Introduction

Continuous-flow left ventricular assist devices (CF-LVAD) have become a standard treatment for individuals with heart failure and reduced ejection fraction (HFrEF), yet their utilization and outcomes differ markedly between sexes. Although women comprise approximately 40% of the HFrEF population, they represent only around 20% of CF-LVAD recipients [

1,

2].

Recent advancements in CF-LVAD technology, tailored to better suit female physiology, have shown promise in improving survival rates among women [

3,

4,

5]. However, women after LVAD implantation continue to have higher rates of adverse events, such as bleeding and infections than men [

6,

7,

8,

9]. Women are also more likely than men to experience their first rehospitalization within 1-year post-implant (72.1% vs. 68.9%) [

7].

Psychosocial factors, such as substance abuse and psychiatric diagnoses, have been identified as significant determinants of post-implant outcomes in both sexes [

10,

11,

12]. Particularly in women, the presence of preimplant psychosocial risk was associated with a 15% increase in first hospitalization rates, compared to 3% in men. This association was independent of device-related (e.g., axial vs. centrifugal flow) and clinical risk factors (e.g., primary diagnoses, differences in medication management) [

7].

Notably, these findings only account for patients’ first hospitalization after LVAD implantation. However, patients on average experience two hospitalizations only within the first year after implant [

4,

13], with longer follow-up data rarely reported. These recurrent hospitalizations are associated with increased patient burden, higher mortality risk, and rising healthcare costs [

14,

15].

Findings regarding the role of female sex for recurrent hospitalizations are inconclusive. While women were found to have a higher risk of 30-day readmissions compared with men [

16,

17], no significant sex differences were observed in days alive and out of hospital [

18] or length-of-stay [

19]. These studies, however, differed in follow-up durations and applied statistical approaches that, unlike multi-state modeling, did not adequately account for recurrent events. Moreover, these studies did not consider pre-implant psychosocial risk factors.

This study aims to address these gaps using a multi-state analysis of recurrent hospitalizations in a large dataset from the Interagency Registry for Mechanically Assisted Circulatory Support (INTERMACS) registry. The objectives are to 1) describe sex-specific patterns in cumulative transition rates (e.g., home to hospital); and to 2) analyze the interaction of preimplant psychosocial risk and sex on cumulative transition hazards from home to hospital, while adjusting for clinical, demographic, and behavioral covariates. We hypothesize that women will experience higher transition rates from home to hospital compared to men, particularly due to the impact of preimplant psychosocial risk. In addition, we explore the probability for being in the state “hospitalization” throughout the follow-up, the mean number of hospitalizations, and cumulative average lengths of hospital stay at each possible time point of the observation, stratified by sex and preimplant psychosocial risk.

Material and Methods

Study Population

INTERMACS is a North-American prospective registry enrolling patients with advanced heart failure undergoing durable mechanical circulatory support. Prior to implantation, the registry records clinical, demographic, behavioral, and psychosocial patient characteristics. Patients are monitored post-implantation for adverse events and rehospitalizations until they experience death, undergo heart transplantation, or recover [

20]. This INTERMACS analysis included de-identified data from adult patients aged over 18 years at the time of implantation. Informed consent was obtained from all participants before implantation by the participating centers. Patients who received pulsatile-flow LVAD, right ventricular assist device, biventricular assist device, or total artificial hearts were excluded. Data from 20,123 patients (21.3 % women), registered between July 2006 to December 2017, with primary CF-LVAD were analyzed. Data were accessed through the Biological Specimen and Data Repository Information Coordinating Center (BioLINCC). This study received approval from the Institutional Review Board at Trier University (amendment 2024/04/26 to EK no. 66/2018).

Pre-Implant Characteristics and Psychosocial Risk

In addition to clinical factors [

6,

10], demographic and behavioral variables such as age, race, employment status, marital status, educational attainment, BMI, and smoking status were included in the analysis. The psychosocial variables of INTERMACS’

concerns and contraindications for transplant were limited social support, limited cognition/understanding, alcohol abuse, drug abuse, severe depression, other major psychiatric diagnosis, and repeated noncompliance, covering all five key psychosocial domains as suggested by the Consensus Statement on psychosocial evaluation [

21,

22]. Based on previous approaches [

7,

10], a binary psychosocial risk variable was constructed (present = 1, not present = 0). Psychosocial risk was coded “present” if at least one of the above conditions was identified in a patient preimplant.

Outcome Measurements

In recurrent time-to-event analysis, some states, such as hospitalizations, can occur multiple times and are referred to as `recurrent' events. Other states, such as death, are considered absorbing because once patients transition to an absorbing state, they are no longer at risk for subsequent events. This competing risk framework within the recurrent event analysis ensures that changes in risk sets are appropriately accounted for. Considering all observed events, including all recurrent hospitalizations and absorbing states – rather than focusing solely on the first event per patient, as is common in traditional time-to-event analyses, provides a more comprehensive understanding of disease progression and enhances statistical power [

23,

24].

