Introduction

In recent years increasing rates of stress, depression and suicidal behaviour have been reported in society as a whole [

1,

2,

3]. Destatis, the Federal Statistical Office of Germany, reported over 9000 deaths by suicide in the year 2019, which represents roughly three times the number of road accident fatalities [

4]. On a global scale, suicide poses a similarly important role, as over 800000 suicides are committed each year resulting in the second leading cause of death for 15 – 29-year-olds in the year of 2012 [

5,

6,

7]. A subset of 3 to 15% of suicides are attempted or completed by jumping from a height. [

8,

9]. This has led to research in the field of trauma surgery on these specific types of traumata, looking for correlations between trauma mechanisms and injury patterns. [

10,

11,

12]. A specific fracture of the os sacrum has been classified into four subgroups and is known as the "suicide jumper's fracture". [

13,

14]. Another distinctly observed injury sustained from jumping from height is the (bilateral) calcaneus fracture which can be classified by Sanders et al. [

15,

16,

17]. This injury is relevant and specific to this mechanism of trauma because most falls are suspected to hit with the heels first [

18,

19,

20,

21,

22]. Many of these high-force blunt traumas caused by falls from great heights are characterized as polytraumas and require a high level of care and are therefore primarily treated in Level 1 trauma centers.

Polytrauma, which can be scored using the Injury Severity Index, is defined by an injury or combination of injuries that can be life-threatening to the patient [

23]. The thorough examination by the paramedics under consideration of the trauma mechanism is important in the pre-clinical and intra-clinical evaluation and treatment of these patients. Only by identifying these high energy traumata, the correct diagnostical steps can be undertaken to identify life threatening conditions and treat them correctly as shown by Scheidt et al. [

24,

25]. Self-inflicted harm in suicidal jumps presents additional challenges for treating physicians. Patients who have jumped with suicidal intent may have done so in a location that is difficult for paramedics to reach, or where a significant amount of time passes before paramedics are even alerted. This becomes an obvious problem in the winter months, when the patient may suffer severe hypothermia before any medical care is provided [

26]. Adding to the challenges in treatment is the fact that informed consent often cannot be achieved because suicidal patients are unable to understand the risks and consequences of the surgical treatments that need to be undertaken. This means that only critical, emergency medical care can be provided. A legal guardian is not immediately available in most cases and surgical treatment may so be delayed [

27]. The treating physician will therefore need to schedule appointments with the legal guardian or the patients’ family members, which poses further effort. A signed informed consent via a fax machine, which would be in line with German privacy laws, is not readily available due to the infrequent use of this technology in other aspects of life [

28]. These hurdles can influence the outcome of this specific polytrauma group in a delaying, possibly negative way with complication rates up to 50% [

22,

29]. It is our goal to analyse the specific injury patterns, inflammatory response, and complication rates of suicidal patients in comparison to work associated injuries sustained from falls. Additionally, the goal was to to extrapolate if any correlation between jump height and injury patterns can be observed.

Material & Methods

A retrospective case analysis was conducted through the hospitals database between 2014 and 2024. Therefore, a manual admission tracking was performed to patients with an expressed suicidal intent, or when suicidal intent was reported by bystanders and the patient had jumped to self-harm themselves.

For the work or recreational activity related falls the inclusion criteria was a fall from 3 meters or above, as this was also the minimum height recorded in suicidal jumps. The injuries found during the physical and radiological examinations were summarized in a table with respect to the height of the fall if this information was available. The radiological exams were assessed by a specialist for radiology and traumatology in each case. The injuries were then further classified following the injury severity score which is used in the German polytrauma guidelines [

23,

30]. Due to limited information provided by some patients and/or the emergency doctor not all patients could be subdivided in this category. If suicidal intent was not clearly documented, patients were not included in the suicidal group. No age restrictions applied. Furthermore, the patient’s inflammatory response in form of c-reactive protein, white blood cell count, lactate, and base excess were analysed. If available, albumin and vitamin D levels were noted to approximate the nutritional status of the patient upon arrival at the hospital. Lastly, the time of the admission was documented. The times were differentiated between weekdays and weekends as well as admission during day shift (7:00 – 16:00 o´clock during weekdays and 9:00 – 18:00 o´clock during weekends) and on call staff admissions.

