1. Introduction

Climate change is a significant concern for African countries, and the continent is projected to be among the most affected by climate change impacts, such as widespread drought, flooding, and catastrophic storms [

1,

2], particularly among the poorest countries. Specifically in the Sahel region, agricultural productivity, primarily reliant on rain-fed systems, is suffering, resulting in crop failures and livestock losses. In this view, food security and malnutrition rates increase, particularly among vulnerable people [

3].

In Africa, many young people no longer attend school regularly [

4]. Consequently, when Cyclone Freddy struck Southern Africa in March 2023, almost 5% of children in Malawi faced school closures [

3]. Additionally, 42% of primary schools were closed in 2015 due to the drought, resulting in approximately 130,000 children missing school due to severe weather events in Malawi [

3]. Almost 57% of schools in Zimbabwe reported destruction of certain infrastructure due to Cyclone Idai, which struck the country in 2019 [

3]. Extreme weather events, such as flooding and wind, have been leading to the destruction of bridges, highways, and educational institutions. During the 2016/2017 agricultural season, substantial rainfall occurred nationwide, destroying around 18.0% of the country's schools and disrupting the education of around 500,000 students in Zimbabwe [

5]. In 2014, weather-related diseases, including malaria and diarrhoea, resulted in the deaths of 4.5% of all primary school children and 1.4% of secondary school dropouts. In 2015, 3.8% of secondary school children and 1.3% of secondary school students dropped out of school due to illness. Child marriage serves as a coping strategy in response to climate catastrophes, as the bride's price helps the family provide sustenance, clothing, and education, thereby enhancing food security. Consequently, in 2015 in Zimbabwe, 20.5% of girls who discontinued their education due to marriage and 14.6% who did so due to pregnancy encountered this situation [

5].

Moreover, strong winds have destroyed some of the Nigerian school buildings, and the mangroves protecting the coastline have been significantly depleted due to human activities [

6]. Recent floods in Nigeria have caused extensive damage to dwellings, resulting in a significant displacement of individuals seeking improved living conditions. Schools and educational materials were destroyed, negatively impacting children's learning experiences. The destruction of homes due to flooding has intensified the insecurity faced by secondary school students in Nigeria, undermining their safety and education [

6]. Furthermore, like the rest of the Sahel, Mali has faced severe climate changes over the past three decades, preventing its varied ecosystems from returning to their old equilibrium. Climate austerity has been gradually implemented, with disastrous consequences: recurrent rainfall shortfalls have led to famine, exodus, and death for humans and animals, and the reactivation of dunes in Mali's northern Sahel [

7]. In 2024, the United Nations Children's Fund (UNICEF) reported that Mali, Niger, and Senegal are part of eight countries throughout the world where children are subjected to temperatures above 35 degrees Celsius for more than half the year [

8]. Moreover, since 2019, the education authorities of Mali have adjusted the working hours in basic education from March to June to accommodate heat waves, resulting in a loss of 1 hour and 30 minutes from working hours [

9,

10].

On the other hand, from July to September 2024, the Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (OCHA) reported that Mali experienced exceptional rainfall, the heaviest since 1967. Consequently, torrential rains and overflowing rivers have caused significant damage to property and human life in Mali. Many schools have been designated as emergency shelters for victims in all nine regions and the Bamako district. Faced with this extraordinary scenario, on September 30th, the government postponed the start of the school year for primary, lower secondary, and secondary schools, allowing schools to continue their activities under acceptable conditions. The beginning of the 2024-2025 school year, initially scheduled for October 1st, has been postponed to Monday, November 4th. This decision aims to preserve the safety of students and educational staff and allow the authorities to better manage the consequences of the ongoing crises [

11,

12]. Given the above context, significant efforts are required to empower schoolchildren's capacity to mitigate and adapt to climate change in Mali.

The experts who comprise the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) have created global awareness of addressing climate change mitigation and adaptation through educational programmes [

13]. Other scholars [

2,

3,

4,

5,

6,

7,

8,

9,

10,

11,

12,

13,

14,

15] have written about this issue globally. [

14] suggests that education provides the necessary knowledge to achieve “successful climate change mitigation and adaptation.” Climate change education aims to develop and implement educational responses based on informed assessments that are effective in the context of climate-related disasters. Therefore, addressing climate change-related curricula in basic education could effectively restrict the cycle of gaps in adulthood [

16].

