Submitted:

03 April 2025

Posted:

07 April 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Experimental Part

2.1. Materials and Instrumentations

2.2. Preparation of Polymer Solutions and Electrospinning Conditions

2.3. Cumulative drug release

2.4. Swelling and Degradation

2.5. Antibacterial and MTT Assays

2.5.1. Antimicrobial

2.5.2. MTT Assay

2.6. Statistical Analysis

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Surface Morphology of Nanofibers

3.2. X-Ray Diffraction Analysis

3.3. Surface Wettability

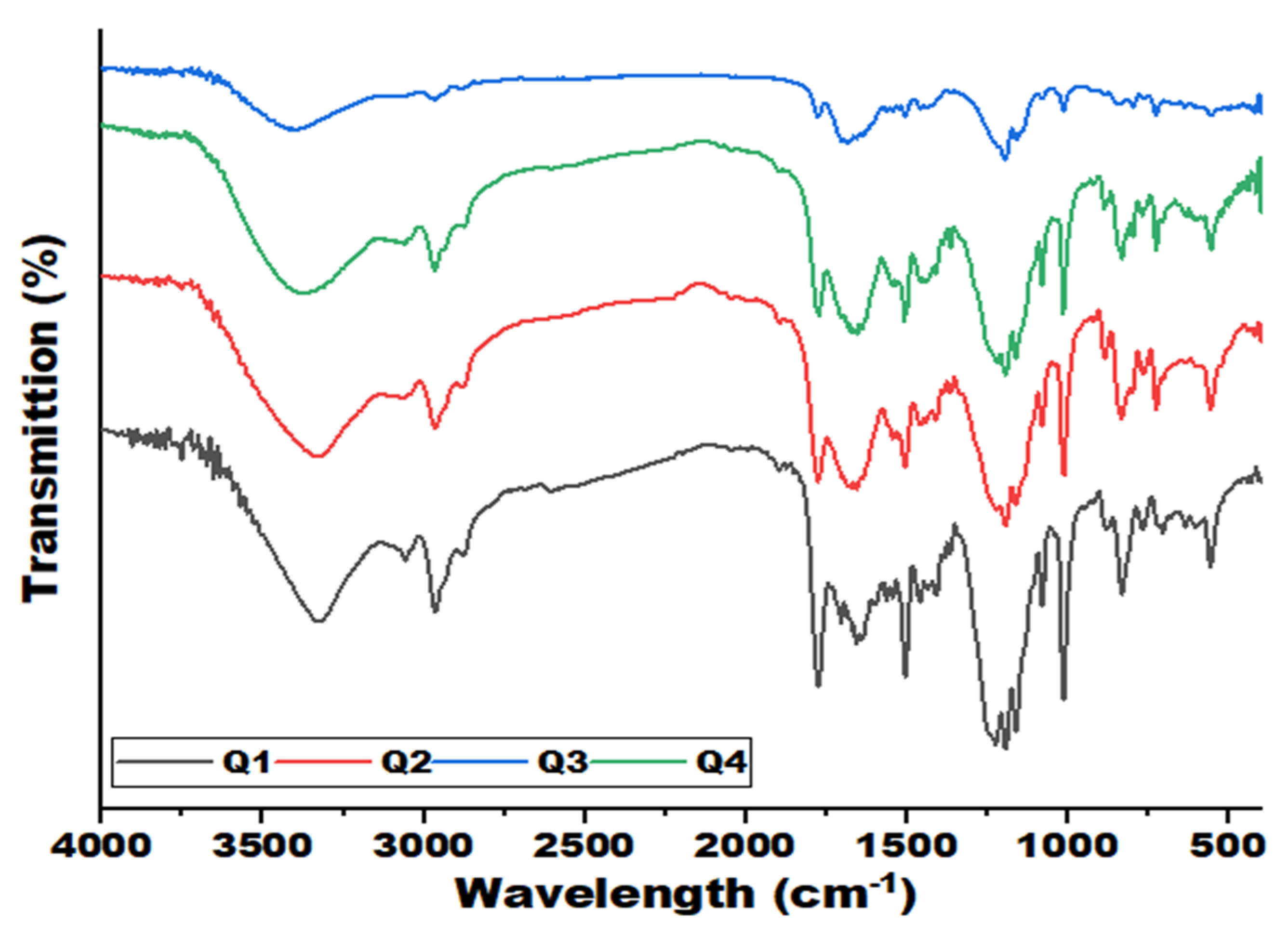

3.4. Fourier Transform Infrared Analysis

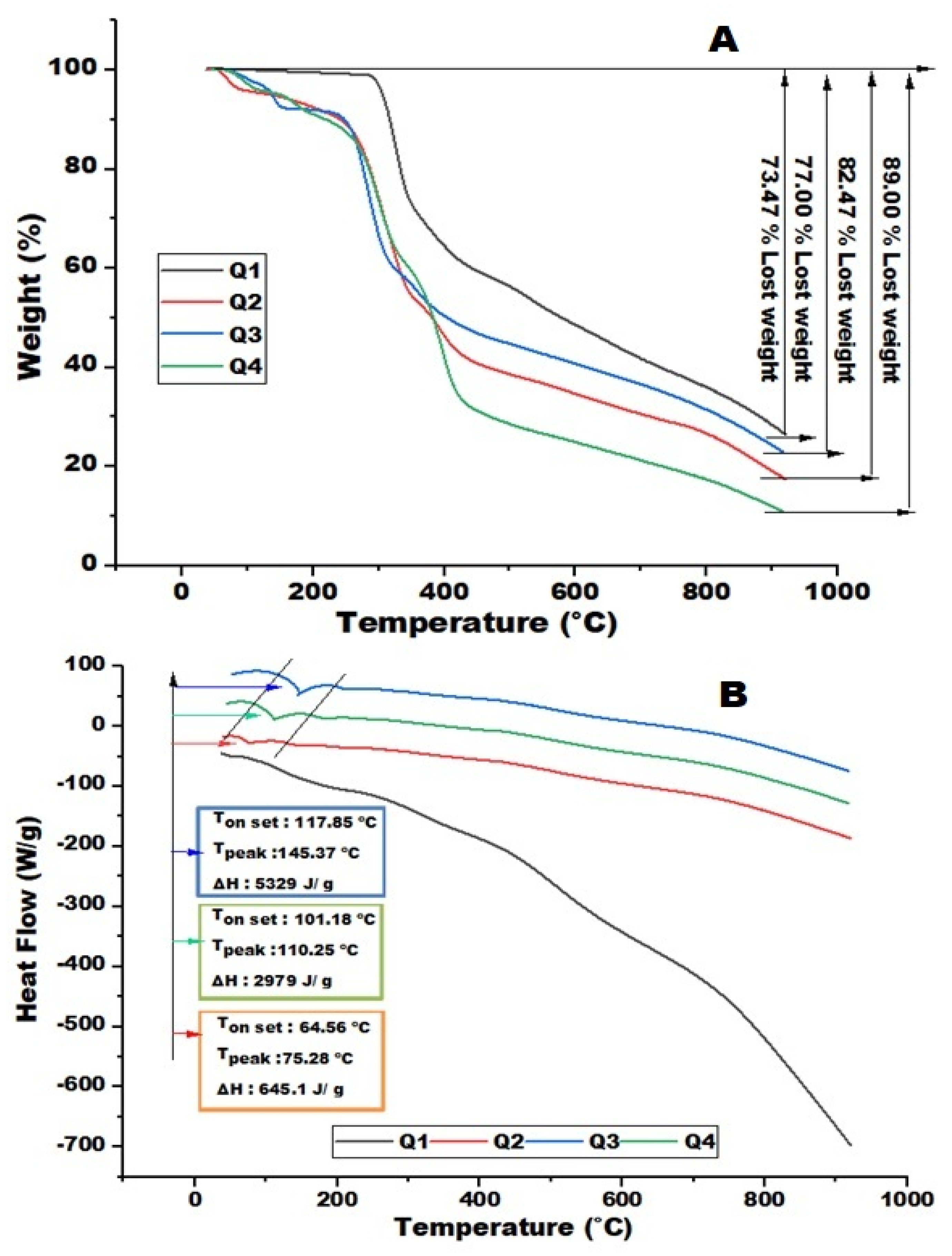

3.5. Thermal Analysis

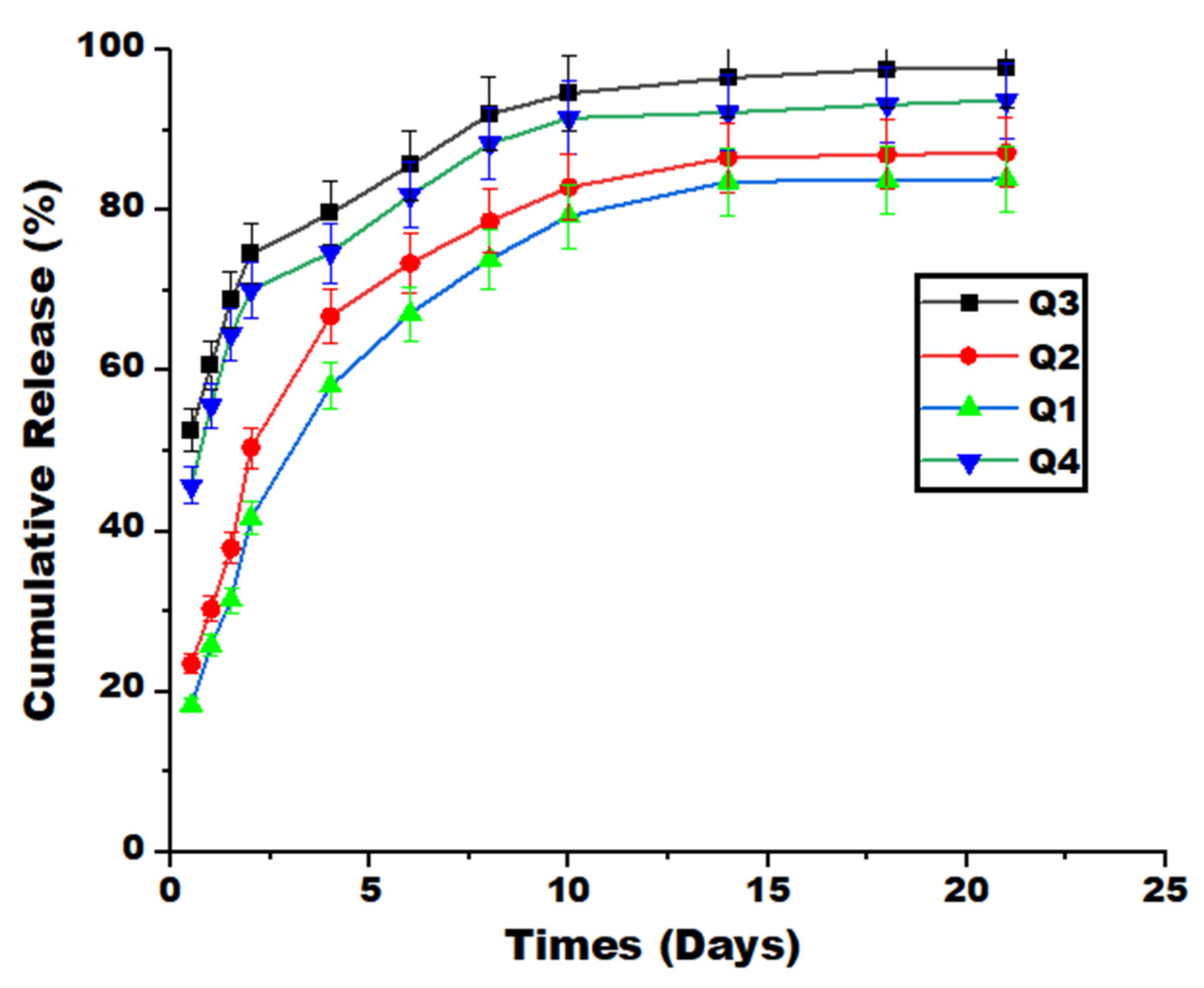

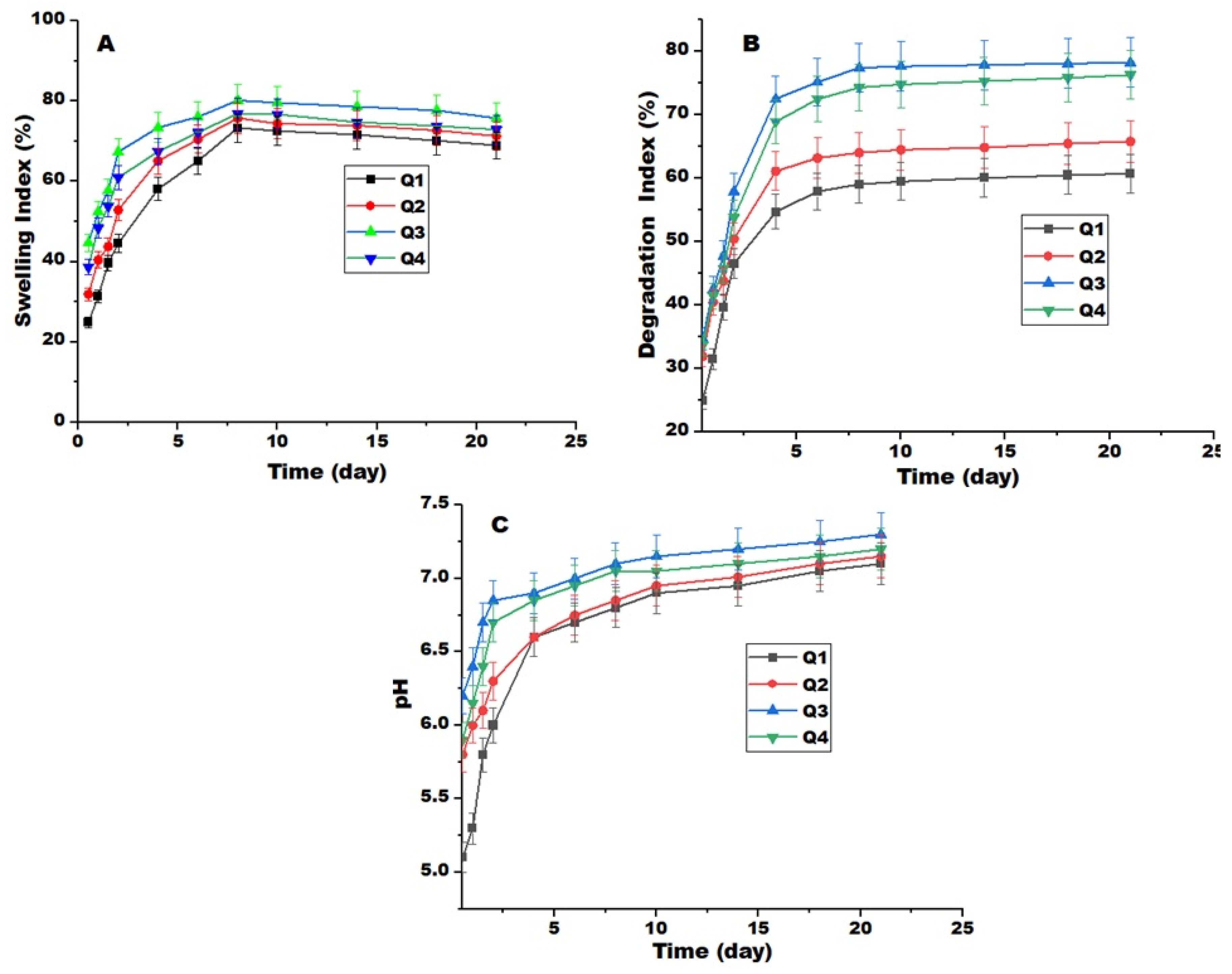

3.6. Release, Swelling, and Degradation Measurements

