1. Introduction

At the end of 2023, Mali reported 33,162 confirmed cases of COVID-19 and 743 deaths to the World Health Organization, falling roughly into the regional average (World Health Organization, 2023). Unfortunately, since accurate counts of cases depends on regular testing, it is unlikely that those figures are accurate as Mali has reportedly struggled with testing since the start of the pandemic (Ly et al., 2022). Serological surveys conducted in Bamako during the first wave of the epidemic also demonstrated that SARS-CoV-2 exposure was more widespread than had been reported (Cissoko et al., 2020; Maiga et al., 2022).

The first doses of COVID-19 vaccines arrived in Mali in March 2021 under the civilian government installed by the first coup d’état (although that government would be replaced by a military dictatorship two months later). As of November 2023, only 22% of the population had received a single dose of a COVID-19 vaccine with only 18% completing a primary series. 1 According to the WHO, Mali has the 13th worst COVID-19 vaccination rate in the world (World Health Organization, 2023)

The US-based GAIA Vaccine Foundation (GAIA VF) has a long history of HIV, TB and HPV vaccine-focused research in Mali (Crippin et al., 2022; Crippin et al., 2024; De Groot et al., 2017; Téguété et al. 2017). Given the opportunity to evaluate the challenges involved in introducing a new vaccine for a new virus (SARS-CoV-2) in September 2021, GAIA VF launched a survey-based vaccine confidence research project in two areas of Mali. Twelve community health clinics and their coordinating institution, the Center of Reference in Commune I of Bamako, participated along with one rural2 community clinic in the village of Keniero. The goal of the project was to characterize the impact of the introduction of a new vaccine amid a pandemic and (ongoing) political instability on community and healthcare provider (HCP) knowledge, attitudes, and vaccine confidence. The survey project was coupled with a two-pronged vaccine promotion intervention that included HCP trainings and a public education campaign building upon GAIA VF’s previous work around promoting vaccine uptake.

Previously, we evaluated attitudes and interest in HPV vaccination, and learned that vaccine acceptedness was high, in Bamako (Crippin et al., 2024). GAVI began supplying HPV vaccine to Mai in the fall of 2024, and the vaccine is currently being given to 10 year old girls as part of the routine childhood vaccine program. In this manuscript, we present lessons learned from COVID vaccine outreach that will inform the approach to HPV and the results of surveys of both community members and HCPs. The study’s results fill an important knowledge gap related to vaccine usage in Mali as well as the impact of political instability and a change from democratic to nondemocratic governance on the public health response to vaccination. Methods developed to address barriers to COVID-19 uptake will provide important insights into effective vaccine interventions in Mali, and other countries, faced with similar challenges to vaccine confidence.

2. Materials and Methods

Building upon firsthand experience from a pilot HPV vaccination program, GAIA VF developed the components of both a community and HCP vaccine promotion intervention in collaboration with Malian physicians, stakeholders and community leaders to support COVID vaccine rollout between February and June 2021. GAIA VF staff engaged with Malian public health officials to address vaccination plans in Bamako. The team identified 12 community clinics (the first level of health structures in Mali) with qualified staff in Bamako and 1 community clinic in rural Keniero for participation in the project (Supplemental Figure S1 - Map). With support from Malian public health authorities, we developed materials (cloth, posters, surveys, radio advertisements) for the vaccine confidence program.

2.1. Public Education Intervention on Vaccines

Community healthcare workers (CHWs) led the public education intervention about the vaccine, in each of the 13 participating communities. The CHWs recruited for this project are primarily women who belong to associations that regularly perform community outreach for their local clinic. Each participating CHW was trained in classroom-style sessions under the direction of members of the Regional Health Directorate and the National Center for Immunization. Twice per week, the CHWs setup events in an open area in their community to educate the public about vaccines and other measures for preventing infectious diseases such as COVID, HIV, and HPV.

