Submitted:

31 March 2025

Posted:

02 April 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

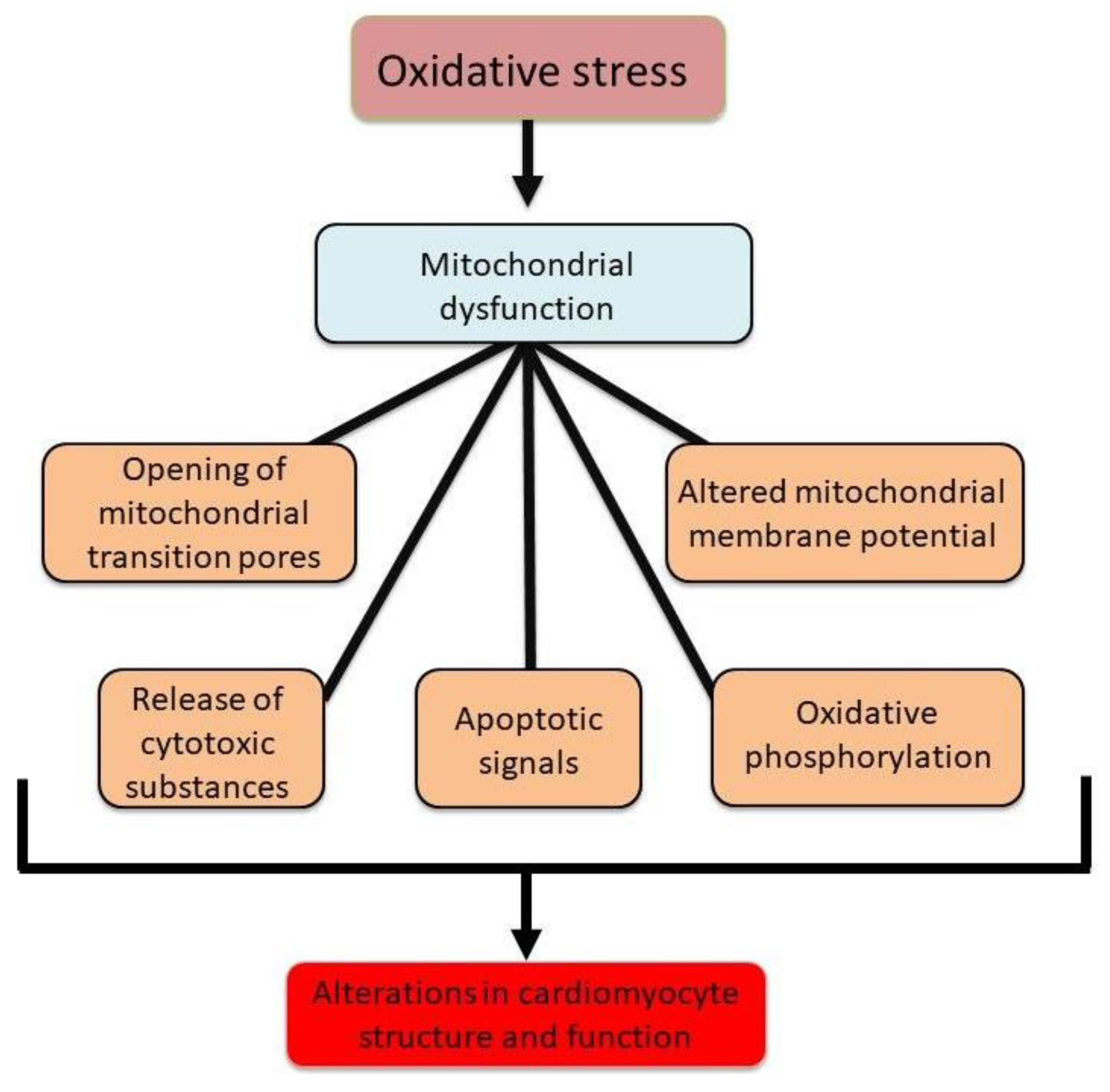

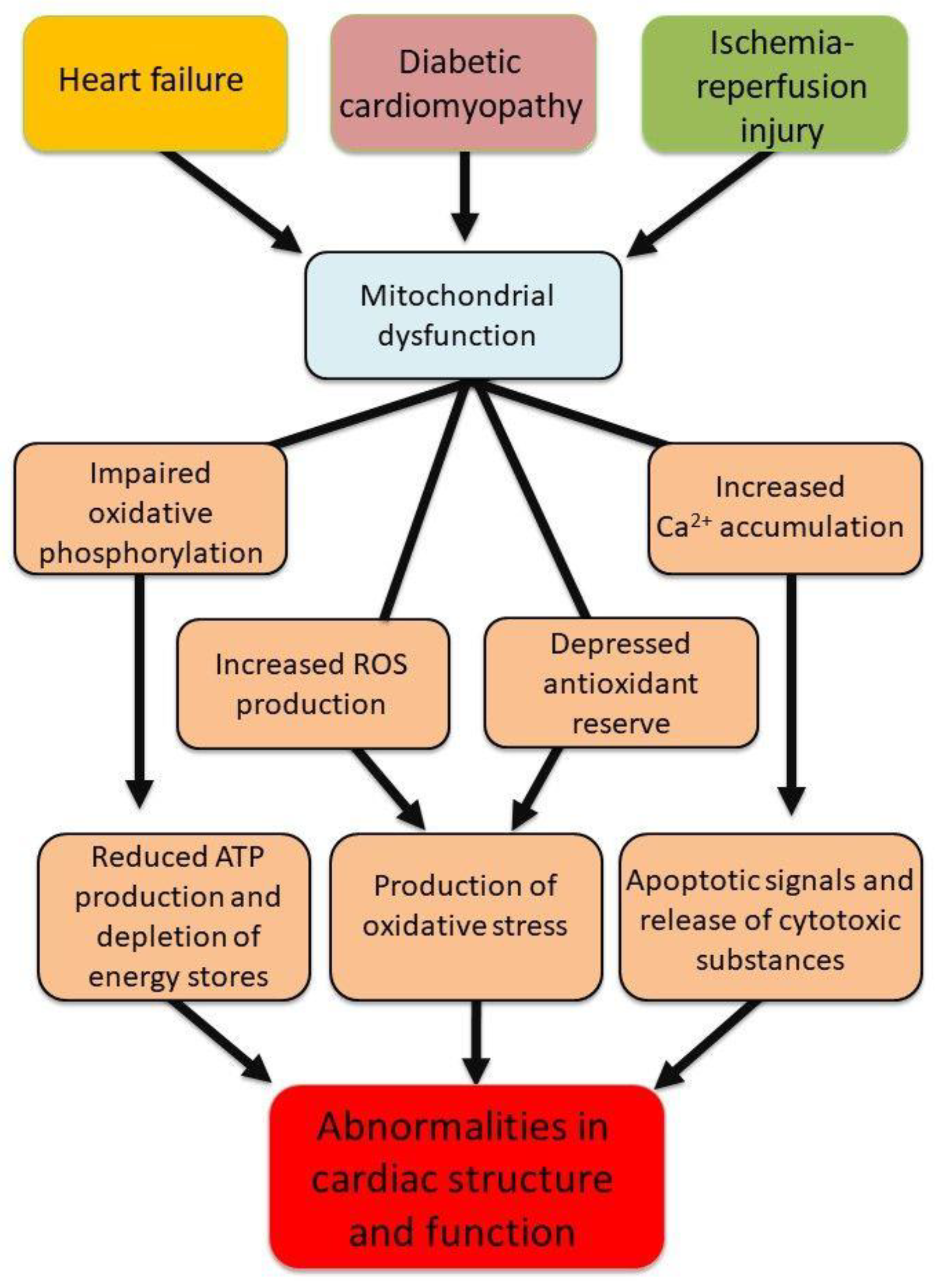

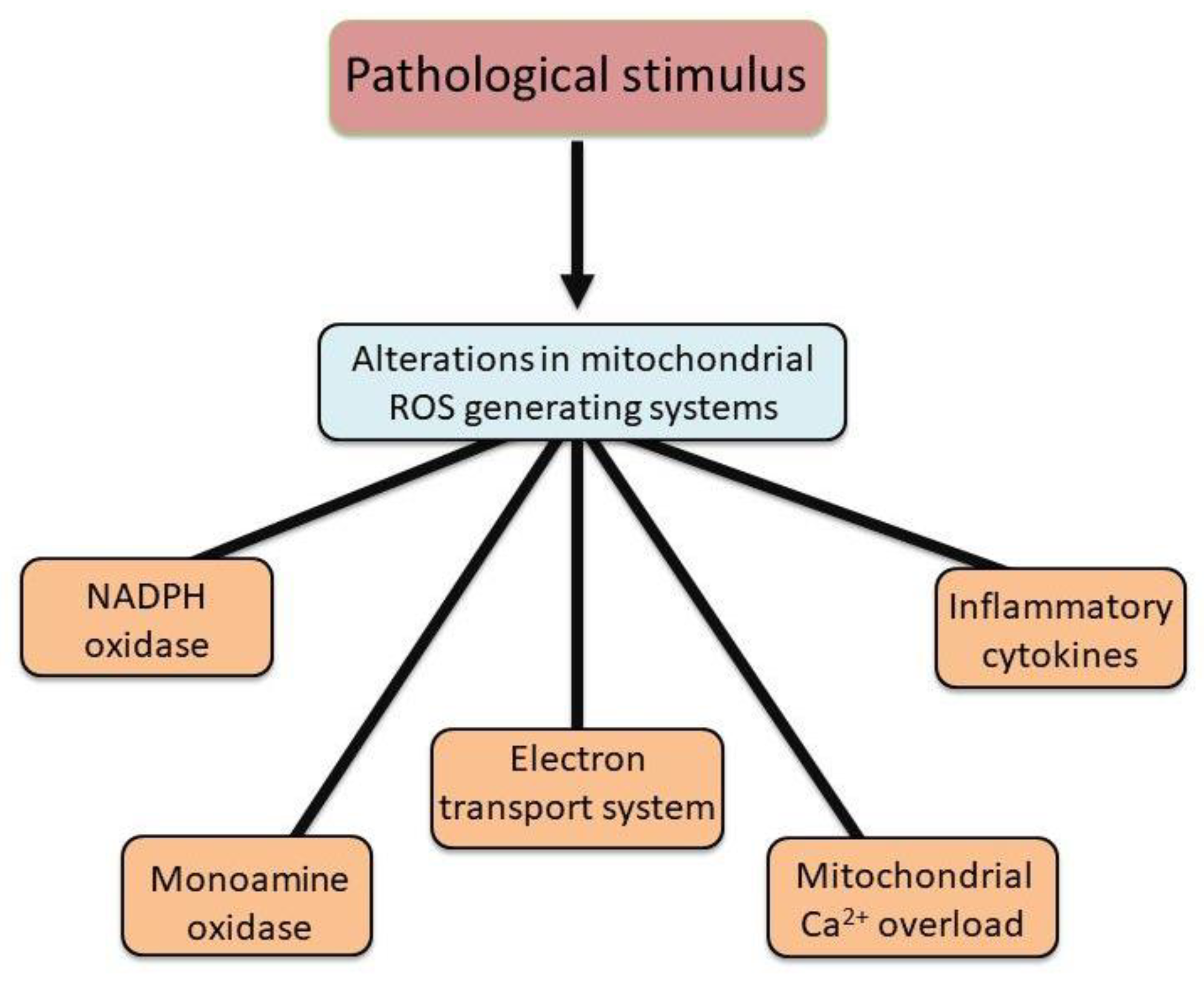

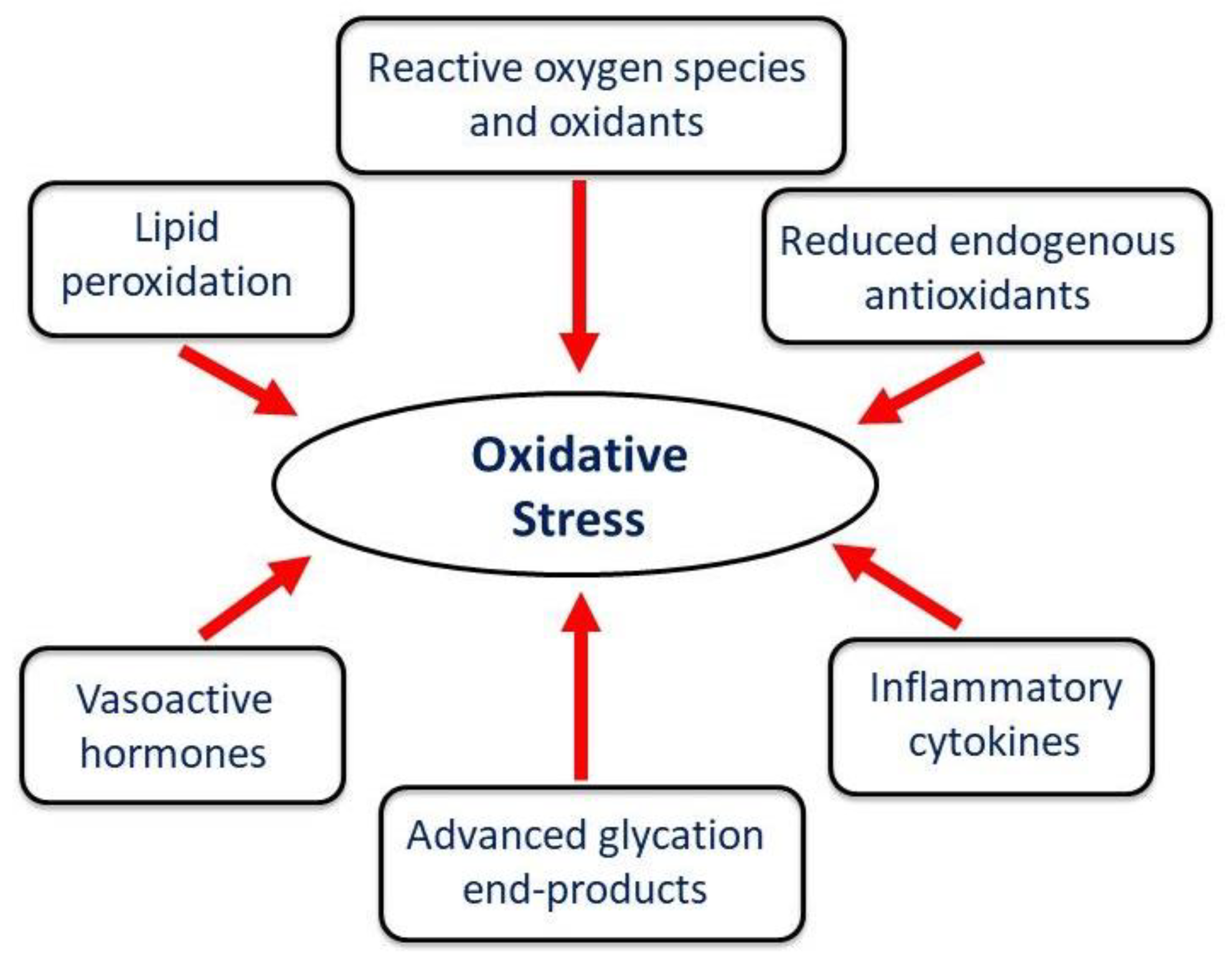

2. Evidence of Involvement of ROS and Ca2+-Overload in Cardiac Mitochondria

3. Development of Mitochondrial Ca2+-Overload due to Oxidative Stress

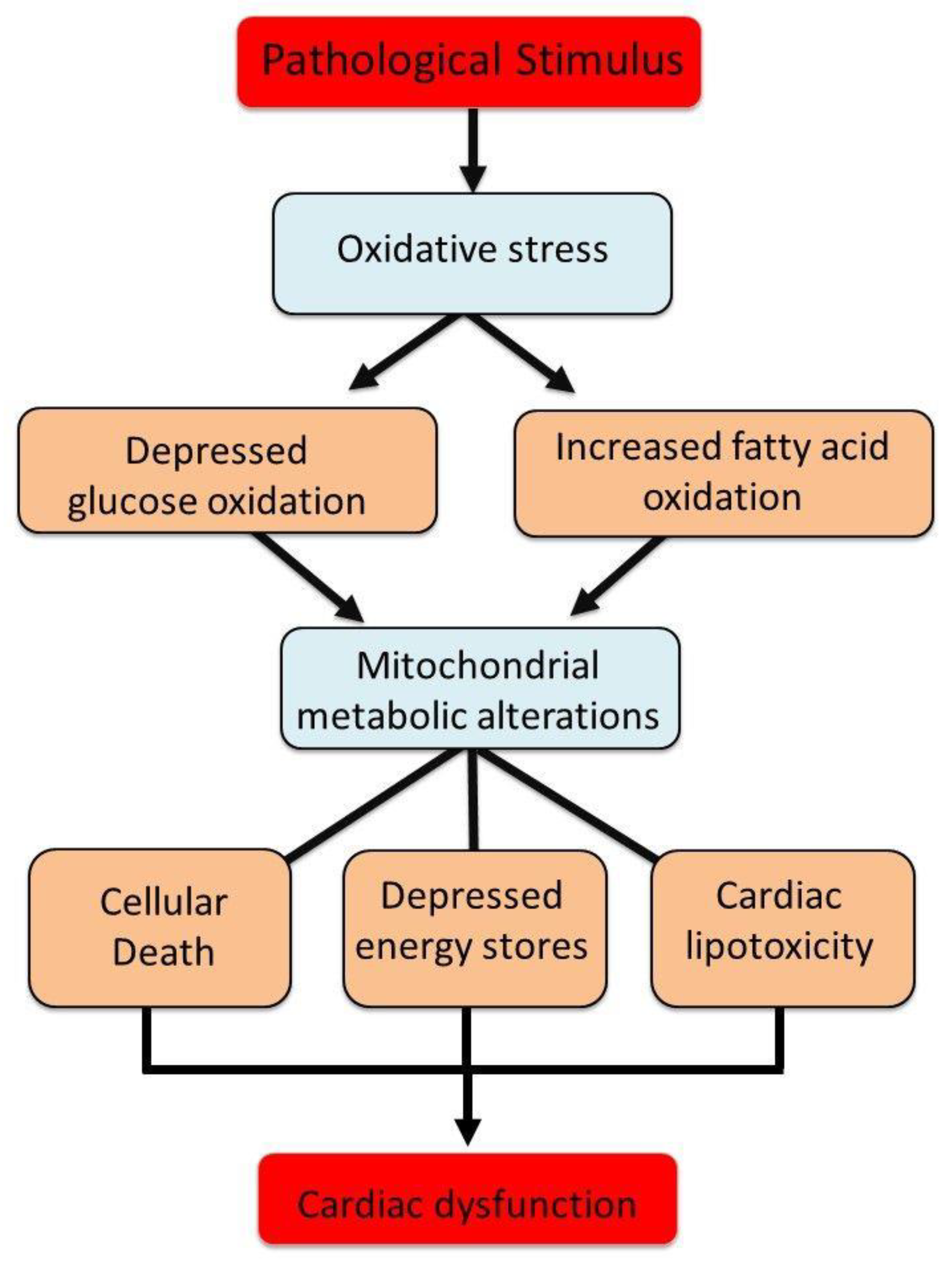

4. Mitochondrial Metabolic Alterations and Mitochondrial Dynamics

5. Novel Interventions Targeting Mitochondria in Different Cardiac Pathologies

6. Conclusion

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Bolli, R.; Marban, E. Molecular and cellular mechanisms of myocardial stunning. Physiol Rev 1999, 79, 609–634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolli, R.; Jeroudi, M.O.; Patel, B.S.; Aruoma, O.I.; Halliwell, B.; Lai, E.K.; McCay, P.B. Marked reduction of free radical generation and contractile dysfunction by antioxidant therapy begun at the time of reperfusion. Evidence that myocardial “stunning” is a manifestation of reperfusion injury. Circ Res 1989, 65, 607–622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dhalla, N.S.; Elmoselhi, A.B.; Hata, T.; Makino, N. Status of myocardial antioxidants in ischemia-reperfusion injury. Cardiovasc Res 2000, 47, 446–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jennings, R.B.; Reimer, K.A. The