1. Introduction

Orthopedic medical education is rapidly advancing in the era of artificial intelligence (AI) and mixed realities (MR), transforming traditional, classroom-based education and leading to improved learning outcomes. AI algorithms provide individualized learning trajectories by using student performance data to create customized learning experiences that close the gaps in student knowledge and learning styles. [

1] This individualized approach has greatly enhanced the efficiency of orthopedic educational experiences. New advanced virtual reality (VR) platforms like the Microsoft HoloLens, Apple Vision Pro and HTC Vive Pro have demonstrated significant positive influence on increased procedural confidence and skill development in orthopedic residents. [

2] In fact, one study found that 67.28% of participants agreed that VR training improved resident confidence with procedural skills [

2].

Beyond training, new orthopedic imaging interpretation using AI diagnostic systems are rapidly evolving, with new radiology graduates reaching diagnostic accuracy levels equal to someone with decades of training. Fully involved ML models have also been developed to predict surgical outcomes and reduce complications, assisting residents in decision-making and patient risk stratification. AI has also been shown to improve the residency training experience by guaranteeing residents receive balanced exposure to procedures and adapting the curriculum through performance analytics. In this regard, these tools are advancing educational methodologies and facilitating the technological expertise of orthopedic surgeons [

2].

Compelling statistics further substantiate the argument for the positive impact of AI and MR on orthopedic education and surgical performance. In a study on percutaneous transforaminal endoscopic discectomy (PTED) training, students using MR-assisted learning demonstrated a 33.4% increase in accuracy (from 53.3% to 86.7%) compared to only a 6.7% improvement (from 60.0% to 66.7%) in those using traditional methods [

3]. A randomized clinical trial found that orthopedic residents trained with immersive VR completed reverse shoulder arthroplasty procedures 47.4 minutes faster than their traditionally trained counterparts, achieving a transfer effectiveness ratio of 0.79 [

3]. Similarly, VR-based training for tibial intramedullary nail procedures led to fewer incorrect steps (3.1–3.2 out of 16) compared to those using only a technique guide (5.7 out of 16), while VR-trained participants demonstrated significantly higher procedure completion rates (75–78%) versus 25% for those relying solely on a technique guide [

3]. Across multiple trials, VR-trained groups completed procedures 12% faster on average, showed a 19.9% improvement in overall performance, and exhibited a reduced learning curve, particularly in unicompartmental knee arthroplasty. Furthermore, trainee satisfaction remains high, with over 70% of participants reporting VR learning as at least “helpful” or “useful” in their training [

3].

These results highlight the changing impact of AI and mixed reality (MR) technologies in orthopedic education, including enhanced learning opportunities, increased accuracy of surgical procedures, and increased efficiency in performing procedures. As research and development continues, these technologies will have an important part in the advancement of the next generation of orthopedic surgeons and their preparation for practicing in a technology-enhanced period in medicine [

4].

However, challenges remain in the adoption of AI and MR technology in orthopedic education. Cost, practicality, and the need to modify the curriculum often present significant challenges. AI also raises ethical issues related to data privacy and external ethical issues about algorithmic bias when determining how to leverage AI in orthopedic education [

2]. While these technologies show great potential, their full incorporation into orthopedic education necessitates continued research, development, and equitable access across institutions [

5].

2. AI-Driven Technologies in Orthopedic Education

2.1. Microsoft HoloLens

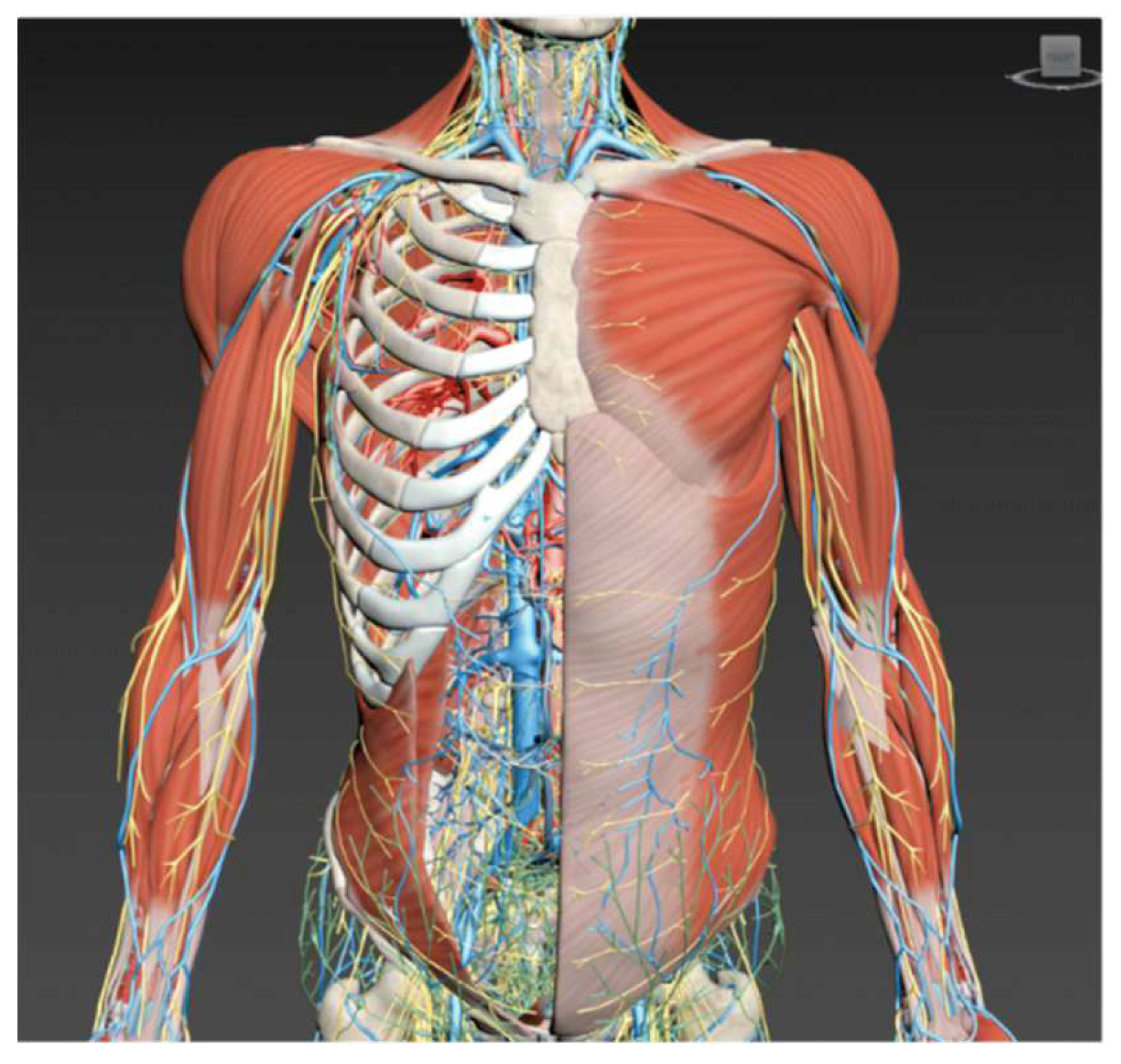

The Microsoft HoloLens (

Figure 1), a mixed reality (MR) platform, has already led to change in medical education and surgical practice by projecting interactive 3D holographs into the real-world. The applications to anatomical education have been especially impressive, allowing students to interact with anatomical structures in new ways without needing to use cadavers. While not unique to the HoloLens, the capability to engage one another with anatomical models in 3D is a new pedagogical method of instruction that holds immense potential to advance interactivity, immersive learning and retain information when it comes to the complexities of anatomy, as students can view the complexities of anatomy in three-dimensions [

6].

Research has indicated the HoloLens’s efficacy in teaching musculoskeletal anatomy and ear anatomy, showing that students who learned through mixed-reality (MR) demonstrated comparable or improved performance compared with students that learned through traditionally delivered education. In a learning study focused on ear anatomy, all groups demonstrated statistically significant test score improvement (p < 0.001) with the HoloLens-based anatomy instruction receiving statistically higher satisfaction ratings than traditional anatomy education (p < 0.001) [

6,

7,

22]. A randomized-controlled trial of musculoskeletal anatomy also showed no statistical significance in test scores between students learning through MR or through cadaveric dissection (p > 0.05) [

7], supporting MR as an alternative or supplemental education tool. Finally, a strong positive correlation was detected between mixed-reality training and scores on cadaver examinations (r = 0.74, p < 0.01), which suggests that MR-based education is capable of influencing anatomical understanding in an educational context that translates well to traditional assessments [

23]. Students reported higher quality engagement and visualization experiences while learning in an MR environment as an interactive pedagogical tool [

7,

22,

23,

24,

25].

The HoloLens offers further documentation of anatomical training that goes beyond just anatomy education, specifically applicable for clinical and surgical procedures (

Figure 2). The use of preoperative planning has enabled surgeons to engage with patient-specific anatomical structures in a three-dimensional environment, improving accuracy and decision-making. For example, preoperative planning has introduced capabilities to plan joint replacements, upper arm fractures, and trauma surgery with patient-specific three-dimensional models generated from CT imaging displayed in the environment as an overlay [

6]. In spine surgery, the HoloLens allows for visualization of pre-planned screw routes on top of holographic overlays during procedures, further increasing accuracy (

Figure 3). The HoloLens also introduces opportunities for collaborative learning in this space. Remote subject matter experts can lead the procedure by sharing the same holographic view of the procedure at a distance from the intern/ fellow [

8].

One major benefit of the HoloLens for anatomy education is the potential it creates to develop standardized training modules on a global scale for students and residents. Traditional anatomical education relies on cadaver availability—an availability that varies greatly from institution to institution and region to region. A medical school or training center can use MR technology to provide consistent, repeatable learning experiences to all students, irrespective of the anatomical education they receive on-site. The HoloLens also supports remote learning by allowing multiple users to interact with the same holographic model in real-time, thus providing an effective medium for distance education and supervised education by experts in a subject area [

7]. Despite these benefits and advantages of the HoloLens, challenges remain which need further optimization. The narrow field of view on the HoloLens also reduces immersion compared to its competitors, requiring students to adjust their perspective frequently. Some studies have shown that students may experience a higher cognitive load when learning via MR during simulated procedures, potentially impacting performance and retention of tasks and knowledge [

9]. Cost remains as a further challenge, especially for places of education and token health care sites, which may struggle to pay for the technology [

9]. Finally, hardware challenges such as depth sensor noise and spatial-temporal mismatches between the virtual and real space continue to challenge seamless integration [

7].

