Submitted:

31 March 2025

Posted:

01 April 2025

You are already at the latest version

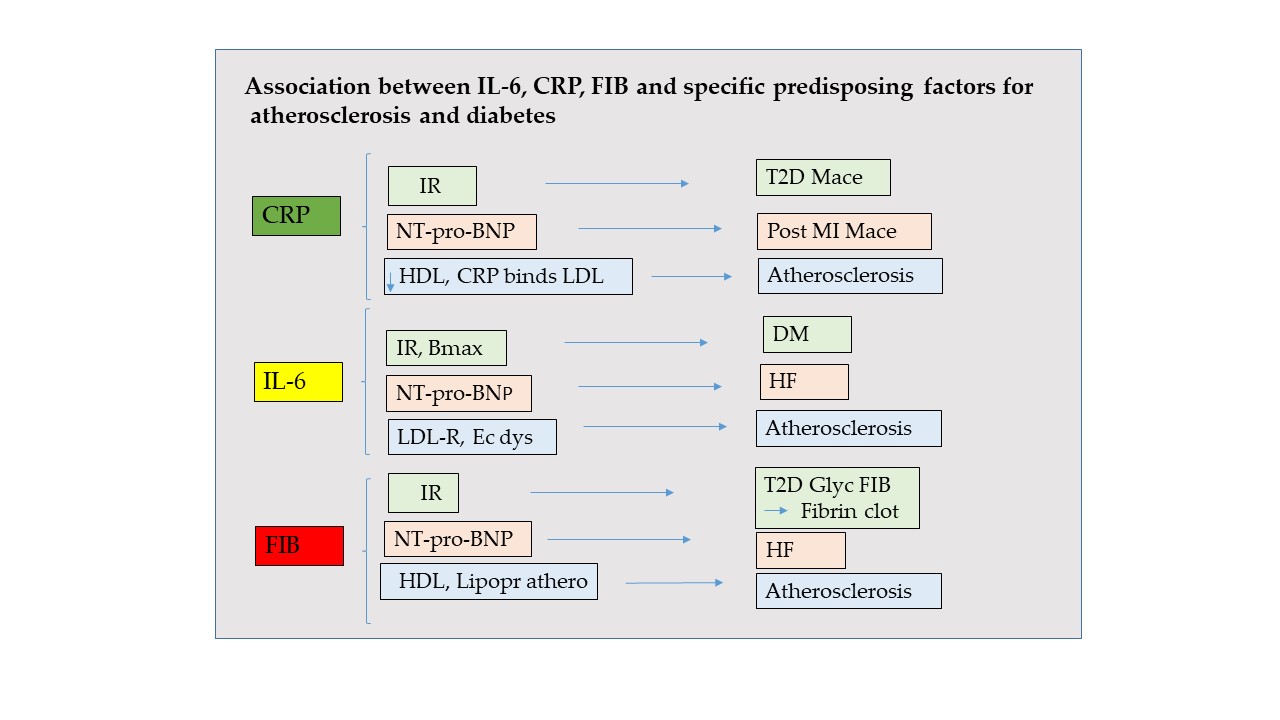

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. CRP

2.1. CRP and Vascular Injury

2.2. CRP and Cardiovascular Diseases

2.3. CRP and NT-pro-BNP

2.4. CRP, Glycemia and Insulin Resistance

2.5. CRP, LDL and HDL

3. IL-6

3.1. IL-6 and Vascular Injury

3.2. IL-6 and Cardiovascular Disease

3.3. IL-6 and NT-pro-BNP

3.4. IL-6, Glycemia and Insulin Resistance

3.5. IL-6, LDL and HDL

4. FIB

4.1. FIB and Vascular Injury

4.2. FIB and Cardiovascular Disease

4.3. FIB and NT-pro-BNP

4.4. FIB, Glycemia and Insulin Resistance

4.5. FIB, LDL and HDL

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

References

- Libby, P. Inflammation in atherosclerosis. Nature 2002, 420, 868–874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rader, D.J. Inflammatory markers of coronary risk. N. Engl. J. Med. 2000, 343, 1179–1182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morrow, D.A.; Braunwald, E. Future of biomarkers in acute coronary syndromes: moving toward a multimarker strategy. Circulation 2003, 108, 250–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Velikova, T.V.; Kabakchieva, P.P.; Assyov, Y.S.; Georgiev, T.А. Targeting Inflammatory Cytokines to Improve Type 2 Diabetes Control. Biomed. Res. Int. 2021, 7297419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Markousis-Mavrogenis, G.; Tromp, J.; Ouwerkerk, W.; Devalaraja, M.; Anker, S.D.; Cleland, J.G.; Dickstein, K.; Filippatos, G.S.; van der Harst, P.; Lang, C.C.; et al. The clinical significance of interleukin-6 in heart failure: results from the BIOSTAT-CHF study. Eur. J. Heart Fail. 2019, 21, 965–973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marchio, P.; Guerra-Ojeda, S.; Vila, J.M.; Aldasoro, M.; Victor, V.M.; Mauricio, M.D. Targeting Early Atherosclerosis: A Focus on Oxidative Stress and Inflammation. Oxid. Med. Cell Longev. 2019, 8563845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, P.; Cui, Z.Y.; Huang, X.F.; Zhang, D.D.; Guo, R.J.; Han, M. Inflammation and atherosclerosis: signaling pathways and therapeutic intervention. Signal. Transduct. Target Ther. 2022, 7, 131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malekmohammad, K.; Bezsonov, E.E.; Rafieian-Kopaei, M. Role of Lipid Accumulation and Inflammation in Atherosclerosis: Focus on Molecular and Cellular Mechanisms. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 2021, 8, 707529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rafieian-Kopaei, M.; Setorki, M.; Doudi, M.; Baradaran, A.; Nasri, H. Atherosclerosis: process, indicators, risk factors and new hopes. Int. J. Prev. Med. 2014, 5, 927–946. [Google Scholar]

