Submitted:

03 April 2025

Posted:

03 April 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Preparation of the PEO Gels

2.2. Characterisation of the PEO Gels

2.3. SSE 3D Printing

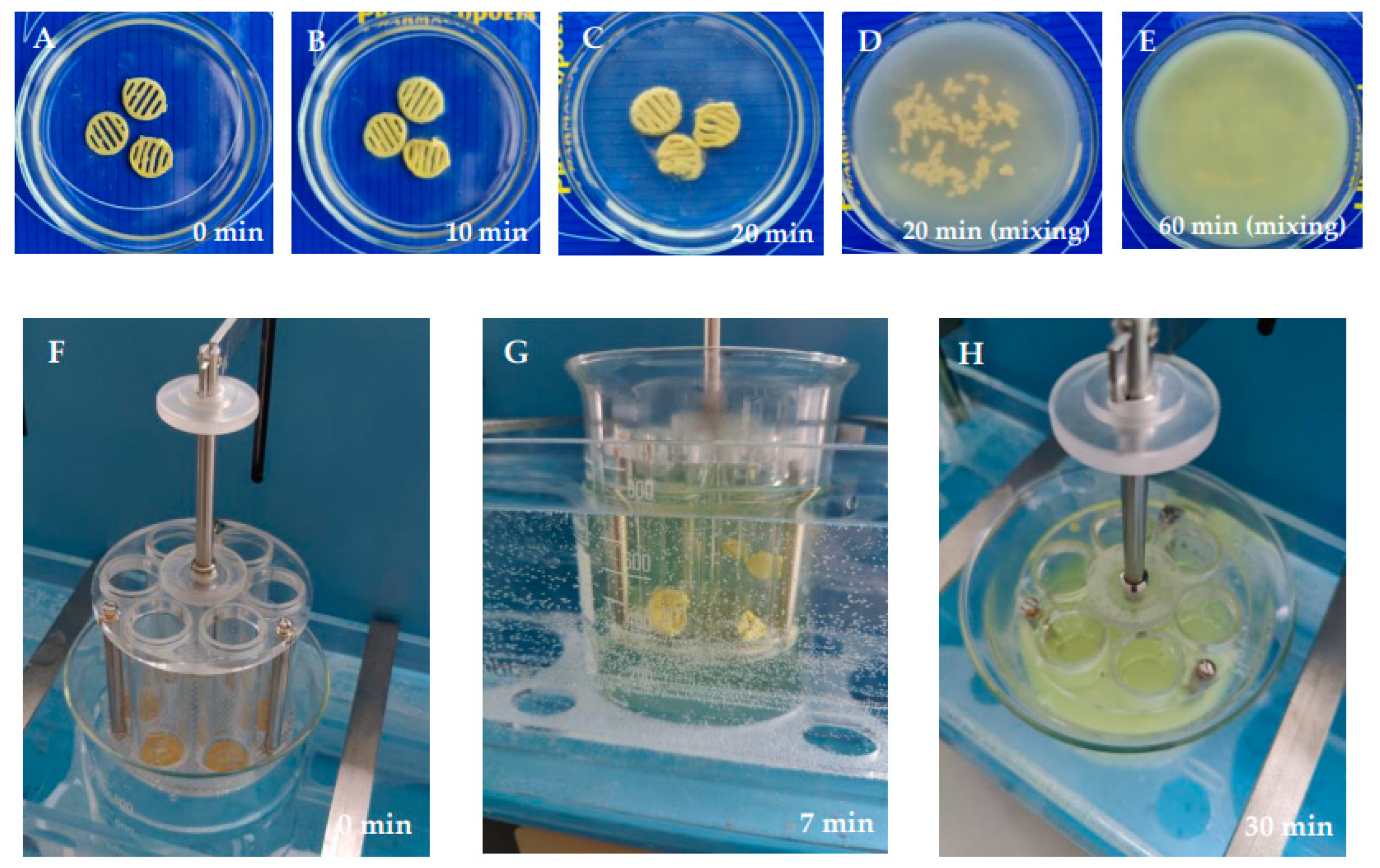

2.4. Disintegration Test In Vitro

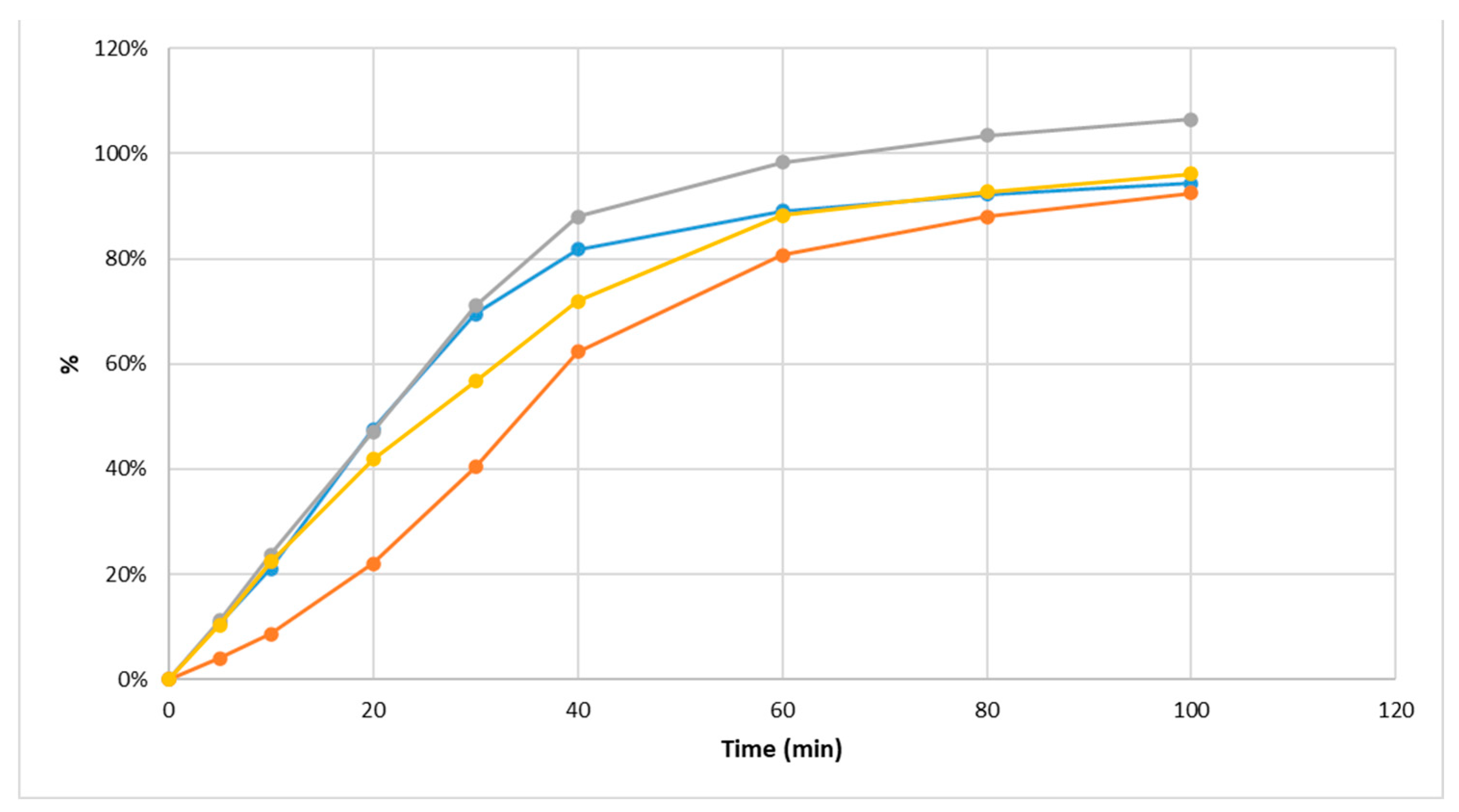

2.5. Dissolution Test In Vitro

2.6. Assay of Rutin Content by UV Spectrophotometry

2.7. Assay of Rutin Content by HPLC

2.8. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

6. Patents

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Wen, K.; Fang, X.; Yang, J.; Yao, Y.; Nandakumar, K.S.; Salem, M.L.; Cheng, K. Recent Research on Flavonoids and Their Biomedical Applications. CMC 2021, 28, 1042–1066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dias, M.C.; Pinto, D.C.G.A.; Silva, A.M.S. Plant Flavonoids: Chemical Characteristics and Biological Activity. Molecules 2021, 26, 5377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prasad, R.; Prasad, S.B. A Review on the Chemistry and Biological Properties of Rutin, a Promising Nutraceutical Agent. Asian J Pharm Pharmacol 2019, 5, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, K.; Ren, X.; Wang, J.; Zhang, Q.; Fu, X.; Zhang, P.-C. Clinical Development and Informatics Analysis of Natural and Semi-Synthetic Flavonoid Drugs: A Critical Review. Journal of Advanced Research 2024, 63, 269–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hosseinzadeh, H.; Nassiri-Asl, M. Review of the Protective Effects of Rutin on the Metabolic Function as an Important Dietary Flavonoid. J Endocrinol Invest 2014, 37, 783–788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gullón, B.; Lú-Chau, T.A.; Moreira, M.T.; Lema, J.M.; Eibes, G. Rutin: A Review on Extraction, Identification and Purification Methods, Biological Activities and Approaches to Enhance Its Bioavailability. Trends in Food Science & Technology 2017, 67, 220–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goyal, J.; Verma, P.K. An Overview of Biosynthetic