1. Introduction

We are observing an industrial-scale increase in the use of the Internet of Things (IoT) in both the civilian and military spheres, a significant number of which are multi-domain. Multi-domain IoT environments such as intelligent transportation, smart power grids, resilient smart cities, intelligent healthcare, or hybrid military operations are increasingly based on the concept of federation. The aim of creating a federation is to enable different entities to use shared resources and exchange information securely and efficiently without relying on a central authority, thus facilitating cooperation and increasing the resilience of the entire system. IoT federated environments are distributed, with their components and IoT devices located in different places and belonging to various entities. One example is the creation of a federation formed of NATO countries and non-NATO mission actors (Federated Mission Networking, FMN) [

1], where each actor retains control over its capabilities and operations while accepting and meeting the requirements outlined in pre-negotiated and agreed-upon arrangements, such as the security policy. Another example is the interaction of civilian services and the military, which form a federation when providing humanitarian assistance in eliminating natural disasters (Humanitarian Assistance and Disaster Relief, HADR).

There are many situations in which federation partners need to exchange information, for example, about the location of each other’s troops, detected threats (image object detection), etc. IoT in a federation environment enhances the ability to get an accurate real-time [

2] picture of the situation during an operation, e.g., by deploying mobile IoT devices such as unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs). Hence, IoT devices operated by different federation partners must securely communicate with each other. To ensure the timely transmission of situational awareness data, the UAV may need to use a partner’s resources within the communication range. In this case and many others, it is necessary to establish a trust relationship through mutual authentication of devices belonging to different federation partners, such as between a specific UAV and the partner’s data distribution system. In the case of information exchange in federated environments, where the military participates jointly with civilian services in HADR operations in an urbanized area, it is most often assumed that mobile radio networks will be utilized as the main communication medium.

Federated IoT environments present unique security challenges due to their distributed nature and the need for secure communication between components from different administrative domains. To an even greater extent, fulfilling secure data stream distribution requirements in federated IoT environments is a complex challenge due to the heterogeneity of devices, protocols, and security requirements across domains. One example of a use case is the secure distribution of data streams in smart cities. In a smart city scenario, data streams from traffic sensors, surveillance cameras (CCTV), and environmental sensors must be securely distributed across multiple domains (e.g., transportation, public safety, and utilities).

Some known solutions and best practices for ensuring secure data stream distribution in such environments include end-to-end encryption (preventing unauthorized access during transmission), authentication (for device and data), and blockchain mechanism (to ensure data integrity and accountability). These solutions also involve processing data locally at edge gateways to reduce latency and improve security.

Another requirement for the effective distribution of data streams in federated environments is the ability to process them (filtering, pattern searching) in real-time to detect critical events (e.g., traffic congestion) or various types of threats (e.g., fire, hostile objects). It is essential to ensure flexibility and dynamic data distribution, which can be reflected in the changing demand for information from end users. This means it allows systems to dynamically subscribe/unsubscribe to data streams based on their current needs (Contextual Dissemination). One possibility is to rank information and services using the Value of Information (VoI), a subjective measure that quantifies information’s value to its users. Platforms such as VOICE [

3] use VoI to rank Information Objects (IOs) and data producers based on their relevance and usefulness.

By combining aformentioned solutions, multi-domain IoT environments can achieve secure and efficient data stream distribution while addressing the unique challenges posed by IoT devices and heterogeneous networks. Moreover, the optimal performance and resource utilization can be achieved by enabling context-dependent data dissemination based on its importance and relevance.

The presented needs for ensuring the reliability and security of data exchange bring challenges, the solution of which determines the implementation of IoT. The basic problem remains: how to carry out the acquisition and fusion of data from various sources with different levels of trust and operate in computing environments with varying degrees of reliability and security? To solve it, it is necessary to know the answer to the sub-questions in the first place:

Security gap - How to implement secure data distribution among participants in a federated environment, adhering to the Data-Centric Security paradigm [

4]? This involves ensuring robust data protection starting from the point of origin, maintaining integrity throughout its entire life cycle, and facilitating granular access control mechanisms to enforce strict data permissions.

Identity Management gap - How to manage the identity of devices? How to identify devices?

Real-Time Data Access gap - How to enable the processing and sharing of relevant IOs based on their VoI, importance and relevance within a specified time range?

Resource Allocation gap - How to dynamically allocate resources to effectively manage trade-offs in a data dissemination environment while taking customer key performance indicators (KPIs) into account?

Network Integration and Interoperability gap - How to organize interconnections, especially between unclassified systems (civilian systems) and military systems?

Resilience and Centralization gap - How to ensure data availability in constrained (partially isolated) environments?

The paper addressed several highlighted gaps, including Security, Identity Management, Interoperability, and Resilience. To fulfill these issues effectively, it was essential to integrate various concepts and technologies while considering the security requirements of Federated IoT Environments. This integration involves implementing a data-centric authentication mechanism that employs a unique identity (fingerprint) that can be reliably stored within a DLT. Additionally, establishing a data stream processing system built on a lightweight and manageable pool of microservices, complemented by context-based real-time data dissemination technologies. Consequently, we proposed a multi-layered framework architecture aimed at ensuring the secure and reliable dissemination of data streams within a multi-organizational federation environment. Our framework implements data-centric authentication based on the unique identities of IoT devices. We consider our primary contributions to be as follows:

- (1)

We have developed a novel and practical framework for the secure and dynamic dissemination of data streams within a multi-organizational federation environment utilizing Hyperledger Fabric [

5], Apache Kafka as data queuing technology, along with a microservice processing logic for verifying and disseminating data streams (by utilizing the Kafka Streams API library in Java [

6] and the Sarama library in Go [

7]);

- (2)

We have integrated a hardware-software IoT gateway with a DLT (Hyperledger Fabric) to authenticate IoT devices and verify data streams, which involves the deployment of the Fingerprint Enrichment Layer in conjunction with the Protocol Forwarder (proxy) component;

- (3)

We validated the effectiveness of the proposed framework by conducting extensive performance tests in two Setups: the Amazon Web Services cloud-based and the Raspberry Pi resource-constrained environment.

The remainder of the article is structured as follows: Section II provides an overview of the relevant research that serves as the foundation for our solution. Section III details our multi-layered framework architecture, highlighting its key components and the security and reliability mechanisms employed to enhance confidentiality, integrity, availability, and accountability for data: in-process, in-transit, and at-rest. Section IV outlines the proposed message types and key operations of our experimental framework. Section V introduces two configurations of our environment: one cloud-based and the other resource-constrained, along with benchmarks for latency metrics. Section VI presents a thorough discussion of the results we obtained. Section VII summarizes our conclusions and delineates our goals for future work. Lastly, the abbreviations used throughout this publication are defined at the end.

2. Related Work

This section presents related works that have had the greatest impact on the proposed framework architecture for secure and reliable data stream dissemination in the Federated IoT Environments. These works address the basic problems related to:

securing data processed by IoT devices with the usage of distributed ledger technology and blockchain mechanism;

behavior-based IoT device identification (IoT distinctive features);

the integration of heterogeneous military and civilian systems based on IoT devices, where specific KPIs must be achieved (e.g., zero-day interoperability).

Additionally, at the end of this section, we have briefly discussed our solution against the analyzed works.

2.1. Blockchain-Based Device and Data Protection Mechanisms

The literature presents numerous attempts to integrate the IoT and blockchain (distributed ledger) technology. The work [

8] describes the challenges and benefits of integrating blockchain with the IoT and its impact on the security of processed data. Similarly, in the works [

9,

10], where a proposal for a 4-tier structural model of Blockchain and the IoT is presented.

Guo et al. [

11] proposed a mechanism for authenticating IoT devices in different domains, where cooperating DLTs operating in the master-slave mode were used for data exchange. Xu et al. [

12] presented the DIoTA framework based on a private Hyperledger Fabric blockchain, which was used to protect the authenticity of data processed by IoT devices.

The work [

13] proposed an access control mechanism for devices, which used the Ethereum public blockchain placed in the Fog layer and public key infrastructure based on elliptic curves. Furthermore, NIST has defined Attribute-Based Access Control (ABAC) [

14] as a logical access control method that authorizes actions based on the attributes of both the publisher and the subscriber, the requested operations, and the specific context (current situational awareness).

H. Song et al. [

15] proposed a blockchain-based ABAC system that employs smart contracts to manage dynamic policies, which are crucial in environments with frequently changing attributes, such as the IoT. Additionally, Lu Ye et al. [

16] introduced an access control scheme that integrates blockchain with ciphertext-policy attribute-based encryption, featuring fine-grained attribute revocation specifically designed for cloud health systems.

2.2. Fingerprint Sampling Techniques

Apart from classification methods for identifying a group or type of similar IoT devices [

17], an interesting area of research is fingerprint techniques [

18,

19], which aim to identify a unique image of a device’s identity through appropriate selection of its distinctive features. The fundamental premise of fingerprint methods is the occurrence of manufacturing errors and configuration distinctions, which implies the non-existence of two identical devices. Subsequently, the main challenge associated with fingerprinting techniques is the selection of non-ephemeral parameters that make it possible to distinguish devices uniquely. Generally, three main fingerprint method classes can be identified for IoT devices as a result of distinction:

Hard/Soft-ware class - hardware and software features of the device;

Flow class - characteristics of generated network traffic;

RF class - characteristics of generated radio signals.

The authors of the LAAFFI framework [

20] presented a protocol designed to authenticate devices in federated environments based on unique hardware and software parameters extracted from a given IoT device.

Concerning distinctive radio features, Sanogo et al. [

21] evaluated the Power Spectral Density parameter. The work [

22] indicates a proposal to use neural networks to identify devices based on the Physical Unclonable Function in combination with radio features: frequency offset, in-phase (I) and quadrature (Q) imbalance, and channel distortion.

Charyyev et al. [

23] proposed the LSIF fingerprint technique, where the Nilsimsa hash function was used to determine a unique IoT device network flow. In contrast, the work of [

24] demonstrated the Inter-Arrival Time (IAT) differences between successively received data packets as a unique identification parameter.

2.3. Reliable Data Streams Dissemination

In addressing one of the primary challenges of deploying various IoT devices within Federated Environments, which necessitates the processing of vast data streams in a secure, reliable, and context-dependent manner, we undertook a thorough analysis of relevant literature on this subject. Our emphasis was also on developing solutions to the sub-questions outlined in

Section 1, particularly those concerning the gaps in Real-Time Data Access, Network Integration, Interoperability, and Security, all of which can be effectively tackled with a Data-Centric approach.

Notably, NATO countries continually refine their requirements (KPIs) to address mentioned challenges. Moreover, they establish research groups dedicated to identifying optimal solutions for coalition data dissemination systems within the framework of Federated Mission Networking.

Jansen et al. [

25] developed an experimental environment involving four organizations, where data is distributed across two configurations. The first configuration employs two types of MQTT brokers: Mosquito and VerneMQ. In contrast, the second configuration operates without brokers, broadcasting MQTT streams using a connection-less protocol (e.g., User Datagram Protocol, UDP).

Suri et al. [

26] performed an analysis and performance evaluation of eight data exchange systems utilized in mobile tactical networks, revealing that the DisService author’s protocol significantly outperforms alternatives such as Redis and RabbitMQ. Additionally, another study [

27] suggests a data exchange system for IoT devices based on the MQTT protocol, incorporating elliptic curve cryptography for data security.

Furthermore, Yang et al. [

28] introduced a system architecture designed for anonymized data exchange among participants, leveraging the Federation-as-a-Service cloud service model and built upon the Hyperledger Fabric.

2.4. Discussion

Although the previously aforementioned publications provide solutions for data access management, data exchange systems, and device/data authentication methods, a notable gap exists for a data dissemination system tailored for dynamic and distributed environments, such as the Federated IoT. Furthermore, there is a lack of systems that incorporate device authentication techniques based on unique fingerprints while ensuring data protection in accordance with the Data-Centric paradigm.

In our literature analysis, we have not identified a solution that effectively combines components of a distributed ledger (specifically, Hyperledger Fabric), data queue systems (like Apache Kafka), and stream processing microservices to address the identified gap in data dissemination.

Most of the reviewed publications rely on a trusted third-party infrastructure and a private DLT to enhance the security of processed data. In contrast to the approaches taken by Guo et al. (master-slave chain) and Xu et al. (DIoTA framework), our solution utilizes a single global instance of the distributed ledger. This allows for the seamless transfer of devices between organizations within the federation, enabling these devices to use another organization’s infrastructure for secure data dissemination.

The studies [

25,

26] do not assess data queue technologies like Apache Kafka. Moreover, they concentrate solely on efficient data exchange and overlook the security of data streams. In our proposed solution, it is feasible to implement Attribute-Based Access Control while concurrently adhering to the Data-Centric paradigm [

4].

Furthermore, we have prioritized interoperability between military and civilian systems, particularly considering the limitations of such environments. To this end, our proposed system incorporates recommendations from the NATO IST-150 working group [

25], which examined disconnected, intermittent, and limited (DIL) tactical networks. Our system employs a publish-subscribe model and utilizes Commercial Off-The-Shelf (COTS) components that are widely available, thereby minimizing operational costs, which is crucial for ensuring immediate interoperability.

Additionally, our work distinguishes the key used for securing the communication channel of IoT devices from the key used for data authenticity protection. Unlike the DIoTA framework, which employs an HMAC-based commitment scheme with randomly generated keys for message authentication, we propose using the unique fingerprint samples of the device. Specifically, we propose to utilize a sealing key as a hybrid identity image based on a combination of several fingerprint method classes.

Finally, our framework (specifically, streams microservices) can be enhanced with components that analyze, classify, and share data streams based on the specific VoI that IOs provide to consumers (context), as well as their relevance [

3].

3. Framework Design

This section outlines our multilayered framework architecture for the reliable dissemination of data streams (messages) within a multi-organizational federation environment that requires the Data-Centric Security approach.

