1. Introduction

The blockchain is a digital ledger used to securely record information. This ledger is often publicly available but cannot be modified or destroyed. Such immutability is achieved through cryptographic functions, including hash functions and public key cryptography. The applications of these cryptographic constructions are numerous and range from virtual currencies (Bitcoin, Ethereum, …) to insurance, defense, automotive, and more [

9].

In [

7], the authors developed a quantitative framework to analyze the security and performance implications of various consensus and network parameters of Proof-of-Work (PoW) blockchains. They focus on adversarial strategies for double-spending and selfish mining. Their framework employs Markov Decision Processes (MDPs) defined as

where

S is the state space,

A is the action set,

P denotes the transition probabilities, and

R represents rewards. For selfish mining, a transformed reward function

balances the relative revenue

, enabling policy optimization via binary search. Their results reveal that shorter block intervals (e.g., Ethereum’s 10–20 seconds) require significantly more confirmations (37 vs. Bitcoin’s 6) to achieve comparable security under 30% adversarial power. The model demonstrates that efficient block propagation mechanisms mitigate stale rates, allowing higher throughput (60+ tps) without compromising security. This work provides the first systematic comparison of PoW variants, linking network-layer parameters to attack resilience. Blockchain technology provides decentralized and secure transaction verification; however, the rational and adversarial behavior of participants introduces strategic challenges affecting network stability, security, and efficiency. Game theory—a mathematical framework for analyzing strategic interactions—has been extensively applied to address these issues.

We recall here game-theoretic models in blockchain formulated in [

13], focusing on security threats (selfish mining, majority attacks, and denial-of-service attacks), mining management (computational power allocation, pool selection, and reward distribution), and economic incentives (transaction fee optimization and energy trading). We define blockchain interactions as a strategic game

, where:

represents the set of players (miners, pools, users).

is the strategy set of player i, where .

is the utility function of player i, which they seek to maximize.

Each model is analyzed through different equilibrium concepts, such as Nash equilibrium, subgame perfect equilibrium, and Stackelberg equilibrium, ensuring that no player has an incentive to deviate unilaterally.

Non-Cooperative Game for Selfish Mining

Miners decide whether to mine honestly (H) or adopt a selfish mining strategy (S) by withholding blocks to gain an advantage. The game is defined as:

Players: (miners).

Strategies: for each miner i.

Utility Function:

where

is the expected reward and

is the mining cost. A

Nash equilibrium occurs if no miner benefits from deviating:

This means that if one miner deviates, their utility will not increase, ensuring strategic stability.

Stackelberg Game for Transaction Fee Optimization

A Stackelberg game models the interaction between blockchain users and miners:

The user’s utility function is:

where

represents the transaction value. The miner’s utility function is:

where

is the reward and

is the mining cost. The

Stackelberg equilibrium is determined by:

This ensures that the miner chooses the best response given the transaction fee.

Stochastic Game for Majority Attack Prevention

To analyze majority attacks, we use a stochastic game in which miners dynamically adjust their strategies:

The

utility function is:

The

Markov Perfect Equilibrium (MPE) satisfies:

This means that miners’ strategies depend only on the current blockchain state, ensuring optimal responses at every stage. Game-theoretic models provide essential insights into blockchain security, efficiency, and incentive mechanisms. By mapping interactions to Nash, Stackelberg, and Markov equilibria, we can derive strategies that minimize risks and optimize network performance. The authors highlight adaptive learning models, hybrid consensus mechanisms and economic stability in blockchain as potential future application of game theory.

This survey [

13] synthesizes game-theoretic methodologies applied to blockchain systems, emphasizing formal mathematical frameworks and their role in resolving decentralized network challenges. Game theory provides rigorous tools to model strategic interactions among rational agents (e.g., miners, pools, users) and to design incentive-aligned protocols. Key models include:

Non-Cooperative Games. Players optimize individual utilities

without cooperation, converging to Nash equilibria (NE) where no unilateral deviation is profitable:

These models analyze selfish mining, computational power allocation, and pool block-withholding attacks (PBWH). For example, miners optimize infiltration rates in PBWH games to balance rewards and costs, with concave utilities ensuring a unique NE [

10,

11].

Stackelberg Games. These model hierarchical interactions between leaders (e.g., service providers) and followers (e.g., miners), solved via backward induction. A strategy pair

is a Stackelberg equilibrium if:

Applications include edge computing resource pricing and transaction fee mechanisms [

12].

Stochastic Games. These are multi-state dynamic games with transitions governed by strategies. Players maximize discounted payoffs across states, converging to a Markov Perfect Equilibrium (MPE). Applications include fork chain selection and the dynamics of selfish mining.

Extensive-Form Games. Representing sequential decision-making as game trees, these games are solved by finding subgame perfect equilibria, for instance in analyzing collusion in cloud computing and fork resolution.

Coordination/Coalitional Games. Here, players align their strategies to maximize collective welfare (e.g., potential games) or form coalitions. Applications include stabilizing blockchain versions during forks and optimizing pool formation.

Key Results

Security: Zero-Determinant (ZD) strategies [

11] can enforce cooperative mining equilibria, deterring selfish attacks.

Mining Management: Repeated games and evolutionary dynamics help stabilize pool selection, preventing centralization.

Consensus: Proof-of-Stake (PoS) protocols use stochastic games to penalize deviations, ensuring honest validation.

Future Directions:

Integrating mean-field games for large-scale miner interactions.

Designing mechanism-aware blockchains via Bayesian games under incomplete information.

