Submitted:

31 March 2025

Posted:

31 March 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Geological Background

3. Materials and Methods

4. Field Features

5. Petrography

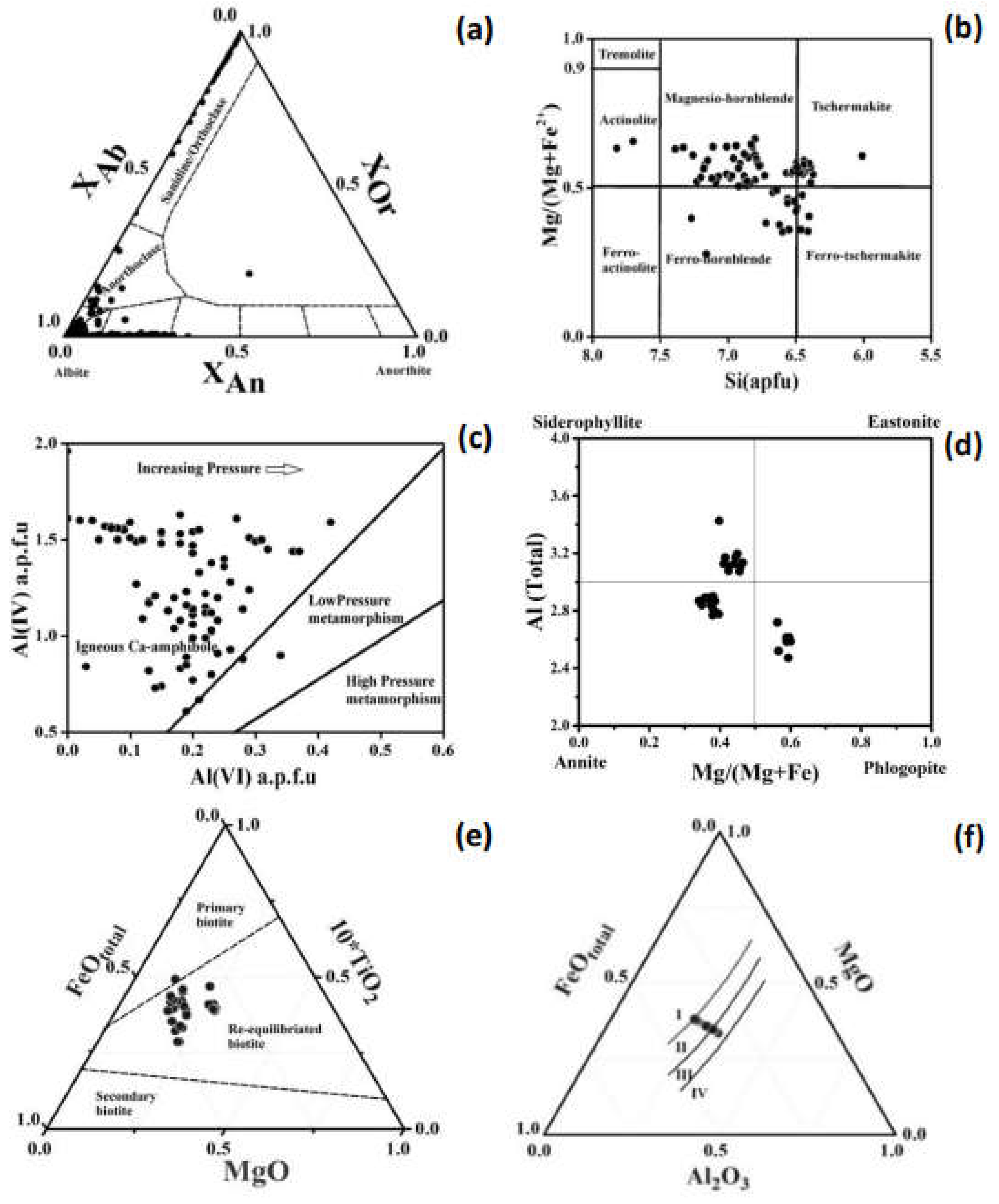

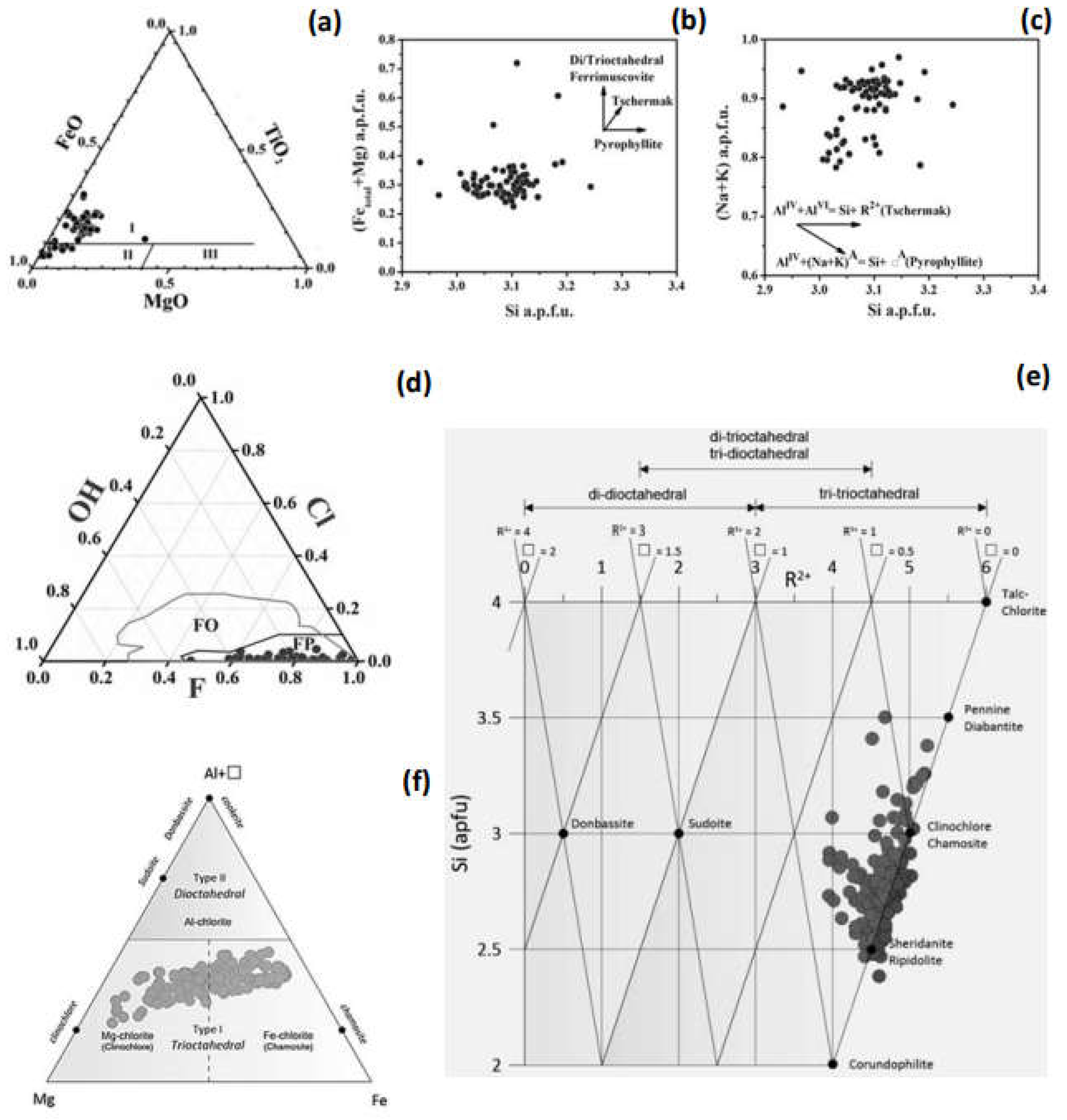

6. Mineral Chemistry

7. Results: Retrieval of Physicochemical Environment

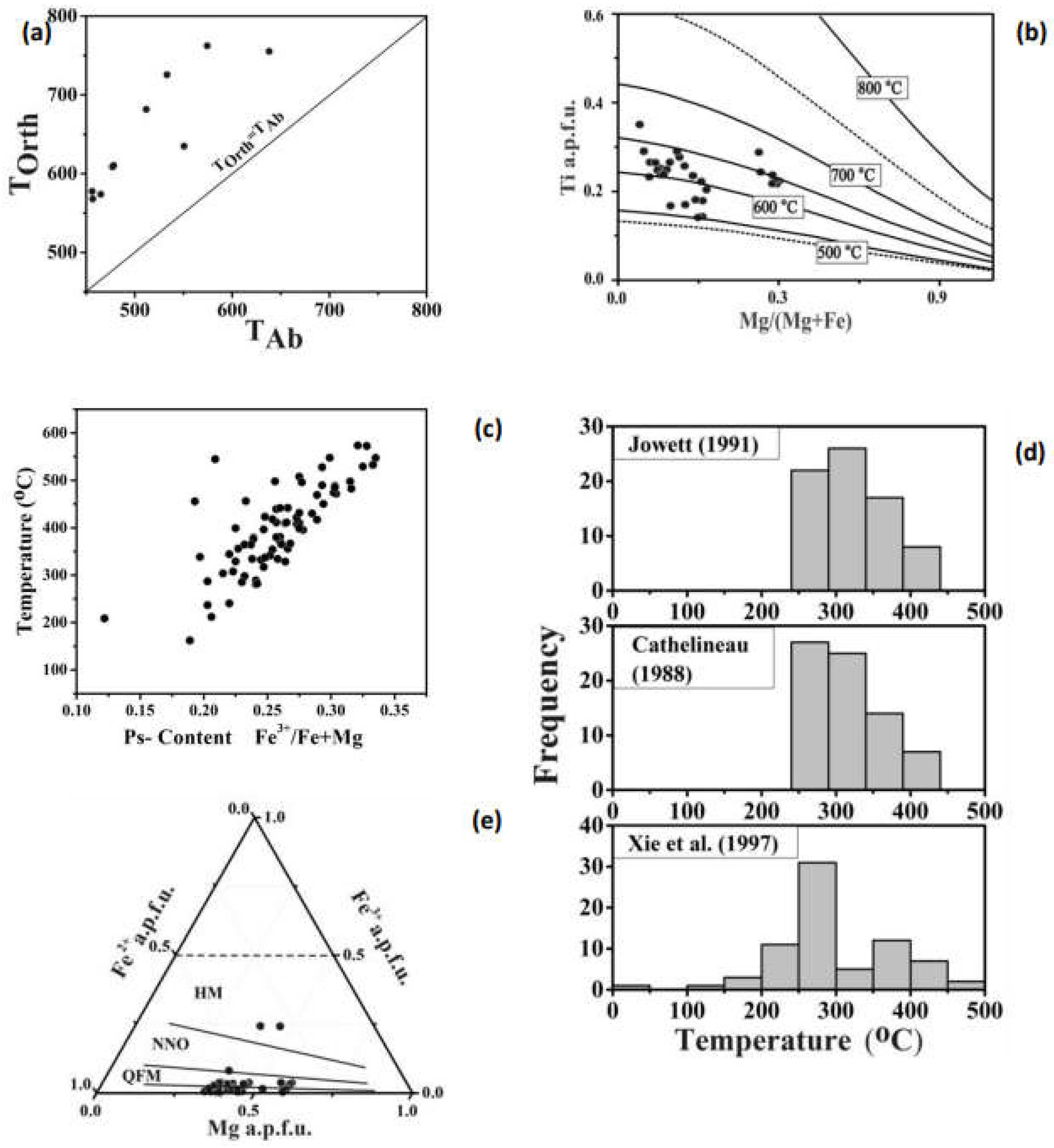

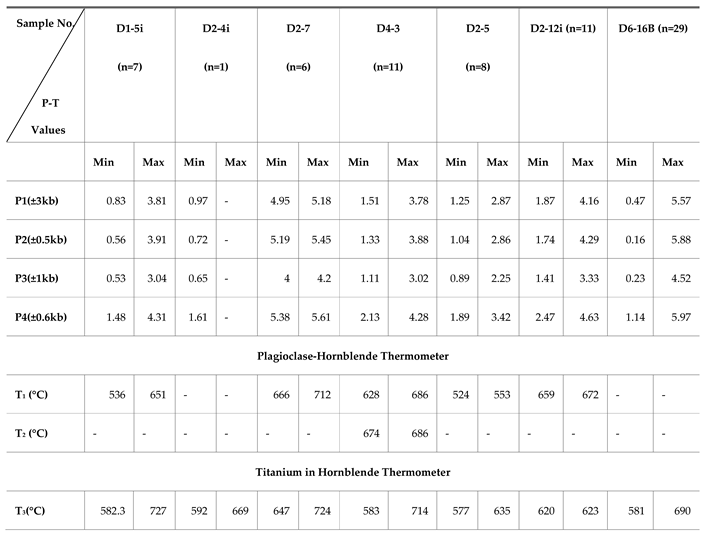

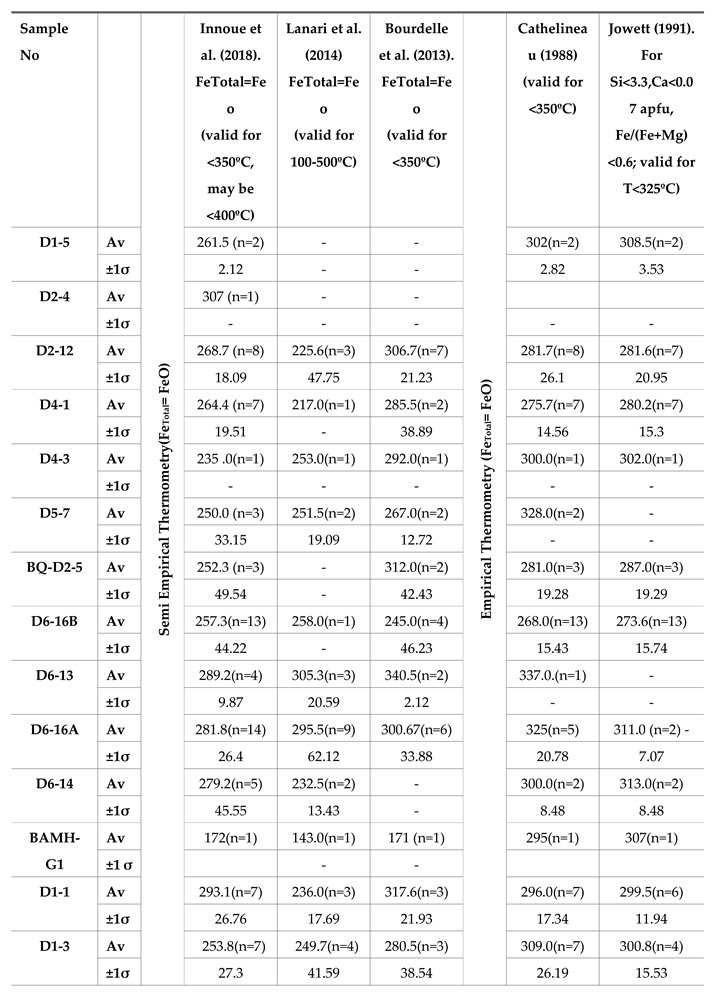

7.1. Mineral Thermobarometry

|

| Epidote + Mineral assemblage | Texture of Epidote | Pistacite Content |

Temperature (℃) | Remark |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Biotite |

Fully enclosed grains (n=13) |

0.26-0.33 | 450.2 - 573.6 (one 334.1) |

Ps=0.26 → T=334.1℃ Ps=0.27–0.29→T=450.2–547.7℃ Ps=0.29–0.33→ T=471.6–573.6℃ |