- Vergeer, M.; Holleboom, A.G.; Kastelein, J.J.; Kuivenhoven, J.A. The HDL hypothesis: does high-density lipoprotein protect from atherosclerosis? J. Lipid Res. 2010, 51, 2058–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barter, P.J.; Nicholls, S.; Rye, K.A.; Anantharamaiah, G.M.; Navab, M.; and Fogelman, A.M. Anti-inflammatory Properties of HDL. Circulation Research 2004, 95, 764–772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fotakis, P.; Kothari, V.; Thomas, D.G.; Westerterp, M.; Molusky, M.M.; Altin, E.; Abramowicz, S.; Wang, N.; He, Y.; Heinecke, J.W.; Bornfeldt, K.E.; Tall, A.R. Anti-Inflammatory Effects of HDL (High-Density Lipoprotein) in macrophages predominate over proinflammatory effects in atherosclerotic plaques. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2019, 39, e253–e272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pepys, M.B.; Hirschfield, G.M. C-reactive protein: a critical update. J. Clin. Invest. 2003, 111, 1805–1812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lelubre C, Anselin S, Zouaoui Boudjeltia K, Biston P, Piagnerelli, M. Interpretation of C-reactive protein concentrations in critically ill patients. Biomed. Res. Int. 2013, 124021. [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Potempa, L.A.; El Kebir, D.; Filep, J.G. C-reactive protein and inflammation: conformational changes affect function. Biol. Chem. 2015, 396, 1181–1197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pepys, M.B. The Pentraxins 1975-2018: Serendipity, Diagnostics and Drugs. Front. Immunol. 2018, 9, 2382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McFadyen, J.D.; Kiefer, J.; Braig, D.; Loseff-Silver, J.; Potempa, L.A.; Eisenhardt, S.U.; Peter, K. Dissociation of C-Reactive Protein Localizes and Amplifies Inflammation: Evidence for a Direct Biological Role of C-Reactive Protein and Its Conformational Changes. Front. Immunol. 2018, 9, 1351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, S.R.; Wu, Y.; Zhu, L.; Potempa, L.A.; Sheng, F.L.; Lu, W.; Zhao, J. Cell membranes and liposomes dissociate C-reactive protein (CRP) to form a new, biologically active structural intermediate: mCRP(m). FASEB J. 2007, 21, 284–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braig, D.; Nero, T.L.; Koch, H.G.; Kaiser, B.; Wang, X.; Thiele, J.R.; Morton, C.J.; Zeller, J.; Kiefer, J.; Potempa, L.A.; et al. Transitional changes in the CRP structure lead to the exposure of proinflammatory binding sites. Nat. Commun. 2017, 8, 14188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melnikov, I.; Kozlov, S.; Saburova, O.; Avtaeva, Y.; Guria, K.; Gabbasov, Z. Monomeric C-Reactive Protein in Atherosclerotic Cardiovascular Disease: Advances and Perspectives. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 2079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du Clos, T.W. C-reactive protein as a regulator of autoimmunity and inflammation. Arthritis. Rheum. 2003, 48, 1475–1477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eisenhardt, S.U.; Habersberger, J.; Murphy, A.; Chen, Y.C.; Woollard, K.J.; Bassler, N.; Qian, H.; von Zur Muhlen, C.; Hagemeyer, C.E.; et al. Dissociation of pentameric to monomeric C-reactive protein on activated platelets localizes inflammation to atherosclerotic plaques. Circ. Res. 2009, 105, 128–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thiele, J.R.; Habersberger, J.; Braig, D.; Schmidt, Y.; Goerendt, K.; Maurer, V.; Bannasch, H.; Scheichl, A.; Woollard, K.J.; von Dobschütz, E.; et al. Dissociation of pentameric to monomeric C-reactive protein localizes and aggravates inflammation: in vivo proof of a powerful proinflammatory mechanism and a new anti-inflammatory strategy. Circulation 2014, 130, 35–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Volanakis, J.E.; Wirtz, K.W. Interaction of C-reactive protein with artificial phosphatidylcholine bilayers. Nature 1979, 281, 155–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pearson, T.A.; Mensah, G.A.; Alexander, R.W.; Anderson, J.L.; Cannon, R.O.; Criqui, M.; Fadl, Y.Y.; Fortmann, S.P.; Hong, Y.; Myers, G.L.; et al. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; American Heart Association. Markers of inflammation and cardiovascular disease: application to clinical and public health practice: A statement for healthcare professionals from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and the American Heart Association. Circulation 2003, 107, 499–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pasceri, V.; Cheng, J.S.; Willerson, J.T.; Yeh, E.T. Modulation of C-reactive protein-mediated monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 induction in human endothelial cells by anti-atherosclerosis drugs. Circulation 2001, 103, 2531–1234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pasceri, V.; Willerson, J.T.; Yeh, E.T. Direct proinflammatory effect of C-reactive protein on human endothelial cells. Circulation 2000, 102, 2165–2168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Venugopal, S.K.; Devaraj, S.; Yuhanna, I.; Shaul, P.; Jialal, I. Demonstration that C-reactive protein decreases eNOS expression and bioactivity in human aortic endothelial cells. Circulation 2002, 106, 1439–1441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grad, E.; Danenberg, H.D. C-reactive protein and atherothrombosis: Cause or effect? Blood Rev. 2013, 27, 23–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fichtlscherer, S.; Rosenberger, G.; Walter, D.H.; Breuer, S.; Dimmeler, S.; Zeiher, A.M. Elevated C-reactive protein levels and impaired endothelial vasoreactivity in patients with coronary artery disease. Circulation 2000, 102, 1000–1006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verma, S.; Wang, C.H.; Li, S.H.; Dumont, A.S.; Fedak, P.W.; Badiwala, M.V.; Dhillon, B.; Weisel, R.D.; Li, R.K.; Mickle, D.A.; et al. A self-fulfilling prophecy: C-reactive protein attenuates nitric oxide production and inhibits angiogenesis. Circulation 2002, 106, 913–919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nabata, A.; Kuroki, M.; Ueba, H.; Hashimoto, S.; Umemoto, T.; Wada, H.; Yasu, T.; Saito, M.; Momomura, S.I.; Kawakami, M. C-reactive protein induces endothelial cell apoptosis and matrix metalloproteinase-9 production in human mononuclear cells: Implications for the destabilization of atherosclerotic plaque. Atherosclerosis 2008, 196, 129–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hein, T.W.; Qamirani, E.; Ren, Y.; Kuo, L. C-reactive protein impairs coronary arteriolar dilation to prostacyclin synthase activation: role of peroxynitrite. J. Mol. Cell Cardiol. 2009, 47, 196–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, Y.; Fish, P.M.; Strawn, T.L.; Lohman, A.W.; Wu, J.; Szalai, A.J.; Fay, W.P. C-reactive protein induces expression of tissue factor and plasminogen activator inhibitor-1 and promotes fibrin accumulation in vein grafts. J. Thromb. Haemost. 2014, 12, 1667–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bisoendial, R.J.; Kastelein, J.J.; Levels, J.H.; Zwaginga, J.J.; van den Bogaard, B.; Reitsma, P.H.; Meijers, J.C.; Hartman, D.; Levi, M.; Stroes, E.S. Activation of inflammation and coagulation after infusion of C-reactive protein in humans. Circ. Res. 2005, 96, 714–716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luan, Y.Y.; Yao, Y.M. The Clinical Significance and Potential Role of C-reactive Protein in Chronic Inflammatory and Neurodegenerative Diseases. Front. Immunol. 2018, 9, 1302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arroyo-Espliguero, R.; Viana-Llamas, M.C.; Silva-Obregón, A.; Avanzas, P. The Role of C-reactive Protein in Patient Risk Stratification and Treatment. Eur. Cardiol. 2021, 16, e28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kao, P.C.; Shiesh, S.C.; Wu, T.J. Serum C-reactive protein as a marker for wellness assessment. Ann. Clin. Lab. Sci. 2006, 36, 163–169. [Google Scholar]