Expanding Stackelberg frameworks to edge computing and IoT-blockchain ecosystems.

By mapping game-theoretic equilibria to blockchain incentives [

13], the authors underscores their efficacy in securing decentralized networks, optimizing resource allocation, and enabling scalable applications.

The objective of this paper is to review the cryptographic and formal definitions of the blockchain, recall the relational model (RM) used in the study of database (DB) systems, and apply the fundamental concepts of the RM to formalize and define the security setup and related concepts of the blockchain. Having clear definitions of the concepts on which the security and mechanics of the blockchain rely helps in understanding and analyzing the system.

Let

and

be two blockchains. We define the principle of adding blocks in the form of an algorithm like this 1.

|

Algorithm 1 Block Addition |

Require: Two blockchains and and a block b

Ensure: Append b to the longest blockchain

- 1:

if length() ≥ length() then

- 2:

Add b to

- 3:

else - 4:

Add b to

- 5:

end if

|

Modern cryptography is a science that follows rigorous procedures to prove the security of cryptographic schemes [

8]:

Definition of Security: This specifies the goals achieved by a cryptographic scheme.

Assumptions: These are the intractable computational problems (e.g., the difficulty of factoring large numbers or the discrete logarithm problem) upon which the security of the scheme relies.

Proofs: These demonstrate that the scheme achieves the defined security if the assumptions hold.

Assumption 1. The security of the blockchain is based on the following assumption: “The majority of the miners are honest.”

Proposition 1. Adversaries are unable to append a malicious block.

Proof. Suppose that a malicious miner (MM) succeeds in adding a dishonest block (DB). This implies that MM has built a blockchain longer than the honest blockchain. In other words, MM possesses more computing power than the majority of the users, which violates our assumption. □

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows. We formally define the fundamental blockchain related concepts in

Section 2. After that, we recall the relational model used to study data base systems in

Section 3. We also consider a schema (the entity/association model) for the blockchain in

Section 4. We show in

Section 5 how to apply the algebraic query language to define fondamental concepts. We finally conclude the paper in the last section.

2. The Blockchain

Several attempts to conceive distributed digital money have been made. For example, B-cash was an early attempt. However, it was with the advent of Bitcoin that the concept was widely adopted and recognized. The term Bitcoin can refer either to the digital currency or to the underlying protocol describing its implementation. It is built on the blockchain, a data structure containing blocks. Each block contains the hash of the previous block, a list of transactions, and associated metadata. A transaction is a data structure that includes the sender’s address, the receiver’s address, and the amount spent. Each Bitcoin account is identified by a public key and a private key. The private key is held exclusively by the owner, while the corresponding public key is published and used to receive Bitcoins. This paper is organized as follows.

Section 3 reviews the cryptographic building blocks. In

Section 4, we discuss the structure of the blockchain and the mechanism underlying Bitcoin. Finally, we conclude the paper.

2.1. The Cryptographic Building Blocks

Hash Functions

A hash function

h is defined as:

It maps an input string of arbitrary length to a fixed-length bit string of size

n. A well-designed hash function must satisfy the following properties:

Well-known hash functions include MD5 and SHA-1. Bitcoin uses

SHA-256, which produces a 256-bit output [

2].

Elliptic Curves

An elliptic curve is given by the equation

where

a and

b are parameters over a finite field that must satisfy

. The set of points on the curve forms a group under an appropriate addition law [

3]. Blockchain systems use elliptic curves for account creation. An account is identified by its private key

and public key

. Let

G be a generator of the group of points. Then,

The infeasibility of deriving

from

is guaranteed by the difficulty of the elliptic curve discrete logarithm problem. Bitcoin uses the curve

secp256k1 (with parameters

and

). In addition to account creation, elliptic curves are used for message signing in the blockchain protocol. We discuss electronic signatures in

Section 2.1.

