1. Introduction

Food production in Sub-Saharan Africa (SSA) has exhibited stagnation or decline on a per capita basis for over four decades (Xiong & Tarnavsky, 2020). This persistent food insecurity is characterized by insufficient food availability, price volatility, high poverty rates, and susceptibility to multifaceted challenges like extreme weather events and climate change (Khumalo, 2021; Veste et al., 2024). The situation is further exacerbated by a rapidly growing population, declining soil fertility, and increasing land limitations in densely populated rural areas (Khumalo, 2021). A growing consensus acknowledges the need for an SSA-specific green revolution to enhance food production and quality, particularly within the small-scale, low-productivity farms that support two-thirds of the region’s population (Xiong & Tarnavsky, 2020; Amede et al., 2023).

Despite the challenges faced by smallholder farmers, family farms are undeniably the cornerstone of African agriculture (Chao, 2024). They provide employment for a large portion of the population, estimated at two-thirds, and cultivate a significant majority of the land, exceeding 60% (Quendler et al., 2020). These farms are typically small in size, with many in Sub-Saharan Africa being less than one hectare. Their production is diverse, encompassing food and cash crops, livestock, and catering to both subsistence and market needs (Bosc et al., 2018). Traditional practices are often employed, with limited use of modern advancements like irrigation, fertilizers, and improved seeds (Francis, 2023). While family farms play a vital role in agricultural development and poverty reduction, their restricted access to resources like high-yielding seeds, essential inputs, markets, climate change, and financing hinders their ability to reach their full potential in terms of production and resilience (Langyintuo, 2020; Wahab et al., 2020; Menkir et al., 2022).

Smallholder family farms in Tanzania, like many across Sub-Saharan Africa (SSA), are dominated by maize cultivation (Giller et al., 2021). This crop serves as the primary source of calories and is consumed by over half of the SSA population (Galani et al., 2022). Tanzania ranks fourth in maize production within SSA, following South Africa, Nigeria, and Ethiopia, with an output of 5.3 million tons in 2013 (Nyaligwa et al., 2017). Historically, Tanzania has boasted a national surplus and sees potential for exporting maize to neighboring regions (Bryceson et al., 2018). This has led the Tanzanian government to prioritize improvements in maize productivity, aiming to establish the country as a regional breadbasket (Were, 2021). However, despite maize’s significance, its productivity in Tanzania remains low. Traditional rain-fed farming practices employed by smallholders, who contribute the majority of Tanzania’s maize production, are responsible for this limited productivity (Said and Temba, 2023). Furthermore, weather variability, particularly droughts, presents another substantial challenge, especially for smallholder livelihoods (Ojara et al., 2022).

The influence of improved maize seeds on Tanzanian family farms is a multifaceted issue. While research has largely focused on the potential for increased yield and food security through adoption (Gebre et al., 2021; Kihara et al., 2021; Mugula et al., 2023), recent studies highlight the importance of socioeconomic and environmental factors that can act as barriers to widespread use (Yusuph et al., 2023; Shaban & Pauile, 2023). Kadigi (2020a) further emphasizes the need for risk analysis and management strategies when adopting improved farming practices, which can be applied to maize seed adoption as well. However, there is a lack of robust empirical evidence on the intricate interplay between these factors and their impact on adoption and effectiveness. This necessitates the exploration of stochastic simulation techniques to address the inherent complexity of this issue.

This study employs a comprehensive stochastic simulation analysis to investigate the potential farm and household-level impacts of adopting improved maize seeds in Tanzania (keeping other factors constant). It specifically addresses critical seed policy questions: firstly, whether improved seeds demonstrably influence yield, and secondly, the magnitude of their productivity impact. Agriculture is inherently stochastic, meaning factors like weather, pest outbreaks, and market prices can vary unpredictably. A stochastic model can account for this variability, providing a more realistic picture of potential outcomes (Nguyen et al., 2024). Contributing to the existing impact assessment literature, this study utilizes a rigorous approach incorporating the inherently stochastic nature of Tanzania’s agricultural sector to examine the productivity gap between those using improved seeds and those without. Likewise, the study findings are more applicable to policy perspectives, as Tanzania is currently developing a Tanzania Seed Sector Development Strategy 2030 (TSSDS 2030). Among others, the TSSDS aims to streamline the government’s actions to foster food production and security and improve livelihoods in the country and the region (Minde et al., 2024).

In order to account for spatial variability in environmental and production conditions that significantly influence maize performance, the study groups the study are into agro-ecological zones bearing in mind that these zones differ in terms of soil fertility, rainfall patterns, temperature, and elevation all of which affect the effectiveness of agricultural inputs, including improved seeds. By analyzing impacts across these zones, the study generated more accurate, context-specific insights into where improved seeds perform best and where additional interventions may be needed. This disaggregation allows for targeted policy recommendations, resource allocation, and scaling strategies that consider the unique challenges and opportunities of each zone, ultimately leading to more effective seed sector development and improved food security outcomes. The subsequent sections of this paper are structured as follows:

Section 2 outlines the theoretical and conceptual framework,

Section 3 details the methodology employed to assess the impact of improved seeds on maize productivity,

Section 4 presents the key findings, and

Section 5 discusses the major results.

2. Theoretical and Conceptual Framework

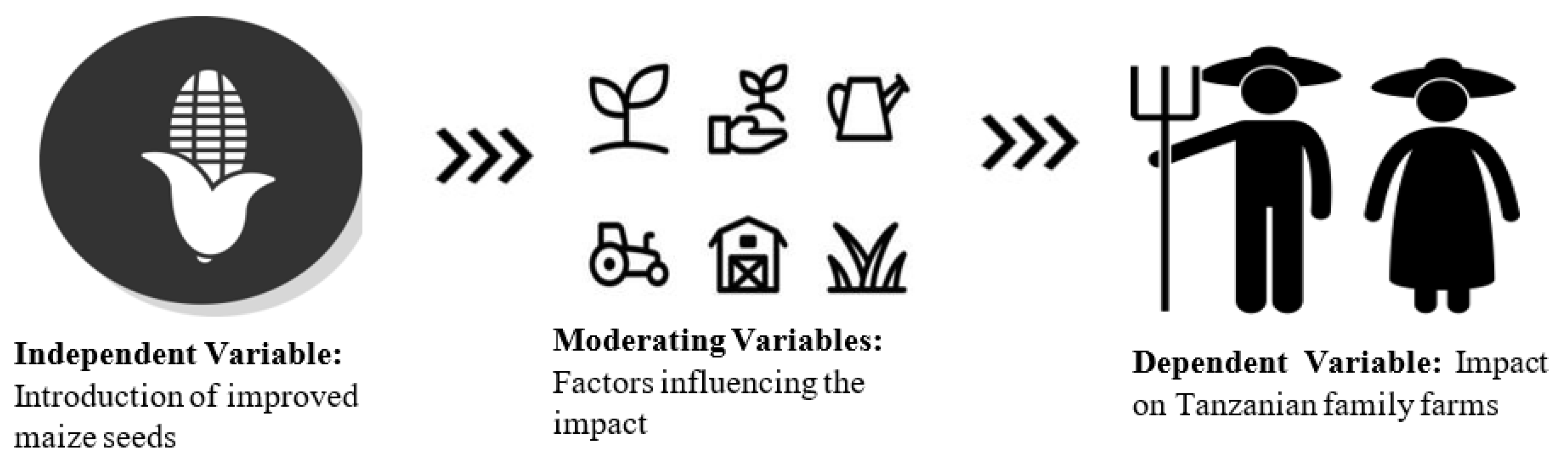

This study delves into the influence of improved maize seeds on Tanzanian family farms. These seeds, often hybrids, hold the potential for increased crop yields, disease resistance, and various other advantages. The diffusion of innovation theory provides a framework to understand how adopting these improved seeds unfolds among Tanzanian farmers (

Figure 1). This theory considers factors that influence the spread of new ideas and technologies. It is conceptualized that the introduction of improved maize seeds with specific characteristics tailored to Tanzanian conditions is the independent variable. These could include drought-resistant varieties for arid regions or high-yielding hybrids for areas with better water availability. The impact on Tanzanian family farms is the dependent variable. This encompasses a range of potential outcomes. On the other hand, it is conceptualized that the impact is being mediated by several factors that can moderate the impact of improved seeds on Tanzanian family farms.