| partially enclosed grains (n=3) |

0.26 - 0.27 (one Ps=0.20) |

441.7 - 497.9 (one 286.9) |

Ps=0.20 → T=287 ℃ Ps=0.26–0.27→T=441.7℃–497.9℃ |

|

|

Plagioclase |

subhedral and resorbed outline (n=2) | 0.19 and 0.29 | 455 and 603.8 | Ps=0.29 → T=603.8 ℃ is outside the calibration value. |

| irregular type (n=7) |

0.23-0.27 | 328.4- 456.2 | ||

| Quartz | elongated prismatic crystals (n=4) |

0.26-0.29 | 355.8 – 416.8 | |

| Opaque | Fe- sulphide (n=14) |

0.21-0.30 (one Ps=0.12) |

332.4 - 474 (one T=208.7) |

Ps=0.12 → T=208.7 ℃ Ps=0.21 → T=211.9 ℃ Ps=0.23 –0.25→T=297.6–337℃ Ps=0.26– 0.30→T=365.1– 441.4℃ |

| Plagioclase or Quartz-feldspar | solution channel or fracture filling material (n=9) |

0.19 – 0.27 | 161.8 to 366 | Ps <0.25 (0.19-0.24) → T=161.8 -303.5 (n=7) Ps = 0.25-0.29 → T=317– 366 °C (n=2) |