- Koenig, W.; Sund, M.; Fröhlich, M.; Fischer, H.G.; Löwel, H.; Döring, A.; Hutchinson, WL.; Pepys, MB. C-reactive protein, a sensitive marker of inflammation, predicts future risk of coronary heart disease in initially healthy middle-aged men: results from the MONICA (Monitoring Trends and Determinants in Cardiovascular Disease) Augsburg Cohort Study, 1984 to 1992. Circulation 1999, 99, 237–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Currie, C.J.; Poole, C.D.; Conway, P. Evaluation of the association between the first observation and the longitudinal change in C-reactive protein, and all-cause mortality. Heart 2008, 94, 457–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarwar, N.; Gao, P.; Seshasai, S.R.; Gobin, R.; Kaptoge, S.; Di Angelantonio, E.; Ingelsson, E.; Lawlor, D.A.; Selvin, E.; Stampfer, M.; e, al. Diabetes mellitus, fasting blood glucose concentration, and risk of vascular disease: a collaborative meta-analysis of 102 prospective studies. Lancet 2010, 375, 2215–2222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, P.H.; Lu, T.M.; Wu, T.C.; Lin, F.Y.; Chen, Y.H.; Chen, J.W.; Lin, S.J. Usefulness of combined high-sensitive C-reactive protein and N-terminal-probrain natriuretic peptide for predicting cardiovascular events in patients with suspected coronary artery disease. Coron. Artery. Dis. 2008, 19, 187–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.; Yang, D.H.; Park, Y.; Han, J.; Lee, H.; Kang, H.; Park, H.S.; Cho, Y.; Chae, S.C.; Jun, J.E.; et al. Incremental prognostic value of C-reactive protein and N-terminal proB-type natriuretic peptide in acute coronary syndrome. Circ. J. 2006, 70, 1379–1384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rymer, J.A.; Newby, L.K. Failure to Launch: Targeting Inflammation in Acute Coronary Syndromes. JACC Basic Transl. Sci. 2017, 2, 484–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goetze, J.P.; Bruneau, B.G.; Ramos, H.R.; Ogawa, T.; de Bold, M.K.; de Bold, A.J. Cardiac natriuretic peptides. Nat. Rev. Cardiol. 2020, 17, 698–717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, K.P.; Zhang, H.Y.; Xu, X.D.; Ming, Y.; Li, T.J.; Song, S.T. Recombinant human brain natriuretic peptide attenuates myocardial ischemia-reperfusion injury by inhibiting CD4(+) T cell proliferation via PI3K/AKT/mTOR pathway activation. Cardiovasc. Ther. 2020, 2020, 1389312–10.1155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, M.Y.; Neely, M.L.; Roe, M.T.; Goodman, S.G.; Erlinge, D.; Cornel, J.H.; Winters, K.J.; Jakubowski, J.A.; Zhou, C.; Fox, K.A.A.; et al. Temporal biomarker profiling reveals longitudinal changes in risk of death or myocardial infarction in non-ST-segment elevation acute coronary syndrome. Clin. Chem. 2017, 63, 1214–1226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, Y.X.; Li, S.; Liu, H.H.; Zhang, M.; Guo, Y.L.; Wu, N.Q.; Zhu, C.G.; Dong, Q.; Sun, J.; Dou, K.F.; et al. Prognostic Value of N-Terminal Pro-B-Type Natriuretic Peptide and High-Sensitivity C-Reactive Protein in Patients With Previous Myocardial Infarction. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 2022, 9, 797297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freeman, D.J.; Norrie, J.; Caslake, M.J.; Gaw, A.; Ford, I.; Lowe, G.D.O.; O’Reilly, D.S.J.; Packard, C.J.; Sattar, N. C-reactive protein is an independent predictor of risk for the development of diabetes in the West of Scotland Coronary Prevention Study. Diabetes 2002, 51, 1596–1600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sproston, N.R.; and Ashworth, J.J. Role of C-reactive protein at sites of inflammation and infection Frontiers in Immunology 2018, 9, 754–754. [CrossRef]