Despite its benefits, the HoloLens presents challenges that require further optimization. Its narrow field of view limits immersion compared to competitors, requiring frequent adjustments in perspective. Some studies indicate that MR-based learning may impose a higher cognitive load on students during simulated procedures, potentially affecting task performance and retention [

9]. Cost remains another barrier, particularly for educational institutions and smaller healthcare facilities that may struggle to afford the technology [

9]. Hardware limitations such as depth sensor noise and spatial-temporal discrepancies between virtual and real environments also pose challenges to seamless integration [

7].

The platform can go beyond training and planning and into worst-case scenario simulations for surgical residents. Trainees can handle complications, like a fracture or unexpected bleeding, using holographic patients’ anatomy. This creates a standardized global experience for surgical training and exposes residents to rare complications so that they can manage the complication multiple times before encountering it in real life [

7].

Medical education is changing, and MR technologies like the HoloLens will bridge theoretical learning and practice with experience, creating improved training and precision during surgery. Ongoing hardware and software improvements, such as embracing and expanding field of view, resolution, and ease of use will enhance their utility. Continued research and development will allow the HoloLens to serve a key part of medical education and surgical practice while transforming the teaching of anatomy and its clinical application [

10].

2.2. Apple Vision Pro

The Apple Vision Pro is emerging as an innovative technology and tool for orthopedic medical education and surgical practice, taking advantage of spatial computing and advanced technologies to transform education, pre-planning, and intraoperative processes. The high-resolution displays and field of view (~180 degrees) provide for immersive surgical simulations and can be especially effective in complex surgical procedures [

11,

14,

20].

Figure 4.

The Apple Vision Pro headset [

18]

.

Figure 4.

The Apple Vision Pro headset [

18]

.

Figure 5.

Side View of the Apple Vision Pro headset [

30]

.

Figure 5.

Side View of the Apple Vision Pro headset [

30]

.

Osso VR, the first company to develop a virtual reality product for surgical education, recently developed the Osso Health app for the Apple Vision Pro (i.e., Osso Health). The app focuses on summary orthopedic surgical procedures, including carpal tunnel release and total knee replacement, but uses spatial computing to walk users through key procedural steps and, to the extent possible, create a virtually lag free learning environment. Dr. Justin Barad, co-founder and chief strategy officer at Osso VR, indicated the app would help scale spatial computing for healthcare and provide an important new way to address educational gaps [

11,

14,

20]

Figure 6.

The Osso Health carpal tunnel surgical education feature as seen through the Apple Vision Pro. [Image courtesy of Osso VR] [

14]

.

Figure 6.

The Osso Health carpal tunnel surgical education feature as seen through the Apple Vision Pro. [Image courtesy of Osso VR] [

14]

.

.

In clinical applications, Apple Vision Pro has already been used in real surgical settings. At Cromwell Hospital in London, the device assisted surgical teams with real-time visualization of anatomical structures during spine surgeries [

11]. Similarly, at AdventHealth Surgery Center Innovation Tower, a surgical tech wore the Vision Pro goggles during a total shoulder replacement surgery, projecting mixed-reality digital images of instruments needed and procedural steps [

12]. This implementation is estimated to increase operating room efficiency by 150% to 200%, ultimately benefiting patient safety.

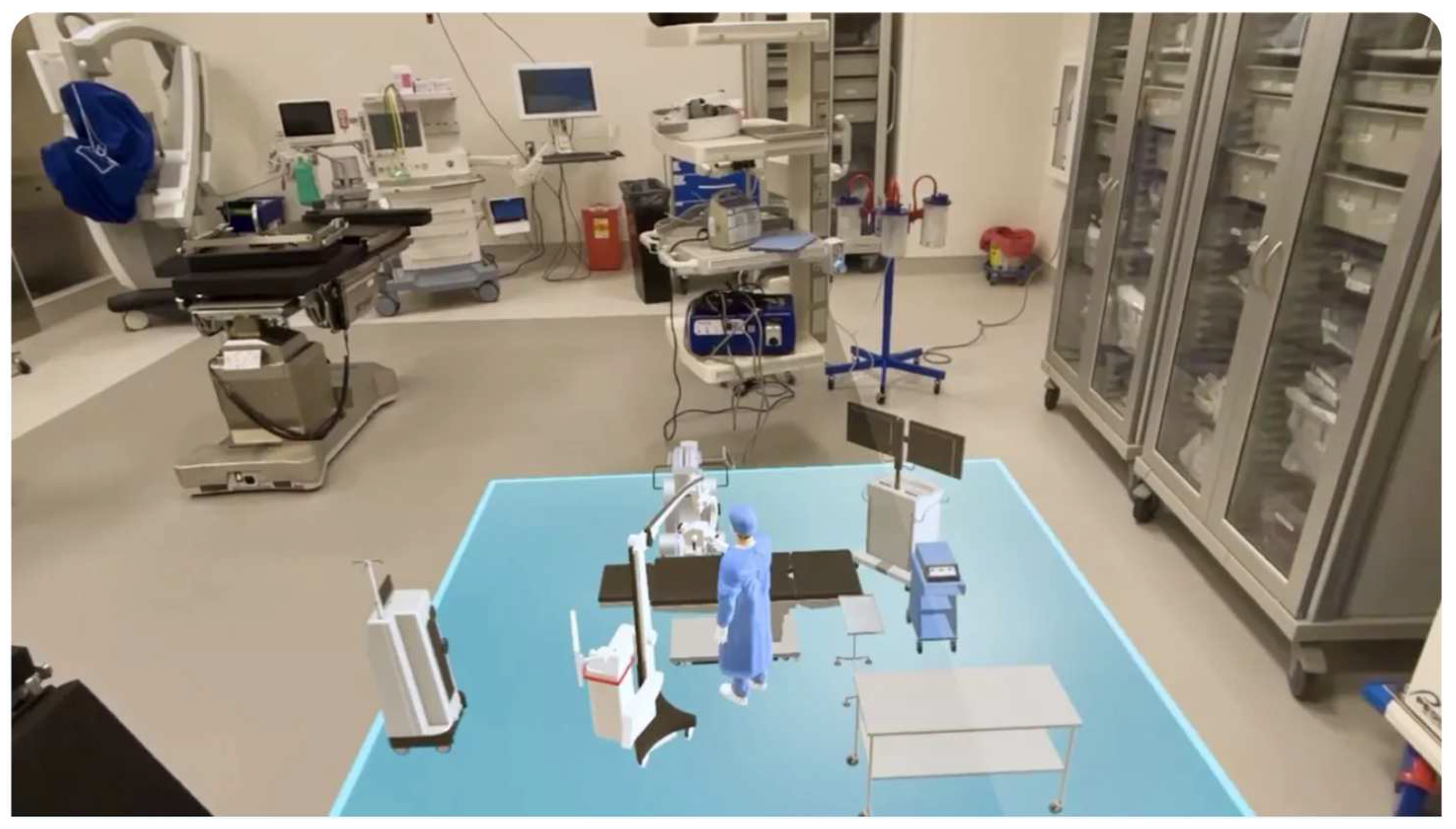

UC San Diego Health has initiated a clinical trial to evaluate the use of spatial computing apps on Apple Vision Pro in the operating room. The study aims to assess whether this technology can enhance the surgical experience by displaying patient medical imaging, vital signs, and surgical camera views in real time, potentially improving surgeons’ ergonomics [

19].

Figure 8.

Example of a minimally invasive surgery being performed at UC San Diego Health, the first hospital to evaluate the use of the Apple Vision Pro in surgery [

19]

.

Figure 8.

Example of a minimally invasive surgery being performed at UC San Diego Health, the first hospital to evaluate the use of the Apple Vision Pro in surgery [

19]

.

Though the Apple Vision Pro has potential to lessen changes for trainees to master procedures and improve accuracy, there exist challenges. The relatively short battery life (~2 hours) and expensive price point (~ $3,499) could inhibit its usage by professionals for long periods, or in widespread educational settings. Ergonomics for long-term use in addition to use in a sterile procedure could require more research and development.

As the field of orthopedic education and surgery continues to evolve, Apple Vision Pro and similar spatial computing technologies are poised to play an increasingly important role in bridging theoretical knowledge with practical application [

16]. Ongoing advancements and clinical trials will likely address current limitations, paving the way for more widespread integration into medical curricula and surgical workflows [

15,

16].

Figure 9.

Illustration of using Apple Vision Pro headset [

16]

.

Figure 9.

Illustration of using Apple Vision Pro headset [

16]

.

2.3. HTC Vive Pro

The HTC Vive Pro organizes an easy-to-use device with haptic feedback and room-scale tracking, making it a valuable tool for simulations in orthopedic training that need haptic fidelity and the ability to move the whole body. Multiple research studies have shown its advantages across a variety of surgical training modalities. When trainees participated in pedicle screw placement through VR-training using the Vive Pro, there were improvements in screw placement accuracy from increased perceptual feedback on the angulation and depth of the screw placement [

26]. In this vein, the VirtX VR-system, based on the Vive Pro device, was shown to utilize less fluoroscopy for the same quality of images [

26]. In dynamic hip screw procedures, performance metrics improved based on the Vive Pro VR-training, including reductions in incorrect steps and improved completion time [

26,

27,

34]. Further, a VR simulator for dynamic hip screw procedures showed that intraoperative imaging was improved, with trainees who had virtual training using the Vive Pro utilizing 75% less fluoroscopy and taking 66% fewer X-rays at the same level of post-training performance [

26,

34].