Although, in the face of environmental and climate issues, education has long been perceived as the main lever for sustainable development insofar as it makes it possible to better inculcate in citizens the foundations of good citizenship and to build in them the values of their nation while taking into account the emotional, artistic, cultural, critical and practical. However, significant efforts have been made at primary and lower secondary through the Plan for the Generalization of Environmental Education in Mali (PAGEEM) since 1990. Moreover, in 2020, in the context of revitalising PAGEEM through the project to strengthen the resilience of the education system as an alternative for preventing and fighting climate change, the Ministry of Education and its partners undertook a socioeconomic, cultural, and political analysis. These results, the integration of climate change education into the national curriculum [

17,

18,

19]. Consequently, the implementation of this project is impacted by the low technical, financial, and logistical capacity, as well as the lack of training. In addition, the project recommended increasing the duration of the training to address several limited practical cases, making documents on climate change topics available to schools, and continuing to strengthen the capacities of teachers and pupils on environmental and protection themes. This research extends to the point that pupils and teachers of Koulikoro understand, teach, and learn about climate change, which becomes the interest of the study. The study aims to examine the perceptions, knowledge, and motivations of fifth- and sixth-grade pupils regarding climate change before and after climate change education. It also seeks to explore the views of fifth- and sixth-grade pupils on the status of climate change in the curriculum before and after a climate change education initiative. The study is among the first research to examine the integrated climate change education curriculum in the nation's primary education system. Although Malian citizens need to be aware of climate change mitigation and adaptation strategies. The study findings can help policymakers and educational stakeholders inform further policy development in response to climate change.

4. Discussion

This research evaluated the perceptions, knowledge, and motivations of fifth- and sixth-grade pupils regarding climate change (CC) before and after a climate change education (CCE) session. Initially, pupils showed low perceptions and limited knowledge of CC. They were less motivated and indicated that CC was missing from their syllabus. However, they reported the importance of learning about it. The post-test findings explicitly indicate that participants reported enormous improvement in their concerns, attitudes and awareness of CC. They significantly increased their knowledge of climate change causes, impacts, mitigation, and adaptation, as well as their motivation to act on climate change and desire to learn more about it. Finally, pupils agreed that they had learned CC from their syllabus.

The pre-test data indicated that 86.0% of the pupils' definitions of CC predominantly reflect alternative conceptions. CC is sometimes characterised as transitioning from the wet to the arid seasons. Some also regarded it as a transition from the cold season to the summer season. These findings align with the research conducted by [

37], which indicated that Finnish and Tanzanian pupils were unable to articulate the concept of CC. The Finnish students mainly mentioned that “it will be warmer” or “some things are changing.” Tanzanian students emphasised that CC is “weather changes recorded for a long time” or changes in the “atmosphere and weather.” The study was conducted in Nigeria [

38] reveals that 37.3% of secondary pupils are unaware of CC, 53.2% possess limited knowledge, and 9.5% have a substantial understanding of the subject. The post-test data revealed that most pupils believe CC raises the average temperatures over long periods due to human activity and natural processes that significantly impact the environment, people, and their livelihoods. The research findings are in accordance with a study conducted in Tonga [

36], the post-intervention data indicate that students resolved their misunderstanding of climate and weather and gained a more scientific understanding of climate change (CC). According to the data, students indicated CC impacts include more cyclones and droughts, rising sea levels, migration, and health problems.

