1. Introduction

Tumour cells differ from normal cells in their surface antigenic composition, which can trigger immune responses capable of controlling tumour growth. However, immune tolerance and immunosuppressive mechanisms often allow tumours to evade destruction, necessitating novel immunotherapeutic strategies to enhance anti-tumour immunity [

1].

Among the different classes of tumour-associated antigens, cancer-testis antigens (CTAs) occupy a unique niche. CTAs are normally expressed only in immune-privileged sites such as the testes and placenta but are aberrantly upregulated in various tumours, including liver, breast, pancreas, lung, and colorectal cancers [

2,

3,

4]. The expression of CTAs in tumours is associated with oncogenic properties and tumour progression, making them promising targets for immunotherapy [

5,

6] Importantly, CTAs are highly conserved across species, yet subtle structural differences between species make xenogeneic CTAs highly immunogenic, allowing them to overcome immune tolerance mechanisms that suppress responses to self-antigens [

7]. Evidence suggests that xenogeneic vaccines can break immune tolerance by presenting antigens (Ags) as ‘altered self,’ leading to robust T cell-mediated immunity against homologous tumour-associated Ags [

8,

9]. Earlier studies indicate that immunization with xenogeneic tumour-associated Ags can generate cross-reactive immunity and suppress tumour growth in both preclinical and clinical settings. [

10,

11] This type of immunization can disrupt immune tolerance, triggering CD4+ and CD8+ T-cell responses and significant antitumor activity [

11] However, most prior research has focused on mono-antigenic vaccines, which target only a single tumour Ag. Given the heterogeneity of tumour cell populations, monogenic or oligoantigenic vaccines may only eliminate subsets of tumour cells while allowing antigen-negative clones to escape immune attack, leading to disease progression [

1]. Polyantigenic vaccination strategies, which simultaneously target multiple tumour Ags, have been proposed as a superior approach to overcoming tumour antigenic heterogeneity [

12]. This study aims to investigate the potential of a xenogeneic corpuscular vaccine derived from ram spermatogenic tissue, which contains a full spectrum of CTAs, to induce long-term anti-cancer immunity. We hypothesise that this polyantigenic vaccine will be capable of counteracting tumour development and progression by targeting a broad range of tumour cells expressing various CTAs.

Here, we evaluate the efficacy of xenogeneic CTA-based vaccination in a murine model, assessing its ability to modulate immunity and improve survival outcomes in tumour-bearing mice. Our findings provide insights into the potential application of xenogeneic CTAs as a novel strategy for cancer immunoprevention.

2. Materials and Methods

The research received approval from the Institutional Ethics Committee at the Institute of Fundamental and Clinical Immunology (Protocol No. 143 dated 29.11.2023). All animals were housed in a vivarium under conditions compliant with international standards. Animal procedures were conducted in strict accordance with the legislation of the Russian Federation and the provisions of Directive 2010/63/EU of the European Parliament and the Council of the European Union of 22 September 2010 on the protection of animals. All protocols and research methods were approved by the Ethics Committee of the Institute of Fundamental and Clinical Immunology, Novosibirsk, Russia (Protocol No. 143 dated 29.11.2023).

2.1. Mice

Male C57BL/6 mice, aged 4 to 6 months and weighing 18–20 g, were used for all experiments. The animals were obtained from the breeding facility of the Goldberg Research Institute of Pharmacology and Regenerative Medicine (Tomsk, Russia). They were housed with access to autoclaved food and boiled water. All procedures involving animals complied with the legislation of the Russian Federation and Directive 2010/63/EU of the European Parliament and the Council of 22 September 2010 on the protection of animals used in scientific research. Euthanasia was performed by cervical dislocation.

2.2. Tumour Cell Lines

The Lewis lung carcinoma (LLC) and B16 melanoma cell lines were obtained from the N.N. Blokhin Cancer Centre (Moscow, Russia) and maintained in RPMI-1640 medium supplemented with 10% FCS, 2 mM L-glutamine, and antibiotics (all reagents were from Paneco, Moscow, Russia).

2.3. Preparation of Cellular Vaccines

Mature ram testicles were collected and immediately placed on ice. The spermatogenic tissue was then separated from the connective tissue sheaths using a surgical scalpel. The isolated tissue was fragmented into approximately 5 mm pieces using scissors. These tissue fragments were washed with cold distilled water to remove blood. The cells were then gently squeezed from the tissue pieces into pre-cooled phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) using a glass homogeniser. The resulting cell suspension was left to settle for 7–10 minutes to allow large aggregates to precipitate. The collected cells were transferred to a test tube and fixed with a 1% paraformaldehyde solution for 15 minutes at room temperature. Following fixation, the cells were washed three times in PBS by centrifugation. Cells from the spermatogenic tissue of mature mice, as well as cells from ram spleens, were obtained using the same method. All cell preparations intended for immunisation were stored in a frozen state.

2.4. Immunization of Mice and Tumour Implantation

Mice were immunised intramuscularly in the thigh with fixed xenogeneic or syngeneic testicular cells (TCs) or xenogeneic spleen cells (xSCs) at a dose of 5 × 10⁶ cells per mouse, administered three times at seven-day intervals. Fourteen days after the last immunization, the mice were subcutaneously implanted with LLC carcinoma or B16 melanoma cells in the anterior abdominal wall at a dose of 10⁵ cells per mouse. The survival of the mice was monitored daily from the first day after tumour cell implantation.

