Submitted:

31 March 2025

Posted:

01 April 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

Introduction

Methods

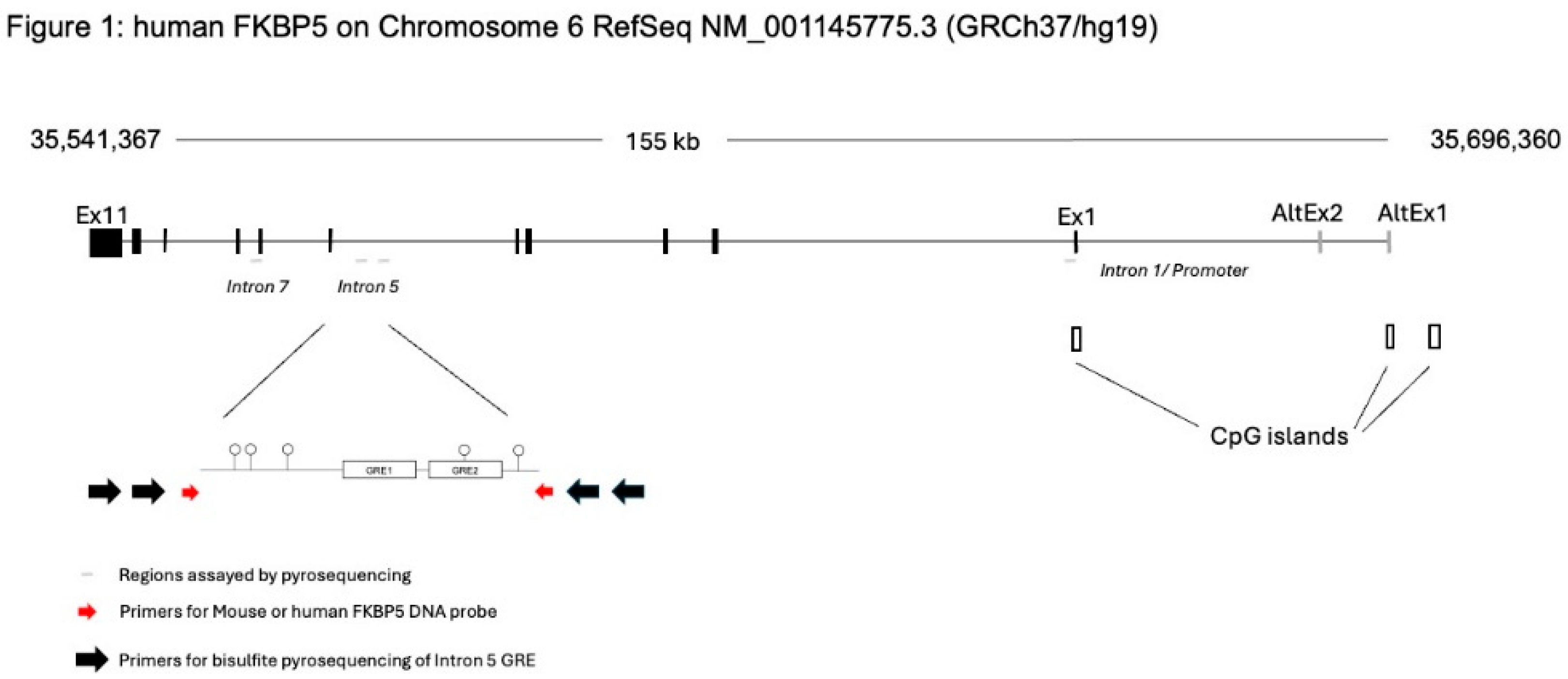

Probe Design and Amplification

In Vitro Methylation of DNA Probes

Cell Culture and Transfection

DNA Extraction and Methylation Analysis by Bisulfite Pyrosequencing

