Submitted:

04 April 2025

Posted:

08 April 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Preparation of Freeze-Dried Immobilized L. cremoris Cells on Oat Flakes

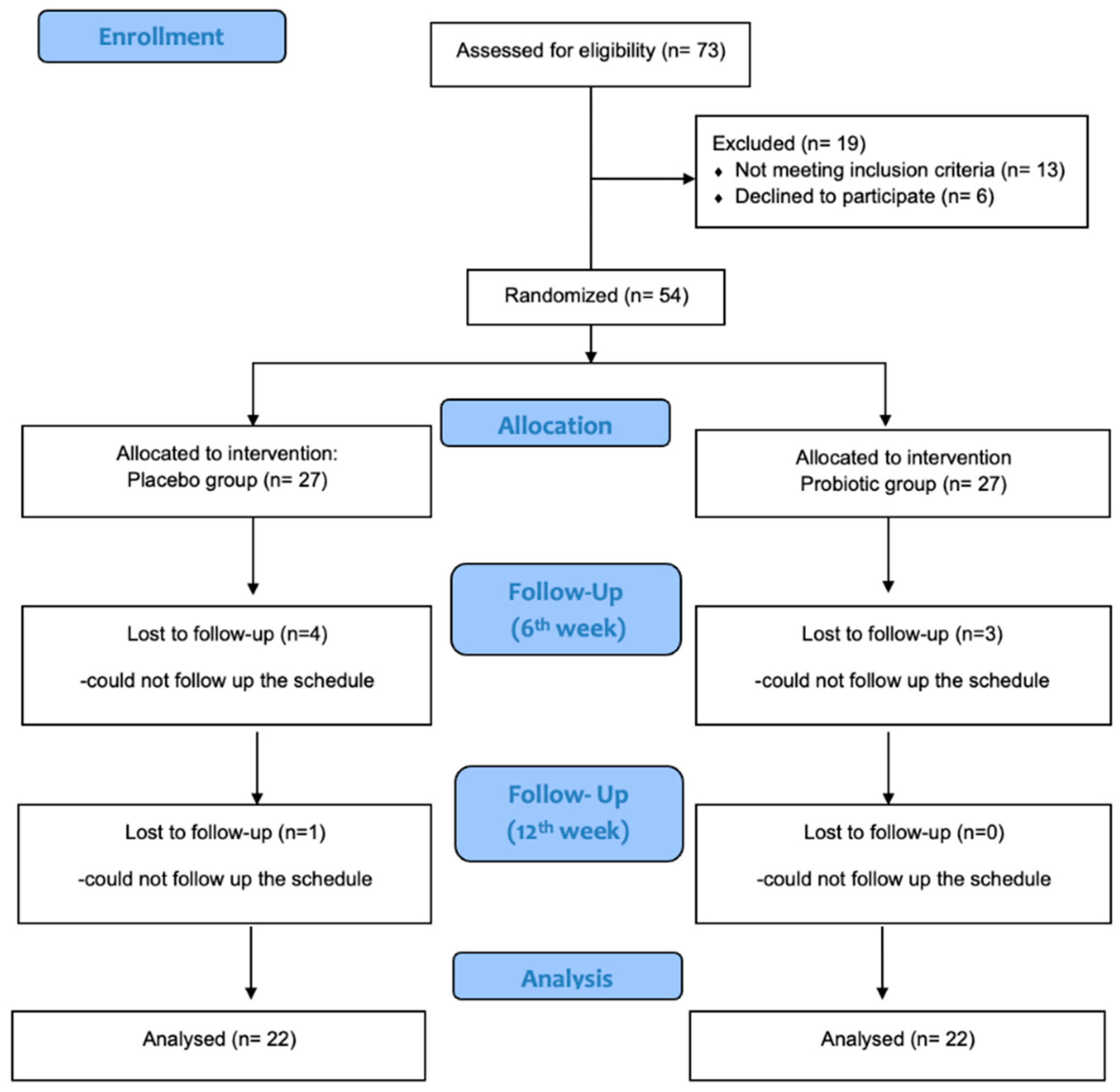

2.2. Study Design

2.3. Participants

2.4. Intervention

2.5. Anthropometric and Biochemical Measurements

2.6. Statistical Analysis

2.6.1. Sample Size

2.6.2. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Participants

3.2. Dietary Habits

3.3. Blood Biomarkes

3.3.1. Inflammatory & Immunological Biomarkers

3.3.2. Lipemia Biomarkers

3.3.3. Glycemia Biomarkers

3.3.4. Folate, VitB12, VitD

3.3.4. Cortisol, Uric Acid, Antioxidan Capacity

3.3.5. Urine Biomarkers

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- de Melo Pereira, G.V.; de Oliveira Coelho, B.; Magalhães Júnior, A.I.; Thomaz-Soccol, V.; Soccol, C.R. How to Select a Probiotic? A Review and Update of Methods and Criteria. Biotechnology Advances 2018, 36, 2060–2076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maldonado Galdeano, C.; Cazorla, S.I.; Lemme Dumit, J.M.; Vélez, E.; Perdigón, G. Beneficial Effects of Probiotic Consumption on the Immune System. Annals of Nutrition and Metabolism 2019, 74, 115–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gill, H.S.; Guarner, F. Probiotics and Human Health: A Clinical Perspective. Postgrad Med J 2004, 80, 516–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Ji, H.; Wang, S.; Liu, H.; Zhang, W.; Zhang, D.; Wang, Y. Probiotic Lactobacillus Plantarum Promotes Intestinal Barrier Function by Strengthening the Epithelium and Modulating Gut Microbiota. Frontiers in Microbiology 2018, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, C.-S.; Chang, C.-J.; Lu, C.-C.; Martel, J.; Ojcius, D.M.; Ko, Y.-F.; Young, J.D.; Lai, H.-C. Impact of the Gut Microbiota, Prebiotics, and Probiotics on Human Health and Disease. Biomed J 2014, 37, 259–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Toole, P.W.; Cooney, J.C. Probiotic Bacteria Influence the Composition and Function of the Intestinal Microbiota. Interdisciplinary Perspectives on Infectious Diseases 2008, 2008, e175285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bajaj, B.; Claes, I.; Lebeer, S. Functional Mechanisms of Probiotics. Journal of Microbiology, Biotechnology and Food Sciences 2015, 04, 321–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maftei, N.