1. Introduction

Immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs) have revolutionized modern oncology, offering a powerful strategy to enhance the patient's anti-tumor immunity. The key targets of these therapies are PD-1 (Programmed Cell Death 1) on T cells, its ligand PD-L1 (Programmed Cell Death-Ligand 1) on tumor cells, and CTLA-4 (Cytotoxic T-Lymphocyte Associated Protein 4), an inhibitory receptor on T cells. Under normal conditions, immune checkpoints help maintain immune balance by suppressing excessive T-cell activation, thereby preventing autoimmunity. However, some tumors overexpress PD-L1, and by binding to PD-1 on the surface of T cells, they can reduce the host’s immune response. The inhibition of these checkpoints can enhance T-cell activity against tumors [

1,

2,

3,

4,

5]. The significance of this discovery was recognized in 2018 when James P. Allison and Tasuku Honjo were awarded the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine for their work on the exact mechanism of immune checkpoint blockade [

6].

The first FDA approval for immune checkpoint inhibitors came in 2011 for metastatic melanoma, followed by approvals for lung cancer, urothelial carcinoma, cervical cancer, and others over the next decade, with the most recent approval for metastatic malignant pleural mesothelioma [

7,

8,

9]. Numerous studies have demonstrated their efficacy either as monotherapy or in combination with chemotherapy [

10,

11,

12,

13,

14,

15,

16,

17,

18,

19,

20]. However, specific response patterns—such as pseudoprogression, hyperprogression, and dissociated response—have presented significant challenges for oncologists, radiologists, and nuclear medicine physicians [

21,

22,

23,

24,

25,

26,

27,

28]. Established criteria like RECIST 1.1 (Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors) quickly proved inadequate in assessing pseudoprogression, which is defined as an initial increase in tumor burden followed by a response to treatment. This led to the creation of the modified guideline Immune RECIST (iRECIST) in 2017, introducing the term immune unconfirmed progression (iUCPD), which requires a follow-up scan in 6 to 8 weeks to distinguish true progression from a potential treatment response [

29,

30,

31,

32]. The reported incidence of pseudoprogression varies based on factors such as cancer type and the specific ICI administered, but it is estimated to be approximately 6% [

33]. The accurate assessment of pseudoprogression is crucial, as it can prevent the premature discontinuation of an effective treatment.

Since its introduction in the 1990s and widespread adoption in the early 2000s, F-18 FDG PET/CT has become a key component in the diagnostic algorithms for many cancer types. By combining morphological imaging with the visualization of cellular glucose metabolism, it has the potential to detect progressive disease earlier than conventional imaging methods. Metabolic changes in primary tumor masses or distant metastases are often seen before changes in size appear on conventional CT or MRI [

34,

35]. For some cancer types, PET/CT has been shown to have higher specificity and sensitivity than CT alone. Niikura et al. (2011) demonstrated that PET/CT detects distant metastases in breast cancer patients with higher sensitivity (97.4%) and specificity (91.2%) compared to conventional imaging alone (85.9% and 67.3%, respectively) [

36]. This makes PET/CT a valuable tool for the timely assessment of therapy response. Beyond response evaluation, PET/CT is also capable of detecting early immune-related adverse events (irAE). Additionally, Parihar and Wahl (2022) demonstrated that 18F-FDG PET/CT is superior to conventional imaging for detecting irAEs, particularly those that may require cessation of therapy, such as pneumonitis, colitis, hypophysitis, and adrenal insufficiency [

37].

In this study, we analyzed data from 93 patients with different cancer types undergoing immunotherapy, whose response to treatment was assessed with F-18 FDG PET/CT. The aim of the study was to demonstrate the critical role of PET/CT in guiding treatment decisions and to highlight the importance of careful evaluation to distinguish true progression from pseudoprogression.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Patient Selection

This retrospective study included 698 patients undergoing immunotherapy between March 2022 and February 2024. A smaller cohort of 93 patients was selected. Inclusion criteria required patients to have a staging PET/CT performed at our facility in the given time interval and a minimum of another 2 PET/CT scans, so we can perform an analysis on a potential pseudoprogression. Patients with incomplete clinical or imaging data were excluded from the analysis.

2.2. Data Collection

Demographic data (age, gender), clinical characteristics (ICD-10 diagnosis, initial TNM staging), name of administrated immunotherapeutic drug, therapy regimens (pre- and post-PET/CT) and dates and results of the PET/CT scans were collected – complete response (CR), partial response (PR), stable disease (SD), progressive disease (PD), immune unconfirmed progressive disease (iUCPD), or immune confirmed progressive disease (iCPD). PET/CT findings were analyzed according to iRECIST criteria. iUCPD cases were analyzed to determine whether progression was confirmed (iCPD in subsequent scans) or not confirmed (PR, SD or CR in subsequent scans). Pseudoprogression cases were identified as iUCPD not followed by confirmed progression. Changes in the therapy regimes were noted for each patient after PET/CT scan.

2.3. PET/CT Protocols

All PET/CT scans were performed using a Siemens Biograph mCT 64. Patients fasted for at least 10 hours prior to the scan and followed a low carbohydrate diet on the day before the scan. F-18 FDG was injected intravenously at a dose of 3 MBq/kg, and images were recquired approximately 60 minutes post-injection. Whole-body imaging was conducted from the skull base to the mid-thigh using continuous bed movement with a speed of 1.6 mm/s.

CT imaging was performed with CARE Dose 4D and CARE kV, applying a quality reference of 50 mAs and a tube voltage of 120 kV for a 70 kg patient. The slice thickness was set to 5 mm. Image reconstruction was carried out using the TruX + TOF (UltraHD-PET) algorithm, with a matrix size of 200 × 200 and a Gaussian filter of 5 mm full-width at half maximum (FWHM). Attenuation correction was applied using CT data.

2.4. Image Analysis

Images were reviewed by two experienced nuclear medicine specialists using syngo.via MI Applications. Findings were classified according to iRECIST criteria.

2.5. Statistical Analysis

Descriptive statistics were applied to summarize demographic and clinical data, including age, gender, administered immunotherapeutic drug, ICD-10 diagnoses and initial TNM staging. The percentage of patients who had a therapy change after a PET/CT scan result in the given time interval was noted. Additionally, therapy changes were calculated as a proportion of the total number of PET/CT scans performed. Overall response (CR, PR, SD, PD) were expressed as percentage of the number of patients. Analysis of iUCPD cases and pseudoprogression was also conducted. Data visualization was used to present key findings. All analyses were conducted using Excel.