2.6. Preparation of Antigenic Cell Lysates for Immunological Studies

Viable cells were washed in cold PBS solution, counted and stored in a frozen state until used in experiments.

2.7. MTT Assay for Assessing Immunoreactivity

Spleen cells were cultured in a 96-well plate (2 × 10⁵ cells/well) in RPMI 1640 medium supplemented with 10% FCS, 2 mM L-glutamine, and antibiotics, in the presence of the thawed cells (1 × 10⁵ cells/well) as indicated below, in an atmosphere of 5% CO₂ at 37.5°C for 72 hours. After this period, the plate was centrifuged at 1000 g for 5 minutes, the supernatant was replaced with fresh medium, and 50 μl of MTT (3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide) reagent (MTT assay kit, Abcam, Cambridge, UK) was added to each well. After 3 hours of incubation, 150 μl of solvent (dimethyl sulfoxide, DMSO) was added to the precipitate. Colour development in the wells was recorded using a TriStar LB 941 plate reader (Berthold Technologies, Bad Wildbad, Germany) at a wavelength of 590 nm and expressed in optical density units. The intensity of the colouration was proportional to the number of viable cells in the wells.

2.8. Flow Cytometry

To determine the CD4+CD25+Foxp3+ and CD4+CD44+CD62L+ cell subpopulations, spleen cells were stained with fluorochrome-conjugated mouse monoclonal antibodies. The staining was performed using a combination of antibodies according to the protocol recommended by the manufacturer, eBioscience. The content of the cell populations was determined by flow cytometry using the BD FACSCalibur instrument (BD Biosciences, Franklin Lakes, USA).

2.9. Measurement of Interleukin 10 (IL-10) and Interferon-Gamma (IFN-γ) Levels

The levels of IL-10 and IFNγ were measured in the plasma of mice using an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) with test kits from Cloud-Clone Corp. (CCC, Wuhan, China), according to the manufacturer's instructions.

2.10. Statistical Analysis

Each experimental and control group consisted of 10 mice. The presented data reflect the results of at least two identical experiments. Statistical analysis of the results was performed using GraphPad Prism 8 software (GraphPad Software, San Diego, USA), applying the non-parametric Mann-Whitney test. Mouse survival analysis was conducted using the Kaplan-Meier method, and the significance of survival differences was assessed using the Mantel-Cox Log-Rank test.