Pathway and Therapeutic Potential of Rutin. MRMC 2023, 23, 1451–1460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Wang, L.; Wang, T.; Li, Z.; Gao, Y.; Cui, S.W.; Qiu, J. Comparison of Quercetin and Rutin Inhibitory Influence on Tartary Buckwheat Starch Digestion in Vitro and Their Differences in Binding Sites with the Digestive Enzyme. Food Chemistry 2022, 367, 130762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Wang, L.; Li, Z.; Gao, Y.; Cui, S.W.; Wang, T.; Qiu, J. Diverse Effects of Rutin and Quercetin on the Pasting, Rheological and Structural Properties of Tartary Buckwheat Starch. Food Chemistry 2021, 335, 127556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinto, T.M.D.S.; Almeida, F.L.A.; Xavier, J.O.D.L.; Del-Vechio-Vieira, G.; Araújo, A.L.S.D.M.; Pinho, J.D.J.R.G.D.; Alves, M.S.; Sousa, O.V.D. Biopharmacotechnical and Physical Properties of Solid Pharmaceutical Forms Containing Rutin Commercially Acquired in Juiz de Fora City, Brazil. Acta Sci. Health Sci. 2020, 42, e52212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paudel, K.R.; Wadhwa, R.; Tew, X.N.; Lau, N.J.X.; Madheswaran, T.; Panneerselvam, J.; Zeeshan, F.; Kumar, P.; Gupta, G.; Anand, K.; et al. Rutin Loaded Liquid Crystalline Nanoparticles Inhibit Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer Proliferation and Migration in Vitro. Life Sciences 2021, 276, 119436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, J.; Yang, J.; Xie, Y. Improvement Strategies for the Oral Bioavailability of Poorly Water-Soluble Flavonoids: An Overview. International Journal of Pharmaceutics 2019, 570, 118642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ninfali, P.; Antonelli, A.; Magnani, M.; Scarpa, E.S. Antiviral Properties of Flavonoids and Delivery Strategies. Nutrients 2020, 12, 2534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hassani, S.; Maghsoudi, H.; Fattahi, F.; Malekinejad, F.; Hajmalek, N.; Sheikhnia, F.; Kheradmand, F.; Fahimirad, S.; Ghorbanpour, M. Flavonoids