1. Introduction

The Pilates Method of Exercise (PME) is widely recognized as an integrative approach to physical conditioning that emphasizes muscle control, posture, and breathing [

1]. Together, these elements improve strength, flexibility, neuromuscular coordination, and overall body awareness [

2]. Originating in the early 20th century, PME was developed as a rehabilitative practice to improve physical function, but it became globally known for its application in fitness, therapy, and athletic training [

3,

4]. PME can be practiced on specialized equipment, such as the reformer or Cadillac, or even during mat exercises, offering versatility across diverse populations and settings [

5].

PME has six principles: centering, concentration, control, precision, flow, and breathing. These principles form the method foundation and provide a biomechanical and neuromuscular framework that supports functional movement patterns [

2]. Breathing is emphasized as a vital component of PME, regulating intra-abdominal pressure, stabilizing the core muscles, and enhancing mind-body awareness. The Pilates breathing technique combines diaphragmatic and costal breathing, which promotes thoracic expansion while maintaining abdominal engagement [

4]. This unique approach to breathing has been linked to improved core stability and muscle excitation, particularly in the deep stabilizing muscles, such as the transverse abdominis, lumbar multifidi, and pelvic floor [

6].

Integrating breathing and centering during PME has significant implications for muscle excitation and performance. Electromyography studies have demonstrated that Pilates-based breathing techniques can enhance neuromuscular efficiency, a parameter that reflects the relationship between neural drive and force production [

7]. Neuromuscular efficiency is particularly relevant in resistance training and rehabilitation, as it quantifies the optimization of motor unit recruitment and firing pattern [

8]. Efficient muscle function, as evidenced by reduced electromyographic amplitude during high-force tasks, indicates an adaptive neuromuscular system capable of performing tasks with minimal energetic cost [

9]. Additionally, the principles of resistance training underscore the importance of gradually increasing mechanical load to stimulate neuromuscular adaptations, this concept aligns with the objectives of Pilates training, which often incorporates progressive resistance using springs or body weight [

10].

Research on neuromuscular efficiency during concentric and eccentric muscle actions reveals distinct patterns. Eccentric exercises demonstrate significantly lower muscle excitation compared to concentric[

11]. Recent investigations have explored the influence of Pilates breathing on specific muscle groups, particularly in the context of upper limb movement [

12]. Research on the biceps brachii during phases concentric and eccentric revealed more significant electromyographic activity when Pilates breathing associated with centralization was employed compared to regular breathing techniques. These findings suggest that the coordinated excitation of respiratory and core muscles can enhance the excitability and performance of distal muscles [

6]. However, there is a lack of studies isolating the effects of Pilates breathing on neuromuscular efficiency or examining its impact across different load intensities for a given exercise.

Despite growing interest in the biomechanical and neuromuscular effects of PME, many aspects of its mechanisms remain underexplored. Specifically, the isolated contribution of Pilates breathing in tasks requiring upper limb coordination. Furthermore, the interaction between load and breathing techniques in eliciting neuromuscular responses warrants further investigation. Therefore, the present study aims to analyze the effects of Pilates breathing on the neuromuscular efficiency during concentric and eccentric phases of the biceps brachii at varying load levels. By comparing Pilates breathing with regular breathing, this research seeks to elucidate the role of breathing techniques on neuromuscular efficiency. These findings can potentially inform evidence-based practices in rehabilitation, strength training, and performance enhancement.

2. Materials and Methods

Fifty-eight healthy adults from both sexes (18-30 years) joined the present study. The participants were recruited by personal contacts and public invitation through folders from Dec/2023 to Feb/2024. The participants’ characteristics are shown in

Table 1 . The a priori two-tailed sample size calculation was based on a previous study, considering the effect size of 0.48, the alpha level of 5%, and a 95% power, returning 32 participants.

