1. Introduction and Clinical Significance

Scimitar Syndrome is a rare congenital anomaly involving partial anomalous pulmonary venous return, most commonly affecting the right lung, with drainage into the inferior vena cava [

1]. It often becomes symptomatic during infancy or early childhood, and surgical correction is typically indicated to redirect pulmonary venous return to the left atrium and address associated anomalies [

2]. In some cases, this correction is accompanied by mitral valve interventions such as annuloplasty to treat coexistent mitral regurgitation [

3].

Mitral annuloplasty, though effective in restoring valve competence, can involve anatomical regions near the atrioventricular (AV) node and His bundle [

4]. This proximity increases the risk of conduction disturbances, both immediate and late onset [

5]. Long-term sequelae such as first- or second-degree AV block may develop insidiously, years after initial surgery. Additionally, the atrial surgical substrate, coupled with age-related fibrosis, can predispose to atrial arrhythmias including atrial fibrillation (AF) and atrial flutter [

6].

Recent advances in echocardiographic imaging, especially tissue Doppler imaging (TDI) and speckle-tracking echocardiography (STE), have enabled precise evaluation of left atrial (LA) mechanics, including intra-atrial conduction time and mechanical synchrony [

7]. These tools are increasingly used to guide management decisions in arrhythmia care, particularly in patients with structural heart disease or previous cardiac surgery [

8,

9]. LA strain, in particular, serves as a sensitive marker of atrial remodeling and functional reserve, complementing volumetric assessments [

10,

11].

Clinical Significance: This report presents a case of delayed AV conduction disturbances and atrial arrhythmias in a patient decades after surgical correction of Scimitar Syndrome and mitral annuloplasty. We discuss the role of echocardiographic findings, including strain imaging, in directing therapeutic strategies and avoiding unnecessary ablation.