The HTC Vive Pro has proven effective in surgical training as an immersive and affordable alternative to other comparable devices such as the Microsoft HoloLens and the Apple Vision Pro. It also has limitations due to cybersickness (CS), cost of materials, and battery life. Approximately 30% of HTC Vive Pro users experience CS, representing a considerable barrier to long-term use in medical training. A systematic review of 223 articles on CS explains that there are three main factors involved: user related factors, technology—system factors, and environmental—content factors. Some of the main contributors to CS are age, gender, pre-VR experience, postural stability, refresh rate of the visual display, latency, field of view (FoV), and inconsistency in motion. It is important to note that CS increases with latency >20ms, and the refresh rate of the visual display <60Hz. Wider FoV > 110° may also increase immersion but could also increase motion sickness due to excessive optical flow. Three general strategies, related to hardware, software, and user adaptation can all help address issues associated with CS. Increasing the refresh rate to 90Hz, reducing latency, and offering dynamic FoV control can all distinctly reduce symptoms. Software techniques like foveated rendering and vignette effects help to manage the visual burden, and slowly letting individuals expose themselves to VR environments will allow the individual time to adapt over time [

28,

34].

Figure 10.

The HTC Vive Pro headset [

47]

.

Figure 10.

The HTC Vive Pro headset [

47]

.

Figure 11.

Example of intraoperative imaging skills used in the orthopedic setting [

34]

.

Figure 11.

Example of intraoperative imaging skills used in the orthopedic setting [

34]

.

Figure 12.

MR technique used in the orthopedic surgery setting for hip fracture [

39]

.

Figure 12.

MR technique used in the orthopedic surgery setting for hip fracture [

39]

.

Hardware costs (about $1,500 per headset) and limited battery duration (around 2.5 hours) inhibit widespread use in educational and clinical contexts. Nonetheless, when compared to devices like the Microsoft HoloLens (~$3,500) or Apple Vision Pro (~$3,499), the Vive Pro is still easier on the wallet, qualifying it as an option for an institution with strong tactile realism goals for surgical training.

Another recently published study in Advances in Medical Education and Practice revealed the efficacy of VR (Osso VR) in orthopedic trauma training. The study’s authors tested the impact of Osso VR’s immersive and interactive platform and concluded that VR training provided better learning and proficiency (execution of procedural steps) than curriculum-based training [

28,

29,

34].

Figure 13.

MR technique used to teach anatomy 39].

Figure 13.

MR technique used to teach anatomy 39].

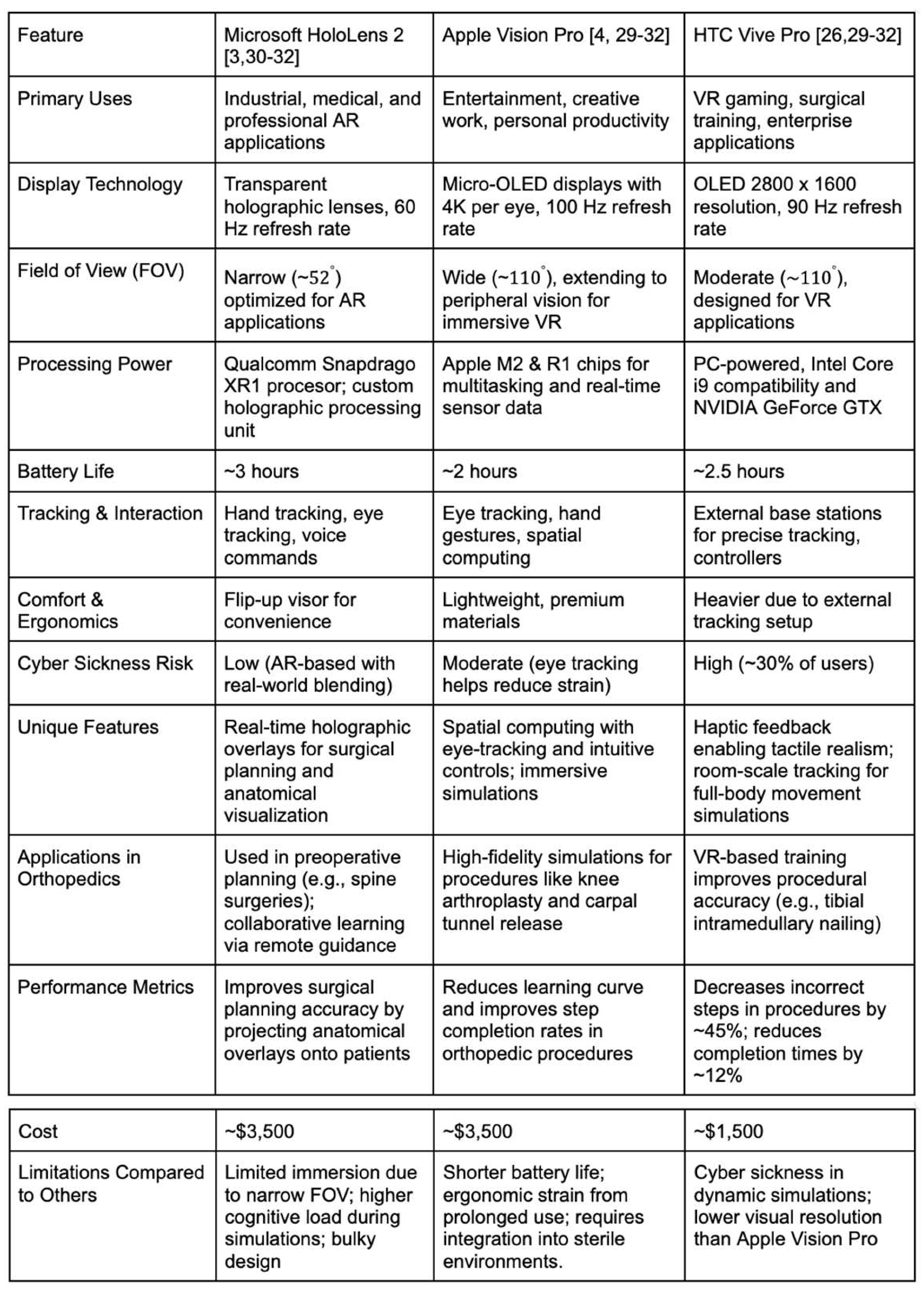

3. Comparative Analysis and Limitations of MR Technologies in Orthopedic Rehabilitation

Each technology has different strengths to address different orthopedic education and rehabilitation objectives, and institutions need to consider their priorities, and the considerations provided. The HoloLens by Microsoft is superior in augmented reality applications and is a great option when real-time holographic overlay information would be helpful (e.g., preoperative planning or collaborative learning where surgeons could provide guidance to residents remotely using shared holographic views).

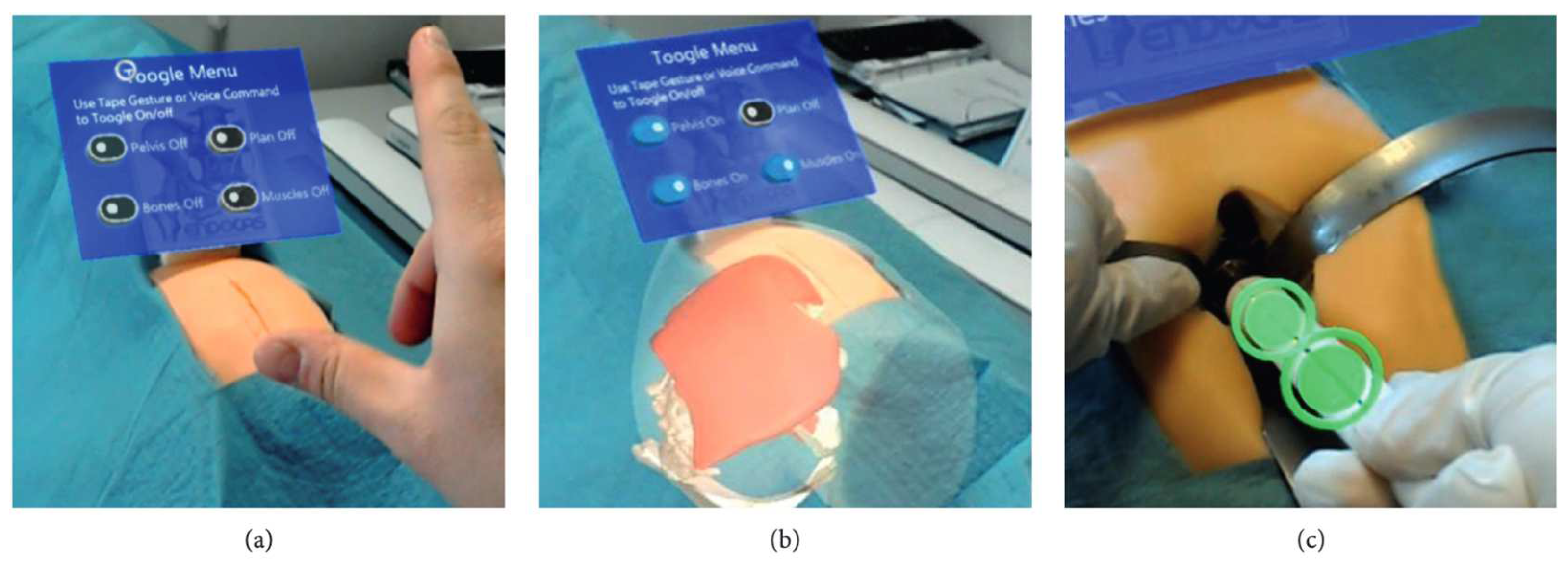

Figure 14.

Examples of AR images captured during the simulated surgical procedure: (a) a mannequin positioned on the surgical table, covered with a surgical drape to enhance simulation realism, alongside a virtual AR menu for selecting anatomical components to visualize; (b) the surgeon views the virtual anatomy in AR mode before making the surgical incision; (c) using the virtual viewfinder, the surgeon aligns the surgical instrument to ensure the acetabulum reaming follows the planned implant direction [

38]

.

Figure 14.