Pupils reported low perceptions of CC in the first assessment. A few pupil (8.8%) believed CC was happening and stated it was a new societal and environmental problem for Mali. Other studies are consistent with these findings, which found that middle school students revealed low concerns about CC in North Carolina [

39,

40]; in Nigeria, [

41] report that 87% of respondents were unsure of their feelings, felt helpless to address CC, or did not believe it was occurring. Similar to findings shown in Mozambique, where around 90.0% of the students did not believe that CC is happening, and 50% of the remaining percentage stated their disbelief [

42]. However, the post-test showed that 100.0% of pupils believe CC is happening. Most of them highlight that CC is a societal problem for Mali. Moreover, 89.3% of respondents are hopeful that there are actions we can implement to lessen the effects of CC. The research findings are comparable to research carried out in other countries, in Austria [

43] assessed the responses to global warming among last year's primary students, supporting this study's findings, reported that 75.0% of primary students believed that global warming was currently happening, and 66.0% worried about it; [

44] majority of Algerian students were either very (42.6%) or moderately (40%) concerned about CC and, in Ghana, [

45] most undergraduate students believe CC is real and mostly human-caused, and they raised concerns about it.

Regarding attitudes toward CC, pupils often lack positive responses in recognising it before they experience it firsthand and are unwilling to ask questions about it, with 93.0% of respondents expressing neutrality. These findings are comparable to the earlier study in Finland [

33], which reported that a lack of concern for young people can reduce environmental behaviour by denying environmental problems. Although their findings show that some students are aware of the causes and effects of CC, their attitudes and ability to influence others' actions are pessimistic and doubtful. On the other hand, the post-test data indicated that pupils strongly agreed (99.12%) that they would act to prevent CC before experiencing its impacts. These findings aligned with those [

46] who studied the attitudes of ninth-grade Finnish students toward CC consequences. The data indicate that most students perceive CC as a risk; 55.0% of respondents expressed concern about its consequences.

Pupils revealed low awareness of CC from the pre-test. They did not pay attention to CC news on television, radio, social media, or in the newspaper; most participants (90.0%) remained neutral. These aligned with worldwide research [

47,

48,

49] shows that 40% of people have never heard of CC. The findings of this research are featured in other countries [

50] 61.0% of Palembang City students did not believe that CC information from social media was accurate and [

41] 28.0% of Nigeria's students and civil servants were unaware of the concept of CC. Data post instruction revealed that 97.4% of pupils agreed that the government and everyone in Mali should help reduce CC. They also indicate that they pay attention to CC news on television, radio, social media, and newspapers. Comparatively, these findings are higher than those from the national study conducted by [

51] which found that six out of ten Malians (64.0%) are aware of CC. Our findings are in line with other countries [

52] who claimed that 90.0% of Malaysian students believed everyone is responsible for preserving the environment; [

41] 58% of Nigerian students were aware of CC.

From the pre-test, pupil participants (93.9%) reported misunderstandings about what activities could cause CC, such as burning fossil fuels, bushfires, cutting down trees, and livestock production, as well as damaging the ozone layer and cooling systems. These findings are comparable to those [

51] who reported that their national survey indicated that 47.0% of Malians believe CC is caused by human activities, compared to 38.0% who attribute it to natural processes. This is consistent with studies conducted in other countries [

53] claiming that Indonesian students' knowledge of global warming is very low; [

48] showing that 43% of students in America do not realise that human activities are the primary cause of global warming. However, evaluation after education shows that 97.4% of pupils agreed that human action mainly causes CC, including burning fossil fuels such as oil, coal and natural gas, cutting down trees, rice, cotton, and maize production and cooling systems; they also natural processes such as water vapour, and bush or forest fires. This result is higher than the one obtained from the national survey [

51], which found that 47% of Malians reported that human activities contribute to climate change. Our findings from the post-test align with those of [

37] who discussed primary school students' knowledge of CC in Finland and Tanzania. The findings revealed varied views of students about the causes of CC. Accordingly, Finnish students identified carbon dioxide emissions from fossil fuel combustion, as well as from the frequent use of cars, aircraft, and boats, the clothing industry, water pollution, and sea plastic, as contributing to climate change (CC). Conversely, Tanzanian students emphasised both human activities and natural processes as the causes of CC. Therefore, they indicated that CC is caused by charcoal production from wood, tree harvesting and cutting, air and water pollution, tobacco smoking, weather changes, and certain electrical charges in the clouds.