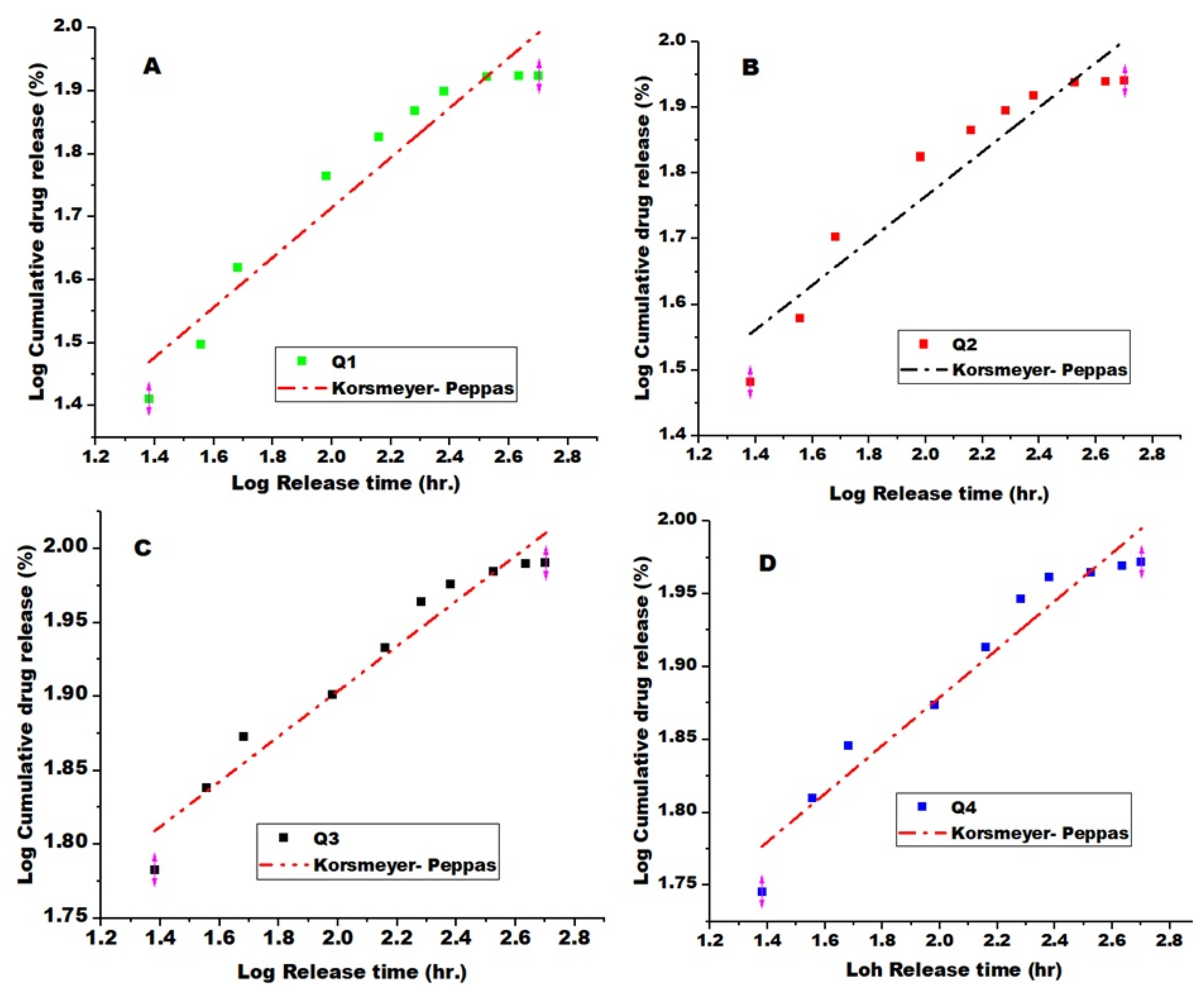

3.7. Drug Release Kinetics Models

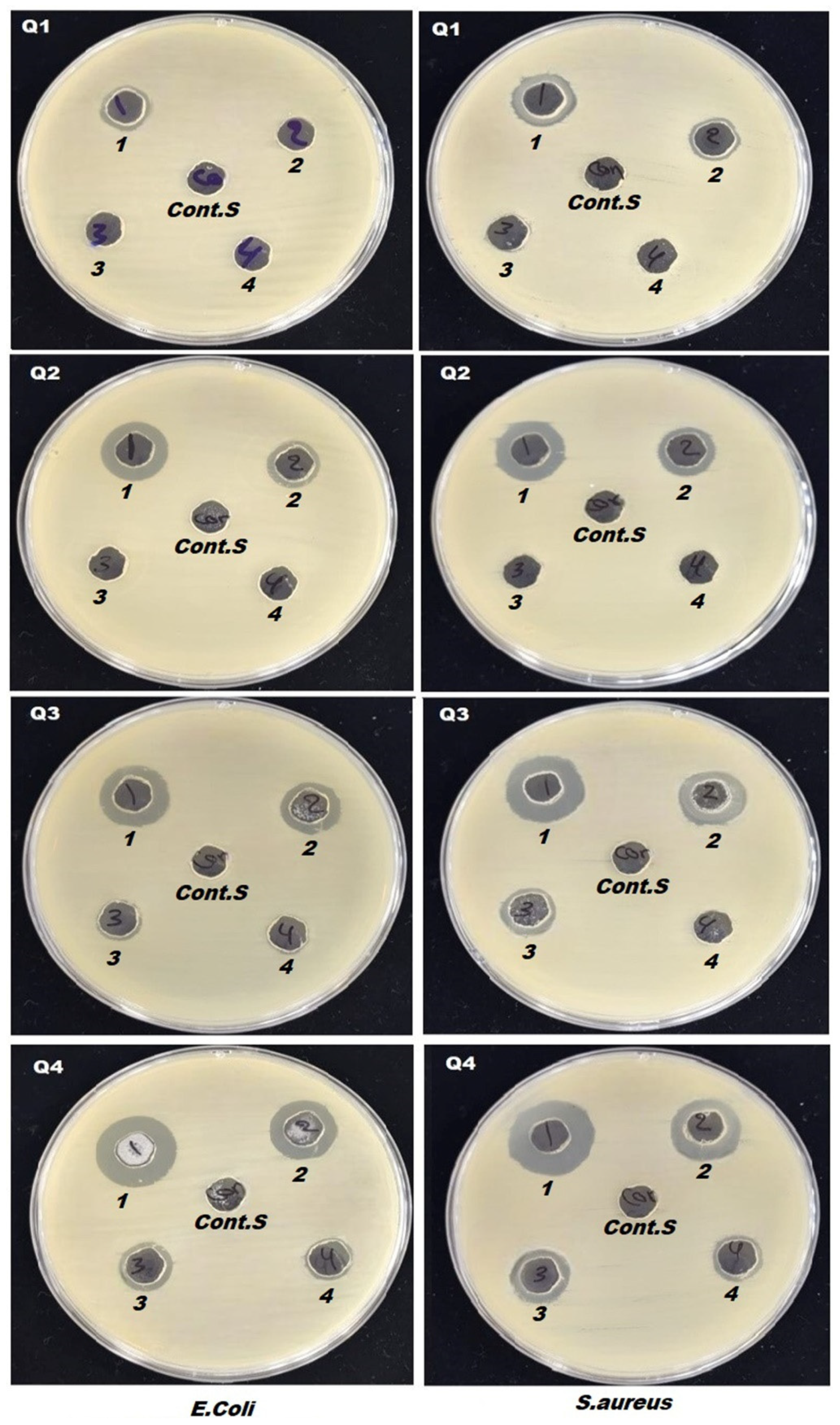

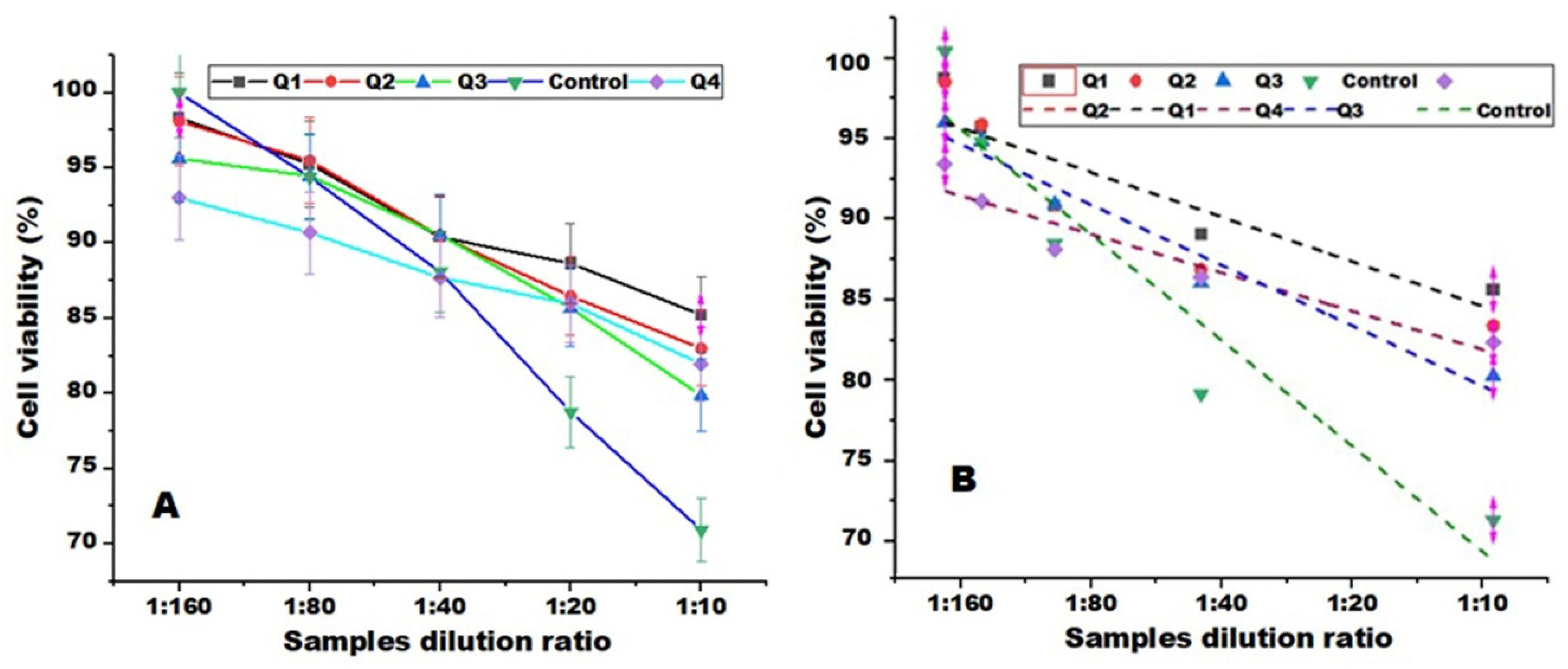

3.8. Antibacterial Activity and MTT Assays Measurements

4. Conclusion

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Tijing, L.; Woo, Y.; Yao, M.; Ren, J.; Shon, H.K. : Electrospinning for membrane fabrication: strategies and applications, Comprehensive Membrane Science and Engineering 1,418-444 (2017).

- Hoque, E.; Nuge, T.; Yeow, T.K.; Nordin, N. : Electrospun matrices from natural polymers for skin regeneration, Nanostructured Polymer Composites for Biomedical Applications 87-104. 2019. [CrossRef]

