Submitted:

29 March 2025

Posted:

31 March 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Evaluating Existing Scoring Systems

a. Symptom Based Triage Systems—Clinical Impression Triage Systems

b. Early Warning Scores (EWS)

c. Specific Disease Scores

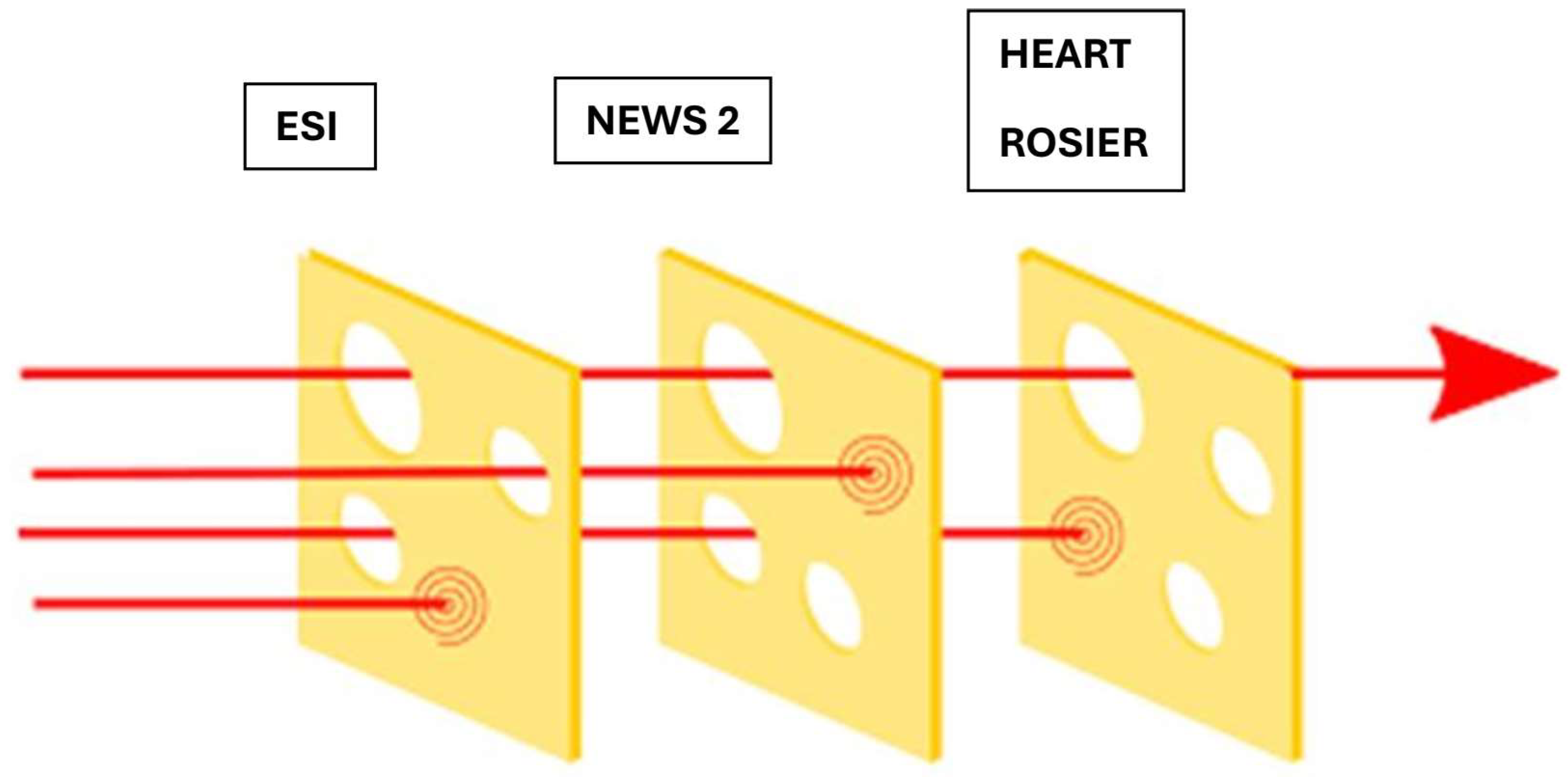

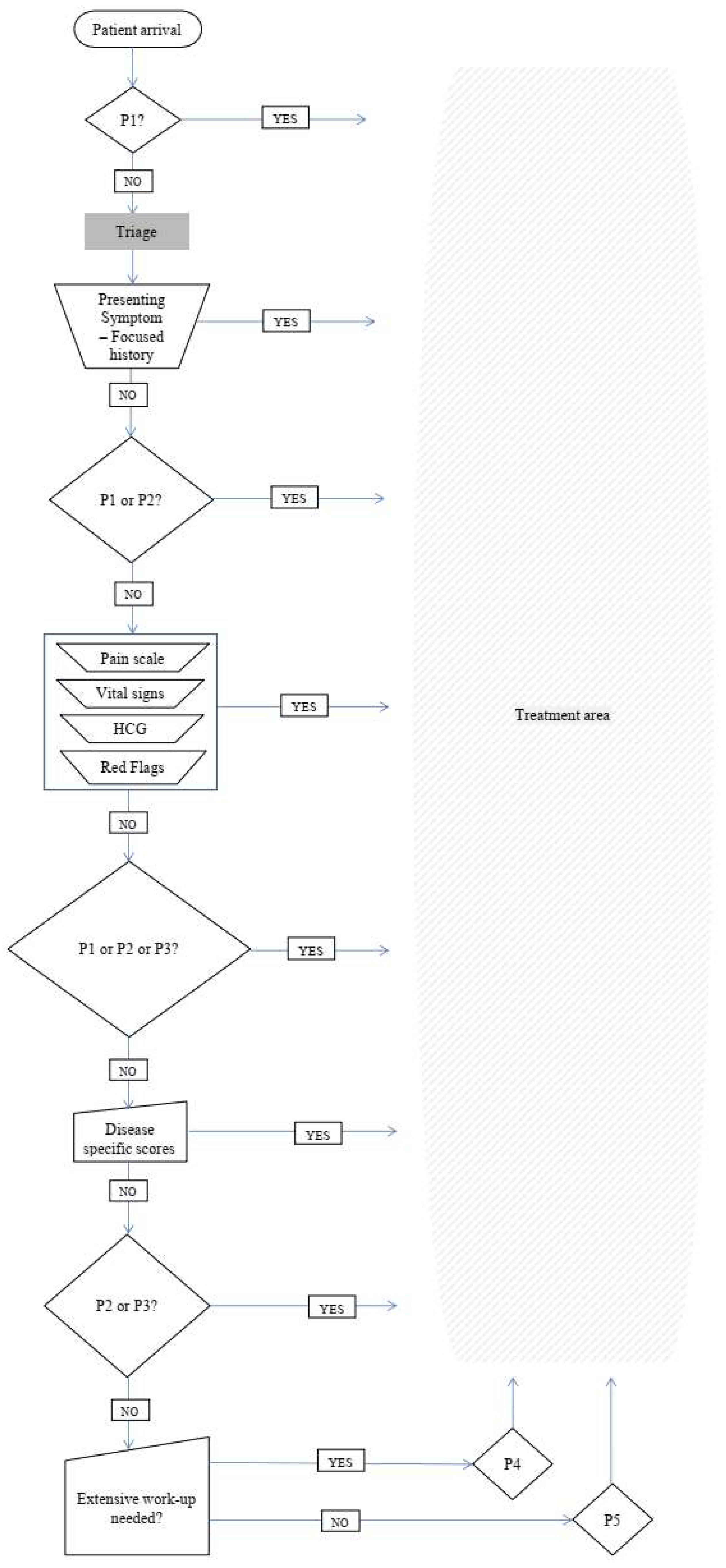

3. Proposing a Multilayer Triage System

-

Seeking Priority 1 patients – Clinical impression

- Use the basic principles of clinical impression triage systems such as ESI

- “Is there immediate risk for life or limb?”

- If the answer is YES the patient is Priority 1

- In the answer is NO proceed to the next step

-

Seeking Priority 2 Patients – Basic History taking and clinical impression

- Use the basic principles of clinical impression triage systems such as ESI

- “Is patient’s condition serious enough or deteriorating so rapidly that there is the potential of threat to life, or organ system failure?”

- “Is the patient in severe pain?”

- “Does the patient have altered mental status?”