2.6. Ethical Considerations

This study was conducted using anonymized data. Written approval to use the data for research purposes was granted by the hospital's administration. All data were fully anonymized, and no identifiable patient information was included in the analysis. As the study was retrospective and anonymized, individual patient consent was waived.

3. Results

3.1. Data Analysis

3.1.1. Demographics

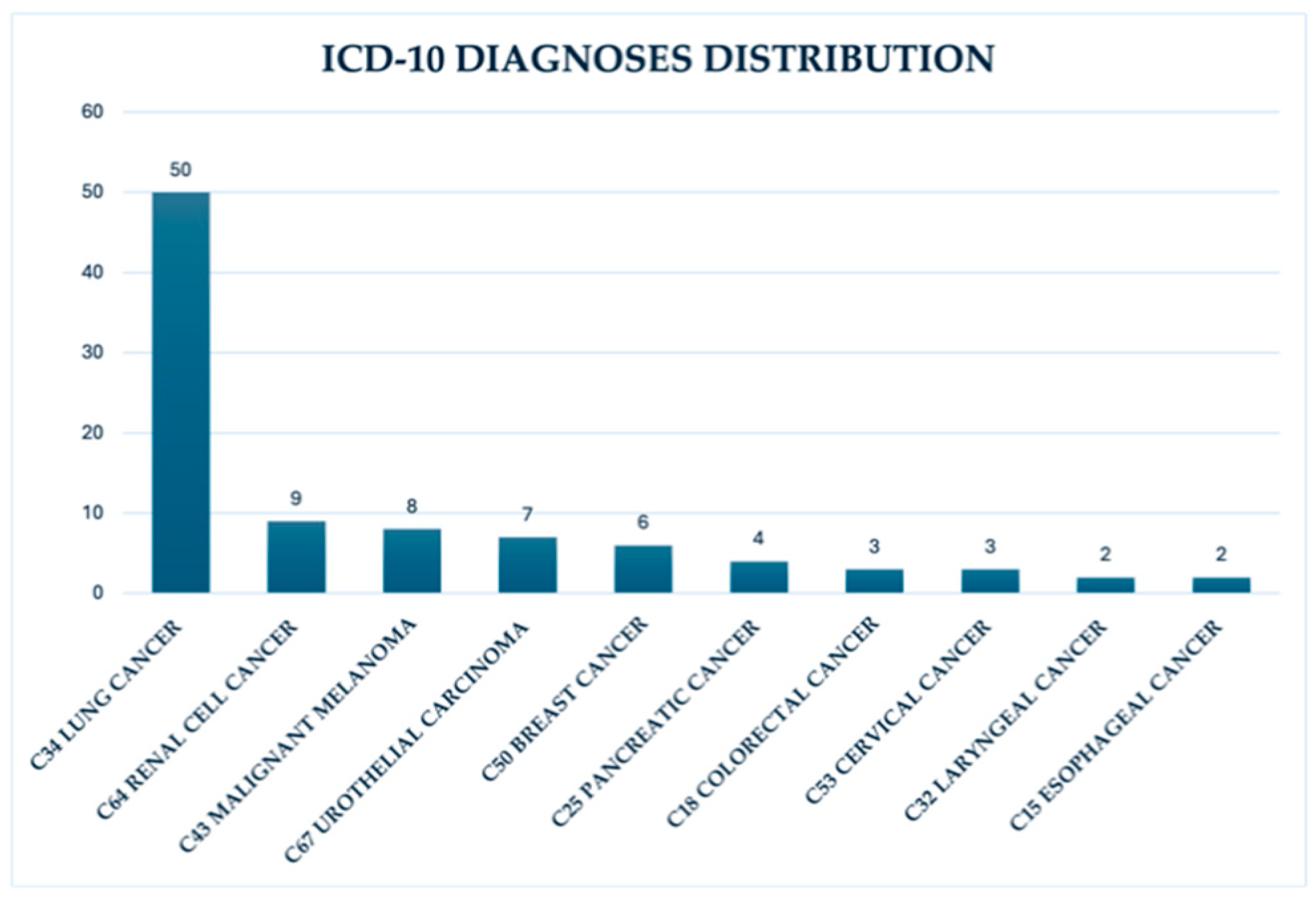

Data of a total of 698 patients undergoing immunotherapy between March 2022 and mid-February 2024 was collected. From this cohort, a subgroup of 93 patients was selected for more detailed analysis. The median age of the subgroup was 65 years (between 28–83 years old at time of evaluation). The gender distribution was 63% male and 37% female patients. The most common ICD-10 diagnoses were lung cancer C34 (53.8%), renal cell cancer C64 (9.7%) and malignant melanoma C43 (8.6%). Other diagnoses accounted for 27.9% of cases - urothelial carcinoma, breast cancer and others. (

Figure 1)

