Submitted:

04 April 2025

Posted:

08 April 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Epidemiology of MCC

4. Etiology and Risk Factors for MCC

4.1. Two (Viral- and UV-Related) Driving Mechanisms for MCC Onset

4.2. The Debate of MCC Cell of Origin

5. Clinical Features and Diagnosis of MCC

6. Staging System (AJCC 8th Edition) and Prognostic Factors

7. Bone and Bone Marrow Metastases in MCC

7.1. Type of Bone Metastases

7.2. Pattern of Metastatic Spread and Association Between Primary MCC and BMs

7.3. Clinical and Demographic Data

7.4. Imaging Features of MCC Across Different Diagnostic Techniques

7.5. Treatment of Metastatic Bone/Bone Marrow MCC

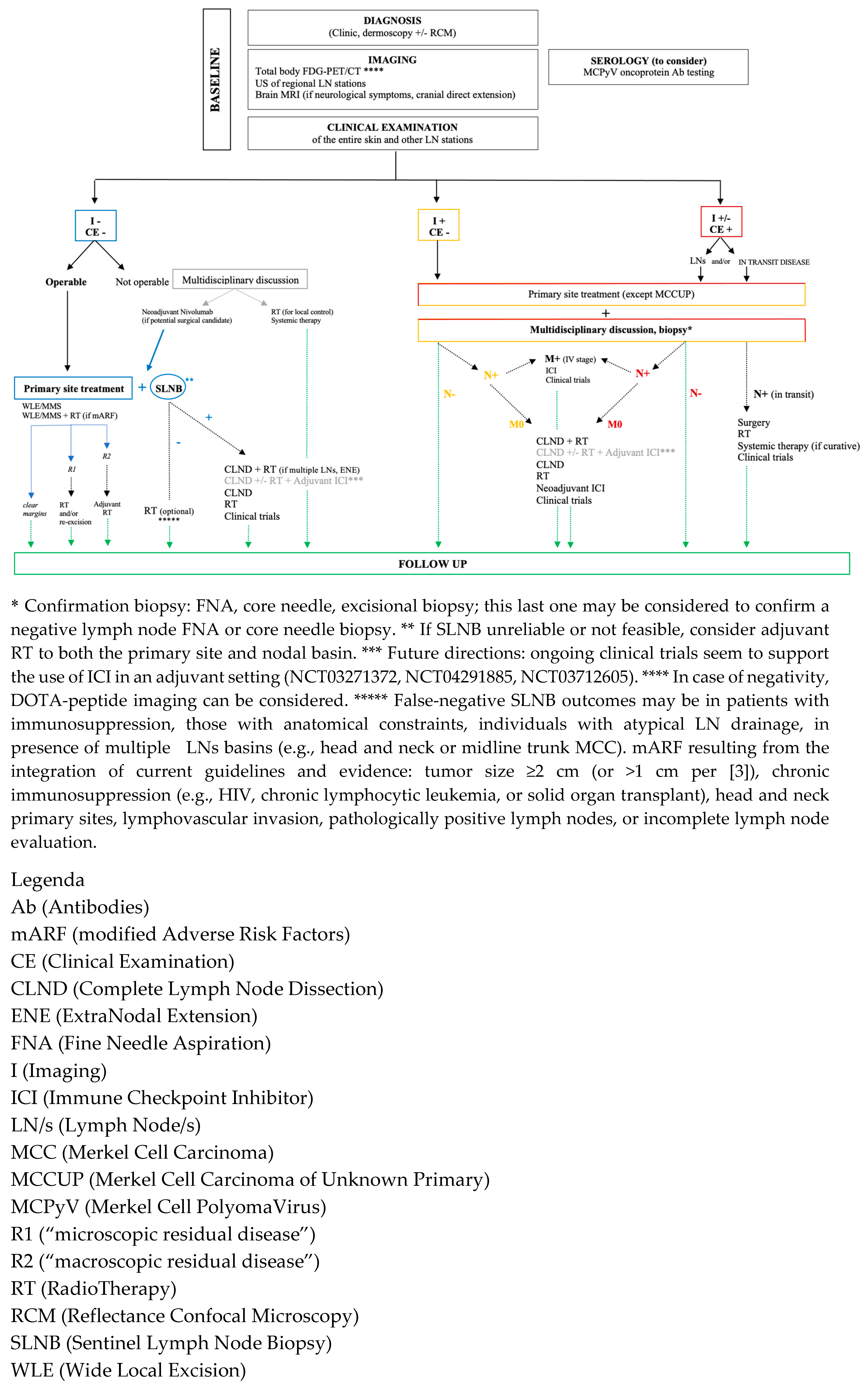

8. MCC General Management

9. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AIDS | Acquired Immunodeficiency Syndrome |

| ATM | Ataxia-Telangiectasia Mutated |

| AKT1 | A serine/threonine kinase |

| ARID1 | AT-Rich Interactive Domain-Containing Protein 1 |

| ASXL1 | Additional Sex Combs-Like 1 |

| BCOR | BCL6 Corepressor |

| BRCA1/2 | Breast Cancer 1/2 |

| DNA | Deoxyribonucleic Acid |

| DOTA | 1,4,7,10-Tetraazacyclododecane-1,4,7,10-tetraacetic acid |

| EMA | European Medicines Agency |

| FAT1 | FAT Atypical Cadherin 1 |

| FDA | Food and Drug Administration |

| HRAS | Harvey Rat Sarcoma Viral Oncogene Homolog |

| HIV | Human Immunodeficiency Virus |

| HR | Hazard Ratio |

| ICI | Immune Checkpoint Inhibitor |

| IQR | Interquartile Range |

| JAK-STAT | Janus Kinase-Signal Transducer and Activator of Transcription |

| KMT2 | Lysine Methyltransferase 2 |

| MAPK | Mitogen-Activated Protein Kinase |

| MSH2 | MutS Homolog 2 |

| NCCN | National Comprehensive Cancer Network |

| NF1 | Neurofibromin 1 |

| NOTCH1 | Notch homolog 1 |

| PAX5 | Paired Box 5 |

| Piezo2 | Piezo-type mechanosensitive ion channel component 2 |

| PIK3CA | Phosphatidylinositol-4,5-Bisphosphate 3-Kinase Catalytic Subunit Alpha |

| PI3K | Phosphoinositide 3-Kinase |

| SMARCA4 | SWI/SNF Related, Matrix Associated, Actin Dependent Regulator of Chromatin Subfamily A, Member 4 |

| STIR | Short Tau Inversion Recovery |

| TdT | Terminal deoxynucleotidyl Transferase |

| VP1 | Viral Protein 1 |

References

- Dika E, Pellegrini C, Lambertini M, Patrizi A, Ventura A, Baraldi C, Cardelli L, Mussi M, Fargnoli MC. Merkel cell carcinoma: an updated overview of clinico-pathological aspects, molecular genetics and therapy. Eur J Dermatol. 2021 Dec 1;31(6):691-701. [CrossRef]

- Schmults CD, Blitzblau R, Aasi SZ, Alam M, Amini A, Bibee K, Bolotin D, Bordeaux J, Chen PL, Contreras CM, et al. NCCN Guidelines Insights: Merkel Cell Carcinoma, Version 1.2024. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2024 Jan;22(1D):e240002.

- Lugowska I, Becker JC, Ascierto PA, Veness M, Blom A, Lebbe C, Migliano E, Hamming-Vrieze O, Goebeler M, Kneitz H, et al. ESMO-EURACAN Clinical Practice Guideline for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Merkel cell carcinoma: ESMO Open. 2024 May;9(5):102977.

- Gauci ML, Aristei C, Becker JC, Blom A, Bataille V, Dreno B, Del Marmol V, Forsea AM, Fargnoli MC, Grob JJ, et al. Diagnosis and treatment of Merkel cell carcinoma: European consensus-based interdisciplinary guideline - Update 2022. Eur J Cancer. 2022 Aug;171:203-231. [CrossRef]

- SEER*Explorer: An interactive website for SEER cancer statistics [Internet]. Surveillance Research Program, National Cancer Institute. Accessed at https://seer.cancer.gov/explorer/ on December 23, 2024.