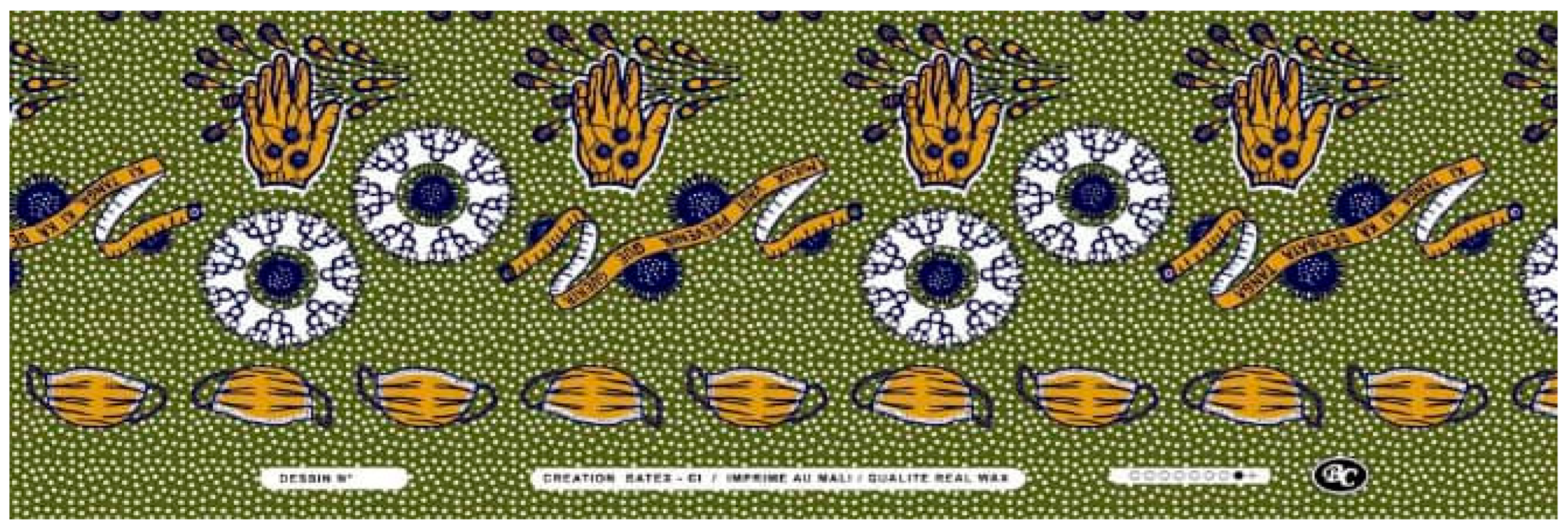

Materials for the public education intervention (primarily focused on COVID for this project) included: 1) two posters, 2) radio announcements, 3) a story-telling cloth design that adapted from prior GAIA VF organized vaccine promotion campaigns and produced by a local textile plant (Figure 1), and 4) a survey on COVID-19 vaccine attitudes and beliefs. Radio announcements began in September 2021 to advertise the intervention (A sample of the dialogue is provided in the Supplemental Materials). The posters provided descriptions of how COVID-19 is transmitted and instructions on how to protect yourself from contracting the virus in both French and Bambara along with illustrations. The posters were displayed at each of the clinics and were publicly visible throughout the intervention (Supplemental Figure S2).

Figure 1.

Story-telling Cloth.

Figure 1.

Story-telling Cloth.

The story-telling cloth is a communication method that GAIA VF developed and used in a previous prevention/education campaign to inform the community about HPV and the risks of cervical cancer (Crippin et al., 2022). The story-telling cloth acts as a unifying storyboard for CHWs and HCPs during the public education intervention. The fabric was distributed to both CHWs and HCPs and was used to sew outfits, handbags, and other wearable items (Supplemental Figure S3). CHWs wore the story-telling cloth during education events as a tool to explain the message and HCPs wore the cloth at the clinic while surveying participants.