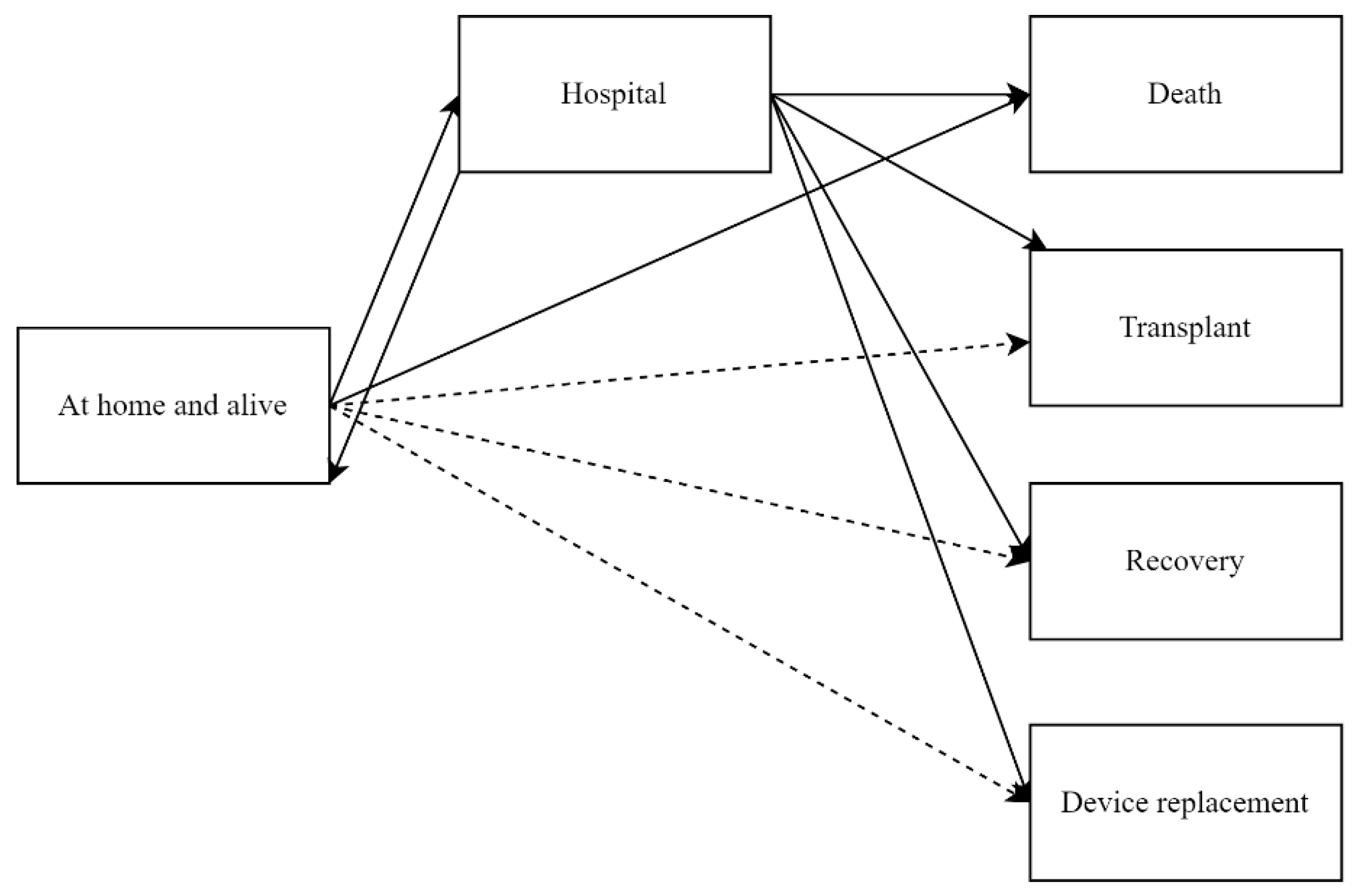

In our multi-state model (

Figure 1), we defined ‘alive and at home’ and ‘hospitalized’ as the recurrent states of interest. Thus, our outcomes of interest are all recurring hospitalizations of all causes for a patient during the observation period. Each event ”rehospitalization“ represent a change in status from being ‘alive and at home’ to being ‘hospitalized’, followed by a return to the ‘alive and at home’ state. The model also accounts for the transitions from hospital to the absorbing states death, heart transplantation, device replacement due to complications, device explantation due to recovery, and from home to death. Time-to-event was calculated as the time from CF-LVAD implantation until one of these outcomes occurred, accounting for recurrent states, until the end of follow-up.

Statistical Analysis

We applied the semiparametric imputation procedure [

25] to handle missing data in all covariates, including psychosocial risk, as recommended when missing data are less than 30%. Sensitivity analyses were conducted using complete case models, which showed consistent results compared to the single-imputed model.

Continuous variables were summarized using means and standard deviations, categorical variables were described with frequencies and percentages. Sex differences in pre-implant characteristics were assessed using t-tests for continuous variables and chi-square tests for categorical variables.

Recurrent hospitalizations were analyzed applying multi-state models. Cumulative partly conditional transition rates, calculated under the condition of being at risk for the event shortly before time

t, were estimated for each transition in

Figure 1 using the nonparametric Nelson-Aalen estimator in non-Markov models [

26,

27].

To estimate the effects of covariates on the transition hazard from home to hospitalizations, we utilized the semiparametric Andersen-Gill model. To assess the Markov assumption—which posits that the occurrence of the next event is independent of previous events given the current state and time—we included the number of previous events as a covariate. After having observed a violation of this assumption, we applied the proportional rate model proposed by Gosh and Lin [

24] and compared its results from univariable analyses with those of the Andersen-Gill model. As the results were similar, and the Gosh and Lin model required excessive computational resources, we proceeded with the Andersen-Gill model for multiple analyses. Results are reported as hazard ratios (HR) with corresponding 95% confidence intervals (CI). The multivariable regression model for transition hazards from home to hospitalizations included the following variables: sex, psychosocial risk (yes vs. no), interaction between sex and psychosocial risk, age, race, working for income, marital status, education, BMI, and smoking status. Clinical covariates were device strategy, primary diagnosis, time since diagnosis, previous cardiac surgeries, left ventricular end-diastolic diameter (LVEDD), INTERMACS profile, pump type (axial vs. centrifugal), implantable cardioverter-defibrillator (ICD), pulmonary hypertension, albumin, bilirubin, creatinine, BUN, platelet count, severe diabetes, and medications.

To provide probabilities for recurrent hospitalizations in addition to cumulative transition rates and hazards, we estimated marginal probabilities based on the Aalen-Johansen estimator, which can be utilized even when the Markov assumption is not met (see above) [

27,

28]. These estimates include state occupation probabilities which represent the likelihood of a patient being in a particular state, such as being hospitalized or in any absorbing state, at a given time. Based on these probabilities, the mean number of hospitalizations and the cumulative average length of hospital stay were calculated and stratified by sex and psychosocial risk (yes vs. no).

Statistical significance was set at

p<0.05. All analyses were performed using R, version 4.3.3, including the packages,

mice, mvna, survival, etm, and

reReg [

29].

Results

Sex Differences Pre-Implant

Of the 20,123 patients receiving a primary CF-LVAD, 4,282 (21.3%) were female. There were differences between women and men pre-implant (

Table 1). Women were less likely to have psychosocial risk than men (17.5% vs. 21.4%, < .001) [

7]. Specifically, women were less likely than men to have a history of substance use (tobacco, alcohol, drugs), but they were more likely to be current smokers and more often depressed. However, there were no sex differences in limited social support and limited cognition/understanding [

7].