- Lewis CW, Qazi J, Hippe DS, Lachance K, Thomas H, Cook MM, Juhlin I, Singh N, Thuesmunn Z, Takagishi SR, et al. Patterns of distant metastases in 215 Merkel cell carcinoma patients: Implications for prognosis and surveillance. Cancer Med. 2020 Feb;9(4):1374-1382. [CrossRef]

- Kim EY, Liu M, Giobbie-Hurder A, Bahar F, Khaddour K, Silk AW, Thakuria M. Patterns of initial distant metastases in 151 patients undergoing surveillance for treated Merkel cell carcinoma. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2024 Jun;38(6):1202-1212. [CrossRef]

- Paulson KG, Park SY, Vandeven NA, Lachance K, Thomas H, Chapuis AG, Harms KL, Thompson JA, Bhatia S, Stang A, et al. Merkel cell carcinoma: Current US incidence and projected increases based on changing demographics. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2018 Mar;78(3):457-463.e2. [CrossRef]

- Li Z, Ji W, Hu Q, Zhu P, Jin Y, Duan G. Current status of Merkel cell carcinoma: Epidemiology, pathogenesis and prognostic factors. Vol. 599, Virology. Academic Press Inc.; 2024. [CrossRef]

- Mohsen ST, Price EL, Chan AW, Hanna TP, Limacher JJ, Nessim C, Shiers JE, Tron V, Wright FC, Drucker AM. Incidence, mortality and survival of Merkel cell carcinoma: a systematic review of population-based studies. Br J Dermatol. 2024 May 17;190(6):811-824. [CrossRef]

- Becker JC SASDUS. Merkel Cell Carcinoma: Integrating Epidemiology, Immunology, and Therapeutic Updates. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2024;25(4):541–57.

- Paulson KG, Nghiem P. One in a hundred million: Merkel cell carcinoma in pediatric and young adult patients is rare but more likely to present at advanced stages based on US registry data. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019 Jun 1;80(6):1758–60. [CrossRef]

- Stang A, Becker JC, Nghiem P, Ferlay J. The association between geographic location and incidence of Merkel cell carcinoma in comparison to melanoma: An international assessment. Eur J Cancer. 2018 May 1;94:47–60. [CrossRef]

- Scotti B, Vaccari S, Maltoni L, Robuffo S, Veronesi G, Dika E. Clinic and dermoscopy of genital basal cell carcinomas (gBCCs): a retrospective analysis among 169 patients referred with genital skin neoplasms. Arch Dermatol Res. 2024 May 31;316(6):307. [CrossRef]

- Rapparini L, Alessandrini A, Scotti B, Dika E. Invasive penile glans Squamous Cell Carcinoma (peSCC) and Reflectance Confocal Microscopy (RCM): is it a valuable alternative to histopathology? Skin Research and Technology. John Wiley and Sons Inc; 2024.

- Montano-Loza AJ, Rodríguez-Perálvarez ML, Pageaux GP, Sanchez-Fueyo A, Feng S. Liver transplantation immunology: Immunosuppression, rejection, and immunomodulation. Journal of Hepatology. 2023. p. 1199–215. [CrossRef]

- Jallah BP, Kuypers DRJ. Impact of Immunosenescence in Older Kidney Transplant Recipients: Associated Clinical Outcomes and Possible Risk Stratification for Immunosuppression Reduction. Drugs and Aging. 2024. p. 219–38. [CrossRef]

- Feng H, Shuda M, Chang Y, Moore PS. Clonal integration of a polyomavirus in human Merkel cell carcinoma. Science. 2008 Feb 22;319(5866):1096–100. [CrossRef]

- Tolstov YL, Pastrana DV, Feng H, Becker JC, Jenkins FJ, Moschos S, Chang Y, Buck CB, Moore PS. Human Merkel cell polyomavirus infection II. MCV is a common human infection that can be detected by conformational capsid epitope immunoassays. Int J Cancer. 2009 Sep 15;125(6):1250-6. [CrossRef]

- Tsai KY. The Origins of Merkel Cell Carcinoma: Defining Paths to the Neuroendocrine Phenotype. Vol. 142, Journal of Investigative Dermatology. 2022. p. 507–9. [CrossRef]

- Nirenberg A, Steinman H, Dixon J, Dixon A. Merkel cell carcinoma update: the case for two tumours. Vol. 34, Journal of the European Academy of Dermatology and Venereology. 2020. p. 1425–31.

- Kervarrec T, Samimi M, Guyétant S, Sarma B, Chéret J, Blanchard E, Berthon P, Schrama D, Houben R, Touzé A. Histogenesis of Merkel Cell Carcinoma: A Comprehensive Review. Front Oncol. 2019 Jun 10;9:451. [CrossRef]

- Samimi M, Kervarrec T, Touze A. Immunobiology of Merkel cell carcinoma. Current Opinion in Oncology. 2020. p. 114–21.

- Miller RW, Rabkin CS. Merkel cell carcinoma and melanoma: etiological similarities and differences. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 1999 Feb;8(2):153-8.

- Howard RA, Dores GM, Curtis RE, Anderson WF, Travis LB. Merkel cell carcinoma and multiple primary cancers. Cancer Epidemiology Biomarkers and Prevention. 2006 Aug;15(8):1545–9. [CrossRef]

- Goessling W, McKee PH, Mayer RJ. Merkel cell carcinoma. J Clin Oncol. 2002 Jan 15;20(2):588-98.

- Wong SQ, Waldeck K, Vergara IA, Schröder J, Madore J, Wilmott JS, Colebatch AJ, De Paoli-Iseppi R, Li J, Lupat R, et al. UV-Associated Mutations Underlie the Etiology of MCV-Negative Merkel Cell Carcinomas. Cancer Res. 2015 Dec 15;75(24):5228-34.

- Sahi H, Savola S, Sihto H, Koljonen V, Bohling T, Knuutila S. RB1 gene in Merkel cell carcinoma: Hypermethylation in all tumors and concurrent heterozygous deletions in the polyomavirus-negative subgroup. APMIS. 2014 Dec 1;122(12):1157–66. [CrossRef]

- Pedersen EA, Verhaegen ME, Joseph MK, Harms KL, Harms PW. Merkel cell carcinoma: updates in tumor biology, emerging therapies, and preclinical models. Frontiers in Oncology. 2024. [CrossRef]

- Iwasaki T, Hayashi K, Matsushita M, Nonaka D, Kohashi K, Kuwamoto S, Umekita Y, Oda Y. Merkel cell polyomavirus-negative Merkel cell carcinoma is associated with JAK-STAT and MEK-ERK pathway activation. Cancer Sci. 2022 Jan;113(1):251-260. [CrossRef]

- Harms PW, Verhaegen ME, Hu K, Hrycaj SM, Chan MP, Liu CJ, Grachtchouk M, Patel RM, Udager AM, Dlugosz AA. Genomic evidence suggests that cutaneous neuroendocrine carcinomas can arise from squamous dysplastic precursors. Mod Pathol. 2022 Apr;35(4):506-514. [CrossRef]

- Kervarrec T, Appenzeller S, Samimi M, Sarma B, Sarosi EM, Berthon P, Le Corre Y, Hainaut-Wierzbicka E, Blom A, Benethon N, et al. Merkel Cell Polyomavirus‒Negative Merkel Cell Carcinoma Originating from In Situ Squamous Cell Carcinoma: A Keratinocytic Tumor with Neuroendocrine Differentiation. J Invest Dermatol. 2022 Mar;142(3 Pt A):516-527. [CrossRef]

- Ríos-Viñuela E, Mayo-Martínez F, Nagore E, Millan-Esteban D, Requena C, Sanmartín O, Llombart B. Combined Merkel Cell Carcinoma and Squamous Cell Carcinoma: A Systematic Review. Cancers. 2024 Jan 18;16(2):411. [CrossRef]

- Reisinger DM, Shiffer JD, Cognetta AB, Chang Y, Moore PS. Lack of evidence for basal or squamous cell carcinoma infection with Merkel cell polyomavirus in immunocompetent patients with Merkel cell carcinoma. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2010 Sep;63(3):400–3. [CrossRef]

- DeCaprio JA. Molecular Pathogenesis of Merkel Cell Carcinoma. Annu Rev Pathol. 2021 Jan 24;16:69-91. [CrossRef]

- Engels EA, Frisch M, Goedert JJ, Biggar RJ, Miller RW. Merkel cell carcinoma and HIV infection. Lancet. 2002 Feb 9;359(9305):497-8. [CrossRef]

- An KP, Ratner D. Merkel cell carcinoma in the setting of HIV infection. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2001;45(2):309–12. [CrossRef]

- Harms PW, Harms KL, Moore PS, DeCaprio JA, Nghiem P, Wong MKK, Brownell I; International Workshop on Merkel Cell Carcinoma Research (IWMCC) Working Group. The biology and treatment of Merkel cell carcinoma: current understanding and research priorities. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2018 Dec;15(12):763-776. [CrossRef]

- Czapiewski P, Biernat W. Merkel cell carcinoma - Recent advances in the biology, diagnostics and treatment. International Journal of Biochemistry and Cell Biology. 2014. p. 536–46.

- Sunshine JC, Jahchan NS, Sage J, Choi J. Are there multiple cells of origin of Merkel cell carcinoma? Oncogene. 2018. p. 1409–16. [CrossRef]

- Tilling T, Moll I. Which Are the Cells of Origin in Merkel Cell Carcinoma? J Skin Cancer. 2012;2012:1–6.