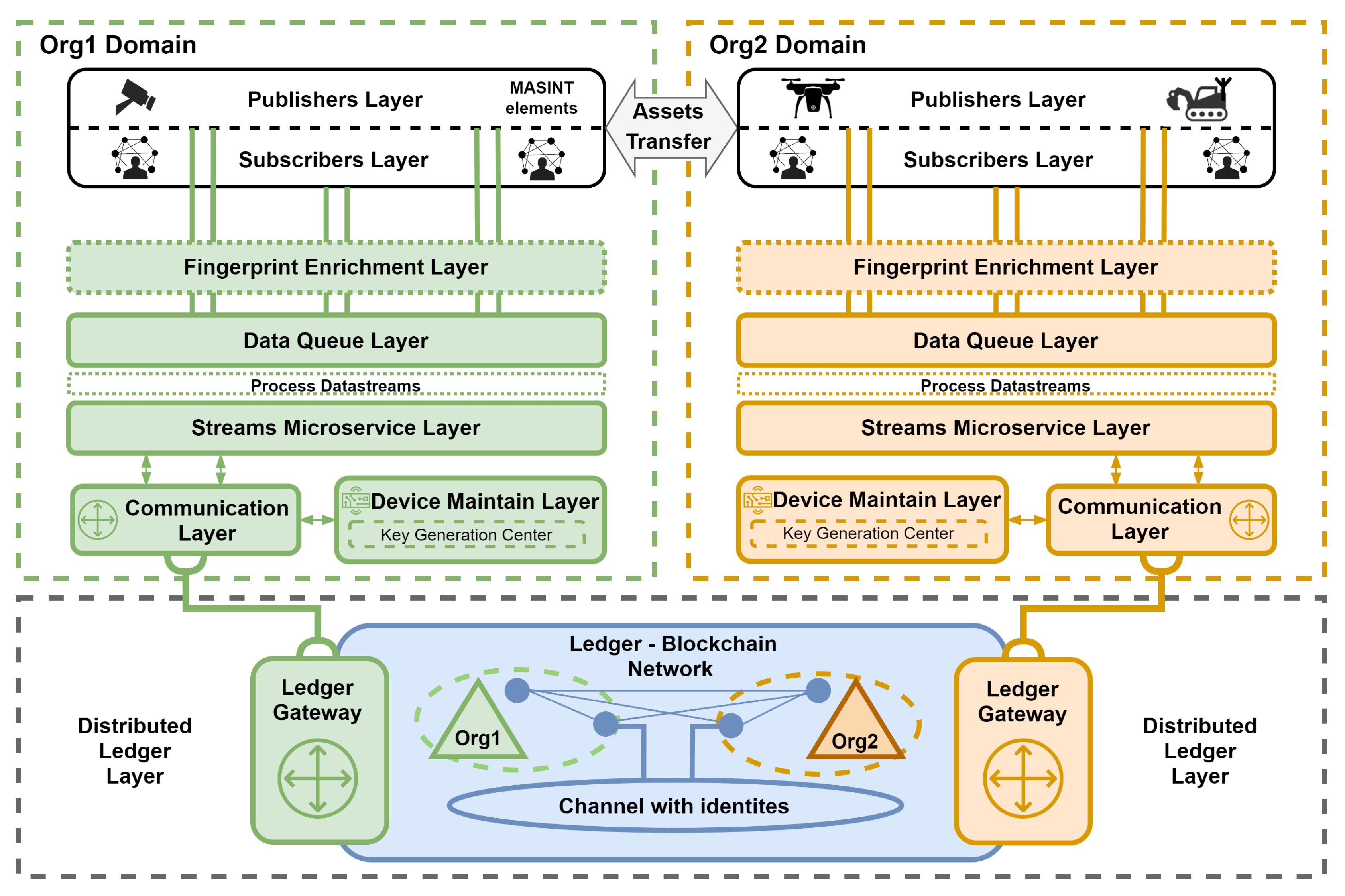

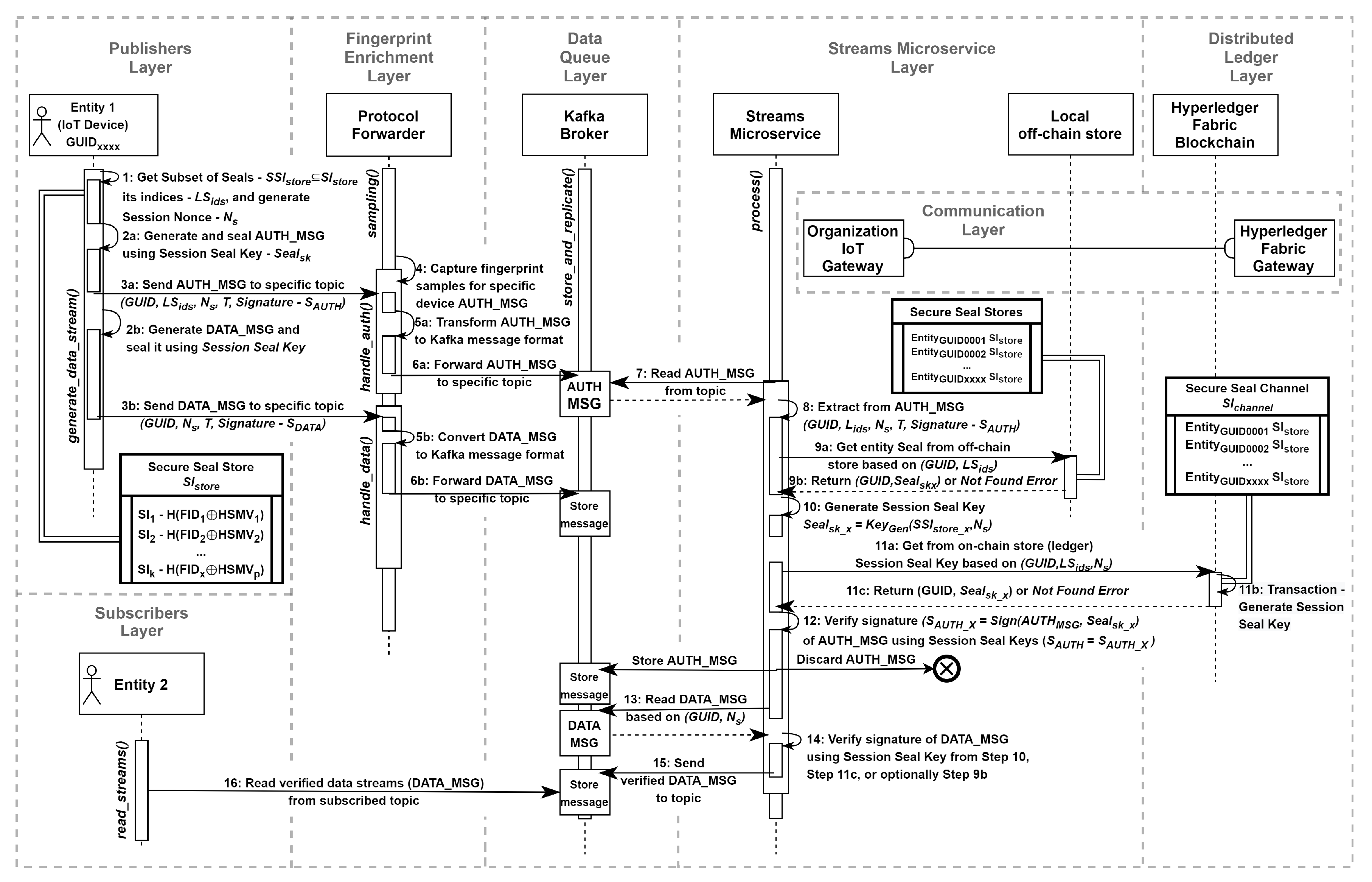

Figure 1 depicts the system’s overall structure of a federation comprising two organizations: Org1 and Org2. As part of our pluggable architecture, we have identified the following layers:

Publishers Layer – encompasses entities that facilitate the data-centric protection of generated (produced) data streams through the sealing process, where the sealing key is derived from the device’s fingerprint (identity) defined during the registration operation managed by the Device Maintain Layer;

Subscribers Layer – is made up of authenticated and authorized entities that read (consume) available and verified data streams from the Data Queue Layer according to the access policy (e.g., one to many);

Data Queue layer - is composed of distributed data queues that facilitate the acquisition, merging, storage, and replication of data streams transmitted from the Publisher’s Layer, subsequently making it accessible to the Subscribers Layer;

Fingerprint Enrichment Layer - can transport connection-less protocols like UDP by employing a Protocol Forwarder that converts data streams into a connection-oriented format (e.g., Transmission Control Protocol, TCP). This layer is essential due to the constraints of the connection types supported by the technologies available for the Data Queue Layer. Moreover, it facilitates device behavior-based authentication by utilizing analyzers to gather various features, including network and radio characteristics, and by enriching messages with entity fingerprint samples;

Distributed Ledger Layer - enables interchangeable deployment of various DLT. Furthermore, it reliably stores the identities of devices belonging to organizations within the federation and retains information about entity Data Quality and subscribers Data Context Dissemination [

29];

Communication Layer - enables the Streams Microservice and the Device Maintain Layer to communicate with the Distributed Ledger via a hardware-software IoT gateway;

Streams Microservice Layer - is tasked with verifying sealed data streams originating from entities within the Publisher’s Layer. Additionally, it has the capability to analyze, categorize, and disseminate streams pertinent to these entities, and enrich them (e.g., by detecting objects during image processing);

Device Maintain Layer – manages device registration operation, with additional responsibilities including updating and revoking identities. The registration process initiates with the establishment of the entity’s identity through the use of fingerprint methods.

In this article, we proposed the adoption of specific technologies to address the various layers of our system.

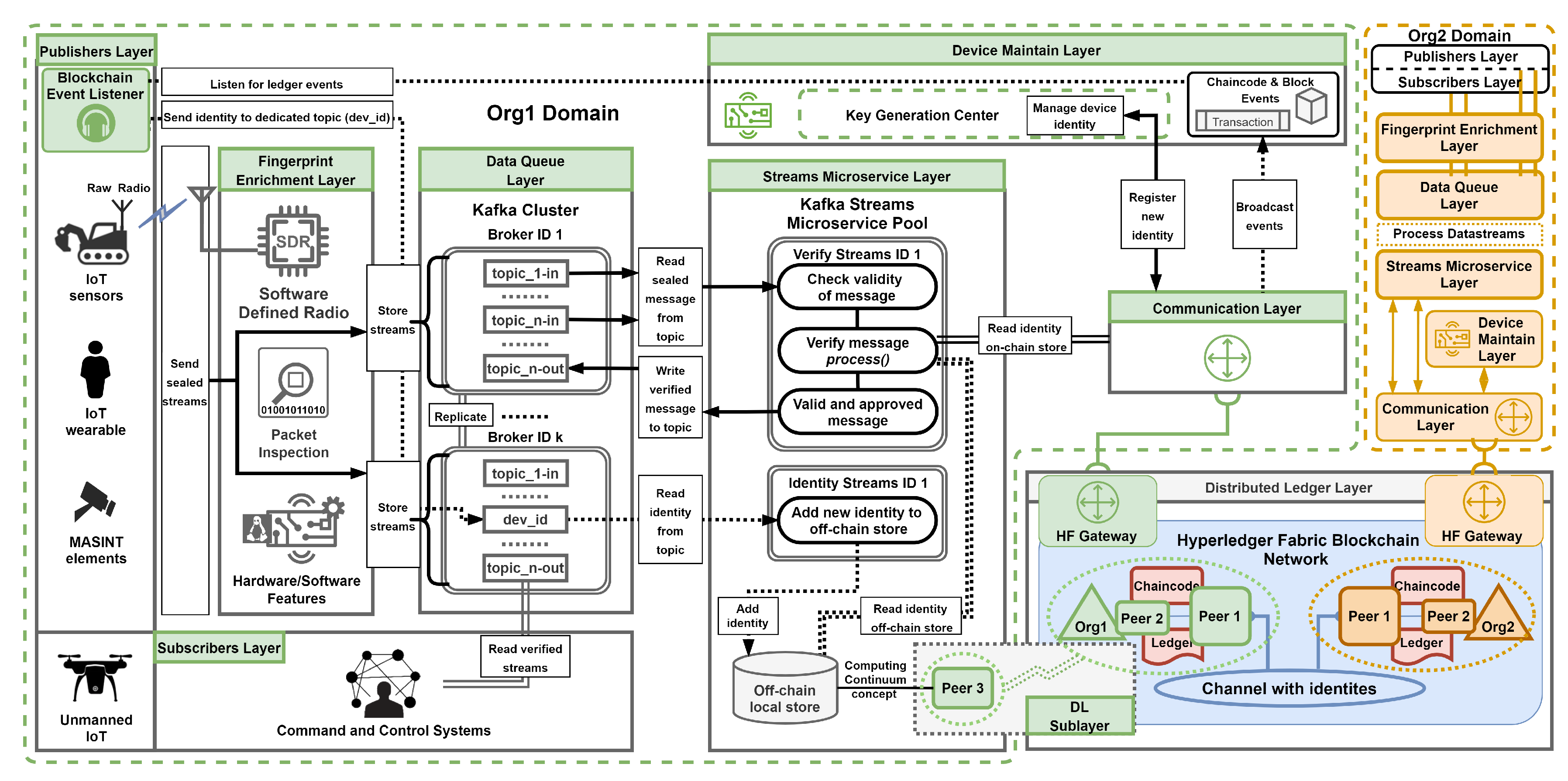

Figure 2 illustrates our architecture, which takes advantage of open-source platforms and libraries. For the Distributed Ledger Layer, we selected the Hyperledger Fabric solution. In the Data Queue Layer [

5], we deployed the Apache Kafka stream-processing platform [

6]. Finally, for the Streams Microservice Layer, we implemented two the same streams processing logic utilizing the Kafka Streams API library in Java [

6] and the Sarama library in Go [

7].

Our architecture is thoughtfully designed to enhance interoperability, facilitating the seamless transfer of devices between the Publishers and Subscribers Layers across diverse organizations (

Figure 1). This approach enables these devices to utilize various organization Data Queue Layers, ensuring secure and reliable data dissemination in any configuration that aligns with predefined policies, such as one-to-many relationships.

Entities representing the Publisher’s Layer ensure the security of their data streams by sealing them with identities registered within the Device Maintenance Layer. These sealed streams are transmitted using the available (supported) communication protocols and mediums to the Data Queue Layer (Kafka Cluster). In this layer, the streams are stored under a specific topic, such as topic_1-in. Additionally, the Fingerprint Enrichment Layer participates (proxies) in transmission utilizing transformation of connection-less messages into a connection-oriented message format.

The subsequent step occurs in the Streams Microservice Layer, which sequentially retrieves messages from the brokers to verify the sealed messages. The Verify Streams Microservice queries the Distributed Ledger Layer (Hyperledger Fabric) through the Communication Layer (IoT gateway) to obtain an image of the device’s identity. Next, the identity extracted from the message is compared with the one stored in the ledger.

Once a message is verified and approved, it is written back to the Kafka Cluster under a dedicated topic, such as topic_1-out, making it accessible to entities representing the Subscribers Layer. Optionally, any rejected messages during this process can be directed to a separate topic to aid in identifying and detecting potentially malicious devices.

