1. Introduction

The provision of midwifery care is demanding and frequently associated with emotional exhaustion resulting from work overload [

1]. Contemporary midwifery is grounded in a philosophy that places women and their families at the center of care while emphasizing ethical and evidence-based practice [

2]. A global shortage of midwives persists, with many professionals leaving the field primarily due to challenging working conditions, including excessive workload and inadequate professional support [

3,

4]. The Work, Health and Emotional Lives of Midwives (WHELM) program, which assessed midwives' well-being across twelve countries, revealed that midwives often feel overwhelmed, lack autonomy, experience a sense of underappreciation, and receive insufficient support [

2]. Occupational stress and its associated health consequences, including lifestyle-related risk factors, have emerged as growing concerns within the profession. Workload-induced stress diminishes professional confidence and is a significant contributor to dissatisfaction with midwifery as a career [

5]. Recent research indicates that chronic stress and irregular work schedules may disrupt dietary habits and increase metabolic health risks [

5,

6,

7].

In Poland, midwives play an essential role in the healthcare system, not only in maternal care but also in a wide range of preventive and health education initiatives. Their responsibilities span obstetrics, gynecology, pregnancy pathology, neonatology, emergency services, and community healthcare—roles that shape both their professional trajectories and broader lifestyle patterns. These responsibilities influence health behaviors, including dietary practices and overall well-being, potentially heightening their susceptibility to chronic illnesses [

7]. An expanding body of evidence suggests that, due to high job demands and shift work, midwives may be particularly vulnerable to nutrition-related health risks, including abnormal body weight and disordered eating behaviors [

8,

9].

Nutritional health risks encompass a spectrum of issues, such as abnormal body weight, disordered eating behaviors, and inadequate dietary patterns, all of which may carry serious long-term health implications. Eating disorders (EDs) are complex psychiatric conditions marked by severe disruptions in eating behavior, body image dissatisfaction, and an intense preoccupation with weight and food. These disorders are formally recognized in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5) and the International Classification of Diseases (ICD-11) as serious mental health conditions with potentially severe medical and psychological consequences [

10,

11].

Importantly, nutritional health risks extend beyond clinically diagnosed EDs and include body weight abnormalities—both underweight and overweight/obesity—which are associated with increased morbidity and mortality [

12,

13]. Abnormal BMI levels have been linked to higher risks of metabolic disorders, cardiovascular complications, and reduced quality of life. Certain EDs, such as anorexia nervosa and binge eating disorder, are closely associated with extreme BMI values—either significantly low or high—further intensifying health risks among affected individuals [

14,

15].

While EDs have been widely studied in the general population, research on broader nutritional health risks among healthcare professionals—especially midwives—remains scarce. Nevertheless, existing evidence indicates that even during the early stages of their training, medical and healthcare students display elevated rates of ED symptoms compared to the general population. The pressures of academic achievement, demanding workloads, and high expectations in medical education may serve as early contributors to the development of disordered eating behaviors [

16,

17]. As these stressors often persist and intensify over the course of a healthcare professional's career, the risk of nutrition-related health problems—such as disordered eating behaviors and abnormal body weight—may further escalate.

Moreover, there is increasing interest in the application of artificial intelligence (AI) in public health, particularly in examining the complex interplay of cultural, social, and environmental factors that influence individual and community health outcomes [

18].

Given the well-established links between occupational stress, shift work, and lifestyle patterns with adverse health outcomes, it is imperative to investigate whether midwives—who face substantial workplace demands—are particularly susceptible to nutrition-related health risks. These risks include both disordered eating behaviors and abnormal body weight. The present study aims to assess the prevalence and identify key predictors of nutrition-related health risks among midwives, with a focus on occupational and lifestyle-related determinants. By expanding the analysis beyond clinically diagnosed eating disorders, this research seeks to provide a more comprehensive understanding of the factors shaping midwives’ dietary health and overall well-being.

2. Materials and Methods

The study was conducted using a structured questionnaire comprising three sections: a customized demographic module and two standardized measurement tools.

The first instrument was the Eating Attitudes Test-26 (EAT-26) questionnaire [

19], a widely recognized tool for assessing the risk of eating disorders. Although not diagnostic, the EAT-26 facilitates the identification of individuals who may exhibit disordered eating patterns and require further evaluation. It contains 26 items rated on a four-point Likert scale (0–4), with item 24 reverse-scored. The validated Polish adaptation of the EAT-26 was used in this study [

20].

The second tool was the 5-item Quantitative Workload Inventory (QWI) [

21], designed to measure the perceived quantity and intensity of work performed. Each item is scored on a five-point Likert scale (1–5), with the total score ranging from 5 to 25. The Polish adaptation of the QWI scale was applied [

22].

