of the published article.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| CAI |

chronic ankle instability |

| sEMG |

surface electromyography |

| EMG |

electromyography |

| MRI |

magnetic resonance imaging |

| RMS |

root mean square |

| IL |

iliopsoas |

| RF |

rectus femoris |

| SA |

sartorius |

| TFL |

tensor fasciae latae |

| ASIS |

anterior superior iliac spine |

| ME |

maximum expiration |

| MI |

maximum inspiration |

| IP |

intermediate position |

| ANOVA |

analysis of variance |

References

- Hertel, J. Functional Anatomy, Pathomechanics, and Pathophysiology of Lateral Ankle Instability. J. Athl. Train. 2002, 37, 364–375. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Fong, D.T.-P.; Hong, Y.; Chan, L.-K.; Yung, P.S.-H.; Chan, K.-M. A Systematic Review on Ankle Injury and Ankle Sprain in Sports. Sports Med. 2007, 37, 73–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gribble, P.A.; Delahunt, E.; Bleakley, C.; Caulfield, B.; Docherty, C.L.; Fourchet, F.; Fong, D.; Hertel, J.; Hiller, C.E.; Kaminski, T.W.; et al. Selection Criteria for Patients With Chronic Ankle Instability in Controlled Research: A Position Statement of the International Ankle Consortium. J. Orthop. Sports Phys. Ther. 2013, 43, 585–591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miklovic, T.M.; Donovan, L.; Protzuk, O.A.; Kang, M.S.; Feger, M.A. Acute lateral ankle sprain to chronic ankle instability: a pathway of dysfunction. Physician Sportsmed. 2017, 46, 116–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, K.-M.; Best, T.M.; Aiyer, A. How Do Athletes with Chronic Ankle Instability Suffer from Impaired Balance? An Update on Neurophysiological Mechanisms. Optom. Vis. Sci. 2017, 16, 309–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levin, O.; Vanwanseele, B.; Thijsen, J.R.; Helsen, W.F.; Staes, F.F.; Duysens, J. Proactive and reactive neuromuscular control in subjects with chronic ankle instability: Evidence from a pilot study on landing. Gait Posture 2015, 41, 106–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, K.-M.; Estepa-Gallego, A.; Estudillo-Martínez, M.D.; Castellote-Caballero, Y.; Cruz-Díaz, D. Comparative Effects of Neuromuscular- and Strength-Training Protocols on Pathomechanical, Sensory-Perceptual, and Motor-Behavioral Impairments in Patients with Chronic Ankle Instability: Randomized Controlled Trial. Healthcare 2022, 10, 1364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, E.A.; Chomistek, A.K.; Kingma, J.J.; Docherty, C.L. Balance- and Strength-Training Protocols to Improve Chronic Ankle Instability Deficits, Part I: Assessing Clinical Outcome Measures. J. Athl. Train. 2018, 53, 568–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, J.; Luan, L.; Adams, R.; Witchalls, J.; Newman, P.; Tirosh, O.; Waddington, G. Can Therapeutic Exercises Improve Proprioception in Chronic Ankle Instability? A Systematic Review and Network Meta-analysis. Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabilitation 2022, 103, 2232–2244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ardakani, M.K.; Wikstrom, E.A.; Minoonejad, H.; Rajabi, R.; Sharifnezhad, A. Hop-Stabilization Training and Landing Biomechanics in Athletes With Chronic Ankle Instability: A Randomized Controlled Trial. J. Athl. Train. 2019, 54, 1296–1303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cain, M.S.; Ban, R.J.; Chen, Y.-P.; Geil, M.D.; Goerger, B.M.; Linens, S.W. Four-Week Ankle-Rehabilitation Programs in Adolescent Athletes With Chronic Ankle Instability. J. Athl. Train. 2020, 55, 801–810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Foss, K.D.B.; Thomas, S.; Khoury, J.C.; Myer, G.D.; Hewett, T.E. A School-Based Neuromuscular Training Program and Sport-Related Injury Incidence: A Prospective Randomized Controlled Clinical Trial. J. Athl. Train. 2018, 53, 20–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

-

Am. J. Sports Med. 2016, 44, 995–1003. [CrossRef]

