Submitted:

06 April 2025

Posted:

08 April 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Overview of Classical Hardware Metrics

2.1. Commonly Used Hardware Performance Metrics

- CPU Utilization: Measures the percentage of processing power used at a given time, indicating workload efficiency and potential bottlenecks [27].

- Memory Usage: Tracks the amount of RAM occupied by running processes, affecting system responsiveness and multitasking capabilities [2].

- Disk I/O (Input/Output): Evaluates the read and write speeds of storage devices, influencing application load times and data retrieval performance [28].

- Network Throughput: Determines data transfer rates over a network, crucial for cloud computing, real-time streaming, and distributed systems [29].

- Temperature and Power Consumption: Helps assess system cooling efficiency and energy usage, essential for sustainable computing and high-performance workloads [30].

- GPU Load: Measures graphical processing unit (GPU) utilization, significant for gaming, artificial intelligence (AI), and high-performance computing [31].

2.2. Measurement Techniques and Tools

- Profiling Tools: These include Intel VTune for CPU performance analysis, NVIDIA Nsight for GPU workload profiling, and Perf for Linux-based performance monitoring [2].

- Benchmarking Software: Applications like SPEC CPU, Geekbench, and PassMark provide standardized performance tests for comparative hardware evaluation [32].

- Real-time Monitoring Utilities: Built-in system tools such as Windows Task Manager, Linux top and htop, and macOS Activity Monitor help track system resource usage dynamically [33].

3. Overview of Classical Software Metrics

3.1. Functional size measurement

4. Literature Review On Quantum Metrics and Measurements 2

4.1. Quantum Hardware Metrics

- Quantum Volume (QV) [2,40] is a measure that focuses on low-level, hardware-related aspects of quantum devices. QV is used to benchmark noisy intermediate-scale quantum devices (NISQ) by taking into account all relevant hardware parameters: performance and design parameters. It also includes the software behind circuit optimizations and is architecture-independent, that is, it can be used on any system that can run quantum circuits. It quantifies the largest square quantum circuit—where the number of qubits in the circuit equals the number of gate layers—that a device can successfully implement with high fidelity. To determine a device’s quantum volume, randomized square circuits of increasing size are generated, where each layer consists of a random permutation of qubit pairs followed by the application of random two-qubit gates. These circuits are compiled according to the hardware’s constraints and executed repeatedly to evaluate the heavy output probability, which is the likelihood of measuring outcomes that occur more frequently than the median output in the ideal distribution. A circuit size is considered successfully implemented if this probability exceeds on average. The quantum volume is then defined as where n is the largest square circuit that meets this criterion. It is intended to be a practical way of measuring progress towards improved gate error rates in near-term quantum computing.

- Another recent hardware benchmark is the Circuit Layer Operations per Second (CLOPS) [2], which is more concerned with the performance of a Quantum Processing Unit (QPU). Wack et al. [2] identified three key attributes for quantum computing performance: quality, scale, and speed. Quality is the size of a quantum circuit that can be faithfully executed and is measured by the mentioned QV metric. Scale is measured by the number of qubits in the system. And for the Speed attribute, measuring CLOPS is introduced. The CLOPS measure is a derived one and is calculated as the ratio of the total number of QV layers executed to the total execution time. In general, the CLOPS benchmark is a speed benchmark that is designed to allow the system to leverage all quantum resources on a device to run a collection of circuits as fast as possible.

- Qpack Scores, presented by Donkers et al., 2022 [41], is another benchmark that aims to be application-oriented and cross-platform for quantum computers and simulators. It provides a quantitative insight into how well Noisy Intermediate Scale Quantum (NISQ) systems can perform. In particular, systems that make use of scalable Quantum Approximate Optimization Algorithm (QAOA) and Variational Quantum Eigensolver (VQE) applications. QPack scores comprise different sub-scores. The need for sub-scores arose from the fact that some quantum computers may be fast but inaccurate, while other systems are accurate but have longer execution times, which led to the realization that quantum systems cannot be benchmarked solely on a single factor. Qpack combines the following 4 sub-scores to form the overall sub-score. Runtime, Accuracy, Scalability, and Capacity. Runtime calculates the average execution time of quantum circuits on quantum computers. The Accuracy sub-score measures how close the actual outcome of an execution compares to an ideal quantum computer simulator. Scalability provides insight into how well the quantum computer can handle an increase in circuit sizes. Finally, the Capacity score indicates how usable the qubits in a quantum computer are compared to the actual number of qubits provided. These Benchmarks are run on different quantum computers using the cross-platform library LibKet which allows for the collection of quantum execution data to be used as a performance indicator.

