Submitted:

06 April 2025

Posted:

08 April 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Results

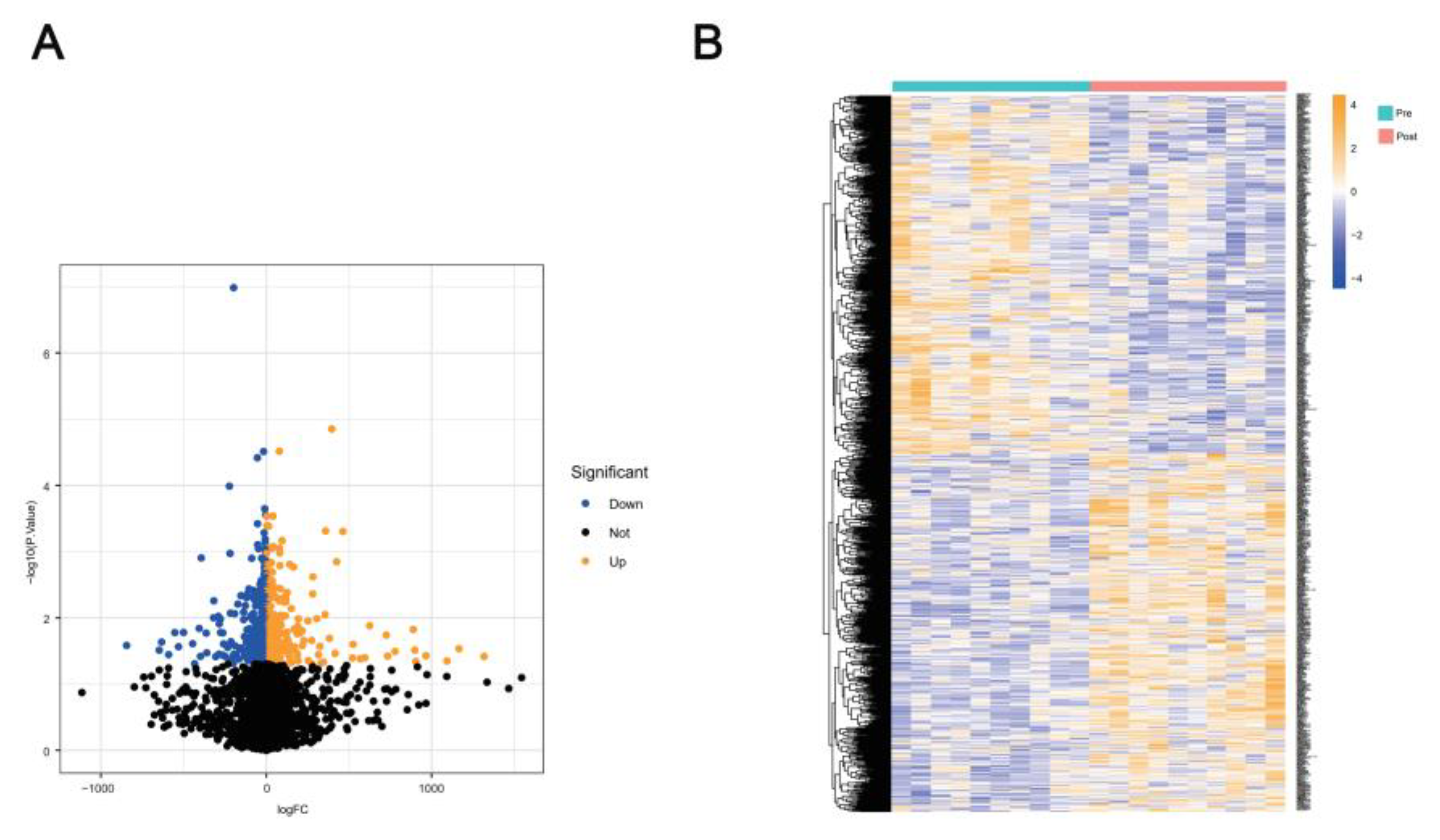

2.1. Differential Analysis of GSE44777 Between Yoga Pre- and Post-Intervention

