Submitted:

31 March 2025

Posted:

31 March 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

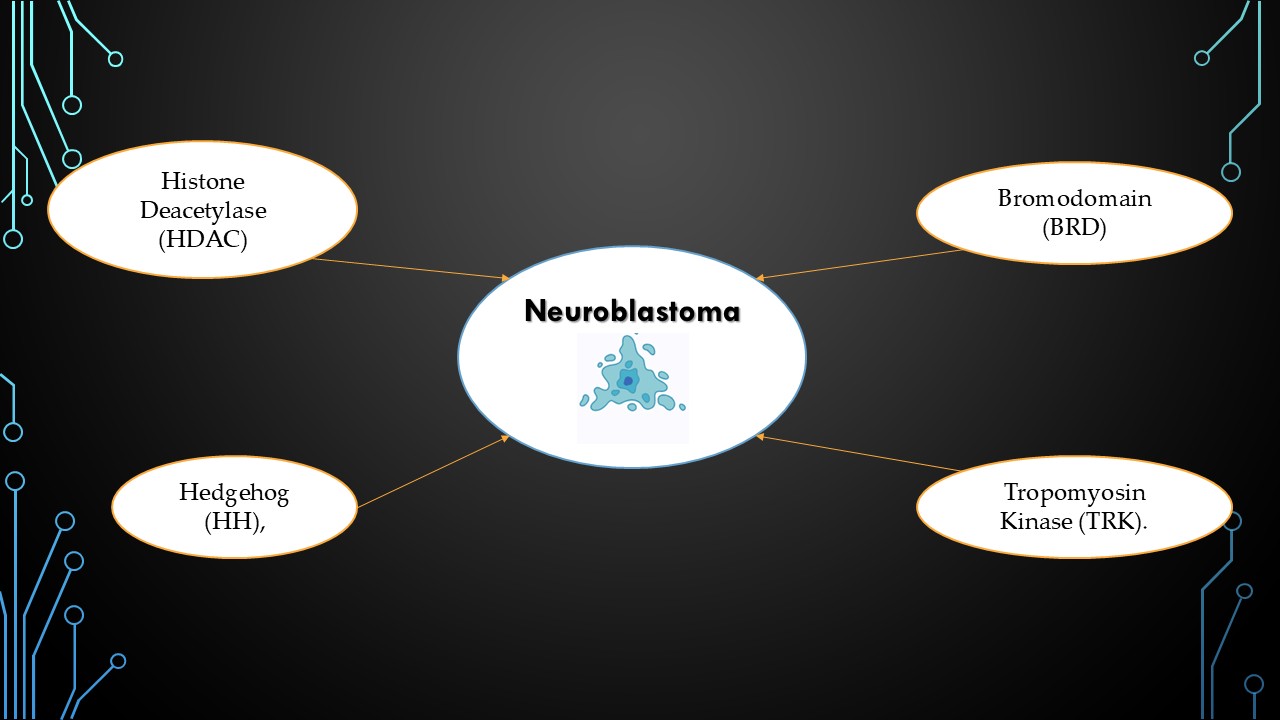

1.1. Selected Targets and Why?

- 1)

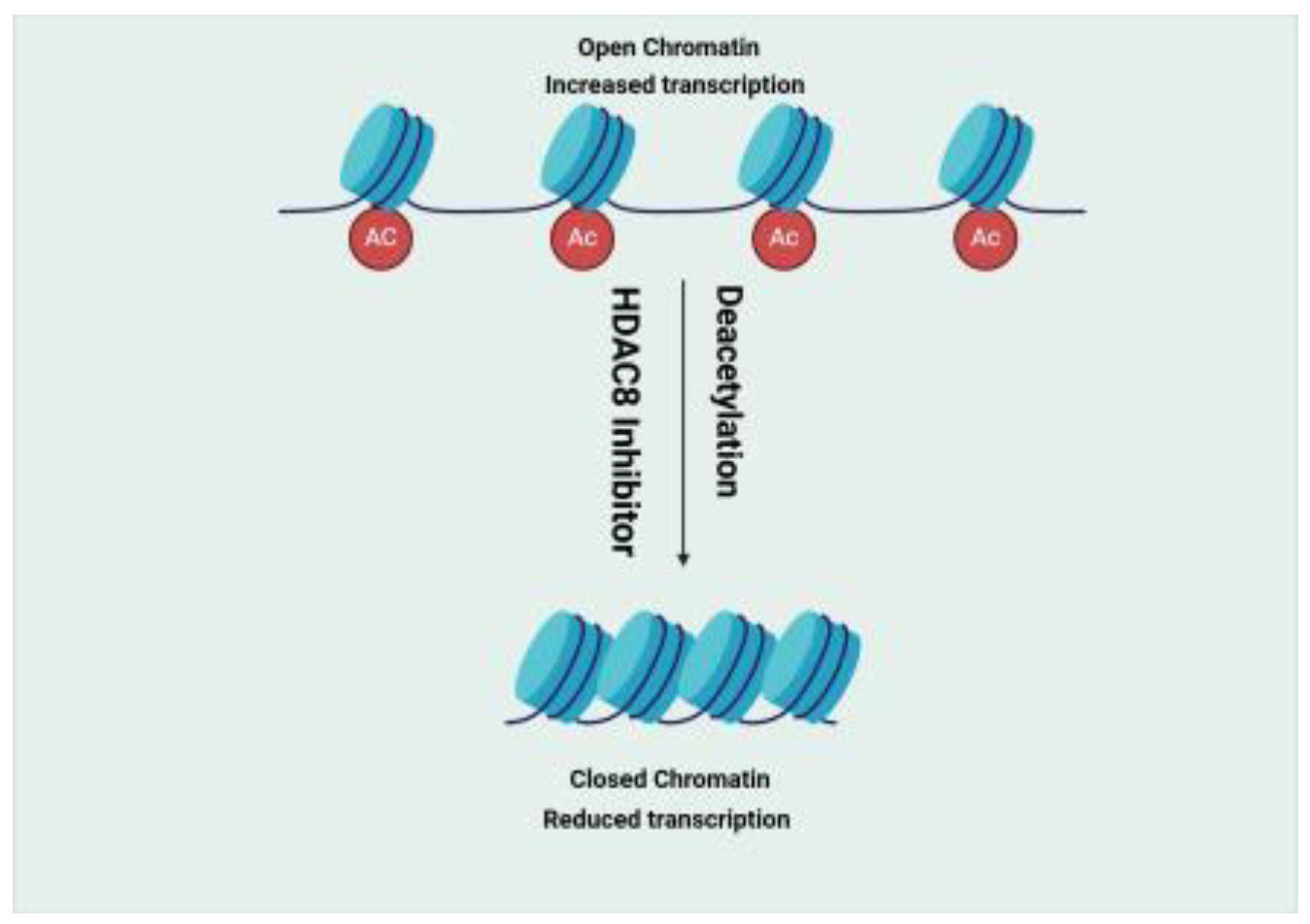

- Histone Deacetylase (HDAC)

- 2)

- Bromodomain (BRD)

- 3)

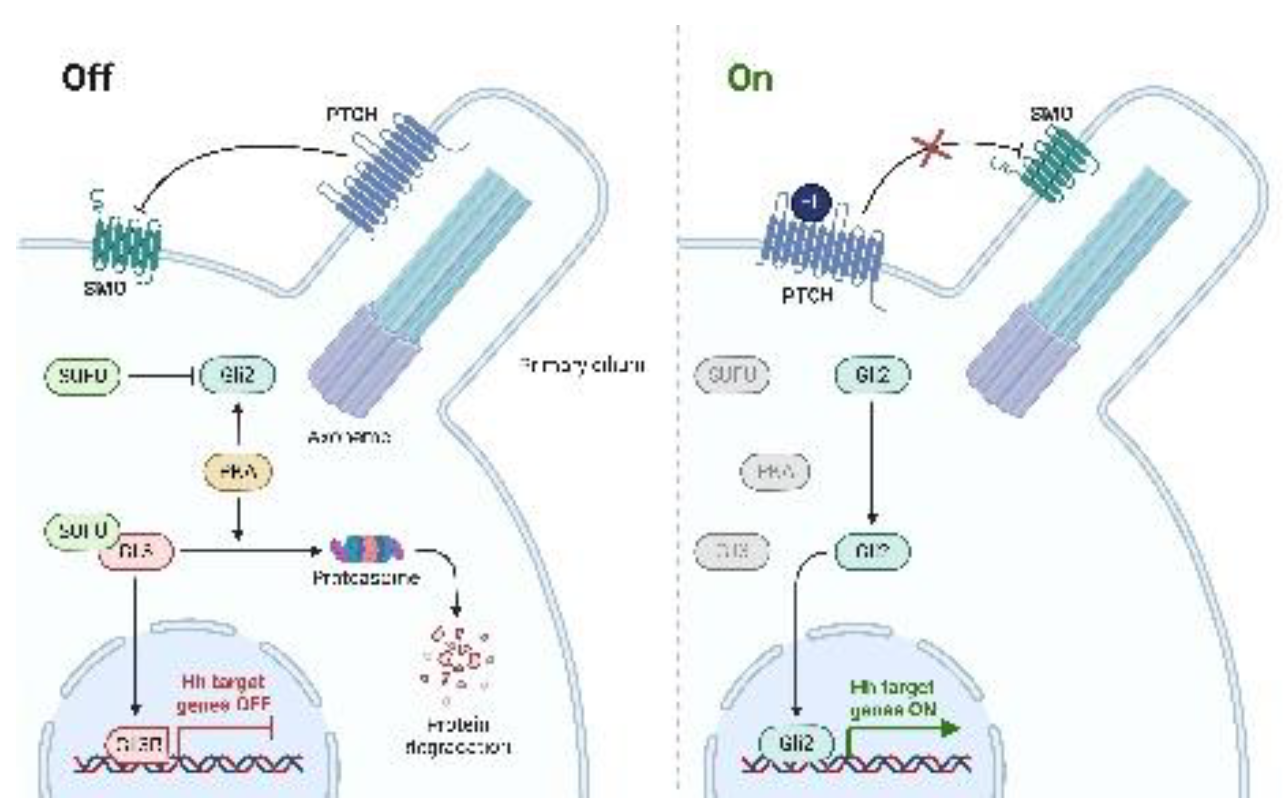

- Hedgehog (HH)

- 4)