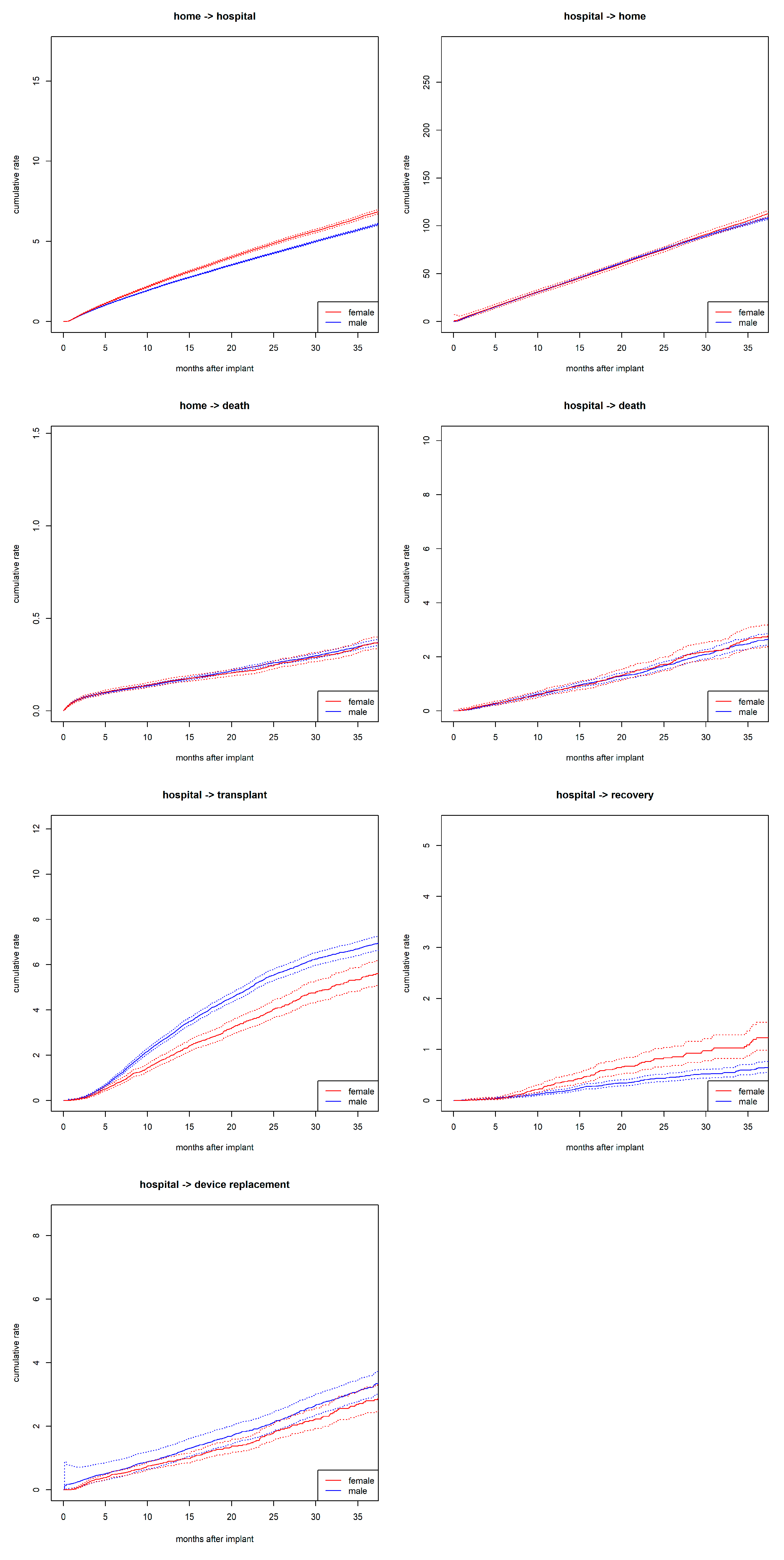

During the observation period, >135,000 transitions were recorded. Among these, 60,869 were rehospitalizations—transitions from home to hospital. This included 14,018 rehospitalizations in women and 46,851 in men. Women had increased rates for transitioning from home to hospital compared to men (

Figure 2). Additionally, women had higher rates for device explant due to recovery compared to men but lower rates for undergoing transplantation while hospitalized. No sex differences were observed in the transition rates from home to death or from hospital to death. Independent of sex, discharge from the hospital is the most likely, while recovery within the hospital is the least likely of all transitions.

In the multiple regression models, female sex [HRadj 1.11, 95% CI (1.06-1.16),

p<.001], psychosocial risk [HRadj 1.07, 95% CI (1.02-1.12),

p=.003], and the interaction of both [HR

adj 1.11, 95% CI (1.01-1.22),

p=.036] were significantly associated with increased transition hazards for home to hospital, even after controlling for clinical, demographic, and behavioral covariates (

Table 2).

Demographic and behavioral risk factors associated with increased transition hazards for home to hospital were not working for an income [HRadj 1.05, 95% CI (1.01-1.10),

p=.021], obesity [HRadj 1.09, 95% CI (1.05-1.13),

p<.001], currently smoking [HRadj 1.10, 95% CI (1.02-1.18),

p=.013], and smoking history [HRadj 1.07, 95% CI (1-03-1.11),

p<.001] (

Table 2). Higher educational attainment was associated with decreased transition hazards from home to hospital [HRadj 0.92, 95% CI (0.87-0.97),

p=.004].

Probability of Being Hospitalized

The state occupation probability for being in hospital decreased during follow-up and the probability of being hospitalized was higher for women than for men during the first 25 months post-implant. There were no sex differences in the state occupation probability of being in any absorbing state (see

Figures S1 and S2).