3. Results

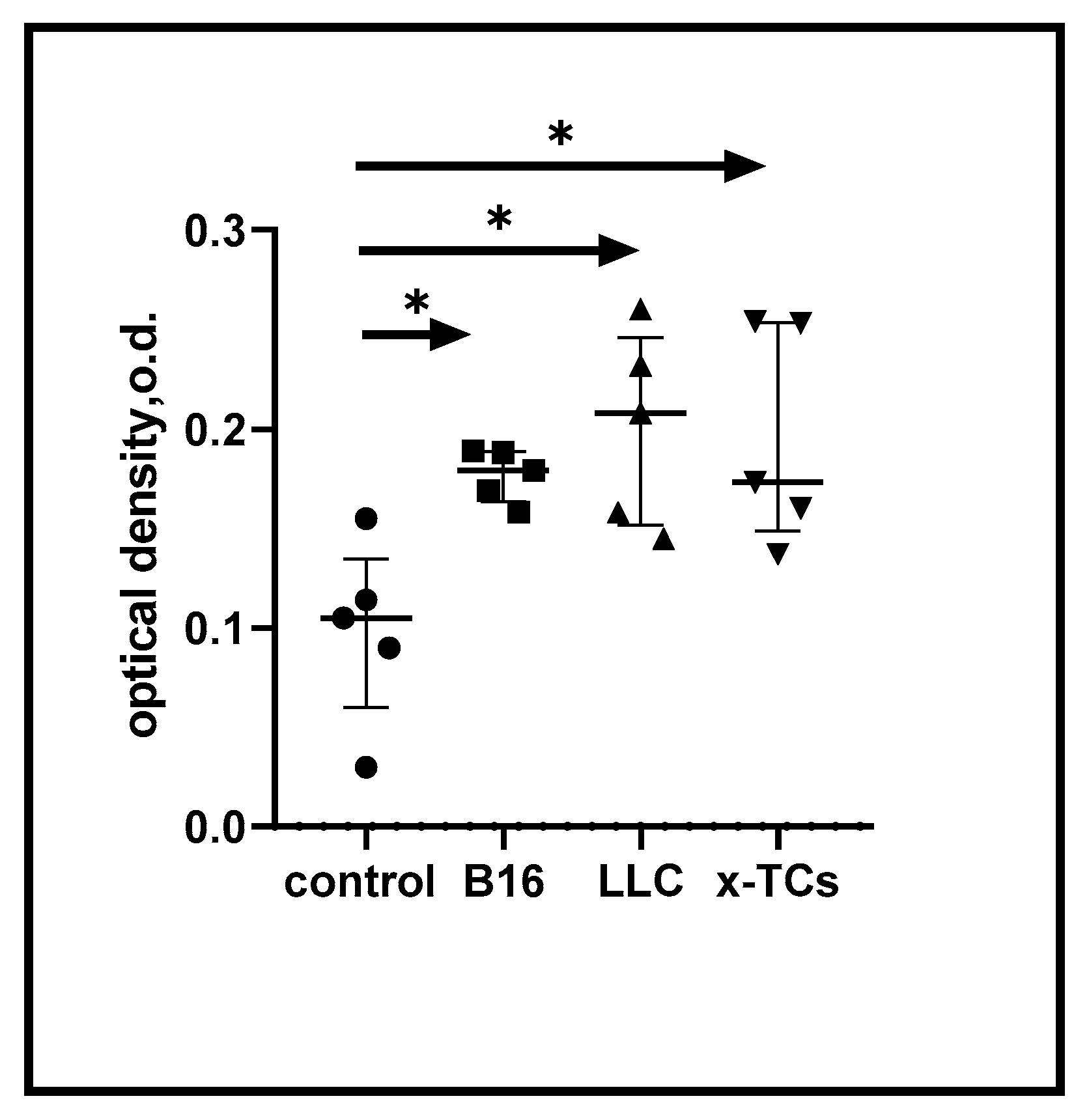

3.1. Vaccination with Xenogeneic Testicular Cells Induces Cross-Reactive Anti-Tumour Immunity

According to our initial hypothesis, immunisation of mice with xenogeneic CTA should induce cross-reactive immune responses against syngeneic CTAs expressed on tumour cells.

Figure 1 shows the enhanced immune reactivity of spleen cells from mice immunised three times with xenogeneic testicular cells (xTCs) in the presence of LLC carcinoma and B16 melanoma Ags. This immune reactivity was consistent and proportionate to the response of spleen cells to the vaccine-associated tumour cell Ags. In control experiments, no immune reactivity was detected in spleen cells from unvaccinated animals (data not shown). Overall, these data suggest the generation of cross-reactive anti-cancer immune responses in mice following immunisation with xTCs.

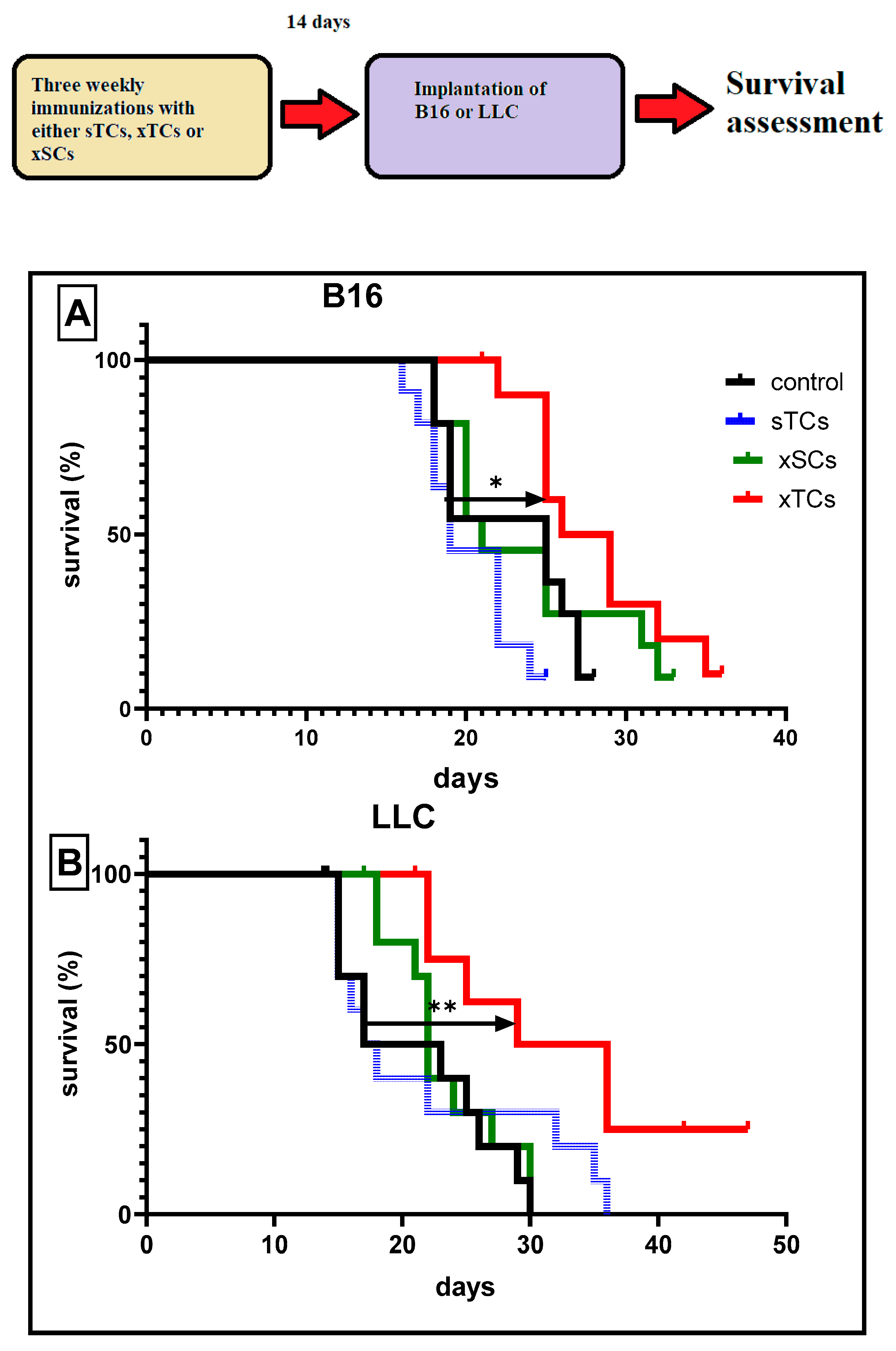

3.2. Prophylactic Vaccination with Xenogeneic Testicular Cells Enhances the Survival of Tumour-Bearing Mice

In subsequent experiments, we investigated whether xTC-induced cross-reactivity could impact tumour development. The data suggest that three immunisations with xTCs significantly increased the survival rates of mice implanted with B16 melanoma (