2. Case Presentation

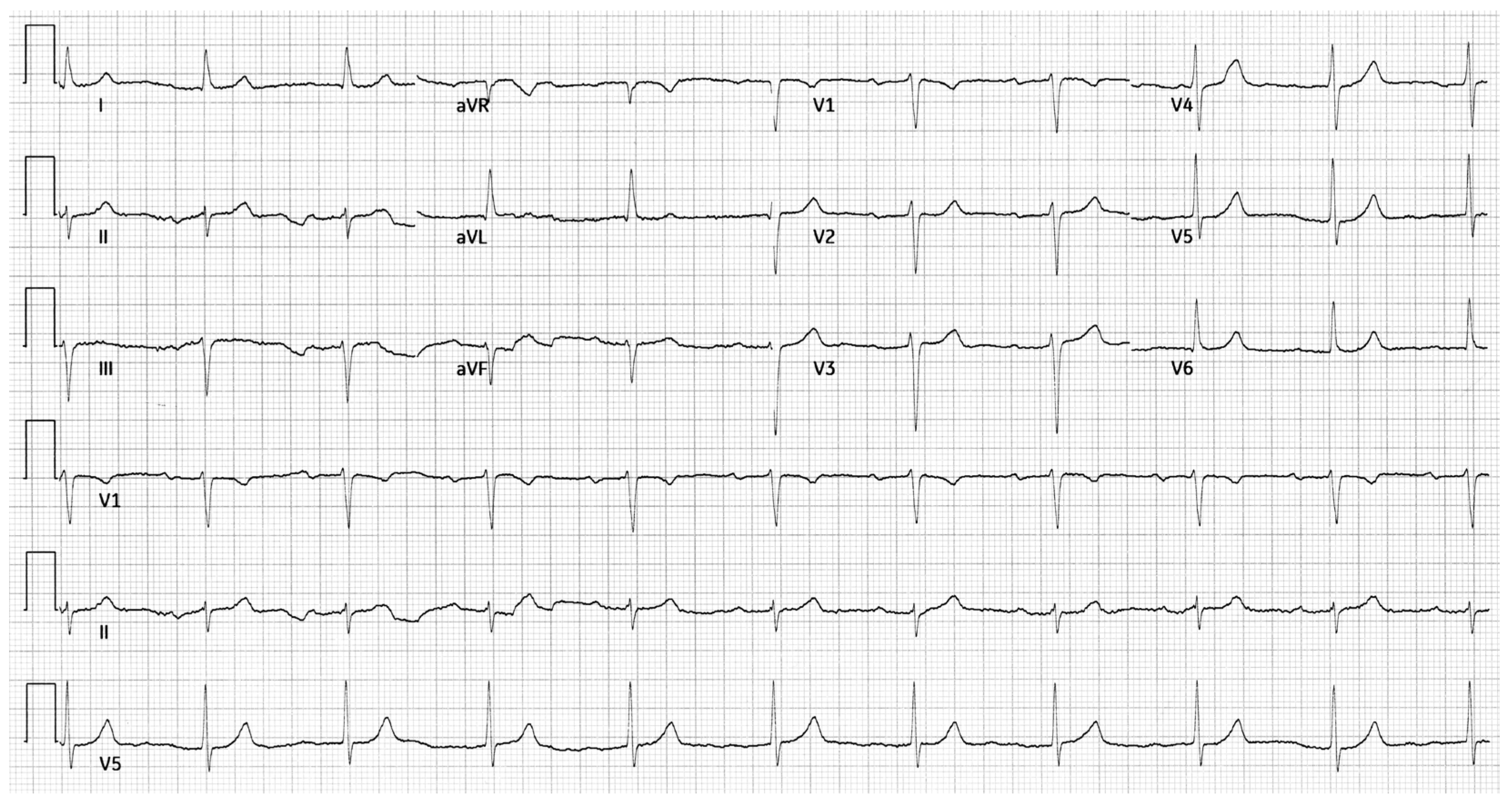

A 53-year-old male with a history of Scimitar Syndrome presented for evaluation of recurrent arrhythmias. At age 19, he had undergone surgical redirection of the anomalous right pulmonary vein into the left atrium. Concomitantly, he received mitral valve annuloplasty to address mild mitral regurgitation. The patient had an uneventful postoperative recovery and remained clinically stable for over two decades. In his mid-40s, the patient developed paroxysmal atrial fibrillation managed with direct oral anticoagulation, amiodarone and beta-blockers. He subsequently developed atrial flutter, treated successfully with electrical cardioversion. Shortly thereafter, he experienced a transient Mobitz type I AV block, which resolved following discontinuation of amiodarone. Approximately one year later, he had a syncopal episode during which a Mobitz type II AV block was documented. The conduction abnormality resolved spontaneously. The patient also referred a history of hiatal hernia and gastroesophageal reflux disease, managed conservatively. A resting 12-lead ECG showed sinus rhythm with a PR interval of 248 ms and left axis deviation (

Figure 1).