Gene Expression Analysis

Results

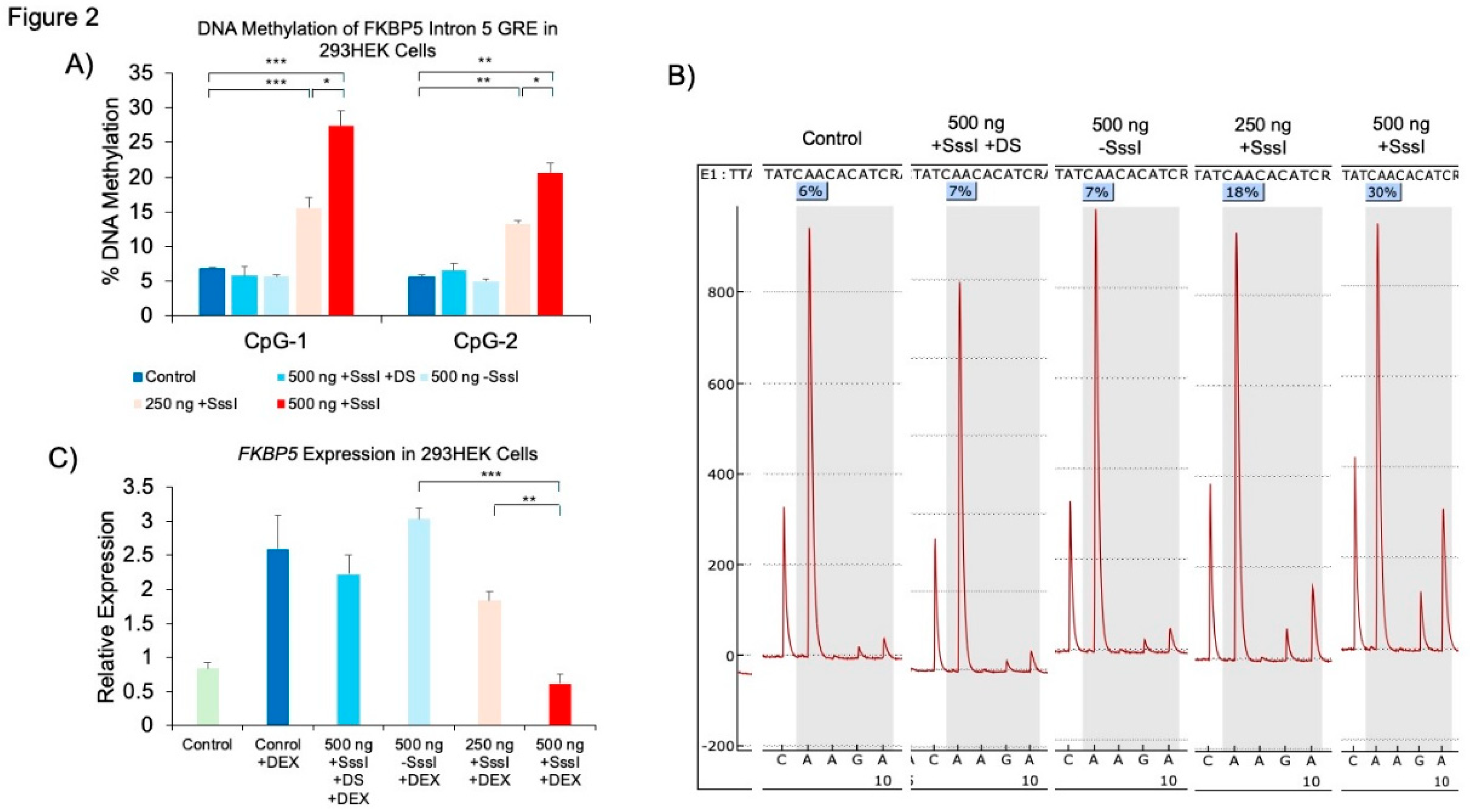

The Use of Methylated, Single-Stranded Probe to Induce Target-Specific DNAm

The Effect of Probe-Induced DNAm on Gene Expression

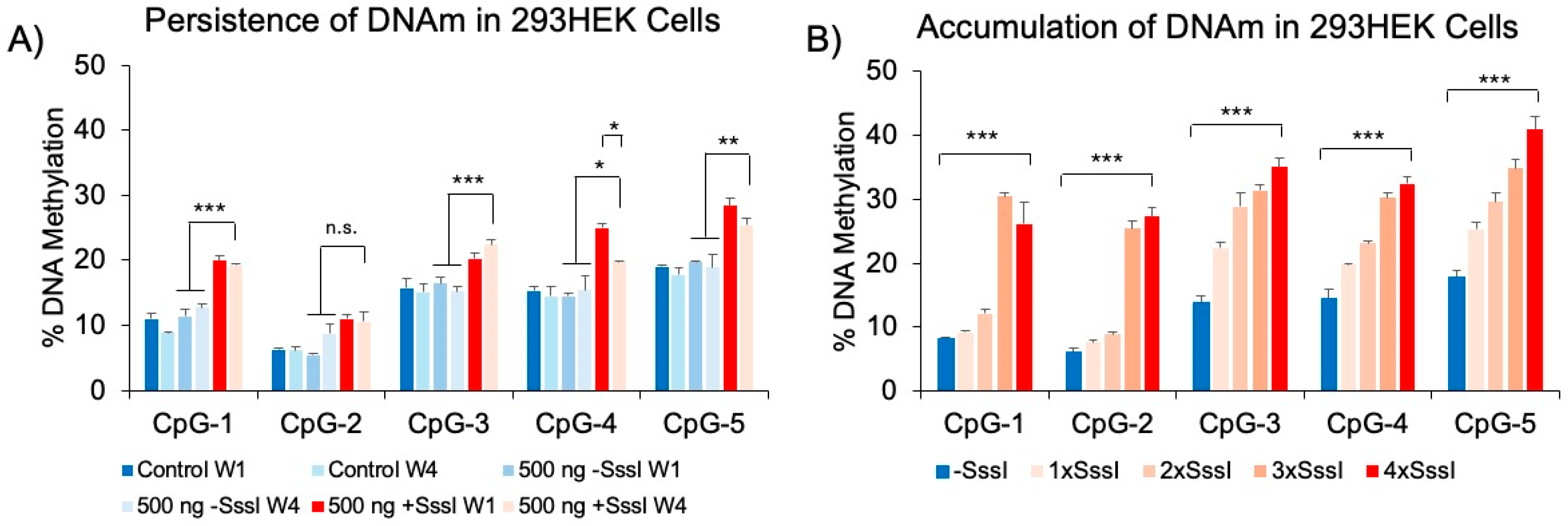

Persistence of Probe-Induced DNAm Patterns and Accumulation of DNAm Following Multiple Probe Transfections