As previously mentioned, a device identity image is critical to the verification process. The Device Maintenance Layer encompasses a registration operation through the Key Generation Center, during which the device identity is established using hybrid fingerprint techniques. These techniques determine the specific hardware and software features, generated network characteristics, and radio signals related to the device. Once the identity is defined, it is redundantly added (stored) in the Distributed Ledger Layer through the execution of chaincode (group of smart contracts). Successful registration is contingent upon achieving consensus among the participating federated organizations.

Moreover, within our framework, we have delineated two categories of data stores: the on-chain store and the off-chain store. The on-chain store refers to the ledger, while the off-chain store encompasses local storage utilized by applications and microservices, such as those leveraging the Kafka Streams API library. One of our key proposals is to employ the off-chain store as a micro-caching mechanism to store identities from the on-chain store temporarily. This mechanism can significantly mitigate the delays associated with ledger queries and improve the overall performance of an individual instance of the Verify Streams Microservice.

To realize this, we proposed a minor extension to our environment. In the Publisher’s Layer, a dedicated listening application known as Blockchain Event Listeners can be utilized to manage events emitted from the Distributed Ledger Layer. These events will pertain to ledger operations, including device registration, updates, and revocations. Furthermore, a dedicated topic such as dev_id, specifically for storing these events, can be established. Subsequently, the Identity Streams Microservice can be deployed to add or update identities in the off-chain store. Additionally, by enforcing appropriate retention policies for this designated topic, we can preserve historical event-based records of device identity changes, functioning as a blockchain-topic.

Alternatively, the off-chain store can be integrated with the Continuum Computing concept (CC) [

3] which involves providing computing capabilities across the diverse layers of an IoT system (edge, fog, and cloud). The fundamental notion of this concept is to relocate high-performance cloud-based services to lower layers. While this escalates resource management’s complexity, it facilitates deploying services that demand ubiquitous and efficient computing capabilities. The concept also aims to optimize resource allocation, ensuring that devices perform service tasks as close as possible to data sources.

In the realm of computing modeling, our system is designed to process incoming requests sequentially to minimize the decay of Information Objects. Our architecture facilitates the dynamic deployment of microservices at all layers of the IoT system, offering both horizontal and vertical scaling for resource allocation. It also accommodates various deployment contexts.

The upcoming headings will provide an in-depth overview of the mentioned layers, along with mechanisms that enhance confidentiality, integrity, availability, and accountability for data: in-process, in-transit, and at-rest. Furthermore, a thorough analysis of the built-in security and reliability features associated with each specified technology will be provided.

3.1. Publishers Layer

The Publisher Layer encompasses entities that facilitate the data-centric protection of generated data streams through symmetric encryption and sealing operation. This leverages digital signatures and the device’s hybrid identity. Although the selection of encryption and digital signature algorithms is not the primary focus of this study, it invites consideration of the potential applications of lightweight and quantum-resilient cryptography. In 2022, NIST evaluated and approved two quantum-resistant algorithms for digital signatures [

30]: FALCON and SPHINCS+. These algorithms utilize distinct mathematical approaches: lattice and hash systems, respectively. In our research, however, we opted for well-established algorithms such as AES for encryption and HMAC for signatures. Devices with limited resources, like the Raspberry Pi, have adequate computational power to perform the cryptographic operations required by these algorithms.

3.2. Subscribers Layer

The Subscribers Layer comprises entities that have been granted authorized access to the Data Queue Layer. Our framework’s architecture is designed to ensure the reliable dissemination of data across all levels of command: tactical, operational, and strategic. Additionally, the framework enables seamless data sharing across different domains within a federation, which includes allied forces and civilian institutions, fostering collaboration and coordinated efforts toward common objectives. Moreover, our system adeptly manages data security along the path from producer to consumer, while also implementing fine-grained access control mechanisms.

3.3. Data Queue Layer

The layer in the headline holds a pivotal position within our system, performing a multitude of important functions such as:

storing and replicating sealed data streams within the layer;

storing invalid records to trigger a detection mechanism of potentially malicious entities;

intermediating within the micro-caching mechanism by linking the Publisher Layer (Blockchaine Event Listeners) with the Streams Microservice Layer.

The Publisher’s layer comprises numerous data sources, each generating real-time data streams that require processing. To facilitate the seamless processing of these messages, the Apache Kafka solution has been used. For example, Kul et al. [

31] have introduced a framework that leverages Kafka and neural networks to monitor (track) vehicles. In their study, the dataset was represented as data streams captured by CCTV.

Apache Kafka is a stream-message system that utilizes a producer-broker-consumer (publish-subscribe) model and classifies messages based on their topics. The Kafka Cluster is composed of message brokers that acquire, merge, and store data generated from the Publishers Layer (producers), and make it available to the Subscribers Layer (consumers). The layer is designed for the availability and reliability of data records, thanks to built-in synchronization and distributed data replication between brokers. Furthermore, it leverages serialization and compression mechanisms, such as lz4 and gzip, making messages payload format- and protocol-independent.

Furthermore, Kafka technology incorporates built-in components and mechanisms for defining and managing entity authorization through Access Control Lists (ACLs). Essentially, ACLs outline which entities can access specific resources (topics) and delineate allowed operations (e.g, READ, WRITE) to perform on those resources. Establishing a distinct principal for each entity (device) and assigning only the necessary ACLs, enables the processes of debugging and auditing leading to the identification of which entity executes each operation.

However, large Kafka Cluster topologies that involve multiple publishing and subscribing entities (numerous topics) often encounter significant challenges in managing entity authorization. Although it is feasible to implement a more intricate authorization hierarchy within the cluster. This can imply an additional operational burden. In the previous article [

4], we explored the application of ABAC in our environment. This solution can alleviate the authorization burden on the Kafka Cluster, thereby freeing its internal resources and allowing the Streams Microservice Layer to manage access control more efficiently.

3.4. Fingerprint Enrichment Layer

A notable limitation of Kafka technology is its dependence on connection-oriented protocols, specifically the TCP. In contrast, our framework requires the ability to communicate with entities utilizing connection-less protocols, such as the UDP. To address this challenge, we propose the introduction of a Fingerprint Enrichment Layer. A fundamental component of this layer is a Protocol Forwarder, which is designed to handle connection-less messages and convert them into a connection-oriented message format.

Furthermore, the mentioned layer can contribute to device behavior-based (fingerprint-compliance) authentication. This can be accomplished through the utilization of dedicated components, referred to as analyzers, which gather radio signal, network flows, and hardware features. For the radio fingerprinting analyzer, we propose employing a Software Defined Radio. This system replaces or supplements traditional hardware components, such as mixers, filters, amplifiers, and detectors, with software-based Digital Signal Processing techniques. Providing flexibility, cost-effectiveness, versatile wideband reception, and enhanced interoperability within our architecture and radio communication systems. For the network analyzer, we can capture distinctive features from the headers of TCP/IP layers through comprehensive packet inspection. A detailed description of the proposed analyzers subsystem is beyond the scope of this publication and will be the subject of our future research.

3.5. Distributed Ledger Layer

Our experimental framework features a pluggable structure that allows for the interchangeable deployment of different DLTs. The Distributed Ledger Layer indicates several functions such as:

redundant and reliable storing of all identities of devices belonging to organizations that participate in the federation;

redundant and reliable storing information about entities regarding the Value of Information and the Context Dissemination;

secure handling of the chaincode (smart contracts) execution (transaction steps) during the device registration operation;

obtaining approvals (transaction authorizations) under endorsement policy from participating organizations;

generating events related to actions on distributed ledger (blockchain);

being an integrated part of the verification process of devices and sealed messages.

Based on a performance comparison, we have opted to integrate the Hyperledger Fabric technology with our system. This particular technology has achieved a transaction throughput of 10,000 tps, as documented in [

8]. It is noteworthy that the Ethereum ledger had a lower throughput. However, for Ethereum, only the Proof of Work consensus protocol was examined. Whereas the currently less energy-intensive and scalable Proof of Stake consensus was not covered in these experiments.

The Fabric DLT adopts the Practical Byzantine Fault Tolerance consensus algorithm, which mandates that all participating parties know of one another. As a consequence, it is a permission blockchain where public key infrastructure is deployed. To register the identity of devices, complex business logic is executed using multilingual chaincode (Go, Java, Node.js). Moreover, the target execution environment for chaincode is a Docker container and its resources can be controlled (e.g., limited, isolated) through a Linux kernel feature cgroups. Also, private data channels can be created between organizations, where the identity of selected devices can be hidden from other organizations.

The on-chain store used in Fabric technology consists of systematically organized structures: world state and transaction log. The world state serves as the ledger’s current state database, while the transaction log acts as a Change Data Capture mechanism. This mechanism incrementally records both approved and rejected transactions, ensuring that data at-rest is secure and accountable.

3.6. Communication Layer

The hardware-software IoT gateway manages communication between the Device Maintain Layer, the Streams Microservice Layer, and the Distributed Ledger Layer via an interface to the Hyperledger Fabric Gateway services [

5] that run on the ledger nodes. The Communication Layer facilitates the seamless communication exchange for:

performing queries to the on-chain store to read the examined identity from the Distributed Ledger Layer during the verification process;

participating in entity identities registering, updating, and revoking operations called by the Device Maintain Layer;

broadcasting of events generated by the Distributed Ledger Layer as a result of approved transactions and blocks.

The IoT gateway utilizes a dynamic connection profile with the Distributed Ledger Layer. This profile leverages the internal capabilities of ledger nodes to detect alterations in the network topology in real-time, thus ensuring the seamless functioning of the Streams Microservices Layer, even in the event of node failure. Furthermore, the checkpointing mechanism proves to be beneficial, as it enables uninterrupted monitoring of ledger events without the risk of data loss due to connection interruptions.

3.7. Streams Microservice Layer

The Streams Microservice Layer is responsible for verifying sealed messages originating from entities within the Publisher’s Layer. This layer is notable for executing complex operations on individual messages (records) in a sequential manner. To enhance the efficiency of message (stream) processing, selecting an appropriate framework or library is essential. Evaluations conducted by Karimov et al. [

32] and Poel et al. [

33] assessed various solutions designed for this purpose. Both studies concluded that the Apache Flink framework outperformed alternatives such as Kafka Streams API, Spark Streaming, and Structured Streaming, earning the highest overall ranking.

However, our proposed system architecture leverages the Streams API library to define custom verification processing logic. This choice is based on the inherent advantages of Kafka technology, including its failover and fault tolerance features. The Streams API library offers two approaches for implementing processing logic: the high-level Streams DSL and the low-level Processor API. We chose the Processor API for its pluggable architecture, which facilitates the deployment of various types of local off-chain stores. Moreover, the library employs a semantic guarantee pattern that ensures each message is processed exactly once from start to finish, thereby preventing any loss or duplication of messages in the event of a stream processor failure.

We opted against using the Spark and Structured Streaming frameworks as they rely on micro-batching, which processes messages within fixed time windows. Similarly, we did not consider the Apache Flink framework because it requires a separate processing cluster, which would increase operational costs for infrastructure deployment and negatively impact interoperability.

It is essential to highlight that our experimental system can further leverage the Kafka Streams API to support a range of tasks, including Data Enrichment, Data Quality Assessment, and Data Context Dissemination. In particular, this capability can be applied to object detection and classification during image processing.

Figure 3 showcases the integration of our system for the mentioned use case.

3.8. Device Maintain Layer

The primary function of the Device Maintain Layer is to manage device registration operations, with additional responsibilities including updating and revoking device identity. The registration process begins with establishing the entity’s identity through hybrid fingerprint techniques. Entities of the Publisher’s Layer will use these identities during the sealing process, where the device identity image working as a key will be used with digital signatures to seal data streams sent to the Data Queue Layer.

In the process of defining entity identity, we advocate for the use of a Confidential Computing strategy [

34] that incorporates the Defense-in-Depth and Hardware Root of Trust concepts. This strategy involves the implementation of multiple heterogeneous security layers (countermeasures) that are built on highly reliable hardware, firmware, and software components. These countermeasures are essential for executing critical security functions, such as session key generation and the secure storage of cryptographic materials, ensuring that any adverse operations not detected by one technology can still be identified and mitigated by another.

To safeguard data across its various states – whether in-process, in-transit, or at-rest – secure enclaves, including Trusted Execution Environments (TEEs), Hardware Security Modules (HSMs), or Trusted Platform Modules (TPMs), can be employed. TEEs provide a secure area within the processor, whereas HSMs are specialized hardware created specifically for key storage. Meanwhile, TPMs are hardware chips that offer a range of security functions, including secure key storage and platform (entity) integrity checks.

The specific procedures for key management fall outside the scope of this article. Instead, we propose a general procedure for defining the entity key (identity). During the registration operation, the device administrator places the device in an RF-shielded chamber to minimize potential interference that could impact the radio waves emitted by the device. Using specialized software and measurement equipment, the distinct characteristics of the device undergo a series of tests to establish a unique identity profile. In this study, we proposed a hybrid approach that combines several fingerprinting methods, primarily based on the parameters of the generated radio signals. The rationale for this selection is:

limitations arising from the heterogeneity of the environment and the need to maintain the mobility of IoT devices;

devices’ vulnerability to extreme environmental factors (e.g., temperature, humidity);

autonomy from the protocols used in the network.

The complete entity management process is conducted through the Communication Layer. Once the identity is established, it can be securely stored using the designated storage solutions on the device. Furthermore, the identity will also be recorded in the Distributed Ledger Layer and may optionally be retained in the off-chain stores of the Streams Microservice Layer.

4. Framework Basic Operations

This section delineates the main operations of our experimental framework, conscientiously examining the interrelationships among system layers and the flow of messages. Notably, we have integrated certain elements conceptualized by Jarosz et al. concerning a novel LAAFFI protocol [

20].

4.1. Security Mechanisms and Message Types

As outlined in

Section 3.4, the Fingerprint Enrichment Layer utilizes the Protocol Forwarder Component, which is specifically designed to manage connection-less streams and convert them into a connection-oriented format. This process employs an ETL (Extract, Transform, Load) mechanism, where a series of functions is applied to the extracted data, allowing it to be transformed into a standardized format. Moreover, the producer utilizing a data serialization mechanism, is solely responsible for determining how to convert the data from a specific protocol (such as MQTT) into byte representation. In contrast, the consumer defines how to interpret the byte string received from the broker through the deserialization process.

