Submitted:

05 April 2025

Posted:

08 April 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

INTRODUCTION

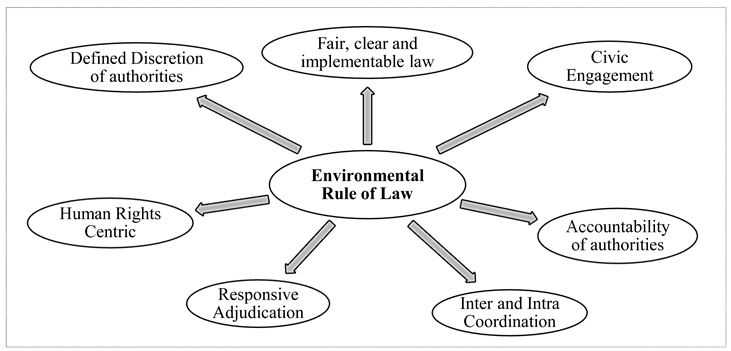

- Fair, clear and implementable environmental laws: environmental laws should be fair and non-discriminatory in their development, application and impact, it should be unambiguously understandable and could be implemented to effectively address institutional, cultural and economic context of the nation.

- Right to information, civic involvement and right to justice: right to information enables citizenry to identify environmental violations and determine the methodology to get engaged. Civic involvement in environmental decision-making contributes in formulation of fair and implementable laws and improves public support and compliance. Right to justice calibrates right to environmental information, per Principle 10 of the Rio Declaration, and civic participation and access of people to the adjudicating authorities for enforcement of their rights and resolving disputes.

- Accountability and integrity of institutions and decision makers: environmental institutions must demonstrate accountability, transparency and integrity to ensure public support and compliance and to deliver effective environmental protection.

- Clear and coordinated mandates and roles, across and within institutions: environmental governance is carried out through multiple normative agencies (statutory, customary, and religious), levels (international, national and local) and sectors (air, water, forest, agriculture, waste management etc.) resulting in institutional overlap and gaps. Clear mandates and cross-sectoral coordination are essential for effective implementation of environmental laws.

- Accessible, fair, impartial, timely and responsive adjudication: dispute resolution and enforcement mechanisms that are fair, impartial, timely and responsive increase compliance with environmental regulations and support environmental initiatives and civic trust in the judicial process.

- Recognition of the mutually reinforcing relationship with human rights: environmental rule of law has a mutually reinforcing relationship with constitutional, human and other rights. A healthy environment is necessary for realizing rights to life, property and health as well as cultural, economic and political rights. Constitutional, human and other rights including both substantive and procedural rights provide tools for strengthening and enforcing environmental protection. And

- Specific criteria for the interpretation on environmental law: clear and detailed guidance on environmental laws enable implanting agencies to adopt consistent regulations and enforcement practices and facilitate compliance on the part of regulated communities and the public.

CIVIC RIGHTS TO PARTICIPATE IN THE DEVELOPMENTAL ACTIVITIES

CIVIC RIGHTS TO INFORMATION RELATING TO ENVIRONMENTAL IMPACTS OF DEVELOPMENTAL ACTIVITIES

GOVERNMENT PLANS FOR THE CONSERVATION OF GIBs

JUDICIAL OBSERVATION ON THE CONSERVATION OF GIBs

“Acknowledging that climate change is a common concern of humankind, Parties should, when taking action to address climate change, respect, promote and consider their respective obligations on human rights, the right to health, the rights of indigenous peoples, local communities, migrants, children, persons with disabilities and people in vulnerable situations and the right to development, as well as gender equality, empowerment of women and intergenerational equity.”

CONCLUDING REMARKS

- Habitat of the GIBs should be protected and improved by incentivizing local community members;

- Habitat of the GIBs should be protected from the predators by capturing and trans-locating predators from the habitat areas of the GIBs;

- Domestic animal grazing should be banned within the region declared for the habitat of GIBs;

- Use of pesticides in the agricultural fields should discouraged by awaking and incentivizing peasants nearby the habitat of GIBs;

- Incentivizing local farmers to use their lands in a manner that is bustard-friendly;

- Local community members should be encouraged and involved to collect eggs of GIBs outside the GIBs sanctuaries and return them to the captive incubation centers;

- Installation of birds diverting tools on the overhead power transmission line and wind turbines should be promoted and caliberized periodically and effectively;

- Captive GIBs breading and incubation should be advanced at the ex-situ centers established and managed by the government agencies or private centers that are controlled by the government agencies; and

- Installation of bird diverters on the overhead power transmission lines and wind turbines.

PROSPECTS OF FUTURE RESEARCH AND DEVELOPMENT

| 1 | Ajoy Sinha Karpuram, “How Supreme Court is overseeing conservation of the Great Indian Bustard,” The Indian Express. March 27, 2024. Accessed from https://indianexpress.com/article/explained/explained-law/supreme-court-conservation-great-indian-bustard-9234896/

|

| 2 | Wildlife Institute of India, Habitat improvement and conservation breeding of great Indian bustard: an integrated approach. Accessed from https://wii.gov.in/campa_gib

|

| 3 | Supra note 1. |

| 4 | The Wildlife (Protection) Act, 1972. Section 9. |

| 5 | Ibid. Section 51. |

| 6 | Wildlife Institute of India 2018 Power-Line Mitigation Measures. Second edition (2020). Accessed from https://wii.gov.in/images//images/documents/publications/rr_2020_GIB%20Power-line_mitigation_conserve_bustards.pdf

|

| 7 | Courtney Taylor Hamara, “The Concept of the Rule of Law,” in I. B. Flores, K. E. Himma (eds.), Law, Liberty, and the Rule of Law 11–26 (Springer Netherlands, Dordrecht, 2013), xviii. |

