1. Introduction

Generative Adversarial Networks (GANs) have become a cornerstone in the field of deep learning, primarily due to their remarkable capacity to capture and replicate intricate, high-dimensional data distributions, thereby enabling the generation of highly realistic synthetic samples. GANs operate based on an adversarial training paradigm that consists of two neural networks: a generator, responsible for producing realistic synthetic data, and a discriminator, tasked with distinguishing synthetic samples from real data. This dynamic interplay between the generator and discriminator facilitates an iterative refinement process, ultimately enhancing the realism and quality of the generated outputs [

1].

Since their introduction, GANs have demonstrated outstanding efficacy across a diverse set of applications, including photorealistic image synthesis, high-quality text generation, speech and audio modeling, as well as video sequence prediction. Their intrinsic versatility has significantly advanced multiple research and industry domains, notably computer vision tasks such as image-to-image translation, super-resolution, and object detection; natural language processing tasks involving text augmentation and dialogue generation [

2]; as well as scientific simulations, where they assist in modeling complex physical phenomena by generating realistic synthetic scenarios. Moreover, GANs have found considerable utility in wireless communications, where they are employed for data augmentation, anomaly detection, and enhancing communication system robustness.

Current research continues to extend GAN frameworks, addressing critical limitations such as mode collapse, instability during training, and evaluation metrics for generated data quality. Furthermore, advanced variants like conditional GANs (cGANs), Wasserstein GANs (WGANs), and Progressive GANs (ProGANs) have been introduced to enhance the stability, diversity, and scalability of these models. These innovations continue to propel GANs as vital tools within the broader landscape of generative artificial intelligence, enabling novel applications and breakthroughs across numerous scientific and technological fields.

Over the past decade, numerous variants of GANs have been introduced to address specific challenges or extend their capabilities. Conditional GANs enable targeted generation based on input conditions, while CycleGANs facilitate unpaired image-to-image translation. Progressive GANs and StyleGANs have achieved exceptional results in high-resolution image generation. Furthermore, GANs have been combined with emerging technologies like Transformers, Diffusion Models, and Physics-Informed Neural Networks to further enhance their functionality.

Despite these advancements, challenges persist. GANs are notoriously difficult to train due to instability, mode collapse, and the lack of standardized evaluation metrics. Extensive research has focused on addressing these issues, leading to improved training techniques and hybrid approaches that combine GANs with other deep learning models.

This survey provides a detailed examination of GANs, covering their architecture, theoretical foundations, applications, and limitations. It also explores the evolution of GANs, significant variants, evaluation methods, and emerging trends that combine GANs with other frameworks. By offering insights into both the successes and challenges of GANs, this survey aims to guide future research and development in this rapidly advancing field.

2. Overview of Generative Adversarial Networks

A

Generative Adversarial Network (GAN) is a machine learning framework consisting of two neural networks: the generator (

G) and the discriminator (

D). The generator maps input noise to structured outputs with the goal of producing data that closely resembles real samples. Meanwhile, the discriminator functions as a binary classifier, attempting to distinguish between genuine data from the training set and synthetic data generated by

G. Through this adversarial training process, both networks iteratively improve—

G becomes better at generating realistic data, while

D enhances its ability to detect forgeries. It receives real input from both real data samples

as well as the data generated from the generator and sets a probability for each sample to identify if the data is real. Chandra et al [

3] defines the process as adversarial training as both networks keep improving each other by generator producing real-like images continuously, as discriminator can well distinguish real and fake images, whereas discriminator learns to distinguish between fake and real image.

2.1. Architecture of GANs

The mechanism within the GAN architecture is a competition between the Generator and the Discriminator that are constantly in effort to improving each other. A noise vector z, introduced from a predefined noise distribution (e.g., Gaussian or uniform), is mapped to a synthetic data sample. This mapping, represented by , involves a sequence of nonlinear transformations parameterized by . The Generator creates data samples that mimic the characteristics of the true data distribution .

The Discriminator, represented as , is a binary classifier parameterized by . It outputs a higher probability that a given input x is real. For real data , the Discriminator aims to maximize its output (), whereas for fake data , it seeks to minimize its output (). This classification capability eventually improves the Discriminator that can well differentiate real and synthetic data.

The adversarial relationship between

G and

D is formalized as a minmax game, defined by following function:

In this game, the Discriminator keeps maximizing its ability to classify real and fake samples, while the Generator simultaneously minimizes the Discriminator’s ability to do so.