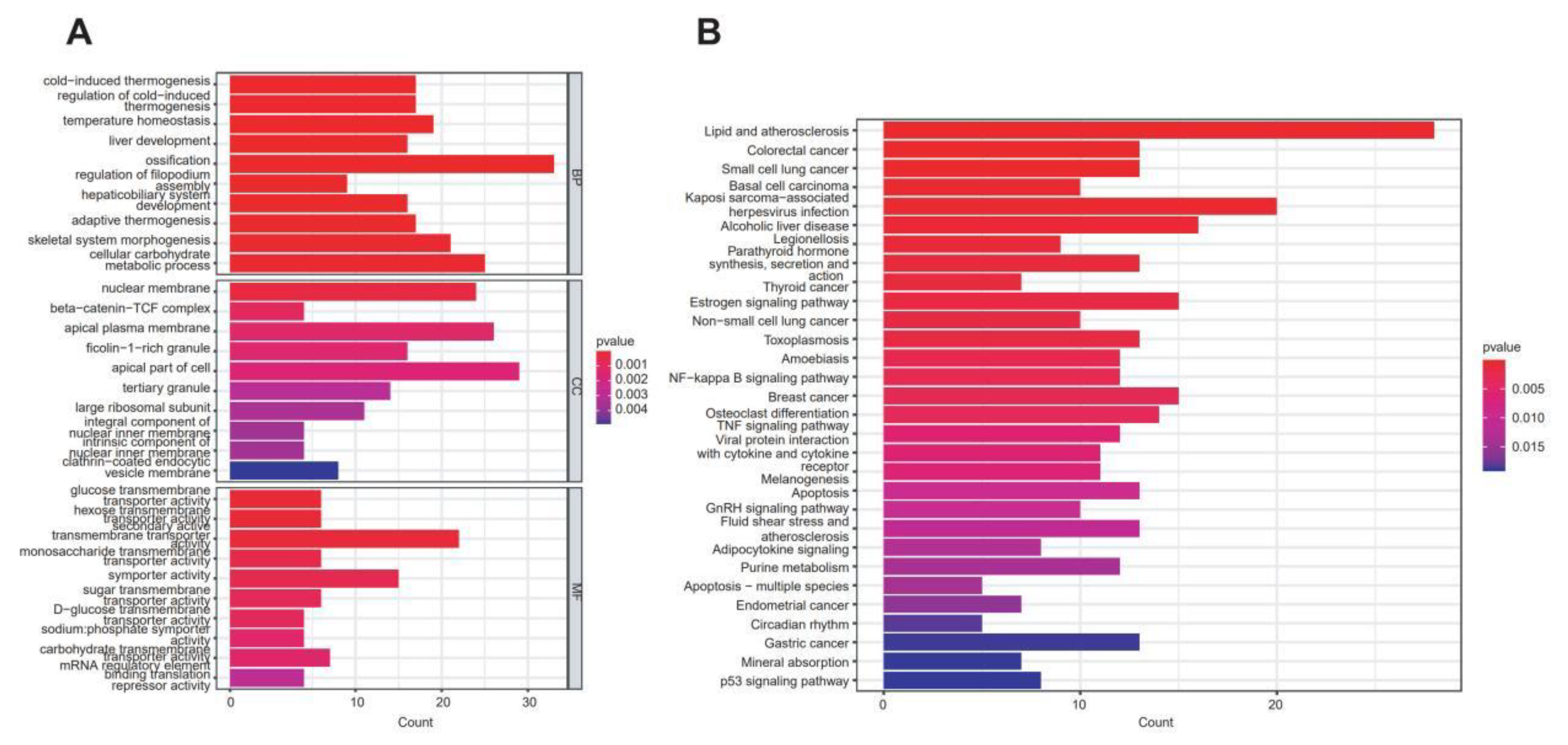

2.2. Differential Gene Functional Enrichment Analysis Results

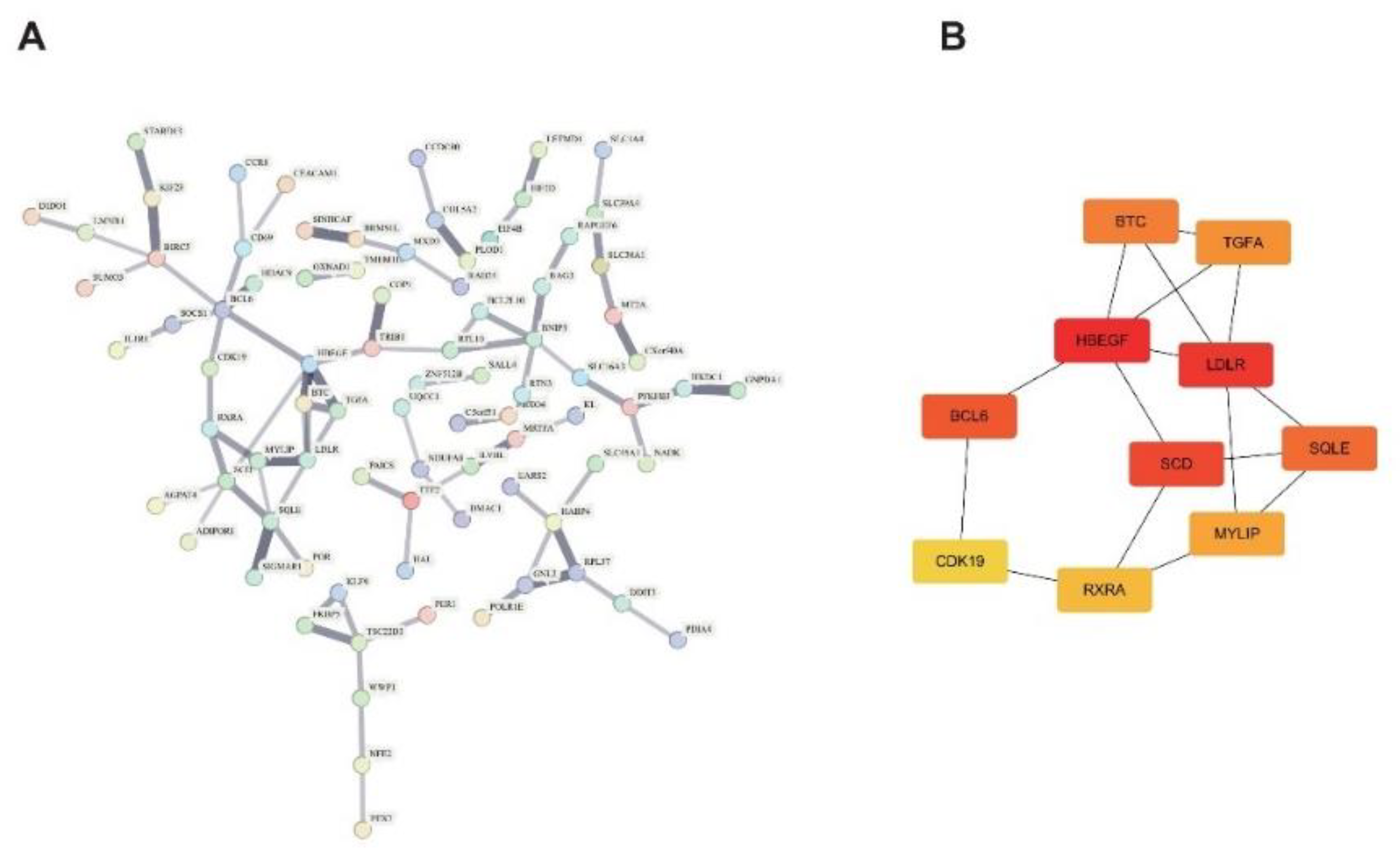