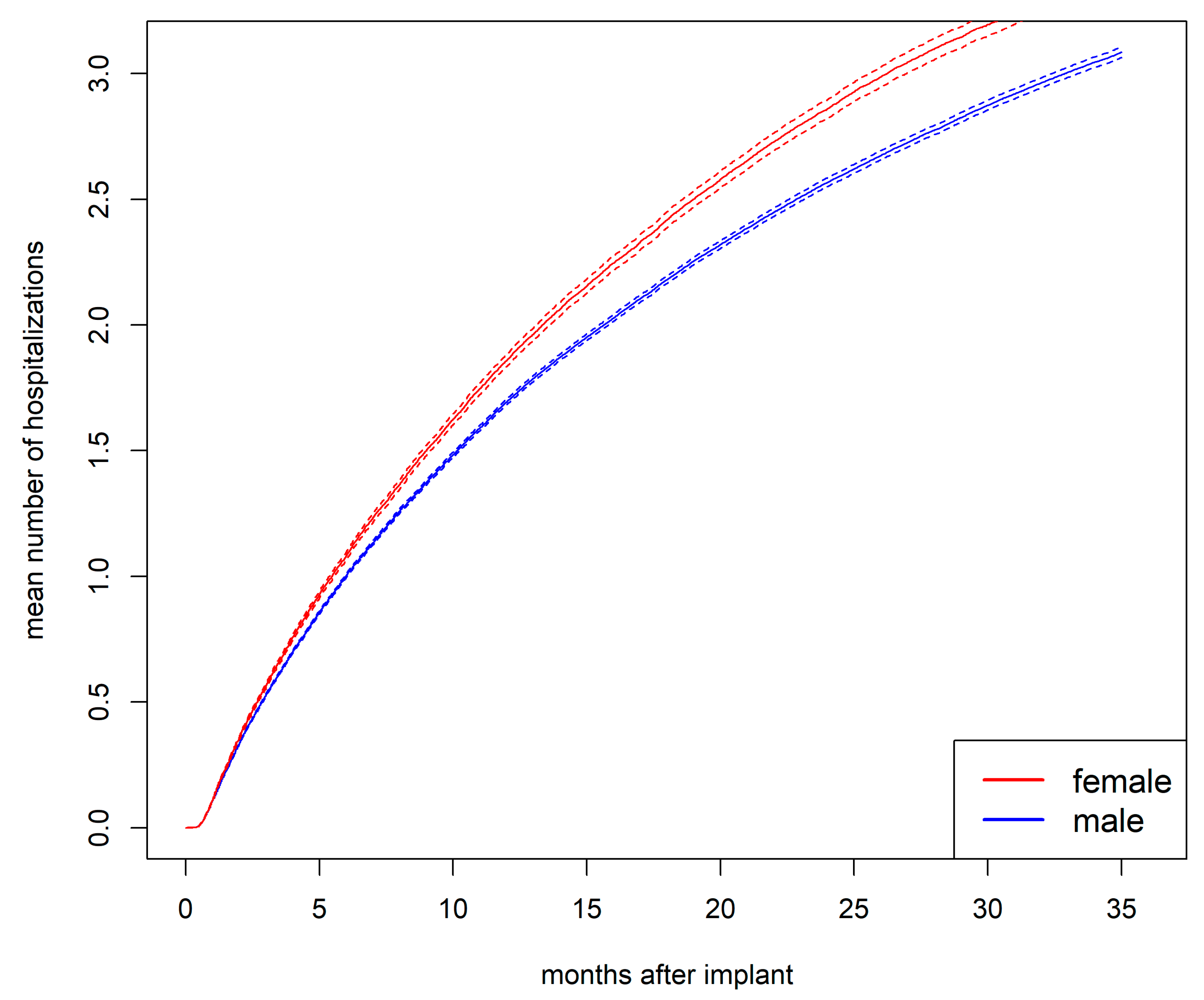

Mean Number of Hospitalizations

The mean number of hospitalizations was higher for women than for men (

Figure 3). This difference cannot be explained by men entering an absorbing state earlier and thus avoiding rehospitalizations, as no sex differences were observed in the state occupation probability of being in an absorbing state (see

Figure S2). After 1 year, the mean number of hospitalizations was 1.9 for women and 1.7 for men (

p<.001). After 2 years, it was 2.9 for women and 2.6 for men (

p<.001).

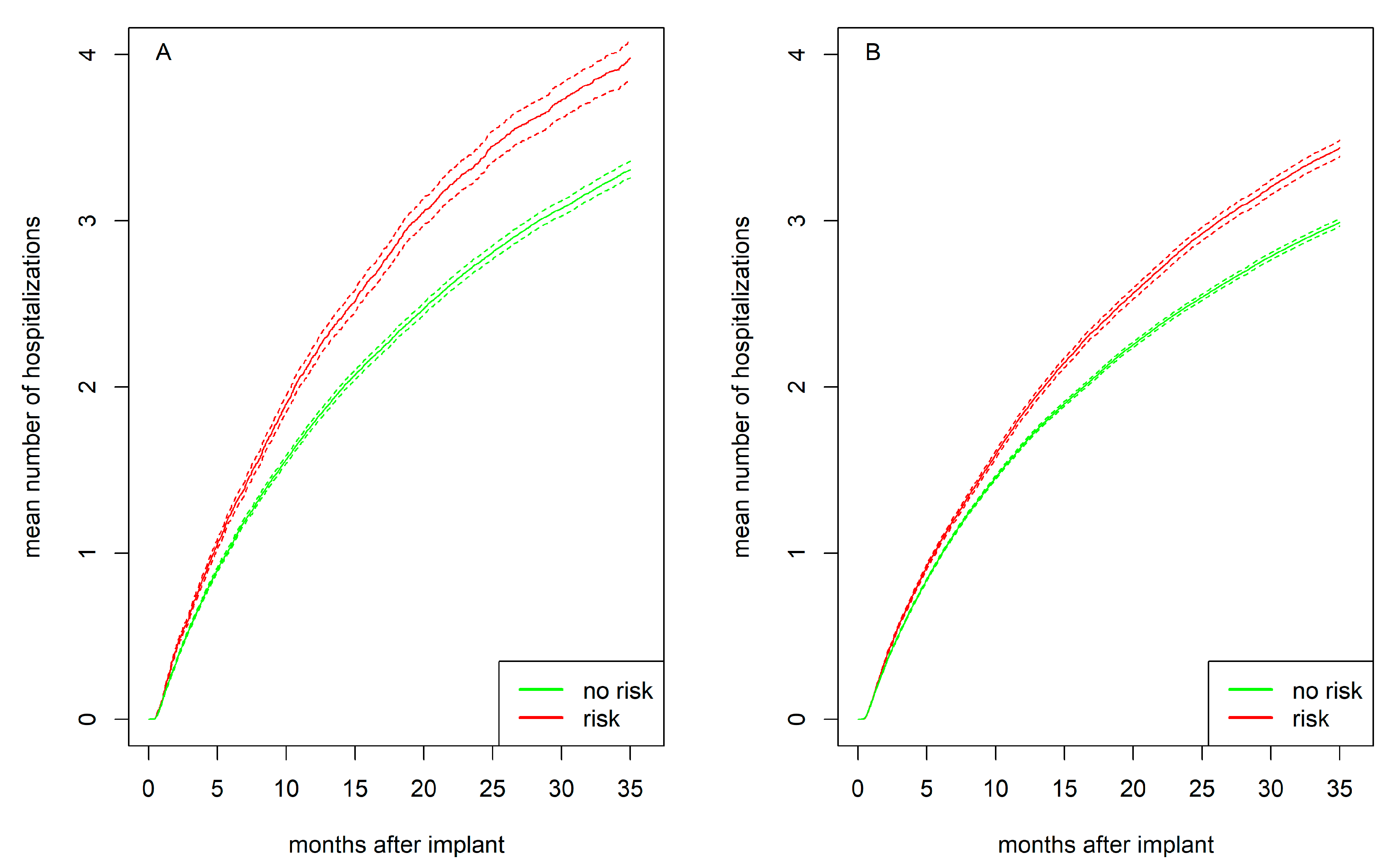

Figure 4 presents the mean number of hospitalizations for women and men separately, stratified by psychosocial risk. Individuals with psychosocial risk experienced more hospitalizations compared to those without such risk, with this difference being more pronounced in women than in men. After 1 year, women with psychosocial risk had on average 2.2 hospitalizations compared to 1.8 for women without risk (

p<.001). Men with psychosocial risk had 1.8 hospitalizations compared to 1.7 for men without risk (

p<.001). After 2 years, women with psychosocial risk had 3.4 hospitalizations compared to 2.8 women without risk (

p<.001). Men with psychosocial risk had 2.9 hospitalizations compared to 2.5 for men without risk (

p<.001).

