I. Introduction

Our perception of everything is not solely visual but holistic, considering all sensory modalities like sight, sound, touch, smell, and taste. The term modality refers to a particular way of doing or experiencing something; thus, a problem is termed multi-modal when it exhibits more than one of such modalities [

1,

2]. For Artificial Intelligence (AI) to progress in understanding the world around us, it must be able to use all the available information in multi-modal signals together [

3]. Multi-modal machine learning aims to build models to process and connect information from multiple modalities. It is a vibrant multi-disciplinary field of increasing significance and with astonishing possibility [

1].

Using the human learning process as inspiration, artificial intelligence (AI) researchers also try to apply different modalities to train deep learning models [

4]. At a very basic level, deep learning algorithms rely on an artificial neural network that undergoes training to improve its performance on a specific task. This task is typically expressed in mathematics through what is referred to as a loss function, which stands for the goal that neural networks seek to improve upon during the training period [

2]. The rapid advancement in technology and change in ways of data collection has caused an excess of raw data [

5]. But in such situations, the actual challenge lies in assimilating all those different types of data and conducting appropriate analysis [

6].

In most cases, conventional machine learning algorithms are developed to process only a particular input stream or modality, making it hard to harness the full benefits of data from diverse sources [

7]. Most conventional methods aren’t as effective as they could be, as they need to adapt to use multi-modal data. This situation motivated the rise of new models and techniques, which has led to various publications in the past ten years [

4,

8].

A. Definition of Multi-Modal Deep Learning

Multi-modal deep learning (MMDL) is defined as a type of deep learning that fuses and processes information from different sources, such as text, image, audio, video or sensor data [

9]. The purpose is to gather complementary information from many data types, improve model performance, and provide a more comprehensive understanding of complicated patterns or tasks that cannot be performed efficiently with a single modality [

2]. Multi-modal deep learning employs feature extraction, fusion, and alignment techniques to combine information from several modalities, resulting in more robust and accurate predictions [

1].

B. Objectives of the Review

This review aims to provide a comprehensive overview of the current advancements in multi-modal deep learning. The core concepts, diverse applications, key challenges, architecture, and bibliometric analysis, offering valuable insights into this rapidly evolving field, will be examined. The research aims to creatively appraise the literature from different areas, especially in engineering, identify research gaps and propose potential areas of interest going forward.

C. Structure of the Paper

This paper provides an overview of the current research in Multi-Modal Deep Learning (MMDL). It is organized into six chapters, each focusing on a specific aspect of MMDL, including its bibliometric analysis (II), core concepts (III), applications (IV), encoding/decoding architectures and challenges (V), summary and conclusion (VI)

II. Bibliometric Analysis

Bibliometric analysis is a valuable quantitative method for evaluating research output within a designated field of study. Systematically assessing publications and citations provides insights to help identify trends, influential works, and emerging areas of interest in the research landscape [

8].

A thorough literature survey was conducted to explore existing research on multi-modal deep learning and its applications. This was achieved by systematically searching for relevant keywords in article titles, abstracts, and keywords on Scopus. This approach allows for a better understanding of the current landscape and identification of areas for future research and development.

The Scopus database served as the data source for retrieving literature pertaining to multi-modal applications and deep learning. For the search query, the following was used: Search Query = (deep learning OR deep neural network OR deep model OR convolutional neural network OR CNN OR recurrent neural network OR RNN) AND (multi-modal OR multimodal OR multi-modality OR multi-modalities OR multimodalit*). By November 2024, the search yielded 912 entries. To enhance the relevance of the results, a more specific filter focused on the “engineering” subject area was applied. This streamlines the entries down to approximately 451. This approach helped in homing in on the most pertinent information.

912 research papers from the initial Scopus search were comprehensively analysed. This analysis included co-occurrence analysis, literature coupling, annual trends, journal publishing, and geographic distribution. The goal was to enhance understanding and advance research outputs in multi-modal deep learning. Through this approach, the aim was to identify key areas for development and promote further innovation in the field.

A. Keyword Co-Occurrence Analysis

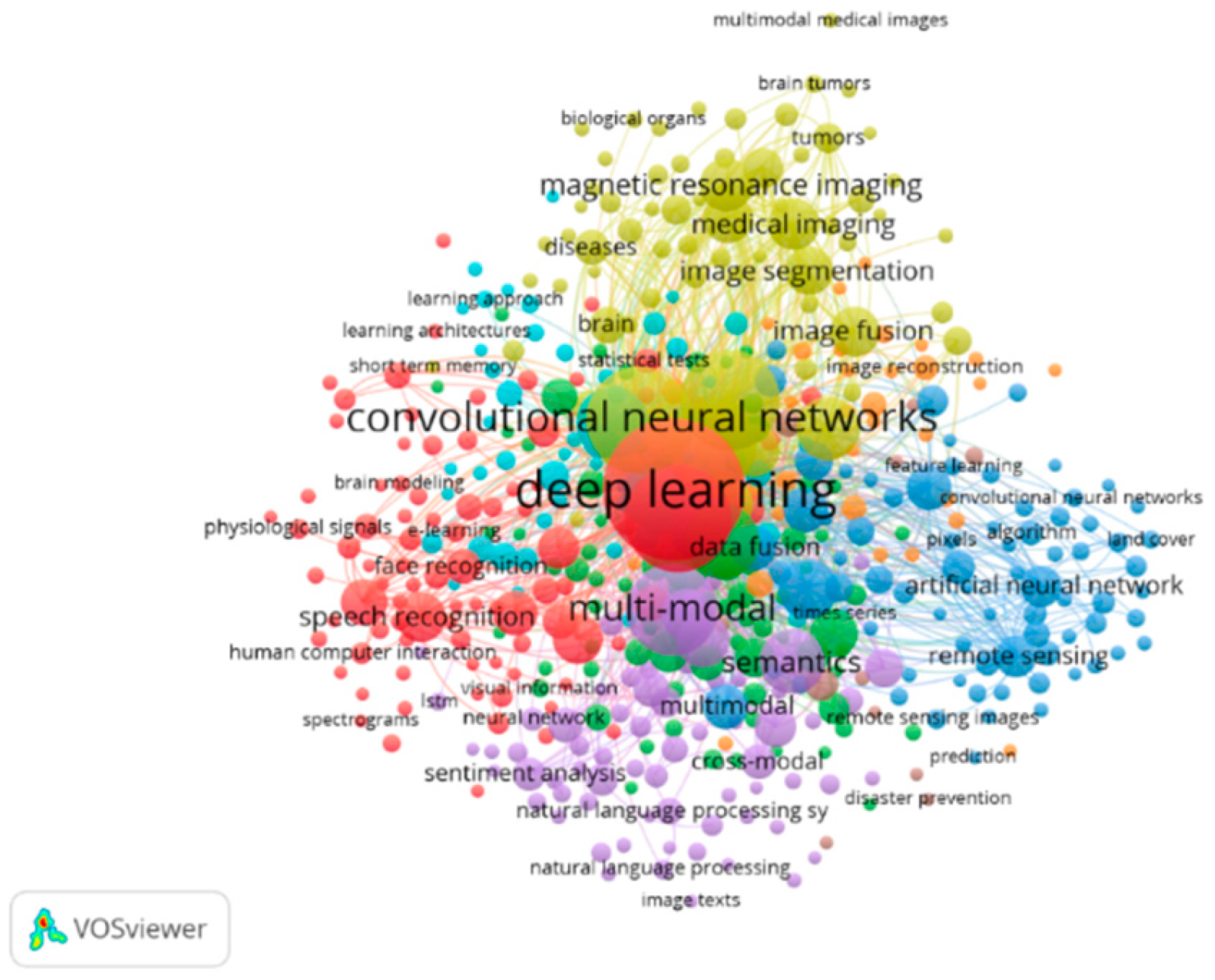

The significance of keyword co-occurrence lies in its ability to identify research hotspots within a specific area. To explore the research hotspots of multi-modal deep learning, a bibliometric analysis was conducted using a tool called VOSviewer. This analysis focused on the co-occurrence of keywords in 912 research papers, as illustrated in

Figure 2.1. Each node in the visual platform represents keyword density and is assigned a distinct colour based on its link density. The colour of the node also reflects the degree of closeness in its neighbouring relationships. The red keywords indicate high frequency, while the sky-blue keywords appear less frequently. A total of 6,461 keywords from multi-modal deep learning-related publications were gathered. Table I shows the top keywords and their corresponding co-occurrence. The font size in

Figure 2.1 represents weights, and this means the larger the node or keyword font, the larger its corresponding weights. Two keywords are said to occur simultaneously if there is a direct link between them. It can also be seen here that VOSviewer splits the keywords into eight clusters according to the strength of the coupling between two nodes, and every cluster is represented by the same colour. The keywords “deep learning” and “convolutional neural networks” appeared the most, then followed by “deep neural networks”, “convolutional neural network”, “convolution”, and “multi-modal”. The total link strength is calculated as the sum of the link strength of a node and the link strength of all other related nodes. This intensity, when observed, tells us the degree of closeness between correlated studies and could guide the direction of future research.

Table 1.

Keywords Of Mmdl-Related Publications.

Table 1.