A positive ethics approval was obtained before conducting this study (323-23-EP). The study was conducted in accordance with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki.

Chat GPT was used for language improvement and general manuscript revision. After using this tool, the authors reviewed and edited the content as needed and take full responsibility for the publication’s content.

Statistical Analysis

Data were compiled using Microsoft Excel 2024 (Microsoft Corporation, Richmond, VA, USA). For the statistical analysis, SPSS Statistics version 28 for Windows (SPSS, Inc., an IBM company, Chicago, IL, USA) was used. Descriptive statistics were calculated, including arithmetic means, standard deviations, and ranges. Numerical variables were expressed as mean (M) ± standard deviation (SD). An alpha error of 5% was considered statistically significant. Chi-squared test with Cramers V was used to test for associations between nominal variables. For the analysis of correlating variables, Spearman´s rank correlation coefficient was used. For naturally distributed, continuous variables (tested through Shapiro-Wilk-Test) p value were calculated using an unpaired, two tailed t-test. For non-naturally distributed data, the Mann-Whitney-U-test was employed. In order to obtain meaningful results, the odds ratio (confidence interval, CI) was analyzed to quantify the strength of the association between two variables.

Results

A total of 68 patients with a fall from height with suicidal intent (Male = 34, Female = 34) have been included in the final analysis. Sixty-eight patients which had fallen from great height unintentionally either work related or during recreational activity (unintentional group) were then compared to these suicidal patients. This unintentional group consisted of 52 male and 16 female patients with significantly more men observed (p = 0.002). On average, the suicidal group was 42.12 years old (± 17.75) with a minimum age of 15 and a maximum age of 88 years. Compared to this, the unintentional group was, on average, 42.07 years old (± 20.53) with a minimum age of 5 and a maximum age of 94 years. Furthermore, the suicidal group jumped from an average of 9.61 m (± 6.42) compared to the 6.14 m (± 4.08) on average in the unintentional group (p < 0.001). The demographic data regarding both groups is mentioned in

Table 1.