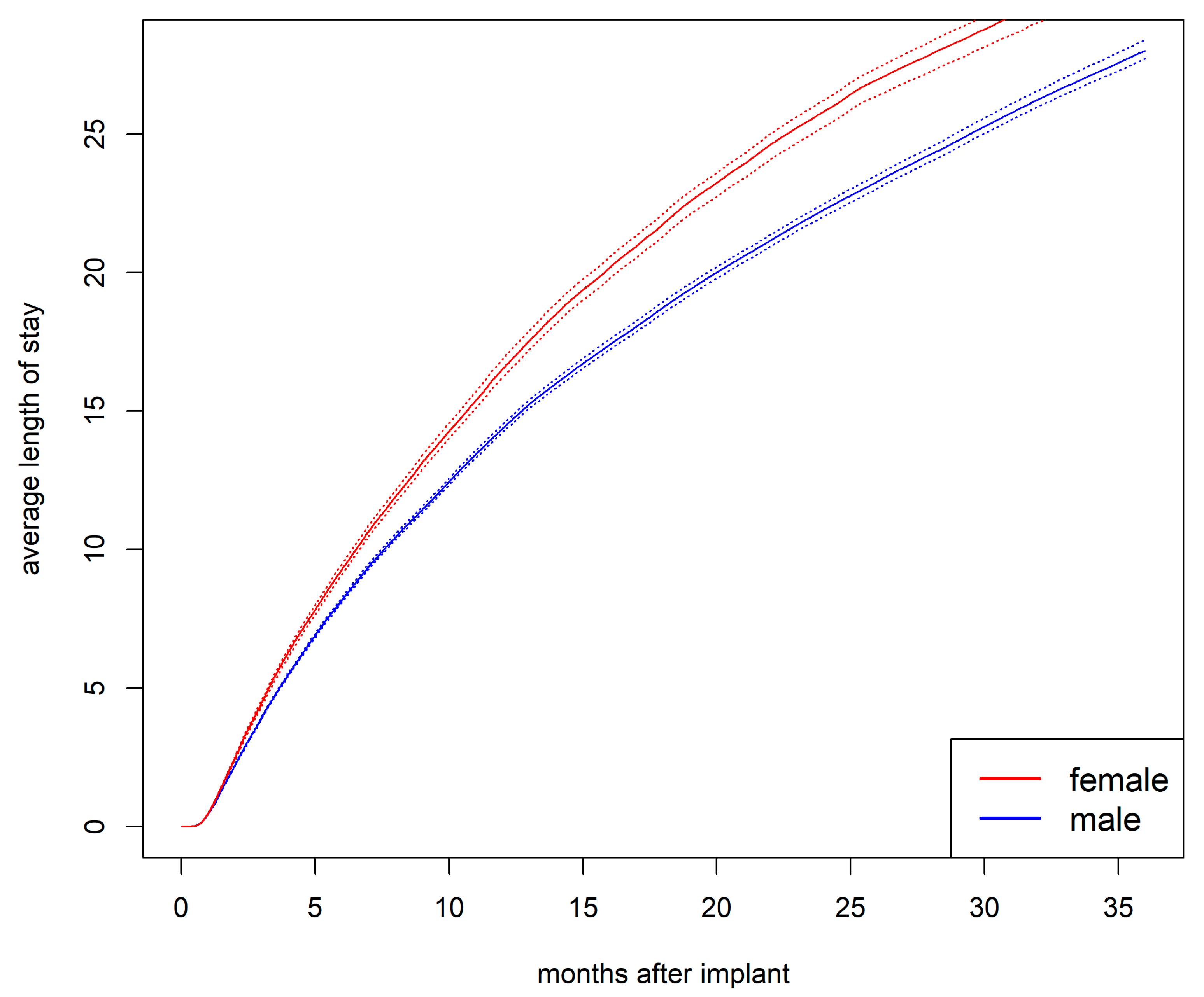

Cumulative Average Length of Stay in Hospital

The cumulative average length of hospital stay was longer for women than for men (

Figure 5). After one year, the average length of stay was 16.5 days for women compared to 14.4 days for men (

p<.001). After two years, it was 25.8 days for women compared to 22.3 days for men (

p<.001).

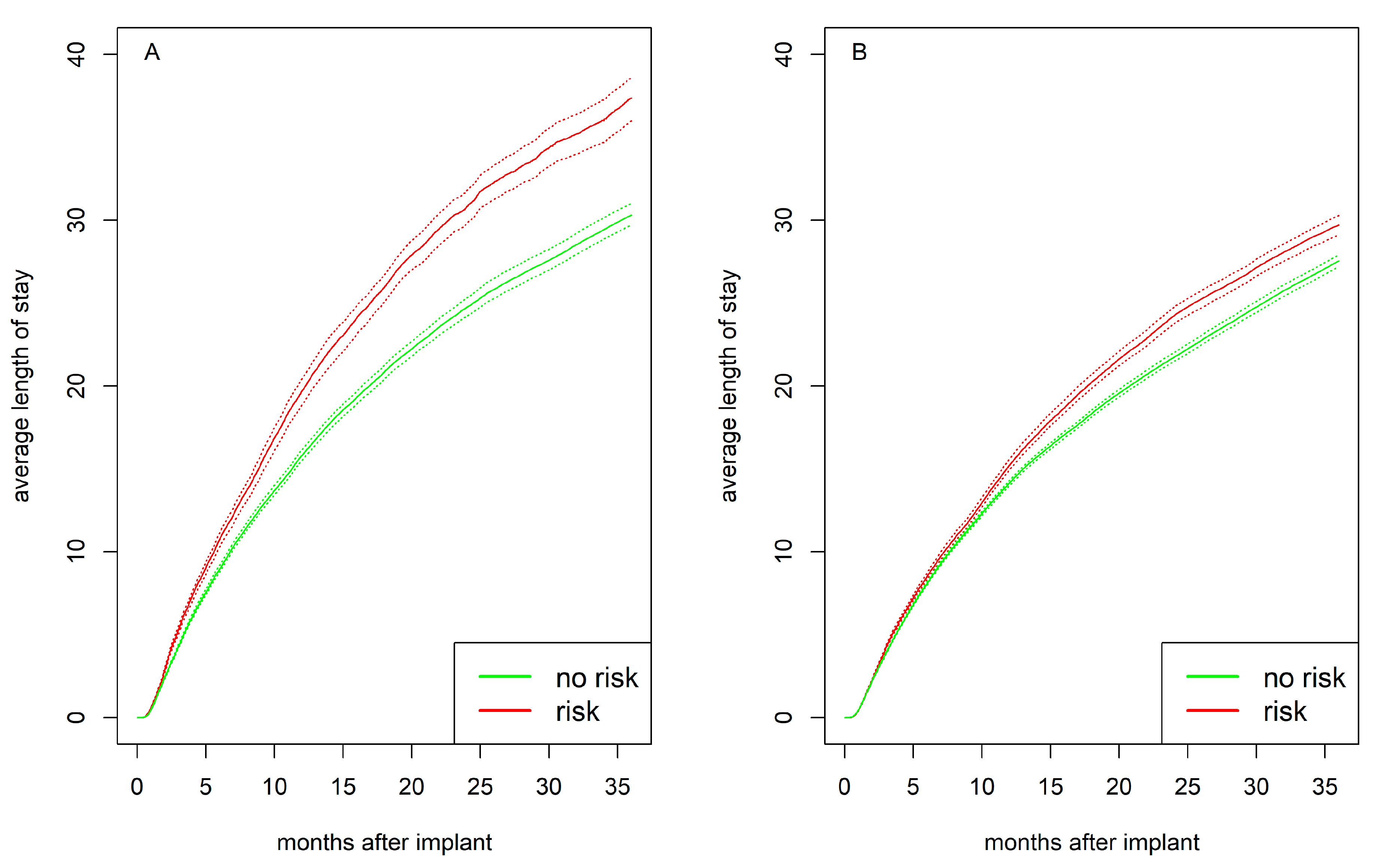

Psychosocial risk preimplant was associated with a longer average hospital stay, with the difference being more pronounced in women (

