Submitted:

06 April 2025

Posted:

08 April 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

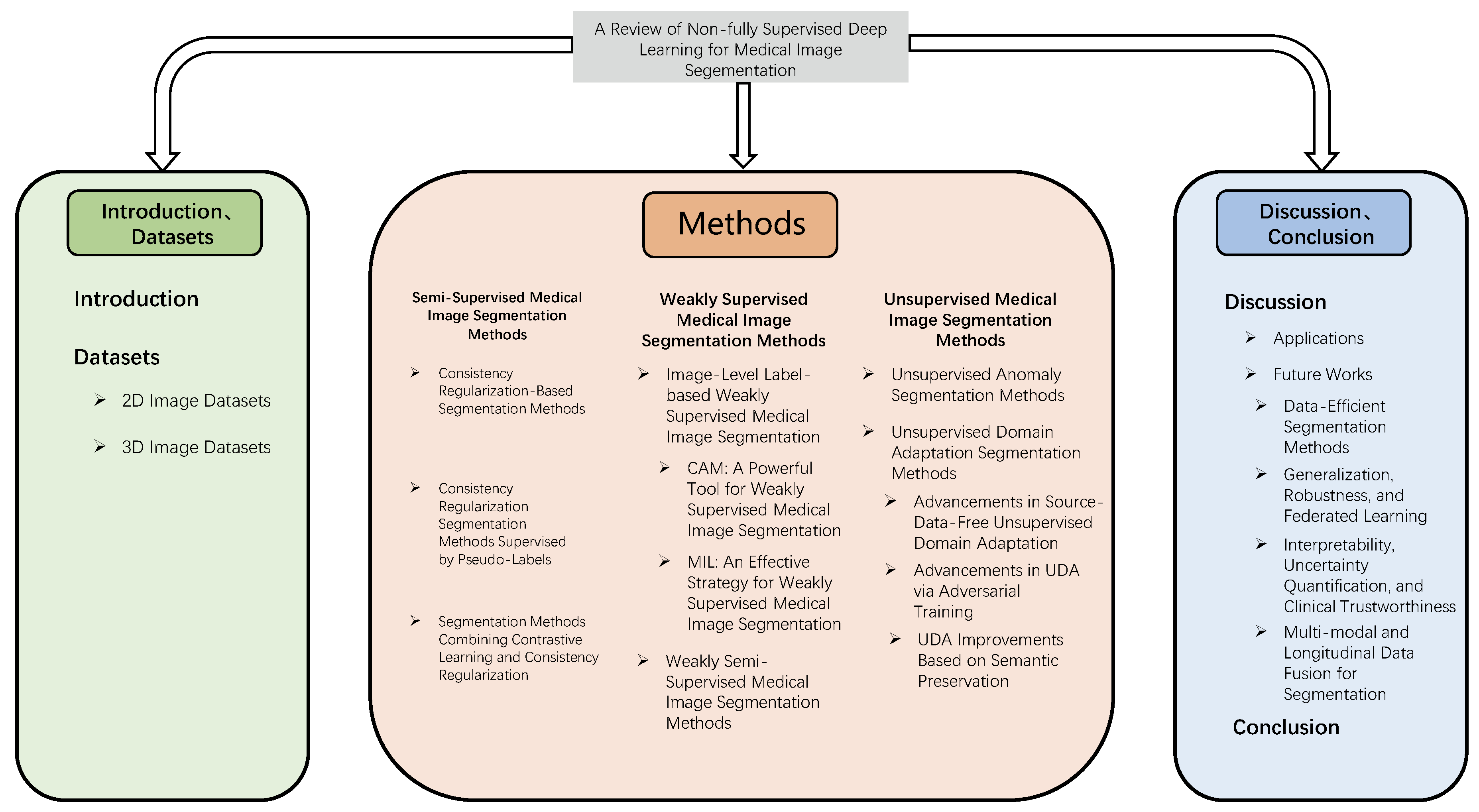

1. Introduction

2. Datasets

2.1. 2D Image Datasets

2.2. 3D Image Datasets

3. Semi-Supervised Medical Image Segmentation Methods

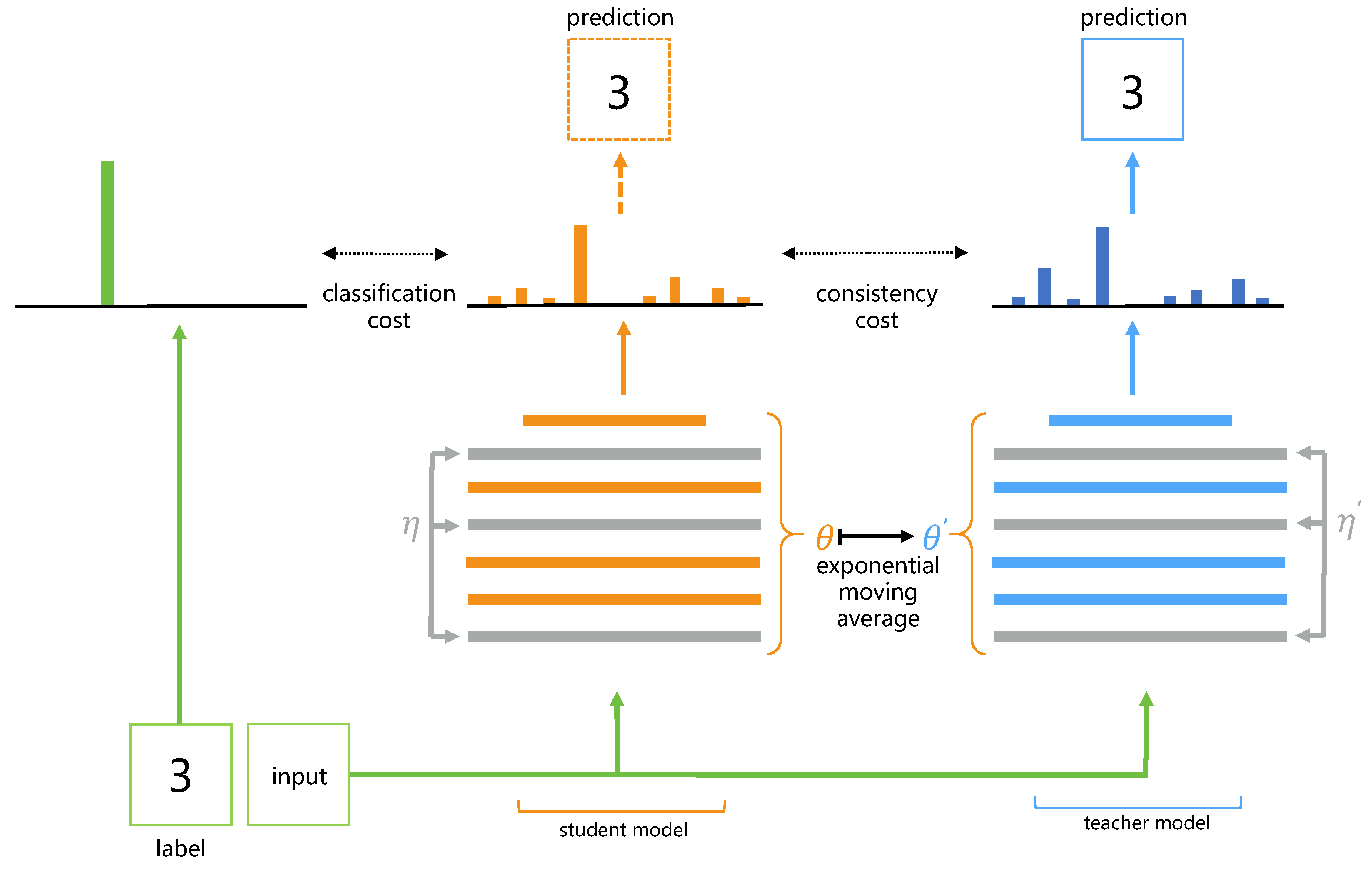

3.1. Consistency Regularization-Based Segmentation Methods

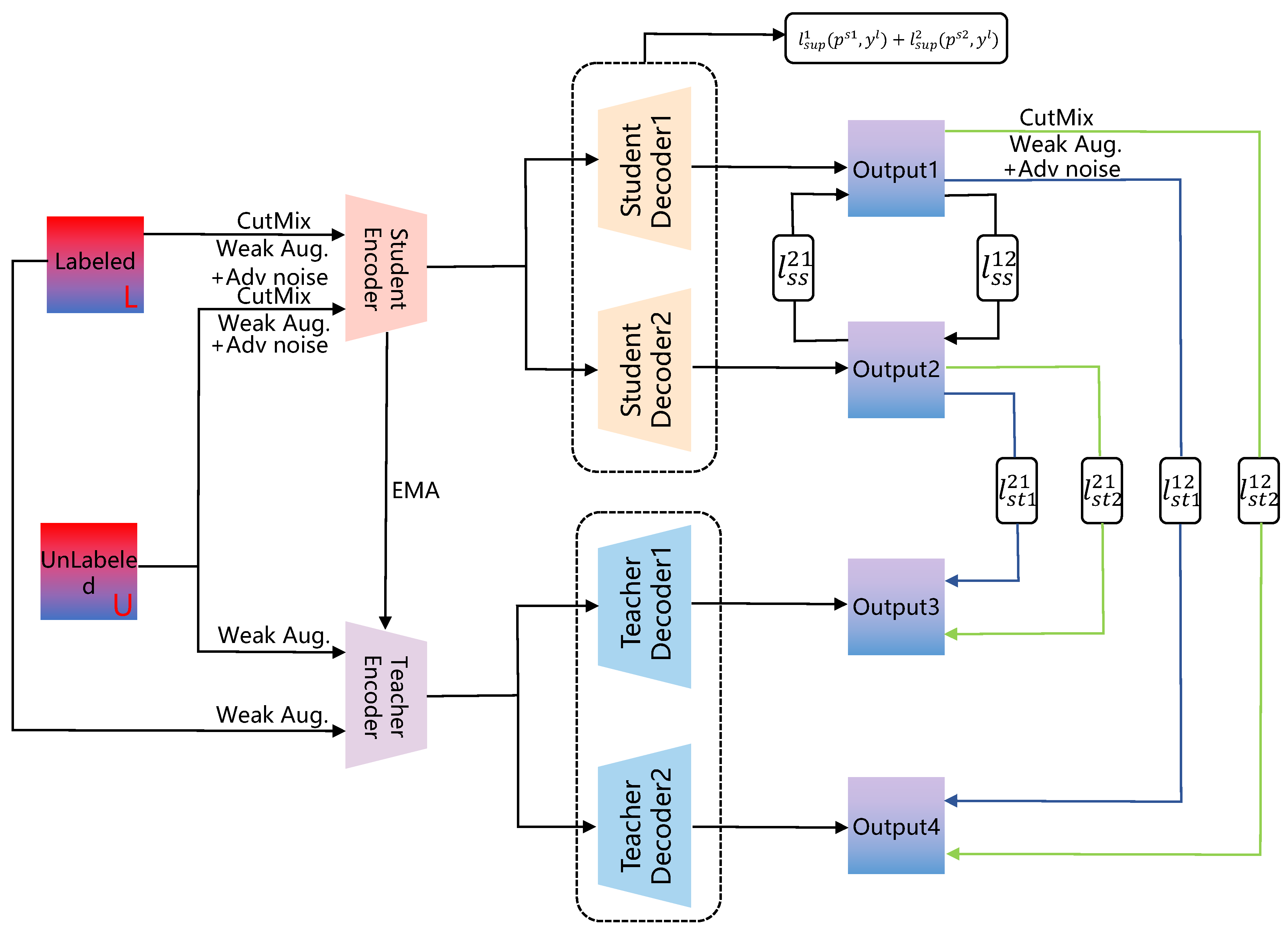

3.2. Consistency Regularization Segmentation Methods Supervised by Pseudo-Labels

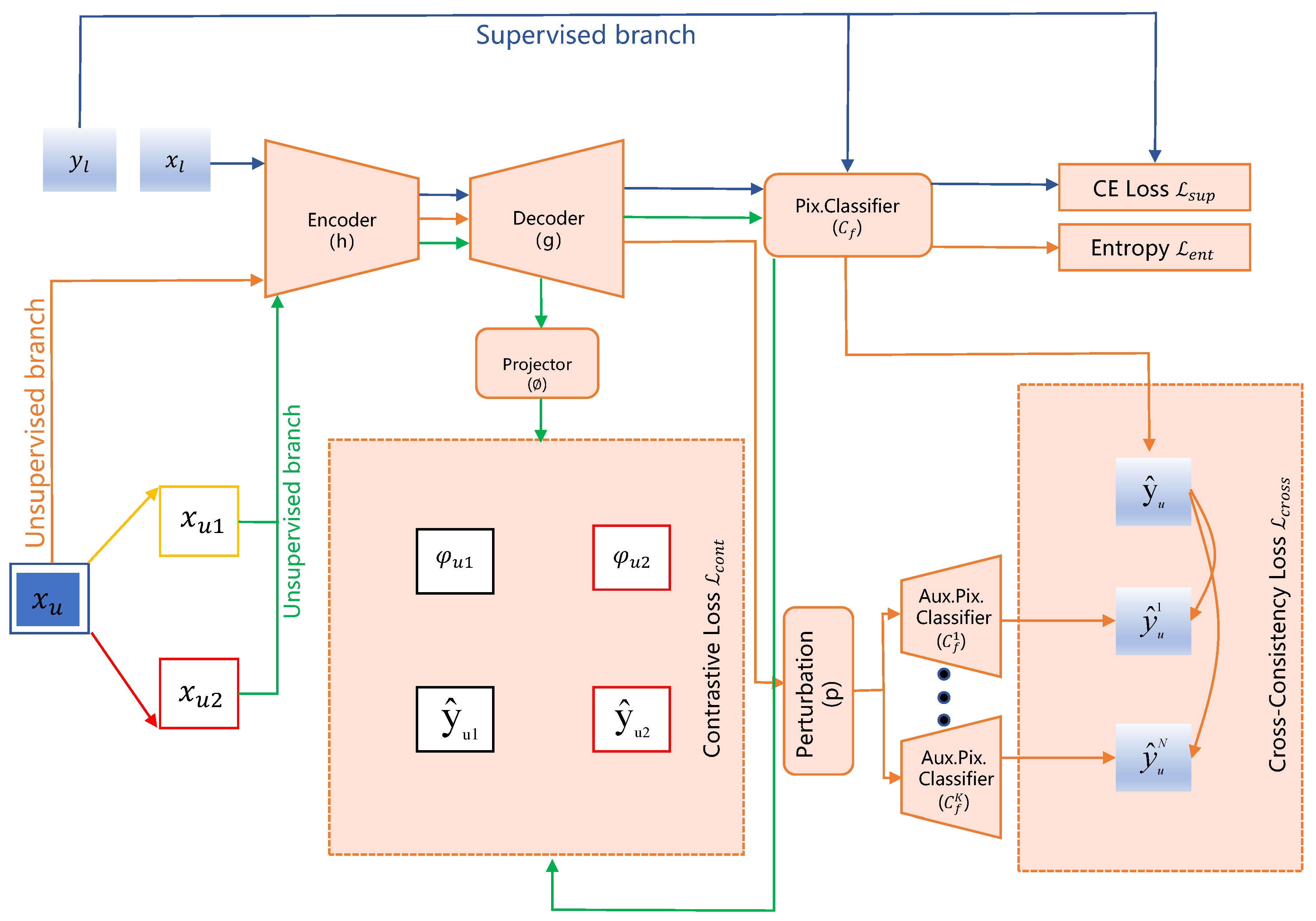

3.3. Segmentation Methods Combining Contrastive Learning and Consistency Regularization

- Context-aware Consistency Path (Green path): Two overlapping patches, and , cropped from the unlabeled image are passed through the shared backbone network. Their resulting features are mapped through a projection head () to obtain embeddings and . A contrastive loss, , is employed to enforce feature consistency under differing contextual views.

- Cross-Consistency Training Path (Brown path): Features extracted from the complete unlabeled image are fed into the main classifier to yield prediction . Concurrently, these features, subjected to perturbation (P), are input to multiple auxiliary classifiers, producing predictions . A cross-consistency loss, , enforces consistency between the outputs of the main and auxiliary classifiers.