2.3. Signature Gene PPI Network Analysis

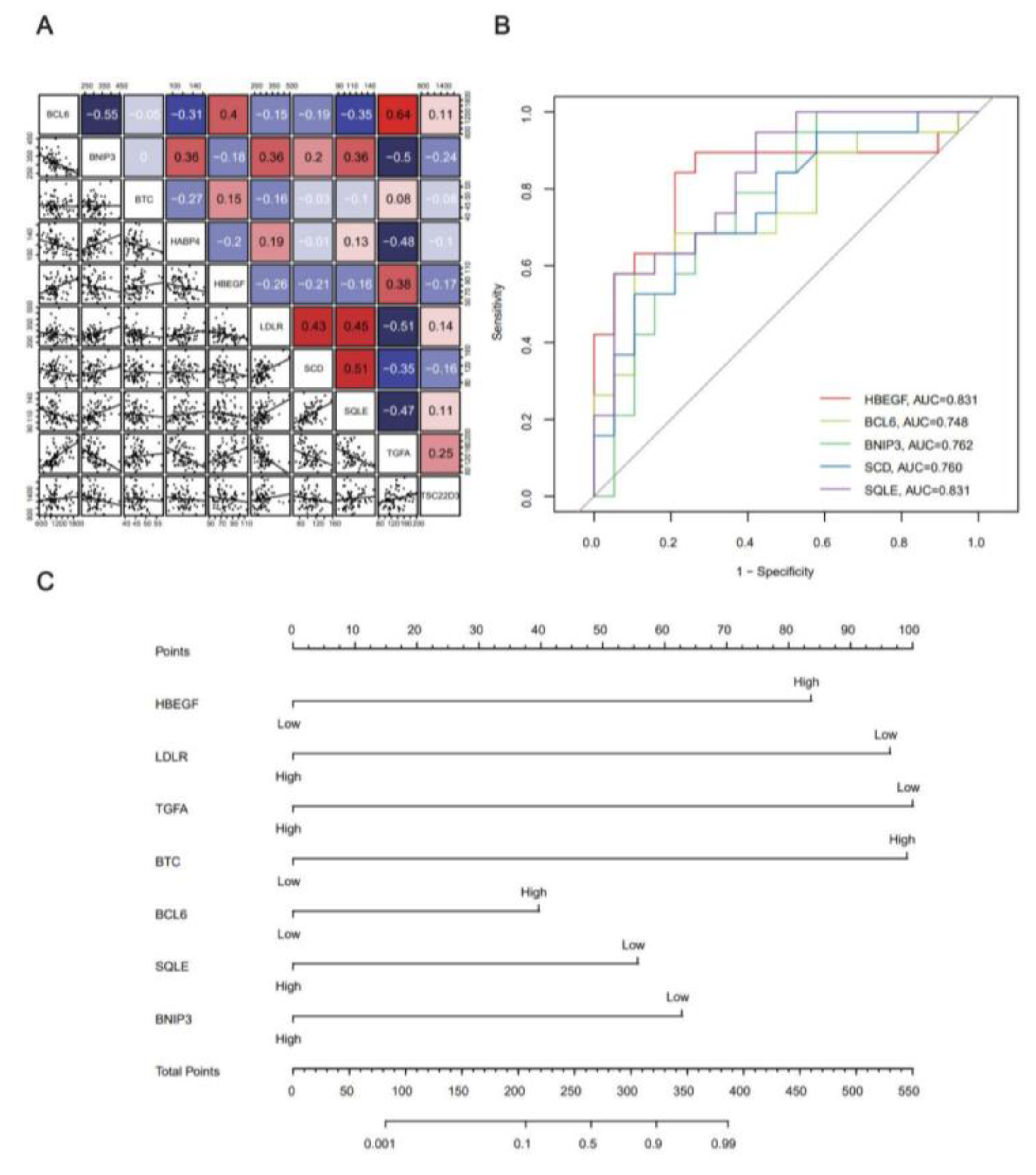

2.4. Co-Expression Analysis of Key