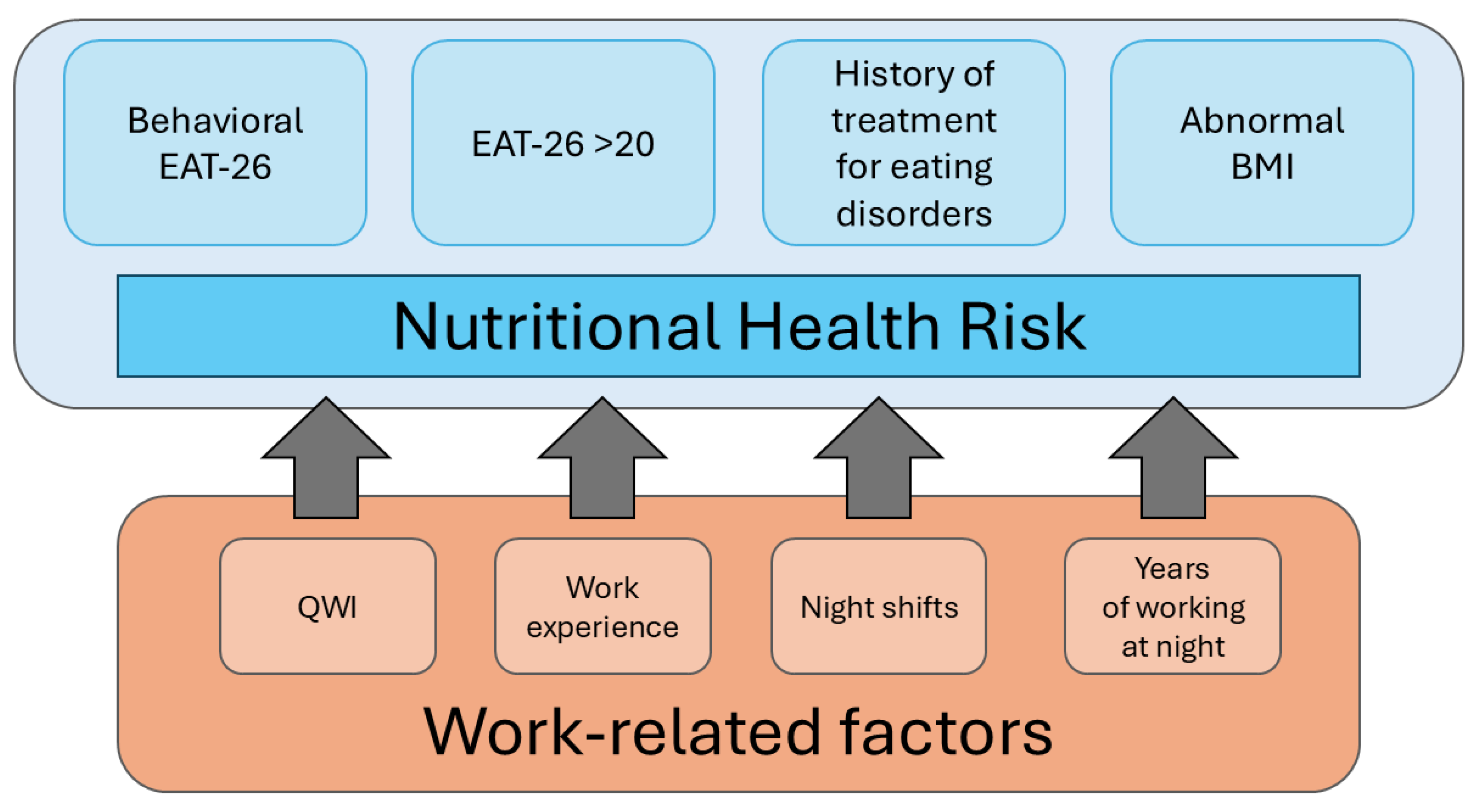

For the purposes of this study, nutrition-related health risk was defined based on several interrelated factors, including disordered eating behaviors and abnormal body weight. The classification was based on four key components, which were subsequently incorporated into the Classification and Regression Tree (C&RT) model analysis:

Abnormal body weight according to BMI classification – 287 participants (40.83%)

EAT-26 score > 20 – 42 participants (5.97%)

Behavioral indicators of disordered eating (ABCDE section of the questionnaire) – 253 participants (35.99%)

History of treatment for an eating disorder – 54 participants (7.68%)

Participants who met at least one of these criteria were classified as being at risk for nutrition-related health issues (

Figure 1).

In this study, the Classification and Regression Trees (C&RT) method—specifically, the univariate split selection—was employed for statistical analysis. C&RT is a decision tree algorithm designed to detect patterns within data and to facilitate predictive modeling. The primary objective of the classification tree analysis was to achieve the most accurate possible prediction of the dependent variable [

23].

The study sample comprised 740 professionally active Polish midwives recruited from the Centre for Postgraduate Education of Nurses and Midwives. Data collection was conducted using a traditional paper-and-pencil format. Of the 738 returned questionnaires, 35 were excluded due to incomplete responses. Consequently, 703 questionnaires were included in the final analysis.

Ethical approval for the study was granted by the Bioethics Committee of the Medical University of Warsaw (approval number: AKBE/104/2025).

Characteristics of the Study Group

The study group consisted exclusively of women (n = 703; 100%). The mean age of participants was 34.00 ± 10.06 years, with a median age of 29 years (range: 24–65). The average length of work experience was 10.24 ± 9.47 years, with a median of 5 years (range: 2–42). The average number of years worked during night shifts was 7.67 ± 8.45 years, with a median of 4 years (range: 0–38). A detailed breakdown of participant characteristics is presented in

Table 1.

Statistical Analyses

Group differences were analyzed using the Mann–Whitney U test and the chi-square test. Statistical significance was set at p < 0.05.