Nanostructures Promising Therapeutic Efficiencies in Colorectal Cancer. International Journal of Biological Macromolecules 2023, 241, 124508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Zhang, L.; Ding, Q.; Zhang, S.; Sun, S.; Liu, W.; Liu, J.; Han, X.; Ding, C. Flavonoid-Loaded Biomaterials in Bone Defect Repair. Molecules 2023, 28, 6888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akash, S.R.; Tabassum, A.; Aditee, L.M.; Rahman, A.; Hossain, M.I.; Hannan, Md.A.; Uddin, M.J. Pharmacological Insight of Rutin as a Potential Candidate against Peptic Ulcer. Biomedicine & Pharmacotherapy 2024, 177, 116961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Ding, Z.; Li, Z.; Ding, Y.; Jiang, F.; Liu, J. Antioxidant and Antibacterial Study of 10 Flavonoids Revealed Rutin as a Potential Antibiofilm Agent in Klebsiella Pneumoniae Strains Isolated from Hospitalized Patients. Microbial Pathogenesis 2021, 159, 105121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolarevic, A.; Pavlovic, A.; Djordjevic, A.; Lazarevic, J.; Savic, S.; Kocic, G.; Anderluh, M.; Smelcerovic, A. Rutin as Deoxyribonuclease I Inhibitor. Chemistry & Biodiversity 2019, 16, e1900069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gęgotek, A.; Jarocka-Karpowicz, I.; Skrzydlewska, E. Cytoprotective Effect of Ascorbic Acid and Rutin against Oxidative Changes in the Proteome of Skin Fibroblasts Cultured in a Three-Dimensional System. Nutrients 2020, 12, 1074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ganeshpurkar, A.; Saluja, A.K. The Pharmacological Potential of Rutin. Saudi Pharmaceutical Journal 2017, 25, 149–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibrahim, M.A.A.; Mohamed, E.A.R.; Abdelrahman, A.H.M.; Allemailem, K.S.; Moustafa, M.F.; Shawky, A.M.; Mahzari, A.; Hakami, A.R.; Abdeljawaad, K.A.A.; Atia, M.A.M. Rutin and Flavone Analogs as Prospective SARS-CoV-2 Main Protease Inhibitors: In Silico Drug Discovery Study. Journal of Molecular Graphics and Modelling 2021, 105, 