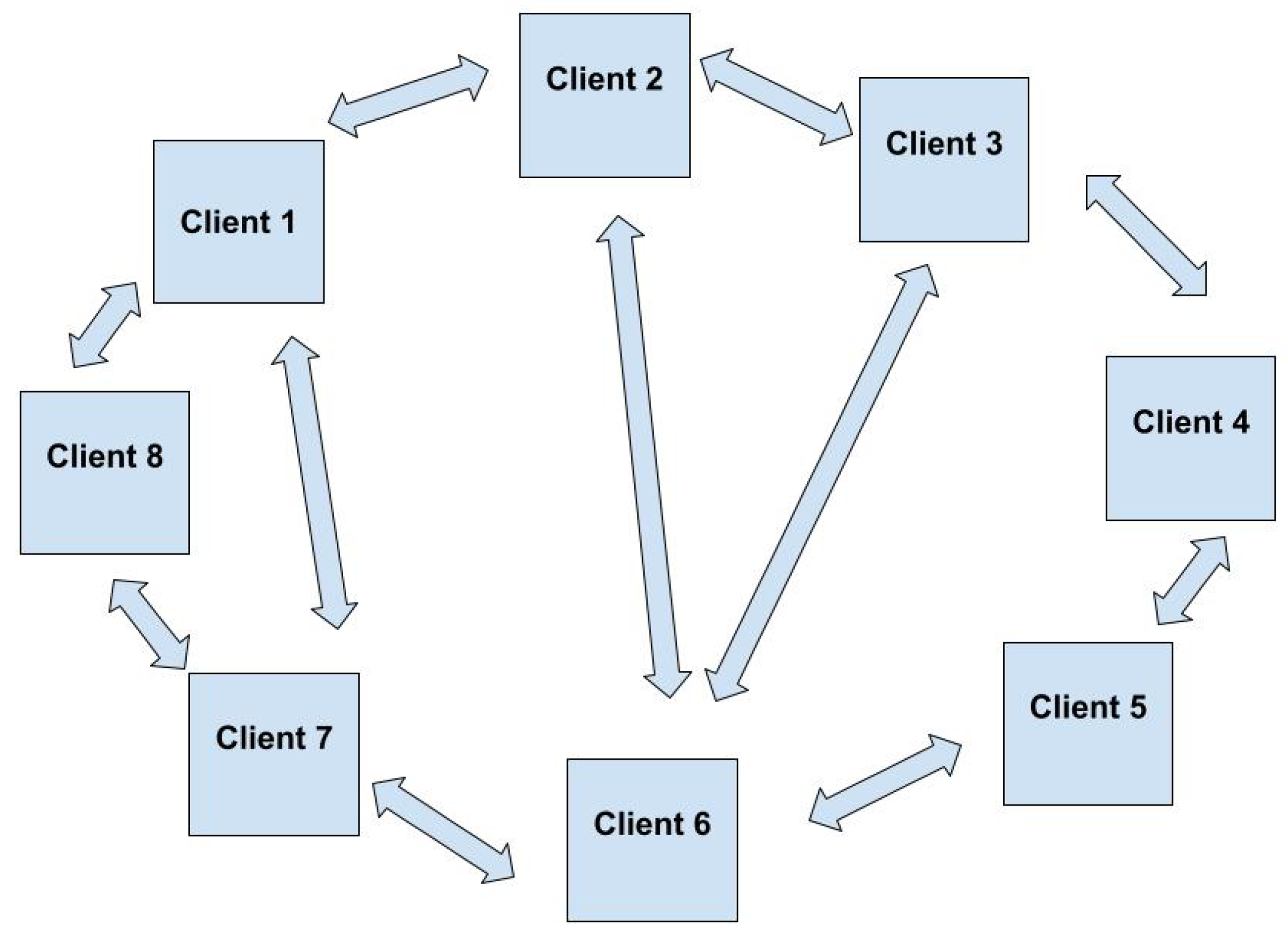

The Peer-To-Peer Networks

Unlike the traditional client-server architecture, peer-to-peer networks allow for direct exchange of files between clients. For such systems to work, dedicated software (e.g., Napster, Gnutella, …) is required.

Figure 1.

Peer-To-Peer Network

Figure 1.

Peer-To-Peer Network

As stated in [

4], “In finance, the term peer-to-peer refers to the exchange of crypto-money or a digital asset through a distributed network.” During its conception, Satoshi Nakamoto described Bitcoin as an electronic cash system operating over a P2P network. A ledger, called the Blockchain, is stored on each network node and updated as transactions are added.

The Electronic Signature

We describe here the mechanism of the electronic signature. Let M be a message to be signed and H a hash function. Let be the private and public keys, respectively. To sign and verify the message, the sender (S) and the receiver (R) proceed as follows:

S computes and encrypts it using an asymmetric encryption scheme: ; then S sends to R.

Upon receipt, R decrypts s using the public key: , and compares d with .

If d matches , then R is authenticated, since only S possesses the private key required for encryption.

Regarding the encryption scheme, either RSA or an elliptic curve–based scheme can be used.