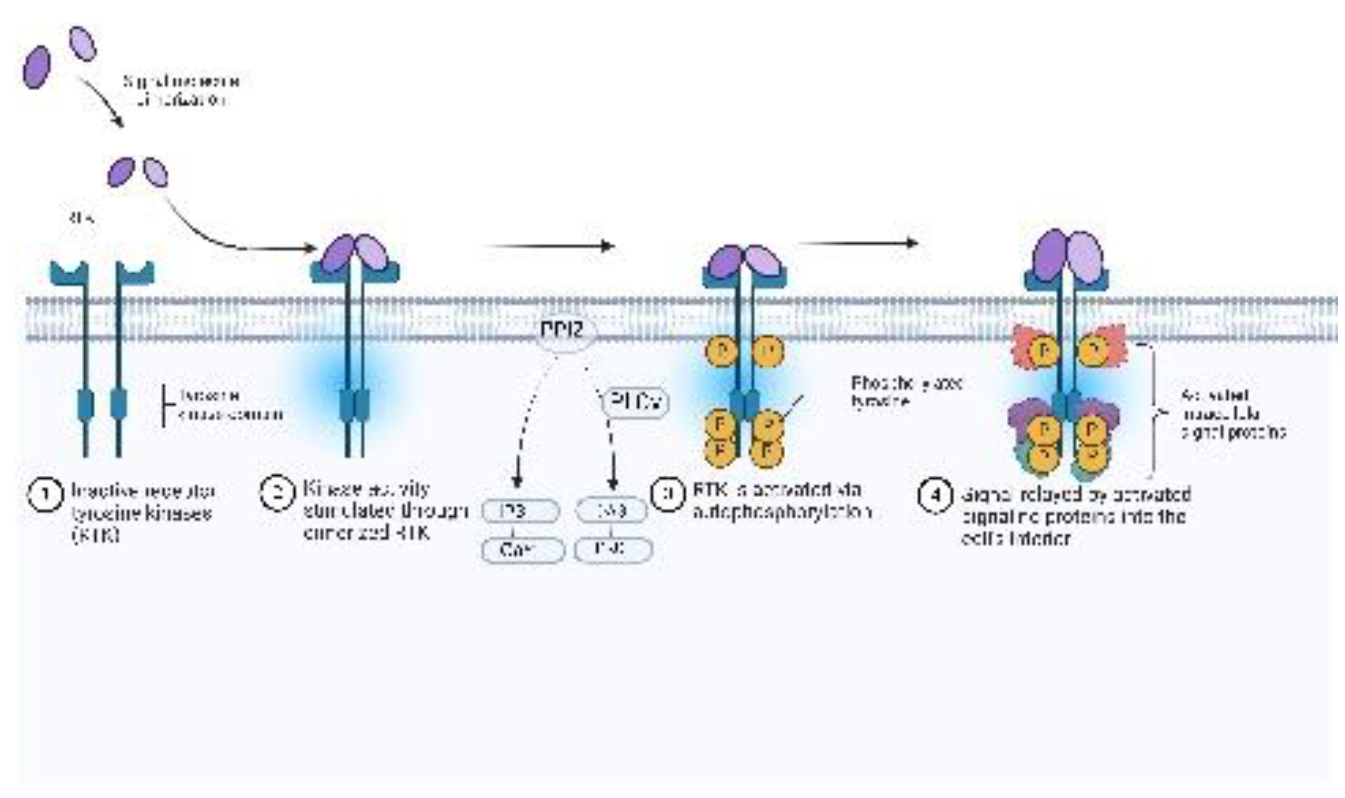

- Tropomyosin Receptor Kinase (TRK)

1.2. Medicinal Chemistry Approaches to Drug Design

2. Results

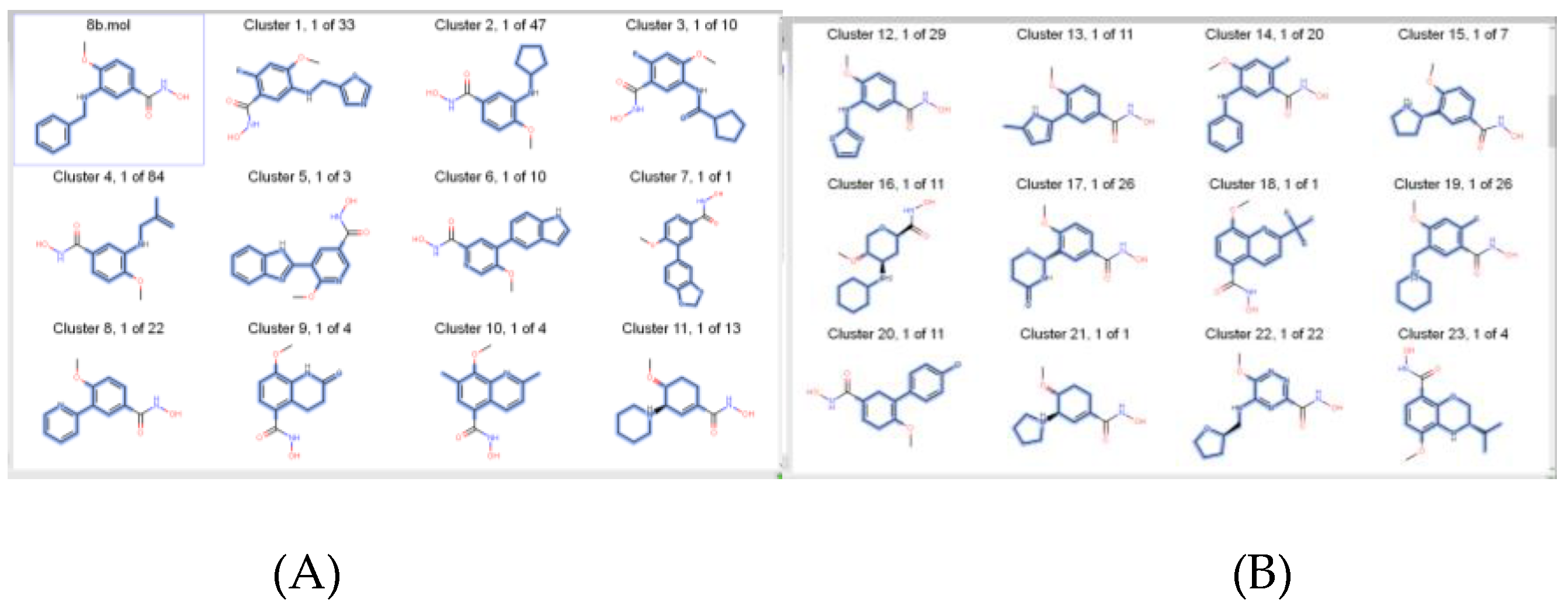

2.1. Medicinal Chemistry Results

| Target | Lead Compound 1 | Lead compound 2 | Protein /Receptor |

|---|---|---|---|

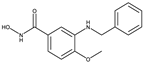

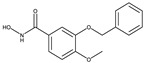

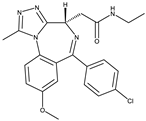

| 1-Histone Deacetylase 8 Inhibitors |  |

|

2V5X and 2V5W[36] |

| 8b[37] | 20a[37] | ||

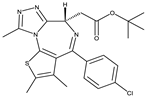

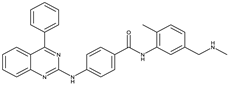

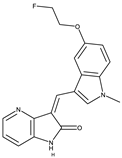

| 2-Bromodomain Inhibitors |

JQ1[15] |

BET762[15] |

4BJX[38] and 5UY9[39] |

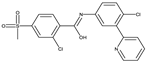

| 3-HH inhibitors |

BMS-833923[40] |

Vismodegib[41] |

5L7I[42] and 3N1P[43] |

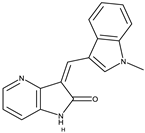

| 4-Tropomyosin Receptor Kinase Inhibitors |

GW441759 [44] |

Compound 10[44] |

4AT3[45] and 3V5Q[46] |

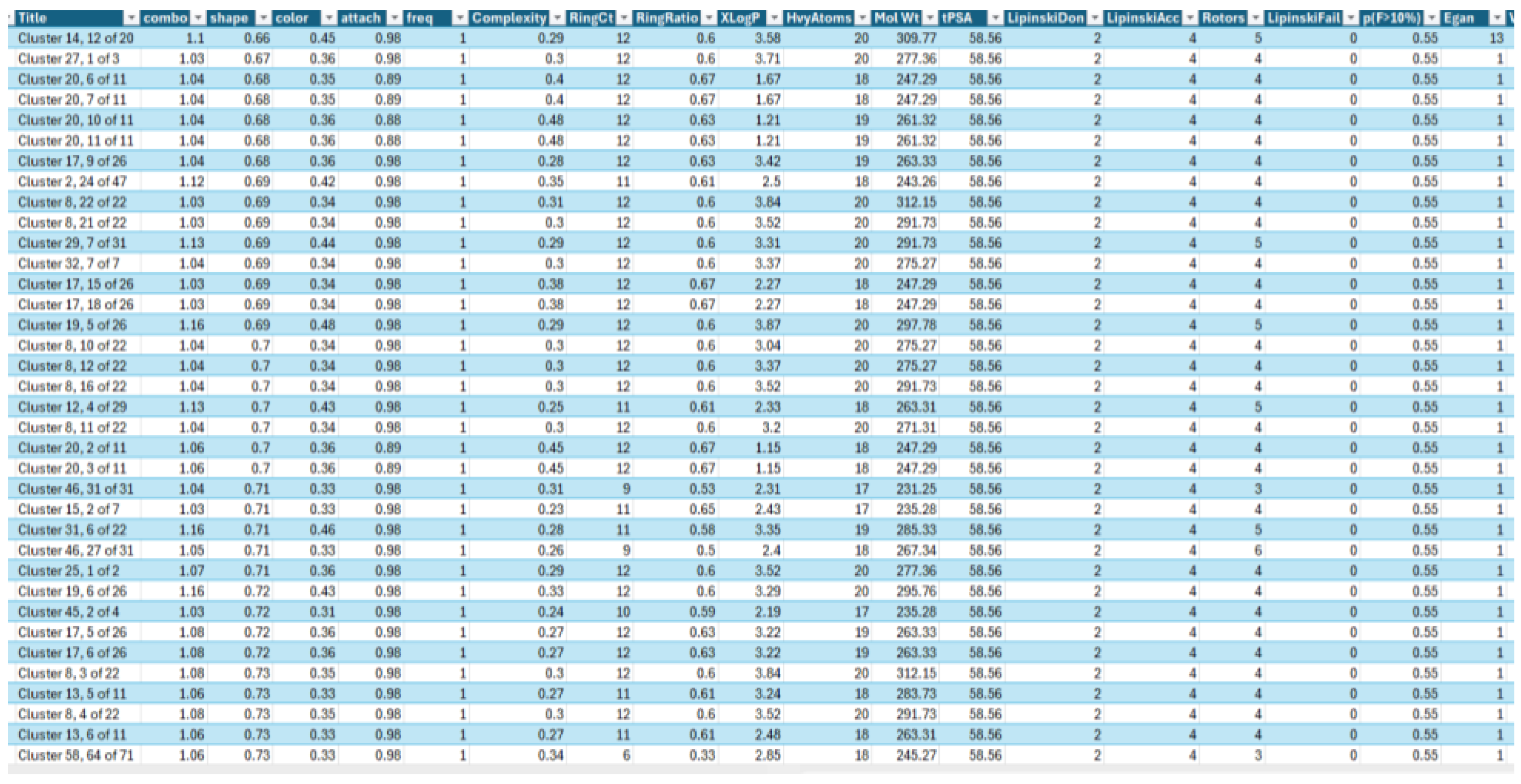

- 1)

- AroRingCt: Number of aromatic rings in the molecule,

- 2)

- ClusterID/IdeaGroup: ClusterID of the molecule;

- 3)

- Colour: The replacement fragment's colour Tanimoto score in comparison to the query fragment;

- 4)

- Combo: Tanimoto combo score for the replacement fragment's shape and colour in comparison to the query fragment;

- 5)

- Egan: The Boolean indicates if the molecule satisfies the Egan bioavailability model;

- 6)

- Fragment: SMILES string of the replacement fragment;

- 7)

- Freq: The replacement fragment's frequency;

- 8)

- fsp3C: The molecule's fraction of sp3 hybridized carbon atoms;

- 9)

- HvyAtoms: Number of heavy atoms in the molecule;

- 10)

- LipinskiDon: Number of Lipinski donors in the molecule;

- 11)

- LipinkskiAcc: Number of Lipinski acceptors in the molecule;

- 12)

- LipinskiFail: Boolean specifying whether the molecule fails Lipinski’s rule of five;

- 13)

- Local strain: Calculated local strain of the molecule;

- 14)

- Molecular TanimotoCombo: Shape + colour Tanimoto combo score of the molecule against the query molecule;

- 15)

- MolWt: Molecular weight of the molecule;

- 16)

- p(active): Belief score of the molecule;

- 17)

- RingCt: Number of ring atoms;

- 18)

- RingRatio: Ratio of the number of ring atoms to the total number of heavy atoms;

- 19)

- Rotors: Number of rotatable bonds in the molecule;

- 20)

- shape: Compare the replacement fragment's Shape Tanimoto score to that of the query fragment;

- 21)

- Source Mols: SMILES strings of the molecules the replacement fragment is part of;

- 22)

- Source Mol Labels: Labels of the molecules the replacement fragment is part of;

- 23)

- tPSA: Calculated topological polar surface area of the molecule;

- 24)

- Veber: Boolean specifying whether the molecule passes the Veber bioavailability model, and

- 25)

- XlogP: Calculated LogP of the molecule [47].