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Study Area

This study included all regions of Tanzania, and to capture the yield variabilities, the study categorized Tanzania into seven major agro-ecological zones, namely: Northern Highlands Zone (NHZ), Eastern, Coastal Zone (ECZ), Central Zone (CZ), Southern Highlands Zone (SHZ), Lake Zone (LZ), Plateau zone (PL) as shown in

Figure 2. NHZ included three regions, namely, Arusha, Kilimanjaro, and Manyara. ECZ included six regions: Morogoro, Dar es Salaam, Pwani (Coastal Region), Lindi, Mtwara, Zanzibar, and Tanga regions, with SZ having Lindi and Mtwara regions. Central Zone comprises Dodoma and Singida regions, while SHZ comprises Iringa, Mbeya, Songwe, Njombe, and Ruvuma regions. LZ encompasses Geita, Shinyanga, Simiyu, Mwanza, Mara, and Kagera regions, and PL takes Katavi, Kigoma, Tabora, and Rukwa. The agroecological zones used in this study are summarized in

Table 1.

3.2. Data

3.2.1. National Maize Production and Yield Data

This study utilized data from the Tanzania National Panel Survey Wave 5 (NPS-5) that was collected from December 2020 to January 2022. The NPS is a nationally representative longitudinal survey designed to provide data from the same households over time in an attempt to better track national and international development indicators, understand poverty dynamics, understand the linkages between smallholder agriculture and welfare, and evaluate policy impacts in the country. The main financiers of the fifth wave of the NPS included the Ministry of Finance and Planning, the European Union (EU), the World Bank / Gates Foundation, and UNICEF. The National Bureau of Statistics has implemented the NPS in collaboration with the Office of the Chief Government Statistician – Zanzibar since its inception in 2008/09.

3.2.2. Farm Survey

Data extraction from the NPS started by sorting appropriate data for simulation. Variable [

ag3a_07], which provides data on the main crop cultivated on a particular plot in the long rainy season of 2020, was picked, and only maize was selected. Variable [

hh_a01_1] was used to identify and locate the region code and where the farm is located. Variable [

ag4a_08] collected information on the type of seed used (whether improved, improved but recycled, or local). Variable [

ag4a_27], which provided data on the quantity harvested (production per farm), was also picked to provide the yield per ha. In this way, we found 441 households that used local varieties, 71 used improved but recycled varieties, and 302 used purely improved varieties, as shown in