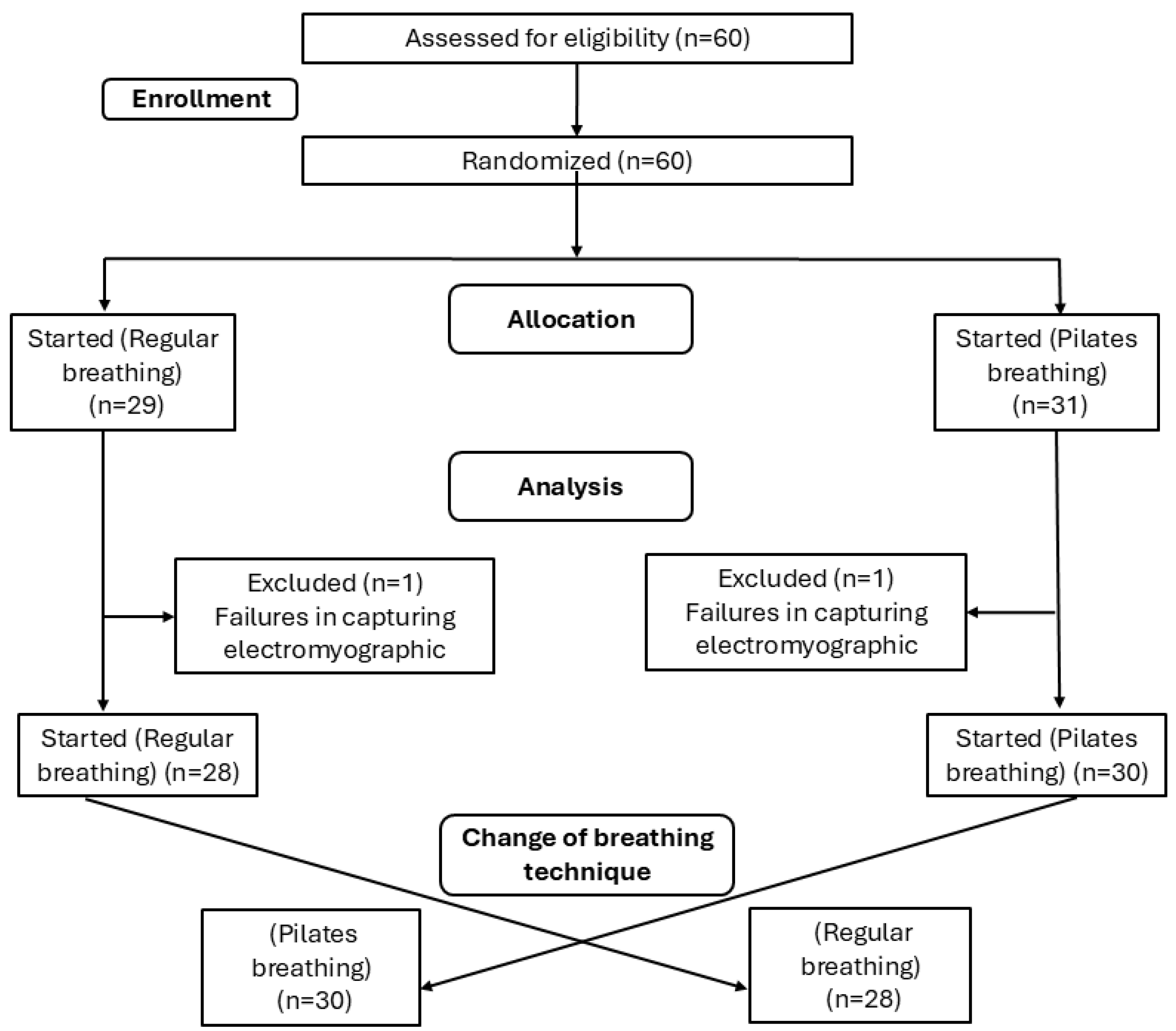

Considering a sample loss of 30%, 44 participants would be needed to reach the sampling power. However, 60 participants were selected, and fifty-eight data were analyzed, as shown in

Figure 1. The inclusion criteria were to be between 18 and 30 years old, never have practiced the PME. As exclusion criteria, the participants should not have a history of severe orthopedic and neurological disorders, cardiovascular disease, and upper limb surgery. This randomized clinical trial was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. The Ethics Committee of the Federal University of Juiz de Fora (number 66768023.1.0000.5147) approved all the procedures employed in the present study. The trial was registered in the Brazilian clinical trials registry (RBR-5q5g4s6). All participants gave their written informed consent prior to participation.