Examples of AR images captured during the simulated surgical procedure: (a) a mannequin positioned on the surgical table, covered with a surgical drape to enhance simulation realism, alongside a virtual AR menu for selecting anatomical components to visualize; (b) the surgeon views the virtual anatomy in AR mode before making the surgical incision; (c) using the virtual viewfinder, the surgeon aligns the surgical instrument to ensure the acetabulum reaming follows the planned implant direction [

38]

.

Some limitations of the HoloLens when using it in the context of orthopedic rehabilitation population, include ergonomics discomfort to the user. For example, when using the HoloLens for long periods in a single session (e.g., 40 minutes) it may cause postural discomfort or visual fatigue during use. There are also system registration errors rating an average of ~1.5-2.5 cm that may cause the virtual overlay to not be aligned or the closest to the physical anatomy, which is vital when precision is required in therapeutic exercise implementation. But these are just some of the issues imposed by the device as well as limitations with people wearing corrective lens and/or cost to further develop the technology, which limits the use of HoloLens in many rehabilitative programs [

37].

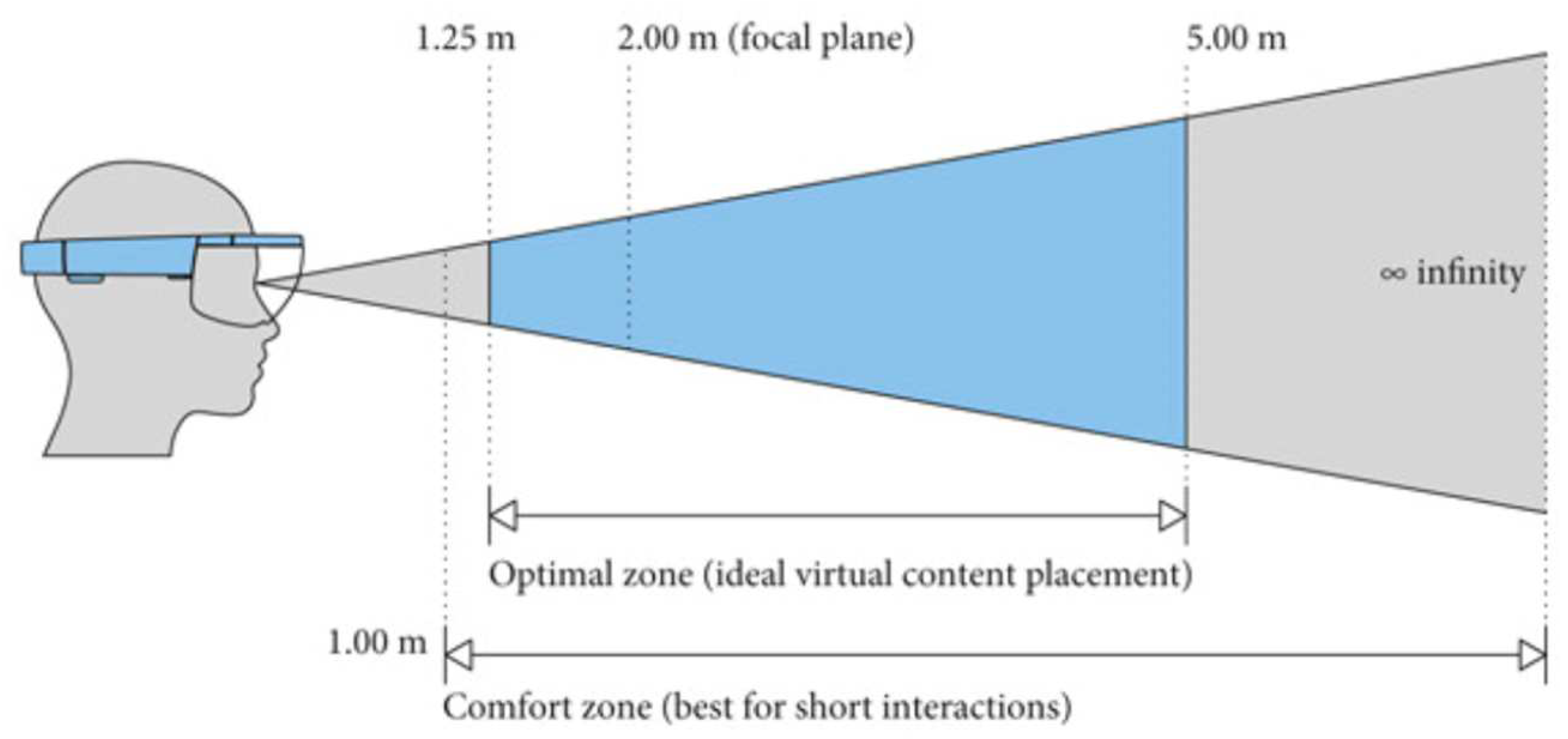

Figure 15.

Optimal and comfort zones for placing virtual content in HoloLens mixed-reality applications, as defined by Microsoft. To minimize discomfort from the vergence-accommodation conflict, virtual content should be positioned as close to 2.0 meters as possible. If placement at this distance is not feasible, discomfort can be reduced by ensuring the virtual content remains stable over time [

37].

Figure 15.

Optimal and comfort zones for placing virtual content in HoloLens mixed-reality applications, as defined by Microsoft. To minimize discomfort from the vergence-accommodation conflict, virtual content should be positioned as close to 2.0 meters as possible. If placement at this distance is not feasible, discomfort can be reduced by ensuring the virtual content remains stable over time [

37].

In contrast, the Apple Vision Pro excels at providing an immersive experience using spatial computing to create a realistic atmosphere for complex procedural simulations such as total knee arthroplasty, which could potentially shorten the learning curve for trainees. Despite its high-fidelity spatial computing, the Vision Pro has specific limitations with rehabilitation. At 600 grams, wearing the Vision Pro for a long time presents the potential for neck fatigue, lessening its value for prolonged rehabilitation. More seriously, in real time, challenges to overlay calibration such as latency or misalignment could interfere with motion-tracking reliability during guided therapeutic movements. Further, it is not designed to be used for medical procedures, which means both the operating room workflow will need to be adjusted for sterility and for use with rehabilitation modalities, as noted by surgeons who reported sustained vision focus with mixed reality screens led to eye strain that could pose potential risk to patients undergoing vision-referenced motor retraining [

3,

39,

40].

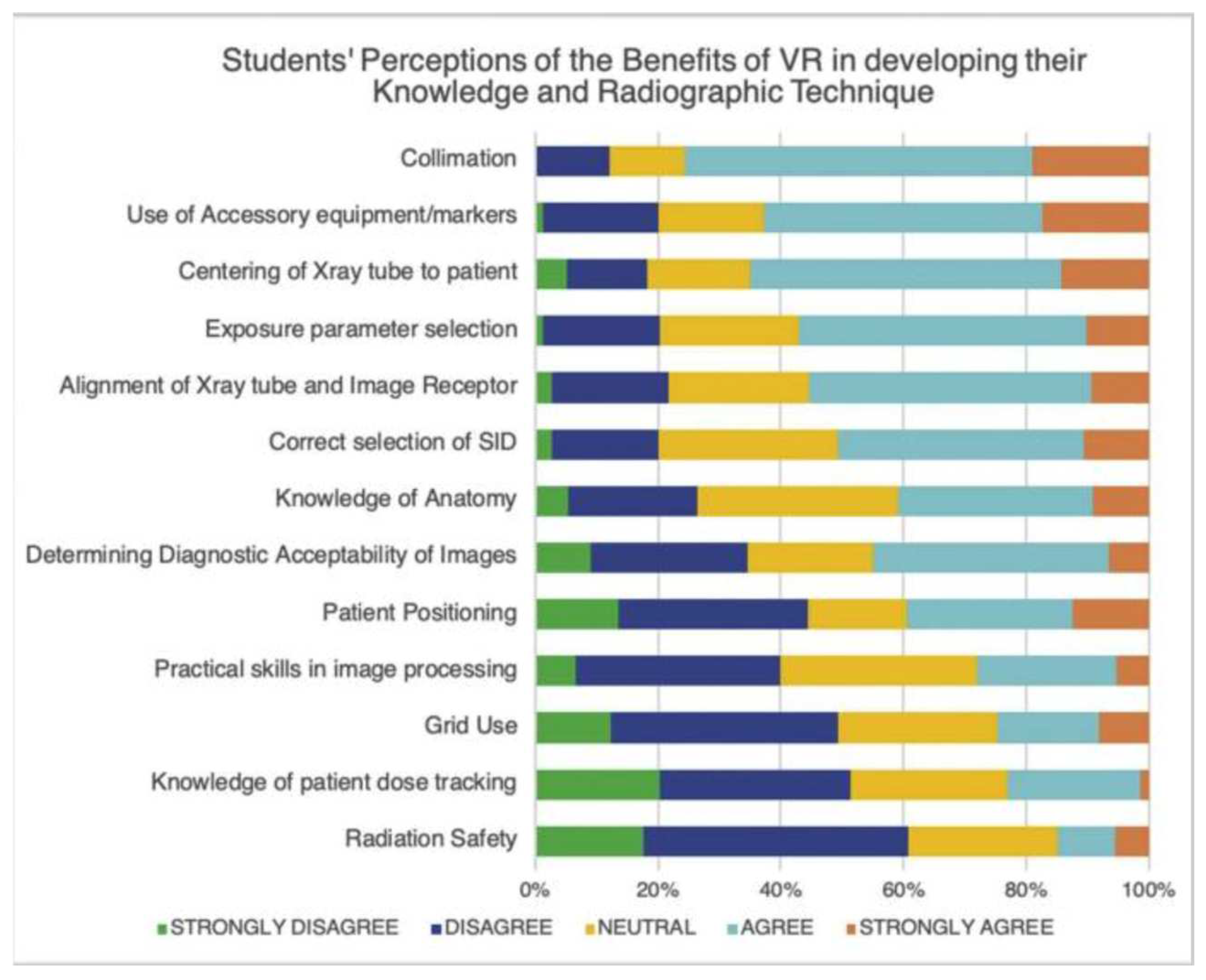

The HTC Vive Pro stands out with its haptic feedback and room-scale tracking, making it particularly effective for hands-on surgical training. This tactile realism, as demonstrated by reduced errors and improved procedural efficiency in various studies, is critical for skill acquisition. For basic X-ray imaging, first-year radiography students reported increased confidence in beam collimation, anatomical marker placement, and centering of the X-ray tube when using the HTC Vive Pro [

34,

35,

36]. In addition, VR simulator xRayWorld also helped students build a visuospatial understanding of X-ray imaging [

41].