4. Weakly Supervised Medical Image Segmentation Methods

4.1. Image-Level Label-Based Weakly Supervised Medical Image Segmentation

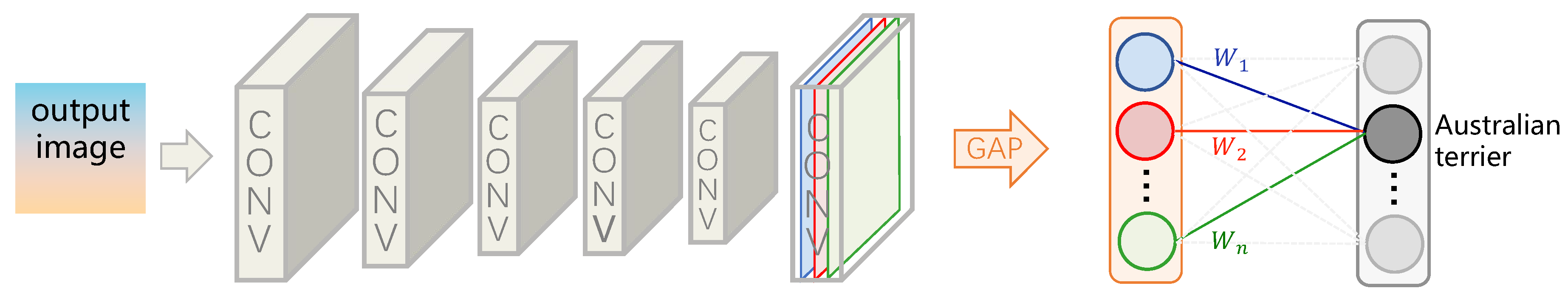

4.1.1. CAM: A Powerful Tool for Weakly Supervised Medical Image Segmentation

| Algorithm 1:Training algorithm. |

Require: Training dataset

|

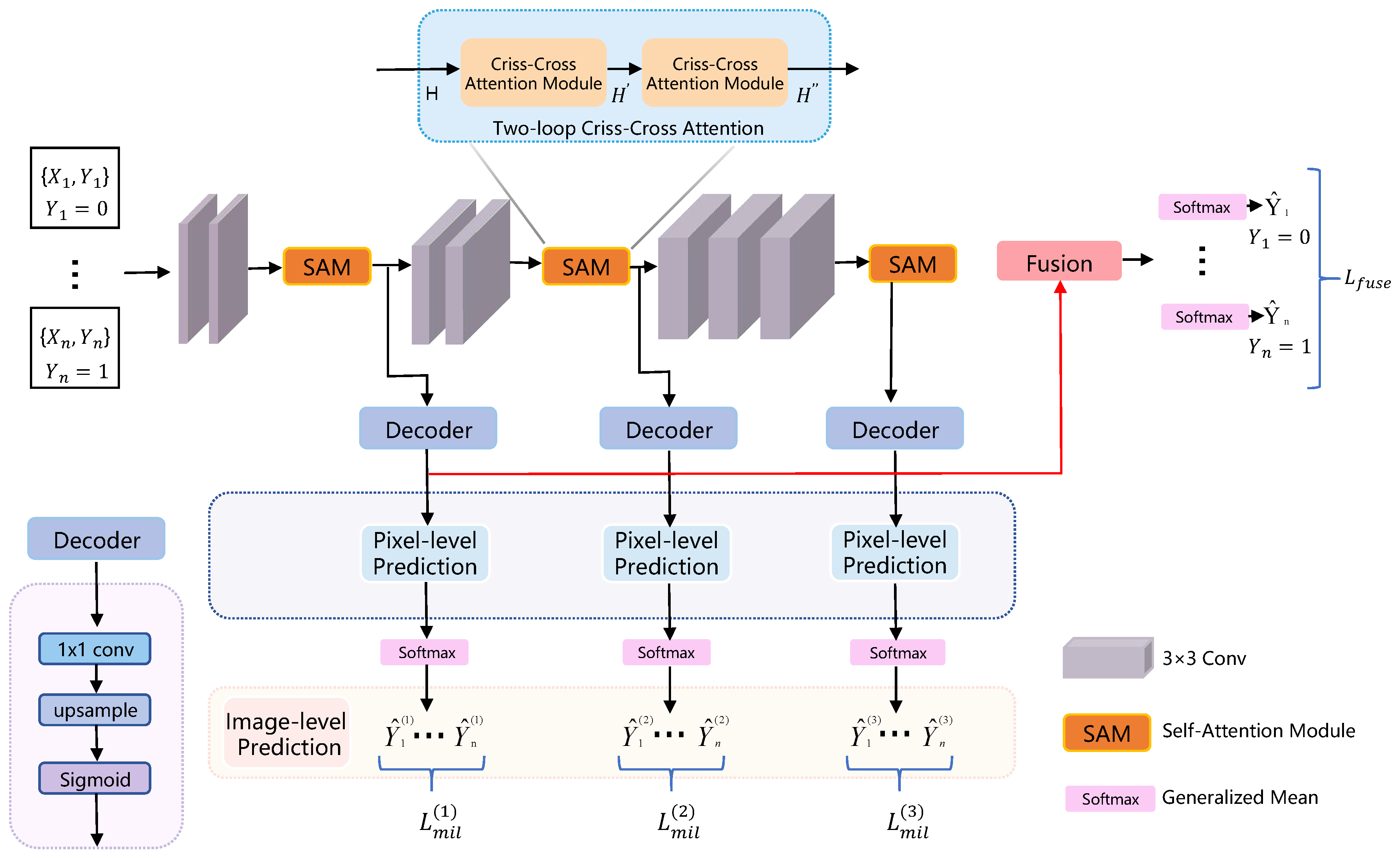

4.1.2. MIL: An Effective Strategy for Weakly Supervised Medical Image Segmentation

4.2. Weakly Semi-Supervised Medical Image Segmentation Methods

5. Unsupervised Medical Image Segmentation Methods

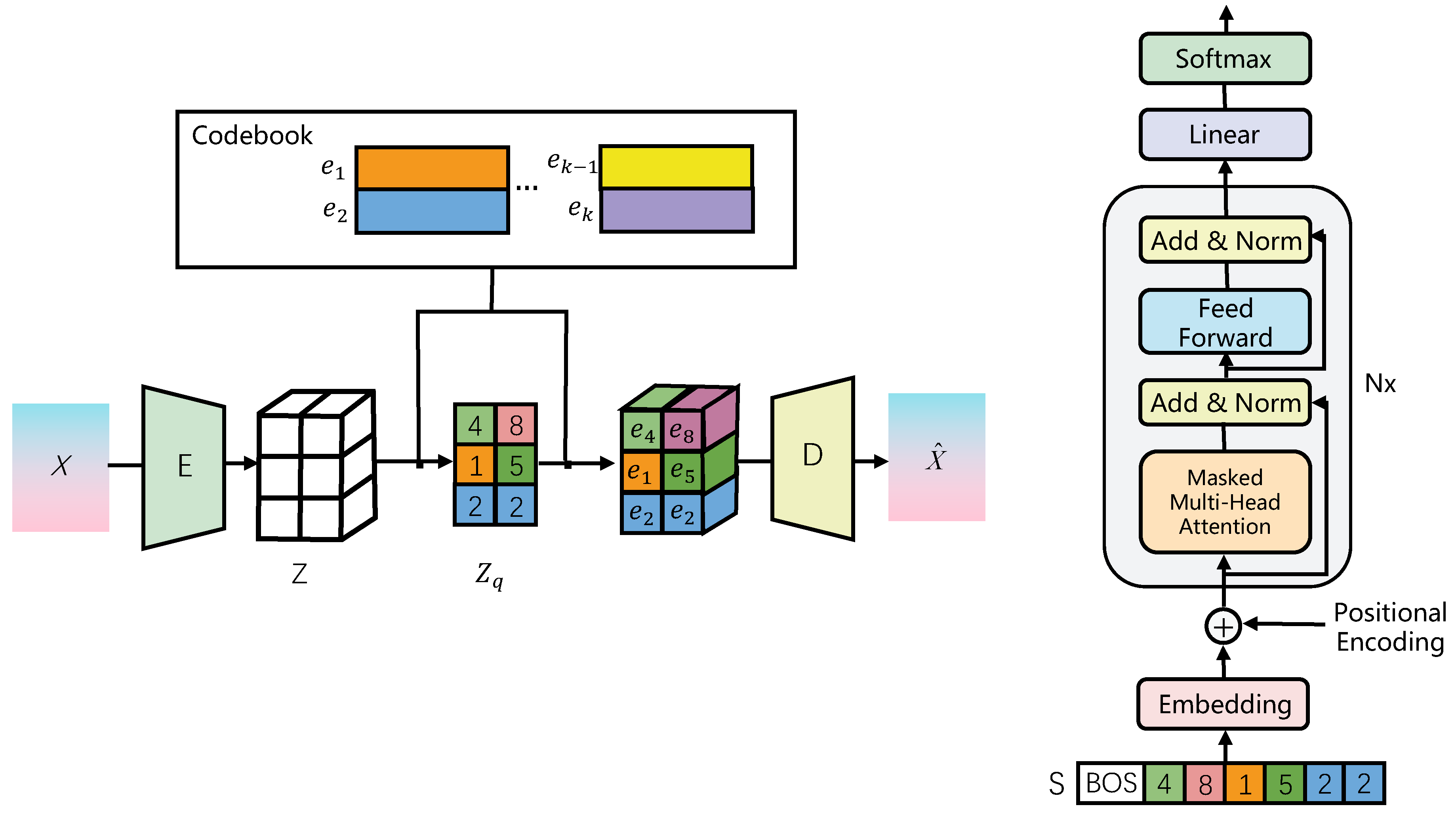

5.1. Unsupervised Anomaly Segmentation Methods

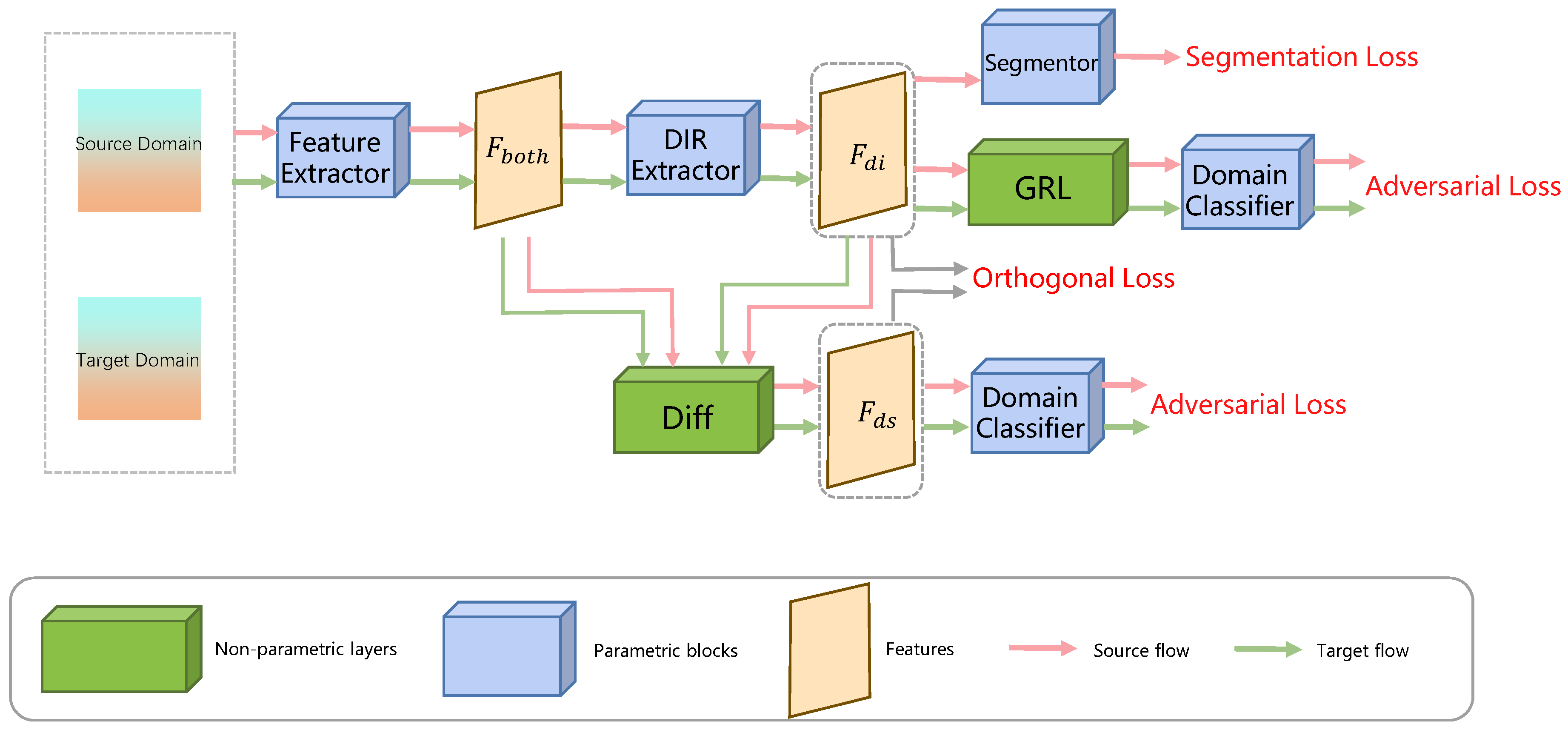

5.2. Unsupervised Domain Adaptation Segmentation Methods

5.2.1. Advancements in Source-Data-Free Unsupervised Domain Adaptation

5.2.2. Advancements in UDA via Adversarial Training

5.2.3. UDA Improvements Based on Semantic Preservation

6. Discussion

6.1. Applications

6.2. Future Works

6.2.1. Data-Efficient Segmentation Methods

6.2.2. Generalization, Robustness, and Federated Learning

6.2.3. Interpretability, Uncertainty Quantification, and Clinical Trustworthiness

6.2.4. Multi-Modal and Longitudinal Data Fusion for Segmentation

7. Conclusion

Author Contributions

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Krizhevsky, A.; Sutskever, I.; Hinton, G.E. ImageNet classification with deep convolutional neural networks. Communications of the ACM 2012, 60, 84–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Long, J.; Shelhamer, E.; Darrell, T. Fully Convolutional Networks for Semantic Segmentation, 2015.

- Ronneberger, O.; Fischer, P.; Brox, T. U-Net: Convolutional Networks for Biomedical Image Segmentation. Lecture Notes in Computer Science (including subseries Lecture Notes in Artificial Intelligence and Lecture Notes in Bioinformatics) 2015, 9351, 234–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaswani, A.; Shazeer, N.; Parmar, N.; Uszkoreit, J.; Jones, L.; Gomez, A.N. Attention Is All You Need. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Kirillov, A.; Mintun, E.; Ravi, N.; Mao, H.; Rolland, C.; Gustafson, L.; Xiao, T.; Whitehead, S.; Berg, A.C.; Lo, W.Y.; et al. Segment Anything, 2023.

- Baur, C.; Wiestler, B.; Albarqouni, S.; Navab, N. Deep autoencoding models for unsupervised anomaly segmentation in brain MR images. Lecture Notes in Computer Science (including subseries Lecture Notes in Artificial Intelligence and Lecture Notes in Bioinformatics), 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yarkony, J.; Wang, S.; Inc, B. Accelerating Message Passing for MAP with Benders Decomposition 2018.

- Zhou, B.; Khosla, A.; Lapedriza, A.; Oliva, A.; Torralba, A. Learning Deep Features for Discriminative Localization, 2016.

- Dai, J.; He, K.; Sun, J. BoxSup: Exploiting Bounding Boxes to Supervise Convolutional Networks for Semantic Segmentation, 2015.

- Ballan, L.; Castaldo, F.; Alahi, A.; Palmieri, F.; Savarese, S. Knowledge transfer for scene-specific motion prediction. Lecture Notes in Computer Science (including subseries Lecture Notes in Artificial Intelligence and Lecture Notes in Bioinformatics). [CrossRef]

- Tanaka, K. Minimal networks for sensor counting problem using discrete Euler calculus. Japan Journal of Industrial and Applied Mathematics 2017, 34, 229–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, Y.; Feng, J.; Liang, X.; Cheng, M.M.; Zhao, Y.; Yan, S. Object Region Mining With Adversarial Erasing: A Simple Classification to Semantic Segmentation Approach, 2017.

- Hu, F.; Wang, Y.; Ma, B.; Wang, Y. Emergency supplies research on crossing points of transport network based on genetic algorithm. Proceedings - 2015 International Conference on Intelligent Transportation, Big Data and Smart City, ICITBS 2015. [CrossRef]

- Gannon, S.; Kulosman, H. The condition for a cyclic code over Z4 of odd length to have a complementary dual 2019.

- Abraham, N.; Khan, N.M. A novel focal tversky loss function with improved attention u-net for lesion segmentation. Proceedings - International Symposium on Biomedical Imaging. [CrossRef]

- Bernard, O.; Lalande, A.; Zotti, C.; Cervenansky, F.; Yang, X.; Heng, P.A.; Cetin, I.; Lekadir, K.; Camara, O.; Ballester, M.A.G.; et al. Deep Learning Techniques for Automatic MRI Cardiac Multi-Structures Segmentation and Diagnosis: Is the Problem Solved? IEEE Transactions on Medical Imaging 2018, 37, 2514–2525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graham, S.; Chen, H.; Gamper, J.; Dou, Q.; Heng, P.A.; Snead, D.; Tsang, Y.W.; Rajpoot, N. MILD-Net: Minimal information loss dilated network for gland instance segmentation in colon histology images. Medical image analysis 2019, 52, 199–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demner-Fushman, D.; Kohli, M.D.; Rosenman, M.B.; Shooshan, S.E.; Rodriguez, L.; Antani, S.; Thoma, G.R.; McDonald, C.J. Preparing a collection of radiology examinations for distribution and retrieval. Journal of the American Medical Informatics Association : JAMIA 2016, 23, 304–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, A.E.; Pollard, T.J.; Berkowitz, S.J.; Greenbaum, N.R.; Lungren, M.P.; ying Deng, C.; Mark, R.G.; Horng, S. MIMIC-CXR, a de-identified publicly available database of chest radiographs with free-text reports. Scientific data 2019, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Li, D.; Xu, C.; Wang, W.; Hong, Q.; Li, Q.; Tian, J. TFCNs: A CNN-Transformer Hybrid Network for Medical Image Segmentation. Lecture Notes in Computer Science (including subseries Lecture Notes in Artificial Intelligence and Lecture Notes in Bioinformatics), 3532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bannur, S.; Hyland, S.; Liu, Q.; Pérez-García, F.; Ilse, M.; Castro, D.C.; Boecking, B.; Sharma, H.; Bouzid, K.; Thieme, A.; et al. Learning to Exploit Temporal Structure for Biomedical Vision-Language Processing. Proceedings of the IEEE Computer Society Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, 