2.1. Data Recording

Muscle excitation was measured using a biological signal acquisition module with eight analogue channels (Miotec

TM Biomedical Equipment, Porto Alegre, RS, Brazil). An A/D board converted analog to digital signals with a 16-bit resolution input range, sampling frequency of 2 kHz, common rejection module greater than 100 dB, signal/noise ratio less than 03 μV RMS, and impedance of 109 Ω. The signals are electromyographic (EMG) were recorded by root mean square (RMS) in μV and the average frequency in Hz with surface electrodes (20-mm diameter and a center-to-center distance of 20 mm). Prior to fixation of the electrodes, trichotomy was performed, and the skin was cleaned with 70% alcohol. The muscles analyzed by sEMG were as follows: right and left arm long head of biceps brachii. Auto-adhesive surface electrodes were attached on the muscle bellies and positioned parallel to the muscle fibers using the techniques described by the sEMG for the Non-Invasive Assessment of Muscles (SENIAM) recommendations. A reference electrode was placed on the left lateral epicondyle. The sEMG signals were amplified and filtered (10-500 Hz, notch 60 Hz) [

13].

2.2. Exercise Procedures

To establish the maximal isometric output (100%), each participant performed 3 maximal voluntary isometric contractions (MVIC) of elbow flexion (the participant standing with knee flexed at 20° and elbow flexed at 90°), measured by a laboratory-grade load cell (MiotecTM Biomedical Equipment, Porto Alegre, RS, Brazil; maximum tension-compression = 200 kgf, the precision of 0.1 kgf, the maximum error of measurement = 0.33%) attached to an acquisition module with eight analogs channels (MiotoolTM, MiotecTM Biomedical Equipment, Porto Alegre, RS, Brazil). According to the manufacturer’s recommendations, the laboratory-grade load cell was previously calibrated using 10% (20 kg) of its maximal tension compression. Both limbs were simultaneously assessed. The laboratory-grade load cell was anchored to a stable surface, and participants were instructed to exert maximum effort during the isometric test. The maximal force output data were obtained from the average of the three MVIC.

2.3. Experimental Protocol

After 5 minutes of rest, the participant was then instructed to perform 18 trials (9 for regular and 9 for Pilates breathing) of a complete entire dynamic movement (concentric-eccentric) of the elbow combined with a breathing technique at 3x 20%, 3x 40%, and 3x 60% of the flexion MVIC. All participants performed both breathing techniques (Pilates breathing and regular breathing), and the order of the breathing technique was randomized. The randomization sequence was independently generated using the

http://www.randomizer.org. The participant who started by performing the regular breathing, performed the Pilates breathing later, and vice versa. The order of the loads (20%, 40% and 60% of the flexion MVIC) was also randomized for each participant using the above-mentioned website. One minute of rest between each load adjustment was allowed.

The regular breathing was performed with a concentric contraction during inspiration and an eccentric contraction during expiration. The Pilates breathing consisted of an initial deep inspiratory phase, then moving the elbow through flexion during an expiratory phase, another deep inspiration, and the final eccentric extension during the final expiratory phase. Thus, the elbow was moved only during the expiratory phase. To control the execution timing, all participants performed a familiarization before the task, demonstrating and teaching the participants how to perform the exercise along with each breathing technique. The concentric and eccentric timing phases were set for both breathing exercises at 2 seconds each, controlled by the rater.