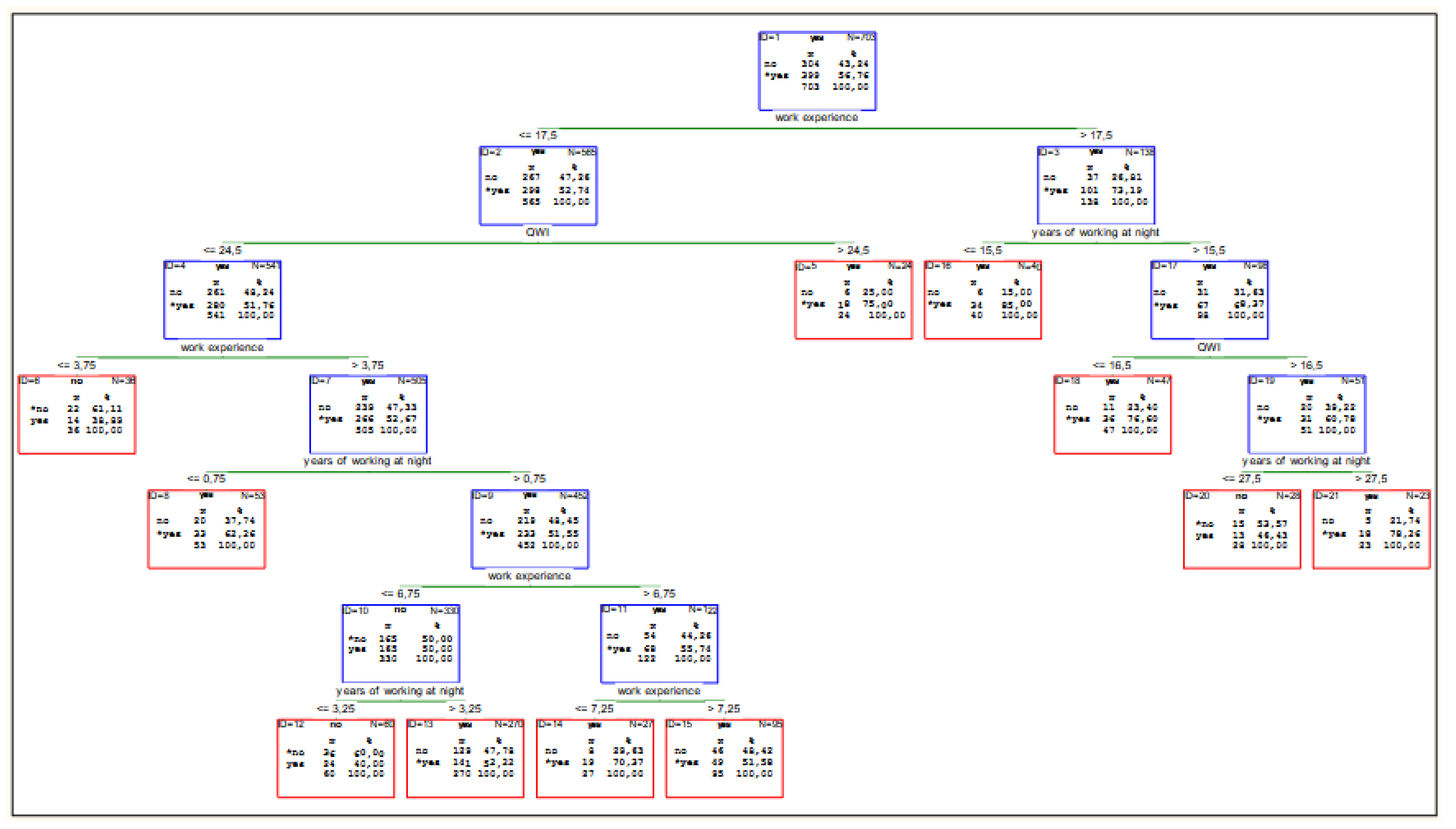

A Classification and Regression Tree (C&RT) model was constructed using V-fold cross-validation to identify significant predictors of nutritional health risk The model criterion was set at six levels, with a minimum number of offspring nodes equal to 20. The dependent variable in the model was the presence of nutritional health risk. Independent variables included work-related factors such as length of professional experience, duration of night shift work, and workload as measured by the QWI score. The group predisposed to eating disorders constituted more than half of all surveyed midwives (399, 56.76%). Detailed results are presented in

Table 2 and

Table 3.

The Area Under the Curve (AUC) of the model was 0.64, and the Gini coefficient was 0.27. Reliability analysis confirmed high internal consistency of the applied questionnaires, with Cronbach’s alpha coefficients of 0.87 for EAT-26 and 0.90 for QWI. The calculations were performed using Statistica 13.3 software.

3. Results

The mean BMI of the participants was 24.71 ± 4.80, with a median of 23.80 (min: 16.30, max: 50.12). The lower quartile (Q1) was 21.36, and the upper quartile (Q3) was 26.89. A detailed breakdown of BMI classification based on WHO guidelines [

24] is presented in

Table 4.

A classification model was developed based on variables reflecting the specific nature of midwifery work. The final model comprised 10 split nodes and 11 terminal nodes. Among the predictors, the number of years working night shifts had the highest predictive rank (rank = 100). Other variables with substantial predictive value included total work experience (rank = 97) and the Quantitative Workload Inventory (QWI) score (rank = 45).The variable night shifts (rank = 12) was found to be insignificant in the model. Overall, the model indicates that work experience is the most influential predictor of nutrition-related health risk.