- “Are there any “Red Flags”?” CTAS, ATS, MTS

- If the answer is YES to any of the above questions, the Patient is Priority 2

- If the answer is NO proceed to the next step

-

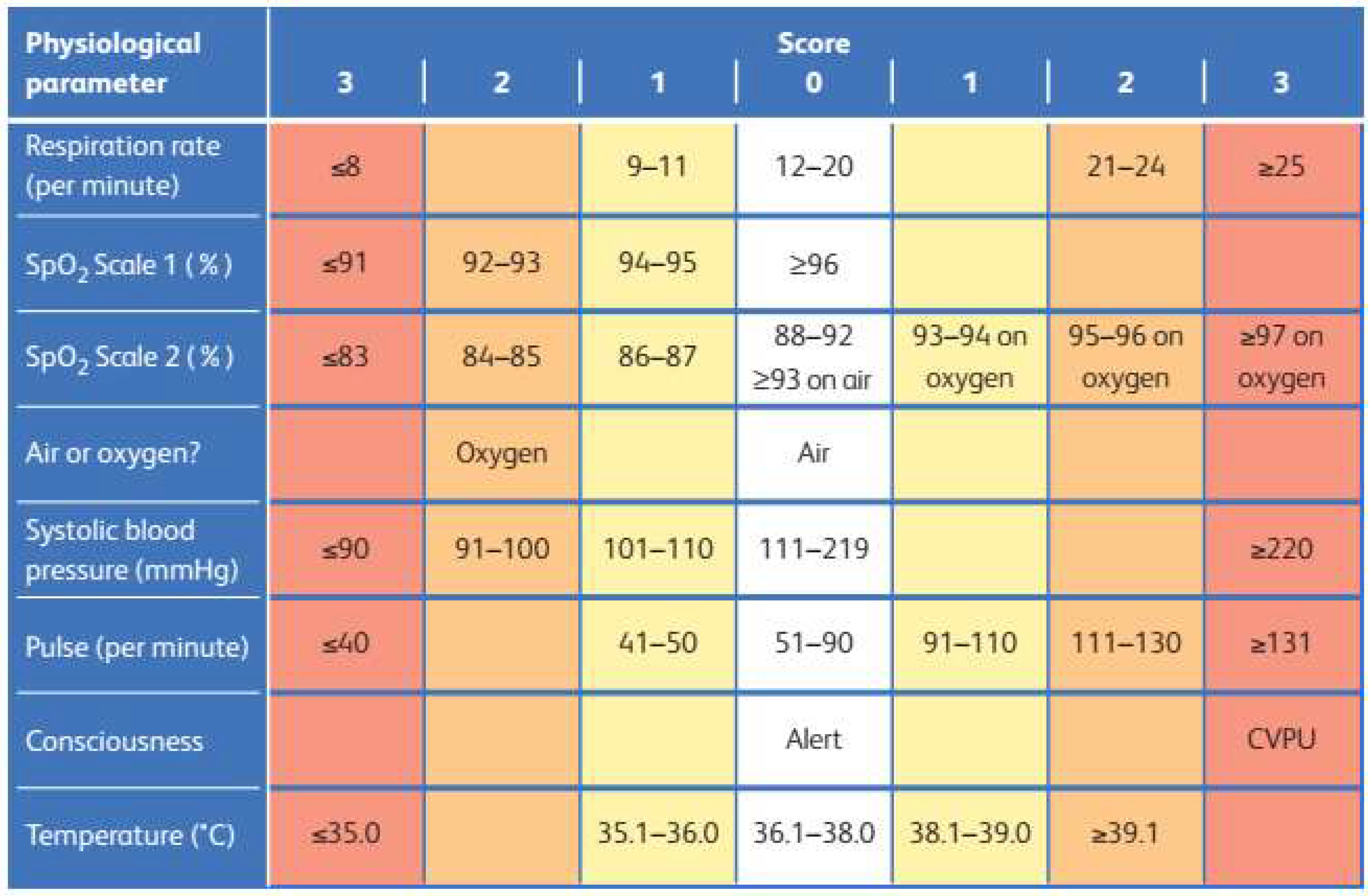

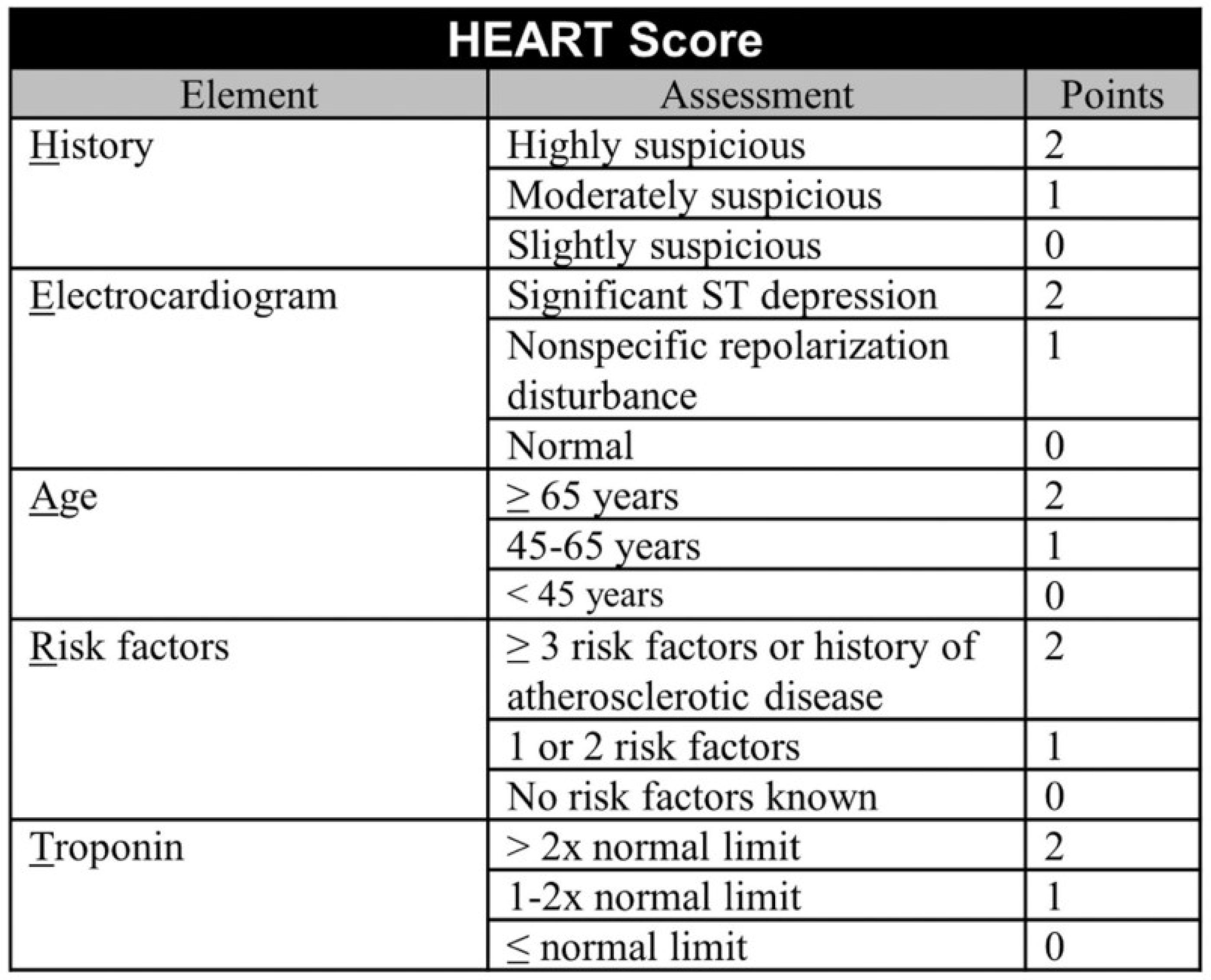

Are you sure the Patient is NOT Priority 1 or 2 ? – Vital signs

- Use NEWS 2 to interpret vital signs

-

Prioritize patient according to the EWS you have chosen

- NEWS2 Score > 7 the patient is priority 2

- NEWS2 Score 5-6 or red score of 3 in any individual parameter, the patient is priority 3

- NEWS2 Score 0-4 Proceed to the next step

-

Could the patient have an atypical presentation of a time-sensitive disease? – Disease specific scores

- Use one of the accredited disease-specific scores depending on the clinical question.

- Prioritize the patient according to the score you have chosen.