7.2. Oxygen Fugacity

|

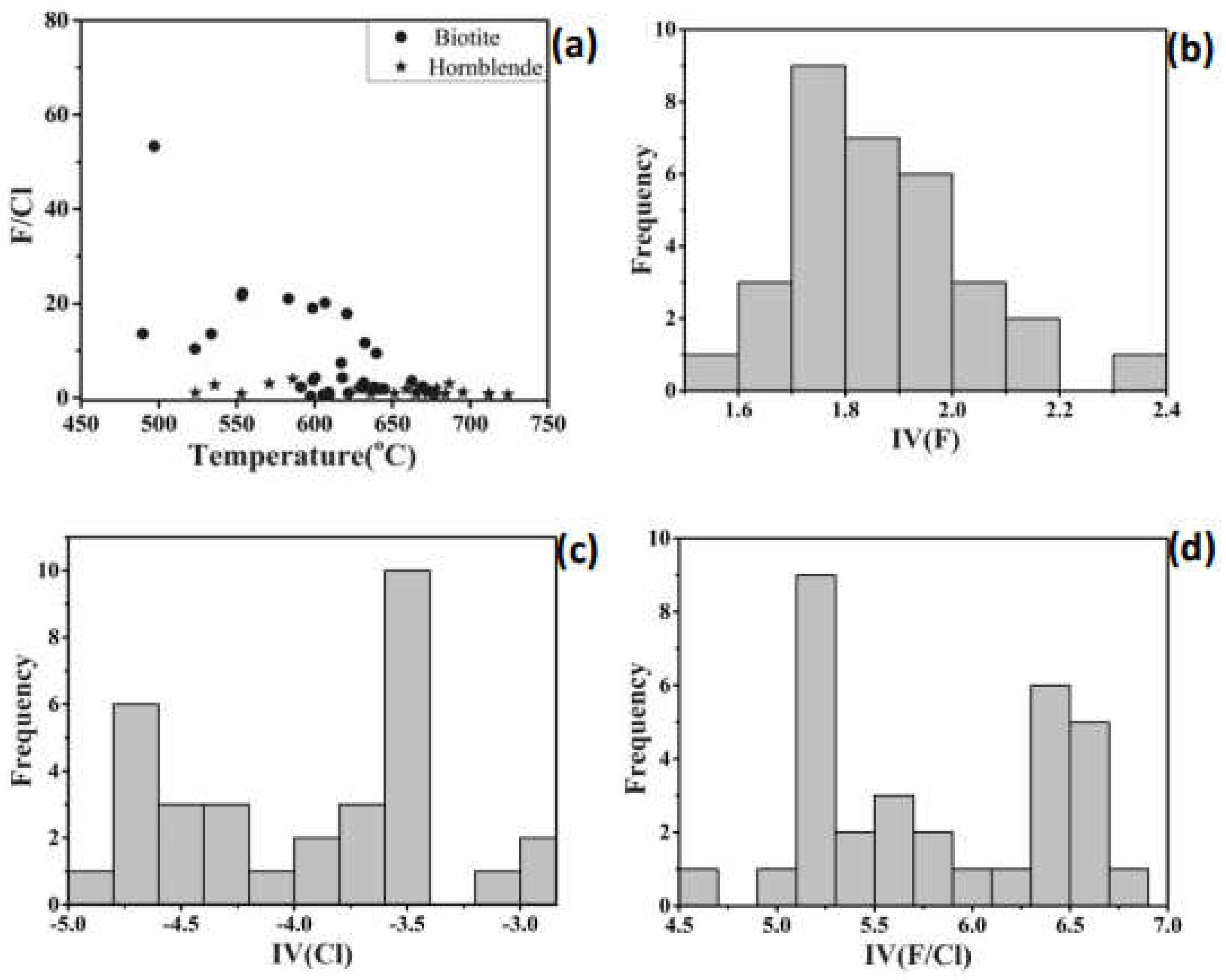

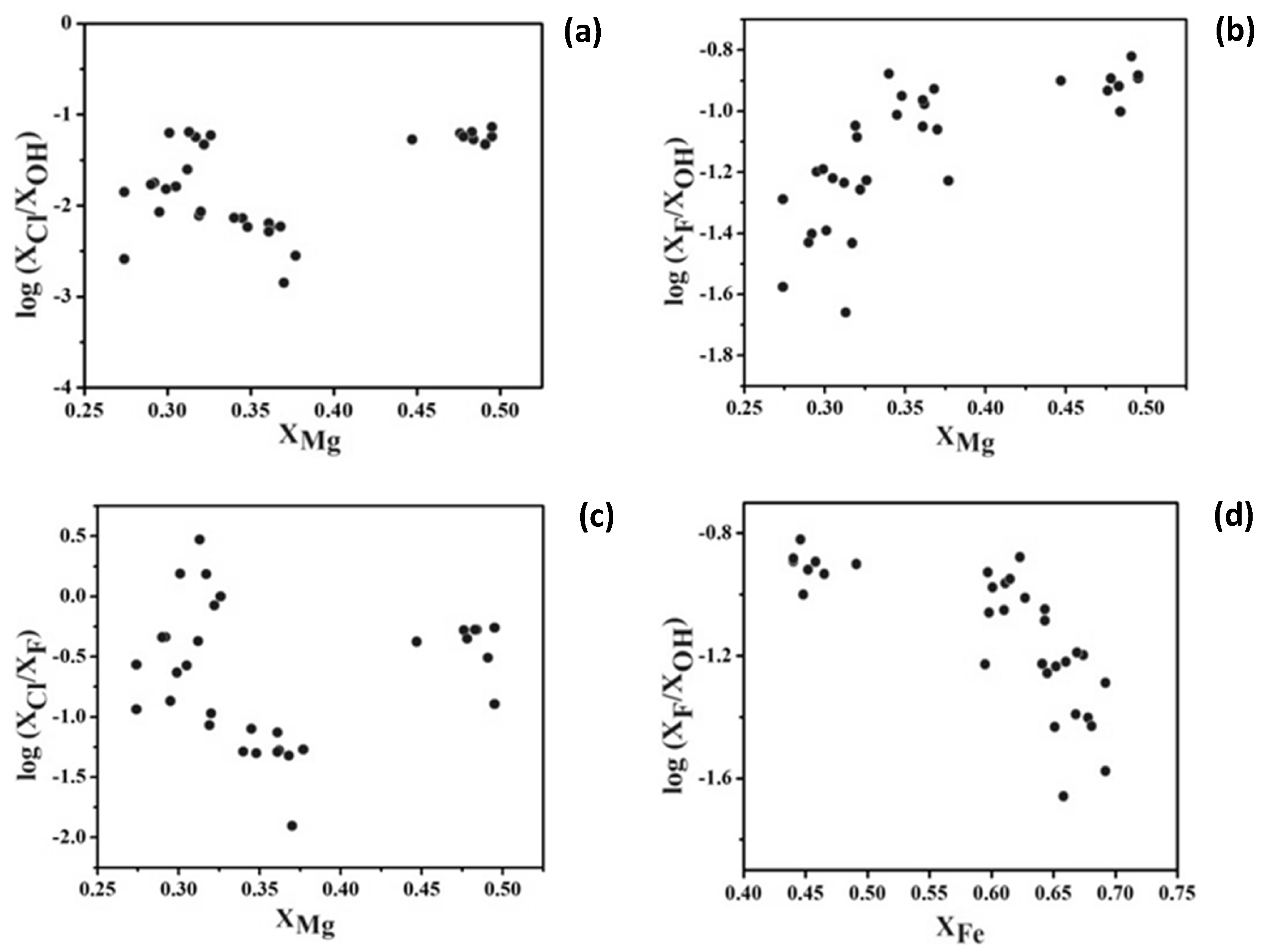

7.3. Volatiles in BG

Water Content

Halogen Content

8. Late- Stage Fluid Characteristics in BG

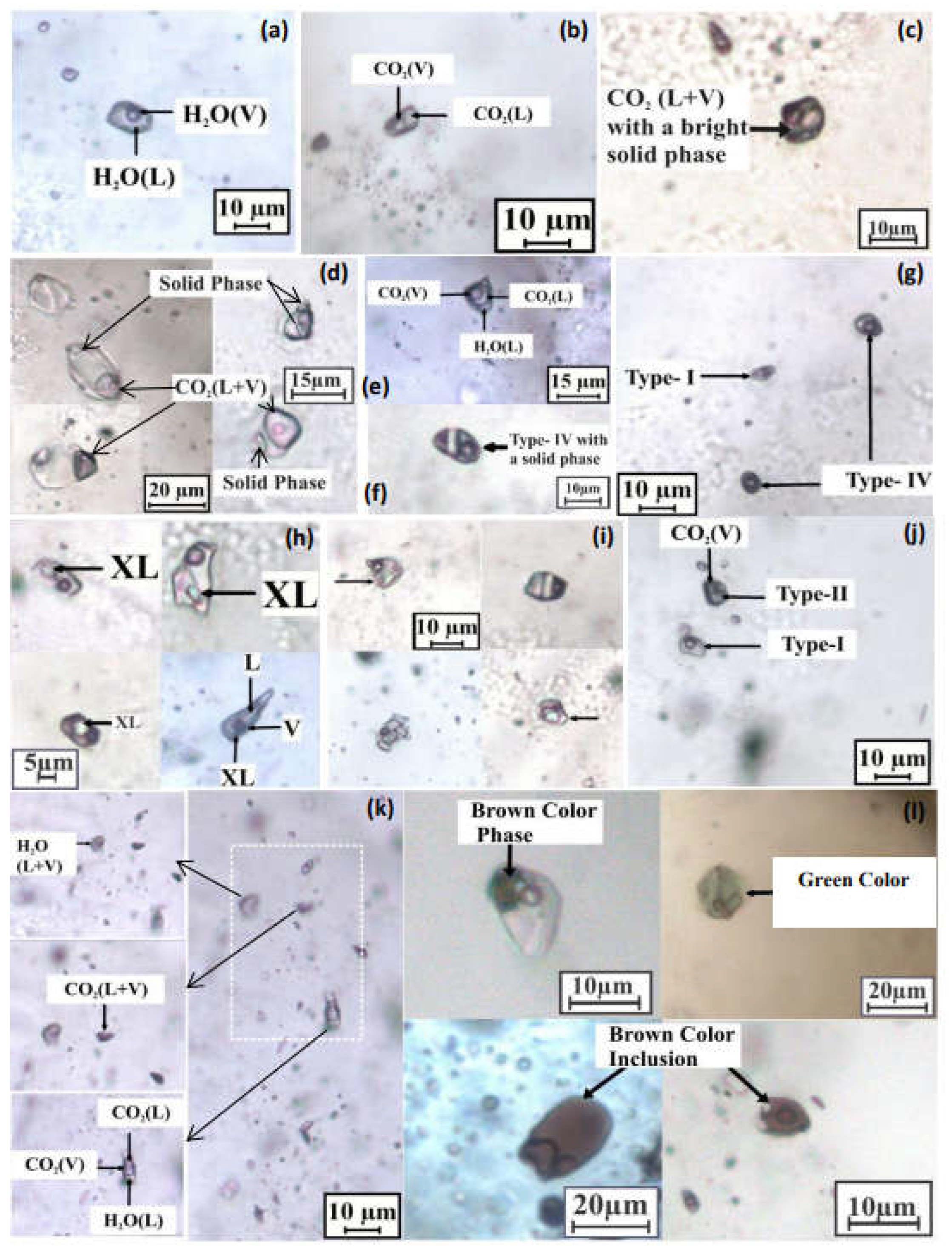

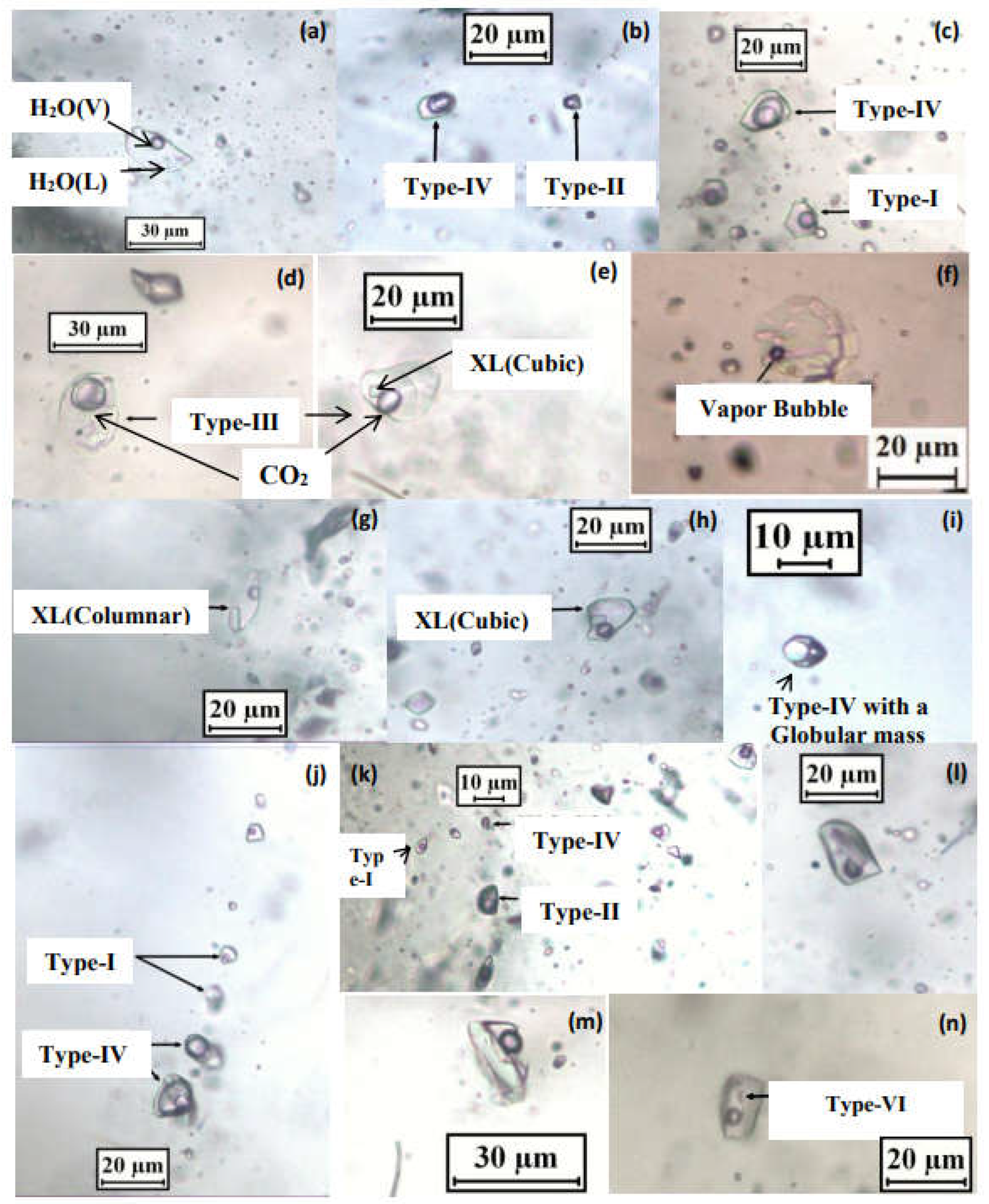

8.1. Fluid Inclusion Petrography

Types of Inclusions

Type-I: Aqueous Biphase (L+V)