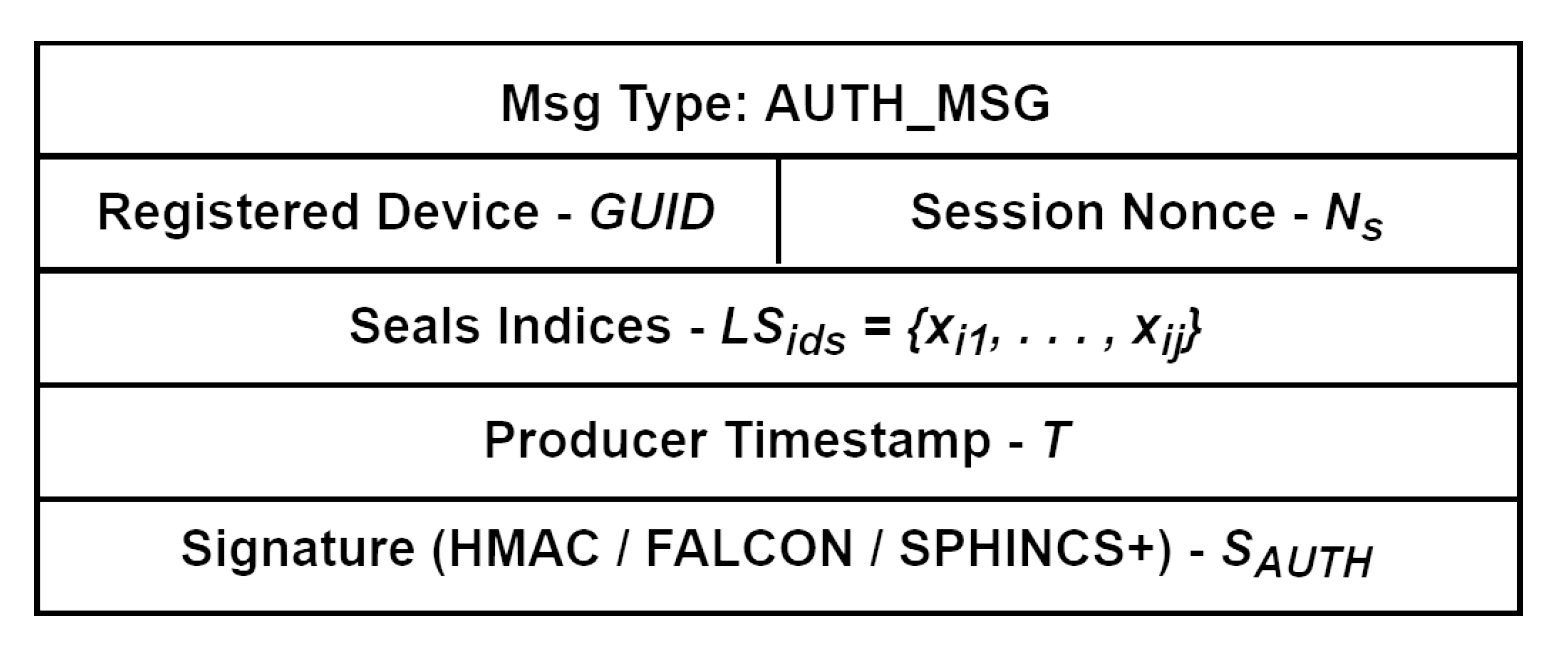

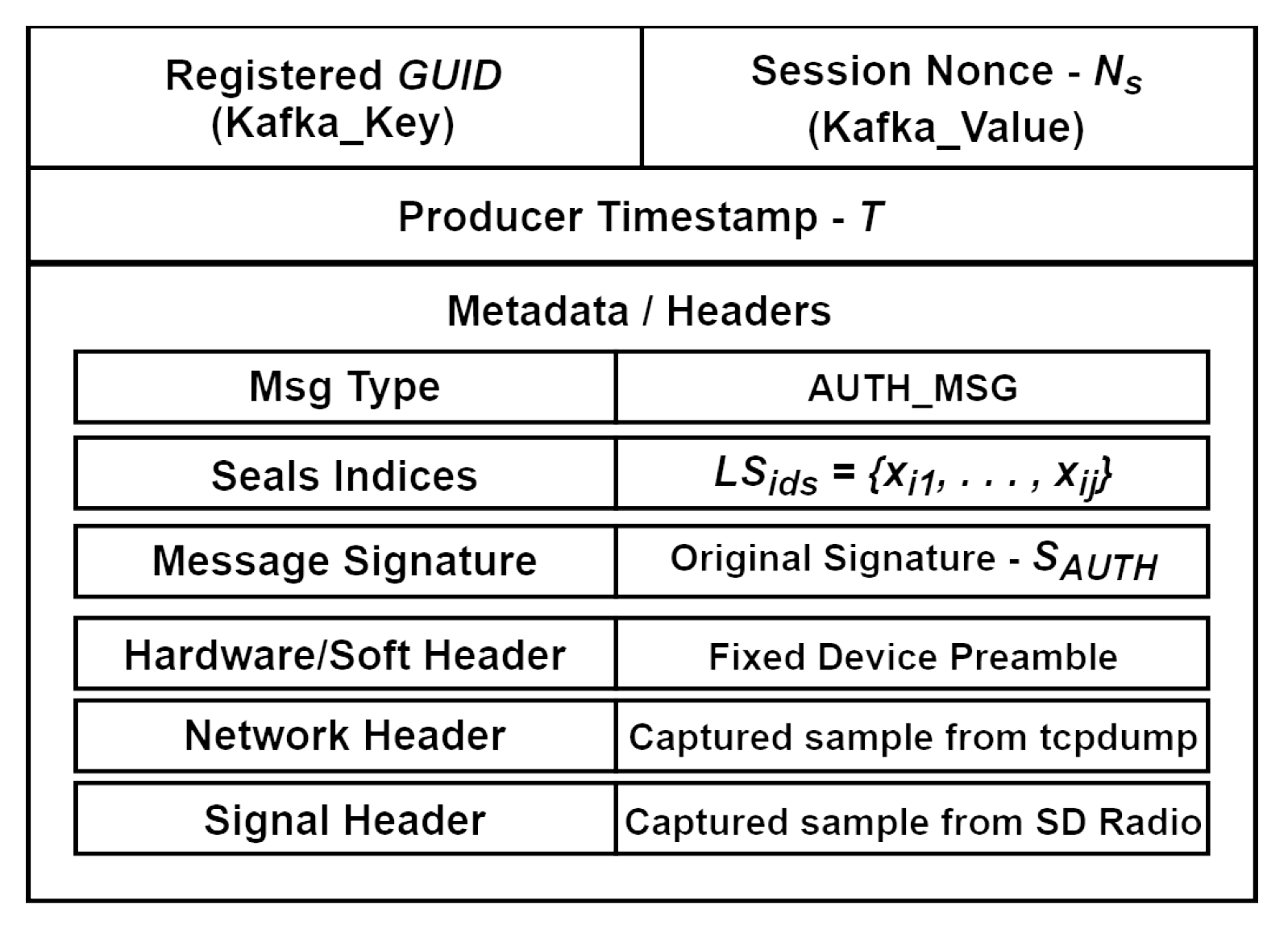

Within our environment, we proposed two primary types of messages that can be assigned to a single data stream. The first type is the data stream authentication message, referred to as AUTH_MSG (

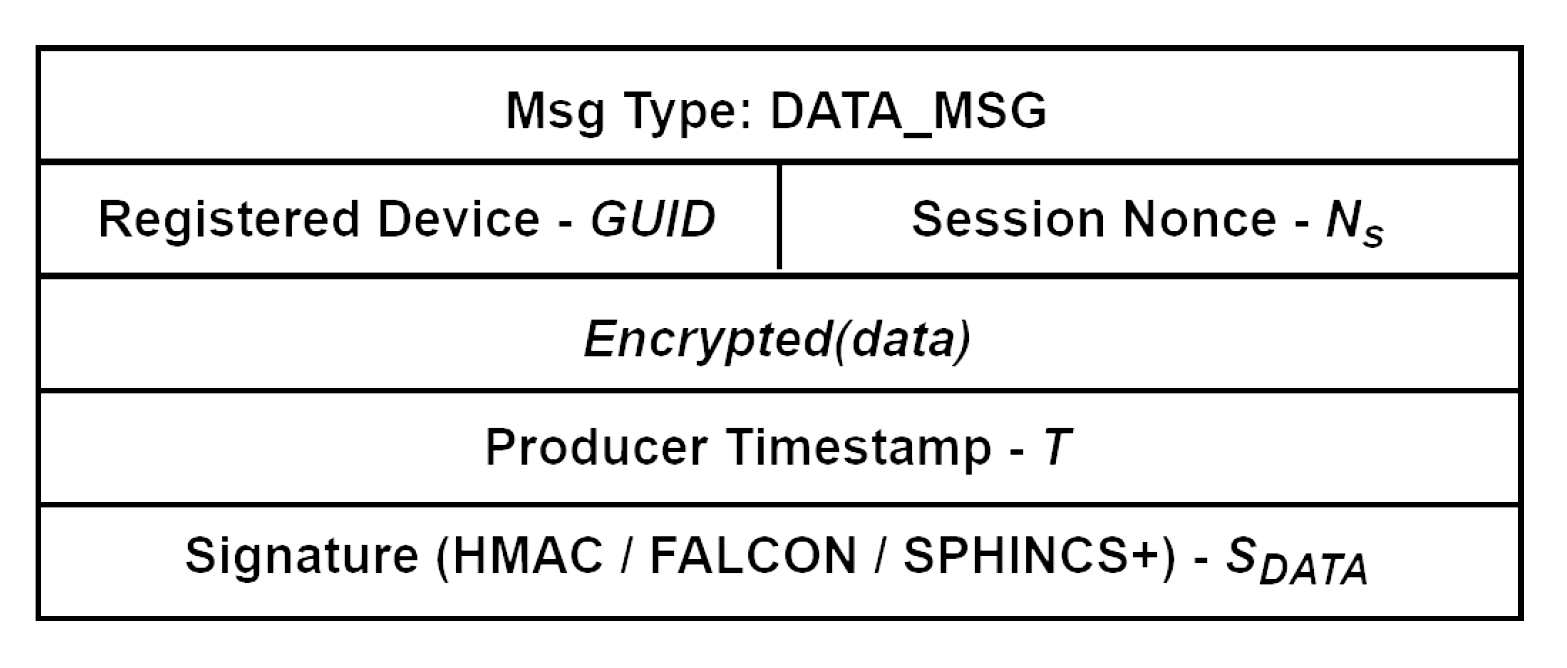

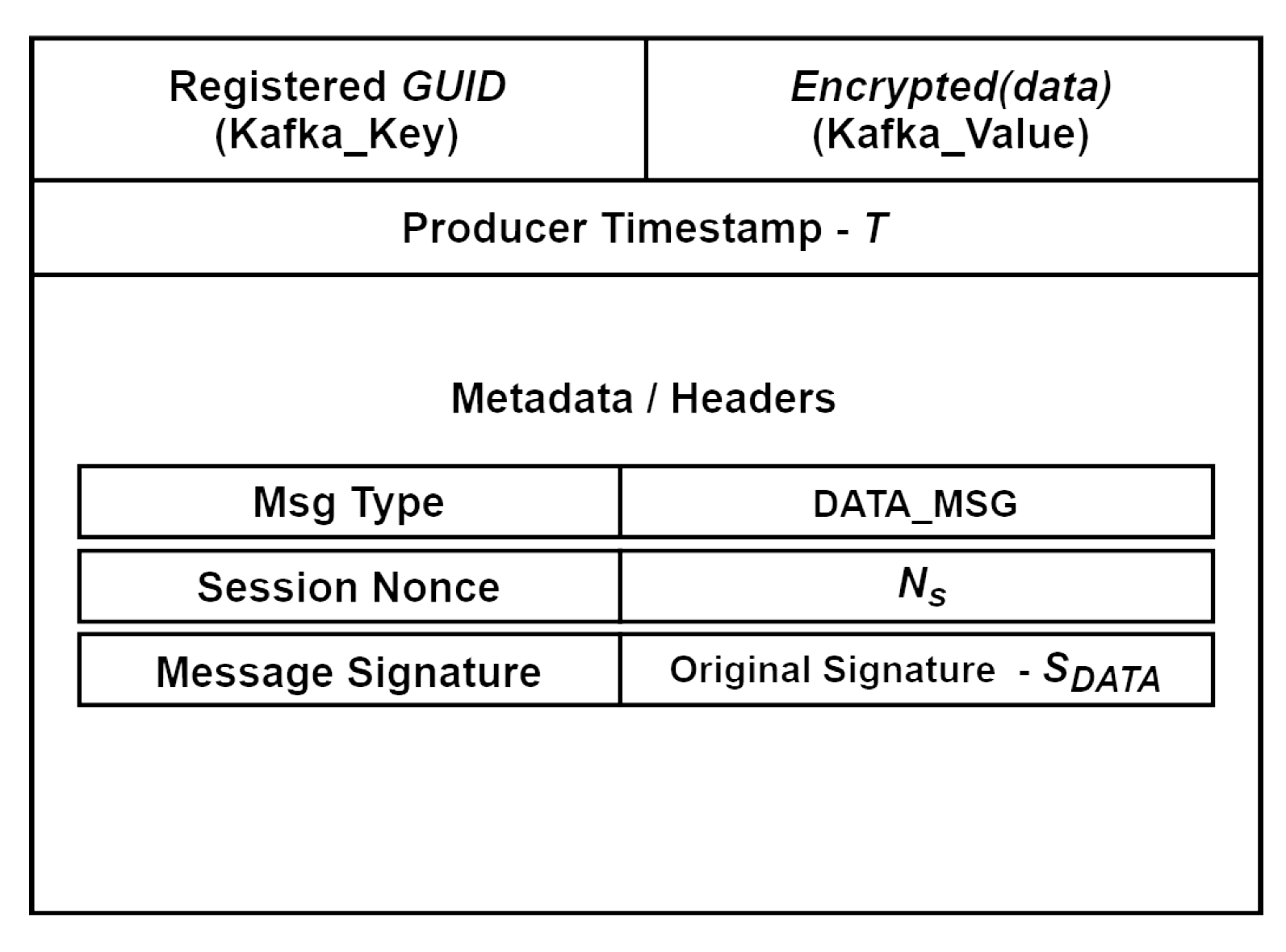

Figure 4). The second type is the session-related data stream message, known as DATA_MSG (

Figure 5). Specific message fields are described below:

Globally Unique Identifier, - is assigned to the entity during the registration process in the Device Maintain Layer. It functions as a unique identifier, ensuring that each device can be distinctly recognized within a set of registered devices. For example, it may be represented as a human-readable combination of the federated organization name, type, and number, such as ORG1-SENSOR-0001;

Session Nonce, - is a unique pseudo-random value generated by the entity that identifies a specific data stream, thus facilitating the correlation between the AUTH_MSG and the DATA_MSG.