- Stanimirovic, J.; Radovanovic, J.; Banjac, K.; Obradovic, M.; Essack, M.; Zafirovic, S.; Gluvic, Z.; Gojobori, T.; Isenovic, E.R. Role of C-Reactive Protein in Diabetic Inflammation. Mediators Inflamm. 2022, 17, 3706508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gelaye, B.; Revilla, L.; Lopez, T.; Suarez, L.; Sanchez, S.E.; Hevner, K.; Fitzpatrick, A.L.; Williams, M.A. Association between insulin resistance and c-reactive protein among Peruvian adults. Diabetol. Metab. Syndr. 2010, 2, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, G.R.; Choi, D.W.; Nam, C.M.; Jang, S.I.; Park, E.C. Synergistic association of high-sensitivity C-reactive protein and body mass index with insulin resistance in non-diabetic adults. Sci. Rep. 2020, 18417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Uemura, H.; Katsuura-Kamano, S.; Yamaguchi, M.; Bahari, T.; Ishizu, M.; Fujioka, M.; Arisawa, K. Relationships of serum high-sensitivity C-reactive protein and body size with insulin resistance in a Japanese cohort. PLoS One 2017, 12, e0178672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tian, R.; Tian, M.; Wang, L.; Qian, H.; Zhang, S.; Pang, H.; Liu, Z.; Fang, L.; Shen, Z. C-reactive protein for predicting cardiovascular and all-cause mortality in type 2 diabetic patients: A meta-analysis. Cytokine 2019, 117, 59–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, M.; Qiu, S.; He, Y.; Li, L.; Wu, T.; Ding, N.; Li, F.; Zhao, A.Z.; Yang, G. Genetic ablation of C-reactive protein gene confers resistance to obesity and insulin resistance in rats. Diabetologia 2021, 64, 1169–1183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fukuchi, Y.; Miura, Y.; Nabeno, Y.; Kato, Y.; Osawa, T.; Naito, M. Immunohistochemical detection of oxidative stress biomarkers, dityrosine and N(epsilon)-(hexanoyl)lysine, and C-reactive protein in rabbit atherosclerotic lesions. J. Atheroscler. Thromb. 2008, 15, 185–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jarva, H.; Jokiranta, T.S.; Hellwage, J.; Zipfel, P.F.; Meri, S. Regulation of complement activation by C-reactive protein:Targeting the complement inhibitory activity of factor H by an interaction with short consensus repeat domains 7 and 8–11. J. Immunol. 1999, 163, 3957–3962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kanmani, S.; Kwon, M.; Shin, M.K.; Kim, M.K. Association of C-Reactive Protein with Risk of Developing Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus, and Role of Obesity and Hypertension: A Large Population-Based Korean Cohort Study. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 4573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.X.; Cliff, W.J.; Schoefl, G.I.; Higgins, G. Coronary C-reactive protein distribution: its relation to development of atherosclerosis. Atherosclerosis 1999, 145, 375–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Danesh, J.; Wheeler, J.G.; Hirschfield, G.M.; Eda, S.; Eiriksdottir, G.; Rumley, A.; Lowe, G.D.; Pepys, M.B.; Gudnason, V. C-reactive protein and other circulating markers of inflammation in the prediction of coronary heart disease. N. Engl. J. Med. 2004, 350, 1387–1397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ridker, P.M.; Rifai, N.; Cook, N.R.; Bradwin, G.; Buring, J.E. Non-HDL cholesterol, apolipoproteins A-I and B100, standard lipid measures, lipid ratios, and CRP as risk factors for cardiovascular disease in women. JAMA 2005, 294, 326–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ridker, P.M.; Rifai, N.; Rose, L.; Buring, J.E.; Cook, N.R. Comparison of C-reactive protein and low-density lipoprotein cholesterol levels in the prediction of first cardiovascular events. N. Engl. J. Med. 2002, 347, 1557–1565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwang, Y.C.; Morrow, D.A.; Cannon, C.P.; Liu, Y.; Bergenstal, R.; Heller, S.; Mehta, C.; Cushman, W.; Bakris, GL.; Zannad, F.; et al. High-sensitivity C-reactive protein, low-density lipoprotein cholesterol and cardiovascular outcomes in patients with type 2 diabetes in the EXAMINE (Examination of Cardiovascular Outcomes with Alogliptin versus Standard of Care) trial. Diabetes Obes. Metab. 2018, 20, 654–659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bian, F.; Yang, X.; Zhou, F.; Wu, P.H.; Xing, S.; Xu, G.; Li, W.; Chi, J.; Ouyang, C.; Zhang, Y.; et al. C-reactive protein promotes atherosclerosis by increasing LDL transcytosis across endothelial cells. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2014, 171, 2671–2684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Roumeliotis, N.; Sawamura, T.; Renier, G. C-reactive protein enhances LOX-1 expression in human aortic endothelial cells: relevance of LOX-1 to C-reactive protein-induced endothelial dysfunction. Circ. Res. 2004, 95, 877–883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feingold, K.R.; Grunfeld, C. The Effect of Inflammation and Infection on Lipids and Lipoproteins. In Feingold, K.R.; Anawalt, B., Ed.; Blackman, M.R. eds. Endotext South Dartmouth (MA): MDText.com, Inc.; March 7, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Kosmas, C.E.; Martinez, I.; Sourlas, A.; Bouza, K.V.; Campos, F.N.; Torres, V.; Montan, P.D.; Guzman, E. High-density lipoprotein (HDL) functionality and its relevance to atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease. Drugs. Context 2018, 7, 212525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Ma, H. Associations of the hs-CRP/HDL-C ratio with cardiovascular disease among US adults: Evidence from NHANES 2015-2018. Nutr. Metab. Cardiovasc. Dis. 2024, 103814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hirano, T.; Taga, T.; Yamasaki, K.; Matsuda, T.; Yasukawa, K.; Hirata, Y.; Yawata, H.; Tanabe, O.; Akira, S.; Kishimoto, T. Molecular cloning of the cDNAs for interleukin-6/B cell stimulatory factor 2 and its receptor. Ann. N Y. Acad. Sci. 1989, 557, 167–178, discussion 178–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rose-John, S. Interleukin-6 Family Cytokines. Cold. Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol. 2018, 10, a028415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmidt-Arras, D.; Rose-John, S. IL-6 pathway in the liver: From physiopathology to therapy. J. Hepatol. 2016, 64, 1403–1415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanaka, T.; Narazaki, M.; Kishimoto, T. IL-6 in inflammation, immunity, and disease. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol. 2014, 6, a016295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mantovani, A.; Bussolino, F.; Dejana, E. Cytokine regulation of endothelial cell function. FASEB J. 1992, 6, 2591–2599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rus, H.G.; Vlaicu, R.; Niculescu, F. Interleukin-6 and interleukin-8 protein and gene expression in human arterial atherosclerotic wall. Atherosclerosis, 1996, 127, 263–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, J.H.; Luo, M.Y.; Liang, N.; et al. Interleukin-6: A Novel Target for Cardio-Cerebrovascular Diseases. Front. Pharmacol. 2021, C12, 745061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Puzianowska-Kuźnicka, M.; Owczarz, M.; Wieczorowska-Tobis, K.; Nadrowski, P.; Chudek, J.; Slusarczyk, P.; Skalska, A.; Jonas, M.; Franek, E.; Mossakowska, M. Interleukin-6 and C-reactive protein, successful aging, and mortality: the Pol Senior study. Immun. Ageing 2016, 13, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbatecola, A.M.; Ferrucci, L.; Grella, R.; Bandinelli, S.; Bonafe, M.; Barbieri, M.; Corsi, A.M.; Lauretani, F.; Franceschi, C.; Paolisso, G. Diverse effect of inflammatory markers on insulin resistance and insulin-resistance syndrome in the elderly. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 2004, 52, 399–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feng, Y.; Ye, D.; Wang, Z.; Pan, H.; Lu, X.; Wang, M.; Xu, Y.; Yu, J.; Zhang, J.; Zhao, M.; Xu, S.; Pan, W.; Yin, Z.; Ye, J.; Wan, J. The Role of Interleukin-6 Family Members in Cardiovascular Diseases. Front. Cardiovasc. Med 2022, 9, 818890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lubrano, V.; Cocci, F.; Battaglia, D.; Papa, A.; Marraccini, P.; Zucchelli, G.C. Usefulness of high-sensitivity IL-6 measurement for clinical characterization of patients with coronary artery disease. J. Clin. Lab. Anal. 2005, 19, 110–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geiger, T.; Andus, T.; Klapproth, J.; Hirano, T.; Kishimoto, T.; Heinrich, P.C. Induction of rat acute-phase proteins by interleukin 6 in vivo. Eur. J. Immunol. 1988, 18, 717–721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heinrich, P.C.; Behrmann, I.; Muller-Newen, G.; Schaper, F.; Graeve, L. Interleukin-6-type cytokine signalling through the gp130/Jak/STAT pathway. Biochem. J. 1998, 334, 297–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carey, L.; Febbraio, M.A. Interleukin-6 and insulin sensitivity: friend or foe? Diabetologia 2004, 47, 1135–1142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Starr, R.; Willson, T.A.; Viney, E.M.; Rayner, J.R.; Jenkins, B.J.; Gonda, T.J.; Alexander, W.S.; Metcalf, D.; Nicola, N.A.; Hilton, D.J. A family of cytokine-inducible inhibitors of signalling. Nature 1997, 387, 917–921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tanaka, T.; Narazaki, M.; Kishimoto, T. Interleukin (IL-6) Immunotherapy. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect Biol. 2018, 10, a028456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viedt, C.; Vogel, J.; Athanasiou, T.; et al. Monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 induces proliferation and interleukin-6 production in human smooth muscle cells by differential activation of nuclear factor-kappaB and activator protein-1. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2002, 22, 914–920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Herrington, W.; Lacey, B.; Sherliker, P.; et al. Epidemiology of Atherosclerosis and the Potential to Reduce the Global Burden of Atherothrombotic Disease Circ. Res. 2016, 118, 535–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kerr, R.; Stirling, D.; Ludlam, C.A. Interleukin 6 and haemostasis. Br. J. Haematol. 2001, 115, 3–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cesari, M.; Penninx, B.W.; Newman, AB; et al. Inflammatory markers and cardiovascular disease (The Health, Aging and Body Composition [Health ABC] Study). Am. J. Cardiol. 2003, 92, 522–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takeda, N.; Manabe, I.; Shindo, T.; et al. Synthetic retinoid Am80 reduces scavenger receptor expression and atherosclerosis in mice by inhibiting IL-6. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2006, 26, 1177–1183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zamani, P.; Schwartz, G.G.; Olsson, A.G.; Rifai, N.; Bao, W.; Libby, P.; Ganz, P.; Kinlay, S. Inflammatory Biomarkers, Death, and Recurrent Nonfatal Coronary Events after an Acute Coronary Syndrome in the MIRACL Study. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 2013, 2, e003103–10.1161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindmark, E.; Diderholm, E.; Wallentin, L.; Siegbahn, A. Relationship between interleukin 6 and mortality in patients with unstable coronary artery disease: effects of an early invasive or noninvasive strategy. JAMA 2001, 286, 2107–2113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hedman, A.; Larsson, P.T.; Alam, M.; Wallen, N.H.; Nordlander, R.; Samad, B.A. CRP, IL-6 and endothelin-1 levels in patients undergoing coronary artery bypass grafting. Do preoperative inflammatory parameters predict early graft occlusion and late cardiovascular events? Int. J. Cardiol. 2007, 120, 108–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Souza, J.R.; Oliveira, R.T.; Blotta, M.H.; Coelho, O.R. Serum levels of interleukin-6 (Il-6), interleukin-18 (Il-18) and C-reactive protein (CRP) in patients with type-2 diabetes and acute coronary syndrome without ST-segment elevation. Arq. Bras. Cardiol. 2008, 90, 86–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mann, D.L. Inflammatory mediators and the failing heart: past, present, and the foreseeable future. Circ. Res. 2002, 91, 988–998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, M.; Yang, D.; Xiang, M.; Wang, J. Role of interleukin-6 in regulation of immune responses to remodeling after myocardial infarction. Heart Fail. Rev. 2015, 20, 25–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsutamoto, T.; Hisanaga, T.; Wada, A.; Maeda, K.; Ohnishi, M.; Fukai, D.; Mabuchi, N.; Sawaki, M.; Kinoshita, M. Interleukin-6 spillover in the peripheral circulation increases with the severity of heart failure, and the high plasma level of interleukin-6 is an important prognostic predictor in patients with congestive heart failure. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 1998, 31, 391–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsujinaka, T.; Fujita, J.; Ebisui, C.; Yano, M.; Kominami, E.; Suzuki, K.; Tanaka, K.; Katsume, A.; Ohsugi, Y.; Shiozaki, H.; Monden, M. Interleukin 6 receptor antibody inhibits muscle atrophy and modulates proteolytic systems in interleukin 6 transgenic mice. J. Clin. Invest. 