2.4. Data Extraction

All sEMG data were normalized using the MVIC, and the mean muscle activities during concentric and eccentric phases of the biceps brachii muscles were calculated. All information was recorded and processed offline using the MIOTEC Suite™ software (MIOTEC™; Biomedical Equipment). To set the elbow movement onset, the concentric-eccentric phase switch, and the end of the elbow movement, all movements were recorded using a camera synchronized to the sEMG acquisition. Markers were digitally set for each event (onset, switch, and end). Next, the concentric and eccentric biceps brachii electromyographic signals were windowed following the established video markers.

The neuromuscular efficiency index was determined by calculating the ratio between the mean of sEMG activity normalized by MVIC and the corresponding percentage force (20%, 40%, and 60% of MVIC). This variable was expressed as (%sEMG/kgf). In this context, a lower ratio value indicates greater neuromuscular efficiency, meaning the muscle can generate the required force with less electrical activity, reflecting a more optimized neuromuscular performance.[

9]

2.5. Data Analysis

Descriptive analysis was performed (median, minimal, maximal). Normality and homogeneity were assessed using the Shapiro-Wilk and Levene’s tests, respectively. The non-parametric Friedman’s repeated measures analysis of variance was used, followed by the Durbin-Conover post hoc test for pairwise contrasts, avoiding multiple comparisons. Effect sizes (ES) were calculated using the Cohen’s d test. The ES were qualitatively classified as: very small (0.01 to 0.19); small (0.20 to 0.49); moderate (0.50 to 0.79); large (0.8 to 1.19) very large (1.2 to1.99); and huge (>2)[

14] .Significance was set at p<0.05. All statistical analysis was done using the freeware JAMOVI (The JAMOVI Project, version 1.6.15, retrieved from:

http://www.jamovi.org).

3. Results

Sixty participants were assessed, but data from two participants were excluded due to failure capturing the electromyographic activity. Thus, fifty-eight participants were analyzed. Participants’ characteristics are shown in

Table 1. The comparison between the neuromuscular efficiency index obtained during the execution of the exercise using regular breathing or Pilates breathing at different load levels is presented in

Table 2. The data showed that the neuromuscular efficiency index was lower during Pilates breathing compared to regular breathing all parameters showed significant differences. Higher loads (40% and 60% of MVIC) showed the best neuromuscular efficiency responses. The ES ranged from very small to large for in the comparisons. The analyses also showed that the dominant biceps of all participants presented a better efficiency index when compared to the non-dominant side. The ES ranged from very small to moderate for in the comparisons.

4. Discussion

The present study compared the neuromuscular efficiency index during concentric and eccentric phases of the biceps brachii action associated with regular breathing and Pilates breathing at varying load levels. The results showed that the neuromuscular efficiency index was lower when movement was associated with Pilates breathing than when it was associated with regular breathing. The comparison between these two breathing techniques showed that Pilates breathing resulted in the best neuromuscular efficiency of biceps brachii during concentric and eccentric phases. According to previous studies, this finding can be explained by the best neuromuscular efficiency induced by Pilates breathing, which means that fewer motor units are required to produce the same level of force. Neuromuscular efficiency is calculated considering the amount of neural stimulation and muscle capacity to generate force. Therefore, a muscle that is able to generate greater torque with lower muscle fiber excitation is considered more efficient [

15,

16].

A study carried out with 10 healthy women proposed by [

17] excitation comparing biceps brachii with breathing techniques of with centralization technique showed an increase in biceps brachii motor unit recruitment, suggesting that there is greater muscle excitation when exercise is associated with centralization and breathing techniques of Pilates method. During this study, the centering technique was associated with Pilates breathing while the participants performed a biceps brachii isometric contraction during elbow flexion movement. The present study did not associate Pilates breathing with the centralization technique. In addition, participants performed biceps brachii isotonic contraction at the same time as the breathing technique. Therefore, differences between the present results and results reposted by [

17]can be explained by differences in properties of different muscle contraction types and concurrent neural influences, once in a previous study, participants needed to focus their attention on two simultaneous techniques when performing the biceps brachii contraction (breathing and centralization technique).