Keywords Of Mmdl-Related Publications.

| Rank |

Keyword |

Total Link Strength |

Occurrences |

| 1 |

deep learning |

4369 |

536 |

| 2 |

convolutional neural networks |

2785 |

307 |

| 3 |

deep neural networks |

2601 |

307 |

| 4 |

convolutional neural network |

2573 |

266 |

| 5 |

convolution |

2281 |

221 |

| 6 |

multi-modal |

1995 |

225 |

| 7 |

neural networks |

1451 |

154 |

| 8 |

learning systems |

1370 |

139 |

| 9 |

classification |

1228 |

117 |

| 10 |

feature extraction |

1196 |

102 |

B. Other Analysis

Analysis of the literature shows that scholars from 35 countries or regions have published research related to MMDL. However, more than 85% of these publications came from just five active countries. China was the largest contributor, with researchers publishing 45% of articles. Following China, India ranked second with 18% of publications. The United States, the United Kingdom, and South Korea ranked third, fourth, and fifth, contributing 13%, 6%, and 4% of publications, respectively.

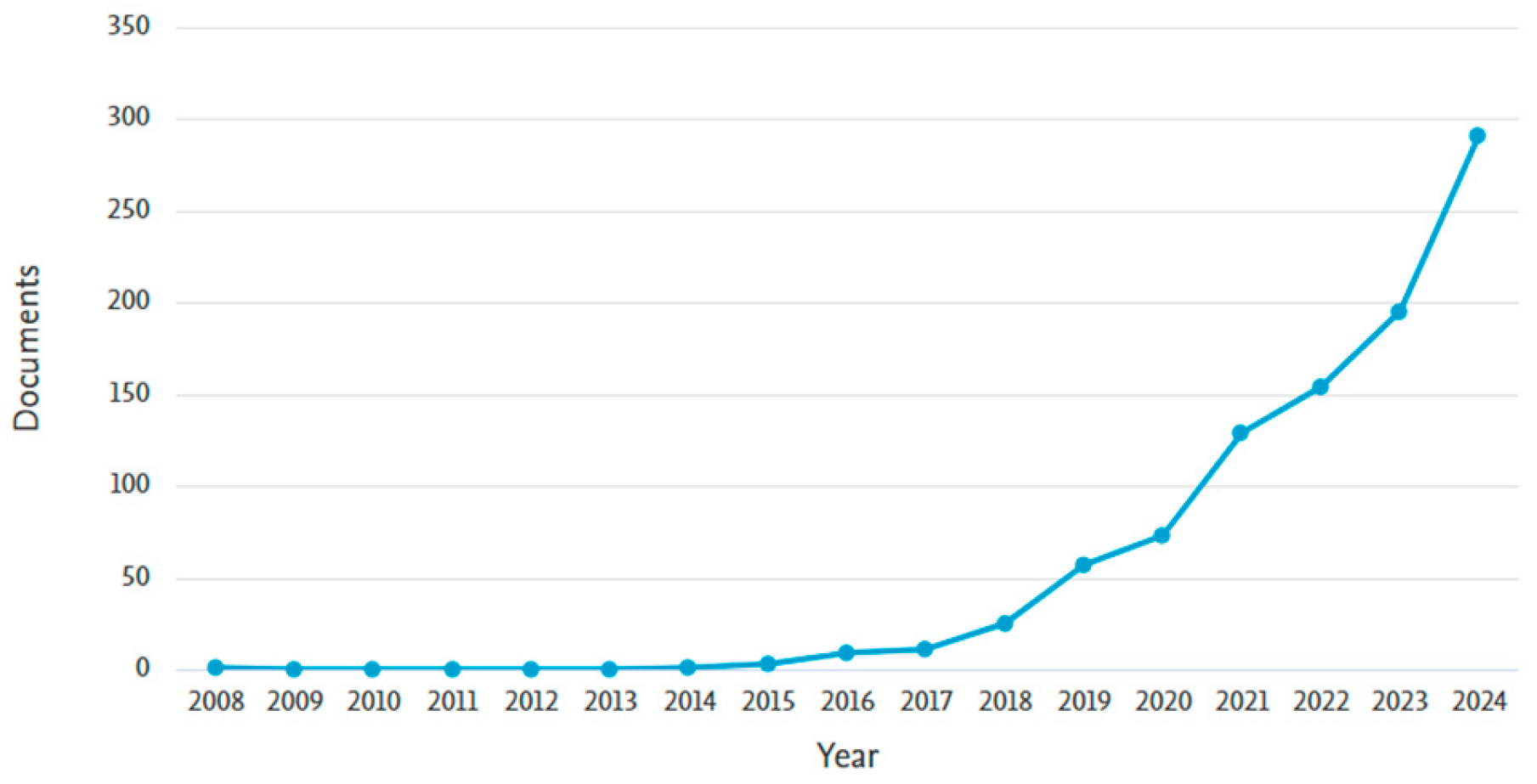

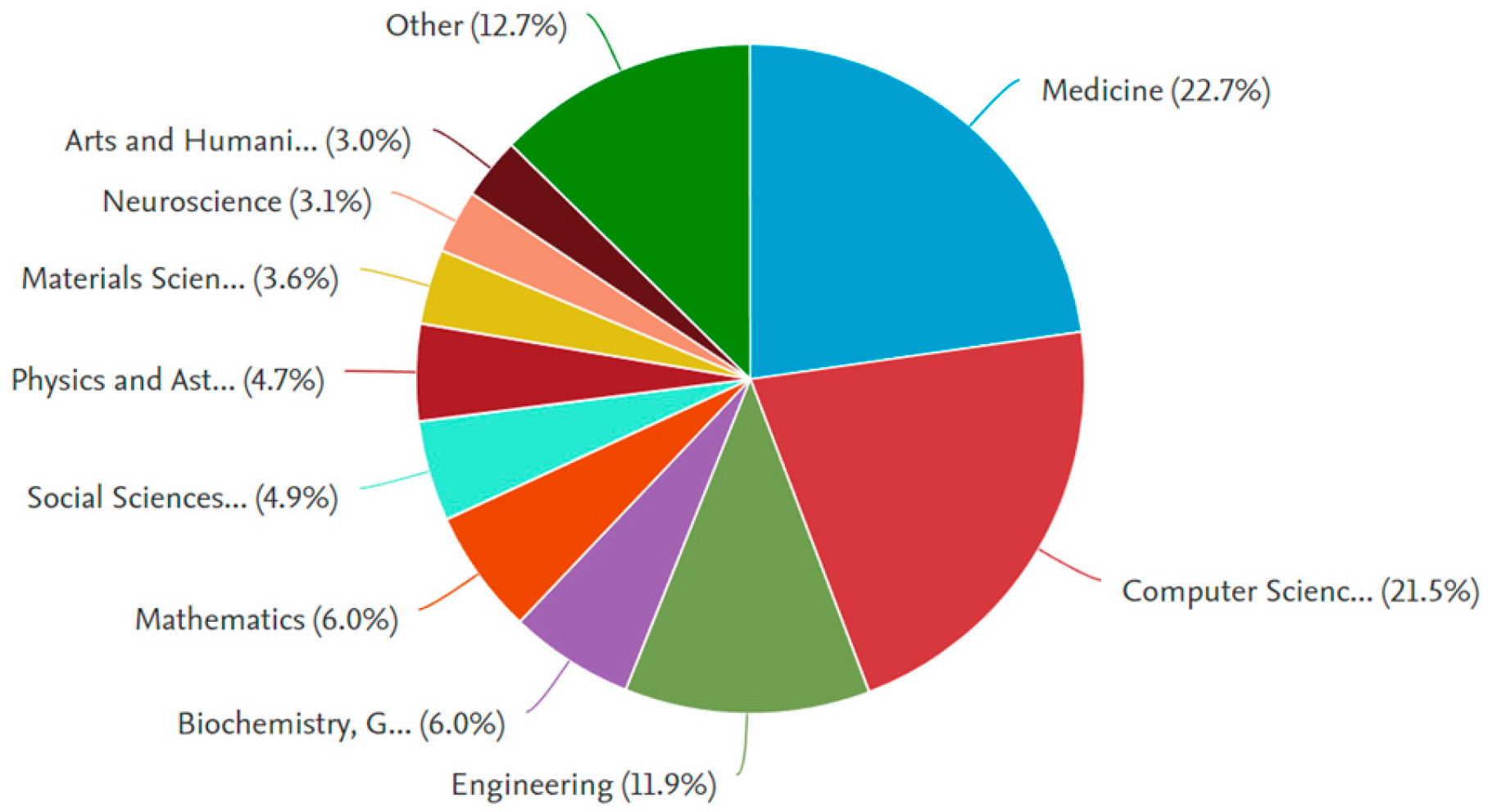

Figure 2.2 indicates the research papers published between 2008 and 2024 were analyzed. From 2008 to 2016, there was a steady but gradual increase in the number of publications. This was followed by a significant rise in papers from 2016 to 2020 and an exponential surge from 2020 to 2024. This trend highlights the growing popularity of the subject area, with the rapid increase in publications during the latter period attributed to the enhanced computing power available for training deep learning models. Multi-modal Deep Learning research is not restricted to the Medicine and Computer Science subject areas but covers a broader range of Scopus subject area categories. This is evident in the widespread implementation of MMDL concepts and applications across various fields. Medicine, Computer Science, and Engineering are the largest sectors, accounting for over 50% of the related research outputs.

Figure 2.3 illustrates the subject area associated with MMDL research documents and their respective percentages.