Figure 6). After one year, women with psychosocial risk had an average hospital stay of 19.7 days compared to 15.8 days for women without risk (

p<.001). Men with psychosocial risk stayed in the hospital for 15.2 days compared to 14.2 days in men without risk (

p<.001). After two years, women with psychosocial risk had an average hospital stay of 30.8 days compared to 24.8 days for women without risk (

p<.001). Men with psychosocial risk have 24.3 days compared to 21.7 days for men without risk (

p<.001).

Discussion

In multi-state recurrent event analysis with data from over 20,000 patients, women with CF-LVADs experienced higher rates of recurrent hospitalizations compared to men, particularly in the presence of psychosocial risk. This pattern remained significant even after adjusting for clinical, demographic, and behavioral variables. This extends our previous finding that psychosocial risk at time of LVAD implantation was associated with a 15% increased rate of first hospitalization among women, compared to a 3% increased rate in men [

7]. Importantly, the present findings show that the influence of preimplant psychosocial risk in women appears to persist beyond the first hospitalization, with the interaction between psychosocial risk and female sex increasing the risk of recurrent hospitalizations by 11%. The application of a multi-state model over a 36-month observation period addresses methodological challenges in analyzing sex differences in recurrent hospitalization [

16,

17,

18,

19] and thereby contributes to a more detailed clinical picture of outcomes [

23,

24].

While previous studies reported an average of two hospitalizations per year per patient [

4,

13], our analysis provides a more nuanced perspective by incorporating longer follow-up and subgroup analyses. After one year, women with psychosocial risk had a mean of 2.19 hospitalizations, compared to 1.78 for those without risk. Men with psychosocial risk averaged 1.84 hospitalizations, compared to 1.65 for their counterparts without risk. After two years, women with psychosocial risk experienced nearly one more hospitalization on average than men without psychosocial risk. These findings highlight that the long-term hospitalization burden is highest among women with psychosocial risk.

In women, psychosocial risk preimplant was not only associated with an increased rate of rehospitalizations, but also with longer hospital stays compared to both women without such risks and men, regardless of their psychosocial risk status. After one year, women with psychosocial risk spend an average of 20 days in the hospital, compared to 16 days for women without psychosocial risk. In men, psychosocial risk made only a difference of 1 day (15 days vs. 14 days). Psychosocial factors appear to have particular strong impact on women’s hospital stay duration.

Overall, psychosocial risk factors preimplant were associated with increased rates for rehospitalizations and accordingly, with a higher mean number of hospitalizations, particularly in women. In addition, women with psychosocial risk had longer hospital stays. Thus, psychosocial risk appears to contribute directly to their greater burden and increased healthcare costs [

14,

15]. Yet it is unclear whether patients with psychosocial issues receive psychological help during their hospitalization.

In cardiovascular disease outcomes, distinct and occasionally divergent associations have been observed for gender and sex [

30]. In this LVAD population, the average age of women is 54 years. The protective effects of female sex hormones may be diminished at this age, which allows to draw conclusions with regard to gender-related risk factors. Factors, such as perceived social support and gender-specific family roles, not included in the INTERMACS, likely influence women's healthcare experiences and health behaviors. For example, cardiologists have noted that male patients at heart transplant centers are typically accompanied by their wives, whereas female patients are seldom accompanied by their husbands [

31]. This observation reflects traditional gender roles, where women often bear caregiving responsibilities, leading to conflicting demands on their own healthcare—such as managing time-consuming medical consultations and transportation [

32]. This may contribute to worsening health conditions and increased rates or prolonged durations of rehospitalizations. Future research to explore factors contributing to the association between psychosocial risk and disparities in LVAD outcomes for women and men is clearly warranted and needs to consider both biological factors and gender-related factors [

30,

32].

Independent of gender and sex, this research also suggests that behavioral risk factors such as obesity and smoking play a role for clinical outcomes after LVAD implantation [

7,

34,

35]. For example, current smoking was associated with a 10% increase in rehospitalization rates. Additionally, lower education levels and not working for income were linked to higher rehospitalization rates. These socioeconomic risk factors can limit healthcare access and delay the seeking of medical attention [

36], thereby exacerbating health issues that may lead to hospitalization. Particularly, the interplay of psychosocial, behavioral, and socioeconomic risk factors presents significant challenges for LVAD patients, highlighting the need for comprehensive support and intervention strategies.

It is intriguing that despite sex differences in rehospitalizations, this multi-state analysis replicated comparable survival rates for women and men on LVAD [

3,

5,

9]. Additionally, it supports earlier findings suggesting that women may be more likely to experience cardiac recovery [

37]. To further improve outcomes for women and reduce rehospitalizations, close monitoring of adverse events and complications is essential. Timely detection of psychological comorbidities, such as anxiety and depression, are crucial, and referring patients to psychological care promptly ensures they receive appropriate support [

38,

39].

This is particularly important since previous research has shown that women with LVAD are more likely to have depression and other major psychiatric diagnoses, while men are more likely to have substance use issues [

7]. This suggests the need for a gender-sensitive approach to address these psychosocial issues in targeted prevention and intervention strategies for patients with LVAD. Psychosocial interventions have already been shown to improve quality of life, decrease symptoms of depression and anxiety in patients with heart failure [

40,

41]. When tailored to individual needs and gender-specific factors, these interventions not only improve psychological well-being but may also lead to better clinical outcomes [

42].

Limitations

The psychosocial variables provided in INTERMACS’

concerns and contraindications for transplant may vary in their assessment methods, ranging from unstandardized clinical judgments to validated questionnaires, depending on the practices of participating centers. The implementation of standardized and psychometrically sound assessment tools that can reliably describe changes in psychosocial characteristics into the database is warranted. This would allow to improve the accuracy of models that evaluate the impact of psychosocial risk on LVAD outcomes. This would also enable the evaluation of changes in psychosocial risk following rehospitalization and could guide improved patient care through early detection. Nevertheless, INTERMACS’ variables cover five key psychosocial domains - social support, cognition, substance use, psychopathology, and noncompliance [

21,

22] - allowing for an assessment of patients’ overall psychosocial risk profile.

