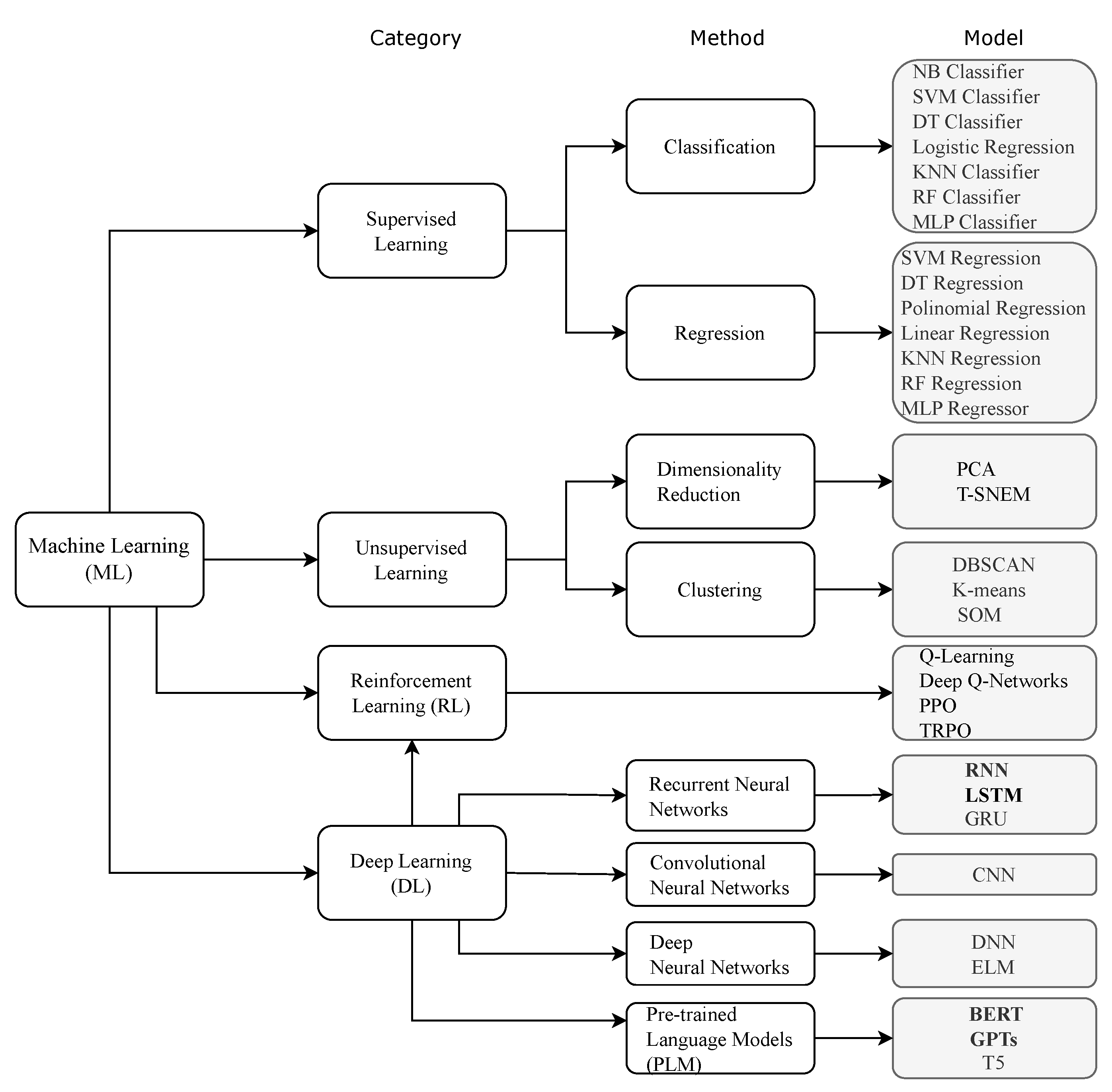

In this section the main ML techniques used in the reviewed literature, for each of the RE categories of tasks, are analyzed.