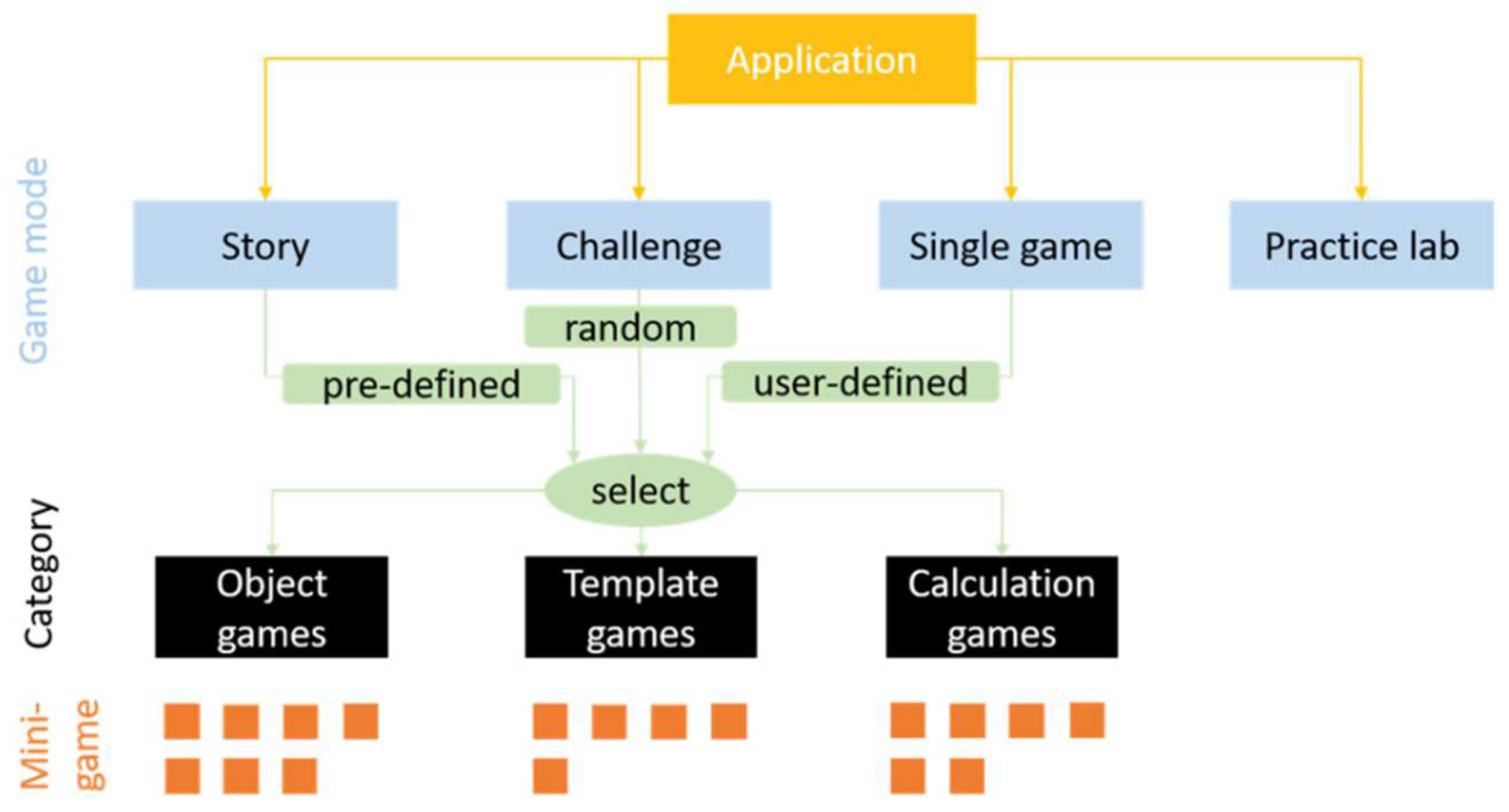

Figure 16.

xRayWorld’s overall game structure [

41]

.

Figure 16.

xRayWorld’s overall game structure [

41]

.

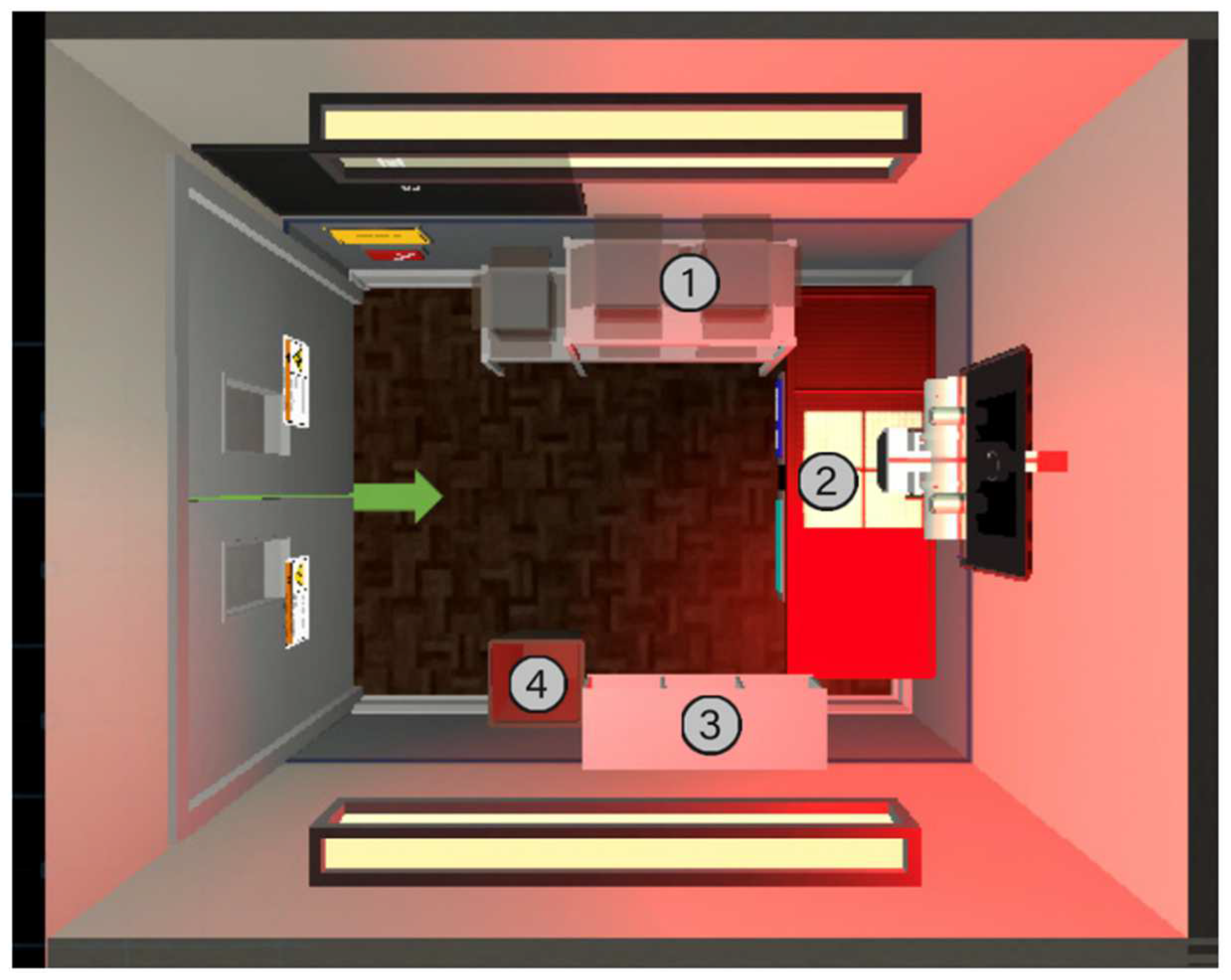

Figure 17.

Example view of a practice lab used in the xRayWorld [

41]

.

Figure 17.

Example view of a practice lab used in the xRayWorld [

41]

.

The Vive Pro’s haptic feedback and room-scale tracking face rehabilitation-specific hurdles, including cybersickness, which up to 30% of users experience during dynamic simulations, posing problems for patients with vestibular impairments. Cybersickness, characterized by nausea, disorientation, and visual discomfort, varies based on VR content attributes such as camera movement, field of view, and controllability. A study analyzing cybersickness across 52 VR scenes with 154 participants identified significant correlations between its severity and six brain activity biomarkers (e.g., Fp1 delta, Fp2 gamma, T4 beta waves) with a determination coefficient exceeding 0.9. Individual characteristics, including age and susceptibility, also influence cybersickness levels. Using this data, researchers developed predictive models to quantify and anticipate cybersickness, making the dataset broadly applicable for optimizing VR experiences and minimizing adverse effects [

29,

43].

Furthermore, patients may struggle with controller operations, necessitating extensive pre-training that delays therapy initiation. The high hardware costs (~

$1,500/headset) and limited evidence of long-term efficacy raise questions about ROI in outpatient settings [

44,

45].

Ultimately, platform choice will depend on the institutional priority, such as prioritizing AR guided anatomy visualization with HoloLens, immersive spatial computing with Vision Pro, and tactile skill development with Vive Pro, while remaining budget conscious. All these factors will factor into the platforms’ general effectiveness and appropriateness regarding orthopedic education and training.

All the platforms face the same issues: standardization gaps in tracking protocols and ethical dilemmas of maintaining data privacy. While all platforms aid in promoting engagement, if a person relies too much on a platform, it can detract from the hands-on opportunities with the patient themselves and using indirect observational measures to evaluate patient subtle biomechanical cues [

7,

45]. Improving the shortcomings of these platforms will rely on iterative hardware updates, cost mitigation, and completing rigorous clinical studies to support rehabilitation claims made on patient outcomes [

38,

39,

45].