Figure 2A) or LLC carcinoma (

Figure 2B), as assessed 14 days after the final immunisation. Moreover, this protective effect was long-lasting, with 30% of vaccinated mice implanted with LLC carcinoma surviving throughout the entire observation period (6 months).

Importantly, control experiments showed that immunisation with syngeneic TСs (sTCs) or normal xenogeneic (ram) spleen cells (xSCs) did not affect survival rates. These findings are consistent with the interpretation that immune cross-reactivity induced by xenogeneic CTAs leads to the generation of significant anti-cancer immune reactivity.

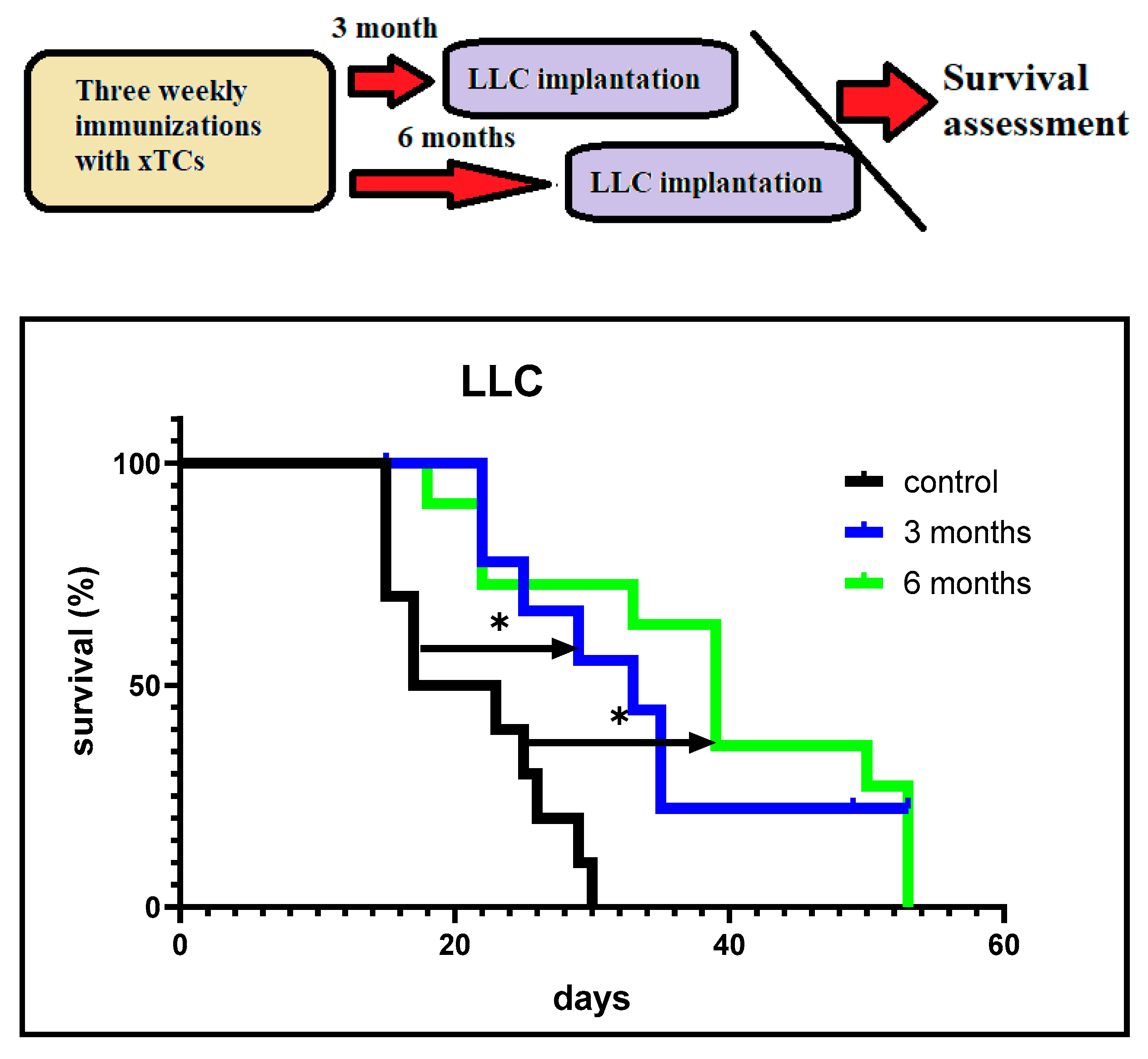

We also investigated the duration of the anti-cancer protection induced by xenogeneic CTAs. In these experiments, mice were implanted with LLC carcinoma cells 3 and 6 months after the last immunisation.