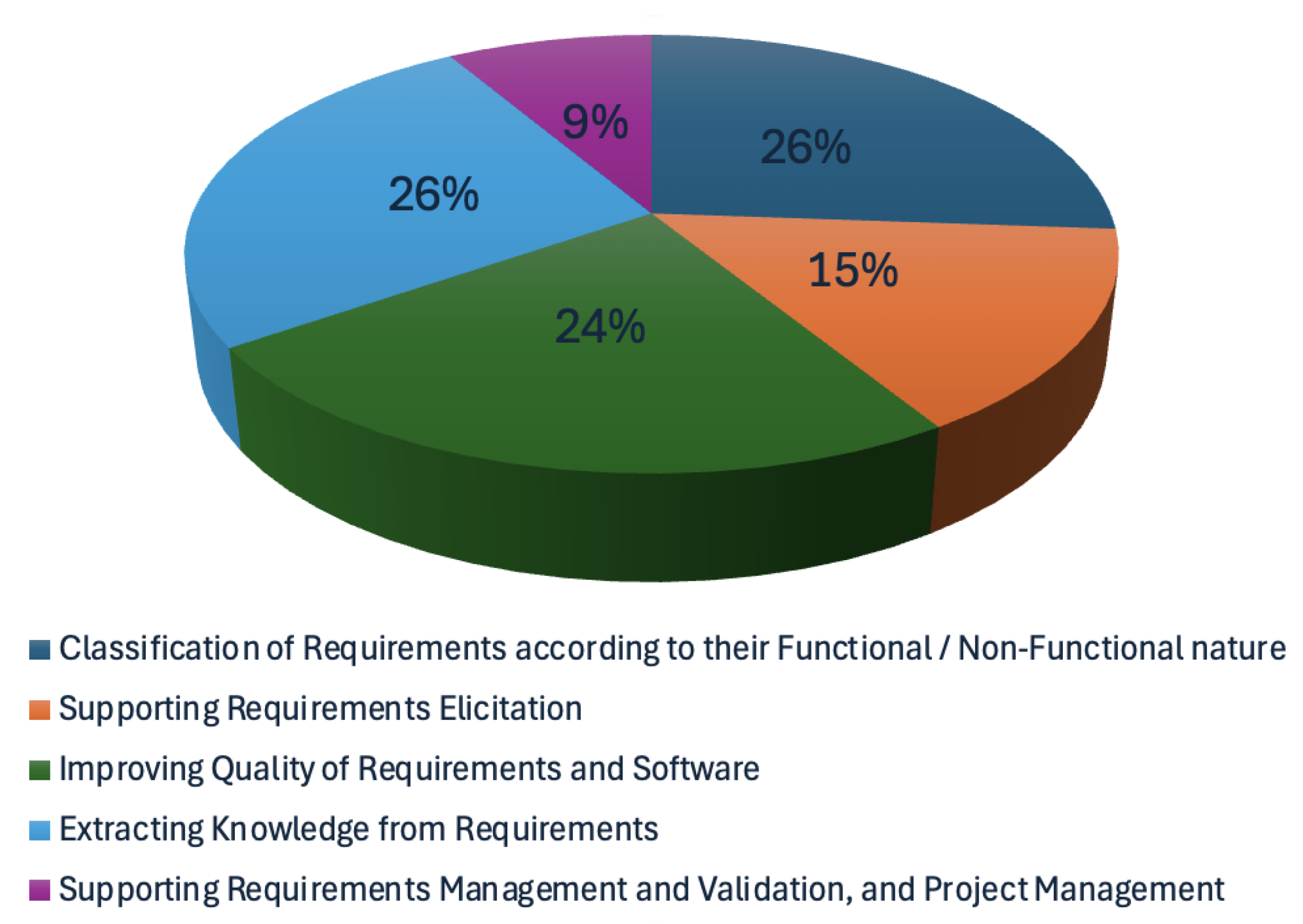

5.2.1. Classification of Requirements according to their Functional/Non-Functional nature

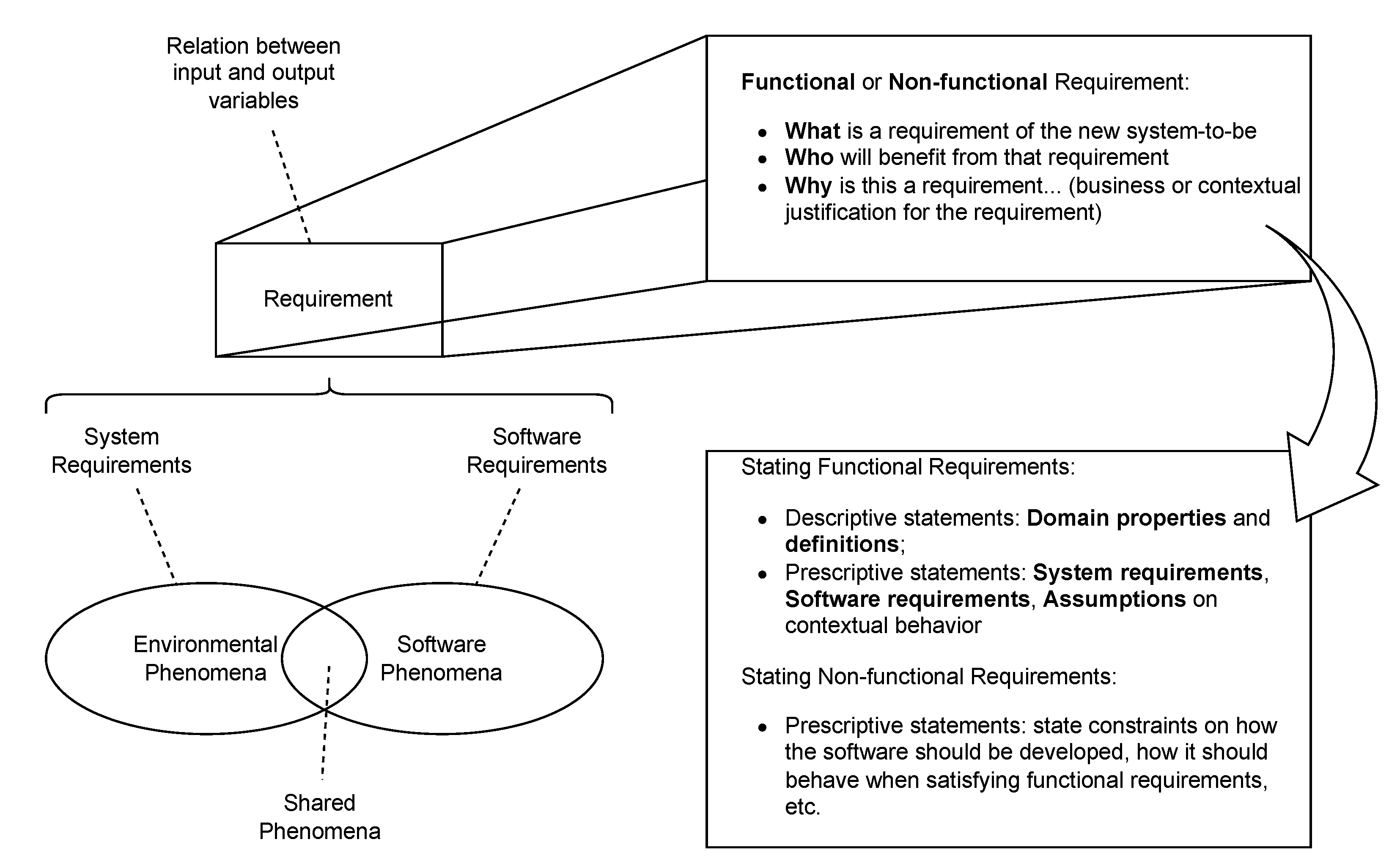

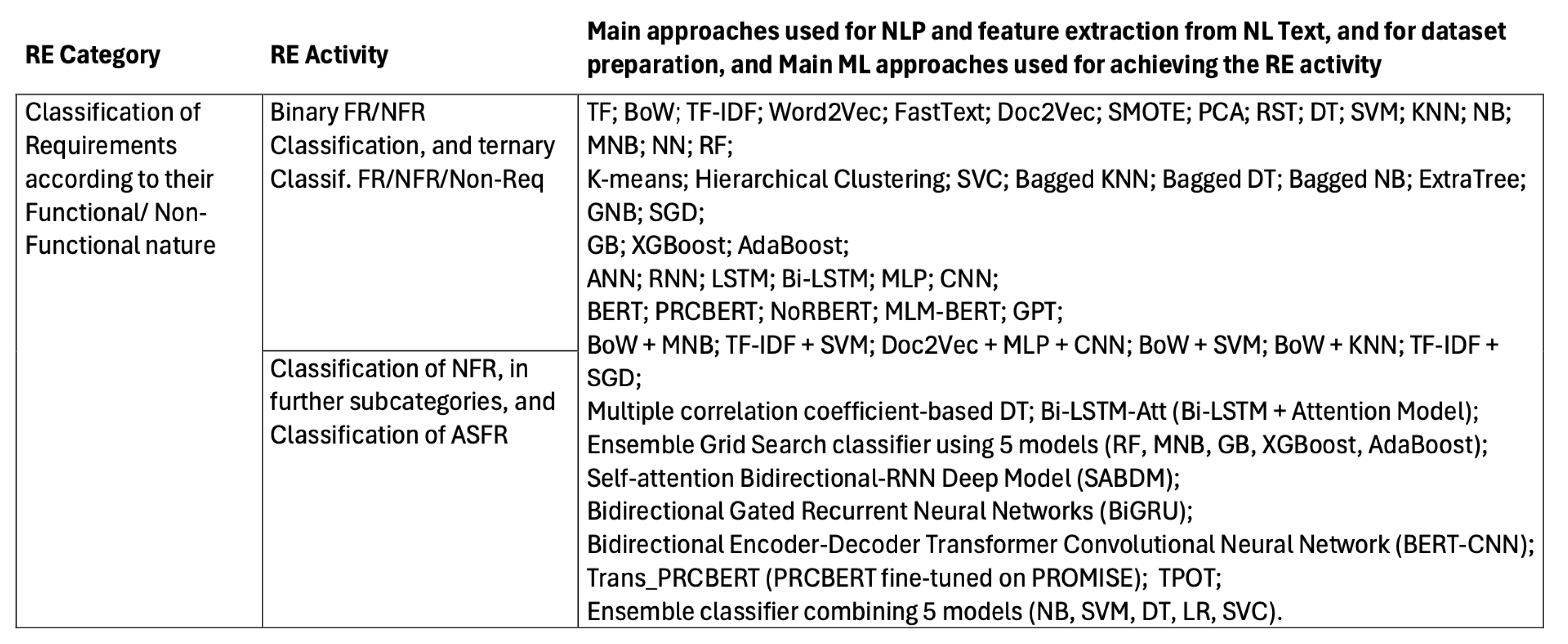

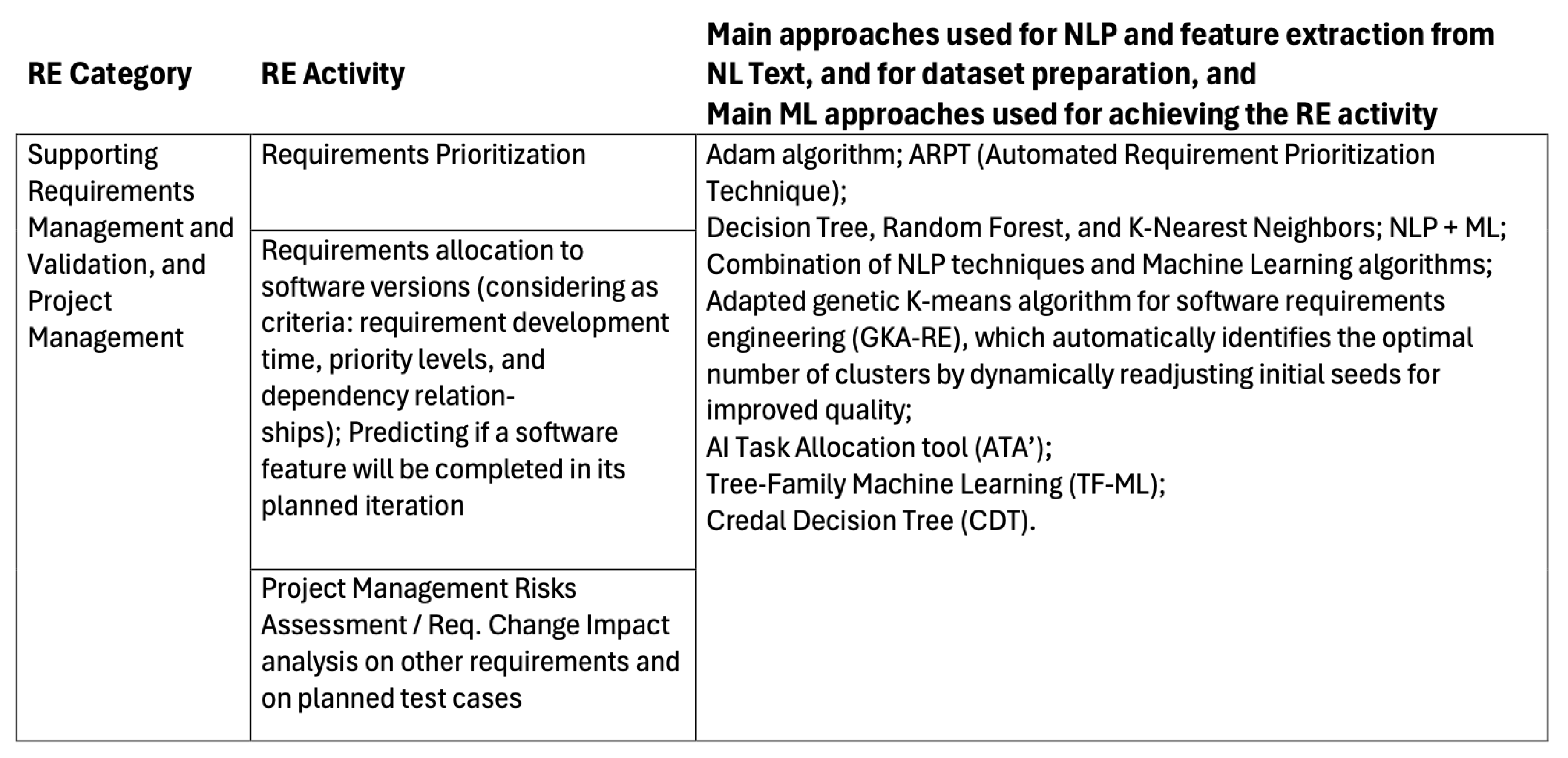

Several ML techniques may be used for classifying Requirements, from natural language text in SRS documents, according to their Functional/Non-Functional nature. In

Table 1, we have separated references that address a binary classification of each requirement as a "Functional Requirement" or a "Non-Functional Requirement", or a ternary classification, where non-requirements are also identified, from the ones that look for a more detailed classification of NFR into their subcategories, or also try to identify Architecturally Significant Functional Requirements (ASFR), which are requirements with important information for taking architectural decisions.

Classifying requirements into functional, non-functional and other categories involves several steps, from preprocessing and feature extraction to model training and evaluation. At its early stage, NLP is the main issue. For this, techniques such as tokenization and lemmatization may be used to preprocess the requirements text and transform it to numerical feature values. Once the requirements text is preprocessed and transformed into numerical feature vectors, a classification algorithm can be applied.

In

Table 2, the main approaches for the early NLP phase, and the main ML-based approaches to the classification of Requirements according to their Functional/Non-Functional nature, are presented. As depicted in the table, several techniques are reported in the reviewed literature. In this section, the techniques used in each reference reviewed, which are present in

Table 2, are summarized.

The authors in [

33] studied several ML approaches to distinguish between FR and NFR. Their approach included data cleansing, normalization and text preprocessing and vectorization steps, in which BoW, Term frequency-inverse document frequency (TF-IDF), Featurization and Machine Learning Models, ROC and AUC curves, Bi-Grams and n-Grams in Python, Word2Vec, and confusion matrix were used. According to the authors, the combination of BoW and MNB provided the best performance for binary classification.

The authors in [

34] argue that existing techniques for classifying FR and NFR consider only one feature at a time, thus not being able to consider the correlation of two features, and so they are biased. In their study, they compare and extend ML algorithms to classify requirements, in terms of precision and accuracy, and have observed that DT algorithm can identify different requirements and outperform existing ML algorithms. As the number of features increases, the accuracy using the DT is improved by 1.65%. To address DT’s limitations, they propose a multiple correlation coefficient based DT algorithm. This approach, when compared to existing ML approaches, improves classification performance. The accuracy of the proposed algorithm is improved by 5.49% compared to the DT algorithm.

In [

36], the authors have used a zero-shot learning (ZSL) approach for classifying requirements into Functional and Non-Functional requirements, and to identify NFR categories, including security non-functional requirements, without using any labeled training data. The study shows that the ZSL approach achieves an F1 score of 0.66 for the FR/NFR classification task. For the NFR task, the approach yields a F1-score between 0.72 and 0.80, considering the most frequent classes.

In [

37], TF-IDF and Word2Vec were the feature extraction techniques used after the NL text pre-processing phase. The study then compared different ML algorithms to assess their precision and accuracy in classifying software requirements, namely DT, RF, LR, Neural Networks (NN), KNN and SVM. The results showed that the TF-IDF feature selection algorithm performed better than the Word2Vec algorithm, in subsequent classification algorithms.

The study in [

38] implemented an ensemble technique using Grid Search classifier that can automatically tune the best parameters of the low performed classifier. The objective was to use a fine-tuned Ensemble technique combining five different models, namely RF, MNB, Gradient Boosting, XGBoost, and AdaBoost, to classify software requirements into FR or NFR.