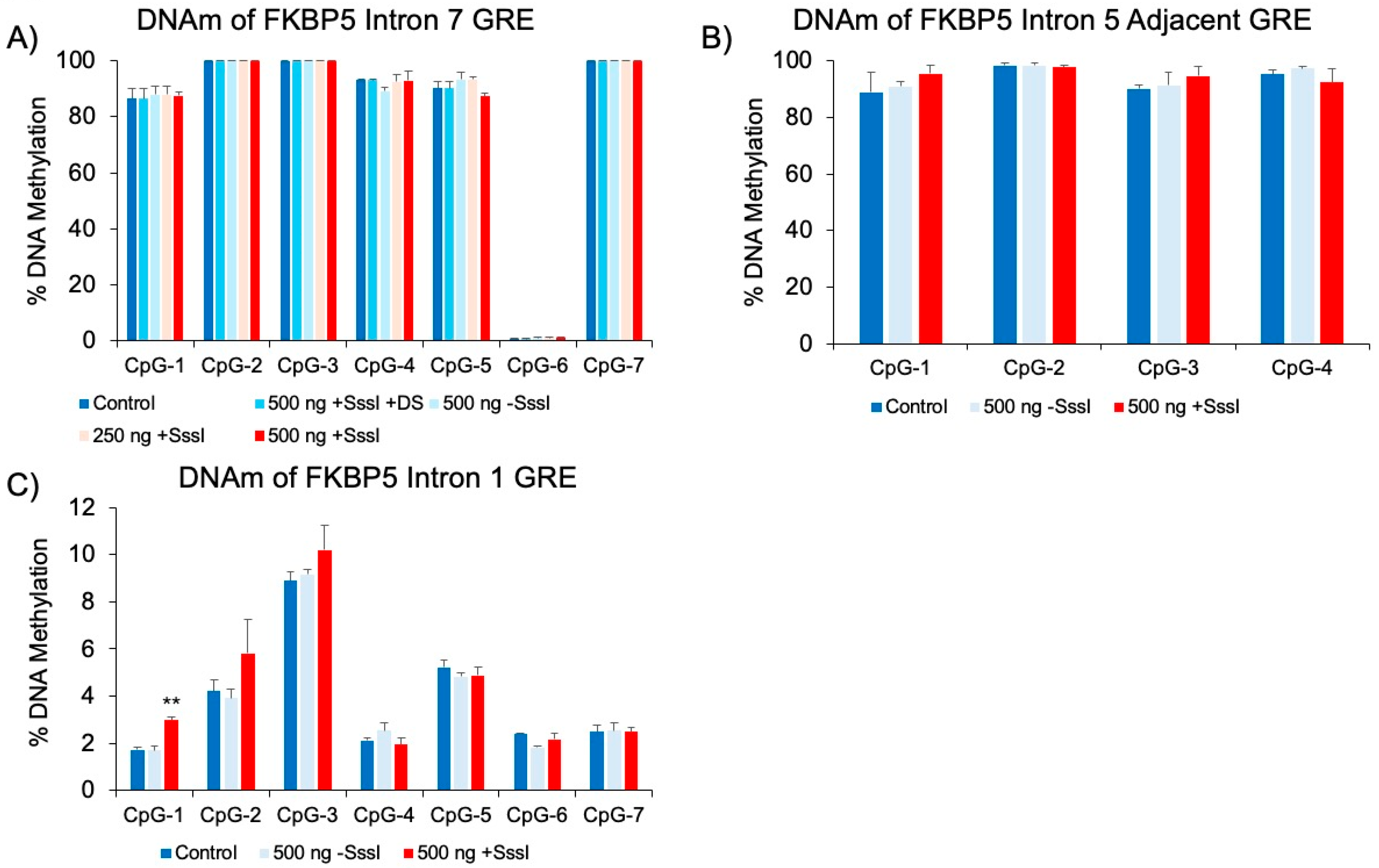

Effect of DNA Probes in Non-Targeted Regions

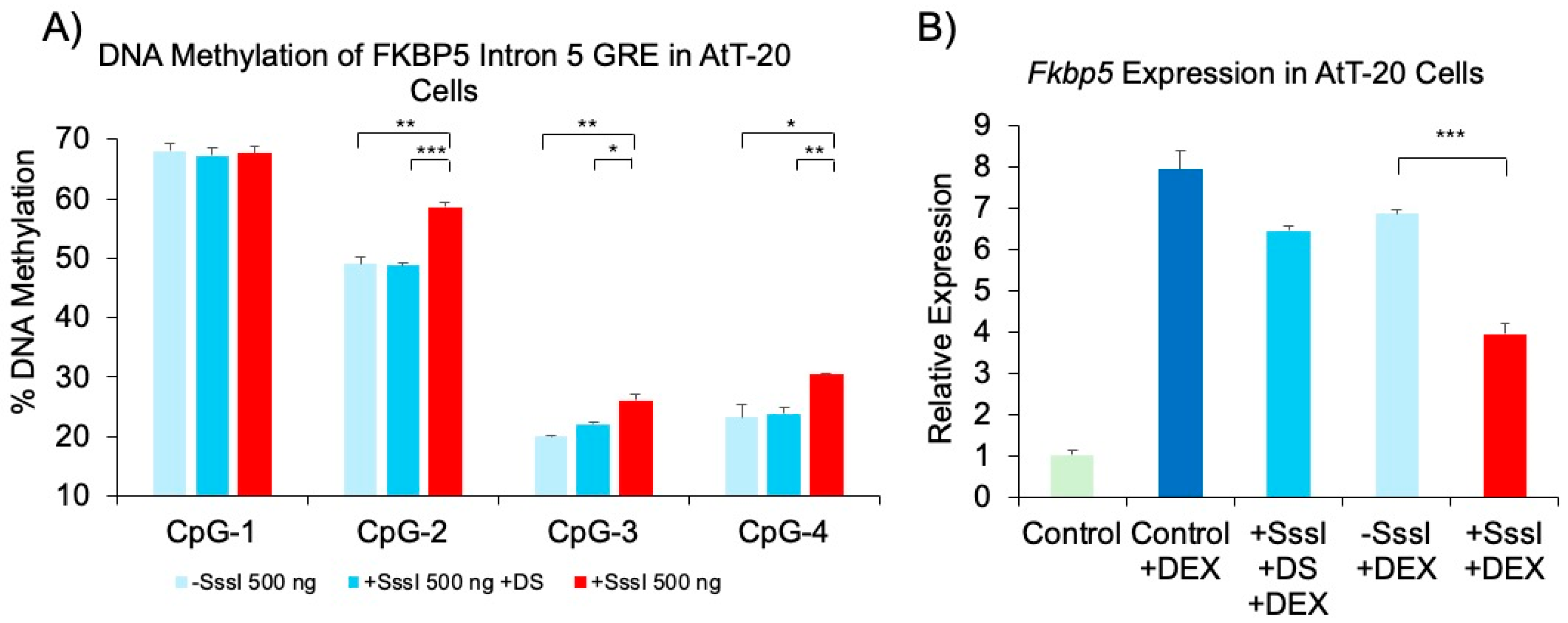

Epigenetic and Transcriptional Effects of Methylated, Single-Stranded Probe in a Mouse Pituitary Cell Line