Figure 3 shows significantly higher survival rates in both groups of vaccinated tumour-bearing mice compared to the control unvaccinated mice. Moreover, about 30% of vaccinated mice implanted with LLC carcinoma cells 3 months after the last vaccination survived, whereas no mice survived in the group implanted 6 months after the last immunisation. However, significantly higher survival rates were observed in the latter group compared to the control group.

Taken together, the data suggest that vaccination with xenogeneic CTA was highly effective in generating long-lasting, immune-mediated anti-cancer protection for up to 6 months.

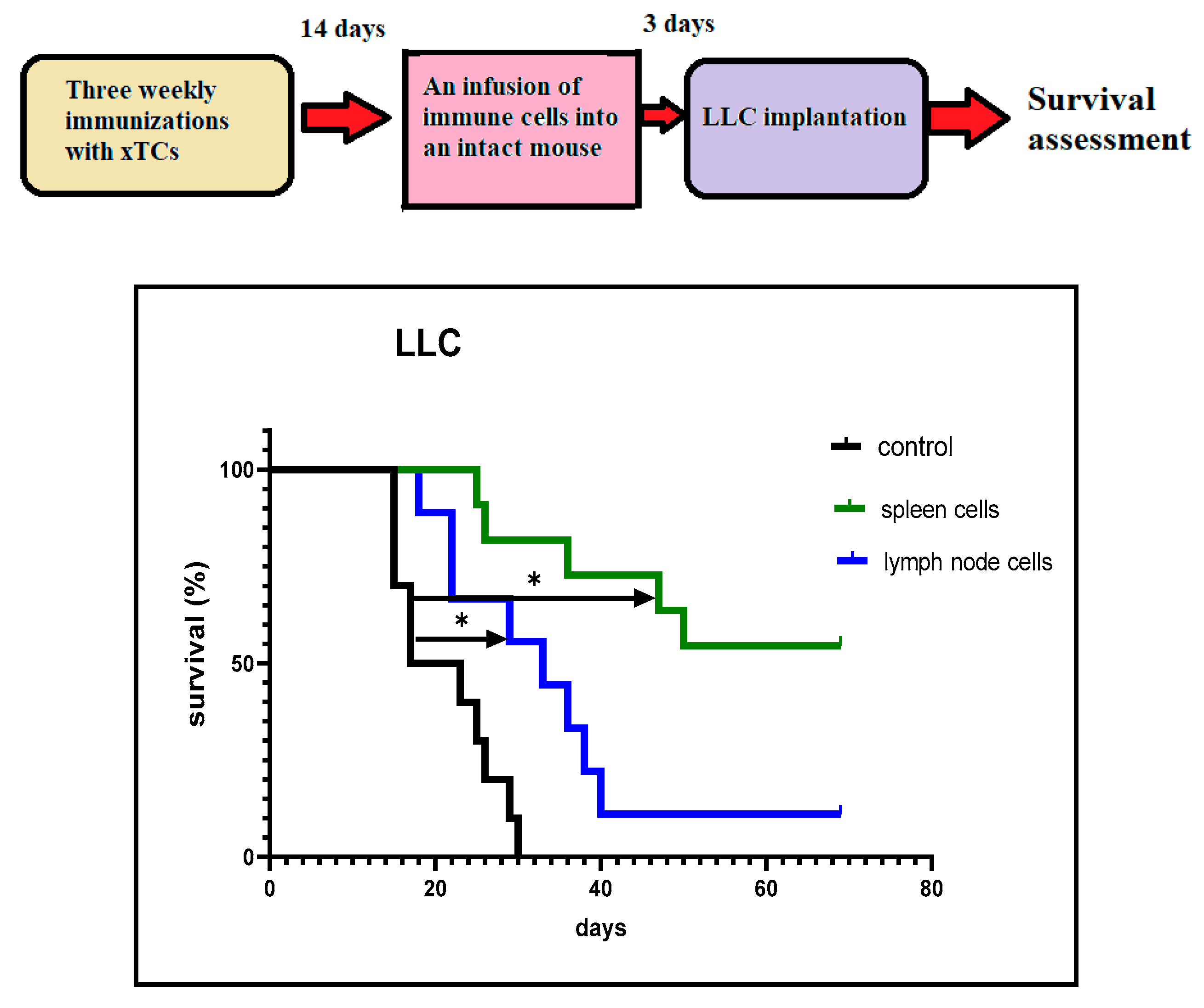

We investigated the possibility of adoptive cell transfer of CTA-induced anti-cancer immunity. In these experiments, spleen or lymph node cells (10

7/mouse) obtained from vaccinated mice 14 days after the last immunisation were injected intravenously into intact mice. Three days after the immune cell injection, LLC cells were implanted, and survival was assessed as described.

Figure 4 shows significantly higher cancer survival rates in mice that received spleen/lymph node cells following implantation of LLC cells, compared to the control mice. Furthermore, this effect was long-lasting, with approximately 20% of mice receiving lymph node cells and 50% of those receiving spleen cells remaining cancer-free by day 70 after implantation. These results led us to focus primarily on the immunological changes occurring in the spleen in response to vaccination, rather than in the lymph nodes.