GAIA VF team members developed a survey to assess the impact of the intervention, understand perceptions of COVID-19 and its vaccines, capture sources of trusted information in the community, and evaluate the impact of misinformation (Osuagwu et al., 2023). See Supplemental information for information about the drafting process, IRB approval and copies of the surveys.

Public education intervention activities began on October 1, 2021, after COVID-19 vaccines became more widely available in Mali. Visits to the 13 community clinics participating in the project confirmed that vaccines were available at no cost at each site. While the public education intervention was ongoing in the community, trained nurses wearing the story-telling cloth orally surveyed community members who visited their clinic about their sources of information about vaccines, vaccine practices in their own family, and their confidence in vaccine safety. They asked any adult over 18 to participate, and upon receiving verbal consent, administered the survey to each participant individually. Consenting participants were surveyed regardless of whether they had participated in a public education intervention activity or not. Given the high rates of illiteracy, literacy was not a prerequisite for study participation. Consent was given by thumbprint or signature and survey responses were obtained orally for all participants. Participants were able to withdraw from study participation at any time and were informed that they could skip any question they did not want to answer.

2.2. Healthcare Provider Training

In addition to the multicomponent public education intervention, this study also captured the impact of targeted training for HCPs. 70 HCPs participated in specialized infectious disease training hosted by four infectious disease specialists from the Ministry of Health and the principal hospital in Bamako. Each presenter developed their own curriculum, slideshows, and led their portion of the training events. A photo of the training is available as Supplemental Figure S4.

GAIA VF developed a survey to assess whether this supplemental, targeted training was linked with increased HCP knowledge and confidence in vaccines. Pre- and Post training surveys were administered to participants who gave consent. (See Supplemental information for information about the drafting process, Human Studies approval, consent procedures and copies of the surveys). In total, 70 healthcare providers participated in the training and 140 surveys were collected.

2.3. Data Inputs and Analysis

The National Center for Immunization provided Malian COVID-19 vaccination data. That data was disaggregated by Commune for a comparative analysis of study sites versus non-study sites. A project manager in Mali input the community survey data using Google Forms. GAIA’s US-based team exported that data into an excel spreadsheet for analysis. The US team also coded the HCP surveys directly into a spreadsheet and conducted descriptive and comparative analyses using maximum likelihood estimate techniques to determine statistical significance.

3. Results

A total of 3,445 community members and 140 Healthcare Providers participated in the study. Demographic data for all participants are included in Supplemental Table S1. Most community participants were female, had children, and had little to no formal education. Participating HCPs were primarily female midwives and nurses. A key finding was that community outreach was essential for improving vaccine confidence. As shown in Supplemental Figure S5, the majority of community outreach participants were more confident about vaccines following their participation in the intervention.

3.1. Public Education Intervention

3,445 surveys were collected during the outreach events. The vaccine confidence questions focused on the vaccine use during the current pandemic (COVID-19) and the COVID vaccine. Most community participants showed had heard of COVID-19 (87%; N=2986/3445) and agreed it was a major health risk (73%; N=2511/3445), but only 54% (N=1849/3445) said that they knew what caused COVID-19 transmission. When asked if they followed COVID-19 prevention guidelines (i.e., mask wearing, hand washing, and social distancing), about 68% (N=2330/3445) said that they did. Only 24% (N=833/3445) of respondents had ever been tested for COVID-19 and only 21% (N=736/3445) were vaccinated. 56% of unvaccinated respondents said they would agree to be vaccinated. Lack of confidence in the vaccine was a major reason for avoiding vaccination: those respondents who were unwilling to be vaccinated reported “I am worried about side effects” (47%; N=209/445) or “I don’t think it will be prudent” (25%; 110/445). Table 1 shows that most respondents reported hearing misinformation about COVID and/or COVID-19 vaccines. A smaller proportion of the population (between 2% to 19%) believed the rumors they heard were true or possible.

Table 1.