The study in [

40] used a RNN based model, namely Bidirectional Long Short-Term Memory (Bi-LSTM). This algorithm combines the forward and backward hidden layers to solve the sequential task better than LSTM. By combining Bi-LSTM and self-attention mechanism, the authors noticed an improved requirements classification accuracy. The Bi-LSTM model has been trained with the GloVe model. The architecture proposed in [

40], named Self-attention based Bidirectional-RNN Deep Model (SABDM), integrates NLP, Bi-LSTM, and self-attention mechanism, and has been developed for improving the performance of deep learning in classifying requirements, both FR/NFR categorizations and within NFR categories.

Most studies deal with requirements classification as binary or multiclass classification problems and not as multilabel classification, which would allow a requirement to belong to multiple classes at the same time. As a way of minimizing preprocessing and to enable multilabel classification of requirements, in [

41] a recurrent neural networks-based deep learning system has been used, namely Bidirectional Gated Recurrent Neural Networks (BiGRU). The authors have investigated the usage of word sequences and character sequences as tokens. Using word sequences as tokens has achieved results similar to the state-of-the-art, effectively classifying requirements into functional and different non-functional categories with minimal text prepossessing and no feature engineering.

The authors in [

43] propose an automated non-exclusive approach for classification of functional requirements from the SRS, using a deep learning framework. They found that domain-specific terms, used in requirements specification, cause a number of issues with requirements engineering methods. An NLP pipeline is proposed, for categorizing functional requirements from the SRS into several types. They have used MLP and CNN in the classification model’s development, after using Word2Vec and FastText word embeddings from SRS documentation. Along with the word vectors inferred from the pre-trained Word2Vec and FastText word vectorizers, the Doc2Vec model was used to vectorize the sentences in the used SRS documents. The word vectors were produced using pre-trained online embedding and re-training the current embedding model using internal data. The impact of data trained with Word2Vec and FastText was compared to pre-trained word embeddings models, available online. The retrained vector classifier models outperformed an initial vector model in terms of accuracy. The best accuracy was achieved by the retrained vector CNN classifier model (77%).

In [

44], the authors have used Term Frequency, BoW and TF-IDF, together with four supervised and two unsupervised machine learning algorithms for classifying requirements specifications into FR and NFR. When using BoW, the authors observed an accuracy of 0.725 with K-Nearest Neighbors (K-NN), 0.835 with Support vector machines (SVM), 0.849 with Logistic Regression (LR), 0.543 with K-means, 0.839 with multi-naive bayes, and 0.560 with Hierarchical clustering. Accuracy achieved with agglomerative clustering using TF-IDF was 0.797 with K-NN, 0.876 with SVM, 0.845 with LR, 0.470 with K-means, 0.856 with Multinominal Naive bayes. The authors conclude that, for better results, it is best to combine SVM algorithm with TF-IDF. The authors also conclude that ML algorithms are suitable for classifying requirements on simple problems, but that for addressing larger problems it is necessary to apply rules-based AI models.

The research reported in [

45] presents a Bidirectional Encoder-Decoder Transformer-Convolutional Neural Network (BERT-CNN) model for requirements classification. The convolutional layer is stacked over the BERT layer for performance enhancement. In order to extract features from requirement statements the study employs CNN in task-specific layers of BERT. Experiments using the PROMISE dataset evaluated the solution’s performance through multi-class classification of four key classes: Operability, Performance, Security, and Usability. Results showed that the BERT-CNN model outperformed the standard BERT approach when compared to existing baseline methods.

The studies in [

46,

53] use five distinct word embedding techniques for classifying FR and NFR (quality) requirements. Synthetic Minority Oversampling technique (SMOTE) is used to balance classes in the dataset used. Some dimensionality reduction techniques are also used, namely Principal Component Analysis (PCA), which is used for reducing dimension, and Rank-Sum test (RST), which is used for feature selection, to eliminate redundant and irrelevant features. Then, the vectors resulting from the word embedding techniques used have been provided as inputs to eight different classifiers for requirements categorization: Bagged k-Nearest Neighbors, Bagged Decision Tree, Bagged Naive-Bayes, Random Forest, Extra Tree, Adaptive Boost, Gradient Boosting, and a Majority Voting ensemble classifier, with DT, KNN, and Gaussian Naive Bayes (GNB). The authors conclude that the combination of word embedding and feature selection techniques with the various classifiers are successful in accurately classifying functional and quality software requirements [

46,

53].

In [

47], the use of PRCBERT, or Prompt learning for Requirement Classification using BERT, is proposed. This approach applies flexible prompt templates to classify software requirements from small-sized requirements datasets (PROMISE and NFR-Review), and then adopts it to auto-label unseen requirements’ categories of their collected large-scale requirement dataset NFR-SO. Experiments conducted on PROMISE and NFR-Review datasets and on a large-scale requirement dataset collected by the authors, enables to conclude that PRCBERT exhibits moderately better classification performance than NoRBERT and MLM-BERT (BERT with the standard prompt template). On the de-labeled datasets, Trans_PRCBERT (a PRCBERT version fine-tuned on PROMISE) has a zero-shot performance with 53.27% and F1-score of 72.96%, when enabling a self-learning strategy.

In [

48], the authors propose applying ML and active learning (AL) to classify requirements in a given dataset, introducing the MARE process, which utilizes Naïve Bayes as the classifier. AL employs uncertainty sampling strategies to determine which data points should be labeled by the "oracle". Three AL strategies are explored: Least Confident (LC), Margin Sampling (MS), and Entropy Measure (EM). Experiments using two datasets were conducted to evaluate the performance of the MARE process. The findings suggest that better organization and documentation of requirements improve classification results. However, significant progress is still needed to develop a system capable of categorizing requirements with minimal human intervention at different levels of abstraction.

The work in [

49] presents a proposal for the automated classification of quality requirements. The study involved the training and hyperparameter optimization of different ML models, with the user feedback classification. The study leverages the inherent knowledge of software requirements to train various ML algorithms using NLP techniques for information reuse, extraction, and representation. The Tree-based Pipeline Optimization Tool (TPOT), an AutoML library developed by Olson et al. [

156], which uses genetic algorithms, was employed to optimize ML models, improving fitness scores by up to 14%. TPOT achieved the highest weighted geometric mean (0.8363), followed by Random Forest (0.82). However, applying these models to informal text requirements proved challenging, as automated classifiers struggled to achieve results above 0.3, highlighting the gap between machine and human classification performance.

The authors in [

50] propose a technique to automatically classify software requirements using ML to represent text data from software requirements text and classify them as FR or NFR, based on BoW followed by SVM or KNN algorithm for classification. They experimented with the PROMISE_exp dataset, which includes labeled requirements, and observed that the use of BoW with SVM is better than to use KNN algorithms with an average F-measure of all cases of 0.74.

The study in [

51] looks for the automatic categorization of user feedback reviews into functional requirements and non-requirements. The study evaluates ML based models to identify and classify requirements from both formally written SRS documents and free text App Reviews written by users. Similarly to other approaches, the work uses ML algorithms (SVM, SGD, and RF) to identify and classify requirements, combined with NLP techniques, namely TF-IDF, to pre-process the requirements text.

In [

52], an analysis of supervised ML models combined with NLP techniques is proposed to classify FRs and NFRs from large SRS. Experiments were conducted on the PROMISE dataset, in two phases: first, the focus was on distinguishing between FRs and NFRs; then, the aim was to classify NFRs into nine specific subcategories. The results show that SVM with TF-IDF achieved the best performance for FR classification, while SGD with TF-IDF was most effective for NFR classification. For subclassifying NFRs, SVM with TF-IDF yielded the best results for Availability, Look & Feel, Maintainability, Operational, and Scalability. Meanwhile, SGD with TF-IDF performed best for Security, Legal, and Usability, whereas RF with TF-IDF excelled in classifying Performance-related NFRs.

In [

54], a new ensemble ML technique is proposed, combining different ML models and using enhanced accuracy as a weight in the weighted ensemble voting approach. The five combined models were NB, SVM, DT, LR, and Support Vector Classification (SVC). When using the ML based classifiers with the highest accuracies (SVM, SVC, and LR) these yielded the same accuracy of 99.45% with the proposed ensemble, only the time improved when using a smaller number of classifiers.

In [

55], the authors propose Requirements-Collector, a tool for automating the identification and classification of FRs from requirements specification and user feedback analysis. The Requirements-Collector approach involves ML and DL computational mechanisms. These components are intended to extract and pre-process text data from datasets of previous works, containing requirements, and then classify FR and NFR requirements. Preliminary results have shown that the proposed tool is able to classify RE specifications and user review feedback with reliable accuracy.

The work in [

60], proposes an approach for classifying ASFRs, which are FR that contain comprehensive information to aid architectural decisions, and thus have a significant impact on the system’s architecture. ASFRs are hard to detect, and if missed, can result in expensive refactoring efforts in later stages of software development. The work presents experiments with a deep learning-based model for identifying and classifying ASFRs. The approach (Bi-LSTM-Att) applies a Bi-LSTM to capture the context information for each word in the software requirements text, followed by an Attention model to aggregate useful information from these words in order to get the final classification. For ASFR identification, the Bi-LSTM-Att model yielded an f-score of 0.86, and for ASFR classification an f-score of 0.83, on average [

60]. The authors also noted that Bi-LSTM-Att outperformed the baseline RAkEL NB classifier for all the labels, with industrial size datasets, although RAkEL NB seems to perform well on less data.

In [

56], the authors propose an intelligent chatbot for keeping a conversation with stakeholders in NL and automating the requirements elicitation and classification yielding formal system requirements from the interaction. Afterwards, a classifier classifies the elicited requirements into FR and NFR. The collected requirements are written in unstructured free flow English sentences, which are pre-processed to identify requirements, through the use of NLP and Dialogue Management, Rasa-NLU and Rasa-Core opensource frameworks. After requirements elicitation by the Chatbot, two classifiers have been implemented, MNB and SVM, to categorize the elicited requirements into FR and NFR. The results show that MNB has better Accuracy, Precision, Recall and F1-Score than SVM (0.91 vs 0.88 in all performance indicators) [

56].

The authors in [

61] research the application of two types of neural network models, an ANN and a CNN, to classify NFRs into five categories: maintainability, operability, performance, security and usability. The authors have evaluated their work on two widely used datasets with approximately 1,000 NFRs. The results show that the implemented CNN model can classify NFR categories with a precision ranging between 82% and 94%, a recall indicator between 76% and 97%, and an F-score between 82% and 92%.

In [

57], RF and gradient boosting algorithms are explored and compared, to determine their accuracy in classifying functional and non-functional requirements. RF and gradient boosting are ensemble algorithms in ML. These combine the results from multiple base or weak learners to produce a final prediction, enabling to improve accuracy and other indicators of prediction performance. Experimental results show that the gradient boosting algorithm has improved prediction performance better than random forest, when classifying NFR. However, the random forest algorithm is more accurate in classifying FR.