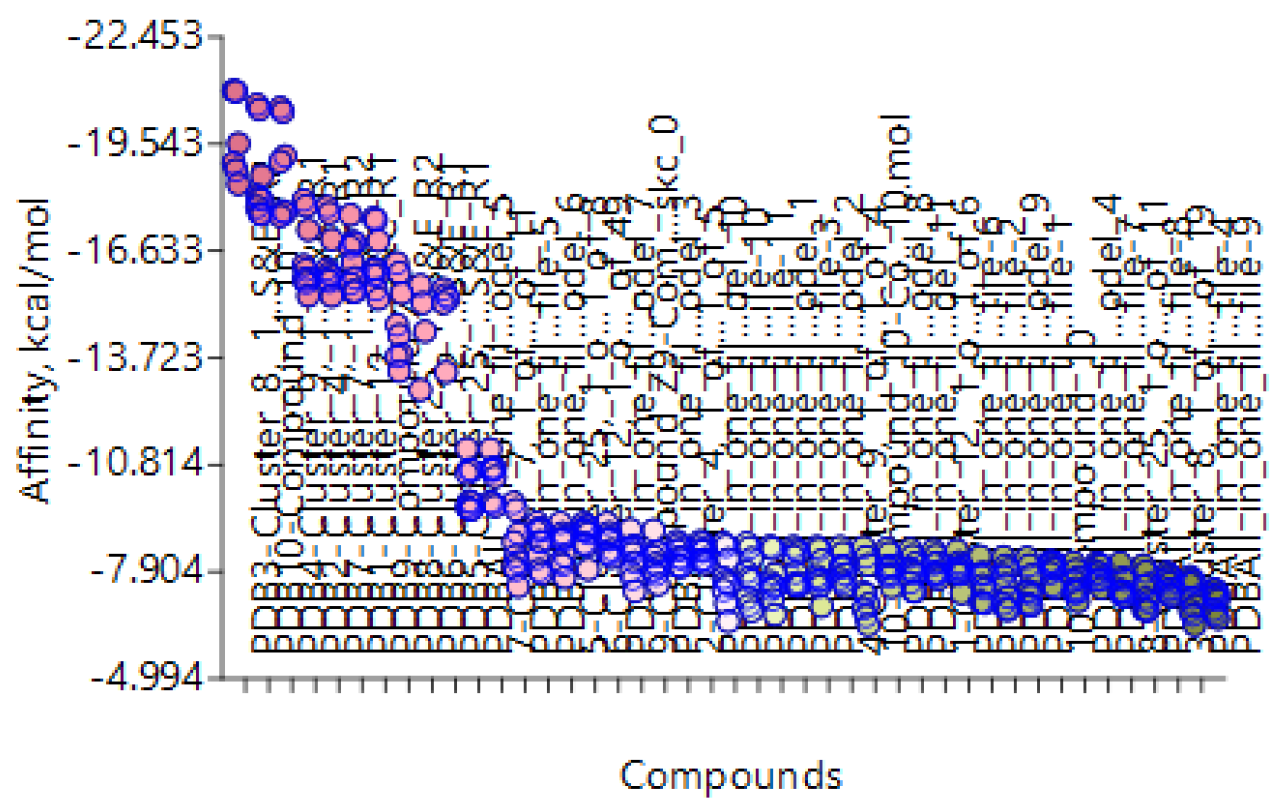

| Column1 | Clusters from Bromodomain (BRD) | AFITT | FRED | AutoDock Vina extended | Molegro | Fitted |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Cluster 3, 1 of 3 | 0.766 | -6.474 | -8.124 | -4.86 | -25.259 |

| 2 | Cluster 25, 1 of 12 | 0.6863 | -8.315 | -8.549 | 89.3 | -26.775 |

| 3 | Cluster 16, 1 of 2 | 0.7356 | -6.337 | -7.542 | 52.9 | -21.687 |

| 4 | Cluster 15, 1 of 2 | 0.553 | -5.308 | -7.048 | 33.28 | -23.624 |

| 5 | Cluster 4, 1 of 4 | 0.4898 | -5.693 | -8.403 | 36.98 | -25.566 |

| 6 | Cluster 24, 1 of 7 | 0.4644 | -8.556 | -8.909 | 80.89 | -30.289 |

| 7 | Cluster 23, 1 of 1 | 0.497 | -5.955 | -7.795 | 9.34 | -24.131 |

| 8 | Cluster 10, 1 of 1 | 0.7103 | -4.672 | -7.71 | 5.23 | -21.734 |

| 9 | BET-762-Lead compound | 0.6691 | -7.528 | -7.971 | 49.84 | -19.709 |

| 10 | JQ1-Lead compound | 0.6084 | -8.133 | -7.006 | 99.29 | -22.161 |

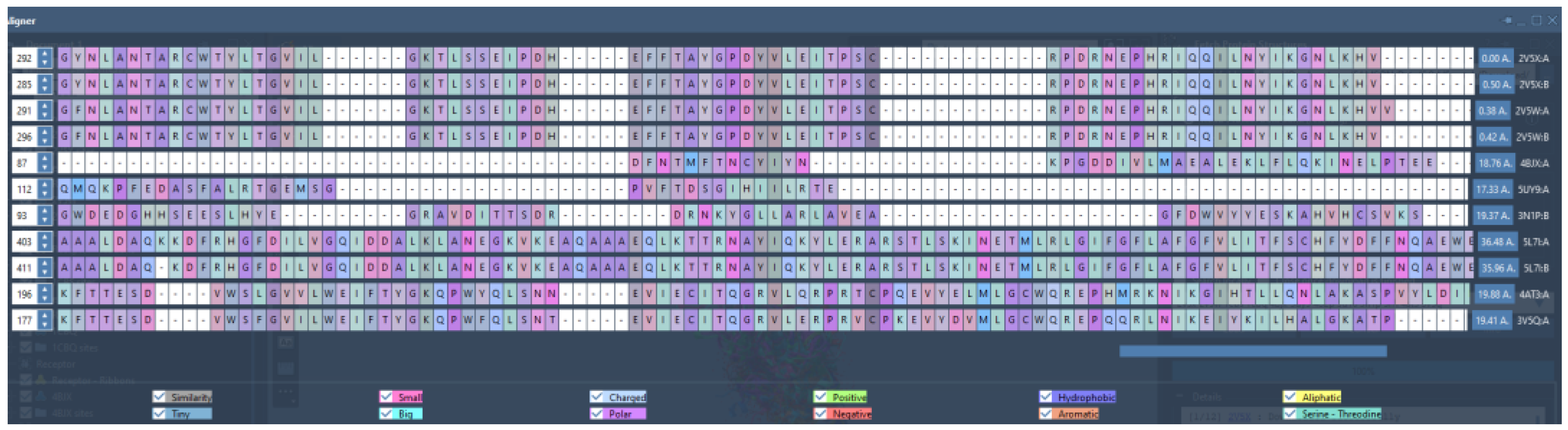

| Clusters HDACs | AFITT | Clusters BRD | AFITT | Clusters HH | AFITT | Clusters Tropomyosin | AFITT | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2V5X | 2V5W | 4BJX | 5UY9 | 5L7I | 3N1P | 4AT3 | 3V5Q | ||||

| Cluster 22, 1 of 22 | 0.652 | 0.541 | Cluster 3, 1 of 3 | 0.77 | 0.42 | Cluster 4, 1 of 1 | 0.552 | 0.336 | Cluster 12, 1 of 6 | 0.638 | 0.438 |

| Cluster 21, 1 of 11 | 0.650 | 0.499 | Cluster 25, 1 of 12 | 0.69 | 0.39 | Cluster 8, 1 of 1 | 0.514 | 0.385 | Cluster 4, 1 of 5 | 0.685 | 0.438 |

| Cluster 16,1 of 65 | 0.650 | 0.541 | Cluster 16, 1 of 2 | 0.74 | 0.33 | Cluster 1, 1 of 3 | 0.521 | 0.330 | Cluster 8, 1 of 19 | 0.435 | 0.438 |

| Cluster 23, 1 of 1 | 0.645 | 0.532 | Cluster 15, 1 of 2 | 0.55 | 0.39 | Cluster 9, 1 of 1 | 0.513 | 0.404 | Cluster 9, 1 of 4 | 0.622 | 0.539 |

| Cluster 1, 1 of 26 | 0.642 | 0.504 | Cluster 4, 1 of 4 | 0.49 | 0.33 | Cluster 8, 1 of 29 | 0.496 | 0.432 | Cluster 25, 1 of 8 | 0.675 | 0.521 |

| Cluster 7, 1 of 26 | 0.635 | 0.527 | Cluster 24, 1 of 7 | 0.46 | 0.37 | Cluster 21, 1 of 99 | 0.493 | 0.340 | Cluster 12, 1 of 49 | 0.630 | 0.627 |

| Cluster 4, 1 of 28 | 0.633 | 0.499 | Cluster 23, 1 of 1 | 0.50 | 0.37 | Cluster 15, 1 of 6 | 0.491 | 0.374 | Cluster 7, 1 of 11 | 0.643 | 0.596 |

| Cluster 10, 1 of 86 | 0.632 | 0.517 | Cluster 10, 1 of 1 | 0.71 | 0.37 | Cluster 23, 1 of 1 | 0.478 | 0.470 | Cluster 25, 1 of 11 | 0.491 | 0.614 |

| Cluster 12, 1 of 50 | 0.631 | 0.524 | BET-762 | 0.67 | 0.39 | Cluster 17, 1 of 1 | 0.471 | 0.364 | Compound Z9 | 0.596 | 0.543 |

| 20A | 0.631 | 0.511 | JQ1 | 0.61 | 0.41 | Cluster 20, 1 of 12 | 0.463 | 0.389 | Compound 10 | 0.560 | 0.505 |

| 8B | 0.629 | 0.516 | Vesmodigib | 0.363 | 0.363 | ||||||

| BMS-833923 | 0.313 |

- 1)

- Bioconcentration factor: ratio of the chemical concentration in fish as a result of absorption via the respiratory surface to that in water at a steady state.

- 2)

- Ames mutagenicity: A compound is positive for mutagenicity if it induces revertant colony growth in any strain of Salmonella typhimurium.

- 3)

- Oral rat LD50: Amount of chemical (mg/kg body weight) that causes 50% of rats to die after oral ingestion.

- 4)

- 48-hour T. pyriformis IGC50: Concentration of the test chemical in water (mg/L) that causes 50% growth inhibition to Tetrahymena pyriformis after 48 hours.