COVID-19 Vaccine Rumors.

Table 1.

COVID-19 Vaccine Rumors.

| Have you heard these rumors about COVID-19 Vaccines? |

|---|

| |

Vaccine contains microchips |

Vaccine contains magnets |

Vaccine will change my DNA |

Vaccine will cause COVID-19 |

Vaccine will turn me into a zombie |

| Never heard |

34% |

35% |

33% |

26% |

37% |

| Heard but don’t believe |

45% |

47% |

48% |

52% |

49% |

| Heard and thinks it’s possible |

16% |

15% |

17% |

19% |

12% |

| Heard and believe |

4% |

3% |

2% |

3% |

2% |

Table 2 shows the odds ratios from three logistic regression models estimating the relationship between relevant independent variables and COVID testing and vaccination. Education level was a strong predictor of prior testing, vaccination, and willingness to be vaccinated for COVID-19. A 1-unit increase in education led to a 24.5% increase in the odds of being previously tested, a 36.8% increase in the odds of being previously vaccinated, and a 20.1% increase in the odds of being willing to be vaccinated. Older individuals were more likely to have been vaccinated and be willing to accept vaccination, although age was not a statistically significant predictor of testing. Gender and religion both appeared to play a role in vaccine uptake. Men were 40% more likely to have been previously vaccinated than women were, but sex had no statistically significant relationship with prior testing or willingness to be vaccinated. Finally, a 1-unit increase in religiosity increased the odds of being previously tested and vaccinated by 9.1% and 20.5% respectively but decreased the odds of being willing to be vaccinated by 1.2%.

Table 2.

Odd Ratios for COVID-19 Testing and Vaccination.

Table 2.

Odd Ratios for COVID-19 Testing and Vaccination.

| |

Prior COVID-19 Testing |

Prior COVID-19 Vaccination |

Willingness to be Vaccinated |

| Sex |

1.099

(.129) |

1.399

(.158)** |

.882

(.108) |

| Age |

1.004

(.005) |

1.037

(.005)*** |

1.018

(.005)*** |

| Children |

1.300

(.172)* |

1.029

(.135) |

.864

(.112) |

| Education |

1.245

(.044)*** |

1.368

(.049)*** |

1.201

(.044)*** |

| Religiosity |

1.091

(.052)* |

1.205

(.060)*** |

.880

(.041)** |

| Exposed to HCP Discussion |

|

|

1.058

(.057) |

| Exposed to Fabric |

|

|

1.036

(.050) |

| Exposed to Public Education Event |

|

|

1.237

(.065)*** |

| Exposed to Poster |

|

|

1.015

(.048) |

| Exposed to Radio Advertisement |

|

|

1.223

(.059)*** |

| |

| Constant |

.155

(.037)*** |

.035

(.009)*** |

.382

(.109)*** |

| Number of Observations |

2,957 |

3,117 |

2,427 |

| Psuedo R2

|

.066 |

.190 |

.123 |

Notes: *p<.1 **p<.05***p<.01. All dependent variables coded 0/1 for no/yes. Fixed effects by clinic included but not presented. Standard error in parentheses under estimates.

Sex: 0=female 1=male. Children: 0=none 1=have children. Education 0=no schooling 1=primary schooling 2=secondary schooling 3=tertiary schooling 4=university. Religiosity: 0=never attend services 1=attend services for holidays 2=attend services monthly 3= attend services weekly 4=attend services daily. Exposure 0=none 1=exposed. |

The survey also included a series of questions asking how often the respondent trusted various groups for vaccination advice. Local healthcare providers were a major source of trusted information. There was a striking difference between the numbers of community-based participants who always trusted their community healthcare provider (2165) versus the government health authorities (976). Similarly, only 127 individuals said that they never trust vaccination advice from their community health provider while 633 never accept the advice of government health authorities. The full table of responses is included in Supplemental Table S2.

