1. Introduction

Lung cancer remains the leading cause of cancer-related mortality globally, accounting for over 1.8 million deaths annually [

1]. Beyond its oncologic burden, lung cancer frequently coexists with systemic complications, among which coagulation disorders are particularly consequential. Venous thromboembolism (VTE), including deep vein thrombosis (DVT) and pulmonary embolism (PE), occurs in up to 15% of lung cancer patients, with higher incidence in those receiving chemotherapy or harboring metastatic disease [

2,

3].

The association between cancer and thrombosis, first described by Armand Trousseau in the 19th century, is now recognized as a distinct clinical entity known as cancer-associated thrombosis (CAT) [

4]. Among all malignancies, lung cancer exhibits one of the highest risks for thrombotic events, due to the combined effects of tumor-derived procoagulants, systemic inflammation, immune dysregulation, and treatment-related complications [

5,

6].

These coagulation abnormalities have direct clinical implications. Thrombotic events may occur early in the disease course and are associated with worse overall survival [

7]. Additionally, some lung cancer patients develop acquired coagulation inhibitors, such as lupus anticoagulant or antibodies against clotting factors, which predispose them to both thrombosis and bleeding. This dual risk presents a significant therapeutic challenge, particularly when balancing anticoagulation with the potential for hemorrhage [

8,

9].

Recognition of CAT is critical for oncologists, as it can influence therapeutic decisions, treatment tolerance, and hospitalization rates. Risk stratification tools and biomarkers can aid in early detection, while evidence-based anticoagulation strategies are essential for optimal patient outcomes [

10,

11].

This review aims to provide an updated, clinically relevant overview of coagulation abnormalities in lung cancer, emphasizing pathophysiological mechanisms, diagnostic approaches, and practical considerations in therapy.

2. Mechanisms of Hypercoagulability in Lung Cancer

The hypercoagulable state in lung cancer arises from a multifactorial process involving tumor biology, systemic inflammation, endothelial dysfunction, autoimmune responses, and iatrogenic factors. These mechanisms act synergistically to promote thrombin generation, inhibit fibrinolysis, and enhance platelet activation, thereby contributing to the elevated incidence of venous thromboembolism (VTE) in this population [

2,

5,

12].

2.1. Tumor-Derived Procoagulants

Lung cancer cells, particularly those of adenocarcinoma histology, often overexpress tissue factor (TF), a primary initiator of the extrinsic coagulation cascade. TF forms a complex with activated factor VII (FVIIa), leading to activation of factor X and subsequent thrombin generation [

13]. In addition, tumor cells release TF-positive microparticles (MPs) into circulation, which propagate coagulation by activating platelets and endothelial cells [

14].

TF expression is not only associated with thrombotic risk but also correlates with tumor aggressiveness and angiogenesis, suggesting a bidirectional relationship between hemostasis and cancer progression [

6,

15].

2.2. Inflammatory Cytokine Activation

The tumor microenvironment in lung cancer is enriched with inflammatory mediators such as interleukin-6 (IL-6), tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α), and interleukin-1 beta (IL-1β), all of which upregulate TF expression and downregulate natural anticoagulants like antithrombin and protein C [

8,

16]. IL-6 also promotes thrombopoiesis through hepatic stimulation of thrombopoietin, contributing to increased platelet turnover [

17].

Furthermore, these cytokines elevate levels of plasminogen activator inhibitor-1 (PAI-1), thereby inhibiting fibrinolysis and stabilizing thrombi [

10].

2.3. Endothelial Dysfunction and Platelet Activation

Endothelial cells play a central role in maintaining vascular integrity. In lung cancer, their function is compromised by oxidative stress, inflammatory cytokines, and direct tumor invasion [

11]. Damaged endothelium exhibits reduced production of anticoagulant proteins such as thrombomodulin and tissue plasminogen activator (tPA), while expressing higher levels of adhesion molecules (e.g., E-selectin, ICAM-1) that facilitate leukocyte and platelet adhesion [

12].