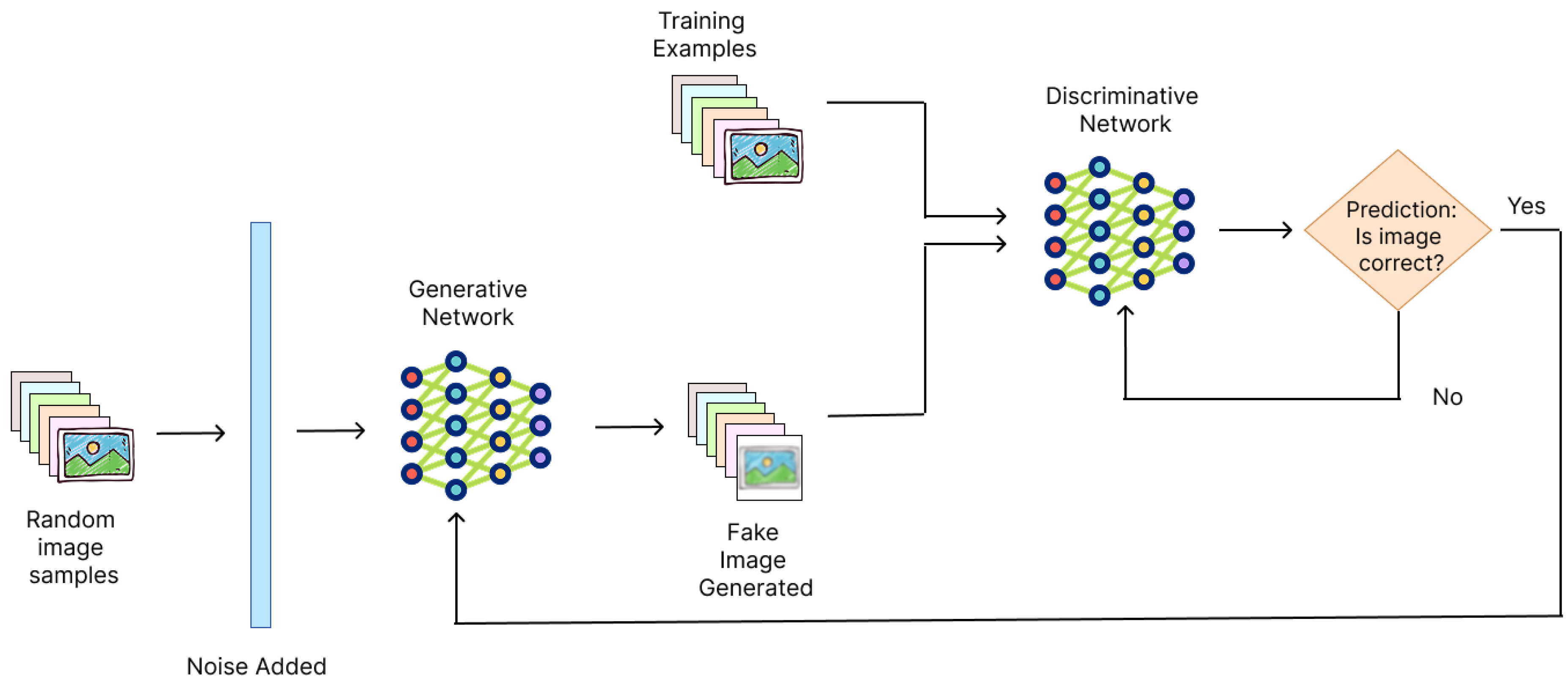

Figure 1 illustrates the GAN architecture, depicting the flow of data between the Generator, Discriminator, and the input sources.

2.2. Training of GANs

Training a GAN involves alternating optimization of the Generator and the Discriminator in a two-step process, repeated over many iterations. The Discriminator is trained first, followed by the Generator, ensuring that the feedback provided by the Discriminator effectively guides the Generator’s improvement.

