1. Introduction

Modifying additives are special chemicals used in lubricants to improve their properties and adapt them to specific working conditions. They enable greases to protect surfaces more effectively against wear, seizure, corrosion, high temperatures or extreme loads [

1,

2,

3].

Additives increase the wear and friction resistance of greases by preventing damage to metal surfaces, improve the lubricating properties of greases by reducing the coefficient of friction, resulting in a significant reduction in wear of machine and equipment components [

4,

5,

6]. The use of additives in lubricants increases the corrosion and oxidation resistance of the lubricated components, increases the adhesion of the lubricant to the surface, which prevents leaching. Another function of the additive is to adapt the grease to extreme working conditions such as high loads and high temperatures [

5,

6,

7,

8,

9].

The analysis of changes in the composition of the surface layer during contact between the lubricant and the elements of tribosystem is of great importance for lubrication efficiency [

10,

11,

12]. Elucidating the mechanism and establishing the kinetics of conversion under the influence of mechanical forcing and the catalytic interaction of the elements of the tribological system will enable the determination of the parameters of these processes and contribute to the optimisation of the composition of lubricants in order to obtain the desired lubricating properties [

13,

14,

15]. Finding a correlation between the type of active additive, changes in its structure as a result of tribochemical reactions occurring under mechanical and thermal excitations will contribute to identifying the mechanism of these interactions and determining the optimum conditions for this proces [

16,

17,

18]. A lubricating greases in the vicinity of machine components forms a separate near-surface phase called a boundary layer. When a lubricant is within the range of the surface forces of the machine elements, the interaction of these forces results in a greater ordering of the components of the lubricants, which is associated with an increase in intermolecular interactions between the lubricant composition and the elements of tribosystem [

19,

20,

21,

22,

23,

24]. As a result of these interactions, a boundary layer is formed, which prevents intensive wear and seizure processes. In order to effectively protect equipment components from excessive wear, it is necessary to know the characteristics of the changes occurring between the components of the lubricating composition and the surface of the tribosystem [

25,

26,

27,

28].

The general principles describing the interactions between lubricant components and trbosystem elements have been described with the use of model substances of relatively simple chemical composition, while the examination of boundary layers as a result of the interaction of actual components of lubricants, such as oils, thickeners and additives, may be an important contribution to the development of the scientific description of physicochemical processes to which lubricants are subjected in the tribological node [

29,

30]. Identifying the changes occurring in the surface layer of friction elements in the presence of lubricants will make it possible to extend the knowledge of the tribochemistry of processes affecting the formation of boundary layers during mechanical excitations acting on lubricant components [

31,

32,

33,

34,

35].

Finding the correlation between the structure of the surface layer, the lubricating properties of the lubricating compositions and the mechanical excitations will enable the use of such components that will increase the life of the tribosystem [

36,

37]. Controlling the processes affecting the properties of a lubricating composition can be achieved by using such thickeners or modifying additives containing active elements whose diffusion into the surface layer will increase wear resistance and influence the durability of steel-steel associations and improve tribological parameters such as wear resistance [

32,

36]. Lubricant components degrade under mechanical forcing and the resulting chemical compounds can be adsorbed onto the friction surface and form a boundary layer. A complete identification of the changes of lubricant components under the influence of mechanical forcing in frictional processes can only be realised by applying a system of complementary testing techniques [

31,

34,

36].

Products formed from waste biomass during pyrolysis processes are becoming increasingly important in lubricant production technology. The biochars thus formed can be used as additives to modify the functional properties, including tribological properties, of lubricants [

38,

39,

40]. The biochar additives can successfully replace previously popularly used additives such as amines, molybdenum disulphide or ZDDP. Therefore, the authors, taking into account the physicochemical properties of nut shells, decided to subject the shells to a pyrolysis process, and to introduce the obtained biochar into the structure of a lubricating greases in order to improve its lubricating properties [

41,

42,

43,

44].

Walnut shells have many properties that make them a valuable raw material in various fields, from natural medicine to industry. They contain juglone, which inhibits the growth of bacteria and fungi, and in the composition of walnut shells you can also find many antioxidants that protect against oxidation processes. They are used in cosmetics and in dyeing as a dye [

45,

46,

47]. They are a component of ecological plastics and biocomposites, and are also used to clean surfaces as an abrasive agent. In addition, walnut shells contain tannins, flavonoids and phenolic acids, which have antioxidant effects, as well as vitamins B, C, E, K and P and minerals, including zinc. In the aviation industry, they are used to clean jet engine turbines. Shells can also be used to produce biodegradable materials and composites that reinforce plastic [

48,

49,

50,

51].

Walnut shells are widely used in industry due to their hardness, biodegradability and rich chemical composition. They are also used in the production of light but durable materials, e.g. in the automotive industry [

52,

53]. It is a raw material for the production of medicines and supplements in antiparasitic preparations. They are often used as food additives or as a natural preservative. They are also used as natural filters for purifying water and fats in the food industry, and they also help remove unwanted substances from oils. They can be a component of biodegradable food packaging [

54,

55,

56].

According to available data, walnut production in Poland is around 6,800 tons per year [

57]. In the world, according to forecasts for the 2024/25 season, global walnut production is expected to increase by 2% to 2.7 million tons, mainly due to higher production in China, Chile and other countries [

58]. Shells constitute a significant part of the mass of a walnut, but the exact percentage may vary depending on the variety and growing conditions. It is assumed that shells constitute around 50–60% of the mass of the whole nut. Therefore, if we assume production at the level of 6,800 tons, around 3,400–4,080 tons are shells. Similarly, shells constitute around 1.35–1.62 million tons of the 2.7 million tons of nuts produced worldwide. One way to solve the problem of walnut shell disposal is the pyrolysis process.

Pyrolysis is a versatile method of converting biomass into valuable products, including energy, chemicals and materials. The process involves the decomposition of organic matter at high temperatures (300–900°C) in the absence of oxygen and in the presence of an inert gas, and its effects depend on the type of biomass and the desired products [

59]. Pyrolysis produces three main fractions: coal, bio-oil and syngas, which are used as solid fuel, chemical feedstock and renewable energy source, respectively. The quality and quantity of the products obtained depend on the composition of the biomass, including moisture, ash and volatile matter; for example, nutshells, due to their high carbon content and appropriate structure, can be a particularly valuable raw material [

42]. In the context of energy production, pyrolysis plays a key role as an alternative to fossil fuels. Bio-oil produced in this process can be further refined to act as a liquid fuel or chemical feedstock, contributing to the development of sustainable energy systems [

43].

In turn, the coal obtained in the pyrolysis process can be used both as a solid fuel and for carbon dioxide sequestration, which helps to reduce greenhouse gas emissions (reduction of gas emissions). Apart from energy, pyrolysis is used in waste management, especially in the conversion of agricultural residues and organic waste. This process reduces the volume of waste that would otherwise end up in landfills, thus supporting the circular economy [

60]. An example is the conversion of walnut shells into biochar, which allows for effective management of agricultural waste while obtaining valuable products [

61]. An important application of pyrolysis is also environmental remediation. Biochar produced in this process has excellent adsorption properties, which allows for its use in water and soil purification. An example is the use of pyrolytic products obtained from walnut shells for the adsorption of heavy metals, which effectively supports environmental purification processes [

62].

In addition, activated carbon obtained by pyrolysis is considered to be an effective agent in removing organic pollutants from wastewater [

63]. Biochar, obtained by pyrolysis of biomass, has also attracted much interest as a potential additive to lubricants due to its functional properties that can improve their performance in various applications. Addition of biochar to lubricants can lead to improved tribological and rheological properties, making it a valuable ingredient in the development of sustainable and environmentally friendly lubrication systems [

44].

An advanced version of this process is cascade pyrolysis, which allows for the maximum use of biomass through staged thermal decomposition at different temperatures and conditions. This approach allows for selective separation of components in individual phases, which increases the efficiency of the process and allows for more precise adjustment of the final products to various applications. Cascade pyrolysis is particularly useful in the production of high-quality bio-oils and coal with specific physicochemical properties [

64]. The efficiency of pyrolysis is largely dependent on the process parameters, such as temperature and residence time of the biomass in the reactor. Fast pyrolysis at high temperatures promotes the production of gas and bio-oil, while slower pyrolysis leads to a higher coal yield [

65]. Optimization of these parameters allows not only for increasing the efficiency of the process, but also for adjusting the characteristics of the obtained products to specific industrial and environmental applications.

The aim of this study was to investigate the effect of a biochar additive produced by pyrolysis from walnut shell biomass on the change on tribological and rheological properties of lubricants produced on the basis of vegetable oil, intended for use in the food industry, developed at the Lukasiewicz Resorach Network - Institute for Sustainable Technologies in Radom.