Genes in Yoga and Construction of Risk Prediction Line Graph Model

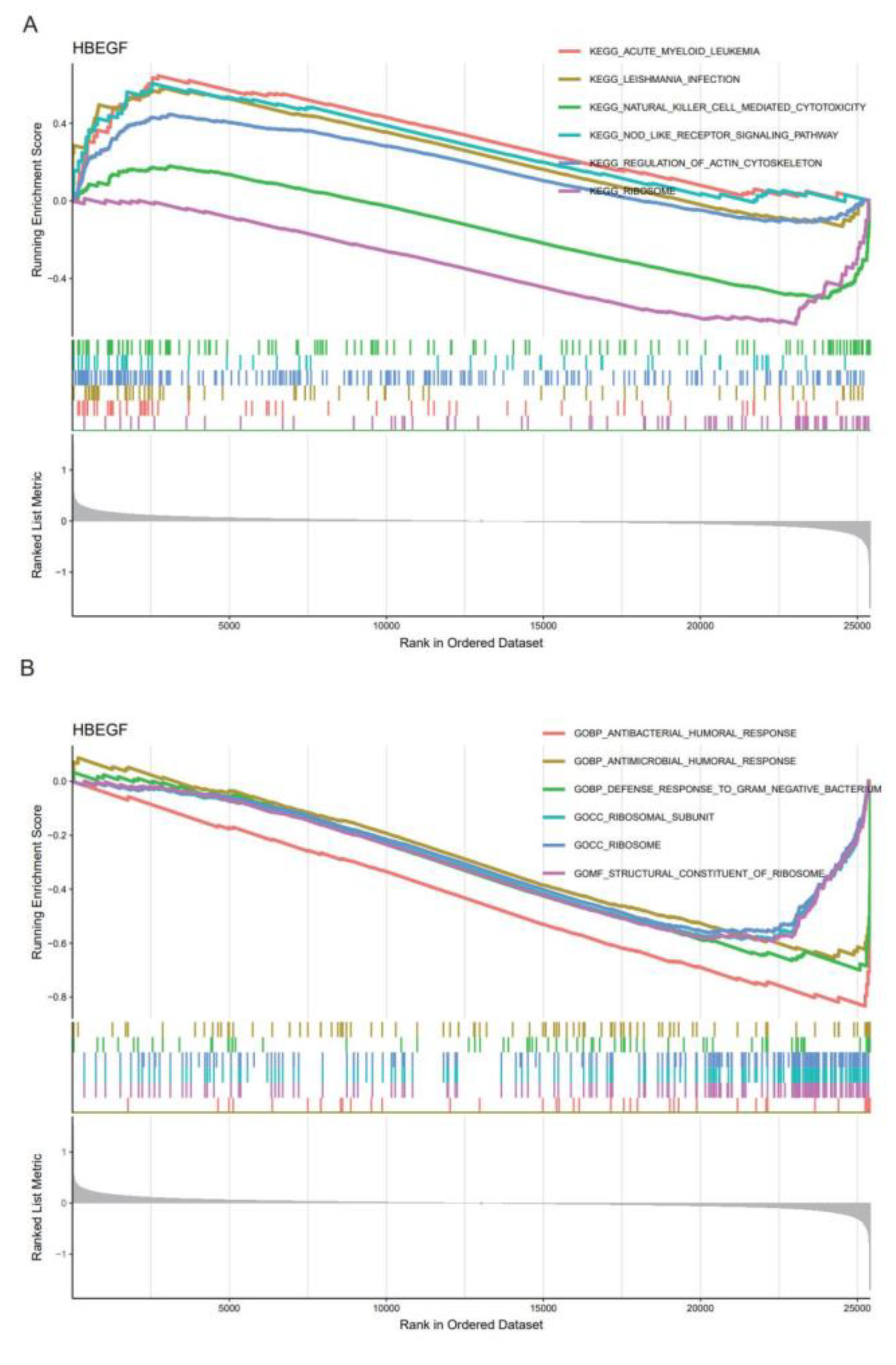