The Discriminator’s training starts by presenting it with a batch of real samples

and a batch of fake samples

, where

. The Discriminator’s objective is to maximize its output for real samples (

) while minimizing its output for fake samples (

). This optimization updates the Discriminator’s parameters

to maximize the following loss function:

Once the Discriminator is updated, the Generator is trained to improve its ability to fool the Discriminator. The Generator receives the gradients from the Discriminator’s output, propagates them back through its network, and updates its parameters

. The Generator’s objective is to minimize the possibility of the Discriminator to correctly identify the fake samples, effectively maximizing

. The Generator’s loss is defined as:

Over successive iterations, the Generator learns to produce more realistic samples, while the Discriminator refines its classification boundary. The competitiveness or the adversarial behavior of both the networks within the training process ensures that either of them improves simultaneously, with the Generator approximating the true data distribution as closely as possible. However, challenges such as instability, mode collapse (where the Generator produces less diverse examples), and sensitivity to hyperparameters require careful tuning and advanced techniques like improved loss functions or regularization methods to ensure convergence.

The interplay between

G and

D, illustrated in

Figure 1, emphasizes the iterative and adversarial nature of GAN training, which enables these networks to excel in generating high-quality synthetic data.

3. Additional GAN Variants

While the original GAN framework revolutionized generative modeling, subsequent research has proposed several variants to address its limitations, improve training stability, and adapt it for specific tasks. This section delves into key variants, including Wasserstein GANs (WGANs) and Deep Convolutional GANs (DCGANs), as well as a brief overview of other notable GAN variants.

3.1. Deep Convolutional Generative Adversarial Networks (DCGANs)

Deep Convolutional Generative Adversarial Networks (DCGANs) [

5] have become a foundational model in the field of generative adversarial networks (GANs), significantly improving the stability and quality of generated images. Introduced by Radford et al. [

5], DCGANs replace the fully connected layers of traditional GANs with convolutional layers, allowing them to capture spatial hierarchies in image data. This architectural shift enables better performance, especially in tasks such as image generation, super-resolution, and style transfer.

3.1.1. Concept, Architecture, and Training

Deep Convolutional Generative Adversarial Networks (DCGANs) are used to produce diverse data with more features, compensating the need to overcome data insufficiency in the training phase. It overcomes the challenge of collecting data samples by incorporating data augmentation. Divya et al [

6] used DCGAN on brain tumor Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI) to minimize the challenge of data inadequacy and maintain optimum data quality and variety. DCGAN has also repairs data by adding data to missing values, thus producing high quality data to improve the model training.