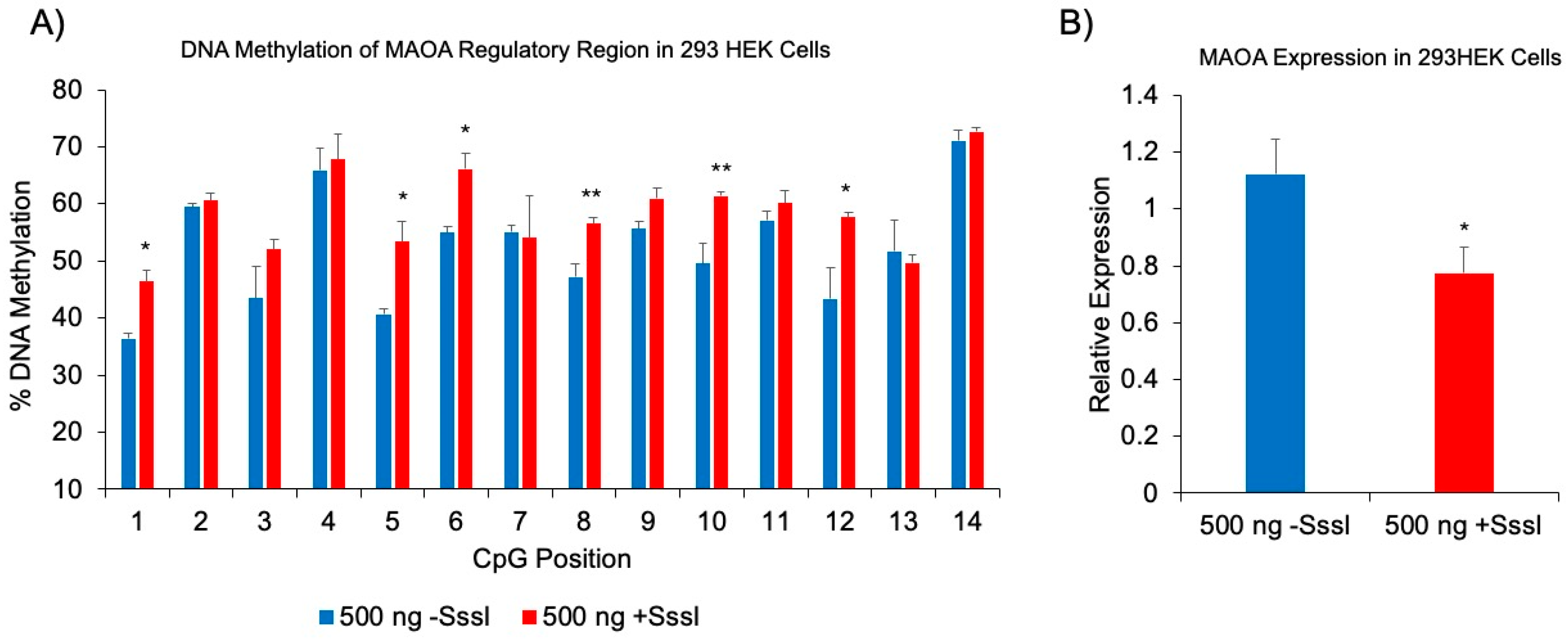

Additional Genomic Target of DNAm Probe: MAOA.

Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

References

- Jones PL, Veenstra GJ, Wade PA, Vermaak D, Kass SU, Landsberger N, Strouboulis J, Wolffe AP. Methylated DNA and MeCP2 recruit histone deacetylase to repress transcription. Nat Genet 1998; 19:187-91.

- Baylin SB. Tying it all together: epigenetics, genetics, cell cycle, and cancer. Science 1997; 277:1948-9. [CrossRef]

- Jones PA, Baylin SB. The fundamental role of epigenetic events in cancer. Nat Rev Genet 2002; 3:415-28.

- Landgrave-Gomez J, Mercado-Gomez O, Guevara-Guzman R. Epigenetic mechanisms in neurological and neurodegenerative diseases. Front Cell Neurosci 2015; 9:58. PMC4343006.

- Klengel T, Mehta D, Anacker C, Rex-Haffner M, Pruessner JC, Pariante CM, Pace TW, Mercer KB, Mayberg HS, Bradley B, et al. Allele-specific FKBP5 DNA demethylation mediates gene-childhood trauma interactions. Nat Neurosci 2013; 16:33-41. PMC4136922.

- Uddin M, Aiello AE, Wildman DE, Koenen KC, Pawelec G, de Los Santos R, Goldmann E, Galea S. Epigenetic and immune function profiles associated with posttraumatic stress disorder. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2010; 107:9470-5. PMC2889041.

- Murphy TM, O'Donovan A, Mullins N, O'Farrelly C, McCann A, Malone K. Anxiety is associated with higher levels of global DNA methylation and altered expression of epigenetic and interleukin-6 genes. Psychiatr Genet 2015; 25:71-8. [CrossRef]

- Tsankova NM, Berton O, Renthal W, Kumar A, Neve RL, Nestler EJ. Sustained hippocampal chromatin regulation in a mouse model of depression and antidepressant action. Nat Neurosci 2006; 9:519-25. [CrossRef]

- Weaver IC, Cervoni N, Champagne FA, D'Alessio AC, Sharma S, Seckl JR, Dymov S, Szyf M, Meaney MJ. Epigenetic programming by maternal behavior. Nat Neurosci 2004; 7:847-54.