cell biology of acute myocardial ischemia. Annu Rev Med 1991, 42, 225–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Piper, H.M.; Meuter, K.; Schafer, C. Cellular mechanisms of ischemia reperfusion injury. Ann Thorac Surg 2003, 75, S644–S648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dridi, H.; Santulli, G.; Bahlouli, L.; Miotto, M.C.; Weninger, G.; Marks, A.R. Mitochondrial calcium overload plays a causal role in oxidative stress in the failing heart. Biomolecules 2023, 13, 1409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhalla, N.S.; Ostadal, P.; Tappia, P.S. Involvement of oxidative stress and antioxidants in modification of cardiac dysfunction due to ischemia-reperfusion injury. Antioxidants 2025, 14, 340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhalla, N.S.; Elimban, V.; Bartekova, M.; Adameova, A. Involvement of oxidative stress in the development of subcellular defects and heart disease. Biomedicines 2022, 10, 393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kukreja, R.C.; Weaver, A.B.; Hess, M.L. Sarcolemmal Na-K-ATPase: inactivation by neutrophil-derived free radicals and oxidants. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 1990, 259, H1330–H1336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ostadal, P.; Elmoselhi, A.B.; Zdobnicka, I.; Lukas, A.; Elimban, V.; Dhalla, N.S. Role of oxidative stress in ischemia-reperfusion-induced changes in Na-K ATPase isoform expression in rat heart. Antioxid Redox Signal 2004, 6, 914–923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saini, H.K.; Dhalla, N.S. Defective calcium handling in cardiomyocytes isolated from hearts subjected to ischemia-reperfusion. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 2005, 288, H2260–H2270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saini, H.K.; Elimban, V.; Dhalla, N.S. Attenuation of extracellular ATP response in cardiomyocytes isolated from hearts subjected to ischemia reperfusion. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 2005, 289, H614–H623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Temsah, R.M.; Netticadan, T.; Chapman, D.; Takeda, S.; Mochizuki, S.; Dhalla, N.S. Alterations in sarcoplasmic reticulum function and gene expression in ischemic reperfused rat heart. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 1999, 277, H584–H594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zucchi, R.; Ronca-Testoni, S.; Yu, G.; Galbani, P.; Ronca, G.; Mariani, M. Effect of ischemia and reperfusion on cardiac ryanodine receptors sarcoplasmic reticulum Ca2+ channels. Circ Res 1994, 74, 271–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferrari, R. The role of mitochondria in ischemic heart disease. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol 1996, 28 Suppl 1, S1–S10. [Google Scholar]