This study examined the relationship between sex, psychosocial risk, and recurrent hospitalizations for all causes. A more granular understanding of the specific reasons for rehospitalization could provide valuable insights into the underlying causes and help refine targeted interventions. Unfortunately, the predominant reason for rehospitalization in both women (19.0%) and men (17.0%) was categorized as 'Other' in the INTERMACS registry (

Table S1), which limits the ability to further differentiate and explore the specific causes of these readmissions. Fortunately, newer devices, such as the HeartMate III—which is not included in this INTERMACS dataset—offer better fit for the female body and further reduce rehospitalizations among women [[

3,

4].] It would be valuable to explore the role of psychosocial risk factors on outcomes in women with this generation of devices.

Conclusion

During the course after CF-LVAD implantation women experience higher rates of recurrent hospitalizations compared to men, particularly in the presence of psychosocial risk, even after adjusting for clinical, demographic, and behavioral variables. Women with psychosocial risk also experience a higher average number of hospitalizations and longer hospital stays compared to women without such risks and men. These findings emphasize the need for comprehensive psychosocial assessments and the development of targeted interventions to improve outcomes post LVAD.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org, Table S1. Reasons for rehospitalization in women and men with implanted left ventricular assist devices. Figure S1. State occupation probabilities for being hospitalized stratified by sex. Figure S2. State occupation probabilities for being in any absorbing state (i.e., death, heart transplantation, device replacement due to complications, device explantation due to recovery) stratified by sex. In an absorbing state, patients are no longer at risk for subsequent events, such as rehospitalization.

Author Contributions

HS and GW were responsible for conception and design of the study questions. LM, HS, and GW were responsible for analyses, interpretation, and drafting the manuscript. SS and JB were responsible for providing and overseeing the methodological approach and contributed to analyses and writing of the paper.

Funding

This work was supported by grants from the German Research Foundation (HS, GW; SP945/2-1 and SS; BE4500/4-1), the Alexander von Humboldt Foundation (GW, HS, USA /1071425), and Trier University.

Financial conflict of interest statement

None of the authors has a financial relationship with a commercial entity that has an interest in the subject of the presented manuscript or other conflicts of interest to disclose.

Institutional Review Board Statement

This study received approval from the Institutional Review Board at Trier University (amendment 2024/04/26 to EK no. 66/2018).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all participants by the participating centers.

Data Availability Statement

The INTERMACS data were provided by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute Biologic Specimen and Data Repository Information Coordinating Center. Anonymized data and materials have been made publicly available at the Biologic Specimen and Data Repository Information Coordinating Center of the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute and can be accessed at

https://biolincc.nhlbi.nih.gov/studies/intermacs/.

Acknowledgments

This manuscript was prepared using INTERMACS Research Materials obtained from the NHLBI Biologic Specimen and Data Repository Information Coordinating Center and does not necessarily reflect the opinions or views of INTERMACS or the NHLBI. We thank all clinicians and investigators who contributed data to the INTERMACS database.

Conflicts of Interest

None of the authors has a financial relationship with a commercial entity that has an interest in the subject of the presented manuscript or other conflicts of interest to disclose.

Abbreviations

| ACE |

Angiotensin-converting-enzyme inhibitor |

| ARB |

Angiotensin II receptor blocker |

| BMI |

Body mass index |

| BUN |

Blood urea nitrogen |

| CF-LVAD |

Continuous-flow left ventricular assist device |

| HFrEF |

Heart failure with reduced ejection fraction |

| ICD |

Implantable cardioverter-defibrillator |

| INTERMACS |

Interagency Registry for Mechanically Assisted Circulatory Support |

| LVAD |

Left ventricular assist device |

| LVEDD |

Left ventricular end-diastolic diameter |

References

- Desai RJ, Mahesri M, Chin K, Levin R, Lahoz R, Studer R, et al. Epidemiologic characterization of heart failure with reduced or preserved ejection fraction populations identified using medicare claims. The American Journal of Medicine 2021, 134, e241–e51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khazanie, P. REVIVAL of the sex disparities debate: are women denied, never referred, or ineligible for heart replacement therapies? JACC: Heart Failure 2019, 7, 612–4. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Joshi AA, Lerman JB, Sajja AP, Dahiya G, Gokhale AV, Dey AK, et al. Sex-based differences in left ventricular assist device utilization: insights from the Nationwide Inpatient Sample 2004 to 2016. Circ Heart Fail 2019, 12, e006082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Teuteberg JJ, Cleveland JC, Jr. , Cowger J, Higgins RS, Goldstein DJ, Keebler M, et al. The Society of Thoracic Surgeons Intermacs 2019 annual report: the changing landscape of devices and indications. Ann Thorac Surg 2020, 109, 649–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Radhoe SP, Jakus N, Veenis JF, Timmermans P, Pouleur AC, Rubís P, et al. Sex-related differences in left ventricular assist device utilization and outcomes: results from the PCHF-VAD registry. ESC Heart Failure 2023, 10, 1054–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gruen J, Caraballo C, Miller PE, McCullough M, Mezzacappa C, Ravindra N, et al. Sex differences in patients receiving left ventricular assist devices for end-stage heart failure. JACC: Heart Failure 2020, 8, 770–9. [Google Scholar]