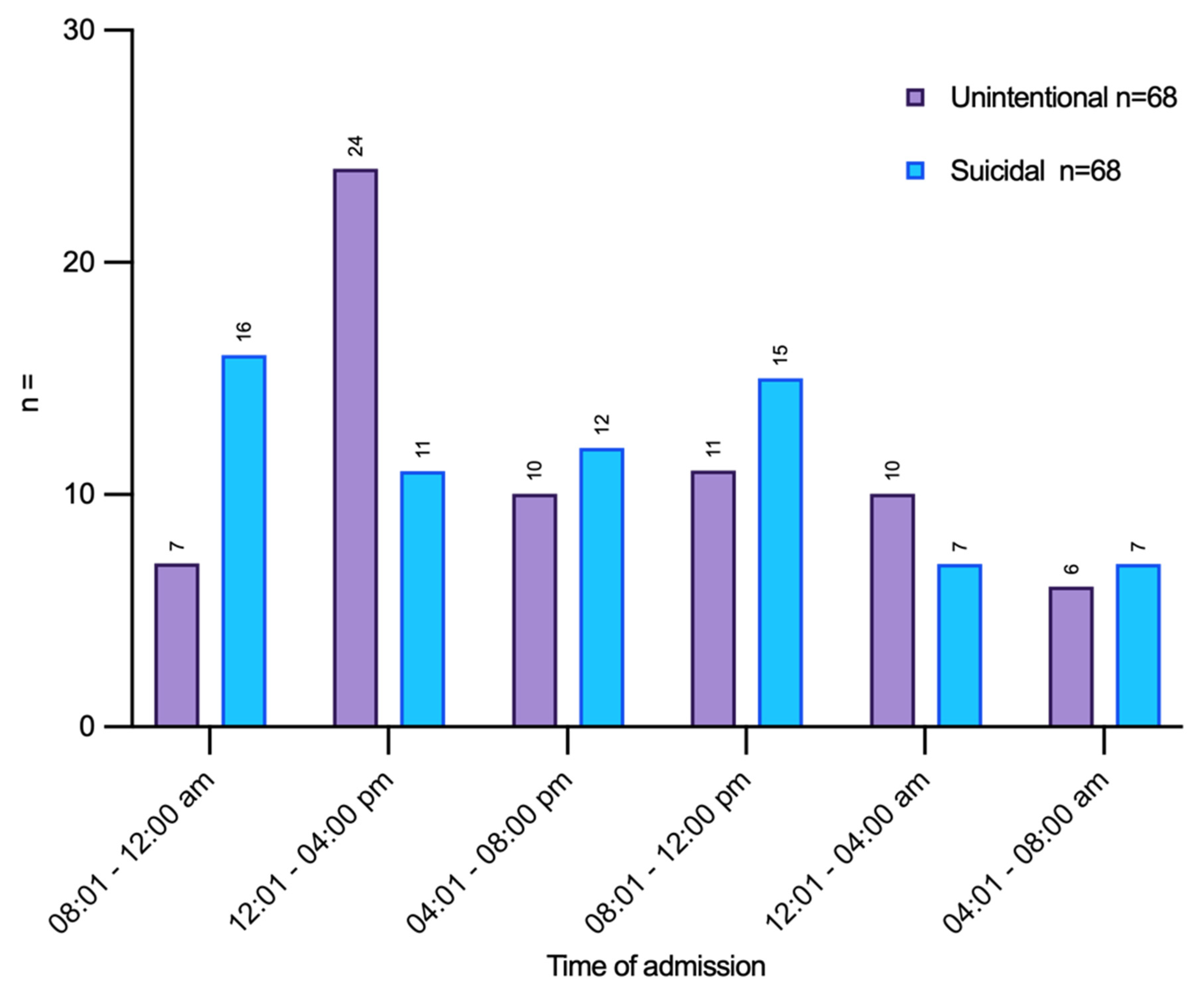

The arrival time of the patients is demonstrated in

Figure 1, with no differences for shift vs. normal working hours (p = 0.730) and admission on the weekend vs. weekday (p = 0.475) between the two groups.

Upon arrival at the emergency room, the suicidal group had a mean Glasgow coma scale (GCS) of 9.19 (± 5.43) and the unintentional group had a mean GCS of 11.87 (± 4.79) (p=0.001). The mean ISS for the suicidal group was 32.04 (± 23.43) and the mean ISS for the unintentional group was 17.37 (± 14.01). The suicidal group had a significantly higher ISS (p < 0.001). Additionally, the suicidal group had significantly more trauma to the lower extremities (p < 0.001), the pelvis (p < 0.001) and to the thorax (p = 0.013). The exact injury pattern is shown in

Table 2. A comprehensive analysis of the available data set revealed that the suicidal group exhibited a significantly elevated risk for various types of injuries, as indicated by the following odds ratios (OR): 3.34 (95% CI: 1.68–6.98) for pelvic injuries, 2.62 (95% CI: 1.28–5.37) for thoracic injuries, and 3.60 (95% CI: 1.77–7.30) for injuries to the lower extremities, in comparison to the unintentional group.

The lethality of the traumas in the suicidal group was 25%, which was significantly higher than the lethality of the unintentional groups of 10.3% (p = 0.041). Fall height was more closely correlated with ISS in the suicide group than in the unintentional fall group (see

Table 3). The suicidal group exhibited a 2.91 times higher probability of intrahospital mortality compared to the unintentional group (confidence interval 1.12–7.55).