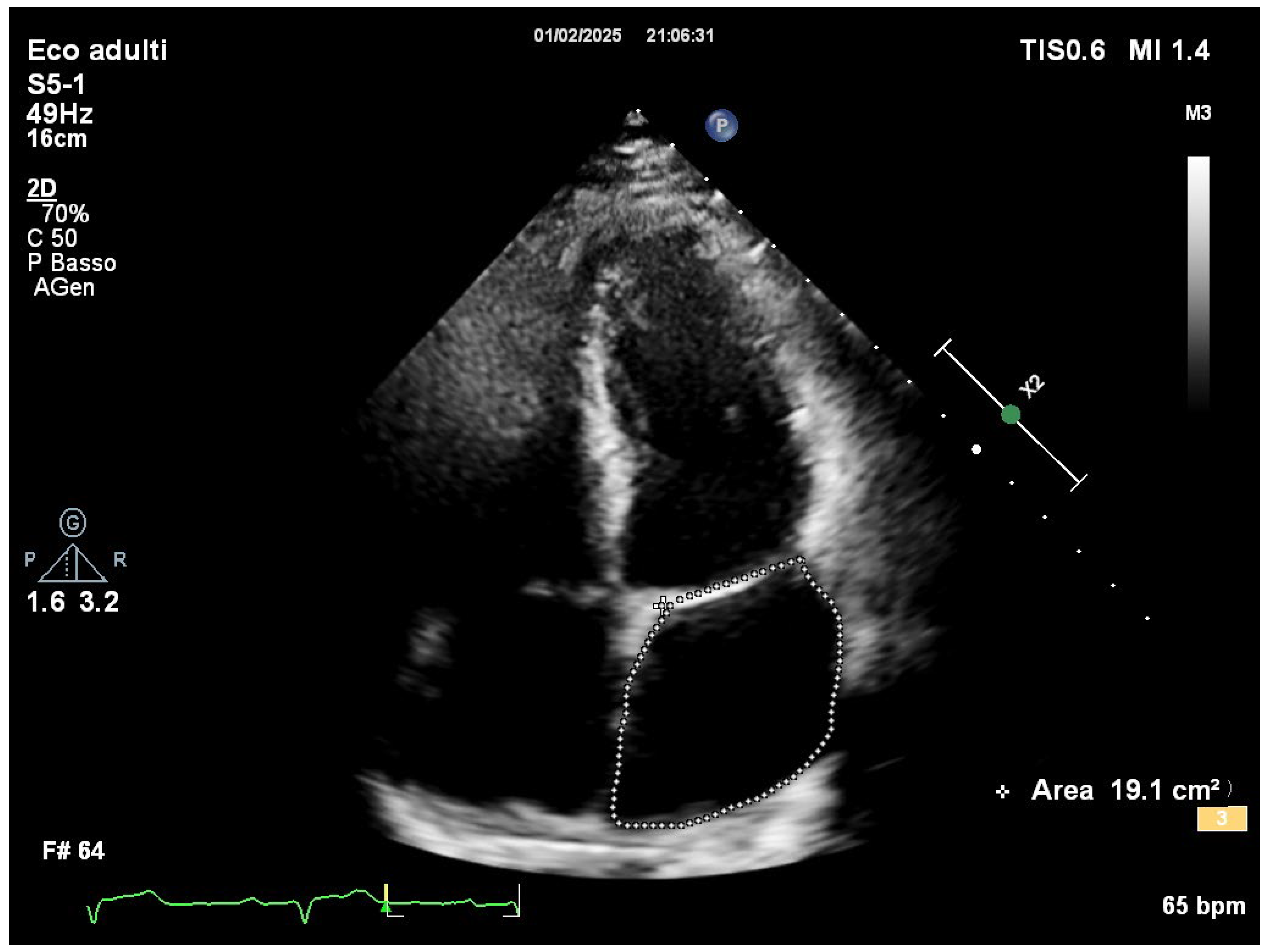

Comprehensive transthoracic echocardiographic evaluation revealed a normal left atrial volume, with no evidence of dilation and a left atrial volume of 19.1 cm

2 (

Figure 2).

