1. Introduction

Player availability, defined as keeping players injury-free and ready to participate in competition, is extremely important in the current elite team sport scenarios, because it is related to team performance [

1], has been demonstrated to have a close relationship with the number of goals scored [

2], and points obtained throughout the season [

3], thus determining ranking position [

4]. Therefore, injury prevention strategies and their management becomes a cornerstone towards the achievement of these outcomes [

5,

6]. However, despite of the overall injury rate shows a downward trend, muscle injury rate has not decreased and neither has its injury burden [

7]. Hamstring strain injury (HSI) is considered as the most frequent muscle injury in professional football, accounting for about 40% of muscle injuries [

8,

9,

10] and between 12% and 19% of the total injuries [

8,

9,

10,

11,

12] showing an injury incidence approximately 10 times higher in matches than in training (4.99/1000 h

Vs. 0.52/1000 h, respectively) [

11].

The hamstring muscle group is composed of the muscles located in the posterior and medial area of the thigh, which are the semimembranosus (SM), semitendinosus (ST), and the biceps femoris (BF) on the lateral side, both its long (BFlh) and short (BFsh) heads [

13,

14]. Hamstrings are involved in a large number of athletic movements (e.g., running, jumping, deceleration, landing and shooting), so its function is essential in the physical performance of football, especially when high-speed running is required [

15,

16,

17]. Therefore, it is not surprising that most studies concluded that HSIs occur during this type of action [

16,

18,

19,

20,

21,

22,

23,

24,

25,

26,

27,

28,

29].

Regarding the hamstring injury mechanisms, Askling et al. [

21,

30] proposed two specific types of injury (stretch-type and sprint-type), however, it is not common to find detailed descriptions in the scientific literature about injury events in professional football players. Recently, two studies [

28,

31] have implemented video analysis to more thoroughly define the HSIs in men’s professional football. The use of this methodology allows understanding and expanding information about different injury mechanisms (e.g., hamstring, adductor and anterior cruciate ligament), as well as providing information about how the injury occurs in a real game context [

28,

31,

32,

33,

34,

35,

36]. The two studies cited above [

28,

31] categorized the hamstring injury mechanisms, defining different subtypes within the patterns related to sprinting (acceleration, high-speed running, deceleration and high-speed curved running) and related to stretching (open chain and closed chain).

However, Jokela et al. [

31] presented the importance of including mixed patterns (associating the sprint-pattern with the stretch-pattern) since their neuromuscular characteristics are different. In addition, the high neurocognitive and motor control demands implicit in football as mechanisms that could be harmful and that appear recurrently in football players: external focus of attention, unexpected disturbances, etc. should be considered [

37,

38,

39]. Therefore, the main aim of this study was to describe the mechanisms and contextual patterns related to HSIs of professional male football players in competition, using systematic video analysis.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

This descriptive observational cross-sectional study included all male football players of the Spanish First Division (LaLiga

TM) of the 2017/18 and 2018/19 seasons who played at least one official competition match as inclusion criteria. Personal data (name, date of birth, club and playing position) of the participants were provided by LaLiga

TM (LFP) through the Mediacoach® application (Official data provider of LFP, from open access websites such as

https://www.transfermarkt.es (Transfermarkt, Hamburg, Germany), and if necessary, by performing an additional Google® search following a methodology similar to the one used by Gronwald et al. [

28] and Klein et al [

35].

2.1.1. Ethical Considerations

All data used in this study were treated confidentially, and players’ personal information was obtained through publicly available websites, such as

https://www.transfermarkt.es (Transfermarkt, Hamburg, Germany), so ethical clearance was not required [

33,

40].

2.2. Procedures

2.2.1. Video Acquisition and Processing

Before starting to analyze the observability of injuries, with data obtained mainly through

https://www.transfermarkt.es, (Transfermarkt, Hamburg, Germany) all muscle injuries from the 2017/18 and 2018/19 seasons of LFP were entered into a Microsoft® Excel table. Once all injuries were added, those that met the following criteria were included for analysis: HSIs, that happened in official LFP matches (i.e., excluding training, Copa del Rey, Champions League, etc.) or that some information about the injury could be found. Subsequently, a more thorough screening was carried out, looking at each recording to see if the moment of injury was observable or not through the Mediacoach

® platform. After this screening, the most exhaustive analysis was performed with the remaining injuries, cutting complete fragments from the previous play until the injury occurred, reviewing as many times as necessary (different angles and slow motion) from the different cameras available (television and tactical camera).

2.2.2. Determination of the Moment of Injury

The moment of injury was assumed to occur when the player clearly showed some gesture of discomfort or inability to continue in the game (e.g., if the player started to limp or put his hand on the back of his thigh immediately after the observed action). This process was carried out by two operators (A.G.-M. and A.M.-S.), and was performed by testing with smaller samples (first with 25 cases and then with 40) to ensure that the two observers agreed on the time of injury. If the observers did not agree with any of the cases, the injury was rechecked to reach an agreement with the help of a third author (A.Z.-Z.). All those cases in which no consensus was reached were excluded from the final analysis.

2.3. Video Analysis

To perform the analysis of the videos, an

ad hoc tool was first created for the observation of HSIs in football players. This tool has a system of field formats that is structured in eight criteria, which, in turn, are composed of several categories following the principles of exhaustiveness and mutual exclusivity (EME) [

41]. To develop the different criteria and categories of this tool, previous studies with similar objectives were used as a reference [

28,

35]. To assess the reliability of the tool, inter- and intra-observer reliability analyses were performed [

42,

43] using IBM SPSS

® V26 and obtaining high levels of reproducibility: Cohen’s Kappa >0.87 and p<0.05 in all cases. For more information about the different criteria and categories used for the analysis of the videos consult the Table S1, in the supplementary data.

Once the observation tool was defined, the evaluation of the specific injury patterns of the hamstring muscle group by the main author of the study (A.G.-M.) began. With each injury, data were collected on contextual factors (equipment, specific position, moment...) and injury characteristics (contact, pattern, trajectory, technical action...). Periodically (each 2 weeks), a meeting was held with two of the co-authors (A.G.-M. and A.Z.-Z.) to discuss the collected data and reach an agreement. All these data were annotated in a Microsoft Excel® sheet and, subsequently, descriptive statistics were performed in it.