- Ikeda R, Cha M, Ling J, Jia Z, Coyle D, Gu JG. Merkel cells transduce and encode tactile stimuli to drive aβ-Afferent impulses. Cell. 2014 Apr 24;157(3):664–75. [CrossRef]

- Harms PW, Patel RM, Verhaegen ME, Giordano TJ, Nash KT, Johnson CN, Daignault S, Thomas DG, Gudjonsson JE, Elder JT, et al. Distinct gene expression profiles of viral- and nonviral-associated merkel cell carcinoma revealed by transcriptome analysis. J Invest Dermatol. 2013 Apr;133(4):936-45. [CrossRef]

- Van Keymeulen A, Mascre G, Youseff KK, Harel I, Michaux C, De Geest N, Szpalski C, Achouri Y, Bloch W, Hassan BA, et al. Epidermal progenitors give rise to Merkel cells during embryonic development and adult homeostasis. J Cell Biol. 2009 Oct 5;187(1):91-100.

- Gambichler T, Mohtezebsade S, Wieland U, Silling S, Höh AK, Dreißigacker M, Schaller J, Schulze HJ, Oellig F, Kreuter A, et al. Prognostic relevance of high atonal homolog-1 expression in Merkel cell carcinoma. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol. 2017 Jan;143(1):43-49. [CrossRef]

- Fradette J, Godbout MJ, Michel M, Germain L. Localization of Merkel cells at hairless and hairy human skin sites using keratin 18. Biochem Cell Biol. 1995 Sep-Oct;73(9-10):635-9. [CrossRef]

- Lyu J, Liu S, Lu Y. A case of multiple recurrent facial Merkel cell carcinomas: Treatment and imaging findings. Asian Journal of Surgery. 2023. p. 2548–9. [CrossRef]

- Shuda M, Guastafierro A, Geng X, Shuda Y, Ostrowski SM, Lukianov S, Jenkins FJ, Honda K, Maricich SM, Moore PS, et al. Merkel Cell Polyomavirus Small T Antigen Induces Cancer and Embryonic Merkel Cell Proliferation in a Transgenic Mouse Model. PLoS One. 2015 Nov 6;10(11):e0142329. [CrossRef]

- González-Vela MDC, Curiel-Olmo S, Derdak S, Beltran S, Santibañez M, Martínez N, Castillo-Trujillo A, Gut M, Sánchez-Pacheco R, Almaraz C, et al. Shared Oncogenic Pathways Implicated in Both Virus-Positive and UV-Induced Merkel Cell Carcinomas. J Invest Dermatol. 2017 Jan;137(1):197-206. [CrossRef]

- Hesbacher S, Pfitzer L, Wiedorfer K, Angermeyer S, Borst A, Haferkamp S, Scholz CJ, Wobser M, Schrama D, Houben R. RB1 is the crucial target of the Merkel cell polyomavirus Large T antigen in Merkel cell carcinoma cells. Oncotarget. 2016 May 31;7(22):32956-68. [CrossRef]

- Harms PW, Vats P, Verhaegen ME, Robinson DR, Wu YM, Dhanasekaran SM, Palanisamy N, Siddiqui J, Cao X, Su F, et al. The Distinctive Mutational Spectra of Polyomavirus-Negative Merkel Cell Carcinoma. Cancer Res. 2015 Sep 15;75(18):3720-3727.

- Shamir ER, Devine WP, Pekmezci M, Umetsu SE, Krings G, Federman S, Cho SJ, Saunders TA, Jen KY, Bergsland E, et al. Identification of high-risk human papillomavirus and Rb/E2F pathway genomic alterations in mutually exclusive subsets of colorectal neuroendocrine carcinoma. Mod Pathol. 2019 Feb;32(2):290-305. [CrossRef]

- Meder L, König K, Ozretić L, Schultheis AM, Ueckeroth F, Ade CP, Albus K, Boehm D, Rommerscheidt-Fuss U, Florin A, et al. NOTCH, ASCL1, p53 and RB alterations define an alternative pathway driving neuroendocrine and small cell lung carcinomas. Int J Cancer. 2016 Feb 15;138(4):927-38. [CrossRef]

- Syder AJ, Karam SM, Mills JC, Ippolito JE, Ansari HR, Farook V, Gordon JI. A transgenic mouse model of metastatic carcinoma involving transdifferentiation of a gastric epithelial lineage progenitor to a neuroendocrine phenotype. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004 Mar 30;101(13):4471-6. [CrossRef]

- Haigis K, Sage J, Glickman J, Shafer S, Jacks T. The related retinoblastoma (pRb) and p130 proteins cooperate to regulate homeostasis in the intestinal epithelium. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2006 Jan 6;281(1):638–47. [CrossRef]

- Ostrowski SM, Wright MC, Bolock AM, Geng X, Maricich SM. Ectopic Atoh1 expression drives Merkel cell production in embryonic, postnatal and adult mouse epidermis. Development. 2015 Jul 15;142(14):2533–44.

- Morrison KM, Miesegaes GR, Lumpkin EA, Maricich SM. Mammalian Merkel cells are descended from the epidermal lineage. Dev Biol. 2009 Dec 1;336(1):76–83. [CrossRef]

- Perdigoto CN, Bardot ES, Valdes VJ, Santoriello FJ, Ezhkova E. Embryonic maturation of epidermal merkel cells is controlled by a redundant transcription factor network. Development. 2014 Dec 15;141(24):4690–6. [CrossRef]

- Thibault K. Evidence of an epithelial origin of Merkel cell carcinoma. Mod Pathol. 2022 Apr;35(4):446-448. [CrossRef]

- Park JW, Lee JK, Sheu KM, Wang L, Balanis NG, Nguyen K, Smith BA, Cheng C, Tsai BL, Cheng D, et al. Reprogramming normal human epithelial tissues to a common, lethal neuroendocrine cancer lineage. Science. 2018 Oct 5;362(6410):91-95. [CrossRef]

- Park KS, Liang MC, Raiser DM, Zamponi R, Roach RR, Curtis SJ, Walton Z, Schaffer BE, Roake CM, Zmoos AF, et al. Characterization of the cell of origin for small cell lung cancer. Cell Cycle. 2011 Aug 15;10(16):2806-15. [CrossRef]

- Liu W, Yang R, Payne AS, Schowalter RM, Spurgeon ME, Lambert PF, Xu X, Buck CB, You J. Identifying the Target Cells and Mechanisms of Merkel Cell Polyomavirus Infection. Cell Host Microbe. 2016 Jun 8;19(6):775-87. [CrossRef]

- Liu W, Krump NA, MacDonald M, You J. Merkel Cell Polyomavirus Infection of Animal Dermal Fibroblasts. J Virol. 2018 Feb 15;92(4). [CrossRef]

- Takahashi K, Yamanaka S. Induction of Pluripotent Stem Cells from Mouse Embryonic and Adult Fibroblast Cultures by Defined Factors. Cell. 2006 Aug 25;126(4):663–76.

- Hausen A Zur, Rennspiess D, Winnepenninckx V, Speel EJ, Kurz AK. Early B-Cell differentiation in merkel cell carcinomas: Clues to cellular ancestry. Cancer Research. 2013. p. 4982–7. [CrossRef]

- Scotti B, Cama E, Venturi F, Veronesi G, Dika E. Clinical and dermoscopic features of Merkel cell carcinoma: insights from 16 cases, including two reflectance confocal microscopy evaluation and the identification of four representative MCC subtypes. Arch Dermatol Res. 2025 Mar 17;317(1):587. [CrossRef]

- Suárez AL, Louis P, Kitts J, Busam K, Myskowski PL, Wong RJ, Chen CS, Spencer P, Lacouture M, Pulitzer MP. Clinical and dermoscopic features of combined cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma (SCC)/neuroendocrine [Merkel cell] carcinoma (MCC). J Am Acad Dermatol. 2015 Dec;73(6):968-75. [CrossRef]

- McGowan MA, Helm MF, Tarbox MB. Squamous cell carcinoma in situ overlying merkel cell carcinoma. J Cutan Med Surg. 2016 Nov 1;20(6):563–6. [CrossRef]

- Chen X, Song X, Huang H, Zhang L, Song Z, Yang X, Lei S, Zhai Z. Merkel cell carcinoma overlapping Bowen's disease: two cases report and literature review. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol. 2024 Apr 26;150(4):217. [CrossRef]

- Hayter JP, Jacques K, James KA. Merkel cell tumour of the cheek. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1991 Apr;29(2):114-6. [CrossRef]

- Mir R, Sciubba JJ, Bhuiya TA, Blomquist K, Zelig D, Friedman E. Merkel cell carcinoma arising in the oral mucosa. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1988 Jan;65(1):71-5. [CrossRef]