- Doherty, C.; Bleakley, C.; Hertel, J.; Caulfield, B.; Ryan, J.; Delahunt, E. Recovery From a First-Time Lateral Ankle Sprain and the Predictors of Chronic Ankle Instability. Am. J. Sports Med. 2016, 44, 995–1003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delahunt, E.; Bleakley, C.M.; Bossard, D.S.; Caulfield, B.; Docherty, C.L.; Doherty, C.; Fourchet, F.; Fong, D.T.; Hertel, J.; E Hiller, C.; et al. Clinical assessment of acute lateral ankle sprain injuries (ROAST): 2019 consensus statement and recommendations of the International Ankle Consortium. Br. J. Sports Med. 2018, 52, 1304–1310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wagemans, J.; Taeymans, J.; Kuppens, K.; Baur, H.; Bleakley, C.; Vissers, D. Determining key clinical predictors for chronic ankle instability and return to sports with cost of illness analysis: protocol of a prospective cohort study. BMJ Open 2023, 13, e069867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCann, R.S.; Johnson, K.; Suttmiller, A.M.B. Lumbopelvic Stability and Trunk Muscle Contractility of Individuals with Chronic Ankle Instability. Int. J. Sports Phys. Ther. 2021, 16, 741–748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeJong, A.F.; Mangum, L.C.; Hertel, J. Ultrasound Imaging of the Gluteal Muscles During the Y-Balance Test in Individuals With or Without Chronic Ankle Instability. J. Athl. Train. 2020, 55, 49–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hodges PW, Heijnen I, Gandevia SC. Postural activity of the diaphragm is reduced in humans when respiratory demand increases. J. Physiol. 2001, 537, 999–1008. [CrossRef]

- Gandevia SC, Butler JE, Hodges PW, Taylor JL. Balancing acts: respiratory sensations, motor control and the skeleton. Clin Exp Pharmacol Physiol 2002; 29(1-2):118-121.

- Finta, R.; Nagy, E.; Bender, T. The effect of diaphragm training on lumbar stabilizer muscles: a new concept for improving segmental stability in the case of low back pain. J. Pain Res. 2018, ume 11, 3031–3045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eliks, M.; Zgorzalewicz-Stachowiak, M.; Zeńczak-Praga, K. Application of Pilates-based exercises in the treatment of chronic non-specific low back pain: state of the art. Postgrad. Med J. 2019, 95, 41–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hodges, P.W.; Gandevia, S.C. Changes in intra-abdominal pressure during postural and respiratory activation of the human diaphragm. J. Appl. Physiol. 2000, 89, 967–976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hodges, P.W.; Cresswell, A.G.; Daggfeldt, K.; Thorstensson, A. In vivo measurement of the effect of intra-abdominal pressure on the human spine. J. Biomech. 2001, 34, 347–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Terada, M.; Kosik, K.B.; Mccann, R.S.; Gribble, P.A. Diaphragm Contractility in Individuals with Chronic Ankle Instability. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 2016, 48, 2040–2045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Terada, M.; Kosik, K.B.; Gribble, P.A. Association of Diaphragm Contractility and Postural Control in a Chronic Ankle Instability Population: A Preliminary Study. Sports Heal. A Multidiscip. Approach 2023, 16, 19–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Diane G. The Pelvic Girdle: An Integration of Clinical Expertise and Research. 4th ed. Philadelphia: Churchill Livingstone, 2010.

- Sajko, S.; Stuber, K. Psoas Major: a case report and review of its anatomy, biomechanics, and clinical implications. . 2009, 53, 311–8. [Google Scholar]