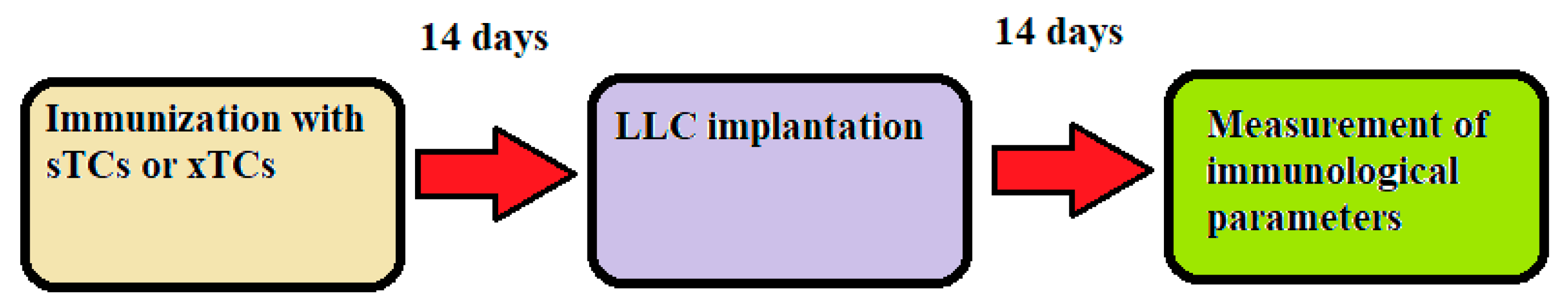

3.3. Immunomodulatory Effects of Tumour Cells During Vaccination

It stands to reason that the primary application of a prophylactic systemic anti-cancer vaccination is to prevent the growth of cancer cells that have either already emerged or are likely to emerge as a result of cancerous mutagenesis. These cancer cells are capable of modulating the immune system in a way that prevents the development of tumour-specific adaptive immune reactivity. A similar situation could occur with tumour cells that remain in the body after a conditionally radical surgical removal of the primary tumour. Therefore, we further developed our experimental model to more closely reflect real-life scenarios in order to assess vaccine-induced changes in immunological parameters occurring in the presence of live tumour cells in the body. A schematic representation of this experimental model is shown in

Figure 5.

Specifically, in these experiments, we used mice immunised three times with sTCs or xTCs Mice were implanted with LLC carcinoma cells (1 x 10⁵ cells/mouse) 14 days after the last immunisation. The content of regulatory T cells and memory T cells was measured in the spleen 14 days following implantation.

Flow cytometry data presented in

Table 1 show that xenogeneic TC vaccination reduced the percentage of regulatory CD4+CD25+FoxP3+ T cells in the spleen, with no effect on central memory CD4+CD44+CD62L+ T cells.

Additionally, the levels of IFN-γ and IL-10 were measured in the blood of TC-immunized mice. Our experiments revealed significantly higher IFN-γ levels in the sera of tumour-bearing mice immunized with xTCs, compared to those observed in mice immunized with sTCs. No significant differences were observed in IL-10 levels between the two groups of mice (

Table 2).

Taken together, the data obtained in this study suggest that vaccination with xenogeneic CTAs may create favourable conditions in the immune system for the development of anti-cancer immune reactivity.

4. Discussion

Surgical removal of the primary tumour remains the cornerstone of cancer treatment. However, this approach often carries an increased risk of disease recurrence. Similarly, certain age-related chronic pathological conditions are associated with a heightened susceptibility to tumorigenic diseases. At present, there are no effective systemic clinical or prophylactic strategies to mitigate the risk of tumourigenesis in patients who do not exhibit overt signs of disease. In this context, our study represents a foundational step towards developing a universal anti-cancer vaccine based on CTAs. A robust scientific framework supports this concept; over 200 different CTA proteins (MAGEA1, MAGE-A3, MAGE-A4, NY-ESO-1, PRAME, CT83, SSX2, etc.) have been identified to date. Notably, CTA-encoding genes play a critical role in organ and tissue formation during early ontogenesis. However, in later developmental stages, these genes become inactive, with high CTA expression persisting only in spermatogenic testicular tissues and the placenta [

3,

4].

We have developed an anti-cancer vaccine prototype derived from spermatogenic ram cells, which contain the full spectrum of CTAs. These CTAs are highly xenogeneic relative to both mice and humans. Growing evidence indicates that xenogeneic vaccines can effectively overcome immune tolerance to weakly immunogenic homologous tumour-associated Ags [

7,

11]. Xenogeneic Ags can serve as an ‘altered self’, possessing enough dissimilarity from self-Ags to elicit an immune response while retaining sufficient similarity to ensure immune system recognition [

11]. There is evidence that xenogeneic T-cell epitopes can bind host MHC molecules with greater affinity than native homologous epitopes, leading to the formation of more stable xenogeneic peptide/MHC complexes. This, in turn, enhances xenogeneic Ag-induced T-cell responses, which are cross-reactive with self-protein-derived Ags [

11,

13]

Although our xenogeneic vaccine was tested in an animal model, it was designed primarily for human application. A key consideration is that all humans possess natural (pre-existing) antibodies that mediate acute rejection of non-primate cells, serving as a major barrier to xenotransplantation. A significant proportion of these antibodies belong to the IgG class and specifically recognise the α-Gal epitope, which is abundantly expressed on glycoproteins and glycolipids of non-primate mammals and New World monkeys. These natural antibodies could enhance the immunogenicity of the vaccine by promoting the opsonisation and internalisation of xenogeneic vaccinal cells by Ag-presenting cells via Fcγ-receptor-mediated mechanisms. This process, in turn, facilitates cross-presentation of tumour-associated Ags to tumour-specific T lymphocytes [

14].