- Yom SS, Rosenthal DI, El-Naggar AK, Kies MS, Hessel AC. Merkel cell carcinoma of the tongue and head and neck oral mucosal sites. Oral Surgery, Oral Medicine, Oral Pathology, Oral Radiology and Endodontology. 2006. p. 761–8. [CrossRef]

- Longo F, Califano L, Mangone GM, Errico ME. Neuroendocrine (Merkel cell) carcinoma of the oral mucosa: Report of a case with immunohistochemical study and review of the literature. Journal of Oral Pathology and Medicine. 1999;28(2):88–91. [CrossRef]

- de Arruda JAA, Mesquita RA, Canedo NHS, Agostini M, Abrahão AC, de Andrade BAB, Romañach MJ. Merkel cell carcinoma of the lower lip: A case report and literature review. Oral Oncol. 2021 Feb;113:105019. [CrossRef]

- Islam MN, Chehal H, Smith MH, Islam S, Bhattacharyya I. Merkel Cell Carcinoma of the Buccal Mucosa and Lower Lip. Head Neck Pathol. 2018 Jun 1;12(2):279–85. [CrossRef]

- Baker P, Alguacil-Garcia A. Moderately differentiated neuroendocrine carcinoma in the floor of the mouth: a case report. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1999 Sep;57(9):1143-7. [CrossRef]

- Prabhu S, Smitha RS, Punnya VA. Merkel cell carcinoma of the alveolar mucosa in a young adult: A rare case report. British Journal of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery. 2010 Jan;48(1):48–50. [CrossRef]

- Inoue T, Shimono M, Takano N, Saito C, Tanaka Y. Merkel cell carcinoma of palatal mucosa in a young adult: immunohistochemical and ultrastructural features. Oral Oncol. 1997 May;33(3):226-9. [CrossRef]

- Roy S, Das I, Nandi A, Roy R. Primary Merkel cell carcinoma of the oral mucosa in a young adult male: Report of a rare case. Indian J Pathol Microbiol. 2015 Apr 1;58(2):214–6. [CrossRef]

- Tomic S, Warner TF, Messing E, Wilding G. Penile Merkel cell carcinoma. Urology. 1995 Jun;45(6):1062-5. [CrossRef]

- Best TJ, Metcalfe JB, Moore RB, Nguyen GK. Merkel cell carcinoma of the scrotum. Ann Plast Surg. 1994 Jul;33(1):83-5.

- Cwynar M, Chmielik E, Cwynar G, Ptak P, Kowalczyk K. Vulvar Merkel cell carcinoma combined with squamous cell carcinoma of the vulva. Ginekol Pol. 2024;95(6):502–3. [CrossRef]

- Nguyen AH, Tahseen AI, Vaudreuil AM, Caponetti GC, Huerter CJ. Clinical features and treatment of vulvar Merkel cell carcinoma: a systematic review. Gynecol Oncol Res Pract. 2017 Dec;4(1). [CrossRef]

- Koumaki D, Evangelou G, Katoulis AC, Apalla Z, Lallas A, Papadakis M, Gregoriou S, Lazaridou E, Krasagakis K. Dermoscopic characteristics of Merkel cell carcinoma. BMC Cancer. 2024 Jul 1;24(1):785. [CrossRef]

- Dalle S, Parmentier L, Moscarella E, Phan A, Argenziano G, Thomas L. Dermoscopy of merkel cell carcinoma. Dermatology. 2012 May;224(2):140–4.

- Ho J, Collie CJ. What’s new in dermatopathology 2023: WHO 5th edition updates. Journal of Pathology and Translational Medicine. 2023. p. 337–40. [CrossRef]

- Ronen S, Czaja RC, Ronen N, Pantazis CG, Iczkowski KA. Small Cell Variant of Metastatic Melanoma: A Mimicker of Lymphoblastic Leukemia/Lymphoma. Dermatopathology. 2019 Nov 27;231–6. [CrossRef]

- Lewis DJ, Sobanko JF, Etzkorn JR, Shin TM, Giordano CN, McMurray SL, Walker JL, Zhang J, Miller CJ, Higgins HW 2nd. Merkel Cell Carcinoma. Dermatol Clin. 2023 Jan;41(1):101-115.

- Chowdhury S, Kataria SP, Yadav AK. Expression of Neuron-Specific Enolase and Other Neuroendocrine Markers is Correlated with Prognosis and Response to Therapy in Non-Hodgkin Lymphoma. J Lab Physicians. 2022 Dec;14(04):427–34. [CrossRef]

- Bobos M, Hytiroglou P, Kostopoulos I, Karkavelas G, Papadimitriou CS. Immunohistochemical distinction between merkel cell carcinoma and small cell carcinoma of the lung. Am J Dermatopathol. 2006 Apr;28(2):99-104. [CrossRef]

- Kervarrec T, Tallet A, Miquelestorena-Standley E, Houben R, Schrama D, Gambichler T, Berthon P, Le Corre Y, Hainaut-Wierzbicka E, Aubin F, et al. Diagnostic accuracy of a panel of immunohistochemical and molecular markers to distinguish Merkel cell carcinoma from other neuroendocrine carcinomas. Mod Pathol. 2019 Apr;32(4):499-510. [CrossRef]

- Pasternak S, Carter MD, Ly TY, Doucette S, Walsh NM. Immunohistochemical profiles of different subsets of Merkel cell carcinoma. Hum Pathol. 2018 Dec 1;82:232–8. [CrossRef]

- Trinidad CM, Torres-Cabala CA, Prieto VG, Aung PP. Update on eighth edition American Joint Committee on Cancer classification for Merkel cell carcinoma and histopathological parameters that determine prognosis. Journal of Clinical Pathology. 2019. p. 337–40. [CrossRef]

- Hawryluk EB, O'Regan KN, Sheehy N, Guo Y, Dorosario A, Sakellis CG, Jacene HA, Wang LC. Positron emission tomography/computed tomography imaging in Merkel cell carcinoma: a study of 270 scans in 97 patients at the Dana-Farber/Brigham and Women's Cancer Center. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013 Apr;68(4):592-599. [CrossRef]

- O'Sullivan B, Brierley J, Byrd D, Bosman F, Kehoe S, Kossary C, Piñeros M, Van Eycken E, Weir HK, Gospodarowicz M. The TNM classification of malignant tumours-towards common understanding and reasonable expectations. Lancet Oncol. 2017 Jul;18(7):849-851.

- Medina-Franco H, Urist MM, Fiveash J, Heslin MJ, Bland KI, Beenken SW. Multimodality Treatment of Merkel Cell Carcinoma: Case Series and Literature Review of 1024 Cases. 2001.

- Harms KL, Healy MA, Nghiem P, Sober AJ, Johnson TM, Bichakjian CK, Wong SL. Analysis of Prognostic Factors from 9387 Merkel Cell Carcinoma Cases Forms the Basis for the New 8th Edition AJCC Staging System. Ann Surg Oncol. 2016 Oct;23(11):3564-3571. [CrossRef]

- McEvoy AM, Lachance K, Hippe DS, Cahill K, Moshiri Y, Lewis CW, Singh N, Park SY, Thuesmunn Z, Cook MM, et al. Recurrence and Mortality Risk of Merkel Cell Carcinoma by Cancer Stage and Time From Diagnosis. JAMA Dermatol. 2022 Apr 1;158(4):382-389. [CrossRef]

- Pectasides D, Pectasides M, Economopoulos T. Merkel cell cancer of the skin. Annals of Oncology. 2006 Oct;17(10):1489–95. [CrossRef]

- Song Y, Azari FS, Tang R, Shannon AB, Miura JT, Fraker DL, Karakousis GC. Patterns of Metastasis in Merkel Cell Carcinoma. Ann Surg Oncol. 2021 Jan;28(1):519-529. [CrossRef]

- Gonzalez MR, Bryce-Alberti M, Portmann-Baracco A, Castillo-Flores S, Pretell-Mazzini J. Treatment and survival outcomes in metastatic Merkel cell carcinoma: Analysis of 2010 patients from the SEER database. Cancer Treat Res Commun. 2022 Jan 1;33. [CrossRef]

- Moon IJ, Na H, Cho HS, Won CH, Chang SE, Lee MW, Lee WJ. Clinicopathological characteristics and prognosis of Merkel cell carcinoma: a single-center retrospective study in Korea. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol. 2023 Sep;149(12):10065-10074. [CrossRef]

- Bichakjian CK, Olencki T, Aasi SZ, Alam M, Andersen JS, Blitzblau R, Bowen GM, Contreras CM, Daniels GA, Decker R, et al. Merkel Cell Carcinoma, Version 1.2018, NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2018 Jun;16(6):742-774.