- Other research, [42] attempts to quantify environmentally induced decoherence in quantum systems, which is another important factor affecting the amount of error in quantum measurements. In particular, Fedichkin et al. [42] tackled the problem from a physics and a mathematical point of view, exploiting approaches based on the asymptotic relaxation time scales and fidelity measures of decoherence, ultimately formulating an approach to measure the deviation of the actual density matrix, from the ideal one describing the system without considering environmental interactions.

- In "A Functional Architecture for Scalable Quantum Computing" Sete et al. 2016, [43] presented a functional architecture for superconducting quantum computing systems as well as introduced the total quantum factor (TQF) as a performance metric for a quantum processor. To calculate TQF, the average coherence time of all qubits on the chip is divided by the longest gate time in the qubits universal set and is then multiplied by the number of qubits. TQF gives rough estimates of the size of the quantum circuit that can be run before the processor’s performance decoheres.

4.2. Quantum Software Metrics

- Jianjun Zhao, in "Some Size and Structure Metrics for Quantum Software" [19], proposed some extensions of classical software metrics into quantum software metrics. Zhao first considered some Basic Size metrics. These metrics include Code Size, Design Size, and Specification Size. An example of Code Size metrics include Lines of Code (LOC), which is the most commonly used metric of source code program length. Secondly, for Design Size metrics, Zhao proposed the usage of quantum architectural description language (qADL) as an extension to classical architectural description language (ADL) to formally specify the architectures of a quantum software system. For the Specification Size metric, Zhao referred to Quantum Unified Modeling Language (Q-UML) as an extension to the general purpose, well-known Unified Modeling Language (UML). Basic Structure metrics were also considered. Examples include McCabe’s Complexity Metric, as well as Henry and Kafura’s information flow Metric.

- Finžgar et al.,[44] introduced QUARK. The QUARK framework aims to facilitate the development of application-level benchmarks. Written in Python, it aims to be modular and extensible. The architecture of the framework comprises 5 components. Benchmark Manager, which orchestrates the execution of the benchmark. Application, which defines the workload, validation, and evaluation function. Mapping translates the application data and problem specification into a mathematical formulation that is suitable for a solver. The solver is responsible for finding feasible and high-quality solutions to the proposed problem. And Device, which is the quantum device the problem would be run on. After executing the benchmarks, QUARK collects the generated data and executes the validation and evaluation functions. In general, it tries to ensure the reproducibility and verifiability of solutions by automating and standardizing benchmarking systems’ critical parts.

- In their endeavor to enhance the comprehensibility and accessibility of quantum circuits, J. A. Cruz-Lemus et al. [45] introduce a set of metrics that are categorized into distinct classes. The initial classification concerns circuit size, delineating circuit width as the number of qubits and circuit depth as the maximal count of operations on a qubit. Subsequently, the concept of circuit density is introduced, quantified by the number of gates applied at a specific step to each qubit, with metrics encompassing maximum density and average density. Further classifications pertain to the number of gates within the circuit, commencing with single-qubit gates. Within this domain, metrics are proposed to enumerate the quantity of Pauli X, Y, and Z gates individually, alongside their collective count, the quantity of Hadamard gates, the proportion of qubits initially subject to said gates, the count of other gates, and the aggregate count of single-qubit gates. Moving forward, the authors introduce metrics to calculate the average, maximal quantity, and ratio of CNOT and TOFFOLI gates applied to qubits, in addition to their collective counts, as of multi-qubit gates. Aggregate metrics are composed of the total count of gates, the total count of controlled gates, and the ratio of single gates to total gates. Furthermore, oracles and controlled oracles are addressed, wherein their counts, averages, and maximal depths are identified, along with the ratio of qubits influenced by them. Lastly, measurements are addressed, highlighting the quantity and proportion of qubits measured, alongside the percentage of ancilla qubits utilized. The authors emphasize the need for validating this set of metrics to ascertain their comprehensiveness. Notably, the authors refrain from providing explicit elucidation on how these metrics may enhance the understandability of quantum circuits.

- Martiel et al.[46] introduces the Atos Q-score, a benchmark designed to evaluate the performance of quantum processing units (QPUs) in solving combinatorial optimization problems. The Q-score is application-centric, hardware-agnostic, and scalable, providing a measure of a processor’s effectiveness in solving the MaxCut problem using a quantum approximate optimization algorithm (QAOA). The objective of the MaxCut problem is to identify a subset S of the vertex set of a graph in a way that maximizes the count of edges connecting S with its complement. The authors assess the Q-score, which involves running the QAOA for a MaxCut instance and evaluating its performance in both noisy and noise-free systems. They later mention that the Q-score can be used to assess the effectiveness of the software stack. Additionally, the authors discuss the scalability of the Q-score and its potential applications for tracking QPU performance as the number of qubits and problem sizes increases. Furthermore, they introduce an open-source Python package, for computing the Q-score, offering a useful resource for researchers and developers to measure the Q-score of any QPUs integrated with the library.