Type-II: Pure Carbonic

Type-III: Mixed-Pure Carbonic

Type- IV: Aqueous Carbonic

Type-V: Aqueous Polyphase

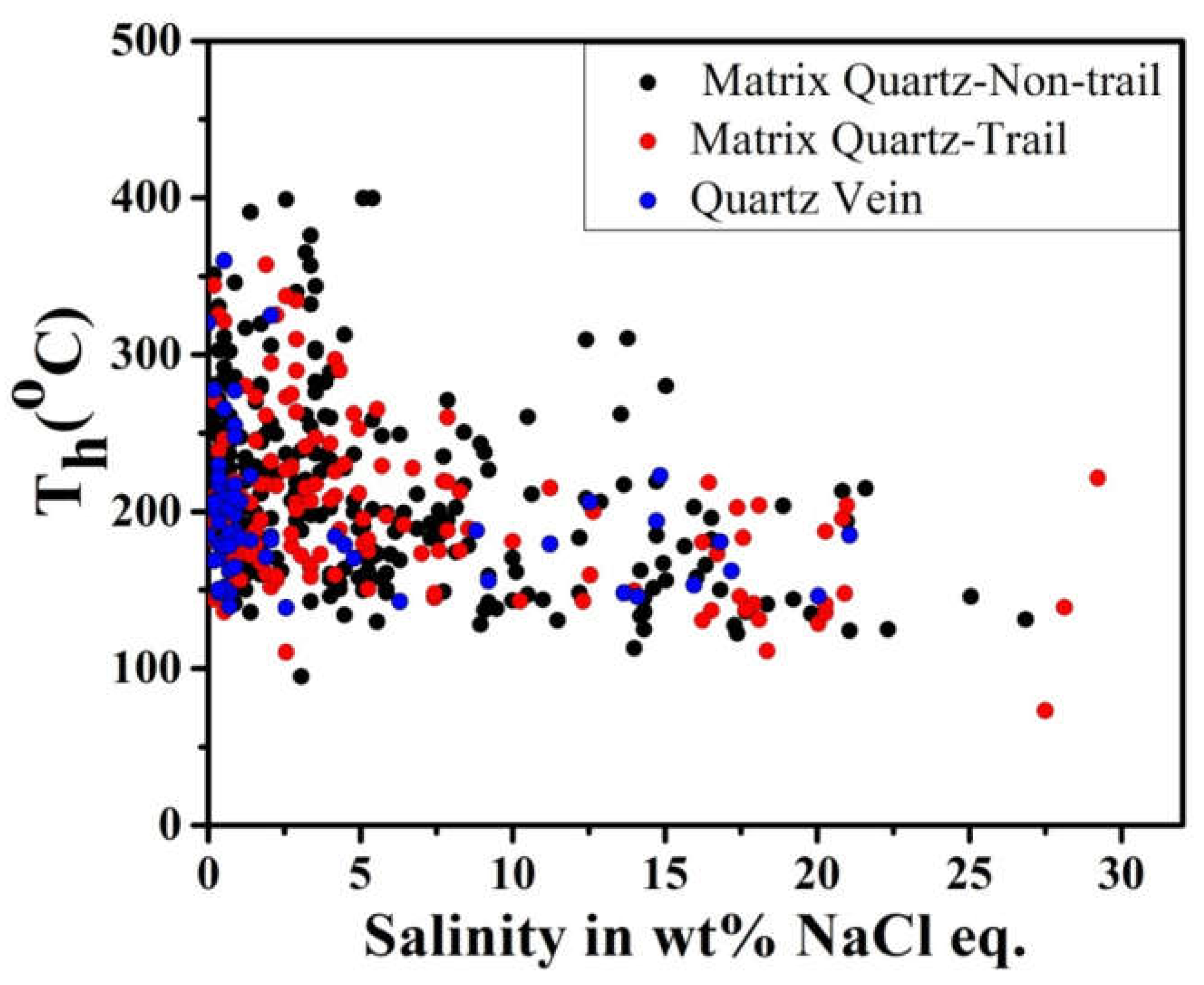

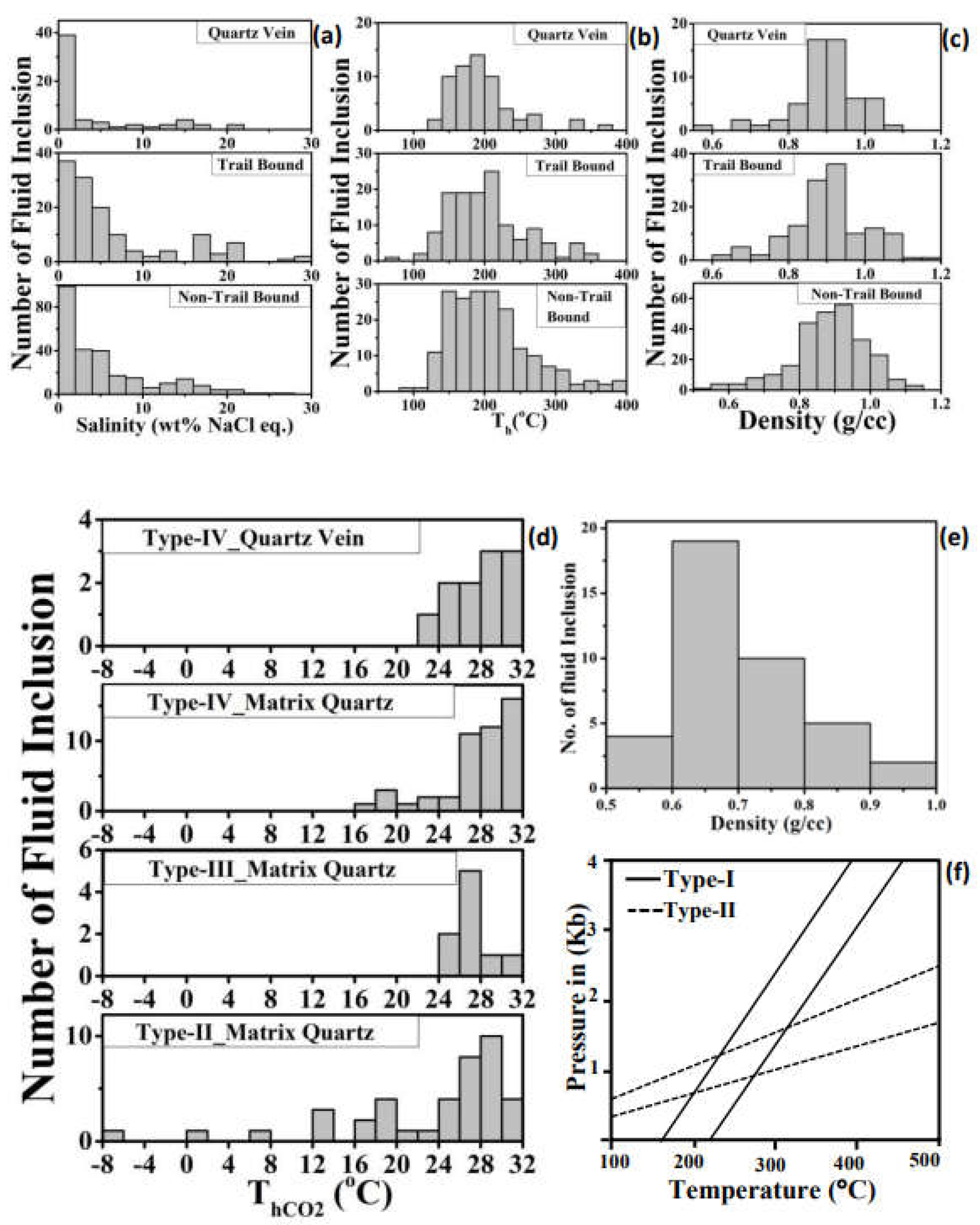

8.2. Fluid Inclusion Microthermometry

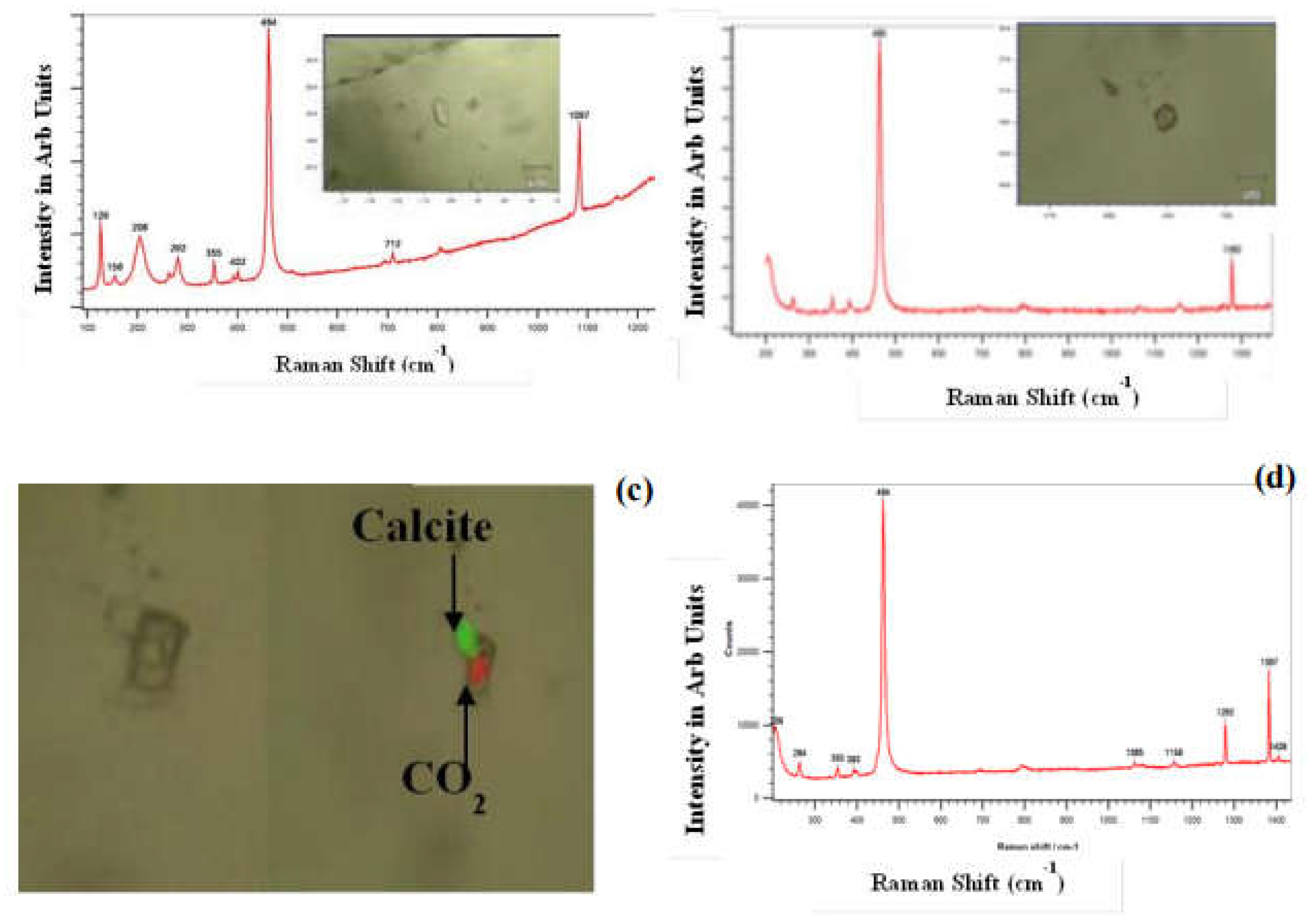

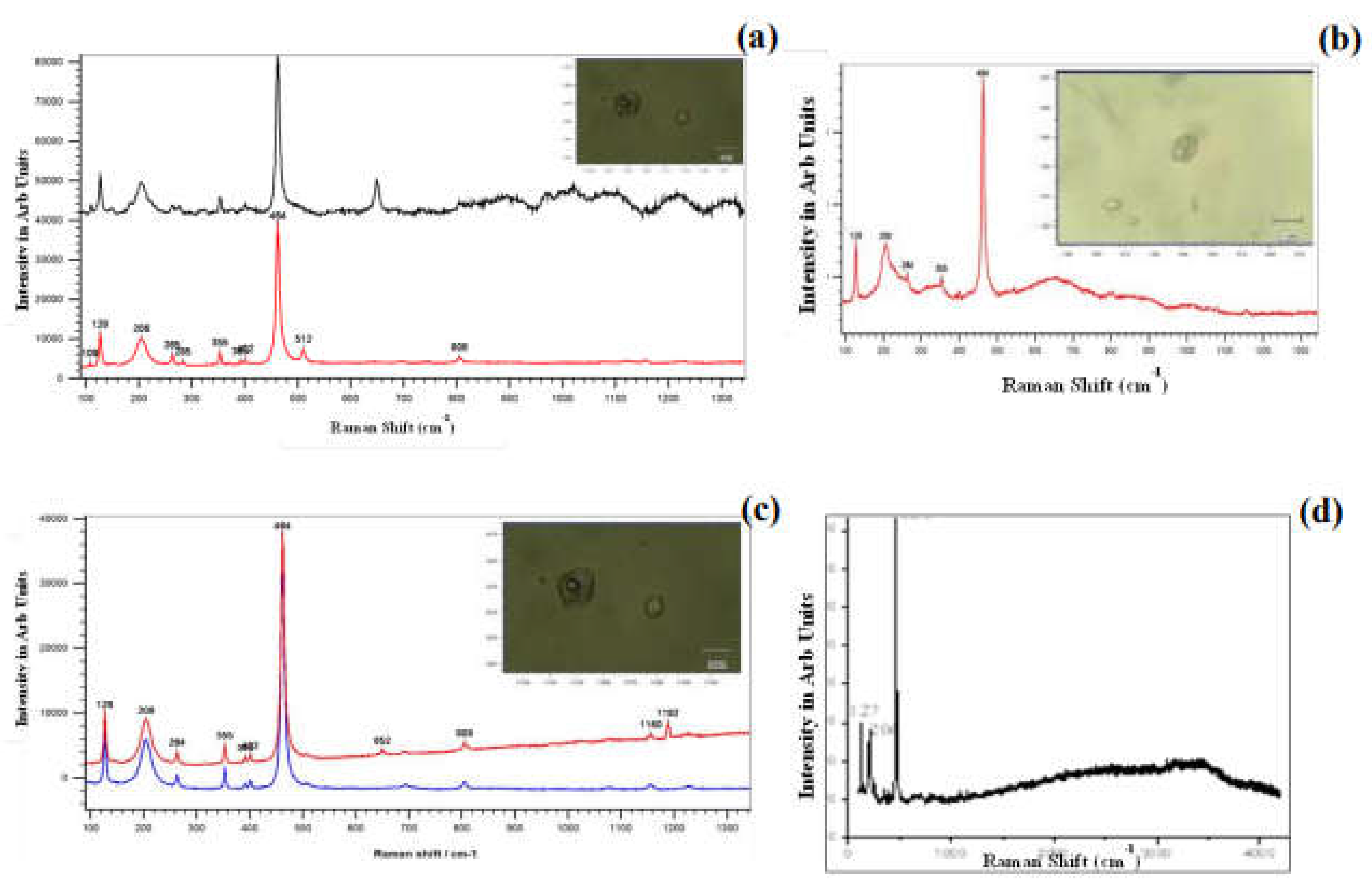

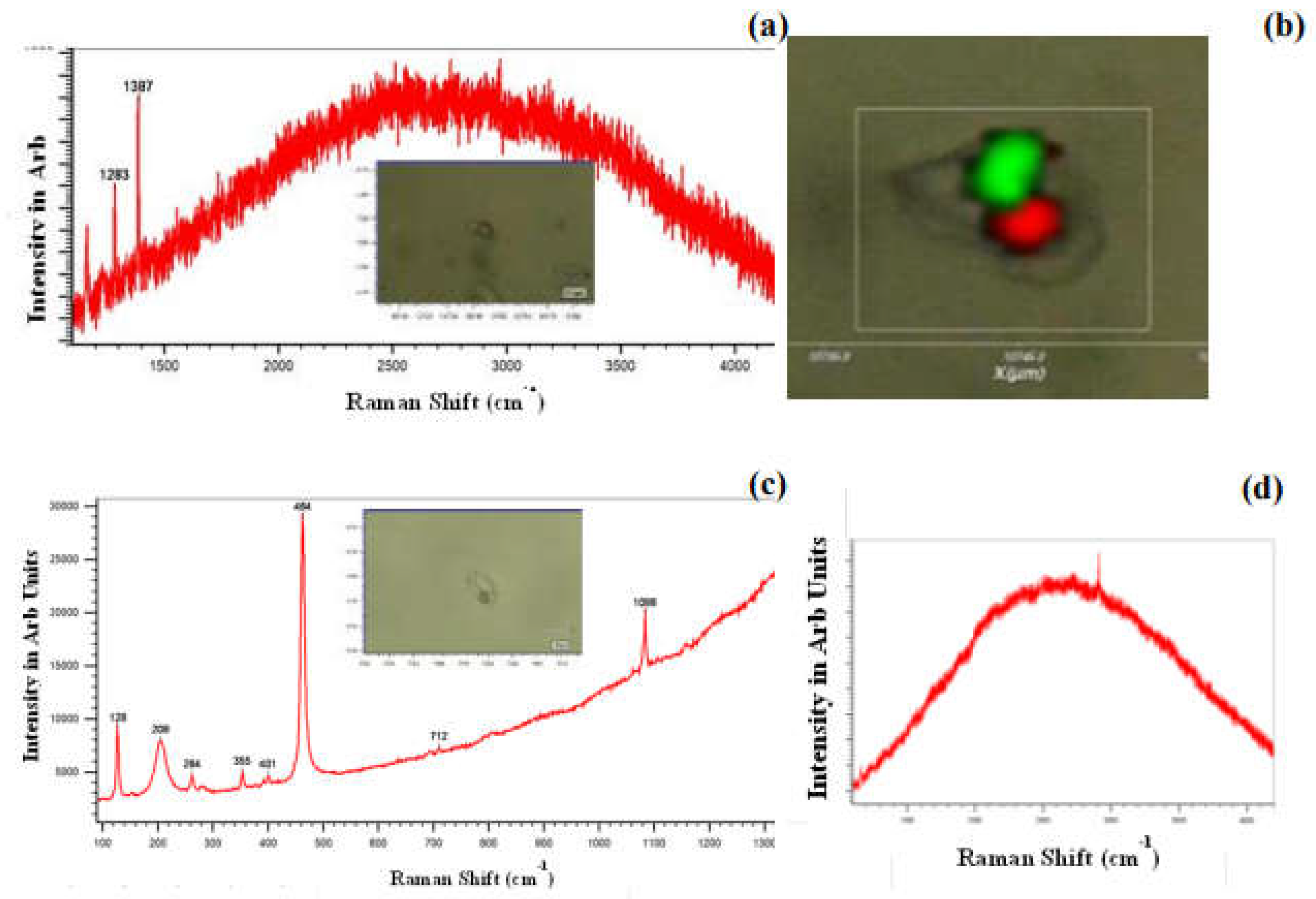

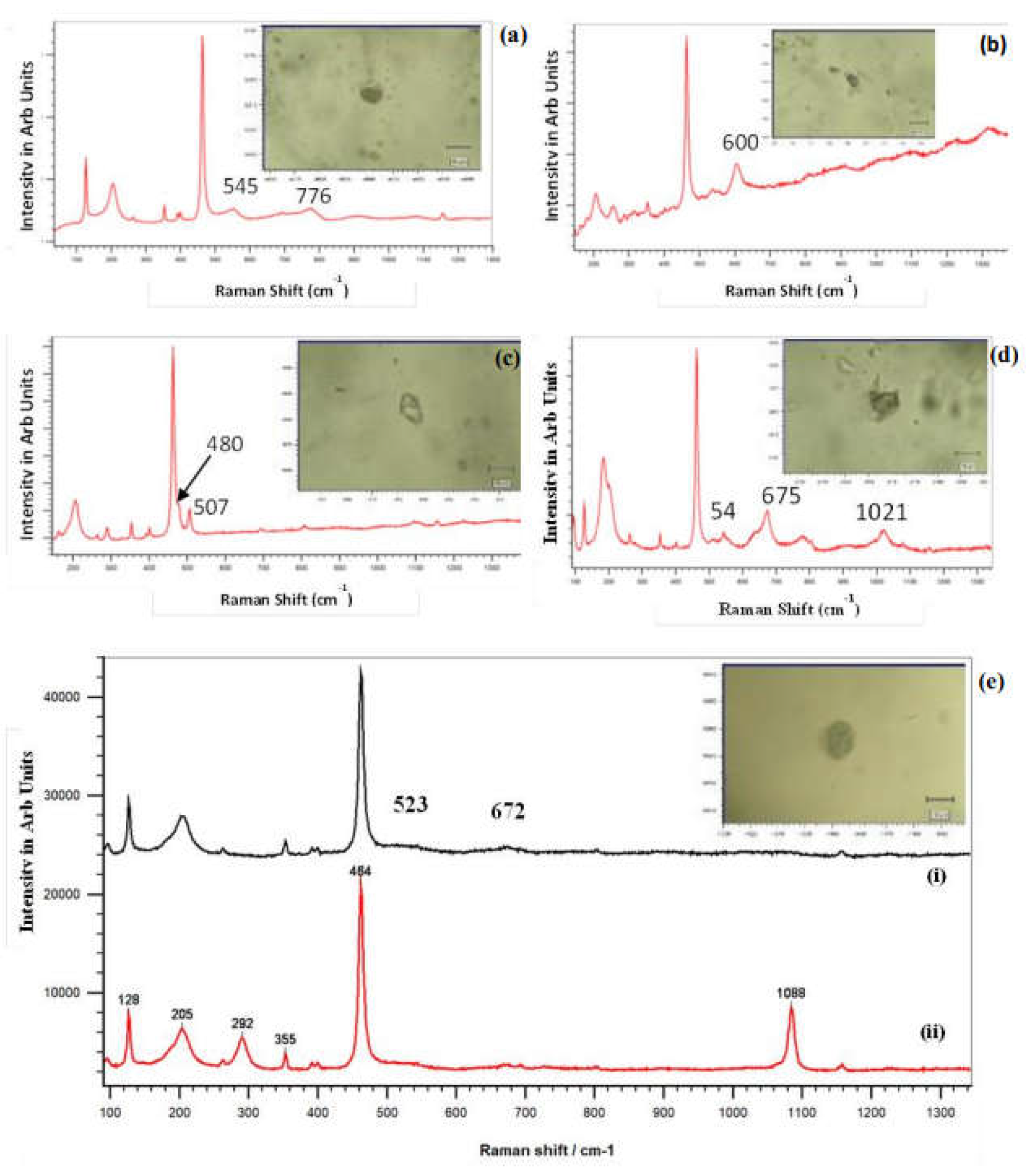

8.3. Laser Raman Microspectrometry

| Coloured Inclusion | Tfm (°C) |

Tm (°C) |

Th (°C) |

Salinity (wt% NaCl eq.) |

Density (g/cc) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Green | NA | -16.6 | 118.5 | 20.12 | 1.091 |

| Faint-greenish | NA | -0.6 | 239.2 | 1.05 | 0.82 |

| Brown | NA | -1.8 | 209.7 | 3.05 | 0.877 |

8.4. Fluid Evolution

8.5. Significance of Type V and VI Inclusions

9. Modeling of Crystallization Evolution of BG

10. Discussion

11. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Acknowledgements

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Dey, S.; Moyen, J.F. Archean granitoids of India: windows into early Earth tectonics–an introduction. Geological Society, London, Special Publications 2020, 489, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vigneresse, J.L. Control of granite emplacement by regional deformation. Tectonophysics 1995, 249, 173–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petford, N.; Cruden, A. R. , McCaffrey, K. J. W., & Vigneresse, J. L. Granite magma formation, transport and emplacement in the Earth’s crust. Nature 2000, 408, 669–673. [Google Scholar]

- Rout, D.; Panigrahi, M. K. , Mernagh, T. P., & Pati, J. K. Origin of the Paleoproterozoic “Giant Quartz Reef” System in the Bundelkhand Craton, India: Constraints from Fluid Inclusion Microthermometry, Raman Spectroscopy, and Geochemical Modelling. Lithosphere 2022, 2022 (Special 8), 3899542. [Google Scholar]