Table 1.

Detailed Comparison of the mentioned AI-based platforms used for enterprise and educational purposes.

Table 1.

Detailed Comparison of the mentioned AI-based platforms used for enterprise and educational purposes.

4. Discussion

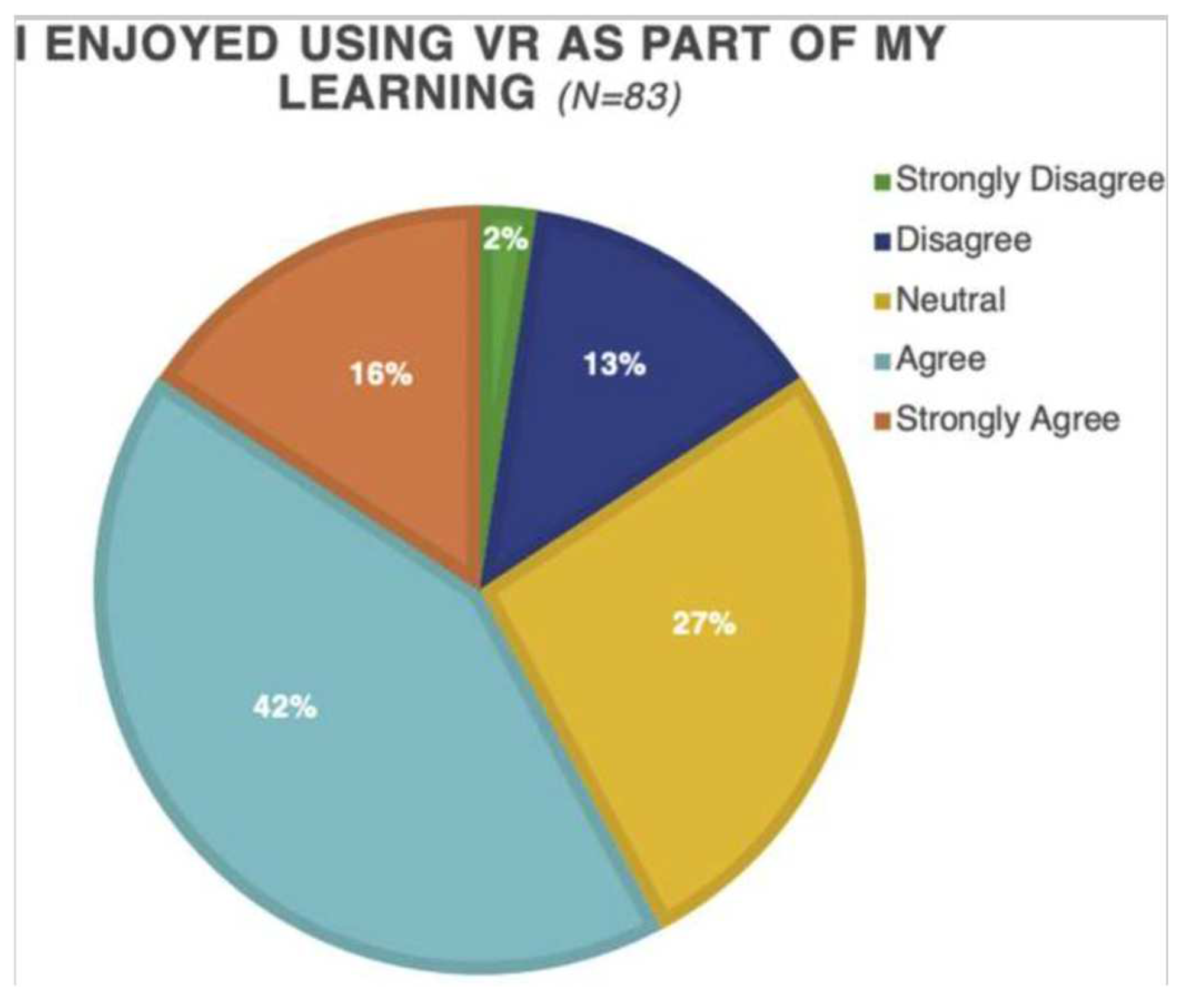

Integrating AI and MR technologies into orthopedic education represents a transformative advancement in medical training methodologies. These tools address several longstanding challenges in the field, offering innovative solutions to enhance learning and skill development. Orthopedic education requires a strong grasp of three-dimensional anatomical relationships, and mixed reality technologies provide an unparalleled way to visualize and interact with complex structures. For example, virtual reality platforms like the HTC Vive Pro have been used to improve spatial understanding in radiography students. A study by O’Connor et al. (2021) demonstrated that a VR simulator increased student confidence in beam collimation, anatomical marker placement, centering of the X-ray tube, and exposure parameter selection [

34,

35].

Figure 18.

Study results illustrating student’s enjoyment of VR-based learning [

35]

.

Figure 18.

Study results illustrating student’s enjoyment of VR-based learning [

35]

.

Figure 19.

Study results illustrating students’ opinion on VR’s benefits in developing their confidence across a variety of radiographic settings [

35]

.

Figure 19.

Study results illustrating students’ opinion on VR’s benefits in developing their confidence across a variety of radiographic settings [

35]

.

Mixed reality also facilitates procedural training, allowing students to repeatedly perform techniques without any danger to patients in a way that expedites the learning curve for complex orthopedic procedures. Personalized learning experiences are another significant advantage that arise in the context of mixed reality, wherein AI platforms adjust to adapt to the individual learning styles and speed of learners. Because of this personalization, knowledge retention and skill acquisition is enhanced. Lenz et al. (2021a) led a study that utilized a VR simulator called xRayWorld, which employed gamification and visuospatial tasks to help students develop an understanding of X-ray imaging. In this example, the versatility of mixed reality tools in medical education is further reinforced [

34,

35].

Social distancing has made learning remotely more important and mixed reality technologies can provide high-quality distance learning opportunities when face-to-face teaching would otherwise not be possible [

36]. AI can also promote data-driven education by providing educators with performance data in simulations to provide valuable insight into areas of the curriculum and where individual students may need additional support [

3].

Mixed reality applications can support students and medical professionals in the context of clinical practice not only in regard to procedural training but also in the context of diagnostic assessments since virtual environments allow practitioners to view, observe and/or manipulate complex anatomical structures to make quality assessments. Virtual reality and mixed reality also offer value in relation to patient care as mixed reality and VR experiences can improve patients’ understanding of their medical conditions leading to higher rates of adherence. Finally, mixed reality improves learning opportunities as the technologies are remote, increasing opportunities for equitable learning via remote collaboration between learners and educators or educators from around the world or community or organizational partnerships that may be located outside of the geographical area. Studies suggest immersive experiences activate the prefrontal cortex, enhancing engagement, retention, and cognitive learning functions [

36].

Figure 20.

Example of a doctor using MR techniques for preoperative planning [

5]

.

Figure 20.

Example of a doctor using MR techniques for preoperative planning [

5]

.

Despite their potential, these technologies face implementation challenges. Cost and accessibility remain significant barriers, as high-end devices like the Microsoft HoloLens (~

$3,500) or Apple Vision Pro (~

$3,499) are expensive, limiting their widespread adoption in educational institutions [

3,

5]. Technical limitations persist, with current devices often lacking the fidelity to fully replicate tactile feedback crucial for orthopedic procedures [

36]. Educators also face difficulties integrating these tools into existing curricula while ensuring alignment with traditional teaching methods [

3]. Finally, more research is needed to validate the long-term benefits of AI-enhanced education on clinical competence [

5].

As mixed reality and AI evolve, they promise to transform orthopedic education by bridging theoretical knowledge with practical application. Addressing current limitations will be key to unlocking their full potential and ensuring equitable access across institutions globally.

