Introduction

Insertion of a peripheral intravenous catheter is one of the most frequent procedures used in hospitals, with approximately 80% of patients requiring catheter insertion for intravenous treatment [

1]. Despite its many benefits, its use is not without potential complications such as phlebitis, infiltration, extravasation, occlusion, and clot dislodgment [

2]. Phlebitis, the most common complication associated with catheter insertion, is inflammation of a vein that causes redness, swelling, and pain when the patient receives intravenous treatment and can progress to advanced stages with additional symptoms such as extensive edema and palpation of the venous cord [

3]. In thrombophlebitis, the superficial or deep veins can be affected, especially those located in the limbs. The phlebitis stage indicates the severity of venous inflammation secondary to a catheter in patients requiring intravenous treatment [

4,

5]. The severity of phlebitis is frequently evaluated using scales such as the Visual Infusion Phlebitis (VIP) scale, which encompasses grades 1–5 [

6,

7].

The management of catheter phlebitis necessitates consideration of various risk factors identified in the literature, including the prolonged duration of peripheral venous catheter maintenance, infusions containing amiodarone or antibiotics, insertion site in the hand, presence of infectious disease, and the type and size of the catheter used [

8,

9,

10,

11,

12,

13]. Furthermore, the quality and dimensions of veins, local hygiene practices, and duration of clinical nursing experience are significant predictive factors [

14]. The antecubital fossa and forearm veins may be optimal sites for peripheral venous cannulation [

15].

The removal of the venous catheter is recommended based on the first signs of phlebitis, and specialized treatment should be promptly initiated [

16]. This treatment includes the application of local anti-inflammatory agents and heparinoid-containing gels in conjunction with elevation of the affected limb, application of an elastic bandage, and administration of cold therapy [

17]. If there are signs of local infection, in addition to antibiotic therapy, surgical treatment may be necessary for drainage of purulent secretions and removal of the affected vein segment [

18]. The diagnosis of phlebitis can be established exclusively through clinical examination; however, additional investigations may prove beneficial for staging and identifying associated risk factors (echo-Doppler, D-dimer, and blood count).

Traditionally, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention has recommended changing PIV sites and administration sets at least every 96 hours [

19]. A multicenter trial in Brazil (RESPECT trial) investigated the non-inferiority of clinically indicated PIV catheter replacement compared to routine replacement every 96 hours. Daily cannula replacement is associated with a decreased risk of developing catheter phlebitis but with increased costs and patient discomfort during insertion [

20].

To reduce the risk of catheter phlebitis, careful monitoring of peripheral venous catheters during the entire treatment period is recommended and removed as soon as they are no longer needed. Therapeutic management of catheter phlebitis should consider the presence of risk factors [

21].

Materials and Methods

This retrospective study included 232 patients hospitalized at the Iasi Emergency Clinical Hospital who needed the installation of a peripheral venous catheter for specialized treatment and who had developed catheter phlebitis at various stages of severity between 2017 and 2021. Most patients came from the departments of gastroenterology (56%) and internal medicine (21%), followed by cardiology (12%), oncology (4,5%), hematology (2%), neurosurgery (1,5%), and other specialties (3%); 134 patients required surgical treatment. Data regarding age, sex, risk factors, anatomic site of the venous catheter, associated diseases, complications, and therapeutic management were analyzed using medical statistics software.

Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

Patients from several departments of the hospital who required admission to the plastic surgery department for specialized treatment were included in the study. Patients diagnosed with catheter phlebitis in the early stages and treated in a specialized outpatient setting were excluded.