- Lesnefsky, E.J.; Moghaddas, S.; Tandler, B.; Kerner, J.; Hoppel, C.L. Mitochondrial dysfunction in cardiac disease: ischemia-reperfusion, aging, and heart failure. J Mol Cell Cardiol 2001, 33, 1065–1089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Williamson, J.R. Mitochondrial function in the heart. Annu Rev Physiol 1979, 41, 485–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhullar, S.K.; Dhalla, N.S. Status of mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation during the development of heart failure. Antioxidants 2023, 12, 1941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giorgi, C.; Marchi, S.; Pinton, P. The machineries, regulation and cellular functions of mitochondrial calcium. Nat. Rev. Mol Cell Biol 2018, 19, 713–730. [Google Scholar]

- Lopez-Crisosto, C.; Pennanen, C.; Vasquez-Trincado, C.; Morales, P.E.; Bravo-Sagua, R.; Quest, A.F.G.; Chiong, M.; Lavandero, S. Sarcoplasmic reticulum–mitochondria communication in cardiovascular pathophysiology. Nat Rev Cardiol 2017, 14, 342–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bravo-San Pedro, J.M.; Kroemer, G.; Galluzzi, L. Autophagy and mitophagy in cardiovascular disease. Circ Res 2017, 120, 1812–1824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Budde, H.; Hassoun, R.; Tangos, M.; Zhazykbayeva, S.; Herwig, M.; Varatnitskaya, M.; Sieme, M.; Delalat, S.; Sultana, I.; Kolijn, D.; et al. The interplay between S-glutathionylation and phosphorylation of cardiac troponin I and myosin binding protein C in end-stage human failing hearts. Antioxidants 2021, 10, 1134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leichert, L.I.; Gehrke, F.; Gudiseva, H.V.; Blackwell, T.; Ilbert, M.; Walker, A.K.; Strahler, J.R.; Andrews, P.C.; Jakob, U. Quantifying changes in the thiol redox proteome upon oxidative stress in vivo. Proc Natl Acad Sci 2008, 105, 8197–8202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delbridge, L.M.D.; Mellor, K.M.; Taylor, D.J.; Gottlieb, R.A. Myocardial stress and autophagy: Mechanisms and potential therapies. Nat Rev Cardiol 2017, 14, 412–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ballinger, S.W. Mitochondrial dysfunction in cardiovascular disease. Free Radic Biol Med 2005, 38, 1278–1295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tani, M. Effects of anti-free radical agents on Na, Ca2+, and function in reperfused rat hearts. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 1990, 259, H137–H143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mialet-Perez, J.; Parini, A. Cardiac monoamine oxidases: at the heart of mitochondrial dysfunction. Cell Death Dis 2020, 11, 54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrari, R.; Pedersini, P.; Bongrazio, M.; Gaia, G.; Bernocchi, P.; Di Lisa, F.; Visioli, O. Mitochondrial energy production and cation control in myocardial ischaemia and reperfusion. Basic Res Cardiol 1993, 88, 495–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Long, X.; Goldenthal, M.J.; Wu, G.M.; Marin-Garcia, J. Mitochondrial Ca2+-flux and respiratory enzyme activity decline are early events in cardiomyocyte response to H2O2. J Mol Cell Cardiol 2004, 37, 63–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stevenson, M.D.; Canugovi, C.; Vendrov, A.E.; Hayami, T.; Bowles, D.E.; Krause, K.H.; Madamanchi, N.R.; Runge, M.S. NADPH oxidase 4 regulates inflammation in ischemic heart failure: Role of soluble epoxide hydrolase. Antioxid Redox Signal 2019, 31, 39–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Landmesser, U.; Spiekermann, S.; Preuss, C.; Sorrentino, S.; Fischer, D.; Manes, C.; Mueller, M.; Drexler, H. Angiotensin II induces endothelial xanthine oxidase activation: role for endothelial dysfunction in patients with coronary disease. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 2007, 27, 943–948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dia, M.; Gomez, L.; Thibault, H.; Tessier, N.; Leon, C.; Chouabe, C.; Ducreux, S.; Gallo-Bona, N.; et al. Reduced reticulum-mitochondria Ca2+ transfer is an early and reversible trigger of mitochondrial dysfunctions in diabetic cardiomyopathy. Basic Res Cardiol 2020, 115, 74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stowe, D.F.; Camara, A.K.S. Mitochondrial reactive oxygen species production in excitable cells: Modulators of mitochondrial and cell function. Antioxid Redox Signal 2009, 11, 1373–1414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marí, M.; Morales, A.; Colell, A.; García-Ruiz, C.; Fernández-Checa, J.C. Mitochondrial glutathione, a key survival anti-oxidant. Antioxid Redox Signal 2009, 11, 2685–2700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scialò, F.; Sriram, A.; Stefanatos, R.; Spriggs, R.V.; Loh, S.H.Y.; Martins, L.M.; Sanz, A. Mitochondrial complex I derived ROS regulate stress adaptation in Drosophila melanogaster. Redox Biology, 2020, 32, 101450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, H.; Dhalla, N.S. The Role of pro-inflammatory cytokines in the pathogenesis of cardiovascular disease. Int J Mol Sci 2024, 25, 1082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hori, M.; Nishida, K. Oxidative stress and left ventricular remodelling after myocardial infarction. Cardiovasc Res 2009, 81, 457–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, H.; Han, J.; Dmitrii, G.; Zhang, X.A. Potential targets of natural products for improving cardiac ischemic injury: The role of Nrf2 signaling transduction. Molecules 2024, 29, 2005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, F.; Yan, C.; Patel, R.; Liu, W.; Dong, E. Vitamins C and E attenuates apoptosis, β-adrenergic receptor desensitization, and sarcoplasmic reticular Ca2+ ATPase downregulation after myocardial infarction. Free Radic Biol Med 2006, 40, 1827–1842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shao, Q.; Ren, B.; Elimban, V.; Tappia, P.S.; Takeda, N.; Dhalla, N.S. Modification of sarcolemmal Na+-K+-ATPase and Na+/Ca2+ exchanger in heart failure by blockade of renin-angiotensin system. Am J Heart Physiol Circ Physiol 2005, 288, H2637–H2646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.; Pogwizd, S.M.; Prabhu, S.D.; Zhou, L. Inhibiting Na+-K+ ATPase can impair mitochondrial energetics and induce abnormal Ca2+ cycling and automaticity in guinea pig cardiomyocytes. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e93928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Crow, M.T.; Mani, K.; Nam, Y.J.; Kitsis, R.N. The mitochondrial death pathway and cardiac myocyte apoptosis. Circ Res 2004, 95, 957–970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bertero, E.; Popoiu, T.A.; Maack, C. Mitochondrial calcium in cardiac ischemia/reperfusion injury and cardioprotection. Basic Res Cardiol 2024, 119, 569–585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grancara, S.; Ohkubo, S.; Artico, M.; Ciccariello, M.; Manente, S.; Bragadin, M.; Toninello, A.; Agostinelli, E. Milestones and recent discoveries on cell death mediated by mitochondria and their interactions with biologically active amines. Amino Acids 2016, 48, 2313–2326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morciano, G.; Pinton, P. Modulation of mitochondrial permeability transition pores in reperfusion injury: Mechanisms and therapeutic approaches. Eur J Clin Invest 2025, 55, e14331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Circu, M.L.; Aw, T.Y. Reactive oxygen species, cellular redox systems, and apoptosis. Free Radic Biol Med 2010, 48, 749–762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferko, M.; Alanova, P.; Janko, D.; Opletalova, B.; Andelova, N. Mitochondrial peroxiredoxins and monoamine oxidase-A: Dynamic regulators of ROS signaling in cardioprotection. Physiol Res 2024, 73, 887–900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Popoiu TA, Maack, C., Bertero, E. Mitochondrial calcium signaling and redox homeostasis in cardiac health and disease. Front Mol Med 2023, 3, 1235188. [CrossRef]