III. Core Concepts and Challenges in Multi-Modal Deep Learning

The domain of multi-modal deep learning extends the horizon through certain core principles governing how data from several sources can be integrated and processed. Broadly speaking, multi-modal deep learning aims to fuse information across data types, be they image, text, audio or sensor-based, instead of focusing on a single form of data [

6]. These principles are a foundation for building models capable of reasoning and learning from diverse information, making the models stronger and more accurate. With the growing amount and variety of data, understanding these core principles becomes increasingly important for addressing the complexities inherent in multi-modal data processing [

10]. In this chapter, we will explore the following five prominent challenges commonly encountered in Multi-modal deep learning: (a) representation: involves learning representations that reflect cross-modal interactions between individual elements. (b) translation: entails transferring information from one modality to another. (c) fusion: refers to combining information obtained from various sources into a single output. (d) alignment: involves identifying and modelling cross-modal linkages based on data structure, and (e) co-learning: refers to the process of exchanging knowledge from one or more modalities or learning processes to improve the learning process in each.

A. Representation

Data representation is key in multi-modal deep learning to successfully integrate information from diverse modalities [

11,

12]. One major obstacle is creating data representations that reflect the distinctive qualities of each modality while keeping their connections [

1]. Standard methods primarily focus on the simple concatenation of data from several modalities; however, this method has issues capturing complex interactions [

11].

Recent developments in representation learning have produced more advanced methods, such as joint embedding spaces and attention processes, that allow representations to be dynamic and context sensitive [

13]. Attention mechanisms can, for instance, be used to give more importance to different features with respect to a given task; this enables the model to focus on the most salient aspects of the data. This is especially beneficial in tasks such as video analysis, where the temporal dynamics of the data are relevant to deciding the final output [

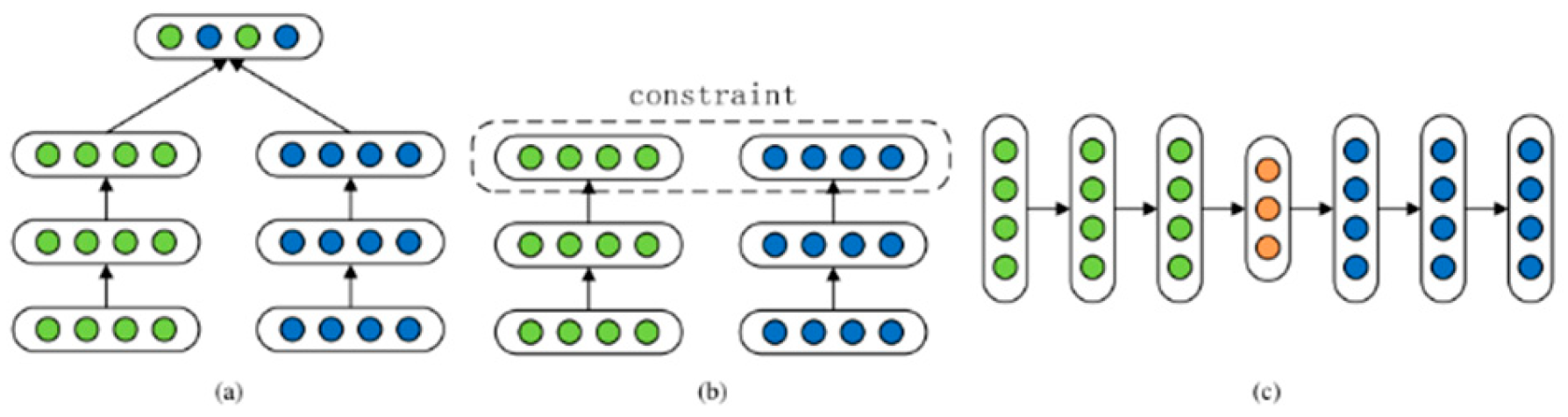

14]. Guo et al. (2019) classify deep multi-modal representation methods into three categories of frameworks shown in

Figure 3.1.

a. Joint representation involves projecting unimodal representations into a shared semantic subspace to combine multi-modal data.

b. Coordinated representation using cross-modal similarity models and canonical correlation analysis to learn separate but constrained representations for each modality in a coordinated subspace.

c. Encoder-decoder framework maps one modality into another without losing its attributes.

Each framework has a unique approach to integrating multiple modalities, which are shared by some applications.

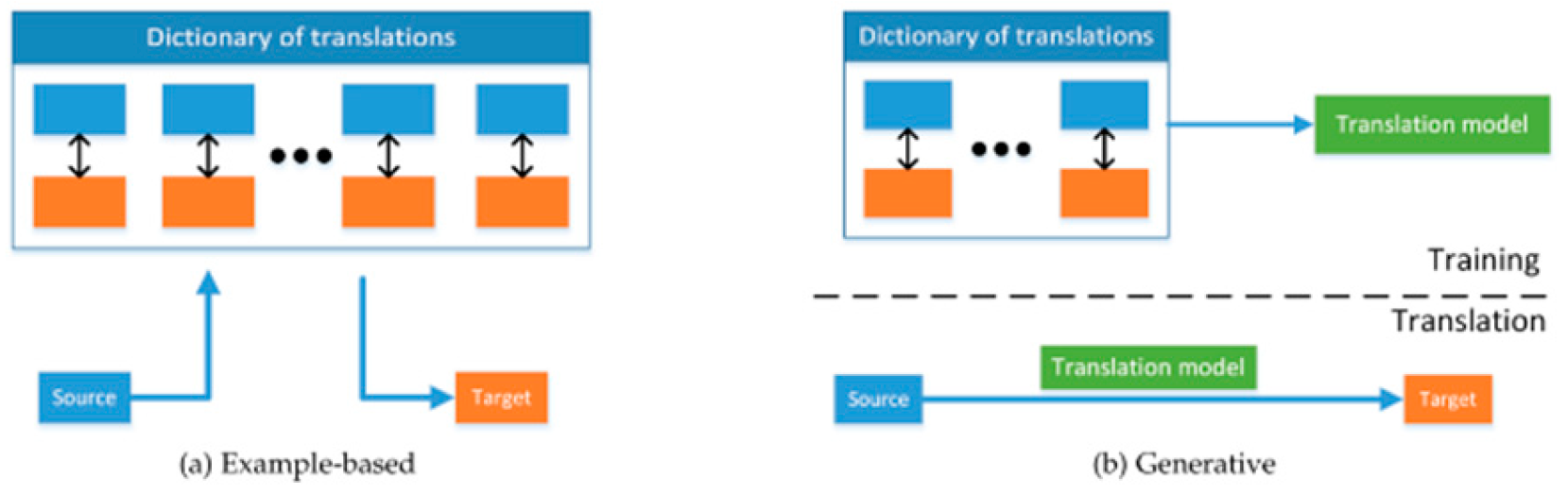

B. Translation

Data translation includes transferring information from one modality to another [

1,

15]. This is a common task in applications like image captioning, which aims to offer a textual description of an image, and voice recognition, which converts spoken language into text [

16]. One of the concerns in data translation is the retention of semantic integrity (attributes). As an example, the generation of an image from a text description requires the model must adequately capture visual characteristics derived from the text [

17].

To address such problems, techniques such as conditional generative adversarial networks (cGANs) have evolved, which condition the generation process on properties derived from the input modalities [

1].

Figure 3.2 shows an overview of example-based and generative multi-modal translation. The former fetches the best translation from a dictionary, whereas the latter first trains a translation model on the dictionary and then utilises that model for translation (adapted from [

1]).

C. Alignment

Alignment is connecting the relationships between sub-components of data from several modalities [

18]. This is important because different modalities provide useful complementary information that must be synchronised [

1]. For example, aligning the audio and visual streams is essential for voice recognition and emotion identification in analysing videos. Also, alignment raises critical questions that we could ask ourselves, as raised by Liang et al., such as how we can connect specific movements with spoken words or utterances while analysing a human subject’s speech and gestures [

9]. Traditional alignment approaches, such as canonical correlation analysis (CCA), have been used to identify common subspaces that allow data from many modalities to be compared. Still, these methods always need extensive manual tuning and may not be adequately scalable to big data [

1]. Deep learning-based alignment techniques, such as recurrent neural networks (RNNs) or transformer architectures, provide a more scalable and automated approach. These techniques can dynamically alter the alignment based on the specific characteristics of the data, making them more robust for applications [

19].