Most pupils (93.9%) are unaware that CC exacerbates floods and droughts, forces people to migrate from their land, and impacts food production, health, and financial issues for people in Mali. The same respondents are unaware of the impacts of CC on water, crop, and livestock production failures, pollution, rising temperatures, and forest disappearance. This is much better than the findings in the United States [

54], in which none of the students described the impacts of global warming on crops and livestock; in Nigeria [

41], only 0.9% of students and civil servants associated CC impacts with damage to public services. At the same time, no one linked them to the destruction of private businesses and properties or the intrusion of salt into drinking water supplies. According to the post-assessment, 97.4% of pupils agreed that CC exacerbates floods and droughts. They also indicate that it significantly impacts the health and finances of families, as well as food production, water resources, and supply chains. These findings are consistent with a national study conducted by [

51] which found that 74.0% of Malians are aware of CC and recognise its impacts, such as drought, floods, and extreme heat. Our results mirrored those of [

50], who reported that 68.4% of students knew CC increases the likelihood of forest fires, a clean water crisis, the severity of overflowing rivers, storm intensity, and even big floods yearly in many regions worldwide. Similarly, studies on overseas students in Austria and Denmark found that 68.0% of students considered CC a significant issue for the survival of the next generation of human beings [

55]. At the same time, according to [

56], a large percentage of students believe that CC affects both communicable and non-communicable diseases, as noted in their study on the perceptions of nursing students in the Philippines. The students mainly indicate the impacts of CC, such as a rise in mortality rates and diseases (human and animal) due to droughts and flooding, scarcity of food and water, unusual weather patterns, animal deaths, wildfires, diseases in humans, hurricanes, and severe heatwaves.

Findings show that most of the pupils (96.5%) do not know that biking or walking instead of using cars could reduce CC; also, they mostly (96.5%) remained neutral about producing energy from water, solar, wind, biomass, solar ovens, improved stoves, and geothermal rather than oil, coal, charcoal, and natural gas. Pupil participants report unknown, with overall (97.4%) remaining neutral on CC adaptation techniques such as intercropping, half-moon, half-moon, stone barriers, windbreak, Live hedges and windbreak, zai and dune fixation techniques, construction of septic tanks for schools and households, raising awareness of parents and community capacity building, organise an exhibition for parents and community members, write opinion pieces on CC for the school newspaper. These findings mirrored those reported by [

22], who, based on the pre-test, demonstrated that students presently conflate CC mitigation techniques with unrelated environmental issues to a lesser extent than in prior surveys. Students exhibited a limited comprehension of adaptive strategies for CC. Moreover, findings from the post-intervention indicate that most pupils strongly believe that biking or walking mitigates CC, rather than using cars. All respondents (100.0%) agree that adopting renewable energy sources, such as wind, solar, biomass, water, and geothermal, mitigates climate change (CC) more effectively than non-renewable sources, including oil, natural gas, and coal. They strongly believe that solar ovens and improved stoves for cooking, as well as measures such as prohibiting bushfires, promoting agroforestry, reducing pesticide production, managing waste and wildlife, and planting trees, mitigate climate change. Regarding adaptation, most pupils (96.5%) understood climate-smart agriculture techniques, including crop rotation, intercropping, zai, and the half-moon method. Some respondents agreed that stone barriers, live hedges and windbreaks, septic tanks, and dune fixation help people adapt to climate change (CC). The respondents agreed that awareness, exhibition and writing opinion pieces on CC adapt to its impacts. These findings aligned with those from the post-test [

22] indicating that pupils demonstrated an enhanced understanding of the climate system and knowledge of mitigation and adaptation strategies. A similar result was found by [

50], revealed that 69.5% of junior high school students agree that using products that can be recycled and reused is one strategy to mitigate the consequences of global warming; [

37] found that Finnish primary students indicate mitigation strategies for CC, including sorting waste, picking up rubbish, throwing away chewing gum properly, using textile shopping bags, reusing clothes, using electric bicycles and cars, riding bicycles, walking, and using public transport instead of mopeds and flying; their study further stated that Tanzanian students claimed the power of education to mitigate and actively adapt to CC. According to the findings, pupils indicated that the best way to mitigate and adapt to CC could be to educate friends, parents, and families about the benefits of the environment, such as teaching children about planting trees and stopping the cutting down of trees.