Table 3 presents the odd ratios from two logistic regression models estimating the relationship between relevant independent variables and a respondent’s trust in the vaccination advice of their local community clinic HCPs and government health authorities. Men were 36% less likely to trust the advice of their local HCP compared to women, but there was no distinguishable difference between men and women when it came to trusting government health authorities. Education level, exposure to a HCP discussion, public health event, and radio announcement all predict both trust in local HCP and government health authorities. A 1-unit increase in education increased the odds of trusting your local HCP for vaccination advice by 41.3% and the odds of trusting the government health authorities by 11.1%. Being exposed to a public education event increased the odds of trusting local HCP by 51.4% and the odds of trusting the government health authorities by 21.5%. Exposure to the “story-telling” fabric was positively correlated with trust in government health authorities, but not local HCP. Exposure to a public health event and exposure to the fabric are highly correlated leading to the possibility of multicollinearity issues in the model.

Table 3.

Odds Ratios for Who You Trust for Vaccination Advice.

Table 3.

Odds Ratios for Who You Trust for Vaccination Advice.

| |

Trust Community HCP |

Trust Government Health Authorities |

| Sex |

.642

(.161)* |

1.029

(.160) |

| Age |

1.016

(.012) |

1.003

(.006) |

| Children |

1.229

(.341) |

1.205

(.195) |

| Education |

1.413

(.124)*** |

1.111

(.051)** |

| Religiosity |

.853

(.089)* |

1.027

(.058) |

| Exposed to HCP Discussion |

1.749

(.183)*** |

1.293

(.083)*** |

| Exposed to Fabric |

.969

(.108) |

1.280

(.077)*** |

| Exposed to Public Education Event |

1.514

(.163)*** |

1.215

(.081)*** |

| Exposed to Poster |

.904

(.100) |

.972

(.056) |

| Exposed to Radio Advertisement |

1.478

(.154)*** |

1.422

(.085)*** |

| Constant |

1.064

(.595) |

.797

(.279) |

| |

| Number of Observations |

2,966 |

2,959 |

| Psuedo R2

|

.260 |

.343 |

|

Notes: *p<.1 **p<.05***p<.01. All dependent variables coded 0/1 for no/yes. Fixed effects by clinic included but not presented. Standard error in parentheses under estimates.Sex: 0=female 1=male. Children: 0=none 1=have children. Education 0=no schooling 1=primary schooling 2=secondary schooling 3=tertiary schooling 4=university. Religiosity: 0=never attend services 1=attend services for holidays 2=attend services monthly 3= attend services weekly 4=attend services daily. Exposure 0=none 1=exposed. |

3.2. Healthcare Provider Training Intervention

Like community participants, healthcare providers attending a training event were asked specific questions about COVID-19. There was little to no difference in their responses before and after each training. Generally, about 79% (111/140) of healthcare providers had received the COVID-19 vaccine and 68% (95/140) of surveyed healthcare providers knew someone (family member, friend or patient) who had been seriously ill or died from COVID-19. Most healthcare providers agreed that COVID was a major public health threat, still existed in Mali, survives in hot climates, and can be serious, but only 61% (85/140) believed that the official COVID-19 figures reflected the reality of the disease in Mali. The full responses to COVID-19 questions asked to healthcare providers is included in Supplemental Table S3.

The percentage of HCPs who strongly agree that “Vaccines are safe,” “Vaccine are effective,” and “Vaccines are important for children” increased in the survey given after the training compared to the survey before the training. Trust in government health recommendation also increased in the post-educational session survey. These differences were all statistically significant with p-values below .05.3 Full results are in Supplemental Figure S5. Vaccine knowledge also increased from the pre to post survey. The survey contained a series of knowledge questions asking HCPs to match 13 childhood vaccines to the illnesses they help prevent and to identify the type of vaccines available for HPV and COVID-19 for a total of 15 questions. Before the training HCP answered 8.8 (59%) of them correctly, after the training, they answered 10.3 (69%) correctly. This difference is statistically significant with p<.05.