107904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Azad, M.A.; Olawuni, D.; Kimbell, G.; Badruddoza, A.Z.M.; Hossain, Md.S.; Sultana, T. Polymers for Extrusion-Based 3D Printing of Pharmaceuticals: A Holistic Materials–Process Perspective. Pharmaceutics 2020, 12, 124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paccione, N.; Guarnizo-Herrero, V.; Ramalingam, M.; Larrarte, E.; Pedraz, J.L. Application of 3D Printing on the Design and Development of Pharmaceutical Oral Dosage Forms. Journal of Controlled Release 2024, 373, 463–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seoane-Viaño, I.; Januskaite, P.; Alvarez-Lorenzo, C.; Basit, A.W.; Goyanes, A. Semi-Solid Extrusion 3D Printing in Drug Delivery and Biomedicine: Personalised Solutions for Healthcare Challenges. Journal of Controlled Release 2021, 332, 367–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, H.; Han, B.; Tong, T.; Jin, X.; Peng, Y.; Guo, M.; Li, B.; Ding, J.; Kong, Q.; Wang, Q. 3D Printing Processes in Precise Drug Delivery for Personalized Medicine. Biofabrication 2024, 16, 032001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johannesson, J.; Wu, M.; Johansson, M.; Bergström, C.A.S. Quality Attributes for Printable Emulsion Gels and 3D-Printed Tablets: Towards Production of Personalized Dosage Forms. International Journal of Pharmaceutics 2023, 646, 123413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viidik, L.; Seera, D.; Antikainen, O.; Kogermann, K.; Heinämäki, J.; Laidmäe, I. 3D-Printability of Aqueous Poly(Ethylene Oxide) Gels. European Polymer Journal 2019, 120, 109206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koshovyi, O.; Heinämäki, J.; Kurtina, D.; Meos, A.; Stremoukhov, O.; Topelius, N.S.; Raal, A. Semi-Solid Extrusion 3D Printing of Plant-Origin Rosmarinic Acid Loaded in Aqueous Polyethylene Oxide Gels. J Pharm Pharmacogn Res 2025, 13, 115–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koshovyi, O.; Heinämäki, J.; Laidmäe, I.; Topelius, N.S.; Grytsyk, A.; Raal, A. Semi-Solid