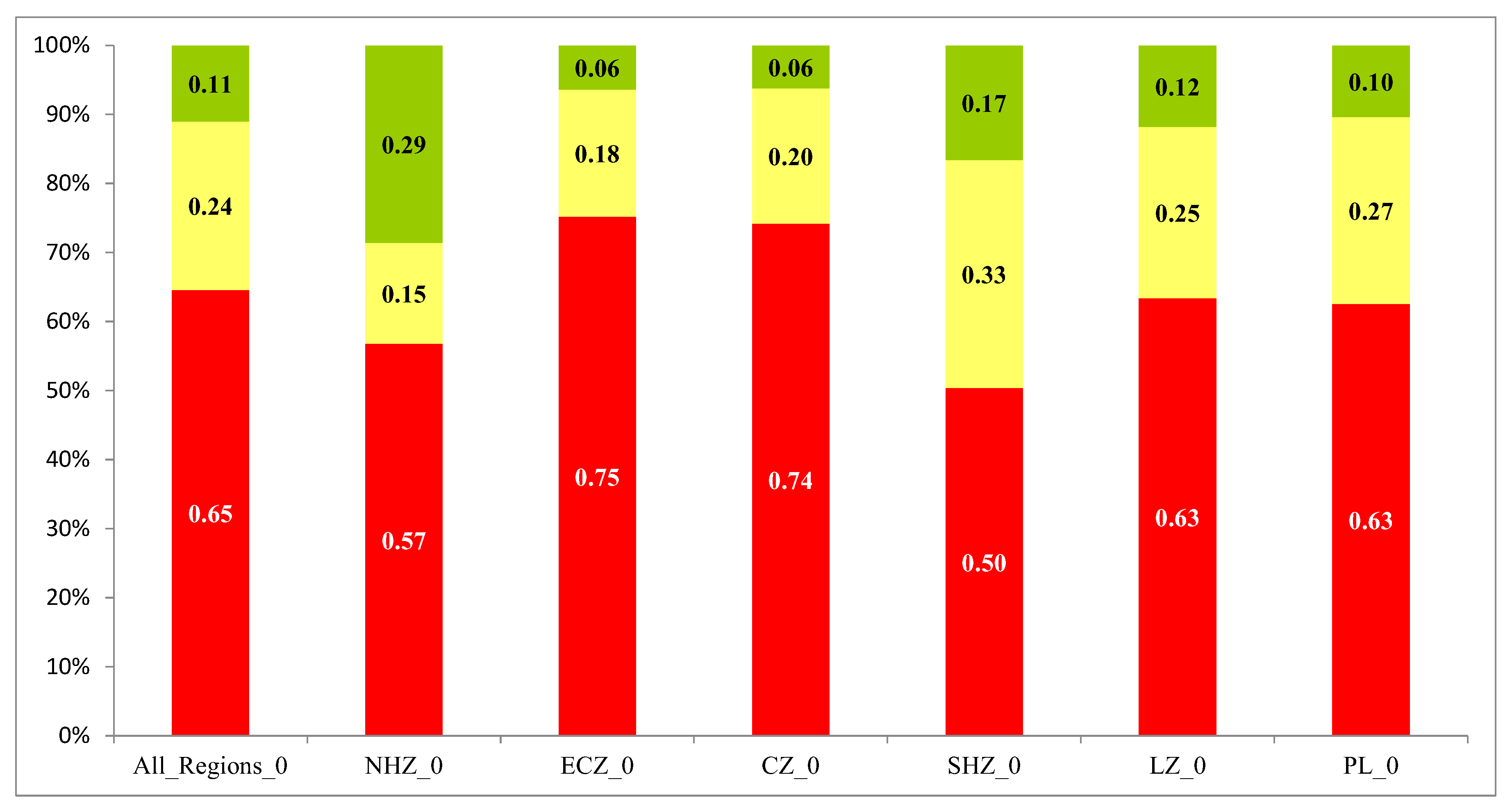

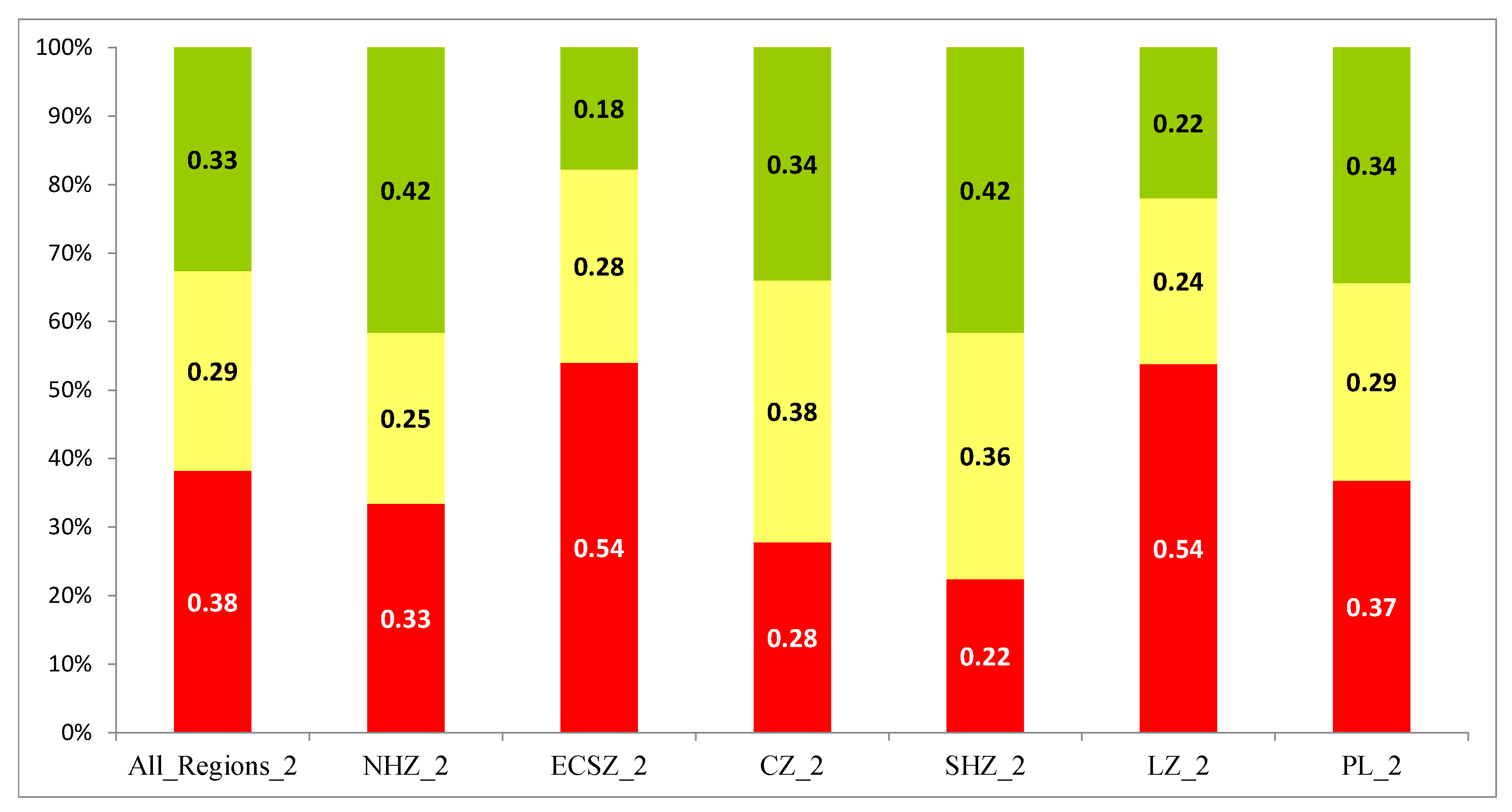

Table 2. Farms that were planted with local or traditional seeds were denoted by _0: this includes All Regions_0, NHZ_0, ECZ_0, CZ_0, SHZ_0, LZ_0, PL_0, while farmers that used improved but recycled seeds were denoted by _1: this includes All Regions_1, NHZ_1, ECSZ_1, CZ_1, SHZ_1, LZ_1, PL_1. Farmers that used improved seed varieties were denoted by _2, and it includes All Regions_2, NHZ_2, ECSZ_2, CZ_2, SHZ_2, LZ_2, PL_2.

3.2.3. A Stochastic Simulation Approach

Non-parametric Monte Carlo simulation procedures outlined by Kadigi et al. (2020a; 2020b) and Richardson et al. (2007) were used to evaluate the yield distributions for each farming system. The first step was to develop a maize seed simulation model (MaizeSim) following the Monte Carlo procedures. Since we have 441 representative farms that used local varieties, 71 improved but recycled, and 302 that used purely improved varieties across all regions, the first step was to define, parameterize, simulate, and validate the risky (stochastic) yield for each seed type. After setting the first model, we sorted the data again agroecologically to reconsider the variabilities across the agroecological zones. In this regard, this model had a total of 21 random models (three for all regions under three farming practices and 3x6 = 18 for all agroecological zones for all three farming practices).

The model was built using a multivariate empirical (MVE) distribution described by Richardson et al. (2000) and Kadigi et al. (2020c) to incorporate three farming systems (local seeds, recycled and improved seeds) and six agroecological zones. The MVE was used because of its ability to account for many variables at once. The residuals (deviations from the observed mean as percent deviations from the mean) from observed/historical yields for each yield of maize varieties were used to estimate the parameters for the MVE yield distribution. An MVE distribution is not only an appropriate tool to account for many variables at once, but also its ability to eliminate the possibility of values exceeding reasonable values like negatives in surveyed data (Ribera et al., 2004). The equation below (Eqn. 1) was used to develop the

MaizeSim model and

Table 2 defines the symbols and signs used in the model.

Table 3.

Definition of symbols used in the model.

Table 3.

Definition of symbols used in the model.

| Symbols |

Definitions |

| ~ |

A tilde represents a stochastic variable. |

| i |

Type of maize yield varieties used (Local seeds, Improved_recycled, Improved seed.

|

|

Represents agroecological zones |

| ai |

Hectares (ha) allocated for farming system i

|

|

Stochastic mean yield per ha for farming system i

|

|

Deterministic (mean) yield per ha for farming system i

|

| Sy |

Fraction deviations from the mean or sorted array of random yields for farming system i

|

| P(Sy) |

Cumulative probability function for the Sy values |

| CUSDy |

Simetar function to simulate correlated uniform standard deviates of random variables. |

| EMP() |

Simetar function used to simulate a stochastic variable (yield) |

The second step was to simulate the developed

MaizeSim model in Eq. 1 for at least 500 iterations using the Latin Hypercube (LHC) sampling procedures defined by Richardson et al. (2008). The LHC procedure ensures that a sample of only 500 iterations is necessary to reproduce the parent distributions. Since we have 21 random variables with different observations (

Table 1) for each agroecological zone and seed type, a simulation of 500 iterations for each random variable was needed to have an adequate sample to capture the differences (inherent risk) in the yields. Instead of only 814 observed yields, the model simulated 10,500 for easier comparison. The third step was to validate the simulated distribution against the historical distribution. The validation results are presented in Table 4 and Table 5, respectively.

3.2.4. Target Probabilities for Ranking Improved Seed Varieties Against Local

The Stoplight chart criteria were used to compare the target probabilities for the three maize varieties. We specify two probability targets (lower target and upper target) for the stoplight for comparison. The stoplight function calculates the probabilities of (a) exceeding the upper target (green), (b) being less than the lower target (red), and (c) observing values between the targets (yellow). Since the average yield per ha for maize in Tanzania is nearly 1 t/ha, we set our lower target to be 1 t/ha and the potential yield to be 2 t/ha (twice the lower threshold). Doubling the upper limit was in line with the desire for the government to double the yield by 2030.