3. Results

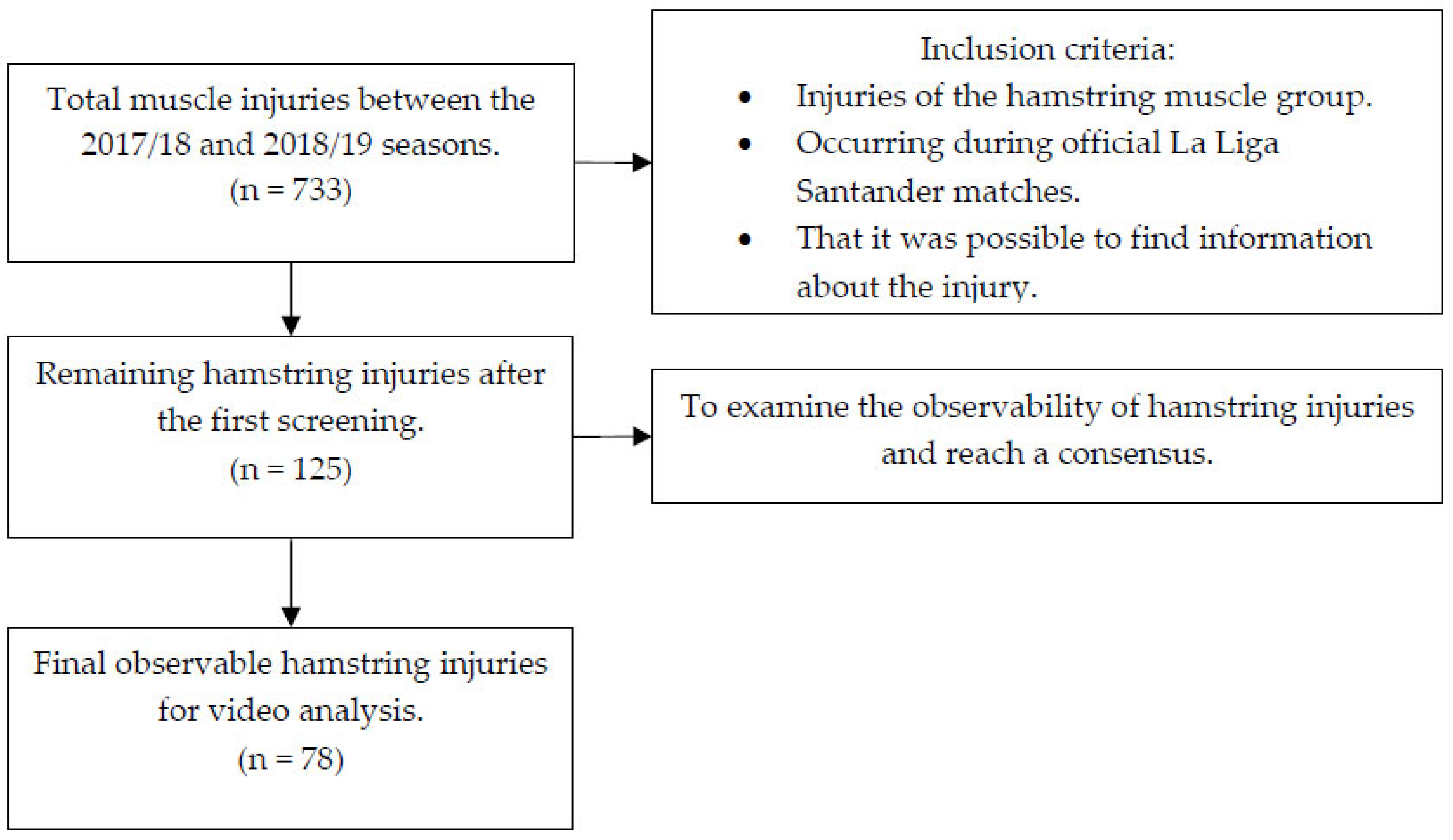

Between the 2017/18 and 2018/19 seasons, a total of 733 muscle injuries were reported. After considering the first inclusion criteria, the number was reduced to 125 hamstring injuries. Among these cases, the number of videos for the final analysis was 78 observable injuries (Error! Reference source not found.).

Figure 1.

Flow chart describing the acquisition and screening process.

Figure 1.

Flow chart describing the acquisition and screening process.

3.1. Subjects

A total of 78 hamstring injuries from 62 professional football players (mean age: 28 ± 3.91 years) were included.

3.2. General Descriptive Data of the Injuries

3.2.1. Contextualization

Contact. Eighty-three percent of the injuries (65 cases) were non-contact injuries, with the remaining injuries being contact injuries (17%; 13 cases).

Specific position. The positions that suffered the most from HSIs were especially three, fullbacks/wingbacks (28%; 22 cases), central defenders (27%; 21 cases), and wide midfielders or wingers (23%; 18 cases). The next most numerous cases were central midfielders (10%; 8 cases) and strikers (9%; 7 cases). Finally, there were only two isolated cases of goalkeepers (1%; 1 case) and second strikers (1%; 1 case).

Ball. In 69 cases (88%) the presence of the ball was relevant at the time of injury, while in only 9 cases (12%) it was not.

Time of injury. The time at which injuries occurred during the match was evenly distributed, although it could be said that the block of the middle of the first half (between minutes 16-30, 23%; 18 cases) and second half (between minutes 61-75, 21%; 16 cases) are slightly above the rest. This is followed by the beginning of the second part (18%; 14 cases) and the end of the first part (17%; 13 cases), with smaller cases of the end of the second part (12%; 9 cases) and the beginning of the first part (10%; 8 cases).

Situation. Injuries were distributed almost equally between defensive and offensive actions, the former representing 51% of the cases (40 cases) and the latter 49% (38 cases).

3.2.2. Injury Mechanism

Injury pattern. The most prominent injury patterns were the SP-type pattern, presenting more than half of all cases (54%; 42 cases) and COMB2 (26%; 20 cases). The remaining cases were the closed chain stretch-related pattern (ST-CC) (8%; 6 cases), open chain stretch-related pattern (ST-OC) (6%, 5 cases), and the combined pattern 1 (COMB1) (6%, 5 cases).

Trajectory. Among the SP-type injury, 52% of the cases showed a curvilinear trajectory (22 cases), while 48% showed a rectilinear trajectory (20 cases).

Technical action. As for the specific technical action at the time of injury, the cases were mainly divided into three groups, the action “none/stopped” (37%; 29 cases), the “dispute” (36%; 28 cases), and the “pass” (13%; 10 cases). In a smaller percentage were found the action “control” (5%; 4 cases), the “steal” (3%; 2 cases), the “clearance” (3%; 2 cases), the “center” (3%; 2 cases), and the “drive” (1%; 1 case).