3.1.2. Immunotherapy Drug Distribution

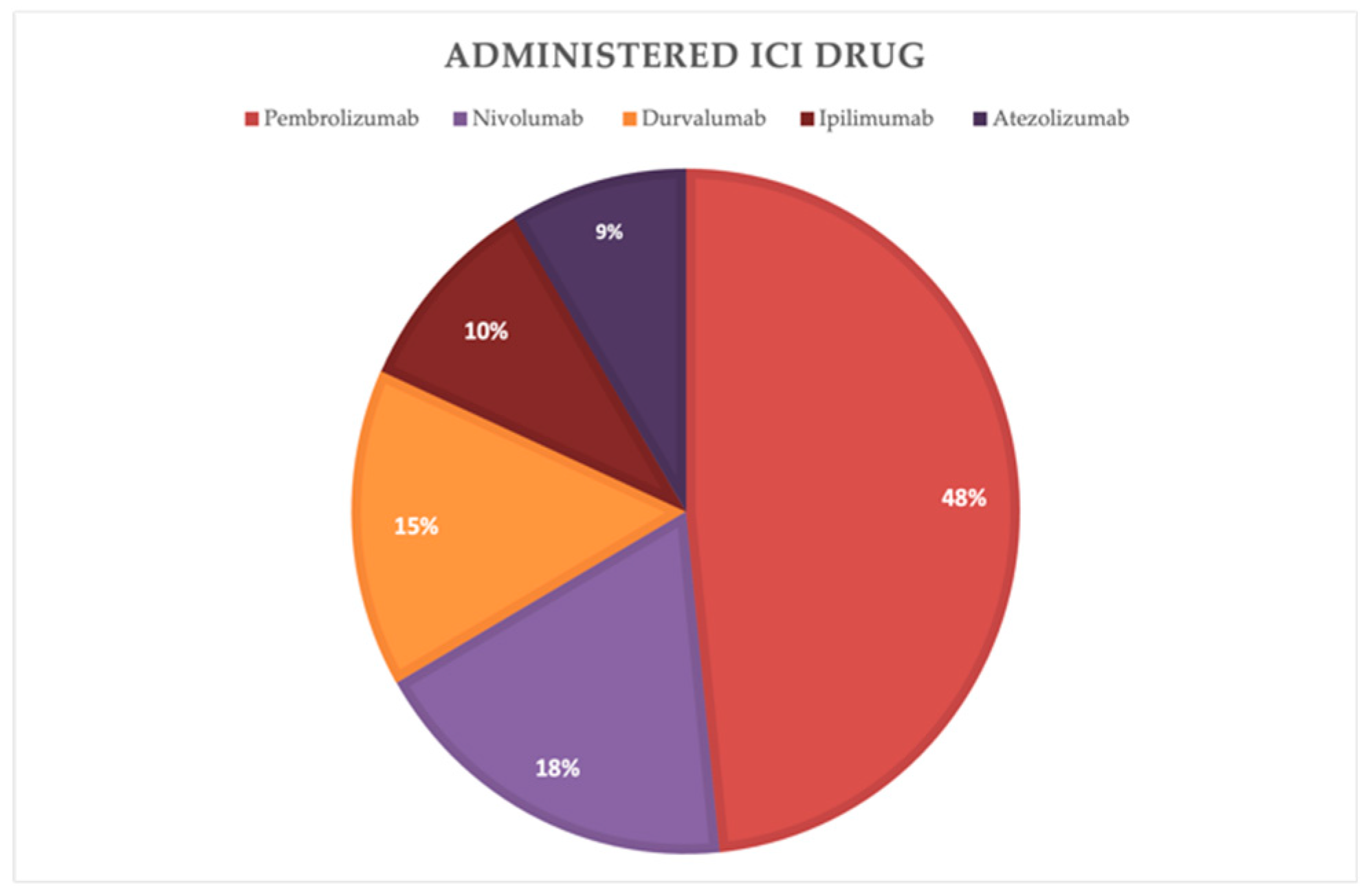

The distribution of the administered immunotherapy drugs among the cohort was analyzed. Pembrolizumab was the most commonly administered drug, accounting for 48 % of the patients. Followed by Nivolumab with 18 %, Durvalumab with 15%, Ipilimumab with 10% and Atezolizumab with 9%. (

Figure 2)

3.1.3. PET/CT Findings

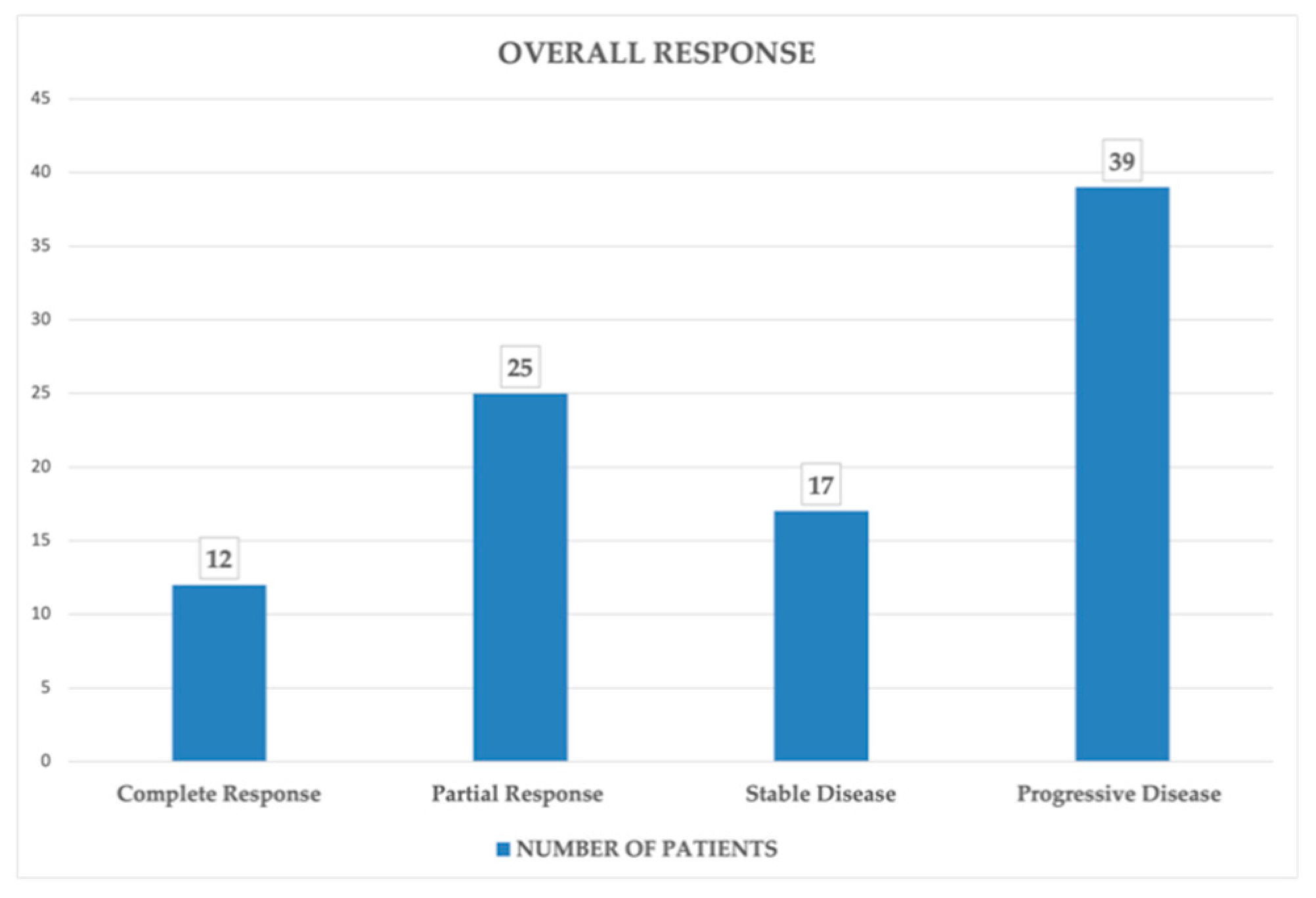

A total of 498 PET/CT scans were performed for the 93 patients, with some of them having up to 9 scans in the time frame. The overall response to therapy of the selected patients according to iRECIST criteria was as it follows: (