-M.; Raileanu, C.R.; Balta, A.A.; Ambrose, L.; Boev, M.; Marin, D.B.; Lisa, E.L. The Potential Impact of Probiotics on Human Health: An Update on Their Health-Promoting Properties. Microorganisms 2024, 12, 234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cimminiello, C.; Zambon, A.; Polo Friz, H. Hypercholesterolemia and cardiovascular risk: advantages and limitations of current treatment options. G Ital Cardiol (Rome) 2016, 17, 6S–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhat, B.; Bajaj, B.K. Multifarious Cholesterol Lowering Potential of Lactic Acid Bacteria Equipped with Desired Probiotic Functional Attributes. 3 Biotech 2020, 10, 200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rigobelo, E. Probiotics; BoD – Books on Demand, 2012; ISBN 978-953-51-0776-7.

- Alahmari, L.A. Dietary Fiber Influence on Overall Health, with an Emphasis on CVD, Diabetes, Obesity, Colon Cancer, and Inflammation. Front Nutr 2024, 11, 1510564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Joyce, S.A.; Kamil, A.; Fleige, L.; Gahan, C.G.M. The Cholesterol-Lowering Effect of Oats and Oat Beta Glucan: Modes of Action and Potential Role of Bile Acids and the Microbiome. Front Nutr 2019, 6, 171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Min, M.; Bunt, C.R.; Mason, S.L.; Hussain, M.A. Non-Dairy Probiotic Food Products: An Emerging Group of Functional Foods. Critical Reviews in Food Science and Nutrition 2019, 59, 2626–2641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghishan, F.K.; Kiela, P.R. From Probiotics to Therapeutics: Another Step Forward? J Clin Invest 2011, 121, 2149–2152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ranjha, M.M.A.N.; Shafique, B.; Batool, M.; Kowalczewski, P.Ł.; Shehzad, Q.; Usman, M.; Manzoor, M.F.; Zahra, S.M.; Yaqub, S.; Aadil, R.M. Nutritional and Health Potential of Probiotics: A Review. Applied Sciences 2021, 11, 11204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ranadheera, R.D.C.S.; Baines, S.K.; Adams, M.C. Importance of Food in Probiotic Efficacy. Food Research International 2010, 43, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- From Probiotics to Prebiotics and a Healthy Digestive System - Gibson - 2004 - Journal of Food Science - Wiley Online Library. Available online: https://ift.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1111/j.1365-2621.2004.tb10724.x?casa_token=YzW3rNy_DMoAAAAA:UDFodGkqNynYTBpVp6IR8OXq09o0-ZEg8QaW16YNnlrxWtRicBkb4--09EbIMLxArFHPtFH1-2Ji42s (accessed on 19 October 2023).