- Faris, D.; Hadi, N.J.; Habeeb, S.A. Effect of rheological properties of (Poly vinyl alcohol/Dextrin/Naproxen) emulsion on the performance of drug encapsulated nanofibers. Mater. Today: Proc. 2021, 42, 2725–2732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mustfa, W.M.; Habeeb, S.A. Evaluation of the physical properties and filtration efficiency of PVDF/PAN nanofiber membranes by using dry milk protein. Mater. Res. Express 2023, 10, 095306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kajdič, S.; Planinšek, O.; Gašperlin, M.; Kocbek, P. Electrospun nanofibers for customized drug-delivery systems. J. Drug Deliv. Sci. Technol. 2019, 51, 672–681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gouda, M.; Khalaf, M.M.; Shaaban, S.; El-Lateef, H.M.A. Fabrication of Chitosan Nanofibers Containing Some Steroidal Compounds as a Drug Delivery System. Polymers 2022, 14, 2094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alippilakkotte, S.; Kumar, S.; Sreejith, L. Fabrication of PLA/Ag nanofibers by green synthesis method using Momordica charantia fruit extract for wound dressing applications. Colloids Surfaces A: Physicochem. Eng. Asp. 2017, 529, 771–782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pankongadisak, P.; Sangklin, S.; Chuysinuan, P.; Suwantong, O.; Supaphol, P. The use of electrospun curcumin-loaded poly(L-lactic acid) fiber mats as wound dressing materials. J. Drug Deliv. Sci. Technol. 2019, 53, 101121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kusworo, T.D.; Aryanti, N.; Dalanta, F. Effects of incorporating ZnO on characteristic, performance, and antifouling potential of PSf membrane for PRW treatment. IOP Conf. Ser.: Mater. Sci. Eng. 1053, 012134(2021). [CrossRef]