- Maukel L-M, Weidner G, Beyersmann J, Spaderna H. Adverse events after left ventricular assist device implantation linked to psychosocial risk in women and men. J Heart Lung Transplant 2023, 42, 1557–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magnussen C, Bernhardt AM, Ojeda FM, Wagner FM, Gummert J, de By TM, et al. Gender differences and outcomes in left ventricular assist device support: The European Registry for Patients with Mechanical Circulatory Support. J Heart Lung Transplant 2018, 37, 61–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maukel L-M, Weidner G, Beyersmann J, Spaderna H. Sex differences in recovery and device replacement after left ventricular assist device implantation as destination therapy. J Am Heart Assoc 2022, 11, e023294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeFilippis EM, Breathett K, Donald EM, Nakagawa S, Takeda K, Takayama H, et al. Psychosocial risk and its association with outcomes in continuous-flow left ventricular assist device patients. Circ Heart Fail 2020, 13, e006910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dew MA, Hollenberger JC, Obregon LL, Hickey GW, Sciortino CM, Lockard KL, et al. The preimplantation psychosocial evaluation and prediction of clinical outcomes during mechanical circulatory support: what information is most prognostic? Transplantation 2021, 105, 608–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang J, Okoh AK, Chen Y, Steinberg RS, Gangavelli A, Patel KJ, et al. Association of psychosocial risk factors with quality of life and readmissions 1 year after LVAD implantation. J Card Fail. 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Chew DS, Manns B, Miller RJH, Sharma N, Exner DV. Economic evaluation of left ventricular assist devices for patients with end stage heart failure who are ineligible for cardiac transplantation. Can J Cardiol 2017, 33, 1283–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah P, Yuzefpolskaya M, Hickey GW, Breathett K, Wever-Pinzon O, Ton VK, et al. Twelfth Interagency Registry for Mechanically Assisted Circulatory Support report: readmissions after left ventricular assist device. Ann Thorac Surg 2022, 113, 722–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baras Shreibati J, Goldhaber-Fiebert JD, Banerjee D, Owens DK, Hlatky MA. Cost-effectiveness of left ventricular assist devices in ambulatory patients with advanced heart failure. JACC Heart Fail 2017, 5, 110–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Agrawal S, Garg L, Shah M, Agarwal M, Patel B, Singh A, et al. Thirty-day readmissions after left ventricular assist device implantation in the United States: insights from the Nationwide Readmissions Database. Circ Heart Fail 2018, 11, e004628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Imburgio S, Dandu S, Pannu V, Udongwo N, Johal A, Hossain M, et al. Sex-based differences in left ventricular assist device clinical outcomes. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv 2024, 103, 376–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noly PE, Wu X, Hou H, Grady KL, Stewart JW, 2nd, Hawkins RB, et al. Association of days alive and out of the hospital after ventricular assist device implantation with adverse events and quality of life. JAMA Surg 2023, 158, e228127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed A, Adegbala O, Akintoye E, Inampudi C, Ajam M, Yassin AS, et al. Gender differences in outcomes after implantation of left ventricular assist devices. Ann Thorac Surg 2020, 109, 780–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirklin JK, Pagani FD, Kormos RL, Stevenson LW, Blume ED, Myers SL, et al. Eighth annual INTERMACS report: special focus on framing the impact of adverse events. J Heart Lung Transplant 2017, 36, 1080–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bui QM, Allen LA, LeMond L, Brambatti M, Adler E. Psychosocial evaluation of candidates for heart transplant and ventricular assist devices: beyond the current consensus. Circ Heart Fail 2019, 12, e006058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dew MA, DiMartini AF, Dobbels F, Grady KL, Jowsey-Gregoire SG, Kaan A, et al. Consensus Document: The 2018 ISHLT/APM/AST/ICCAC/STSW recommendations for the psychosocial evaluation of adult cardiothoracic transplant candidates and candidates for long-term mechanical circulatory support. J Heart Lung Transplant 2018, 37, 803–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ozga A-K, Kieser M, Rauch G. A systematic comparison of recurrent event models for application to composite endpoints. BMC Medical Research Methodology 2018, 18, 2. [Google Scholar]

- Furberg JK, Rasmussen S, Andersen PK, Ravn H. Methodological challenges in the analysis of recurrent events for randomised controlled trials with application to cardiovascular events in LEADER. Pharm Stat 2022, 21, 241–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Buuren S, Groothuis-Oudshoorn K. Mice: multivariate imputation by chained equations in R. J Stat Softw 2011, 45, 1–68. [Google Scholar]

- Allignol A, Beyersmann J, Schmoor C. Statistical issues in the analysis of adverse events in time-to-event data. Pharm Stat 2016, 15, 297–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nießl A, Allignol A, Beyersmann J, Mueller C. Statistical inference for state occupation and transition probabilities in non-Markov multi-state models subject to both random left-truncation and right-censoring. Econometrics and Statistics 2023, 25, 110–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erdmann A, Beyersmann J, Bluhmki E. Comparison of nonparametric estimators of the expected number of recurrent events. Pharm Stat 2024, 23, 339–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- R Development Core Team. R: a Language and environment for statistical computing. Vienna, Austria: R Foundation for Statistical Computing; 2018.

- Regitz-Zagrosek V, Gebhard C. Gender medicine: effects of sex and gender on cardiovascular disease manifestation and outcomes. Nat Rev Cardiol 2023, 20, 236–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Regitz-Zagrosek V, Petrov G, Lehmkuhl E, Smits JM, Babitsch B, Brunhuber C, et al. Heart transplantation in women with dilated cardiomyopathy. Transplantation 2010, 89, 236–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mwansa H, Lewsey S, Mazimba S, Breathett K. Racial/ethnic and gender disparities in heart failure with reduced ejection fraction. Curr Heart Fail Rep 2021, 18, 41–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Breathett K, Yee E, Pool N, Hebdon M, Crist JD, Yee RH, et al. Association of gender and race with allocation of advanced heart failure therapies. JAMA Network Open 2020, 3, e2011044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forest SJ, Xie R, Kirklin JK, Cowger J, Xia Y, Dipchand AI, et al. Impact of body mass index on adverse events after implantation of left ventricular assist devices: an IMACS registry analysis. J Heart Lung Transplant 2018, 37, 1207–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Youmans QR, Zhou A, Harap R, Eskender MH, Anderson AS, Ezema AU, et al. Association of cigarette smoking and adverse events in left ventricular assist device patients. The International Journal of Artificial Organs 2021, 44, 181–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Havranek EP, Mujahid MS, Barr DA, Blair IV, Cohen MS, Cruz-Flores S, et al. Social determinants of risk and outcomes for cardiovascular disease: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation 2015, 132, 873–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wever-Pinzon O, Drakos SG, McKellar SH, Horne BD, Caine WT, Kfoury AG, et al. Cardiac recovery during long-term left ventricular assist device support. J Am Coll Cardiol 2016, 68, 1540–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McDonagh TA, Metra M, Adamo M, Gardner RS, Baumbach A, Böhm M, et al. 2021 ESC Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure. Eur Heart J 2021, 42, 3599–726.

- Heidenreich PA, Bozkurt B, Aguilar D, Allen LA, Byun JJ, Colvin MM, et al. 2022 ACC/AHA/HFSA guideline for the management of heart failure. Circulation 2022, 145, e876–e94. [Google Scholar]

- Nahlén Bose, C. A meta-review of systematic reviews and meta-analyses on outcomes of psychosocial interventions in heart failure. Frontiers in Psychiatry. 2023, 14, 1095665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chernoff RA, Messineo G, Kim S, Pizano D, Korouri S, Danovitch I, et al. Psychosocial interventions for patients with heart failure and their impact on depression, anxiety, quality of life, morbidity, and mortality: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Psychosom Med 2022, 84, 560–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orth-Gomer K, Schneiderman N, Wang HX, Walldin C, Blom M, Jernberg T. Stress reduction prolongs life in women with coronary disease: The stockholm women's intervention trial for coronary disease (SWITCHD). Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes 2009, 2, 25–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vidula H, Takeda K, Estep JD, Silvestry SC, Milano C, Cleveland JC, Jr. , et al. Hospitalization patterns and impact of a magnetically-levitated left ventricular assist device in the MOMENTUM 3 Trial. JACC Heart Fail 2022, 10, 470–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shih H, Mondellini GM, Kurlansky PA, Sun J, Ning Y, Feldman VR, et al. Unplanned hospital readmissions following HeartMate 3 implantation: Readmission rates, causes, and impact on survival. Artif Organs. 2024.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).