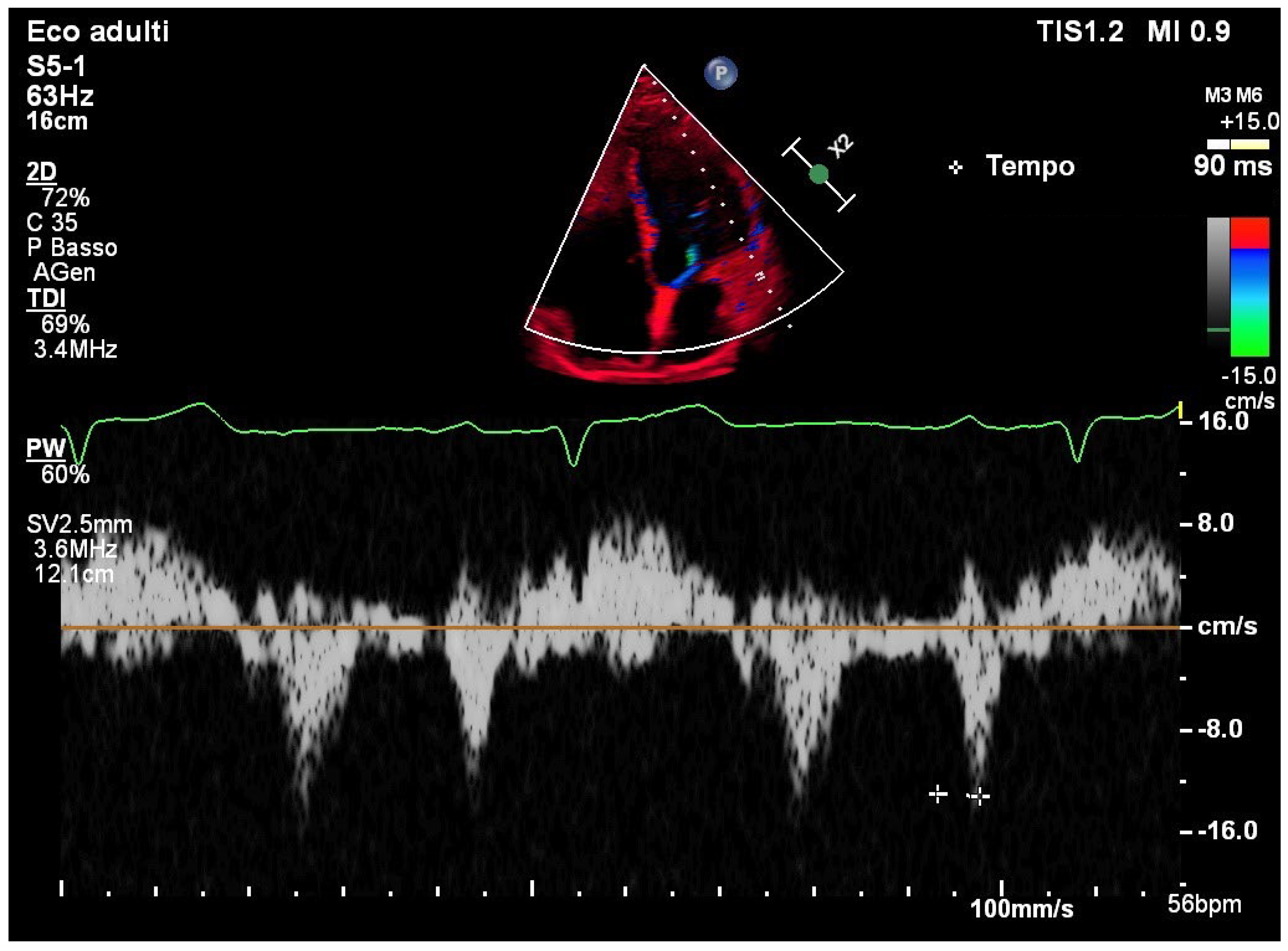

TDI of the lateral mitral annulus showed a normal PA-TDI interval of 90 msec, consistent with preserved intra-atrial conduction (

Figure 3).