3.3. Relevant Descriptive data Within Each Injury Pattern

SP-type injury pattern (n = 42). Within this injury pattern, the most important data showed that 95% of the cases (40 cases) occurred without any type of contact, mainly in central defenders (33%; 14 cases) and fullbacks/wingbacks (26%; 11 cases), with a significant presence of the ball (79%; 33 cases), at the beginning (minutes 46-60) of the second half (29%; 12 cases), in mostly defensive situations (60%; 25 cases), and without any specific technical action (i.e., running) (60%; 25 cases) and in disputes (38%; 16 cases).

ST-OC type injury pattern (n = 5). The most relevant was that all of them occurred without contact and with the presence of the ball, in the middle part (minutes 61-75) of the second half (60%; 3 cases), mostly in offensive situations (80%; 4 cases), and in technical passing actions (60%; 3 cases). Regarding the specific position, 4 of the cases were players with a more defensive role (80%; 4 cases, 2 central defenders, 1 goalkeeper and 1 fullback).

ST-CC type injury pattern (n = 6). Again, 100% of the cases occurred with the presence of the ball, mainly during the middle part (minutes 16-30) of the first half (50%; 3 cases), in mainly offensive situations (67%; 4 cases), and in contested actions (67%; 4 cases). As for contact, the cases were equally distributed (50% without contact and 50% with contact). The position of the players, in this case, was more offensive (100%; 6 cases, 4 wide midfielders/wingers, 1 center striker and 1 central midfielder).

COMB1 type injury pattern (n = 5). Once again, the presence of the ball was relevant in all 5 cases, almost all were non-contact injuries and in defensive situations (80%; 4 cases), and throughout the middle part of the first half (60%; 3 cases). The role of these players was of a more defensive nature (80%; 4 cases, 2 central defenders and 2 fullbacks), and the specific action was distributed (2 cases of “control”, 1 of “dispute”, 1 of “none”, and 1 of “pass”).

COMB2 type injury pattern (n = 20). In this type of injury, the presence of the ball again prevailed (100% of cases), the vast majority occurred without contact (65%; 13 cases), mainly during offensive situations (60%; 12 cases), in fullbacks (40%; 8 cases), and in contested and passing actions (35%; 7 cases and 30%; 6 cases, respectively). The time of injury was distributed between the first and second half, although minutes 16-45 prevailed (50%; 10 cases). Although some trends could be observed, it should be noted that this is possibly the pattern in which there was the greatest dispersion of data.

Table 1.

General descriptive data of the contextual factors of the injuries.

Table 1.

General descriptive data of the contextual factors of the injuries.

| Contact |

No. of cases |

Percentage |

Specific Position |

No. of cases |

Percentage |

Ball |

No. of cases |

Percentage |

Time of

injury |

No. of cases |

Percentage |

Situation |

No. of cases |

Percentage |

| CI |

13 |

17% |

CD |

21 |

27% |

NO |

9 |

12% |

1 HALF-END |

13 |

17% |

DEFEN |

40 |

51% |

| NCI |

65 |

83% |

FB/WB |

22 |

28% |

YES |

69 |

88% |

1 HALF-MID |

18 |

23% |

OFFEN |

38 |

49% |

| |

|

|

STR |

7 |

9% |

|

|

|

1 HALF-BEG |

8 |

10% |

|

|

|

| |

|

|

WIN/WMF |

18 |

23% |

|

|

|

2 HALF-END |

9 |

12% |

|

|

|

| |

|

|

STR |

8 |

10% |

|

|

|

2 HALF-MID |

16 |

21% |

|

|

|

| |

|

|

SE-STR |

1 |

1% |

|

|

|

2 HALF-BEG |

14 |

18% |

|

|

|

| |

|

|

GK |

1 |

1% |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Table 2.

General descriptive data on the mechanism of injury.

Table 2.

General descriptive data on the mechanism of injury.

| Injury pattern |

No. of cases |

Percentage |

Trajectory |

No. of cases |

Percentage |

Technical action |

No. of cases |

Percentage |

| COMB1 |

5 |

6% |

CURV |

22 |

52% |

CRO |

2 |

3% |

| COMB2 |

20 |

26% |

LIN |

20 |

48% |

CON |

4 |

5% |

| SP |

42 |

54% |

|

|

|

DRI |

1 |

1% |

| ST-OC |

5 |

6% |

|

|

|

CLE |

2 |

3% |

| ST-CC |

6 |

8% |

|

|

|

DIS |

28 |

36% |

| |

|

|

|

|

|

Ø |

29 |

37% |

| |

|

|

|

|

|

PAS |

10 |

13% |

| |

|

|

|

|

|

STE |

2 |

3% |

Table 3.

Notable descriptive data of the different injury patterns.

Table 3.

Notable descriptive data of the different injury patterns.