| |

Unfavorable probability or the probability of falling below the lower target |

| |

Cautionary probability or the probability of falling between the lower and upper targets |

| |

Favorable probability or the probability of falling above the upper target |

4. Results and Discussion

4.1. Model Validation

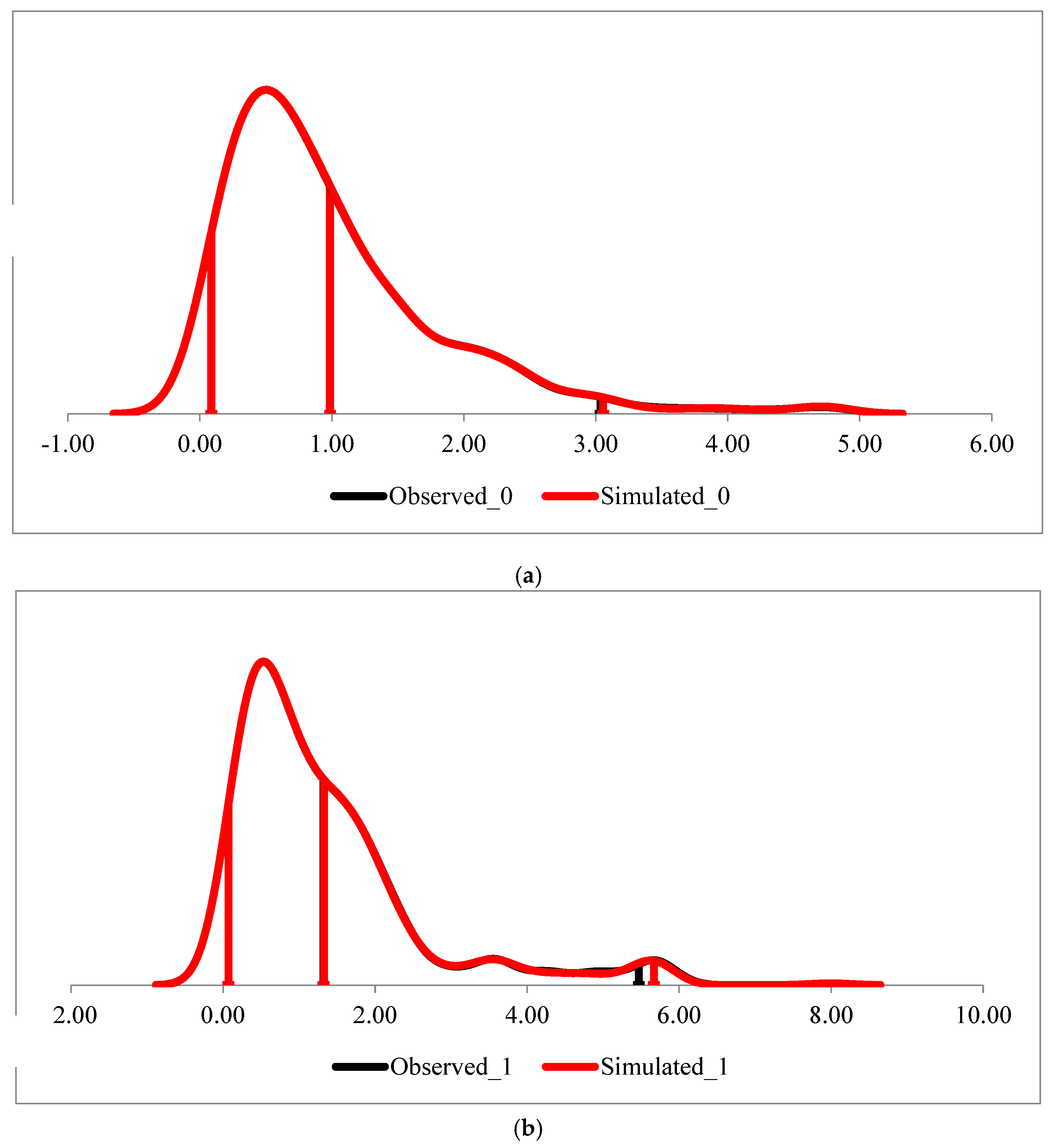

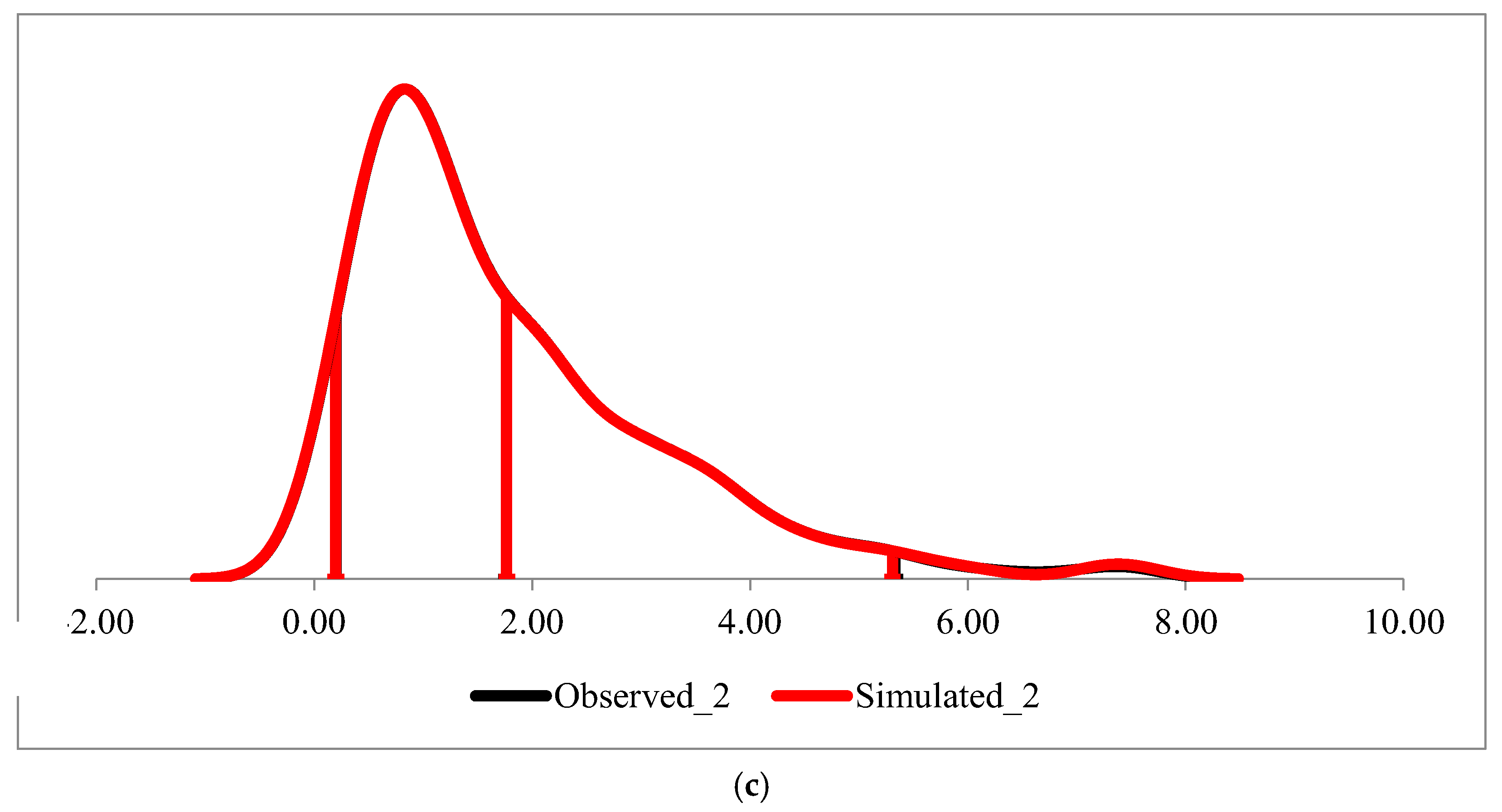

We conducted a rigorous model validation process to ensure the accuracy and reliability of our simulated random variables (specifically yield). This involved comparing the statistical properties of our simulated data to the observed or parent data. We first examined the summary statistics of both datasets, as presented in Table 4 and Table 5. By comparing measures like mean, median, standard deviation, and skewness, we verified that the simulated data accurately captured the central tendency and dispersion of the observed yield values. We employed additional statistical tests and graphical analyses to investigate the statistical relationships and distributions. The results of these tests, summarized in Table 6 and

Table 7, provided further evidence of the model’s ability to replicate the key characteristics of the observed data.

Table 4.

Observed yields (t/ha) per seed variety used (local, recycled, improved).

Table 4.