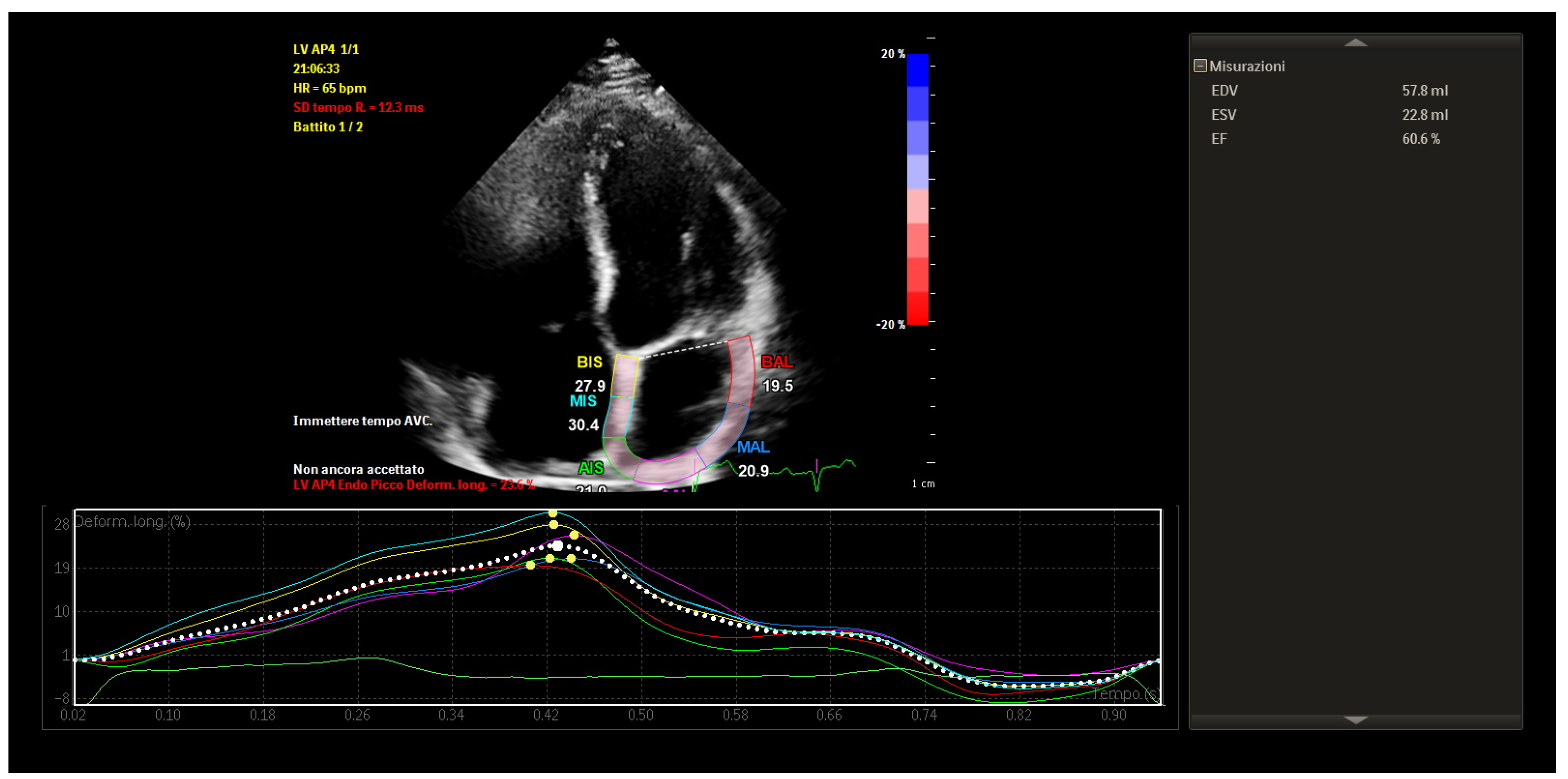

STE revealed mildly reduced left atrial longitudinal strain values, particularly in posterior and septal segments. Despite this, global atrial strain remained within functional thresholds. Importantly, the strain curves demonstrated preserved synchrony across atrial segments, with uniform timing of peak contraction and no evidence of mechanical dispersion.

These findings indicated that, although some subclinical impairment of atrial compliance was present, the atrial contractile function was globally coordinated and electromechanically integrated (

Figure 4).