2. Materials and Methods

A series of model lubricating greases were developed using non-toxic ingredients as dispersion and dispersed phase [

66,

67,

68,

69]. Sunflower oil was used as the dispersing phase. The sunflower oil used to prepare of grease compositions was defined by the specific physicochemical parameters as follows 0.756 g/cm

3 density; 32.44 cSt kinematic viscosity at 40°C; 1.87 meq O

2/kg peroxide number; 113.34 g I

2/100 g of iodine index; 156.23 mg KOH/g of saponification index; and 1.43 mg KOH/g of acid index.

The Aerosil® type modified silica [

7,

9,

70] were used as dispersed phases. The base oil and thickener were mixed together using a high-speed homogeniser at room temperature at 18,000 rpm for 30 min. The prepared vegetable-based lubricating composition was modified by introducing a 1% and 5% modifying additive into its structure. As an additive that modifies the tribological and rheological properties of the grease, the authors decided to use biochar made from walnut shells produced during the pyrolysis process at 400

oC and 500

oC. For comparison, a biochar grease was used, where graphite with a grain size of less than 30 µm was used as an additive. The selected components, which were used to produce vegetable lubricants of the second consistency class. The consistency class of the produced lubricant compositions was tested in accordance with the requirements of the ISO 2137:2021 standard using a laser penetrometer produced by Lukasiewicz Research Network – Institute for Sustainable Technologies [

7,

9]. The prepared lubricating compositions were designated as follows: grease based on sunflower oil (grease A), base grease modified with 1% biochar added from walnut shells prepared at 400

oC (grease B), base grease modified with 5% biochar from walnut shells produced at 400

oC (grease C), a base grease modified with 1% biochar made from walnut shells at 500

oC (grease D), a base grease modified with 5% biochar made from walnut shells at 500

oC (grease E) and for comparison grease with graphite (grease F). All lubricating compositions produced were subjected to tribological and rheological tests, and the results obtained were statistically processed using Student’s t-test.

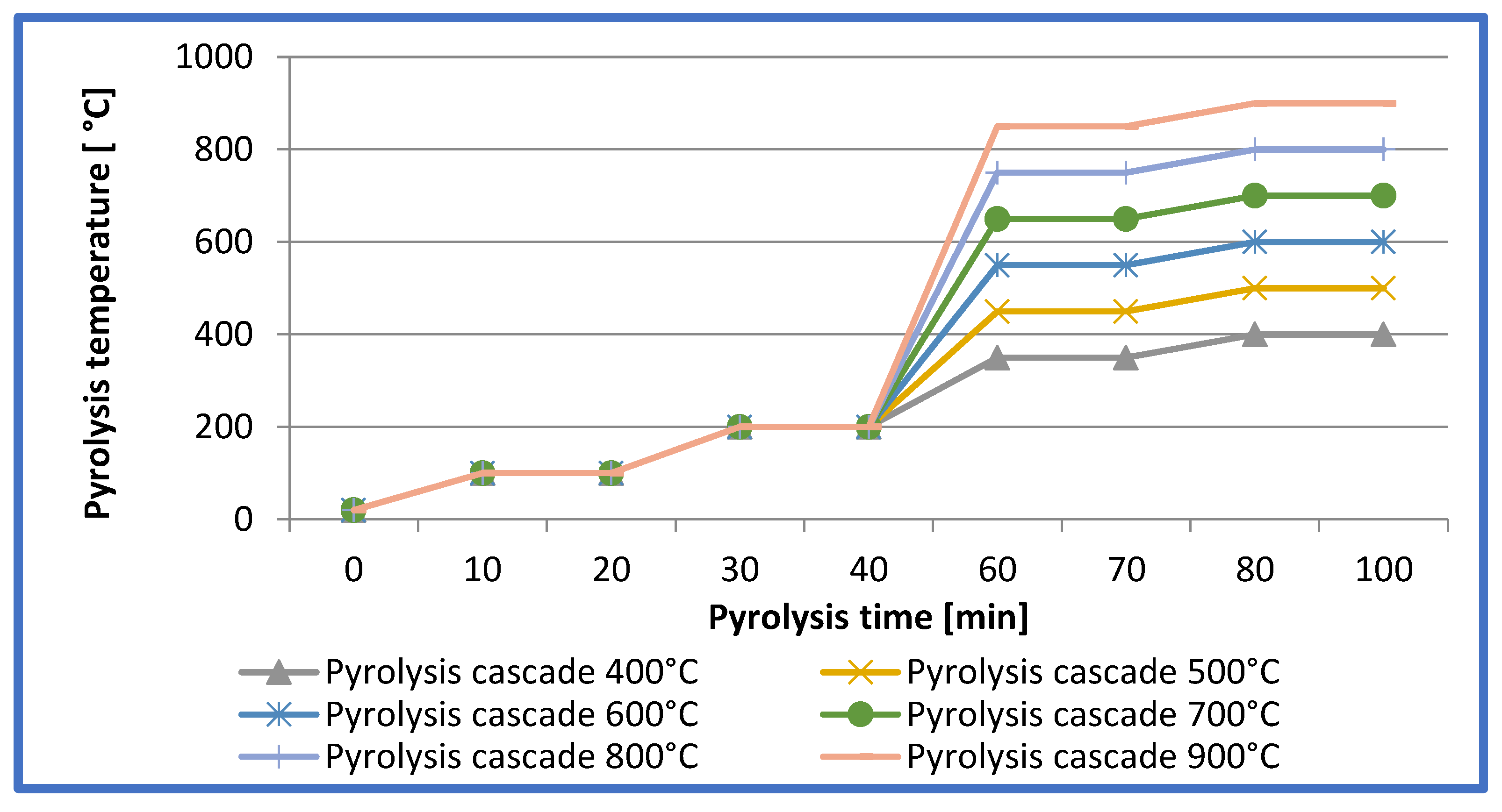

The walnut shells were pyrolysed over a temperature range of 400°C to 900°C using carbon dioxide (CO₂) as a protective atmosphere (

Figure 1).

The entire carbonisation process was carried out according to a cascade programme with four temperature stages. In the first stage, the temperature of the material was raised from 20°C to 100°C within 10 minutes and then maintained for a further 10 minutes. The second stage involved further heating to 200°C over 10 minutes, followed by a 10 minute stabilisation period. In the third stage, the temperature was increased to an initial level specific to the pyrolysis version: 350°C (for 400°C), 450°C (for 500°C), 550°C (for 600°C), 650°C (for 700°C), 750°C (for 800°C) and 850°C (for 900°C). The heating time in this stage was 20 minutes, followed by 10 minutes of holding. The fourth and final stage involved heating the material to a maximum temperature of 500°C, 600°C, 700°C, 800°C or 900°C depending on the process variant. It took 10 minutes to reach this temperature, which was then stabilised for 20 minutes. The entire process was carried out in a Czylok chamber furnace, model FCF-V12RM, with a continuous flow of CO₂ inert gas at 5 L/min. After pyrolysis, the samples were seasoned for 22 hours, during which time the gas flow was reduced to 2 L/min [

44].

Analysis of the Efficiency of the Pyrolysis Process

During the pyrolysis of walnut shells, the amount of biochar obtained decreases with increasing temperature, because at higher temperatures more organic components are decomposed and converted into gaseous products. At 400°C, the efficiency is 38.6%, and at 900°C it drops to 16.6%. This decrease is the result of more intensive thermal processes, which lead to greater mass loss in the form of gases. In the first phase of pyrolysis, already at temperatures below 200°C, water and light volatile compounds are removed. Then, in the range of 200–400°C, the decomposition of hemicellulose begins, which leads to the release of carbon dioxide, carbon monoxide and small amounts of hydrocarbons. At 400°C, the efficiency is highest, because most of the organic components still remain in solid form. In the range of 400–600°C, the decomposition of cellulose and initial decomposition of lignin begin, which causes further mass loss and a drop in efficiency to 29.5% at 600°C. At this stage, the amount of gaseous products, such as hydrogen and methane, increases, and the structure of biochars begins to take on a more aromatic character. After exceeding 600°C, lignin degradation is increasingly intensive, and at temperatures of 600–800°C, graphitization processes begin to dominate. Lignin, which is the most difficult component of biomass to decompose, gradually decomposes, which leads to a further decrease in efficiency to 21.3% at 800°C. In this temperature range, the amount of volatile products increases, such as hydrogen, carbon monoxide, aromatic hydrocarbons and tar fractions, which contribute to the loss of mass of the remaining material. Above 800°C, the pyrolysis process enters the final phase, in which further graphitization and removal of residual heteroatoms, mainly oxygen and hydrogen, occur. At 900°C the efficiency is only 16.6%, which means that most of the biomass has been converted into gaseous products. The structure of biochars becomes more and more ordered and resembles graphite, but it contains fewer reactive oxygen groups, which makes the material less chemically active but more thermally stable.