- Axelsson, L.; Ahrné, S. Lactic Acid Bacteria. In Applied Microbial Systematics; Priest, F.G., Goodfellow, M., Eds.; Springer Netherlands: Dordrecht, 2000; pp. 367–388. ISBN 978-0-7923-6518-1. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Y.; Wu, J.; Lv, M.; Shao, Z.; Hungwe, M.; Wang, J.; Bai, X.; Xie, J.; Wang, Y.; Geng, W. Metabolism Characteristics of Lactic Acid Bacteria and the Expanding Applications in Food Industry. Frontiers in Bioengineering and Biotechnology 2021, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ishida, T.; Yokota, A.; Umezawa, Y.; Toda, T.; Yamada, K. Identification and Characterization of Lactococcal and Acetobacter Strains Isolated from Traditional Caucasusian Fermented Milk. Journal of Nutritional Science and Vitaminology 2005, 51, 187–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watanabe, M.; Maruo, T.; Suzuki, T. Effects of Intake of Lactococcus Cremoris Subsp. Cremoris FC on Constipation Symptoms and Immune System in Healthy Participants with Mild Constipation: A Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled Study. International Journal of Food Sciences and Nutrition 2023, 74, 695–706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozaki, K.; Maruo, T.; Kosaka, H.; Mori, M.; Mori, H.; Yamori, Y.; Toda, T. The Effects of Fermented Milk Containing Lactococcus Lactis Subsp. Cremoris FC on Defaecation in Healthy Young Japanese Women: A Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled Study. International Journal of Food Sciences and Nutrition 2018, 69, 762–769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prapa, I.; Pavlatou, C.; Kompoura, V.; Nikolaou, A.; Stylianopoulou, E.; Skavdis, G.; Grigoriou, M.E.; Kourkoutas, Y. A Novel Wild-Type Lacticaseibacillus Paracasei Strain Suitable for the Production of Functional Yoghurt and Ayran Products. Fermentation 2025, 11, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benzie, I.F.F.; Strain, J.J. The Ferric Reducing Ability of Plasma (FRAP) as a Measure of “Antioxidant Power”: The FRAP Assay. Analytical Biochemistry 1996, 239, 70–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CONSORT 2010 Statement: Updated Guidelines for Reporting Parallel Group Randomised Trials | The BMJ. Available online: https://www.bmj.com/content/340/bmj.c332 (accessed on 23 February 2023).

- A Healthy Lifestyle - WHO Recommendations. Available online: https://www.who.int/europe/news-room/fact-sheets/item/a-healthy-lifestyle---who-recommendations (accessed on 13 February 2024).

- Yeo, S.-K.; Ewe, J.-A.; Tham, C.S.-C.; Liong, M.-T. Carriers of Probiotic Microorganisms. In Probiotics: Biology, Genetics and Health Aspects; Liong, M.-T., Ed.; Microbiology Monographs; Springer: Berlin, Heidelberg, 2011; pp. 191–220. ISBN 978-3-642-20838-6. [Google Scholar]