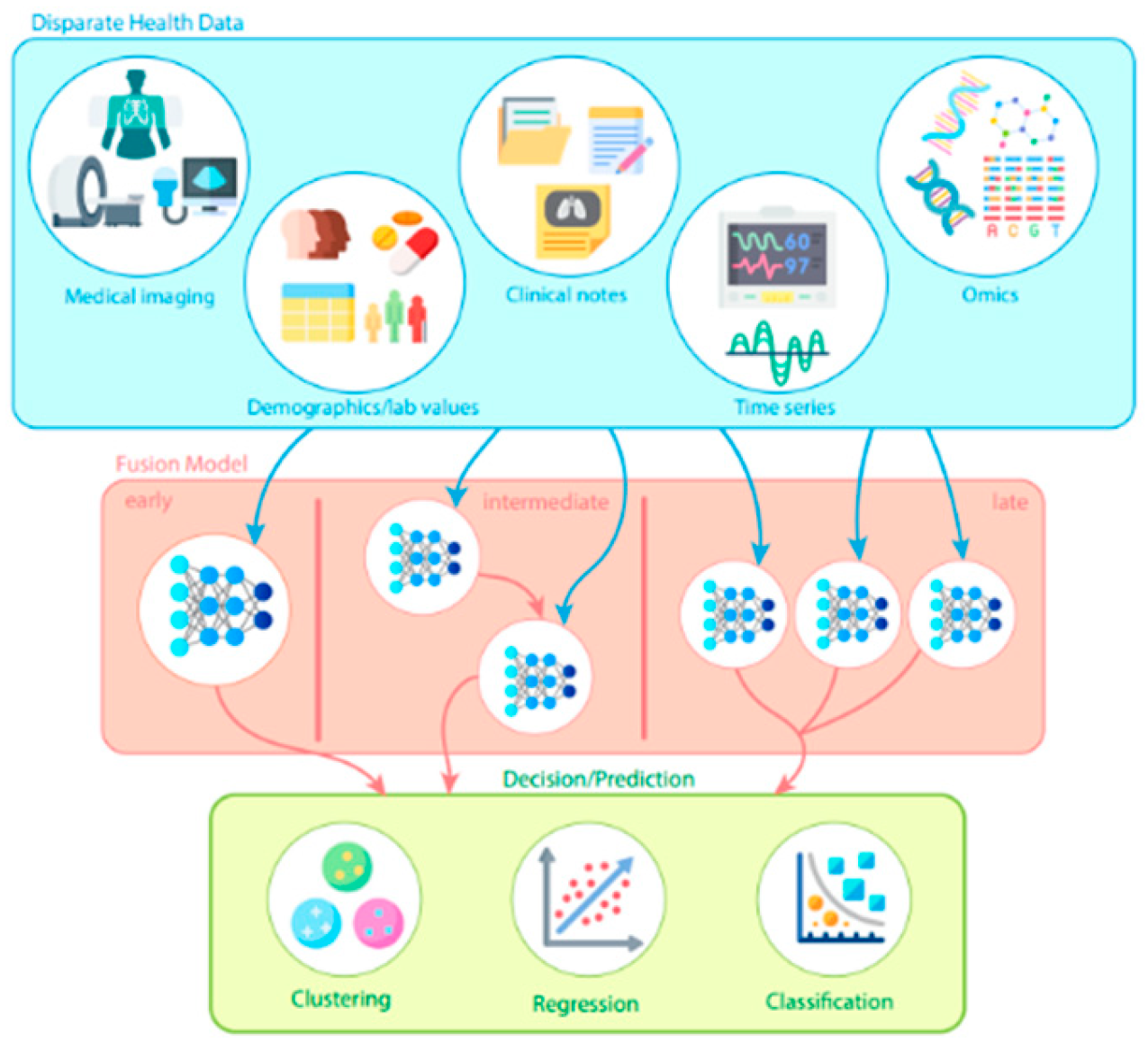

D. Fusion

It is important to note that fusion approaches in multi-modal deep learning assume integrating information derived from several different modalities into a single output. There are three ways of performing fusion: early, late and hybrid, as illustrated in

Figure 3.4. Each technique has advantages and disadvantages, depending on the case [

1,

6]. Early fusion is used to combine features or representational information of different modalities in the early part of the model, which promotes better interaction of the modalities in the learning process. This is beneficial in problems where the given modalities are very dependent on each other, for instance, during sensor fusion for autonomous vehicles [

10]. However, late fusion uses the output of separate modalities employing different models which were learnt independently; voting and ensemble averaging are done afterwards [

1,

20]. Hybrid fusion solutions combine the benefits of both approaches by fusing at multiple phases of the model stepwise, where outputs from one model become inputs for another [

20].

The current state of fusion techniques reflects an important evolution in methods and applications across several domains, particularly in medicine, emotion recognition, and image processing as illustrated in Table 3. S.K.B et al. emphasise that deep learning fusion techniques have consistently improved diagnostic accuracy and timely identification of lung cancer cases where neither medical imaging, genomics, nor clinical data alone suffices for accurate diagnosis [

21]. Also, Stahlschmidt et al. proceed to buttress the understanding of missing modalities in multi-modal data and some of the fusion approaches that these authors investigate, like the use of multi-task learning and generative models to resolve such challenges [

22].

In the latest studies, scholars have been focusing on and enhancing the existing techniques of fusion using deep learning models with features such as attention mechanisms and transformer networks. These models can give relative importance to each modality depending on the task. Attention mechanisms can also be used in multi-modal speech emotion recognition to focus on the most important features of each modality, leading to better performance [

23].

Table 2.

DIFFERENT FUSION TYPES AND BASE MODELS/ARCHITECTURES IMPLEMENTED IN THIS REVIEW.

Table 2.

DIFFERENT FUSION TYPES AND BASE MODELS/ARCHITECTURES IMPLEMENTED IN THIS REVIEW.

| Fusion Type |

Base Models |

Modalities |

References |

| Early |

CNN |

Image (IR and Visible |

[24] |

| CNN, LSTM |

Audio, Video |

[25] |

| LSTM, GRU, Bert |

Audio, Video, text |

[26] |

| Late |

CNN, RNN, GNN |

Image, NPK, Microscopic data |

[27] |

| CNN, RNN |

Image, text |

[28] |

| LSTM, CNN |

Image, text, audio |

[29] |

| NLP, CNN |

Text, Audio, Image |

[30] |

| Hybrid |

Sparse RBM |

Audio, video |

[4] |

| DBM |

Image, text |

[31] |

| CNN/LSTM |

Text, Image |

[32] |

| CNN |

Audio, video, text |

[33] |

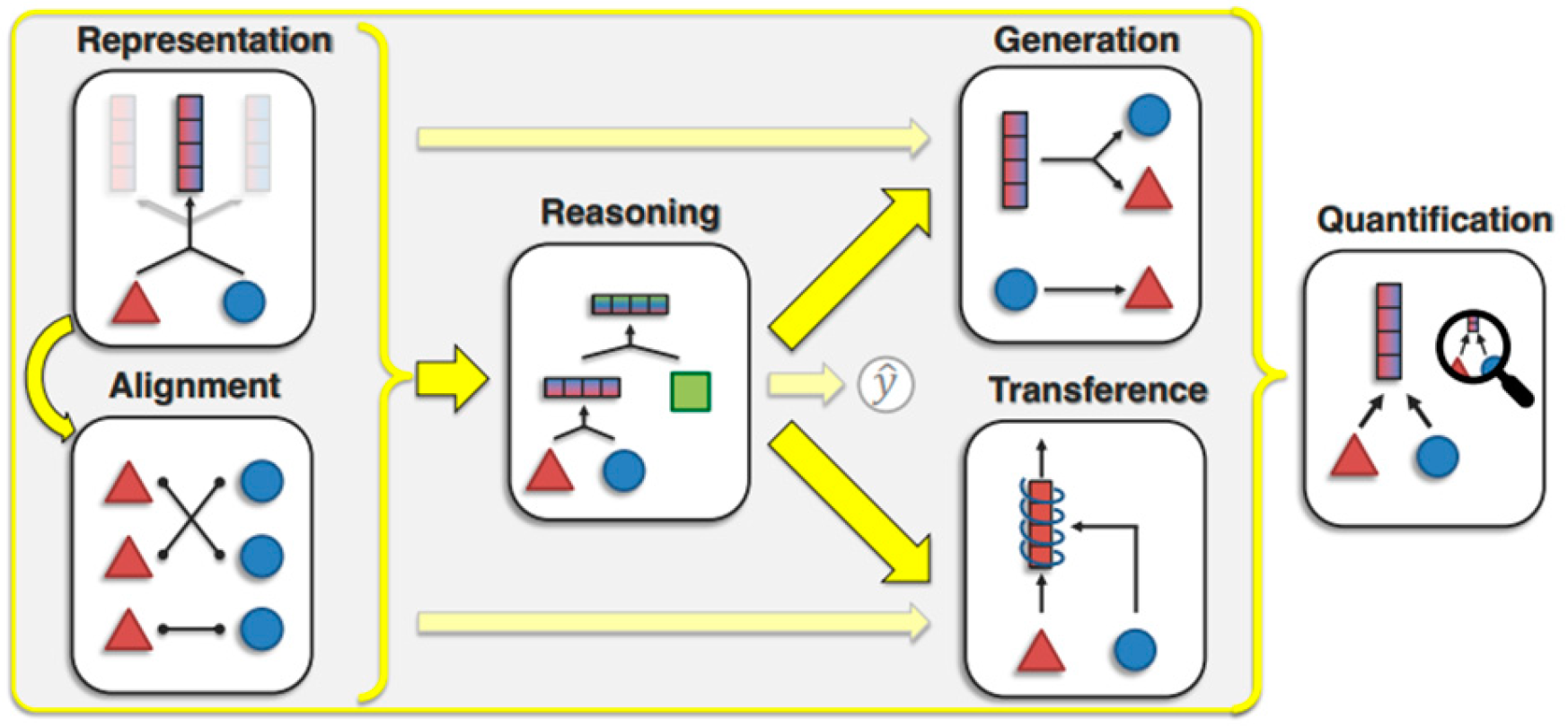

E. Co-Learning

Co-learning refers to the design of sharing knowledge from one or several modalities or learning processes, looking to improve the learning process in each modality. This is especially helpful when one modality is quite useful, and the other is sparse or noisy. Co-learning may help exploit the benefits associated with each modality and ultimately boost the whole system’s performance [

1]. One type of co-learning is multi-task learning, in which one model is trained on multiple tasks consisting of different modalities [

1]. This allows the model to learn common features, which can be helpful in performing many tasks and lead to improved generalisation [

10]. Another approach is transfer learning, which enables knowledge gained from one modality to be used for another, facilitating the performance of tasks learned with less data [

1].

Alongside Representation and Alignment, Liang et al. (2022) highlight four other core challenges, as shown in

Figure 3.5, which they claim are useful for classifying the different challenges. They are (a) Reasoning, defined as knowledge fabrication through formulating several inferential steps; (b) Generation, producing raw modalities that reflect cross-modal interactions; (c) Transference, the process of transferring knowledge between different modalities; and (d) Quantification involving empirical and theoretical studies aimed at understanding the multi-modal learning process.