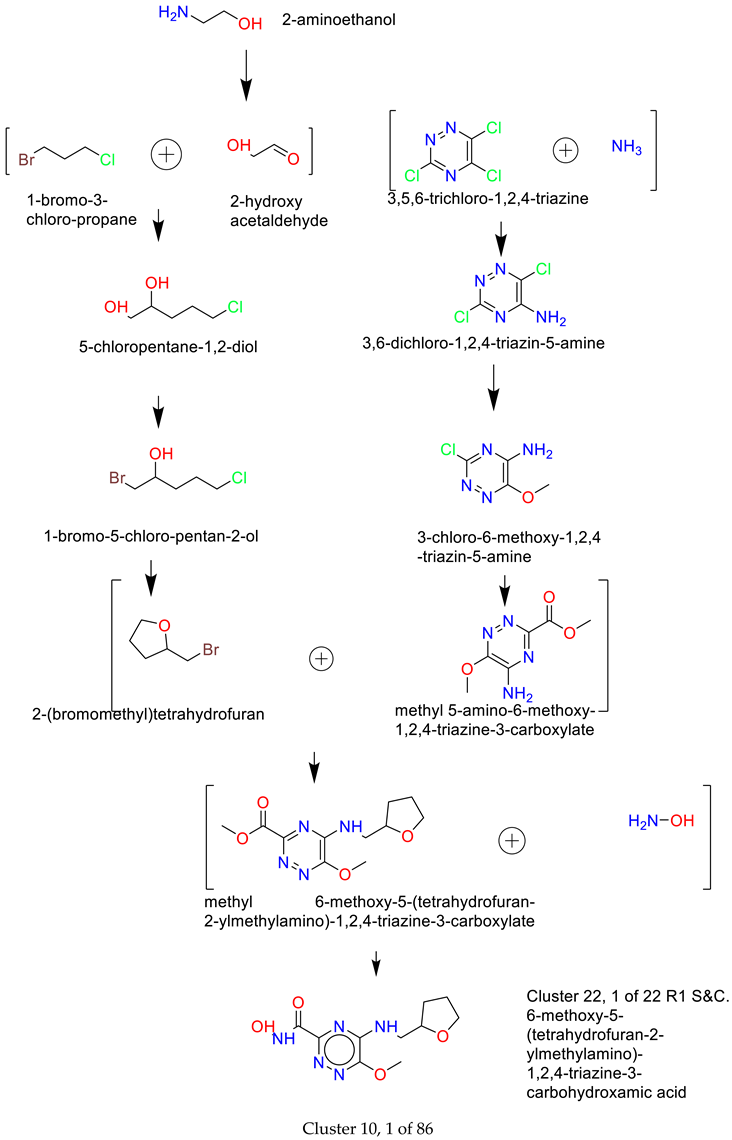

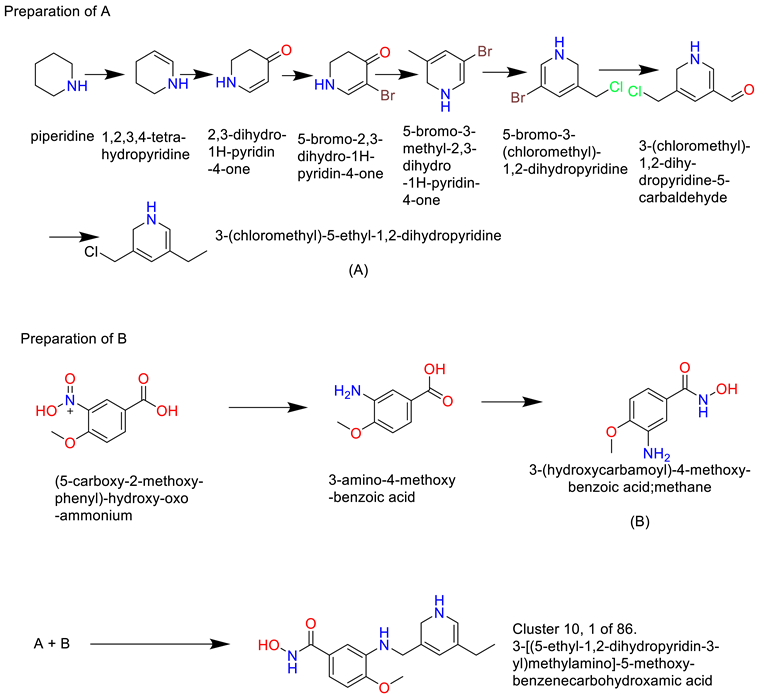

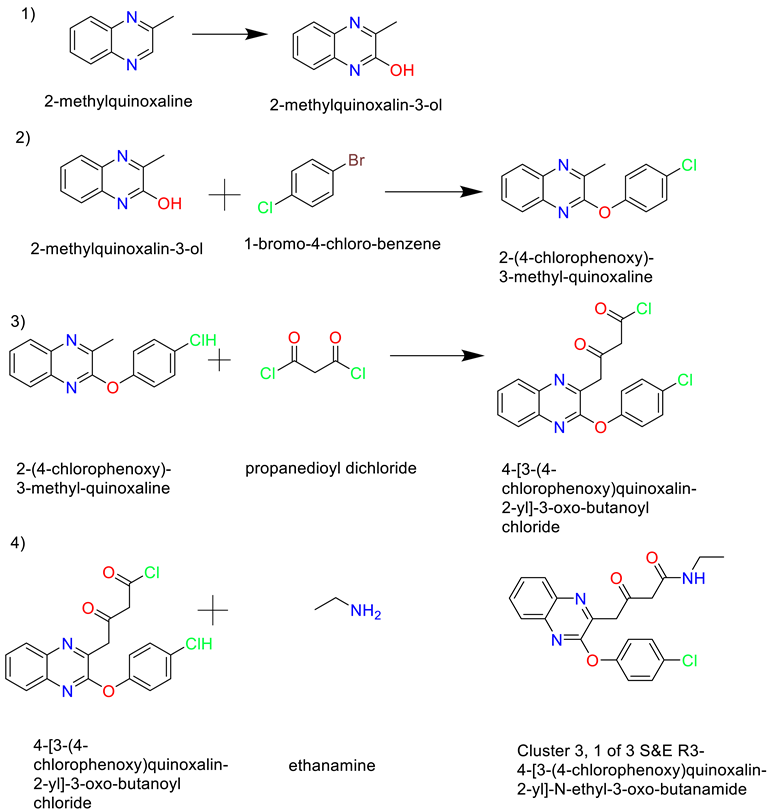

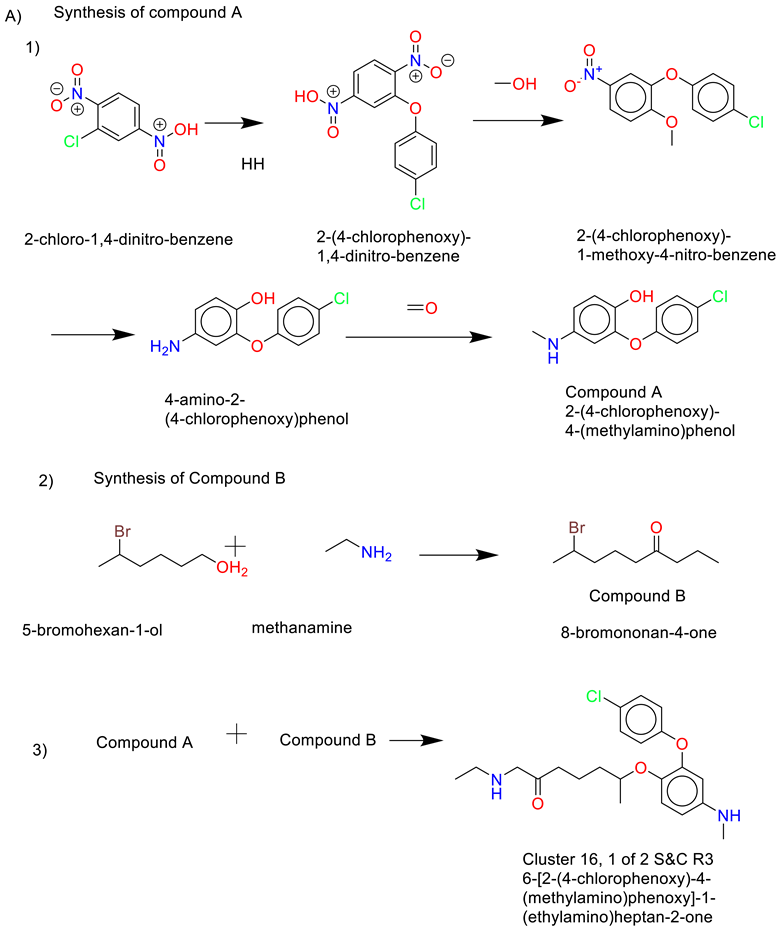

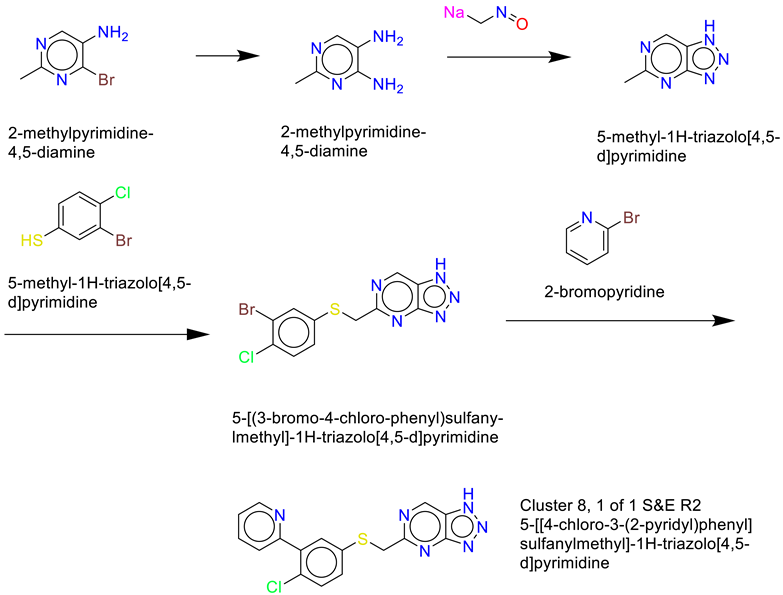

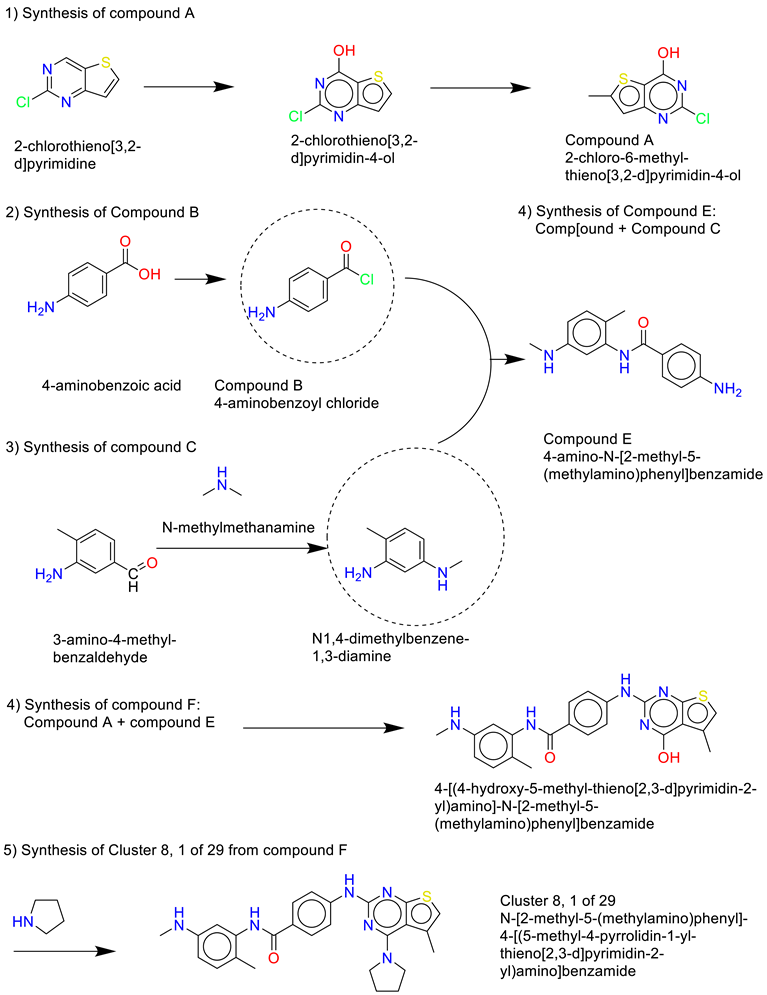

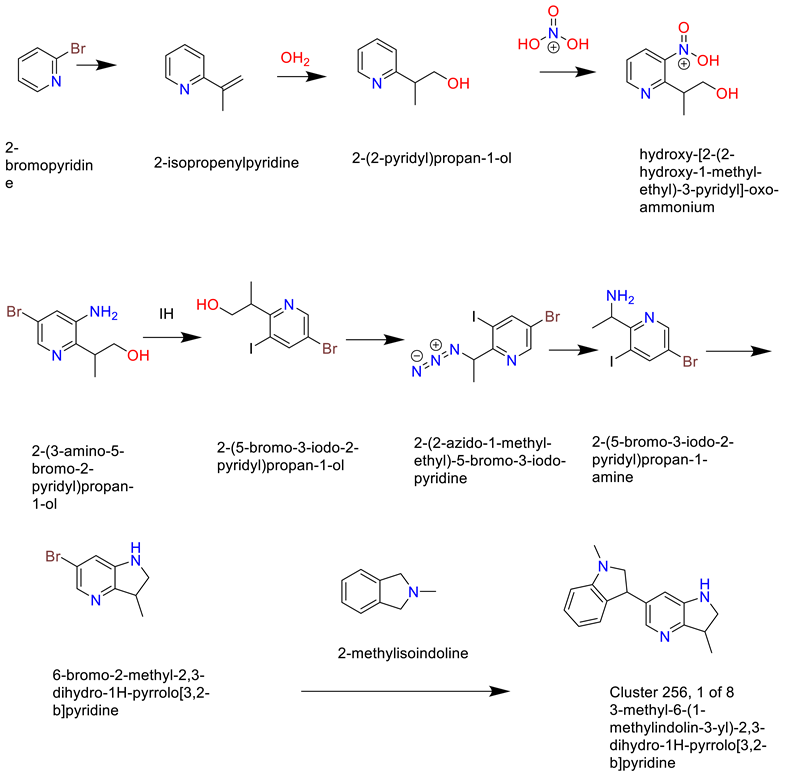

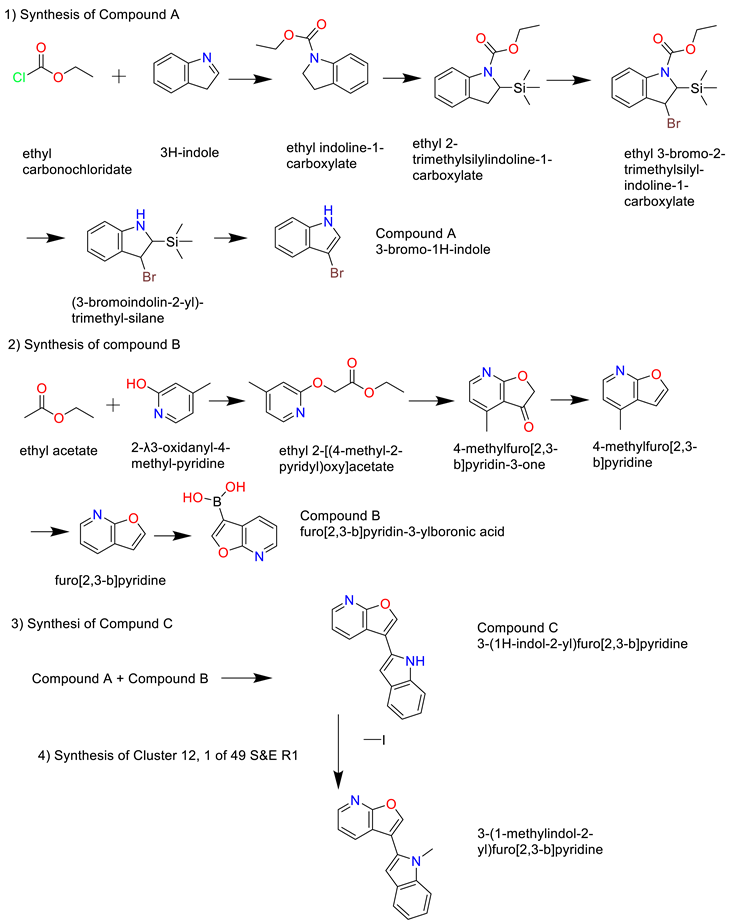

2.2. Retrosynthesis Results Using Spaya

- 1)

- Synthesis of Cluster 22, 1 of 22 R1 S&C[35]

- 2)

- Cluster 10, 1 of 86

- 3)

- Cluster 3, 1 of 3

- 4)

- Cluster 16, 1 of 2

- 5)

- Cluster 8, 1 of 1

- 6)

- Cluster 8, 1 of 29

- 7)

- Cluster 25, 1 of 8

- 8)

- Cluster 12, 1 of 49

3. Discussion

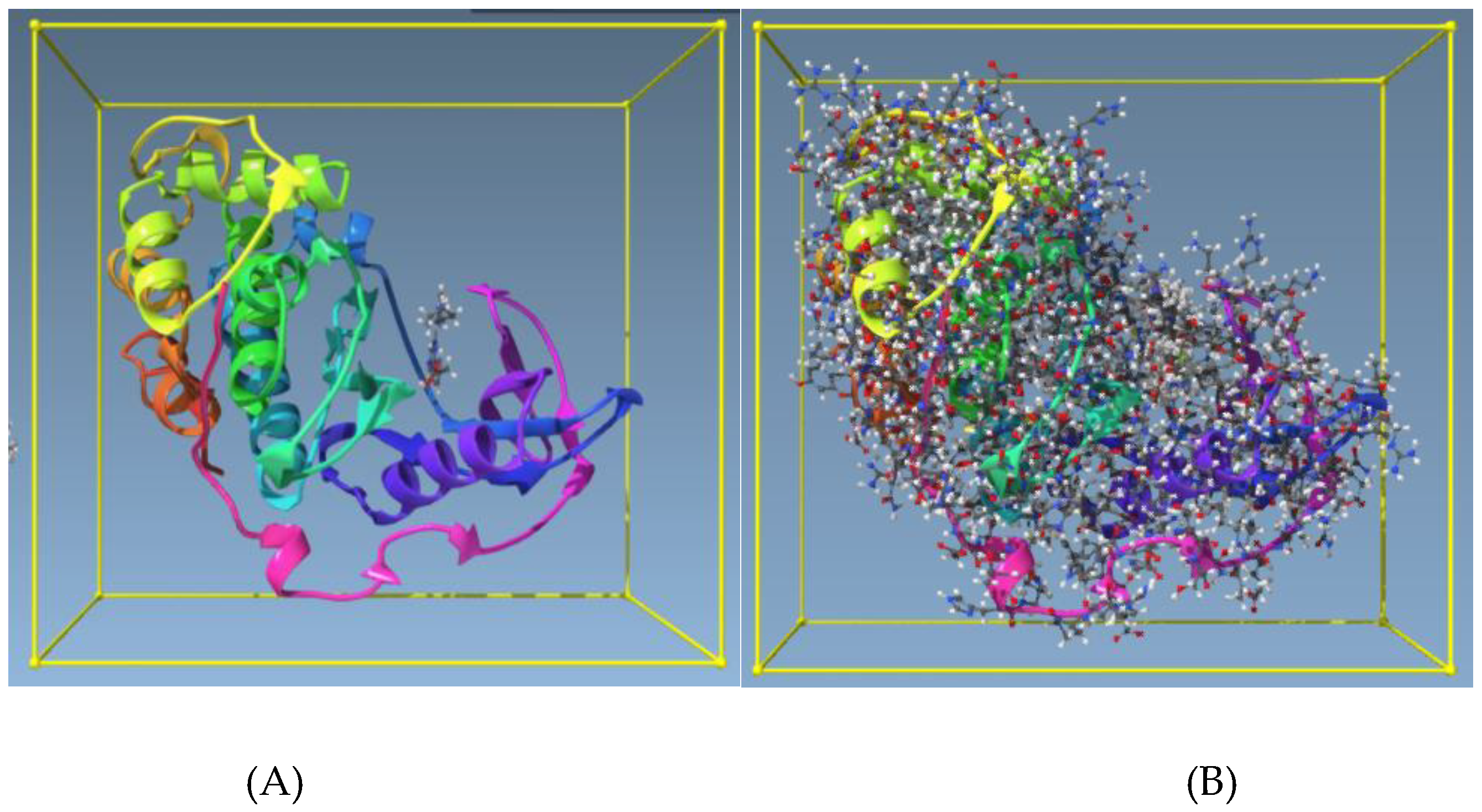

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Materials

- OpenEye Scientific programs, which include various applications, are being used. The suite comprises BROOD, MakeReceptor, FRED, and AFITT.

- Molegro Virtual Docker.

- The Samson suite includes Autodock Vina extended, the Fitted suite by Molecular Forecaster, and Protein Aligner.

- Toxicity Estimation Software Tools (TEST).

- BIOVIA Discovery Studio Visualizer.

- Spaya-retrosynthesis software.

4.2. Method

- Identifying drug targets.

- Selection of two proteins (receptors) for each target and downloading the PDB files and their electron density map from the Protein Data Bank database.

- Comparing the similarities of the receptors. Run protein similarity on Samson (Protein Aligner) to determine suitability.

- Selection of two lead compounds from each type.

- Run the lead compounds on BROOD (from the OpenEye suite) and produce hit lists using Shape and Colour and Shape and Electrostatics.

- Receptor preparations using MakeReceptor from the OpenEye suite.