- Granato, D.; Branco, G.F.; Nazzaro, F.; Cruz, A.G.; Faria, J.A.F. Functional Foods and Nondairy Probiotic Food Development: Trends, Concepts, and Products. Comprehensive Reviews in Food Science and Food Safety 2010, 9, 292–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rivera-Espinoza, Y.; Gallardo-Navarro, Y. Non-Dairy Probiotic Products. Food Microbiology 2010, 27, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rasika, D.M.D.; Vidanarachchi, J.K.; Luiz, S.F.; Azeredo, D.R.P.; Cruz, A.G.; Ranadheera, C.S. Probiotic Delivery through Non-Dairy Plant-Based Food Matrices. Agriculture 2021, 11, 599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagpal, R.; Kaur, A. Synbiotic Effect of Various Prebiotics on In Vitro Activities of Probiotic Lactobacilli. Ecology of Food and Nutrition 2011, 50, 63–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Y.K.; Menezes, J.S.; Umesaki, Y.; Mazmanian, S.K. Proinflammatory T-Cell Responses to Gut Microbiota Promote Experimental Autoimmune Encephalomyelitis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2011, 108 Suppl 1, 4615–4622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lye, H.-S.; Kuan, C.-Y.; Ewe, J.-A.; Fung, W.-Y.; Liong, M.-T. The Improvement of Hypertension by Probiotics: Effects on Cholesterol, Diabetes, Renin, and Phytoestrogens. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2009, 10, 3755–3775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kazemi, A.; Soltani, S.; Ghorabi, S.; Keshtkar, A.; Daneshzad, E.; Nasri, F.; Mazloomi, S.M. Effect of Probiotic and Synbiotic Supplementation on Inflammatory Markers in Health and Disease Status: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Clinical Trials. Clinical Nutrition 2020, 39, 789–819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajkumar, H.; Kumar, M.; Das, N.; Kumar, S.N.; Challa, H.R.; Nagpal, R. Effect of Probiotic Lactobacillus Salivarius UBL S22 and Prebiotic Fructo-Oligosaccharide on Serum Lipids, Inflammatory Markers, Insulin Sensitivity, and Gut Bacteria in Healthy Young Volunteers: A Randomized Controlled Single-Blind Pilot Study. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol Ther 2015, 20, 289–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomes, A.C.; de Sousa, R.G.M.; Botelho, P.B.; Gomes, T.L.N.; Prada, P.O.; Mota, J.F. The Additional Effects of a Probiotic Mix on Abdominal Adiposity and Antioxidant Status: A Double-Blind, Randomized Trial. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2017, 25, 30–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nihei, Y.; Suzuki, H.; Suzuki, Y. Current Understanding of IgA Antibodies in the Pathogenesis of IgA Nephropathy. Front Immunol 2023, 14, 1165394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marcotte, H.; Lavoie, M.C. Oral Microbial Ecology and the Role of Salivary Immunoglobulin A. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev 1998, 62, 71–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Walker, W.A. Role of Nutrients and Bacterial Colonization in the Development of Intestinal Host Defense. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr 2000, 30 Suppl 2, S2–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gadelha, C.J.M.U.; Bezerra, A.N. Effects of Probiotics on the Lipid Profile: Systematic Review. J. vasc. bras. 2019, 18, e20180124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Guo, M.-J.; Gao, Q.; Yang, J.-F.; Yang, L.; Pang, X.-L.; Jiang, X.-J. The Effects of Probiotics on Total Cholesterol. Medicine (Baltimore) 2018, 97, e9679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nichols, A.B.; Ravenscroft, C.; Lamphiear, D.E.; Ostrander, L.D., Jr. Independence of Serum Lipid Levels and Dietary Habits: The Tecumseh Study. JAMA 1976, 236, 1948–1953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kullisaar, T.; Zilmer, K.; Salum, T.; Rehema, A.; Zilmer, M. The Use of Probiotic L. Fermentum ME-3 Containing Reg’Activ Cholesterol Supplement for 4 Weeks Has a Positive Influence on Blood Lipoprotein Profiles and Inflammatory Cytokines: An Open-Label Preliminary Study. Nutr J 2016, 15, 93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajkumar, H.; Mahmood, N.; Kumar, M.; Varikuti, S.R.; Challa, H.R.; Myakala, S.P. Effect of Probiotic (VSL#3) and Omega-3 on Lipid Profile, Insulin Sensitivity, Inflammatory Markers, and Gut Colonization in Overweight Adults: A Randomized, Controlled Trial. Mediators of Inflammation 2014, 2014, e348959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuentes, M.C.; Lajo, T.; Carrión, J.M.; Cuñé, J. Cholesterol-Lowering Efficacy of Lactobacillus Plantarum CECT 7527, 7528 and 7529 in Hypercholesterolaemic Adults. British Journal of Nutrition 2013, 109, 1866–1872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Angelino, D.; Martina, A.; Rosi, A.; Veronesi, L.; Antonini, M.; Mennella, I.; Vitaglione, P.; Grioni, S.; Brighenti, F.; Zavaroni, I.; et al. Glucose- and Lipid-Related Biomarkers Are Affected in Healthy Obese or Hyperglycemic Adults Consuming a Whole-Grain Pasta Enriched in Prebiotics and Probiotics: A 12-Week Randomized Controlled Trial. J Nutr 2019, 149, 1714–1723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rahayu, E.S.; Mariyatun, M.; Putri Manurung, N.E.; Hasan, P.N.; Therdtatha, P.; Mishima, R.; Komalasari, H.; Mahfuzah, N.A.; Pamungkaningtyas, F.H.; Yoga, W.K.; et al. Effect of Probiotic Lactobacillus Plantarum Dad-13 Powder Consumption on the Gut Microbiota and Intestinal Health of Overweight Adults. World J Gastroenterol 2021, 27, 107–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ruan, Y.; Sun, J.; He, J.; Chen, F.; Chen, R.; Chen, H. Effect of Probiotics on Glycemic Control: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Randomized, Controlled Trials. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0132121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nikbakht, E.; Khalesi, S.; Singh, I.; Williams, L.T.; West, N.P.; Colson, N. Effect of Probiotics and Synbiotics on Blood Glucose: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Controlled Trials. Eur J Nutr 2018, 57, 95–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kassaian, N.; Feizi, A.; Aminorroaya, A.; Jafari, P.; Ebrahimi, M.T.; Amini, M. The Effects of Probiotics and Synbiotic Supplementation on Glucose and Insulin Metabolism in Adults with Prediabetes: A Double-Blind Randomized Clinical Trial. Acta Diabetol 2018, 55, 1019–1028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, D.Y.; Kim, E.; Choi, M.H. Technical and Clinical Aspects of Cortisol as a Biochemical Marker of Chronic Stress. BMB Rep 2015, 48, 209–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whitworth, J.A.; Mangos, G.J.; Kelly, J.J. Cushing, Cortisol, and Cardiovascular Disease. Hypertension 2000, 36, 912–916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whitworth, J.A.; Williamson, P.M.; Mangos, G.; Kelly, J.J. Cardiovascular Consequences of Cortisol Excess. Vascular Health and Risk Management 2005, 1, 291–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lalitsuradej, E.; Sirilun, S.; Sittiprapaporn, P.; Sivamaruthi, B.S.; Pintha, K.; Tantipaiboonwong, P.; Khongtan, S.; Fukngoen, P.; Peerajan, S.; Chaiyasut, C. The Effects of Synbiotics Administration on Stress-Related Parameters in Thai Subjects—A Preliminary Study. Foods 2022, 11, 759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kazemi, A.; Noorbala, A.A.; Azam, K.; Djafarian, K. Effect of Prebiotic and Probiotic Supplementation on Circulating Pro-Inflammatory Cytokines and Urinary Cortisol Levels in Patients with Major Depressive Disorder: A Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled Randomized Clinical Trial. Journal of Functional Foods 2019, 52, 596–602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nishihira, J.; Kagami-Katsuyama, H.; Tanaka, A.; Nishimura, M.; Kobayashi, T.; Kawasaki, Y. Elevation of Natural Killer Cell Activity and Alleviation of Mental Stress by the Consumption of Yogurt Containing Lactobacillus Gasseri SBT2055 and Bifidobacterium Longum SBT2928 in a Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled Clinical Trial. Journal of Functional Foods 2014, 11, 261–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, A.H.; Gladden, J.D.; Ahmed, M.; Ahmed, A.; Filippatos, G. Relation of Serum Uric Acid to Cardiovascular Disease. International Journal of Cardiology 2016, 213, 4–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, H.; Lu, Z.; Lu, Y. The Potential of Probiotics in the Amelioration of Hyperuricemia. Food & Function 2022, 13, 2394–2414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rezazadeh, L.; Alipour, B.; Jafarabadi, M.A.; Behrooz, M.; Gargari, B.P. Daily Consumption Effects of Probiotic Yogurt Containing Lactobacillus Acidophilus La5 and Bifidobacterium Lactis Bb12 on Oxidative Stress in Metabolic Syndrome Patients. Clinical Nutrition ESPEN 2021, 41, 136–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yamanaka, H.; Taniguchi, A.; Tsuboi, H.; Kano, H.; Asami, Y. Hypouricaemic Effects of Yoghurt Containing Lactobacillus Gasseri PA-3 in Patients with Hyperuricaemia and/or Gout: A Randomised, Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled Study. Mod Rheumatol 2019, 29, 146–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amaretti, A.; di Nunzio, M.; Pompei, A.; Raimondi, S.; Rossi, M.; Bordoni, A. Antioxidant Properties of Potentially Probiotic Bacteria: In Vitro and in Vivo Activities. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol 2013, 97, 809–817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harasym, J.; Oledzki, R. Effect of Fruit and Vegetable Antioxidants on Total Antioxidant Capacity of Blood Plasma. Nutrition 2014, 30, 511–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kleniewska, P.; Hoffmann, A.; Pniewska, E.; Pawliczak, R. The Influence of Probiotic Lactobacillus Casei in Combination with Prebiotic Inulin on the Antioxidant Capacity of Human Plasma. Oxidative Medicine and Cellular Longevity 2016, 2016, e1340903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- LeMone, P. Vitamins and Minerals. Journal of Obstetric, Gynecologic, & Neonatal Nursing 1999, 28, 520–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gangadharan, D.; Nampoothiri, K.M. Folate Production Using Lactococcus Lactis Ssp Cremoris with Implications for Fortification of Skim Milk and Fruit Juices. LWT - Food Science and Technology 2011, 44, 1859–1864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rossi, M.; Amaretti, A.; Raimondi, S. Folate Production by Probiotic Bacteria. Nutrients 2011, 3, 118–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rong, N.; Selhub, J.; Goldin, B.R.; Rosenberg, I.H. Bacterially Synthesized Folate in Rat Large Intestine Is Incorporated into Host Tissue Folyl Polyglutamates. J Nutr 1991, 121, 1955–1959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clarke, R.; Grimley Evans, J.; Schneede, J.; Nexo, E.; Bates, C.; Fletcher, A.; Prentice, A.; Johnston, C.; Ueland, P.M.; Refsum, H.; et al. Vitamin B12 and Folate Deficiency in Later Life. Age Ageing 2004, 33, 34–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, Q.; Li, P.; Gu, Q.; Li, P. Biosynthesis of Vitamins by Probiotic Bacteria. In Probiotics and Prebiotics in Human Nutrition and Health; IntechOpen, 2016 ISBN 978-953-51-2476-4.