-

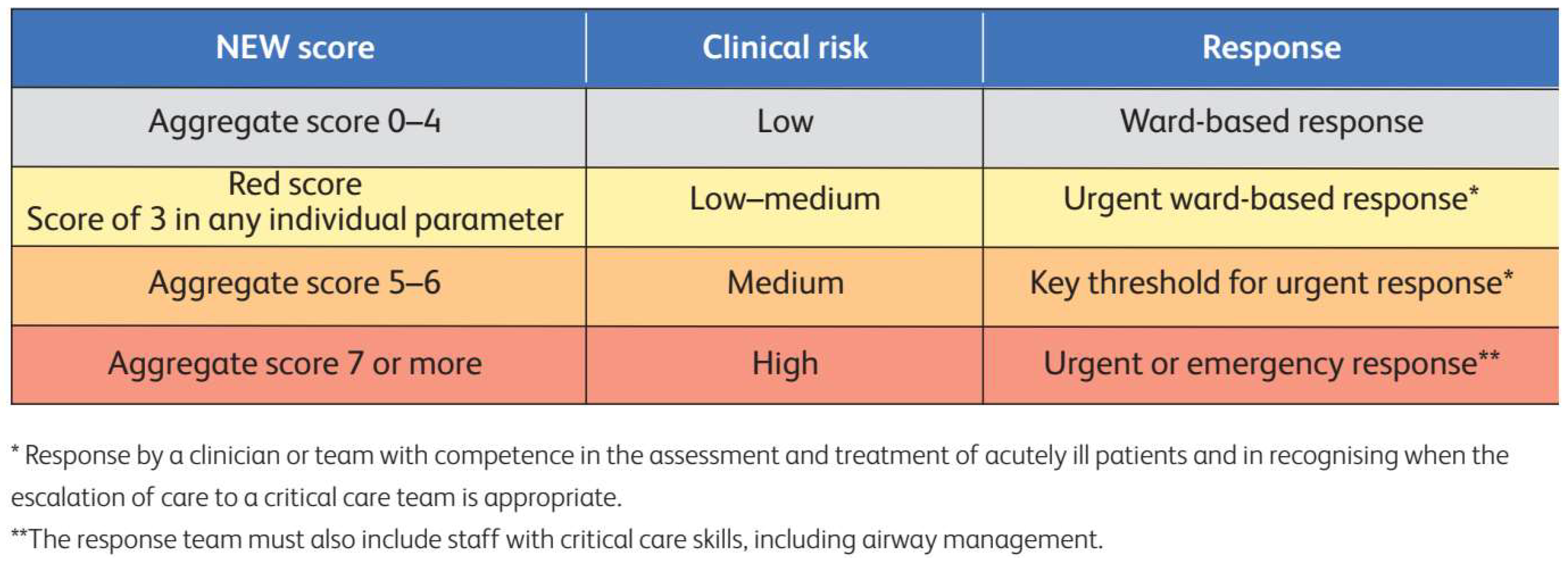

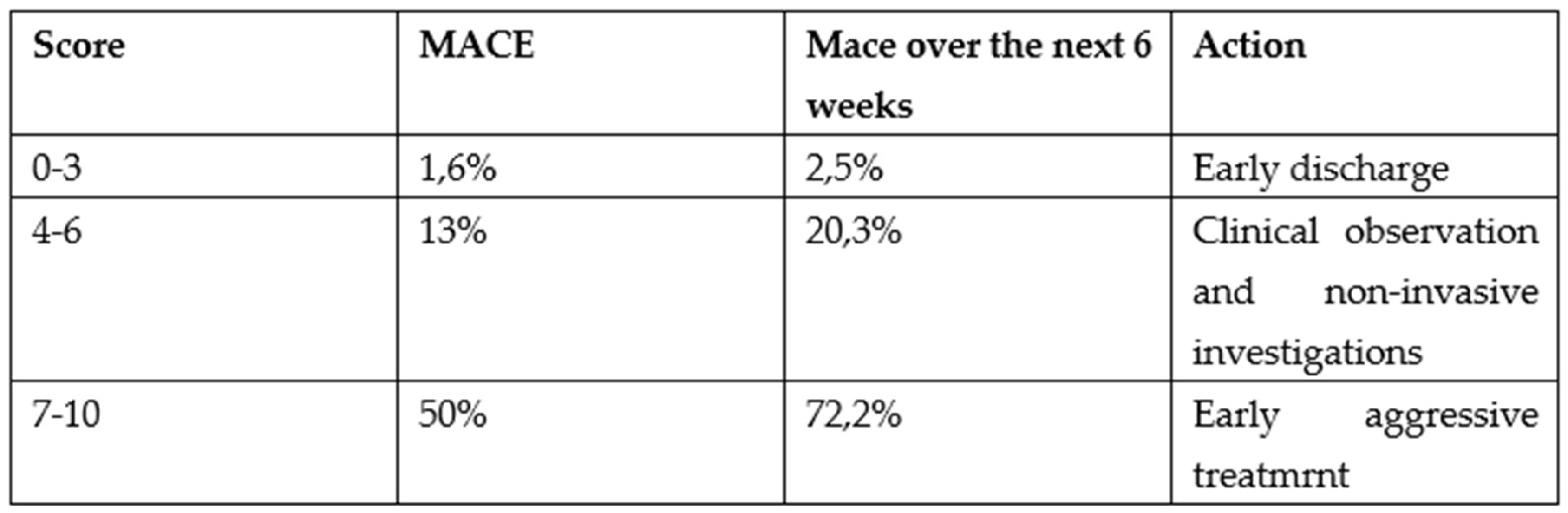

Use the HEART score for a possible ACS

- For a HEART score 7-10 the patient is priority 2

- For a HEART score between 4-6 the patient is priority 3

- For a HEART score 0-3 proceed to the next step

-

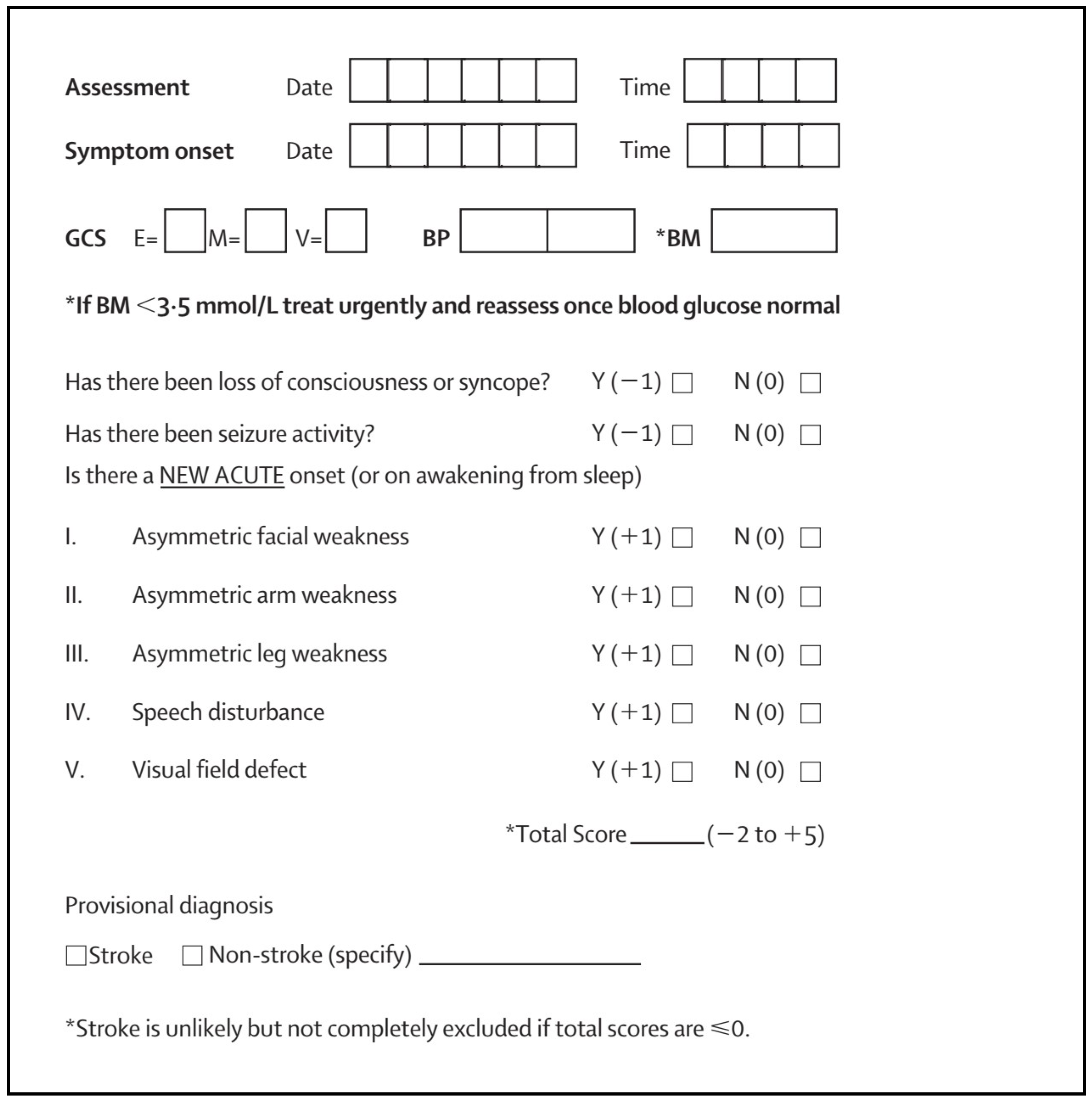

Use Rosier score for a possible stroke

- For Rosier >1 the patient is priority 2

- For Rosier < 0 proceed to the next step

-

Will this patient require extensive work-up? – Focused history taking

- Use the basic principles of clinical impression triage systems such as ESI, CTAS

- “Will the patient, due to his age or comorbidities, require extensive work-up?”

- If the answer is YES the patient is Priority 4

- If the answer is NO the Patient is Priority 5.

4. Results

5. Conclusion

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- FitzGerald G, Jelinek GA, Scott D, Gerdtz MF. Emergency department triage revisited. Emerg Med J. 2010;27:86–92.

- Tam HL, Chung SF, Lou CK. A review of triage accuracy and future direction. BMC Emerg Med. 2018; 20;18(1):58. PMID: 30572841; PMCID: PMC6302512. [CrossRef]

- El-Fellah N., Dritsa A., Dermatis P., Intas G., Papadopoulos G., Kaklamanou E., Tsiftsis D., “Knowledge of Health Care Professionals of the Emergency Department of the Hospital of N. Attica in the Emergency Severity Index Triage System”. Hellenic Journal of Nursing. 2017;56(4)358-365 (Article in Greek).

- Storm-Versloot MN, Ubbink DT, Kappelhof J, Luitse JS. Comparison of an informally structured triage system, the emergency severity index, and the manchester triage system to distinguish patient priority in the emergency department. Acad Emerg Med. 2011 Aug;18(8):822-9. PMID: 21843217. [CrossRef]