- Liew, W.C.; Muhamad, I.I.; Chew, J.W.; Karim, K.J.A. Synergistic effect of graphene oxide/zinc oxide nanocomposites on polylactic acid-based active packaging film: Properties, release kinetics and antimicrobial efficiency. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2023, 253, 127288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tyler, B.; Gullotti, D.; Mangraviti, A.; Utsuki, T.; Brem, H. Polylactic acid (PLA) controlled delivery carriers for biomedical applications. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 2016, 107, 163–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Potrč, T.; Baumgartner, S.; Roškar, R.; Planinšek, O.; Lavrič, Z.; Kristl, J.; Kocbek, P. Electrospun polycaprolactone nanofibers as a potential oromucosal delivery system for poorly water-soluble drugs. Eur. J. Pharm. Sci. 2015, 75, 101–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, J.; Yang, L.; Liang, Q.; Zhang, X.; Guan, H.; Xu, X.; Chen, X.; Jing, X. Influence of the drug compatibility with polymer solution on the release kinetics of electrospun fiber formulation. J. Control. Release 2005, 105, 43–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, K.; Luu, Y.K.; Chang, C.; Fang, D.; Hsiao, B.S.; Chu, B.; Hadjiargyrou, M. Incorporation and controlled release of a hydrophilic antibiotic using poly(lactide-co-glycolide)-based electrospun nanofibrous scaffolds. J. Control. Release 2004, 98, 47–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tungprapa, S.; Jangchud, I.; Supaphol, P. Release characteristics of four model drugs from drug-loaded electrospun cellulose acetate fiber mats. Polymer 2007, 48, 5030–5041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Habeeb, S.A. , Hussein, A.O. and Ayham, M.H., 2025. Comparative Analysis of the Polyacrylonitrile-Titania and Amidoxime Polyacrylonitrile-Titania Composite Fibers. J. Test. Evaluation. [CrossRef]

- Saniei, H.; Mousavi, S. Surface modification of PLA 3D-printed implants by electrospinning with enhanced bioactivity and cell affinity. Polymer 2020, 196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wardhono, E.Y.; Kanani, N.; Alfirano; Rahmayetty; Alfirano, A. ; Rahmayetti, R. Development of polylactic acid (PLA) bio-composite films reinforced with bacterial cellulose nanocrystals (BCNC) without any surface modification. J. Dispers. Sci. Technol. 2019, 41, 1488–1495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santoro, M.; Shah, S.R.; Walker, J.L.; Mikos, A.G. Poly(lactic acid) nanofibrous scaffolds for tissue engineering. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 2016, 107, 206–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, K.; Wang, C. Recent advances in the use of gelatin in biomedical research. Biotechnol. Lett. 2015, 37, 2139–2145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdulkadhim, M.K.; Habeeb, S.A. The Possibility of Producing Uniform Nanofibers from Blends of Natural Biopolymers. Mater. Perform. Charact. 2022, 11, 313–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mamidi, N.; Delgadillo, R.M.V.; González-Ortiz, A. Engineering of carbon nano-onion bioconjugates for biomedical applications. Mater. Sci. Eng. C 2021, 120, 111698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foox, M.; Zilberman, M. Drug delivery from gelatin-based systems. Expert Opin. Drug Deliv. 2015, 12, 1547–1563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Jbour, N.D.; Beg, M.D.; Gimbun, J.; Alam, A.M. An Overview of Chitosan Nanofibers and their Applications in the Drug Delivery Process. Curr. Drug Deliv. 2019, 16, 272–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conaghan, P.G. A turbulent decade for NSAIDs: update on current concepts of classification, epidemiology, comparative efficacy, and toxicity. Rheumatol. Int. 2011, 32, 1491–1502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roy, S.; Banerjee, R.; Sarkar, M. Direct binding of Cu(II)-complexes of oxicam NSAIDs with DNA backbone. J. Inorg. Biochem. 2006, 100, 1320–1331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knottenbelt, C.; Chambers, G.; Gault, E.; Argyle, D.J. The in vitro effects of piroxicam and meloxicam on canine cell lines. J. Small Anim. Pr. 2006, 47, 14–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pelipenko, J.; Kocbek, P.; Kristl, J. Critical attributes of nanofibers: Preparation, drug loading, and tissue regeneration. Int. J. Pharm. 2015, 484, 57–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jain, K.K. : Drug delivery systems-an overview, Drug delivery systems, 1-50 (2008). [CrossRef]

- Arumugam, M.; Murugesan, B.; Chinnalagu, D.K.; Mahalingam, S. Dual therapeutic approach: Biodegradable nanofiber scaffolds of silk fibroin and collagen combined with silver and gold nanoparticles for enhanced bacterial infections treatment and accelerated wound healing. J. Drug Deliv. Sci. Technol. 2024, 95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Habeeb, S.A.; Abdulkadhim, M.K. Natural Biopolymer–Hydrogel Nanofibers for Antibacterial Applications. J. Eng. Mater. Technol. 2023, 146, 1–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Tang, N.; Cao, L.; Yin, X.; Yu, J.; Ding, B. Highly Integrated Polysulfone/Polyacrylonitrile/Polyamide-6 Air Filter for Multilevel Physical Sieving Airborne Particles. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2016, 8, 29062–29072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Habeeb, S. , Rajabi, L. and Dabirian, F.: Comparing two electrospinning methods in producing polyacrylonitrile nanofibrous tubular structures with enhanced properties, Iran. J. Chem. Chem. Eng 38,23-42(2019).