- Rahman, A.; Zainuddin, S.M. Bundelkhand granites: an example of collisionrelated Precambrian magmatism and its relevance to the evolution of the Central Indian Shield. Journal of Geology 1993, 101, 413–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mondal, M.E. A. , Goswami, J. N., Deomurari, M. P., & Sharma, K. K. Ion microprobe 207Pb/206Pb ages of zircons from the Bundelkhand massif, northern India: Implications for crustal evolution of the Bundelkhand-Aravalli protocontinent. Precambrian Research 2002, 117, 85–100. [Google Scholar]

- Menon, R.; Kumar, P. S. , Reddy, G. K., & Srinivasan, R. Radiogenic heat production of Late Archaean Bundelkhand granite and some Proterozoic gneisses and granitoids of central India. Current Science-Banglore- 2003, 85, 634–638. [Google Scholar]

- Mohan, M. R. , Singh, S. P., Santosh, M., Siddiqui, M. A., & Balaram, V. TTG suite from the Bundelkhand Craton, Central India: Geochemistry, petrogenesis and implications for Archean crustal evolution. Journal of Asian Earth Sciences 2012, 58, 38–50. [Google Scholar]

- Pati, J. K. , Panigrahi, M. K., & Chakarborty, M. Granite-hosted molybdenite mineralization from Archean Bundelkhand Craton-molybdenite characterization, host rock mineralogy, petrology, and fluid inclusion characteristics of MO-bearing quartz. Journal of Earth System Science 2014, 123, 943–958. [Google Scholar]

- Kaur, P.; Zeh, A.; Chaudhri, N.; Eliyas, N. Unravelling the record of Archaean crustal evolution of the Bundelkhand Craton, northern India using U–Pb zircon– monazite ages, Lu–Hf isotope systematics, and whole-rock geochemistry of granitoids. Precambrian Research 2016, 281, 384–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joshi, K. B. , Bhattacharjee, J., Rai, G., Halla, J., Ahmad, T., Kurhila, M., Heilimo, E., & Choudhary, A. K. The diversification of granitoids and plate tectonic implications at the archaean-Proterozoic boundary in the bundelkhand Craton, Central India. Geological Society, London, Special Publications 2017, 449, 123–157. [Google Scholar]