1996, 97, 244–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fuchs, M.C.; Hilfiker, A.; Kaminski, K.; Hilfiker-Kleiner, D.; Guener, Z.; Klein, G.; Podewski, E.; Schieffer, B.; Rose-John, S.; Drexler, H. Role of interleukin-6 for LV remodeling and survival after experimental myocardial infarction. FASEB J. 2003, 17, 2118–2120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Markousis-Mavrogenis, G.; Tromp, J.; Ouwerkerk, W.; Devalaraja, M.; Anker, S.D.; Cleland, J.G.; Dickstein, K.; Filippatos, G.S.; van der Harst, P.; Lang, C.C.; et al. The clinical significance of interleukin-6 in heart failure: results from the BIOSTAT-CHF study. Eur. J. Heart Fail. 2019, 21, 965–973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alogna, A.; Koepp, K.E.; Sabbah, M.; Espindola Netto, J.M.; Jensen, M.D.; Kirkland, J.L.; Lam, C.S.P.; Obokata, M.; Petrie, M.C.; Ridker, P.M.; Sorimachi, H.; Tchkonia, T.; Voors, A.; Redfield, M.M.; Borlaug, B.A. Interleukin-6 in Patients with Heart Failure and Preserved Ejection Fraction. JACC Heart Fail. 2023, 11, 1549–1561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Everett, B.M.; Cornel, J.H.; Lainscak, M.; Anker, S.D.; Abbate, A.; Thuren, T.; Libby, P.; Glynn, R.J.; Ridker, PM. Anti-inflammatory therapy with canakinumab for the prevention of hospitalization for heart failure. Circulation 2019, 139, 1289–1299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ridker, P.M. Anticytokine Agents: Targeting Interleukin Signaling Pathways for the treatment of atherothrombosis. Circ. Res. 2019, 124, 437–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rehman, K.; Akash, M.S.H.; Liaqat, A.; Kamal, S.; Qadir, MI.; Rasul, A. Role of Interleukin-6 in Development of Insulin Resistance and Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus. Crit. Rev. Eukaryot. Gene. Expr. 2017, 27, 229–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spranger, J.; Kroke, A.; Möhlig, M.; Hoffmann, K.; Bergmann, M.M.; Ristow, M.; Boeing, H.; Pfeiffer, A.F. Inflammatory cytokines and the risk to develop type 2 diabetes: results of the prospective population-based European Prospective Investigation into Cancer and Nutrition (EPIC)-Potsdam Study. Diabetes 2003, 52, 812–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, X.; Bao, W.; Liu, J.; Ouyang, Y.Y.; Wang, D.; Rong, S.; Xiao, X.; Shan, Z.L.; Zhang, Y.; Yao, P.; Liu, LG. Inflammatory markers and risk of type 2 diabetes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Diabetes Care 2013, 36, 166–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pradhan, A.D.; Manson, J.E.; Rifai, N.; Buring, J.E.; Ridker, P.M. C-reactive protein, interleukin 6, and risk of developing type 2 diabetes mellitus. JAMA. 2001, 286, 327–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kern, P.A.; Ranganathan, S.; Li, C.; Wood, L.; Ranganathan, G. Adipose tissue tumor necrosis factor and interleukin-6 expression in human obesity and insulin resistance. Am. J. Physiol. Endocrinol. Metab. 2001, 280, E745–751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kawazoe, Y.; Naka, T.; Fujimoto, M.; Kohzaki, H.; Morita, Y.; Narazaki, M.; Okumura, K.; Saitoh, H.; Nakagawa, R.; Uchiyama, Y.; Akira, S.; Kishimoto, T. Signal transducer and activator of transcription (STAT)-induced STAT inhibitor 1 (SSI-1)/suppressor of cytokine signaling 1 (SOCS1) inhibits insulin signal transduction pathway through modulating insulin receptor substrate 1 (IRS-1) phosphorylation. J. Exp. Med. 2001, 193, 263–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emanuelli, B.; Peraldi, P.; Filloux, C.; Sawka-Verhelle, D.; Hilton, D.; Van Obberghen, E. SOCS-3 is an insulin-induced negative regulator of insulin signaling. J. Biol. Chem. 2000, 275, 15985–15991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krebs, D.L.; Hilton, D.J. SOCS: physiological suppressors of cytokine signaling. J. Cell. Sci. 2000, 113, 2813–2819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tilg, H.; Moschen, A.R. Inflammatory mechanisms in the regulation of insulin resistance. Mol. Med. 2008, 14, 222–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carey, AL. Interleukin-6 and tumor necrosis factor-alpha are not increased in patients with Type 2 diabetes: evidence that plasma interleukin-6 is related to fat mass and not insulin responsiveness. Diabetologia 2004, 47, 1029–1037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vozarova, B.; Weyer, C.; Hanson, K.; Tataranni, P.A.; Bogardus, C.; Pratley, R.E. Circulating interleukin-6 in relation to adiposity, insulin action, and insulin secretion. Obes. Res. 2001, 9, 414–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lyngso, D.; Simonsen, L.; Bulow, J. Interleukin-6 production in human subcutaneous abdominal adipose tissue: the effect of exercise. J. Physiol. 2002, 543, 373–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harder-Lauridsen, N.M.; Krogh-Madsen, R.; Holst, J.J.; Plomgaard, P.; Leick, L.; Pedersen, B.K.; Fischer, C.P. Effect of IL-6 on the insulin sensitivity in patients with type 2 diabetes. Am. J. Physiol. Endocrinol. Metab. 2014, 306, E769–E778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hwa, V.; Nadeau, K.; Wit, J.M.; Rosenfeld, R.G. STAT5b deficiency: lessons from STAT5b gene mutations. Best. Pract. Res. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2011, 25, 61–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Georgakis, M.K.; Malik, R.; Burgess, S.; Dichgans, M. Additive Effects of Genetic Interleukin-6 Signaling Downregulation and Low-Density Lipoprotein Cholesterol Lowering on Cardiovascular Disease: A 2×2 Factorial Mendelian Randomization Analysis. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 2022, 11, e023277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Catapano, A.L.; Pirillo, A.; Norata, G.D. Vascular inflammation and low-density lipoproteins: is cholesterol the link? A lesson from the clinical trials. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2017, 174, 3973–3985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ridker, P.M. From C-Reactive Protein to Interleukin-6 to Interleukin-1: Moving Upstream To Identify Novel Targets for Atheroprotection. Circ. Res. 2016, 118, 145–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lubrano, V.; Gabriele, M.; Puntoni, MR.; Longo, V.; Pucci, L. Relationship among IL-6, LDL cholesterol and lipid peroxidation. Cell. Mol. Biol. Lett. 2015, 20, 310–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schuett, H.; Luchtefeld, M.; Grothusen, C.; Grote, K.; Schieffer, B. How much is too much? Interleukin-6 and its signalling in atherosclerosis. Thromb. Haemost. 2009, 102, 215–222. [Google Scholar]