Tumor–platelet interactions further exacerbate the prothrombotic state. Activated platelets promote clot formation and aid in tumor immune evasion by shielding circulating tumor cells (CTCs) from immune surveillance [

13,

18].

2.4. Autoimmunity and Acquired Inhibitors

Autoimmune features, notably the presence of antiphospholipid antibodies (aPL), including lupus anticoagulant (LA), have been reported in patients with solid tumors, including lung cancer [

9]. These antibodies interfere with phospholipid-dependent coagulation assays and paradoxically increase the risk of thrombosis despite prolongation of activated partial thromboplastin time (aPTT) [

14].

Rarely, acquired inhibitors of clotting factors—especially Factor VIII or IX—may develop, leading to life-threatening bleeding episodes. These patients often present with isolated, unexplained aPTT prolongation and require specialized diagnostic assays such as mixing studies and Bethesda assays [

15,

19].

2.5. Treatment-Related Risks

Chemotherapeutic agents, targeted therapies (e.g., anti-VEGF agents), and immune checkpoint inhibitors have all been associated with increased thrombotic risk [

20,

21]. Surgery, particularly lung resections, further augments this risk, especially in immobilized or elderly patients.

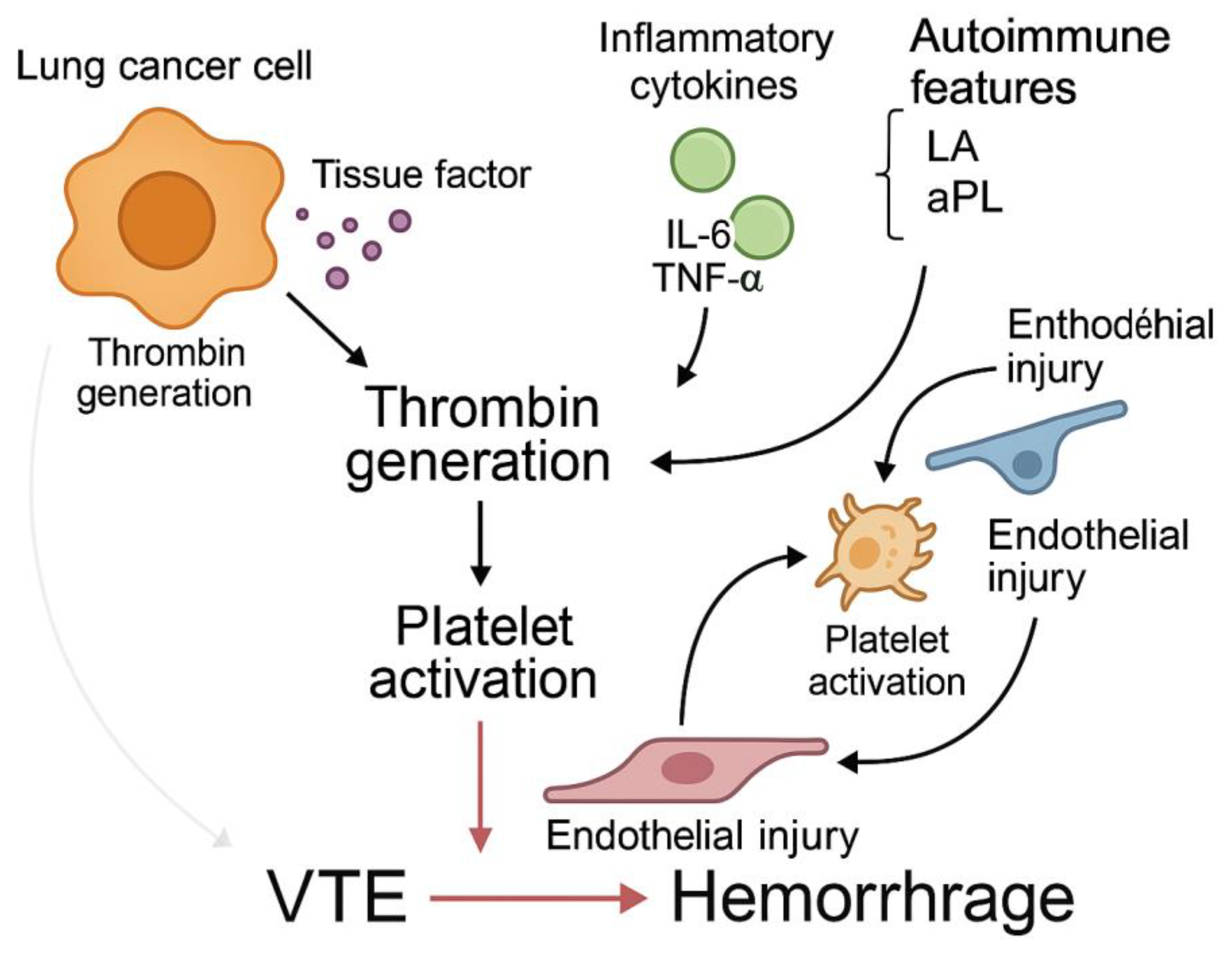

While these treatments are often essential for disease control, they must be carefully balanced with the potential for thrombohemorrhagic complications (

Figure 1,

Table 1).

This figure illustrates the multifactorial pathogenesis of hypercoagulability in lung cancer. Lung cancer cells release tissue factor (TF) and procoagulant microparticles, leading to thrombin generation and platelet activation. Inflammatory cytokines such as IL-6 and TNF-α promote coagulation and impair fibrinolysis. Endothelial dysfunction contributes to leukocyte adhesion and vascular injury, while autoimmune phenomena (e.g., lupus anticoagulant, antiphospholipid antibodies) predispose to both thrombosis and bleeding. These interacting pathways converge into a thromboinflammatory state, culminating in venous thromboembolism (VTE) and hemorrhagic complications.

3. Diagnostic Strategies in Cancer-Associated Coagulopathy