Observed yields (t/ha) per seed variety used (local, recycled, improved).

| Yield Distribution (t/ha) |

Seed variety |

| Local |

Improved_recycled |

Improved |

| Mean |

0.996 |

1.388 |

1.813 |

| STD |

0.884 |

1.536 |

1.665 |

| CV |

88.99 |

109.22 |

91.93 |

| Min |

0.010 |

0.062 |

0.092 |

| Max |

4.74 |

5.67 |

6.75 |

| Simulated Data |

441 |

71 |

302 |

Table 5.

Simulated yields (t/ha) per seed variety used (local, recycled, improved).

Table 5.

Simulated yields (t/ha) per seed variety used (local, recycled, improved).

| Yield Distribution (t/ha) |

Seed variety |

| Local |

Improved_recycled |

Improved |

| Mean |

0.997 |

1.385 |

1.815 |

| STD |

0.887 |

1.516 |

1.668 |

| CV |

88.99 |

109.22 |

91.93 |

| Min |

0.010 |

0.062 |

0.092 |

| Max |

4.76 |

5.68 |

6.74 |

| Simulated Data |

500 |

500 |

500 |

Student-t Test and Chi-Squared Statistical Tests

Student’s t-test and Chi-Squared statistical tests were used to compare the simulated data’s means and standard deviations with the observed (original means). The null and alternative hypotheses were:

Since the calculated t-statistics for all three scenarios do not exceed the critical values, we fail to reject the null hypothesis (H

0) that the means are equal, as shown in Table 6,

Table 7 and

Table 8.

Table 6.

Student-t test and Chi-Squared Statistical tests for simulated distribution vs observed local seeds yield.

Table 6.

Student-t test and Chi-Squared Statistical tests for simulated distribution vs observed local seeds yield.

| Test of Hypothesis (H0) for Parameters for all farms using Traditional maize seed (All_Regions_0) |

|---|

| Confidence level |

95.00% |

|

|

|

| |

Given Value |

Test Value |

Critical Value |

P-Value |

|

| t-Test |

1.00 |

0.03 |

2.25 |

0.98 |

Fail to Reject the H0 that the Mean is Equal to 0.997 |

| Chi-Square Test |

0.88 |

503.24 |

LB: 439.00 |

0.88 |

Fail to Reject the H0 that the Standard Deviation is Equal to 0.887 |

| |

|

|

UB:562.79 |

|

|

Table 7.

Student-t test and Chi-Squared Statistical tests for simulated distribution vs observed recycled seeds yield.

Table 7.

Student-t test and Chi-Squared Statistical tests for simulated distribution vs observed recycled seeds yield.

| Test of Hypothesis (H0) for Parameters for all farms using Recycled maize seed (All_Regions_1) |

|---|

| Confidence level |

95.00% |

|

|

|

| |

Given Value |

Test Value |

Critical Value |

P-Value |

|

| t-Test |

1.39 |

0.00 |

2.25 |

1.00 |

Fail to Reject the H0 that Mean is Equal to 1.388 |

| Chi-Square Test |

1.52 |

492.59 |

LB: 439.00 |

0.86 |

Fail to Reject the H0 that the Standard Deviation is Equal to 1.516 |

| |

|

|

UB:562.79 |

|

|

Table 8.

Student-t test and Chi-Squared Statistical tests for simulated distribution vs observed distribution of improved seeds.

Table 8.

Student-t test and Chi-Squared Statistical tests for simulated distribution vs observed distribution of improved seeds.

| Test of Hypothesis (H0) for Parameters for all farms using improved maize seed varieties (All_Regions_2) |

|---|

| Confidence level |

95.00% |

|

|

|

| |

Given Value |

Test Value |

Critical Value |

P-Value |

|

| t-Test |

1.81 |

0.02 |

2.25 |

0.98 |

Fail to Reject the H0 that Mean is Equal to 1.815 |

| Chi-Square Test |

1.662 |

502.52 |

LB: 439.00 |

0.89 |

Fail to Reject the H0 that the Standard Deviation is Equal to 1.668 |

| |

|

|

UB: 562.79 |

|

|

4.2. Yield Probabilities for Farms Using Local Maize Seeds

The summary statistics in Table 4 provide valuable insights into maize yield variations across different regions in Tanzania when using local maize seeds. The mean yield across all regions is 0.97 tons per hectare, indicating generally low productivity with significant regional variation. For instance, the Northern Highlands Zone (NHZ) has the highest mean yield of 1.44 tons/ha, while the Central Zone (CZ) exhibits the lowest at 0.71 tons/ha. The Southern Highlands Zone (SHZ) also shows a relatively high mean yield of 1.25 tons/ha, reflecting its favorable conditions for maize production. The Eastern Coastal Zone (ECZ) and Lake Zone (LZ) are moderate, with means of 0.74 and 1.05 tons/ha, respectively. These statistics underscore the importance of region-specific interventions to address the variability in maize productivity, particularly in low-yielding regions like CZ and ECZ.

The standard deviation (STD) and coefficient of variation (CV) further highlight the significant yield variability within regions. The highest variability is observed in NHZ and ECZ, with CVs of 85.5% and 90.1%, respectively, while SHZ has the lowest variability at 73.2%. This suggests that while NHZ has the highest mean yield, it also experiences considerable fluctuations, likely due to environmental factors and inconsistent input use. The minimum yields in all regions are near zero, indicating that some farms experience near-total crop failure, which could be attributed to poor weather conditions, pests, or limited access to inputs. The maximum yields range from 2.37 tons/ha in CZ to 4.74 tons/ha in NHZ and LZ, further illustrating the wide disparities in productivity. Addressing these variations through targeted policies and improved agricultural practices will be key to enhancing overall maize productivity in Tanzania.

Table 4.

Summary Statistics of yield for farms using local maize seeds.

Table 4.

Summary Statistics of yield for farms using local maize seeds.

| Statistics |

All Regions_0 |

NHZ_0 |

ECZ_0 |

CZ_0 |

SHZ_0 |

LZ_0 |

PL_0 |

| Mean |

0.97 |

1.44 |

0.74 |

0.71 |

1.25 |

1.05 |

0.97 |

| STD |

0.79 |

1.23 |

0.67 |

0.57 |

0.92 |

0.78 |

0.68 |

| CV |

80.9 |

85.5 |

90.1 |

80.0 |

73.2 |

75.0 |

70.6 |

| Min |

0.01 |

0.25 |

0.01 |

0.10 |

0.06 |

0.10 |

0.02 |

| Max |

4.74 |

4.74 |

2.97 |

2.37 |

4.45 |

4.74 |

3.76 |

Figure 2 presents the stoplight chart illustrating the yield probabilities for farms that use local maize seeds in Tanzania. The results show that a significant proportion of farmers (65%) who use local seeds have a high probability of harvesting less than 1 t/ha, which is well below the national average. Only 11% of farmers are projected to achieve yields above 2 t/ha, highlighting the limited potential of local seed varieties in boosting productivity. These findings are consistent across the agroecological zones, with the Eastern Coastal and Central Zones exhibiting the highest likelihood of poor yields. In these zones, the probability of farmers harvesting less than 1 t/ha exceeds 70%, indicating the severe challenges that smallholder farmers who rely on traditional seed varieties face (Zerssa

et al., 2021).

These results reflect broader trends observed in other studies, such as those by Gebre et al. (2021), who found that local maize varieties are more vulnerable to environmental stressors like drought and poor soil fertility. The reliance on local seeds, particularly in regions prone to climatic variability, perpetuates a cycle of low productivity and food insecurity (Zerssa et al., 2021; Gebre et al., 2021). This suggests an urgent need for intervention by introducing improved seed varieties and modern agricultural practices to enhance productivity. Without addressing these issues, farmers in Tanzania’s most vulnerable zones will continue to struggle with insufficient yields to meet subsistence and market needs.