IV. Applications of Multi-Modal Deep Learning

This chapter explores several domains where multi-modal deep learning has been successfully applied. It covers various domains, including healthcare, autonomous systems, natural language processing, environmental monitoring, social media analytics, mining and minerals. It illustrates how multi-modal techniques solve real-world problems in these fields by effectively integrating information from multiple data sources. Table III shows some of these interesting applications.

A. Healthcare and Medical Imaging

Due to the advancement of medical technology, the fusion of medical images has gained widespread popularity in image processing. Medical imaging methods are divided into two types: functional imaging and anatomical imaging. Unimodal medical images cannot provide full insights but only give insight into a particular aspect of health information [

8]. Multi-modal deep learning models in healthcare applications have been encouraging, especially in medical imaging. The application of multi-modal models, encompassing data from more imaging modalities such as MRI, CT, and PET scans, provides a more definitive patient status. As a result, more accurate diagnoses, appropriate treatment regimens, and better patient outcomes can be achieved [

21].

In oncology, multi-modal deep learning models proposed by S.K.B et al. efficiently separate and classify tumours employing both MRI and PET, whereas using only one single-modality technique will likely diminish accuracy. MRI produces high-resolution images of soft tissues, whereas PET scans provide metabolic data that can identify active malignant spots. By combining different modalities, deep learning models can detect tumours sooner, forecast their growth patterns, and even assess the efficiency of treatments [

21]. Another important application is in radiology, where multi-modal techniques are used to improve the diagnosis and characterisation of complex illnesses such as neurological disorders such as Alzheimer’s and multiple sclerosis. Such multi-modal models have also been helpful in minimising false positives and negatives, which are crucial in clinical settings [

34].

The study by Sangeetha et al. (2024) recommended using a Multi-modal Fusion Deep Neural Network (MFDNN) in lung cancer detection by integrating medical images, genomics and clinical data. The merging of these modalities addresses the shortcomings of individual sources and increases cancer classification accuracy. The MFDNN method reported the best classification accuracy of 92.5 %, precision at 87.4 %, and the F1-score at 86.2 %, surpassing traditional models such as CNN and ResNet. Spatiotemporal fusion models can integrate different types of inputs by deep neural networks to exploit data patterns across time and space. Such fusion enhances early detection of the condition and possibly leads to fewer missed diagnoses in a clinical setting, positioning MFDNN as a powerful model for cancer diagnosis in medicine [

21].

In their recent work, Song et al. propose a Multi-modal Feature Interaction Network (MFINet) aiming to fuse CT and MRI images, improving the ability to diagnose by using complementary information from these modalities. The model framework includes a shallow feature extractor, a deep feature extraction module (DFEM) with gated feature enhancement units and an image reconstruction module. A key innovation is using a gated normalisation block to optimise feature selection during fusion. In evaluations across multiple metrics (mutual information, spatial frequency, visual information fidelity), MFINet outperformed nine state-of-the-art methods, achieving superior clarity and structural preservation in the fused images. This method shows promise in improving diagnostic precision by merging the dense information from CT images with soft tissue details from MRI images [

35].

Oyelade et al. (2024) sought to enhance the classification of breast cancer images based on the fusion of different types of images, including mammograms and MRIs. They developed a twin Convolutional Neural Network model, which is interestingly called TwinCNN. This improves the drawbacks of standard unimodal methods by using different features from different data streams without difficulty. The authors note that optimising each of the models within the TwinCNN is necessary to avoid unnecessary losses that could affect overall performance. They also introduce an innovative binary dimensionality reduction technique to optimise features in medical imaging. This work not only pushes further the latest developments in breast cancer classification but also demonstrates the importance of logits for multimodal fusion in future research [

36].

B. Autonomous Systems and Robotics

Multi-modal deep learning is particularly beneficial for autonomous systems and robotics, as it significantly enhances machines’ capabilities to perceive and interact with their environments effectively. By integrating multiple modes of information, these systems can achieve a better understanding of their surroundings, leading to more intelligent and responsive behaviour. Take the case of an autonomous vehicle. The vehicle employs various systems such as cameras, LIDAR, radar and ultrasonic sensors to manoeuvre through difficult scenarios. Each sensor provides different information: for instance, the camera records images, LIDAR measures distances accurately, radar captures objects in different weathers, and ultrasonic sensors measure the closeness of objects [

37].

One can also fulfil many additional objectives with the help of deep learning models, including consolidating information from different sources and presenting the information in a way that supports needs, such as object localisation, route planning, and obstacle avoidance. Outdoors, information from LIDAR data can be used to form a graphical map that helps see or identify items in the dark, which would be virtually impossible with cameras. At the same time, radar scans can work quite well on cloudy or rainy days, where both cameras and LIDAR might be ineffective. The combination of these modalities enhances decision-making and safer autonomous systems [

37].

In applying multi-modal deep learning to robotics, multiple modalities can be integrated to enhance tasks such as human-robot interaction and manipulation. For instance, a robot may possess visual and touch sensors, look at an object first, and then use the sensors to feel the weight, texture, and temperature. Considering this realistic experience, the robot can execute high-level tasks such as sorting, object assembly and even social interactions with human beings [

24].

Ichiwara et al. (2023) developed a novel modality attention model for robot motion generation. It enhances robustness and interpretability through multi-modal prediction by organising a hierarchical structure of recurrent neural networks (RNNs), which compute separate modalities like vision and force individually and yet harmonise them in the performance of tasks. More importantly, the model exhibits remarkable performance precision in tasks such as assembling different pieces of furniture even when noise is present, unlike most typical models, where performance drops. The research shows the importance of modality attention, allowing robots to adaptively focus on relevant sensory inputs during different stages of a task, thereby improving operational flexibility. This study is beneficial in advancing this robotics domain by enabling the development of more advanced and robust robotic systems [

38].

Alternatively, Liu et al. present new ideas for multi-spectral pedestrian detection by augmenting deep semantic features with edge information from infrared thermal images. It has been observed that the detection performance increases significantly in low-light conditions. The method involves an additional CNN-based edge detection module with edge attention operation (EAO), which enhances the localised representation of the edge profile. Edge features are very important for pedestrian detection in challenging conditions. In addition, the new FDENet model contains a global feature fusion module that efficiently regulates the modalities’ fusion order and improves the features’ robustness in a more organised manner. The experiment on the KAIST and CVC-14 datasets demonstrates that FDENet achieves comparable robustness and accuracy to traditional methods, highlighting its effectiveness in real-world applications. This work highlights the necessity of using different modalities to improve pedestrian detection performance [

39].

C. Natural Language Processing and Computer Vision

Growth is also witnessed in natural language processing (NLP) computer vision and multi-modal deep learning approaches, including combining text and image data. As an illustration, image captioning generates the output text as a description for the input image, which expects the model to understand both the image presented and the text to be authored [

28]. Furthermore, it has been observed that multi-modal models are generally employed in sentiment analysis tasks, which include studying social networks, product reviews, and other types of text to capture the emotions from the text. These models can take images, along with the text or videos, and provide the whole context, thereby predicting the sentiments more effectively [

40]. A post with a sarcastic compliment and a happy smiley may evoke a different emotion not represented by the text. Understanding such a post can be complex, as one may try to read the text’s tone and look at the image, which may explain more than the text [

17].

The MBR, a multi-modal Bayesian recommender system proposed by He et al., is based on utilising two different types of information, textual and visual, to improve the recommendation quality based on implicit user feedback. The MBR incorporates deep convolutional neural networks for image feature extraction and a language model for text comprehension. It also uses many user-centric sources to achieve system objective imaging. Research indicates that this model outperforms standard recommendation systems, particularly in scenarios where user-item interactions are complex. What is more important is that the study acknowledges the growing significance of multi-modal data in achieving better recommendations and increasing the satisfaction level of the users. Such a new strategy opens new avenues for research on personalised ranking techniques that leverage diverse data sources [

41].

D. Environmental Monitoring and Remote Sensing

Multi-modal deep learning can incorporate satellite images, weather elements, and geographical information system data in spatial modelling and monitoring in environmental studies, including remote sensing. Due to the amalgamation of data and explanatory models from various sources that improve knowledge of the phenomenon, it is particularly effective when ascertaining various environmental disturbances like deforestation, changes in air quality, or global warming [

42]. To illustrate, when it comes to landcover classification, sitting on more than one view, using optical images and synthetic aperture radar (SAR) data, is better than using any of the modalities on a single basis. Also, though optical scans capture a great amount of useful visual data, they are not useful for capturing surface roughness and moisture, which are obtainable with SAR data. By these means, these models are more efficient in classifying different coverages of a region, like forests, cities, and lakes, with the help of those data sources combined [

43].

Ramzan et al. (2023) use remote sensing and multi-modal deep learning to detect crop cover. The modalities involved were high-resolution NAIP images NDVI images from MODIS, and weather information. The DenseNet-201 CNN network and classification ensemble were utilised for high-resolution images and Weather data, respectively. They achieved an outstanding accuracy of 98.83% and an F1 score of 98.78%, highlighting the relevance of multi-modality and meta-learning for crop cover identification [

44].

Hong et al. (2021) proposed a general multi-modal deep learning (MDL) framework for remote sensing image classification. They focused on the questions of “what,” “where,” and “how” to fuse in multi-modal data. The study investigated five fusion architectures: early, middle, late, encoder-decoder, and cross-fusion. The framework is suitable for pixel-wise and spatial-spectral classifications using fully connected networks and convolutional neural networks, respectively. Using two multi-modal remote sensing datasets (HS-LiDAR and MS-SAR), classification accuracy was shown to be improved using the MDL framework [

45].