Injury

Pattern |

Contact |

Specific Position |

Ball |

| |

CI |

NCI |

CD |

FB/WB |

STR |

WIN/WMF |

CMF |

GK |

SE-STR |

YES |

NO |

| COMB1 (n=5) |

1 (20%) |

4 (80%) |

2 (40%) |

2 (40%) |

- |

1 (20%) |

- |

- |

- |

5 (100%) |

- |

| COMB2 (n=20) |

7 (35%) |

13 (65%) |

3 (15%) |

8 (40%) |

3 (15%) |

4 (20%) |

2 (10%) |

- |

- |

20 (100%) |

- |

| SP (n=42) |

2 (5%) |

40 (95%) |

14 (33%) |

11 (26%) |

3 (7%) |

8 (19%) |

5 (12%) |

- |

1 (2%) |

33 (79%) |

9 (21%) |

| ST-OC (n=5) |

- |

5 (100%) |

2 (40%) |

1 (20%) |

- |

1 (20%) |

- |

1 (20%) |

- |

5 (100%) |

- |

| ST-CC (n=6) |

3 (50%) |

3 (50%) |

- |

- |

1 (17%) |

4 (67%) |

1 (17%) |

- |

- |

6 (100%) |

- |

| |

| Moment |

Situation |

Technical Action |

| 1 HALF END |

1 HALF MID |

1 HALF BEG |

2 HALF END |

2 HALF MID |

2 HALF BEG |

DEFEN |

OFFEN |

CRO |

CON |

DRI |

CLE |

DIS |

Ø |

PAS |

STE |

| 1 (20%) |

3 (60%) |

- |

1 (20%) |

- |

- |

4 (80%) |

1 (20%) |

- |

2 (40%) |

- |

- |

1 (20%) |

1 (20%) |

1 (20%) |

- |

| 4 (20%) |

6 (30%) |

1 (5%) |

2 (10%) |

5 (25%) |

2 (10%) |

8 (40%) |

12 (60%) |

1 (5%) |

1 (5%) |

- |

1 (5%) |

7 (35%) |

2 (10%) |

6 (30%) |

2 (10%) |

| 7 (17%) |

6 (14%) |

5 (12%) |

5 (12%) |

7 (17%) |

12 (29%) |

25 (60%) |

17 (40%) |

- |

- |

1 (2%) |

- |

16 (38%) |

25 (60%) |

- |

- |

| - |

- |

1 (20%) |

1 (20%) |

3 (60%) |

- |

1 (20%) |

4 (80%) |

- |

1 (20%) |

- |

1 (20%) |

- |

- |

3 (60%) |

- |

| 1 (17%) |

3 (50%) |

1 (17%) |

- |

1 (17%) |

- |

2 (33%) |

4 (67%) |

1 (17%) |

- |

- |

- |

4 (67%) |

1 (17%) |

- |

- |

4. Discussion

The purpose of this study was to describe in detail how hamstring strain injuries occurred in male football players of the Spanish football league, during official matches in two consecutive seasons. The most significant findings were that: 1) although the SP pattern still stands out over the others, COMB2 is also another mechanism to be taken into account, 2) within the SP-type patterns, curvilinear running can be an interesting stimulus to consider in training programs. 3) most injuries occur without contact and with the presence of the ball, and 4) the specific positions most affected are fullbacks/wingbacks, central defenders and wide midfielders/wingers.

4.1. Sprint Pattern (SP)

The scientific literature has described the hamstring injury mechanism primarily through two mechanisms of injury, the stretch type and the sprint type [

21,

30]. Many researchers agree that the sprinting or high-speed running type is, between the two, the one that occurs more frequently and generates more cases of hamstring injury [

16,

18,

19,

20,

21,

22,

23,

24,

25,

26,

27,

28,

29]. Based on several biomechanical studies analyzing the demands on the hamstring musculature during high-speed running [

44,

45], despite some discrepancies between the mechanics of the acceleration phase and maximum speed, it is considered that the most critical moments for injury are the final phase of the swing (preactivation) and the early stance phase (braking), in the first case braking the inertia produced by the lower limb and in the second the ground reaction forces [

16,

19,

22,

23,

29,

46,

47,

48,

49,

50].

Our results show that more than half of the cases (54%) occurred during pure running actions at high intensity, and, moreover, 86% of all cases (42 pure SP cases, 20 COMB2 cases, and 5 COMB1 cases) were related in some way to sprinting, as COMB1 and COMB2 patterns involve a sprinting action prior to the time of injury. Other relatively recent studies also using systematic video analysis to describe hamstring injury in soccer and rugby players show similar findings, as in all of them sprinting is the predominant mechanism of injury. Gronwald et al. [

28] showed that 25 of 52 cases (48%) occurred during sprinting, Kerin et al. [

32] noted that 8 of 17 cases (47%) were during running, Jokela et al. [31) noted that 3 of 14 cases (21%) were pure sprinting, although similar to our study, 6 cases (43%) also had a relationship with sprinting, as they were “mixed type” patterns (so in total 64% of cases were related to sprinting). Finally, the study by Aiello et al. [

51] showed that 16 of 17 cases (94%) of hamstring injury occurred while the players were running at a speed above 25 km/h, all of them at speeds above 70% of the players’ individual maximum speed. Therefore, considering these previously commented data, sprints or high-speed running should continue to be an important pillar within the rehabilitation and prevention programs for hamstring injury, since it is the action with the highest incidence of this injury.

4.2. Combined Pattern 2 (COMB2)

The findings of this study show that the second most recurrent injury pattern was COMB2, presenting 26% of all injuries observed. It is relevant to emphasize the incidence of COMB2 in hamstring injury, because although it involves a sprinting action, the mechanics and neuromuscular demands are different since the injury might not occur in the sprint as such, but when the lower extremity has to decelerate rapidly the inertia of the body, accompanied in some cases by external forces generated by an opponent. Along these lines, some recent studies in men’s football and rugby, which also used systematic video analysis [

28,

31,

32,

51] have found that braking can be an important mechanism of injury. Moreover, similarly, although in their investigation the total number of cases was smaller (n = 14), Jokela et al. [

31] found 6 injuries that they term the “mixed type” pattern, of which 4 (29%) were of the COMB2 style. For this reason, these authors also highlight the relevance of recognizing and incorporating biomechanical studies of this “mixed type” injury pattern, as its prevalence is high and does not follow the typical patterns of sprint or stretch type injuries. Of the other three studies, two [

28,

32] had a different way of categorizing injuries, mainly because they do not consider combined patterns, the results obtained in their studies differ slightly. Even so, Gronwald et al. [

28] identified that 18 cases (%35) of 52 hamstring injuries occurred in landing and stride type braking, and Kerin et al. [

32] that 3 (18%) of 17 cases were generated in sudden decelerations. Finally, Aiello et al. [

51] observed that players frequently (4 out of 17 cases; 24%) injured their hamstrings when they were decelerating from high speeds, more specifically when running on average at an intensity of 88% of their individual maximum speed. Considering these data, it could be concluded that the physical ability to be able to break the body quickly (and often with some disturbance generated by the opponent) should be a key variable to take into account in training programs for the prevention of hamstring injuries.

4.3. Curvilinear Sprints

Within pure sprinting patterns, the importance of curvilinear sprints should be noted, since in our study we observed that approximately half (52% of the cases observed) of the injuries occurred in curvilinear sprinting. It has been described that the ability to sprint in curvilinear trajectories is an important skill in football [

52,

53,

54,

55] which is used to evade, chase, or lure an opponent. Likewise, it has been observed that football players who run fast in linear sprints, do not necessarily run faster in curvilinear trajectories [

53,

54,

55]. This may be because curved sprints require the ability to generate centripetal forces, causing different mechanical and neuromuscular behaviors [

53]. For example, several studies have been able to identify that the outer and inner leg do not act in the same way, increasing the contact time and decreasing the step length and step frequency of the inner leg [

53,

54,

55]. Moreover, in terms of electromyographic activation, it appears that in the outer leg (performing a constant

side-stepping maneuver) the hip external rotators (biceps femoris and gluteus medius) are more active, while in the inner leg (performing a constant

cross-stepping maneuver) are the hip internal rotators (semitendinosus and adductors) [

55]. These could be some of the reasons why there is a “good” and a “bad” side to curved sprints.