- Maloney NJ, Nguyen KA, Bach DQ, Zaba LC. Sites of distant metastasis in Merkel cell carcinoma differ by primary tumor site and are of prognostic significance: A population-based study in the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results database from 2010 to 2016. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2021 Feb;84(2):568-570. [CrossRef]

- Fang J, Xu Q. Differences of osteoblastic bone metastases and osteolytic bone metastases in clinical features and molecular characteristics. Clinical and Translational Oncology. 2015. p. 173–9. [CrossRef]

- Høilund-Carlsen PF, Hess S, Werner TJ, Alavi A. Cancer metastasizes to the bone marrow and not to the bone: time for a paradigm shift! European Journal of Nuclear Medicine and Molecular Imaging. 2018. p. 893–7.

- O’Sullivan GJ. Imaging of bone metastasis: An update. World J Radiol. 2015;7(8):202. [CrossRef]

- Akaike G, Akaike T, Fadl SA, Lachance K, Nghiem P, Behnia F. Imaging of merkel cell carcinoma: What imaging experts should know. Radiographics. 2019 Nov 1;39(7):2069–84. [CrossRef]

- Litofsky NS, Smith TW, Megerian CA. Merkel cell carcinoma of the external auditory canal invading the intracranial compartment. Am J Otolaryngol. 1998 Sep-Oct;19(5):330-4. [CrossRef]

- Barkdull GC, Healy JF, Weisman RA. Intracranial spread of Merkel cell carcinoma through intact skull. Annals of Otology, Rhinology and Laryngology. 2004;113(9):683–7. [CrossRef]

- Xia YJ, Cao DS, Zhao J, Zhu BZ, Xie J. Frequency and prognosis of metastasis to liver, lung, bone and brain from Merkel cell carcinoma. Future Oncology. 2020 Jun 1;16(16):1101–13. [CrossRef]

- Scampa M, Kalbermatten DF, Oranges CM. Demographic and Clinicopathological Factors as Predictors of Lymph Node Metastasis in Merkel Cell Carcinoma: A Population-Based Analysis. J Clin Med. 2023 Mar 1;12(5). [CrossRef]

- Khaddour K, Liu M, Kim EY, Bahar F, Lôbo MM, Giobbie-Hurder A, Silk AW, Thakuria M. Survival outcomes in patients with de novo metastatic Merkel cell carcinoma according to site of metastases. Front Oncol. 2024 Sep 16;14:1444590. [CrossRef]

- Thomas M, Mandal A. An Extremely Rare Case of Metastatic Merkel Carcinoma of the Liver. Cureus. 2021 Nov 17. [CrossRef]

- Kobayashi Y, Nakamura M, Kato H, Morita A. Distant recurrence of Merkel cell carcinoma after spontaneous regression. Journal of Dermatology. 2019. p. e133–4. [CrossRef]

- Payne MM, Rader AE, McCarthy DM, Rodgers WH. Merkel cell carcinoma in a malignant pleural effusion: case report. Cytojournal. 2004 Nov 18;1(1):5. [CrossRef]

- Boghossian V, Owen ID, Nuli B, Xiao PQ. Neuroendocrine (Merkel cell) carcinoma of the retroperitoneum with no identifiable primary site. World J Surg Oncol. 2007 Oct 19;5. [CrossRef]

- Quiroz-Sandoval OA, Cuellar-Hubbe M, Lino-Silva LS, Salcedo-Hernández RA, López-Basave HN, Padilla-Rosciano AE, León-Takahashi AM, Herrera-Gómez Á. Primary retroperitoneal Merkel cell carcinoma: Case report and literature review. Int J Surg Case Rep. 2016;19:21-4. [CrossRef]

- Rossini D, Caponnetto S, Lapadula V, De Filippis L, Del Bene G, Emiliani A, Longo F. Merkel cell carcinoma of the retroperitoneum with no identifiable primary site. Case Rep Oncol Med. 2013;2013:131695. [CrossRef]

- Durastante V, Conte A, Brollo PP, Biddau C, Graziano M, Bresadola V. Merkel Cell Carcinoma with Gastric Metastasis, a Rare Presentation: Case Report and Literature Review. J Gastrointest Cancer. 2023 Mar 1;54(1):309–15.

- Vaiciunaite D, Beddell G, Ivanov N. Merkel cell carcinoma: An aggressive cutaneous carcinoma with rare metastasis to the thyroid gland. BMJ Case Rep. 2019 Apr 1;12(4). [CrossRef]

- Abul-Kasim K, Söderström K, Hallsten L. Extensive central nervous system involvement in Merkel cell carcinoma: A case report and review of the literature. J Med Case Rep. 2011;5. [CrossRef]

- Santandrea G, Borsari S, Filice A, Piana S. Merkel Cell Carcinoma: Mind the Genital Metastatic Sites! Dermatology Practical and Conceptual. Mattioli 1885; 2023.

- Pennisi G, Talacchi A, Tirendi MN, Giordano M, Olivi A. Intradural extramedullary cervical metastasis from Merkel cell carcinoma: a case report and literature review. Chin Neurosurg J. 2022 Dec 2;8(1):38. [CrossRef]

- Leão I, Marinho J, Costa T. Long-term response to avelumab and management of oligoprogression in Merkel cell carcinoma: A case report. World J Clin Cases. 2021 Jun 26;9(18):4829–36. [CrossRef]

- Lentz SR, Krewson L, Zutter MM. Recurrent Neuroendocrine (Merkel Cell) Carcinoma of the Skin Presenting as Marrow Failure in a Man With Systemic Lupus Erythematosus. Medical and Pediatric Oncology. 1993.

- Wang HY, Shabaik AS. Metastatic Merkel cell carcinoma involving the bone marrow with chronic lymphocytic leukemia mimicking Richter transformation. Blood. 2013 Oct 17;122(16):2776. [CrossRef]

- Khan A, Adil S, Estalilla OC, Jubelirer S. Bone marrow involvement with Merkel cell carcinoma. BMJ Case Rep. 2020 Jun 28;13(6). [CrossRef]

- Morris KL, Williams B, Kennedy GA. Images in haematology. Heavy bone marrow involvement with metastatic Merkel cell tumour in an immunosuppressed renal transplant recipient. Br J Haematol. 2005 Jan;128(2):133. [CrossRef]

- Kressin MK, Kim AS. Metastatic Merkel cell carcinoma in the bone marrow of a patient with plasma cell myeloma and therapy-related myelodysplastic syndrome. Int J Clin Exp Pathol. 2012;5(9):1007-12.

- Keow J, Kwan KF, Hedley BD, Hsia CC, Xenocostas A, Chin-Yee B. Merkel cell carcinoma mimicking acute leukemia. Int J Lab Hematol. 2024 Oct 1. [CrossRef]

- Durmus O, Gokoz O, Saglam EA, Ergun EL, Gulseren D. A rare involvement in skin cancer: Merkel cell carcinoma with bone marrow infiltration in a kidney transplant recipient. Clinical Medicine, Journal of the Royal College of Physicians of London. 2023 May 1;23(3):275–7. [CrossRef]

- Nemoto I, Sato-Matsumura KC, Fujita Y, Natsuga K, Ujiie H, Tomita Y, Kato N, Kondo M, Ohnishi K. Leukaemic dissemination of Merkel cell carcinoma in a patient with systemic lupus erythematosus. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2008 May;33(3):270-2. [CrossRef]

- Highland B, Morrow WP, Arispe K, Beaty M, Maracaja D. Merkel Cell Carcinoma With Extensive Bone Marrow Metastasis and Peripheral Blood Involvement: A Case Report With Immunohistochemical and Mutational Studies. Applied Immunohistochemistry and Molecular Morphology. 2024 Sep 1;32(8):382–8. [CrossRef]

- Smadja N, De Gramont A, Gonzalez-Canali G, Louvet C, Wattel E, Krulik M. Cytogenetic Study in a Bone Marrow Metastatic Merkel Cell Carcinoma. 1991. [CrossRef]

- Le Gall-Ianotto C, Coquart N, Ianotto JC, Guillerm G, Grall C, Quintin-Roue I, Marion V, Greco M, Berthou C, Misery L. Pancytopaenia secondary to bone marrow dissemination of Merkel cell carcinoma in a patient with Waldenström macroglobulinaemia. Eur J Dermatol. 2011 Jan-Feb;21(1):126-7. [CrossRef]

- Kobrinski DA, Choudhury AM, Shah RP. A case of locally-advanced Merkel cell carcinoma progressing with disseminated bone marrow metastases. European Journal of Dermatology. John Libbey Eurotext; 2018. p. 550–1. [CrossRef]

- Folyovich A, Majoros A, Jarecsny T, Pánczél G, Pápai Z, Rudas G, Kozák L, Barna G, Béres-Molnár KA, Vadasdi K, et al. Epileptic Seizure Provoked by Bone Metastasis of Chronic Lymphoid Leukemia and Merkel Cell Carcinoma. Case Rep Med. 2020 Oct 27;2020:4318638. [CrossRef]

- Vlad R, Woodlock TJ. Merkel Cell Carcinoma after Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia: Case Report and Literature Review. American Journal of Clinical Oncology: Cancer Clinical Trials. 2003 Dec;26(6):531–4.