- Erdmann RM, Picard CL. RNA-directed DNA Methylation. PLoS Genet 2020; 16:e1009034. PMC7544125.

- Yang X, Lay F, Han H, Jones PA. Targeting DNA methylation for epigenetic therapy. Trends Pharmacol Sci 2010; 31:536-46. PMC2967479. [CrossRef]

- Liu XS, Wu H, Ji X, Stelzer Y, Wu X, Czauderna S, Shu J, Dadon D, Young RA, Jaenisch R. Editing DNA Methylation in the Mammalian Genome. Cell 2016; 167:233-47 e17. PMC5062609.

- Vojta A, Dobrinic P, Tadic V, Bockor L, Korac P, Julg B, Klasic M, Zoldos V. Repurposing the CRISPR-Cas9 system for targeted DNA methylation. Nucleic Acids Res 2016; 44:5615-28. PMC4937303.

- Xu X, Tao Y, Gao X, Zhang L, Li X, Zou W, Ruan K, Wang F, Xu GL, Hu R. A CRISPR-based approach for targeted DNA demethylation. Cell Discov 2016; 2:16009. PMC4853773.

- Kim S, Koo T, Jee HG, Cho HY, Lee G, Lim DG, Shin HS, Kim JS. CRISPR RNAs trigger innate immune responses in human cells. Genome Res 2018; 28:367-73. PMC5848615.

- Ewaisha R, Anderson KS. Immunogenicity of CRISPR therapeutics-Critical considerations for clinical translation. Front Bioeng Biotechnol 2023; 11:1138596. PMC9978118.

- Hakim CH, Kumar SRP, Perez-Lopez DO, Wasala NB, Zhang D, Yue Y, Teixeira J, Pan X, Zhang K, Million ED, et al. Cas9-specific immune responses compromise local and systemic AAV CRISPR therapy in multiple dystrophic canine models. Nat Commun 2021; 12:6769. PMC8613397.

- Zhang XH, Tee LY, Wang XG, Huang QS, Yang SH. Off-target Effects in CRISPR/Cas9-mediated Genome Engineering. Mol Ther Nucleic Acids 2015; 4:e264. PMC4877446.

- Hoijer I, Emmanouilidou A, Ostlund R, van Schendel R, Bozorgpana S, Tijsterman M, Feuk L, Gyllensten U, den Hoed M, Ameur A. CRISPR-Cas9 induces large structural variants at on-target and off-target sites in vivo that segregate across generations. Nat Commun 2022; 13:627. PMC8810904.

- Frangoul H, Altshuler D, Cappellini MD, Chen YS, Domm J, Eustace BK, Foell J, de la Fuente J, Grupp S, Handgretinger R, et al. CRISPR-Cas9 Gene Editing for Sickle Cell Disease and beta-Thalassemia. N Engl J Med 2021; 384:252-60.

- Stadtmauer EA, Fraietta JA, Davis MM, Cohen AD, Weber KL, Lancaster E, Mangan PA, Kulikovskaya I, Gupta M, Chen F, et al. CRISPR-engineered T cells in patients with refractory cancer. Science 2020; 367. PMC11249135.

- Scammell JG, Denny WB, Valentine DL, Smith DF. Overexpression of the FK506-binding immunophilin FKBP51 is the common cause of glucocorticoid resistance in three New World primates. Gen Comp Endocrinol 2001; 124:152-65.

- Nelson JC, Davis JM. DST studies in psychotic depression: a meta-analysis. Am J Psychiatry 1997; 154:1497-503.

- Binder EB, Salyakina D, Lichtner P, Wochnik GM, Ising M, Putz B, Papiol S, Seaman S, Lucae S, Kohli MA, et al. Polymorphisms in FKBP5 are associated with increased recurrence of depressive episodes and rapid response to antidepressant treatment. Nat Genet 2004; 36:1319-25.

- Tozzi L, Farrell C, Booij L, Doolin K, Nemoda Z, Szyf M, Pomares FB, Chiarella J, O'Keane V, Frodl T. Epigenetic Changes of FKBP5 as a Link Connecting Genetic and Environmental Risk Factors with Structural and Functional Brain Changes in Major Depression. Neuropsychopharmacology 2018; 43:1138-45. PMC5854813.