4.3. Yield Probabilities for Farms Using Improved but Recycled Maize Seeds

Table 5 presents the summary statistics for maize yield using recycled seeds across different regions in Tanzania, offering insights into how recycled seeds impact productivity. The overall mean yield across all regions using recycled seeds is 1.22 tons per hectare, which is an improvement over the 0.97 tons/ha observed with local seeds (as shown in Table 4). The Central Zone shows the highest mean yield at 1.84 tons/ha, significantly surpassing all other regions, while the Eastern Coastal Zone has the lowest mean yield at 1.06 tons/ha. This suggests that recycled seeds are more effective in regions like the CZ, potentially due to better management practices or environmental conditions that favor seed reuse. On the other hand, the ECZ’s poor performance with recycled seeds highlights the need for interventions to improve seed quality and farming techniques in this region.

The CV reflects the variability in yields, with ECZ having the highest variation at 105.6%, indicating considerable yield inconsistencies across farms using recycled seeds. In contrast, the Southern Highlands Zone and Lake Zone exhibit relatively lower CVs of 64.2% and 61.6%, respectively, suggesting more stable yields in these regions. The standard deviation (STD) shows similar patterns, with higher yield fluctuations in CZ (1.69) and ECZ (1.11). The maximum yields achieved in ECZ and CZ are quite high, at 5.67 tons/ha and 4.94 tons/ha, respectively, demonstrating that some farms are achieving excellent productivity levels. However, the wide gap between minimum and maximum values across regions also highlights disparities in farming practices and inputs. These variations underscore the need for tailored regional strategies to improve the consistency of maize yields when using recycled seeds.

Table 5.

Summary Statistics of yield for farms using recycled maize seeds.

Table 5.

Summary Statistics of yield for farms using recycled maize seeds.

| Statistics |

All Regions_1 |

NHZ_1 |

ECZ_1 |

CZ_1 |

SHZ_1 |

LZ_1 |

PL_1 |

| Mean |

1.22 |

1.18 |

1.06 |

1.84 |

1.33 |

1.08 |

1.44 |

| STD |

1.02 |

0.97 |

1.11 |

1.69 |

0.85 |

0.67 |

1.37 |

| CV |

83.6 |

81.9 |

105.6 |

92.1 |

64.2 |

61.6 |

95.1 |

| Min |

0.06 |

0.06 |

0.08 |

0.29 |

0.16 |

0.07 |

0.15 |

| Max |

5.67 |

2.97 |

5.67 |

4.94 |

3.56 |

2.47 |

5.05 |

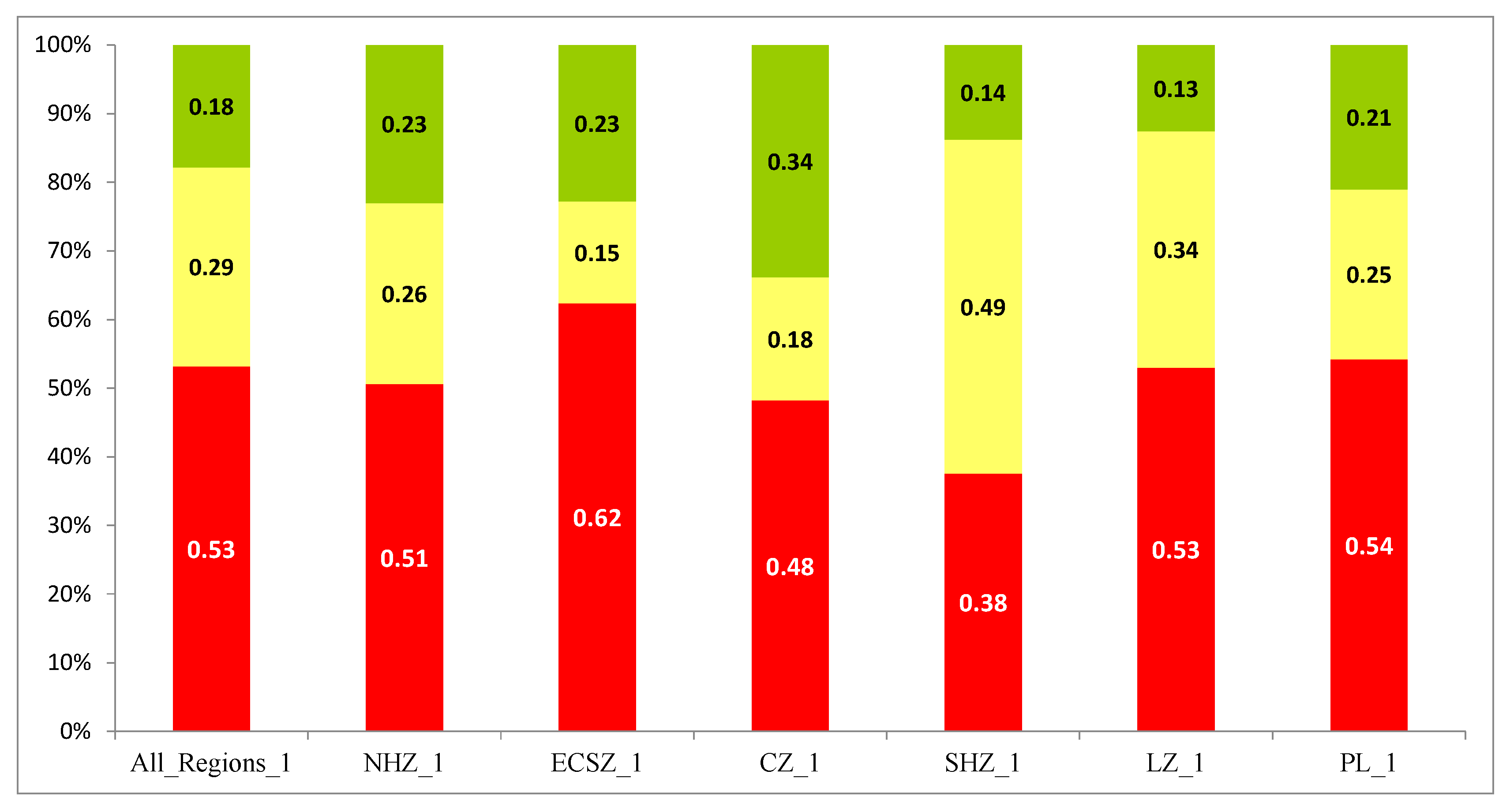

Figure 3 demonstrates the yield probabilities for farms using improved but recycled maize seeds. The data reveal that the probability of harvesting below the 1 t/ha threshold decreases to 53% for these farmers, compared to 65% for those using local seeds. Additionally, 18% of farmers using improved but recycled seeds have a chance of achieving yields above 2 t/ha. This slight improvement suggests that even though the seeds have been recycled, they still provide better outcomes than local varieties. However, the fact that more than half of the farmers remain below the 1 t/ha mark underscores that recycling seeds reduces the effectiveness of improved varieties.

The results are particularly telling for regions such as the Southern Highlands Zone and Central Zone, where using recycled seeds has led to moderate yield improvements. These findings align with research by Kihara et al. (2021), which highlights that the full potential of improved seeds is often diminished when seeds are reused for multiple planting seasons. Seed recycling contributes to genetic degradation, thereby reducing the seeds’ resilience and yield potential (AGRA – SSTP, 2016). Therefore, although farmers can experience some gains with recycled seeds, the practice of consistently reusing seeds limits the long-term benefits of improved maize varieties.

Figure 3.

Stoplight chart for yield probabilities being less than 1 t/ha and greater than 2 t/ha for the farms that used improved but recycled maize seeds per gro-ecological zone.

Figure 3.

Stoplight chart for yield probabilities being less than 1 t/ha and greater than 2 t/ha for the farms that used improved but recycled maize seeds per gro-ecological zone.