Tribological tests. A T-02 four-ball tester was used to determine the tribological properties of the tested lubricating compositions. A Nikon MM-40 optical microscope was used to determine the wear scar diameters of the test ball surfaces. The results obtained were used to determine G

oz/40 and p

oz values, i.e. to evaluate the anti-wear and anti-scuffing properties of the lubricating greases subjected to tribological tests [

71,

72]. The tribological properties of the tested lubricants were determined by measuring the limiting load of wear (G

oz/40) and limiting pressure of seizure (p

oz). The test specimens were 12.7 mm diameter balls made of ŁH 15 bearing steel, surface roughness Ra=0.32µm and hardness 60-65HRC. The limiting load of wear (G

oz/40) was measured when the friction node was loaded with a force of 392.4 N for the entire test duration of -3600 s and at a ball speed of 500 rpm according to the test conditions specified in WTWT-94/MPS-025 [

71].

The limiting load of wear is a parameter that measures the lubricant’s anti-wear properties. The measurement of this property was carried out by evaluating its value according to the equation:

where:

Pn–load of the tribosystem equal to 392.4 N,

doz-the diameter of the scars on the steel balls used for the test.

The measurement of the lubricating properties under scuffing conditions (i.e. under continuously increasing load during the test run) was carried out according to the methodology developed by SBŁ-ITeE. The test was performed with a linearly increasing load from 0 to 7200 N for 18 s at a spindle speed of 500 rpm and a load build-up rate of 409 N/s. When there is a sudden increase in frictional torque, the load level of the node is referred to as the scuffing load P

t [

72].

Measurements were performed until a limiting frictional torque of 10Nm or a maximum device load of 7200N was reached. This point was defined as the limiting load of scuffing P

oz [

72]. The arithmetic mean of at least three determinations not differing by more than 10% was taken as the final result. The Q-Dixon test was used to statistically process the results at the 95% confidence level.

The limiting pressure of seizure is a measure of the anti-scuffing properties of lubricants under scuffing conditions. The determination of this parameter consisted in calculating its value according to the formula: p

oz=0.52*P

oz/d

oz2, where P

oz is the limiting load of scuffing and d

oz is the diameter of the defect formed on the steel balls used in the test [

18,

19,

25,

73,

74].

Rheological tests. To determine the rheological properties of the tested lubricating composition, was used a compact MCR 102 rotational rheometer of the Anton Paar company with tribologicalcell T-PTD 200 with a concentric plate-ball contact point, in which three fixed cuboid steel plates were pressed with adequate force through a ball fixed in the spindle, rotating at the appropriate speed. The balls with a diameter of 12.7 mm and plates with dimensions of 15 × 5 × 2 mm were made of bearing steel LH 15 (Ra = 0,3 μm; hardness 60–63 HRC). During the tests, immersion lubrication was used. Rheological tests (measurement of viscosity) were carried out at the tribosystem at 10.00 N, rotational speed of 500 rpm, during 3600 s and temperature of 20

oC [

75].

Spectral tests. A confocal dispersive Raman NRS 5100 microspectrometer (Jasco Corporation, Japan) was employed to analyze the chemical composition of the lubricating greases. The spectrometer was equipped with a 532.12 [nm] excitation laser and a CCD detector. The instrument’s specifications included a diffraction grating with 600 [lines/mm], laser power of 5.2 [mW], a numerical aperture of 4000 [μm], a spectral range of 3700 to 100 [cm⁻¹], and a resolution of 4.2 [cm⁻¹]. The lens provided a magnification of 20x, and the exposure time for each measurement was set to 200 seconds. The samples were placed on glass slides for analysis [

76].

Fourier spectroscopy spectra were carried out with a Jasco FTIR 6200 spectrometer, in the reflection mode, using a Pike attachment with a diamond crystal, exposure time of 1 spectrum - 30 seconds, measurement range from 650 cm-1 to 4000 cm-1 during the test.