In [

58], the efficacy of ChatGPT in several aspects of software development is assessed. For requirements analysis, the ChatGPT’s proficiency in identifying ambiguities, distinguishing between FR and NFR, and generating use case specifications, has been evaluated. The assessment, which has been qualitative and subjected to the authors’ opinion, revealed that ChatGPT has potential in assisting various activities throughout the SDLC, including requirements analysis, domain modeling, design modeling, and implementation. The study also identified non-trivial limitations, such as a lack of traceability and inconsistencies among produced artifacts, which require human involvement. Overall, the results suggest that, when combined with human developers to mitigate the limitations, ChatGPT can serve as a valuable tool in software development [

58].

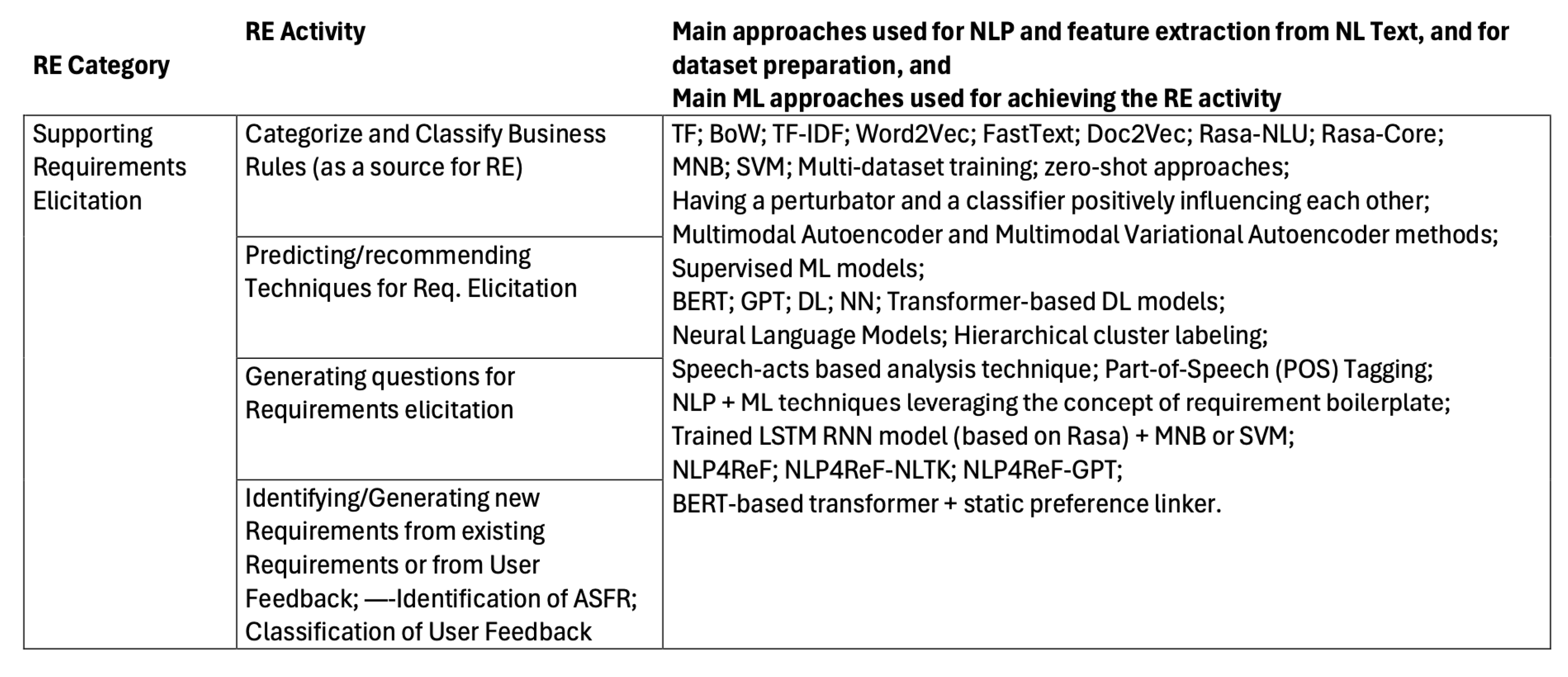

5.2.2. Supporting Requirements Elicitation

Requirements Elicitation is a Requirements Engineering Phase, or set of activities, that deals with capturing, identifying and registering requirements. It helps to derive and extract information from stakeholders or other sources. It is an essential phase in building commercial software.

Table 3, presents the main approaches for the NLP phase, along with the main ML-based approaches for supporting Requirements Elicitation. The table illustrates the techniques reported in the reviewed literature. Each literature reference reviewed, for the "Supporting Requirements Elicitation" category, is summarized in this section.

Business rules, which give body to the description of the business processes, can be an important source of software requirements specifications. The authors in [

62] propose an approach to categorize and classify business rules based on Witt’s approach, which classifies business rules into four main categories: definitional (or structural) rules, data rules, activity rules, and party rules [

62]. They conclude that the proposed approach showed good accuracy, recall, and F1-scores values, when compared to the state-of-art approaches [

62].

The elicited requirements list resulting from the requirements elicitation phase is used as input for requirements analysis and management activities. Multiple elicitation techniques may be applied alternatively or in conjunction with other techniques to accomplish the elicitation. The prediction or recommendation of the best technique for requirements elicitation influences the requirements engineering approach. The authors in [

63] analyze the current practices of requirements elicitation techniques application in practical software development projects, and define factors influencing the technique selection based on the two-classification ML model, and predict the usage of a particular elicitation technique depending on the project attributes and business analyst background. They conducted a survey study involving 328 specialists from Ukrainian Information Technology (IT) companies. Gathered data was used to build and evaluate the prediction models.

According to the authors in [

64], integrating advanced models like GPT-3.5 into RE remains largely unexplored. With the goal of exploring the capabilities and limitations of GPT-3.5 in software requirements engineering, the research presented in [

64] investigates the effectiveness of GPT-3.5 in automating key tasks within RE. The authors identify the limitations of using GPT-3.5 in the requirement-gathering process and conclude that GPT-3.5 demonstrates proficiency in aspects like creative prototyping and question generation, but has limitations in areas like domain understanding and context awareness. The authors offer recommendations for future research focusing on the seamless integration of GPT-3.5 and similar models into the broader framework of software requirements engineering [

64].

As previously mentioned in [

56], an approach to automate requirements elicitation and classification is proposed. The idea is to use an intelligent conversational chatbot. The chatbot converses with stakeholders in Natural Language and elicits formal system requirements from the interaction, and then a classifier classifies the elicited requirements into FR and NFR. Rasa-NLU and Rasa-Core opensource frameworks are used in the chatbot for natural language processing. For the dialogue management, a Rasa Core model is trained with a training data file consisting of several sample user and bot conversations, where the user response is represented by its intent, and the bot response is represented by the bot’s utterance and actions taken [

56]. The result is a trained LSTM RNN model capable of interpreting dialogue history and converting raw dialogue data into a probability distribution over system actions. These actions are defined either as the bot’s textual responses to the user or as code that identifies system requirements from the user’s input, extracts relevant entities, requests additional information if needed, writes the requirement to file, and maintains a natural language conversation with the user. The elicited system requirements are subsequently classified into FR and NFR categories using a text classification model trained on over eight hundred labeled samples from multiple domains. The input data is represented as feature vectors using the BoW method and TF-IDF frequency, which are then employed by text classification models developed using MNB and SVM algorithms [

56]. The authors note that the chatbot has been trained to capture a limited set of requirements within a single domain and requires further extensive training data to recognize a complete set of system requirements. In what respects the MNB and SVM classifiers, the authors conclude that the first has better performance (Accuracy, Precision, Recall, and F1-Score) than the second in classifying FR and NFR [

56].

Addressing requirements defects during the RE phase is more cost-effective than during development of after project delivery. In [

35], the use of Natural Language Processing for Requirements Forecasting (NLP4ReF) is introduced. The authors’ goal is to reduce missing and incorrectly expressed requirements, in order to minimize the number of requirement changes during the SDLC, and ensuring that requirements accurately reflect stakeholder needs. The NLP4ReF approach enables enhancing the process of requirements elaboration using ML and NLP, including the initial requirements organization, their classification as FR or NFR, the identification of system classes, and the generation of forgotten or unforeseen requirements [

35]. The paper explores using NLP4ReF algorithms, namely NLP4ReF-NLTK and NLP4ReF-GPT, in the RE process, to evaluate their efficacy in requirements generation and classification, and to analyze their practical application. The algorithms were able to generate many new relevant requirements, and to effectively classify requirements into FR/NFR. The research highlights the importance of Model-Based Systems Engineering (MBSE) in guiding the development and optimization of algorithms, providing a logical framework for future research in the field of Natural Language Processing for Requirements Engineering (NLP4RE). The authors conclude that the systematic integration of MBSE, through the incorporation of various diagrams that underpin the development of the algorithms, provides comprehensive insights into the study. MBSE contributed to a deeper understanding of the capabilities and implications of NLP4ReF and NLP4RE tools and techniques in RE.

Besides addressing requirements classification between FR/NFR, as seen in

Section 5.2.1, the authors in [

51] also seek to automate the process of extracting functional requirements and filtering out non-requirements from user app reviews. Their proposal evaluates ML-based models to identify and classify software requirements from both, formal Software SRS documents and Mobile App User Reviews. Initial evaluation of the ML-based models show that they can help classify user app reviews and software requirements as FR, NFR, or Non-Requirements.

The research in [

55], already mentioned before when addressing requirements classification, also intends to automatically identify, extract and pre-process text containing requirements and user feedback, to generate requirements specification. The proposed Requirements-Collector tool uses ML and DL based approaches to automatically classify requirements discussed in RE meetings (stored in the form of audio recordings) and textual feedback in the form of user reviews. The authors argue that the Requirements-Collector tool has the potential to renovate the role of software analysts, which can experience a substantial reduction of manual tasks, more efficient communication, dedication to more analytical tasks, and assurance of software quality from conception phases [

55].

Developers frequently elicit requirements from user feedback, such as bug reports and feature requests, to help guide the maintenance and evolution of their products [

65]. By linking feedback to their existing documentation, development teams enhance their understanding of known issues, and direct their users to known solutions. The authors in [

65] apply deep-learning techniques to automatically match forum posts with related issue tracker entries, using an innovative clustering technique. Strong links between product forums, issue trackers, and product documentation, have been observed, forming a requirements ecosystem that can be enhanced with state-of-the-art techniques to support users and help developers elicit and document the most critical requirements [

65].

Studies to elicit stakeholder preferences have been developed in [

66], using scenarios where users describe their goals for using directory services to find entities of interest, such as apartments, hiking trails, etc. The article’s results reveal that feature support for preferences varies widely among directory services, with around 50% of identified preferences unmet. The study also explored automatic preference extraction from scenarios using named entity recognition across three approaches, with a BERT-based transformer achieving the best results (81.1% precision, 84.4% recall, and 82.6% F1-score on unseen domains). Additionally, a static preference linker was introduced, linking extracted entities into preference phrases with 90.1% accuracy. This pipeline enables developers to use the BERT model and linker to identify stakeholder preferences, which can then inform improvements and new features to better address gaps in service.