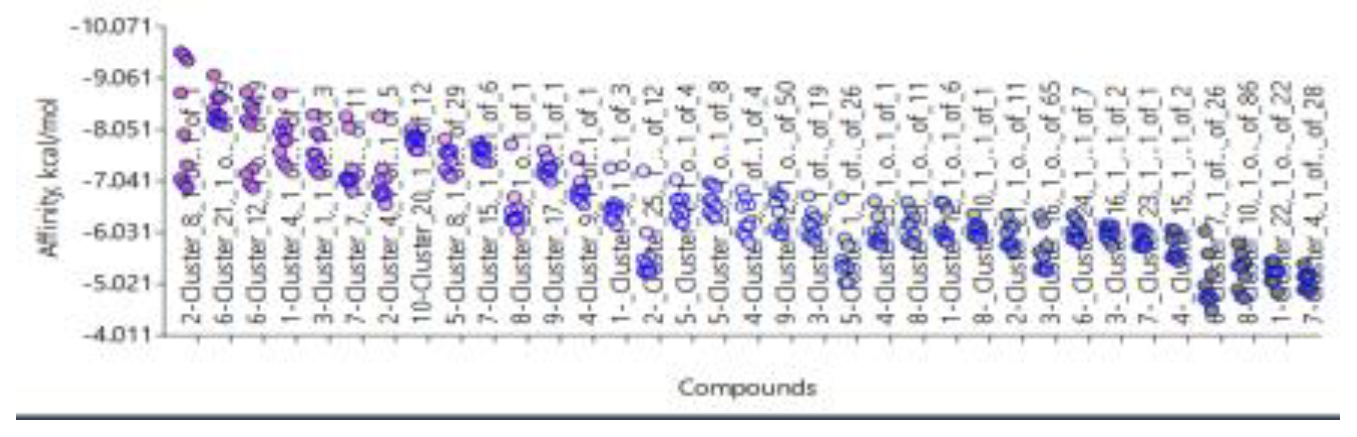

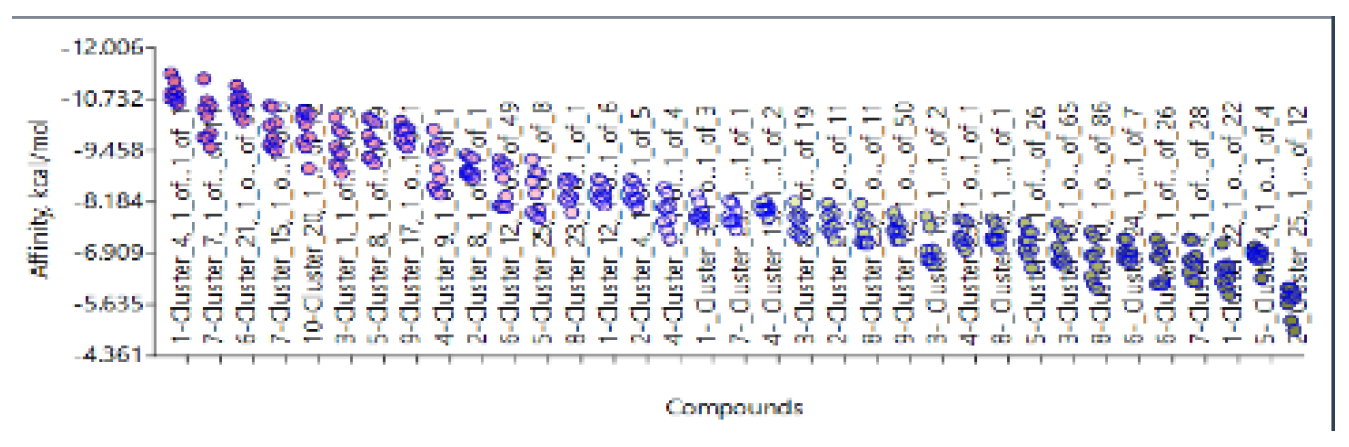

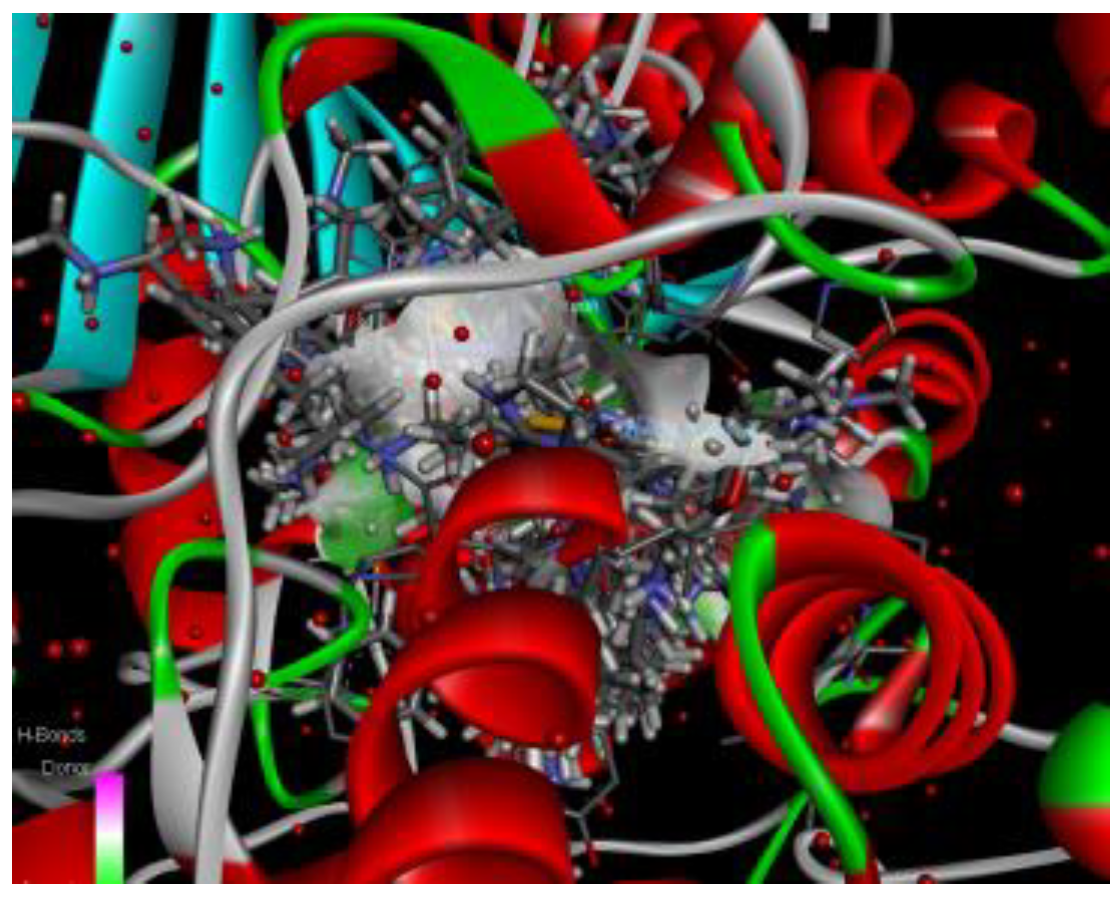

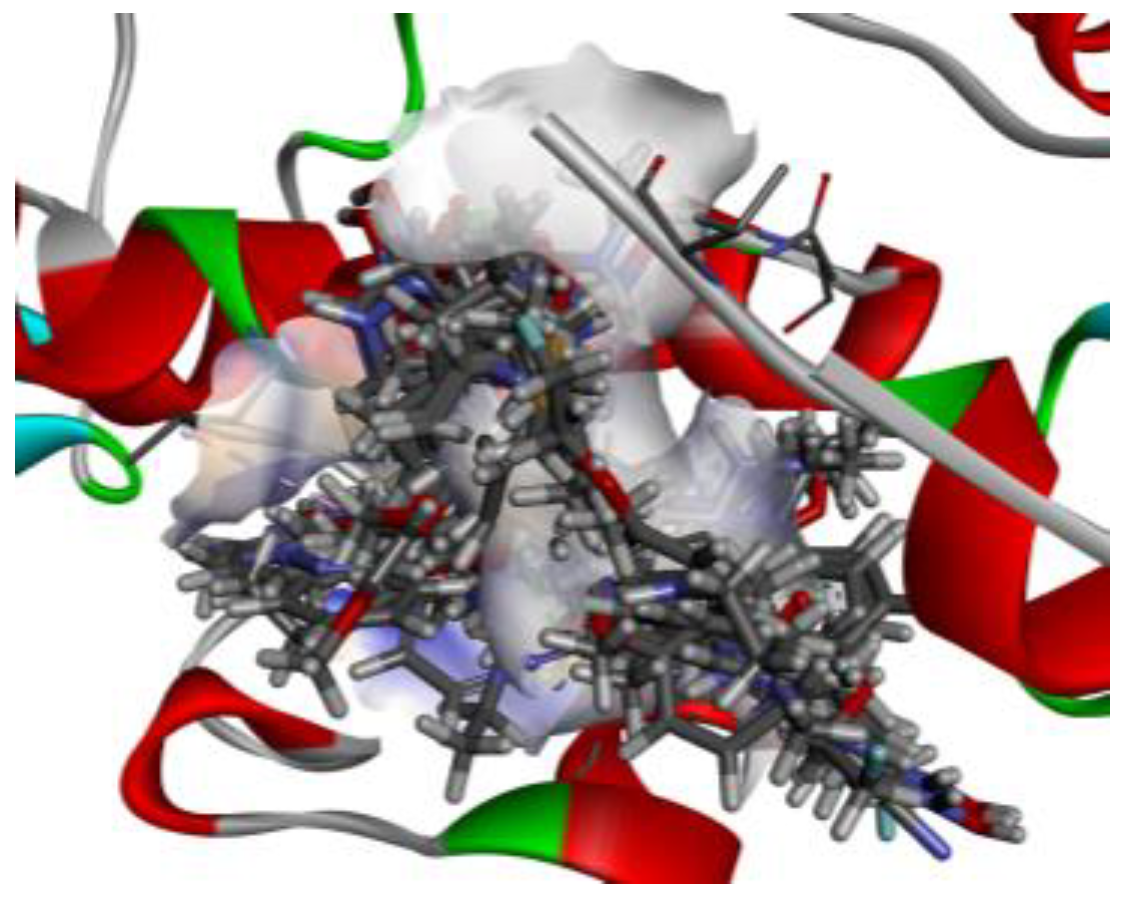

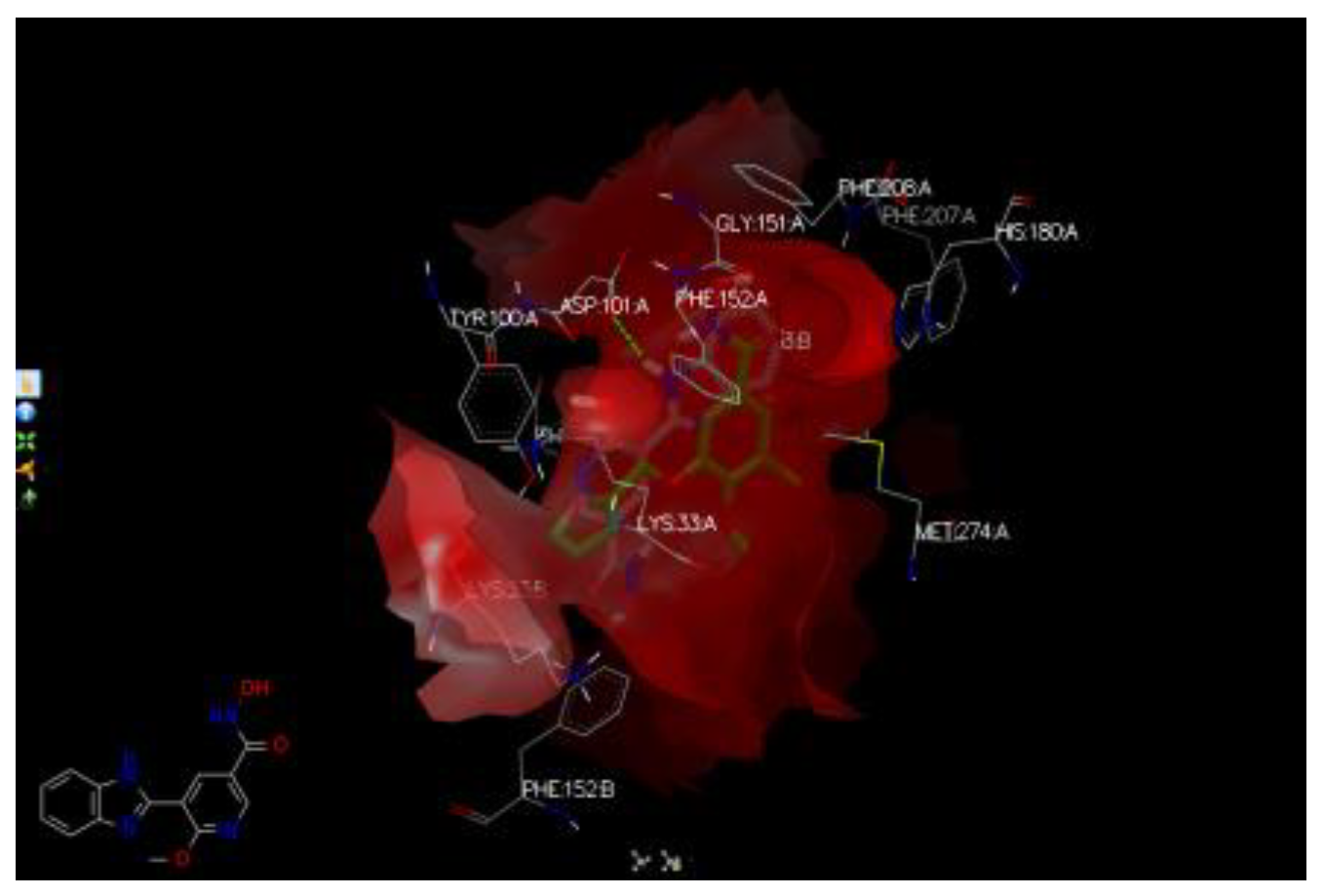

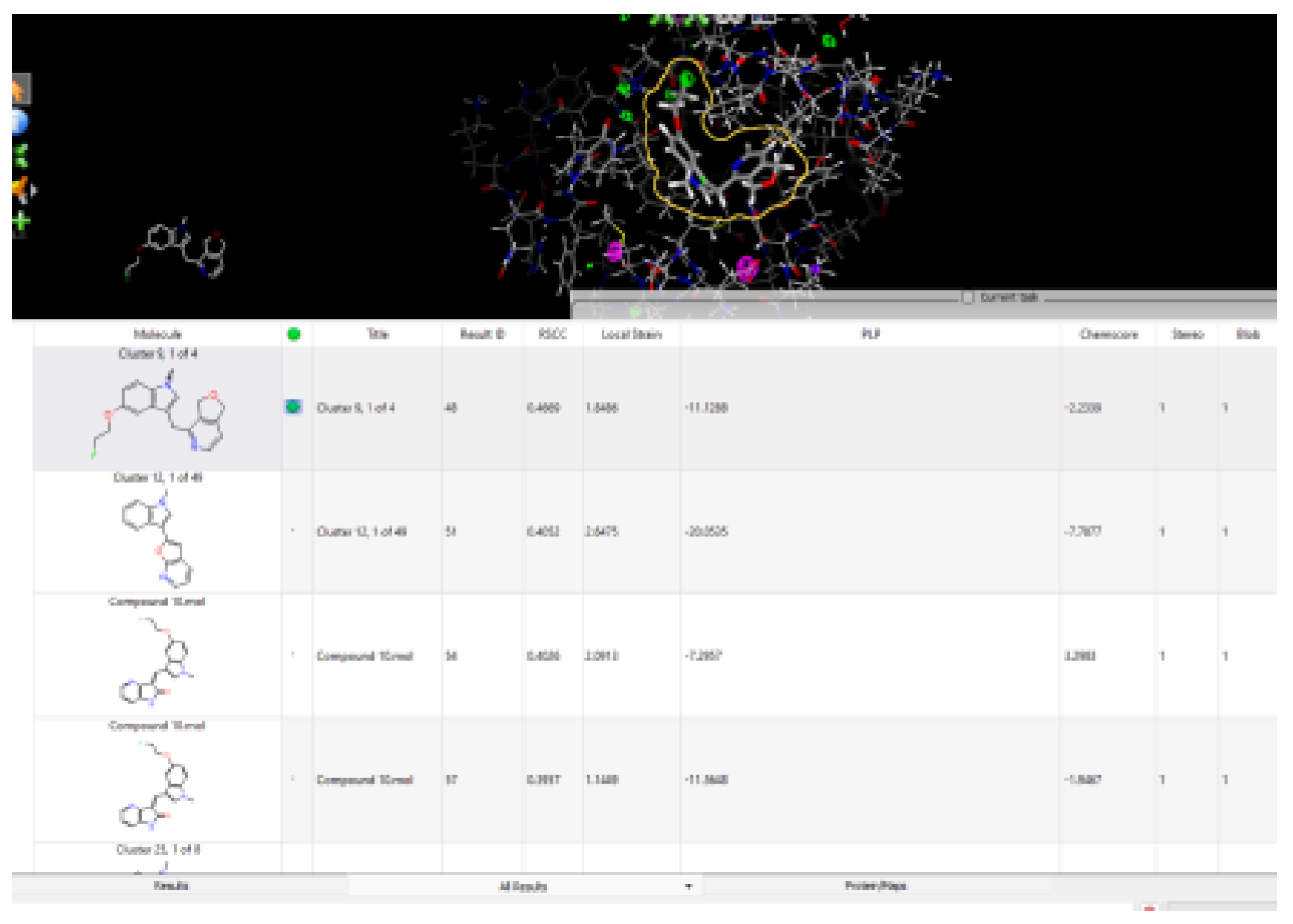

- Docking the hit compounds with OpenEye suite (FRED), Molegro, and Samson suite (AutoDockVina and Fitted).

- Run cross-docking; each hitlist clusters from one target to the other 3 targets (using their protein/receptor).

- Run hits with AFITT to rank the compounds according to their fitting probabilities.

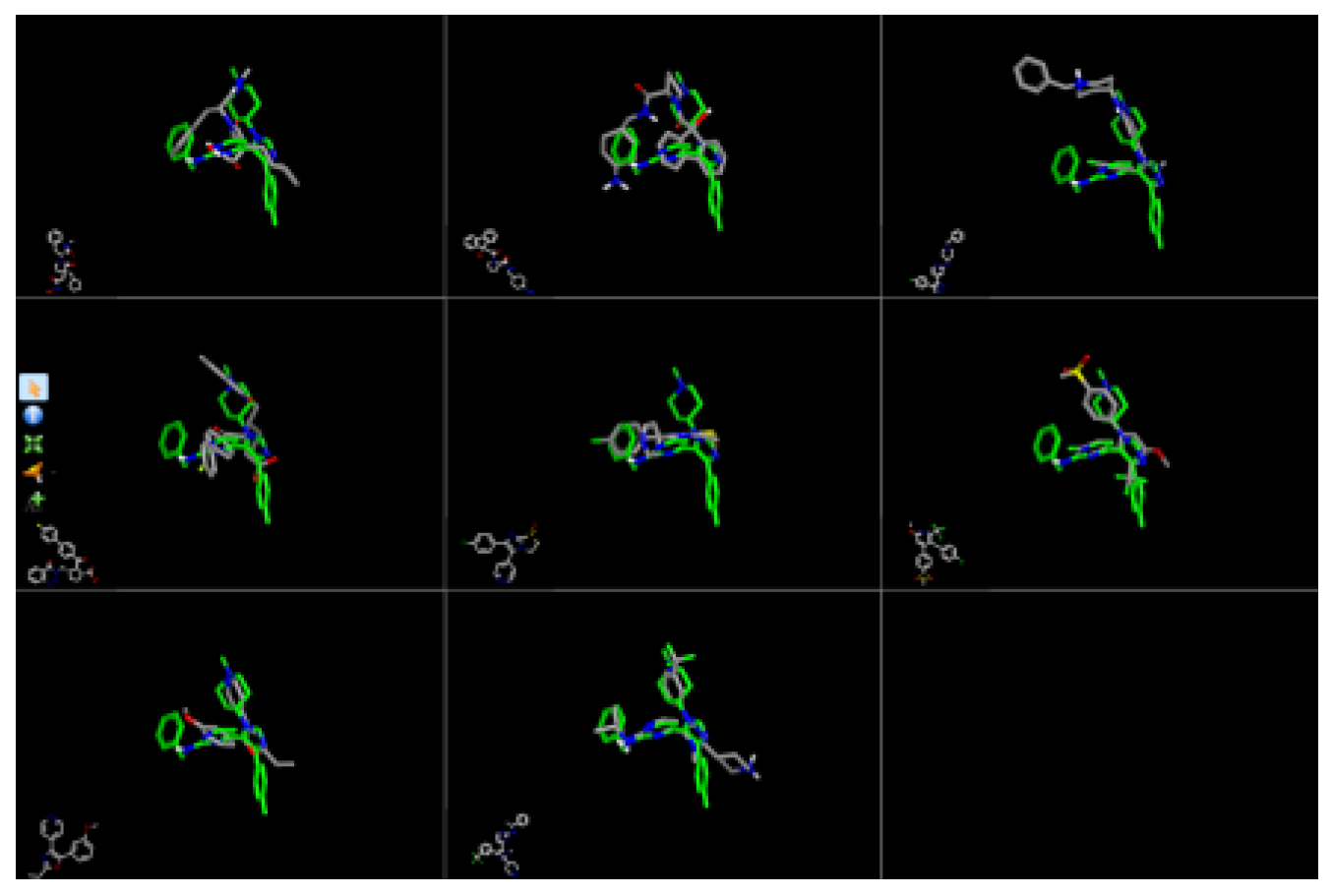

- Run selected clusters on ROCS.

- Run selected clusters on Toxicity Estimation Software Tools (TEST)

- Run clusters on Spaya to find the best synthesis route.

5. Conclusions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Cullinane, C.J.; Burchill, S.A.; Squire, J.A.; O'Leary, J.J.; Lewis, I.J. Molecular Biology and Pathology of Paediatric Cancer; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Paraboschi, I.; Privitera, L.; Kramer-Marek, G.; Anderson, J.; Giuliani, S. Novel Treatments and Technologies Applied to the Cure of Neuroblastoma. Children (Basel) 2021, 8, 482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, S.; Carpenter, G. Human epidermal growth factor: isolation and chemical and biological properties. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 1975, 72, 1317–1321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Inomistova, M.; Khranovska, N.; Skachkova, O. Role of Genetic and Epigenetic Alterations in Pathogenesis of Neuroblastoma; Academic Press, 2019; pp. 23–41. [Google Scholar]

- Bhoopathi, P.; Mannangatti, P.; Emdad, L.; Das, S.K.; Fisher, P.B. The quest to develop an effective therapy for neuroblastoma. J Cell Physiol 2021, 236, 7775–7791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerges, A.; Canning, U. Neuroblastoma and its Targets Therapies: A Medicinal Chemistry Review. ChemMedChem 2024, 19, e202300535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, W.L.; Pei, J.F.; Lai, L.H. Computational Multitarget Drug Design. Journal of Chemical Information and Modeling 2017, 57, 403–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anighoro, A.; Bajorath, J.; Rastelli, G. Polypharmacology: Challenges and Opportunities in Drug Discovery. Journal of Medicinal Chemistry 2014, 57, 7874–7887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Knight, Z.A.; Lin, H.; Shokat, K.M.; Knight, Z.A.; Lin, H.; Shokat, K.M. Targeting the cancer kinome through polypharmacology. Nature Reviews Cancer 2010, 10, 130–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ooms, F. Molecular Modeling and Computer Aided Drug Design. Examples of their Applications in Medicinal Chemistry. Current Medicinal Chemistry 2000, 7, 141–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumalo, H.M.; Bhakat, S.; Soliman, M.E.S.; Kumalo, H.M.; Bhakat, S.; Soliman, M.E.S. Theory and Applications of Covalent Docking in Drug Discovery: Merits and Pitfalls. Molecules 2015, 20, 1984–2000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolden, J.E.; Peart, M.J.; Johnstone, R.W. Anticancer activities of histone deacetylase inhibitors. Nat Rev Drug Discov 2006, 5, 769–784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oehme, I.; Deubzer, H.E.; Wegener, D.; Pickert, D.; Linke, J.P.; Hero, B.; Kopp-Schneider, A.; Westermann, F.; Ulrich, S.M.; von Deimling, A.; et al. Histone deacetylase 8 in neuroblastoma tumorigenesis. Clin Cancer Res 2009, 15, 91–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tamkun, J.W.; Deuring, R.; Scott, M.P.; Kissinger, M.; Pattatucci, A.M.; Kaufman, T.C.; Kennison, J.A. brahma: a regulator of Drosophila homeotic genes structurally related to the yeast transcriptional activator SNF2/SWI2. Cell 1992, 68, 561–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez-Salvia, M.; Esteller, M. Bromodomain inhibitors and cancer therapy: From structures to applications. Epigenetics 2017, 12, 323–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, G.