3. Results and Discussion

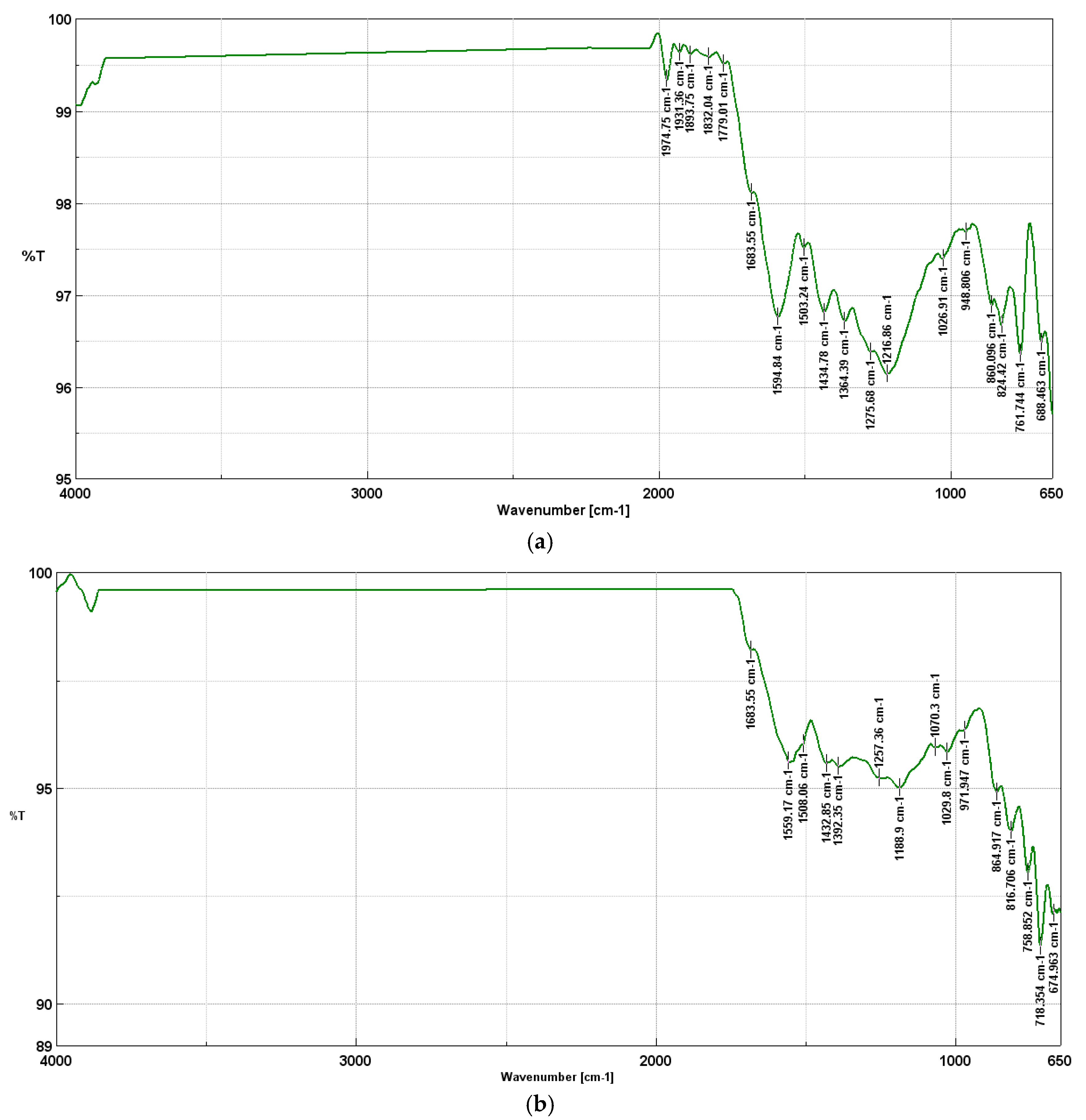

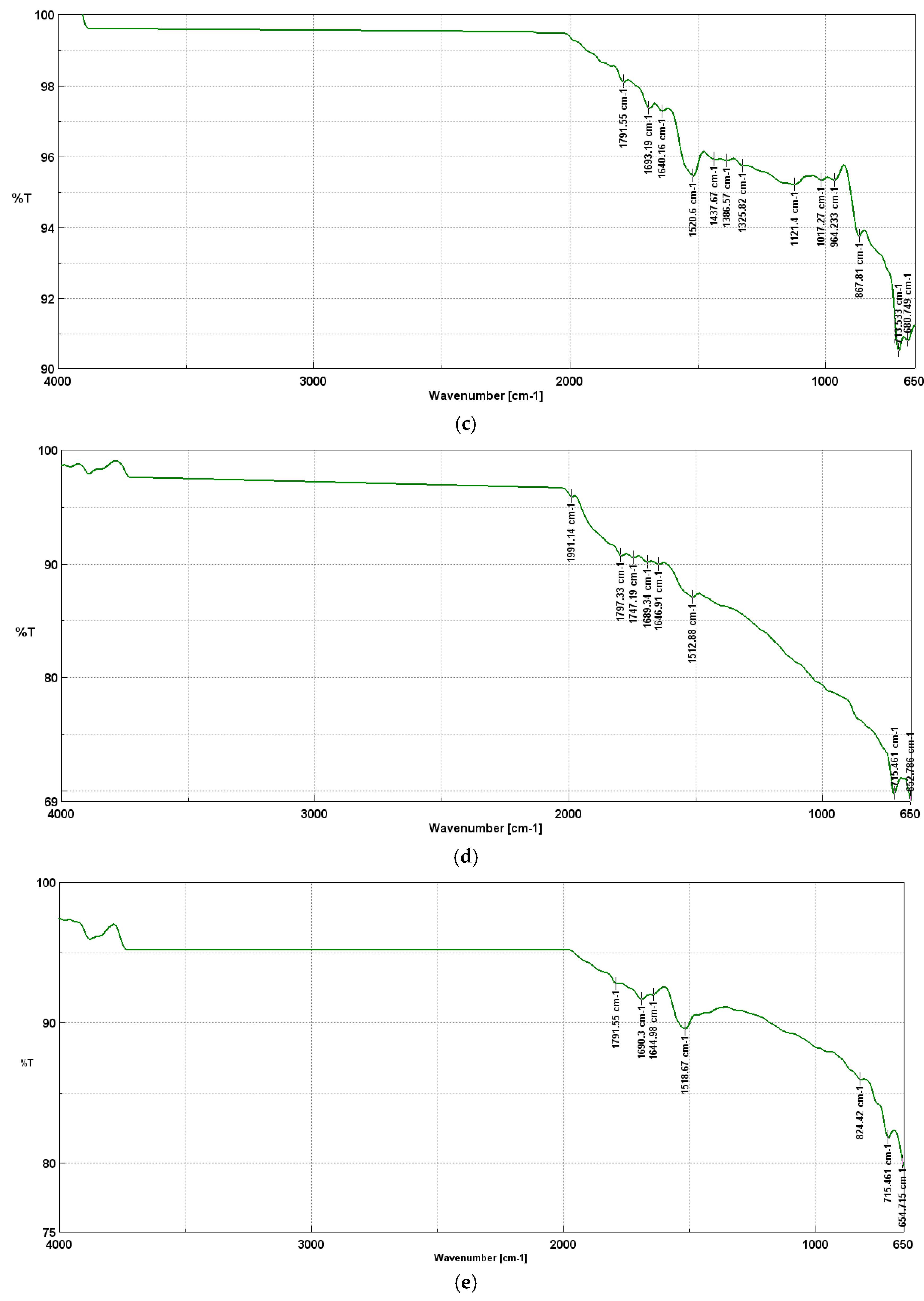

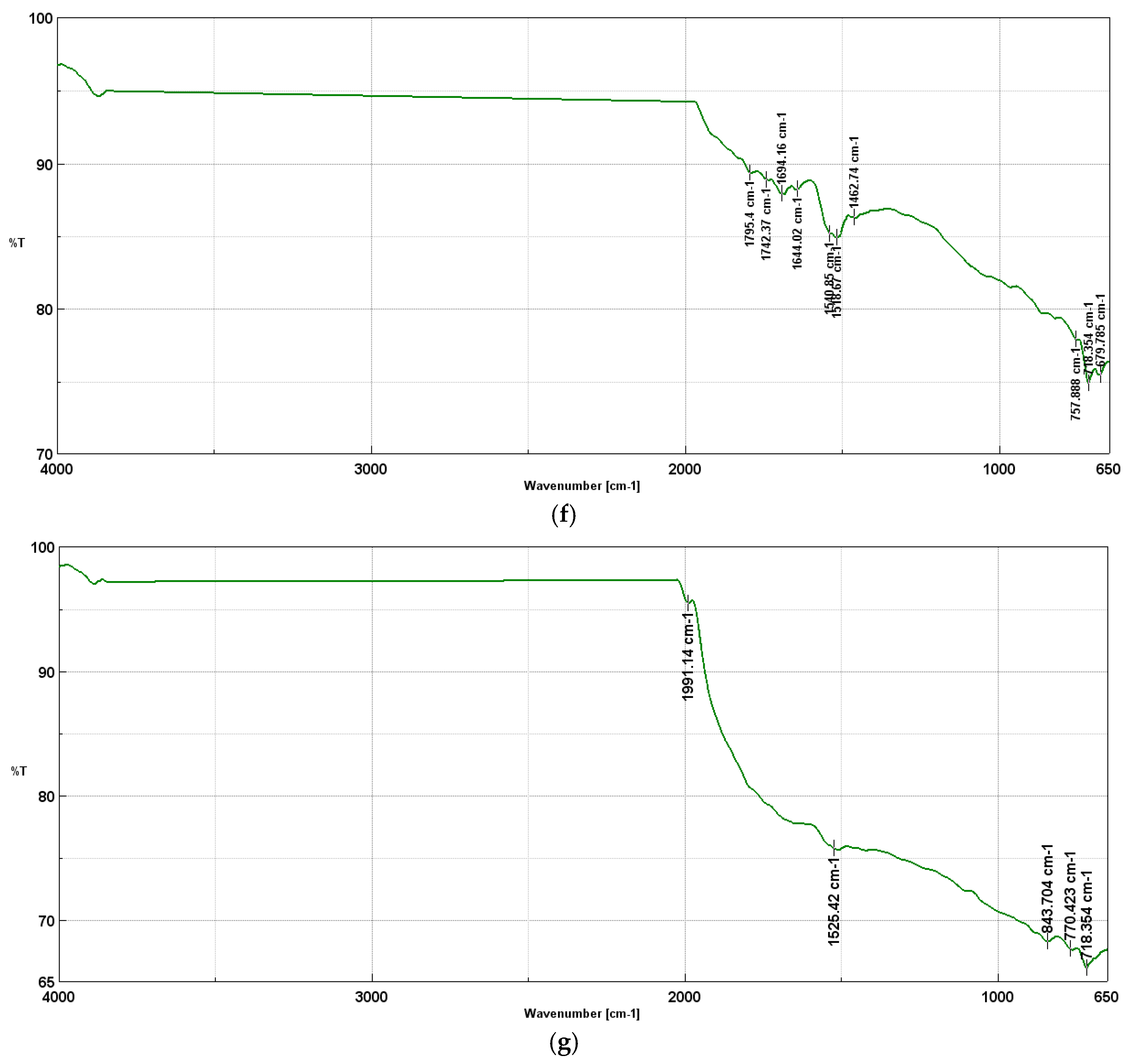

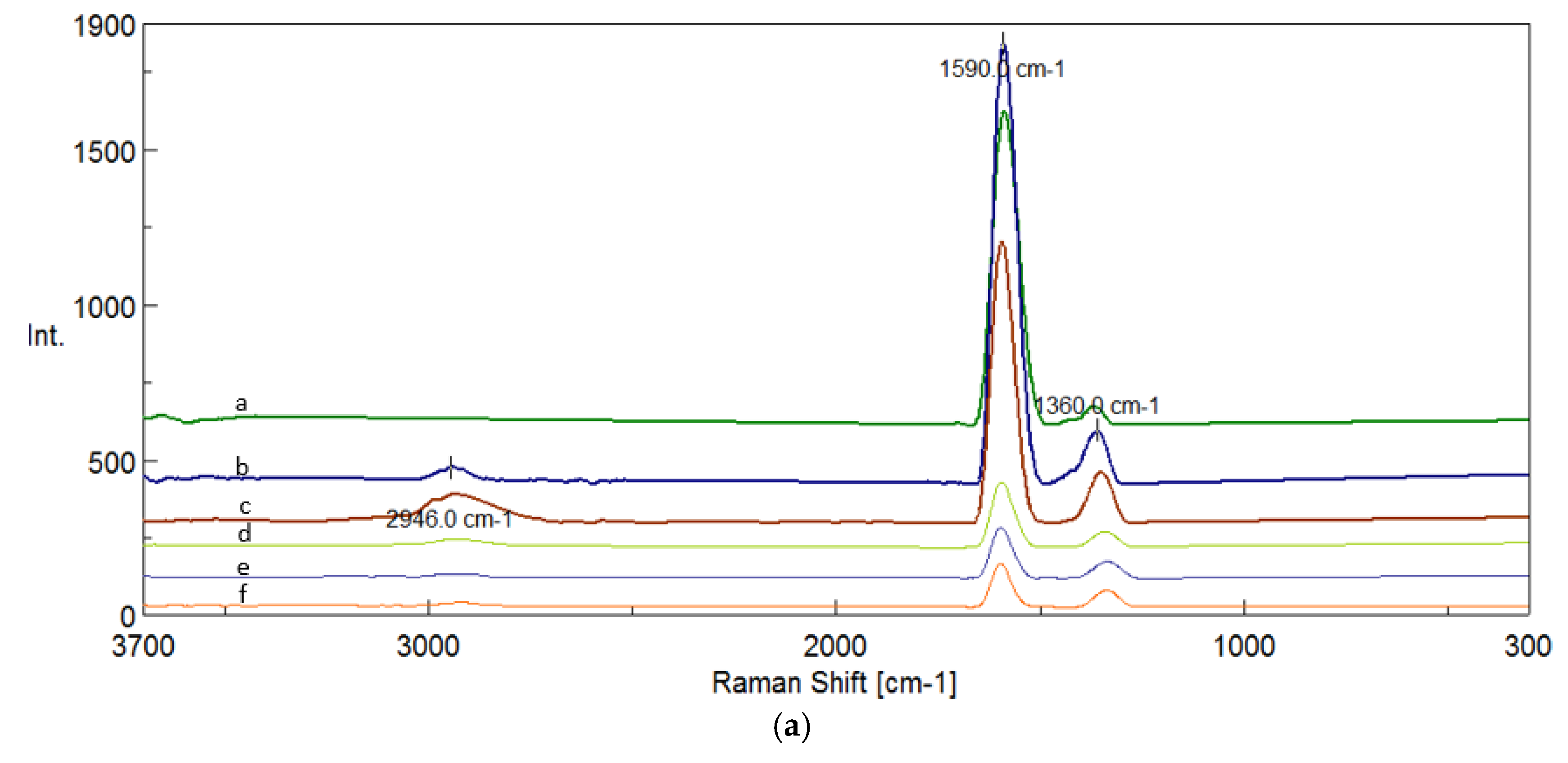

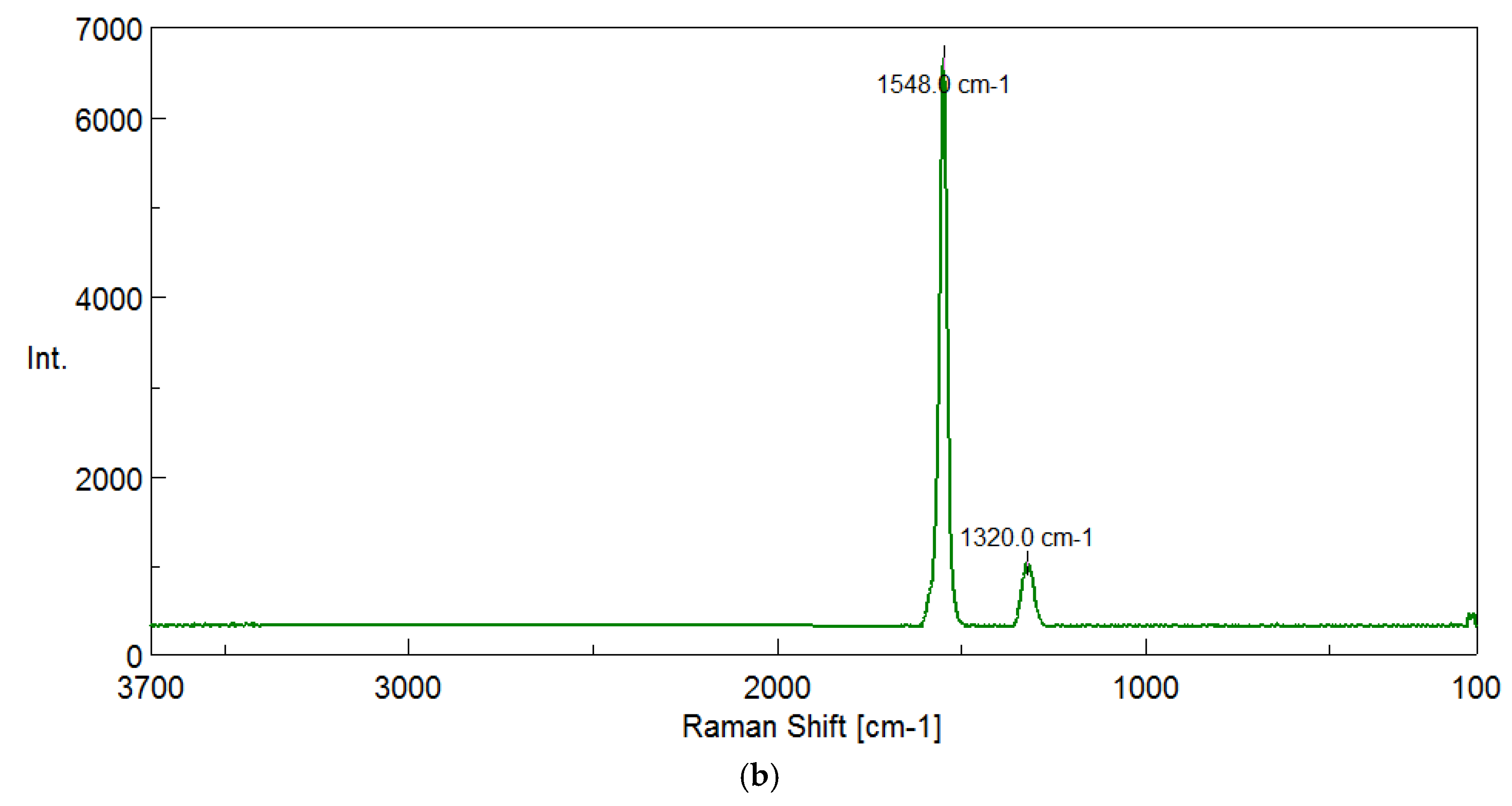

Spectral characteristic of biochar from walnut shell. The walnut shell before pyrolysis and after pyrolysis were presented in

Figure 2 and

Figure 3. The resulting pyrolysis biochars from walnut shells was subjected to spectral testing using Raman spectroscopy and FTIR spectroscopy to assess the chemical structure of the resulting biochar additives (

Figure 4a-g and

Figure 5a-b).

The results of the chemical structure of the biochar produced during pyrolysis process at 400

oC-900

oC of walnut shells and graphite using FTIR technique are shown in

Figure 4a-g.

FTIR spectroscopy allows for the analysis of functional groups present in biochars, which have a significant impact on their tribological properties, i.e. their ability to reduce friction and wear. Depending on the pyrolysis temperature, the chemical composition of biochars changes, which translates into their effectiveness as a lubricant component. A key aspect is oxygen groups, which affect the formation of protective lubricating layers that prevent surface wear. At 400°C, FTIR spectra show a high content of carbonyl groups (C=O) in the range of 1974–1893 cm⁻¹, which can come from ketones, esters and anhydrides. These groups can improve anti-seize and anti-wear properties by creating a stable lubricating layer. Additionally, the C=C band (~1683 cm⁻¹) indicates the presence of aromatic structures, and hydroxyl and ether groups (C-O in the range of 1275–1026 cm⁻¹) indicate high surface reactivity, which favors lubricating interactions.