However, there seems to be controversy among the different observational studies analyzing the sprint trajectory. In the study by Jokela et al. [

31] although the total number of pure sprint injuries was low, they saw that 1 of 3 injuries (33%) was in a curvilinear sprint. Nevertheless, Aiello et al. [

51] indicate that 88% of the injuries analyzed were in rectilinear sprints. Other research points out that approximately 85% of the maximum sprints in professional football present some degree of curvature, i.e., they are not totally linear [

53,

55]. These differences between studies may be due to the fact that the methodology used for the analysis of the trajectory of the sprints was different, details such as the total number of cameras used, their angulations, or references used to measure the degree of curvature, could be some of the reasons for these differences. Despite these differences, physical trainers and coaches of football players should implement curvilinear sprints in their training and prevention programs, in order to work on the distinctive neuromuscular mechanics and demands that they require.

4.4. Presence of Contact and Ball

Some epidemiological studies conducted in men’s football report that the vast majority of muscle injuries, and specifically hamstring injuries, occur in non-contact situations [

8,

56]. In both this present study and two other studies using video analysis system in team sports [

28,

32] a large proportion of the injuries analyzed are still non-contact (83%, 65% and 59% respectively), although in the research by Jokela et al.[

31], the number of cases decreases to 50%. This could point out that as the sample of hamstring injuries increases, so does the number of cases of non-contact injuries. However, both in our case and in the study by Gronwald et al. [

28], contact injuries increase in patterns involving stretching, mainly closed-chain, 59% (10 of 17 cases) and 72% (13 of 18 cases) of cases involving contact, respectively. Likewise, based on our results, in both ST-CC and COMB2 pattern type injuries, the technical action of “

dispute” predominates. Relating the last two points, in football there are situations in which it is necessary to collide with an opponent in order to get the ball, and as has been previously highlighted, this can generate large external forces that must be stopped, especially if the two players are running at high speed.

In our study we have observed that the only pattern that in some cases does not show the presence of the ball is the sprint pattern, while all the other patterns are totally influenced by it. The presence of the ball determines whether or not the ball was involved at the time of injury, in other words, whether its presence was relevant in affecting the mechanism of injury. Disputing against an opponent to get possession of the ball or trying to control a ball that comes from a long pass from a teammate, could be examples in which the ball would have a great influence on the mechanism. Likewise, the technical actions that have the highest relationship with this variable are “

dispute” (36%; 28 cases), “

none/stopped” (26%; 20 cases) and “

pass” (13%; 10 cases). Other studies also using systematic video analysis to investigate different types of injuries occurring in football [

28,

31,

33,

35] do not consider the presence of the ball as a factor that may influence the mechanism of injury, so we consider it as original and distinctive to this study. The only study that considers the ball as an analysis criterion is that of Aiello et al. [

51], however, they observed whether or not the injured player was carrying the ball at the time of the injury. It is important to clarify that our study did not analyze this criterion in this way, since in our case the player did not necessarily have to carry the ball, in other words we observed whether the activity close to the ball could influence the injured player’s action.

This could be related to the dynamic nature of team sports such as football, in which the environment is constantly changing, involving high neurocognitive and motor control demands [

37,

38,

39]. Consequently, football players must attend to complex visual demands involving an external focus of attention (e.g., looking at the ball), unanticipated perturbations (e.g., an opponent’s push), and other interactions with the environment, and may affect the complex integration of the sensory system (vestibular, visual, and somatosensory), ultimately altering the response of the neuromuscular system [

37,

38,

39]. Although these studies focus on anterior cruciate ligament injury, perhaps it might also be interesting to include this approach during the later stages of hamstring injury prevention programs, where tasks contain greater neurocognitive and motor control demands.

4.5. Specific Position

There are several studies that have analyzed the different physical demands differentiating by specific playing position of professional male football players in competitive games [

57,

58,

59,

60,

61,

62]. Almost all agree that midfielders, in general, are the players who travel the greatest total distance [

57,

58,

60,

62]. However, in terms of high metabolic demand actions (measured by metabolic power and high metabolic load distance), i.e., actions involving a high density of high-speed running and accelerations/decelerations, although there are some discrepancies between studies, it seems that wing players (wingers and fullbacks/wingbacks) and center midfielders are the ones that prevail over the others [

57,

58,

59,

60,

61,

62]. In contrast, most scientific papers also agree that the players with the lowest metabolic demand are central defenders and forwards [

57,

58,

60,

61], although it should be noted that some of them also show that forwards perform a large number of accelerations and sprints, but with more stop-start type runs [

57,

62]. However, it should be considered that such physical demands are directly conditioned by the style of play of the teams, which could explain the differences between studies investigating these variables [

57,

62].

Contrasting these results with our study, we can observe that wing players such as fullbacks/wingbacks and wingers are one of the positions most affected by hamstring injury, something that is not surprising considering the data previously discussed [

57,

58,

59,

60,

61]. However, the third group that prevails over the others is that of central defenders, an interesting fact considering that it is one of the positions with the lowest physical demands in men’s professional football [

57,

58,

60,

61]. Although probably in a more isolated way, these players also have to perform high-intensity actions, for example, to dispute ball possession against more offensive players (wingers and forwards), generating situations with high intensity running requirements [

57]. One of the possible reasons for the high incidence in these players could be related to the differences in physical load demands between training and matches. In this direction, several studies show that there are evident differences between training and matches in terms of physical demands, indicating that, usually, during training, the needs of high-speed running and sprinting are not sufficiently trained, something that may be associated with the preferential use of

small-sided games tasks [

62,

63].

4.6. Strengths and Limitations

This study provides a large sample of hamstring injuries sustained during official men’s professional football matches. Systematic video analysis has been carried out using a standardized process (observability of injuries, observation tool, defining the time of injury...) involving several experts from the field of sports science, a methodology that has already been used in several previous studies examining different types of injury [

28,

31,

32,

33,

34,

35,

36,

40].

However, there are some limitations. First, although the final sample of injuries is considerable, many injuries (47 cases out of 125; 38%) had to be discarded because of unobservability and because we could not establish a consensus on the mechanism or timing of the injury. Since this is a visual analysis, the number of cameras available, their recording quality and angulation are decisive. In addition, visual analysis of the injury makes it difficult to determine the specific event that triggered it. Nevertheless, it is possible to establish criteria based on the player’s reaction (gesture of discomfort, limping, hand on thigh...).