- Rashid K, Ullah M, Ahmed ST, Sajid MZ, Hayat MA, Nawaz B, Abbas K. Accuracy of Emergency Room Triage Using Emergency Severity Index (ESI): Independent Predictor of Under and Over Triage. Cureus. 2021 Dec 7;13(12):e20229. PMID: 35004046; PMCID: PMC8730791. [CrossRef]

- Mistry B, Stewart De Ramirez S, Kelen G, Schmitz PSK, Balhara KS, Levin S, Martinez D, Psoter K, Anton X, Hinson JS. Accuracy and Reliability of Emergency Department Triage Using the Emergency Severity Index: An International Multicenter Assessment. Ann Emerg Med. 2018 May;71(5):581-587.e3. Epub 2017 Nov 24. PMID: 29174836. [CrossRef]

- Alonso PS. “Comparative analysis of global triage systems: Competencies of nursing and hospital and prehospital application”. Journal Nursing Valencia 2024,1-31. ISSN 2952-3192.

- Ingielewicz A, Rychlik P, Sieminski M. Drinking from the Holy Grail-Does a Perfect Triage System Exist? And Where to Look for It? J Pers Med. 2024 May 31;14(6):590. PMID: 38929811; PMCID: PMC11204574. [CrossRef]

- Sax DR, Warton EM, Mark DG, Vinson DR, Kene MV, Ballard DW, Vitale TJ, McGaughey KR, Beardsley A, Pines JM, Reed ME; Kaiser Permanente CREST (Clinical Research on Emergency Services & Treatments) Network. Evaluation of the Emergency Severity Index in US Emergency Departments for the Rate of Mistriage. JAMA Netw Open. 2023 Mar 1;6(3):e233404. Erratum in: JAMA Netw Open. 2024 Jun 3;7(6):e2423536. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2024.23536. PMID: 36930151; PMCID: PMC10024207. [CrossRef]