A similar chemical composition is shown by biochars from the temperature of 500°C, in which carbonyl groups (~1683 cm⁻¹), aromatic groups (~1559 cm⁻¹) and C-O groups (~1257–1029 cm⁻¹) are still present. At this temperature, bonds C-H are also present in methyl and methylene groups (1432, 1392 cm-1), deformational bonds (C-H) in aromatic systems (971, 864 cm-1) and deformational bonds (C-H) out-of-plane in aromatic rings (816-674 cm-1).

Thanks to this, the material retains an appropriate number of active functional groups, which improve its ability to protect friction surfaces. As the pyrolysis temperature increases, above 600°C, the oxygen functional groups gradually degrade, which leads to a decrease in lubricating properties. FTIR spectra indicate that the C=C bands start to dominate (~1520 cm⁻¹ at 600°C), which means that the structure becomes more graphitized, and the number of reactive groups is reduced. Also present are the deforming bonds (C-H) in aromatic systems (867-680 cm-1), stretching bonds (C=O) in ketones and amides (1791-1640 cm-1), and bending bonds (C-H) in methyl and methylene groups (1325-1386 cm-1). In addition, the decrease in the intensity of the C-O bands in the range of 1200–1000 cm⁻¹ indicates the loss of phenolic and ether functional groups. Such a change means that biochars lose their ability to form a protective lubricating layer, which worsens their anti-wear and anti-seize properties.