Second, the results of this study are purely descriptive, so in the future it could be interesting to include information from the kinematic and kinetic analysis of the different injury patterns, mainly those not investigated in the literature (such as COMB2). Moreover, data from other devices (e.g., GPS, gyroscopes...) that are used nowadays to quantify the load of players could be added and contrast this information with the descriptive analysis (velocities, accelerations, decelerations...).

Third, this study provides new insights into previously undescribed mechanisms of hamstring injury in men’s professional football. It would be interesting (and of great relevance) to analyze if these patterns are reproduced in other populations: other categories, female players, other team sports.

5. Conclusions

In summary, we have been able to observe that, despite the fact that the SP pattern continues to stand out over the others, the COMB2 pattern is also a pattern that should be considered, since its physical demands are unique. Likewise, within the SP pattern, the importance of curved sprints should be highlighted, since their neuromuscular demands differ from those of straight sprints. As with most muscle injuries, a large proportion of the injuries analyzed in this study continue to be non-contact, although in the closed chain patterns (COMB2 and ST-CC) the number of contact cases increases. In addition, the presence of the ball should also be a factor to consider, since the mechanics of the players could be altered by its presence. Finally, in our case, it was the wing players (fullbacks/wingbacks and wingers) who, in general, suffered the most from the hamstring injury, although the group of central defenders should also be considered.

Therefore, although hamstring injury prevention programs should continue to include high-intensity linear sprints, it is of great interest to include sprints with curvilinear and mechanical trajectories that work COMB2, because it has been observed that these mechanisms have a relatively high incidence. Also, considering that football players have to deal with high neurocognitive and motor control demands during matches, tasks with complex interactions with the environment, such as unexpected disturbances or external foci of attention, with a challenging component for the sensory system, should be included in the training or readaptation processes.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Aitor Gandarias-Madariaga, Antonio Martínez-Serrano, Pedro E. Alcaraz and Asier Zubillaga-Zubiaga; Formal analysis, Aitor Gandarias-Madariaga, Antonio Martínez-Serrano and Asier Zubillaga-Zubiaga; Methodology, Aitor Gandarias-Madariaga, Antonio Martínez-Serrano, Pedro E. Alcaraz, Julio Calleja-González and Asier Zubillaga-Zubiaga; Resources, Roberto López-Del Campo and Ricardo Resta; Supervision, Pedro E. Alcaraz, Julio Calleja-González and Asier Zubillaga-Zubiaga; Validation, Pedro E. Alcaraz, Julio Calleja-González and Asier Zubillaga-Zubiaga; Writing—original draft, Aitor Gandarias-Madariaga; Writing—review & editing, Aitor Gandarias-Madariaga. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

All data used in this study were treated confidentially, and players’ personal information was obtained through publicly available websites, such as

https://www.transfermarkt.es (Transfermarkt, Hamburg, Germany), so ethical clearance was not required.

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Authors report no conflict of interest.

References

- Calleja-González J, Mallo J, Cos F, Sampaio J, Jones MT, Marqués-Jiménez D, et al. A commentary of factors related to player availability and its influence on performance in elite team sports. Front Sports Act Living. 2023 Jan 16;4. [CrossRef]

- Eirale C, Tol JL, Farooq A, Smiley F, Chalabi H. Low injury rate strongly correlates with team success in Qatari professional football. Br J Sports Med. 2013 Aug;47(12):807–8. [CrossRef]

- Eliakim E, Morgulev E, Lidor R, Meckel Y. Estimation of injury costs: Financial damage of English Premier League teams’ underachievement due to injuries. BMJ Open Sport Exerc Med. 2020 May 20;6(1).

- Hägglund M, Waldén M, Magnusson H, Kristenson K, Bengtsson H, Ekstrand J. Injuries affect team performance negatively in professional football: An 11-year follow-up of the UEFA Champions League injury study. Br J Sports Med. 2013 Aug;47(12):738–42. [CrossRef]

- Bisciotti GN, Chamari K, Cena E, Carimati G, Bisciotti A, Bisciotti A, et al. Hamstring Injuries Prevention in Soccer: A Narrative Review of Current Literature. Joints. 2019 Sep;07(03):115–26. [CrossRef]

- Pérez-Gómez J, Adsuar JC, Alcaraz PE, Carlos-Vivas J. Physical exercises for preventing injuries among adult male football players: A systematic review. Vol. 11, Journal of Sport and Health Science. Elsevier B.V.; 2022. p. 115–22. [CrossRef]

- Ekstrand J, Spreco A, Bengtsson H, Bahr R. Injury rates decreased in men’s professional football: An 18-year prospective cohort study of almost 12 000 injuries sustained during 1.8 million hours of play. Br J Sports Med. 2021 Oct 1;55(19):1084–91.

- Ekstrand J, Hägglund M, Waldén M. Epidemiology of muscle injuries in professional football (soccer). American Journal of Sports Medicine [Internet]. 2011 Jun [cited 2020 Nov 18];39(6):1226–32. Available from: http://ajs.sagepub.com/supplemental/. [CrossRef]

- Ekstrand J, Hägglund M, Waldén M. Injury incidence and injury patterns in professional football: The UEFA injury study. Br J Sports Med [Internet]. 2011 [cited 2020 Nov 18];45(7):553–8. Available from: http://bjsm.bmj.com/. [CrossRef]

- Jones A, Jones G, Greig N, Bower P, Brown J, Hind K, et al. Epidemiology of injury in English Professional Football players: A cohort study. Physical Therapy in Sport [Internet]. 2019;35:18–22. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ptsp.2018.10.011. [CrossRef]

- Ekstrand J, Bengtsson H, Waldén M, Davison M, Khan KM, Hägglund M. Hamstring injury rates have increased during recent seasons and now constitute 24% of all injuries in men’s professional football: the UEFA Elite Club Injury Study from 2001/02 to 2021/22. Br J Sports Med [Internet]. 2022 Dec 6;bjsports-2021-105407. Available from: https://bjsm.bmj.com/lookup/doi/10.1136/bjsports-2021-105407. [CrossRef]

- Opar DA, Williams MD, Shield AJ. Hamstring strain injuries: Factors that Lead to injury and re-Injury. Sports Medicine. 2012;42(3):209–26.

- Beltran L, Ghazikhanian V, Padron M, Beltran J. The proximal hamstring muscle-tendon-bone unit: A review of the normal anatomy, biomechanics, and pathophysiology. Eur J Radiol. 2012;81(12):3772–9.