Timely diagnosis of coagulation abnormalities in lung cancer patients is critical to reducing morbidity and optimizing therapeutic decisions. A comprehensive approach, combining laboratory studies, biomarker evaluation, and imaging, is essential for detecting both thrombotic and bleeding risks.

3.1. Laboratory Assessment

Initial laboratory testing should include prothrombin time (PT), activated partial thromboplastin time (aPTT), fibrinogen levels, D-dimer, complete blood count (CBC), and peripheral blood smear. In patients with prolonged aPTT in the setting of thrombosis, lupus anticoagulant (LA) or acquired coagulation inhibitors should be considered [

8,

14].

Mixing studies are essential to differentiate between factor deficiencies and inhibitors. If the aPTT normalizes upon mixing with normal plasma, a deficiency is likely; persistent prolongation suggests the presence of an inhibitor [

15].

In cases of suspected acquired hemophilia (e.g., anti-Factor VIII or IX), the Bethesda assay quantifies inhibitor activity and guides treatment [

19]. These assays are particularly important in lung cancer patients with bleeding of unknown origin, where prompt identification of an inhibitor can be lifesaving.

3.2. Biomarker Evaluation

D-dimer is a nonspecific but sensitive marker for thrombosis and is often elevated in cancer patients. Elevated fibrinogen and soluble P-selectin levels have also been associated with increased thrombotic risk and worse prognosis in lung cancer [

16,

22].

The Khorana score, which incorporates clinical and laboratory variables (e.g., cancer type, platelet count, hemoglobin, leukocyte count, BMI), remains a widely used tool for VTE risk stratification in oncology [

10]. Although its predictive value is higher in gastrointestinal and pancreatic cancers, it still provides a useful baseline risk estimate in lung cancer [

23].

Emerging biomarkers, including microparticle-associated tissue factor activity and NETs (neutrophil extracellular traps), may offer enhanced predictive accuracy in the future but are not yet standard in routine practice [

24].

3.3. Imaging Modalities

Imaging remains the gold standard for confirming thrombotic events. Compression ultrasonography is preferred for diagnosing deep vein thrombosis (DVT), while computed tomography pulmonary angiography (CTPA) is the most accurate method for detecting pulmonary embolism (PE) [

25].