1501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCollough, C.H.; Bartley, A.C.; Carter, R.E.; Chen, B.; Drees, T.A.; Edwards, P.; Holmes, D.R.; Huang, A.E.; Khan, F.; Leng, S.; et al. Low-dose CT for the detection and classification of metastatic liver lesions: Results of the 2016 Low Dose CT Grand Challenge. Medical physics 2017, 44, e339–e352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leuschner, J.; Schmidt, M.; Baguer, D.O.; Maass, P. LoDoPaB-CT, a benchmark dataset for low-dose computed tomography reconstruction. Scientific Data 2021 8:1 2021, 8, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moen, T.R.; Chen, B.; Holmes, D.R.; Duan, X.; Yu, Z.; Yu, L.; Leng, S.; Fletcher, J.G.; McCollough, C.H. Low-dose CT image and projection dataset. Medical physics 2021, 48, 902–911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, Z.; Xia, Q.; Hu, Z.; Huang, N.; Bian, C.; Zheng, Y.; Vesal, S.; Ravikumar, N.; Maier, A.; Yang, X.; et al. A global benchmark of algorithms for segmenting the left atrium from late gadolinium-enhanced cardiac magnetic resonance imaging. Medical Image Analysis 2021, 67, 101832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clark, K.; Vendt, B.; Smith, K.; Freymann, J.; Kirby, J.; Koppel, P.; Moore, S.; Phillips, S.; Maffitt, D.; Pringle, M.; et al. The cancer imaging archive (TCIA): Maintaining and operating a public information repository. Journal of Digital Imaging 2013, 26, 1045–1057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Menze, B.H.; Jakab, A.; Bauer, S.; Kalpathy-Cramer, J.; Farahani, K.; Kirby, J.; Burren, Y.; Porz, N.; Slotboom, J.; Wiest, R.; et al. The Multimodal Brain Tumor Image Segmentation Benchmark (BRATS). IEEE Transactions on Medical Imaging 2015, 34, 1993–2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liew, S.Q.; Ngoh, G.C.; Yusoff, R.; Teoh, W.H. Acid and Deep Eutectic Solvent (DES) extraction of pectin from pomelo (Citrus grandis (L.) Osbeck) peels. Biocatalysis and Agricultural Biotechnology 2018, 13, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petzsche, M.R.H.; de la Rosa, E.; Hanning, U.; Wiest, R.; Valenzuela, W.; Reyes, M.; Meyer, M.; Liew, S.L.; Kofler, F.; Ezhov, I.; et al. ISLES 2022: A multi-center magnetic resonance imaging stroke lesion segmentation dataset. Scientific data 2022, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maier, O.; Menze, B.H.; von der Gablentz, J.; Häni, L.; Heinrich, M.P.; Liebrand, M.; Winzeck, S.; Basit, A.; Bentley, P.; Chen, L.; et al. ISLES 2015 - A public evaluation benchmark for ischemic stroke lesion segmentation from multispectral MRI. Medical Image Analysis 2017, 35, 250–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hakim, A.; Christensen, S.; Winzeck, S.; Lansberg, M.G.; Parsons, M.W.; Lucas, C.; Robben, D.; Wiest, R.; Reyes, M.; Zaharchuk, G. Predicting Infarct Core From Computed Tomography Perfusion in Acute Ischemia With Machine Learning: Lessons From the ISLES Challenge. Stroke 2021, 52, 2328–2337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, K.; Han, K.; Li, X.; Cheng, X.; Li, Y.; Wang, Y.; Yu, Y. Symmetry-Enhanced Attention Network for Acute Ischemic Infarct Segmentation with Non-contrast CT Images. Lecture Notes in Computer Science (including subseries Lecture Notes in Artificial Intelligence and Lecture Notes in Bioinformatics), 2907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campello, V.M.; Gkontra, P.; Izquierdo, C.; Martin-Isla, C.; Sojoudi, A.; Full, P.M.; Maier-Hein, K.; Zhang, Y.; He, Z.; Ma, J.; et al. Multi-Centre, Multi-Vendor and Multi-Disease Cardiac Segmentation: The MMs Challenge. IEEE Transactions on Medical Imaging 2021, 40, 3543–3554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heller, N.; Isensee, F.; Maier-Hein, K.H.; Hou, X.; Xie, C.; Li, F.; Nan, Y.; Mu, G.; Lin, Z.; Han, M.; et al. The state of the art in kidney and kidney tumor segmentation in contrast-enhanced CT imaging: Results of the KiTS19 challenge. ElsevierN Heller, F Isensee, KH Maier-Hein, X Hou, C Xie, F Li, Y Nan, G Mu, Z Lin, M Han, G YaoMedical image analysis, 2021•Elsevier 2021, 67, 101821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Littlejohns, T.J.; Holliday, J.; Gibson, L.M.; Garratt, S.; Oesingmann, N.; Alfaro-Almagro, F.; Bell, J.D.; Boultwood, C.; Collins, R.; Conroy, M.C.; et al. The UK Biobank imaging enhancement of 100,000 participants: rationale, data collection, management and future directions. nature.comTJ Littlejohns, J Holliday, LM Gibson, S Garratt, N Oesingmann, F Alfaro-Almagro, JD BellNature communications, 2020•nature.com 2020, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bilic, P.; Christ, P.; Li, H.B.; Vorontsov, E.; Ben-Cohen, A.; Kaissis, G.; Szeskin, A.; Jacobs, C.; Mamani, G.E.H.; Chartrand, G.; et al. The Liver Tumor Segmentation Benchmark (LiTS). Medical Image Analysis 2023, 84, 102680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kavur, A.E.; Gezer, N.S.; Barış, M.; Aslan, S.; Conze, P.H.; Groza, V.; Pham, D.D.; Chatterjee, S.; Ernst, P.; Özkan, S.; et al. CHAOS Challenge - combined (CT-MR) healthy abdominal organ segmentation. Medical image analysis 2021, 69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, P.; Zhang, B.; Chen, D.; Yuan, L.; Wen, F. Cross-domain correspondence learning for exemplar-based image translation. Proceedings of the IEEE Computer Society Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, 5142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sohn, K.; Berthelot, D.; Li, C.L.; Zhang, Z.; Carlini, N.; Cubuk, E.D.; Kurakin, A.; Zhang, H.; Raffel, C. FixMatch: Simplifying Semi-Supervised Learning with Consistency and Confidence. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, H.; Tao, R.; Fan, Y.; Wang, Y.; Wang, J.; Schiele, B.; Xie, X.; Raj, B.; Savvides, M. SoftMatch: Addressing the Quantity-Quality Trade-off in Semi-supervised Learning. 11th International Conference on Learning Representations, ICLR 2023.