- Goepfert H, Remmler D, Silva E, Wheeler B. Merkel cell carcinoma (endocrine carcinoma of the skin) of the head and neck. Arch Otolaryngol. 1984 Nov;110(11):707-12. [CrossRef]

- Goodwin CR, Mehta AI, Adogwa O, Sarabia-Estrada R, Sciubba DM. Merkel Cell Spinal Metastasis: Management in the Setting of a Poor Prognosis. Global Spine J. 2015 Aug 1;5(4):39–43. [CrossRef]

- Haykal T, Towfiq B. Merkel cell carcinoma with intramedullary spinal cord metastasis: a very rare clinical finding. Clin Case Rep. 2018 Apr 6;6(6):1181-1182. [CrossRef]

- Madden N, Thomas P, Johnson P, Anderson K, Arnold P. Thoracic Spinal Metastasis of Merkel Cell Carcinoma in an Immunocompromised Patient: Case Report. Evid Based Spine Care J. 2013 May 1;04(01):054–8. [CrossRef]

- Moayed S, Maldjian C, Adam R, Bonakdarpour A. Magnetic resonance imaging appearance of metastatic Merkel cell carcinoma to the sacrum and epidural space. 2000. [CrossRef]

- Nguyen BD, McCullough AE. Isolated Tibial Metastasis from Merkel Cell Carcinoma. Radiol Case Rep. 2007;2(4):88. [CrossRef]

- Kamijo A, Koshino T, Hirakawa K, Saito T. Merkel cell carcinoma with bone metastasis: a case report. Vol. 7, J Orthop Sci. 2002. [CrossRef]

- Pectasides D, Moutzourides G, Dimitriadis M, Varthalitis J, Athanassiou A. Chemotherapy for Merkel cell carcinoma with carboplatin and etoposide. Am J Clin Oncol. 1995 Oct;18(5):418-20. [CrossRef]

- Pilotti S, Rilke F, Bartoli C, Grisotti A. Clinicopathologic correlations of cutaneous neuroendocrine Merkel cell carcinoma. J Clin Oncol. 1988 Dec;6(12):1863-73. [CrossRef]

- Principe DR, Clark JI, Emami B, Borowicz S. Combined radio-immunotherapy leads to complete clinical regression of stage IV Merkel cell carcinoma. BMJ Case Rep. 2019 Aug 1;12(8). [CrossRef]

- Vijay K, Venkateswaran K, Shetty AP, Rajasekaran S. Spinal extra-dural metastasis from Merkel cell carcinoma: A rare cause of paraplegia. European Spine Journal. 2008 Sep;17. [CrossRef]

- Ng G, Lenehan B, Street J. Metastatic Merkel cell carcinoma of the spine. Journal of Clinical Neuroscience. 2010 Aug;17(8):1069–71. [CrossRef]

- Turgut M, Gökpinar D, Barutça S, Erkuş M. Lumbosacral metastatic extradural Merkel cell carcinoma causing nerve root compression--case report. Neurol Med Chir (Tokyo). 2002 Feb;42(2):78-80. [CrossRef]

- Zhao M, Meng M Bin. Merkel cell carcinoma with lymph node metastasis in the absence of a primary site: Case report and literature review. Oncol Lett. 2012 Dec;4(6):1329–34.

- Maugeri R, Giugno A, Giammalva RG, Gulì C, Basile L, Graziano F, Iacopino DG. A thoracic vertebral localization of a metastasized cutaneous Merkel cell carcinoma: Case report and review of literature. Surg Neurol Int. 2017 Aug 10;8:190. [CrossRef]

- Chao TC, Park JM, Rhee H, Greager JA. Merkel cell tumor of the back detected during pregnancy. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1990 Aug;86(2):347-51. [CrossRef]

- Park JS, Park YM. Cervical Spinal Metastasis of Merkel Cell Carcinoma. Neurospine. 2009;6(3):197-200.

- Turgut M, Baka M, Yurtseven M. Metastatic Merkel cell carcinoma to the sacrum and epidural space: case report. Magn Reson Imaging. 2004 Nov;22(9):1340. [CrossRef]

- Tam CS, Turner P, McLean C, Whitehead S, Cole-Sinclair M. 'Leukaemic' presentation of metastatic Merkel cell carcinoma. Br J Haematol. 2005 May;129(3):446.

- Gooptu C, Woollons A, Ross J, Price M, Wojnarowska F, Morris PJ, Wall S, Bunker CB. Merkel cell carcinoma arising after therapeutic immunosuppression. Br J Dermatol. 1997 Oct;137(4):637-41. [CrossRef]

- Zijlker LP, Bakker M, van der Hiel B, Bruining A, Klop WMC, Zuur CL, Wouters MWJM, van Akkooi ACJ. Baseline ultrasound and FDG-PET/CT imaging in Merkel cell carcinoma. J Surg Oncol. 2023 Apr;127(5):841-847.

- Shim SR, Kim SJ. Diagnostic Test Accuracy of 18F-FDG PET or PET/CT in Merkel Cell Carcinoma. Clin Nucl Med. 2022 Oct 1;47(10):843–8.

- Oh HY, Kim D, Choi YS, Kim EK, Kim TE. Merkel Cell Carcinoma of the Trunk: Two Case Reports and Imaging Review. Journal of the Korean Society of Radiology. 2023 Sep 1;84(5):1134–9. [CrossRef]

- Kirienko M, Gelardi F, Fiz F, Bauckneht M, Ninatti G, Pini C, Briganti A, Falconi M, Oyen WJG, van der Graaf WTA, et al. Personalised PET imaging in oncology: an umbrella review of meta-analyses to guide the appropriate radiopharmaceutical choice and indication. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2024 Dec;52(1):208-224. [CrossRef]

- Ming Y, Wu N, Qian T, Li X, Wan DQ, Li C, Li Y, Wu Z, Wang X, Liu J, et al. Progress and Future Trends in PET/CT and PET/MRI Molecular Imaging Approaches for Breast Cancer. Front Oncol. 2020 Aug 12;10:1301. [CrossRef]

- Costelloe CM, Rohren EM, Madewell JE, Hamaoka T, Theriault RL, Yu TK, Lewis VO, Ma J, Stafford RJ, Tari AM, et al. Imaging bone metastases in breast cancer: techniques and recommendations for diagnosis. Lancet Oncol. 2009 Jun;10(6):606-14. [CrossRef]

- Uchida N, Sugimura K, Kajitani A, Yoshizako T, Ishida T. MR imaging of vertebral metastases: evaluation of fat saturation imaging. European Journal of Radiology. 1993. [CrossRef]

- Girard R, Djelouah M, Barat M, Fornès P, Guégan S, Dupin N, et al. Abdominal metastases from Merkel cell carcinoma: Prevalence and presentation on CT examination in 111 patients. Diagn Interv Imaging. 2022 Jan 1;103(1):41–8. [CrossRef]

- Li X, Wu N, Zhang W, Liu Y, Ming Y. Differential diagnostic value of 18F-FDG PET/CT in osteolytic lesions. J Bone Oncol. 2020 Jul 13;24:100302. [CrossRef]

- Patel PY, Dalal I, Griffith B. [18F]FDG-PET Evaluation of Spinal Pathology in Patients in Oncology: Pearls and Pitfalls for the Neuroradiologist. American Journal of Neuroradiology. American Society of Neuroradiology; 2022. p. 332–40. [CrossRef]

- Hong SB, Choi SH, Kim KW, Park SH, Kim SY, Lee SJ, Lee SS, Byun JH, Lee MG. Diagnostic performance of [18F]FDG-PET/MRI for liver metastasis in patients with primary malignancy: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur Radiol. 2019 Jul;29(7):3553-3563. [CrossRef]

- Choi J, Raghavan M. Diagnostic imaging and image-guided therapy of skeletal metastases. Cancer Control. 2012 Apr;19(2):102-12. [CrossRef]

- Macedo F, Ladeira K, Pinho F, Saraiva N, Bonito N, Pinto L, Goncalves F. Bone Metastases: An Overview. Oncol Rev. 2017 May 9;11(1):321. [CrossRef]

- Schadendorf D, Nghiem P, Bhatia S, Hauschild A, Saiag P, Mahnke L, Hariharan S, Kaufman HL. Immune evasion mechanisms and immune checkpoint inhibition in advanced merkel cell carcinoma. Oncoimmunology. 2017 Aug 31;6(10):e1338237. [CrossRef]

- Tai P. A Practical Update of Surgical Management of Merkel Cell Carcinoma of the Skin. ISRN Surg. 2013 Jan 30;2013:1–17. [CrossRef]

- Cornejo C, Miller CJ. Merkel Cell Carcinoma: Updates on Staging and Management. Vol. 37, Dermatologic Clinics. W.B. Saunders; 2019. p. 269–77.