- Tappia, P.S.; Dent, M.R.; Dhalla, N.S. Oxidative stress and redox regulation of phospholipase D in myocardial disease. Free Radic Biol Med 2006, 41, 349–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

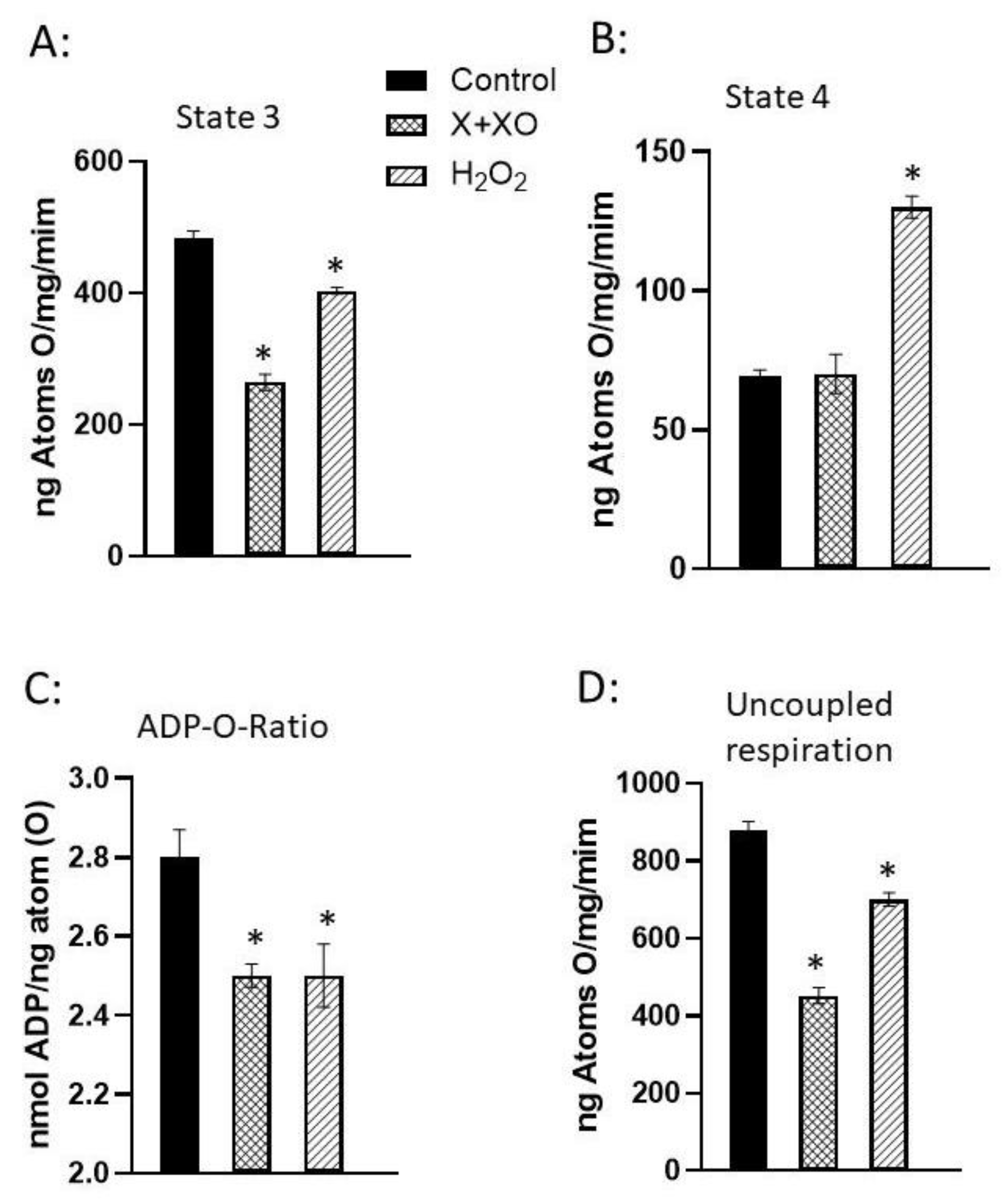

- Makazan, Z.; Saini, H.K.; Dhalla, N.S. Role of oxidative stress in alterations of mitochondrial function in ischemic-reperfused hearts. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 2007, 292, H1986–H1994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Takeda, S.; Mochizuki, S.; Jindal, R.; Dhalla, N.S. Mechanisms of hydrogen peroxide-induced increase in intracellular calcium in cardiomyocytes. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol Ther 1999, 4, 41–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, C.; Chang, X.; Zhao, D.; He, Y.; Dong, G.; Gao, L. Mitochondria and myocardial ischemia/reperfusion injury: Effects of Chinese herbal medicine and the underlying mechanisms. J Pharm Anal 2025, 15, 101051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, R.; Chen, X.; Li, X.; Wang, K. Molecular therapy of cardiac ischemia-reperfusion injury based on mitochondria and ferroptosis. J Mol Med 2023, 101, 1059–1071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cortassa, S.; Juhaszova, M.; Aon, M.A.; Zorov, D.B.; Sollott, S.J. Mitochondrial Ca2+, redox environment and ROS emission in heart failure: Two sides of the same coin? J Mol Cell Cardiol 2021, 151, 113–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pavez-Giani, M.G.; Sanchez-Aguilera, P.I.; Bomer, n.; Miyamota, S.; Booij, H.G.; Giraldo, P.; Oberdorf-Maass, S.U.; Nijholt, K.T.; Yurista, S.R.; Milting, H.; et al. ATPase inhibitory factor-1 disrupts mitochondrial Ca2+ handling and promotes pathological cardiac hypertrophy through CaMKIIδ. Int J Mol Sci 2021, 22, 4427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bertero, E.; Nickel, A.; Kohlhaas, M.; Hohl, M.; Sequeira, V.; Brune, C.; Schwemmlein, J.; Abeber, M.; Schuh, K.; Kutschka, I.; et al. Loss of mitochondrial Ca2+ uniporter limits inotropic reserve and provides trigger and substrate for arrhythmias in Barth syndrome cardiomyopathy. Circulation 2021, 144, 1694–1713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donoso, P.; Sanchez, G.; Bull, R.; Hidalgo, C. Modulation of cardiac ryanodine receptor activity by ROS and RNS. Front Biosci 2011, 16, 553–567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tokuhisa, T.; Yano, M.; Obayashi, M.; Noma, T.; Mochizuki, M.; Oda, T.; Okuda, S.; Doi, M.; Liu, J.; Ikeda, Y.; et al. AT1 receptor antagonist restores cardiac ryanodine receptor function, rendering isoproterenol-induced failing heart less susceptible to Ca2+-leak induced by oxidative stress. Circ J 2006, 70, 777–786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murphy, E.; Eisner, D.A. How does mitochondrial Ca2+ change during ischemia and reperfusion? Implications for activation of the permeability transition pore. J Gen Physiol 2025, 157, e202313520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamilton, S.; Terentyeva, R.; Clements, R.T.; Belevych, A.E.; Terentyev, D. Sarcoplasmic reticulum-mitochondria communication; implications for cardiac arrhythmia. J Mol Cell Cardiol 2021, 156, 105–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morciano, G.; Rimessi, A.; Patergnani, S.; Vitto, V.A.M.; Danese, A.; Kahsay, A.; Palumbo, L.; Bonora, M.; et al. Calcium dysregulation in heart diseases: Targeting calcium channels to achieve a correct calcium homeostasis. Pharmacol Res 2022, 177, 106119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Diaz-Juarez, J.; Suarez, J.; Cividini, F.; Scott, B.T.; Diemer, T.; Dai, A.; Dillmann, W.H. Expression of the mitochondrial calcium uniporter in cardiac myocytes improves impaired mitochondrial calcium handling and metabolism in simulated hyperglycemia. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 2016, 311, C1005–C1013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uchi, J.; Ryu, S.Y.; Jhun, B.S.; Hurst, S.; Sheu, S.S. Mitochondrial ion channels/transporters as sensors and regulators of cellular redox signaling. Antiox Redox Signal 2014, 21, 987–1006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duchen, M.R. Roles of mitochondria in health and disease. Diabetes 2004, 53, S96–S102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pacher, P.; Csordás, G.; Hajnóczky, G. Mitochondrial Ca2+ signaling and cardiac apoptosis. Biol Signals Recept 2001, 10, 200–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Piamsiri, C.; Fefelova, N.; Pamarthi, S.H.; Gwathmey, J.K.; Chattipakorn, S.C.; Chattipakorn, N.; Xie, L.H. Potential roles of IP3 receptors and calcium in programmed cell death and implications in cardiovascular diseases. Biomolecules 2024, 14, 1334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhalla, N.S.; Temsah, R.M.; Netticadan, T. Role of oxidative stress in cardiovascular diseases. J Hypertens 2000, 18, 655–673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bell, E.L.; Klimova, T.A.; Eisenbart, J.; Moraes, C.T.; Murphy, M.P.; Budinger, G.S.; Chandel, N.S. The Qo site of the mitochondrial complex III is required for the transduction of hypoxic signaling via reactive oxygen species production. J Cell Biol 2007, 177, 1029–1036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stein, L.R.; Imai, S.-I. The dynamic regulation of NAD metabolism in mitochondria. Trends Endocrinol. Metab 2012, 23, 420–428. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, W.W.; Birsoy, K.; Mihaylova, M.M.; Snitkin, H.; Stasinski, I.; Yucel, B.; Bayraktar, E.C.; Carette, J.E.; Clish, C.B.; Brum-melkamp, T.R.; et al. Inhibition of ATPIF1 ameliorates severe mitochondrial respiratory chain dysfunction in mammalian cells. Cell Rep 2014, 7, 27–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wrogemann, K.; Nylen, E.G. Mitochondrial calcium overloading in cardiomyopathic hamsters. J Mol Cell Cardiol 1978, 10, 185–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dhalla, N.S.; Lee, S.-L.; Shah, K.R.; Elimban, V.; Suzuki, S.; Jasmin, G. Behaviour of subcellular organelles during the development of congestive heart failure in cardiomyopathic hamsters (UM-X7. 1). In Cardiomyopathic Heart; New York Raven Press Ltd.: New York, NY, USA, 1994; pp. 1–14. [Google Scholar]