During the pyrolysis of walnut shells at 700oC, the following are present the stretching bonds (C=O) in aromatic systems (aromatic quinones) at 1991 cm-1, stretching bonds (C=O) in ketones and amides (1747-1797 cm-1), stretching bonds (C=C) in aromatic rings at 1646-1689 cm-1, deformational bonds (C-H) in aromatic systems at 1512 cm-1 and deformational bonds (C-H) in aromatic systems at 715 and 652 cm-1.

However, at 800oC, the following are present the stretching bonds (C=O) in ketones and amides at 1791 cm-1, stretching bonds (C=C) in aromatic rings at 1644 and 1690 cm-1, deforming bonds (C-H) in aromatic systems at 1518 cm-1, deforming bonds (C-H) in aromatic systems at 824 cm-1 and deforming bonds (C-H) in aromatic systems at 715 and 654 cm-1.

At 900oC, the presence of the stretching bonds (C=O) in residual ketones at 1694-1795 cm-1, stretching bonds (C=C) in aromatic rings at 1644 cm-1, which means that the structure becomes more graphitized, and the number of reactive groups is reduced, deforming vibrations (C-H) in aromatic systems at 1518-1540 cm-1, bending vibrations (C-H) in aromatic groups at 1462 cm-1 and deforming vibrations (C-H) in aromatic rings (679-757 cm-1).

While, the following are present in graphite the deformational bonds (C-H) in highly ordered aromatic systems at 718 cm-1, deformational bonds (C-H) out-of-plane in graphitic systems at 770 cm-1, stretching bonds (C=C) in highly ordered in aromatic rings at 1525 cm-1 and stretching bonds (C=O) in residual carbonyl groups at 1991 cm-1.

Biochars obtained at temperatures of 400°C and 500°C were selected for tribological studies because they offer the best compromise between chemical activity and structural stability.

The results of the chemical structure of the biochar produced during pyrolysis process at 400

oC-900

oC of walnut shells and graphite using Raman spectroscopy are shown in

Figure 5a-b.

Raman spectroscopy allows us to determine how ordered the structure of biochars is and how many defects it contains. Two main bands can be distinguished in tested materials: the G band around 1590 cm⁻¹, which indicates a well-ordered graphite structure, and the D band around 1360 cm⁻¹, indicating the presence of defects and less organized fragments. At temperatures of 500°C and 600°C, an additional 2D band appears in the range of about 2946 cm⁻¹, which is associated with the formation of graphene layers and may indicate a more ordered structure of the material. To assess the degree of ordering of biochars, the ratio of the D band intensity to the G band (ID/IG) is analyzed. The lower its value, the more ordered the material. At 400°C, this ratio is 0.05, and at 500°C it increases to 0.12, which means that these materials are exceptionally well-ordered. In comparison, at 600°C the ratio is 0.18, and at higher temperatures it gradually increases to 0.23 at 700°C, 0.38 at 800°C and 0.44 at 900°C, indicating an increasing number of defects and a more chaotic structure. Interestingly, commercial graphite has an ID/IG ratio of 0.16, which means that biochars obtained at 400°C and 500°C may be even more ordered than graphite. Since more structured materials have better tribological properties, biochars formed at temperatures of 400°C and 500°C were selected for the production of the lubricant. Their low ID/IG ratio means fewer defects, which improves their lubricity and makes them behave similarly to graphite. Additionally, the presence of a 2D band at 500°C indicates the beginning of graphene layers formation, which can improve the stability of the structure and reduce friction. However, at temperatures above 600°C, the number of defects increases, making the material less favorable from a tribological point of view.

Two main bands can be distinguished in the graphite: the G-band at around 1550 cm-¹, which indicates a well-ordered structure, and the D-band around 1320 cm-¹, indicating the presence of defects and less-ordered fragments.

Table 1 shows all FTIR peaks and characteristic bonds for biochar produced during pyrolysis at 400

oC-900

oC and for graphite.

Tribological Tests

A measure of the anti-scuffing characteristics of the tested greases under scuffing operating regime is the limiting pressure of seizure p

oz. The experimental data determined for this parameter are presented in

Figure 6.

The obtained data of the limiting pressure of seizure indicated various degrees of anti-scuffing characteristics of the studied lubricating greases. In dependence on the quantity of biochar additive used, the level of the calculated factor poz characterized of anti-scuffing characteristics of the investigated lubricants has changed considerably. Introducing a modifying additive into the structure of sunflower grease in the form of biochar produced by pyrolysis at 400oC and 500oC from walnut shells. Modification of the vegetable grease with 1% biochar produced at 400oC from walnut shells increased the level of anti-seizure properties characterized by the poz parameter by 42%. Modification of vegetable grease with 5% biochar additive produced at 400oC did not show such favourable changes in the parameter in question in comparison to the base grease (increase in the parameter characterizing the anti-seizure properties by only 3%). In contrast, the addition of a walnut shell pyrolysis additive at 500 °C to the base grease showed that the positive effect of this additive was observed at higher additive concentrations. Modification of the vegetable grease with 1% biochar from nut shells produced at 500oC had an antagonistic effect on the anti-scuffing properties of tested lubricating compositions. In this case, an almost 16% decrease in the value of the poz parameter was achieved compared to the results obtained for the base grease without the modifying additive. Modification of sunflower grease with 5% of biochar additive produced during the pyrolysis process at 500oC showed a positive effect on the level of anti-scuffing properties of the tested lubricating composition. This amount of additive resulted in a 41% increase in the poz parameter compared to the results obtained for the base vegetable grease.

The use of biochar additive from walnut shells in vegetable greases was characterized by more effective anti-seizure effect than the use of graphite as a lubricating additive in vegetable greases. The poz parameter provides the information about the pressure prevailing in the friction zone at the moment of seizure. On the basis of the obtained test results, it can be concluded, that the use of a biochar additive made from walnut shells has a positive effect on the formation of highly resistant structures that effectively protect machine and equipment components from seizure. The incorporation of walnut shell biochar into the structure of the lubricant increases the resistance of the surface layer to seizure processes, and the nature of the lubricating film formed promotes a significant reduction in wear.

The biochar nut shell additive produced by pyrolysis is a typical EP additive introduced into a lubricant when very high friction pressures occur between cooperating surfaces. It forms a firmly adherent film on the metal surface by reacting with the layer of iron oxides adhering to the metal surface when high pressures and temperatures accompany the metal-metal friction processes. If the adherent layer of the additive is destroyed, it is rapidly reconstituted. The additive’s mechanism of action is based on the phenomenon of absorption of the biochar additive molecules in the thickener molecule, which attaches to the chain of the oil base to form structures resistant to seizure processes. The addition of biochar in the lubricant prevents excessive wear of mating surfaces and reduces the risk of seizure. The applied biochar additive can also act as a friction modifier. In the range of low sliding speeds, with insignificant specific pressures and low oil viscosity, fluid lubrication can easily change to mixed friction.

In order to prevent friction vibrations and scrapes and to reduce friction forces, substances are usually used that are effective at temperatures at which EP additives are not yet active, form single-molecule layers of physically adsorbed, oil-soluble additives and reduce friction through re-aggregated layers that have a significantly lower coefficient of friction than a typical oil without additives. Particularly important is the biochar additive, which belongs to the group of additives with a mechanical effect of great importance at moderate temperatures and pressures, where mixed friction occurs.