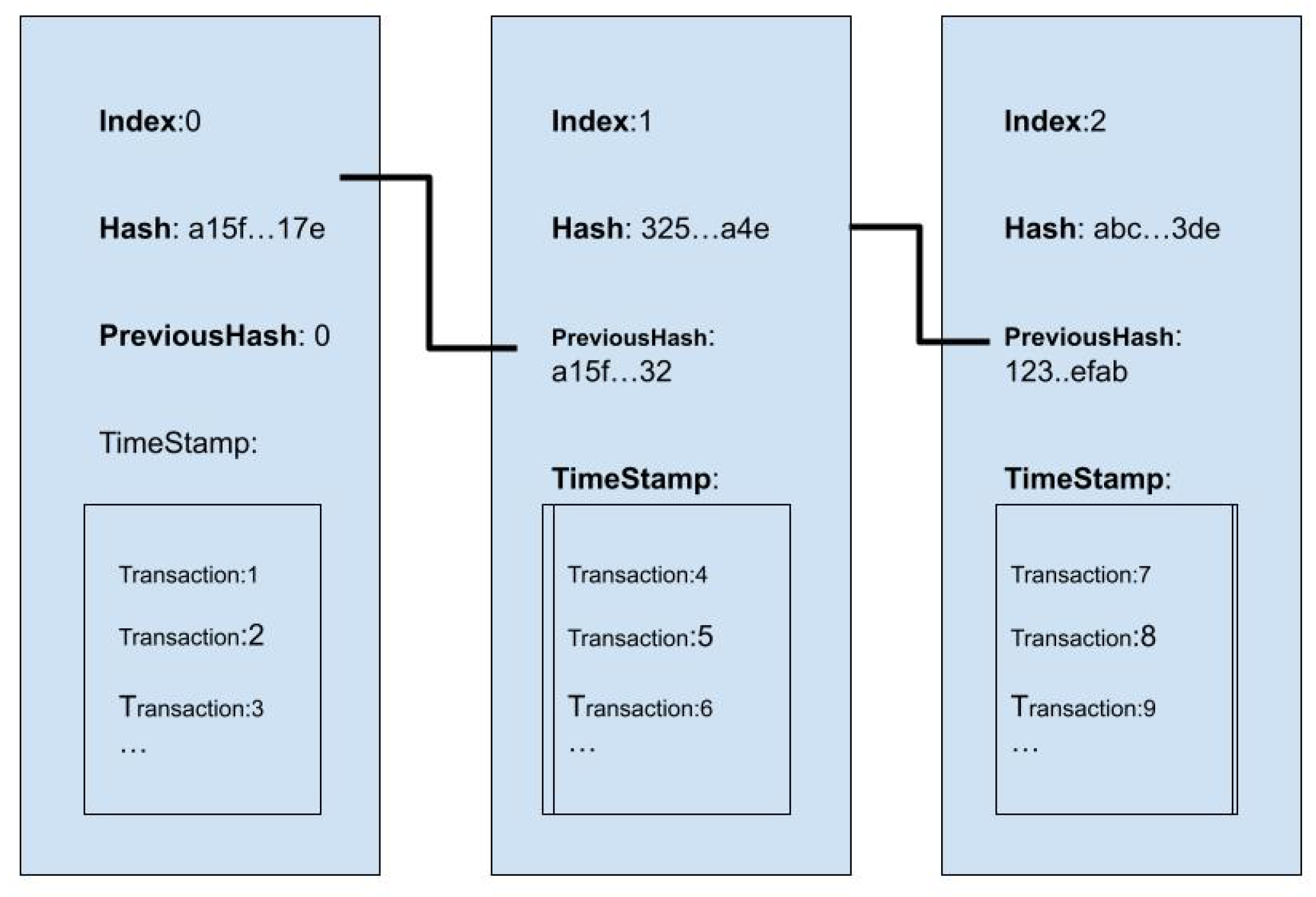

2.2. The Blockchain

The blockchain is a ledger, or data structure, containing blocks linked by hashes, as illustrated in the figure below.

As described by J.P. Delahaye, the blockchain “is a book, freely accessible, on which everyone can write and read, but which cannot be destroyed or erased.” The cryptographic properties achieved by the blockchain design are the following [

6]:

Decentralization: There is no central authority controlling Bitcoin. Unlike traditional monetary systems where an account is managed by a central entity, Bitcoin uses the Unspent Transaction Output (UTXO) model to compute user balances.

Unforgeability: Illegitimate claims of Bitcoin ownership are prevented through digital signatures.

Double-Spending Resistance: Bitcoin was the first major digital currency to solve the double-spending problem [

5]. Double spending refers to the ability of an owner to spend the same coins more than once. This is prevented by recording each transaction on the public blockchain, which is immutable due to the Proof-of-Work (PoW) mechanism explained below.

Pseudonymity: Accounts are identified through public keys, providing a degree of anonymity for users.

2.2.1. The Blocks

As discussed above, the blockchain consists of blocks chained by hashes. Approximately every 10 minutes, a block is appended to the Bitcoin blockchain. This can be modeled as a set:

where

is the genesis block and

is the latest block. Each block contains:

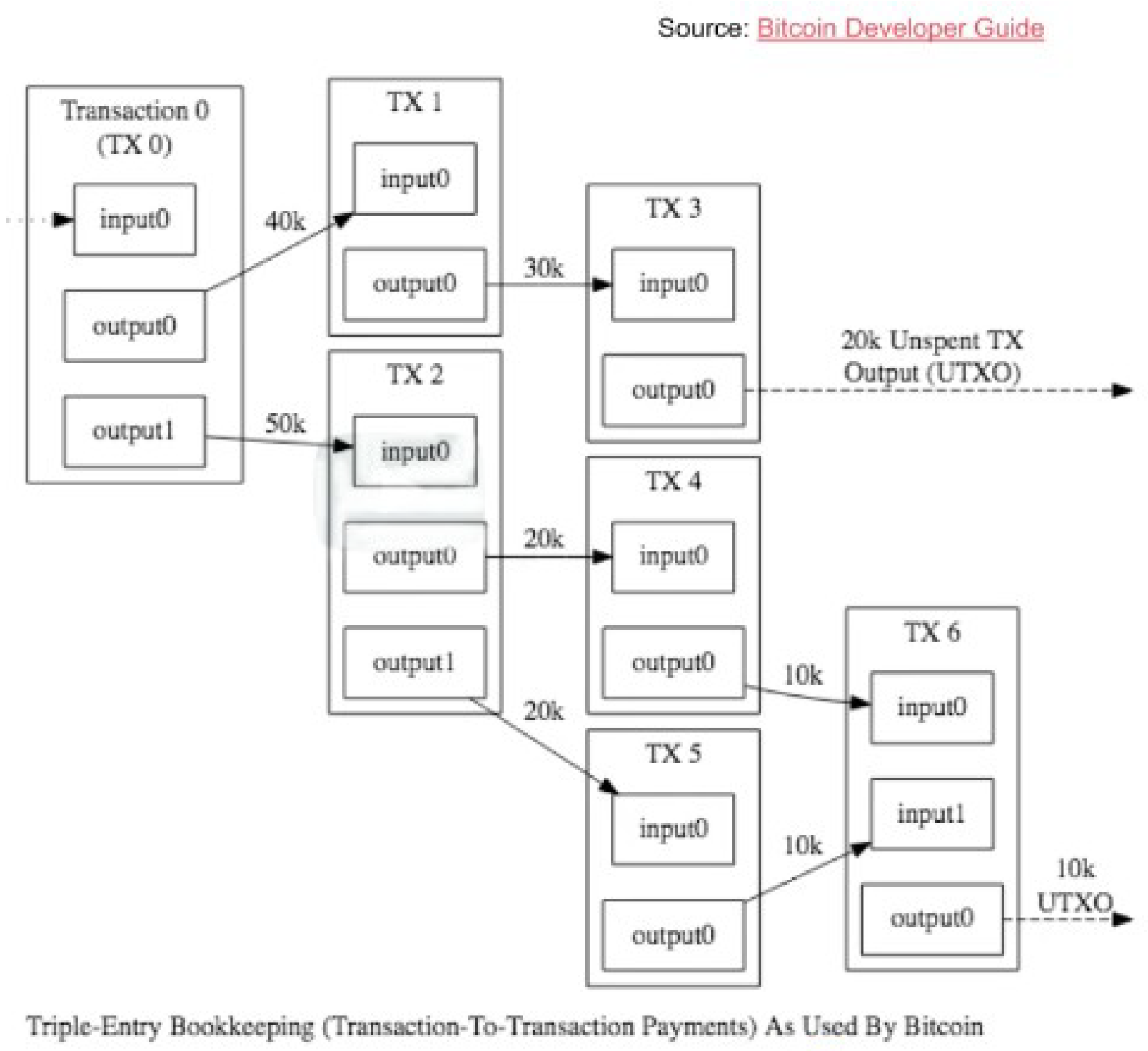

2.2.2. The Transactions

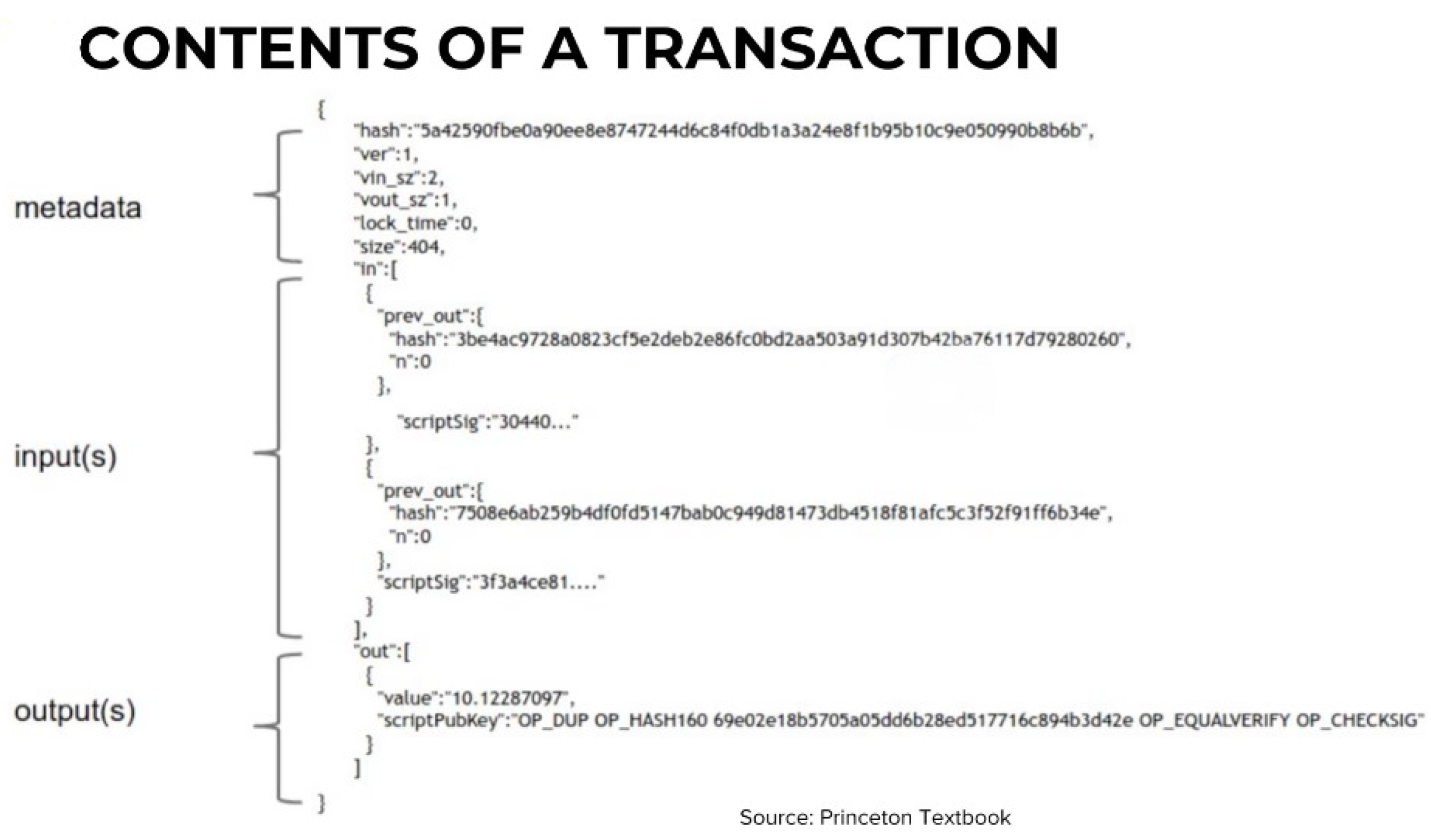

A transaction is a data structure containing the following fields:

The flow of transactions is illustrated in the figure below:

Figure 3.

Transactions Flow

Figure 3.

Transactions Flow

The structure of a transaction is illustrated in

Figure 4.