Extrusion 3D-Printing of Eucalypt Extract-Loaded Polyethylene Oxide Gels Intended for Pharmaceutical Applications. Annals of 3D Printed Medicine 2023, 12, 100123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koshovyi, O.; Heinämäki, J.; Raal, A.; Laidmäe, I.; Topelius, N.S.; Komisarenko, M.; Komissarenko, A. Pharmaceutical 3D-Printing of Nanoemulsified Eucalypt Extracts and Their Antimicrobial Activity. European Journal of Pharmaceutical Sciences 2023, 187, 106487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koshovyi, O.; Sepp, J.; Jakštas, V.; Žvikas, V.; Kireyev, I.; Karpun, Y.; Odyntsova, V.; Heinämäki, J.; Raal, A. German Chamomile (Matricaria Chamomilla L.) Flower Extract, Its Amino Acid Preparations and 3D-Printed Dosage Forms: Phytochemical, Pharmacological, Technological, and Molecular Docking Study. IJMS 2024, 25, 8292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Botsula, I.; Kireyev, I.; Koshovyi, O.; Heinämäki, J.; Ain, R.; Mazur, M.; Chebanov, V. Semi-Solid Extrusion 3D Printing of Functionalized Polyethylene Oxide Gels Loaded with 1,2,3-Triazolo-1,4-Benzodiazepine Nanofibers and Valine-Modified Motherwort (Leonurus Cardiaca L.) Dry Extract. SR: PS 2024, 40–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koshovyi, O.; Vlasova, I.; Laur, H.; Kravchenko, G.; Krasilnikova, O.; Granica, S.; Piwowarski, J.P.; Heinämäki, J.; Raal, A. Chemical Composition and Insulin-Resistance Activity of Arginine-Loaded American Cranberry (Vaccinium Macrocarpon Aiton, Ericaceae) Leaf Extracts. Pharmaceutics 2023, 15, 2528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anderspuk, H.; Viidik, L.; Olado, K.; Kogermann, K.; Juppo, A.; Heinämäki, J.; Laidmäe, I. Effects of Crosslinking on the Physical Solid-State and Dissolution Properties of 3D-Printed Theophylline Tablets. Annals of 3D Printed Medicine 2021, 4, 100031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Pharmacopoeia, 11.0 ed.; Council of Europe: Strasbourg, 2022.