Figure 3)

Complete response (CR): 12 patients, accounting for 13%

Partial response (PR): 25 patients, accounting for 27%

Stable disease (SD): 17 patients, accounting for 18%

Progressive disease (PD): 39 patients, accounting for 42%

3.1.4. Therapy Changes

Therapy adjustments were recorded for 39 patients (42% of the patient number) with a total of 60 changes across all patients, resulting from some patients having more than one therapy regimen change. Therapy changes accounted for 12.05% of all 498 PET/CT scans performed. These adjustments were most frequently prompted by findings of progressive disease.

3.1.5. Pseudoprogression Analysis

Further analysis was conducted to distinguish true progression from pseudoprogression. iUCPD cases were classified as pseudoprogression when subsequent scans showed PR, SD or CR, rather than progressing to iCPD. Out of the 93 included patients, 5 showed a SD and 4 showed PR on the required follow-up scan after an iUCPD, classifying as them as having pseudoprogression. No cases with a follow-up CR were registered. This accounts for 9,7 % of all patients.

4. Discussion

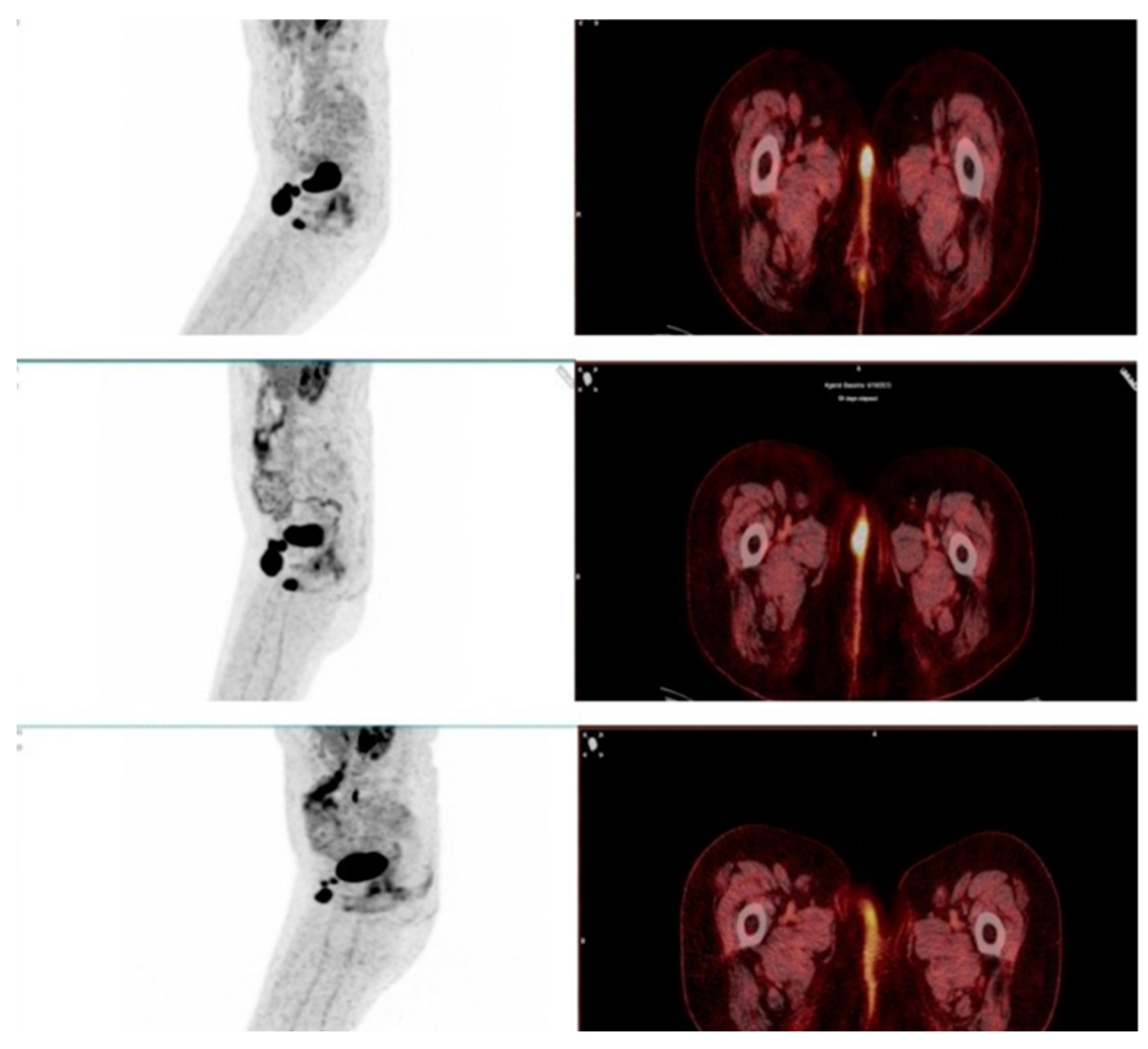

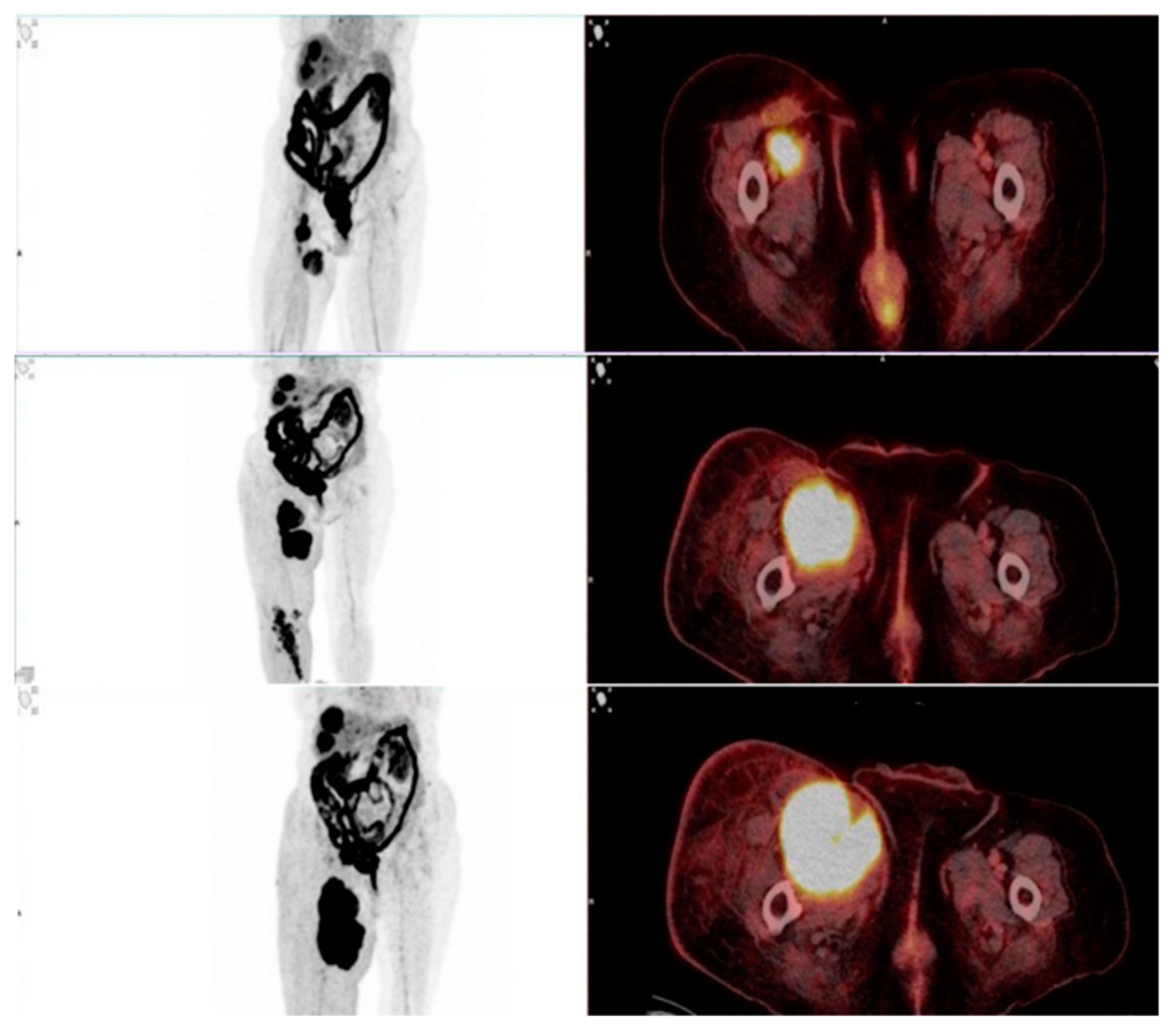

This study evaluated the role of F-18 FDG PET/CT in assessing therapy response in patients undergoing immunotherapy with immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs). One of the key findings was the ability of PET/CT to differentiate true progressive disease from pseudoprogression, which remains a major challenge in immunotherapy monitoring. Among the 93 patients, 9 showed stable disease (SD) or partial response (PR) on the required follow-up scans after 6–8 weeks and were therefore classified as pseudoprogression (

Figure 4 and

Figure 5). The estimated pseudoprogression incidence in our study – 9,7% - aligns with previously reported data. A systematic review and meta-analysis by Park et al. found an overall pseudoprogression incidence of 6% and less than 10%, with slight differences between cancer types, administered ICI and differences coming from the different definitions of pseudoprogression [

33]. These results further support our findings and confirm that pseudoprogression remains a relatively rare, but clinically significant phenomenon. Failing to correctly identify pseudoprogression may result in the premature discontinuation of a beneficial therapy, depriving patients of a potential long-term response.