- Thorborg K, Opar D, Shield AJ. Prevention and Rehabilitation of Hamstring Injuries [Internet]. Springer; 2020. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-31638-9.

- Schache AG, Crossley KM, Macindoe IG, Fahrner BB, Pandy MG. Can a clinical test of hamstring strength identify football players at risk of hamstring strain? Knee Surgery, Sports Traumatology, Arthroscopy. 2011;19(1):38–41. [CrossRef]

- Schache AG, Dorn TW, Blanch PD, Brown NAT, Pandy MG. Mechanics of the human hamstring muscles during sprinting. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2012;44(4):647–58. [CrossRef]

- Schache AG, Kim HJ, Morgan DL, Pandy MG. Hamstring muscle forces prior to and immediately following an acute sprinting-related muscle strain injury. Gait Posture. 2010 May 1;32(1):136–40. [CrossRef]

- Orchard JW. Hamstrings are most susceptible to injury during the early stance phase of sprinting. Br J Sports Med. 2012;46(2):88–9. [CrossRef]

- Edouard P, Mendiguchia J, Lahti J, Arnal PJ, Gimenez P, Jiménez-Reyes P, et al. Sprint Acceleration Mechanics in Fatigue Conditions: Compensatory Role of Gluteal Muscles in Horizontal Force Production and Potential Protection of Hamstring Muscles. Front Physiol. 2018;9(November):1–12. [CrossRef]

- Freeman BW, Talpey SW, James LP, Young WB. Sprinting and hamstring strain injury: Beliefs and practices of professional physical performance coaches in Australian football. Physical Therapy in Sport [Internet]. 2021;48:12–9. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ptsp.2020.12.007. [CrossRef]

- Askling C, Malliaropoulos N, Karlsson J. High-speed running type or stretching-type of hamstring injuries makes a difference to treatment and prognosis. Br J Sports Med. 2012;46(2):86–7. [CrossRef]

- Danielsson A, Horvath A, Senorski C, Alentorn-Geli E, Garrett WE, Cugat R, et al. The mechanism of hamstring injuries- A systematic review [Internet]. Vol. 21, BMC Musculoskeletal Disorders. BioMed Central Ltd; 2020 [cited 2020 Nov 9]. p. 641. Available from: https://bmcmusculoskeletdisord.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12891-020-03658-8. [CrossRef]

- Huygaerts S, Cos F, Cohen DD, Calleja-González J, Guitart M, Blazevich AJ, et al. Mechanisms of Hamstring Strain Injury: Interactions between Fatigue, Muscle Activation and Function. Sports [Internet]. 2020;8(5):65. Available from: www.mdpi.com/journal/sports. [CrossRef]

- Mendiguchia J, Castano-Zambudio A, Jimenez-Reyes P, Morin JB, Edouard P, Conceicao F, et al. Can We Modify Maximal Speed Running Posture? Implications for Performance and Hamstring Injury Management. Int J Sports Physiol Perform. 2022 Mar 1;17(3):374–83. [CrossRef]

- Bourne MN, Pollard C, Messer D, Timmins RG, Opar DA, Williams MD, et al. Hamstring and gluteal activation during high-speed overground running: Impact of prior strain injury. J Sports Sci. 2021;39(18):2073–9. [CrossRef]

- Wolski L, Pappas E, Hiller C, Halaki M, Fong Yan A. Is there an association between high-speed running biomechanics and hamstring strain injury? A systematic review. Sports Biomechanics. Routledge; 2021. [CrossRef]

- Wilmes E, de Ruiter CJ, Bastiaansen BJC, Goedhart EA, Brink MS, van der Helm FCT, et al. Associations between Hamstring Fatigue and Sprint Kinematics during a Simulated Football (Soccer) Match. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2021 Dec 1;53(12):2586–95. [CrossRef]

- Gronwald T, Klein C, Hoenig T, Pietzonka M, Bloch H, Edouard P, et al. Hamstring injury patterns in professional male football (soccer): a systematic video analysis of 52 cases. Br J Sports Med. 2022 Feb 1;56(3):165–71. [CrossRef]

- Kenneally-Dabrowski C, Brown NAT, Warmenhoven J, Serpell BG, Perriman D, Lai AKM, et al. Late swing running mechanics influence hamstring injury susceptibility in elite rugby athletes: A prospective exploratory analysis. J Biomech. 2019 Jul 19;92:112–9. [CrossRef]

- Askling C, Thorstensson A. Hamstring muscle strain in sprinters. Vol. 23, New Studies in Athletics. 2008. 67–79 p.

- Jokela A, Rodas FCBarcelona G, Valle X, Kosola J, Rodas G, Til L, et al. Mechanisms of Hamstring Injury in Professional Soccer Players: Video Analysis and Magnetic Resonance Imaging Findings. 2022; Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/JSM.0000000000001109. [CrossRef]

- Kerin F, Farrell G, Tierney P, McCarthy Persson U, De Vito G, Delahunt E. Its not all about sprinting: Mechanisms of acute hamstring strain injuries in professional male rugby union-a systematic visual video analysis. Br J Sports Med. 2022; [CrossRef]

- Della Villa F, Buckthorpe M, Grassi A, Nabiuzzi A, Tosarelli F, Zaffagnini S, et al. Systematic video analysis of ACL injuries in professional male football (soccer): injury mechanisms, situational patterns and biomechanics study on 134 consecutive cases. Br J Sports Med. 2020 Dec 1;54(23):1423–32.

- Rekik RN, Bahr R, Cruz F, D’Hooghe P, Read P, Tabben M, et al. 046 The mechanisms of anterior cruciate ligament injuries in male professional football players in the middle east: a systematic video analysis of 15 cases. In BMJ; 2021. p. A19.2-A19.