- Yanilmaz, M.; Lu, Y.; Li, Y.; Zhang, X. SiO2/polyacrylonitrile membranes via centrifugal spinning as a separator for Li-ion batteries. J. Power Sources 2015, 273, 1114–1119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdulkadhim, M.K.; Habeeb, S.A. Electro spun uniform nanofiber from gelatin: Chitosan at low Concentration. Mater. Today: Proc. 2023, 87, 299–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marano, S.; Barker, S.A.; Raimi-Abraham, B.T.; Missaghi, S.; Rajabi-Siahboomi, A.; Craig, D.Q. Development of micro-fibrous solid dispersions of poorly water-soluble drugs in sucrose using temperature-controlled centrifugal spinning. Eur. J. Pharm. Biopharm. 2016, 103, 84–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.; Li, R.; Li, X.; Xie, J. Electrospinning: An enabling nanotechnology platform for drug delivery and regenerative medicine. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 2018, 132, 188–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heikkilä, P.; Harlin, A. Parameter study of electrospinning of polyamide-6. Eur. Polym. J. 2008, 44, 3067–3079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, W.; Yang, F.; Beucken, J.J.v.D.; Bian, Z.; Fan, M.; Chen, Z.; Jansen, J.A. Fibrous scaffolds loaded with protein prepared by blend or coaxial electrospinning. Acta Biomater. 2010, 6, 4199–4207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, X.; Brazel, C.S. On the importance and mechanisms of burst release in matrix-controlled drug delivery systems. J. Control. Release 2001, 73, 121–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akduman, Ç. , Özgüney, I. and Akçakoca Kumbasar, E.P.: Release Characteristics of Naproxen Loaded Electrospun Thermoplastic Polyurethane Nanofibers, XIIIth International Izmir Textile and Apparel Symposium, Antalya, Turkey, 2014. https://hdl.handle.net/11499/51804.