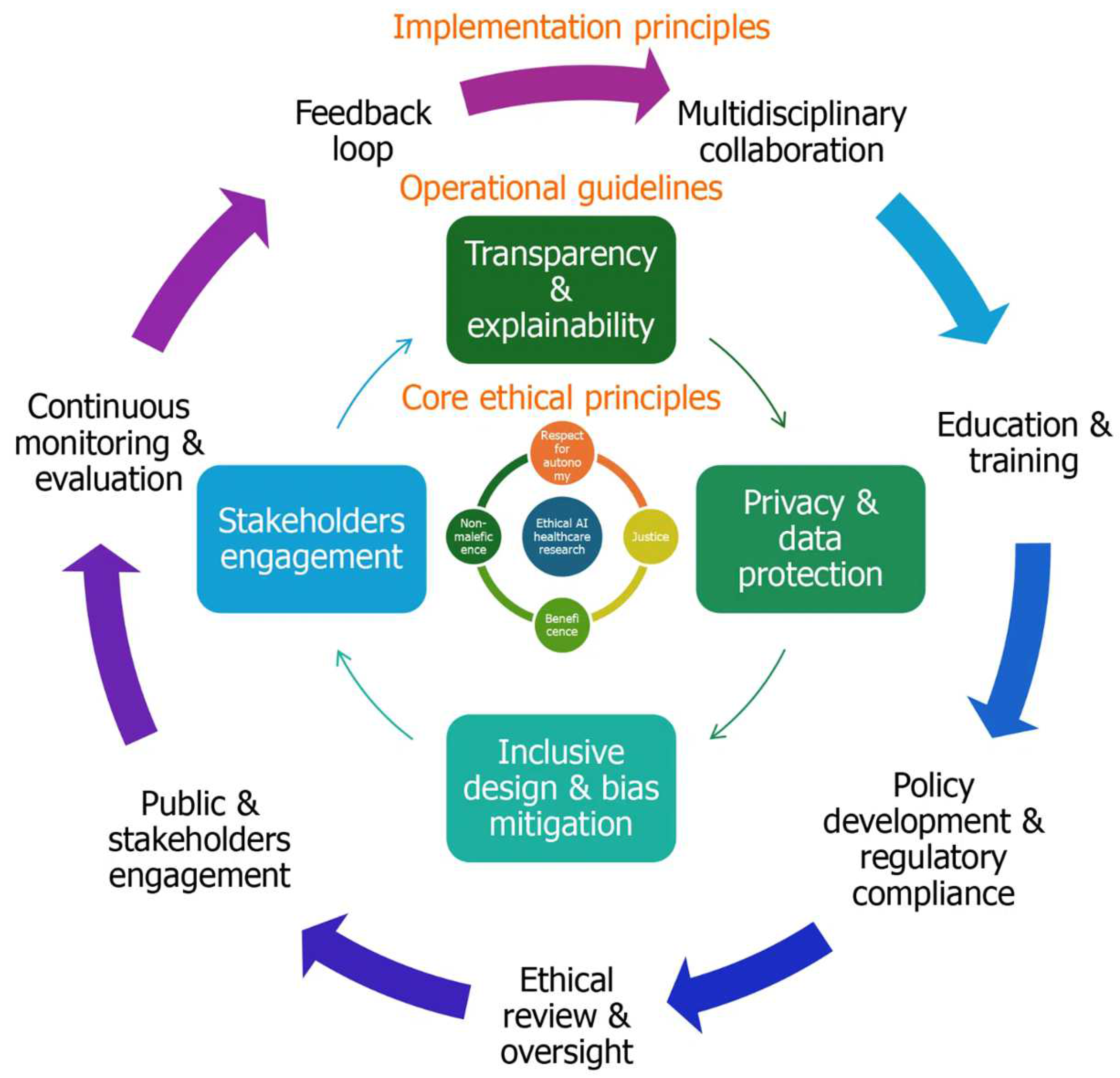

5. Limitations to Integration of AI-Based Platforms in Orthopedic Medical Education

The integration of artificial intelligence (AI) into orthopedic education faces several significant barriers that need to be addressed for successful implementation. These challenges span various domains, including data standardization, algorithm evaluation, ethics, and curriculum integration.

Data standardization remains a critical hurdle in AI adoption for orthopedic education. The heterogeneity of medical data sources, formats, and terminologies poses significant challenges for AI model development and deployment. A study by SignalFire (2024) highlights that most healthcare data currently reside in siloed systems within individual health organizations, making it difficult to access and utilize for AI training. Furthermore, regulations such as HIPAA and GDPR often complicate the sharing of patient data. The study also notes that while standards like FHIR and OMOP have improved data-sharing capabilities, they lack the flexibility required for multimodal longitudinal datasets increasingly used in AI research [

48].

Algorithm evaluation presents another significant barrier. The accuracy and reliability of AI algorithms in orthopedic applications are crucial for their acceptance in educational and clinical settings. A recent study published in Bone and Joint Research (2023) emphasizes the need for robust reporting and validation frameworks to prevent avoidable errors and biases in AI applications for orthopedic surgery [

45]. The study also highlights the importance of establishing systematic validation processes to allow for the safe adoption of AI technology in clinical practice.

Ethical considerations form a substantial barrier to AI integration in orthopedic education. A comprehensive ethical framework is essential to address issues such as algorithmic bias, data privacy, and equitable access to AI-driven healthcare innovations. A study published in the World Journal of Gastroenterology (2024) proposes an ethical framework centered around the four key principles of medical ethics: respect for autonomy, beneficence, non-maleficence, and justice. The framework emphasizes the need for regular audits of AI systems for bias and the implementation of corrective measures when disparities are identified [

49].

Figure 21.

A proposed ethical framework for integrating AI into healthcare [

49]

.

Figure 21.

A proposed ethical framework for integrating AI into healthcare [

49]

.

Integrating AI into the medical school curriculum presents its own set of challenges. Despite the growing use of AI in healthcare, there is a notable lack of formal AI instruction in undergraduate medical education. A study published in PMC (2022) highlights that only 5.9% of medical schools in the United States offer formal AI training. The study identifies several barriers to AI curriculum integration, including uncertainty about effective delivery methods, limitations in available curricular hours, and a lack of faculty expertise in A. The study goes on to propose that students may start to rely on AI for clinical decision-making and hamper their growth as physicians [

50].

Addressing these barriers requires a multifaceted approach involving collaboration between medical educators, technology developers, and policymakers. As AI continues to evolve and become more prevalent in healthcare, overcoming these challenges will be crucial for preparing future orthopedic surgeons to effectively utilize and critically evaluate AI technologies in their practice.

6. Conclusions

The incorporation of AI and mixed reality technology into orthopedic medical education constitutes a significant change in how we will train future orthopedic surgeons. The benefits of immersive and interactive education are unparalleled with the availability of devices like the Microsoft HoloLens, Apple Vision Pro, and HTC Vive Pro, facilitating the acquisition of complex orthopedic skills and knowledge [

8,

46,

47].

While challenges related to implementation and integration persist, particularly related to costs and technical constraints, as well as further integration into the curriculum, the potential benefits of these technologies are worth it. Benefits in spatial understanding, procedural training, and personalized learning are readily identified advantages of these technologies, with ongoing research looking to explore the optimal utilization of AI, enabling even more personalized and optimal learning pathways [

35,

36,

37,

38,

39,

40,

41,

42]. As we continue to grow into these technologies, there will clearly be increasing utilization in orthopedic education. Therefore, it will be paramount for educators, technology developers, and AI researchers to continue to collaborate in developing these innovations and moving forward in orthopedic medical education [

37].

Future research should focus on developing standardized protocols for integrating these technologies into medical curricula and conducting longitudinal studies to assess the long-term impact on clinical competence and patient outcomes.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Writing- Original Draft, Writing- Review & Editing, Visualization, Methodology, K.S.; Writing- review and editing, supervision, and validation, R.K.; Methodology, Supervision, Validation, Writing- Review and Editing, P.P.; Project Administration, Supervision, Writing- Review and Editing, J.O.; Formal Analysis, Writing- Review and Editing, T.S.; Writing- Review and Editing, Visualization, S.V.; Supervision, Methodology, Writing- Review and Editing, T.H.; Supervision, Writing- Review and Editing, E.W.; Methodology, Writing- Review and Editing; D.A.; Formal Analysis, Writing- Review and Editing, C.G.; Formal Analysis, Writing- Review and Editing, R.J..; Formal Analysis, Writing- Review and Editing, N.Z.; Methodology, Writing- Review and Editing, A.T.; All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Acknowledgments

Thank you to Boomie Xiong for providing us with an APC waiver.

Conflicts of Interest

Ram Jagadeesan has a conflict of interest as an employee that holds stock interest in Cisco.

References

- Rasouli S, Alkurdi D, Jia B. The Role of Artificial Intelligence in Modern Medical Education and Practice: A Systematic Literature Review. Published online July 26, 2024. [CrossRef]

- Misir A. Orthopedic residency is a demanding period during which trainees must acquire complex surgical skills, interpret radiological images, and rapidly integrate clinical knowledge. Recent advances in artificial intelligence (AI) now offer promising tools to augment traditional training methods and help r. Linkedin.com. Published February 28, 2025. Accessed March 26, 2025. https://www.linkedin.com/pulse/enhancing-orthopedic-residency-training-artificial-abdulhamit-misir-siyff/.

- Gupta, N.; Walker, J.; Turnow, M.; Kasmenn, M.; Patel, H.; Sydow, E.; Manes, T.; Williamson, T.; Patel, J. Use of Mixed Reality Technologies by Orthopedic Surgery Residents: A Cross-Sectional Study of Trainee Perceptions. J. Orthop. Exp. Innov. 2024, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooper HJ. A View of Mixed-Reality Tech’s Future in Orthopedics. OrthoFeed. Published March 30, 2024. Accessed March 26, 2025. https://orthofeed.com/2024/03/30/a-view-of-mixed-reality-techs-future-in-orthopedics/.

- Yang, J.; Zhang, J.; Zeng, C.; Fang, Y.; Xue, M.; Wang, H.; Zhou, H.; Xie, Y.; Liu, P.; Ye, Z. Application and prospect of mixed reality technology in orthopedics. Digit. Med. 2023, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Texas, S. Revolutionizing Medical Education: The HoloAnatomy Experience | IT.tamu.edu. Tamu.edu. Published February 18, 2025. Accessed March 26, 2025. https://it.tamu.edu/about/news/2024/05/hololens-news-story.php.

- Tătaru, O.S.; Ferro, M.; Marchioni, M.; Veccia, A.; Coman, O.; Lasorsa, F.; Brescia, A.; Crocetto, F.; Barone, B.; Catellani, M.; et al. HoloLens® platform for healthcare professionals simulation training, teaching, and its urological applications: an up-to-date review. Ther. Adv. Urol. 2024, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khoo G, Yap A, Yak WY. Medical education goes Holographic with mixed reality from Microsoft. Sin-gapore News Center. Published January 11, 2022. Accessed March 26, 2025. https://news.microsoft.com/en-sg/2022/01/11/medical-education-goes-holographic-with-mixed-reality-from-microsoft/.

- Connolly, M.; Iohom, G.; O’brien, N.; Volz, J.; O’muircheartaigh, A.; Serchan, P.; Biculescu, A.; Gadre, K.G.; Soare, C.; Griseto, L.; et al. Delivering clinical tutorials to medical students using the Microsoft HoloLens 2: A mixed-methods evaluation. BMC Med Educ. 2024, 24, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cleveland Clinic. Case Western Reserve, Cleveland Clinic Collaborate with Microsoft on Earth-Shattering Mixed-Reality Technology for Education. www.case.edu. Published 2015. Accessed March 26, 2025. https://case.edu/hololens/.

- Osso, VR. Osso Health Medical Training App Launches for Apple Vision Pro. www.ossovr.com. Pub-lished April 11, 2024. Accessed March 26, 2025. https://www.ossovr.com/press-releases/osso-health-medical-training-apple-vision-pro.

- Koblentz, E. Apple Highlights Stryker, an NJIT Alum’s Medical Tech Group, for VisionPro App. NJIT News. Published March 15, 2024. Accessed March 27, 2025. https://news.njit.edu/apple-highlights-stryker-njit-alums-medical-tech-group-visionpro-app.