Seals Indices, - consist of a subset of indexes for the Seals selected from the Secure Seal Store - , where Seal - . For each specific Seal we proposed to use a hashed exclusive OR multiplication ⊕ of the entity Fingerprint Sample - recorded in the Entity Features Store - combined with internal parameters from the Hardware Security Module - ;

Timestamp, T - is used as a protection mechanism against replay attacks, when the Kafka topic is configured to use CreateTime for timestamps, the timestamp of a record will be the time that the producer sets when the record (message) is created.

Message Signatures, , - are utilized to guarantee both the integrity and authenticity of the data streams. These signatures are compared to signature values calculated during the processing of messages within the Streams Microservice Layer. The Seal - or Subset of Seals - and Session Nonce works in conjunction with a key-derivation function to generate the key for the signature function . The use of signatures fits naturally into the architecture of our system because of the Kafka message format autonomy (independence).

The message structures of AUTH_MSG and DATA_MSG that the Kafka Broker can handle (store, queue) are illustrated in

Figure 6 and

Figure 7. The

Kafka_Key and

Kafka_Value consist of sequences of bytes that form the message. The

Kafka_Key plays a crucial role in directing a message to a specific partition within the Kafka topic. When a key is provided, all messages associated with that key are directed to the same partition, ensuring they are processed sequentially. The

Kafka_Value contains the data that consumers will read and process. Additionally, we have included optional header fields related to the implementation of specialized feature (behavior-based) analyzers deployed within the Fingerprint Enrichment Layer (see

Figure 6).

We acknowledge the critical need to safeguard data throughout its various states, whether in-process, in-transit, or at-rest. In our deployment, we have employed SSL/TLS communication solely between the Streams Microservice Layer and the Distributed Ledger Layer. Our framework follows a data-centric approach, which facilitates the encryption of data stream payloads using AES, along with data authentication through device fingerprints. This approach allows us to bypass the need for communication protection within the Data Queue Layer, particularly among producers, subscribers, and brokers. This decision reduces additional overhead affecting microservice verification latency.

The aforementioned approach, in conjunction with the Kafka serialization and deserialization mechanism, facilitates independent data exchange between producers and subscribers. It is essential to highlight that microservice is unable to access the data payload, as it may be encrypted using a key that has been exchanged in advance between producers and subscribers. Nonetheless, this limitation does not impact the verification process of the data streams. A detailed discussion of this topic was provided in our previous work [

4].

Additionally, to safeguard the

and

during transit, we propose utilizing an encryption mechanism that employs one-time pre-shared keys, which will be securely maintained solely within the entity (e.g., Event Listener) and the microservice instance. To protect these stores in an off-chain environment (at-rest state), we recommend implementing the Confidential Computing strategy and Secure Enclaves, as detailed in

Section 3.8.

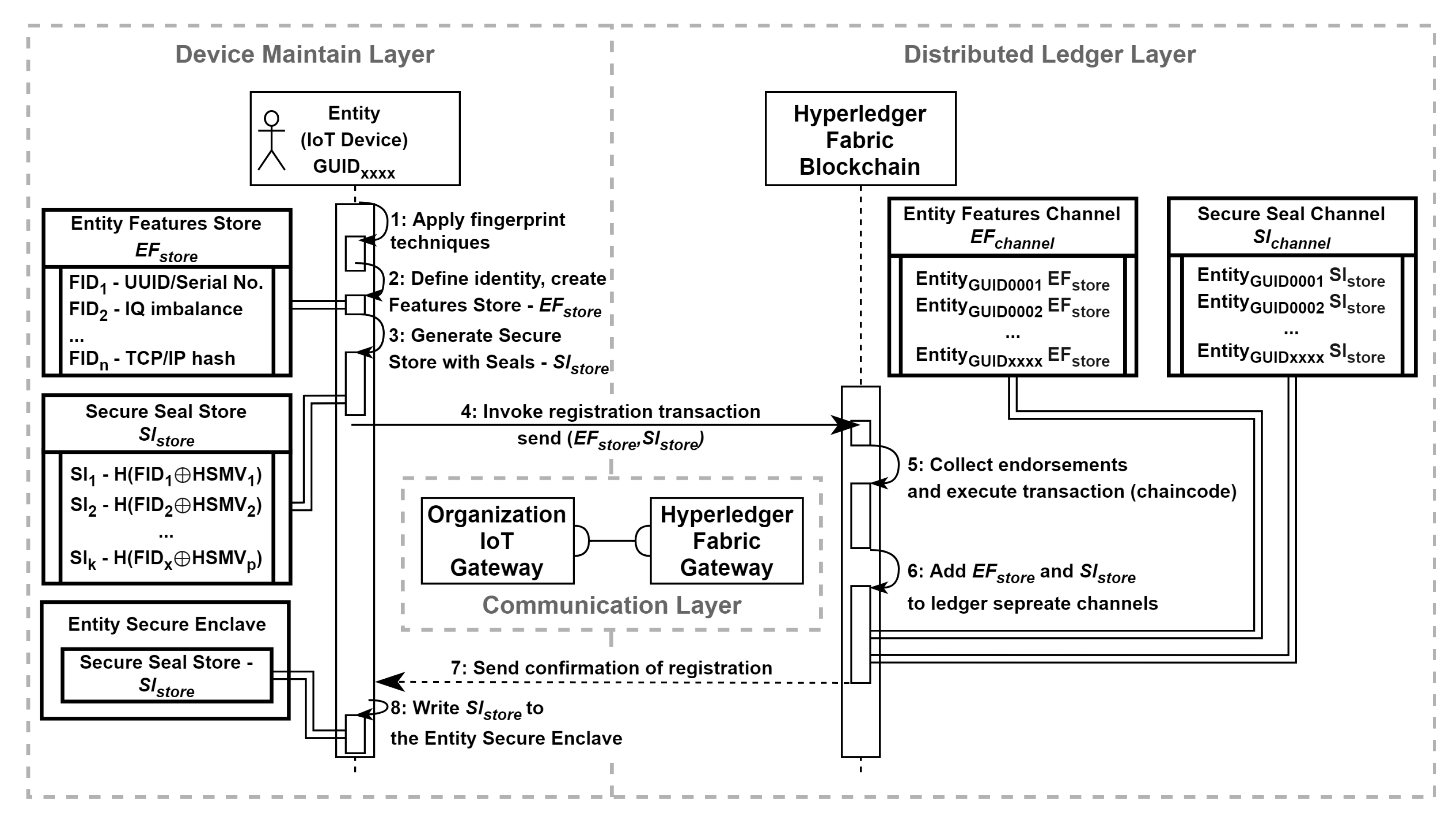

4.2. Entity Registration

The top-level sequence diagram (

Figure 8) outlines the message flow and the specific actions (steps) that are related to the operation of registering entity identity:

Step 1: the device registration process begins with the Device Maintain Layer defining an entity’s identity through hybrid fingerprint techniques. This operation is conducted within a secure enclave (e.g., TEE);

Step 2: the entity’s identity, represented by fingerprint samples is recorded in the Entity Features Store - ;

Step 3: a Set of Seals - is generated based on a subset of fingerprint samples from the Features Store. For each specific Seal - , we proposed to use a hashed exclusive OR multiplication ⊕ of the Feature Sample - combined with internal parameters from the Hardware Security Module - ;

Step 4: the chaincode, a component of the Distributed Ledger Layer that manages the secure transaction of adding a new identity to the ledger, is invoked. This transaction incorporates the Entity Features and Secure Seal Stores as part of its payload .

Step 5: upon receiving the necessary approvals from the organizations specified by the endorsement policy, the transaction is executed. This step is crucial for ensuring the integrity and transparency of the ledger, as it guarantees that all identities are accurately and securely recorded;

Step 6: the Entity Features and Secure Seal Store are recorded in the distributed ledger through separate channels: an Entity Features Channel - and a Secure Seal Channel - , respectively;

Step 7: a confirmation of the registration is sent back to the Device Maintain Layer;

Step 8: considering the Confidential Computing Strategy, the is written to the Entity’s Secure Enclave. Any cached values related to the registration process should be cleared (wiped out).

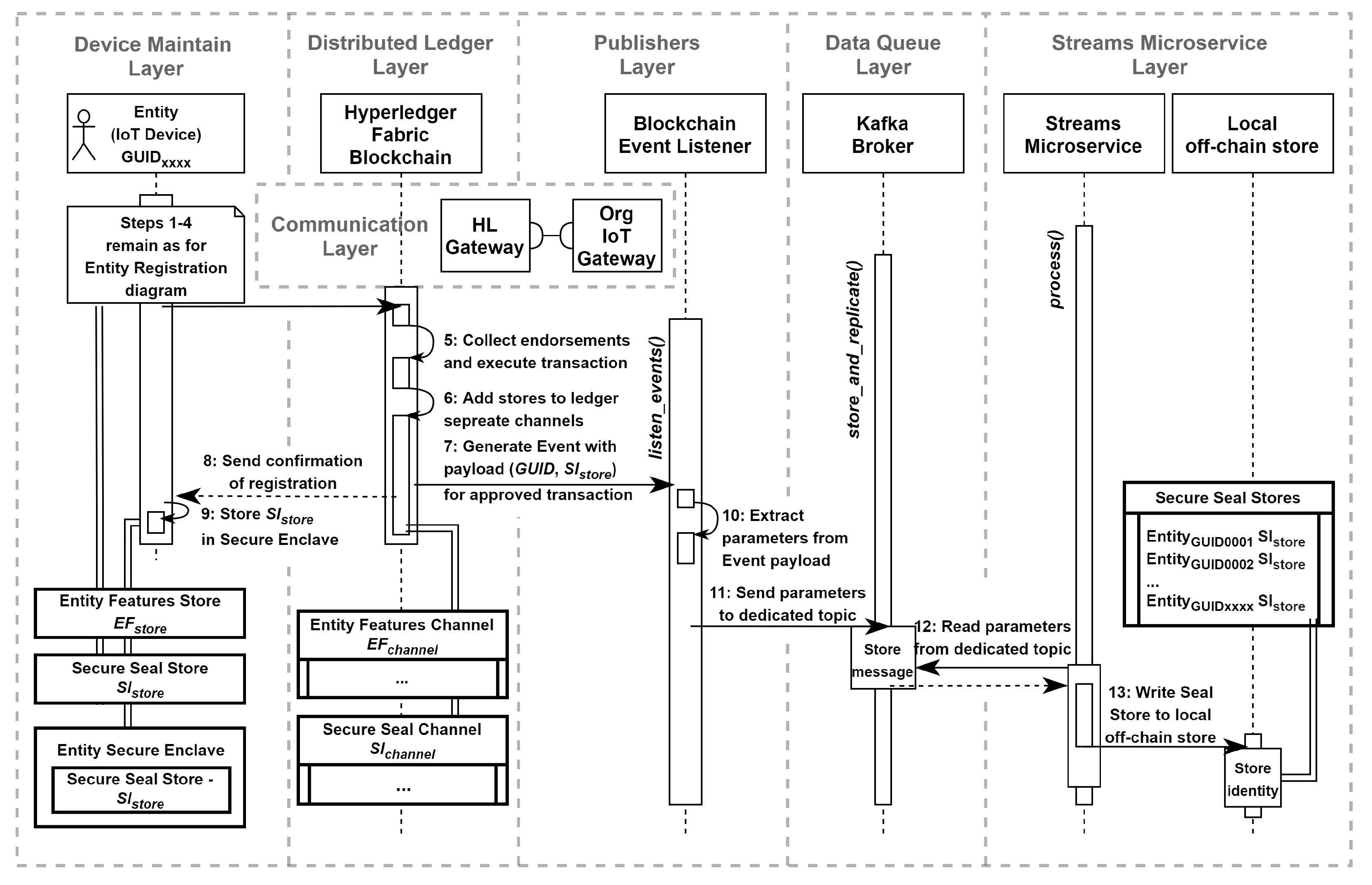

4.3. Blockchain Event Listener Application

As an enhancement to the entity registration operation, we proposed to incorporate device identity into the local off-chain data store, which is a component of the Streams Microservice Layer. This improvement aims to reduce time delays during message verification by eliminating the need for a ledger query step (micro-caching mechanism).

Figure 9 presents a top-level sequence diagram for the operation, illustrating the flow of messages and interactions involved (steps):

Step 1-4: remain as for registering entity identity top-sequence diagram (

Figure 8);

Step 5: upon receiving the necessary approvals from the organizations specified by the endorsement policy, the transaction is executed (the Distributed Ledger Layer);

Step 6: the Entity Features and Secure Seal Stores are recorded in the distributed ledger through separate channels: , ;

Step 7: an application called Blockchain Event Listener monitors events that are emitted by the Distributed Ledger Layer. This application represents a special entity within the Publisher’s Layer. As a result of the approved and executed transaction, the and the Seal Store are written to the Event payload. Then the Event is emitted by the Distributed Ledger Layer.

Step 8: a confirmation of the registration is sent back to the Device Maintain Layer;

Step 9: the Secure Seal Store is written to the entity’s secure enclave (the Device Maintain Layer);

Step 10: the Blockchain Event Listener (the Publisher’s Layer) interprets the occurrence of the Event and the Seal Store is extracted from the Event payload;

Step 11: the Seal Store extracted from the Event payload is written to the Data Queue Layer (Kafka Cluster). The dedicated Kafka topic is utilized for this purpose;

Step: 12: the Streams Microservice Layer reads the Seal Store from the cluster in a sequential manner;

Step 13: during process() method handled by the Streams Microservice Layer the Seal Store is added to the local off-chain data store and can be utilized by other streams microservices within the pool.