Among midwives with more than 17.5 years of professional experience (mean age = 51.13 ± 5.24 years; median = 51.5; range = 41–65), the strongest predictive factors were the number of years working night shifts (n = 101) and the QWI score, particularly for those with extensive night shift exposure (more than 15.5 years; n = 67).

In contrast, for midwives with 17.5 years or less of professional experience (n = 298; mean age = 29.52 ± 5.05 years; median = 28; range = 24–55), the QWI score emerged as the most significant predictor—especially in individuals with more than 3.75 years of total experience (n = 266), regardless of the duration of night shift work.

A detailed breakdown of these patterns and their impact on nutritional health risk is provided in the subsequent section (see

Figure 2).

4. Discussion

The well-being of healthcare professionals is inextricably linked to patient safety outcomes. Poor emotional health among midwives is likely to negatively impact the quality, dignity, and safety of care provided to women and their newborns [

25]. Systematic reviews and meta-analyses based on large-scale observational studies have demonstrated associations between emotional well-being and working conditions in various healthcare professions—associations that are likely applicable to midwifery. Excessive work demands are commonly linked to burnout, particularly its core dimension of emotional exhaustion [

26]. The onset of depressive symptoms is often associated with high workload—characterized by elevated demands and limited autonomy—as well as a general lack of control over one’s work environment [

27]. Additional occupational stressors such as effort–reward imbalance, low organizational justice, role-related pressure, insufficient support, interpersonal conflict, long working hours, and job insecurity are all strongly associated with elevated anxiety and stress, contributing to a persistent sense of overload [

5,

28].

In the context of midwifery, specific sources of stress include shift work, high responsibility, excessive duties, time pressure, and fear of making irreversible mistakes, among others [

29]. Such work-related stress can overwhelm the interconnected biological, psychological, and social systems, ultimately leading to a range of negative somatic and psychological symptoms. Importantly, occupational stress influences not only job satisfaction but also health-related behaviors, including those linked to nutrition and eating habits [

30]. Given the significant impact of chronic work-related stress, it is crucial to consider its role in shaping lifestyle behaviors—particularly dietary patterns, physical activity, and self-care practices.

Despite growing awareness of mental health challenges among healthcare workers, nutrition-related health risks remain underdiagnosed and undertreated in this population. Several studies have identified a significant prevalence of overweight, obesity, and eating disorders among healthcare professionals—conditions that may co-occur and mutually reinforce one another [

31,

32]. Although validated screening instruments such as the Eating Attitudes Test-26 (EAT-26) [

19] have been used to assess disordered eating, their application within medical settings remains limited. Research specifically examining the relationship between workload and nutrition-related health risks among healthcare workers is scarce; and in the case of midwives, virtually non-existent. Much of the existing literature focuses on physicians or general nursing staff, often neglecting the unique emotional and physical demands placed on midwives. Despite evidence highlighting their vulnerability to burnout and mental health challenges [

33,

34], the association between occupational stressors and disordered eating in this group remains underexplored—underscoring the urgent need for further targeted research.

In our study, we used one of the machine learning methods, namely the decision tree. Thanks to a method that combines classification and regression using supervised learning, classification trees are characterized by simplicity while maintaining strong predictive capabilities [

35]. To date, no studies have been conducted specifically on the prevalence of eating disorders among medical staff or the work-related factors that may contribute to their development. Consequently, this study conducted a preliminary analysis of factors influencing nutritional health risks among midwives resulting from the specific nature of their work.

BMI in the Context of Nutritional Risk

Overweight and obesity are increasingly recognized as significant health concerns among nurses and midwives, with implications not only for their personal well-being but also for the quality of care they provide [

36]. According to the World Health Organization (WHO), a body mass index (BMI) between 25.0 and 29.9 kg/m² is classified as overweight, while a BMI of 30.0 kg/m² or higher is classified as obese [

24]. Excess body weight is associated with elevated risk for a range of chronic conditions, including cardiovascular disease, type 2 diabetes, hypertension, and certain cancers. Among healthcare professionals, these risks are compounded by demanding work schedules, shift duties, and elevated occupational stress—factors that can adversely affect dietary patterns and physical activity levels [

37].

Although underweight (BMI < 18.5 kg/m²) also presents health risks—particularly with regard to nutritional deficiencies and compromised immune function—the increasing prevalence of overweight and obesity among midwives and nurses warrants particular attention. These conditions can have long-term consequences for physical health, mental well-being, and professional performance [

38,

39].

In this study, abnormal BMI was among the predictors of eating disorder (ED) risk. Specifically, "extremely underweight" BMI was considered, based on guidance from the EAT-26 questionnaire [

40]. However, the EAT-26 guidelines do not clearly define "extremely underweight" for adults. Instead, they reference the NHANES III growth charts, which are based on pediatric percentiles developed for children and adolescents in the United States [

41].

Given the absence of a standardized adult threshold in the EAT-26 framework—and considering that this study focused on a Polish adult population—we adopted the WHO classification for “severe thinness” (BMI < 16) as a proxy for “extremely underweight” [

24]. According to this criterion, no participants in our sample met the threshold for severe thinness. However, 19 individuals (2.7%) were classified as underweight (BMI < 18.5), placing them below the normal BMI range.