It is well established that individual tumours are highly heterogeneous, consisting of antigenically diverse cancer cell subpopulations. Consequently, mono-antigenic or oligo-antigenic vaccination strategies may only target a subset of tumour cells while inadvertently selecting for Ag-negative variants with a growth advantage. We argue that only polyantigenic immunization can generate immune responses against a broad spectrum of tumour-associated Ags, thereby counteracting the intrinsic antigenic variability of tumours. This variability arises from the genetic instability of the tumour genome and its continuous interactions with the immune system. Vaccine-induced anti-cancer immunity would function optimally when the emergence of new tumour cell clones with altered antigenic profiles is counterbalanced by pre-existing polyclonal vaccine-induced immune reactivity. Consistent with this principle, our xenogeneic polyantigenic vaccine contains the full repertoire of CTAs, promoting robust immune responses against cancer cell subpopulations expressing various CTAs.

Our vaccine falls into the category of cellular immunotherapeutic vaccines, engaging critical Ag-processing and presentation pathways. The uptake of vaccine cells by APCs facilitates Ag cross-presentation to CD4+ and CD8+ T cells, thereby generating durable CD8+ T-cell memory with CD4+ T-cell help. Antigenic molecules presented on cell surfaces or within cellular compartments are generally more immunogenic than their soluble counterparts, as the immune system is evolutionarily adapted to recognise and eliminate infected or malignant cells rather than harmless soluble Ags [

15,

16]

Published data suggest that vaccinal cells can promote dendritic cell (DC) maturation, possibly due to the rapid degradation of cellular RNA and DNA into purine bases, which are subsequently converted into uric acid. Uric acid, as a key endogenous danger signal, drives DC activation and enhances Ag presentation [

17,

18].

In our experiments, vaccination of mice with x-TCs induced effective anti-cancer immunity that suppressed tumour development for at least six months. Moreover, this immunity could be adoptively transferred to naïve animals using a relatively small number of immune cells from vaccinated mice. Most anti-cancer immune cells were localised in the spleen rather than lymph nodes, reinforcing the spleen’s pivotal role in regulating immune responses to tumour-associated Ags [

19].

Prophylactic xTC vaccination lessened regulatory T cell prevalence, usually suppressing cytotoxic responses. This vaccine increased serum IFN-γ, a cytokine crucial for both adaptive and innate anti-cancer immunity [

20]. These data indicate that vaccination with xenogeneic CTAs may favor different antitumor immune mechanisms.

Theoretically, breaking immune tolerance through polyantigenic xenogeneic vaccination could increase the risk of autoimmune reactions. However, our vaccine is derived from spermatogenic ram tissue, which lacks tissue-specific Ags, reducing the likelihood of eliciting autoimmunity. Our observations confirm this assumption, as vaccinated mice exhibited no signs of autoimmune disorders during the six-month observation period.

Spermatogenic tissue offers a key advantage over tumour cell lines due to its genetic stability, which is maintained by natural mechanisms essential for species survival. This stability ensures that vaccine preparations derived from normal spermatogenic tissue can be standardised according to the most stringent immunobiological requirements.

Despite its promise, our study has certain limitations. Notably, our xenogeneic cellular vaccine did not improve survival rates in tumour-bearing mice when administered therapeutically (i.e., after tumour cell implantation). This is likely due to the aggressive nature of the implanted B16 melanoma and LLC carcinoma, which rapidly led to host mortality before the immune response could fully develop. Prophylactic vaccination with xenogeneic CTAs elicited strong anti-cancer effects against LLC carcinoma and a statistically significant, albeit weaker, response against B16 melanoma. This discrepancy may be explained by the high intra-tumoral transcriptional heterogeneity of CTA expression in melanoma [

21]. These findings suggest that the efficacy of xenogeneic CTA vaccine-induced immunity may vary depending on tumour type. However, various immunotherapeutic strategies—such as immunoadjuvants, cytokines, dendritic cells, and immune checkpoint inhibitors—could be employed to enhance the prophylactic and therapeutic potential of CTA-based vaccines against different cancers. These approaches are currently under investigation, and the results will be reported in due course.

5. Conclusions

Xenogeneic (but not syngeneic) cancer/testis antigens can induce stable anti-cancer immunity in mice. Owing to the high levels of expression characteristic of cancer-testicular genes in most tumours, we envisage that a vaccine based on xenogeneic CTAs could potentially induce long-lasting anti-cancer immunity capable of counteracting the expansion of any tumour cells, regardless of their histogenesis. Therefore, a future adaptation of our lab's cellular vaccine prototype could potentially be a universal anti-cancer prophylactic.