Pupils indicate low motivation to take action against climate change (CC). They remained neutral (93.9%) regarding planting trees, walking or biking more, using less electricity in their homes, and helping people who have lost their land and homes due to climate change. They remained less motivated to strengthen parents’ and communities’ resilience to protect their lives and livelihoods against climate change (CC) and establish an early warning system, and only 4.4% agreed with the motivations to act on CC. These findings are lower than those of the study by [

50] in Palembang claimed that 47.4% of students are ready and believe their actions can help solve environmental concerns. The post-test data indicate that 100.0% of pupils either strongly agreed or agreed that they would be prepared to solve the problems of climate change (CC) by planting trees, using less electricity in their homes, and walking or biking more. They also revealed that they will be ready to help homeless people due to CC and establish early warning systems for communities and parents. Our findings are consistent with studies [

53] that indicate senior high school students are willing to save electricity and are willing to ride bicycles or buses instead of motorcycles to reduce their environmental contribution to greenhouse gases.

In the pre-test, pupils mostly (90.5%) remained neutral when asked if they had CC-related issues in their subjects, such as physics, chemistry, natural science, civic and moral education, and French; however, 8.8% agreed that CC was present in the curriculum. These findings suggest a lack of inclusion of CC in the curriculum or the inability of teachers to effectively teach CC-related topics in the syllabi, thereby preventing pupils from becoming familiar with them. These findings align with [

37] show that the Tanzanian Science and Technology Syllabus for Primary School Education does not include CC but discusses renewable energy and gases that constitute air components. Similarly, it align with [

57], who found that in Zambia, 47% of teachers believe the current curriculum lacks content on CC, 44% believe it provides insufficient knowledge, and only 9% think it provides adequate knowledge. After conducting the instruction sessions, most fifth and sixth-grade pupils (96.5%), stated that CC awareness is well-established in their school. They also revealed they have learned about CC in natural science, physics, chemistry, history, geography, civic and moral education and French modules. This study's findings are comparable to those from [

22] in which students learned mitigation and adaptation strategies for climate change, greenhouse gases, and energy balance. They were introduced to four mitigation strategies: energy efficiency, transportation conservation, building efficiency via decreased heat and energy usage or alternative energy sources, and efficient power generation. Students were also introduced to units on sea level rise and the effects of melting ice on land.

Data from the pre-test revealed that approximately half of the pupils (62.3%) stated that it is important to learn about the causes, impacts, greenhouse gases, mitigation, and adaptation of climate change. After the intervention, pupils showed a high level of interest in the findings, which indicated that most fifth- and sixth-graders (84.2%) stated that it is important to learn about the greenhouse effect, its causes, and its impacts on people, the economy, and the environment of Mali, including mitigation and adaptation strategies. These findings corroborate those found in earlier studies among Ghanaian students [

45], which report that 86.7% of students desire to learn about CC, and 65.8% of respondents are willing to take a CC course as a free choice. The study by [

36] found that most Tongan students (85.0%) indicated that it is very important to learn about the causes, impacts, and effects of climate change on their families (83.0%). All participants, 84.2%, of the teachers indicated that learning about CC mitigation, adaptation, and its impact on nature is very important. Most teachers found it important to learn about CC causes, the effects of greenhouse gases, and their impact on families, the economy, and nature.

The overall assessment (pre and post-test) showed that the correlation between pupils' concern about and attitudes towards CC is not statistically significant. However, a positive association was observed. According to the findings, pupils' concerns about CC are positively associated with their awareness. Their CC awareness correlates positively with their knowledge of CC causes. Therefore, these relationships show no statistically significant association. This result is consistent with a study in North Carolina [

40], which found a positive association between CC concern and pro-environmental behaviour [

58], indicating that hope and concerns about CC are significantly associated with changes in knowledge. This study builds upon previous research results by [