- Wang, X.; Tang, F.; Chen, H.; Cheung, C.Y.; Heng, P.A. Deep semi-supervised multiple instance learning with self-correction for DME classification from OCT images. Medical Image Analysis 2023, 83, 102673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tarvainen, A.; Valpola, H. Mean teachers are better role models: Weight-averaged consistency targets improve semi-supervised deep learning results. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems, 1196. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, L.; Qi, L.; Feng, L.; Zhang, W.; Shi, Y. Revisiting Weak-to-Strong Consistency in Semi-Supervised Semantic Segmentation, 2023.

- Lyu, F.; Ye, M.; Carlsen, J.F.; Erleben, K.; Darkner, S.; Yuen, P.C. Pseudo-Label Guided Image Synthesis for Semi-Supervised COVID-19 Pneumonia Infection Segmentation. IEEE Transactions on Medical Imaging 2023, 42, 797–809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bashir, R.M.S.; Qaiser, T.; Raza, S.E.; Rajpoot, N.M. Consistency regularisation in varying contexts and feature perturbations for semi-supervised semantic segmentation of histology images. Medical Image Analysis 2024, 91, 102997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Sun, G.; Zhang, T.; Wang, R.; Su, J. Semi-supervised medical image segmentation via weak-to-strong perturbation consistency and edge-aware contrastive representation. Medical Image Analysis 2025, 101, 103450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, X.; Chen, Y.; Wu, J.; Lu, J.; Ye, Y.; Huang, Y.; Dou, X.; Li, K.; Wang, G.; Zhang, S.; et al. A novel one-to-multiple unsupervised domain adaptation framework for abdominal organ segmentation. Medical Image Analysis 2023, 88, 102873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- V. , S.A.; Dolz, J.; Lombaert, H. Anatomically-aware uncertainty for semi-supervised image segmentation. Medical Image Analysis 2024, 91, 103011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, L.; Wang, S.; Li, X.; Fu, C.W.; Heng, P.A. Uncertainty-Aware Self-ensembling Model for Semi-supervised 3D Left Atrium Segmentation. Lecture Notes in Computer Science (including subseries Lecture Notes in Artificial Intelligence and Lecture Notes in Bioinformatics), 1765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, X.; Wang, G.; Liao, W.; Chen, J.; Song, T.; Chen, Y.; Zhang, S.; Metaxas, D.N.; Zhang, S. Semi-supervised medical image segmentation via uncertainty rectified pyramid consistency. Medical Image Analysis 2022, 80, 102517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Bian, R.; Zhao, W.; Xu, W.; Yang, H. Diversity matters: Cross-head mutual mean-teaching for semi-supervised medical image segmentation. Medical Image Analysis 2024, 97, 103302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, Y.; Ge, Z.; Zhang, D.; Xu, M.; Zhang, L.; Xia, Y.; Cai, J. Mutual consistency learning for semi-supervised medical image segmentation. Medical Image Analysis 2022, 81, 102530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bai, Y.; Chen, D.; Li, Q.; Shen, W.; Wang, Y. Bidirectional Copy-Paste for Semi-Supervised Medical Image Segmentation, 2023.

- Su, J.; Luo, Z.; Lian, S.; Lin, D.; Li, S. Mutual learning with reliable pseudo label for semi-supervised medical image segmentation. Medical Image Analysis 2024, 94, 103111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Milletari, F.; Navab, N.; Ahmadi, S.A. V-Net: Fully convolutional neural networks for volumetric medical image segmentation. Proceedings - 2016 4th International Conference on 3D Vision, 3DV 2016. [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Song, K.; Liu, Y.; Ma, S.; Yan, Y.; Carneiro, G. Leveraging labelled data knowledge: A cooperative rectification learning network for semi-supervised 3D medical image segmentation. Medical Image Analysis 2025, 101, 103461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaitanya, K.; Erdil, E.; Karani, N.; Konukoglu, E. Local contrastive loss with pseudo-label based self-training for semi-supervised medical image segmentation. Medical Image Analysis 2023, 87, 102792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, F.; Hu, M.; Zhong, M.E.; Feng, S.; Tian, X.; Meng, X.; yi di li Ni-jia ti, M.; Huang, Z.; Lv, M.; Song, T.; et al. Segmentation only uses sparse annotations: Unified weakly and semi-supervised learning in medical images. Medical Image Analysis 2022, 80, 102515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Zhang, C.; He, X. Shape-Aware Semi-supervised 3D Semantic Segmentation for Medical Images. Lecture Notes in Computer Science (including subseries Lecture Notes in Artificial Intelligence and Lecture Notes in Bioinformatics), 2261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, R.; Chen, S.; Ji, C.; Fan, J.; Li, Y. Boundary-aware context neural network for medical image segmentation. Medical Image Analysis 2022, 78, 102395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, X.; Chen, J.; Song, T.; Wang, G. Semi-supervised Medical Image Segmentation through Dual-task Consistency. Proceedings of the AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence 2021, 35, 8801–8809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- jie Shi, G.; wei Gao, D. Transverse ultimate capacity of U-type stiffened panels for hatch covers used in ship cargo holds. Ships and Offshore Structures 2021, 16, 608–619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, J.; Wang, P.; Desrosiers, C.; Pedersoli, M. Self-Paced Contrastive Learning for Semi-supervised Medical Image Segmentation with Meta-labels. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 2021, 20, 16686–16699. [Google Scholar]