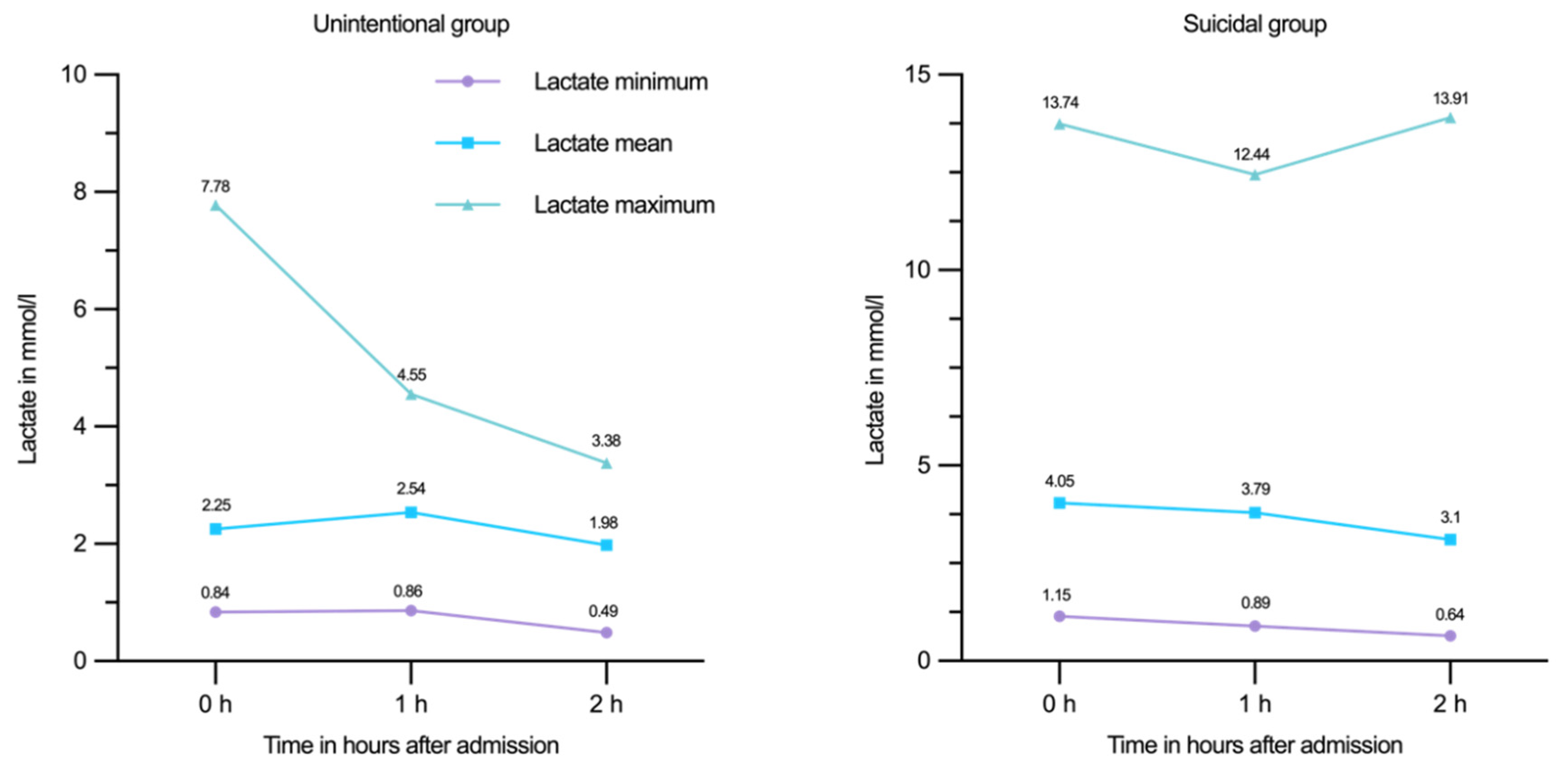

Table 4 shows the initial levels and evolution of arterial blood gas analysis with lactate, base excess, and pH levels during the first hours after trauma, with significant differences in lactate on arrival to the emergency room.

Figure 2A and

Figure 2B illustrate the evolution of blood gas analysis parameters for the suicide and accident groups.

Similarly, blood was routinely drawn on arrival at the emergency department, on arrival at the intensive care unit (ICU), and daily thereafter for analysis of white blood cell count, C-reactive protein (CRP), procalcitonin, and the patient's coagulation status after trauma. For the inflammatory markers,

Table 5 shows the results with the significant differences between the two groups.