- Barkhidarian, B.; Roldos, L.; Iskandar, M.M.; Saedisomeolia, A.; Kubow, S. Probiotic Supplementation and Micronutrient Status in Healthy Subjects: A Systematic Review of Clinical Trials. Nutrients 2021, 13, 3001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mokhtari, Z.; Karbaschian, Z.; Pazouki, A.; Kabir, A.; Hedayati, M.; Mirmiran, P.; Hekmatdoost, A. The Effects of Probiotic Supplements on Blood Markers of Endotoxin and Lipid Peroxidation in Patients Undergoing Gastric Bypass Surgery; a Randomized, Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled, Clinical Trial with 13 Months Follow-Up. OBES SURG 2019, 29, 1248–1258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woodard, G.A.; Encarnacion, B.; Downey, J.R.; Peraza, J.; Chong, K.; Hernandez-Boussard, T.; Morton, J.M. Probiotics Improve Outcomes After Roux-En-Y Gastric Bypass Surgery: A Prospective Randomized Trial. J Gastrointest Surg 2009, 13, 1198–1204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Valentini, L.; Pinto, A.; Bourdel-Marchasson, I.; Ostan, R.; Brigidi, P.; Turroni, S.; Hrelia, S.; Hrelia, P.; Bereswill, S.; Fischer, A.; et al. Impact of Personalized Diet and Probiotic Supplementation on Inflammation, Nutritional Parameters and Intestinal Microbiota - The “RISTOMED Project”: Randomized Controlled Trial in Healthy Older People. Clin Nutr 2015, 34, 593–602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prentice, A. Vitamin D Deficiency: A Global Perspective. Nutrition Reviews 2008, 66, S153–S164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereira-Santos, M.; Costa, P.R.F.; Assis, A.M.O.; Santos, C. a. S.T.; Santos, D.B. Obesity and Vitamin D Deficiency: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Obes Rev 2015, 16, 341–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, M.L.; Martoni, C.J.; Prakash, S. Oral Supplementation with Probiotic L. Reuteri NCIMB 30242 Increases Mean Circulating 25-Hydroxyvitamin D: A Post Hoc Analysis of a Randomized Controlled Trial. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2013, 98, 2944–2951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Musso, C.G. Magnesium Metabolism in Health and Disease. Int Urol Nephrol 2009, 41, 357–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pérez-Conesa, D.; López, G.; Abellán, P.; Ros, G. Bioavailability of Calcium, Magnesium and Phosphorus in Rats Fed Probiotic, Prebiotic and Synbiotic Powder Follow-up Infant Formulas and Their Effect on Physiological and Nutritional Parameters. Journal of the Science of Food and Agriculture 2006, 86, 2327–2336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scholz-Ahrens, K.E.; Adolphi, B.; Rochat, F.; Barclay, D.V.; de Vrese, M.; Açil, Y.; Schrezenmeir, J. Effects of Probiotics, Prebiotics, and Synbiotics on Mineral Metabolism in Ovariectomized Rats — Impact of Bacterial Mass, Intestinal Absorptive Area and Reduction of Bone Turn-Over. NFS Journal 2016, 3, 41–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variables | Probiotic group (n=24) |