- Kuriyama A, Urushidani S, Nakayama T. Five-level emergency triage systems: variation in assessment of validity. Emerg Med J. 2017 Nov;34(11):703-710. Epub 2017 Jul 27. PMID: 28751363. [CrossRef]

- Gatsouli M., Gerakari S., Ivkovitz Z., Intas G., Kalogridaki M,. Karametos I., Lymperopoulou D., Pantazopoulos I., Paylidou E., Stavroulakis S., Notas G., Editors Tsiftsis D., Notas G., Peitsidou E., Dermatis P., Kitsakos A., Bampalis D., Tsikrika M. “Proposal of the Hellenic Society for Emergency Medicine for the pilot implementation of a National triage system in sites providing emergency care services” (Article in Greek) available on-line at https://www.hesem.gr/%cf%80%cf%81%cf%8c%cf%84%ce%b1%cf%83%ce%b7-%ce%b5%ce%bb%ce%bb%ce%b7%ce%bd%ce%b9%ce%ba%ce%ae%cf%82-%ce%b5%cf%84%ce%b1%ce%b9%cf%81%ce%b5%ce%af%ce%b1%cf%82-%ce%b5%cf%80%ce%b5%ce%af%ce%b3%ce%bf%cf%85/.

- Christ M, Grossmann F, Winter D, Bingisser R, Platz E. Modern triage in the emergency department. Dtsch Arztebl Int. 2010 Dec;107(50):892-8. Epub 2010 Dec 17. PMID: 21246025; PMCID: PMC3021905. [CrossRef]

- Zachariasse JM, van der Hagen V, Seiger N, Mackway-Jones K, van Veen M, Moll HA. Performance of triage systems in emergency care: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ Open. 2019 May 28;9(5):e026471. PMID: 31142524; PMCID: PMC6549628. [CrossRef]

- Suamchaiyaphum K, Jones AR, Polancich S. The accuracy of triage classification using Emergency Severity Index. Int Emerg Nurs. 2024 Dec;77:101537. Epub 2024 Nov 10. PMID: 39527884. [CrossRef]

- Peta D, Day A, Lugari WS, Gorman V, Ahayalimudin N, Pajo VMT. Triage: A Global Perspective. J Emerg Nurs. 2023 Nov;49(6):814-825. PMID: 37925222. [CrossRef]

- Goldhill DR, McNarry AF. Physiological abnormalities in early warning scores are related to mortality in adult inpatients. British Journal of Anaesthesia. 2004;92(6):882-4.

- Ridley S. The recognition and early management of critical illness. Annals of the Royal College of Surgeons of England. 2005;87(5):315-22.

- Spencer W, Smith J, Date P, de Tonnerre E, Taylor DM. Determination of the best early warning scores to predict clinical outcomes of patients in the emergency department. Emerg Med J. 2019 Dec;36(12):716-721. Epub 2019 Jul 31. PMID: 31366627. [CrossRef]

- Downey CL, Tahir W, Randell R, Brown JM, Jayne DG. Strengths and limitations of early warning scores: A systematic review and narrative synthesis. Int J Nurs Stud. 2017 Nov;76:106-119. Epub 2017 Sep 13. PMID: 28950188. [CrossRef]

- Schinkel M, Bergsma L, Veldhuis LI, Ridderikhof ML, Holleman F. Comparing complaint-based triage scales and early warning scores for emergency department triage. Emerg Med J. 2022 Sep;39(9):691-696. Epub 2022 Apr 13. PMID: 35418407; PMCID: PMC9411919. [CrossRef]

- Kramer AA, Sebat F, Lissauer M. A review of early warning systems for prompt detection of patients at risk for clinical decline. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2019 Jul;87(1S Suppl 1):S67-S73. PMID: 31246909. [CrossRef]

- Williams B. The National Early Warning Score: from concept to NHS implementation. Clin Med (Lond). 2022 Nov;22(6):499-505. PMID: 36427887; PMCID: PMC9761416. [CrossRef]

- Royal College of Physicians. National Early Warning Score (NEWS) 2: Standardising the assessment of acute-illness severity in the NHS. Updated report of a working party. London: RCP, 2017.

- Smith GB, Prytherch DR, Meredith P, Schmidt PE, Featherstone PI. The ability of the National Early Warning Score (NEWS) to discriminate patients at risk of early cardiac arrest, unanticipated intensive care unit admission, and death. Resuscitation. 2013 Apr;84(4):465-70. Epub 2013 Jan 4. PMID: 23295778. [CrossRef]

- Khan IA, Karim HMR, Panda CK, Ahmed G, Nayak S. Atypical Presentations of Myocardial Infarction: A Systematic Review of Case Reports. Cureus. 2023 Feb 26;15(2):e35492. PMID: 36999116; PMCID: PMC10048062. [CrossRef]

- Vilela P. Acute stroke differential diagnosis: Stroke mimics. Eur J Radiol. 2017 Nov;96:133-144. Epub 2017 May 5. PMID: 28551302. [CrossRef]