Another study evaluated the effects of centralization technique and Pilates breathing on lower limb muscle activity during squats [

18]. In this study, thirteen adults with some experience in Pilates method performed three 60° squats under three experimental conditions: (I) normal breathing, (II) abdominal contraction with normal breathing, and (III) abdominal contraction with Pilates breathing. The results showed that squats with abdominal contraction associated with Pilates breathing increased sEMG of rectus femoris, biceps femoris and tibialis anterior muscles during the flexion phase, increasing movement stability. These findings differ from those presented here, which showed less muscle excitation when performing isotonic contractions at varying load levels. The better neuromuscular efficiency indices observed in the present study when muscle contraction was associated with Pilates breathing may reflect greater neuromuscular efficiency, once, despite lower electrical excitation, muscles were able to perform the proposed exercise with the same load levels. These findings suggest that Pilates breathing leads to more efficient recruitment of motor units, allowing force generation and joint stabilization with less neural effort, resulting in more significant energy savings during exercise.

The results of the present study are similar to those presented by [

19] which included 15 women who practiced Pilates and 15 women who do not. Participants’ right and left multifidus muscles were evaluated with electromyography to estimate neuromuscular efficiency. The results related that although no difference in sEMG was observed between groups, higher values of peak isometric torque and neuromuscular efficiency was observed in Pilates practitioners, suggesting that Pilates breathing practice are effective in training spinal muscles and improved neuromuscular efficiency in women.

A physiological hypothesis that justifies these results is that Pilates breathing increases volume and oxygenation levels and can be used to support any exercise program to provide a physiological environment susceptible to better muscle recruitment; this is supported by our findings and results previously reported [

6,

18,

20]. The principle of Pilates breathing is that the individual controls breathing by performing specific force movements only during expiration, making it slower and more profound; these actions can lead to cardiometabolic and sympathetic flow changes dependent on breathing patterns [

21].

A study with 27 participants aged between 20 and 27 years [

22] which compared lower limbs neuromuscular responses to postural disturbances during spontaneous and slow breathing, showed that slow breathing shortened the latency of sEMG in lower limbs muscles during postural disturbances when compared to spontaneous breathing, Thus, slow breathing decreases sympathetic nervous system activity, redistributes blood circulation to the working muscles, and affects the metabolism of skeletal muscle cells and membranes, which can have a direct impact on skeletal muscle performance such as contraction velocity and strength. Thus, deep and slow breathing techniques can impact muscle performance.

The present study results also showed that the right biceps brachii has the best neuromuscular efficiency index compared to the left biceps brachii during the concentric and eccentric phase. These results can be explained by studies in the literature, which indicate that the dominant side presents greater efficiency in motor tasks due to neuromuscular factors and biomechanical adaptations [

23]. Lateral dominance results from greater motor representation and control in the cerebral hemisphere contralateral to the dominant limb, which results in a more refined control of movements, greater precision and muscle strength. Additionally, dominant limb often experiences greater exposure to everyday activities, leading to a greater coordination and motor skill development over time [

24].