In [

67], ML classifiers are used to classify bug reports and feature requests using seven datasets from previous studies. The authors evaluate classifiers’ performance on users’ feedback from unseen apps and entirely different datasets, and they assess the impact of channel-specific metadata. They find that using metadata as features in classifying bug reports and feature requests rarely improves performance, and while classification is similar for seen and unseen apps, classifiers struggle with unseen datasets. Multi-dataset training or zero-shot approaches can somewhat alleviate this issue, with implications on user feedback classification models for extracting software requirements.

In [

68], the authors propose an approach to creatively generate requirements candidates via the adversarial examples resulted from applying perturbations to the original requirements descriptions. In the presented architecture, the perturbator and the classifier positively influence each other. Each adversarial example is uniquely traceable to an existing feature of the software, instrumenting explainability. The experimental evaluation has used six datasets, and shows that around 20% adversarial shift rate is achievable [

68].

Several works investigate which techniques and ML models are most appropriate for detecting relevant users feedback and reviews, and for classifying, embedding, clustering, and characterizing those reviews for generating requirements across multiple feedback platforms and data domains [

69,

70,

71,

72,

73,

74,

76].

The study in [

69] explores unimodal and multimodal representations across various labeling levels, domains and languages to detect relevant app reviews using limited labeled data. It introduces a one-class multimodal learning method requiring labeling only relevant reviews, thus reducing the labeling effort. To enhance feature extraction and review representation with fewer labels, the authors propose the Multimodal Autoencoder and the Multimodal Variational Autoencoder methods, which learn representations that combine textual and visual information based on reviews’ density. Density information can be interpreted as a summary of the main topics or clusters extracted from the reviews [

69]. The studied methods achieved competitive results using just 25% of labeled reviews compared to models trained on complete datasets, with multimodal approaches reaching the highest F1-Score and AUC-ROC in twenty-three out of twenty-four scenarios.

In [

70], the authors investigate whether enterprise software vendors can elicit requirements from their sponsored developer communities through data-driven techniques. The authors collected data from the SAP Community and developed a supervised machine learning classifier for automatically detecting feature requests of third-party developers. Based on a manually labeled data set of 1,500 questions, the proposed classifier reached a high accuracy of 0.819. Their findings reveal that supervised machine learning models may be an effective means for the identification of feature requests.

In [

71], the authors propose using the state-of-the-art transformer-based DL models for automatically classifying sentences in a discussion thread. The authors propose a benchmark to ensure standardized inputs for training and testing for this problem. They conclude that their transformer-based classification proposal significantly outperforms the state-of-the-art [

71].

The approach presented in [

73] proposes a hierarchical cluster labeling method for software requirements that leverages contextual word embeddings. This method addresses previous issues such as duplicate requirements from user reviews and the challenges of handling different granularity levels that obscure hierarchical relationships between software requirements. The authors use neural language models to create semantically rich representations of software requirements, clustering them into groups and subgroups based on similarity in the embedding space. Representative requirements are then selected to label each cluster and sub-cluster, effectively managing duplicate entries and different granularity levels [

73].

Within the RE process of defining, documenting, and maintaining software requirements, the authors in [

74] focus on the problem of automatic classification of CrowdRE into sectors. CrowdRE involves large scale user participation in RE tasks. The authors proposal involves three different approaches for sector classification of CrowdRE, based on supervised ML models, NN, and BERT, respectively. Classification approaches have been applied to a CrowdRE dataset, comprising around 3000 crowd-generated requirements for smart home applications. The obtained performance is similar to several other classification algorithms, indicating that the proposed algorithms can be very useful for categorizing crowd-based requirements into sectors [

74].

Although initial progress has been made in using mining techniques for requirements elicitation, it remains unclear how to extract requirements for new apps based on similar existing solutions and how practitioners would specifically benefit from such an approach.

In [

76], the authors focus on exploring information provided by the crowd about existing solutions to identify key features of applications in a particular domain. The discovered features and other related influential aspects (e.g. ratings) can help practitioners to identify potential key features for new applications [

76]. The authors present an early conceptual solution to discuss the feasibility of their approach.

User reviews from tweets, app forums, etc. are processed by applying NL techniques to filter out irrelevant data, followed by text mining and ML algorithms to classify them into categories like bug reports and feature requests. The research in [

77] explores a linguistic technique based on speech-acts for the analysis of online discussions with the goal of discovering requirements-relevant information. A revised version of the speech-acts based analysis technique, previously presented by the same authors, is proposed together with a detailed experimental characterization of its properties. Datasets used in the experimental evaluation were taken from an open source software project (161120 textual comments) and from an industrial project in the home energy management domain. On these datasets, the proposed approach is able to successfully classify messages into Feature/Enhancement and Other, with F-score of 0.81 and 0.84 respectively. The authors conclude that evidence of an association between types of speech-acts and categories of issues, has been found, and that there is correlation between some of the speech-acts and issue priority.

To advance software creativity, several techniques have been proposed, such as multi-day workshops with experienced requirements analysts and semi-automated tools that support focused creative thinking. The authors in [

75,

78] propose a novel framework for providing an end-to-end automation to support creativity in both new and existing systems. The framework reuses requirements from similar software freely available online, uses advanced NLP and ML techniques, and leverages the concept of requirement boilerplate to generate candidate creative requirements. The framework has been applied on three application domains: Antivirus, Web Browser, and File Sharing, and further report a human subject evaluation. The results exhibit the framework’s ability to generate creative features even for a relatively matured application domain, such as Web Browser, and provoke creative thinking among developers irrespective of their experience levels.

Software companies need to quickly fix reported bugs and release requested new features, or they risk negative reviews and reduced market share. The sheer volume of online user feedback renders manual analysis impractical. The authors in [

79] note that online product forums are a rich source of user feedback that may be used to elicit product requirements. The information contained in these forums often include detailed context to specific problems that users encounter with a software product. By analyzing two large forums, the study in [

79] identifies 18 distinct types of information (classifications) relevant to maintenance and evolution tasks. The authors found that a state-of-the-art App Store tool cannot accurately classify forum data, underlining the need for specialized techniques to extract requirements from product forums. In an exploratory study, they developed classifiers incorporating forum-specific features, achieving promising results across all classifiers, with f-scores ranging from 70.3% to 89.8%.

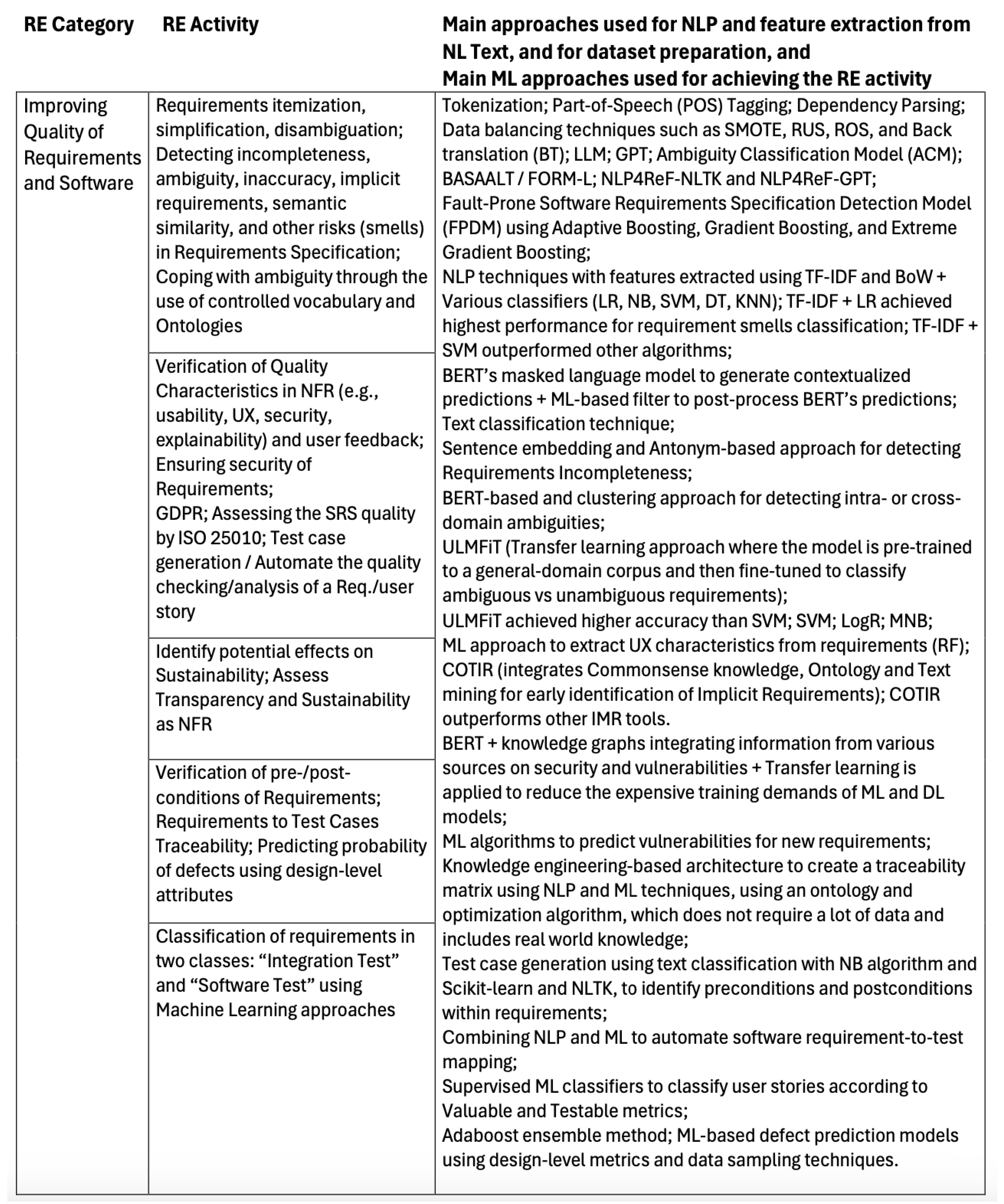

5.2.3. Improving Quality of Requirements and Software

Most software requirements are written using natural language, which has no formal semantics and has a high risk of being misunderstood due to its natural tendency towards ambiguity and vagueness. Improving the quality of requirements and software involves reducing the ambiguity, incompleteness, non-uniqueness and coverage (in terms of users’ needs) of the requirements specification. It also involves, identifying requirements that may have effects of sustainability, security and usability of the future system, besides other quality characteristics. Another way of improving the requirements quality is registering and monitoring their inter-dependencies and pre- and post-conditions.