Results and Discussion

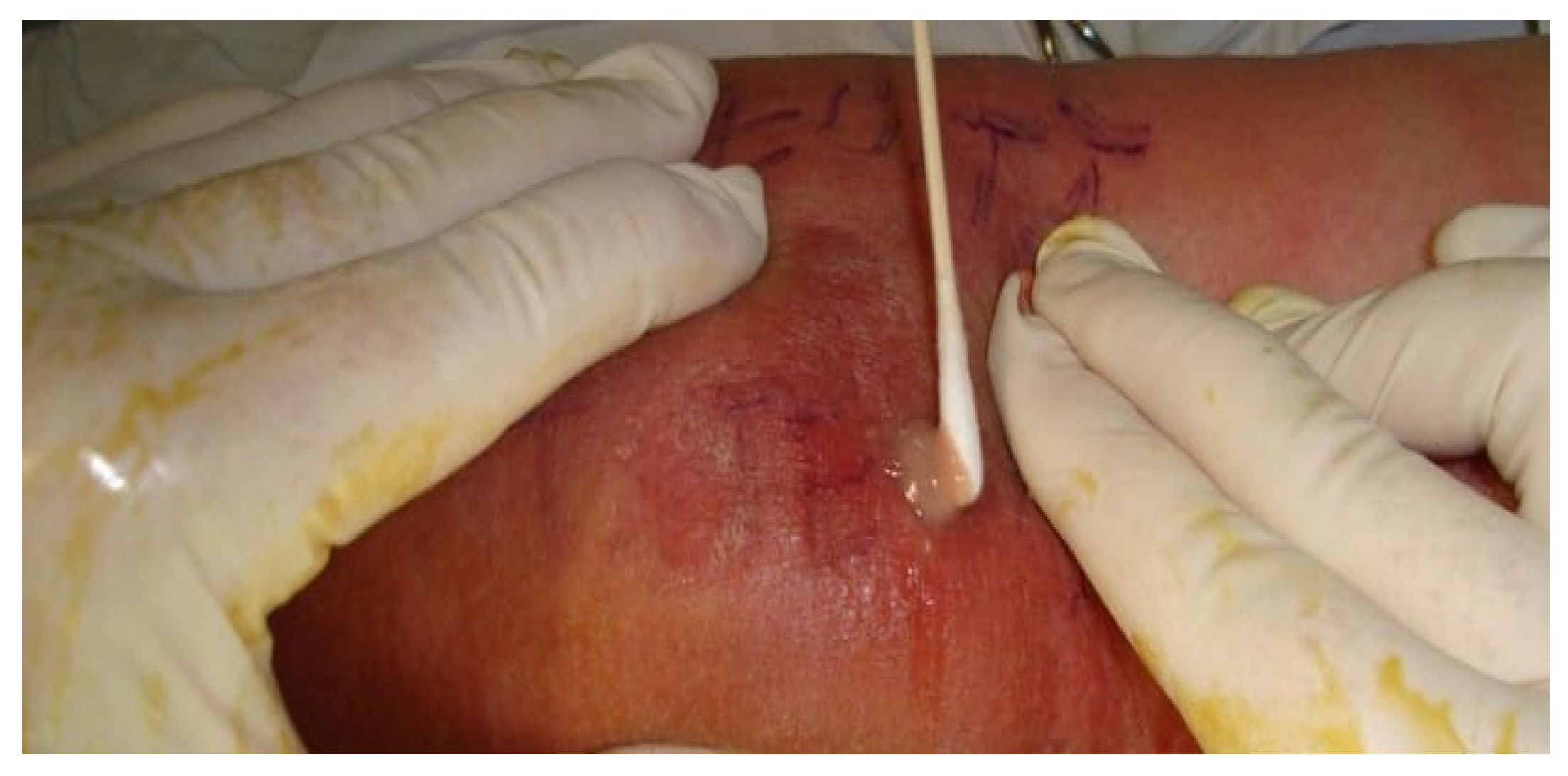

The etiology of phlebitis is multifactorial and may cause various symptoms, ranging from minor discomfort to septic conditions, which require surgical treatment. In the early stages, patients with phlebitis accuse the appearance of edema and local erythema, which can progress even after catheter removal (

Figure 1).

Mechanical damage may be the result of mobilization of the cannula inside the vein causing friction, especially if the size of the cannula is too large compared to the size of the vein. Among irritating substances, cytostatics were the most common (48%), followed by antibiotics (29%), amiodarone (16%), and calcium products (7%). Other studies have demonstrated that intravenous administration of amiodarone increases the risk of phlebitis (8,9).

During clinical examination, all patients who required surgical treatment presented with local, regional, or extensive edema, erythema, local pain, and a palpable venous cord. Other clinical signs were present in variable proportions, including lymphangitis (73,8%), axillary adenopathy (18,6%), high fever (5,9%), chills (90,2%), and abscesses at the venipuncture site (26,1%) (

Figure 2). Almost half of the examined patients had multiple punctures at the level of a single vein: two punctures (29,74%), three punctures (6,46%), and four punctures (1,29%). In 6,7% of the cases, the patients had catheter phlebitis in both thoracic limbs and 8,2% of patients had multiple phlebitis in the same limb: hand and forearm (4,47%), forearm and elbow (2,98%), or hand, forearm, and elbow (0,74%).

Bacteriological examination of the collected local secretions (

Figure 3) showed positive results in 72 cases.

Staphylococcus aureus was the most common microbial agent (55,55%), followed by MRSA (19,44%), gram-negative bacteria (12,48%),

Acinetobacter (6,94%),

Escherichia coli (4,16%), and

Pseudomonas aeruginosa (1,38%). In 12,53% other types of bacteria were involved.

Among patients who had positive cultures, 11 had high fever with positive blood cultures, requiring admission to the intensive care unit for the treatment of hemodynamic imbalances and correction of anemia. In 16% of cases, patients necessitated implantation of a central venous catheter, which can be utilized for an extended duration with reduced complications compared to a peripheral venous catheter. Histopathological examination of the excised venous cord revealed phlebitis and an intravascular thrombus. Endothelial lesions and perivenous inflammatory infiltrates were detected in 1/3 of cases. All surgical patients were treated with antibiotics, anti-inflammatory drugs, and anticoagulants. The most frequent surgical interventions performed were evacuation of purulent secretions, surgical debridement, and excision of the inflamed vein under local anesthesia (91%).