5. Conclusions

The present study demonstrated that Pilates breathing significantly enhances neuromuscular efficiency during concentric and eccentric phases of the biceps brachii compared to regular breathing, particularly at higher load levels (40% and 60% of MVIC). The lower electromyographic activity observed during Pilates breathing suggests better motor unit recruitment and task optimization. These findings highlight the potential of Pilates breathing to optimize muscle performance, reduce neural effort, and improve functional movement efficiency. Future research should explore Pilates breathing applications in rehabilitation and athletic training, particularly in tasks requiring upper limb coordination and stability.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization: D.B.C., A.C.B., M.C.G.S.M; Methodology: D.B.C., A.C.B., K.R.R.F; Software: A.F.E., G.L.G; Validation: K.R.R.F., A.C.L., A.F.E; Formal Analysis: D.B.C., M.C.G.S.M., A.C.B; Investigation: D.B.C., K.R.R.F., A.C.L., G.L.G; Resources: A.C.B., M.C.G.S.M; Data Curation: K.R.R.F., A.F.E., G.L.G; Writing – Original Draft Preparation: D.B.C., M.C.G.S.M; Writing – Review & Editing: A.C.B., K.R.R.F., A.C.L; Visualization: A.F.E., G.L.G; Supervision: A.C.B; Project Administration: D.B.C., A.C.B; Funding Acquisition: A.C.B.. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This study was supported, in part, by the Coordenação de Aperfeiçoamento de Pessoal de Nível Superior—Brasil (CAPES)—Finance Code 001 and by the Fundação de Amparo à Pesquisa de Minas Gerais (FAPEMIG)—number APQ 02040/18. This research was funded by the Federal University of Juiz de Fora.

Institutional Review Board Statement

This randomized clinical trial was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. The Ethics Committee of the Federal University of Juiz de Fora (number 66768023.1.0000.5147) approved all the procedures employed in the present study. The trial was registered in the Brazilian clinical trials registry (number RBR-5q5g4s6).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in this study.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are openly available in Mendeley Data at [

25].

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| PME |

Pilates Method of Exercise |

| MVIC |

maximal voluntary isometric contractions |

| sEMG |

Electromyographic surface |

References

- Campos, J.L.; Vancini, R.L.; Rodrigues Zanoni, G.; Barbosa De Lira, C.A.; Santos Andrade, M.; Jacon Sarro, K. Effects of Mat Pilates Training and Habitual Physical Activity on Thoracoabdominal Expansion during Quiet and Vital Capacity Breathing in Healthy Women. J Sports Med Phys Fitness 2018, 59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pereira, M.J.; Mendes, R.; Mendes, R.S.; Martins, F.; Gomes, R.; Gama, J.; Dias, G.; Castro, M.A. Benefits of Pilates in the Elderly Population: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. EJIHPE 2022, 12, 236–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pereira, M.J.; André, A.; Monteiro, M.; Castro, M.A.; Mendes, R.; Martins, F.; Gomes, R.; Vaz, V.; Dias, G. Methodology and Experimental Protocol for Studying Learning and Motor Control in Neuromuscular Structures in Pilates. Healthcare 2024, 12, 229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pucci, G.C.M.F.; Neves, E.B.; Saavedra, F.J.F. EFFECT OF PILATES METHOD ON PHYSICAL FITNESS RELATED TO HEALTH IN THE ELDERLY: A SYSTEMATIC REVIEW. Rev Bras Med Esporte 2019, 25, 76–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byrnes, K.; Wu, P.-J.; Whillier, S. Is Pilates an Effective Rehabilitation Tool? A Systematic Review. Journal of Bodywork and Movement Therapies 2018, 22, 192–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbosa, A.W.C.; Guedes, C.A.; Bonifácio, D.N.; De Fátima Silva, A.; Martins, F.L.M.; Almeida Barbosa, M.C.S. The Pilates Breathing Technique Increases the Electromyographic Amplitude Level of the Deep Abdominal Muscles in Untrained People. Journal of Bodywork and Movement Therapies 2015, 19, 57–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Luca, C.J.; Contessa, P. Biomechanical Benefits of the Onion-Skin Motor Unit Control Scheme. Journal of Biomechanics 2015, 48, 195–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hughes, D.C.; Ellefsen, S.; Baar, K. Adaptations to Endurance and Strength Training. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Med 2018, 8, a029769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campos, D.B.; Ferreira, I.C.; Souza, M.A.; Amorim, M.; Intelangelo, L.; Silveira-Nunes, G.; Barbosa, A.C. Acceleration Profiles and the Isoinertial Squatting Exercise: Is There a Direct Effect on Concentric–Eccentric Force, Power, and Neuromuscular Efficiency? Journal of Sport Rehabilitation 2021, 30, 646–652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panhan, A.C.; Gonçalves, M.; Cardozo, A.C. Electromyographic Activation and Co-Contraction of the Thigh Muscles During Pilates Exercises on the Wunda Chair. Journal of Chiropractic Medicine 2023, 22, 322–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cardoso, E.A.; Neto, F.R.; Martins, W.R.; Bottaro, M.; Carregaro, R.L. Neuromuscular Efficiency of the Knee Joint Muscles in the Early-Phase of Strength Training: Effects of Antagonist’s Muscles Pre-Activation. Motricidade 2018, 24-32. [CrossRef]