4.4. Data Streams Verification

A tailored stream processing algorithm has been proposed. The top-level sequence diagram (

Figure 10) outlines the message flow and the specific actions (steps) that are related to the operation of data streams verification. Additionally, the local off-chain data store has been incorporated into the Streams Microservice Layer, which can enhance the overall performance of the system:

Step 1: when an entity (IoT device) from the Publishers Layer intends to transmit a data stream, it invokes the generate_data_stream() method. During this execution, initial parameters for the cryptographic primitive (sealing) are chosen from the Secure Seal Store - , where Seal - or Subset of Seals - is selected along with its corresponding indices - , and a Session Nonce - is generated;

Step 2a: for the chosen Seal and the Session Nonce, a Session Seal Key is generated . Next, the AUTH_MSG is crafted and sealed using a signature algorithm founded on the specified parameters: ;

Step 2b: subsequently, the session-related data stream messages are sealed using the Session Seal Key generated in Step 2a: ;

Step 3a: the sealed AUTH_MSG is transmitted through a reliable communication channel via the Fingerprint Enrichment Layer to the Data Queue Layer (Kafka Cluster), where it is stored under a designated topic. The AUTH_MSG includes: ;

Step 3b: the sealed DATA_MSG messages are transmitted in the same manner as described in Step 3a. The DATA_MSG contains the ;

Step 4: optionally, within the Fingerprint Enrichment Layer, specialized behavior-based analyzers handle the sampling() method to capture fingerprint samples associated with a specific device’s AUTH_MSG;

Step 5a: the handle_auth() method transforms the raw AUTH_MSG message into a structure suitable for loading into the Kafka Broker;

Step 5b: the handle_data() method transforms the raw DATA_MSG message into a format that can be processed by the Data Queue Layer;

Step 6a: the data stream authentication message - AUTH_MSG is forwarded to the Data Queue Layer;

Step 6b: the session-related messages - DATA_MSG are forwarded;

Step 7: the process() method of the Streams Microservice Layer sequentially reads the AUTH_MSG message from the specified topic;

Step 8: the parameters are extracted from the AUTH_MSG for subsequent verification.

Step 9a: the micro-caching mechanism is utilized. The Verify Streams Microservice queries the local off-chain storage to retrieve the device fingerprint (identity) that sealed the message. The query is composed of the GUID and the Seals Indices (). As an extension, a stored procedure or a trigger-like mechanism can be employed with the local off-chain storage for generating the Session Seal Key . In this case, the body query is extended with the Session Nonce parameter (), allowing for a reduction in the number of steps necessary before proceeding to Step 12. The Confidential Computing Strategy should be implemented to ensure the strict protection of data in transit.

Step 9b: the appropriate identity is returned, or an identity Not Found Error is generated. If the extension mentioned in Step 9a is applied, an alternate response of is returned.

Step 10: if the Session Seal Key - is successfully generated (or obtained), the steps related to querying the Distributed Ledger Layer (Hyperledger Fabric) are omitted, and Step 12 is executed instead.

Step 11a: otherwise, the identity Not Found Error results in a query via the Communication Layer to the Hyperledger Fabric Gateway service of the Distributed Ledger Layer.

Step 11b: the chaincode (transaction) is executed to generate based on the device GUID, a list of seal indices, and the Session Nonce .

Step 11c: the device GUID along with the Session Seal Key is returned from the ledger , or a relevant error is produced.

Step 12: entity identities are compared by verifying the extracted signature that sealed the AUTH_MSG against the signature - with the Session Seal Key returned from Step 10, Step 11c, or optionally Step 9b. If the signatures match (), the AUTH_MSG undergoing the verification process will be preserved. If they do not match, the message may either be discarded or stored in a separate queue for the identification of potentially malicious or faulty devices.

Step 13: the Streams Microservice sequentially reads and verifies the session-related messages - DATA_MSG.

Step 14: the Session Seal Key from either Step 10 or Step 11c is used, and the signatures of the DATA_MSG are compared.

Step 15: verified DATA_MSG is sent to the appropriate topic.

Step 16: an entity representing the Subscribers Layer reads the verified data streams read_streams() based on the subscribed topics and the authorization policy.

5. Framework Evaluation

Benchmarking the performance of streaming data processing systems poses a considerable challenge due to the complexities related to the global concept of time. This section provides benchmarks for our framework in two setups: the Amazon Web Services (AWS) cloud environment and the Raspberry Pi device-based environment. In the AWS environment, we measured the average times for consumers to read the data stream that was processed through microservices utilizing the Java Kafka Streams API. Our objective was to validate the applicability of our framework in the context of audiovisual streams and to assess its computational stability. Conversely, the Raspberry Pi setup focused on gathering the latency metrics of key internal operations on resource-constrained devices. Additionally, we compared the operation latencies of implementations in both Java (Kafka Streams API library) and Go (Sarama library) programming languages.

5.1. Cloud Setup

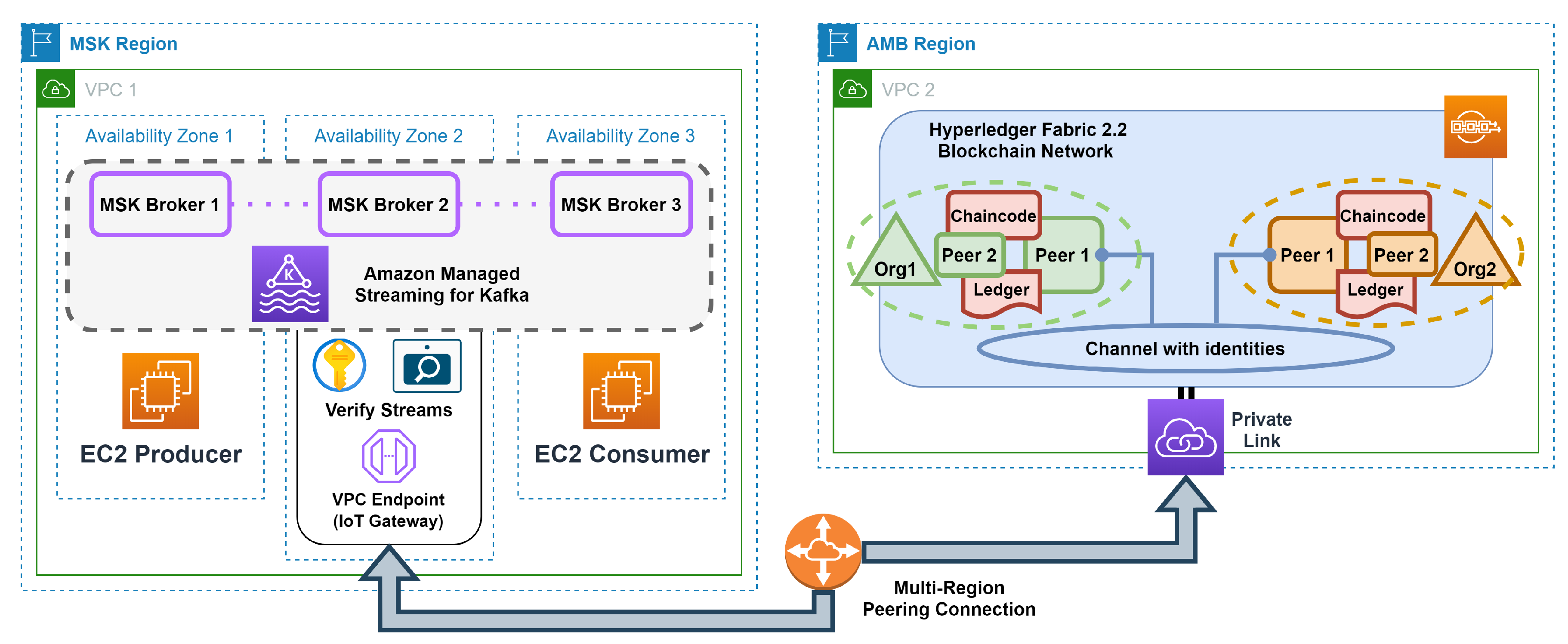

Our experiment seeks to verify our framework’s capability to process audiovisual streams in a distributed and federated cloud environment. Consequently, we deployed the Data Queue (Kafka Cluster) and Distributed Ledger in separate locations (AWS regions). To ensure durability (fault tolerance), we deployed three Kafka Brokers and established two ledger peers for each federated organization. Communication between the layers including the Streams Microservice Layer is enabled through a single AWS Private Link.

Figure 11 illustrates the various components of our experimental framework deployed using AWS technology (Setup I), comprising:

two AWS regions to simulate geographical distances: MSK Region that belongs to Org1, and AMB Region for Org1 and Org2. The Multi-Region link was set using VPC Peering Connection;

a single Amazon Managed Streaming for Apache Kafka version 2.8.1, deployed in the MSK Region isolated (availability) zones, where three kafka.t3.small brokers (vCPU: 2, Memory: 2GiB, Network Bandwidth: 5Gbps) were set. Each broker has a default configuration with a single partition and a replication factor of 3;

a single Amazon Managed Blockchain Starter Edition for Hyperledger Fabric version 2.2, deployed in the AMB Region, where a single channel for identities was created within the blockchain network. Also, each member (Org1, Org2) of the channel has two nodes (peers) running of type bc.t3.small (vCPU: 2, Memory: 2GiB, Network Bandwidth: 5Gbps);

two Amazon Elastic Compute Cloud (EC2) virtual machines of type t2.micro (vCPU: 1, Memory: 1GiB), deployed in the MSK Region in two isolated zones to simulate data stream producer and consumer;

a single EC2 instance (t2.micro) deployed in the MSK Region with a streams microservice to verify messages;

a single AWS PrivateLink interface (VPC Endpoint) that enables the communication between the microservice and elements of the Amazon Managed Blockchain Hyperledger Fabric.

The AWS cloud due to its pay-as-you-go model and pluggable architecture for the COTS services: Amazon Managed Streaming - Apache Kafka and Amazon Managed Blockchain - Hyperledger Fabric, enables efficient deployment of our framework. Simultaneously minimizing the operational costs associated with the provisioning, configuration, and maintenance of its various components. As a consequence, our framework is suitable for federated environments for which it is required to ensure zero-day interoperability.

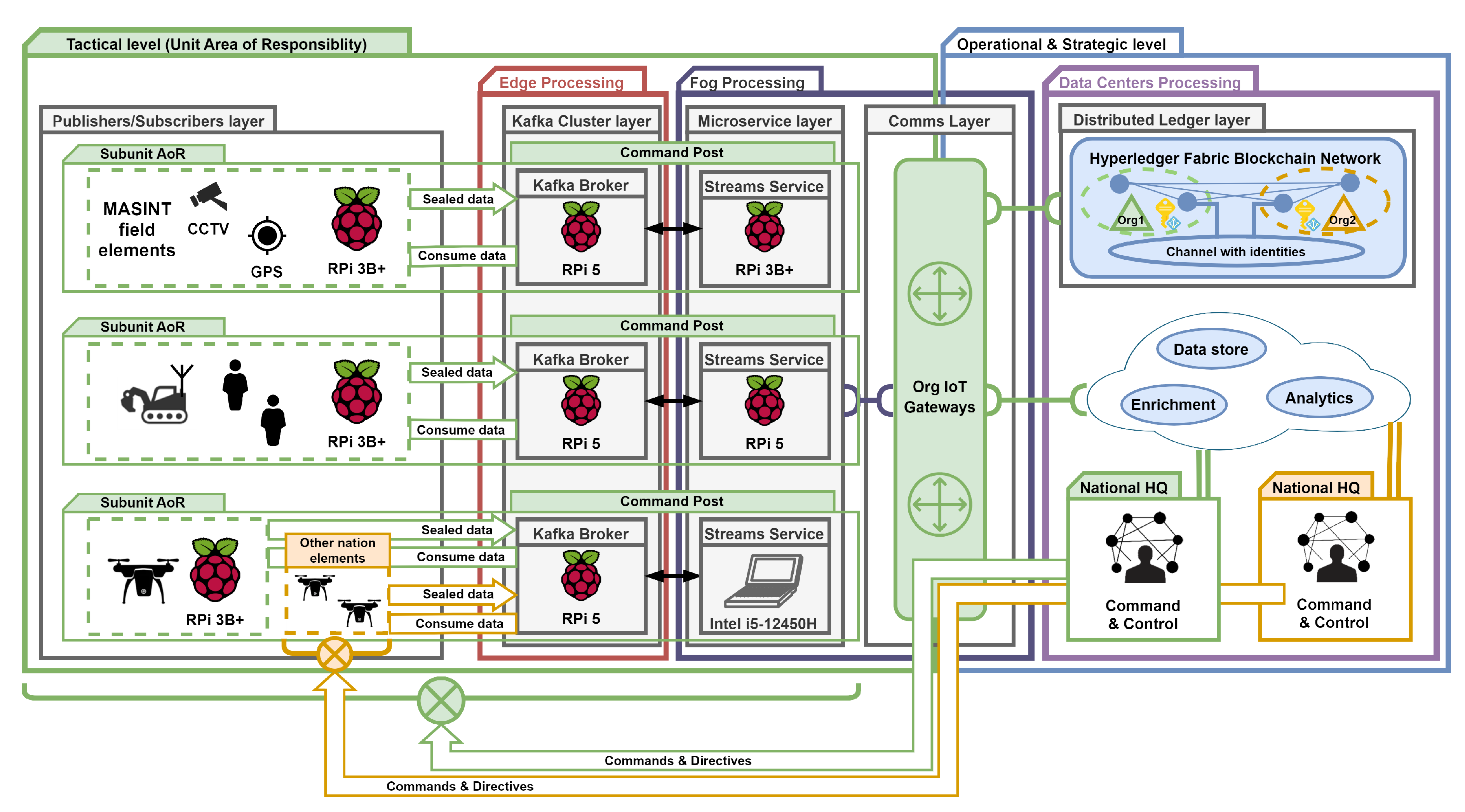

5.2. Resource-Constrained Setup

In the second benchmark (Setup II), we chose resource-constrained devices to evaluate their utilization and computational power. We positioned the specific layers of our framework within the IoT environment locations: Actuators/Sensors, Edge, Fog, Data Center (Cloud). The Kafka Cluster was deployed on the Raspberry Pi 5 (RPi5) devices in the Edge Processing component, and virtualization technology was used to manage the distributed ledger in the Data Center location. For the Streams Microservice Layer placed in Fog, we used the Raspberry Pi 3B+ (RPi3), the RPi5, and a Standalone Laptop (SLap) platforms as a reference for microservice benchmarking. The Communication Layer included a Gigabit switch and an IEEE 802.11 router. Our setup simulates infrastructure placement in tactical military networks and can be adapted for scenarios involving civil components during HADR operations.

Figure 12 represents the device-based environment, which includes:

the Apache Kafka Cluster (Data Queue Layer) based on RPi5 devices (CPU: 2.4GHz Arm Cortex A76, Memory: 8GiB). Each Kafka Broker has a default configuration with a single partition and a replication factor of 3. Moreover, each broker was deployed at the Tactical level (Unit Area of Responsiblity, AoR) within the specific Subunit Command Posts to simulate geographical distances.

the Streams Microservice Layer is an integral part of the Fog Processing component. It has been designed to work with three different devices: RPi3 (CPU: 1.4GHz Arm Cortex A53, Memory: 1GiB), RPi5 (CPU: 2.4GHz Arm Cortex A76, Memory: 8GiB), and SLap (CPU: 3.3GHz i5-12450H, Memory: 16GB).

the Hyperledger Fabric Blockchain Network is deployed on a server using virtualization technology (Data Centers Component). Within the blockchain network, a single identity channel was created. Each member (Org1, Org2) of the channel has two nodes (peers) running on virtual machines (vCPU: 2, Memory: 2GiB);

three RPi3 devices were deployed at each Subunit AoR (Tactical level) to be used as producers and consumers.