53], which found that the knowledge of senior high school students about global warming significantly correlates with their environmental attitudes. The findings indicate that the correlation analysis between pupils' knowledge of CC causes and their understanding of CC mitigation and adaptation is statistically significant in both the pre-and post-tests. Data also report that pupils' perceptions of CC impacts significantly correlate to their motivation to act on CC. Moreover, the participants' gender was positively associated with their desire to learn about CC, and no statistical significance was reported. These mirrored the studies of other countries [

40,

41,

42,

43,

44,

45,

46,

47,

48,

49,

50,

51,

52,

53,

54,

55,

56,

57,

58] who claimed that CC concerns of the United States students are associated with pro-environmental behaviour, including household behaviour such as turning off lights and closing the refrigerator door, addressing information-seeking behaviour such as asking others about what to do about environmental problems, and addressing transportation choices: walking for transportation. The research findings are comparable to the studies conducted on Finnish students' knowledge of and attitudes towards CC, views of mitigation and its predictors of willingness to act [

33,

46] indicate that gender is positively associated with CC mitigation and adaptation, including the desire to act on it. In addition, the study findings mirrored those reported in Israel [

59], which indicated that teachers' knowledge about CC impacts significantly correlated to their concerns and willingness to act.

5. Conclusion

This research aims to examine the perceptions, knowledge, motivations, and views of fifth- and sixth-graders regarding climate change education in the curriculum. This study proved that pupils revealed misconceptions about climate and weather in their current views. Therefore, they mostly addressed the conflation between climate and weather in their post-test findings. Although climate change is a serious problem for Mali, pupils' perceptions and knowledge of climate change-related issues were limited, particularly regarding the causes of climate change and the adaptation and mitigation strategies to mitigate its impacts. Considering perceptions and knowledge, the respondents were motivated to act on climate change, and this motivation was not directly related to their desire to learn more about it. This could be explained by the absence of climate change-related topics in their respective syllabi. Whereas they mostly reported being neutral about climate change-related topics in their syllabus, such as modules in geography, history, sciences, physics, chemistry, moral and civic education, and French education.

The post-test findings explicitly indicate that climate change education was productive. Therefore, pupils reported being able to clarify the concepts of climate and weather. Pupils were more concerned about climate change and hoped for something to be done about it. Climate change education enhanced the study participants' understanding of climate change causes, impacts, mitigation strategies, and adaptation measures. It provided an intellectual space for pupils to explore what they both knew and did not know about climate change by putting them at the forefront of the teaching process to address their shortcomings. They were highly motivated to take action against climate change. Learning about climate change was mostly important among learners, as it is integrated across their subjects. As we can see, a statistical relationship exists between pupils' awareness, knowledge and motivations.

This research assessed the significance of climate change curriculum-based education among young learners by evaluating their current thoughts about climate change-related issues and exploring what they understood about the subject matter during the instruction. This study emphasized the value of climate change education in providing Malian fifth— and sixth-graders with sufficient, sophisticated information about the causes, consequences, mitigation, and adaptation to climate change, as well as pro-environmental behaviours.