The quality of the software, and the adherence of planned or developed software features to the stated requirements, may also be addressed through validation tests. These may be, at least partially, drawn from the SRS. And, the probability of defects can also be predicted.

Table 4, presents the main approaches for the NLP phase, along with the main ML-based approaches for improving the quality of requirements and software. The table shown the main techniques reported in the reviewed literature. Each of the references reviewed is summarized in this section.

The work in [

58], mentioned above, also targets the quality improvement of requirements and software. The efficacy of ChatGPT on identifying ambiguities and generating accurate use case specifications, and on fixing errors encountered during the software implementation, has been assessed. As mentioned before, the study also identified a lack of traceability and inconsistencies among produced artifacts, which to not dispense human involvement.

One recurrent difficulty in requirements analysis is requirements itemization, or simplifying/subdividing requirements. This difficulty arises due to the inherent ambiguity and redundancy of requirements described in natural language. It is very important to determine the list of itemized requirements from the requirements document. The work in [

80] proposes a method to automatically extract requirement entries from requirement text by leveraging a set of NLP techniques and machine learning models. The approach tries to imitate the human expert process of extraction of itemized requirements, which consists of three main processes: identifying requirement locations and boundaries, building models, and extracting fine-grained requirement semantics. The authors performed evaluations in the field of military arguments, and the results showed a nearly 80 percent accuracy. The approach can be used to industry practitioners extract requirements items faster and easier.

In [

81], a ML-based approach to formalize requirements written in natural language text is proposed. The approach targets critical embedded systems, and extracts information to assess the quality and complexity of requirements. The authors have used the open source NLP framework spaCy for tokenization, Part-of-Speech (PoS) tagging and dependency parsing based on a pre-trained English language model. Then, a phase for identifying text chunks follows, whuch uses a rule-based exploration approach in contrast to domain-specific training alternative. According to the authors, this is to ensure independence of a specific engineering domain. Text chunks are then put into a normalized order. If this is not possible, a quality issue may be detected. The normalized sequence of chunks can be used for "building test oracles, for the implementation of software, and for applying metrics so that requirements may be compared for similarity or be evaluated" [

81].

In [

82], the authors propose a model to detect fault-prone software requirements specifications, consisting of two main components: (1) an Ambiguity Classification Module (ACM); and, (2) a Fault-Prone Detection Module (FPDM). The ACM selects the best deep learning algorithm to classify requirements as ambiguous or clean, identifying various types of ambiguity (lexical, syntactic, semantic, and pragmatic). Then, the FPDM uses key SRS components, such as title clarity, description, intended users, and the ambiguity classification, to detect fault-prone requirements. The ACM achieved an accuracy of 0.9907 and the FPDM 0.9750. To further enhance detection, particularly for edge/cloud applications, the authors applied boosting algorithms (Adaptive Boosting, Gradient Boosting, and Extreme Gradient Boosting), improving accuracy by leveraging SRS features. They also propose a fault-prone severity scale that categorizes ambiguity as low, moderate, or high based on a calculated score from key SRS elements [

82].

The use of NLP4ReF, proposed in [

35], also targets the disambiguation of requirements specifications. It uses ML and NLP to identify duplicate, incomplete and hidden requirements. NLP4ReF-NLTK and NLP4ReF-GPT algorithms are used to classify requirements and generate new relevant requirements.

Software programs require rigorous testing and verification to prevent defects, and the same applies to requirements, whether elicited or assumed. This involves analyzing both form and semantics. The study in [

83] highlights that fully automating requirement disambiguation is impossible, as human intervention remains crucial. Using the BASAALT method and FORM-L language, the authors formalized requirements to support behavioral simulation, which helps detect issues such as inadequacy (unsuitable requirements), over-ambition (unnecessary requirements with undue complexity and risks), and contradiction (conflicting requirements). This approach involves creating semantically precise and simulable models while integrating missing contextual details. Stakeholders can review these models and simulation results to ensure alignment with intended requirements. BASAALT/FORM-L models represent system requirements, environmental assumptions, and proposed solutions, with verification ensuring that these solutions satisfy specified requirements. However, defects in requirements and assumptions are a common reason for system failures. Beyond ambiguity, inadequacy is a key concern, as unsuitable requirements can lead to undesirable outcomes. FORM-L models support verification through modeling and simulation, leveraging tools like Stimulus for test case generation. A noted limitation of the study is the manual application of BASAALT and FORM-L for identifying ambiguities and formalizing corrected requirements.

To identify and correct poor quality software requirements, the work in [

84] proposes a set of ML models for detecting different kinds of requirement smells and prioritizing them. Requirements smells are characteristics identified in requirements that function as an indicator of ambiguity and vagueness problems in requirements [

84]. The authors discovered that previous approaches to detecting requirement smells face scalability and flexibility issues, and they do not prioritize smells for ordered action. The proposed method identifies ten classes of requirement smells and ranks them based on severity and the importance of the requirements. They used a dataset of 3,100 expert-labeled requirements for both classification and prioritization. Textual requirements were preprocessed with NLP techniques, with features extracted using TF-IDF and BoW. Various classifiers, namely LR, NB, SVM, DT, and KNN, were evaluated, and an additional sorting method was applied for project-specific smell prioritization. As a result, LR with TF-IDF achieved highest performance with 94% accuracy for requirement smells classification. For requirement smells prioritization, SVM outperformed other algorithms with 99% accuracy.

Detecting incompleteness in NL requirements is a major challenge. One approach is to compare requirements with external sources. Given the rise of Large Language Model (LLM)s, the work in [

85] has addressed the question: Are LLMs useful external sources of knowledge for detecting potential incompleteness in NL requirements? The authors explore this question by using BERT’s masked language model to generate contextualized predictions for filling masked slots in requirements. To simulate incompleteness, some content from requirements has been withhold, and BERT’s ability to predict terminology that is present in the withheld content but absent in the disclosed content, has been assessed. BERT can produce multiple predictions per mask. The work contributes to determine the optimal number of predictions per mask, balancing effective identification of omissions in requirements with noise reduction. It also contributes with a a ML-based filter to post-process BERT’s predictions and further decrease noise. An empirical evaluation on 40 requirements specifications from the PURE dataset shows that BERT’s predictions successfully highlight missing terminology, outperforming simpler baselines, while the proposed filter enhances its effectiveness for completeness checking of requirements [

85].

The problem with natural language is that it can easily lead to different understandings if it is not expressed precisely by the stakeholders involved [

86]. This may result in building a product that is not aligned with the stakeholders expectations.

The work in [

86] tries to improve the quality of the software requirements by detecting language errors based on International Standards Organizations (ISO) 29148 requirements language criteria. The proposed solution is based on previous existing solutions, which apply classical NLP approaches to detect requirements’ language errors. In [

86], the authors seek to improve the previous work by creating a manually labeled dataset and using ensemble learning, DL and other techniques, such as word embeddings and transfer learning to overcome the generalization problem that is tied with classical NLP and improve precision and recall metrics using a manually labeled dataset.

The work in [

87] also addresses duality and incompleteness in NL software requirements specification. Different from previous approaches, in [

87] the authors focus on the requirements incompleteness implied by the conditional statements, and propose a sentence embedding and antonym-based approach for detecting the requirements incompleteness. The guiding idea is that when one condition is stated, its opposite condition should also be there, or else the requirements specification is incomplete. Hence, the proposed approach starts by extracting the conditional sentences from the requirements specification, and eliciting the conditional statements which contain one or more conditional expressions. Then, conditional statements are clustered using the sentence embedding technique, and the conditional statements in each cluster are further analyzed to detect potential incompleteness, by using negative particles and antonyms [

87]. The results of the proposed approach have shown a recall of 68.75%, and a F1-measure of 52.38%.

Ambiguity in Requirement Engineering document may lead to disastrous results thereby hampering the entire development process and ending up compromising on the quality of a system. In [

88], the authors discuss the types of ambiguity found in the RE document, and approaches to handle and providing a level of automatic assistance in reducing ambiguity and improving requirements. The study also confirms the use of text classification technique to classify a text as “ambiguous” or “Unambiguous” at the syntax level. The objectives of the work were mainly to identify the presence of ambiguity in any RE document with the help of ML Techniques and finally minimizing or reducing it.

The application of neural word embeddings for detecting cross-domain ambiguities in software requirements has recently gained significant attention. Several methods in the literature estimate how meaning varies for common terms across domains, but they struggle to detect terms used in different contexts within the same domain, i.e., intra-domain ambiguities or those in a requirements document of an interdisciplinary project. The work in [

89] introduces a BERT-based and clustering approach to identify such ambiguities. For each context in which a term appears, the approach provides a list of similar words and example sentences illustrating its context-specific meaning. Applied to both a computer science corpus and a multi-domain dataset covering eight application areas, the approach has proven highly effective in detecting intra-domain ambiguities [

89].

In [

90], the authors have used transfer learning by using ULMFiT, where the model has been pre-trained to a general-domain corpus and then fine-tuned to classify ambiguous vs unambiguous requirements (target task). Back translation (BT) has also been used as a text augmentation technique, to see if it improved the classification accuracy. The proposed model has then been compared with machine learning classifiers like SVM, Logistic Regression (LogR) and MNB, and the results showed that ULMFiT achieved higher accuracy those classifiers, improving the initial performance by 5.371%. The authors conclude that the proposed approach provides promising insights on how transfer learning and text augmentation can be applied to small data sets in requirements engineering.

The work in [

91] addresses identification of implicit requirements (IMRs) in SRS. Implicit requirements are not specified by users, but may be crucial to the success of a software project. A software tool has been developed, called COTIR, which integrates Commonsense knowledge, Ontology and Text mining for early identification of Implicit Requirements. In [

91] the authors demonstrate the tool and conclude that it relieves human software engineers from the tedious task of manually identifying IMRs in huge SRS documents. Performed evaluation shows that COTIR outperforms existing IMR tools [

91].

Semantic similarity information supports requirements tracing and helps to reveal important requirements quality defects such as redundancies and inconsistencies [

92]. The authors in [

92] created a large dataset for analyzing the similarity of requirements, through the use of Amazon Mechanical Turk, a crowd-sourcing marketplace for micro-tasks. Based on this dataset, they investigate and compare different types of algorithms for estimating semantic similarities of requirements, covering both relatively simple bag-of-words and machine learning models. After experiments on their dataset, they conclude that the best performances were obtained by a model which relies on averaging trained word and character embeddings as well as an approach based on character sequence occurrences and overlaps, achieve the best performances.

In [

93], the authors present techniques of NLP which work out greatly to extract information properly and minimizing the bugs that may generate in later parts of Software Development. Using techniques of NL Interpretation, Software Engineers can outline the most accurate requirements of customers, which can improve the quality of requirements, and ultimately of the resulting software product.