- Ghoniem et al. [47] aimed at measuring the performance of a quantum processor based on the number of quantum gates required for various quantum algorithms. Experimental evaluations were conducted on nine IBM back-end Quantum Computers, employing four different algorithms: a 5-Qubit entangled circuit algorithm, a 5-Qubit implementation of Grover’s quantum search algorithm, a 5-Qubit implementation of Simon’s quantum algorithm, and the 7-Qubit implementation of Steane’s error correction quantum algorithm. Additionally, quantitative data on the number of quantum gates after the transpilation process using the default and maximum optimization settings were collected. This facilitated the analysis of how the availability and compatibility of different gate sets impact the total number of quantum gates needed for executing the various quantum algorithms. The default optimization level led to fewer gates in all algorithms except Simon’s. Four of the nine backends exhibited a decrease in the number of gates when using the maximum level compared to the default optimization level.

- QUANTIFY [48] is an open-source framework for the quantitative analysis of quantum circuits based on Google’s own Cirq framework. QUANTIFY includes as part of its key features, analysis and optimization methods, semi-automatic quantum circuit rewriting, and others. The architecture of QUANTIFY is designed in a classical workflow manner consisting of four-step types: (1) circuit synthesis, (2) gate level transpilation (e.g. translation from one gate set into another), (3) circuit optimization, and (4) analysis and verification. It also provides several metrics to verify the circuit under study, such as the number of Clifford+T (T-count), Hadamard, and CNOT gates, as well as the depth of the circuit and the Clifford+T gates (T-depth).

- In the rapidly evolving field of quantum software, it is paramount to ensure the presence of quality assurance measures, especially if quantum computers are to be used on large-scale real-world applications in the following years. This is what Díaz Muñoz A. et al. [49] set out to do by accommodating a series of classical quality metrics to the quantum realm, in addition to introducing novel measurements geared specifically towards hybrid (quantum/classical) systems maintainability. The paper expands upon the work done by J. A. Cruz-Lemus et al. [45] to develop a set of quantum software-specific metrics in 2 main areas. First, they introduce numerous metrics for gate counts that were not mentioned in the original work, such as counts for S, T, RX, RY, RZ, CP, and Fredkin gates among others. Second, they explore the Number of initialization and restart operations via the following metrics: Number and Percentage of qubits with any reset (to 0 state) or initialize (to arbitrary state) operations.

- SupermarQ [50] attempts to methodically adapt benchmarking methodology from classical computing to the quantum one. While the work is primarily focused on quantum benchmark design, the authors do come up with 6 metrics termed feature vectors to evaluate quantum computer performance on said benchmarks. Program communication, which ranges from zero for sparse connections to nearly one for dense connections, aims to measure the amount of communication required between qubits. Meanwhile, Critical-Depth, representing the circuit’s minimal time, focuses on two-qubit interactions, larger numbers indicating greater serialization. The significance of entanglement in a given circuit, known as the Entanglement Ratio, is also captured by measuring the proportion of 2 qubit interactions. Parallelism quantifies the amount of parallel operations that a certain algorithm maintains without being majorly affected by correlated noise events (cross-talk). Applications with high parallelism pack many operations into a limited circuit depth; as a result, their parallelism characteristic is near to 1. Qubit activity is captured throughout execution by Liveness, which shows the frequency of active vs idle qubits. Lastly, Measurement emphasizes reset operations and mid-circuit measurement, relating their frequency to the overall depth of the circuit.

5. Challenges Facing the Development of Quantum Software Metrics

6. Quantum Software Measurement Approaches Based on COSMIC ISO 19761

6.1. Overview of COSMIC ISO 19761

6.1.1. Key Principles of COSMIC ISO 19761

- Entry (E): Represents data entering the system from an external user or another system.

- Exit (X): Involves data exiting the system, typically in response to an entry or internal process.

- Read (R): Refers to the system accessing or retrieving data from a persistent storage.

- Write (W): Indicates the storage or writing of data into persistent storage.

6.1.2. Benefits of COSMIC ISO 19761

- Technology-Independent: COSMIC is designed to be neutral. It can be applied to a wide variety of software domains, including traditional business systems, real-time systems, and more complex areas such as telecommunications, control systems, and embedded software. This adaptability holds promise for quantum systems, where standardized measurement approaches are still emerging.

- Accuracy and Precision: By focusing on functional user requirements and the actual interactions between the system and its users, COSMIC offers precise and repeatable measurements. This level of accuracy is crucial for project estimation, cost analysis, and performance benchmarking.