- Gao, S.; Zhang, Z.; Ma, J.; Li, Z.; Zhang, S. Correlation-Aware Mutual Learning for Semi-supervised Medical Image Segmentation. Lecture Notes in Computer Science (including subseries Lecture Notes in Artificial Intelligence and Lecture Notes in Bioinformatics), 4220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oh, S.J.; Benenson, R.; Khoreva, A.; Akata, Z.; Fritz, M.; Schiele, B. Exploiting saliency for object segmentation from image level labels. Proceedings - 30th IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, CVPR 2017, 5038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durieux, G.; Irles, A.; Miralles, V.; Peñuelas, A.; Perelló, M.; Pöschl, R.; Vos, M. The electro-weak couplings of the top and bottom quarks — Global fit and future prospects. Journal of High Energy Physics 2019 2019:12 2019, 2019, 1–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kervadec, H.; Dolz´, J.D.; Montral, D.; Wang, S.; Granger´, E.G.; Montral, G.; Ben, I.; Ayed´, A.; Montral, A. Bounding boxes for weakly supervised segmentation: Global constraints get close to full supervision. Proceedings of Machine Learning Research 2020, 121, 365–380. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, D.; Dai, J.; Jia, J.; He, K.; Sun, J. ScribbleSup: Scribble-Supervised Convolutional Networks for Semantic Segmentation. Proceedings of the IEEE Computer Society Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, 3159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Zhang, J.; Kan, M.; Shan, S.; Chen, X. Self-Supervised Equivariant Attention Mechanism for Weakly Supervised Semantic Segmentation, 2020.

- Dietterich, T.G.; Lathrop, R.H.; Lozano-Pérez, T. Solving the multiple instance problem with axis-parallel rectangles. Artificial Intelligence 1997, 89, 31–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chikontwe, P.; Sung, H.J.; Jeong, J.; Kim, M.; Go, H.; Nam, S.J.; Park, S.H. Weakly supervised segmentation on neural compressed histopathology with self-equivariant regularization. Medical Image Analysis 2022, 80, 102482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patel, G.; Dolz, J. Weakly supervised segmentation with cross-modality equivariant constraints. Medical Image Analysis 2022, 77, 102374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chattopadhay, A.; Sarkar, A.; Howlader, P.; Balasubramanian, V.N. Grad-CAM++: Generalized gradient-based visual explanations for deep convolutional networks. Proceedings - 2018 IEEE Winter Conference on Applications of Computer Vision, WACV 2018. [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Mehta, N.; Demirci, G.; Hu, X.; Ramakrishnan, M.S.; Naguib, M.; Chen, C.; Tsai, C.L. Anomaly-guided weakly supervised lesion segmentation on retinal OCT images. Medical Image Analysis 2024, 94, 103139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Wang, T.; Wu, X.; Hua, X.S.; Zhang, H.; Sun, Q. Class Re-Activation Maps for Weakly-Supervised Semantic Segmentation, 2022.

- Zhang, W.; Zhu, L.; Hallinan, J.; Zhang, S.; Makmur, A.; Cai, Q.; Ooi, B.C. BoostMIS: Boosting Medical Image Semi-Supervised Learning With Adaptive Pseudo Labeling and Informative Active Annotation, 2022.

- Li, K.; Qian, Z.; Han, Y.; Chang, E.I.; Wei, B.; Lai, M.; Liao, J.; Fan, Y.; Xu, Y. Weakly supervised histopathology image segmentation with self-attention. Medical Image Analysis 2023, 86, 102791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, T.; Pan, Y.; Li, Y.; Ngo, C.W.; Mei, T. Wave-ViT: Unifying Wavelet and Transformers for Visual Representation Learning. Lecture Notes in Computer Science (including subseries Lecture Notes in Artificial Intelligence and Lecture Notes in Bioinformatics), 3685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, B.; Parkhi, O.; Kirillov, A. Pointly-Supervised Instance Segmentation, 2022.

- Seeböck, P.; Orlando, J.I.; Michl, M.; Mai, J.; Schmidt-Erfurth, U.; Bogunović, H. Anomaly guided segmentation: Introducing semantic context for lesion segmentation in retinal OCT using weak context supervision from anomaly detection. Medical Image Analysis 2024, 93, 103104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, Y.; Wang, H.; Ji, H.; Liu, H.; Li, Y.; He, N.; Wei, D.; Huang, Y.; Dai, Q.; Wu, J.; et al. A deep weakly semi-supervised framework for endoscopic lesion segmentation. Medical Image Analysis 2023, 90, 102973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahn, J.; Shin, S.Y.; Shim, J.; Kim, Y.H.; Han, S.J.; Choi, E.K.; Oh, S.; Shin, J.Y.; Choe, J.C.; Park, J.S.; et al. Association between epicardial adipose tissue and embolic stroke after catheter ablation of atrial fibrillation. Journal of Cardiovascular Electrophysiology 2019, 30, 2209–2216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Zhang, J.; Kan, M.; Shan, S.; Chen, X. Self-Supervised Equivariant Attention Mechanism for Weakly Supervised Semantic Segmentation. Proceedings of the IEEE Computer Society Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, 1227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viniavskyi, O.; Dobko, M.; Dobosevych, O. Weakly-Supervised Segmentation for Disease Localization in Chest X-Ray Images. Lecture Notes in Computer Science (including subseries Lecture Notes in Artificial Intelligence and Lecture Notes in Bioinformatics), 2299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, X.; Ji, Z.; Niu, S.; Leng, T.; Rubin, D.L.; Chen, Q. MS-CAM: Multi-Scale Class Activation Maps for Weakly-Supervised Segmentation of Geographic Atrophy Lesions in SD-OCT Images. IEEE journal of biomedical and health informatics 2020, 24, 3443–3455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, S.; Zhang, J.; Xia, Y. TransWS: Transformer-Based Weakly Supervised Histology Image Segmentation. Lecture Notes in Computer Science (including subseries Lecture Notes in Artificial Intelligence and Lecture Notes in Bioinformatics), 3583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, T.; Niu, S.; Dong, J.; Chen, Y. Weakly Supervised Retinal Detachment Segmentation Using Deep Feature Propagation Learning in SD-OCT Images. Lecture Notes in Computer Science (including subseries Lecture Notes in Artificial Intelligence and Lecture Notes in Bioinformatics), 2069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva-Rodríguez, J.; Naranjo, V.; Dolz, J. Constrained unsupervised anomaly segmentation. Medical Image Analysis 2022, 80, 102526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pinaya, W.H.; Tudosiu, P.D.; Gray, R.; Rees, G.; Nachev, P.; Ourselin, S.; Cardoso, M.J. Unsupervised brain imaging 3D anomaly detection and segmentation with transformers. Medical Image Analysis 2022, 79, 102475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hinton, G.E.; Salakhutdinov, R.R. Reducing the dimensionality of data with neural networks. Science 2006, 313, 504–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kingma, D.P.; Welling, M. Auto-Encoding Variational Bayes. 2nd International Conference on Learning Representations, ICLR 2014 - Conference Track Proceedings. [CrossRef]

- Schlegl, T.; Seeböck, P.; Waldstein, S.M.; Langs, G.; Schmidt-Erfurth, U. f-AnoGAN: Fast unsupervised anomaly detection with generative adversarial networks. Medical Image Analysis 2019, 54, 30–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stan, S.; Rostami, M. Unsupervised model adaptation for source-free segmentation of medical images. Medical Image Analysis 2024, 95, 103179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Xing, F.; Fakhri, G.E.; Woo, J. Memory consistent unsupervised off-the-shelf model adaptation for source-relaxed medical image segmentation. Medical Image Analysis 2023, 83, 102641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Dai, D.; Xu, S. Rethinking adversarial domain adaptation: Orthogonal decomposition for unsupervised domain adaptation in medical image segmentation. Medical Image Analysis 2022, 82, 102623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, Z.; Xin, J.; You, C.; Shi, P.; Dong, S.; Dvornek, N.C.; Zheng, N.; Duncan, J.S. Style mixup enhanced disentanglement learning for unsupervised domain adaptation in medical image segmentation. Medical Image Analysis 2025, 101, 103440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, B.; Zhang, R.; Diao, S.; Zhu, J.; Yuan, Y.; Cai, J.; Shao, L.; Li, S.; Qin, W. Dual domain distribution disruption with semantics preservation: Unsupervised domain adaptation for medical image segmentation. Medical Image Analysis 2024, 97, 103275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dou, Q.; Ouyang, C.; Chen, C.; Chen, H.; Glocker, B.; Zhuang, X.; Heng, P.A. PnP-AdaNet: Plug-and-Play Adversarial Domain Adaptation Network with a Benchmark at Cross-modality Cardiac Segmentation 2018.

- Vu, T.H.; Jain, H.; Bucher, M.; Cord, M.; Perez, P. ADVENT: Adversarial Entropy Minimization for Domain Adaptation in Semantic Segmentation, 2019.