As a hybrid imaging modality, PET/CT not only visualizes anatomical changes in primary tumors and metastatic sites, but also provides functional insights into tumor metabolism by measuring glucose uptake in cancer cells. This dual capability makes F-18 FDG PET/CT a valuable tool for routine oncologic follow-up. The ability of PET/CT to detect metabolic changes before morphological alterations appear is currently being investigated in various studies comparing the sensitivity and specificity of PET/CT with conventional imaging methods such as contrast-enhanced CT and MRI. Kostakoglu et al. demonstrated that FDG-PET/CT enables earlier detection of recurrent disease in patients with squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck, leading to significant management changes [

38]. This reinforces the role of PET/CT in timely therapy adjustments, as observed in our study, where 42% of patients had modifications in their treatment plans based on PET/CT findings. The data support the idea that PET/CT can support more personalized treatment strategies, helping to avoid unnecessary therapy discontinuations while identifying true disease progression at an earlier stage.

Additionally, PET/CT has been shown to detect early immune-related adverse events (irAEs), further highlighting its potential in immunotherapy monitoring. Recent studies have demonstrated the diagnostic value of PET/CT in identifying irAEs before clinical symptoms appear [

39]. Karlsen et al. examined the pros and cons of using F-18 FDG PET/CT for irAE detection and found that PET/CT successfully identified metabolic activation patterns linked to irAEs across multiple organs, including the colon, stomach, small intestine, kidneys, skin, lungs, joints, liver, lymph nodes, bone marrow, brain, heart, and endocrine glands [

40]. These findings suggest that PET/CT could serve as an early warning tool for detecting irAEs, allowing for prompt intervention, preventing life-threatening conditions, and reducing unnecessary treatment discontinuations.

This study has several strengths. The large dataset of 498 PET/CT scans in 93 patients provides a comprehensive evaluation of response patterns in immunotherapy-treated patients, making the findings robust. Additionally, the use of iRECIST criteria, which are specifically adapted for patients undergoing immunotherapy, ensures that response classification is standardized and clinically relevant. Another key strength is the real-world setting of this study, where PET/CT was utilized in routine clinical decision-making, enhancing the practical applicability of the results.