When asked whom they trusted for vaccination advice, most local healthcare providers trusted the government health authorities (54%; N=76/140) with only a single HCP indicating that they do not trust government health recommendations (N=1/70). Other common sources of trusted information about vaccination included the local healthcare provider’s supervisor (24%; N=33/140), family & friends (17%; N=24/140), professors/scientists (12%; N=17/140) and local political representatives (11%; N=16/140).

4. Discussion

One of the most important findings from this research is that a successful vaccination campaign must be led by trusted sources of information. The participants in this study said that they accept vaccination advice from a wide range of actors. Previous studies demonstrated that local healthcare providers were the key to increasing vaccine confidence among community members (Crippin et al., 2022). This study provides even more evidence supporting that observation, as far more respondents (63%; N=2165/3445) said that they always trust the recommendations of their community HCP (e.g., doctors, nurses, and midwives that run their local clinic). Given the level of inconsistency in government leadership during the pandemic, it is not surprising that so few people trusted the government as a source of health information compared to their local community healthcare providers. This may be due to the fact that while the President and Minister of Health changed during the course of the pandemic, local doctors largely remained the same.

Data from the DRS shows that Commune I, where this study took place, has the lowest vaccination rates in all of Bamako. The predicted probability of being tested for or vaccinated against COVID-19 was about 1.5 and 3 points higher for individuals with higher levels of education than ones with no education. Other studies have reported a correlation between low vaccine confidence in low income, marginalized populations (Ozoh et al., 2023; Pengpid et al., 2022). Community members living in Commune I in Bamako are the poorest, least educated residents living in the city of Bamako. Indeed 25% (862/3410) of our survey participants had no formal schooling at all.

However, there was no correlation between education level and knowledge about COVID-19. Those with no reported formal education were just as likely as those with a high school-level education to have heard of the virus, consider it a major health risk, know its causes, and practice safety guidelines. This is perhaps due to the use of a multicomponent intervention design, which included educational materials that did not require the ability to read or write. As the local language, Bambara, is more commonly spoken than written, low literacy poses a particular challenge for public health outreach in Mali. The World Bank reports that only 22.1% of women and 40.4% of men can read (World Bank Group, 2020). In comparison, the region of Sub-Saharan Africa has a female literacy rate of 61.4% and male literacy of 74.2%. The story-telling cloth and public education intervention combination ensured that even community members with no schooling at all could access important health information.

The survey results also showed that many well-known misinformation themes had emerged based on videos that were widely circulated on WhatsApp and other social media platforms. Misinformation has also been reported to have a negative effect on COVID-19 prevention measures in other LMIC (low to middle-income countries) in West Africa such as Cameroon and Ghana. There was no correlation in this study between education-level and belief in common rumors/misinformation about the COVID-19 vaccine suggesting that the well-educated were equally exposed to misinformation as those with no formal schooling.

The findings also underscore the importance of training for HCP. In this study, HCP knowledge increased meaningfully after exposure to training. Given community members’ trust in HCP and lack of trust in the government, efforts to train HCP likely play a significant role in vaccine confidence and vaccination rates.