- Orthopedics Today. Osso VR launches immersive reality medical training app. Healio.com. Published April 14, 2024. Accessed March 26, 2025. https://www.healio.com/news/orthopedics/20240412/osso-vr-launches-immersive-reality-medical-training-app.

- Whooley, S. Osso VR launches medical training app for Apple Vision Pro. MassDevice. Published April 11, 2024. Accessed March 26, 2025. https://www.massdevice.com/osso-vr-launches-app-apple-vision-pro/.

- Apple. Apple Vision Pro unlocks new opportunities for health app developers. Apple Newsroom. Published March 11, 2024. Accessed March 26, 2025. https://www.apple.com/newsroom/2024/03/apple-vision-pro-unlocks-new-opportunities-for-health-app-developers/.

- Egger, J.; Gsaxner, C.; Luijten, G.; Chen, J.; Chen, X.; Bian, J.; Kleesiek, J.; Puladi, B. Is the Apple Vision Pro the Ultimate Display? A First Perspective and Survey on Entering the Wonderland of Precision Medicine. JMIR Serious Games 2024, 12, e52785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janko Roettgers. Microsoft HoloLens Costs Developers $3000, Starts Shipping Next Month. Variety. Published February 29, 2016. Accessed March 26, 2025. https://variety.com/2016/digital/news/microsoft-hololens-dev-kit-3000-dollars-preorders-1201718230/.

- Apple Inc. Introducing Apple Vision Pro: Apple’s first spatial computer. Apple Newsroom. Published June 5, 2023. Accessed March 26, 2025. https://www.apple.com/newsroom/2023/06/introducing-apple-vision-pro/.

- Brubaker, M. Clinical Trial Evaluates Spatial Computing App on Apple Vision Pro in Operating Room. UC San Diego Health. Published September 16, 2024. Accessed March 26, 2025. https://health.ucsd.edu/news/press-releases/2024-09-16-clinical-trial-evaluates-spatial-computing-app-on-apple-vision-pro-in-operating-room/.

- Dermody, T. Osso VR launches surgical training app for Apple Vision Pro. Perplexity AI. Published April 11, 2024. Accessed March 26, 2025. https://www.mobihealthnews.com/news/osso-vr-launches-surgical-training-app-apple-vision-pro.

- Johnson, T. Surgical team at AdventHealth performs world’s first of its kind procedure using Apple Vision Pro mixed reality system. AdventHealth. Published November 11, 2024. Accessed March 26, 2025. https://www.adventhealth.com/business/adventhealth-central-florida-media-resources/news/surgical-team-adventhealth-performs-worlds-first-its-kind-procedure-using-apple-vision-pro-mixed.

- Chen, C.; Zhang, L.; Luczak, T.; Smith, E.; Burch, R.F. Using Microsoft HoloLens to improve memory recall in anatomy and physiology: A pilot study to examine the efficacy of using augmented reality in education. J. Educ. Technol. Dev. Exch. 2019, 12, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stojanovska, M.; Tingle, G.; Tan, L.; Ulrey, L.; Simonson-Shick, S.; Mlakar, J.; Eastman, H.; Gotschall, R.; Boscia, A.; Enterline, R.; et al. Mixed Reality Anatomy Using Microsoft HoloLens and Cadaveric Dissection: A Comparative Effectiveness Study. Med Sci. Educ. 2019, 30, 173–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richards, S. Student Engagement Using HoloLens Mixed-Reality Technology in Human Anatomy Laboratories for Osteopathic Medical Students: an Instructional Model. Med Sci. Educ. 2023, 33, 223–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ali, A.; Baseer, N.; Huma, Z.; Yousafzai, Y.M.; Shah, I.; Zia, A.; Alorini, M.; Sethia, N. Mixed reality model for learning and teaching in anatomy using peer assisted learning approach. Eur. J. Anat. 2023, 27, 129–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camp JV. HTC Vive Pro Review: An Expensive VR Upgrade. WIRED. Published May 11, 2018. Accessed March 26, 2025. https://www.wired.com/review/review-htc-vive-pro/.

- Lohre, R.; Bois, A.J.; Pollock, J.W.; Lapner, P.; McIlquham, K.; Athwal, G.S.; Goel, D.P. Effectiveness of Immersive Virtual Reality on Orthopedic Surgical Skills and Knowledge Acquisition Among Senior Surgical Residents. JAMA Netw. Open 2020, 3, e2031217–e2031217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biswas, N.; Mukherjee, A.; Bhattacharya, S. “Are you feeling sick?” – A systematic literature review of cybersickness in virtual reality. ACM Comput. Surv. 2024, 56, 1–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osso, VR. New Study Shows Virtual Reality Training Outperforms Traditional Methods in Orthopedic Surgical Education. Ossovr.com. Published November 9, 2023. Accessed March 26, 2025. https://www.ossovr.com/press-releases/vr-training-outperforms-traditional-methods-in-orthopedic-surgical-education.

- Sarwar F. Apple Vision Pro vs. Microsoft HoloLens: Battle of XR Headsets. Syntech. Published February 14, 2025. Accessed March 26, 2025. https://syntechhome.com/blogs/news/apple-vision-pro-vs-microsoft-hololens.

- Ogundairo, P. Hololens vs Vision Pro: Which is a better buy? TechWriteable. Published March 13, 2024. Accessed March 26, 2025. https://techwriteable.com/microsoft-hololens-2-vs-apple-vision-pro-which-is-a-better-buy/.

- Bowden Z. Apple’s AR Vision Pro headset isn’t the HoloLens competitor I thought it was going to be. Windows Central. Published June 6, 2023. Accessed March 26, 2025. https://www.windowscentral.com/apple/apples-ar-vision-pro-headset-isnt-the-hololens-competitor-i-thought-it-was-going-to-be.

- Lamb, A.; McKinney, B.; Frousiakis, P.; Diaz, G.; Sweet, S. A Comparative Study of Traditional Technique Guide versus Virtual Reality in Orthopedic Trauma Training. Adv. Med Educ. Pr. 2023, ume 14, 947–955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pratap, J.; Laane, C.; Chen, N.; Bhashyam, A. Virtual reality training for intraoperative imaging in orthopaedic surgery: an overview of current progress and future direction. Front. Virtual Real. 2024, 5, 1392825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O'Connor, M.; Stowe, J.; Potocnik, J.; Giannotti, N.; Murphy, S.; Rainford, L. 3D virtual reality simulation in radiography education: The students' experience. Radiography 2021, 27, 208–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fabiana D’Urso, Prisco Priscitelli, Alessandro Miani and Francesco Broccolo. Revolutionizing Medical Education: The Impact of Virtual and Mixed Reality on Training and Skill Acquisition. Trends Telemed E-Health. 4(5). TTEH. 000598. 2024. [CrossRef]

- Condino, S.; Turini, G.; Parchi, P.D.; Viglialoro, R.M.; Piolanti, N.; Gesi, M.; Ferrari, M.; Ferrari, V. How to Build a Patient-Specific Hybrid Simulator for Orthopaedic Open Surgery: Benefits and Limits of Mixed-Reality Using the Microsoft HoloLens. J. Heal. Eng. 2018, 2018, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Condino, S.; Turini, G.; Parchi, P.D.; Viglialoro, R.M.; Piolanti, N.; Gesi, M.; Ferrari, M.; Ferrari, V. How to Build a Patient-Specific Hybrid Simulator for Orthopaedic Open Surgery: Benefits and Limits of Mixed-Reality Using the Microsoft HoloLens. J. Heal. Eng. 2018, 2018, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, H.-Z.; Feng, X.-B.; Shao, Z.-W.; Xie, M.; Xu, S.; Wu, X.-H.; Ye, Z.-W. Application and Prospect of Mixed Reality Technology in Medical Field. Curr. Med Sci. 2019, 39, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, K.C.; Sun, Y.E.; Kumta, S.M. Review and Future/Potential Application of Mixed Reality Technology in Orthopaedic Oncology. Orthop. Res. Rev. 2022, ume 14, 169–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lenz F, Fock M, Kramer T, Petersen Y, Teistler M. A Virtual Reality Game to Support Visuospatial Understanding of Medical X-Ray Imaging.; 2021. Accessed March 27, 2025. https://hs-flensburg.de/sites/default/files/2022-02/xrayworld_segah2021_finalsubmission.pdf.

- Oh, H.; Son, W. Cybersickness and Its Severity Arising from Virtual Reality Content: A Comprehensive Study. Sensors 2022, 22, 1314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu TW, Siu PKT, Wong TM (2022) Virtual Reality in Sport Rehabilitation: A Narrative Review. J Athl Enhanc 11:6.

- Lazar, M. A Guide to Applying Virtual Reality in Medical Training. HyperSense Blog. Published Sep-tember 27, 2024. Accessed March 27, 2025. https://hypersense-software.com/blog/2024/09/25/virtual-reality-medical-training/. 27 March 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Lisacek-Kiosoglous, A.B.; Powling, A.S.; Fontalis, A.; Gabr, A.; Mazomenos, E.; Haddad, F.S. Artificial intelligence in orthopaedic surgery. Bone Jt. Res. 2023, 12, 447–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shanbhag, N.M.; Bin Sumaida, A.; Al Shamisi, K.; Balaraj, K. Apple Vision Pro: A Paradigm Shift in Medical Technology. Cureus 2024, 16, e69608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- HTC Vive Pro. VIVE Pro Eye Launches Today In North America, Setting A New Standard For Enterprise Virtual Reality. Htc.com. Published 2019. Accessed March 27, 2025. https://www.htc.com/us/newsroom/2019-06-06/.

- Pezzullo T, Rahoof S, Simcox E. How standardized data and smarter sharing can unlock healthcare AI’s full potential. Signalfire.com. Published November 20, 2024. Accessed March 28, 2025. https://www.signalfire.com/blog/healthcare-ai-data.

- A Abujaber, A.; Nashwan, A.J. Ethical framework for artificial intelligence in healthcare research: A path to integrity. World J. Methodol. 2024, 14, 94071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ngo, B.; Nguyen, D.; Vansonnenberg, E. The Cases for and against Artificial Intelligence in the Medical School Curriculum. Radiol. Artif. Intell. 2022, 4, e220074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).