- Chauhan, H.; Saikia, A.; Ahmad, T. Episodic crustal growth in the Bundelkhand Craton of central India shield: Constraints from petrogenesis of the tonalite– trondhjemite–granodiorite gneisses and K-rich granites of Bundelkhand tectonic zone. Journal of Earth System Science 2018, 127, 44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sensarma, S.; Matin, A.; Paul, D.; Madhesiya, A. K. , & Sarkar, G. Evolution of a crustal-scale silicic to intermediate tectono-magmatic system: The ~ 2600–2300 Ma Bundelkhand granitoid, India. Precambrian Research 2021, 352, 105951. [Google Scholar]

- Verma, S. K. , Verma, S. P., Oliveira, E. P., Singh, V. K., & Moreno, J. A. LA- FICP-MS zircon U-Pb geochronology of granitic rocks from the central Bundelkhand greenstone complex, Bundelkhand Craton, India. Journal of Asian Earth Sciences 2016, 118, 125–137. [Google Scholar]

- Roday, P. P. , Diwan, P., & Singh, S. A kinematic model of emplacement of quartz reefs and subsequent deformation patterns in the central Indian Bundelkhand batholith. Proceedings of the Indian Academy of Sciences - Earth and PlanetarySciences 1995, 104, 465–488. [Google Scholar]

- Mondal, M.E. A. , Sharma, K. K., Rahman, A., & Goswami, J. N. Ion microprobe 207Pb/206Pb zircon ages for gneiss-granitoid rocks from Bundelkhand massif: Evidence for Archaean components. Current Science 1998, 70–75. [Google Scholar]

- Pati, J.K. Study of granitoid mylonites and reef/vein quartz in parts of Bundelkhand Granitoid Complex (BGC). Rec. Geol. Surv. India 1999, 131, 95–96. [Google Scholar]

- Slabunov, A. I. , & Singh, V. K. Giant quartz veins of the Bundelkhand craton, Indian shield: new geological data and U-Th-Pb age. Minerals 2022, 12, 168. [Google Scholar]

- Pati, J. K. , Patel, S. C., Pruseth, K. L., Malviya, V. P., Arima, M., Raju, S., Pati, P., & Prakash, K. Geology and geochemistry of giant quartz veins from the Bundelkhand Craton, central India and their implications. Journal of Earth System Science 2007, 116, 497–510. [Google Scholar]