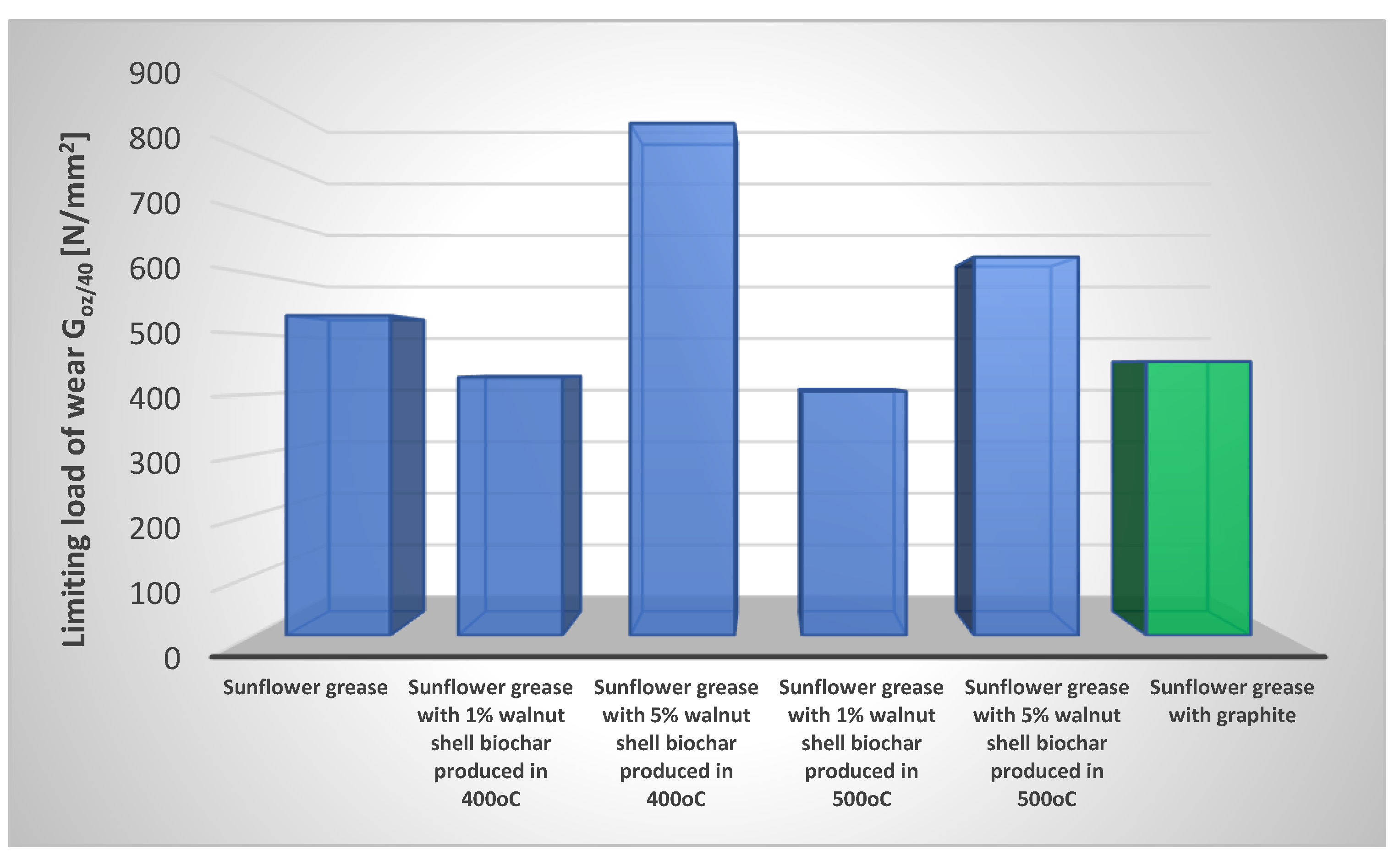

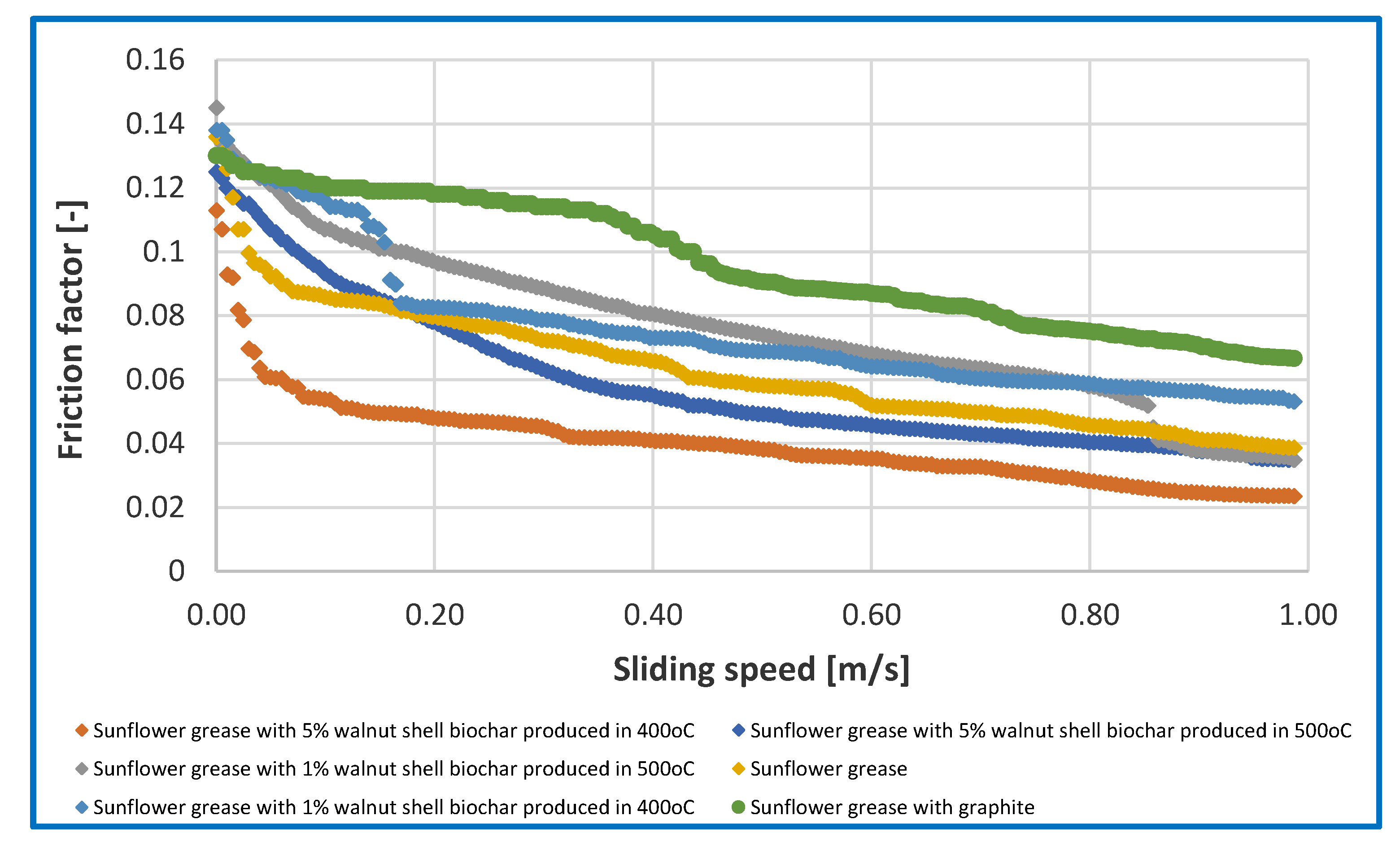

The anti-wear properties of the evaluated plant-based greases were validated by calculating the limiting load of wear, G

oz/40, of the tribological system lubricated with the assessed greases. The experimental data are presented in

Figure 7. The dependence of friction factor from sliding speed for tested greases were presented in

Figure 8.

Tribological tests at a constant friction node load of 392.4 N for produced vegetable greases modified with different amounts of biochar from walnut shells produced during pyrolysis process at 400oC and 500oC showed, that the used additive changes the ability of the greases to protect the friction node against wear.

The durability of the boundary layer was indicated by the wear index Goz/40. The higher index, the greater durability of the boundary layer and the reduction of wear. The sunflower oil-based vegetable grease had a Goz/40 parameter value of 530.82 N/mm2. Introducing 1% of walnut shell biochar produced at 400oC into the structure of the vegetable grease resulted in a significant reduction in the anti-wear protection of steel friction nodes by 19% in compared to the base grease without the modifier. On the other hand, increasing the concentration of the biochar additive in the lubricant to 5% resulted in a significant increase in the value of the parameter in question, which indicates the level of anti-wear properties. The value of the Goz/40 parameter for this composition was 849.85 N/mm2 and was 60% higher than the value of this parameter for the base grease, which indicates the positive effect of the used additive on the level of anti-wear protection of friction nodes lubricated with sunflower oil-based vegetable greases. Modification of the vegetable grease with a 1% of biochar additive made from nut shells during pyrolysis at 500oC did not produce positive results. In this case, a 24% decrease in the value of the Goz/40 parameter was observed, indicating a deterioration in the anti-wear protection of friction nodes lubricated with this composition. While, an increase in the concentration of the biochar additive produced at 500oC increased the value of the parameter in question characterising the level of anti-wear properties of the tested lubricating composition by 18.5%. The use of the biochar additive at a concentration of 5% showed an effective effect on improving the anti-wear properties of vegetable greases. Increasing the anti-wear protection of steel friction nodes after the use of biochar additives for vegetable greases is more effective than the use of graphite as an anti-wear additive. Lubricants modified with a minimum of 5% biochar additive are lubricants that effectively protect the friction node against wear under constant tribosystem load. Introducing a 1% of biochar additive made from nut shells into the structure of a vegetable grease increases the coefficient of friction in relation to the results for the base grease without the modifier. While, the introduction of a 5% of additive into the structure of the grease reduces the coefficient of friction of tested greases, indicating the effective protection of the friction node against wear.