| 8 | J. Hampton, “Democracy and the rule of law,” in I. Shapiro (ed.), The Rule of Law Nomos XXXVI (New York University Press, London, 1994). |

| 9 | Imer B. Flores and Kenneth Einar Himma, “Introduction,” in I. B. Flores, Kenneth E. Himma (eds.), Law, Liberty, and the Rule of Law 1–9 (Springer Netherlands, Dordrecht, 2013), xviii. Accessed from https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-007-4743-2_1

|

| 10 | Lord Bingham, “The Rule of Law,” 66 The Cambridge Law Journal 67–85 (2007). Accessed from https://doi.org/10.1017/S0008197307000037

|

| 11 | Courtney Taylor Hamara, “The Concept of the Rule of Law,” in I. B. Flores, K. E. Himma (eds.), Law, Liberty, and the Rule of Law 11–26 (Springer Netherlands, Dordrecht, 2013), xviii. |

| 12 | United Nations Secretary-General, The Rule of Law and Transitional Justice in Conflict and Post-Conflict Societies 1–24 (United Nations Security Council, New York, 2004). |

| 13 | Lon L. Fuller, The Morality of Law, Rev. ed (Yale University Press, New Haven, 1977). |

| 14 | Christina Voigt (ed.), Rule of Law for Nature: New Dimensions and Ideas in Environmental Law (Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, United Kingdom, 2013). |

| 15 | Louis J. Kotzé, “Six Constitutional Elements for Implementing Environmental Constitutionalism in the Anthropocene,” 1st ed., in E. Daly, J. R. May (eds.), Implementing Environmental Constitutionalism 13–33 (Cambridge University Press, 2018). https://doi.org/10.1017/9781316691588.003

|

| 16 | United Nations Environment Programme, Environmental Rule of Law: Tracking Progress and Charting Future Directions 15 (United Nations Environment Programme, 2023). https://doi.org/10.59117/20.500.11822/43943

|

| 17 | United Nations Environment Programme, Environmental Rule of Law: Tracking Progress and Charting Future Directions 17 (United Nations Environment Programme, 2023). https://doi.org/10.59117/20.500.11822/43943; Carl Bruch, Environmental Rule of Law: First Global Report (United Nations Environment Programme, Nairobi, 2019). |

| 18 | United Nations Environment Programme, Environmental Rule of Law: Critical to Sustainable Development (Issue Brief). (March 2015). (United Nations Environment Programme. 2015). Accessed from https://wedocs.unep.org/handle/20.500.11822/10664

|

| 19 | United Nations Environment Programme, Environmental Rule of Law: Tracking Progress and Charting Future Directions 17 (United Nations Environment Programme, 2023). https://doi.org/10.59117/20.500.11822/43943; UNEP. (2015). United Nations Environment Programme, Environmental Rule of Law: Critical to Sustainable Development (Issue Brief). (March 2015). (United Nations Environment Programme. 2015). Accessed from https://wedocs.unep.org/handle/20.500.11822/10664

|

| 20 | Saman Narayan Upadhyay, “Global Legal Norms on Environment and Sustainable Development in 21st Century,” in R. Prasad, M. K. Jhariya, et al. (eds.), Advances in sustainable development and management of environmental and natural resources. 59–107 (Apple Academic Press, Palm Bay, FL, USA, 2022), ii. |

| 21 | The Universal Declaration of Human Rights, 1948. Article 22. Accessed from https://www.ohchr.org/sites/default/files/UDHR/Documents/UDHR_Translations/eng.pdf

|

| 22 | Ibid. Article 26. |

| 23 | Id. Article 29 (1). |

| 24 | The International Covenant on the social, economic and cultural rights, 1966. Article 1 (1). Accessed from https://www.ohchr.org/en/instruments-mechanisms/instruments/international-covenant-economic-social-and-cultural-rights

|

| 25 | Ibid. Article 6(2). |

| 26 | Id. Article 11(2)(b). |

| 27 | Id. Article 13(2)(e). |

| 28 | The United Nations Declaration on the Right to Development, 1986. Article 1(1). Accessed from https://www.ohchr.org/sites/default/files/rtd.pdf

|

| 29 | Ibid. Article 2(1). |

| 30 | Id. Article 2(2). |

| 31 | Id. Article 2(3). |

| 32 | Id. Article 1(2). |

| 33 | Id. Article 3(1). |

| 34 | Id. Article 4(1). |

| 35 | Id. Article 5. |

| 36 | Id. Article 8(1). |

| 37 | Id. Article 8(2). |

| 38 | Saman Narayan Upadhyay and Milendra Singh, “Community participation in wildlife conservation to promote environmental constitutionalism and sustainability in India,” 10 International journal for Innovative Research in Multidisciplinary Field 224–32 (2024). https://doi.org/10.2015/IJIRMF/202401036

|

| 39 | Saman Narayan Upadhyay and Milendra Singh, “Environmental clearance and sustainable development: changing paradigm of environmental constitutionalism in Indian” The Journal of Multidisciplinary Research 8–18 (2024). https://doi.org/10.37022/tjmdr.v4i1.560

|

| 40 | Ibid. |

| 41 | Id. |

| 42 | Supra note 2. |

| 43 | Writ Petition (Civil) No. 838 of 2019 along with Civil Appeal No. 3570 of 2022. Accessed from https://main.sci.gov.in/supremecourt/2019/20754/20754_2019_1_25_51677_Judgement_21-Mar-2024.pdf

|

| 44 | The court has already ruled in Virender Gaur v. State of Haryana, (1995) 2 SCC 577 that “The State, in particular has duty in that behalf and to shed its extravagant unbridled sovereign power and to forge in its policy to maintain ecological balance and hygienic environment.”

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions, and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions, or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).