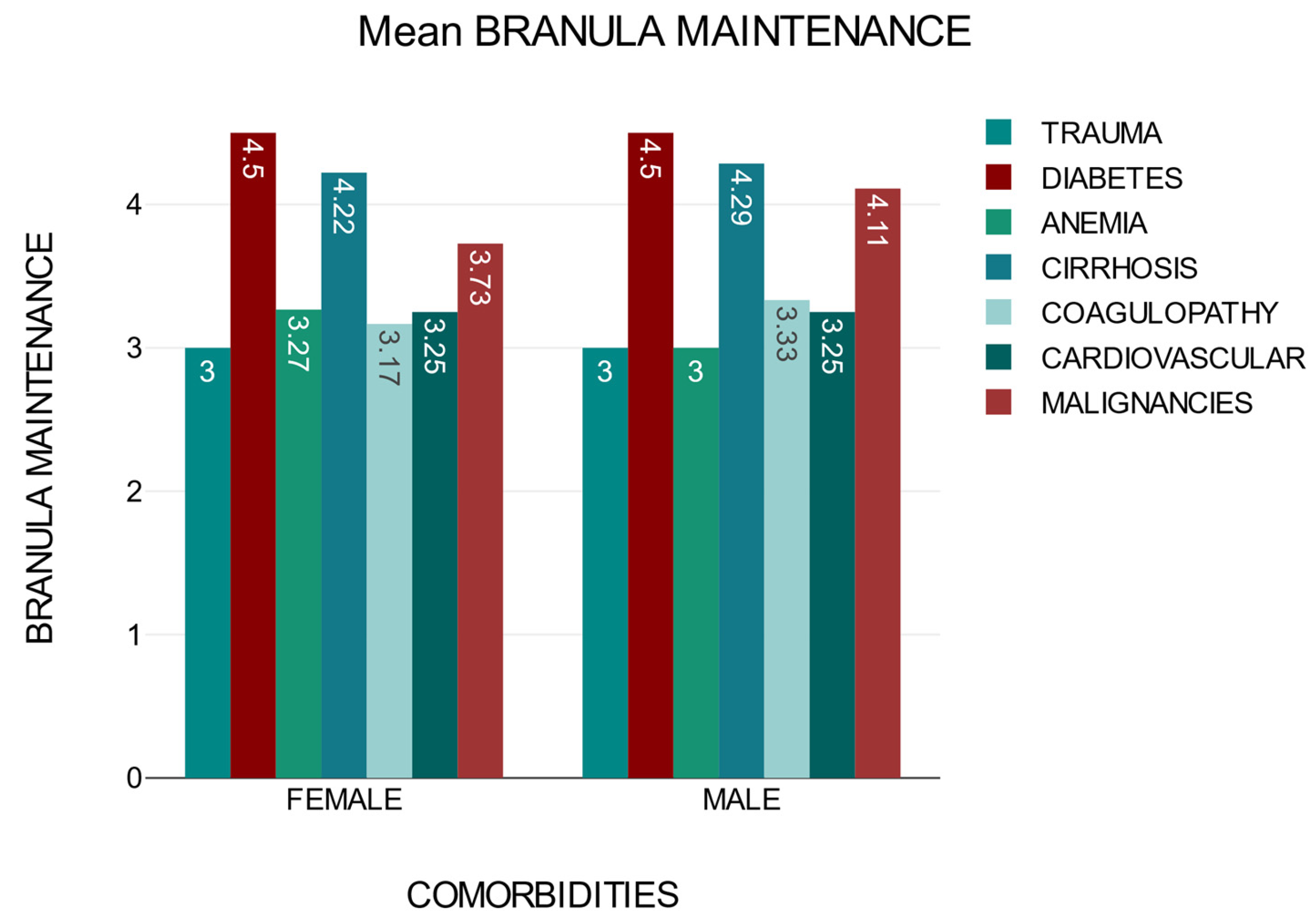

The time of cannula maintenance until the first sign of phlebitis may vary depending on the presence of comorbidities. Patients with diabetes, cirrhosis, and neoplasia are at a higher risk of developing catheter phlebitis during intravenous treatment, regardless of sex (

Figure 4).

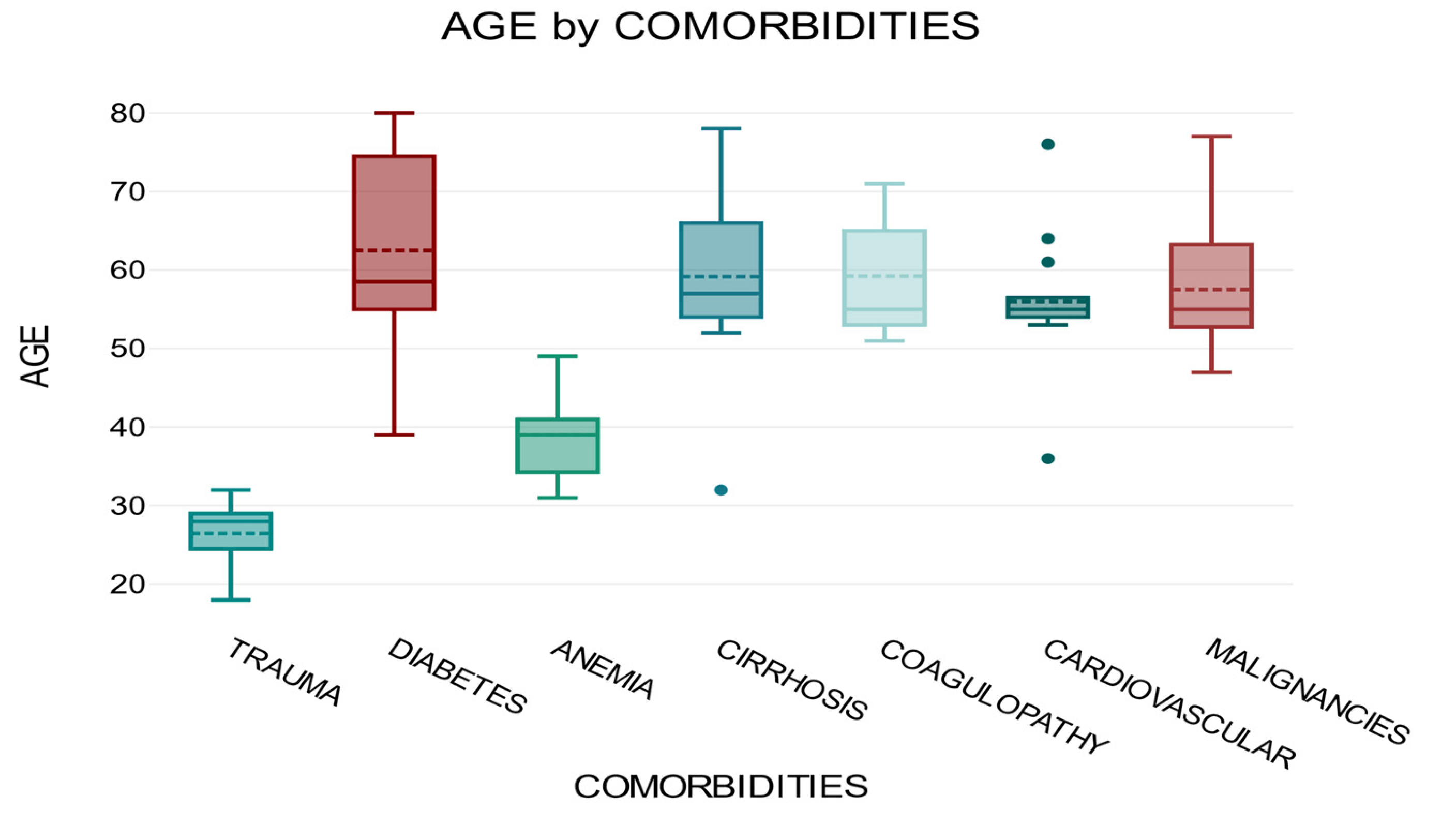

A logistic regression analysis was performed to examine the relationship between

comorbidities and

age (

Table 1).

The average for the trauma group was 26.45, for the diabetes group was 62.5, for the anemia group was 39, for the cirrhosis group was 59.16, for the coagulopathy group was 59.22, for the cardiovascular group was 56, and for the malignancy group was 57.5. The overall average for all groups was 53.74.

One-way ANOVA analysis of variance showed that there was a significant correlation between

comorbidities and

age, F = 39.39,

p <0.001 (

Figure 5).

We used t-tests for independent samples and Levene’s test to demonstrate a correspondence between

branula maintenance and

gender. The statistical results (

Table 2) showed that the

female group had lower values for the dependent variable

branula maintenance (

M = 3.66,

SD = 0.81) than the

male group (

M = 4.05,

SD = 0.73). Levene’s test of equality of variance yielded a p-value of 0.019, which is below the 5% significance level.

A two-tailed t-test for independent samples showed that the difference between females and males concerning the dependent variable branula maintenance was statistically significant, t(131.97) = -2.9, p<.001, 95% confidence interval [-0.65, -0.12].