- Chen, C.; Dou, Q.; Chen, H.; Qin, J.; Heng, P.A. Unsupervised Bidirectional Cross-Modality Adaptation via Deeply Synergistic Image and Feature Alignment for Medical Image Segmentation. IEEE Transactions on Medical Imaging 2020, 39, 2494–2505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, F.; Zhuang, X. CF Distance: A New Domain Discrepancy Metric and Application to Explicit Domain Adaptation for Cross-Modality Cardiac Image Segmentation. IEEE Transactions on Medical Imaging 2020, 39, 4274–4285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Z.; Zhu, Z.; Zheng, S.; Liu, Y.; Zhou, J.; Zhao, Y. Margin Preserving Self-Paced Contrastive Learning Towards Domain Adaptation for Medical Image Segmentation. IEEE Journal of Biomedical and Health Informatics 2022, 26, 638–647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, J.; Huang, W.; Zhang, J.; Debattista, K.; Han, J. Addressing inconsistent labeling with cross image matching for scribble-based medical image segmentation. IEEE Transactions on Image Processing 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, W.; Wan, F.; Pan, X.; Peng, Z.; Tian, Q.; Han, Z.; Zhou, B.; Ye, Q. TS-CAM: Token Semantic Coupled Attention Map for Weakly Supervised Object Localization, 2021.

- Mahapatra, D. Generative Adversarial Networks And Domain Adaptation For Training Data Independent Image Registration 2019.

- Wang, G.; Li, W.; Zuluaga, M.A.; Pratt, R.; Patel, P.A.; Aertsen, M.; Doel, T.; David, A.L.; Deprest, J.; Ourselin, S.; et al. Interactive Medical Image Segmentation Using Deep Learning with Image-Specific Fine Tuning. IEEE Transactions on Medical Imaging 2018, 37, 1562–1573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.; Dou, Q.; Chen, H.; Qin, J.; Heng, P.A. Synergistic Image and Feature Adaptation: Towards Cross-Modality Domain Adaptation for Medical Image Segmentation. Proceedings of the AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence 2019, 33, 865–872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lei, T.; Zhang, D.; Du, X.; Wang, X.; Wan, Y.; Nandi, A.K. Semi-Supervised Medical Image Segmentation Using Adversarial Consistency Learning and Dynamic Convolution Network. IEEE Transactions on Medical Imaging 2023, 42, 1265–1277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalinicheva, E.; Ienco, D.; Sublime, J.; Trocan, M. Unsupervised Change Detection Analysis in Satellite Image Time Series Using Deep Learning Combined with Graph-Based Approaches. IEEE Journal of Selected Topics in Applied Earth Observations and Remote Sensing 2020, 13, 1450–1466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamnitsas, K.; Baumgartner, C.; Ledig, C.; Newcombe, V.; Simpson, J.; Kane, A.; Menon, D.; Nori, A.; Criminisi, A.; Rueckert, D.; et al. Unsupervised Domain Adaptation in Brain Lesion Segmentation with Adversarial Networks. Lecture Notes in Computer Science (including subseries Lecture Notes in Artificial Intelligence and Lecture Notes in Bioinformatics), 0265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoffman, J.; Tzeng, E.; Park, T.; Zhu, J.Y.; Isola, P.; Saenko, K.; Efros, A.; Darrell, T. CyCADA: Cycle-Consistent Adversarial Domain Adaptation, 2018.

- Zhang, Y.; Miao, S.; Mansi, T.; Liao, R. Task driven generative modeling for unsupervised domain adaptation: Application to X-ray image segmentation. Lecture Notes in Computer Science (including subseries Lecture Notes in Artificial Intelligence and Lecture Notes in Bioinformatics), 1071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Dataset | Modality | Anatomical Area | Application Scenarios |

|---|---|---|---|

| ACDC[16] | MRI | Heart (left and right ventricles) | Cardiac function analysis, ventricular segmentation |

| Colorectal adenocarcinoma glands [17] | Pathology Sections (H&E Staining) | Colorectal tissue | Segmentation of the glandular structure |

| IU Chest X-ray [18] | X-ray (chest x-ray) | Chest (cardiopulmonary area) | Classification of lung diseases |

| MIMIC-CXR [19] | X-ray (chest x-ray) + clinical report | Chest | Automatic diagnosis of multiple diseases |

| COV-CTR [20] | CT (chest) | Lung | COVID-19 severity rating |

| MS-CXR-T [21] | X-ray (chest x-ray) | Chest | Multilingual report generation |

| NIH-AAPM-Mayo Clinical LDCT [22] | Low-dose CT (chest) | Lung | Lung nodule detection |

| LoDoPaB [23] | Low-dose CT (Simulation) | Body | CT reconstruction algorithm development |

| LDCT [24] | Low-dose CT | Chest/abdomen | Radiation dose reduction studies |

| LA [25] | MRI | Heart (left atrium) | Surgical planning for atrial fibrillation |

| Pancreas-CT [26] | CT (abdomen) | Pancreas | Pancreatic tumor segmentation |

| BraTS [27] | Multiparametric MRI | Brain (glioma) | Brain tumor segmentation |

| ATLAS [28] | MRI (T1) | Brain (stroke lesions) | Stroke analysis |

| ISLES [29,30,31] | MRI (multiple sequences) | Brain | Ischemic stroke segmentation |

| Dataset | Modality | Anatomical Area | Application Scenarios |

|---|---|---|---|

| AISD [32] | Ultrasonic | Abdominal organs | Organ boundary segmentation |

| Cardiac [33] | MRI | Heart | Ventricular division |

| KiTS19 [34] | CT (abdomen) | Kidney | Segmentation of kidney tumors |

| UKB [35] | MRI/CT/X-ray | Body | Multi-organ phenotypic analysis |

| LiTS [36] | CT (abdomen) | Liver | Segmentation of liver tumors |

| CHAOS [37] | CT/MRI (abdomen) | Multi-organ | Cross-modal organ segmentation |

| Method | % Labeled | 2017 ACDC (2D) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Scans | DSC (%) | Jaccard (%) | 95HD (mm) | ASD (mm) | |

| Using 5% labeled scans | |||||

| UAMT [49] | 5 | 51.23(1.96) | 41.82(1.62) | 17.13(2.82) | 7.76(2.01) |

| SASSNet [59] | 5 | 58.47(1.74) | 47.04(2.02) | 18.04(3.63) | 7.31(1.53) |

| Tri-U-MT [60] | 5 | 59.15(2.01) | 47.37(1.82) | 17.37(2.77) | 7.34(1.31) |

| DTC [61] | 5 | 57.09(1.57) | 45.61(1.23) | 20.63(2.61) | 7.05(1.94) |

| CoraNet [62] | 5 | 59.91(2.08) | 48.37(1.75) | 15.53(2.23) | 5.96(1.42) |

| SPCL [63] | 5 | 81.82(1.24) | 70.62(1.04) | 5.96(1.62) | 2.21(0.29) |

| MC-Net+ [52] | 5 | 63.47(1.75) | 53.13(1.41) | 7.38(1.68) | 2.37(0.32) |

| URPC [50] | 5 | 62.57(1.18) | 52.75(1.36) | 7.79(1.85) | 2.64(0.36) |

| PLCT [57] | 5 | 78.42(1.45) | 67.43(1.25) | 6.54(1.62) | 2.48(0.24) |

| DGCL [41] | 5 | 80.57(1.12) | 68.74(0.96) | 6.04(1.73) | 2.17(0.30) |

| CAML [64] | 5 | 79.04(0.83) | 68.45(0.97) | 6.28(1.79) | 2.24(0.26) |

| DCNet [40] | 5 | 71.57(1.58) | 61.12(1.19) | 8.37(1.92) | 4.08(0.84) |

| SFPC [43] | 5 | 80.52(1.03) | 68.73(0.88) | 6.08(1.47) | 2.14(0.22) |

| Using 10% labeled scans | |||||

| UAMT [49] | 10 | 81.86(1.25) | 71.07(1.43) | 12.92(1.68) | 3.49(0.64) |

| SASSNet [59] | 10 | 84.61(1.97) | 74.53(1.78) | 6.02(1.54) | 1.71(0.35) |

| Tri-U-MT [60] | 10 | 84.06(1.69) | 74.32(1.77) | 7.41(1.63) | 2.59(0.51) |

| DTC [61] | 10 | 82.91(1.65) | 71.61(1.81) | 8.69(1.84) | 3.04(0.59) |

| CoraNet [62] | 10 | 84.56(1.53) | 74.41(1.49) | 6.11(1.15) | 2.35(0.44) |

| SPCL [63] | 10 | 87.57(1.15) | 78.63(0.89) | 4.87(0.79) | 1.31(0.27) |

| MC-Net+ [52] | 10 | 86.78(1.41) | 77.31(1.27) | 6.92(0.95) | 2.04(0.37) |

| URPC [50] | 10 | 85.18(0.98) | 74.65(0.83) | 5.01(0.79) | 1.52(0.26) |

| PLCT [57] | 10 | 86.83(1.17) | 77.04(0.83) | 6.62(0.86) | 2.27(0.42) |

| DGCL [41] | 10 | 87.74(1.06) | 78.82(1.22) | 4.74(0.73) | 1.56(0.24) |

| CAML [64] | 10 | 87.67(0.83) | 78.70(0.91) | 4.97(0.62) | 1.35(0.17) |

| DCNet [40] | 10 | 87.81(0.88) | 78.96(0.94) | 4.84(0.81) | 1.23(0.21) |

| SFPC [43] | 10 | 87.76(0.92) | 78.94(0.83) | 4.90(0.74) | 1.28(0.23) |

| Method | % Labeled | BraTS2020 (3D) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Scans | DSC (%) | Jaccard (%) | 95HD (mm) | ASD (mm) | |