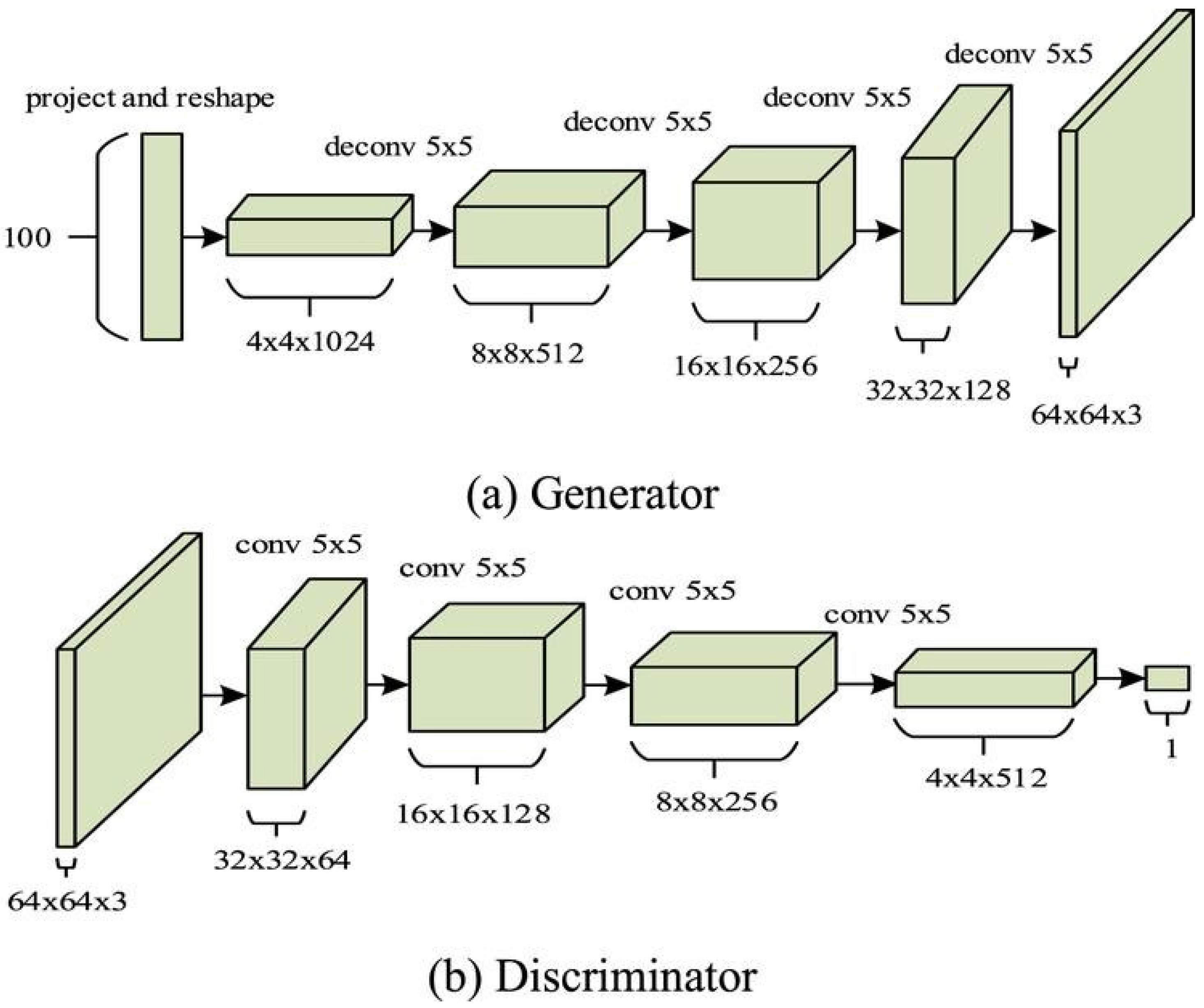

The core design of Deep Convolutional Generative Adversarial Networks (DCGANs) involves two primary components: the generator and the discriminator. Both networks utilize convolutional architectures tailored for processing image data. The generator receives a random noise vector z and transforms it into an image through a sequence of transposed convolutional layers (also known as deconvolutional layers), enabling the model to upsample and reconstruct spatial features. Conversely, the discriminator employs a series of standard convolutional layers to extract hierarchical representations from input images, ultimately aiming to classify them as real or generated.

The generator’s convolutional transpose layers upscale the latent vector into an image while maintaining spatial dependencies. The discriminator uses convolutional layers with strided convolutions to downsample the input, allowing it to focus on important features and progressively make decisions on the authenticity of the image. The use of batch normalization in both networks stabilizes training by normalizing the activations and mitigating issues like mode collapse, which is common in traditional GANs.

Several key innovations set DCGANs apart from traditional GANs and other generative models:

Strided Convolutions: In the discriminator network, max-pooling layers are replaced by strided convolutions, which allow the network to downsample without losing important spatial details. This is essential for the discriminator to accurately classify real and generated images.

Batch Normalization: Applied in both the generator and discriminator, batch normalization stabilizes the learning process by normalizing the activations of each layer. This technique helps prevent mode collapse, where the generator produces limited varieties of images.

Leaky ReLU Activation: The discriminator uses Leaky ReLU instead of the traditional ReLU activation to address the problem of dead neurons, ensuring that the network can still learn from negative values.

The training of a DCGAN adheres to the conventional adversarial paradigm, wherein the generator and discriminator are optimized in a minimax setting. The generator aims to synthesize images that closely resemble real samples, making it difficult for the discriminator to distinguish between the two. Simultaneously, the discriminator is trained to accurately differentiate between genuine and generated images. Through this iterative competition, the generator progressively improves its capacity to produce realistic images, while the discriminator becomes more effective at detecting synthetic inputs. The objective function used for training is:

where

G is the generator,

D is the discriminator, and

is the real data distribution.

A diagram illustrating the architecture of DCGAN is shown in

Figure 2.

Overall, DCGANs represent a significant advancement in GAN architectures, providing a more stable and effective framework for image generation tasks. Integrating convolutional layers into both the generator and discriminator has demonstrated significant effectiveness in learning and capturing the intricate spatial dependencies present in visual data.

3.2. Wasserstein GANs (WGANs)

The GAN generator and discriminator are trained simultaneously in a minimax game. However, despite their success, GANs often suffer from training instability, mode collapse, and vanishing gradients, which can prevent the model from converging effectively.

To mitigate these issues, Wasserstein GANs (WGANs) were proposed by Arjovsky et al. in 2017 [

7]. WGANs replace the traditional Jensen-Shannon divergence used in GANs with the Wasserstein distance, also known as the Earth Mover’s Distance. This modification leads to more stable training and improved convergence.