6.1.3. COSMIC in the Context of Quantum Software

6.2. The three Quantum COSMIC Measurement Approaches

6.2.1. Approach 1 [22]: Gates’ Occurrences

- Identify each circuit as a system.

- Identify each gate as a functional process and count gates.

- Assign one Entry and Exit data movement per gate.

- Identify measurement commands as Data Writes.

- Identify reads from classical bits as Data Reads.

- Assign 1 CFP for each Entry, Exit, Read, and Write.

- Aggregate CFPs for each functional process to calculate its size.

- Aggregate all CFPs to determine the system’s functional size.

6.2.2. Approach 2 [23]: Gates’ Types

Directives for identifying the functional processes:

- An operator acts on qubits, and common action leads to an operator type. For instance, if a circuit contains an X gate acting on qubit and also contains an X gate acting on qubit , identify one X gate functional process type. Similarly, for a gate with qubit controlling and a gate with qubit controlling .

- Identify an Input functional process that conveys the input state(s).

- A vector (string of bits) and a separate value are considered different types.

- Identify one functional process for all operators with a common action in the circuit.

- Identify one functional process for n-tensored operator variants, identifying another functional process for each different n.

- Identify one functional process type for each operator type defined by a human user (these operators are often indicated by in the literature).

6.2.3. Approach 3 [24]: Q-COSMIC

The three phases of a Q-COSMIC analysis:

Strategy

- Determine the purpose of the COSMIC measurement.

- Define the functional users and identify each as a functional process.

- Specify the scope of the Functional User Requirements (FURs) to be measured.

Mapping

- Map the FURs onto a COSMIC Generic Software Model.

- Identify the data movements needed for specific software functionality.

Measurement

- Count and aggregate the data movements for each use case, with each movement representing functionality that contributes to the size of the software project/system.

6.3. Quantum Algorithm Classes

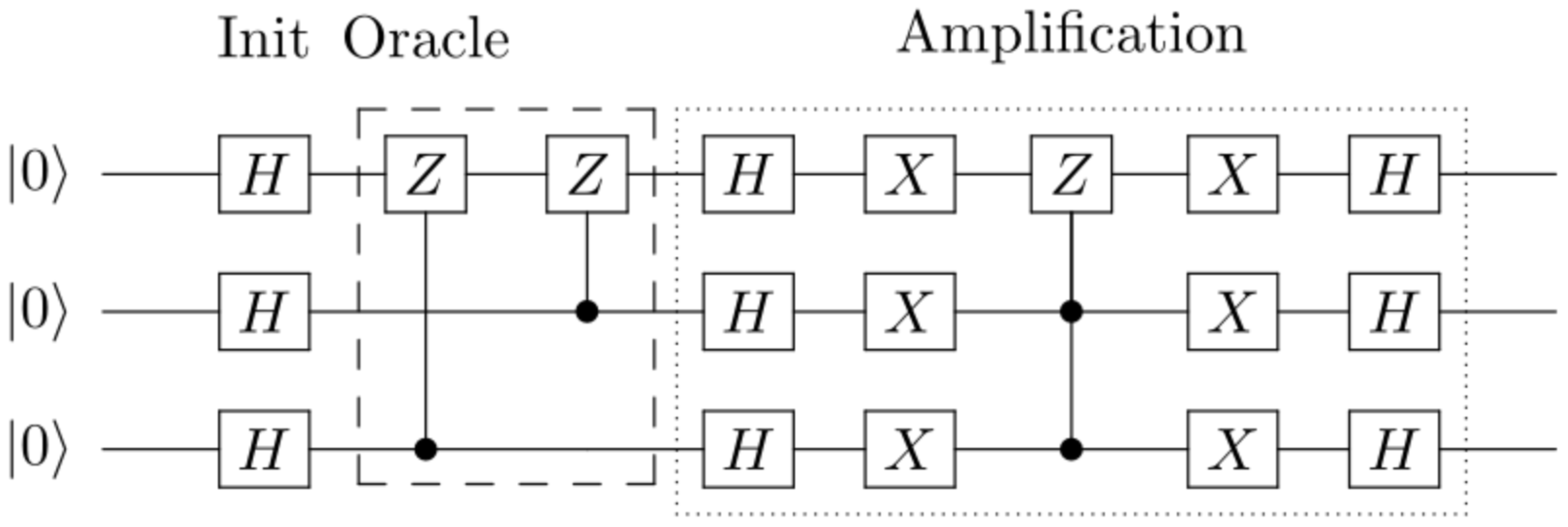

- Grover’s Algorithm for the Quantum Search class, due to its efficiency in searching unstructured databases. Figure 1 shows the circuit implementing Grover’s algorithm.