- Siasos, G.; Tsigkou, V.; Kosmopoulos, M.; Theodosiadis, D.; Simantiris, S.; Tagkou, N.M.; Tsimpiktsioglou, A.; Stampouloglou, P.K.; Oikonomou, E.; Mourouzis, K.; et al. Mitochondria and cardiovascular diseases—From pathophysiology to treatment. Ann Transl Med 2018, 6, 256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Y.; Marcillat, O.; Giulivi, C.; Ernster, L.; Davies, K.J. The oxidative inactivation of mitochondrial electron transport chain components and ATPase. J Biol Chem 1990, 265, 16330–16336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Davis, R.E.; Williams, M. Mitochondrial function and dysfunction: An update. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 2012, 342, 598–607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Der Bliek, A.M.; Sedensky, M.M.; Morgan, P.G. Cell biology of the mitochondrion. Genetics 2017, 207, 843–871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murphy, E.; Ardehali, H.; Balaban, R.S.; DiLisa, F.; Dorn, G.W.; Kitsis, R.N.; Otsu, K.; Ping, P.; Rizzuto, R.; Sack, M.N.; et al. Mitochondrial function, biology, and role in disease: A scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Circ Res 2016, 118, 1960–1991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galluzzi, L.; Kepp, O.; Trojel-Hansen, C.; Kroemer, G. Mitochondrial control of cellular life, stress, and death. Circ Res 2012, 111, 1198–1207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williamson, J.R. Mitochondrial heart function. Ann Rev Physiol 1979, 41, 485–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mootha, V.K.; Bunkenborg, J.; Olsen, J.V.; Hjerrild, M.; Wisniewski, J.R.; Stahl, E.; Bolouri, M.S.; Ray, H.N.; Sihag, S.; Kamal, M.; et al. Integrated analysis of protein composition, tissue diversity, and gene regulation in mouse mitochondria. Cell 2003, 115, 629–640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collins, T.J.; Berridge, M.J.; Lipp, P.; Bootman, M.D. Mitochondria are morphologically and functionally heterogeneous within cells. EMBO J 2002, 21, 1616–1627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glatz, J.F.; Nabben, M.; Young, M.E.; Schulze, P.C.; Taegtmeyer, H.; Luiken, J.J. Re-balancing cellular energy substrate metabolism to mend the failing heart. Biochim Biophys Acta Mol Basis Dis 2020, 1866, 165579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stanley, W.C.; Recchia, F.A.; Lopaschuk, G.D. Myocardial substrate metabolism in the normal and failing heart. Physiol Rev 2005, 85, 1093–1129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taylor, S.W.; Fahy, E.; Zhang, B.; Glenn, G.M.; Warnock, D.E.; Wiley, S.; Murphy, A.N.; Gaucher, S.P.; Capaldi, R.A.; Gibson, B.W.; et al. Characterization of the human heart mitochondrial proteome. Nat Biotechnol 2003, 21, 281–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Q.; Sun, Q.; Zhou, L.; Liu, K.; Jiao, K. Complex Regulation of mitochondrial function during cardiac development. J Am Heart Assoc 2019, 8, e012731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pagliarini, D.J.; Rutter, J. Hallmarks of a new era in mitochondrial biochemistry. Genes Dev 2013, 27, 2615–2627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chandel, N.S. Mitochondria as signaling organelles. BMC Biol 2014, 12, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, B.; Tian, R. Mitochondrial dysfunction in pathophysiology of heart failure. J Clin Investig 2018, 128, 3716–3726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neubauer, S. The failing heart-an engine out of fuel. N Engl J Med 2007, 356, 1140–1151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bertero, E.; Maack, C. Metabolic remodelling in heart failure. Nat Rev Cardiol 2018, 15, 457–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ballinger, S.W. Mitochondrial dysfunction in cardiovascular disease. Free Radic Biol Med 2005, 38, 1278–1295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Guo, Q.; Feng, X.; Liu, Y.; Zhou, Y. Mitochondrial dysfunction in cardiovascular diseases: Potential targets for treatment. Front Cell Dev Biol 2022, 10, 841523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chistiakov, D.A.; Shkurat, T.P.; Melnichenko, A.A.; Grechko, A.V.; Orekhov, A.N. The role of mitochondrial dysfunction in cardiovascular disease: A brief review. Ann Med 2018, 50, 121–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calbet, J.A.L.; Martín-Rodríguez, S.; Martin-Rincon, M.; Morales-Alamo, D. An integrative approach to the regulation of mitochondrial respiration during exercise: Focus on high-intensity exercise. Redox Biol 2020, 35, 101478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rosca, M.G.; Hoppel, C.L. Mitochondrial dysfunction in heart failure. Heart Fail Rev 2013, 18, 607–622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schwarzer, M.; Rohrbach, S.; Niemann, B. Heart and mitochondria: Pathophysiology and implications for cardiac surgeons. Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 2018, 66, 11–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonora, M.; Wieckowski, M.R.; Sinclair, D.A.; Kroemer, G.; Pinton, P.; Galluzzi, L. Targeting mitochondria for cardiovascular disorders: Therapeutic potential and obstacles. Nat Rev Cardiol 2019, 16, 33–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borghetti, G.; von Lewinski, D.; Eaton, D.M.; Sourij, H.; Houser, S.R.; Wallner, M. Diabetic cardiomyopathy: Current and future therapies. Beyond glycemic control. Front Physiol 2018, 9, 1514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrara, D.; Montecucco, F.; Dallegri, F.; Carbone, F. Impact of different ectopic fat depots on cardiovascular and metabolic diseases. J Cell Physiol 2019, 234, 21630–21641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paolisso, P.; Bergamaschi, L.; Saturi, G.; D’Angelo, E.C.; Magnani, I.; Toniolo, S.; Stefanizzi, A.; Rinaldi, A.; Bartoli, L.; Angeli, F.; et al. Secondary prevention medical therapy and outcomes in patients with myocardial infarction with non-obstructive coronary artery disease. Front Pharmacol 2020, 10, 1606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.L.; Gao, P.; Zou, Y.Z. The relationship between mitochondrial oxidative stress and diabetic cardiomyopathy. Chin Clin. Pharmacol Therap 2021, 33, 1080–1085. [Google Scholar]