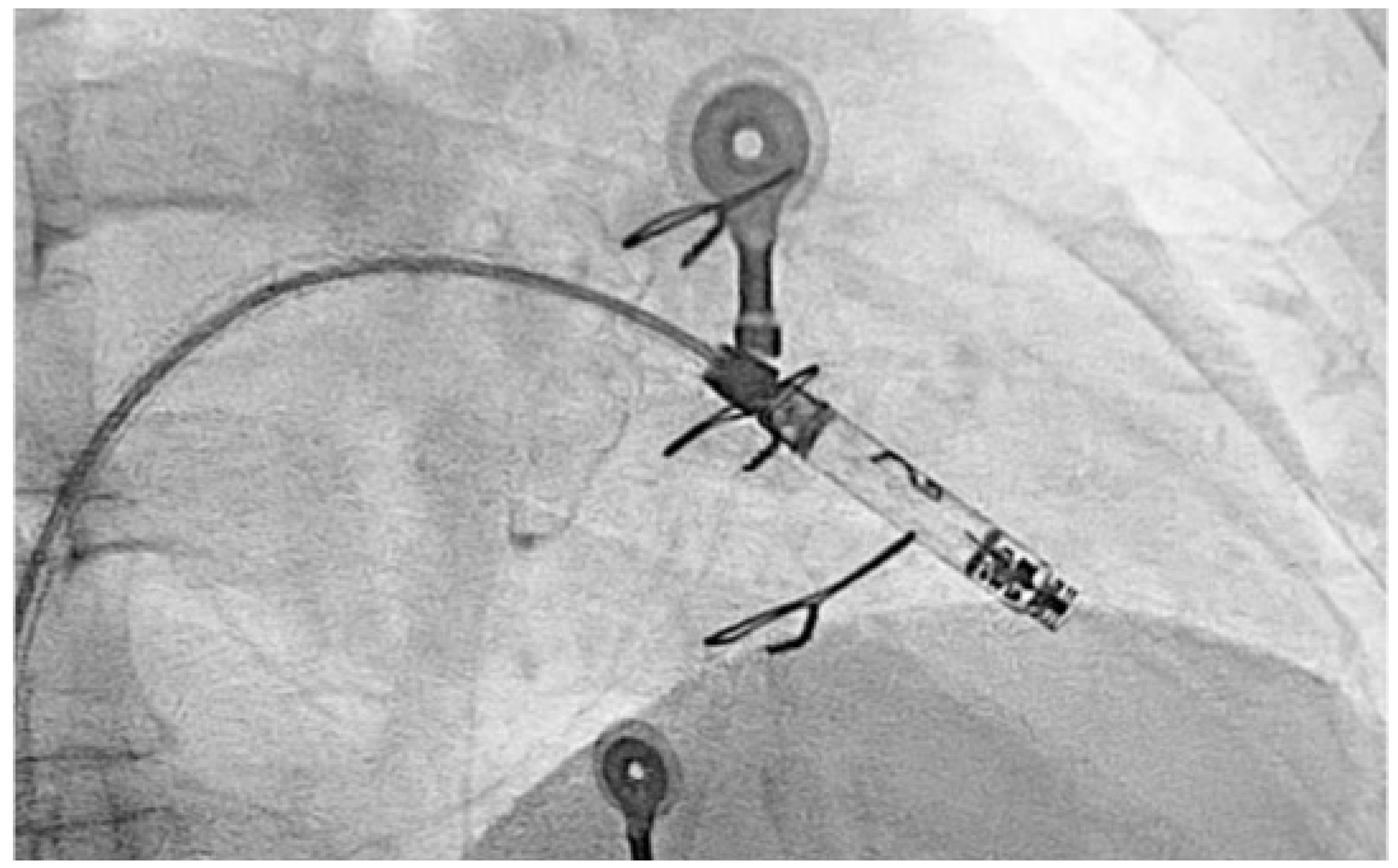

Due to recurrence of conduction disturbances and syncope, a leadless ventricular pacemaker (Aveir, Abbott) was implanted (

Figure 5), and beta-blocker therapy was continued for rate control.

3. Discussion

This case highlights the long-term arrhythmic consequences of congenital heart surgery, particularly when involving atrial structures and the mitral annulus.

The mitral annuloplasty likely contributed to the development of AV block due to the anatomical proximity of the annuloplasty ring to the AV node and the His bundle [

12]. The pathophysiological mechanisms by which mitral annuloplasty can lead to AV block are primarily related to the anatomical and functional relationship between the mitral annulus and the cardiac conduction system [

13]. The AV node and the bundle of His are located in the membranous septum, which lies in close proximity to the anteroseptal portion of the mitral annulus—particularly near the fibrous trigone and the aortomitral continuity. During mitral annuloplasty, especially when sutures or prosthetic rings are placed too medially or too deeply, and depending on anatomical variations in aortic root rotation, mechanical trauma can occur to the conduction tissues [

14]. This trauma may disrupt normal electrical conduction either immediately or over time.

In addition to direct mechanical injury, ischemic insult to the conduction system may result from compromised blood supply, particularly from branches of the atrioventricular nodal artery, which can be distorted or compressed during ring implantation. Moreover, the inflammatory response that follows surgical manipulation can lead to edema and local cytokine release, which may transiently impair conduction. In the longer term, healing processes can result in fibrosis and scarring around the conduction tissue, leading to persistent AV block [

15]. Furthermore, annular remodeling caused by the rigid or semi-rigid prosthetic ring can alter the geometry and tension of adjacent tissues, possibly exacerbating injury or impeding electrical propagation. These mechanisms collectively explain how a structurally corrective procedure can paradoxically lead to conduction system dysfunction. Importantly, in our case, comprehensive atrial assessment revealed preserved atrial function. In this case, the normal PA-TDI interval and preserved mechanical synchrony on strain imaging suggested intact intra-atrial conduction, supporting the view that the AV block originated at the nodal level rather than reflecting widespread atrial conduction disease. This distinction was fundamental in guiding therapeutic strategy.