Note that the

scriptSig field is known as the locking (or unlock) field because it enables the sender to spend the UTXO (Unspent Transaction Output). The

scriptPubKey field is known as the locking script, as it encodes the condition that the output can be spent only by the designated public key. The unlocking script from a previous transaction output is combined with the locking script of a new transaction input; the parameters are then placed on the stack and the code is executed. If the code returns true, the transaction is considered valid [

5].

2.2.3. Bitcoin Mining

The term mining refers to the process of adding a block to the blockchain. The process works as follows:

Transactions are broadcast to all nodes in the network.

Nodes specialized in mining, called miners, listen to the network and collect broadcast transactions into blocks.

A miner solves a puzzle (Proof of Work, PoW), as explained below. If successful, other miners confirm the correctness of the solution.

The block is added to the blockchain, and the miner receives Bitcoin as a reward.

The PoW algorithm works as follows: Let y be a network parameter.

The difficulty for solving the PoW is adjusted over time so that a block is added approximately every 10 minutes.

Proposition 2. This procedure makes cheating on the network computationally intractable.

Proof. The nodes validating a block agree that the longest blockchain is the valid one. Suppose an attacker wants to insert an invalid block at position i in a blockchain containing N blocks. The attacker must calculate and validate blocks. Since mining a block takes on average 10 minutes, the attacker would need minutes to achieve this. Moreover, because consensus is based on the longest blockchain being accepted as honest, the attacker would fail to have the invalid chain validated. □

2.3. An Algorithmic Description

In this section, we describe the main protocols of the blockchain.

2.3.1. Proof of Work

PoW is the process with which miners compete for block addiction. They do that by solving a cryptographic puzzle described here 2. The miners compute a nonce which requires computational power and time. The verification of the correctness of the nonce (validation) is immediate. The difficulty allows for the block addition time to be adjusted.

|

Algorithm 2 Proof of Work |

Require:

Ensure:

while

do

generate

end while

|

2.3.2. Transaction Validation

The transaction validation process ensures that the transaction is spending from the right previous transaction, check for the validity of the signature of the owner (authenticity) and that the sender has the right to spend from the previous transaction 3.

|

Algorithm 3 Transaction Validation |

Require: A previous transaction

Require: and the current transaction

Ensure: The transaction is valid if and is valid and then

The transaction is valid end if

|

2.3.3. Technical Issues

We point out in this section common issues faced in the blockchain ecosystem.

Storage Requirements: The blockchain requires a significant amount of storage capacity.

Scalability: The number of transactions per second is much lower than in traditional payment systems.

Energy Consumption: The PoW mechanism requires significant power consumption, prompting researchers to explore alternative consensus mechanisms.

Fees: The current implementation of Bitcoin imposes high fees for sending money through the blockchain network compared to traditional payment systems.

3. The Relational Model

The relational model represents data as a two-dimensional table called a relation [

14]. The columns of this table are called attributes. An alternative representation of a relation is by its schema:

In the relational model, a database is a set of relations. We require that the domain (the set of values that an attribute can take) is of elementary type (e.g., integer, date, or string). Note that in a relation (viewed as a table), the order of the rows (tuples) is not important and can be rearranged arbitrarily. We can then formulate the following definition:

Theorem 1. A relation is a set of tuples.

Relations are updated regularly as tuples are inserted or deleted. Changes to the schema of a relation are less common since they may involve processing huge amounts of data. We then define:

Theorem 2. A set of tuples for a given relation is an instance of that relation.

The relational model also allows us to define the concept of a key for a relation:

Theorem 3.

A set of attributes forms a key for a relation if, for any tuples and in R,

For example, if

forms a key for the relation

R, then we write:

It is conventional in database systems to use a uniquely generated value as the key rather than a subset of the attributes. So far, we have discussed how the data model defines the structure of the data. Next, we consider the interaction and manipulation of data.

Theorem 4. A data model defines both the structure and a set of queries for data retrieval and modification.

3.1. Algebraic Query Language

Let R and S be two relations and let be the attributes of relation R. The Algebraic Query Language (AQL) consists of the following operations:

Projection : The result is a relation with only the attributes .

Selection : Let C be a condition on the tuples of R that evaluates to true or false. The result is a relation that contains the same attributes as R but only the tuples satisfying C.

Cartesian Product : The relation contains the attributes of both R and S. Its tuples are obtained by taking the Cartesian product of the tuples of R and S.

Natural Join : If R and S share a set of attributes , then consists of the tuples from the Cartesian product of R and S that agree on these attributes.

Intersection and Union: The intersection () and union () of two relations are obtained by respectively taking the common tuples or the combined set of tuples from R and S.

Example 1: Consider the query:

What are the hash values and the difficulty of the blocks mined before 2015 and whose version equals 1.5? The AQL translation is:

Example 2: To retrieve the entire blockchain, we use:

Here, the relation

links each block to the transactions contained within it. The shared attributes among these relations are the block hashes and the transaction hashes.

3.2. Constraints

A constraint restricts the data that may be stored in the database [15]. There are two ways to formulate a constraint:

Let E be an expression in relational algebra. Then the expression is a constraint, indicating that no tuple satisfies E.

If E and S are expressions in relational algebra, then means that every tuple in the result of E must also appear in the result of S.

3.3. Referential Integrity Constraints

Let

v be a value in attribute

A of some tuple in relation

R. We want to enforce the constraint that

v appears in a specified attribute of some tuple in another relation

S. This is an

integrity constraint, expressed as:

Now we discuss other concepts from the relational model that are relevant for this paper.