- Bartos, C.; Motzwickler-Németh, A.; Kovács, D.; Burián, K.; Ambrus, R. Study on the Scale-Up Possibility of a Combined Wet Grinding Technique Intended for Oral Administration of Meloxicam Nanosuspension. Pharmaceutics 2024, 16, 1512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, J.; Prabhakaran, M.P.; Tian, L.; Ding, X.; Ramakrishna, S. Drug-loaded emulsion electrospun nanofibers: characterization, drug release and in vitro biocompatibility. RSC Adv. 2015, 5, 100256–100267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmadipour, Z.; Dorraji, M.S.S.; Ashjari, H.R.; Dodangeh, F.; Rasoulifard, M.H. Applying in-situ visible photopolymerization for fabrication of electrospun nanofibrous carrier for meloxicam delivery. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anand, S.; Pandey, P.; Begum, M.Y.; Chidambaram, K.; Arya, D.K.; Gupta, R.K.; Sankhwar, R.; Jaiswal, S.; Thakur, S.; Rajinikanth, P.S. Electrospun Biomimetic Multifunctional Nanofibers Loaded with Ferulic Acid for Enhanced Antimicrobial and Wound-Healing Activities in STZ-Induced Diabetic Rats. Pharmaceuticals 2022, 15, 302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kowalska-Krochmal, B.; Dudek-Wicher, R. The Minimum Inhibitory Concentration of Antibiotics: Methods, Interpretation, Clinical Relevance. Pathogens 2021, 10, 165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, M.Q.; Kharaghani, D.; Nishat, N.; Shahzad, A.; Hussain, T.; Khatri, Z.; Zhu, C.; Kim, I.S. Preparation and characterizations of multifunctional PVA/ZnO nanofibers composite membranes for surgical gown application. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 2019, 8, 1328–1334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-Tobías, H.; Morales, G.; Ledezma, A.; Romero, J.; Grande, D. Novel antibacterial electrospun mats based on poly(d,l-lactide) nanofibers and zinc oxide nanoparticles. J. Mater. Sci. 2014, 49, 8373–8385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adabi, M.; Saber, R.; Naghibzadeh, M.; Faridbod, F.; Faridi-Majidi, R. Parameters affecting carbon nanofiber electrodes for measurement of cathodic current in electrochemical sensors: an investigation using artificial neural network. RSC Adv. 2015, 5, 81243–81252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akduman, C.; Özgüney, I.; Kumbasar, E.P.A. Preparation and characterization of naproxen-loaded electrospun thermoplastic polyurethane nanofibers as a drug delivery system. Mater. Sci. Eng. C 2016, 64, 383–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Golecki, H.M.; Yuan, H.; Glavin, C.; Potter, B.; Badrossamay, M.R.; Goss, J.A.; Phillips, M.D.; Parker, K.K. Effect of Solvent Evaporation on Fiber Morphology in Rotary Jet Spinning. Langmuir 2014, 30, 13369–13374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nadhim, B.A.; Habeeb, S.A. Studying the Physical Properties of Non-Woven Polyacrylonitrile Nanofibers after Adding γ-Fe2O3 Nanoparticles. Egypt. J. Chem. 2021, 64, 7521–7530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karbownik, I.; Rac-Rumijowska, O.; Fiedot-Toboła, M.; Rybicki, T.; Teterycz, H. The Preparation and Characterization of Polyacrylonitrile-Polyaniline (PAN/PANI) Fibers. Materials 2019, 12, 664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Habeeb, S.A.; Rajabi, L.; Dabirian, F. Production of polyacrylonitrile/boehmite nanofibrous composite tubular structures by opposite-charge electrospinning with enhanced properties from a low-concentration polymer solution. Polym. Compos. 2019, 41, 1649–1661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Segal, L.; Creely, J.J.; Martin, A.E., Jr.; Conrad, C.M. An Empirical Method for Estimating the Degree of Crystallinity of Native Cellulose Using the X-Ray Diffractometer. Text. Res. J. 1959, 29, 786–794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Echeverría, C.; Limón, I.; Muñoz-Bonilla, A.; Fernández-García, M.; López, D. Development of Highly Crystalline Polylactic Acid with β-Crystalline Phase from the Induced Alignment of Electrospun Fibers. Polymers 2021, 13, 2860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.; Knowles, J.C.; Kim, H. Porous scaffolds of gelatin–hydroxyapatite nanocomposites obtained by biomimetic approach: Characterization and antibiotic drug release. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. Part B: Appl. Biomater. 2005, 74B, 686–698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karthikeyan, C.; Varaprasad, K.; Akbari-Fakhrabadi, A.; Hameed, A.S.H.; Sadiku, R. Biomolecule chitosan, curcumin and ZnO-based antibacterial nanomaterial, via a one-pot process. Carbohydr. Polym. 2020, 249, 116825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verreck, G.; Chun, I.; Rosenblatt, J.; Peeters, J.; Van Dijck, A.; Mensch, J.; Noppe, M.; Brewster, M.E. Incorporation of drugs in an amorphous state into electrospun nanofibers composed of a water-insoluble, nonbiodegradable polymer. J. Control. Release 2003, 92, 349–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Song, Z.; Chiang, S.W.; Chu, X.; Du, H.; Li, J.; Gan, L.; Xu, C.; Yao, Y.; He, Y.; Li, B.; et al. Effects of solvent on structures and properties of electrospun poly(ethylene oxide) nanofibers. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 2017, 135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurd, F.; Fathi, M.; Shekarchizadeh, H. Basil seed mucilage as a new source for electrospinning: Production and physicochemical characterization. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2017, 95, 689–695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hendrick, E.; Frey, M. Increasing Surface Hydrophilicity in Poly(Lactic Acid) Electrospun Fibers by Addition of Pla-b-Peg Co-Polymers. J. Eng. Fibers Fabr. 2014, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Theerawitayaart, W.; Prodpran, T.; Benjakul, S. Enhancement of Hydrophobicity of Fish Skin Gelatin via Molecular Modification with Oxidized Linoleic Acid. J. Chem. 2019, 2019, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Wachem, P.; Hogt, A.; Beugeling, T.; Feijen, J.; Bantjes, A.; Detmers, J.; van Aken, W. Adhesion of cultured human endothelial cells onto methacrylate polymers with varying surface wettability and charge. Biomaterials 1987, 8, 323–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mosallanezhad, P.; Nazockdast, H.; Ahmadi, Z.; Rostami, A. Fabrication and characterization of polycaprolactone/chitosan nanofibers containing antibacterial agents of curcumin and ZnO nanoparticles for use as wound dressing. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2022, 10, 1027351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Y.; Cai, Q.; Li, Q.; Xue, L.; Jin, R.; Yang, X. Effect of solvent on surface wettability of electrospun polyphosphazene nanofibers. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 2009, 115, 3393–3400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friuli, V.; Pisani, S.; Conti, B.; Bruni, G.; Maggi, L. Tablet Formulations of Polymeric Electrospun Fibers for the Controlled Release of Drugs with pH-Dependent Solubility. Polymers 2022, 14, 2127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chieng, B.W.; Ibrahim, N.A.B.; Yunus, W.M.Z.W.; Hussein, M.Z. Poly(lactic acid)/Poly(ethylene glycol) Polymer Nanocomposites: Effects of Graphene Nanoplatelets. Polymers 2013, 6, 93–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaspar-Pintiliescu, A.; Stefan, L.M.; Anton, E.D.; Berger, D.; Matei, C.; Negreanu-Pirjol, T.; Moldovan, L. Physicochemical and Biological Properties of Gelatin Extracted from Marine Snail Rapana venosa. Mar. Drugs 2019, 17, 589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmadipour, Z.; Dorraji, M.S.S.; Ashjari, H.R.; Dodangeh, F.; Rasoulifard, M.H. Applying in-situ visible photopolymerization for fabrication of electrospun nanofibrous carrier for meloxicam delivery. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salaris, V.; García-Obregón, I.S.F.; López, D.; Peponi, L. Fabrication of PLA-Based Electrospun Nanofibers Reinforced with ZnO Nanoparticles and In Vitro Degradation Study. Nanomaterials 2023, 13, 2236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chao, S.; Zhang, Y.; Cheng, S.; Shao, X.; Liu, S.; Lu, W.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, P.; Yao, Q. Ibuprofen-Loaded ZnO Nanoparticle/Polyacrylonitrile Nanofibers for Dual-Stimulus Sustained Release of Drugs. ACS Appl. Nano Mater. 2023, 6, 5535–5544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chao, S.; Zhang, Y.; Cheng, S.; Shao, X.; Liu, S.; Lu, W.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, P.; Yao, Q. Ibuprofen-Loaded ZnO Nanoparticle/Polyacrylonitrile Nanofibers for Dual-Stimulus Sustained Release of Drugs. ACS Appl. Nano Mater. 2023, 6, 5535–5544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Kang, H.; Che, N.; Liu, Z.; Li, P.; Li, W.; Zhang, C.; Cao, C.; Liu, R.; Huang, Y. Controlled release of liposome-encapsulated Naproxen from core-sheath electrospun nanofibers. Carbohydr. Polym. 2014, 111, 18–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tungprapa, S.; Jangchud, I.; Supaphol, P. Release characteristics of four model drugs from drug-loaded electrospun cellulose acetate fiber mats. Polymer 2007, 48, 5030–5041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basavaraju, K.C.; Jayaraju, J.; Rai, S.K.; Damappa, T. Miscibility studies of xanthan gum with gelatin in dilute solution. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 2008, 109, 2491–2495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prakash, J.; Venkataprasanna, K.; Bharath, G.; Banat, F.; Niranjan, R.; Venkatasubbu, G.D. In-vitro evaluation of electrospun cellulose acetate nanofiber containing Graphene oxide/TiO2/Curcumin for wound healing application. Colloids Surfaces A: Physicochem. Eng. Asp. 2021, 627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niranjan, R.; Kaushik, M.; Selvi, R.T.; Prakash, J.; Venkataprasanna, K.; Prema, D.; Pannerselvam, B.; Venkatasubbu, G.D. PVA/SA/TiO2-CUR patch for enhanced wound healing application: In vitro and in vivo analysis. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2019, 138, 704–717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edikresnha, D.; Suciati, T.; Munir, M.M.; Khairurrijal, K. Polyvinylpyrrolidone/cellulose acetate electrospun composite nanofibres loaded by glycerine and garlic extract within vitroantibacterial activity and release behaviour test. RSC Adv. 2019, 9, 26351–26363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salaris, V.; García-Obregón, I.S.F.; López, D.; Peponi, L. Fabrication of PLA-Based Electrospun Nanofibers Reinforced with ZnO Nanoparticles and In Vitro Degradation Study. Nanomaterials 2023, 13, 2236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poznanski, J.; Szczesny, P.; Ruszczyńska, K.; Zielenkiewicz, P.; Paczek, L. Proteins contribute insignificantly to the intrinsic buffering capacity of yeast cytoplasm. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2013, 430, 741–744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, M.; Guo, H.; Dai, Z.; Yan, X.; Ning, X. Advances in flexible and wearable pH sensors for wound healing monitoring. J. Semicond. 2019, 40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armedya, T.P.; Dzikri, M.F.; Sakti, S.C.W.; Abdulloh, A.; Raharjo, Y.; Wafiroh, S.; Purwati; Fahmi, M. Z. Kinetical Release Study of Copper Ferrite Nanoparticle Incorporated on PCL/Collagen Nanofiber for Naproxen Delivery. BioNanoScience 2019, 9, 274–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Irani, M.; Sadeghi, G.M.M.; Haririan, I. The sustained delivery of temozolomide from electrospun PCL-Diol-b-PU/gold nanocompsite nanofibers to treat glioblastoma tumors. Mater. Sci. Eng. C 2017, 75, 165–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Irani, M.; Sadeghi, G.M.M.; Haririan, I. The sustained delivery of temozolomide from electrospun PCL-Diol-b-PU/gold nanocompsite nanofibers to treat glioblastoma tumors. Mater. Sci. Eng. C 2017, 75, 165–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jahromi, L.P.; Ghazali, M.; Ashrafi, H.; Azadi, A. A comparison of models for the analysis of the kinetics of drug release from PLGA-based nanoparticles. Heliyon 2020, 6, e03451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azadi, A.; Rouini, M.-R.; Hamidi, M. Neuropharmacokinetic evaluation of methotrexate-loaded chitosan nanogels. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2015, 79, 326–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaikh, H. K. , Kshirsagar, R. V., Patil, S. G. : Mathematical models for drug release characterization: a review, World J Pharm Pharm Sci 4, 324-338 (2015).