- Panigrahi, M.K. and Acharya, S. S. A Microsoft EXCEL 2007 and MS Visual BASIC Macro Based Software Package for Computation of Density and Isochores of Fluid Inclusions. Proceedings ACROFI-III and TBG-XIV Novosibirsk. 2010, 160–161. [Google Scholar]

- Boudreau, A.E. PELE-a version of the MELTS software program for the PC platform. Computers and Geosciences 1999, 25, 201–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basu, A.K. Role of the Bundelkhand Granite Massif and the Son-Narmada megafault in Precambrian crustal evolution and tectonism in Central and Western India. Journal of the Geological Society of India 2007, 70, 745–770. [Google Scholar]

- Pati, J.K. Evolution of Bundelkhand Craton. Episodes Journal of International Geoscience 2020, 43, 69–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Worden, R.H., ; ; Walker, F.D.L.; Parsons, I.; Brown, W.L. Development of microporosity, diffusion channels and deuteric coarsening in perthitic alkali feldspars; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Kroll, H.; Evangelakakis, C.; Voll, G. Two-feldspar geothermometry: a review and revision for slowly cooled rocks. Contributions to Mineralogy and Petrology 1993, 114, 510–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Otten, M.T. The origin of brown hornblende in the Artfjället gabbro and dolerites. Contributions to Mineralogy and Petrology 1984, 86, 189–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fleet, M.E.; Barnett, R.L. Al iv/Al vi partitioning in calciferous amphiboles from the Frood Mine, Sudbury, Ontario. Can. Mineral. 1978, 16, 527–532. [Google Scholar]

- Yavuz, F. WinAmphcal: A Windows program for the IMA-04 amphibole classification. Geochemistry, Geophysics, Geosystems 2007, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deer, W.A.; Howie, R.A.; Zussman, J. An introduction of the rock-forming minerals; London: Longman Group Limited, 1979. [Google Scholar]

- Yavuz, F. Evaluating micas in petrologic and metallogenic aspect: Part IIApplications using the computer program Mica+. Computers and Geosciences 2003, 29, 1215–1228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nachit, H.; Razafimahefa, N.; Stussi, J.M. & Carron, J. P. Composition chimique des biotites et typologie magmatique des granitoids. Comtes Rendus Hebdomadaires de I’ Academie des Sciences 1985, 301, 813–818. [Google Scholar]

- de Alquerque, C.A.R. Geochemistry of biotite from granitic rocks, northern Portugal. Geochimica et Cosmochimica Acta 1973, 37, 1779–1802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdel-Rahman, A.F.M. Nature of biotites from alkaline, calc-alkaline, and peraluminous magmas. Journal of Petrology 1994, 35, 525–541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verdecchia, S. O. , Collo, G., Zandomeni, P. S., Wunderlin, C., & Fehrmann, M. Crystallochemical indexes and geothermobarometric calculations as a multiproxy approach to P-T condition of the low-grade metamorphism: The case of the San Luis Formation, Eastern Sierras Pampeanas of Argentina. Lithos 2019, 324-325, 385–401. [Google Scholar]

- Speer, J.A. Micas in igneous rocks. In: Bailey, S.W. (ed), Reviews in Mineralogy,Micas. Mineralogical Society of America 1984, 229–356. [Google Scholar]

- Ketcham, R.A. Technical Note: Calculation of stoichiometry from EMP data for apatite and other phases with mixing on monovalent anion sites. American Mineralogist 2015, 100, 1620–1623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piccoli, P.M. and Candela, P. A. Apatite in Igneous Systems. In: Phosphates- Geochemical, Geobiological and Materials Importance. Rev. Min. Geochem. 2002, 48, 255–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oberti, R.; Smith, D.C.; Rossi, G.; Caucia, F. The crystal-chemistry of high-aluminum titanites. European Journal of Mineralogy 1981, 777–792. [Google Scholar]

- Yavuz, F.; Kumral, M.; Karakaya, N.; Karakaya, M. T. , & Yildirim, D. K. A Windows program for chlorite calculation and classification. Computers andGeosciences 2015, 81, 101–113. [Google Scholar]

- Ciesielczuk, J.M. Chlorite of hydrothermal origin formed in the Strzelin and Borów granites (Fore-Sudetic Block, Poland). Geological Quarterly 2012, 56, 333–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tulloch, A.J. Secondary Ca–Al silicates as low-grade alteration products of granitoid biotite. Contributions to Mineralogy and Petrology 1979, 69, 105–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evans, B.W.; Vance, J.A. Epidote phenocrysts in dacitic dikes, Boulder county, Colorado. Contributions to Mineralogy and Petrology 1987, 96, 178–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sial, A. N. , Toselli, A. J., Saavedra, J., Parada, M. A., & Ferreira, V. P. Emplacement, petrological and magnetic susceptibility characteristics of diverse magmatic epidote-bearing granitoid rocks in Brazil, Argentina and Chile. Lithos 1999, 46, 367–392. [Google Scholar]

- Galindo, A.C.; Dall'Agnol, R.; Lafon, J.M.; Teixeira, N.P. Evolution of Brasiliano-age granitoid types in a shear-zone environment, Umarizal–Caraubas region, Rio Grande do Norte, northeast Brazil. Journal of South American Earth Sciences 1995, 8, 79–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sial, A. N. , Vasconcelos, P. M., Ferreira, V. P., Pessoa, R. R., Brasilino, R. G., & MoraisNeto, J. M. Geochronological and mineralogical constraints on depth of emplacement and ascencion rates of epidote-bearing magmas from northeastern Brazil. Lithos 2008, 105, 225–238. [Google Scholar]

- Zen, E.-A.n.; Hammarstrom, J.M. Magmatic epidote and its petrologic significance. Geology 1984, 12, 515–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brasilino, R. G. , Sial, A. N., Ferreira, V. P., & Pimentel, M. M. Bulk rock and mineral chemistries and ascent rates of high-K calc-alkalic epidote-bearing magmas, Northeastern Brazil. Lithos 2011, 127, 441–454. [Google Scholar]

- Wright, W.I. The composition and occurrence of garnets. American Mineralogist:Journal of Earth and Planetary Materials 1938, 23, 436–449. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, D.J. From slab to sinter: The magmatic-hydrothermal system of Savo Volcano, Solomon Islands.(unpublished). Ph. D. thesis, University of Leicester, 2008; 261p. [Google Scholar]

- Haggerty, S.E. Oxidation of opaque mineral oxides in basalts. In Oxide Minerals. Reviews in Mineralogy; Rumble, D., III, Ed.; 1976. [Google Scholar]

- Benisek, A.; Kroll, H.; Cemic, L. New developments in two-feldspar thermometry. American Mineralogist 2004, 89, 1496–1504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmidt, M.W. Amphibole composition in tonalite as a function of pressure: an experimental calibration of the Al-in-hornblende barometer. Contributions to Mineralogy and Petrology 1992, 110, 304–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, M. C. , & Rutherford, M. J. Experimental calibration of the aluminum-inhornblende geobarometer with application of Long Valley caldera (California) volcanic rocks. Geology 1989, 17, 837–841. [Google Scholar]

- Ague, J.J. Thermodynamic calculation of emplacement pressures for batholithic rocks, California: Implications for the aluminum-in-hornblende barometer. Geology 1997, 25, 563–566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, J. L. , & Smith, D. R. The effects of temperature and fO₂ on the Al-inhornblende barometer. American Mineralogist 1995, 80, 549–559. [Google Scholar]

- Putirka, K. Amphibole thermometers and barometers for igneous systems and some implications for eruption mechanisms of felsic magmas at arc volcanoes. American Mineralogist 2016, 101, 841–858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Otten, M.T. The origin of brown hornblende in the Artfjället gabbro and dolerites. Contributions to Mineralogy and Petrology 1984, 86, 189–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blundy, J. D. , & Holland, T. J. B. Calcic amphibole equilibria and a new amphibole-plagioclase geothermometer. Contributions to Mineralogy and Petrology 1990, 104, 208–224. [Google Scholar]

- Holland, T.; Blundy, J. Non-ideal interactions in calcic amphiboles and their bearing on amphibole-plagioclase thermometry. Contributions to Mineralogy and Petrology 1994, 116, 433–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, J. L. , Barth, A. P., Wooden, J. L., & Mazdab, F. Thermometers and thermobarometers in granitic systems. Reviews in Mineralogy and Geochemistry 2008, 69, 121–142. [Google Scholar]

- Henry, D. J. , Guidotti, C. V., & Thomson, J. A. The Ti-saturation surface for low to- medium pressure metapelitic biotites: Implications for geothermometry and Tisubstitution mechanisms. American Mineralogist 2005, 90, 316–328. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, C.; Sverjensky, D.A. F-Cl-OH partitioning between biotite and apatite. Geochimica et Cosmochimica Acta 1992, 56, 3435–3467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bath, A. B. , Walshe, J. L., Cloutier, J., Verrall, M., Cleverley, J. S., Pownceby, M. I., Macrae, C. M., Wilson, N. C., Tunjic, J., Nortje, G. S., & Robinson, P. Biotite and apatite as tools for tracking pathways of oxidized fluids in the Archean East Repulse gold deposit, Australia. Economic Geology 2013, 108, 667–690. [Google Scholar]

- Bird, D. K. , & Helgeson, H. C. Chemical interaction of aqueous solutions with epidote – feldspar mineral assemblages in geologic systems. I: Thermodynamic analysis of phase relations in the system CaO-FeO-Fe2O3-Al2O3-SiO2-H2O-CO2. Am. J. Sci. 1980, 280, 907–941. [Google Scholar]

- Cathelineau, M. Cation site occupancy in chlorites and illites as a function of temperature. Clay Minerals 1988, 23, 471–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jowett, E.C. Fitting iron and magnesium into the hydrothermal chlorite geothermometer. GAC/MAC/SEG Joint Annual Meeting, Program with Abstracts 16. Toronto, 27-29 May 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Xie, X.; Byerly, G. R. , & Ferrell, R. E. IIb trioctahedral chlorite from the Barberton greenstone belt: Crystal structure and rock composition constraints with implications to geothermometry. Contributions to Mineralogy and Petrology 1997, 126, 275–291. [Google Scholar]

- Bourdelle, F.; Parra, T.; Beyssac, O.; Chopin, C.; Vidal, O. Clay minerals as geothermometer: A comparative study based on high spatial resolution analyses of illite and chlorite in Gulf Coast sandstones (Texas, U.S.A.). American Mineralogist 2013, 98, 914–926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lanari, P.; Wagner, T.; Vidal, O. A thermodynamic model for di-trioctahedral chlorite from experimental and natural data in the system MgO-FeO-Al2O3-SiO2-H2O: Applications to P-T sections and geothermometry. Contributions to Mineralogy and Petrology 2014, 167, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inoue, A.; Inoué, S.; Utada, M. Application of chlorite thermometry to estimation of formation temperature and redox conditions. Clay Minerals 2018, 53, 143–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wones, D.R. & Eugster, H. P. Stability of biotite: experiment, theory, and application. American Mineralogist: Journal of Earth and Planetary Materials 1965, 50, 1228–1272. [Google Scholar]

- Miles, A. J. , Graham, C. M., Hawkesworth, C. J., Gillespie, M. R., Hinton, R. W., & Bromiley, G. D. Apatite: A new redox proxy for silicic magmas? Geochimica et Cosmochimica Acta 2014, 132, 101–119. [Google Scholar]

- Wones, D.R. Significance of the assemblage titanite+magneite+quartz in granitic rocks. Am. Mineral. 1989, 74, 744–749. [Google Scholar]

- Holtz F, Johannes W, Tamic N, & Behrens H (). Maximum and minimum water contents of granitic melts generated in the crust: A reevaluation and implications. Lithos 2001, 56, 1–14.