There are also several works in the certification of quality characteristics, such as usability, user experience or security. In [

94], a set of system UX Key Performance Indicator (KPI) is predicted based on a list of initial textual requirements. This helps assessing an application’s UX KPI in the first phases of software requirements engineering, without having to develop a UX-oriented prototype at early software requirements elicitation phase. User Experience (UX) reveals users’ product impressions when using or planning to use a software product. The suggested ML approach extracts UX characteristics from textual requirements to categorize them as UX scales, which are then used to forecast the total UX KPI of any software application. The UX predictions should be as reliable as a real case study of different application prototypes. Several machine learning models have been trained on a benchmark dataset of software requirements, showing a f1-measure performance of 0.91, for the RF Algorithm. The authors also observed that the UX KPIs calculated based on outputs from ML models were highly interrelated with those calculated based on developed UX-oriented software prototypes, allowing to conclude that the proposed model can evaluate UX instantly without interventions from end-users or UX designers [

94].

In [

99], a benchmark dataset is built for UX, based on textual software requirements crowdsourcing several UX experts. The paper develops a machine learning model to measure UX based on the dataset. The research describes the dataset characteristics and reports its statistical internal consistency and reliability. Results indicate a high Cronbach Alpha and a low root mean square error of the dataset, which leads the authors to conclude that the new benchmark dataset could be used to estimate UX instantly without the need for subjective UX evaluation. The dataset will serve as a foundation of UX features for machine learning models.

The work in [

95] focuses on ensuring system security is addressed in the requirements management phase rather than leaving it for later phases in the software development process. The authors propose an approach to combine useful knowledge sources like customer conversation, industry best practices, and knowledge hidden within the software development processes. BERT is used in the proposed architecture to utilize its language understanding capabilities. The work also investigates the use of knowledge graphs to integrate information from various industry sources on security practices and vulnerabilities, ensuring that the requirements management team stays informed with critical data. Additionally, transfer learning is applied to reduce the expensive training demands of ML and DL models. The proposed architecture has been validated within the financial domain and agile development models. The authors propose that this approach could effectively integrate software requirements management with data science practices by leveraging the extensive information available in the software development ecosystem.

Software security is also a major concern in the work presented in [

96]. Based on the principle that the root of a system security vulnerability can often be traced back to the requirements specification, the authors advocate a novel framework to provide an additional measure of predicting vulnerabilities at earlier stages of the SDLC. In the study in [

96], the authors build upon their proposed framework and leverage state-of-the-art ML algorithms to predict vulnerabilities for new requirements, together with a case study on a large open-source-software (OSS) system, Firefox, evaluating the effectiveness of the extended prediction module. The results show that the framework could be a viable complement to the traditional vulnerability-fighting approaches.

Complying with the EU GDPR can be a challenge for small and medium-sized enterprises. The work reported in [

97] considers GDPR-compliance as a high-level goal in software development that should be addressed at the beginning of software development, that is, during RE. The authors argue that NLP can be used to automate this process, and present initial work, preliminary results, and the current state of art on verifying requirements’ GDPR-compliance.

In [

98] the authors present a user feedback classifier based on ML for the classification of user reviews according to software quality characteristics compliant with the ISO 25010 standard. The proposed approach has been achieved by testing several ML algorithms, features, and class balancing techniques for classifying user feedback on a data set of 1500 reviews. The maximum F1 and F2 scores obtained were 60% and 73%, with recall as high as 94%. The authors conclude that the proposed approach does not replace human specialists, but helps in reducing the effort required for requirements elicitation.

The study in [

100] reports on the development of a method of activity of ontology-based intelligent agent for evaluating initial stages of the software lifecycle. Based on the developed method, the intelligent agent evaluates whether the information in the SRS is sufficient or not. It provides a numerical assessment of the sufficiency level for each non-functional feature individually and for all features overall, along with a list of attributes (measures) or indicators that should be added to improve the SRS’s completeness or level of sufficiency [

100]. In experiments, the agent analyzed the SRS for a transport logistics decision support system and determined that the information was not sufficient for assessing the quality by ISO 25010 and for assessing quality by metric analysis.

Software developers are gradually becoming aware that their systems have effects on sustainability [

101]. Researchers are currently exploring approaches which strongly make use of expert knowledge to identify potential effects. In the work in progress research reported in [

101], the authors looked at the problem from a different angle: they have worked on the exploration of a ML-based approach to identify potential effects. Such an approach allows to save time and costs but increases the risk that potential effects are overseen. First results of applying the ML-based approach in the domain of home automation systems are promising, but also indicate that further research is needed before the proposed approach can be applied in practice.

The growing complexity and ubiquity of software systems increase user reliance on their correct functioning, which in turn demands that these systems and their decision processes become more transparent. To achieve this, transparency requirements must be clearly understood, elicited, and refined into lower-level requirements [

102]. However, there is still limited understanding of how the requirements engineering process should address transparency, including the roles and interactions among UX designers, data scientists, and other stakeholders. To address this gap, the work in [

102] investigates the requirements engineering process for transparency through empirical studies with practitioners and other stakeholders. Preliminary findings indicate that further research is needed to develop effective solutions that support transparency in requirements engineering.

It is very important to deliver a defect free product that matches all the requirements specified by the client and must pass all the test cases [

103]. To do this systematically, a requirement traceability matrix is used. A Requirement traceability matrix relates two items’ lists in two dimensions. In this case, it shows the relations of all the requirements and the test cases, thus allowing to track the relation between the customer’s requirements for the system and the test cases for validating the requirements. There are many approaches to create an efficient traceability matrix using Language processing and ML techniques but these approaches require a lot of data and do not take care of the real world knowledge and may lead to errors. In [

103], the authors propose a knowledge engineering-based architecture to this problem with the use of ontology, machine learning and optimization algorithm which produces a dependability and steadiness of 97% and 95% respectively and the performance of the proposed model is compared with baseline approaches.

The authors in [

104] propose an approach for test case generation using text classification, using the NB algorithm to identify preconditions and postconditions within software requirements. The approach categorizes software requirements into two categories: "none" and "both", which indicate the presence or absence of preconditions and postconditions in software requirements. The research employs the NB algorithm, a widely used probabilistic classification algorithm in text classification tasks [

104]. It uses two libraries, namely Scikit-learn and Natural Language Toolkit (NLTK). The best accuracy score, which was obtained by the Scikit-learn model, was 0.86, which demonstrates the feasibility of reducing the effort and time required for classifying test case components based on software requirements. The proposed approach not only streamlines the identification of essential components in software requirements but also opens up possibilities for further automation and optimization of the testing process [

104].

Accurate mapping of software requirements to tests is critical for ensuring high software reliability [

105]. The dynamic nature of software requirements demands that these are traceable and measurable throughout the SDLC, in order to be able to plan software tests and integration tasks, during the development phase, and the evaluation and verification tasks, or the application of patches, during the operation phase. To address these challenges, a novel method is proposed in [

105], combining NLP and ML to automate software requirement-to-test mapping. The proposed method formalizes the process of reviewing the recommendations generated by the automated system, enabling engineers to improve software reliability, and reduce cost and development time [

105].

In Agile software project management methodologies, user requirements are frequently stated in the form of user stories, the smallest semi-structured specification units of user requirements. In [

106], two metrics are applied in validating user stories: Testable and Valuable criteria from INVEST checklist

1. The authors have applied supervised machine learning classifiers to automatically classify user stories according to those metrics. They have used industrial collected data for their dataset and applied the developed classifiers, having observed good values of accuracy and precision. After balancing the dataset, using data balancing techniques such as SMOTE, RUS, ROS, and Back translation (BT), the authors observed that, despite not seeing significant improvements in accuracy and precision, a significant improvement has been obtained in recall values across all the classifiers [

106]. The research provides some promising insights into how the analysis of user stories can be used by the software industry to improve the quality of the software produced.

Providing automatic requirement analysis techniques for modeling and analyzing requirements is a must for saving manpower. In [

107], a cloud service method for automated detection of quality requirements in SRS is proposed. The study also presents a novel approach for processing automatic classification of software quality requirements based on supervised machine learning techniques applied for the classification of training document and predict target document software quality requirements.

Approaches aiming to minimize the vulnerabilities in the software have been dominated by static and dynamic code analysis techniques, often using machine learning (ML). These techniques are designed to detect vulnerabilities in the post-implementation stage of the SDLC [

96]. Accommodating changes after detecting a vulnerability in the system in later stages of the SDLC is very costly, sometimes even infeasible as it may involve changes in design or architecture. In [

96], a framework to provide additional measures of predicting vulnerabilities at earlier stages of the SDLC is proposed.

In [

108], a method for automatically generating test cases, for system testing and acceptance testing, from requirements is studied. The authors propose training data selection quality improvement technique in the cosine similarity with the test data, and have confirmed the effectiveness of the methods. A second method has also been proposed that adds the application judgment technique by the standard deviation value. The proposed methods have obtained the maximum value of accuracy with less training data.

Software used in communication systems is increasingly becoming more complex and larger in scale to accommodate various service requirements. Since telecom carrier networks serve as basic social infrastructures, it is important to maintain their reliability and safety as a critical lifeline [

109]. The implementation of numerous quality improvement measures, however, has resulted in prolonged development periods and higher costs. To address these issues, the authors in [

109] have been working on the automation of software testing, as this process has great influence in software quality. Typically, test cases are written by skilled engineers and are decided after multiple reviews, requiring a large amount of manpower in preparing them. The study in [

109] has used the knowhow of skilled engineers in writing test cases as training data to automate the generation of homogeneous test cases through machine learning. The proposed method automatically extracts homogeneous test cases that are not dependent on skills and knowhow of the engineer writing the test cases from requirements specification documents. However, the required accuracy cannot be obtained by applying simple machine learning. To improve learning efficiency per unit of training data, without having to expand the training data, as the available quantity of requirements specifications is limited, and this would increase cost, the authors propose a method to increase accuracy through the preparation of training data inputted into the machine learning process, and conclude on the effectiveness of the method [

109].

Model analytics for defect prediction allows quality assurance groups to build prediction models earlier and to predict the defect-prone components before the testing phase for in-depth testing [

110]. In [

110], it is shown that ML-based defect prediction models using design-level metrics in conjunction with data sampling techniques are effective in finding software defects. The study shows that design-level attributes have a strong correlation with the probability of defects and the SMOTE data sampling approach improves the performance of prediction models. When design-level metrics are applied, the Adaboost ensemble method provides the best performance to detect the minority class samples [

110].

For quality assurance and maturity support of the final products, requirements must be verified and validated at different testing levels. To achieve this, requirements are manually labeled to indicate the corresponding testing level. The number of requirements can vary from few hundreds in smaller projects to several thousands in larger projects. Their manual labeling is time consuming and error-prone, thus sometimes incurring an unacceptable high cost. In [

111], the initial results on an automated requirements classification approach proposal are reported. Requirements are automatically classified into two classes, using machine learning approaches: ’Integration Test’ and ’Software Test’. The proposed solution may help the requirements engineers by speeding up the requirements classification and thus reducing the time to market of final products.