While low body weight is often emphasized in the context of eating disorder risk, it is equally important to acknowledge that excess body weight may also be associated with disordered eating behaviors. In our sample, 99 midwives (14.08%) were classified as obese, including 9 individuals (1.28%) with severe obesity. There is substantial evidence of co-occurrence between obesity and eating disorders, particularly binge eating disorder (BED). Research indicates that individuals with higher BMI are at increased risk of developing BED, and conversely, that BED significantly contributes to the development and persistence of obesity [

39].

It is important to note that BMI is not a diagnostic criterion for eating disorders in either the

Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5) [

10] or the

International Classification of Diseases (ICD-11) [

11]. However, BMI may serve as a supporting indicator in clinical assessments. The EAT-26 questionnaire considers BMI only in the context of underweight, yet its threshold for “extremely underweight” remains undefined. If BMI is to function as a meaningful screening factor for nutritional health risks, its role requires further clarification and standardization.

Workload as a Predictor of Nutritional Health Risks

High workload has been consistently identified as a major factor adversely affecting emotional well-being in employees across high-demand professions. Although access to workplace resources—such as job autonomy and performance feedback—may help buffer some of these negative effects, such measures are frequently insufficient to fully mitigate the psychological burden [

42]. These insights underscore the critical importance of early intervention and continuous mental health monitoring for midwives, beginning at the onset of their careers.

All of these elements contribute to a distinct professional lifestyle among midwives—one that significantly influences eating behaviors, body image, and overall health. The physically and emotionally demanding nature of midwifery, coupled with extended work hours and unpredictable schedules, may disrupt regular eating patterns. These disruptions can lead to irregular meal timing and an increased risk of disordered eating behaviors [

43].

High-stress occupations often prompt individuals to adopt maladaptive coping mechanisms, including unhealthy dietary behaviors and, in some cases, the development of eating disorders [

44].

In the present study, although the total workload—as measured by the Quantitative Workload Inventory (QWI) score—did not emerge as an independent predictor, specific components such as professional experience and the cumulative duration of night shift work were identified as significant contributors to nutritional health risks.

Among midwives with more than 17.5 years of professional experience (mean age = 51.13 ± 5.24 years; median = 51.5; range = 41–65), the most salient predictive factors were years of working night shifts (n = 101) and the QWI score. These were especially influential among those with extensive night shift exposure (more than 15.5 years; n = 67). In this subgroup, a high QWI score appears to intensify the negative impact of long-term workload and night work on nutritional health risk.

In contrast, among midwives with 17.5 years or less of professional experience (n = 298; mean age = 29.52 ± 5.05 years; median = 28; range = 24–55), the QWI score alone emerged as the strongest predictor—particularly among individuals with more than 3.75 years of work experience (n = 266), regardless of the number of years worked during night shifts. This finding suggests that even in the early stages of a midwifery career, perceived workload is a critical determinant of stress-related health vulnerabilities.

Age and Work Experience

Our findings indicate that having more than 17.5 years of professional experience is the strongest predictor of nutrition-related health risks among midwives. Notably, midwives in this subgroup had a mean age of 51.13 ± 5.24 years (median = 51.5; range = 41–65), which closely aligns with the national average age of Polish midwives (51.4 years) [

45]. This correspondence suggests that a substantial portion of the national midwifery workforce may already fall into the highest-risk category, owing to both age and length of service.

Although the overall mean age in our study population was younger (34.0 ± 10.06 years), and the median work experience was only 5 years, the results clearly indicate that nutritional vulnerability increases with cumulative occupational exposure. Within the high-risk subgroup, two key factors—years worked during night shifts and overall QWI score—emerged as particularly strong predictors, especially among those with over 15.5 years of night shift experience.

Prolonged exposure to such conditions likely contributes to chronic occupational stress and emotional fatigue, which may promote maladaptive coping strategies such as irregular eating patterns, emotional eating, or increased reliance on calorie-dense, nutrient-poor convenience foods [

44]. These behaviors may be further intensified by age-related physiological changes, including a natural decline in metabolic rate and hormonal fluctuations during perimenopause and menopause, both of which are associated with increased weight gain and elevated BMI—particularly in the absence of regular physical activity and a balanced diet [

46,

47].

Shift Work

The adverse effects of shift work on both physical and mental health are well-documented. Research by Geiger-Brown and colleagues found that shift and night work significantly increase sleepiness at the end of shifts [

48] and lead to disrupted sleep cycles [

49]. The specific impact of shift work may vary depending on whether the schedule is fixed or rotational. Permanent night shifts have been associated with a higher incidence of long-term sick leave when compared to exclusive day shifts [

50], while rotating shifts have been linked to acute fatigue, increased error rates, and elevated alcohol consumption [

6].

In our study, the second most influential predictor of nutritional health risk was the cumulative number of years spent working night shifts. This may be partially explained by evidence showing that nurses and midwives working night shifts tend to consume more total calories, fats, carbohydrates, and sugars than their daytime counterparts. This pattern was observed in a Polish study by Peplonska et al. [

51], as well as in a large U.S. cohort study of nurses (NHS II) [

52].