- Azhar, F.F.; Shahbazpour, E.; Olad, A. pH sensitive and controlled release system based on cellulose nanofibers-poly vinyl alcohol hydrogels for cisplatin delivery. Fibers Polym. 2017, 18, 416–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwak, H.W.; Kim, J.E.; Lee, K.H. Green fabrication of antibacterial gelatin fiber for biomedical application. React. Funct. Polym. 2019, 136, 86–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colon, G.; Ward, B.C.; Webster, T.J. Increased osteoblast and decreased Staphylococcus epidermidis functions on nanophase ZnO and TiO2. J BIOMED MATER RES A: An Official Journal of The Society for Biomaterials, The Japanese Society for Biomaterials, and The Australian Society for Biomaterials and the Korean Society for Biomaterials 2006, 78A, 595–604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Habeeb, S.A. , Abdulkadhim, T.A.: Effect of the Tires Crumb Rubber Loading Levels on NR/SBR Compounding Properties for Antibacterial Applications, Iran. J. Chem. Chem. Eng 42, 4153-4166 (2023). [CrossRef]

- Habeeb, S.A.; Nadhim, B.A. Removal of Nickel (II) Ions, Low Level Pollutants, and Total Bacterial Colony Count from Wastewater by Composite Nanofibers Film. Sci. Iran. 2022, 30, 2056–2069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Padmavathy, N.; Vijayaraghavan, R. Enhanced bioactivity of ZnO nanoparticles—an antimicrobial study. Sci. Technol. Adv. Mater. 2008, 9, 035004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Webster, T.J.; Seil, I.; Seil, J.T. Antimicrobial applications of nanotechnology: methods and literature. Int. J. Nanomed. 2012, 7, 2767–2781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cannella, V.; Altomare, R.; Chiaramonte, G.; Di Bella, S.; Mira, F.; Russotto, L.; Pisano, P.; Guercio, A. Cytotoxicity Evaluation of Endodontic Pins on L929 Cell Line. BioMed Res. Int. 2019, 2019, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srikanth, M.; Khan, W.S.; Asmatulu, R.; Misak, H.E.; Yang, S.-Y.; Asmatulu, E. In vitro Cytotoxicity Studies of Industrially Used Common Nanomaterials on L929 and 3T3 Fibroblast Cells. J. Biomed. Res. Environ. Sci. 2020, 1, 192–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eisenbrand, G.; Pool-Zobel, B.; Baker, V.; Balls, M.; Blaauboer, B.; Boobis, A.; Carere, A.; Kevekordes, S.; Lhuguenot, J.-C.; Pieters, R.; et al. Methods of in vitro toxicology. 40. [CrossRef]

- Berrouet, C.; Dorilas, N.; Rejniak, K.A.; Tuncer, N. Comparison of Drug Inhibitory Effects [Formula: see text) in Monolayer and Spheroid Cultures. Bull. Math. Biol. 2020, 82, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Samples | Nanofiber diameters (nm) | Range of diameters (nm) |

| PLA: GA | 182±77 | 76-315 |

| PLA: GA: ZnO | 352±245 | 81-1199 |

| PLA: GA: ZnO: 0.1wt. % NAP. | 556±427 | 86-1580 |

| PLA: GA: ZnO: 0.2wt. % NAP. | 566±437 | 122-1766 |

| PLA: GA: ZnO: 0.3wt. % NAP. | 1298±723 | 453-2951 |

| PLA: GA: ZnO: 0.1wt. % MEL. | 327±163 | 86-701 |

| PLA: GA: ZnO: 0.2wt. % MEL. | 312±156 | 81-695 |

| PLA: GA: ZnO: 0.3wt. % MEL. | 333±209 | 134-1193 |

| Sample # | Peak position 2θ (°) |

d-spacing [Å] |

FWHM [°2Th.] |

Degree of crystallinity [%] |

Crystallite Size [Å] | Structural Observation |

| Q1 | 23.17 | 3.84 | 7.42 | 23.26 | 11 | Semi-crystalline PLA with gelatin added |

| Q2 | 22.39 | 3.97 | 5.44 | 17.54 | 15 | Effect of ZnO addition observed |

| Q3 | 23.18 | 4.25 | 9.38 | 30.92 | 9 | Naproxen loaded; more amorphous |

| Q4 | 22.89 | 3.88 | 9.24 | 28.44 | 9 | Meloxicam loaded; more amorphous |

| Samples | Zero Order | First Order | Higuchi | Korsmeyer- Peppas | P-values | |||||

|

K0 (hr-1) |

R2 |

K1 (hr-1) |

R2 |

KH (hr -0.5) |

R2 | n | KPP | R2 | ||

| Q1 | 0.127 | 0.754 | 0.0035 | 0.871 | 0.12 | 0.900 | 0.395 | 1.470 | 0.934 | 0.003 |

| Q2 | 0.119 | 0.712 | 0.0038 | 0.860 | 0.129 | 0.870 | 0.340 | 1.555 | 0.910 | 0.01 |

| Q3 | 0.0794 | 0.734 | 0.0065 | 0.953 | 0.661 | 0.882 | 0. 153 | 1.783 | 0.960 | 0.046 |

| Q4 | 0.082 | 0.720 | 0.0043 | 0.880 | 0.162 | 0.863 | 0.165 | 1.776 | 0.95 | 0.048 |

| Samples | Dilute concentrations |

MIC (mg/L) |

Inhibition zoon (mm) for (S. aureus) | Inhibition zoon (mm) for (E. coli) |

| Control sample | - | 0 | 0 | |

| Q1 | Stuck concentration | MIC1000 (1000) | 11±2.21 | 13±2.5 |

| 50% | MIC 50 (500) | 0 | 11±2.3 | |

| 25% | MIC 25 (250) | 0 | 0 | |

| 12.5% | MIC 12.5 (125) | 0 | 0 | |

| Q2 | Stuck concentration | MIC1000 (1000) | 15±2.9 | 16±3.2 |

| 50% | MIC 50 (500) | 12±2.4 | 13±2.6 | |

| 25% | MIC 25 (250) | 0 | 0 | |

| 12.5% | MIC 12.5 (125) | 0 | 0 | |

| Q3 | Stuck concentration | MIC1000 (1000) | 16±3.1 | 17±3.7 |

| 50% | MIC 50 (500) | 14±2.8 | 15±3.1 | |

| 25% | MIC 25 (250) | 10±1.8 | 12±2.2 | |

| 12.5% | MIC 12.5 (125) | 0 | 0 | |

| Q4 | Stuck concentration | MIC1000 (1000) | 17±3.6 | 18±3.4 |

| 50% | MIC 50 (500) | 13±2.6 | 15±2.9 | |

| 25% | MIC 25 (250) | 11±2.2 | 12±2.4 | |

| 12.5% | MIC 12.5 (125) | 0 | 0 |

| Dilution rates | Samples | ||||

| Q1 | Q2 | Q3 | Q4 | Control | |

| Mean ± SD | Mean ± SD | Mean ± SD | Mean ± SD | Mean ± SD | |

| 1:160 | 451 ± 11 | 450 ± 18 | 438± 11 | 426± 10 | 461 ± 5 |

| 1:80 | 437 ± 5 | 438 ± 9 | 433 ± 11 | 416± 5 | 433 ± 10 |

| 1:40 | 414 ± 6 | 415 ± 6 | 415 ± 6 | 402± 5 | 404 ± 6 |

| 1:20 | 406 ± 10 | 396 ± 7 | 393 ± 5 | 394± 8 | 36 1± 13 |

| 1:10 | 391 ± 9 | 380 ± 6 | 366 ± 12 | 376± 11 | 325 ± 5 |

| R2 | 0.984 | 0.993 | 0.96 | 0.987 | 0.990 |

| IC 50 | 15.68 | 13.365 | 12.723 | 17.111 | 7.934 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).