4.4. Yield Probabilities for Farms Using Purely Improved Maize Seeds

Table 6 provides summary statistics for farms using purely improved maize seeds. The provided statistics offer insights into farm yield results using improved maize seeds across various regions. The mean yields indicate a range from 1.34 in the Eastern Central Zone to a high of 2.36 in the Southern Highlands Zone (SHZ_2), illustrating significant regional variations in agricultural productivity with these seeds. The Southern Highlands Zone’s higher yield suggests optimal farming conditions or practices that favor improved seed varieties. Conversely, the Eastern Central Zone reports the lowest mean yield, which might indicate less favorable conditions or challenges in leveraging improved seed benefits. The average yield across all regions stands at 1.71, with a standard deviation of 1.28, indicating moderate overall variability in yield outcomes.

Table 6.

Summary Statistics of yield for farms using improved maize seeds.

Table 6.

Summary Statistics of yield for farms using improved maize seeds.

| Statistics |

All Regions_2 |

NHZ_2 |

ECZ_2 |

CZ_2 |

SHZ_2 |

LZ_2 |

PL_2 |

| Mean |

1.71 |

1.95 |

1.34 |

1.79 |

2.36 |

1.32 |

1.65 |

| STD |

1.28 |

1.39 |

1.33 |

1.11 |

1.70 |

0.96 |

1.21 |

| CV |

74.9 |

71.3 |

99.7 |

61.9 |

72.0 |

72.6 |

73.4 |

| Min |

0.09 |

0.15 |

0.09 |

0.74 |

0.12 |

0.20 |

0.25 |

| Max |

6.74 |

5.19 |

5.93 |

5.34 |

6.74 |

3.95 |

5.93 |

The variability in yields is further detailed by the CV percentages, which are notably high across the regions, especially in the ECZ at 99.7%, indicating a wide spread of data around the mean, thus higher risk and unpredictability in yield. The minimum and maximum yield values highlight the disparities within regions; for example, SHZ has a range from 0.12 to 6.74, showing a vast difference between the lowest and highest yields, possibly due to micro-climatic and soil differences or varied management practices. Such statistics are crucial for understanding regional performance and could guide targeted interventions to enhance maize production efficiency using improved seeds in underperforming areas.

Figure 4 illustrates the yield probabilities for farms using purely improved maize seeds. The results show a substantial improvement in maize productivity, with only 38% of farmers likely to harvest below 1 t/ha and 33% having the potential to exceed 2 t/ha. This indicates that farmers who adopt improved maize seeds are three times more likely to achieve yields above the national average compared to those using local seeds. Furthermore, across all agroecological zones, improved seeds consistently demonstrate higher productivity, with the Northern Highlands Zone, Southern Highlands Zone, and Central Zone showing the most favorable outcomes.

The positive impact of improved seeds is corroborated by studies such as those by Gebre et al. (2021), which highlight the role of improved seed varieties in enhancing resilience to environmental stressors and increasing crop yields. These results support the argument that improved seeds are a critical tool for addressing the productivity gap in Tanzania’s maize sector (Cairns et al., 2021; Rweyemamu et al., 2024). However, the success of improved seeds is also influenced by factors such as access to proper agronomic practices and inputs like fertilizers, as emphasized by Nguyen et al. (2024). Thus, while improved seeds offer substantial benefits, their full potential can only be realized through complementary interventions that address the broader agricultural ecosystem.

5. Conclusions

This study has demonstrated the significant impact of improved maize seeds on productivity across Tanzania’s diverse agroecological zones. Maize was considered in this study because it is the staple food for most Tanzanians and a strategic/priority crop. The study found that farmers who adopted improved seed varieties had a much higher probability of achieving yields above the national average compared to those using local or recycled seeds. The stochastic simulation approach (MaizeSim) provided a robust analysis, accounting for the inherent variability in yield outcomes, and underscored the potential of improved seeds to enhance food security and income generation for Tanzanian smallholder farmers. However, the results also revealed substantial regional disparities in the benefits of improved seed adoption. While zones such as the Southern Highlands, Northern Highlands, and Central Zones experienced significant yield increases, areas like the Eastern Coastal and Southern zones saw more modest gains. These regional variations highlight the importance of tailoring agricultural interventions to specific environmental and agroecological conditions to maximize their effectiveness. Without addressing these regional challenges, the broader potential of improved seeds in boosting productivity across the country will remain unrealized.

Ultimately, this study emphasizes the critical role of improved maize seeds in closing the productivity gap and enhancing the resilience of Tanzania’s maize sector. However, adoption alone is not sufficient. Complementary support, including improved access to agricultural inputs, extension services, and infrastructure, is vital to ensuring that smallholder farmers can fully realize the benefits of these improved varieties. As Tanzania continues to implement the Seed Sector Development Strategy 2030, these findings provide an essential evidence base for guiding future investments in the sector. Based on the findings of this study, it is recommended that policymakers and stakeholders invest in region-specific interventions to maximize the impact of improved maize seeds. This includes increasing support for agricultural extension services that provide farmers with training on best agronomic practices, improving access to fertilizers and irrigation systems, and fostering public-private partnerships to enhance seed distribution. Additionally, further research should be conducted to assess the long-term sustainability of improved seed adoption and its integration into broader agricultural value chains, ensuring that the benefits of increased productivity are equitably distributed across all regions of Tanzania.

Author Contributions

Ibrahim L. Kadigi: Conceptualization, Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Data Analysis – model validation, Visualization. Eliaza Mkuna: Conceptualization, Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft. Stefan Sieber: Writing – review & editing, Conceptualization.

Funding

This research was conducted as part of the USAID SERA BORA Project, contributing to the development of the Tanzania Seed Sector Development Strategy (TSSDS), which aims to enhance agricultural productivity and improve food security in Tanzania by 2030. We are grateful to ASPIRES Tanzania, supported by the USAID SERA BORA Project, under the supervision of Prof. David Nyange, for providing partial funding for this work. Special thanks go to the Simetar© team (

www.simetar.com), particularly Dr. James W. Richardson, former Regents Professor at Texas A&M University, for his continuous support and invaluable guidance on the Monte Carlo Simulation and Risk Analysis Procedures.

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

References

- AGRA – SSTP (2016). Tanzania Early Generation Seed Study. https://agrilinks.org/sites/default/files/resource/files/tanzania_early_generation_seed_report.pdf. Accessed on 04/08/2024.

- Amede, T., Konde, A. A., Muhinda, J. J., & Bigirwa, G. (2023). Sustainable farming in practice: Building resilient and profitable smallholder agricultural systems in sub-Saharan Africa. Sustainability, 15(7), 5731. [CrossRef]

- Apata, T. G., N’Guessan, Y. G., Ayantoye, K., Borokini, A., Okanlawon, M., Bamigboye, O., ... & Busari, A. O. (2020). Doggedness of small farms and productivity among smallholder farmers in Nigeria: Empirical linkage and policy implications for poverty reduction. Business Strategy & Development, 3(1), 128-142. [CrossRef]

- Bosc, P. M., Sourisseau, J. M., Bonnal, V., Gasselin, P., Valette, E., & Bélières, J. F. (2018). Diversity of family farming around the World. Existence, transformations and possible futures of family farms. Springer.

- Bryceson, D. F. (2018). A Century of Food Supply in Dar Es Salaam: From Sumptuous Suppers for the Sultan to Maize Meal for a Million 1. In Feeding African Cities (pp. 155-202). Routledge.

- Cairns, J. E., Chamberlin, J., Rutsaert, P., Voss, R. C., Ndhlela, T., & Magorokosho, C. (2021). Challenges for sustainable maize production of smallholder farmers in sub-Saharan Africa. Journal of Cereal Science, 101, 103274. [CrossRef]

- Chao, K. (2024). Family farming in climate change: Strategies for resilient and sustainable food systems. Heliyon, 10(7). [CrossRef]

- Francis, D. G. (2023). Family agriculture: tradition and transformation (Vol. 9). Taylor & Francis.