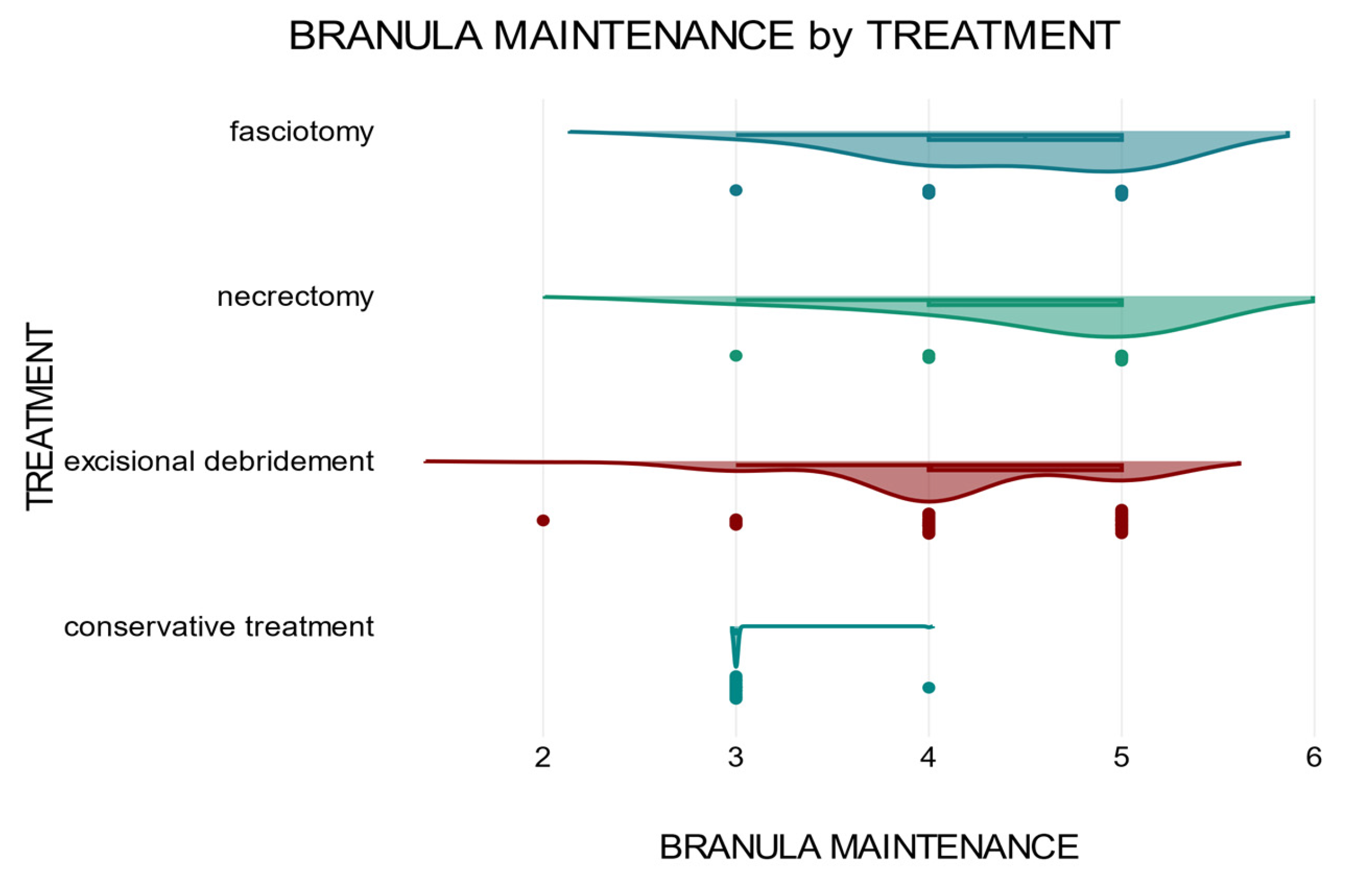

The duration of maintenance of the peripheral venous catheter also influences the therapeutic approach. Patients who required extensive and complex surgical treatments had a longer cannula maintenance time and delayed initiation of specialized treatment than patients who received early treatment. A two-way ANOVA was conducted to test whether there was a correlation between the two variables

gender and

treatment concerning the dependent variable

branula maintenance (

Figure 6).

The two-way ANOVA analysis showed that there was a significant correlation between the independent variable treatment in relation to the dependent variable branula maintenance p<.001 and that there was no interaction between the two variables sex and treatment in relation to the dependent variable, branula maintenance p=1.