- Gierens, H.; Nauck, M.; Roth, M.; Schinker, R.; Schürmann, C.; Scharnagl, H.; Neuhaus, G.; Wieland, H.; März, W. Interleukin-6 stimulates LDL receptor gene expression via activation of sterol-responsive and Sp1 binding elements. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2000, 20, 1777–1783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zuliani, G.; Volpato, S.; Blè, A.; Bandinelli, S.; Corsi, AM.; Lauretani, F.; Paolisso, G.; Fellin, R.; Ferrucci, L. High interleukin-6 plasma levels are associated with low HDL-C levels in community-dwelling older adults: the InChianti study. Atherosclerosis 2007, 192, 384–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Caselli, C.; De Graaf, M.A.; Lorenzoni, V.; Rovai, D.; Marinelli, M.; Del Ry, S.; Giannessi, D.; Bax, J.J.; Neglia, D.; Scholte, A.J. HDL cholesterol, leptin and interleukin-6 predict high risk coronary anatomy assessed by CT angiography in patients with stable chest pain. Atherosclerosis 2015, 241, 55–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mosesson, M.W.; Siebenlist, K.R.; Meh, D.A. The structure and biological features of fibrinogen and fibrin. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2001, 936, 11–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neerman-Arbez, M.; Casini, A. Clinical Consequences and Molecular Bases of Low Fibrinogen Levels. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2018, 19, 192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vilar, R.; Fish, R. J, Casini, A, et al: Fibrinogen in human disease: both friend and foe. Haematologica 2020, 105, 284–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bridge, K.I.; Philippou, H.; Ariens, R. Clot properties and cardiovascular disease. Thromb. Haemost. 2014, 112, 901–908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W. Identification of respective lysine donor and glutamine acceptor sites involved in factor XIIIa-catalyzed fibrin alpha chain cross-linking. J. Biol. Chem. 2011, 286, 44952–44964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Vries, J.J.; Snoek, C.J.M.; Rijken, D. C, et al: Effects of Post-Translational Modifications of Fibrinogen on Clot Formation, Clot Structure, and Fibrinolysis: A Systematic Review. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2020, 40, 554–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weisel, J.W.; Litvinov, R.I. Mechanisms of fibrin polymerization and clinical implications. Blood 2013, 121, 1712–1719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luzak, B.; Boncler, M.; Kosmalski, M.; Mnich, E.; Stanczyk, L.; Przygodzki, T.; Watala, C. Fibrinogen Glycation and Presence of Glucose Impair Fibrin Polymerization-An In Vitro Study of Isolated Fibrinogen and Plasma from Patients with Diabetes Mellitus. Biomolecules 2020, 10, 877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farrell, D.H. γ' Fibrinogen as a novel marker of thrombotic disease. Clin. Chem. Lab. Med. 2012, 50, 1903–1909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Uitte de Willige, S.; de Visser, MC.; Houwing-Duistermaat, J.J.; Rosendaal, F.R.; Vos, H.L.; Bertina, R.M. Genetic variation in the fibrinogen gamma gene increases the risk for deep venous thrombosis by reducing plasma fibrinogen gamma' levels. Blood 2005, 106, 4176–4183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kannel, W.B.; Wolf, P.A.; Castelli, W.P.; D’Agostino, R.B. Fibrinogen and risk of cardiovascular disease. JAMA 1987, 258, 1183–1186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kryczka, K.E.; Kruk, M.; Demkow, M.; Lubiszewska, B. Fibrinogen and a Triad of Thrombosis, Inflammation, and the Renin-Angiotensin System in Premature Coronary Artery Disease in Women: A New Insight into Sex-Related Differences in the Pathogenesis of the Disease. Biomolecules 2021, 11, 1036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, J.; Hennekens, C.H.; Ridker, P.M.; Stampfer, M.J. A prospective study of fibrinogen and risk of myocardial infarction in the Physicians' Health Study. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 1999, 33, 1347–1452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Danesh, J.; Lewington, S.; Thompson, S.G.; Lowe, G.D.; Collins, R.; Kostis, J.B.; Wilson, A.C.; Folsom, A.R.; Wu, K.; Benderly, M.; et al. Plasma fibrinogen level and the risk of major cardiovascular diseases and nonvascular mortality: an individual participant meta-analysis. JAMA 2005, 294, 1799–1809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bai, Y.; Zheng, Y.Y.; Tang, J.N.; Yang, X.M.; Guo, Q.Q.; Zhang, J.C.; Cheng, M.D.; Song, F.H.; Wang, K.; Zhang, Z.L.; et al. D-Dimer to Fibrinogen Ratio as a Novel Prognostic Marker in Patients After Undergoing Percutaneous Coronary Intervention: A Retrospective Cohort Study. Clin. Appl. Thromb. Hemost. 2020, 26, 1076029620948586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, D.P.; Mao, X.F.; Wu, T.T.; Chen, Y.; Hou, X.G.; Yang, Y.; Ma, X.; Zhang, J.Y.; Ma, Y.T.; Xie, X.; et al. The Fibrinogen-to-Albumin Ratio Is Associated With Outcomes in Patients With Coronary Artery Disease Who Underwent Percutaneous Coronary Intervention. Clin. Appl. Thromb. Hemost. 2020, 26, 1076029620933008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, D.; Jiang, P.; Zhu, P.; Jia, S.; Zhang, C.; Liu, Y.; Liu, R.; Xu, J.; Tang, X.; Zhao, X.; et al. Prognostic value of fibrinogen in patients with coronary artery disease and prediabetes or diabetes following percutaneous coronary intervention: 5-year findings from a large cohort study. Cardiovasc. Diabetol. 2021, 20, 143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, Z.; Zhao, Y.; He, Y. Fibrinogen Level Predicts Outcomes in Critically Ill Patients with Acute Exacerbation of Chronic Heart Failure. Dis. Markers. 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Q.; Zhu, C.; Zhang, Q.; Hu, Z.; Ji, K.; Qian, L. Association between fibrinogen-to-albumin ratio and prognosis of patients with heart failure. Eur. J. Clin. Invest. 2023, 53, e14049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Isordia-Salas, I.; Galván-Plata, M.; Leaños-Miranda, A.; Aguilar-Sosa, E.; Anaya-Gómez, F.; Majluf-Cruz, A.; Santiago-Germán, D. Proinflammatory and prothrombotic state in subjects with different glucose tolerance status before cardiovascular disease. J. Diabetes. Res. 2014, 631902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, S.; Chapagain, A.; Nitsch, D.; Yaqoob, M. Proteinuria and hypoalbuminemia are risk factors for thromboembolic events in patients with idiopathic membranous nephropathy: an observational study. BMC. Nephrol. 2012, 13, 107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Cong, H.L.; Zhang, J.X.; Li, X.M.; Hu, Y.C.; Wang, C.; Lang, J.C.; Zhou, B.Y.; Li, T.T.; Liu, C.W.; Yang, H.; Ren, L.B.; Qi, W.; Li, W.Y. Prognostic performance of multiple biomarkers in patients with acute coronary syndrome without standard cardiovascular risk factors. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 2022, 9, 916085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, S.L.; Wu, N.Q.; Shi, H.W.; Dong, Q.; Dong, Q.T.; Gao, Y.; Guo, Y.L.; Li, J.J. Fibrinogen is associated with glucose metabolism and cardiovascular outcomes in patients with coronary artery disease. Cardiovasc. Diabetol. 2020, 19, 36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Raynaud, E.; Pérez-Martin, A.; Brun, J.; Aïssa-Benhaddad, A.; Fédou, C.; Mercier, J. Relationships between fibrinogen and insulin resistance. Atherosclerosis 2000, 150, 365–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barazzoni, R.; Kiwanuka, E.; Zanetti, M.; Cristini, M.; Vettore, M.; Tessari, P. Insulin acutely increases fibrinogen production in individuals with type 2 diabetes but not in individuals without diabetes. Diabetes 2003, 52, 1851–1856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perween, S.; Abidi, M.; Faizy, A.F.; Moinuddin. Post-translational modifications on glycated plasma fibrinogen: A physicochemical insight. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2019, 126, 1201–1212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Austin, G.E.; Mullins, R.H.; Morin, L.G. Non-enzymic glycation of individual plasma proteins in normoglycemic and hyperglycemic patients. Clin. Chem. 1987, 33, 2220–2224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rheeder, P.; Jerling, J.C.; Loots, D.T.; van der Westhuizen, F.H.; Gottsche, L.T.; Weisel, J.W. Glycation of fibrinogen in uncontrolled diabetic patients and the effects of glycaemic control on fibrinogen glycation. Thromb. Res. 2007, 120, 439–446. [Google Scholar]