- Alvarenga, G.M.D.; Charkovski, S.A.; Santos, L.K.D.; Silva, M.A.B.D.; Tomaz, G.O.; Gamba, H.R. The Influence of Inspiratory Muscle Training Combined with the Pilates Method on Lung Function in Elderly Women: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Clinics 2018, 73, e356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hermens, H.J.; Freriks, B.; Disselhorst-Klug, C.; Rau, G. Development of Recommendations for SEMG Sensors and Sensor Placement Procedures. Journal of Electromyography and Kinesiology 2000, 10, 361–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sawilowsky, S.S. New Effect Size Rules of Thumb. J. Mod. App. Stat. Meth. 2009, 8, 597–599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magalhães, I.; Bottaro, M.; Mezzarane, R.A.; Neto, F.R.; Rodrigues, B.A.; Ferreira-Júnior, J.B.; Carregaro, R.L. Kinesiotaping Enhances the Rate of Force Development but Not the Neuromuscular Efficiency of Physically Active Young Men. Journal of Electromyography and Kinesiology 2016, 28, 123–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Silva, Y.; Melo, M.; Gomes, L.; Bonezi, A.; Loss, J. Análise da resistência externa e da atividade eletromiográfica do movimento de extensão de quadril realizado segundo o método Pilates. Rev. bras. fisioter. 2009, 13, 82–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carvalho Barbosa, A.W.; Martins, F.L.M.; Vitorino, D.F.D.M.; Almeida Barbosa, M.C.S. Immediate Electromyographic Changes of the Biceps Brachii and Upper Rectus Abdominis Muscles Due to the Pilates Centring Technique. Journal of Bodywork and Movement Therapies 2013, 17, 385–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbosa, A.C.; Martins, F.M.; Silva, A.F.; Coelho, A.C.; Intelangelo, L.; Vieira, E.R. Activity of Lower Limb Muscles During Squat With and Without Abdominal Drawing-in and Pilates Breathing. Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research 2017, 31, 3018–3023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panhan, A.C.; Gonçalves, M.; Eltz, G.D.; Villalba, M.M.; Cardozo, A.C.; Bérzin, F. Neuromuscular Efficiency of the Multifidus Muscle in Pilates Practitioners and Non-Practitioners. Complementary Therapies in Medicine 2018, 40, 61–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marques, N.R.; Morcelli, M.H.; Hallal, C.Z.; Gonçalves, M. EMG Activity of Trunk Stabilizer Muscles during Centering Principle of Pilates Method. Journal of Bodywork and Movement Therapies 2013, 17, 185–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siedlecki, P.; Ivanova, T.D.; Shoemaker, J.K.; Garland, S.J. The Effects of Slow Breathing on Postural Muscles during Standing Perturbations in Young Adults. Exp Brain Res 2022, 240, 2623–2631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Russo, M.A.; Santarelli, D.M.; O’Rourke, D. The Physiological Effects of Slow Breathing in the Healthy Human. Breathe 2017, 13, 298–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Virgile, A.; Bishop, C. A Narrative Review of Limb Dominance: Task Specificity and the Importance of Fitness Testing. Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research 2021, 35, 846–858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schaffer, J.E.; Sainburg, R.L. Interlimb Differences in Coordination of Unsupported Reaching Movements. Neuroscience 2017, 350, 54–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- 2025; V1. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).