- Singh B, Qureshi MM, Truong MT, Sahni D. Demographics and outcomes of stage I and II Merkel cell carcinoma treated with Mohs micrographic surgery compared with wide local excision in the National Cancer Database. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2018 Jul 1;79(1):126-134.e3. [CrossRef]

- Shaikh WR, Sobanko JF, Etzkorn JR, Shin TM, Miller CJ. Utilization patterns and survival outcomes after wide local excision or Mohs micrographic surgery for Merkel cell carcinoma in the United States, 2004-2009. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2018 Jan;78(1):175-177.e3.

- Kline L, Coldiron B. Mohs micrographic surgery for the treatment of merkel cell carcinoma. Dermatologic Surgery. 2016;42(8):945–51. [CrossRef]

- Terushkin V, Brodland DG, Sharon DJ, Zitelli JA. Mohs surgery for early-stage Merkel cell carcinoma (MCC) achieves local control better than wide local excision ± radiation therapy with no increase in MCC-specific death. Int J Dermatol. 2021 Aug 1;60(8):1010–2. [CrossRef]

- Tran DC, Ovits C, Wong P, Kim RH. Mohs micrographic surgery reduces the need for a repeat surgery for primary Merkel cell carcinoma when compared to wide local excision: A retrospective cohort study of a commercial insurance claims database. JAAD Int. 2022 Aug 27;9:97-99. [CrossRef]

- Bhatia S, Storer BE, Iyer JG, Moshiri A, Parvathaneni U, Byrd D, Sober AJ, Sondak VK, Gershenwald JE, Nghiem P. Adjuvant Radiation Therapy and Chemotherapy in Merkel Cell Carcinoma: Survival Analyses of 6908 Cases From the National Cancer Data Base. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2016 May 31;108(9):djw042.

- Asgari MM, Sokil MM, Warton EM, Iyer J, Paulson KG, Nghiem P. Effect of host, tumor, diagnostic, and treatment variables on outcomes in a large cohort with merkel cell carcinoma. JAMA Dermatol. 2014;150(7):716–23. [CrossRef]

- Broida SE, Chen XT, Baum CL, Brewer JD, Block MS, Jakub JW, Pockaj BA, Foote RL, Markovic SN, Hieken TJ, et al. Merkel cell carcinoma of unknown primary: Clinical presentation and outcomes. J Surg Oncol. 2022 Nov;126(6):1080-1086. [CrossRef]

- Becker J. C., Hassel J. C., Menzer C., Kähler K. C., Eigentler T. K., Meier F. E., Berking C., Gutzmer R., Mohr P., Kiecker F., et al. Adjuvant ipilimumab compared with observation in completely resected Merkel cell carcinoma (ADMEC): A randomized, multicenter DeCOG/ADO study. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2018. Vol. 36. No. 15_suppl. p. 9527. [CrossRef]

- Becker JC, Ugurel S, Leiter U, Meier F, Gutzmer R, Haferkamp S, Zimmer L, Livingstone E, Eigentler TK, Hauschild A, et al. Adjuvant immunotherapy with nivolumab versus observation in completely resected Merkel cell carcinoma (ADMEC-O): disease-free survival results from a randomised, open-label, phase 2 trial. Lancet. 2023 Sep 2;402(10404):798-808. [CrossRef]

| Cell of origin | Driving mechanism | Evidence supporting the origin of MCC from the specific candidate cell | |

| Pros | Cons | ||

| Merkel cell | UV-related | Phenotypic similarities: cytokeratin (CK) 20, neuroendocrine markers (chromogranin A, synaptophysin), Piezo2 and Atoh1. | No mitotic activity. No transformation/proliferation induced by MCPyV T antigens. Different anatomic localization between the candidate cell and MCC. Lack of connection between the tumor cells and the epidermis. |

| Epithelial progenitor | UV-related | Presence of UV-signature (TP53, Rb inactivation). Ability to differentiate into Merkel cell. Ability to differentiate in MCC. Most likely origin of neuroendocrine carcinoma in other sites (SCLC). |

No transformation/proliferation induced by MCPyV T antigens. Lack of connection between tumor cells and the epidermis. |

| Fibroblast and dermal stem cell | MCPyV-related | Ability of MCPyV antigens to induce transformation in these cell types. Explain the exclusive dermal/hypodermal localization of MCC. |

Lack of UV signature. No evidence to suggest that fibroblasts can acquire a Merkel cell-like phenotype. Unpredicted origin for a neuroendocrine carcinoma. |

| Pre/Pro B-cell | MCPyV-related | Epidemiologic data on the association between MCC and B-cell neoplasia. Co-expression of B-cell markers (PAX5, TdT, Ig). Detection of MCPyV integration in B-cell neoplasia. |

Lack of UV signature. No evidence that B-cells can acquire a Merkel cell-like phenotype. Unpredicted origin for a neuroendocrine carcinoma. |

| Stain | MCC* | SCLC | Neuroblastoma | Ewing sarcoma | Small-cell melanoma | Lymphoma |

| Neurofilament (NF) | + | − | + | + | − | − |

| Cytokeratin (CK) 20 | + | − | − | − | − | − |

| Cytokeratin (CK) 7 | +/− | +/− | − | − | − | − |

| Thyroid transcription factor-1 (TTF1) | +/− | + | − | − | − | |

| Neuron-specific enolase (NSE) | + | + | + | +/− | − | − |

| Chromogranin A | + | + | + | − | − | − |

| Synaptophysin (SYP) | + | + | + | +/− | − | − |

| Neural cell adhesion molecule (NCAM) or CD56 | + | + | + | +/− | + | +/− |

| S100 | − | − | − | − | + | − |

| Leukocyte common antigen (LCA) or CD45 | − | − | − | − | − | + |

| AJCC Stage | TNM staging | Primary Tumor | Lymph Node | Metastasis | |

| 0 | Tis, N0, M0 | In situ (within epidermis only) | No regional lymph node metastasis | No distant metastasis | |

| I | Clinical* | T1, N0, M0 | ≤ 2 cm maximum tumor dimension | Nodes negative by clinical exam (no pathological exam performed) |

No distant metastasis |

| Pathologic** | T1, pN0, M0 | ≤ 2 cm maximum tumor dimension | Nodes negative by pathologic exam | No distant metastasis | |

| IIA | Clinical* | T2-3, N0, M0 | > 2 cm tumor dimension | Nodes negative by clinical exam (no pathological exam performed) |

No distant metastasis |

| Pathologic** | T2-3, pN0, M0 | > 2 cm tumor dimension | Nodes negative by pathological exam | No distant metastasis | |

| IIB | Clinical* | T4, N0, M0 | Primary tumor invades bone, muscle, fascia, or cartilage | Nodes negative by clinical exam (no pathological exam performed) |

No distant metastasis |

| Pathologic** | T4, pN0, M0 | Primary tumor invades bone, muscle, fascia, or cartilage |

Nodes negative by pathologic exam | No distant metastasis | |

| III | Clinical* | T0-4, N1-3*****, M0 | Any size / depth tumor | Nodes positive by clinical exam (no pathological exam performed) |

No distant metastasis |

| IIIA | Pathologic** | T1-4, pN1a(sn)*** or pN1a, M0 | Any size / depth tumor | Nodes positive by pathological exam only (nodal disease not apparent on clinical exam) |

No distant metastasis |

| T0, pN1b, M0 | Not detected (“unknown primary”) | Nodes positive by clinical exam, and confirmed via pathological exam | No distant metastasis | ||

| IIIB | Pathologic** | T1-4, pN1b-3, M0 | Any size / depth tumor | Nodes positive by clinical exam, and confirmed via pathological exam OR in-transit metastasis **** | No distant metastasis |

| IV | Clinical* | T0-4, any N, M1 | Any | +/- regional nodal involvement | Distant metastasis detected via clinical exam |

| Pathologic** | T0-4, any pN, M1 | Any | +/- regional nodal involvement | Distant metastasis confirmed via pathological exam |

|

| Author | Study’ type | Patient/s | Merkel cell carcinoma |

Another site/s of distant metastasis (n., %) * |

Overall Survival for bone/BM metastatic patients | ||||||

| Number (n.) | Age (years) |

Sex | Primary MCC | Bone/bone marrow metastases | |||||||

| Known | Unknown | ||||||||||

| Male n (%) |

Female n (%) |

n. (%) | n. (%) | n. (%) | Therapy | ||||||

| Khaddour et al. [113] | Original article | 34 | 70.2 (51.4) *** |

20 (58.8) |

14 (41.2) | 14 (41.2) | 20 (58.8) | 10 (29.4) | CHT, IT | Regional LNs (28, 82.4) |