Zhang et al. (2022) developed a multi-modal model for species distribution incorporating remote sensing images and other factors. The authors worked with the raw GeoLifeCLEF 2020 data set that contains satellite images as well as data on environmental variables and occurrences of species. To a ResNet50 CNN architecture for image and species data integration, they add a Swin transformer architecture capable of integrating multiple data. They also reported that their multi-modal model, SDMM-Net, surpassed the performance of single-modality models and achieved the best accuracy ever on the dataset [

46].

A dual encoder-based cross-modal complementary fusion network (DECCFNet) was developed by Luo et al. (2024) for road extraction using high-resolution images and LiDAR data. They used a cross-modal feature fusion (CMFF) module to address the issues regarding effectively combining information from the two sets of features. The CMFF module overcomes the modal fusion problem in channel and spatial dimensions by rectifying and integrating two modal features. At the same time, contextual enhancement is performed using a multi-scale fusion strategy. They further embedded a multi-direction strip convolution (MDSC) module within the decoder to perform feature convolution from various angles, thereby enhancing the network focus on the road features. Their technique improved the IOU by a minimum of 2.94% and 2.8% compared to using any single data modality [

47].

Saeed et al. (2024) used data from GoPro cameras, featuring the sound of gravel and visual images of the corresponding road, which were labelled as either good or poor. In the early fusion, features from both modality using VGG19 were retrieved and joined followed by PCA for dimension reduction. In late fusion, individual DenseNet121 classifiers were trained on the data of Modality 1 and Modality 2 separately, and the output of the two modalities was combined using logical decisions – OR and AND. With the OR gate used in the late fusion approach, the highest accuracy (97%) was obtained, which illustrates effectiveness of multi-modality and the decision fusion procedure in evaluating gravel road condition [

48].

F. Mining and Minerals

Liang et al. (2024), improved geohazard prediction in underground mining operations, by combining CAD-based visual models with interpolated rock mass rating (RMR) data to address the sparsity and improve spatial predictions. By aligning diverse datasets, the model improved spatial connections, thereby improving prediction accuracy for hazards caused by geological factors like rock quality and stress. Applying machine learning models (neural networks, SVMs, KNNs), the framework was validated across multiple data combinations, showing significant improvements in prediction accuracy and reduced false negatives. This work advances the use of multi-modal deep learning for mining, offering a scalable solution for environments where data sparsity hinders effective hazard prediction [

52]. In the study by Li et al (2024) present a new conceptual framework, which enables the prediction of equipment failures in mining robots. The model includes long short-term memory (LSTM) networks with deep fusion neural networks (DFNN) as well as spatiotemporal attention networks (STAN), which are all aimed at enhancing the multi-modal time series data comprising sensor, image, and sound more efficiently. The LSTM network extends the memory of the model and helps capture long-range relationships, whereas DFNN integrates information from multiple heterogeneous data, and STAN further specialises in spatiotemporal integration. From the experimental results, one can state that using the model enhanced the accuracy of upcoming failure predictions, giving more effective outcomes than the traditional techniques on metrics such as MAE, MAPE, RMSE, and MSE, as well as decreased computational complexity. The model presents a good solution for predictive maintenance in complex mining operations [

53].

Table 3.

INTERESTING APPLICATIONS OF MULTI-MODAL DEEP LEARNING.

Table 3.

INTERESTING APPLICATIONS OF MULTI-MODAL DEEP LEARNING.

| Year |

Modalities |

Application |

Base Model |

References |

| 2024 |

CAD-based Images, interpolated rock mass rating (RMR) data |

Mining |

neural networks, SVMs, KNNs |

[52] |

| 2024 |

sensor, image, and sound data |

Mining |

LSTM, STAN |

[53] |

| 2024 |

MRI, CT, and PET |

Medical Imaging |

CNN |

[21] |

| 2024 |

MRI, Text |

Medicine |

CNN, SVR |

[34] |

| 2024 |

Medical images, genomics and clinical data |

Medicine |

CNN, ResNet |

[21] |

| 2024 |

Image, LIDAR |

Autonomous Systems |

CNN |

[37] |

| 2022 |

IR image, Visible image |

Robotics |

CNN |

[24] |

| 2023 |

Image |

Robotics |

CNN, RNN |

[38] |

| 2017 |

Video, Audio |

NLP |

CNN, LSTM |

[49] |

| 2024 |

Image, text |

NLP |

CNN, LRM |

[41] |

| 2024 |

Images, Time Series data |

Remote Sensing |

ResNet |

[42] |

| 2024 |

Image, Weather Data |

Remote Sensing |

CNN, Ensemble |

[44] |

| 2024 |

Text, Image |

Social media |

RoBERTa, ViT |

[50] |

| 2024 |

Text, Image |

Sentiment analysis |

DAE, CNN |

[28] |

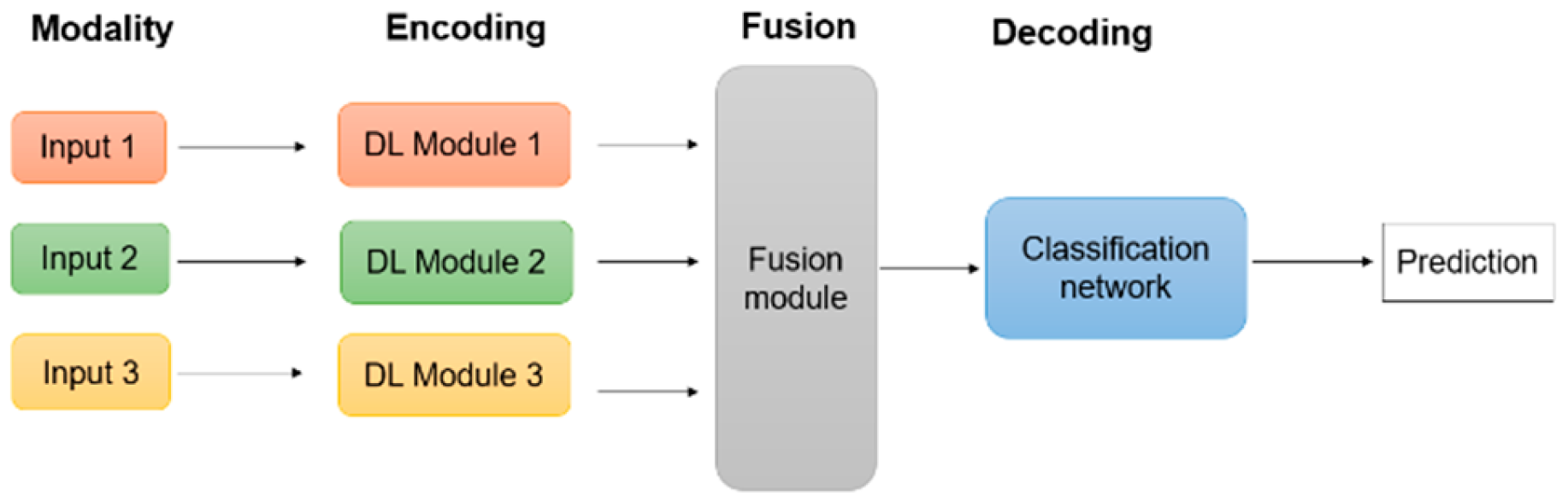

V. Encoding and Decoding in Multi-Modal Architectures

The success of multi-modal deep learning applications heavily relies on the option of encoding and decoding architectures, which change input information from various modalities into combined representations that can be jointly refined. Encoding describes the process of changing raw multi-modal data into hidden representations that record the crucial functions of each modality. Decoding includes restoring or analysing these hidden representations to accomplish the last preferred outcome, such as classifications, predictions, or generations [

54,

55]. In this way, the encoder-decoder system removes noise and extracts a computationally useful representation from the input. In multi-modal deep learning, as depicted in

Figure 5.1, encoding and decoding frameworks (e.g., a classification network) are vital since they enable the design to handle diverse data types in a unified fashion, protecting the distinct features of each modality while making it possible to combine and analyse the combined data reliably [

55]. This chapter will examine the various encoders and decoders employed in MMDL analysis.

A. Encoding Architectures in Multi-Modal Models

Encoders are accountable for extracting significant features from raw multi-modal inputs; their design is fundamental to any multi-modal deep learning model. Each modality typically has a specialised encoder in multi-modal applications that fits its unique attributes [

14]. For example, convolutional neural networks (CNNs) generally encode visual inputs such as images and videos. In contrast, recurrent neural networks (RNNs) [

56] and transformers process sequential data, such as audio or text [

32]. CNNs are specifically practical for visual information, where spatial patterns and ordered attributes are very important [

25]. At the same time, transformers and RNNs catch temporal dependencies in audio and text data by learning sequential patterns across time [

28]. In multi-modal deep learning, various encoder networks are commonly utilised in parallel to process each modality individually, creating modality-specific embeddings. The model then incorporates these embeddings via concatenation or even more advanced fusion techniques like attention mechanisms [

57]. For example, Tsai et al. (2018) utilised transformers as encoders in their multi-modal design to find hidden representations that catch connections between modalities, enhancing performance on tasks including language, video, and audio inputs. This encoding configuration is especially beneficial for tasks where each modality offers complementary information, as in video clip captioning, where visual and auditory signals are essential for comprehending context.