| Using 5% labeled scans | |||||

| UAMT [49] | 5 | 49.46(2.51) | 38.46(1.86) | 19.57(3.28) | 6.54(0.86) |

| SASSNet [59] | 5 | 51.82(1.74) | 43.93(1.42) | 23.47(2.83) | 7.47(1.09) |

| Tri-U-MT [60] | 5 | 53.95(1.97) | 44.33(2.18) | 19.68(3.06) | 7.29(0.84) |

| DTC [61] | 5 | 56.72(2.04) | 45.78(1.67) | 17.38(4.31) | 6.28(1.22) |

| CoraNet [62] | 5 | 57.97(1.83) | 46.40(1.64) | 19.52(2.80) | 5.83(0.85) |

| SPCL [63] | 5 | 78.73(1.54) | 67.90(1.29) | 16.26(1.68) | 4.47(1.08) |

| MC-Net+ [52] | 5 | 58.91(1.47) | 47.24(1.36) | 20.82(3.35) | 7.14(1.12) |

| URPC [50] | 5 | 60.48(2.01) | 50.69(1.99) | 18.21(3.27) | 7.12(0.95) |

| PLCT [57] | 5 | 65.74(2.17) | 55.40(1.85) | 16.61(3.04) | 6.85(1.39) |

| DGCL [41] | 5 | 80.21(0.75) | 68.86(0.63) | 14.91(1.53) | 4.63(1.16) |

| CAML [64] | 5 | 77.86(0.96) | 66.42(1.37) | 15.21(1.74) | 5.10(1.12) |

| DCNet [40] | 5 | 78.52(1.21) | 67.81(1.07) | 17.37(1.48) | 4.32(0.96) |

| SFPC [43] | 5 | 80.76(0.74) | 69.18(0.83) | 14.87(1.92) | 4.02(0.75) |

| Using 10% labeled scans | |||||

| UAMT [49] | 10 | 81.04(1.46) | 68.88(1.57) | 17.27(3.35) | 6.25(1.63) |

| SASSNet [59] | 10 | 82.36(2.08) | 71.03(2.35) | 14.80(3.72) | 4.11(1.54) |

| Tri-U-MT [60] | 10 | 82.83(1.35) | 71.52(1.21) | 15.19(2.86) | 3.57(1.30) |

| DTC [61] | 10 | 81.98(2.41) | 70.41(2.73) | 16.27(3.62) | 3.62(1.71) |

| CoraNet [62] | 10 | 81.38(1.68) | 70.01(1.83) | 13.94(2.72) | 3.95(1.26) |

| SPCL [63] | 10 | 84.65(1.16) | 73.91(1.19) | 12.24(1.47) | 3.28(0.42) |

| MC-Net+ [52] | 10 | 83.93(1.73) | 72.34(1.69) | 13.52(2.74) | 3.37(1.13) |

| URPC [50] | 10 | 84.23(1.41) | 72.37(1.26) | 11.52(1.79) | 3.26(1.14) |

| PLCT [57] | 10 | 83.66(1.82) | 71.99(1.67) | 13.68(1.29) | 3.59(1.02) |

| DGCL [41] | 10 | 84.02(1.24) | 72.16(1.07) | 12.98(1.28) | 3.02(0.96) |

| CAML [64] | 10 | 84.34(1.03) | 73.84(0.92) | 12.02(1.84) | 3.31(0.58) |

| DCNet [40] | 10 | 83.39(0.97) | 71.94(0.88) | 11.93(1.24) | 3.50(0.33) |

| SFPC [43] | 10 | 85.01(0.89) | 74.67(1.14) | 10.73(1.36) | 3.03(0.31) |

| Dataset | RESC | Duke | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lesions | BG | SRF | PED | BG | Fluid | |||||

| Metrics | DSC | mIoU | DSC | mIoU | DSC | mIoU | DSC | mIoU | DSC | mIoU |

| IRNet[82] | 98.88% | 97.78% | 49.18% | 33.75% | 22.98% | 14.66% | 99.02% | 98.10% | 17.79% | 20.45% |

| SEAM[83] | 98.69% | 97.43% | 46.44% | 34.13% | 28.09% | 10.71% | 98.48% | 97.03% | 25.48% | 17.87% |

| ReCAM[75] | 98.81% | 97.66% | 31.19% | 14.23% | 31.99% | 19.11% | 98.16% | 96.41% | 18.91% | 11.67% |

| WSMIS[84] | 96.90% | 95.64% | 45.91% | 24.64% | 10.34% | 2.96% | 98.16% | 96.41% | 0.42% | 0.42% |

| MSCAM[85] | 98.59% | 97.25% | 18.52% | 10.14% | 17.03% | 11.97% | 98.98% | 98.00% | 29.93% | 17.98% |

| TransWS [86] | 99.07% | 98.18% | 52.44% | 34.88% | 30.28% | 17.22% | 99.06% | 98.15% | 37.58% | 27.01% |

| DFP [87] | 98.83% | 97.72% | 20.39% | 6.40% | 31.39% | 15.64% | 99.10% | 98.24% | 27.53% | 15.14% |

| AGM [74] | 99.15% | 98.34% | 57.84% | 43.94% | 34.03% | 22.33% | 99.13% | 98.29% | 40.17% | 30.06% |

| DataSets | Cardiac MRI → Cardiac CT | Cardiac CT → Cardiac MRI | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Methods | AA | AA | ||

| Dice(%) | ASSD(mm) | Dice(%) | ASSD(mm) | |

| Supervised training | ||||

| (Upper bound) | ||||

| Without adaptation | ||||

| (Lower bound) | ||||

| One-shot Finetune | ||||

| Five-shot Finetune | ||||

| PnP-AdaNet [98] | ||||

| AdvEnt [99] | ||||

| SIFA [100] | ||||

| VarDA [101] | ||||

| BMCAN [102] | ||||

| DAAM [75] | ||||

| ADR [95] | ||||

| MPSCL [102] | ||||

| SMEDL [96] | ||||

| Method | Authors (Year) | Key Feature | Application Domain(s) | Strengths |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| AC-MT [47] | Xu et al. (2023) | Ambiguity recognition module selectively calculates consistency loss | Medical image segmentation | High-ambiguity pixels screening with entropy and selective consistency learning improves segmentation index |

| AAU-Net [48] | Adiga V. et al. (2024) | Uncertainty estimation of anatomical prior (DAE) | Abdominal CT multi-organ segmentation | Denoising autoencoder optimizes prediction anatomy rationality and improves DSC/HD |

| CMMT-Net [51] | Li et al. (2024) | Cross-head mutual-aid mean teaching and multi-level perturbations | Medical image segmentation on LA, Pancreas-CT, ACDC | Multi-head decoder enhances prediction diversity and improves Dice |

| MLRPL [54] | Su et al. (2024) | Collaborative learning framework with dual reliability evaluation | Medical image segmentation (e.g., Pancreas-CT) | Dual decoders with mutual comparison strategy achieves near fully-supervised performance |

| CRLN [56] | Wang et al. (2025) | Prototype learning and dynamic interaction correction pseudo-labeling | 3D medical image segmentation (LA, Pancreas-CT, BraTS19) | Multi-prototype learning captures intra-class diversity to enhance generalization |

| CRCFP [45] | Bashir et al. (2024) | Exponential Momentum Context-aware contrast and cross-consistency training | Histopathology image segmentation (BCSS, MoNuSeg) | Dual-path unsupervised learning with lightweight classifier achieves near fully-supervised performance |

| AGM [74] | Yang et al. (2024) | Iterative refinement learning stage | Handling small size, low contrast, and multiple co-existing lesions in medical images | Enhances lesion localization accuracy |

| SA-MIL [77] | Li et al. (2023) | Criss-Cross Attention (CCA) | Better differentiation between foreground (e.g., cancerous regions) and background | Enhances feature representation capability |

| Method | Authors (Year) | Key Feature | Application Domain(s) | Strengths |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SOUSA [58] | Gao et al. (2022) | Multi-angle projection reconstruction loss | More accurate segmentation boundaries, fewer false positive regions | Significantly improves segmentation accuracy |

| Point SEGTR [81] | Shi et al. (2023) | Fuses limited pixel-level annotations with abundant point-level annotations | Endoscopic image analysis | Significantly reduces dependency on pixel-level annotations |

| VAE [88] | Silva-Rodríguez et al. (2022) | Attention mechanism (Grad-CAM) + Extended log-barrier method | Unsupervised Anomaly Detection and Segmentation (UAS); Lesion detection & localization | Effectively separates activation distributions of normal and abnormal patterns |

| OSUDA [94] | Liu et al. (2023) | Exponential Momentum Decay (EMD); Consistency loss on Higher-order BN Statistics (LHBS) | Source-Free Unsupervised Domain Adaptation (SFUDA); Privacy-preserving knowledge transfer | Improves performance and stability in the target domain |

| ODADA [95] | Sun et al. (2022) | Domain-Invariant Representation (DIR) and Domain-Specific Representation (DSR) decomposition | Scenarios with significant domain shift; Unsupervised Domain Adaptation (UDA) | Learns purer and more effective domain-invariant features |

| SMEDL [96] | Cai et al. (2025) | Disentangled Style Mixup (DSM) strategy | Cross-modal medical image segmentation tasks | Leverages both intra-domain and inter-domain variations to learn robust representations |

| DDSP [97] | Zheng et al. (2024) | Dual Domain Distribution Disruption strategy; Inter-channel Feature Alignment (IFA) mechanism | Scenarios with complex domain shift; Unsupervised Domain Adaptation (UDA) tasks | Significantly improves shared classifier accuracy for target domains |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).