In patients presenting with unexplained thrombocytopenia or bleeding, contrast-enhanced CT or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) may help identify tumor infiltration, hemorrhagic transformation, or metastasis-related complications.

Given the dynamic course of cancer-associated coagulopathy, repeat imaging may be warranted in patients with new or worsening symptoms despite anticoagulation.

4. Management of Coagulation Abnormalities

The management of coagulation disorders in lung cancer involves balancing the prevention and treatment of thrombotic events against the risk of bleeding, particularly in patients with underlying coagulopathies or treatment-related complications. Clinical decision-making must be personalized, taking into account cancer stage, performance status, renal and hepatic function, platelet count, and concomitant therapies.

4.1. Anticoagulation in Lung Cancer

Low-molecular-weight heparins (LMWHs) remain the first-line treatment for cancer-associated thrombosis (CAT) due to their efficacy, predictable pharmacokinetics, and minimal drug interactions [

19,

26]. LMWH is particularly suitable for patients’ undergoing chemotherapy or those with fluctuating renal or hepatic function.

Direct oral anticoagulants (DOACs), such as apixaban and edoxaban, have demonstrated non-inferiority to LMWH in recent trials [

20,

27]. However, they must be used with caution in patients with gastrointestinal or genitourinary tumors, mucosal lesions, or high bleeding risk. In lung cancer, DOACs can be considered in selected patients with adequate platelet counts (>50,000/µL) and preserved organ function.

Warfarin is generally discouraged due to its narrow therapeutic window, variable metabolism, dietary interactions, and frequent INR monitoring requirements. However, it may still have a role in resource-limited settings or for patients with contraindications to other agents.

Prophylactic anticoagulation may be considered in hospitalized or high-risk ambulatory patients with lung cancer, particularly those with elevated Khorana scores or elevated D-dimer levels [

23].

4.2. Management of Acquired Coagulation Inhibitors

Acquired inhibitors of coagulation, such as anti-Factor VIII or IX antibodies, can cause severe and spontaneous bleeding. In lung cancer, these events are rare but potentially fatal. Management includes both control of bleeding and eradication of the inhibitor [

15,

28].

Acute bleeding is typically treated with bypassing agents such as activated prothrombin complex concentrates (aPCC) or recombinant activated factor VII (rFVIIa). Immunosuppressive therapy—comprising corticosteroids, rituximab, cyclophosphamide, or combinations thereof—is the mainstay for inhibitor eradication [

29].

Coordination between oncology and hematology teams is essential, as immunosuppressive regimens may impact cancer control and infection risk.

4.3. Multidisciplinary Monitoring and Follow-Up

Given the evolving nature of cancer-associated coagulopathy, continuous reassessment is necessary. Regular monitoring of coagulation parameters, platelet counts, renal and liver function, and signs of bleeding or thrombosis should be integrated into the patient’s oncology follow-up [

6,

30].

A multidisciplinary approach, involving oncologists, hematologists, internists, pharmacists, and critical care teams (when needed), is strongly recommended for complex cases—especially those with concurrent thrombosis and hemorrhage.

Early identification of high-risk patients and proactive management strategies can improve outcomes and reduce unplanned hospitalizations, treatment interruptions, and mortality.

5. Conclusion and Future Directions

Coagulation abnormalities in lung cancer are the result of a complex interplay between malignancy-associated procoagulant activity, systemic inflammation, immune dysregulation, endothelial injury, and treatment-related effects. These disruptions manifest primarily as venous thromboembolism (VTE), but may also include hemorrhagic complications, particularly in patients with acquired coagulation inhibitors or thrombocytopenia.

Beyond their immediate clinical consequences, coagulation disorders may reflect tumor biology and influence prognosis, making their early recognition and management essential components of oncologic care. Advances in diagnostic tools, including targeted biomarker evaluation and functional coagulation assays, have enhanced our ability to stratify risk and personalize therapy.