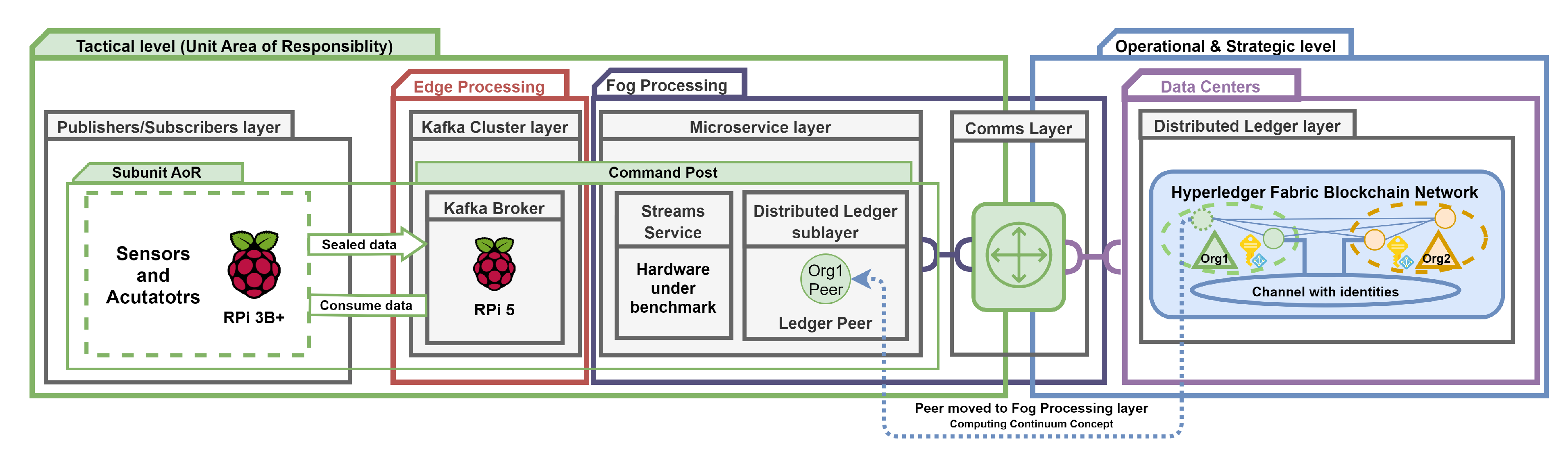

Furthermore, in

Section 3 we presented the meaning of the Computing Continuum concept. By relocating the Ledger Peer from the Data Center to the Fog location, we refined Setup II to facilitate benchmarking with the mentioned concept (

Figure 13).

The Raspberry Pi device-based environment facilitates straightforward out-of-the-box deployment of our framework while maintaining low operational costs. Moreover, the presented environment promotes the Computing Continuum concept, which can enhance the deployment of services at the tactical level in settings characterized by DIL networks, as well as in federated environments that require zero-day interoperability.

Additionally, we are considering integrating information classification approaches with the CC concept to enable the processing and sharing of relevant IOs based on their Value of Information. The versatility of Raspberry Pi devices allows for integration with a Neural Processing Unit, a specialized processor designed to accelerate artificial intelligence and machine learning tasks. This feature can facilitate parallel processing of large data volumes within the Fog component, making it especially well-suited for applications involving Contextual Dissemination through image recognition or natural language processing, as well as for Data Quality Assessment.

Moreover, the hardware of these devices is compatible with various operating systems, including Windows 10 IoT Core and Linux OS. Lastly, the general-purpose input/output (GPIO) pins provide the flexibility to experiment with a range of communication protocols such as Sigfox, LoRaWAN, NB-IoT, Zigbee, and BLE.

5.3. Processing Systems Benchmarking

In conducting performance studies (benchmarks) of streaming data processing systems, it is necessary to consider following key metrics [

32,

33]: latency, throughput, the usage of hardware-software resources (CPU, RAM), and power consumption (PC). Furthermore, the overall performance evaluation can be affected by the input parameters (e.g., system configuration) and processing scenarios (workloads) [

31]. In the context of the proposed framework, several parameters are listed below:

configuration of the Data Queue Layer: number of brokers, partitions, and data streams replication factor;

parallelization (horizontal-scaling) of stream processors (microservices);

kind (e.g., windowed aggregation) and type of operations (e.g., stateless);

number of organizations that joined a Federated IoT Environment and registered devices (identity count);

number of peers of the Distributed Ledger Layer;

selected programming language for microservices and chaincodes.

Generally, latency defines as the interval of time it takes for a system (platform) under test (SUT) to process a message, calculated from the moment the input message is read from the source until the output message is written by SUT. Hence, it is important to distinguish the latency metric [

32] into its two types:

event-time latency and

processing-time latency. The first mentioned refers to the interval between a timestamp assigned to the input message by the source and the time the SUT generates an output message. The second one refers to the interval calculated between the time when an input message is ingested (read) by the SUT, and the time the SUT generates an output message.

Data Dissemination System Benchmarking

In the context of the Apache Kafka, latency (end-to-end, E2E) is defined as the total time from when application logic produces a record using KafkaProducer.send() to when that record can be consumed by the application logic through KafkaConsumer.poll(). This E2E latency includes various intermediate operations that can affect the overall duration. The publish operation time encompasses flying time, queuing time, and internal record processing time. Flying time refers to the duration for transmitting the record to the leader broker, queuing time pertains to the time taken to add the request to the broker queue by network thread, and record processing time involves the reading of the request from the queue and the appending of logs (records). Furthermore, the replication factor and cluster load impact commit time, which is the time required for the slowest in-sync follower broker to retrieve a record from the leader. Moreover, the Catch-Up operation refers to the duration a consumer takes to read the latest record () while its offset pointer is lagging (, where ). Lastly, fetch operation time impacts Kafka consumer record read latency, as the consumer continually polls the leader broker for more data from its subscribed topic partition.

As previously noted, various factors can influence latency. In our experiments, we focused on the detailed configuration of the Kafka parameters for our microservice that operates both as a producer and a consumer during single record processing. Consequently, the following configuration was uniformly applied across all scenarios:

the produce operation was set without artificial delay, and a record will be sent immediately to the Kafka Cluster;

microservice reliability was configured to complete operations only after all in-sync replicas have received the record and sent back an acknowledgment. This setting includes both publish and commit times, which adds latency overhead to our microservice;

the replication factor of a single record was set to three and the number of replica fetcher threads per source broker was set to the default value of one;

idempotence was set. This enables the Kafka mechanism to identify and eliminate duplicate messages by comparing a unique sequence number of each record sent to a partition;

there was no separate listener for replication traffic on brokers and for client (producer/consumer) traffic;

the microservice record consumer has been configured to operate without incurring any additional latency, while ensuring that the processing guarantee is established as exactly once. Upon submission of a fetch request by microservice, a response is provided immediately when a single byte of data (record) becomes available from the Kafka Broker.

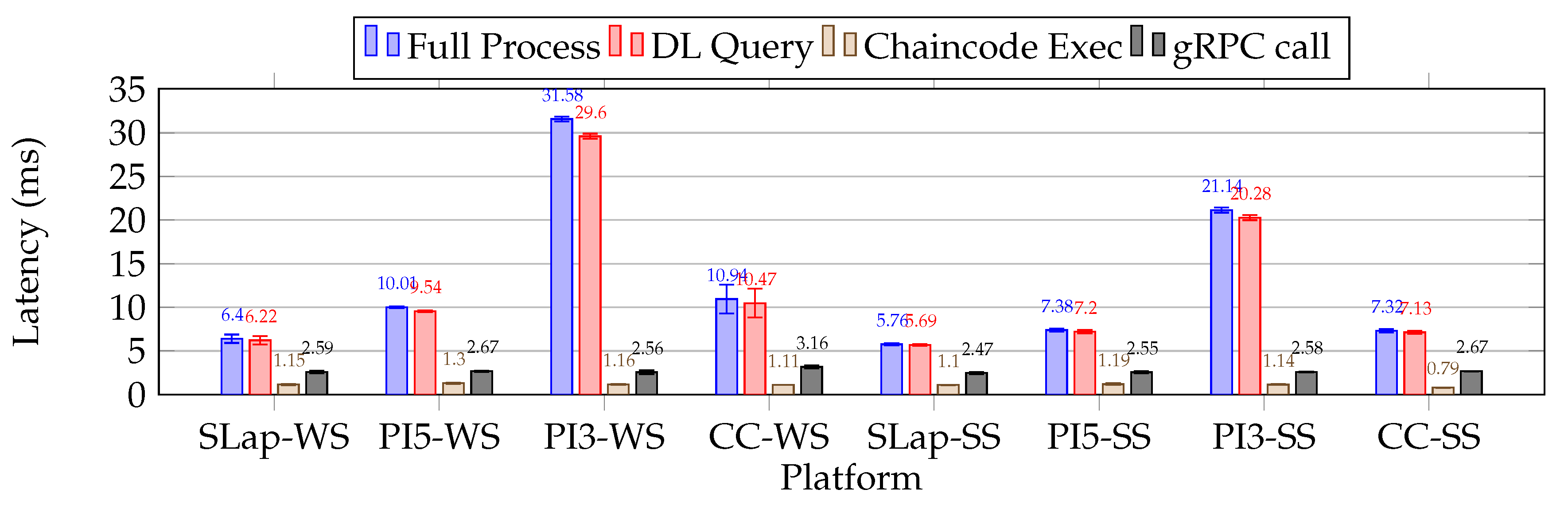

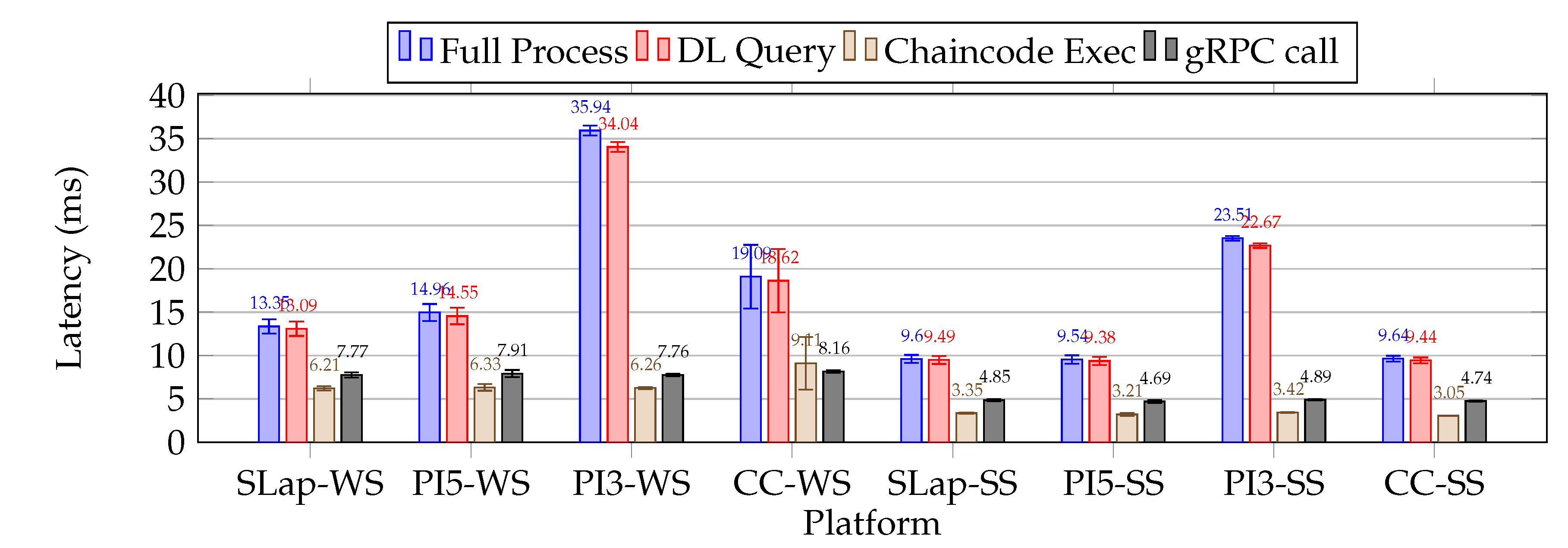

Distributed Ledger System Benchmarking

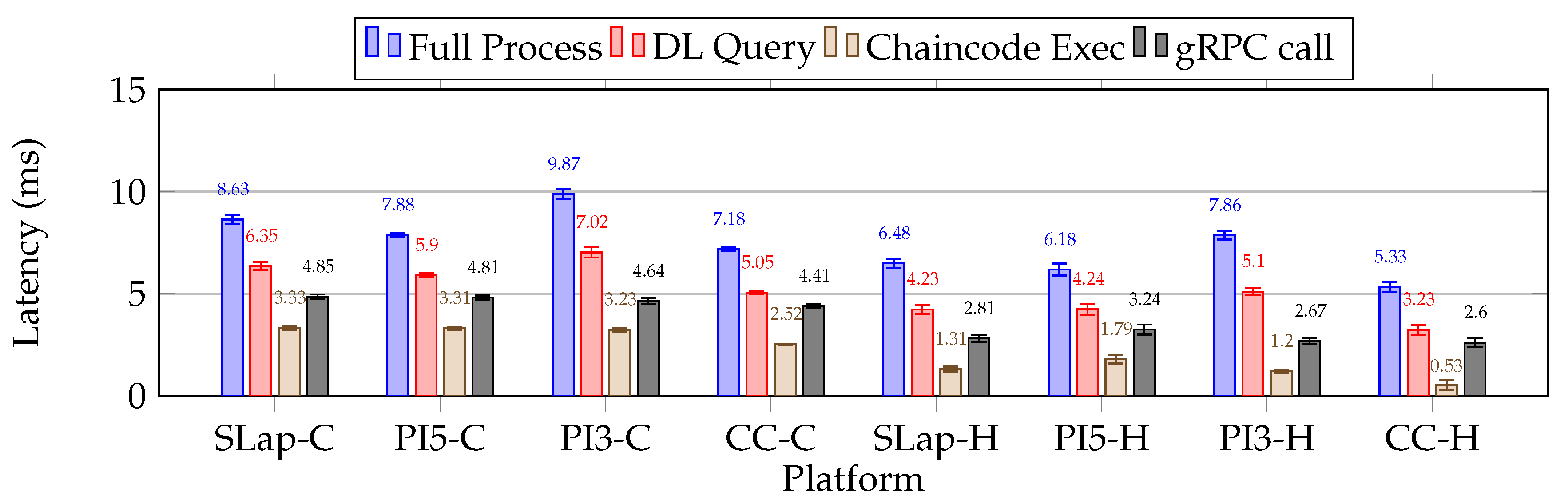

Regarding the distributed ledger operations benchmarking, we focused on collecting latency metrics from two sources: one from the microservice ledger query operation (DL Query), and another directly from the log entries of the Ledger Peer server. By analyzing the peer logs, we focused on two types of entry: the duration of gRPC call and the time required to evaluate chaincode (Chaincode Execution), specifically to acquire the device’s seal from the ledger. The first mentioned metric is essential for monitoring and performance analysis, as it offers valuable insights into the efficiency and responsiveness of the services involved in gRPC communication. Conversely, the second metric pertains to a peer node that endorses transactions, reflecting the computation burden.