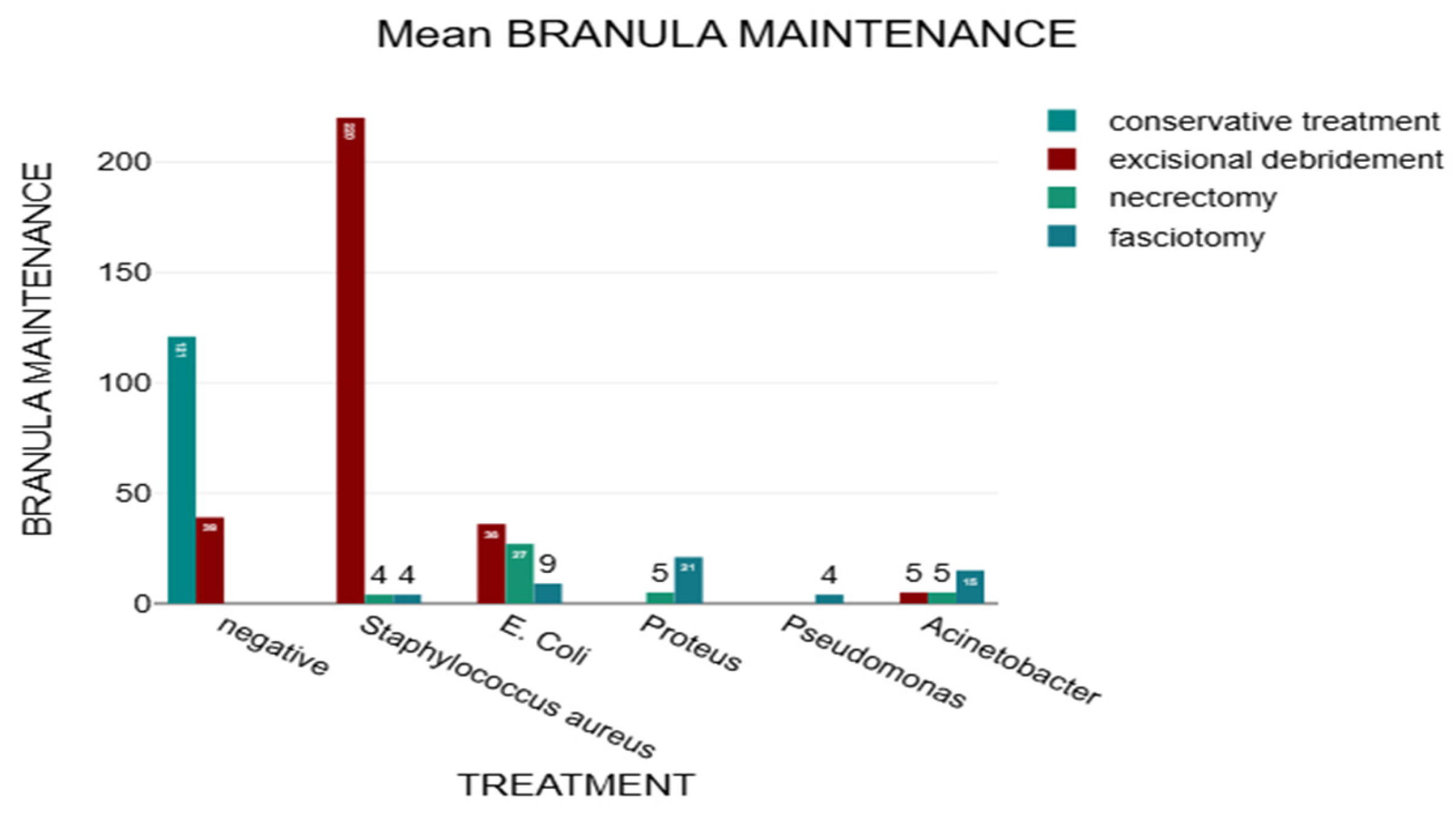

In this study, we analyzed how therapeutic management was influenced by the type of pathogenic germ identified after bacteriological examination (

Figure 7). Staphylococcus aureus is the most common, but the infections caused by them are less aggressive, in comparison with infections caused by Proteus and Pseudomonas, which require complex surgical interventions, such as necrectomy and fasciectomy.

A Chi2 test was performed to highlight the correlation between bacteriological examination and treatment, and the results showed a statistically significant relationship between bacteriological examination and treatment, χ²(15) = 200.17, p <.001, Cramér’s V = 0.71. The calculated p-value of <.001 was lower than the defined significance level of 5%.

A small number of patients required additional procedures with orotracheal intubation, such as fasciotomy (six patients) and covering skin defects with skin grafts (nine patients), which prolonged the length of hospitalization from to 5-7 days to 14-21 days. Severe complications, such as extension of inflammation and extensive necrotizing fasciitis occurred in 3,6% of the patients, with a mortality rate of 0,86% related to the total number of patients diagnosed with catheter phlebitis.

Discussion

The incidence of phlebitis ranges from 12.9% to 31.4% [

22]. Key nursing interventions for preventing phlebitis include maintaining asepsis, choosing appropriate dressings, controlling infusion volumes, and regularly monitoring clinical signs for early detection of complications [

23,

24,

25]. The occurrence of phlebitis is influenced by the nature of the infused substances [

6]. In our study, chemotherapy was associated with the highest risk of catheter phlebitis.

In low-risk episodes of catheter phlebitis caused by coagulase-negative staphylococci, antibiotic therapy may be unnecessary after catheter removal. A randomized clinical trial suggested that managing these cases without antibiotics can be as safe and effective as the standard practice of administering antibiotics for 5–7 days [

26]. However, in severe cases or when dealing with specific pathogens, antibiotic therapy is recommended. For instance, in a study involving rabbits with catheter-related infections, the use of antibiotics (vancomycin-heparin or minocycline-EDTA) was effective in preventing catheter colonization, bacteremia, and phlebitis [

27]. Catheter-associated phlebitis can occur even after catheter removal, with more than 40% of cases developing more than 24 hours after withdrawal [

28,

29]. This suggests that the timing of antibiotic administration should be considered beyond the immediate catheter removal period. The decision to use antibiotic therapy for catheter phlebitis should be based on the severity of the infection, pathogenic germs, and the patient’s risk factors. Although low-risk cases may be managed without antibiotics, more severe infections or those caused by specific pathogens may require antibiotic treatment [

30]. Additional research is necessary to establish guidelines for antibiotic administration in various types of catheter phlebitis.

The incidence of catheter phlebitis diagnosed in advanced stages requiring surgical procedures in addition to medical treatment was 57,75%, with the most frequent location being at the level of the distal veins. Therefore, distal metacarpal vein catheterization should be avoided to reduce the incidence of catheter-related phlebitis [

31].

The optimal indwelling time for intravenous catheters to prevent phlebitis has been the subject of debate and research. Routine replacement every 72 h reduces the risk of phlebitis in patients with comorbidities [

32,

33,

34]. While the traditional 96-hour replacement guidelines have been widely practiced, evidence suggests that clinically indicated replacement may be a safe and effective alternative [

35,

36,

37]. Our investigation demonstrated a statistically significant association between cannula maintenance, sex, and comorbidities, indicating that the optimal interval for cannula replacement varies according to associated risk factors. Female sex has been identified as a risk factor for peripheral catheter phlebitis, but studies on central venous catheter-related infections (CRBSIs) have not specifically identified sex as a significant risk factor [

38]. Other factors, such as catheter type, duration of catheterization, and patient characteristics, including age and comorbidities, are more prominently associated with CRBSI risk [

39,

40].

The most common diseases associated with catheter phlebitis were neoplasia (48,7%), cardiovascular diseases (46,98%), liver cirrhosis (23,27%), coagulopathy (7,32%), anemia (7,75%), polytrauma (4,74%), diabetes (5,17%), and chronic kidney disease (5,17%). Patients with specific comorbidities, including neoplasms, liver cirrhosis, hemodialysis, or diabetes, have an elevated risk of developing catheter phlebitis with extensive local infections [

41]. The administration of probiotics in dietary supplements containing microorganisms that are beneficial to the intestinal microbiota and maintain optimal immune function may contribute to the prevention of localized and systemic infections [

42]. Patients with diabetes and malignancies are at an increased risk of developing depression and other mental disorders that can negatively influence their local evolution [

43,

44,

45,

46]. For these patients, it is recommended to examine the insertion site multiple times daily and remove the peripheral venous catheter at the appearance of the first signs of phlebitis, as inflammatory processes may continue to progress even after catheter removal [

47]. To ensure appropriate follow-up care for these patients, adequate training of the nursing personnel is necessary [

48,

49].