- Kaludercic, N.; Di Lisa, F. Mitochondrial ROS formation in the pathogenesis of diabetic cardiomyopathy. Front Cardiovasc Med 2020, 7, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Evangelista, I.; Nuti, R.; Picchioni, T.; Dotta, F.; Palazzuoli, A. Molecular dysfunction and phenotypic derangement in diabetic cardiomyopathy. Int J Mol Sci 2019, 20, 3264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Biala, A.K.; Dhingra, R.; Kirshenbaum, L.A. Mitochondrial dynamics: Orchestrating the journey to advanced age. J Mol Cell Cardiol 2015, 83, 37–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, X.; Li, Y.; Cai, C.; Wu, F.; He, J.; Zhang, Y.; Zhong, J.; Tan, Y.; Liu, R.; Zhu, H.; Zhou, H. Mitochondrial quality control mechanisms as molecular targets in diabetic heart. Metabolism 2022, 137, 155313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tokuyama, T.; Yanagi, S. Role of mitochondrial dynamics in heart diseases. Genes 2023, 14, 1876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, F.; Liang, T.; Lu, Y.W.; Fu, X.; Dong, X.; Pu, L.; Hong, T.; et al. A defect in mitochondrial protein translation influences mitonuclear communication in the heart. Nat Commun 2023, 14, 1595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gabillard-Lefort, C.; Thibault, T.; Lenaers, G.; Wiesner, R.J.; Mialet-Perez, J.; Baris, O.R. Heart of the matter: Mitochondrial dynamics and genome alterations in cardiac aging. Mech Ageing Dev 2025, 224, 112044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Liu, Y.; Dorn, G.W. 2nd. Mitochondrial fusion is essential for organelle function and cardiac homeostasis. Circ Res 2011, 109, 1327–1331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, Y.; Li, A.; Liu, B.; Jiang, W.; Gao, M.; Tian, X.; Gong, G. Mitochondrial fusion mediated by fusion promotion and fission inhibition directs adult mouse heart function toward a different direction. FASEB J 2020, 34, 663–675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jarreta, D.; Orús, J.; Barrientos, A.; Miró, O.; Roig, E.; Heras, M.; Moraes, C.T.; Cardellach, F.; Casademont, J. Mitochondrial function in heart muscle from patients with idiopathic dilated cardiomyopathy. Cardiovasc Res 2000, 45, 860–865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buchwald, A.; Till, H.; Unterberg, C.; Oberschmidt, R.; Figulla, H.R.; Wiegand, V. Alterations of the mitochondrial respiratory chain in human dilated cardiomyopathy. Eur Heart J 1990, 11, 509–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abel, E.D.; Doenst, T. Mitochondrial adaptations to physiological vs. pathological cardiac hypertrophy. Cardiovasc Res 2011, 90, 234–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bragoszewski, P.; Turek, M.; Chacinska, A. Control of mitochondrial biogenesis and function by the ubiquitin-proteasome system. Open Biol 2017, 7, 170007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berthiaume, J.M.; Kurdys, J.G.; Muntean, D.M.; Rosca, M.G. Mitochondrial NAD+/NADH redox state and diabetic cardiomyopathy. Antioxid Redox Signal 2019, 30, 375–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mongirdien, A.; Liuiz, A.; Karˇciauskait, D.; Mazgelyt, E.; Liekis, A.; Sadauskien, I. Relationship between oxidative stress and left ventricle markers in patients with chronic heart failure. Cells 2023, 12, 803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, A.K.; Bhullar, S.K.; Elimban, V.; Dhalla, N.S. Oxidative Stress as a mechanism for functional alterations in cardiac hypertrophy and heart failure. Antioxidants 2021, 10, 931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.Y.; Chen, D.; Watkins, S.C.; Feldman, A.M. Mitochondrial abnormalities in tumor necrosis factor-α–induced heart failure are associated with impaired DNA repair activity. Circulation 2001, 104, 2492–2497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozcan, C.; Bienengraeber, M.; Hodgson, D.M.; Mann, D.L.; Terzic, A. Mitochondrial tolerance to stress impaired in failing heart. J Mol Cell Cardiol 2003, 35, 1161–1166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabbah, H.N.; Sharov, V.; Riddle, J.M.; Kono, T.; Lesch, M.; Goldstein, S. Mitochondrial abnormalities in myocardium of dogs with chronic heart failure. J Mol Cell Cardiol 1992, 24, 1333–1347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ide, T.; Tsutsui, H.; Hayashidani, S.; Kang, D.; Suematsu, N.; Nakamura, K.-I.; Utsumi, H.; Hamasaki, N.; Takeshita, A. Mitochondrial DNA damage and dysfunction associated with oxidative stress in failing hearts after myocardial infarction. Circ Res 2001, 88, 529–535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sobel, B.E.; Spann, J.F., Jr.; Pool, P.E.; Sonnenblick, E.H.; Braunwald, E. Normal oxidative phosphorylation in mitochondria from the failing heart. Circ Res 1967, 21, 355–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sordahl, L.; McCollum, W.; Wood, W.; Schwartz, A.; Peterzan, M.A.; Lygate, C.A.; Neubauer, S.; Rider, O.J.; Gong, G.; Liu, J.; et al. Mitochondria and sarcoplasmic reticulum function in cardiac hypertrophy and failure. Am J Physiol Content 1973, 224, 497–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sack, M.N.; Rader, T.A.; Park, S.; Bastin, J.; McCune, S.A.; Kelly, D.P. Fatty acid oxidation enzyme gene expression is downregulated in the failing heart. Circulation 1996, 94, 2837–2842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabbah, H.N.; Gupta, R.C.; Kohli, S.; Wang, M.; Hachem, S.; Zhang, K. Chronic therapy with elamipretide (MTP-131), a novel mitochondria-targeting peptide, improves left ventricular and mitochondrial function in dogs with advanced heart failure. Circ Heart Fail 2016, 9, e002206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ayoub, I.M.; Radhakrishnan, J.; Gazmuri, R.J. Targeting