Furthermore, a study on a group of Lebanese nurses indicated that night shift work affects eating habits and food choices, leading to unhealthy dietary patterns [

9]. Night shift work has also been shown to influence dietary behaviors among healthcare professionals, leading to higher meal frequency and lower overall diet quality. Night shift workers tend to consume more snacks and fried foods high in saturated fats while consuming fewer fruits and vegetables compared to their day-shift counterparts [

7,

39]. These individuals also tend to extend their daily eating window, leading to increased caloric intake over a 24-hour period [

53]. Such disruptions in eating behavior can elevate the risk of metabolic disorders and other health complications.

Moreover,a meta-analysis by Sun et al. further confirmed the association between night shift work and increased risk of overweight and obesity [

54]. Similarly, findings from Lowden et al. demonstrated that shift workers are more susceptible than daytime workers to a wide range of health conditions, including obesity, cardiovascular disease, gastrointestinal problems, impaired glycemic control, and metabolic syndrome. While these conditions are linked in part to irregular diet and meal timing, other contributing factors include psychosocial stress, disrupted circadian rhythms, chronic sleep deprivation, insufficient physical activity, and limited recovery time [

55].

Future Directions

Future studies should explore additional factors such as lifestyle, eating habits, coping mechanisms, and social support to gain a more comprehensive understanding of the mechanisms contributing to nutrition-related health risks among midwives. Longitudinal studies could further clarify how prolonged exposure to occupational stress impacts eating behaviors over time and assess the effectiveness of workplace interventions aimed at reducing nutrition-related risks. By addressing these gaps, future investigations may contribute to the development of evidence-based strategies that enhance both the personal well-being of midwives and the quality of care provided to women and newborns.

Limitations

This study focused exclusively on variables related to workload intensity. Importantly, it did not incorporate direct measures of work-related psychological stress, which may also play a significant role in the development of disordered eating behaviors.

Despite the important contributions of this research, several limitations must be acknowledged. The reliance on self-reported instruments (EAT-26 and QWI) introduces the possibility of response bias, particularly given the sensitive nature of the questions. Moreover, the study’s focus on a specific professional group—midwives—may limit the generalizability of the findings to other healthcare workers.

Another limitation concerns the interpretation of BMI as a risk factor for eating disorders. The EAT-26 questionnaire references BMI only in the context of underweight, without providing a standardized threshold for defining “extremely underweight” in adults. Additionally, the tool does not capture the complex bidirectional relationship between higher BMI and disordered eating behaviors, including conditions such as binge eating disorder.

5. Conclusions

Our findings underscore the significant influence of workload intensity and cumulative professional experience on the risk of eating disorders among midwives. The physically and emotionally demanding nature of the profession—coupled with irregular work schedules and elevated levels of occupational stress—appears to contribute meaningfully to the development of disordered eating behaviors.

In light of these challenges, there is an urgent need for the implementation of workplace interventions that address both occupational stress and nutrition-related health risks. Recommended strategies include optimizing work schedules to enhance work-life balance, implementing evidence-based stress management programs, and delivering targeted nutritional education that addresses the specific challenges associated with shift work and high workload. Additionally, access to psychological support services, routine screening for disordered eating behaviors, and the cultivation of a supportive and health-promoting work environment may help to mitigate the adverse effects of working in this profession.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Aleksandra Łopatkiewicz and Olga Barbarska; Data curation, Iwona Kiersnowska and Gabriel Pesta; Formal analysis, Iwona Kiersnowska; Investigation, Lucyna Kwiećkowska; Methodology, Aleksandra Łopatkiewicz, Olga Barbarska and Iwona Kiersnowska; Project administration, Aleksandra Łopatkiewicz and Edyta Krzych-Fałta; Resources, Gabriel Pesta; Supervision, Edyta Krzych-Fałta; Validation, Aleksandra Łopatkiewicz, Olga Barbarska and Iwona Kiersnowska; Visualization, Gabriel Pesta and Lucyna Kwiećkowska; Writing – original draft, Aleksandra Łopatkiewicz and Olga Barbarska; Writing – review & editing, Iwona Kiersnowska, Lucyna Kwiećkowska and Edyta Krzych-Fałta.

Funding

This research received no external funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Institutional Review Board at the Medical University of Warsaw under approval number AKBE/104/2025 and date of approval 17/03/2025).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

AUC – Area Under the Curve

BED – Binge Eating Disorder

BMI – Body Mass Index

C&RT – Classification and Regression Tree

DSM-5 – Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5th Edition

EAT-26 – Eating Attitudes Test-26

ED – Eating Disorder

ICD-11 – International Classification of Diseases, 11th Revision

NHANES III – Third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey

QWI – Quantitative Workload Inventory

USA – United States of America

WHO – World Health Organization

References

- Hansson M, Dencker A, Lundgren I, Carlsson IM, Eriksson M, Hensing G. Job satisfaction in midwives and its association with organisational and psychosocial factors at work: a nation-wide, cross-sectional study. BMC Health Services Research 2022, 22, 436. [Google Scholar]

- Foster W, McKellar L, Fleet JA, Sweet L. Exploring moral distress in Australian midwifery practice. Women Birth 2022, 35, 349–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Albendín-García L, Suleiman-Martos N, Cañadas-De la Fuente GA, Ramírez-Baena L, Gómez-Urquiza JL, De la Fuente-Solana EI. Prevalence, Related Factors, and Levels of Burnout Among Midwives: A Systematic Review. Journal of Midwifery & Women's Health 2021, 66, 24–44. [Google Scholar]