Appropriate selection of catheter type according to vein size and insertion site is recommended to mitigate the risk of phlebitis [

50]. Furthermore, the peripheral venous catheter insertion technique influences the risk of catheter-related phlebitis. The use of polyurethane catheters placed at a lower angle, almost parallel to the vessel, has been shown to reduce the risk of phlebitis [

51,

52].

Automated artificial intelligence systems can be utilized in the diagnosis of cutaneous injuries, offering potential diagnostic support and expanded care [

53]. This application could facilitate the early detection of catheter-associated phlebitis and potentially reduce the incidence of cases requiring surgical intervention.

Prompt action and continued observation are crucial for managing catheter-phlebitis complications [

54]. Further research is needed to develop targeted therapeutic strategies and provide a comprehensive approach for phlebitis catheter-related cases.

Conclusions

Catheter-associated phlebitis is a major health concern. This study demonstrated that catheterization duration influences the severity of phlebitis, particularly in patients with specific comorbidities, including neoplasms, hepatic cirrhosis, and diabetes mellitus, depending on age and sex. Therapeutic management requires catheter removal, patient monitoring, and specialized treatment. Surgical intervention is recommended in patients with unfavorable progression. To decrease the risk of phlebitis, it is imperative to conduct daily inspections of the catheter insertion sites, implement appropriate nursing care protocols, and minimize exposure to known risk factors. In conclusion, therapeutic management of catheter phlebitis should consider the existence of risk factors.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization: C.S., C.T., and L.A.; methodology: C.S., L.A., I.T., F.P., and C.T.; validation: C.S., and C.T.; formal analysis: C.S. and C.T.; investigation: C.S., L.A., M.B., I.T., F.P., and C.T.; data curation: C.S.; writing—original draft preparation: C.S. and C.T.; writing—review and editing, C.S., L.A, F.P., I.T. and M.B.; visualization, C.S., L.A., M.B., I.T., and F.P.; supervision: C.T. and L.A.; project administration: C.S. All the authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

No external funding was received for this study.

Institutional Review Board Statement

This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Sf. Spiridon” Emergency Clinical Hospital Iasi with no. 63/12.12.2021, in compliance with the ethical and deontological rules for medical and research practice.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data published in this research are available upon request from the first author and the corresponding authors.

Conflicts of Interest statement

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

References

- Lin, S.W.; Chen, S.C.; Huang, F.Y.; Lee, M.Y. Chang CC. Effects of a Clinically Indicated Peripheral Intravenous Replacement on Indwelling Time and Complications of Peripheral Intravenous Catheters in Pediatric Patients: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021, 18(7):3795.. [CrossRef]

- Noshy, M.; Mohamed, M. M.; Abd El- Reheem, H. A. E. R. Peripheral Intravenous Catheter-Related Phlebitis, Infiltration, and Its Contributing Factors among Patients at Port Said Hospitals. Port Said Scientific Journal of Nursing. 2023, 10(3): 284-308. [CrossRef]

- Mandal, Abhijit; Raghu, K. Study on incidence of phlebitis following the use of pherpheral intravenous catheter. Journal of Family Medicine and Primary Care. 2019, 8(9):p 2827-283. [CrossRef]

- Soi, V.; Kumbar, L.; Yee, J., Moore, C. Prevention of catheter-related bloodstream infections in patients on hemodialysis: Challenges and management strategies. International Journal of Nephrology and Renovascular Disease. 2016, 9(3), 95. [CrossRef]

- Yasuda, H.; Rickard, C.M.; Marsh, N.; Yamamoto, R.; Kotani, Y.; Kishihara, Y. et al. AMOR-NUS study group. Risk factors for peripheral intravascular catheter-related phlebitis in critically ill patients: Analysis of 3429 catheters from 23 Japanese intensive care units. Ann Intensive Care. 2022, 12(1):33. [CrossRef]

- Atay, S.; Sen, S.; Cukurlu, D. Phlebitis-related peripheral venous catheterization and the associated risk factors. Niger J Clin Pract. 2018, 21(7):827-831. [CrossRef]

- Gallant, P.; Schultz, A. A. Evaluation of a Visual Infusion Phlebitis Scale for Determining Appropriate Discontinuation of Peripheral Intravenous Catheters. Journal of Infusion Nursing. 2006, 29(6), 338–345. [CrossRef]

- Kurniawan, R.; Roslianti, E.; Abdul Robbi, Y.S; Fajar, D.R. et al. The Placement of Intravenous Catheter Installation with Phlebitis in Disease in In-Patient Room of Ciamis Regional Public Hospital J. Phys.: Conf. Ser. 2019, 1179 012143. [CrossRef]

- Gavin, N.C.; Kleidon, T.M; Larsen, E.; O’Brien, C.; Ullman, A.; Northfield, S. et al. A comparison of hydrophobic polyurethane and polyurethane peripherally inserted central catheter: Results from a feasibility randomized controlled trial. Trials. 2020, 21(1):787. [CrossRef]

- Pérez-Granda, M.J.; Bouza, E.; Pinilla, B.; Cruces, R.; González, A.; Millán, J.; Guembe, M. Randomized clinical trial analyzing maintenance of peripheral venous catheters in an internal medicine unit: Heparin vs. saline. PLoS ONE. 2020, 15(1):e0226251. [CrossRef]

- Dixon, H.A.; Hort, A.L.; Wright, C.M. Amiodarone-induced phlebitis remains an issue in spite of measures to reduce its occurrence. J Vasc Access. 2019, 20(6):786-787. [CrossRef]

- Drouet, M.; Cuvelier, E.; Chai, F.; Genay, S.; Odou, P.; Décaudin, B. Disturbance of Vancomycin Infusion Flow during Multidrug Infusion: Influence on Endothelial Cell Toxicity. Antibiotics (Basel). 2021, 11(1):16. [CrossRef]