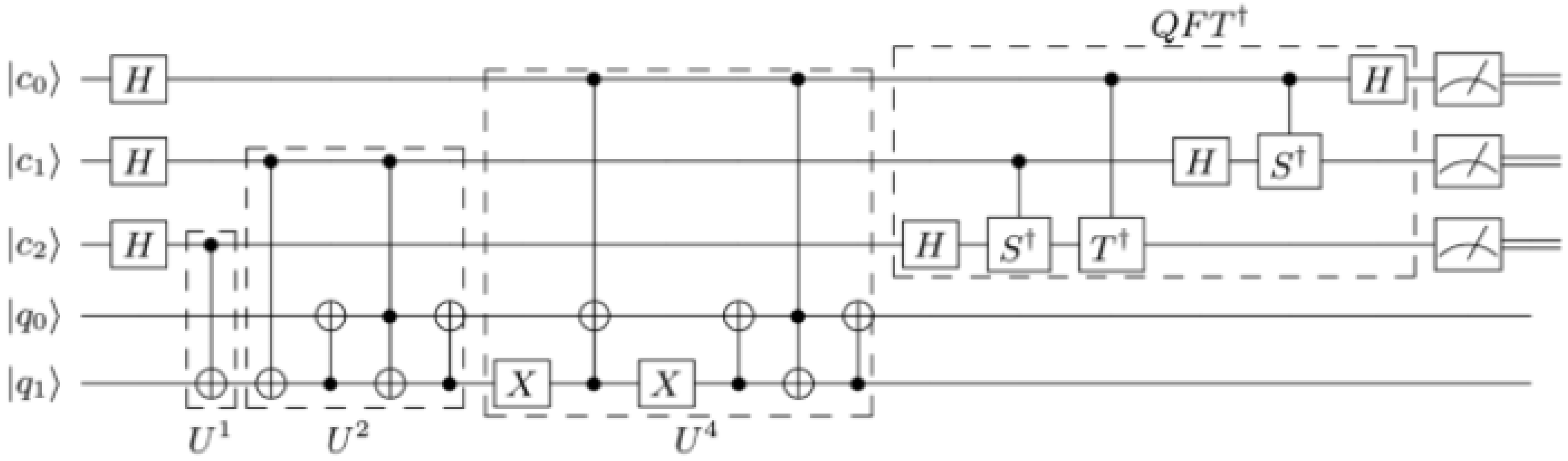

- Shor’s Algorithm for the QFT class, since it is one of the most famous applications. Shor’s algorithm uses the QFT to find patterns that help in factoring large numbers, solving a problem that classical computers find hard. This makes it a potential threat to modern encryption methods, which rely on the difficulty of factoring large numbers to secure data. Figure 2 is a simplified circuit implementing Shor’s algorithm to find the prime factors of 21.

6.4. Measurement Comparison

Approach 1 [22]: Gates’ Occurrences

- 18 quantum gates, where 1 functional process is identified for each gate, with 1 entry and 1 exit for each process.

- 3 measurement operations, where we identified 1 write operation and 1 read operation for each (the measurement operation is omitted from the circuit for brevity).

- 20 quantum gates, where 1 functional process is identified for each gate, with 1 entry and 1 exit for each process.

- 3 measurement operations, where we identified 1 write and 1 read for each.

Approach 2 [23]

-

Input Functional Processes

- –

- Identify a functional process for the input vector. Count 1 Entry and 1 Write

-

Operation Functional Processes

- –

- Identify 3 functional processes for the Hadamard, Controlled Z, and X gates acting on the input vector. Count 3 Entry, 3 Read, and 3 Write.

-

Measurement Functional Processes

- –

- Identify a functional process for measuring the input vector. Count 1 Entry, 1 Read, and 1 Write.

-

Input Functional Processes

- –

- Identify a functional process for the input vector consisting of qubits (c0, c1, c2). Count 1 Entry and 1 Write.

- –

- Identify a functional process for the input vector consisting of qubits (q0, q1). Count 1 Entry and 1 Write.

-

Operation Functional Processes

- –

- Identify 3 functional processes for the Hadamard, , and gates acting on the input vector consisting of qubits (c0, c1, c2). Count 3 Entry, 3 Read, and 3 Write.

- –

- Identify 2 functional processes for the CNOT and X gates acting on the input vector consisting of qubits (q0, q1). Count 2 Entry, 2 Read, and 2 Write.

-

Measurement Functional Processes

- –

- Identify a functional process for measuring the input vector consisting of qubits (c0, c1, c2). Count 1 Entry, 1 Read, and 1 Write.