Looking ahead, research should focus on integrating molecular profiling, inflammatory markers, and coagulation parameters into comprehensive risk models. Trials assessing anticoagulation in patients with autoimmune markers or coagulation inhibitors are needed, as are strategies targeting tissue factor expression or platelet–tumor cell interactions.

Ultimately, multidisciplinary collaboration will remain central to navigating this complex terrain. A patient-centered approach, supported by evolving scientific insights and clinical vigilance, can help mitigate thrombohemorrhagic risks and improve outcomes for individuals with lung cancer.

5.1. Clinical Integration: Practical Recommendations

Routine screening for thrombotic risk factors, including D-dimer and Khorana score, should be considered at diagnosis and during treatment planning.

Mixing studies and lupus anticoagulant testing should be performed in patients with prolonged aPTT, particularly if thrombosis or bleeding is present.

Anticoagulant selection must be individualized. LMWH remains the standard, but DOACs are suitable for select patients with low bleeding risk.

Inhibitor-related bleeding requires rapid hematology consultation and access to bypassing agents and immunosuppression.

Multidisciplinary coordination (oncology, hematology, pharmacy) is vital, especially in complex or critically ill cases.

Patient education on symptoms of thrombosis and bleeding should be an integral part of cancer care.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.M.; methodology, A.M.; software, K.B.; validation, A.M., A.P. and K.B.; formal analysis, S.O.; investigation, A.M.; resources, S.O.; data curation, A.P.; writing—original draft preparation, A.M.; writing—review and editing, A.M.; visualization, A.P.; supervision, F.G.; project administration, A.M.; funding acquisition, A.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Ethical review and approval were waived for this study because it is a narrative review based solely on previously published data and does not involve new human or animal research.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study. Data sharing is not applicable to this article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| VTE |

venous thromboembolism |

| DVT |

deep vein thrombosis |

| PE |

pulmonary embolism |

| CAT |

cancer-associated thrombosis |

References

- Siegel RL, Miller KD, Fuchs HE, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2023. CA Cancer J Clin. 2023;73(1):17–48. [CrossRef]

- Khorana AA, Kuderer NM, Culakova E, et al. Development and validation of a predictive model for chemotherapy-associated thrombosis. Blood. 2008;111(10):4902–4907. [CrossRef]

- Tagalakis V, Kavan P, Zukor D, et al. Clinical predictors of venous thromboembolism in patients with cancer. Curr Oncol. 2022;29(1):13–24. PMID: 35069530.

- Varki A. Trousseau's syndrome: multiple definitions and multiple mechanisms. Blood. 2007;110(6):1723–1729. [CrossRef]

- Blom JW, Doggen CJ, Osanto S, Rosendaal FR. Malignancies, prothrombotic mutations, and the risk of venous thrombosis. JAMA. 2005;293(6):715–722. PMID: 15701913.

- Thaler J, Ay C, Pabinger I. Venous thromboembolism and cancer: a risk factor for poor prognosis in cancer patients. Semin Thromb Hemost. 2014;40(7):791–803. [CrossRef]

- Grilz E, Königsbrügge O, Posch F, et al. Cancer-associated thrombosis is associated with mortality in a prospective cohort study. Thromb Res. 2018;164(Suppl 1): S112–S117. PMID: 30100232.

- Caine GJ, Stonelake PS, Lip GY, Kehoe ST. The hypercoagulable state of malignancy: pathogenesis and current debate. Neoplasia. 2002;4(6):465–473. [CrossRef]

- Pengo V, Banzato A, Bison E, et al. What have we learned about antiphospholipid syndrome from patients presenting with isolated lupus anticoagulant? Autoimmun Rev. 2018;17(8):810–812. [CrossRef]

- Ay C, Dunkler D, Marosi C, et al. Prediction of venous thromboembolism in cancer patients. Blood. 2010;116(24):5377–5382. [CrossRef]

- Levi M, van der Poll T. Endothelial injury in sepsis. Intensive Care Med. 2013;39(10):1839–1842. [CrossRef]

- Kumar S, Kim CW, Simmons RD, Jo H. Role of flow-sensitive microRNAs in endothelial dysfunction and atherosclerosis: mechanosensitive athero-miRs. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2014;34(10):2206–2216. [CrossRef]

- Hisada Y, Mackman N. Tissue factor and cancer: regulation, tumor growth, and metastasis. Semin Thromb Hemost. 2019;45(4):385–395. PMID: 30810753.