- Moritz, M.L.; Ayus, J.C.; Nelson, J.B. Administration of 3% Sodium Chloride and Local Infusion Reactions. Children (Basel). 2022, 9(8):1245. [CrossRef]

- Guanche-Sicilia, A.; Sánchez-Gómez, M.B.; Castro-Peraza, M.E.; Rodríguez-Gómez, J.Á.; Gómez-Salgado, J.; Duarte-Clíments, G. Prevention and Treatment of Phlebitis Secondary to the Insertion of a Peripheral Venous Catheter: A Scoping Review from a Nursing Perspective. Healthcare (Basel). 2021, 9(5):611. [CrossRef]

- Cicolini, G.; Manzoli, L.; Simonetti, V.; Flacco, M. E.; Comparcini, D.; Capasso, L. Et al. Phlebitis risk varies by peripheral venous catheter site and increases after 96hours: A large multi-centre prospective study. Journal of Advanced Nursing. 2014, 70(11), 2539–2549. [CrossRef]

- Zingg, W.; Barton, A.; Bitmead, J.; Eggimann, P.; Pujol, M.; Simon, A.; Tatzel, J. Best practice in the use of peripheral venous catheters: A scoping review and expert consensus. Infect Prev Pract. 2023, 5(2):100271. [CrossRef]

- Garcia-Expósito, J.; Sánchez-Meca, J.; Almenta-Saavedra, J.A.; Llubes-Arrià, L.; Torné-Ruiz, A.; Roca, J. Peripheral venous catheter-related phlebitis: A meta-analysis of topical treatment. Nurs Open. 2023, 10(3):1270-1280. [CrossRef]

- Mermel, L.A.; Farr, B.M.; Sherertz, R.J.; Raad, I.I.; O’Grady, N.; Harris, J.S.; Craven, D.E. Infectious Diseases Society of America; American College of Critical Care Medicine; Society for Healthcare Epidemiology of America. Guidelines for the management of intravascular catheter-related infections. Clin Infect Dis. 2001, 32(9):1249-72. [CrossRef]

- Lulie, M.; Tadesse, A.; Tsegaye, T.; Yesuf, T.; Silamsaw, M. Incidence of peripheral intravenous catheter phlebitis and its associated factors among patients admitted to University of Gondar hospital, Northwest Ethiopia: A prospective, observational study. Thromb J. 2021, 19(1):48. [CrossRef]

- Vendramim, P.; Avelar, A. F. M.; Rickard, C. M., Pedreira, M. D. L. G. The RESPECT trial–Replacement of peripheral intravenous catheters according to clinical reasons or every 96 hours: A randomized, controlled, non-inferiority trial. International Journal of Nursing Studies. 2020, 107, 103504. [CrossRef]

- Lladó Maura, Y.; Rodríguez Moreno, M. J.; Lluch Garvi, V.; Fusté, E.; Rodríguez-Rodríguez, A.; Almendral, A. et al. Care bundle for the prevention of peripheral venous catheter blood stream infections at a secondary care university hospital: Implementation and results. Infection, Disease & Health. 2023, 28(3), 159–167. [CrossRef]

- Cernuda Martínez, J. A.; Suárez Mier, M. B.; Martínez Ortega, M. D. C.; Casas Rodríguez, R.; Villafranca Renes, C.; Del Río Pisabarro, C. Risk factors and incidence of peripheral venous catheters-related phlebitis between 2017 and 2021: A multicentre study (Flebitis Zero Project). The Journal of Vascular Access. 2021, 25(6), 1835–1841. [CrossRef]

- Braga, L.M.; Parreira, P.M.; Oliveira, A.S.S.; Mónico, L.D.S.M.; Arreguy-Sena, C.; Henriques, M.A. Phlebitis and infiltration: Vascular trauma associated with the peripheral venous catheter. Rev Lat Am Enfermagem. 2018, 26:e3002. [CrossRef]

- Oragano, C.A.; Patton. D.; Moore, Z. Phlebitis in intravenous Amiodarone Administration: Incidence and contributing factors. Crit Care Nurse. 2019, 39:e1-12. [CrossRef]

- Marsh N, Webster J, Mihala G, Rickard CM. Devices and dressings to secure peripheral venous catheters to prevent complications. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015 Jun 12;2015(6):CD011070. PMID: 26068958; PMCID: PMC10686038. [CrossRef]

- Abolfotouh, M. A.; Salam, M.; Bani-Mustafa, A.; Balkhy, H. H.; White, D. Prospective study of incidence and predictors of peripheral intravenous catheter-induced complications. Therapeutics and Clinical Risk Management. 2014, 10(3), 993. [CrossRef]

- Raad, I.; Tcholakian, R. K.; Sherertz, R.; Hachem, R. (2002). Efficacy of minocycline and EDTA lock solution in preventing catheter-related bacteremia, septic phlebitis, and endocarditis in rabbits. Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy. 2002, 46(2), 327–332. [CrossRef]

- Urbanetto, J.de S.; Peixoto, C.G.; May, T.A. Incidence of phlebitis associated with the use of peripheral IV catheter and following catheter removal. Rev Lat Am Enfermagem. 2016, 24:e2746. [CrossRef]

- Malach, T.; Olsha, O.; Broide, E.; Raveh, D.; Rudensky, B.; Yinnon, A. M. et al. Prospective surveillance of phlebitis associated with peripheral intravenous catheters. American Journal of Infection Control. 2006, 34(5), 308–312. [CrossRef]

- Yamin, D. H.; Harun, A.; Husin, A. Risk Factors of Candida parapsilosis Catheter-Related Bloodstream Infection. Frontiers in Public Health. 2021, 9(Suppl 1). [CrossRef]

- Karadeniz, G;, Kutlu, N.; Tatlisumak, E.; Özbakkaloğlu, B. Nurses’ knowledge regarding patients with intravenous catheters and phlebitis interventions. Journal of Vascular Nursing. 2023, 21(2), 44–47. [CrossRef]

- Webster, J.; Osborne, S.; Rickard, C.M.; Marsh, N. Clinically-indicated replacement versus routine replacement of peripheral venous catheters. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2019, 1(1):CD007798. [CrossRef]

- Catney, M. R.; Connelly, T.; Hillis, S.; Keller, S.; Wagner, K.; Price, D. et al. Relationship between peripheral intravenous catheter Dwell time and the development of phlebitis and infiltration. Journal of Infusion Nursing. 2001, 24(5), 332–341. [CrossRef]