- Klein C, Luig P, Henke T, Bloch H, Platen P. Nine typical injury patterns in German professional male football (soccer): A systematic visual video analysis of 345 match injuries. Br J Sports Med. 2021 Apr 1;55(7):390–6. [CrossRef]

- Serner A, Mosler AB, Tol JL, Bahr R, Weir A. Mechanisms of acute adductor longus injuries in male football players: a systematic visual video analysis. Br J Sports Med [Internet]. 2019 Feb 1 [cited 2023 Mar 24];53(3):158–64. Available from: https://bjsm.bmj.com/content/53/3/158. [CrossRef]

- Grooms D, Appelbaum G, Onate J. Neuroplasticity following anterior cruciate ligament injury: A framework for visual-motor training approaches in rehabilitation. Journal of Orthopaedic and Sports Physical Therapy. 2015 May 1;45(5):381–93. [CrossRef]

- Kakavas G, Malliaropoulos N, Bikos G, Pruna R, Valle X, Tsaklis P, et al. Periodization in Anterior Cruciate Ligament Rehabilitation: A Novel Framework. Vol. 30, Medical Principles and Practice. S. Karger AG; 2021. p. 101–8. [CrossRef]

- Kakavs G, Forelli F, Malliaropoulos N, Hewett TE, Tsaklis P. Periodization in Anterior Cruciate Ligament Rehabilitation: New Framework Versus Old Model? A Clinical Commentary. Vol. 18, International Journal of Sports Physical Therapy. North American Sports Medicine Institute; 2023. p. 541–6. [CrossRef]

- Montgomery C, Blackburn J, Withers D, Tierney G, Moran C, Simms C. Mechanisms of ACL injury in professional rugby union: A systematic video analysis of 36 cases. Br J Sports Med. 2018 Aug 1;52(15):994–1001. [CrossRef]

- Anguera MT, Blanco Á, Losada JL, Hernández A. La metodología observacional en el deporte : conceptos básicos. Educación fisica y deporte Revista digital. 2000;24:5.

- Bakeman R, Gottman JM. Observacion de la interaccion: introduccion al analisis secuencial. 1989;275–275.

- Fortes AM, Gómez M A, Hongyou L, Sampedro. Validación Inter-operador de VideobserverTM Inter-operator reliability of VideobserverTM Validação Inter-operador de VideobserverTM. Cuadernos de Psicología del Deporte [Internet]. 2016;16(2):137–52. Available from: http://revistas.um.es/cpd.

- Higashihara A, Nagano Y, Takahashi K, Fukubayashi T. Effects of forward trunk lean on hamstring muscle kinematics during sprinting. J Sports Sci [Internet]. 2015;33(13):1366–75. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/02640414.2014.990483. [CrossRef]

- Higashihara A, Nagano Y, Ono T, Fukubayashi T. Differences in hamstring activation characteristics between the acceleration and maximum-speed phases of sprinting. J Sports Sci [Internet]. 2018;36(12):1313–8. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1080/02640414.2017.1375548. [CrossRef]

- Zhong Y, Fu W, Wei S, Li Q, Liu Y. Joint Torque and Mechanical Power of Lower Extremity and Its Relevance to Hamstring Strain during Sprint Running. J Healthc Eng. 2017;2017. [CrossRef]

- Yu B, Queen RM, Abbey AN, Liu Y, Moorman CT, Garrett WE. Hamstring muscle kinematics and activation during overground sprinting. J Biomech. 2008;41(15):3121–6. [CrossRef]

- Yu B, Liu H, Garrett WE. Mechanism of hamstring muscle strain injury in sprinting. J Sport Health Sci [Internet]. 2017;6(2):130–2. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jshs.2017.02.002. [CrossRef]

- Chumanov ES, Heiderscheit BC, Thelen DG. Hamstring musculotendon dynamics during stance and swing phases of high-speed running. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2011;43(3):525–32. [CrossRef]

- Sun Y, Wei S, Zhong Y, Fu W, Li L, Liu Y. How joint torques affect hamstring injury risk in sprinting swing-stance transition. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2015 Feb 2;47(2):373–80. [CrossRef]

- Aiello F, Di Claudio C, Fanchini M, Impellizzeri FM, McCall A, Sharp C, et al. Do non-contact injuries occur during high-speed running in elite football? Preliminary results from a novel GPS and video-based method. J Sci Med Sport. 2023 Sep 1;26(9):465–70. [CrossRef]

- Born DP, Zinner C, Düking P, Sperlich B. Multi-Directional Sprint Training Improves Change-Of-Direction Speed and Reactive Agility in Young Highly Trained Soccer Players. J Sports Sci Med [Internet]. 2016;15:314–9. Available from: http://www.jssm.org.

- Loturco I, Pereira LA, Fílter A, Olivares-Jabalera J, Reis VP, Fernandes V, et al. Curve sprinting in soccer: Relationship with linear sprints and vertical jump performance. Biol Sport. 2020;37(3):277–83.

- Fílter A, Olivares J, Santalla A, Nakamura FY, Loturco I, Requena B. New curve sprint test for soccer players: Reliability and relationship with linear sprint. J Sports Sci. 2020 Jun 17;38(11–12):1320–5.

- Fílter A, Olivares-Jabalera J, Santalla A, Morente-Sánchez J, Robles-Rodríguez J, Requena B, et al. Curve Sprinting in Soccer: Kinematic and Neuromuscular Analysis. Int J Sports Med. 2020 Oct 1;41(11):744–50. [CrossRef]

- Dalton SL, Kerr ZY, Dompier TP. Epidemiology of hamstring strains in 25 NCAA sports in the 2009-2010 to 2013-2014 academic years. American Journal of Sports Medicine. 2015;43(11):2671–9. [CrossRef]

- Kubayi A. Position-specific physical and technical demands during the 2019 COPA América Football tournament. South African Journal of Sports Medicine. 2021;33(1). [CrossRef]

- Martín-García A, Casamichana D, Gómez Díaz A, Cos F, Gabbett TJ. Differences in the Most Demanding Passages of Play in Football Competition [Internet]. Vol. 17, ©Journal of Sports Science and Medicine. 2018. Available from: http://www.jssm.org.

- Caro E, Campos-Vazquez MA, Lapuente-Sagarra M, Caparros T. Analysis of professional soccer players in competitive match play based on submaximum intensity periods. PeerJ. 2022;10. [CrossRef]

- Thoseby B, D. Govus A, Clarke A, J. Middleton K, Dascombe B. Positional and temporal differences in peak match running demands of elite football. Biol Sport. 2023;40(1):311–9.

- Oliva-Lozano JM, Rojas-Valverde D, Gómez-Carmona CD, Fortes V, Pino-Ortega J. Worst case scenario match analysis and contextual variables in professional soccer players: A longitudinal study. Biol Sport. 2020;37(4):429–36. [CrossRef]

- Guerrero-Calderón B, Morcillo JA, Chena M, Castillo-Rodríguez A. Comparison of training and match load between metabolic and running speed metrics of professional Spanish soccer players by playing position. Biol Sport. 2022;39(4):933–41. [CrossRef]

- Clemente FM, Rabbani A, Conte D, Castillo D, Afonso J, Clark CCT, et al. Training/match external load ratios in professional soccer players: A full-season study. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2019 Sep 1;16(17). [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).