8.2 months (median) |

| Xia et al. [111] | Original article | 273 | **** | 200 (73.3) | 73 (26.7) | 184 (67.4) | 89 (32.6) | 31 (11.3) ** |

CHT, RT, surgery | Liver (37, 13.5) | 1-year median OS rate of 38.7% ** |

| Kim et al. [7] | Original article | 151 | 76 (62) *** |

101 (66.9) | 50 (23.1) | 134 (88.8) | 17 (11.2) | 40 (26.5) | IT, RT, surgery | LNs (94, 62.3), skin/soft tissue (40, 26.5) | 15.1 months (median) |

| Lewis et al. [6] | Original article | 215 | / | 176 (82) | 39 (18) | 173 (80) | 42 (20) | 64 (21) | CHT, RT | Non-regional LNs (88, 41%) | / |

| Pilotti et al. [148] | Original article | 50 | 62 (45) *** |

22 (44) | 28 (56) | 40 (80) | 10 (20) | 1 (2) | CHT | Skin (4, 8), liver (2, 4), pancreas (2, 4), lung (1, 2) | 12 months |

| Goepfert et al. [140] | Original article | 41 | 66 (55) *** |

**** | **** | **** | **** | 4 (9.8) | CHT | Skin (5, 12.1%), LNs (4, 9.8%) | / |

| Maloney et al. [104] | Original article | 331 | 74.6 (15.5) *** |

241 (72.8) | 90 (27.2) |

**** | **** | 6 (1.9) | / | Liver (89, 28.7), lung (51, 16.4), brain (6, 1.9) | 5-year median OS rate of 11.2 % |

| Pectasides et al. [147] | Case report # | 1 | 48 | 1 (100) | / | 1 Buttock |

/ | 1 T11, L2 vertebra |

CHT, RT | Regional LNs | 5 months |

| Nguyen et al. [145] | Case report # | 1 | 69 |

1 (100) | / | 1 Cheek |

/ | 1 Tibia |

Surgery | / | 19 months |

| Kamijo et al. [146] | Case report # | 1 | 75 | / | 1 (100) | 1 Cheek |

/ | 1 Femur |

RT, surgery | Subcutaneous tissue | 16 months |

| Wang et al. [127] | Case report # | 1 | 79 | / | 1 (100) | / | 1 | 1 BM |

/ | / | / |

| Khan et al. [128] | Case report # | 1 | 80 | / | 1 (100) | 1 Trunk |

/ | 1 BM |

CHT, RT | Regional LNs | 1 month |

| Morris et al. [129] | Case report # | 1 | 72 | 1 (100) | / | 1 Shoulder |

/ | 1 BM |

Death before starting CHT | Regional LNs | 4 months |

| Le Gall-Ianotto et al. [136] | Case report # | 1 | 65 | 1 (100) | / | / | 1 | 1 BM |

CHT, RT | / | 3 months |

| Kobrinski et al. [137] | Case report # | 1 | 86 | 1 (100) | / | 1 Trunk |

/ | 1 BM |

RT | Regional LNs | 12 months |

| Kressin et al. [130] | Case report # | 1 | 64 | 1 (100) | / | 1 Forehead |

/ | 1 BM |

Death before starting CHT | Regional LNs | 3 months |

| Keow et al. [131] | Case report # | 1 | 71 | 1 (100) | / | 1 | / | 1 BM |

/ | / | / |

| Durmus et al. [132] | Case report # | 1 | 60 | 1 (100) | / | 1 Thigh |

/ | 1 BM |

Death before starting IT | Regional LNs, liver | 7 months |

| Nemoto et al. [133] | Case report # | 1 | 73 | / | 1 (100) | 1 Cheek |

/ | 1 BM |

Death before starting therapy | Regional LNs | 8 months |

| Vlad et al. [139] | Case report # | 1 | 72 | 1 (100) | / | 1 Arm |

/ | 1 BM |

CHT | Regional LNs | 8 months |

| Barkdull et al. [110] | Case report # | 1 | 55 | 1 (100) | / | 1 Scalp |

/ | 1 Sternum |

CHT | Regional LNs, subcutaneous tissue, pancreas |

9 months |

| Leão et al. [125] | Case report # | 1 | 61 | 1 (100) | / | 1 Buttock |

/ | 1 Sacrum |

CHT, IT (Avelumab) | In-transit metastasis | 30 months |

| Lentz et al. [126] | Case report # | 1 | 55 | 1 (100) | / | 1 Scalp |

/ | 1 BM |

CHT | Regional LNs, parotid gland | 12 months |

| Smadja et al. [135] | Case report # | 1 | 34 | / | 1 (100) | 1 Shoulder |

/ | 1 BM |

CHT | Lung, brain | 4 months |

| Vijay et al. [150] | Case report # | 1 | 57 | / | 1 (100) | / | 1 | 1 Extra-dural T8, L4, S1 |

CHT, RT | Non-regional LNs | 1 month |

| Ng et al. [151] | Case report # | 1 | 73 | 1 (100) | / | 1 Arm |

/ | 1 Extra-dural T5-T7 |

Surgery, death before starting CHT/RT | / | 1 month |

| Highland et al. [134] | Case report # | 1 | 74 | 1 (100) | / | 1 Lip |

/ | 1 BM |

CHT | Regional LNs | 13 months |

| Maugeri et al. [154] | Case report # | 1 | 59 | / | 1(100) | 1 Scalp |

/ | 1 T7-T8 vertebra |

CHT, RT | Liver, lung | 8 months |

| Chao et al. [155] | Case report # | 1 |

23 | / | 1 (100) | 1 Back |

/ | 1 Extradural T3-T4 |

CHT, RT | Lung, heart | 23 months |

| Moayed et al. [144] | Case report # | 1 | 70 | 1 (100) | / | / | 1 | 1 Lumbosacral spine, epidural S1, hip |

CHT, RT | Regional LNs | 9 moths |

| Turgut et al. [152] | Case report # | 1 | 63 | 1 (100) | / | 1 Abdomen | / | 1 Extradural L5–S1 |

CHT | “Massive” **** | 2 months |

| Turgut et al. [157] | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Payne et al. [116] | Case report # | 1 | 77 | / | 1 (100) | 1 Buttock |

/ | 1 T4 vertebra |

RT | Bone, lung | 12 months |

| Park et al. [156] | Case report # | 1 | 30 | 1 (100) | / | 1 Hand |

/ | 1 C6 vertebra |

Death before starting CHT/RT | / | 1 month |

| Madden et al. [143] | Case report # | 1 | 55 | 1 (100) | / | 1 Neck |

/ | 1 Epidural T6-T8 |

RT, surgery | bone | 4 months |

| Goodwin et al. [141] | Case report # | 1 | 76 | 1 (100) | / | 1 Back |

/ | 1 Epidural T5 |

RT, surgery | bone | 15 months |

| Zhao et al. [153] |

Case report # | 1 | 54 | 1 (100) | / | / | 1 | 1 T6, T12, L2 vertebra |

CHT, RT, surgery | Regional LNs, liver | 21 moths |

| Folyovich et al. [138] | Case report # | 1 | 62 | / | 1 (100) | 1 Arm |

/ | 1 skull |

CHT, RT | Non-regional LNs | 24 months |

| Haykal et al. [142] | Case report # | 1 | 49 | / | 1 (100) | 1 Vulva |

/ | 1 Intradural intramedullary C4-C5 |

CHT, RT | Regional and non-regional LNs, liver | - |

| Pennisi et al. [124] | Case report # | 1 | 73 | / | 1 (100) | 1 Face |

/ | 1 Intradural extramedullary C6-C7 |

IT (Avelumab), RT | Skin, subcutaneous tissue | 5 months |

| Principe et al. [149] | Case report # | 1 | 79 | 1 (100) | / | 1 Ear |

/ | 1 T2, T7, T10-11, L3 vertebra |

IT (Avelumab), RT | Regional LNs, parotid gland | 18 months |

| Abul-Kasim et al. [122] | Case report # | 1 | 65 | 1 (100) | / | / | 1 | 1 Epidural and intradural L1, L5 |

RT, surgery | Non-regional LNs, brain, retroperitoneum, lung | 8 months |

| Tam et al. [158] | Case report # | 1 | 66 | 1 (100) | / | 1 Forearm |

/ | 1 BM |

Death before therapy | / | 6 months |

| - | - | 1 | 55 | 1 (100) | / | / | 1 | 1 BM |

CHT | / | 1.5 month |

| Gooptu et al. [159] | Case report # | 1 | 68 | / | 1 (100) | 1 Leg |

/ | 1 BM |

CHT | Non-regional LNs | 2 months |

| - | - | 1 | 55 | 1 (100) | / | 1 Neck |

/ | 1 Vertebra |

RT | Non-regional LNs, brain | 6 months |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).