-Q.; Guo, W.-Z.; Zhang, Y.; Seng, J.-J.; Zhang, H.-P.; Ma, X.-X.; Zhang, G.; Li, J.; Yan, B.; Tang, H.-W.; et al. Suppression of BRD4 inhibits human hepatocellular carcinoma by repressing MYC and enhancing BIM expression. Oncotarget 2015, 7, 6275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mirguet, O.; Gosmini, R.; Toum, J.; Clement, C.A.; Barnathan, M.; Brusq, J.M.; Mordaunt, J.E.; Grimes, R.M.; Crowe, M.; Pineau, O.; et al. Discovery of epigenetic regulator I-BET762: lead optimization to afford a clinical candidate inhibitor of the BET bromodomains. J Med Chem 2013, 56, 7501–7515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peukert, S.; Miller-Moslin, K. Small-molecule inhibitors of the hedgehog signaling pathway as cancer therapeutics. ChemMedChem 2010, 5, 500–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nusslein-Volhard, C.; Wieschaus, E. Mutations affecting segment number and polarity in Drosophila. Nature 1980, 287, 795–801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lum, L.; Beachy, P.A. The Hedgehog response network: sensors, switches, and routers. Science 2004, 304, 1755–1759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skoda, A.M.; Simovic, D.; Karin, V.; Kardum, V.; Vranic, S.; Serman, L. The role of the Hedgehog signaling pathway in cancer: A comprehensive review. Bosn J Basic Med Sci 2018, 18, 8–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodrich, L.V.; Scott, M.P. Hedgehog and patched in neural development and disease. Neuron 1998, 21, 1243–1257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCarthy, C.; Walker, E. Tropomyosin receptor kinase inhibitors: a patent update 2009 – 2013. Expert Opinion on Therapeutic Patents 2014, 24, 731–744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bailey, J.J.; Jaworski, C.; Tung, D.; Wängler, C.; Wängler, B.; Schirrmacher, R. Tropomyosin receptor kinase inhibitors: an updated patent review for 2016–2019. Expert Opinion on Therapeutic Patents 2020, 30, 1737011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Richard Morphy, C.K. , Zoran Rankovic. From magic bullets to designed multiple ligands. Drug Discovery Today 2004, 9, 641–651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, X.; Li, X.; Liu, F.; Li, S.; Shi, D. Rational Multitargeted Drug Design Strategy from the Perspective of a Medicinal Chemist. J Med Chem 2021, 64, 10581–10605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, L.-h.; Evers, A.; Monecke, P.; Naumann, T. Ligand based lead generation - considering chemical accessibility in rescaffolding approaches via BROOD. Journal of Cheminformatics 2012, 4, o20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGann, M. FRED and HYBRID docking performance on standardized datasets. J Comput Aided Mol Des 2012, 26, 897–906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janowski, P.A.; Moriarty, N.W.; Kelley, B.P.; Case, D.A.; York, D.M.; Adams, P.D.; Warren, G.L. Improved ligand geometries in crystallographic refinement using AFITT in PHENIX. Acta Crystallogr D Struct Biol 2016, 72, 1062–1072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-Ramos, M.; Perruccio, F. HPPD: Ligand-and Target-Based Virtual Screening on a Herbicide Target. J Chem Inf Model 2010, 50, 801–814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- VIDA, 5.0.7.0 ed; OpenEye, Cadence Molecular Sciences: Santa Fe, NM, 2024.