- –

- Identify a functional process for measuring the input vector of qubits (q0, q1). Count 1 Entry, 1 Read, and 1 Write.

Approach 3 [24]: Q-COSMIC

6.5. Discussion

7. Conclusions

7.1. Main Contributions

7.2. Limitations and Future Work

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

| 1 | Unless stated otherwise, Measurements in this paper does not refer to the measurement of a quantum particle, which collapses its quantum state, but rather refers to concepts related to measuring the size and attributes of a quantum system. |

| 2 | Most of the metrics and measurement in the literature review in section 4 are specific to analyzing system properties such as size, performance, scalability and related characteristics. However, there exists, one might argue, a crucial test [59] that could be considered a metric as well. This test, which is device independent, certifies whether the system is indeed quantum. For instance, if a company claims to offer a Quantum Random Number Generator (QRNG) device, this test would verify whether the device truly harnesses the intrinsic uncertainties of quantum mechanical systems to generate randomness, rather than relying on classical processes. |

References

- Horowitz, M.; Grumbling, E. (Eds.) Quantum Computing: Progress and Prospects; National Academies Press: Washington, DC, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Martonosi, M.; Roetteler, M. Next Steps in Quantum Computing: Computer Science’s Role. arXiv Preprint 2019, arXiv:1903.10541. [Google Scholar]

- Hennessy, J. L.; Patterson, D. A. Computer Architecture: A Quantitative Approach, 6th ed.; Morgan Kaufmann: Cambridge, MA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Stallings, W. Computer Organization and Architecture, 11th ed.; Pearson: Boston, MA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Srinivasan, S.; Engel, G. The Performance Analysis of Computer Systems: Techniques and Tools for Efficient Performance Engineering; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Cross, A. W.; Bishop, L. S.; Sheldon, S.; Nation, P. D.; Gambetta, J. M. Validating Quantum Computers Using Randomized Model Circuits. Phys. Rev. A 2019, 100, 032328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wack, A.; Paik, H.; Javadi-Abhari, A.; Jurcevic, P.; Faro, I.; Gambetta, J. M.; Johnson, B. R. Quality, Speed, and Scale: Three Key Attributes to Measure the Performance of Near-Term Quantum Computers. arXiv 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Ballance, C. J.; Harty, T. P.; Linke, N. M.; Sepiol, M. A.; Lucas, D. M. High-Fidelity Quantum Logic Gates Using Trapped-Ion Hyperfine Qubits. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2016, 117, 060504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nielsen, M. A.; Chuang, I. L. Quantum Computation and Quantum Information, 10th Anniversary ed.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Preskill, J. Quantum Computing in the NISQ Era and Beyond. Quantum 2018, 2, 79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lincke, R.; Lundberg, J.; Löwe, W. Comparing Software Metrics Tools. In Proceedings of the 2008 International Symposium on Software Testing and Analysis; ACM: New York, NY, USA, 2008; pp. 131–142. [Google Scholar]

- Fenton, N. E.; Neil, M. Software Metrics: Successes, Failures, and New Directions. J. Syst. Softw. 1999, 47, (2–3). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Savchuk, M. M.; Fesenko, A. V. Quantum Computing: Survey and Analysis. Cybern. Syst. Anal. 2019, 55, 10–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohanty, S. N. Models and Measurements for Quality Assessment of Software. ACM Comput. Surv. 1979, 11, 251–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sommerville, I. Software Engineering, 9th ed.; Addison-Wesley: Boston, MA, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Fenton, N.; Pfleeger, S. L. Software Metrics: A Rigorous and Practical Approach; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Pressman, R. S. Software Engineering: A Practitioner’s Approach, 8th ed.; McGraw-Hill: New York, NY, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Sicilia, M. A.; Mora-Cantallops, M.; Sánchez-Alonso, S.; García-Barriocanal, E. Quantum Software Measurement. In Quantum Software Engineering; Serrano, M. A., Pérez-Castillo, R., Piattini, M., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J. Some Size and Structure Metrics for Quantum Software. In Proceedings of the 2021 IEEE/ACM 2nd International Workshop on Quantum Software Engineering (Q-SE), Madrid, Spain; 2021; pp. 22–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abran, A.; Robillard, P. N. Function Points Analysis: An Empirical Study of Its Measurement Processes. IEEE Trans. Softw. Eng. 1996, 22, 895–909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- COSMIC. Functional Size Measurement – Method Overview. Available online: https://cosmic-sizing.org (accessed on 2024).

- Khattab, K.; Elsayed, H.; Soubra, H. Functional Size Measurement of Quantum Computers Software. Presented at IWSM-Mensura, 2022.