Functional Dependencies: Let

R be a relation. A functional dependency (FD) is a statement of the form “If two tuples in

R agree on all of the attributes

, then they must agree on another set of attributes

.” We write:

FDs satisfy properties such as splitting/combining, trivial dependencies, and transitivity.

Closure of FDs: Let

be a set of attributes and

S be a set of FDs. The closure of

under

S is the set of attributes

T such that any relation satisfying all FDs in

S also satisfies the FD

We denote the closure as

.

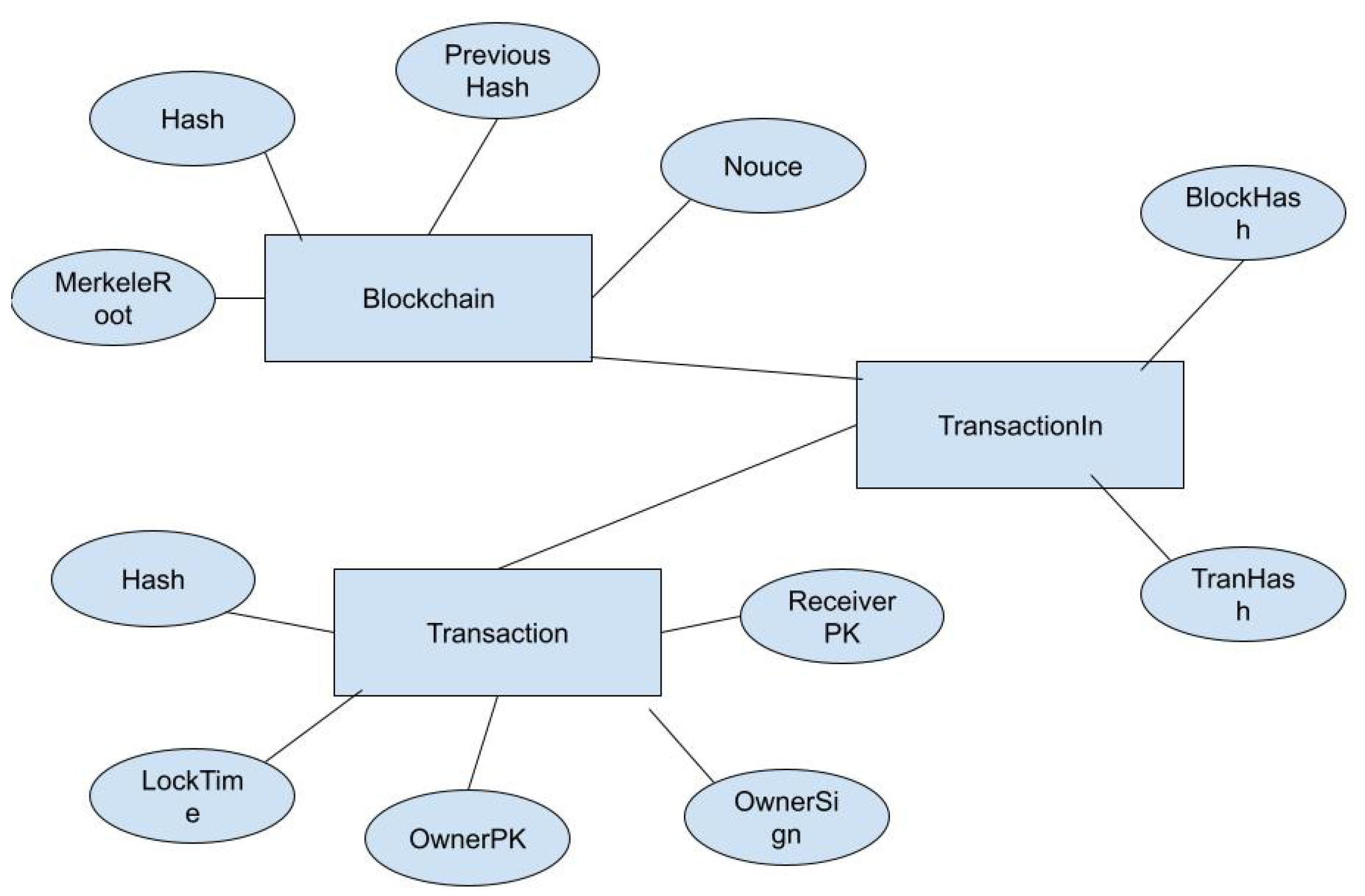

4. A Schema for the Blockchain

There are three relations. For ease of representation, we have omitted the Version, VinSz, VoutOutSz, lockTime and Size fields in the Transaction relation. For simplicity, we consider only transactions that redeem a single output and contain only one output address.

Blockchain(Hash, Version, PreviousHash, MerkleRoot, TimeStamp,

Difficulty, Nonce)

Transaction(Hash, OwnerPubKey, PreviousHash, OwnerSignature,

Value, ReceiverPubKey)

TransactionIn(BlockHash, TransactionHash)

5. AQDL for Blockchain

5.1. Transaction Validation

Let

be the current transaction we are validating and

be the previous transaction from which we are spending. The Pay-to-Public-Key (P2PK) can be described in terms of AQDL as follows: First, retrieve the transaction corresponding to the

OwnerPubKey of

:

If

and

match and

is valid, then the transaction is valid.

5.2. Balance

The balance

B of a user identified by their public key

is defined as the sum of all unspent transaction outputs:

In this expression, we select all transactions from the

Transactions relation where the attribute

ReceiverPubKey equals

. We then project the

Value attribute and sum the resulting set to obtain the balance.