The coagulation status with its significant differences is reported in

Table 6. The body temperature, which can affect the coagulation status of the patient, was also measured upon arrival at the ER and was, on average, 35.87 °C (± 1,05) in the unintentional group and 35,85 °C (± 1,36) in the suicidal group with no significant difference between the two.

The ICU additionally performs testing for vitamin D, total protein, and albumin to approximate the nutritional status of the patient. No significant differences between the two groups regarding vitamin D (p = 0.740), total protein (p = 0.423) and Albumin (p = 0.730) levels were detected.

Most of the treated patients received surgical treatment. The suicidal group received an average of 3.21 (± 4.27) operations per patient, which was significantly more (p = 0.016) than the unintentional group, which received on average of 1.69 (± 2.81) operations per patient. There were significant differences in the complication rate between the two groups, with the suicidal group having more wound healing disorders (p < 0.001) and more complications in general (p = 0.011). There were no significant differences in infections, acute respiratory distress syndrome, neurologic deficits, or surgical revision rates.

After immediate emergency treatment, a total of 72.1% of patients were transferred to the ICU, which was significantly higher (p = 0.008) than the 48.5% of patients in the unintentional group. The unintentional group was significantly more likely (p = 0.022) to be admitted to an intermediate care unit (38.2%) compared to 19.1% of the suicidal group. Total, cumulative ICU and IMC care was not significantly longer for the suicidal group with 15.69 days (± 21.1) in comparison to 8.63 days (± 20.39) for the unintentional group.

Discussion

Cohort Size and Demographic Data

Our findings align with existing literature comparing trauma outcomes in unintentional versus suicidal falls. Prior studies examining suicidal falls have included cohorts ranging from 40 to 149 patients who were alive upon hospital admission [

22,

29,

31]. Larger studies featuring a high number of suicidal fall cases have typically been conducted over extended periods or were based on post-mortem analyses. Demographic characteristics in the literature are consistent with our data, with most patients reported age between 40 and 45 years old. Furthermore, comparative studies have indicated a significantly higher proportion of males in the unintentional fall group. This trend is also reflected in the dataset. The reported mean fall height for suicidal cases ranges from 7,9 - 10.4 meters, placing our average fall height of 9.61 meters in the middle of the available literature [

22,

31].

Trauma Severity

This cohort had an average ISS of 32.04 (± 23.43) in the suicidal group and an average ISS of 17.37 (± 14.01) for the unintentional group. Significantly more trauma to the lower extremities, pelvis, and thorax were observed in the suicidal group. This highlights the severity of trauma associated with suicidal falls or jumps. Similarly, in the work of Kort et al. (2023), the suicidal group falls from greater height than the unintentional group (10.4 ± 7.3 m vs. 7.1 ± 5.7 m) and also report more injuries to the abdomen, pelvis, upper and lower extremities with pelvis injuries being 2.1 more likely to occur after a suicidal than an unintentional fall, which is slightly below the data of our cohort [

31]. In terms of severity of injury, the cohort in this study is among the most severely injured in the literature. Mortality was also significantly higher within the suicidal group with 25% compared to 10.3% in the unintentional group. A study from Piazzalunga et a. also report significantly higher mortality for the suicidal group (7.5 vs. 1.2%) [

22]. The higher values for mortality in our cohort can be explained by the lower ISS (18.88 ± 11.80) and lower fall height (7.85 ± 5.82) in the study of Piazzalunga and colleagues. Our data and the existing literature show that fall trauma in suicidal intent has a higher trauma severity associated with higher ISS, mortality and injury to lower extremity and pelvis, highlighting the severity of this kind of trauma. Our data and comparable results from other groups highlight that suicidal jumps / falls present with a higher injury severity score, higher mortality rates and more injuries to lower extremities and the pelvis, compared to unintentional falls.