- Lee RS, Tamashiro KL, Yang X, Purcell RH, Harvey A, Willour VL, Huo Y, Rongione M, Wand GS, Potash JB. Chronic corticosterone exposure increases expression and decreases deoxyribonucleic acid methylation of Fkbp5 in mice. Endocrinology 2010; 151:4332-43. PMC2940504. [CrossRef]

- Cox OH, Song HY, Garrison-Desany HM, Gadiwalla N, Carey JL, Menzies J, Lee RS. Characterization of glucocorticoid-induced loss of DNA methylation of the stress-response gene Fkbp5 in neuronal cells. Epigenetics 2021; 16:1377-97. PMC8813076.

- Wochnik GM, Ruegg J, Abel GA, Schmidt U, Holsboer F, Rein T. FK506-binding proteins 51 and 52 differentially regulate dynein interaction and nuclear translocation of the glucocorticoid receptor in mammalian cells. J Biol Chem 2005; 280:4609-16.

- Hawn SE, Sheerin CM, Lind MJ, Hicks TA, Marraccini ME, Bountress K, Bacanu SA, Nugent NR, Amstadter AB. GxE effects of FKBP5 and traumatic life events on PTSD: A meta-analysis. J Affect Disord 2019; 243:455-62. PMC6487483. [CrossRef]

- Qiu B, Luczak SE, Wall TL, Kirchhoff AM, Xu Y, Eng MY, Stewart RB, Shou W, Boehm SL, Chester JA, et al. The FKBP5 Gene Affects Alcohol Drinking in Knockout Mice and Is Implicated in Alcohol Drinking in Humans. Int J Mol Sci 2016; 17. PMC5000669.

- Shumay E, Logan J, Volkow ND, Fowler JS. Evidence that the methylation state of the monoamine oxidase A (MAOA) gene predicts brain activity of MAO A enzyme in healthy men. Epigenetics 2012; 7:1151-60. PMC3469457.

- Renbaum P, Abrahamove D, Fainsod A, Wilson GG, Rottem S, Razin A. Cloning, characterization, and expression in Escherichia coli of the gene coding for the CpG DNA methylase from Spiroplasma sp. strain MQ1(M.SssI). Nucleic Acids Res 1990; 18:1145-52. PMC330428.

- Duis J, Cox OH, Ji Y, Seifuddin F, Lee RS, Wang X. Effect of Genotype and Maternal Affective Disorder on Intronic Methylation of FK506 Binding Protein 5 in Cord Blood DNA. Front Genet 2018; 9:648. PMC6305129.

- Cox OH, Song HY, Garrison-Desany HM, Gadiwalla N, Carey JL, Menzies J, Lee RS. Characterization of glucocorticoid-induced loss of DNA methylation of the stress-response gene Fkbp5 in neuronal cells. Epigenetics 2021:1-21. [CrossRef]

- Seifuddin F, Wand G, Cox O, Pirooznia M, Moody L, Yang X, Tai J, Boersma G, Tamashiro K, Zandi P, et al. Genome-wide Methyl-Seq analysis of blood-brain targets of glucocorticoid exposure. Epigenetics 2017; 12:637-52. PMC5687336. [CrossRef]

- Cox OH, Seifuddin F, Guo J, Pirooznia M, Boersma GJ, Wang J, Tamashiro KLK, Lee RS. Implementation of the Methyl-Seq platform to identify tissue- and sex-specific DNA methylation differences in the rat epigenome. Epigenetics 2024; 19:2393945. PMC11418217. [CrossRef]

- Murphy DE, de Jong OG, Brouwer M, Wood MJ, Lavieu G, Schiffelers RM, Vader P. Extracellular vesicle-based therapeutics: natural versus engineered targeting and trafficking. Exp Mol Med 2019; 51:1-12. PMC6418170.