- Teiber, H.; Marks, M.A. W. , Wenzel, T., Siebel, W., Altherr, R., & Markl, G. The distribution of halogens (F, Cl, Br) in granitoid rocks. Chemical Geology 2014, 374-375, 92–109. [Google Scholar]

- Słaby, E.; Domańska-Siuda, J. Origin and evolution of volatiles in the Central Europe late Variscan granitoids, using the example of the Strzegom-Sobótka Massif, SW Poland. Mineralogy and Petrology 2019, 113, 119–134. [Google Scholar]

- Munoz, J.L. F-OH and Cl-OH exchange in micas with applications to hydrothermal ore deposits. Reviews in Mineralogy and Geochemistry 1984, 13, 469–493. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, C.; Sverjensky, D.A. Partitioning of F-Cl-OH between minerals and hydrothermal fluids. Geochimica et Cosmochimica Acta 1991, 55, 1837–1858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loferski, P. J. , & Ayuso, R. A. Petrography and mineral chemistry of the composite Deboullie pluton, northern Maine, U.S.A.: Implications for the genesis of Cu-Mo mineralization. Chemical Geology 1995, 123, 89–105. [Google Scholar]

- Parsapoor, A.; Khalili, M.; Tepley, F.; Maghami, M. Mineral chemistry and isotopic composition of magmatic, re-equilibrated and hydrothermal biotites from Darreh-Zar porphyry copper deposit, Kerman (Southeast of Iran). Ore GeologyReviews 2015, 66, 200–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munoz, J.L. Calculation of HF and HCl fugacities from biotite compositions: revised equations. Geological Society of America, Abstracts with Programs 1992, 26, 221. [Google Scholar]

- Tarantola, A.; Diamond, L.W. & Stu¨nitz H. Modification of fluid inclusions in quartz by deviatoric stress I: experimentally induced changes in inclusion shapes and microstructures. Contributions to Mineraloy and Petrology 2010, 160, 825–843. [Google Scholar]

- Chi, G. and Lu, H. Validation and representation of fluid inclusion microthermometric data using the fluid inclusion assemblage (FIA) concept. Acta Petrologica Sinica 2008, 9, 1945–1953. [Google Scholar]

- Chi, G.; Diamond, L.W.L. H. , Lai, J. and Chu, H. Common problems and pitfalls in fluid inclusion study: a review and discussion. Minerals 2021, 11, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shepherd, T.J.; Rankin, A.H.; Alderton, D.H.M. A practical guide to fluid inclusion studies; Glasgow: Blackie, 1985; 239 p. [Google Scholar]

- Bowers, T.S. Pressure-volume-temperature properties of H2O-CO2 fluids. Rock Physics and Phase Relations: A Handbook of Physical Constants, AGU Ref. Shelf 1995, 3, 45–72. [Google Scholar]

- Parry, W.T. Estimation of X CO2, P, and fluid inclusion volume from fluid inclusion temperature measurements in the system NaCl-CO2 H2O. Economic Geology 1986, 81, 1009–1013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panigrahi, M. K. , & Mookherjee, A. The Malanjkhand copper (+ molybdenum) deposit, India: Mineralization from a low-temperature ore-fluid of granitoid affiliation. Mineralium Deposita 1997, 32, 133–148. [Google Scholar]

- Mernagh, T.P. & Wilde, A.R. The use of the laser Raman microprobe for the determination of salinity in fluid inclusions. Geochimica et Cosmochimica Acta 1989, 53, 765–771. [Google Scholar]

- Dubessy, J.; Lhomme, T.; Boiron, M.-C. &Rull, F. Determination of chlorinity in aqueous fluids using Raman spectroscopy of the stretching band of water at room temperature: Application to fluid inclusions. Applied Spectroscopy 2002, 56, 99–106. [Google Scholar]

- Frezzotti, M. L. , Tecce, F., & Casagli, A. Raman spectroscopy for fluid inclusion analysis. Journal of Geochemical Exploration 2012, 112, 1–20. [Google Scholar]

- Roedder, E. & Bodnar, R. J. Geologic pressure determination from fluid inclusion studies. Annual Reviews of Earth and Planetary Sciences 1980, 8, 263–301. [Google Scholar]

- Wilkinson, J. J. , Nolan, J., & Rankin, A. H. Silicothermal fluid: A novel medium for mass transport in the lithosphere. Geology 1996, 24, 1059–1062. [Google Scholar]

- Thomas, R.; Davidson, P. Evidence of a water-rich silica gel state during the formation of a simple pegmatite. Mineralogical Magazine 2012, 76, 2785–2801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morey, G. W. , & Fleischer, M. Equilibrium between vapor and liquid phases in the system CO2-H2O-K2O-SiO2. Geological Society of America Bulletin 1940, 51, 1035–1058. [Google Scholar]

- Puziewicz, J.; Johannes, W. Experimental study of a biotite-bearing granitic system under water-saturated and water-undersaturated conditions. Contributions toMineralogy and Petrology 1990, 104, 397–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naney, M.T. Phase equilibria of rock-forming ferromagnesian silicates in granitic systems. American Journal of Science 1983, 283(10), 993–1033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Webster, J. D. , Tappen, C. M., & Mandeville, C. W. Partitioning behavior of chlorine and fluorine in the system apatite–melt–fluid. II: Felsic silicate systems at 200 MPa. Geochimica et Cosmochimica Acta 2009, 73, 559–581. [Google Scholar]

- Słaby, E.; Martin, H.; Hamada, M.; Śmigielski, M.; Domonik, A.; Götze, J.; Hoefs, J.; Hałas, S.; Simon, K.; Devidal, J.L.; Moyen, J.F.; Jayananda, M. Evidence in Archaean alkali feldspar megacrysts for high-temperature interaction with mantle fluids. Journal of Petrology 2012, 53, 67–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bath, A. B. , Walshe, J. L., Cloutier, J., Verrall, M., Cleverley, J. S., Pownceby, M. I., Macrae, C. M., Wilson, N. C., Tunjic, J., Nortje, G. S., & Robinson, P. Biotite and apatite as tools for tracking pathways of oxidized fluids in the Archean East Repulse gold deposit, Australia. Economic Geology 2013, 108, 667–690. [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt, M. W. , & Poli, S. Magmatic epidote. Reviews in Mineralogy and Geochemistry 2004, 56, 399–430. [Google Scholar]

- Brandon, A. D. , Creaser, R. A., & Chacko, T. Constraints on rates of granitic magma transport from epidote dissolution kinetics. Science 1996, 271, 1845–1848. [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt, M. W. , & Thompson, A. B. Epidote in calc-alkaline magmas: An experimental study of stability, phase relationships, and the role of epidote in magmatic evolution. American Mineralogist.

- Sensarma, S.; Matin, A.; Paul, D.; Patra, A.; Madhesiya, A. K. , & Sarkar, G. Reddening of ~2.5 Ga granitoid by high-temperature fluid linked to mafic dyke swarm in the Bundelkhand Craton, north central India. Geological Journal 2018, 53, 1338–1353. [Google Scholar]

- Słaby, E.; Domańska-Siuda, J. Origin and evolution of volatiles in the Central Europe late Variscan granitoids, using the example of the Strzegom-Sobótka Massif, SW Poland. Mineralogy and Petrology 2019, 113, 119–134. [Google Scholar]

- Bhattacharya, S. Granitic magmatism late-stage fluid activity vis-à-vis gold mineralization in schist belts in parts of the Eastern Dharwar Craton India (unpublished) Ph, D. Thesis, Indian Institute of Technology, Kharagpur 2014, 197p.

- Putnis, A.; Hinrichs, R.; Putnis, C. V. , Golla-Schindler, U., & Collins, L. G. Hematite in porous red-clouded feldspars: Evidence of large-scale crustal fluid-rock interaction. Lithos.

- Plümper, O.; Putnis, A. The complex hydrothermal history of granitic rocks: Multiple feldspar replacement reactions under subsolidus conditions. Journal of Petrology 2009, 50, 967–987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colleps, C. L. , McKenzie, N. R., Guenthner, W. R., Sharma, M., & Stockli, D. F. Low-temperature thermochronometric insight into the long-term burial and erosional evolution of the Bundelkhand Craton of central India. European Geosciences Union General Assembly, Vienna, Austria. 2019, 21, 12108. [Google Scholar]

- Bhattacharya, S.; Panigrahi, M.K. Heterogeneity in fluid characteristics in the Ramagiri–Penakacherla sector of the Eastern Dharwar Craton: implications to gold metallogeny. Russian Geology and Geophysics 2011, 52, 1436–1447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allan, M. M. , & Yardley, B. W. D. Tracking meteoric infiltration into a magmatic hydrothermal system: A cathodoluminescence, oxygen isotope and trace element study of quartz from Mt. Leyshon, Australia. Chemical Geology 2007, 240, 343–360. [Google Scholar]

- Reed, M.; Rusk, B.; Palandri, J. The Butte magmatic-hydrothermal system: One fluid yields all alteration and veins. Economic Geology 2013, 108, 1379–1396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).