B. Decoding in Multi-Modal Architectures

The decoders efficiently transform hidden representations into transparent and interpretable outcomes. In multimodal tasks, decoders are attentively designed to resolve output requirements [

14]. For example, they can produce detailed messages in video clip inscribing, precisely identify feelings, or develop reasonable pictures in visual question answering (VQA) [

58]. Decoders are designed to work alongside encoders, creating an effective encoder-decoder network [

56]. This network enables the model to capture critical features during encoding and analyse them accurately during decoding. This specific approach increases the system’s overall efficiency and enhances every experience [

11]. Sequence- and transformer-based decoders are helpful for tasks that involve generating output sequences, like speech-to-text translation. Whereas convolutional decoders are essential for spatial reconstruction tasks, such as image classification. This demonstrates their versatility across various applications.

Cross-attention mechanisms are a substantial enhancement in multi-modal decoding [

59]. These mechanisms permit the model to concentrate precisely on aspects of the input embeddings and the most pertinent parts from each modality. Cross-attention mechanisms focus selectively on parts of an image or specific expressions in a text, permitting the decoder to create all-natural and contextually appropriate outcomes that utilise information from diverse modalities. Cross-attention mechanisms are essential throughout the decoding stage, especially in applications such as Visual Question Answering (VQA) and image captioning. They considerably improve the model’s capacity to properly incorporate and comprehend intricate visual and textual details [

49].

C. Encoder-Decoder Architectures for Translation and Alignment

Encoder-decoder models are vital not just for creating outputs but likewise for translating and aligning modalities. For example, an encoder-decoder setup promotes this transformation in applications like video-to-text translation or speech recognition, where one modality is mapped directly to another. Srivastava and Salakhutdinov (2012) showed the efficiency of deep Boltzmann machines in encoding visual features that can be converted into text, establishing a criterion for cross-modal translation tasks. Ngiam et al. (2011) highlighted the possibility of deep learning models in performing this translation with multi-modal deep autoencoders align embeddings across modalities by mapping them into a shared latent space. Alignment is crucial in tasks where the modalities provide time-synchronized information streams, such as video and audio evaluations. Multi-modal models commonly integrate recurring decoders or transformers for this objective, as they can catch long-range dependencies and align information over time. As an example, Lei et al. (2020) made use of reoccurring decoders to catch consecutive dependencies in audio-visual datasets for video question answering, while transformers are commonly used in tasks that need context-aware alignment across long sequences [

11].

Although encoding-decoding in architectures have proven reliable in multimodal applications, several challenges remain. Among the main obstacles is establishing encoding and decoding techniques that properly incorporate modality-specific attributes without shedding vital details remains an active area of research [

1]. An additional area of recurring study is the exploration of transformers and self-attention mechanisms as elemental encoders and decoders for multi-modal tasks, looking at their success in NLP coupled with current adaptation to vision and audio tasks. These architectures can enhance cross-modal alignment coupled with translation by dynamically concentrating on one of the most pertinent types of information. However, they feature high computational costs. Future studies should focus on establishing extra reliable, lightweight variations of these architectures that can be deployed in real-time systems and applications.

VI. Summary and Conclusions

This survey examined multimodal deep learning, emphasising core concepts, research, applications, challenges, and prospects. Multimodal deep learning has proven valuable in various applications, such as healthcare, autonomous systems, natural language processing, and environmental monitoring. Models incorporating data from multiple modalities are likely to be more effective, robust, and suitable, as they can make context-based judgements in complex real-world scenarios. The study also pinpointed several critical issues that must be tackled if the area is to progress in the future. These include the need for more effective techniques for representing and fusing heterogeneous data. Incorporating multi-modal data into a single deep learning framework would also help address these issues.

Recent advances in multimodal deep learning have enabled its application to different problem areas, including healthcare and medical image analysis, autonomous systems and robotics. The mining industry generates diverse data types, such as geological information, environmental factors, mechanical systems, video data, and logs. These data streams usually represent different modalities and are typically analysed separately. The mining industry has not fully explored this field, representing a crucial gap for further research.

The conclusions of this review are relevant to the further advancement of the field of multi-modal deep learning. First, more efforts are needed to develop unified approaches capable of tackling various challenges in multi-modal learning. These models will not only help reduce the development time but will also enhance the efficacy of multi-modal models. In addition, the same could be said of applying self-supervised techniques and transformer architectures in multi-modal learning. Existing improvements in multi-modal deep learning have considerably enhanced its efficiency in countless domains, including healthcare, medical imaging, and robotics. Nonetheless, the mining industry has not yet fully explored the possible applications of this technology. Only two studies can be attributed to the applications of multi-modal deep learning in the mining industry, showing a considerable research gap that necessitates further investigation. This work aims to resolve that gap, an effort that will form the basis for the future of this work.

Acknowledgment

A. A. Ahmed acknowledges the financial support of the Petroleum Technology Development Fund (PTDF), Nigeria.

Abbreviations and Acronyms

| ACNN |

Attention Convolutional Neural Network |

| AEBO |

Aquila EfficientNet-B0 |

| Bert |

Bidirectional Encoder Representations from Transformers |

| BiLSTM-AHCNet |

Bi-Directional Long Short-Term Memory assisted Attention Hierarchical Capsule Network |

| CBAM |

Convolutional Block Attention Module |

| CCA |

Canonical Correlation Analysis |

| cGANs |

Conditional Generative Adversarial Networks |

| CMFF |

Cross-Modal Feature Fusion |

| CNN |

Convolutional Neural Network |

| CT |

Computed Tomography |

| DAE |

Denoising Autoencoder |

| DBM |

Deep Boltzmann Machine |

| DECCFNet |

Dual Encoder-Based Cross-Modal Complementary Fusion Network |

| DFEM |

Deep Feature Extraction Module |

| DFNN |

Deep Fusion Neural Networks |

| DL |

Deep Learning |

| EAO |

Edge Attention Operation |

| GNN |

Graph Neural Network |

| GRU |

Gated Recurrent Unit |

| IOU |

Intersection Over Union |

| IR |

Information Retrieval |

| KNNs |

K-Nearest Neighbours |

| LIDAR |

Light Detection and Ranging |

| LRM |

Linear Regression Model |

| LSTM |

Long Short-Term Memory |

| MAE |

Mean Absolute Error |

| MAPE |

Mean Absolute Percentage Error |

| MBR |

Multi-Modal Bayesian Recommender |

| MDSC |

Multi-Direction Strip Convolution |

| MFDNN |

Multi-Modal Fusion Deep Neural Network |

| MFINet |

Multi-Modal Feature Interaction Network |

| MMDFC |

Multi-Modality Decision Fusion Classifier |

| MMDL |

Multi-Modal Deep Learning |

| MRI |

Magnetic Resonance Imaging |

| MSE |

Mean Squared Error |

| NAIP |

National Agriculture Imagery Program |

| NDVI |

Normalised Difference Vegetation Index |

| NLP |

Natural Language Processing |

| PCA |

Principal Component Analysis |

| PET |

Positron Emission Tomography |

| RBM |

Restricted Boltzmann Machine |

| ResNet |

Residual Network |

| RMR |

Rock Mass Rating |

| RMSE |

Root Mean Squared Error |

| RNN |

Recurrent Neural Network |

| RoBERTa |

Robustly Optimized Bert Approach |

| SAR |

Synthetic Aperture Radar |

| STAN |

Spatiotemporal Attention Networks |

| SVMs |

Support Vector Machines |

| TwinCNN |

Twin Convolutional Neural Network |

| ViT |

Vision Transformer |

| VQA |

Visual Question Answering |

References

- Baltrusaitis, T.; Ahuja, C.; Morency, L.P. Multimodal Machine Learning: A Survey and Taxonomy. IEEE Trans Pattern Anal Mach Intell 2019, 41, 423–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Akkus, C.; et al. Multimodal Deep Learning. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2301.04856. [Google Scholar]

- Lu, X.; Xie, L.; Xu, L.; Mao, R.; Xu, X.; Chang, S. Multimodal fused deep learning for drug property prediction: Integrating chemical language and molecular graph. Comput Struct Biotechnol J 2024, 23, 1666–1679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ngiam, J.; Khosla, A.; Kim, M.; Nam, J.; Lee, H.; Ng, A.Y. Multimodal Deep Learning. 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Tian, H.; Tao, Y.; Pouyanfar, S.; Chen, S.C.; Shyu, M.L. Multimodal deep representation learning for video classification. World Wide Web 2019, 22, 1325–1341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pawłowski, M.; Wróblewska, A.; Sysko-Romańczuk, S. Effective Techniques for Multimodal Data Fusion: A Comparative Analysis. Sensors 2023, 23, 2381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, B.; Zhou, R.; Ahmed, F. Multi-modal Machine Learning in Engineering Design: A Review and Future Directions. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2302.10909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pei, X.; Zuo, K.; Li, Y.; Pang, Z. A Review of the Application of Multi-modal Deep Learning in Medicine: Bibliometrics and Future Directions. Int J Comput Intell Syst 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, P.P.; Zadeh, A.; Morency, L.-P. Foundations and Trends in Multimodal Machine Learning: Principles, Challenges, and Open Questions. arXiv 2022, arXiv:2209.03430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, P.P.; Zadeh, A.; Morency, L.-P. Foundations and Trends in Multimodal Machine Learning: Principles, Challenges, and Open Questions. arXiv 2022, arXiv:2209.03430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsai, Y.-H.H.; Liang, P.P.; Zadeh, A.; Morency, L.-P.; Salakhutdinov, R. Learning Factorized Multimodal Representations. arXiv 2018, arXiv:1806.06176. [Google Scholar]

- Guo, W.; Wang, J.; Wang, S. Deep Multimodal Representation Learning: A Survey. IEEE Access 2019, 7, 63373–63394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, W.; Wang, J.; Wang, S. Deep Multimodal Representation Learning: A Survey. IEEE Access 2019, 7, 63373–63394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Ramesh, P.; Chitta, R.; Madhvanath, S.; Bernal, E.A.; Luo, J. Deep Multimodal Representation Learning from Temporal Data. arXiv 2017, arXiv:1704.03152. [Google Scholar]

- Pham, H.; Liang, P.P.; Manzini, T.; Morency, L.-P.; Póczos, B. Found in Translation: Learning Robust Joint Representations by Cyclic Translations Between Modalities. 2019. Available online: www.aaai.org.