However, some limitations should be acknowledged. While iRECIST criteria are well-established for assessing immunotherapy response, they are primarily designed for CT-based morphological evaluation and do not incorporate metabolic changes. To address this, we applied iPERCIST criteria additionally, which are specifically designed for PET/CT-based response assessment [

41,

42]. In cases of disconcordance between the criteria, the final classification was determined by the more progressive outcome—i.e., in cases where iPERCIST indicated progressive disease (PD) while iRECIST showed stable disease (SD), the final response was adjudicated as PD with the progression being solely metabolic. However, iPERCIST is not yet widely adopted in clinical practice among nuclear medicine physicians, highlighting the need for standardized PET/CT-based response criteria.

Additionally, due to the retrospective nature of this study, long-term survival outcomes were not assessed, limiting our ability to determine the prognostic value of PET/CT in immunotherapy monitoring. Future studies should focus on validating PET/CT-based response criteria through prospective, multicenter research and correlating imaging findings with patient survival outcomes.

The findings of this study emphasize the need for further research to refine the role of PET/CT in immunotherapy monitoring. Future studies should focus on:

Standardizing and PET/CT-based response criteria that integrate both metabolic and morphological changes.

Investigating the predictive value of PET/CT findings for long-term survival outcomes in immunotherapy-treated patients.

Investigating the implementation of standard follow-up protocols in patients undergoing immunotherapy, as a screening method for irAEs.

5. Conclusions

This study reinforces the essential role of F-18 FDG PET/CT in monitoring immunotherapy response. With a pseudoprogression incidence of 9,7% and therapy modifications recorded in 42% of patients, PET/CT has demonstrated significant clinical utility. In addition to response evaluation, PET/CT can detect immune-related adverse events (irAEs) early, improving patient management. Future research should focus on optimizing PET/CT-based response criteria and correlating metabolic response with long-term survival outcomes to further improve personalized oncologic care.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Elena Popova and Sonya Sergieva; Data Collection, Elena Popova and Zlatina Zhelyazkova; Supervision, Rossitsa Krasteva and Sonya Sergieva; Writing—Original Draft Preparation, Elena Popova; Writing—Review and Editing, Elena Popova, Zlatina Zhelyazkova, and Teodor Sofiyanski; Contribution to Manuscript Development and Support, Teodor Sofiyanski.

Funding

This research received no external funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Institutional Review Boards of Unihospital Panagyurishte and Acibadem City Clinic Tokuda Hospital.

Informed Consent Statement

Patient consent was waived due to the retrospective and anonymized nature of the data.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| MDPI |

Multidisciplinary Digital Publishing Institute |

| DOAJ |

Directory of open access journals |

| TLA |

Three letter acronym |

| LD |

Linear dichroism |

References

- Hossain, M.A. A comprehensive review of immune checkpoint inhibitors for cancer treatment. Int. Immunopharmacol. 2024, 143, 113365, . [CrossRef]

- Sadeghi Rad, H.; Monkman, J.; Warkiani, M.E.; Ladwa, R.; O'Byrne, K.; Rezaei, N.; Kulasinghe, A. Understanding the tumor microenvironment for effective immunotherapy. Med. Res. Rev. 2021, 41, 1474–1498, . [CrossRef]

- Shiravand, Y.; Khodadadi, F.; Kashani, S.M.A.; Hosseini-Fard, S.R.; Hosseini, S.; Sadeghirad, H.; Ladwa, R.; O'Byrne, K.; Kulasinghe, A. Immune checkpoint inhibitors in cancer therapy. Curr. Oncol. 2022, 29, 3044–3060, . [CrossRef]

- Seidel, J.A.; Otsuka, A.; Kabashima, K. Anti-PD-1 and anti-CTLA-4 therapies in cancer: Mechanisms of action, efficacy, and limitations. Front. Oncol. 2018, 8, 86, . [CrossRef]

- Bagchi, S.; Yuan, R.; Engleman, E.G. Immune checkpoint inhibitors for the treatment of cancer: Clinical impact and mechanisms of response and resistance. Annu. Rev. Pathol. 2021, 16, 223–249, . [CrossRef]

- Zang, X. 2018 Nobel Prize in Medicine Awarded to Cancer Immunotherapy: Immune Checkpoint Blockade—A Personal Account. Genes Dis. 2018, 5, 302–303. [CrossRef]

- Ai, L.; Chen, J.; Yan, H.; He, Q.; Luo, P.; Xu, Z.; Yang, X. Research status and outlook of PD-1/PD-L1 inhibitors for cancer therapy. Drug Des. Devel. Ther. 2020, 14, 3625–3649, . [CrossRef]

- Vaddepally, R.K.; Kharel, P.; Pandey, R.; Garje, R.; Chandra, A.B. Review of indications of FDA-approved immune checkpoint inhibitors per NCCN guidelines with the level of evidence. Cancers 2020, 12, 738, . [CrossRef]

- U.S. Food and Drug Administration. FDA approves pembrolizumab with chemotherapy for unresectable advanced or metastatic malignant pleural mesothelioma. Available online: https://www.fda.gov/drugs/drug-approvals-and-databases/fda-approves-pembrolizumab-chemotherapy-unresectable-advanced-or-metastatic-malignant-pleural (accessed on 17 September 2024).

- Reck, M.; Rodríguez-Abreu, D.; Robinson, A.G.; Hui, R.; Csőszi, T.; Fülöp, A.; Gottfried, M.; Peled, N.; Tafreshi, A.; Cuffe, S.; et al. Pembrolizumab versus chemotherapy for PD-L1–positive non–small-cell lung cancer. N. Engl. J. Med.2016, 375, 1823–1833, . [CrossRef]

- Gandhi, L.; Rodríguez-Abreu, D.; Gadgeel, S.; Esteban, E.; Felip, E.; De Angelis, F.; Domine, M.; Clingan, P.; Hochmair, M.J.; Powell, S.F.; et al. Pembrolizumab plus chemotherapy in metastatic non–small-cell lung cancer. N. Engl. J. Med.2018, 378, 2078–2092, . [CrossRef]

- Hellmann, M.D.; Paz-Ares, L.; Bernabe Caro, R.; Zurawski, B.; Kim, S.W.; Carcereny, E.; Park, K.; Alexandru, A.; Lupinacci, L.; de la Mora Jimenez, E.; et al. Nivolumab plus ipilimumab in advanced non–small-cell lung cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 2019, 381, 2020–2031, . [CrossRef]