- Tesselaar ME, Romijn FP, Van Der Linden IK, et al. Microparticle-associated tissue factor activity: a link between cancer and thrombosis? J Thromb Haemost. 2007;5(3):520–527. PMID: 17155953.

- Franchini M, Lippi G. Acquired factor VIII inhibitors. Blood. 2008;112(2):250–255. [CrossRef]

- Liu F, Song D, Xie H, et al. Interleukin-6, tumor necrosis factor-alpha, and interleukin-1 beta as diagnostic biomarkers for sepsis: a meta-analysis. PLoS One. 2016;11(7): e0159065. [CrossRef]

- Kwaan HC. Role of plasma plasminogen activator inhibitor-1 in vascular disease. Am J Med. 1992;92(6A):62S–68S. [CrossRef]

- Labelle M, Begum S, Hynes RO. Direct signaling between platelets and cancer cells induces an epithelial-mesenchymal-like transition and promotes metastasis. Cancer Cell. 2011;20(5):576–590. [CrossRef]

- Verbruggen B, Novakova I, Wessels H, et al. The Nijmegen modification of the Bethesda assay for factor VIII inhibitors: improved specificity and reliability. Thromb Haemost. 1995;73(2):247–251.

- Moore RA, Adel N, Riedel E, et al. High incidence of thromboembolic events in patients treated with cisplatin-based chemotherapy: a large retrospective analysis. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29(25):3466–3473. PMID: 21788568.

- Agnelli G, Becattini C, Meyer G, et al. Apixaban for the treatment of venous thromboembolism associated with cancer. N Engl J Med. 2020;382(17):1599–1607. PMID: 32320558.

- van Es N, Di Nisio M, Cesarman G, et al. Biomarkers for cancer-associated venous thromboembolism. J Thromb Haemost. 2022;20(2):375–385. PMID: 34770794.

- Mulder FI, Bosch FT, Young AM, et al. Validation of the Khorana score for prediction of VTE in cancer patients: a pooled analysis. Thromb Haemost. 2021;121(3):328–335. PMID: 32920774.

- Carrier M, Righini M, Wells PS, et al. Subsegmental pulmonary embolism diagnosed by CT: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Chest. 2010;138(6):1093–1099. PMID: 20424131.

- Lee AY, Peterson EA. Treatment of cancer-associated thrombosis. Blood. 2013;122(14):2310–2317. PMID: 23908473.

- Tiede A, Scharf RE, Werwitzke S, et al. Diagnosis and treatment of acquired hemophilia A: guidelines from the German, Austrian, and Swiss Thrombosis and Hemostasis Society. Blood. 2020;135(7):551–564. PMID: 31871163.

- Collins PW, Hirsch S, Baglin TP, et al. Acquired hemophilia A in the UK: a 2-year national surveillance study. Blood. 2007;109(5):1870–1877. PMID: 17047148.

- Yaoita K, Takasaki T, Ito S, et al. Large Cell Neuroendocrine Carcinoma with Acquired Hemophilia a Diagnosed by Endobronchial Biopsy: A Case Report. Cureus. 2024 Oct 1;16(10): e70623. PMID: 39483578; PMCID: PMC11526768. [CrossRef]

- Lahiri A, Maji A, Potdar PD, et al. Lung cancer immunotherapy: progress, pitfalls, and promises. Mol Cancer. 2023 Feb 21;22(1):40. PMID: 36810079; PMCID: PMC9942077. [CrossRef]

- Lyman GH. Thromboprophylaxis with low-molecular-weight heparin in medical patients with cancer. Cancer. 2009 Dec 15;115(24):5637-50. PMID: 19827150; PMCID: PMC3714853. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).