- Moitessier, N.; Pottel, J.; Therrien, E.; Englebienne, P.; Liu, Z.; Tomberg, A.; Corbeil, C.R. Medicinal Chemistry Projects Requiring Imaginative Structure-Based Drug Design Methods. Accounts of Chemical Research 2016, 49, 1646–1657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomsen, R.; Christensen, M.H. MolDock: A New Technique for High-Accuracy Molecular Docking. Journal of Medicinal Chemistry 2006, 49, 3315–3321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin T; Harten P; Venkatapathy R; Young, D. T.E.S.T., EPA-ORD-CCTE Clowder: Public Domain Dedication, 2021.

- Parrot, M.; Tajmouati, H.; da Silva, V.B.R.; Atwood, B.R.; Fourcade, R.; Gaston-Mathé, Y.; Do Huu, N.; Perron, Q.; Parrot, M.; Tajmouati, H.; et al. Integrating synthetic accessibility with AI-based generative drug design. Journal of Cheminformatics 2023, 15, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vannini, A.; Volpari, C.; Gallinari, P.; Jones, P.; Mattu, M.; Carfí, A.; Francesco, R.D.; Steinkühler, C.; Marco, S.D. Substrate binding to histone deacetylases as shown by the crystal structure of the HDAC8–substrate complex. EMBO reports 2007, 8, 879–884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heimburg, T.; Kolbinger, F.R.; Zeyen, P.; Ghazy, E.; Herp, D.; Schmidtkunz, K.; Melesina, J.; Shaik, T.B.; Erdmann, F.; Schmidt, M.; et al. Structure-Based Design and Biological Characterization of Selective Histone Deacetylase 8 (HDAC8) Inhibitors with Anti-Neuroblastoma Activity. J Med Chem 2017, 60, 10188–10204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wyce, A.; Ganji, G.; Smitheman, K.N.; Chung, C.-w.; Korenchuk, S.; Bai, Y.; Barbash, O.; Le, B.; Craggs, P.D.; McCabe, M.T.; et al. BET Inhibition Silences Expression of MYCN and BCL2 and Induces Cytotoxicity in Neuroblastoma Tumor Models. PLoS One 2023, 8, e72967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, X.; Dong, S.-H.; Chen, J.; Zhou, X.Z.; Chen, R.; Nair, S.; Lu, K.P.; Chen, L.-F.; Hu, X.; Dong, S.-H.; et al. Prolyl isomerase PIN1 regulates the stability, transcriptional activity and oncogenic potential of BRD4. Oncogene 2017, 36, 36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siu, L.L.; Papadopoulos, K.; Alberts, S.R.; Kirchoff-Ross, R.; Vakkalagadda, B.; Lang, L.; Ahlers, C.M.; Bennett, K.L.; Tornout, J.M.V. A first-in-human, phase I study of an oral hedgehog (HH) pathway antagonist, BMS-833923 (XL139), in subjects with advanced or metastatic solid tumors. Journal of Clinical Oncology 2010, 28, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dlugosz, A.; Agrawal, S.; Kirkpatrick, P. Vismodegib. Nature Reviews Drug Discovery 2012, 11, 437–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byrne, E.F.X.; Sircar, R.; Miller, P.S.; Hedger, G.; Luchetti, G.; Nachtergaele, S.; Tully, M.D.; Mydock-McGrane, L.; Covey, D.F.; Rambo, R.P.; et al. Structural basis of Smoothened regulation by its extracellular domains. Nature 2016, 535, 7613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kavran, J.M.; Ward, M.D.; Oladosu, O.O.; Mulepati, S.; Leahy, D.J. All Mammalian Hedgehog Proteins Interact with Cell Adhesion Molecule, Down-regulated by Oncogenes (CDO) and Brother of CDO (BOC) in a Conserved Manner *. Journal of Biological Chemistry 2010, 285, 11607–11616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernard-Gauthier, V.; Aliaga, A.; Aliaga, A.; Boudjemeline, M.; Hopewell, R.; Kostikov, A.; Rosa-Neto, P.; Thiel, A.; Schirrmacher, R. Syntheses and Evaluation of Carbon-11- and Fluorine-18-Radiolabeled pan-Tropomyosin Receptor Kinase (Trk) Inhibitors: Exploration of the 4-Aza-2-oxindole Scaffold as Trk PET Imaging Agents. ACS Chem Neurosci 2014, 6, 260–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bertrand, T.; Kothe, M.; Liu, J.; Dupuy, A.; Rak, A.; Berne, P.F.; Davis, S.; Gladysheva, T.; Valtre, C.; Crenne, J.Y.; et al. The Crystal Structures of TrkA and TrkB Suggest Key Regions for Achieving Selective Inhibition. Journal of Molecular Biology 2012, 423, 439–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Albaugh, P.; Fan, Y.; Mi, Y.; Sun, F.; Adrian, F.; Li, N.; Jia, Y.; Sarkisova, Y.; Kreusch, A.; Hood, T.; et al. Discovery of GNF-5837, a Selective TRK Inhibitor with Efficacy in Rodent Cancer Tumor Models. ACS Med Chem Lett 2012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- OpenEye, C.M.S. BROOD. OpenEye, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Discovery Studio Visualizer, v24.1.0.23298 ed; Dassault Systemes Biovia Corp, 2023.

- Horvath, D. Pharmacophore-Based Virtual Screening. Methods in Molecular Biology 2010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korshavn, K.J.; Jang, M.; Kwak, Y.J.; Kochi, A.; Vertuani, S.; Bhunia, A.; Manfredini, S.; Ramamoorthy, A.; Lim, M.H. Reactivity of Metal-Free and Metal-Associated Amyloid-beta with Glycosylated Polyphenols and Their Esterified Derivatives. Sci Rep 2015, 5, 17842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Target | Shape and Colour | Shape and Electrostatics |

|---|---|---|

| 1-Histone Deacetylase 8 Inhibitors (8b and 20a) | 8b-2 rounds 20a-2 rounds |

8b-2 rounds 20a-2 rounds |

| 2-Bromodomain Inhibitors (JQ1 and I-BET762) | JQ1-2 rounds I-BET-762-3 rounds |

JQ1-2 rounds I-BET-762-3 rounds |

| 3-HH inhibitors (BMS-833923 and Vismodegib) | BMS-833923- 2 rounds Vismodegib-2 rounds |

BMS-833923- 2 rounds Vismodegib-2 rounds |

| 4-Tropomyosin Receptor Kinase Inhibitors (GW441759 and 10) | GW441759-2 rounds Compound 10- 2 rounds |

GW441759-2 rounds Compound 10- 2 rounds |

| HDACIs (n=9) | BRDI (n=8) | HH (n=10) | TRK (n=8) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cluster 22, 1 of 22 | Cluster 3, 1 of 3 | Cluster 4, 1 of 1 | Cluster 12, 1 of 6 |

| Cluster 21, 1 of 11 | Cluster 25, 1 of 12 | Cluster 8, 1 of 1 | Cluster 4, 1 of 5 |

| Cluster 16,1 of 65 | Cluster 16, 1 of 2 | Cluster 1, 1 of 3 | Cluster 8, 1 of 19 |

| Cluster 23, 1 of 1 | Cluster 15, 1 of 2 | Cluster 9, 1 of 1 | Cluster 9, 1 of 4 |

| Cluster 1, 1 of 26 | Cluster 4, 1 of 4 | Cluster 8, 1 of 29 | Cluster 25, 1 of 8 |

| Cluster 7, 1 of 26 | Cluster 24, 1 of 7 | Cluster 21, 1 of 99 | Cluster 12, 1 of 49 |

| Cluster 4, 1 of 28 | Cluster 23, 1 of 1 | Cluster 15, 1 of 6 | Cluster 7, 1 of 11 |

| Cluster 10, 1 of 86 | Cluster 10, 1 of 1 | Cluster 23, 1 of 1 | Cluster 25, 1 of 8 |

| Cluster 12, 1 of 50 | Cluster 17, 1 of 1 | ||

| Cluster 20, 1 of 12 |

| HDACIs (n=2) | BRDI (n=2) | HH (n=2) | TRK (n=2) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cluster 22, 1 of 22 | Cluster 3, 1 of 3 | Cluster 8, 1 of 1 | Cluster 25, 1 of 8 |

| Cluster 10, 1 of 86 | Cluster 16, 1 of 2 | Cluster 8, 1 of 29 | Cluster 12, 1 of 49 |

| Clusters | Bioconcentration Factor1 | Mutagenicity2 | Oral rat LD50-Log10(mol/kg)3 | T. Pyriformis IGC50 (48 hrs)mg/L4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cluster 22, 1 of 22 | 0.31 | Positive | 1.78 | 3845.78 |

| Cluster 10, 1 of 86 | 5.56 | Positive | 2.67 | 173.52 |

| Cluster 3, 1 of 3 | 12.71 | Positive | 2.52 | 4.61 |

| Cluster 16, 1 of 2 | 46.62 | Negative | 2.66 | 1.91 |

| Cluster 8, 1 of 1 | 27.88 | Negative | 1.70 | 6.33 |

| Cluster 8, 1 of 29 | 8.62 | N/A | 2.52 | N/A |

| Cluster 25, 1 of 8 | 98.26 | Positive | 2.01 | 6.55 |

| Cluster 12, 1 of 49 | 308.45 | Negative | 2.41 | 6.46 |

| 20A | 9.94 | Positive | N/A | 36.39 |

| 8B | 5.14 | Positive | N/A | 29.50 |

| BET-762 | 22.21 | Negative | 2.26 | 2.27 |

| JQ1 | 235.52 | Negative | 2.45 | 0.73 |

| Vesmodigib | 28.48 | Negative | 2.13 | 2.87 |

| BMS-833923 | 11.53 | Positive | 2.38 | N/A |

| Compound Z9 | 25.14 | Positive | 2.20 | 42.96 |

| Compound 10 | 20.85 | Positive | 2.65 | 7.04 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).