The results show, that the biochar additives made from nut shells can be used as AW additives in vegetable-based greases, especially at higher additive concentrations in greases with vegetable oils as the oil base. The purpose of AW additives is to prevent excessive wear on cooperating friction surfaces and to reduce the coefficient of friction. Their mechanism of action is to form a permanent film of polar additive molecules on the metal surface. It adheres to the metal surface without forming permanent chemical bonds with it. The additive molecules form chemical bonds with the metal surface or are bound to the substrate by intermolecular van der Waals forces.

The adsorption mechanism of the polar AW additive molecules is that the upper part of the additive molecules attach to the metal particles, while the lower, hydrocarbon part is directed towards the oil, forming a so-called oil film. Both cooperating faces of the friction association are covered by such a tightly adherent film, which reduces the possibility of direct contact between their surfaces and thus reduces wear. The layer of additive particles forming on the cooperating metal surfaces, so-called oil film facilitates their mutual displacement, thus also reducing the coefficient of friction.

Tests of Rheological Properties of Lubricating Greases

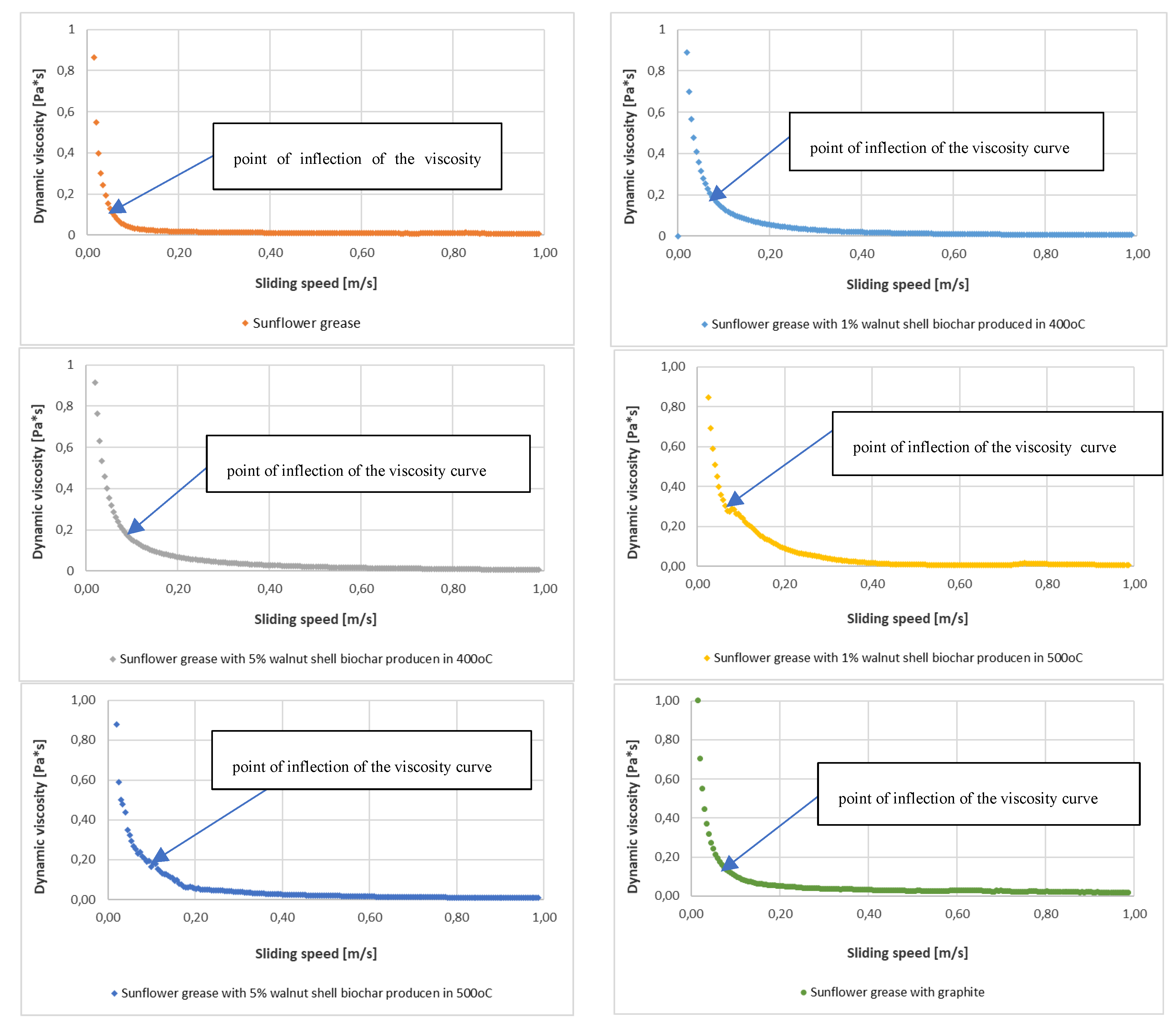

During tribological tests, the dynamic viscosity tests were carried out for lubricating compositions modified with different amounts of biochar additives. The dependence of dynamic viscosity on sliding speed is shown in

Figure 9.

For each tested lubricant, the dependence of dynamic viscosity on sliding speed was determined. The presented test results testify to changes in the tribological properties of the tested lubricating compositions. Based on the changes of dynamic viscosity, it is possible to predict what effect the introduced biochar additives have on the anti-wear properties of vegetable greases. The greatest changes in dynamic viscosity of the tested lubricants were observed at low sliding speeds up to 0.2 m/s.

The introduction of a biochar additive to sunflower grease produced by pyrolysis at 400oC and 500oC from nut shells changes the rheological properties of the biochar grease. Changes in the viscosity curve for grease B and grease D, in which 1% of the modifying additive was introduced, testify to the much weaker anti-wear properties of these compositions than for the base composition without the additive. In these cases, the inflection of the curve occurs at higher values of dynamic viscosity. While, for compositions C and E, the change in dynamic viscosity indicates better anti-wear protection of the friction node. In these two cases, the inflection of the viscosity curve occurs at lower dynamic viscosity values. On the other hand, the viscosity changes for grease F, which was modified with graphite, indicate the anti-wear properties fitting in between compositions modified with 1% of biochar additive and compositions modified with 5% of biochar additive. Thus, the level of anti-wear protection characterised by the Goz/40 parameter can be verified on the basis of changes in dynamic viscosity of the lubricants subjected to tribological tests.

The way in which the additive particles incorporate into the base oil chain is indicative of the level of rheological properties of biochar greases. The introduction of a minimum of 5% biochar additive causes the distance and bond strength between the oil, the thickener and the used additive to decrease, resulting in a stabilisation of the structure of the tested lubricants and an increased resistance to degradation due to shear forces.

4. Conclusions

Based on the results of the tests, it was found that the lubricating and rheological properties of the tested lubricating compositions changed significantly depending on the amount of the used modifying additive.

The tests were carried out on a four-ball apparatus at concentrated contact. Vegetable lubricating compositions containing 1 and 5 % of the modifying additive were analysed. The obtained results unequivocally confirmed the positive effect of used additive in the grease during friction of the steel tribosystems.

Determined values of the limiting pressure of seizure determining the anti-seizure properties in scuffing conditions showed, that the use of 1% biochar produced during pyrolysis at 400oC from nut shells and 5% of biochar produced at 500oC - as an modifying additive of tested lubricating compositions - most effectively influences on the change of anti-seizure properties of greases used in the experiment.

The use of the optimum amount of the modifying additive causes the formation of a low-friction surface layer on the steel surface, which is resistant to high unit loads, resulting in an increase in the durability and efficiency of many sliding associations.

Modification of vegetable plastic greases with biochar from nut shells contributes to improving their lubricating properties. The base oil (sunflower oil) used in the experiment interacts synergistically with the nut shell biochar, causing an increase in the indices describing the tribological properties of the tested lubricating compositions.

The introduction of nut shell biochar into the structure of the plastic grease as a modifying additive contributes to the formation of a protective film on the surface, which increases the resistance of the tribosystem to seizure. As a result of the improved boundary layer properties, the starting of scuffing occurs at higher loads on the friction node.

Under the influence of used modifier, especially at a concentration of 5%, there is an increase in the Goz parameter, which indicates a high resistance to boundary layer disruption. This indicates, that the used additive has a positive effect on improving the tribological characteristics of vegetable plastic greases.

The introduction of the biochar additive into the structure of the vegetable plastic grease causes a decrease in dynamic viscosity with an increase of sliding speed, which consequently leads to decrease of friction coefficient for greases modified with 5% biochar additive produced from nut shells, and an increase of the level of anti-wear protection of steel friction nodes lubricated with vegetable lubricating compositions having in their composition the biochar from nut shells produced during the pyrolysis process at 400oC and 500oC.