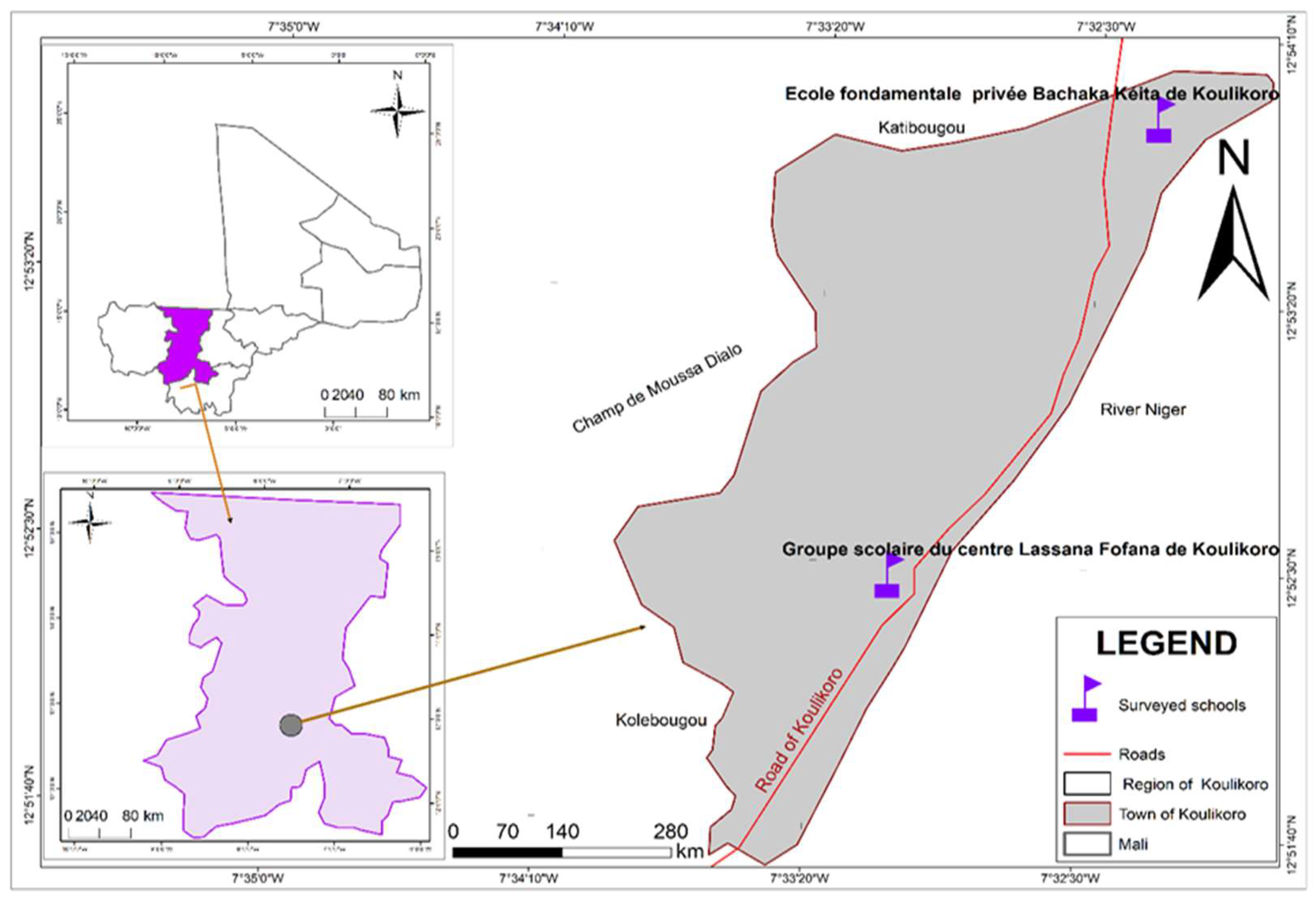

However, the relatively small sample size, comprising fifth— and sixth-grade pupils from two primary schools in Koulikoro, may not fully represent the broader population of primary schools in Mali. The reliance on self-reported data could introduce bias or inaccuracies. Additionally, the study did not account for external factors such as family background, media exposure, or community engagement, which could influence pupils' perceptions, knowledge and motivations of climate change. The pedagogical approaches and tools were not explicitly discussed and the multidisciplinary education was conducted within a short duration. To address these limitations, future research could expand the sample size and include schools from various regions of Mali to obtain a more comprehensive understanding of pupils' CC perceptions, knowledge and motivations. Longitudinal studies could assess how these perceptions, knowledge, and motivations evolve using a qualitative approach, particularly following specific educational interventions. Investigating the influence of family, community, and media would provide a more holistic view, and exploring the effectiveness of different pedagogical approaches in under-resourced schools could identify the most impactful strategies for fostering climate-conscious citizens in Mali and similar contexts.

This research could facilitate the reevaluation of educational systems to be more climate change-conscious, enabling students to become more engaged, coherent, and responsible citizens. Therefore, we suggest extending climate literacy beyond the geography and natural sciences to include it in other academic disciplines, such as technology, history, physics, chemistry, moral and civic education, and the arts. We also suggest encouraging teachers to develop their capacity for addressing climate change. This study also suggests the prominent integration of climate change into curricula and educational materials, encompassing both initial and ongoing training for educators and teachers.