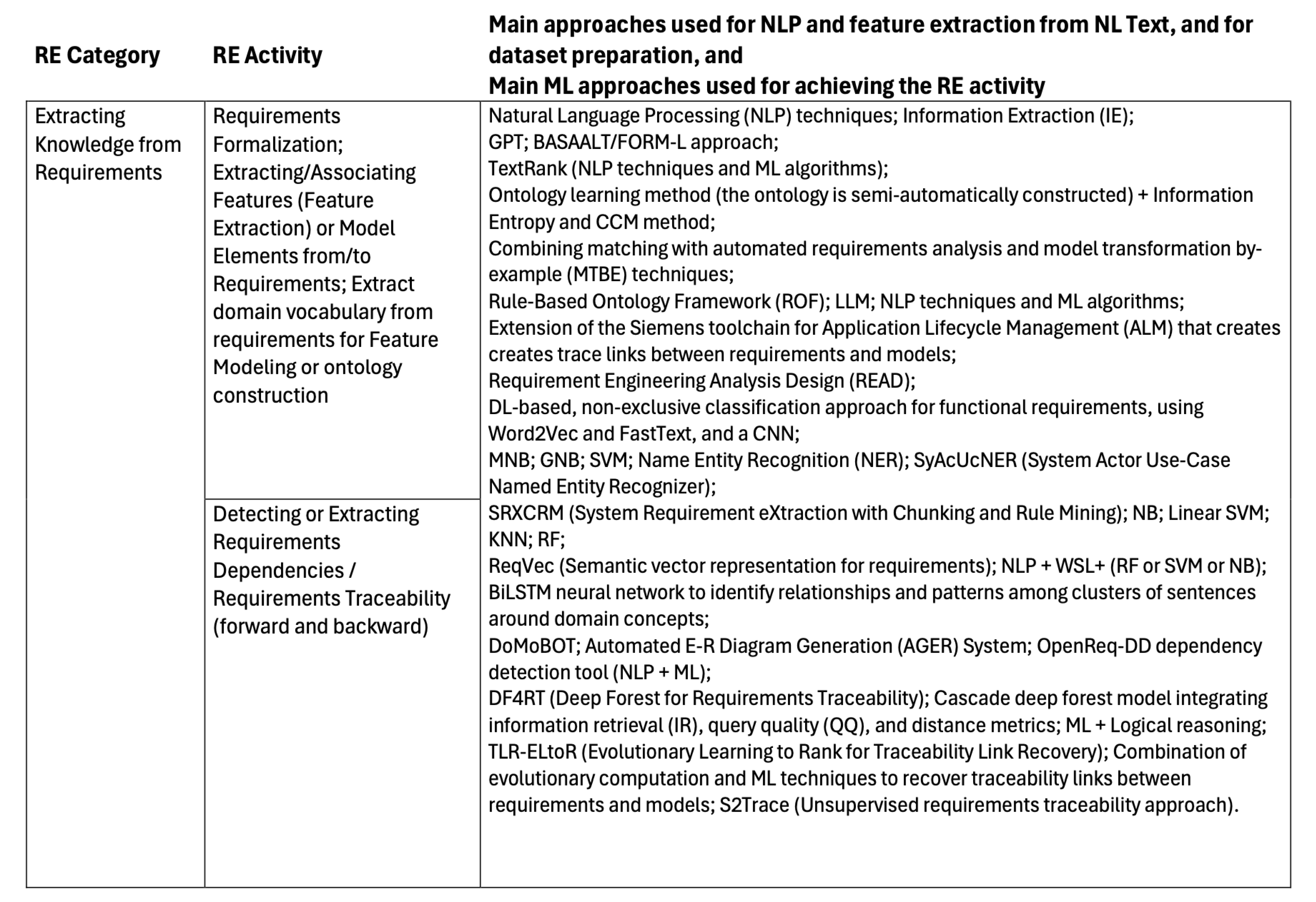

5.2.4. Extracting Knowledge from Requirements

The extraction of knowledge from requirements specifications enables getting semantically rich objects and concepts for building more formal models of such requirements or of the intended system. Several reviewed references target this goal, either for formalizing requirements, generating feature models, domain models or use case models, or to build domain vocabularies or ontologies that may help in further tasks towards designing and building the intended system.

In

Table 5, the main NLP and ML-based approaches for extracting knowledge from requirements are presented. As seen in the table, several techniques are reported in the studied literature, and these are addressed in this section, along with each studied reference.

Natural Language Processing (NLP) techniques have demonstrated their effectiveness in analyzing technical specification documents. One such technique, Information Extraction (IE), enables the automated processing of SRS by transforming unstructured or semi-structured text into structured data. This allows requirements to be converted into formal logic or model elements, enhancing their clarity and usability.

In [

114], the authors introduce an IE method specifically designed for SRS data, analyze the proposed technique on a set of real requirements, and exemplify on how information obtained using their technique can be converted into a formal logic representation.

ChatGPT has also shown the potential in assisting software engineers in extracting model elements from requirements specification. In [

58], ChatGPT is used, among other things, to requirements analysis and domain and design modeling. The study identifies lack of traceability and inconsistencies among produced artifacts as the main drawbacks. This demands human involvement in RE activities, but can serve as a valuable tool in the SDLC, enhancing productivity.

User demand is the key to software development. The domain ontology established by artificial intelligence can be used to describe the relationship between concepts in a specific domain, which can enable users to agree on conceptual understanding with developers [

112]. The study in [

112] uses the ontology learning method to extract the concept, and the ontology is constructed semi-automatically or automatically. Because the traditional weight calculation method ignores the distribution of feature items, the authors introduce the concept of information entropy, and the CCM method is further integrated [

112]. This method allows improving the automation degree of ontology construction, and also make the user requirements of software more accurate and complete.

The BASAALT/FORM-L approach, seen before, can also be used to extract knowledge from textual requirements [

83]. The approach creates semantically precise and simulable models while integrating missing contextual details. These models can then be reviewed by stakeholders to ensure alignment with intended requirements.

In [

81], a machine learning-based approach is proposed to formalize NL requirements for critical embedded systems. Using spaCy’s pre-trained NLP model, the method performs tokenization, PoS tagging, and dependency parsing. A rule-based strategy extracts text chunks, ensuring domain independence. These chunks are reordered into a standardized format, with deviations signaling quality issues. The structured output supports test oracle generation, software implementation, and requirement assessment through similarity and complexity metrics.

In [

113], the authors address how the production of model transformations (MT) can be accelerated by automating transformation synthesis from requirements, examples and metamodels. A synthesis process is introduced, based on metamodel matching, correspondence patterns between metamodels, and completeness and consistency analysis of matches [

113]. The authors also address how to deal with the limitations of metamodel matching by combining matching with automated requirements analysis and model transformation by-example (MTBE) techniques [

113]. In practical examples, a large percentage of required transformation functionality can usually be constructed automatically, thus potentially reducing development effort. The efficiency of synthesized transformations is assessed [

113].

The authors in [

115], elaborate on previous work and propose a Rule-Based Ontology Framework (ROF) for Auto-Generating Requirements Specification. ROF covers the processes of requirements elicitation and of requirements documentation. The output of the elicitation process is a list of final requirements that are stored in an ontology structure, called Requirements Ontology (RO) [

115]. From the RO, the documentation process automatically generates two outputs: process model, in the Business Process Model and Notation (BPMN) standard; and, SRS documents, in the IEEE standard [

115]. The authors analyze the feasibility of implementing ROF in Information System (IS) projects through a case study on lecturer workload calculation at an Indonesian university. Using qualitative and quantitative methods, they assess each output and conclude that ROF effectively minimizes effort in generating requirements specifications [

115].

Given the rise of LLMs, the authors in [

116] investigate their potential for extracting domain models from agile product backlogs. They compare LLMs against (i) a state-of-practice tool and (ii) a specialized NLP approach, using a dataset of 22 products and 1679 user stories. This research marks an initial step toward leveraging LLMs or tailored NLP for automated model extraction from requirements text [

116].

Model-Based Software Engineering (MBSE) offers various modeling formalisms, including domain models, which capture key concepts and relationships in class diagrams, in early design stages. Domain modeling transforms informal NL requirements into concise, analyzable models. However, existing automated approaches face three key challenges: insufficient accuracy for direct use, limited modeler interaction, and a lack of transparency in modeling decisions [

117]. To address this, the authors in [

117] propose an algorithm that enhances bot-modeler interaction by identifying and suggesting alternative configurations. Upon modeler approval, the bot updates the domain model. Evaluations show the bot achieves median F1 scores of 86% for Found Configurations, 91% for Offered Suggestions, and 90% for Updated Models, with a median processing time of 55.5 ms.

In [

118], the authors employ NLP techniques and ML algorithms to automatically extract and rank the requirements terms to support high-level feature modeling. For that, they propose an automatic framework composed of noun phrase identification technique for requirements terms extraction and TextRank combined with semantic similarity for terms ranking. The final ranked terms are organized as a hierarchy, which can be used to help name elements when performing feature modeling [

118]. In the quantitative evaluation, the proposed extraction method performs better than three baseline methods in recall with comparable precision. Their adapted TextRank algorithm can rank more relevant terms at the top positions in terms of average precision compared with most baselines [

118].

Feature models (FM) provide a visual abstraction of the variation points in the analysis of Software Product Lines (SPL), which comprise a family of related software products. FMs can be manually created by domain experts or extracted (semi-)automatically from textual documents such as product descriptions or requirements specifications [

119]. In [

119] a method to quantify and visualize whether the elements in a FM (features and relationships) conform to the information available in a set of specification documents is proposed. Both the correctness (choice of representative elements) and completeness (no missing elements) of the FM are considered.

Requirements traceability helps to ensure that the developed system fulfills all requirements and prevents failures. For safety-critical systems, traceability is mandatory to ensure that the system is implemented correctly. Establishing and maintaining trace links are hard to achieve manually in today’s complex systems [

120]. In [

120], the authors propose a tool for establishing bi-directional traceability links between requirements and model-based designs using Artificial Intelligence (AI). The tool is an extension of the Siemens toolchain for Application Lifecycle Management (ALM), systems engineering, and embedded software design. The proposed tool creates trace links between requirements written in natural language and CapitalTM software, AUTOSAR, SysML, UML, or Arcadia models for system/software design. The authors describe the implemented use-cases of tracing system/SW/HW requirements to system architecture models and provide an overview of the tool architecture.

Retrieving and extracting software information from SRS is crucial for SPL development. While NLP techniques like information retrieval and machine learning have been proposed for optimizing requirements specifications, they remain underutilized due to the complexity of organizational information and subsystem inter-dependencies [

43]. A simple multi-class classification framework is insufficient to address these challenges. To overcome this, the work in [

43] proposes a deep learning-based, non-exclusive classification approach for functional requirements. It utilizes Word2Vec and FastText word embeddings to represent documents and train a convolutional neural network (CNN). The study uses manually categorized enterprise data (AUTOSAR) for training and compares the impact of Word2Vec and FastText embeddings with pre-trained models available online.