In examining potential peer (database) microcaching mechanisms, we can differentiate between two phases of the Ledger Peer: the Cold Peer (CP) and the Hot Peer (HP). The CP occurs when the peer is restarted each time before the microservice is launched. Conversely, the HP refers to a state in which the peer has already been queried for all identities present in the ledger, and then the microservice under test is launched. These phases can significantly affect the performance of the chaincode latency [

35,

36]. Notably, we have selected Apache CouchDB as the primary backend database for our ledger peers. This NoSQL database employs a schema-free JSON format and a B-tree indexing system, making it ideal for complex, read-heavy queries, although it is not optimized for write operations like a Log-Structured Merge-tree. Fortunately, our framework primarily focuses on ledger read operations.

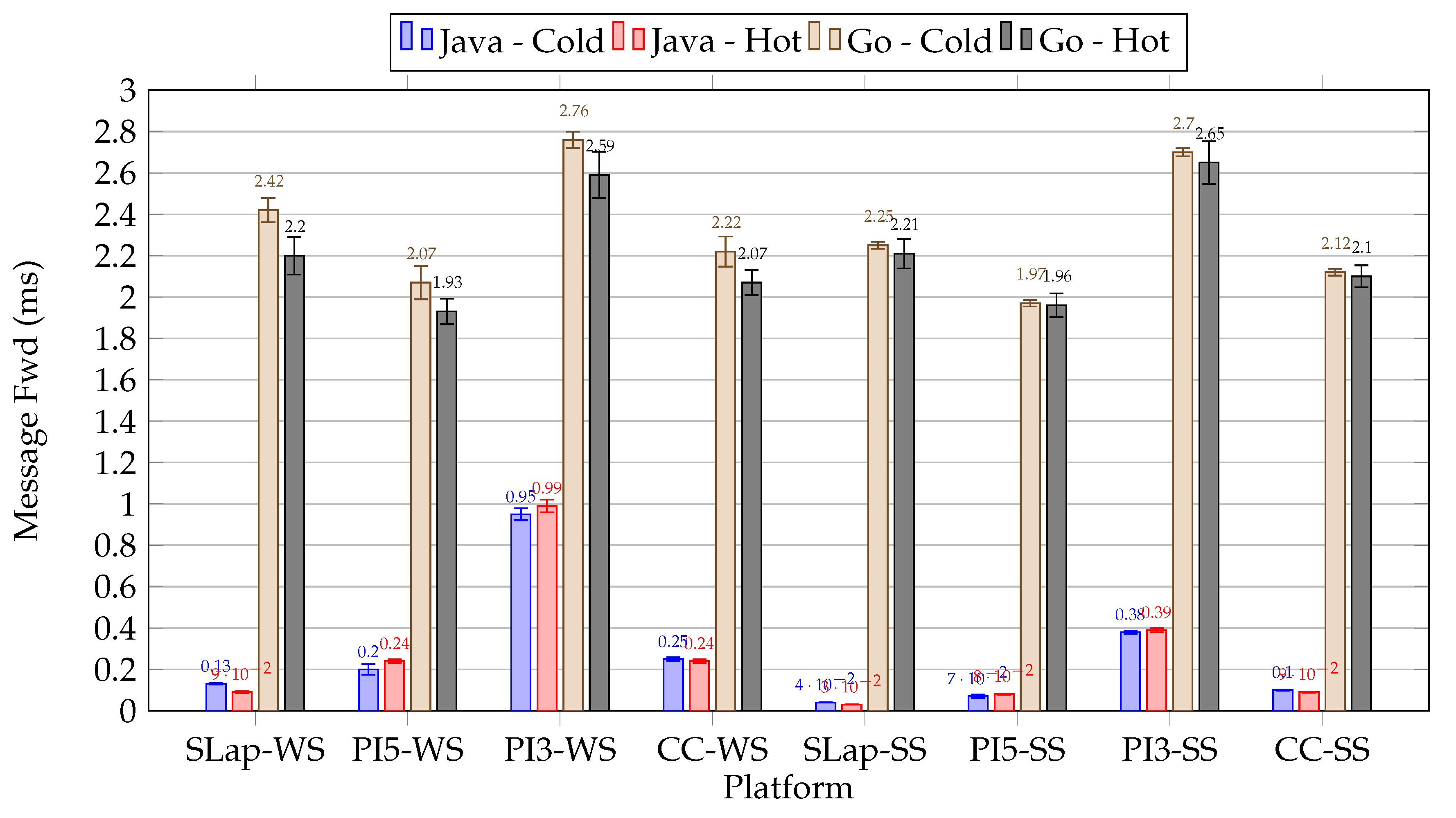

Microservice Benchmarking

In the case of the Go programming language, it is statically compiled into a machine code, resulting in a single executable that includes all necessary dependencies and can be run directly on the operating system. This approach eliminates the two-step compilation process utilized by Java, which embodies the concept of "write once, run anywhere".

At the onset of a Java microservice, the Java Virtual Machine (JVM) performs Just-In-Time (JIT) dynamic compilation, leading to fluctuations in internal operation latencies during the initial execution phase. This phase, commonly referred to as the Warm-Up State (WS), involves the JIT analyzes the bytecode (pre-compiled form) and translates it into machine code. It identifies frequently executed methods and loops, omits unused code segments, applies constant folding, and manages object allocation. Once this optimization process concludes, the microservice attains a Steady State (SS) of performance [

37].

We recognize the impact of JIT optimization on our metrics, so as a mitigation strategy during our benchmarks, we focused on capturing latencies for microservices operating in both the WS and the SS. Nevertheless, fluctuations in performance during the WS state can lead to notable latencies, especially on resource-constrained platforms.

Our implementation involves collecting the durations of key microservice operations: Cryptographic Primitives Initialization, Distributed Ledger Query, HMAC Validation, AES Decryption, and Message Forwarding. Each operation will be executed a fixed number of times based on the selected message volume. Lastly, the main method process(), which includes these operations, will be repeated multiple times using fresh JVM instances (forks). A similar approach will be employed for the Go microservice.

5.4. Resource Utilization

To effectively manage device resource utilization during benchmarks and identify potential anomalies, we employed the real-time monitoring system based on the Node Exporter service. This service allows for accumulation of an extensive range of metrics related to hardware and operating systems, such as RAM, I/O disk, and CPU usage. The collected data can be then ingested and stored in Prometheus [

38], an open-source monitoring system that implements a pull model. For in-depth analysis, we utilized Grafana, a web application that provides interactive visualizations and customizable dashboards, allowing us to derive valuable insights regarding the tested platforms.

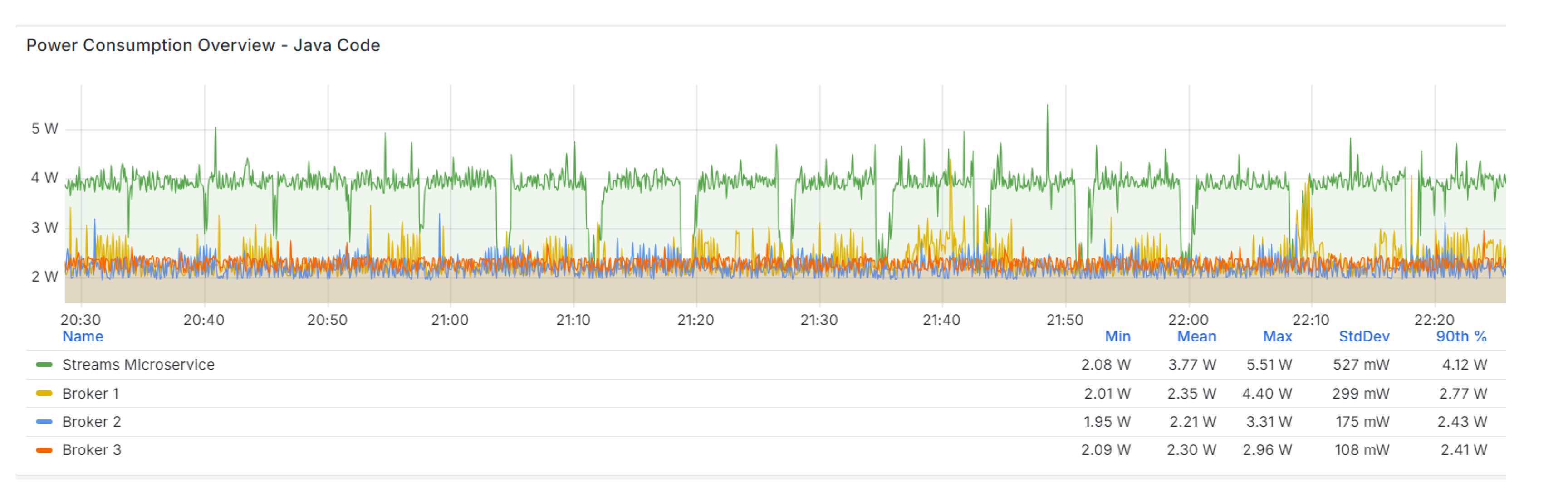

5.5. Power Consumption

During benchmarking, it is crucial to monitor potential voltage spikes that may decrease CPU instructions per clock (IPC), as these issues can adversely affect microservice execution. Moreover, maintaining a focus on power consumption (PC) facilitates the identification of high-power instructions (operations) within an actively running microservice under specific workloads, allowing for further optimization.

It is also important to detect throttle events that could result in instability and crashes of microservices. For the Raspberry Pi platforms, the risk of such events occurs when the CPU temperature, as measured by the built-in sensor, ranges from 80 to 85°C. As a result, this leads to a gradual throttling of the CPU cores, causing a reduction in their frequencies.

We recognize that PC can fluctuate, and the current draw may vary based on usage. Therefore, during the benchmarking process, we took the following preliminary steps:

devices for testing were deployed in their unmodified state, without any overclocking;

the lower limit for CPU temperature (throttle protection) has not been modified;

no additional devices were connected to the GPIO and USB ports; an SSH connection was used to control the devices.

To monitor power consumption during our tests, we employed the RPi5 Power Management Integrated Circuit (PMIC, Renesas DA9091 “Gilmour”) [

39], which integrates eight switch-mode power supplies to deliver various voltages required by the PCB components, including the Cortex-A76 CPU cores (VDD_CORE). We integrated a revision-agnostic software tool called

vcgencmd, which provides access to information about the voltage and current for each component managed by the PMIC. This tool is particularly versatile for monitoring various parameters, including the CPU core’s status, temperature, and throttle state (represented as a bit-pattern, flag: 0x40000). Additionally, we implemented the Prometheus Scraper that operates on a pull model to collect power metrics from devices under test. These metrics are then ingested into a Prometheus instance for further visualization in Grafana (

Figure 14).

5.6. Processing Scenarios

Scenarios of Setup I - Cloud-Based Environment

In this paper, we examined the processing time latency of microservices developed using the Java Kafka Streams API and deployed in the AWS cloud-based environment (Setup I). Our objective was to validate the applicability of our framework in the context of audiovisual streams and to assess its computational stability. We designed two scenarios for this purpose:

Setup I Scenario I: involved verifying the input (sealed) message by performing a comparison operation between the extracted device identity, with the identity stored in the distributed ledger.

Setup I Scenario II: involved verifying the sealed message by comparing the extracted device identity with the identity stored in the off-chain data store. In this scenario, all device identities from the ledger were synchronized and stored in the off-chain store.

In the scenarios outlined, the burst-at-startup technique was employed [

31]. This process involved generating and sealing each input message with a pseudo-random device identity in advance. Once a predetermined number of input messages had been created, a single instance of the microservice responsible for their verification was activated. Furthermore, we aimed to extend workloads utilizing varying quantities of registered identities within the distributed ledger.

Scenarios of Setup II - Resource-Constrained Environment

For the Raspberry Pi resource-constrained environment (Setup II) we benchmarked microservices developed in Java (Kafka Streams API) and the Go (Sarama) programming language. Furthermore, beyond the full processing-time, we measured the duration of microservices’ significant (time-consuming) operations: Cryptographic Primitives Initialization, Distributed Ledger Query, HMAC Validation, AES Decryption, and Message Forwarding. Moreover, we took an insightful look at hardware and software utilization through real-time monitoring of the whole Setup II. We planned to conduct bellow scenarios:

Setup II Scenario I: involved verifying the sealed message by comparing the extracted device identity with the identity stored in the distributed ledger located in the Data Center component, while also applying the burst at startup technique.

Setup II Scenario II: involved verifying the sealed message by comparing the extracted device identity with the identity stored in the Ledger Peer relocated to the Fog Processing component (the Continuum Computing concept enabled). The burst at startup technique was applied.

Setup II Scenario III: involved verifying the sealed message by comparing the extracted device identity with the identity stored in the distributed ledger within the Data Center component. Throughout this scenario, continuous writing operations were conducted to the Data Queue Layer, maintaining a consistent message throughput of 400 messages per second [

33].

5.7. Reference Points for Experiments

Processing Scenarios:

To compare the RPi3 and the RPi5 platforms we present results from Setup II Scenario I (Steady State, Hot Peer phase, 10 000 identities, 10 000 messages), derived from microservice benchmarking on the SLap platform (

Table 1 – Java,

Table 2 – Go). For consistency during further reading, the tables detailing microservice latency present averaged results with the average absolute deviation in brackets, calculated from 10 launches (forks) of the microservice. The following metrics were employed to evaluate the results:

average latency (Avg) and average absolute deviations of data points from their mean value (Avg Dev);

minimum (Min) and maximum (Max) latency;

standard deviation based on the entire population (Pop Std Dev);

quantiles of order: p90, p95, p99 (Percentiles [p=0.9; p=0.95; p=0.99]).