Inflammatory Response

To analyze the inflammatory response of patients to the trauma following falls from height the blood gas analysis parameters and inflammatory parameters in the first 3 days after trauma were analyzed. This data is not yet present in the available literature. It is known that fall height correlates with ISS of patients and was also consistent in our dataset and demonstrated above [

32,

33]. In instances of suicidal falls, the accuracy of anamnesis concerning the height of the fall is often compromised, leaving it neither accurate nor complete. Therefore, the objective of this study was to determine whether there was a correlation between the inflammatory response of the patients and the severity of their trauma. A statistically significant difference in lactate levels was observed between the two groups. The suicidal group exhibited an average lactate level of 4.05 (± 2.69) mmol/L, while the unintentional group demonstrated an average of 2.25 (± 1.29) mmol/L. A strong correlation was observed between 0h, 1h and 2h lactate levels and ISS within the suicidal group. In the unintentional group, this correlation was only strong upon admission and was weaker at hour one and two after admission. This is consistent with the dataset of Cerović et al. (2003), who prospectively analyzed n=98 severely injured patients with a mortality of 25.5%. Here regression analysis, like in our case, was able to predict injury severity (ISS) based on lactate upon admission. Another study from Okello et al. (2014), which analyzed 108 severely injured patients, was able to demonstrate that admission lactate of > 2mmol/l was able to discriminate between severe and non-severe injuries with a sensitivity of 88% and a specificity of 38% [

34].

Regarding the PCT levels of patients following trauma, a positive correlation with the ISS was identified, and, on average, higher values were observed in the suicidal group. A variety of studies have been conducted on this topic, including those by Hoshino et al., Maier et al. and Wojtaszek et al., which have consistently shown a positive correlation between PCT and severe injury, with some even identifying its role as a prognostic marker for trauma-related complications. [

35,

36,

37]. A systematic review by AlRawahi et al. (2023) included 19 studies of severely injured patients and substantiated the role of procalcitonin (PCT) as a marker for severe trauma and as a prognostic marker of complications [

38].

Complications

In this study, a significantly higher prevalence of wound healing disorders, often requiring revision surgery was noted in the suicidal group compared to the unintentional group.

Impaired wound healing in patients who have attempted suicide by jumping may be influenced by a variety of psychological and local, monocentric, interdisciplinary factors. There is literature supporting an association between psychological distress and impaired wound healing, as evidenced by a comprehensive review and meta-analysis conducted by Walburn et al. (2009) [

39]. In addition, evidence suggests a correlation between depression and impaired wound healing, as observed in patients recovering from heart surgery in a study conducted by Doering et al. (2005) [

40]. In our local setting, interdisciplinary treatment involving both the psychiatric ward and the trauma center may have contributed to poorer outcomes, potentially due to challenges in coordination and management between the two departments. Furthermore, patient compliance following a suicide attempt may be lower in comparison to those who experienced unintentional trauma. This phenomenon serves to further complicate the healing process. As demonstrated in the study by Dew et al, mental health status has been shown to have a significant impact on postoperative physical morbidity and mortality in patients receiving heart surgery [

41].

Time of Injury

The initial hypothesis of the study proposed that suicidal injuries would be more common during hospital shift times and on weekends compared to unintentional falls. Given the established correlation between time of arrival at the hospital and subsequent risk of complications and mortality, the time of arrival was considered a potential confounder in our analysis [

42,

43]. Nevertheless, the findings of this study allowed the exclusion of this parameter as a confounding factor in the observed differences in outcomes between the two groups. This finding supports the hypothesis that other variables may play a more critical role in the group-specific complication and mortality rates.

Conclusion

Patients with suicidal jumps had more severe injury patterns with an ISS of 32.04 (± 23.43) compared to 17.37 (± 14.01) in the unintentional group (p<0.001). Notably, the cohort analyzed in this study presents one of the highest ISS values reported in the literature for this type of trauma, further highlighting the severity and complexity of injuries sustained in suicidal jumps. In comparison to trauma following unintentional falls from height, suicidal falls seem to be more complex to treat and to demand more resources. The suicidal patients had a higher complication rate (p=0.011), with impaired wound healing being the most common complication, an increased total transfusion requirement and a greater number of (re-)operations compared to the unintentional fall cohort. In these patients, special attention should be paid to the frequent occurrence of complications (e.g., impaired wound healing and infection), increased transfusion requirements, and significantly impaired coagulation status on hospital admission. Confounding factors such as hypothermia and time of admission could not be identified in this study but should always be considered when treating high-energy trauma such as suicidal fall patients.