5. Conclusion

There are two main conclusions to be drawn from this study. First, community members, especially women, seem to trust the advice of their local clinic healthcare practitioners more than the official government healthcare authorities. Thus, vaccine campaigns should be led by informed local healthcare providers. Discussions with their local healthcare providers was the single most effective element of this campaign at increasing vaccine confidence, followed closely by public education intervention. Actively training front line providers about vaccines (especially new vaccines such as the COVID vaccine and the HPV vaccine) remains a high impact activity that is likely to improve vaccine confidence overall. Fortunately, community-level healthcare practitioners do trust the government health authorities since they are typically the first stop for new healthcare information. Second, public education intervention appears to be effective in increasing knowledge and vaccine confidence. Maintaining the vaccine confidence of healthcare providers will clearly have an impact on vaccine confidence among these individuals, and that is also likely to have a positive impact on vaccine uptake in the general population. Furthermore, as Mali prepares for HPV vaccination campaigns, an investment in vaccine education prior to the mass vaccination campaign will surely have a significant impact on future generations of the people of Mali.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org, Supplemental Figures S1-26; Tables S1-S3. Appendix A. Supplemental Tables, Figures, & Additional Information about Training. Appendix B. Copies of Surveys. Appendix C. Copies of IRB Approvals.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, T.C., S.B, and ADG.; methodology, TC., S.B, OAK, AKD, KT, PK, IT, and ADG; validation, TC, HM, MM.; formal analysis, TC., S.B, ADG; resources, TC, ADG.; data curation, TC, HM, MM.; writing—original draft preparation, TC, MM, ADG.; writing—review and editing, TC., S.B, OAK, AKD, KT, PK, IT, and ADG.; visualization, TC.; supervision, ADG.; project administration, TC; funding acquisition, ADG. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.”

Funding

Supported in part by a research grant for Medical Scientist Investigation Protocol (MISP 60675) from Investigator-Initiated Studies Program of Merck Sharp & Dohme LLC. The opinions expressed in this paper are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of Merck Sharp & Dohme LLC.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The protocol design, surveys, and consent forms were reviewed and approved by a US-based institutional review board “E&I” on September 2, 2021 (Study number 21116) and, following a change of ownership or merger with Salus, responsibility for IRB supervision was accepted by the Salus IRB on September 30, 2022 (Study number 21116). This study was also registered and approved by the ethics committee of the Faculty of Medicine and Odonto-Stomatology at the University of Bamako (UTTSB), Bamako, Mali, on July 27, 2021, under the number: 2021/182/CE/USTTB. The objectives, benefits, and risks of participating in the study were explained to all participants in Bambara or French; the community surveys were verbal and provided in Bambara. Informed consent was obtained prior to participation in the study, as per approved protocol. The E&I IRB Approval, Update, and USTTB IRB Approval are included in the Supplemental Material Part 3.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study. The Informed Consent Form is included in the Supplemental Material Part 3.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data for this study was collected in Google forms. Access to the raw data is available upon request (TCrippin@ (at)GAIAVaccine.org). Other materials are provided in the supplemental data for this publication..

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to express their sincere gratitude to the many healthcare providers and community outreach workers who participated in this project. The authors are also grateful for the assistance of the Malian health authorities who supervised the trainings.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

Notes

| 1 |

|

| 2 |

Keniero is located about 70 kilometers outside of Bamako in the district of Siby. |

| 3 |

Vaccines are safe p<.001; Vaccines are important for children p<.01; Vaccines are effective p<.05; I trust the government for healthcare recommendations p<.05 |

References

- Cissoko, M., Landier, J., Kouriba, B., Sangare, A.K., Katilé, A., Djimde, A.A., Berthé, I., Traore, S., Thera, I., Hadiata, M., Sogodogo, E., Coulibaly, K., Guindo, A., Dembele, O., Sanogo, S., Doumbia, Z., Dara, C., Altmann, M., Bonnet, E., Balique, H., Sagaon-Teyssier, L., Vidal, L., Sagara, I., Bendiane, M.K. (2020). SARS- CoV- 2 seroprevalence and living conditions in Bamako (Mali): a cross- sectional multistage household survey after the first epidemic wave, 2020. BMJ Open. 13:4. [CrossRef]

- Crippin, T., Tounkara, K., Squibb, E., Beseme, S., Barry, K., Sangare, K., Coulibaly, S., Fané, P., Bagayoko, A., Koita, O.A., Teguété, I., De Groot, A.S. (2022). A story-telling cloth approach to motivating cervical cancer screening in Mali. Frontiers in Public Health. 10. [CrossRef]