5.3. Double Spending

Theorem 5. A malicious user attempts double spending if they try to redeem Bitcoins that have already been spent.

Let t be a transaction whose output address is . Let and be two transactions. Define the receiver address of as and that of as . The transactions and constitute double spending if the following holds:

.

.

and .

.

Intuitively, and double spend the same Bitcoins if they originate from the same owner, both have been validated, and they spend from the same transaction output address.

5.4. Selfish Mining

Selfish mining is a strategy in which a miner (or a coalition of miners) deliberately withholds discovered blocks rather than immediately broadcasting them. The objective is to gain a competitive advantage by creating a private branch of the blockchain and then releasing it strategically to override the honest chain, thereby capturing a disproportionate share of the block rewards. In a formal framework, selfish mining can be modeled as a non-cooperative game. Each miner

i has a strategy set

, where

H denotes honest mining and

S denotes the selfish mining strategy. The utility function for miner

i is given by:

where

is the expected reward and

is the associated mining cost. A Nash equilibrium

is reached when no miner can improve their utility by unilaterally deviating from their chosen strategy. Selfish mining becomes particularly effective when a miner controls a significant fraction of the network’s computational power. As demonstrated in [

11], the profitability threshold for selfish mining may be reached with as little as approximately 33% of the total hash power. Under these conditions, the selfish miner’s withheld blocks can cause honest miners to waste resources on an abandoned chain, thereby increasing the relative revenue of the selfish miner. This challenges the common assumption that the majority of miners are honest and highlights potential vulnerabilities in the blockchain consensus protocol.

Selfish mining runs as follows:

The selfish miner (SM) mines on his private blockchain priBC.

Honest miners (HM) mine on the public blockchain pubBC.

SM releases the priBC when .

The hash power of the HMs is split since the two chains are of the same length.

SM add a block to the priBC making it longer than the pubBC.

This result in the validation of the longest chain, discarding the pubBC, SM get rewards for his mined blocks, wast of mining power for HMs.

6. Conclusion

In this paper, we have presented a formal framework for understanding blockchain technology using the relational model. We reviewed key cryptographic building blocks, detailed the structural and operational aspects of blockchains, and provided formal definitions and algorithmic descriptions for critical processes such as transaction validation and Proof of Work. By mapping blockchain operations into algebraic expressions, we connected the worlds of databases and distributed ledgers. Furthermore, we integrated game-theoretic perspectives—particularly through the analysis of selfish mining—to emphasize how strategic behavior among miners can impact network security and efficiency. This multifaceted approach not only clarifies the underlying principles of blockchain technology but also highlights areas where further research is needed, such as alternative consensus mechanisms and improved incentive structures. Future work will focus on adaptive learning models, hybrid consensus protocols, and further exploration of mechanism design within blockchain systems to enhance scalability, security, and overall network performance.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| MDPI |

Multidisciplinary Digital Publishing Institute |

| DOAJ |

Directory of open access journals |

| TLA |

Three letter acronym |

| LD |

Linear dichroism |

References

- H. Cohen,G. Frey,R. Avanzi, Handbook of Elliptic and Hyperelliptic Curve Cryptography, Chapman & Hall/CRC, 2012.

- National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST), Secure Hash Standard (SHS), 2002, https://nvlpubs.nist.gov/nistpubs/FIPS/NIST.FIPS.180-4.pdf.

- C. Gonçalves, Cryptographie avancée, courbes elliptiques, Université of Paris-Est, M2-SSI, 2015.

- Milojicic, Dejan S. and Kalogeraki, Vana and Lukose, Rajmohan and Nagaraja, Kiran and Pruyne, Jim and Richard, Bruno and Rollins, Sami and Xu, Zhichenr, Peer-to-Peer Computing, 2002.

- How does a block chain prevent double-spending of Bitcoins?, https://www.investopedia.com/ask/answers/061915/how-does-block-chain-prevent-doublespending-bitcoins.asp, Accessed on June 2, 2022.

- Licheng Wang, Xiaoying Shen, Jing Li, Jun Shao, and Yixian Yang, Cryptographic primitives in blockchains. Journal of Network and Computer Applications 2019, 127, 43–58.

- Gervais, A. , Karame, G. O., Wüst, K., Glykantzis, V., Ritzdorf, H., & Capkun, S., On the Security and Performance of Proof of Work Blockchains, Proceedings of the 2016 ACM SIGSAC Conference on Computer and Communications Security, 2016.

- Katz, J. and Lindell, Y., Introduction to Modern Cryptography, 2nd ed., Chapman & Hall/CRC, 2014.

- Huaqun Guo and Xingjie Yu, A survey on blockchain technology and its security, 2022, Blockchain: Research and Applications.

- Nash, J. , Equilibrium Points in n-Person Games. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 1950, 36, 48–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eyal, I. and Sirer, E. G., Majority is not Enough: Bitcoin Mining is Vulnerable, in Financial Cryptography and Data Security, 2014.

- Osborne, M. J. and Rubinstein, A., A Course in Game Theory, MIT Press, 1994.

- Ziyao Liu, Nguyen Cong Luong, Wenbo Wang, Dusit Niyato, Ping Wang, Ying-Chang Liang, and Dong In Kim A Survey on Blockchain: A Game Theoretical Perspective. IEEE Access 2019, 7, 47615–47643.

- Jeffrey D. Ullman,Jennifer Widom, A first course in database systems, Prentice-Hall, Inc., 1997.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).