- Hildingsson I, Fahlbeck H, Larsson B, Johansson M. Increasing levels of burnout in Swedish midwives - A ten-year comparative study. Women Birth 2024, 37, 325–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siegel JA, Sawyer KB. Eating Disorders in the Workplace: A Qualitative Investigation of Women’s Experiences. Psychology of Women Quarterly 2019, 43, 37–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ejebu OZ, Dall’Ora C, Griffiths P. Nurses’ experiences and preferences around shift patterns: A scoping review. PloS One 2021, 16, e0256300. [Google Scholar]

- Navruz-Varlı S, Mortaş H. Shift Work, Shifted Diets: An Observational Follow-Up Study on Diet Quality and Sus-tainability among Healthcare Workers on Night Shifts. Nutrients 2024, 16, 2404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang Q, Chair SY, Lo SHS, Chau JPC, Schwade M, Zhao X. Association between shift work and obesity among nurses: A systematic review and meta-analysis. International Journal of Nursing Studies 2020, 112, 103757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Samhat Z, Attieh R, Sacre Y. Relationship between night shift work, eating habits and BMI among nurses in Leb-anon. BMC Nursing 2020, 19, 25. [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders: Fifth Edition Text Revision DSM-5-TRTM. American Psychiatric Association Publishing 2022.

- World Health Organization. ICD-11 Available online:. Available online: https://icd.who.int/en (accessed on 28 March 2025).

- Ward ZJ, Willett WC, Hu FB, Pacheco LS, Long MW, Gortmaker SL. Excess mortality associated with elevated body weight in the USA by state and demographic subgroup: A modelling study. eClinicalMedicine 2022, 48, 101429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Golubnitschaja O, Liskova A, Koklesova L, Samec M, Biringer K, Büsselberg D, et al. Caution, “normal” BMI: health risks associated with potentially masked individual underweight—EPMA Position Paper 2021. EPMA J. 2021, 12, 243–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibson D, Watters A, Cost J, Mascolo M, Mehler PS. Extreme anorexia nervosa: medical findings, outcomes, and inferences from a retrospective cohort. Journal of Eating Disorders 2020, 8, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McCuen-Wurst C, Ruggieri M, Allison KC. Disordered eating and obesity: associations between binge-eating dis-order, night-eating syndrome, and weight-related comorbidities. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences 2018, 1411, 96–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fekih-Romdhane F, Daher-Nashif S, Alhuwailah AH, Al Gahtani HMS, Hubail SA, Shuwiekh HAM, et al. The prevalence of feeding and eating disorders symptomology in medical students: an updated systematic review, me-ta-analysis, and meta-regression. Eating and Weight Disorders - Studies on Anorexia. Bulimia and Obesity 2022, 27, 1991–2010. [Google Scholar]

- Szweda S, Thorne P. The prevalence of eating disorders in female health care students. Occupational Medicine 2002, 52, 113–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mhasawade V, Zhao Y, Chunara R. Machine learning and algorithmic fairness in public and population health. Nature Machine Intelligence 2021, 3, 659–666. [CrossRef]

- Garner DM, Olmsted MP, Bohr Y, Garfinkel PE. The eating attitudes test: psychometric features and clinical corre-lates. Psychological Medicine 1982, 12, 871–878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rogoza R, Brytek-Matera A, Garner D. Analysis of the EAT-26 in a non-clinical sample. Archives of Psychiatry and Psychotherapy 2016, 18, 54–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spector PE, Jex SM. Development of four self-report measures of job stressors and strain: Interpersonal Conflict at Work Scale, Organizational Constraints Scale, Quantitative Workload Inventory, and Physical Symptoms Inventory. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology 1998, 3, 356–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baka Ł, Bazińska R. Polish adaptation of three self-report measures of job stressors: the Interpersonal Conflict at Work Scale, the Quantitative Workload Inventory and the Organizational Constraints Scale. International Journal of Occupational Safety and Ergonomics 2016, 22, 32–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breiman L, Friedman J, Olshen RA, Stone CJ. Classification and Regression Trees. New York: Chapman and Hall/CRC; 2017: 368.

- World Health Organization. Surveillance of chronic disease risk factors: country-level data and comparable estimates. WHO. Geneva 2005.

- Hall LH, Johnson J, Watt I, Tsipa A, O’Connor DB. Healthcare Staff Wellbeing, Burnout, and Patient Safety: A Sys-tematic Review. PloS One 2016, 11, e0159015. [Google Scholar]

- Seidler A, Thinschmidt M, Deckert S, Then F, Hegewald J, Nieuwenhuijsen K, et al. The role of psychosocial working conditions on burnout and its core component emotional exhaustion - a systematic review. Journal of Occupational Medicine and Toxicology 2014, 9, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cramer E, Hunter B. Relationships between working conditions and emotional wellbeing in midwives. Women Birth 2019, 32, 521–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adriaenssens J, De Gucht V, Maes S. Determinants and prevalence of burnout in emergency nurses: a systematic review of 25 years of research. International Journal of Nursing Studies 2015, 52, 649–661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gruszczyńska M, Skowrońska E, Bator A, Bąk-Sosnowska M. Period of employment, occupational burnout and stress coping strategies among midwives. General Medicine and Health Sciences 2014, 20, 276–281. [Google Scholar]