3.2.1. Challenges in Traditional GANs

Conventional GANs employ a loss function derived from the Jensen-Shannon (JS) divergence to quantify the dissimilarity between the real and generated data distributions. In this framework, the generator is optimized to minimize the JS divergence, while the discriminator is trained to maximize it. Despite its theoretical foundation, this approach often results in training instabilities and convergence issues [

8].

3.2.2. Mode Collapse

Mode collapse is a common issue in GAN training, where the generator maps different input noise vectors to similar or identical outputs, thereby failing to capture the full diversity of the target data distribution. This means that even though the discriminator might think the generated data is real, it fails to capture the diversity present in the true data. Mode collapse is particularly problematic in high-dimensional data such as images, where a wide range of plausible outputs exist for any given input.

3.2.3. Training Instability

GANs are notoriously unstable during training. The reason for this instability lies in the adversarial nature of the generator and discriminator networks. Both models are optimized simultaneously, but the generator’s updates depend on the discriminator’s feedback. If the discriminator becomes too powerful or too weak, the generator may either fail to learn or learn in an unstable way. The hyperparameters that control the training process, such as learning rates and the architecture of the networks, must be carefully tuned to prevent these issues.

3.2.4. Vanishing Gradients

Vanishing gradients is another significant issue in traditional GANs. This happens when the discriminator becomes too confident in its classification, providing very small gradients for the generator. When the gradients are too small, the generator’s updates become insignificant, making it difficult for the model to improve. This phenomenon is exacerbated in the later stages of training when the discriminator becomes nearly perfect at distinguishing real from fake data.

3.2.5. Wasserstein GANs: The Solution

Wasserstein GANs were introduced to address these issues by replacing the traditional loss function with the Wasserstein distance. The Wasserstein distance is a continuous and differentiable measure of the difference between two distributions, which ensures that gradients are well-behaved during training.

3.2.6. The Concept of Wasserstein Distance

Wasserstein GANs (WGANs) mitigate several limitations of traditional GANs by replacing the Jensen-Shannon divergence with the Wasserstein distance, a more robust and meaningful measure of discrepancy between probability distributions. The Wasserstein distance, also known as the Earth Mover’s Distance, quantifies the minimum effort required to transform one probability distribution into another, offering improved gradient behavior and more stable training dynamics. Formally, it is defined as:

where

represents the set of joint distributions with marginals

and

. The continuous and smooth nature of the Wasserstein distance yields informative and well-behaved gradients during training, facilitating more effective optimization of both the generator and the discriminator.

3.2.7. WGAN Objective Function and 1-Lipschitz Constraint

The key difference between WGANs and traditional GANs lies in the objective function and the constraints on the discriminator. In a WGAN, the objective function is:

where

D is a 1-Lipschitz function, meaning that the discriminator’s output is constrained to change at most linearly with respect to its input. This constraint is enforced through weight clipping or gradient penalty, which stabilizes training by preventing the discriminator from becoming too powerful.

3.2.8. Convergence in WGAN

WGAN optimizes the Wasserstein distance, which provides continuity and a smoother gradient landscape, unlike the discontinuous JS divergence. This continuous objective helps prevent mode collapse by providing a meaningful gradient even when

is far from

[

9].

3.3. Other Variants of GANs

3.3.1. StyleGAN

StyleGAN is a type of GAN that allows for more control over the generated images. It uses a unique architecture where the generator is divided into several layers, each controlling different aspects of the image, such as shape, texture, or details. This gives you the ability to adjust the "style" of an image at different levels, making it ideal for tasks like generating realistic faces or artworks[

10].

3.3.2. CycleGAN

CycleGAN is used for tasks where you want to convert images from one style to another, without needing paired training data. For example, it can turn a photo into a painting or convert day-time photos to night-time. The key idea is that the model learns to map images from one domain to another and ensures that it can transform an image back to its original form, preserving its content[

11].

3.3.3. Conditional GAN (cGAN)

Conditional GANs extend the basic GAN by adding extra information, like labels or attributes, to guide the image generation process. For example, you could generate images of specific objects, such as a cat or a dog, by providing the label "cat" or "dog" as input. This allows the model to create images based on specific conditions[

12].

3.3.4. Pix2Pix

Pix2Pix is a model for transforming one type of image into another, using paired images for training. It can be used for tasks like turning sketches into photos, or black-and-white images into color ones. The model learns the mapping between the input and output images so it can generate realistic results[

13].