Author Contributions

V.I.S. and A.B.D. made equal contributions to this study: conceptualization, methodology, project administration, data interpretation, supervision, writing—original draft and investigation. A.D.: investigation. A.A.v.D.: writing—review and editing. G.V.S. statistical analysis, data interpretation, writing—review. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Data sharing requires no permission.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

References

- Seledtsov VI, von Delwig A. Clinically feasible and prospective immunotherapeutic interventions in multidirectional comprehensive treatment of cancer. Expert Opin Biol Ther. 2021 Mar;21(3):323-342. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Simpson AJ, Caballero OL, Jungbluth A, Chen YT, Old LJ. Cancer/testis antigens, gametogenesis and cancer. Nat Rev Cancer. 2005 Aug;5(8):615-25. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salmaninejad A, Zamani MR, Pourvahedi M, Golchehre Z, Hosseini Bereshneh A, Rezaei N. Cancer/testis antigens: expression, regulation, tumor invasion, and use in immunotherapy of cancers. Immunol Invest. 2016 Oct;45(7):619-40. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gordeeva O. Cancer-testis antigens: unique cancer stem cell biomarkers and targets for cancer therapy. Seminars in cancer biology. 2018. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Almeida LG, Sakabe NJ, deOliveira AR, Silva MC, Mundstein AS, Cohen T, Chen YT, Chua R, Gurung S, Gnjatic S, Jungbluth AA, Caballero OL, Bairoch A, Kiesler E, White SL, Simpson AJ, Old LJ, Camargo AA, Vasconcelos AT. CTdatabase: a knowledge-base of high-throughput and curated data on cancer-testis antigens. Nucleic Acids Res. 2009 Jan;37(Database issue):D816-9. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Ren S, Zhang Z, Li M, Wang D, Guo R, Fang X, Chen F. Cancer testis antigen subfamilies: Attractive targets for therapeutic vaccine (Review). Int J Oncol. 2023 Jun;62(6):71. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Seledtsov VI, Goncharov AG, Seledtsova GV. Multiple-purpose immunotherapy for cancer. Biomed Pharmacother. 2015 Dec;76:24-9. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang CP, Yang CY, Shyr CR. Utilizing xenogeneic cells as a therapeutic agent for treating diseases. Cell Transplant. 2021 Jan-Dec;30:9636897211011995. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Huang CP, Lu HL, Shyr CR. Anti-tumor activity of intratumoral xenogeneic urothelial cell monotherapy or in combination with chemotherapy in syngeneic murine models of bladder cancer. Am J Cancer Res. 2023 Jun 15;13(6):2285-2306. [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Aurisicchio L, Roscilli G, Marra E, Luberto L, Mancini R, La Monica N, Ciliberto G. Superior immunologic and therapeutic efficacy of a xenogeneic genetic cancer vaccine targeting carcinoembryonic human antigen. Hum Gene Ther. 2015 Jun;26(6):386-98. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Strioga MM, Darinskas A, Pasukoniene V, Mlynska A, Ostapenko V, Schijns V. Xenogeneic therapeutic cancer vaccines as breakers of immune tolerance for clinical application: to use or not to use? Vaccine. 2014 Jul 7;32(32):4015-24. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seledtsov VI, Goncharov AG, Seledtsova GV. Clinically feasible approaches to potentiating cancer cell-based immunotherapies. Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2015;11(4):851-69. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Overwijk WW, Tsung A, Irvine KR, Parkhurst MR, Goletz TJ, Tsung K, Carroll MW, Liu C, Moss B, Rosenberg SA, Restifo NP. gp100/pmel 17 is a murine tumor rejection antigen: induction of "self"-reactive, tumoricidal T cells using high-affinity, altered peptide ligand. J Exp Med. 1998 Jul 20;188(2):277-86. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Galili U. Interaction of the natural anti-Gal antibody with alpha-galactosyl epitopes: a major obstacle for xenotransplantation in humans. Immunol Today. 1993 Oct;14(10):480-2. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ward S, Casey D, Labarthe MC, Whelan M, Dalgleish A, Pandha H, Todryk S. Immunotherapeutic potential of whole tumour cells. Cancer Immunol Immunother. 2002 Sep;51(7):351-7. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Chiang CL, Kandalaft LE, Coukos G. Adjuvants for enhancing the immunogenicity of whole tumor cell vaccines. Int Rev Immunol. 2011 Apr-Jun;30(2-3):150-82. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sauter B, Albert ML, Francisco L, Larsson M, Somersan S, Bhardwaj N. Consequences of cell death: exposure to necrotic tumor cells, but not primary tissue cells or apoptotic cells, induces the maturation of immunostimulatory dendritic cells. J Exp Med. 2000 Feb 7;191(3):423-34. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Hu DE, Moore AM, Thomsen LL, Brindle KM. Uric acid promotes tumor immune rejection. Cancer Res. 2004 Aug 1;64(15):5059-62. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ugel S, Peranzoni E, Desantis G, Chioda M, Walter S, Weinschenk T, Ochando JC, Cabrelle A, Mandruzzato S, Bronte V. Immune tolerance to tumor antigens occurs in a specialized environment of the spleen. Cell Rep. 2012 Sep 27;2(3):628-39. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seledtsov VI, Darinskas A, Von Delwig A, Seledtsova GV. Inflammation control and immunotherapeutic strategies in comprehensive cancer treatment. Metabolites. 2023 Jan 13;13(1):123. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Traynor S, Jakobsen MK, Green TM, Komic H, Palarasah Y, Pedersen CB, Ditzel HJ, Thoren FB, Guldberg P, Gjerstorff MF. Single-cell sequencing unveils extensive intratumoral heterogeneity of cancer/testis antigen expression in melanoma and lung cancer. J Immunother Cancer. 2024 Jun 17;12(6):e008759. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).