- Cannizzaro E, Ramaci T, Cirrincione L, Plescia F. Work-Related Stress, Physio-Pathological Mechanisms, and the Influence of Environmental Genetic Factors. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 2019, 16, 4031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blake H, Watkins K, Middleton M, Stanulewicz N. Obesity and Diet Predict Attitudes towards Health Promotion in Pre-Registered Nurses and Midwives. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 2021, 18, 13419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoteit M, Mohsen H, Bookari K, Moussa G, Jurdi N, Yazbeck N. Prevalence, correlates, and gender disparities related to eating disordered behaviors among health science students and healthcare practitioners in Lebanon: Findings of a national cross sectional study. Frontiers in Nutrition 2022, 9, 956310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kinman G, Teoh K, Harriss A. The Mental Health and Wellbeing of Nurses and Midwives in the United Kingdom. The Society of Occupational Medicine. London 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Paul N, Limprecht-Heusner M, Eichenauer J, Scheichenbauer C, Bärnighausen T, Kohler S. Burnout among mid-wives and attitudes toward midwifery: A cross-sectional study from Baden-Württemberg, Germany. European Journal of Midwifery 2022, 6, 46.

- Krzywinski M, Altman N. Classification and regression trees. Nature Methods 2017, 14, 757–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bogossian FE, Hepworth J, Leong GM, Flaws DF, Gibbons KS, Benefer CA, et al. A cross-sectional analysis of patterns of obesity in a cohort of working nurses and midwives in Australia, New Zealand, and the United Kingdom. International Journal of Nursing Studies 2012, 49, 727–738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao I, Bogossian F, Turner C. A cross-sectional analysis of the association between night-only or rotating shift work and overweight/obesity among female nurses and midwives. Journal of Occupational and Environmental Medicine 2012, 54, 834–840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadali UB, Kamal KKBN, Park J, Chew HSJ, Devi MK. The global prevalence of overweight and obesity among nurses: A systematic review and meta-analyses. Journal of Clinical Nursing 2023, 32, 7934–7955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kyle RG, Wills J, Mahoney C, Hoyle L, Kelly M, Atherton IM. Obesity prevalence among healthcare professionals in England: a cross-sectional study using the Health Survey for England. BMJ Open 2017, 7, e018498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- EAT-26. Eating Attitudes Test & Eating Disorder Testing. Available online: https://www.eat-26.com/scoring/ (accessed on 28 March 2025).

- Kuczmarski RJ, Ogden CL, Guo SS, Grummer-Strawn LM, Flegal KM, Mei Z, et al. 2000 CDC Growth Charts for the United States: methods and development. Vital and Health Statistics Series 2002, 246, 1–190.

- Laguna M, Chilimoniuk B, Purc E, Kulczycka K. Job-Related Affective Well-Being in Emergency Medical Dis-patchers: The Role of Workload, Job Autonomy, and Performance Feedback. Advances in Cognitive Psychology 2022, 18, 243–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonçalves S, Cesar Machado B. Disordered Eating and Lifestyle Studies—2nd Edition. Nutrients 2024, 16, 3450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almahmeed MB, Almutawa MA, Naguib YM. The prevalence of and the effect of global stressors on eating disorders among medical students. Frontiers in Psychology 2025, 16, 1507910. [CrossRef]

- Naczelna Izba Pielęgniarek i Położnych. Raport o stanie pielęgniarstwa i położnictwa w Polsce. MedMedia Sp. Z o.o. Warsaw 2023.

- Opoku AA, Abushama M, Konje JC. Obesity and menopause. Best Practice & Research Clinical Obstetrics & Gynaecology 2023, 88, 102348.

- Davis SR, Castelo-Branco C, Chedraui P, Lumsden MA, Nappi RE, Shah D, et al. Understanding weight gain at menopause. Climacteric Journal 2012, 15, 419–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Geiger-Brown J, Rogers VE, Trinkoff AM, Kane RL, Bausell RB, Scharf SM. Sleep, sleepiness, fatigue, and performance of 12-hour-shift nurses. Chronobiology International 2012, 29, 211–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kecklund G, Axelsson J. Health consequences of shift work and insufficient sleep. BMJ 2016, 355, i5210.

- Dall’Ora C, Ball J, Redfern OC, Griffiths P. Night work for hospital nurses and sickness absence: a retrospective study using electronic rostering systems. Chronobiology International 2020, 37, 1357–1364. [CrossRef]

- Peplonska B, Kaluzny P, Trafalska E. Rotating night shift work and nutrition of nurses and midwives. Chronobiology International 2019, 36, 945–954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramin C, Devore EE, Wang W, Pierre-Paul J, Wegrzyn LR, Schernhammer ES. Night shift work at specific age ranges and chronic disease risk factors. Occupational and Environmental Medicine (OEM) 2015, 72, 100–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marot LP, Lopes T do VC, Balieiro LCT, Crispim CA, Moreno CRC. Impact of Nighttime Food Consumption and Feasibility of Fasting during Night Work: A Narrative Review. Nutrients 2023, 15, 2570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun M, Feng W, Wang F, Li P, Li Z, Li M, et al. Meta-analysis on shift work and risks of specific obesity types. Obesity Reviews 2018, 19, 28–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lowden A, Moreno C, Holmbäck U, Lennernäs M, Tucker P. Eating and shift work - effects on habits, metabolism and performance. Scandinavian Journal of Work, Environment & Health 2010, 36, 150–162. [Google Scholar]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).