3.4. BigGAN

BigGAN is a scaled-up version of GAN that can generate high-quality images at large resolutions. By increasing the size of the network and training with larger batch sizes, BigGAN produces detailed and realistic images. It’s particularly good for generating images from large datasets, like the ImageNet dataset[

14].

4. Applications of GANs

Generative Adversarial Networks, including WGANs, have been applied to a variety of fields. Their ability to generate high-quality synthetic data has opened new possibilities in domains such as computer vision, healthcare, art, and data augmentation [

15,

16].

4.1. Image Generation

GANs, and particularly WGANs, have been highly successful in generating realistic images. By training on large datasets of real images, GANs can generate new images that resemble the original data. WGANs have shown particular promise in generating sharp and high-quality images due to their stable training process. For example, they have been used to create photorealistic images of faces, animals, and landscapes [

4].

4.2. Data Augmentation in Healthcare

In the healthcare sector, GANs have been employed to synthesize medical data, including diagnostic images and electronic health records. This capability is especially valuable in scenarios with limited access to real data, such as rare disease cases. Wasserstein GANs (WGANs), in particular, contribute to generating data that is both realistic and diverse, thereby enhancing the quality and robustness of downstream machine learning models trained on medical datasets.

4.3. Art and Creativity

In the world of art, GANs have been used to generate original paintings, music, and even poetry. Artists and musicians have experimented with GANs to create new works that combine human creativity with machine learning. WGANs, with their stable training dynamics, offer a robust framework for generating creative works, producing high-quality outputs that are more visually appealing and stylistically coherent.

4.4. Wireless Communications and Signal Processing

In wireless communications, GANs have been leveraged to synthesize realistic radio-frequency (RF) signals and wireless channel conditions, significantly aiding the development and testing of robust communication systems. GANs, particularly WGANs, have demonstrated success in channel estimation and anomaly detection, generating synthetic yet highly representative channel conditions to improve the resilience of 5G and 6G communication systems [

17,

18].

4.5. Autonomous Systems and Robotics

GANs have notably contributed to autonomous systems by synthesizing training data critical for computer vision tasks such as object detection and scene segmentation. Variants such as CycleGAN have facilitated the simulation-to-reality (Sim2Real) transfer, effectively reducing discrepancies between simulation-generated training data and real-world perception, significantly enhancing the robustness and performance of autonomous vehicles and robotics systems.

4.6. Scientific Simulations and Physics-Informed GANs

GANs have shown substantial promise in scientific simulations, especially when integrated with domain-specific knowledge through Physics-Informed GANs (PIGAN). These models enforce physical constraints within GAN frameworks, effectively simulating complex systems, such as fluid flows, structural mechanics, and climate dynamics. Moreover, GANs facilitate rapid molecular synthesis and drug discovery processes by efficiently exploring vast chemical spaces and optimizing compound properties, significantly accelerating research and development in computational chemistry.

4.7. Security and Privacy

GANs play an increasingly critical role in cybersecurity, used both offensively and defensively. Adversarial attacks employing GANs test the robustness of security systems, while GAN-driven defensive mechanisms generate synthetic training examples to enhance model resilience. Additionally, GANs provide privacy-preserving synthetic data generation capabilities, particularly important in fields with sensitive data such as finance, healthcare, and biometric authentication, enabling robust modeling without compromising data confidentiality.

4.8. Unsupervised Learning and Domain Adaptation

Wasserstein GANs (WGANs) have demonstrated significant potential in unsupervised learning settings. They are capable of generating high-quality data from unlabeled datasets, which can subsequently enhance the performance of downstream tasks such as classification and clustering. In addition, WGANs have been effectively applied in domain adaptation scenarios, enabling models trained on a source domain to generalize and perform reliably on data from a different, yet related, target domain.

5. Future Applications and Limitations

While GANs have seen success in diverse applications such as image synthesis, super-resolution, and style transfer, they still face challenges in terms of training stability, mode collapse, and sample quality [

19]. Future research may focus on integrating reinforcement learning, alternative distance metrics, and unsupervised feature disentanglement to further stabilize and enhance GAN performance.

6. Conclusion

This paper has reviewed the evolution of GAN architectures, with a particular focus on DCGAN and WGAN, both of which introduce key enhancements to the original GAN framework. These advancements have played a crucial role in establishing GANs as a cornerstone of generative modeling. However, despite these improvements, challenges persist, and ongoing research is dedicated to further enhancing the stability, efficiency, and output quality of GAN models.