Credit Author Statement

AAZ: Conceptualization, Investigation, Data Curation, Writing - Original Draft, Writing - Review & Editing, Visualization, Project administration, Funding acquisition MRS: Investigation, Data Curation JR: Resources, Writing - Review & Editing CP: Resources, Writing - Review & Editing HP: Writing - Review & Editing, Supervision DC: Writing - Review & Editing, Supervision SS: Conceptualization, Writing – Original Draft, Writing - Review & Editing, Supervision, Graphics, Project administration.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Open Access Publication Fund of the University of Bonn.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Hossain, M.M., et al. >Epidemiology of mental health problems in COVID-19: a review. F1000Res 2020, 9, 636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torales, J., et al. The outbreak of COVID-19 coronavirus and its impact on global mental health. Int J Soc Psychiatry 2020, 66, 317–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, E.A.K., A.K. Mitra, and A.R. Bhuiyan. Impact of COVID-19 on Mental Health in Adolescents: A Systematic Review. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2021, 18. [Google Scholar]

- Bundesamt, S. , Registred deaths from suicide. 2023.

- Hepp, U., et al. Methods of suicide used by children and adolescents. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry 2012, 21, 67–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Organization, W.H. , Preventing suicide: A global imperative. 2014: World Health Organization.

- Värnik, A., et al. Gender issues in suicide rates, trends and methods among youths aged 15–24 in 15 European countries. Journal of affective disorders 2009, 113, 216–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gore-Jones, V. and J. O'Callaghan. Suicide attempts by jumping from a height: a consultation liaison experience. Australas Psychiatry 2012, 20, 309–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rocos, B., M. Acharya, and T.J. Chesser, The Pattern of Injury and Workload Associated with Managing Patients After Suicide Attempt by Jumping from a Height. Open Orthop J, 2015. 9: p. 395-8.

- Teh, J., et al., Jumpers and fallers: a comparison of the distribution of skeletal injury. Clin Radiol, 2003. 58(6): p. 482-6.

- Katz, K., et al., Injuries in attempted suicide by jumping from a height. Injury, 1988. 19(6): p. 371-4.

- Richter, D., et al. Vertical deceleration injuries: a comparative study of the injury patterns of 101 patients after accidental and intentional high falls. Injury 1996, 27, 655–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- J Zeman, T.P., J Matějka, Suicidal jumper's fracture. Acta Chirurgiae orthopaedicae et Traumatologiae čechoslovaca, 2010. 77(6): p. 501-6.

- Roy-Camille, R., et al., Transverse fracture of the upper sacrum. Suicidal jumper's fracture. Spine (Phila Pa 1976), 1985. 10(9): p. 838-45.

- Sanders, R. Displaced intra-articular fractures of the calcaneus. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2000, 82, 225–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sanders, R., et al., Operative treatment in 120 displaced intraarticular calcaneal fractures. Results using a prognostic computed tomography scan classification. Clin Orthop Relat Res, 1993(290): p. 87-95.

- Sanders, R., et al., Operative treatment of displaced intraarticular calcaneal fractures: long-term (10-20 Years) results in 108 fractures using a prognostic CT classification. J Orthop Trauma, 2014. 28(10): p. 551-63.

- Daftary, A., A.H. Haims, and M.R. Baumgaertner, Fractures of the calcaneus: a review with emphasis on CT. Radiographics, 2005. 25(5): p. 1215-26.

- Mitchell, M.J., J.C. McKinley, and C.M. Robinson. The epidemiology of calcaneal fractures. Foot (Edinb) 2009, 19, 197–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McBride, D.J., C. Ramamurthy, and P. Laing. (ii) The hindfoot: Calcaneal and talar fractures and dislocations—Part I: Fractures of the calcaneum. Current Orthopaedics 2005, 19, 94–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GÜLtaÇ, E., et al., Evaluation of the association between bilateral calcaneal fractures and suicide attempts: Findings from 4 different trauma centers in Turkey. Journal of Experimental and Clinical Medicine, 2021. 38(3): p. 221-226.