- Kukhtenko, H.; Bevz, N.; Konechnyi, Y.; Kukhtenko, O.; Jasicka-Misiak, I. Spectrophotometric and Chromatographic Assessment of Total Polyphenol and Flavonoid Content in Rhododendron Tomentosum Extracts and Their Antioxidant and Antimicrobial Activity. Molecules 2024, 29, 1095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- European Pharmacopoeia; 11.5 Ed.; C: Strasbourg, 2024; Rutoside Trihydrate. 07/2024:1795. P. 6033-6035. 2024.

- Lapach, S.N.; Chubenko, A.V.; Babich, P.N. Statistical Methods in Biomedical Research Using Excel; MORION: Kyiv, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Weber, J.; Buske, J.; Mäder, K.; Garidel, P.; Diederichs, T. Oxidation of polysorbates - An underestimated degradation pathway? Int J Pharm X. 2023, 6, 100202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rowe, R.C.; Sheskey, P.J.; Quinn, M.E. Handbook of Pharmaceutical Excipients; Pharmaceutical Press and American Pharmacists Association: Washington, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Wuchner, K.; Yi, L.; Chery, C.; Nikels, F.; Junge, F.; Crotts, G.; Rinaldi, G.; Starkey, J.A.; Bechtold-Peters, K.; Shuman, M.; et al. Industry Perspective on the Use and Characterization of Polysorbates for Biopharmaceutical Products Part 1: Survey Report on Current State and Common Practices for Handling and Control of Polysorbates. Journal of Pharmaceutical Sciences 2022, 111, 1280–1291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wuchner, K.; Yi, L.; Chery, C.; Nikels, F.; Junge, F.; Crotts, G.; Rinaldi, G.; Starkey, J.A.; Bechtold-Peters, K.; Shuman, M.; et al. Industry Perspective on the Use and Characterization of Polysorbates for Biopharmaceutical Products Part 2: Survey Report on Control Strategy Preparing for the Future. Journal of Pharmaceutical Sciences 2022, 111, 2955–2967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dani, C.; Poggi, C. Antioxidant Properties of Surfactant. In Perinatal and Prenatal Disorders; Dennery, P.A., Buonocore, G., Saugstad, O.D., Eds.; Oxidative Stress in Applied Basic Research and Clinical Practice; Springer New York: New York, NY, 2014; ISBN 978-1-4939-1404-3. [Google Scholar]

- Boddepalli, U.; Gandhi, I.S.R.; Panda, B. Stability of Three-Dimensional Printable Foam Concrete as Function of Surfactant Characteristics. Front. Struct. Civ. Eng. 2023, 17, 935–947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohalkar, R.; Poul, B.; Patil, S.S.; Hetkar, M.A.; Chavan, S.D. A Review on Immediate Release Drug Delivery Systems. PharmaTutor 2014, 2, 95–109. [Google Scholar]

- Kute, V.G.; Patil, R.S.; Kute, V.G.; Kaluse, P.D. Immediate-release dosage form; focus on disintegrants use as a promising excipient. Journal of Drug Delivery and Therapeutics 2023, 13, 170–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carvalho, D.; Pinho, C.; Oliveira, R.; Moreira, F.; Oliveira, A.I. Chromatographic Methods Developed for the Quantification of Quercetin Extracted from Natural Sources: Systematic Review of Published Studies from 2018 to 2022. Molecules 2023, 28(23), 7714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Świątek, S.; Czyrski, A. Analytical Methods for Determining Psychoactive Substances in Various Matrices: A Review. Crit Rev Anal Chem. 2024, 18, 1–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Exp. | Rutin, g | Tween 80, g | PEO, g | Ethanol, ml | Water, ml |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| T3_1 | 1.00 | 0.30 | 1.20 | 1.00 | 9.00 |

| T5_0.5 | 0.50 | 0.50 | 1.20 | 1.00 | 9.00 |

| T5_1 | 1.00 | 0.50 | 1.20 | 1.00 | 9.00 |

| T5_1.5 | 1.50 | 0.50 | 1.20 | 2.00 | 8.00 |

| Sample | Viscosity, cP (speed 0.03 RPM, shear rate 0.060 1/s, temperature 22 ± 2 °C, n = 3) |

|---|---|

| T3_1 | 219,867 ± 27,380 |

| T5_0.5 | 250,867 ± 13,169 |

| T5_1 | 223,367 ± 14,712 |

| T5_1.5 | 226,567 ± 9,845 |

| Sample | Weight, mg | Area (S), mm2 | Spractical / Stheoretical |

|---|---|---|---|

| T5_0.5 | 117.7 ± 1.3 | 336.3 ± 28.5 | 1.04 |

| T5_1 | 163.0 ± 18.0 | 339.9 ± 20.8 | 1.05 |

| T5_1.5 | 184.2 ± 16.4 | 389.2 ± 24.4 | 1.20 |

| Sample | Weight, mg | Photographs |

|---|---|---|

| T5_0.5 | 90.2 ± 4.2 |  |

| T5_1 | 168.2 ± 8.4 |  |

| T5_1.5 | 165.7 ± 7.8 |  |

| Sample | Content of rutin, % (n = 3) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Theoretical | UV spectrophotometry | HPLC | |

| T5_0.5 | 22.72 | 17.23 ± 0.23 | 18.5 |

| T5_1 | 36.79 | 31.21 ± 0.36 | 30.1 |

| T5_1.5 | 46.42 | 42.35 ± 0.49 | 41.1 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).