Wasserstein GANs represent a significant leap forward from traditional GANs by addressing critical issues related to training stability and gradient flow. The adoption of the Wasserstein distance, coupled with the 1-Lipschitz constraint, has proven to be highly effective in generating high-quality data across a range of applications. As the field of GANs continues to develop, WGANs serve as a strong foundation for future breakthroughs in generative modeling.

References

- Goodfellow, I.J.; Pouget-Abadie, J.; Mirza, M.; Xu, B.; Warde-Farley, D.; Ozair, S.; Courville, A.; Bengio, Y. Generative adversarial networks. Advances in neural information processing systems 2014, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Debnath, T.; Siddiky, M.N.A.; Rahman, M.E.; Das, P.; Guha, A.K. A Comprehensive Survey of Prompt Engineering Techniques in Large Language Models. TechRxiv 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chandra, B. Building a Generative Adversarial Network for Image Synthesis. Indian Scientific Journal Of Research In Engineering And Management 2024, 08. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saha, P.K.; Nadeem, S.A.; Comellas, A.P. A Survey on Artificial Intelligence in Pulmonary Imaging. Pulmonary Imaging Journal 2023. Available online.

- Radford, A.; Metz, L.; Chintala, S. Unsupervised Representation Learning with Deep Convolutional Generative Adversarial Networks. arXiv preprint arXiv:1511.06434 2015.

- Divya, S. Medical MR Image Synthesis using DCGAN. International Conference on Electrical, Electronics, Information and Communication Technologies (ICEEICT) 2022. [CrossRef]

- Stéphanovitch, A.; Aamari, E.; Levrard, C. Wasserstein GANs are Minimax Optimal Distribution Estimators. arXiv preprint arXiv:2311.18613 2023.

- Petkov, H.; Hanley, C.; Dong, F. Causality Learning with Wasserstein Generative Adversarial Networks. International Journal of Artificial Intelligence & Applications 2022, 13, 1–13. [CrossRef]

- Arjovsky, M.; Chintala, S.; Bottou, L. Wasserstein GAN. arXiv preprint arXiv:1701.07875 2017.

- Karras, T.; Aila, T.; Laine, S.; Lehtinen, J. A Style-Based Generator Architecture for Generative Adversarial Networks. arxiv 2019, pp. 4401–4410.

- Zhu, J.Y.; Park, T.; Isola, P.; Efros, A.A. Unpaired Image-to-Image Translation Using Cycle-Consistent Adversarial Networks. arxiv 2017, pp. 2223–2232.

- Mirza, M.; Osindero, S. Conditional Generative Adversarial Nets. arXiv preprint arXiv:1411.1784 2014.

- Isola, P.; Zhu, J.Y.; Zhou, T.; Efros, A.A. Image-to-Image Translation with Conditional Adversarial Networks. arxiv 2017, pp. 1125–1134.

- Brock, A.; Donahue, J.; Simonyan, K. Large Scale GAN Training for High Fidelity Natural Image Synthesis. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the International Conference on Machine Learning (ICML), 2019, pp. 343–352.

- García-Esteban, J.J.; Cuevas, J.C.; Bravo-Abad, J. Generative adversarial networks for data-scarce spectral applications. arXiv preprint arXiv:2307.07454 2023.

- Siddiky, M.N.A.; Rahman, M.E.; Hossen, M.F.B.; Rahman, M.R.; Jaman, M.S. Optimizing AI Language Models: A Study of ChatGPT-4 vs. ChatGPT-4o. Preprints 2025. [CrossRef]

- Siddiky, M.N.A.; Rahman, M.E.; Uzzal, M.S.; Kabir, H.M.D. A Comprehensive Exploration of 6G Wireless Communication Technologies. Computers 2025, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siddiky, M.N.A.; Rahman, M.E.; Badhon, R.H.; Salman, M.M.; Sohag, M.S.H. The Information Bottleneck Method in Deep Learning: Principles, Applications, and Challenges. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Signal Processing, Information, Communication and Systems 2024. IEEE, 2024.

- Creswell, A.; White, T.; Dumoulin, V.; Arulkumaran, K.; Sengupta, B.; Bharath, A.A. Generative Adversarial Networks: An Overview. IEEE Signal Processing Magazine 2018, 35, 53–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).