mitochondria for resuscitation from cardiac arrest. Crit Care Med 2008, 36, S440–S446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rudokas, M.W.; McKay, M.; Toksoy, Z.; Eisen, J.N.; Bögner, M.; Young, L.H.; Akar, F.G. Mitochondrial network remodeling of the diabetic heart: implications to ischemia related cardiac dysfunction. Cardiovasc Diabetol 2024, 23, 261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ramachandra, C.J.A.; Hernandez-Resendiz, S.; Crespo-Avilan, G.E.; Lin, Y.H.; Hausenloy, D.J. Mitochondria in acute myocardial infarction and cardioprotection. EBioMedicine 2020, 57, 102884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bugger, H.; Pfeil, K. Mitochondrial ROS in myocardial ischemia reperfusion and remodeling. Biochim Biophys Acta Mol Basis Dis 2020, 1866, 165768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dongworth, R.K.; Hall, A.R.; Burke, N.; Hausenloy, D.J. Targeting mitochondria for cardioprotection: examining the benefit for patients. Future Cardiol 2014, 10, 255–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Owusu, F.B.; Wu, H.; Zhang, X.; Li, R.; Liu, Z.; Zhang, S.; Leng, L.; Wang, Q. Mitochondria as therapeutic targets for natural products in the treatment of cardiovascular diseases. J Ethnopharmacol 2025, 6, 119588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moe, G.W.; Marín-García, J. Role of cell death in the progression of heart failure. Heart Fail Rev 2016, 21, 157–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peart, J.N.; Gross, G.J. Sarcolemmal and mitochondrial KATP channels and myocardial ischemic preconditioning. J Cell Mol Med 2002, 6, 453–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Halestrap, A.P.; Clarke, S.J.; Javadov, S.A. Mitochondrial permeability transition pore opening during myocardial reperfusion--a target for cardioprotection. Cardiovasc Res 2004, 61, 372–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yellon, D.M.; Beikoghli Kalkhoran, S.; Davidson, S.M. The RISK pathway leading to mitochondria and cardioprotection: how everything started. Basic Res Cardiol 2023, 118, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halestrap, A.P. Calcium, mitochondria and reperfusion injury: a pore way to die. Biochem Soc Trans 2006, 34, 232–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rabinovich-Nikitin, I.; Kirshenbaum, L.A. Circadian regulated control of myocardial ischemia-reperfusion injury. Trends Cardiovasc Med 2024, 34, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Ponnusamy, M.; Dong, Y.; Zhang, L.; Wang, K.; Li, P. Effects of miRNAs on myocardial apoptosis by modulating mitochondria related proteins. Clin Exp Pharmacol Physiol 2017, 44, 431–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayashida, K.; Takegawa, R.; Shoaib, M.; Aoki, T.; Choudhary, R.C.; Kuschner, C.E.; Nishikimi, M.; Miyara, S.J.; et al. Mitochondrial transplantation therapy for ischemia reperfusion injury: a systematic review of animal and human studies. J Transl Med 2021, 19, 214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lotz, C.; Herrmann, J.; Notz, Q.; Meybohm, P.; Kehl, F. Mitochondria and pharmacologic cardiac conditioning-at the heart of ischemic injury. Int J Mol Sci 2021, 22, 3224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Z.; Tian, Y.; Liu, N.; Chen, Y.; Chen, X.; Yuan, G.; Chang, A.; Chang, X.; et al. Mitochondrial stress as a central player in the pathogenesis of hypoxia-related myocardial dysfunction: New insights. Int J Med Sci 2024, 21, 2502–2509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suarez, J.; Cividini, F.; Scott, B.T.; Lehmann, K.; Diaz-Juarez, J.; Diemer, T.; Dai, A.; Suarez, J.A.; et al. Restoring mitochondrial calcium uniporter expression in diabetic mouse heart improves mitochondrial calcium handling and cardiac function. J Biol Chem 2018, 293, 8182–8195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dillmann, W.H. Diabetic cardiomyopathy. Circ Res 2019, 124, 1160–1162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dhalla, N.S.; Mota, K.O.; Elimban, V.; Shah, A.K.; de Vasconcelos, C.M.L.; Bhullar, S.K. Role of vasoactive hormone-induced signal transduction in cardiac hypertrophy and heart failure. Cells 2024, 13, 856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, T.; Wang, N.; Yi, D.; Xiao, Y.; Li, X.; Shao, B.; Wu, Z.; Bai, J.; Shi, X.; Wu, C.; et al. ROS-mediated ferroptosis and pyroptosis in cardiomyocytes: An update. Life Sci 2025, 123565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daiber, A.; Hahad, O.; Andreadou, I.; Steven, S.; Daub, S.; Münzel, T. Redox-related biomarkers in human cardiovascular disease - classical footprints and beyond. Redox Biol 2021, 42, 101875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhullar, S.K.; Dhalla, N.S. Angiotensin II-induced signal transduction mechanisms for cardiac hypertrophy. Cells 2022, 11, 3336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| ADP-to-O Ratio (nmol ADP/ ng atom O) | Uncoupled Respiration (ng atoms O/min/mg protein) | |

|---|---|---|

| A. X+XO Effects | ||

| Control | 3.0.6±0.15 | 575±9 |

| X+XO | 2.55±0.07* | 196±7* |

| X+XO+SOD+CAT | 2.81±2.0.04# | 426±30*# |

| B. H2O2 Effects | ||

| Control | 3.13±0.09 | 543±29 |

| H2O2 | 2.37±0.03* | 153±5* |

| H2O2+CAT | 2.52±0.04* | 170±7* |

| H2O2+CAT+MAN | 2.84±0.11# | 195±12*# |

| Increase in [Ca2+]i in cardiomyocytes (% of control) |

|

|---|---|

|

A. H2O2-induced [Ca2+]i Control |

100 |

| 0.25 mM | 141±11* |

| 0.5 mM | 168±17* |

| 0.75 mM | 216±12* |

| 1.0 mM | 240±23* |

|

B. Antioxidants on H2O2-induced [Ca2+]i Control |

52.8±4.7 |

| CAT | 14.6±2.0* |

| MAN | 48.9±5.6 |

| CAT+MAN | 8.7±2.5* |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).