- Pohl M, Hesszenberger D, Kapus K, Meszaros J, Feher A, Varadi I, Pusch G, Fejes E, Tibold A, Feher G. Ischemic stroke mimics: A comprehensive review. J Clin Neurosci. 2021 Nov;93:174-182. Epub 2021 Sep 20. PMID: 34656244. [CrossRef]

- Nishi FA, de Oliveira Motta Maia F, de Souza Santos I, de Almeida Lopes Monteiro da Cruz D. Assessing sensitivity and specificity of the Manchester Triage System in the evaluation of acute coronary syndrome in adult patients in emergency care: a systematic review. JBI Database System Rev Implement Rep. 2017 Jun;15(6):1747-1761. PMID: 28628525. [CrossRef]

- Ashburn NP, O’Neill JC, Stopyra JP, Mahler SA. Scoring systems for the triage and assessment of short-term cardiovascular risk in patients with acute chest pain. Rev Cardiovasc Med. 2021 Dec 22;22(4):1393-1403. PMID: 34957779; PMCID: PMC9038214. [CrossRef]

- Ke J, Chen Y, Wang X, Wu Z, Chen F. Indirect comparison of TIMI, HEART and GRACE for predicting major cardiovascular events in patients admitted to the emergency department with acute chest pain: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ Open. 2021 Aug 18;11(8):e048356. PMID: 34408048; PMCID: PMC8375746. [CrossRef]

- Zhelev Z, Walker G, Henschke N, Fridhandler J, Yip S. Prehospital stroke scales as screening tools for early identification of stroke and transient ischemic attack. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2019 Apr 9;4(4):CD011427. PMID: 30964558; PMCID: PMC6455894. [CrossRef]

- Chehregani Rad I, Azimi A. Recognition of Stroke in the Emergency Room (ROSIER) Scale in Identifying Strokes and Transient Ischemic Attacks (TIAs); a Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Arch Acad Emerg Med. 2023 Oct 5;11(1):e67. PMID: 37840869; PMCID: PMC10568950. [CrossRef]

- Tsiftsis D., El-Fellah N., Dermatis P., “Systems and algorithms of Hospital Triage and patient acuity assessment in the Emergency department” In Book “Intensive and Emergency Medicine: Scales, Algorithms, Protocols, Limits, criteria and indicators”, 22nd Edition, Ed. George Baltopoulos. 301-9, Athens, Ekdosis Epistimon, 2019. ISBN: 978-618-83535-5-8. (Chapter in Greek).

- Reason, J. (1997). Managing the Risks of Organizational Accidents (1st ed.). Routledge. [CrossRef]

- BenAveling - File:Swiss cheese model.svg, CC BY-SA 4.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=133912327.

- Aung SSM, Roongsritong C. A Closer Look at the HEART Score. Cardiol Res. 2022 Oct;13(5):255-263. Epub 2022 Oct 25. PMID: 36405228; PMCID: PMC9635776. [CrossRef]

- Nor AM, Davis J, Sen B, Shipsey D, Louw SJ, Dyker AG, Davis M, Ford GA. The Recognition of Stroke in the Emergency Room (ROSIER) scale: development and validation of a stroke recognition instrument. Lancet Neurol. 2005 Nov;4(11):727-34. PMID: 16239179. [CrossRef]

- Aung SSM, Roongsritong C. A Closer Look at the HEART Score. Cardiol Res. 2022 Oct;13(5):255-263. Epub 2022 Oct 25. PMID: 36405228; PMCID: PMC9635776. [CrossRef]

| Parameter | ATS | MTS | CTAS | ESI |

| Time to initial assessment | 10 min | ns | ns | ns |

| Time to contact with doctor with right to treat | Immediate / 10 / 30 /60 / 120 min | Immediate / 10 / 60 /120 / 240 min | Immediate / 15 / 30 /60 / 120 min | Immediate / 10 min /n. s |

| Re-triage | ns | As required | I:continuously; II: 15 min; III: 30 min; IV: 60 min; V: 120 min |

As required |

| List of diagnoses or key symptoms |

YES | 52 Key Symptoms | YES | No |

| Training material | YES | YES | YES | YES |

| Patient Priority | Clinical condition | Tools used to identify |

|---|---|---|

| Priority 1 | Immediate risk for life or limb | ESI |

| Priority 2 | Serious enough or deteriorating so rapidly | ESI and/or Red Flags and/or NEWS 2>7 and/or HEART score >7 and/or Rosier >1 |

| Priority 3 | Not serious enough, but could have atypical or early presentation of a serious condition | NEWS 2=5-6 and/or HEART score =4-6 |

| Priority 4 | No serious underlying condition, but will require extensive work up | ESI and NEWS 2=0-4 and HEART =0-3 and Rosier <0 |

| Priority 5 | Acute but non-urgent or chronic problem without deterioration. Need minimum investigation | ESI and NEWS 2=0-4 and HEART =0-3 and Rosier <0 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).