- Lesterhuis, A. COSMIC Measurement Manual for ISO 19761, Measurement of Quantum Software Circuit Strategy; A Circuit-Based Measurement Strategy, 2024.

- Valdes-Souto, F.; Perez-Gonzalez, H. G.; Perez-Delgado, C. A. Q-COSMIC: Quantum Software Metrics Based on COSMIC (ISO/IEC 19761). arXiv Prepr. 2024, arXiv:2402.08505. [Google Scholar]

- Shor, P. W. Polynomial-Time Algorithms for Prime Factorization and Discrete Logarithms on a Quantum Computer. SIAM Rev. 1999, 41, 303–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grover, L. K. A Fast Quantum Mechanical Algorithm for Database Search. In Proceedings of the Twenty-Eighth Annual ACM Symposium on Theory of Computing; ACM: New York, NY, USA, 1996; pp. 212–219. [Google Scholar]

- Patterson, D. A.; Hennessy, J. L. Computer Organization and Design RISC-V Edition: The Hardware/Software Interface; Morgan Kaufmann: Cambridge, MA, 2021; ISBN 9780128245583. [Google Scholar]

- Tanenbaum, A. S.; Bos, H. Modern Operating Systems, Global Edition; Pearson Education: United Kingdom, 2023; ISBN 9781292727899. [Google Scholar]

- Dumitras, T.; Narasimhan, P. Why Do Upgrades Fail and What Can We Do About It?: Toward Dependable, Online Upgrades in Enterprise System Software. In Lecture Notes in Computer Science; Springer: 2009; Vol. 5927, pp. 97–112. [CrossRef]

- Rusu, A.; Lysaght, P. Thermal Management in High-Performance Computing: Techniques and Trends. IEEE Trans. Comput.-Aided Des. Integr. Circuits Syst. 2021, 40, 2154–2167. [Google Scholar]

- Kirk, D. B.; Hwu, W. W. Programming Massively Parallel Processors: A Hands-on Approach, 3rd ed.; Morgan Kaufmann: Cambridge, MA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Henning, J. L. SPEC CPU2000: Measuring CPU Performance in the New Millennium. IEEE Comput. 2000, 33, 28–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silberschatz, A.; Galvin, P. B.; Gagne, G. Operating System Concepts, 10th ed.; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Sinha, B. R.; Dey, P. P.; Amin, M.; Badkoobehi, H. Software Complexity Measurement Using Multiple Criteria. J. Comput. Sci. Coll. 2013, 28, 155–162. [Google Scholar]

- Heitlager, I.; Kuipers, T.; Visser, J. A Practical Model for Measuring Maintainability. In Proceedings of the 6th International Conference on the Quality of Information and Communications Technology (QUATIC 2007), Lisbon, Portugal, 2007, 12–14 Sept 2007; IEEE; pp. 30–39. [Google Scholar]

- Srinivasan, K. P.; Devi, T. A Comprehensive Review and Analysis on Object-Oriented Software Metrics in Software Measurement. Int. J. Comput. Sci. Eng. 2014, 6. [Google Scholar]

- Soubra, H.; Chaaban, K. Functional Size Measurement of Electronic Control Units Software Designed Following the AUTOSAR Standard: A Measurement Guideline Based on the COSMIC ISO 19761 Standard. In Proceedings of the 2012 Joint Conference of the 22nd International Workshop on Software Measurement and the 7th International Conference on Software Process and Product Measurement, Assisi, Italy, 2012, 17–19 Oct 2012; IEEE; pp. 45–54. [Google Scholar]

- Abran, A.; Symons, C.; Ebert, C.; Vogelezang, F.; Soubra, H. Measurement of Software Size: Contributions of COSMIC to Estimation Improvements. Proceedings of The International Training Symposium, Marriott Bristol, United Kingdom; 2016; pp. 259–267. [Google Scholar]

- NESMA (Netherlands Software Metrics Association). Nesma on Sizing - NESMA Function Point Analysis (FPA) Whitepaper; 2018.

- Bishop, L. S.; Bravyi, S.; Cross, A.; Gambetta, J. M.; Smolin, J. Quantum Volume. Quantum Volume. Technical Report 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Donkers, H.; Mesman, K.; Al-Ars, Z.; Möller, M. QPack Scores: Quantitative Performance Metrics for Application-Oriented Quantum Computer Benchmarking. arXiv Preprint arXiv:2205.12142, arXiv:2205.12142 2022.

- Fedichkin, L.; Fedorov, A.; Privman, V. Measures of Decoherence. Quantum Inf. Comput. 2003, 5105, SPIE. [Google Scholar]

- Sete, E. A.; Zeng, W. J.; Rigetti, C. T. A Functional Architecture for Scalable Quantum Computing. In 2016 IEEE International Conference on Rebooting Computing (ICRC); IEEE, 2016; pp 1–6.