- Piazzalunga, D., et al., Suicidal fall from heights trauma: difficult management and poor results. Eur J Trauma Emerg Surg, 2020. 46(2): p. 383-388.

- Baker, S.P., et al., The injury severity score: a method for describing patients with multiple injuries and evaluating emergency care. J Trauma, 1974. 14(3): p. 187-96.

- Jacobs, C., et al. [Influence of trauma mechanisms on thoracic and lumbar spinal fractures]. Unfallchirurg 2018, 121, 739–746. [Google Scholar]

- Scheidt, S., et al., [Influence of the trauma mechanism on cervical spine injuries]. Unfallchirurg, 2019. 122(12): p. 958-966.

- van Veelen, M.J. and M. Brodmann Maeder, Hypothermia in Trauma. Int J Environ Res Public Health, 2021. 18(16).

- de Heer, G., et al., Advance Directives and Powers of Attorney in Intensive Care Patients. Dtsch Arztebl Int, 2017. 114(21): p. 363-370.

- Bundesamt, S., Ausstattung privarer Haushalte mit Informations- und Kommunikationstechnik - Deutschland. 2018.

- Giordano, V., et al., Patterns and management of musculoskeletal injuries in attempted suicide by jumping from a height: a single, regional level I trauma center experience. Eur J Trauma Emerg Surg, 2022. 48(2): p. 915-920.

- e.V., D.G.f.U., S3-Leitlinie Polytrauma/Schwerverletzten-Behandlung (AWMF Registernummer 187-023), Version 4.0 (31.12.2022). 2022.

- Kort, I., et al., A comparative study of the injury pattern between suicidal and accidental falls from height in Northern Tunisia. J Forensic Leg Med, 2023. 97: p. 102531.

- Papadakis, S.A., et al., Falls from height due to accident and suicide attempt in Greece. A comparison of the injury patterns. Injury, 2020. 51(2): p. 230-234.

- Petaros, A., et al., Retrospective analysis of free-fall fractures with regard to height and cause of fall. Forensic Sci Int, 2013. 226(1-3): p. 290-5.

- Okello, M., et al., Serum lactate as a predictor of early outcomes among trauma patients in Uganda. Int J Emerg Med, 2014. 7: p. 20.

- Wojtaszek, M., et al., Changes of procalcitonin level in multiple trauma patients. Anaesthesiol Intensive Ther, 2014. 46(2): p. 78-82.

- Maier, M., et al., Serum procalcitonin levels in patients with multiple injuries including visceral trauma. J Trauma, 2009. 66(1): p. 243-9.

- Hoshino, K., et al. Incidence of elevated procalcitonin and presepsin levels after severe trauma: a pilot cohort study. Anaesth Intensive Care 2017, 45, 600–604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AlRawahi, A.N., et al., The prognostic value of serum procalcitonin measurements in critically injured patients: a systematic review. Crit Care, 2019. 23(1): p. 390.

- Walburn, J., et al., Psychological stress and wound healing in humans: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Psychosom Res, 2009. 67(3): p. 253-71.

- Doering, L.V., et al., Depression, healing, and recovery from coronary artery bypass surgery. Am J Crit Care, 2005. 14(4): p. 316-24.

- Dew, M.A., et al., Early post-transplant medical compliance and mental health predict physical morbidity and mortality one to three years after heart transplantation. J Heart Lung Transplant, 1999. 18(6): p. 549-62.

- Bell, C.M. and D.A. Redelmeier, Mortality among patients admitted to hospitals on weekends as compared with weekdays. N Engl J Med, 2001. 345(9): p. 663-8.

- Egol, K.A., et al., Mortality rates following trauma: The difference is night and day. J Emerg Trauma Shock, 2011. 4(2): p. 178-83.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).