- Mestre Roca, G.; Berbel Bertolo, C.; Tortajada Lopez, P.; Gallemi Samaranch, G.; Aguilar Ramirez, M. C.; Caylà Buqueras, J. Et al. Assessing the influence of risk factors on rates and dynamics of peripheral vein phlebitis: An observational cohort study. Medicina Clínica. 2012, 139(5), 185–191. [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.Y.; Chen, W.C.; Chen, J.Y.; Lai, C.C.; Wei, Y.F. Comparison of clinically indicated replacement and routine replacement of peripheral intravenous catheters: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Front. Med. 2022, 9:964096. [CrossRef]

- Cornely, O. A.; Waldschmidt, D.; Pauls, R.; Bethe, U. Peripheral Teflon catheters: Factors determining incidence of phlebitis and duration of cannulation. Infection Control and Hospital Epidemiology. 2002, 23(5), 249–253. [CrossRef]

- Tan, Y. H. G.; Sim, C.; Tai, W. L. S.; Ng, H. L. I. Optimising peripheral venous catheter usage in the general inpatient ward: A prospective observational study. Journal of Clinical Nursing. 2016, 26(1–2), 133–139. [CrossRef]

- Villalba-Nicolau, M.; Chover-Sierra, E.; Saus-Ortega, C.; Ballestar-Tarín, M.L.; Chover-Sierra, P.; Martínez-Sabater, A. Usefulness of Midline Catheters versus Peripheral Venous Catheters in an Inpatient Unit: A Pilot Randomized Clinical Trial. Nurs. Rep. 2022, 12, 814-823. [CrossRef]

- Puoti, M. G.; D’Eusebio, C.; Littlechild, H.; King, E.; Koeglmeier, J.; Hill, S. Risk factors for catheter-related bloodstream infections associated with home parental nutrition in children with intestinal failure: A prospective cohort study. Clinical Nutrition. 2023, 42(11), 2241–2248. [CrossRef]

- Camp, A.; Savoie, K.; Prasanna, N. Potassium Chloride-Induced Phlebitis via a Malpositioned Central Venous Catheter. Chest. 2023, 163(6), e253–e254. [CrossRef]

- Weldetensae, M. K. Gebrearegay, H. Berhe, E. Weledegebriel, M. G. Nigusse, A. T. Catheter-Related Blood Stream Infections and Associated Factors Among Hemodialysis Patients in a Tertiary Care Hospital. Infection and Drug Resistance. 2023, 16, 3145–3156. [CrossRef]

- Boev, M.; Stănescu, C.; Turturică, M.; Cotârleţ, M.; Batîr-Marin, D.; Maftei, N. et al. Bioactive Potential of Carrot-Based Products Enriched with Lactobacillus plantarum. Molecules. 2024, 29(4):917. [CrossRef]

- Zakhour, R.; Chaftari, A.-M.; Raad, I. I. Catheter-related infections in patients with haematological malignancies: Novel preventive and therapeutic strategies. The Lancet Infectious Diseases. 2016, 16(11), e241–e250. [CrossRef]

- Anghel, L.; Boev, M.; Stănescu, C.; Mitincu Caramfil, S.; Luca, L.; Muşat, C. L.; Ciubara, A. Depression in the diabetic patient. BRAIN. Broad Research in Artificial Intelligence and Neuroscience. 2023, 14(4), 658-672. [CrossRef]

- Stanescu, C.; Boev, M.; Avram, O.A.; Ciubara, A. Investigating the Connection Between Skin Cancers and Mental Disorders: A Thorough Analysis. BRAIN. Broad Research in Artificial Intelligence and Neuroscience. 2024, 15(3): 118-131. [CrossRef]

- Tamas, C.; Hreniuc, IMJ; Tecuceanu, A.; Ciuntu, BM; Ibanescu, CL; Tamas, I. et al. Non-Melanoma Facial Skin Tumors—The Correspondence between Clinical and Histological Diagnosis. Appl. Sci. 2021 , 11 , 7543. [CrossRef]

- O’Grady, N.P. Alexander, M.; Burns, L.A.; Dellinger, E.P.; Garland, J.; Heard, S.O. et al. Healthcare Infection Control Practices Advisory Committee (HICPAC). Guidelines for the prevention of intravascular catheter-related infections. Clin Infect Dis. 2011, 52(9):e162-93. [CrossRef]

- Shaker, N.Z. Monitoring Peripheral Intravenous Catheters Complications in Pediatric Patients in Erbil City/Iraq. Erbil j. nurs. midwifery [Internet]. 2022, 5(2):105-13. [CrossRef]

- Atay, S.; Yilmaz Kurt, F. Effectiveness of transparent film dressing for peripheral intravenous catheter. J Vasc Access. 2021, 22(1):135-140. [CrossRef]

- Simões, A.M.N.; Vendramim, P.; Pedreira, M.L.G. Risk factors for peripheral intravenous catheter-related phlebitis in adult patients. Rev Esc Enferm USP. 2022, 56:e20210398. [CrossRef]

- Tanabe, H.; Takahashi, T.; Sanada, H.; Oe, M.; Murayama, R.; Komiyama, C.; Yabunaka, K. Low-angled peripheral intravenous catheter tip placement decreases phlebitis. The Journal of Vascular Access. 2016, 17(6), 542–547. [CrossRef]

- Marsh, N.; Webster, J.; Larsen, E.; Genzel, J.; Cooke, M.; Mihala, G. et al. Expert versus generalist inserters for peripheral intravenous catheter insertion: A pilot randomised controlled trial. Trials. 2018, 19(1):564. [CrossRef]

- Poalelungi, D.G.; Musat, C.L.; Fulga, A.; Neagu, M.; Neagu, A.I.; Piraianu, A.I.; Fulga, I. Advancing Patient Care: How Artificial Intelligence Is Transforming Healthcare. J Pers Med. 2023, 13(8):1214.. [CrossRef]

- Yasuda, H.; Yamamoto, R.; Hayashi, Y.; Kotani, Y.; Kishihara Y.; Kondo, N. et al. Occurrence and incidence rate of peripheral intravascular catheter-related phlebitis and complications in critically ill patients: A prospective cohort study (AMOR-VENUS study). Journal of intensive care. 2021, 9, 3 (2021). [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).