Regarding the management of atrial fibrillation, while pulmonary vein isolation or posterior wall ablation was initially considered, echocardiographic findings argued against this approach. LA strain imaging provided crucial information on the functional state of the atrial myocardium. Its role in evaluating atrial mechanics and remodeling is increasingly recognized and has been correlated with both arrhythmic burden and procedural outcomes [

16]. In this case, preserved strain and synchrony suggested a relatively healthy atrial substrate, reducing the indication for substrate modification via ablation [

17]. Additionally, the patient's history of hiatal hernia and gastroesophageal reflux suggested a possible vagally mediated gastric trigger for the atrial arrhythmia, further reinforcing the decision to avoid an invasive approach.

The decision to implant a leadless ventricular pacemaker reflected the need for bradyarrhythmia protection without exposing the patient to the risks of transvenous leads. Recent studies have supported the safety and efficacy of leadless systems in patients with isolated AV block and preserved atrial conduction [

18]. Specifically, the choice of the Aveir leadless pacemaker was also guided by its modular design, which allows for future expansion. Should it become necessary, an atrial lead can be added to restore physiological atrioventricular conduction through device-based AV synchrony [

19]. This option provides both clinical flexibility and the potential for improved hemodynamic performance over time.

This case also illustrates the value of a multimodal, non-invasive imaging approach in tailoring therapy in complex post-surgical patients. As highlighted in recent literature, functional markers such as strain imaging can complement traditional electrophysiological parameters in refining risk stratification and guiding treatment [

20].

4. Conclusions

In patients with surgically corrected congenital heart disease, late-onset conduction disturbances may reflect the long-term impact of anatomical interventions near critical conduction tissues. In this case, AV block was likely related to mitral annuloplasty. Echocardiographic parameters, including preserved left atrial volume, normal intra-atrial conduction time, and synchronized atrial strain, were instrumental in guiding a non-ablative management strategy focused on pacing and medical therapy. Left atrial strain imaging proved essential in assessing atrial integrity and informing clinical decisions.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, F.C. and M.V.; methodology, C.M.; software, S.C.; validation, G.C.; formal analysis, M.V.; investigation, F.C.; resources, G.C. and P.T.; data curation, S.C.; writing—original draft preparation, F.C.; writing—review and editing, F.C.; visualization, M.V.; supervision, C.M.; project administration, F.C. and M.V. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Informed Consent Statement

Written informed consent has been obtained from the patient to publish this paper.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| AV |