| Probe Primers | Sequence | Size |

| Human FKBP5 Probe – Forward | 5’- AAAGTCAAACCAAACCAAATTACC -3’ | 256 bp |

| Human FKBP5 Probe – Reverse | 5’- TTTGTTACTGCTGTGCACTCTCT -3’ | |

| Human MAOA Probe – Forward | 5’- TCGACGTAGTCGTGATCGG -3’ | 170 bp |

| Human MAOA Probe – Reverse | 5’- GCAGGATATGGGGCCAAG -3’ | |

| Mouse Fkbp5 Probe – Forward | 5’- CAGACACCAGCTACTATAATTAG -3’ | 239 bp |

| Mouse Fkbp5 Probe – Reverse | 5’- GCACATGAACTCGATGTGCTGACA -3’ | |

| Pyrosequencing Primers | Sequence | Size |

| Human FKBP5 Intron 5 Outside – A | GGTAGAGAAAGAAATAAATAAGTTA |

286 bp |

| Human FKBP5 Intron 5 Outside – B | TTCTTACATTTCATTTTTATTACTACTA | |

| Human FKBP5 Intron 5 Inside – A* | AAGATTATGTAATTTAAAGGGGGAGGG | |

| Human FKBP5 Intron 5 Inside – B | CTCTCTTTCCTTTTTTCCCCCCTAT | |

| Human FKBP5 Intron 5 Pyro 1 | TCTTTCCTTTTTTCCCCCCTATT | |

| Human FKBP5 Intron 5 Pyro 2 | CAATTTAAATAATATTTTACAACT | |

| Human FKBP5 Intron 5_2 Out – A | ATTTAATTGGTTTGGGTGTTAGAA |

406 bp |

| Human FKBP5 Intron 5_2 Out – B | CCTCTCAATACTTTCAACCACA | |

| Human FKBP5 Intron 5_2 In – A* | GAGAATTATTGTATTGGAGGTT | |

| Human FKBP5 Intron 5_2 In – B | ATTCTACAAATTCCAATTATTAAC | |

| Human FKBP5 Intron 5_2 Pyro 1 | GTATTGGAGGTTTATTGGTT | |

| Human FKBP5 Intron 5_2 Pyro 2 | TAGATGATTATGAGTTTGGAGTT | |

| Human FKBP5 Intron 5_2 Pyro 3 | GTTTAAGTTTTTTTTATATTTGTT | |

| Human FKBP5 Intron 5_2 Pyro 4 | GATTTGGAGAGGGAAAGGAGGT | |

| Human FKBP5 Intron 1 Out – A | AGTTTAAATTGTTTTATGTAGAATTTATTGA |

350 bp |

| Human FKBP5 Intron 1 Out – B | TCACTCCCAAACCATACC | |

| Human FKBP5 Intron 1 Inside – A | GTTTTGAATTATATTGAAGGGTATTT | |

| Human FKBP5 Intron 1 Inside – B* | CAAAACTCCTTATACTCTTCTATTCTAA | |

| Human FKBP5 Intron 1 Pyro 1 | GTAGAATTYGATTTTAGAGA | |

| Human FKBP5 Intron 7 Outside – A | AGAGTGAAATTGAGATGGAAATATGT |

503 bp |

| Human FKBP5 Intron 7 Outside – B | AATTTCTTCTCCATCCACTTCCTATA | |

| Human FKBP5 Intron 7 Inside – A | AGGAGGTATGTTGTTTTTGGAATTTAAG | |

| Human FKBP5 Intron 7 Inside – B* | AATTTATCTCTTACCTCCAACACT | |

| Human FKBP5 Intron 7 Pyro 1 | GGAGAAGTATAAAAAAAAAATGG | |

| Human FKBP5 Intron 7 Pyro 2 | GTTATAGAGTTTAGTGGTTT | |

| Human FKBP5 Intron 7 Pyro 3 | GGAGTTATAGTGTAGGTTTT | |

| Human FKBP5 Intron 7 Pyro 4 | TTAAGGAGTTATTTGGTAGA | |

| Human FKBP5 Intron 7 Pyro 5 | TGATATATAGGAATAAAATAAGAAT | |

| Human MAOA Outside – A | GATTTAGGAGYGTGTTAGTTAAAGT |

278 bp |

| Human MAOA Outside – B | TTATTATATCTACCTCCCCCAATC | |

| Human MAOA Inside – A | AGTTAAAGTATGGAGAATTAAG | |

| Human MAOA Inside – B* | ATCTACCTCCCCCAATCACACCACCAAC | |

| Human MAOA Pyro 1 | AAAGTATGGAGAATTAAGAGAAGG | |

| Human MAOA Pyro 2 | GAGTATYGYGGGTTATATG | |

| Human MAOA Pyro 3 | AGGTGGTATTTTAGGTTAGTGTGGA | |

| Mouse Fkbp5 Intron 5 Outside – A | GATGATTAGTTTTTTTTAGTAGTGATGT |

308 bp |

| Mouse Fkbp5 Intron 5 Outside – B | CTTATTATTCTCTTACTACCCTAA | |

| Mouse Fkbp5 Intron 5 Inside – A | TAGTTTTTGGGGAAGAGTGTAGAGTTAT | |

| Mouse Fkbp5 Intron 5 Inside – B* | ATTTTAAAAAACACAAAACACCCTATT | |

| Mouse Fkbp5 Intron 5 Pyro 1 | AGAAAAGGGAAAGTAGG | |

| Mouse Fkbp5 Intron 5 Pyro 2 | TAGTTTTTGTTATTGTTGTATG |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).