Control group (n=22) |

pa value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Female (%) | 70.8 | 68.2 | p> 0.05 |

| Age (years) | 36.6 (13.9) | 30.3 (10.2) | p> 0.05 |

| Height (m) | 1.68 (0.1) | 1.66 (0.1) | p> 0.05 |

| Body mass index (kg/m2) | 26.9 (5.5) | 23.3 (3.5) | p < 0.05 |

| Waist-to-hip ratio | 0.82 (0.1) | 0.80 (0.1) | p> 0.05 |

| Smoking (%) | 25.0 | 18.2 | p> 0.05 |

| Physical Activity (%) | p> 0.05 | ||

| High | 29.2 | 40.9 | |

| Regular | 25.0 | 13.6 | |

| Cholesterol (mg/dL) | 169.3 (23.4) | 172.18 (25.9) | p> 0.05 |

| Glucose (mg/dL) | 79.8 (11.5) | 79.6 (9.7) | p> 0.05 |

| Probiotics group (n = 24) | Placebo group (n=22) | pb | |||||

| Total Cholesterol | mean (SD) | Δ from baseline | pa | mean (SD | Change | pa | |

| 1st week | 171.0 (24.4) | 172.1 (25.8) | >0.05 | ||||

| 6th week | 190.2 (38.2) | 19.2 (44.0) | 0.039 | 176.1 (40.0) | 4.0 (30.4) | >0.05 | |

| 12th week | 175.8 (28.9) | 4.8 (28.3) | 0.040 | 179.3 (49.7) | 7.1 (33.2) | >0.05 | |

| LDL | |||||||

| 1st week | 86.2 (21.8) | 86.9 (23.4) | >0.05 | ||||

| 6th week | 91.3 (35.9) | 5.2 (28.0) | >0.05 | 80.5 (29.5) | -6.4 (18.0 | 0.005 | |

| 12th week | 91.7 (25.8) | 5.8 (14.0) | >0.05 | 92.3 (34.8) | 5.4 (17.7) | >0.05 | |

| HDL | |||||||

| 1st week | 53.5 (13.2) | 54.1 (9.8) | >0.05 | ||||

| 6th week | 51.6 (16.1) | -1.9 (14.9) | >0.05 | 53.6 (13.2) | -0.5 (13.0) | >0.05 | |

| 12th week | 54.63 (12.0) | 1.1 (9.3) | >0.05 | 58.5 (16.0) | 4.4 (11.4) | >0.05 | |

| TRGL | |||||||

| 1st week | 73.7 (30.4) | 83.5 (64.5) | >0.05 | ||||

| 6th week | 77.1 (37.1) | 3.4 (28.4) | >0.05 | 79.7 (52.9) | - 3.9 (36.5) | >0.05 | |

| 12th week | 82.4 (34.6) | 8.7 (19.1) | 0.04 | 80. 0 (43.9) | -3.5 (29.6) | >0.05 | |

| GLU | |||||||

| 1st week | 79.8 (11.5) | 79.6 (9.7) | >0.05 | ||||

| 6th week | 90.3 (19.4) | 10.5 (21.5) | 0.025 | 86.3 (16.3) | 6.7 (12.4) | 0.019 | |

| 12th week | 93.1 (10.5) | 13.3 (10.4) | <0.001 | 93.9 (11.2) | 14.3 (10.6) | <0.001 | |

| INS | |||||||

| 1st week | 9.5 (3.4) | 7.7 (3.4) | >0.05 | ||||

| 6th week | 7.8 (2.9) | -1.7 (1.9) | <0.001 | 8.2 (4.9) | 0.5 (3.7) | >0.05 | |

| 12th week | 11.2 (5.8) | +1.7 (3.7) | 0.042 | 7.8 (3.0) | 0.1 (2.4) | >0.05 | |

| UA | |||||||

| 1st week | 4.5 (1.4) | 4.5 (1.1) | >0.05 | ||||

| 6th week | 4.0 (1.8) | - 0.5 (0.9 | 0.008 | 4.1 (1.4) | -0.4 (0.9) | 0.025 | |

| 12th week | 4.6 (1.2) | 0.1 (0.6) | >0.05 | 4.7 (1.2) | 0.2 (1.0) | >0.05 | |

| Cortisol | |||||||

| 1st week | 165.7 (64.8) | 154.6 (50.1) | >0.05 | ||||

| 6th week | 131.0 (44.9) | -34.8 (50.6) | 0.003 | 139.8 (52.6) | 14.8 (36.4) | >0.05 | |