- Larkin, J.; Chiarion-Sileni, V.; Gonzalez, R.; Grob, J.J.; Cowey, C.L.; Lao, C.D.; Schadendorf, D.; Dummer, R.; Smylie, M.; Rutkowski, P.; et al. Combined nivolumab and ipilimumab or monotherapy in untreated melanoma. N. Engl. J. Med.2015, 373, 23–34, . [CrossRef]

- Motzer, R.J.; Tannir, N.M.; McDermott, D.F.; Arén Frontera, O.; Melichar, B.; Choueiri, T.K.; Plimack, E.R.; Barthélémy, P.; Porta, C.; George, S.; et al. Nivolumab plus ipilimumab versus sunitinib in advanced renal-cell carcinoma. N. Engl. J. Med. 2018, 378, 1277–1290, . [CrossRef]

- Socinski, M.A.; Jotte, R.M.; Cappuzzo, F.; Orlandi, F.; Stroyakovskiy, D.; Nogami, N.; Rodríguez-Abreu, D.; Moro-Sibilot, D.; Thomas, C.A.; Barlesi, F.; et al. Atezolizumab for first-line treatment of metastatic nonsquamous NSCLC. N. Engl. J. Med. 2018, 378, 2288–2301, . [CrossRef]

- Sun, J.M.; Shen, L.; Shah, M.A.; Enzinger, P.; Adenis, A.; Doi, T.; Kojima, T.; Metges, J.P.; Li, Z.; Kim, S.B.; et al. Pembrolizumab plus chemotherapy versus chemotherapy alone for first-line treatment of advanced esophageal cancer. Lancet 2021, 398, 759–771, . [CrossRef]

- Kelly, R.J.; Ajani, J.A.; Kuzdzal, J.; Zander, T.; Van Cutsem, E.; Piessen, G.; Van den Eynde, M.; Rivera, F.; Wyrwicz, L.; Schenker, M.; et al. Adjuvant nivolumab in resected esophageal or gastroesophageal junction cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 2021, 384, 1191–1203, . [CrossRef]

- Powles, T.; Park, S.H.; Voog, E.; Caserta, C.; Valderrama, B.P.; Gurney, H.; Ferrier, R.; Jiang, Z.; Houede, N.; Wainstein, A.J.A.; et al. Avelumab maintenance therapy for advanced or metastatic urothelial carcinoma. N. Engl. J. Med. 2020, 383, 1218–1230, . [CrossRef]

- Schmid, P.; Adams, S.; Rugo, H.S.; Schneeweiss, A.; Barrios, C.H.; Iwata, H.; Diéras, V.; Hegg, R.; Im, S.A.; Shaw Wright, G.; et al. Atezolizumab and nab-paclitaxel in advanced triple-negative breast cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 2018, 379, 2108–2121, . [CrossRef]

- Paz-Ares, L.; Spira, A.; Raben, D.; Planchard, D.; Cho, B.C.; Özgüroğlu, M.; Daniel, D.; Villegas, A.; Vicente, D.; Hui, R.; Murakami, S.; Spigel, D.; Senan, S.; Langer, C.J.; Perez, B.A.; Boothman, A.-M.; Broadhurst, H.; Wadsworth, C.; Dennis, P.A.; Antonia, S.J.; Faivre-Finn, C. Outcomes with Durvalumab by Tumour PD-L1 Expression in Unresectable, Stage III Non-Small-Cell Lung Cancer in the PACIFIC Trial. Ann. Oncol. 2020, 31, 798–806. [CrossRef]

- Guan, Y.; Cui, Y.; Gong, Y.; Liang, X.; Han, X.; Chen, Y.; Xie, H.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, B.; Ye, X.; Wang, J. Dissociated Response and Treatment Outcome with Immune Checkpoint Blockade in Advanced Cancer. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 32147. [CrossRef]

- Camelliti, S.; Le Noci, V.; Bianchi, F.; Moscheni, C.; Arnaboldi, F.; Gagliano, N.; Balsari, A.; Garassino, M.C.; Tagliabue, E.; Sfondrini, L.; Sommariva, M. Mechanisms of Hyperprogressive Disease after Immune Checkpoint Inhibitor Therapy: What We (Don't) Know. J. Exp. Clin. Cancer Res. 2020, 39, 236. [CrossRef]

- Martin-Romano, P.; Castanon, E.; Ammari, S.; Champiat, S.; Hollebecque, A.; Postel-Vinay, S.; Baldini, C.; Varga, A.; Michot, J.M.; Vuagnat, P.; Marabelle, A.; Soria, J.-C.; Ferté, C.; Massard, C. Evidence of Pseudoprogression in Patients Treated with PD1/PDL1 Antibodies across Tumor Types. Cancer Med. 2020, 9, 2643–2652. [CrossRef]

- Riera-Sala, R.F.; Ibarra-Morales, A.M.G.; Guzmán-Casta, J.; Medrano-Guzmán, R.; Dip-Borunda, A.K.; Martin-Aguilar, A.E.; Grajales-Álvarez, R.C.; Correa-Cano, R.; Elvira-Fabián, K.; Sánchez-Ríos, C.P.; Orzuna-Vázquez, A.O.; Rovelo-Lima, J.E.; Martínez-Barrera, L.M.; Rodríguez-Cid, J.R.; Alatorre-Alexander, J.A. Pseudoprogression and Hyperprogression Secondary to Immunotherapy in Lung Cancer. World Cancer Res. J. 2023, 10, e2660. [CrossRef]

- Adashek, J.J.; Kato, S.; Ferrara, R.; Lo Russo, G.; Kurzrock, R. Hyperprogression and Immune Checkpoint Inhibitors: Hype or Progress? Oncologist 2020, 25, 94–98. [CrossRef]

- Champiat, S.; Dercle, L.; Ammari, S.; Massard, C.; Hollebecque, A.; Postel-Vinay, S.; Chaput, N.; Eggermont, A.; Marabelle, A.; Soria, J.-C.; Ferté, C. Hyperprogressive Disease Is a New Pattern of Progression in Cancer Patients Treated by Anti-PD-1/PD-L1. Clin. Cancer Res. 2017, 23, 1920–1928. [CrossRef]

- Morad, G.; Helmink, B.A.; Sharma, P.; Wargo, J.A. Hallmarks of Response, Resistance, and Toxicity to Immune Checkpoint Blockade. Cell 2021, 184, 5309–5337. [CrossRef]