Atrioventricular |

| AF |

Atrial Fibrillation |

| TDI |

Tissue Doppler Imaging |

| STE |

Speckle-Tracking Echocardiography |

| LA |

Left Atrial |

References

- Diaz-Frias, J.; Widrich, J. Scimitar Syndrome. In StatPearls; StatPearls Publishing: Treasure Island (FL), 26 June 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Gudjonsson, U.; Brown, J.W. Scimitar syndrome. Semin Thorac Cardiovasc Surg Pediatr Card Surg Annu. 2006, 56–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bae, Y.; Jang, W.S.; Song, K. Surgical correction of total anomalous pulmonary venous return in an adult patient. J Cardiothorac Surg. 2022, 17, 237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berdajs, D.; Schurr, U.P.; Wagner, A.; Seifert, B.; Turina, M.I.; Genoni, M. Incidence and pathophysiology of atrioventricular block following mitral valve replacement and ring annuloplasty. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2008, 34, 55–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brodell, G.K.; Cosgrove, D.; Schiavone, W.; Underwood, D.A.; Loop, F.D. Cardiac rhythm and conduction disturbances in patients undergoing mitral valve surgery. Cleve Clin J Med. 1991, 58, 397–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clarke, N.S.; Murthy, R.; Guleserian, K.J. Scimitar syndrome with atrial fibrillation: Repair in an adult. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2016, 152, e105–e107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cacciapuoti, F.; Caso, I.; Crispo, S.; Verde, N.; Capone, V.; Gottilla, R.; Materazzi, C.; Volpicelli, M.; Ziviello, F.; Mauro, C.; et al. Linking Epicardial Adipose Tissue to Atrial Remodeling: Clinical Implications of Strain Imaging. Hearts. 2025, 6, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, Y.; Huang, L.; Jiang, C.; Du, F.; Zhang, J.; Chang, P. Usefulness of two-dimensional speckle tracking echocardiography in assessment of left atrial fibrosis degree and its application in atrial fibrillation. Int J Cardiovasc Imaging 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Granchietti, A.G.; Ciardetti, N.; Mazzoni, C.; Garofalo, M.; Mazzotta, R.; Micheli, S.; Chiostri, M.; Orlandi, M.; Biagiotti, L.; Del Pace, S.; et al. Left atrial strain and risk of atrial fibrillation after coronary artery bypass-grafting. Int J Cardiol. 2025, 422, 132981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, T.; Hu, H.; Zhu, R.; Hu, W.; Li, X.; Shen, D.; Zhang, A.; Zhou, C. Ultrasound assessment of the association between left atrial remodeling and fibrosis in patients with valvular atrial fibrillation: a clinical investigation. BMC Cardiovasc Disord. 2025, 25, 149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Benjamin, M.M.; Rabbat, M.G. Left Atrial Markers in Diagnosing and Prognosticating Non-Ischemic Cardiomyopathies: Ready for Prime Time? Echocardiography 2025, 42, e70088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kruse, K.; Matsubara, M.; Schaeffer, T.; Palm, J.; Klawonn, F.; Osawa, T.; Niedermaier, C.; Heinisch, P.P.; Piber, N.; Balling, G.; et al. Postoperative atrioventricular block after surgery for congenital heart disease: incidence, recovery and risks. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2025, 67, ezaf059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Handa, K.; Kawamura, M.; Yoshioka, D.; Saito, S.; Kawamura, T.; Kawamura, A.; Misumi, Y.; Taira, M.; Shimamura, K.; Komukai, S.; et al. Impact of the Aortomitral Positional Anatomy on Atrioventricular Conduction Disorder Following Mitral Valve Surgery. J Am Heart Assoc. 2024, 13, e035826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Handa, K.; Kawamura, M.; Yoshioka, D.; Saito, S.; Kawamura, T.; Kawamura, A.; Misumi, Y.; Komukai, S.; Kitamura, T.; Miyagawa, S. Impact of aortic root rotation angle on new-onset first-degree atrioventricular block following mitral valve surgery. Interdiscip Cardiovasc Thorac Surg. 2025, 40, ivaf046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Cheung, C.C.; Mori, S.; Gerstenfeld, E.P. Iatrogenic Atrioventricular Block. Cardiol Clin. 2023, 41, 419–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, A.L.; Liu, Y.B.; Lin, L.Y.; Huang, H.C.; Ho, L.T.; Huang, K.C.; Lai, L.P.; Chen, W.J.; Ho, Y.L.; Lin, L.C.; et al. Left atrial reservoir strain as a surrogate marker for atrial fibrillation burden in patients with non-valvular atrial fibrillation. J Formos Med Assoc. 2025, S0929-6646(25)00066-X. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, R.; Li, H.; Wang, Y.; Yu, T.; Li, J.; Wu, Y.; Yu, Z.; Liang, C.; Yu, D.; Xue, L. Left atrial strain predicts paroxysmal atrial fibrillation recurrence after catheter ablation: a 1-year study using three-dimensional speckle-tracking echocardiography. BMC Cardiovasc Disord. 2025, 25, 78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Yan, L.; Ling, L.; Song, Y.; Jiang, T. Efficacy and safety of leadless ventricular pacemaker: a single-center retrospective observational study. Cardiovasc Diagn Ther. 2024, 14, 878–889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Doshi, R.N.; Ip, J.E.; Defaye, P.; Reddy, V.Y.; Exner, D.V.; Canby, R.; Shoda, M.; Bongiorni, M.G.; Hindricks, G.; Neuzil, P.; et al. Dual-chamber leadless pacemaker implant procedure outcomes: Insights from the AVEIR DR i2i study. Heart Rhythm. 2015, S1547-5271(25)02176-9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pozios, I.; Vouliotis, A.I.; Dilaveris, P.; Tsioufis, C. Electro-Mechanical Alterations in Atrial Fibrillation: Structural, Electrical, and Functional Correlates. J Cardiovasc Dev Dis. 2023, 10, 149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).