- Regev, G.J.; Kim, C.W.; Tomiya, A.; Lee, Y.P.; Ghofrani, H.; Garfin, S.R.; Lieber, R.L.; Ward, S.R. Psoas Muscle Architectural Design, In Vivo Sarcomere Length Range, and Passive Tensile Properties Support Its Role as a Lumbar Spine Stabilizer. Spine 2011, 36, E1666–E1674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andersson, E.; Oddsson, L.; Grundström, H.; Thorstensson, A. The role of the psoas and iliacus muscles for stability and movement of the lumbar spine, pelvis and hip. Scand. J. Med. Sci. Sports 1995, 5, 10–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ikezoe, T.; Mori, N.; Nakamura, M.; Ichihashi, N. Age-related muscle atrophy in the lower extremities and daily physical activity in elderly women. Arch. Gerontol. Geriatr. 2011, 53, e153–e157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andersson, E.; Nilsson, J.; Thorstensson, A. Intramuscular EMG from the hip flexor muscles during human locomotion. Acta Physiol. Scand. 1997, 161, 361–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dorn, T.W.; Schache, A.G.; Pandy, M.G. Muscular strategy shift in human running: dependence of running speed on hip and ankle muscle performance. J. Exp. Biol. 2012, 215, 1944–1956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hodges, P.W.; Gandevia, S.C. Changes in intra-abdominal pressure during postural and respiratory activation of the human diaphragm. J. Appl. Physiol. 2000, 89, 967–976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hodges, P.W.; Gandevia, S.C. Activation of the human diaphragm during a repetitive postural task. J. Physiol. 2000, 522, 165–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sinderby, C.; Beck, J.; Spahija, J.; Weinberg, J.; Grassino, A.; Mendonca, C.T.; Schaeffer, M.R.; Riley, P.; Jensen, D.; Mantilla, C.B.; et al. Voluntary activation of the human diaphragm in health and disease. J. Appl. Physiol. 1998, 85, 2146–2158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finta, R.; Nagy, E.; Bender, T. The effect of diaphragm training on lumbar stabilizer muscles: a new concept for improving segmental stability in the case of low back pain. J. Pain Res. 2018, ume 11, 3031–3045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mousavi, S.H.; Khorramroo, F.; Minoonejad, H.; Zwerver, J. Effects of biofeedback on biomechanical factors associated with chronic ankle instability: a systematic review with meta-analysis. BMC Sports Sci. Med. Rehabilitation 2023, 15, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Urhun, E.; Develi, E. Investigation of the effect of chronic ankle instability on core stabilization, dynamic balance and agility among basketball players of a university. J. Bodyw. Mov. Ther. 2024, 40, 332–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alizamani, S.; Ghasemi, G.; Nejadian, S.L. Effects of eight week core stability training on stable- and unstable-surface on ankle muscular strength, proprioception, and dorsiflexion in athletes with chronic ankle instability. J. Bodyw. Mov. Ther. 2023, 34, 6–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carr, J.C.; Stock, M.S.; Hernandez, J.M.; Ortegon, J.R.; Mota, J.A. Additional insight into biarticular muscle function: The influence of hip flexor fatigue on rectus femoris activity at the knee. J. Electromyogr. Kinesiol. 2018, 42, 36–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stutzig, N.; Siebert, T. Muscle force compensation among synergistic muscles after fatigue of a single muscle. Hum. Mov. Sci. 2015, 42, 273–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masuda, K.; Kim, J.; Kinugasa, R.; Tanabe, K.; Kuno, S.-Y. Determinants for Stair Climbing by Elderly from Muscle Morphology. Percept. Mot. Ski. 2002, 94, 814–816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tottori, N.; Suga, T.; Miyake, Y.; Tsuchikane, R.; Otsuka, M.; Nagano, A.; Fujita, S.; Isaka, T. Hip Flexor and Knee Extensor Muscularity Are Associated With Sprint Performance in Sprint-Trained Preadolescent Boys. Pediatr. Exerc. Sci. 2018, 30, 115–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wakahara, T.; Chiba, M. Relation Between Iliopsoas Cross-sectional Area and Kicked Ball Speed in Soccer Players. Int. J. Sports Med. 2018, 39, 468–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumazaki, T.; Takahashi, T.; Nakano, T.; Sakai, T. Action and Contribution of the Iliopsoas and Rectus Femoris as Hip Flexor Agonists Examined with Anatomical Analysis. Juntendo Med J. 2022, 68, 352–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mattacola, C.G.; Dwyer, M.K. Rehabilitation of the Ankle After Acute Sprain or Chronic Instability. . 2002, 37, 413–429. [Google Scholar]

- A Al Attar, W.S.; Khaledi, E.H.; Bakhsh, J.M.; Faude, O.; Ghulam, H.; Sanders, R.H. Injury prevention programs that include balance training exercises reduce ankle injury rates among soccer players: a systematic review. J. Physiother. 2022, 68, 165–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeum, W.-J.; Lee, M.-Y.; Lee, B.-H. The Influence of Hip-Strengthening Program on Patients with Chronic Ankle Instability. Medicina 2024, 60, 1199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feger, M.A.; Donovan, L.; Hart, J.M.; Hertel, J. Lower Extremity Muscle Activation During Functional Exercises in Patients With and Without Chronic Ankle Instability. PM&R 2014, 6, 602–611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Labanca, L.; Mosca, M.; Ghislieri, M.; Agostini, V.; Knaflitz, M.; Benedetti, M.G. Muscle activations during functional tasks in individuals with chronic ankle instability: a systematic review of electromyographical studies. Gait Posture 2021, 90, 340–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).