- Crippin, T., Tounkara, K., Munir, H., Squibb, E., Piotrowski, C., Koita, O. A., Teguété, I., De Groot, A. S. (2024). Our Daughters—Ourselves: Evaluating the Impact of Paired Cervical Cancer Screening of Mothers with HPV Vaccination for Daughters to Improve HPV Vaccine Coverage in Bamako, Mali. Vaccines. 12:9. [CrossRef]

- De Groot, A.S,, Tounkara, K., Rochas, M., Beseme, S., Yekta, S., Diallo, F.S., Tracy, J.K., Teguete, I., Koita, O.A. (2017). Knowledge, attitudes, practices and willingness to vaccinate in preparation for the introduction of HPV vaccines in Bamako, Mali. PLoS One. 12:2. [CrossRef]

- Ly, B.A., Ahmed, M.A.A., Millimouno, T.M., Cissoko, Y., Faye, C.L., Traoré, F.B., Diarra, N.H., Toure, M., Telly, N., Sangho, H., Doumbia, S. (2022). Information about COVID-19: lessons learned from Mali. Health Sciences and Disease. 23:11. [CrossRef]

- Maiga, A.I., Saliou, M,. Kodio, A., Traore, A.M., Dabo, G., Flandre, P., Fofana, D.B., Ammour, K., Tra, N.O.M.E., Dolo, O., Marcelin, A.G., Todesco, E. (2022). High SARS-CoV-2 seroprevalence among health care workers in Bamako referral hospitals: a prospective multisite cross-sectional study (ANRS COV11). Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 28(6), 900-902. [CrossRef]

- Osuagwu, U.L., Mashige, K.P., Ovenseri-Ogbomo, G., Envuladu, E.A,, Abu, E.K., Miner, C.A,, Timothy, C.G., Ekpenyong, B.N., Langsi, R., Amiebenomo, O.M., Oloruntoba, R., Goson, P.C., Charwe, D.D., Ishaya, T., Agho, K.E. (2023) The impact of information sources on COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy and resistance in sub-Saharan Africa. BMC Public Health. 23:38. [CrossRef]

- Ozoh, O.B., Akinkugbe, A.O., Olukoya, M.A., Adetifa, I.M.O. (2023). Enablers and barriers to COVID-19 vaccine uptake in an urban slum in Lagos, Nigeria: informing vaccine engagement strategies for the marginalized. Int. Health. 15:5. [CrossRef]

- Pengpid, S., Peltzer, K., Sathirapanya, C., Thitichai, P., Faria de Moura Villela, E., Rodrigues Zanuzzi, T., de Andrade Bandeira, F., Bono, S.A., Siau, C.S., Chen, W.S., Hasan, M.T., Sessou, P., Ditekemena, J.D., Hosseinipour, M.C., Dolo, H., Wanyenze, R.K,, Nelson Siewe Fodjo, J., Colebunders, R. (2020). Psychosocial factors associated with adherence to COVID-19 preventive measures in low-middle- income countries, December 2020 to February 2021. Int. J. Public Health. 67. [CrossRef]

- Téguété, I., Dolo, A., Sangare, K., Sissoko, A., Rochas, M., Beseme, S., Tounkara, K., Yekta, S., De Groot, A.S., Koita, O. A. (2017). Prevalence of HPV 16 and 18 and attitudes toward HPV vaccination trials in patients with cervical cancer in Mali. PloS One. 12:2. [CrossRef]

- World Bank Group. (2020) Mali Featured Indicators. https://genderdata.worldbank.org/countries/mali/. Accessed 30.03.2025.

- World Bank. Mali- COVID-19 High Frequency Phone Survey of Households, 2020. www.microdata.worldbank.org. Accessed 30.03.2025.

- World Health Organization. (2023). Mali COVID-19. https://www.who.int/countries/mli. Accessed 30.03.2025.

- World Health Organization. (2023). COVID-19 Dashboard. https://data.who.int/dashboards/covid19/vaccines?n=c. Accessed 30.03.2025.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).