- Jia, N.; Zheng, C.; Sun, W. A multimodal emotion recognition model integrating speech, video and MoCAP. Multimed Tools Appl 2022, 81, 32265–32286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Xie, Y. BCRA: bidirectional cross-modal implicit relation reasoning and aligning for text-to-image person retrieval. Multimed Syst 2024, 30, 177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karpathy, A.; Fei-Fei, L. Deep Visual-Semantic Alignments for Generating Image Descriptions. arXiv 2014, arXiv:1412.2306. [Google Scholar]

- Ma, Z.; Zhang, H.; Liu, J. MM-RNN: A Multimodal RNN for Precipitation Nowcasting. IEEE Transactions on Geoscience and Remote Sensing 2023, 61, 4101914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kline, A.; et al. Multimodal machine learning in precision health: A scoping review. npj Digital Medicine 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- S. K.B, S.; et al. An enhanced multimodal fusion deep learning neural network for lung cancer classification. Systems and Soft Computing 2024, 6, 200068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stahlschmidt, S.R.; Ulfenborg, B.; Synnergren, J. Multimodal deep learning for biomedical data fusion: A review. Brief Bioinform 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, M.; Gueaieb, W.; El Saddik, A.; Kwon, S. MSER: Multimodal speech emotion recognition using cross-attention with deep fusion. Expert Syst Appl 2024, 245, 122946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alabdulkreem, E.A.; Sedik, A.; Algarni, A.D.; Banby, G.M.E.; El-Samie, F.E.A.; Soliman, N.F. Enhanced Robotic Vision System Based on Deep Learning and Image Fusion. Computers, Materials and Continua 2022, 73, 1845–1861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hosseini, S.S.; Yamaghani, M.R.; Arabani, S.P. Multimodal modelling of human emotion using sound, image and text fusion. Signal Image Video Process 2024, 18, 71–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; et al. Multimodal Sensing for Depression Risk Detection: Integrating Audio, Video, and Text Data. Sensors 2024, 24, 3714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choudhari, A.; Bhoyar, D.B.; Badole, W.P. International Journal of INTELLIGENT SYSTEMS AND APPLICATIONS IN ENGINEERING MFMDLYP: Precision Agriculture through Multidomain Feature Engineering and Multimodal Deep Learning for Enhanced Yield Predictions’. Available online: www.ijisae.org.

- Kusal, S.; Panchal, P.; Patil, S. Pre-Trained Networks and Feature Fusion for Enhanced Multimodal Sentiment Analysis. In Proceedings of the 2024 MIT Art, Design and Technology School of Computing International Conference, MITADTSoCiCon 2024, Pune, India, 25–27 April 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, N.M.; Sharma, S.K. An efficient automated multi-modal cyberbullying detection using decision fusion classifier on social media platforms. Multimed Tools Appl 2024, 83, 20507–20535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dixit, C.; Satapathy, S.M. Deep CNN with late fusion for real time multimodal emotion recognition. Expert Syst Appl 2024, 240, 122579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srivastava, N. Deep Learning Models for Unsupervised and Transfer Learning. 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Ko, K.K.; Jung, E.S. Improving Air Pollution Prediction System through Multimodal Deep Learning Model Optimization. Applied Sciences 2022, 12, 405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaafar, N.; Lachiri, Z. Multimodal fusion methods with deep neural networks and meta-information for aggression detection in surveillance. Expert Syst Appl 2023, 211, 118523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Tachimori, H.; Yamaguchi, H.; Sekiguchi, A.; Li, Y.; Yamashita, Y. A multimodal deep learning approach for the prediction of cognitive decline and its effectiveness in clinical trials for Alzheimer’s disease. Transl Psychiatry 2024, 14, 105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, W.; Zeng, X.; Li, Q.; Gao, M.; Zhou, H.; Shi, J. CT and MRI image fusion via multimodal feature interaction network. Network Modeling Analysis in Health Informatics and Bioinformatics 2024, 13, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oyelade, O.N.; Irunokhai, E.A.; Wang, H. A twin convolutional neural network with hybrid binary optimizer for multimodal breast cancer digital image classification. Sci Rep 2024, 14, 692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Y.; Meng, S.; Wang, H.; Liu, J. Deep learning based object detection from multi-modal sensors: an overview. Multimed Tools Appl 2024, 83, 19841–19870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ichiwara, H.; Ito, H.; Yamamoto, K.; Mori, H.; Ogata, T. Modality Attention for Prediction-Based Robot Motion Generation: Improving Interpretability and Robustness of Using Multi-Modality. IEEE Robot Autom Lett 2023, 8, 8271–8278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Xu, X.; Xie, J.; Li, P.; Wei, J.; Sang, Y. FDENet: Fusion Depth Semantics and Edge-Attention Information for Multispectral Pedestrian Detection. IEEE Robot Autom Lett 2024, 9, 5441–5448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zadeh, A.; Chen, M.; Poria, S.; Cambria, E.; Morency, L.-P. Tensor Fusion Network for Multimodal Sentiment Analysis. arXiv 2017, arXiv:1707.07250. [Google Scholar]

- He, J.; et al. Multi-modal Bayesian Recommendation System. In Proceedings of the IMCEC 2024 - IEEE 6th Advanced Information Management, Communicates, Electronic and Automation Control Conference, Chongqing, China, 24–26 May 2024; pp. 141–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, H.; Chen, X.; Wang, Z.; Chen, X.; Dong, F. A Multi-Modal Deep-Learning Air Quality Prediction Method Based on Multi-Station Time-Series Data and Remote-Sensing Images: Case Study of Beijing and Tianjin. Entropy 2024, 26, 91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, B.; Liu, B.; Hou, B.; Wang, Z.; Yang, C.; Jiao, L. SwinTFNet: Dual-Stream Transformer With Cross Attention Fusion for Land Cover Classification. IEEE Geoscience and Remote Sensing Letters 2024, 21, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramzan, Z.; Asif, H.M.S.; Shahbaz, M. Multimodal crop cover identification using deep learning and remote sensing. Multimed Tools Appl 2024, 83, 33141–33159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, D.; et al. More Diverse Means Better: Multimodal Deep Learning Meets Remote-Sensing Imagery Classification. IEEE Transactions on Geoscience and Remote Sensing 2021, 59, 4340–4354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Zhou, Y.; Peng, P.; Wang, G. A Novel Multimodal Species Distribution Model Fusing Remote Sensing Images and Environmental Features. Sustainability 2022, 14, 14034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, H.; Wang, Z.; Du, B.; Dong, Y. A Deep Cross-Modal Fusion Network for Road Extraction With High-Resolution Imagery and LiDAR Data. IEEE Transactions on Geoscience and Remote Sensing 2024, 62, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saeed, N.; Alam, M.; Nyberg, R.G. A multimodal deep learning approach for gravel road condition evaluation through image and audio integration. Transportation Engineering 2024, 16, 100228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zadeh, A.; Chen, M.; Poria, S.; Cambria, E.; Morency, L.-P. Tensor Fusion Network for Multimodal Sentiment Analysis. arXiv 2017, arXiv:1707.07250. [Google Scholar]

- Shetty, N.P.; Bijalwan, Y.; Chaudhari, P.; Shetty, J.; Muniyal, B. Disaster assessment from social media using multimodal deep learning. Multimed Tools Appl 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Lu, Y.; Zhu, H. Multi-Modal Sentiment Analysis Based on Image and Text Fusion Based on Cross-Attention Mechanism. Electronics 2024, 13, 2069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, R.; et al. Multimodal data fusion for geo-hazard prediction in underground mining operation. Comput Ind Eng 2024, 193, 110268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Fei, J. Construction of Mining Robot Equipment Fault Prediction Model Based on Deep Learning. Electronics 2024, 13, 480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Majidi, S.; Babapour, G.; Shah-Hosseini, R. An encoder–decoder network for land cover classification using a fusion of aerial images and photogrammetric point clouds. Survey Review 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Livezey, J.A.; Glaser, J.I. Deep learning approaches for neural decoding across architectures and recording modalities. Briefings in Bioinformatics 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pham, H.; Liang, P.P.; Manzini, T.; Morency, L.-P.; Póczos, B. Found in Translation: Learning Robust Joint Representations by Cyclic Translations Between Modalities. 2019. Available online: www.aaai.org.

- Karpathy, A.; Joulin, A.; Fei-Fei, L. Deep Fragment Embeddings for Bidirectional Image Sentence Mapping. arXiv 2014, arXiv:1406.5679. [Google Scholar]

- Fukui, A.; Park, D.H.; Yang, D.; Rohrbach, A.; Darrell, T.; Rohrbach, M. Multimodal Compact Bilinear Pooling for Visual Question Answering and Visual Grounding. arXiv 2016, arXiv:1606.01847. [Google Scholar]

- Deng, L.; Fu, R.; Li, Z.; Liu, B.; Xue, M.; Cui, Y. Lightweight cross-modal multispectral pedestrian detection based on spatial reweighted attentionmechanism. Computers, Materials and Continua 2024, 78, 4071–4089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).