- Ferrara, R.; Mezquita, L.; Texier, M.; Lahmar, J.; Audigier-Valette, C.; Tessonnier, L.; Mazieres, J.; Zalcman, G.; Brosseau, S.; Le Moulec, S.; Leroy, L.; Duchemann, B.; Lefebvre, C.; Veillon, R.; Westeel, V.; Koscielny, S.; Champiat, S.; Ferté, C.; Planchard, D.; Remon, J.; Boucher, M.-E.; Gazzah, A.; Adam, J.; Bria, E.; Tortora, G.; Soria, J.-C.; Besse, B.; Caramella, C. Hyperprogressive Disease in Patients With Advanced Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer Treated With PD-1/PD-L1 Inhibitors or With Single-Agent Chemotherapy. JAMA Oncol. 2018, 4, 1543–1552. [CrossRef]

- Seymour, L.; Bogaerts, J.; Perrone, A.; Ford, R.; Schwartz, L.H.; Mandrekar, S.; Lin, N.U.; Litière, S.; Dancey, J.; Chen, A.; Hodi, F.S.; Therasse, P.; Hoekstra, O.S.; Shankar, L.K.; Wolchok, J.D.; Ballinger, M.; Caramella, C.; de Vries, E.G.E. iRECIST: Guidelines for response criteria for use in trials testing immunotherapeutics. Lancet Oncol. 2017, 18, e143–e152, . [CrossRef]

- Wahl, R.L.; Jacene, H.; Kasamon, Y.; Lodge, M.A. From RECIST to PERCIST: Evolving considerations for PET response criteria in solid tumors. J. Nucl. Med. 2009, 50, 122S–150S, . [CrossRef]

- Persigehl, T.; Lennartz, S.; Schwartz, L.H. iRECIST: How to do it. Cancer Imaging 2020, 20, 2, . [CrossRef]

- Ramon-Patino, J.L.; Schmid, S.; Lau, S.; Seymour, L.; Gaudreau, P.-O.; Li, J.J.N.; Bradbury, P.A.; Calvo, E. iRECIST and atypical patterns of response to immuno-oncology drugs. J. Immunother. Cancer 2022, 10, e004849. [CrossRef]

- Park, H.J.; Kim, K.W.; Pyo, J.; Suh, C.H.; Yoon, S.; Hatabu, H.; Nishino, M. Incidence of Pseudoprogression during Immune Checkpoint Inhibitor Therapy for Solid Tumors: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Radiology 2020, 297, 87–96. [CrossRef]

- Vogsen, M.; Harbo, F.; Jakobsen, N.M.; Nissen, H.J.; Dahlsgaard-Wallenius, S.E.; Gerke, O.; Jensen, J.D.; Asmussen, J.T.; Jylling, A.M.B.; Braad, P.-E.; Vach, W.; Ewertz, M.; Hildebrandt, M.G. Response Monitoring in Metastatic Breast Cancer: A Prospective Study Comparing 18F-FDG PET/CT with Conventional CT. J. Nucl. Med. 2023, 64, 355–361. [CrossRef]

- Engel, R.; Kudura, K.; Antwi, K.; Denhaerynck, K.; Steinemann, D.; Wullschleger, S.; Müller, B.; Bolli, M.; von Strauss und Torney, M. Diagnostic Accuracy and Treatment Benefit of PET/CT in Staging of Colorectal Cancer Compared to Conventional Imaging. Surg. Oncol. 2024, 57, 102151. [CrossRef]

- Niikura, N.; Costelloe, C.M.; Madewell, J.E.; Hayashi, N.; Yu, T.-K.; Liu, J.; Palla, S.L.; Tokuda, Y.; Theriault, R.L.; Hortobagyi, G.N.; Ueno, N.T. FDG-PET/CT Compared with Conventional Imaging in the Detection of Distant Metastases of Primary Breast Cancer. Oncologist 2011, 16, 1111–1119. [CrossRef]

- Parihar, A.S.; Wahl, R. Immune-Related Adverse Events on 18F-FDG PET/CT in Patients Undergoing Immune Checkpoint Inhibitor Therapy. J. Nucl. Med. 2022, 63 (Supplement 2), 2720. https://jnm.snmjournals.org/content/63/supplement_2/2720.

- Kostakoglu, L.; Fardanesh, R.; Posner, M.; Som, P.; Rao, S.; Park, E.; Doucette, J.; Stein, E.; Gupta, V.; Misiukiewicz, K.; Genden, E. Early Detection of Recurrent Disease by FDG-PET/CT Leads to Management Changes in Patients With Squamous Cell Cancer of the Head and Neck. Clin. Nucl. Med. 2013, 38, e130–e135. [CrossRef]

- Tatar, G.; Alçin, G.; Samanci, N.S.; Fenercioglu, Ö.E.; Beyhan, E.; Cermik, T.F. Diagnostic Impact of 18F-FDG PET/CT Imaging on the Detection of Immune-Related Adverse Events in Patients Treated with Immunotherapy. Clin. Transl. Oncol. 2022, 24, 1741–1749. [CrossRef]

- Karlsen, W.; Akily, L.; Mierzejewska, M.; Teodorczyk, J.; Bandura, A.; Zaucha, R.; Cytawa, W. Is 18F-FDG-PET/CT an Optimal Imaging Modality for Detecting Immune-Related Adverse Events after Immune-Checkpoint Inhibitor Therapy? Pros and Cons. Cancers 2024, 16, 1990. [CrossRef]

- Beer, L.; Hochmair, M.; Haug, A.R.; Schwabel, B.; Kifjak, D.; Wadsak, W.; Fuereder, T.; Fabikan, H.; Fazekas, A.; Schwab, S.; Mayerhoefer, M.E.; Herold, C.; Prosch, H. Comparison of RECIST, iRECIST, and PERCIST for the Evaluation of Response to PD-1/PD-L1 Blockade Therapy in Patients With Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer. Clin. Nucl. Med. 2019, 44, 535–543. [CrossRef]

- Goldfarb, L.; Duchemann, B.; Chouahnia, K.; Zelek, L.; Soussan, M. Monitoring Anti-PD-1-Based Immunotherapy in Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer with FDG PET: Introduction of iPERCIST. EJNMMI Res. 2019, 9, 8. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).