- Finžgar, J. R.; Ross, P.; Hölscher, L.; Klepsch, J.; Luckow, A. Quark: A Framework for Quantum Computing Application Benchmarking. In 2022 IEEE International Conference on Quantum Computing and Engineering (QCE); IEEE, 2022; pp 226–237.

- Cruz-Lemus, J. A.; Marcelo, L. A.; Piattini, M. Towards a Set of Metrics for Quantum Circuits Understandability. In International Conference on the Quality of Information and Communications Technology; Springer International Publishing: Cham, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Martiel, S.; Ayral, T.; Allouche, C. Benchmarking Quantum Coprocessors in an Application-Centric, Hardware-Agnostic, and Scalable Way. IEEE Trans. Quantum Eng. 2021, 2, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghoniem, O.; Elsayed, H.; Soubra, H. Quantum Gate Count Analysis. In 2023 Eleventh International Conference on Intelligent Computing and Information Systems (ICICIS); IEEE, 2023.

- Oumarou, O.; Paler, A.; Basmadjian, R. QUANTIFY: A Framework for Resource Analysis and Design Verification of Quantum Circuits. In 2020 IEEE Computer Society Annual Symposium on VLSI (ISVLSI); IEEE, 2020.

- Muñoz, A. D.; Rodríguez Monje, M.; Piattini Velthuis, M. Towards a Set of Metrics for Hybrid (Quantum/Classical) Systems Maintainability. J. Univ. Comput. Sci. 2024, 30, 25–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomesh, T.; Gokhale, P.; Omole, V.; Ravi, G. S.; Smith, K. N.; Viszlai, J.; Wu, X.-C.; Hardavellas, N.; Martonosi, M. R.; Chong, F. T. Supermarq: A Scalable Quantum Benchmark Suite. In 2022 IEEE International Symposium on High-Performance Computer Architecture (HPCA); IEEE, 2022; pp 587–603.

- Shukla, A., Sisodia, M., Pathak, A. (2020). "Complete characterization of the directly implementable quantum gates used in the IBM quantum processors." Physics Letters A, 384(18), 126387.

- Chen, J. S., Nielsen, E., Ebert, M., Inlek, V., Wright, K., Chaplin, V., ... Gamble, J. (2024). "Benchmarking a trapped-ion quantum computer with 30 qubits". Quantum, 8, 1516.

- Kalajdzievski, T., Arrazola, J. M. (2019). "Exact gate decompositions for photonic quantum computing". Physical Review A, 99(2), 022341.

- Linke, Norbert M., Dmitri Maslov, Martin Roetteler, Shantanu Debnath, Caroline Figgatt, Kevin A. Landsman, Kenneth Wright, and Christopher Monroe. "Experimental comparison of two quantum computing architectures." Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 114, no. 13 (2017): 3305-3310.

- Souto, F. V., Pedraza-Coello, R., Olguín-Barrón, F. C. (2020). "COSMIC Sizing of RPA Software: A Case Study from a Proof of Concept Implementation in a Banking Organization". In IWSM-Mensura.

- Bağrıyanık, S., Karahoca, A., Ersoy, E. (2015). "Selection of a functional sizing methodology: A telecommunications company case study". Global Journal on Technology, 7(7), 98-108.

- Qiskit. Grover’s Algorithm. Available online: https://github.com/qiskit-community/qiskit-textbook/blob/main/content/ch-algorithms/grover.ipynb (accessed on 2024).

- Skosana, U.; Tame, M. Demonstration of Shor’s Factoring Algorithm for n=21 on IBM Quantum Processors. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pironio, S.; Acín, A.; Massar, S.; de La Giroday, A. B.; Matsukevich, D. N.; Maunz, P.; Monroe, C. Random Numbers Certified by Bell’s Theorem. Nature 2010, 464, 1021–1024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Approach | Data Movement Type | Grover’s | Shor’s |

| 1 | Entry | 18 | 20 |

| Exit | 18 | 20 | |

| Write | 3 | 3 | |

| Read | 3 | 3 | |

| Total | 42 CFPs | 46 CFPs | |

| 2 | Entry | 5 | 9 |

| Write | 5 | 9 | |

| Read | 4 | 7 | |

| Total | 14 CFPs | 25 CFPs | |

| 3 UC1 | Entry | NA | 2 |

| Exit | NA | 2 | |

| QEntry | NA | 1 | |

| QExit | NA | 1 | |

| Total | NA | 6 CFPs | |

| 3 UC2 | Total | NA | 4 CFPs |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).