- Galani, Y. J. H., Orfila, C., & Gong, Y. Y. (2022). A review of micronutrient deficiencies and analysis of maize contribution to nutrient requirements of women and children in Eastern and Southern Africa. Critical Reviews in Food Science and Nutrition, 62(6), 1568-1591. [CrossRef]

- Gebre, G. G., Mawia, H., Makumbi, D., & Rahut, D. B. (2021). The impact of adopting stress-tolerant maize on maize yield, maize income, and food security in Tanzania. Food and Energy Security, 10(4), e313.

- Giller, K.E., Delaune, T., Silva, J.V., van Wijk, M., Hammond, J., Descheemaeker, K., van de Ven, G., Schut, A.G., Taulya, G., Chikowo, R. and Andersson, J.A. (2021). Small farms and development in sub-Saharan Africa: Farming for food, for income or for lack of better options? Food Security, 13(6), 1431-1454. [CrossRef]

- Kadigi, I. L., Mutabazi, K. D., Philip, D., Richardson, J. W., Bizimana, J. C., Mbungu, W., ... & Sieber, S. (2020a). An economic comparison between alternative rice farming systems in tanzania using a monte carlo simulation approach. Sustainability, 12(16), 6528. [CrossRef]

- Kadigi, I. L., Richardson, J. W., Mutabazi, K. D., Philip, D., Mourice, S. K., Mbungu, W., ... & Sieber, S. (2020b). The effect of nitrogen-fertilizer and optimal plant population on the profitability of maize plots in the Wami River sub-basin, Tanzania: A bio-economic simulation approach. Agricultural systems, 185, 102948. [CrossRef]

- Kadigi, I. L., Richardson, J. W., Mutabazi, K. D., Philip, D., Mourice, S. K., Mbungu, W., ... & Sieber, S. (2020c). The effect of nitrogen-fertilizer and optimal plant population on the profitability of maize plots in the Wami River sub-basin, Tanzania: A bio-economic simulation approach. Agricultural systems, 185, 102948. [CrossRef]

- Khumalo, T. F. (2021). Social issues related to climate change and food production (crops). In The Impacts of Climate Change (pp. 291-311). Elsevier.

- Kihara, J., Kizito, F., Jumbo, M., Kinyua, M., & Bekunda, M. (2021). Unlocking maize crop productivity through improved management practices in northern Tanzania. African Journal of Food, Agriculture, Nutrition and Development, 20(7), 17095-17112.

- Langyintuo, A. (2020). Smallholder farmers’ access to inputs and finance in Africa. The role of smallholder farms in food and nutrition security, 133-152.

- Menkir, A., Dieng, I., Meseka, S., Bossey, B., Mengesha, W., Muhyideen, O., Riberio, P.F., Coulibaly, M., Yacoubou, A.M., Bankole, F.A. and Adu, G.B. (2022). Estimating genetic gains for tolerance to stress combinations in tropical maize hybrids. Frontiers in Genetics, 13, 1023318. [CrossRef]

- Minde, I. J., Silim, S. N., Nyange, D. A., Ijumba, C. K., Kadigi, I., & Ires, I. (2024). Tanzania Seed Sector Development Strategy: inception report.

- Mugula, J. J., Ahmad, A. K., Msinde, J., & Kadigi, M. (2023). Impacts of Sustainable Agricultural Practices on Food Security, Nutrition, and Poverty among Smallholder Maize Farmers in Morogoro region, Tanzania. African Journal of Empirical Research, 4(2), 1091-1104. [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, T.D., Venkatadri, U., Nguyen-Quang, T., Diallo, C., Pham, D.H., Phan, H.T., Pham, L.K., Nguyen, P.C. and Adams, M. (2024). Stochastic Modelling Frameworks for Dragon Fruit Supply Chains in Vietnam under Uncertain Factors. Sustainability, 16(6), 2423. [CrossRef]

- Nyaligwa, L., Hussein, S., Laing, M., Ghebrehiwot, H., & Amelework, B. A. (2017). Key maize production constraints and farmers’ preferred traits in the mid-altitude maize agroecologies of northern Tanzania. South African Journal of Plant and Soil, 34(1), 47-53. [CrossRef]

- Ojara, M. A., Yunsheng, L., Babaousmail, H., Sempa, A. K., Ayugi, B., & Ogwang, B. A. (2022). Evaluation of drought, wet events, and climate variability impacts on maize crop yields in East Africa during 1981–2017. International Journal of Plant Production, 16(1), 41-62.

- Quarshie, P. T., Abdulai, A. R., & Fraser, E. D. (2021). Africa’s “seed” revolution and value chain constraints to early generation seeds commercialization and adoption in Ghana. Frontiers in Sustainable Food Systems, 5, 665297. [CrossRef]

- Quendler, E., Ikerd, J., & Driouech, N. (2020). Family farming between its past and potential future with the focus on multifunctionality and sustainability. CABI Reviews, (2020). [CrossRef]

- Ribera, L. A., Hons, F. M., & Richardson, J. W. (2004). An economic comparison between conventional and no-tillage farming systems in Burleson County, Texas. Agronomy Journal, 96(2), 415-424.

- Richardson, J. W., Klose, S. L., & Gray, A. W. (2000). An applied procedure for estimating and simulating multivariate empirical (MVE) probability distributions in farm-level risk assessment and policy analysis. Journal of Agricultural and Applied Economics, 32(2), 299-315. [CrossRef]

- Richardson, J. W., Herbst, B. K., Outlaw, J. L., & Gill, R. C. (2007). Including risk in economic feasibility analyses: the case of ethanol production in Texas. Journal of Agribusiness, 25(2), 115-132.

- Rweyemamu, M. R., Mruma, T., & Nkanyani, S. (2024). Stakeholders Inception Meeting: Tanzania Seed Sector Development Strategy (TSSDS).

- Said, M., & Temba, A. (2023). The economic viability analysis on the Adopted Climate Change Adaptation Strategies among Maize Farmers in semi-arid of central Tanzania. East African Journal of Science, Technology and Innovation, 4. [CrossRef]

- Shabani, Y., & Pauline, N. M. (2023). Perceived effective adaptation strategies against climate change impacts: Perspectives of maize growers in the southern highlands of Tanzania. Environmental Management, 71(1), 179-189. [CrossRef]

- Veste, M., Sheppard, J. P., Abdulai, I., Ayisi, K. K., Borrass, L., Chirwa, P. W., ... & Kahle, H. P. (2024). The Need for Sustainable Agricultural Land-Use Systems: Benefits from Integrated Agroforestry Systems. In Sustainability of Southern African Ecosystems under Global Change: Science for Management and Policy Interventions (pp. 587-623). Cham: Springer International Publishing.

- Wahab, I., Jirström, M., & Hall, O. (2020). An integrated approach to unravelling smallholder yield levels: The case of small family farms, Eastern Region, Ghana. Agriculture, 10(6), 206. [CrossRef]

- Were, M. A. (2021). A Critical Analysis of Food Security and Policy in Eastern Africa: the Case Study of the Maize Sub-sector in Kenya (Doctoral dissertation, University of Nairobi).

- Xiong, W., & Tarnavsky, E. (2020). Better agronomic management increases climate resilience of maize to drought in Tanzania. Atmosphere, 11(9), 982. [CrossRef]

- Yusuph, A. S., Nzunda, E. F., Mourice, S. K., & Dalgaard, T. (2023). Usage of Agroecological Climate-Smart Agriculture Practices among Sorghum and Maize Smallholder Farmers in Semi-Arid Areas in Tanzania. East African Journal of Agriculture and Biotechnology, 6(1), 378-405. [CrossRef]

- Zerssa, G., Feyssa, D., Kim, D. G., & Eichler-Löbermann, B. (2021). Challenges of smallholder farming in Ethiopia and opportunities by adopting climate-smart agriculture. Agriculture, 11(3), 192. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).