- Pieters, M.; Covic, N.; Loots du, T.; van der Westhuizen, F.H.; van Zyl, D.G.; Rheeder, P.; Jerling, J.C.; Weisel, J.W. The effect of glycaemic control on fibrin network structure of type 2 diabetic subjects. Thromb. Haemost. 2006, 96, 623–629. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Pieters, M.; van Zyl, D.G.; Rheeder, P.; Jerling, J.C.; Loots, D.T.; van der Westhuizen, F.H.; Gottsche, L.T.; Weisel, J.W. Glycation of fibrinogen in uncontrolled diabetic patients and the effects of glycaemic control on fibrinogen glycation. Thromb. Res. 2007, 120, 439–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Halle, M.; Berg, A.; Keul, J.; and Baumstark, W.M. Association Between Serum Fibrinogen Concentrations and HDL and LDL Subfraction Phenotypes in Healthy Men. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 1996, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jia, C.; Wu, W.; Lu, H.; Liu, J.; Chen, S.; Liang, G.; Zhou, Y.; Yu, S.; Qiao, L.; Chen, J.; Tan, N.; Liu, Y.; Chen, J. Fibrinogen to HDL-Cholesterol ratio as a predictor of mortality risk in patients with acute myocardial infarction. Lipids Health Dis. 2024, 23, 86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaptoge, S.; White, I.R.; Thompson, S.G.; Wood, A.M.; Lewington, S.; Lowe, G.D.; Danesh, J. Associations of plasma fibrinogen levels with established cardiovascular disease risk factors, inflammatory markers, and other characteristics: individual participant meta-analysis of 154,211 adults in 31 prospective studies: the fibrinogen studies collaboration. Fibrinogen Studies Collaboration. Am. J. Epidemiol. 2007, 166, 867–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).