| 12th week | 137.5 (48.4) | -28.2 (38.4) | 0.002 | 132.7 (61.3) | 22.0 (58.1) | >0.05 | |

| hs-CRP | |||||||

| 1st week | 20.2 (21.7) | 9.1 (0.0) | 0.02 | ||||

| 6th week | 21.6 (33.0) | 1.4 (32.0) | >0.05 | 7.9 (11.0) | -1.2 (10.2) | >0.05 | |

| 12th week | 16.8 (20.8) | -3.4 (16.3) | >0.05 | 10.3 (12.0) | 1.2 (12.5) | >0.05 | |

| IgA | |||||||

| 1st week | 2352.6 (895.1) | 2188.5 (1179.0) | >0.05 | ||||

| 6th week | 2352.4 (789.8) | -0.3 (608.1) | >0.05 | 2515.4 (1304.1) | 327.9 (1266.7) | >0.05 | |

| 12th week | 2267.5 (782.4) | -85.2 (377.1) | >0.05 | 2213.8 (952.1) | 25.4 (780.4) | >0.05 | |

| IL-6 | |||||||

| 1st week | 4.3 (2.6) | 3.0 (1.8) | 0.045 | ||||

| 6th week | 2.5 (2.0) | -1.8 (2.6) | <0.002 | 1.5 (0.9) | -1.6 (2.2) | 0.001 | |

| 12th week | 2.9 (1.9) | -1.3 (2.9) | 0.03 | 2.9 (2.5) | -0.2 (3.4) | >0.05 | |

| Folate | |||||||

| 1st week | 7.9 (3.7) | 7.7 (3.7) | >0.05 | ||||

| 6th week | 6.8 (3.3) | -1.1 (2.1) | 0.012 | 7.7 (5.7) | -0.1 (1.9) | >0.05 | |

| 12th week | 5.7 (3.4) | -2.2 (2.2) | <0.001 | 5.5 (3.8) | -2.2 (3.2) | 0.004 | |

| VitB12 | |||||||

| 1st week | 468.7 (115.5) | 488.8 (187.5) | >0.05 | ||||

| 6th week | 502.3 (103.3) | 33.6 (83.4) | >0.05 | 511.6 (169.2) | 22.8 (120.4) | >0.05 | |

| 12th week | 522.7 (114.4) | 54.0 (118.7) | 0.036 | 506.8 (121.3) | 18.0 (93.6) | >0.05 | |

| VitD | |||||||

| 1st week | 23.5 (9.1) | 23.3 (8.2) | >0.05 | ||||

| 6th week | 22.3 (8.5) | -1.2 (3.0) | >0.05 | 24.0 (8.3) | 0.7 (4.1) | >0.05 | |

| 12th week3 | 25.9 (6.2) | 2.4 (7.7) | >0.05 | 25.1 (5.2) | 1.7 (6.7) | >0.05 | |

| TAC | |||||||

| 1st week | 0.8 (0.2) | 0.8 (0.2) | |||||

| 6th week | 0.9 (0.2) | 0.04 (0.1) | >0.05 | 0.8 (0.2) | 0.03 (0.1) | >0.05 | >0.05 |

| 12th week | 0.9 (0.2) | 0.06 (0.1) | 0.026 | 0.9 (0.2) | 0.05 (0.1) | >0.05 | |

| Probiotics group (n=24) | Placebo group (n=22) | pb | |||||

| Urine Magnesium | mean (SD) | Δ from baseline | pa | mean (SD) | Change | pa | |

| 1st week | 11.0 (5.7) | 9.8 (7.7) | 0.022 | ||||

| 6th week | 7.9 (3.9) | -3.05 (5.6) | 0.01 | 8.2 (7.4) | -1.7 (9.7) | >0.05 | |

| 12th week | 10.4 (6.6) | -0.6 (8.2) | >0.05 | 9.0 (6.2) | -0.9 (6.4) | >0.05 | |

| Urine Phosphorus | |||||||

| 1st week | 103.7 (54.0) | 98.8 (44.8) | >0.05 | ||||

| 6th week | 105.0 (45.4) | 1.3 (50.3) | >0.05 | 91.0 (41.3) | -7.7 (54.8) | >0.05 | |

| 12th week | 106.1 (66.3) | 2.4 (50.6) | >0.05 | 120.9 (59.3) | 22.1 (73.8) | >0.05 | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).