2.5. Gene Set Enrichment Analysis (GSEA) for Core Genes

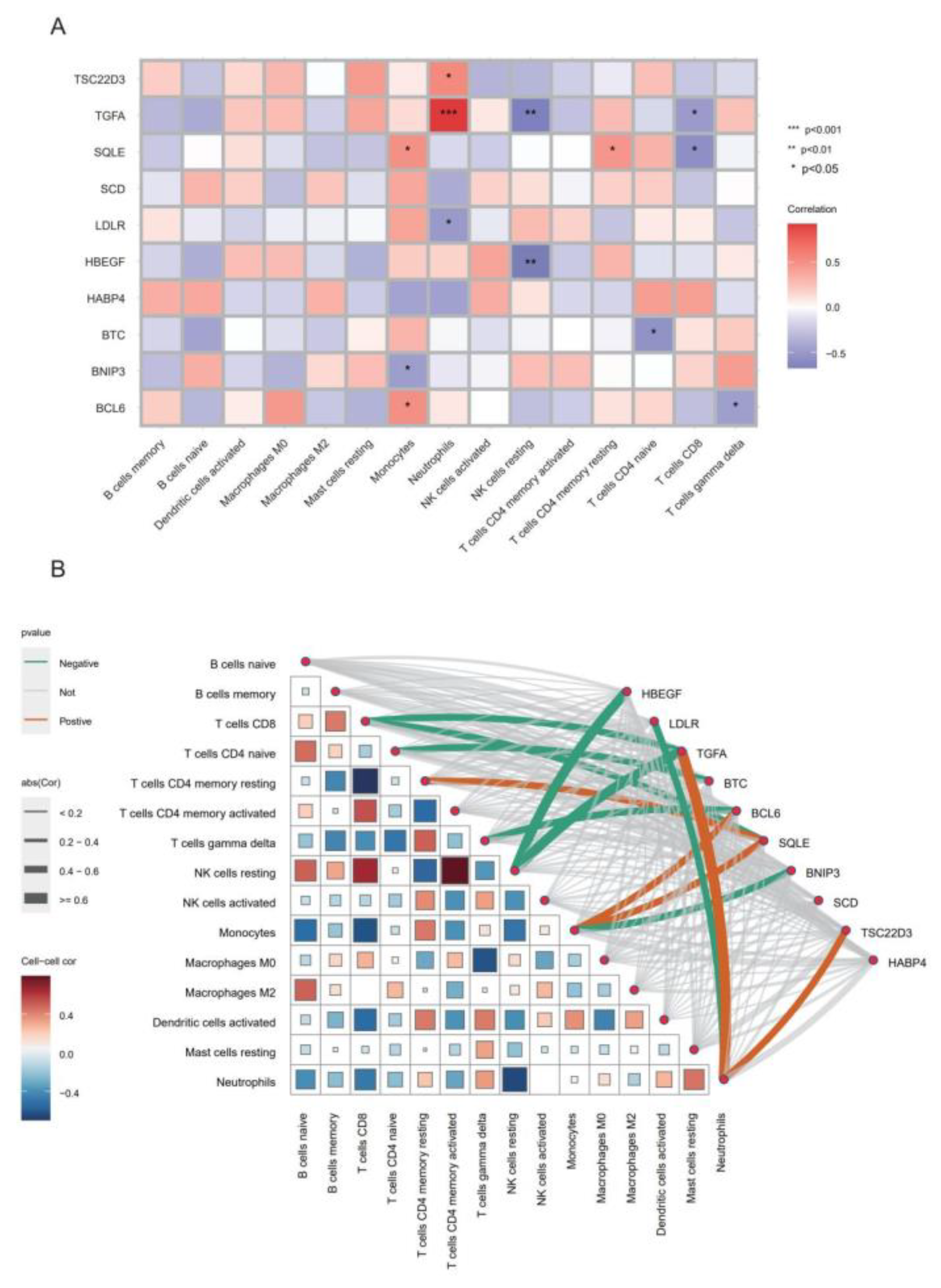

2.6. Yoga Immunomodulation Results

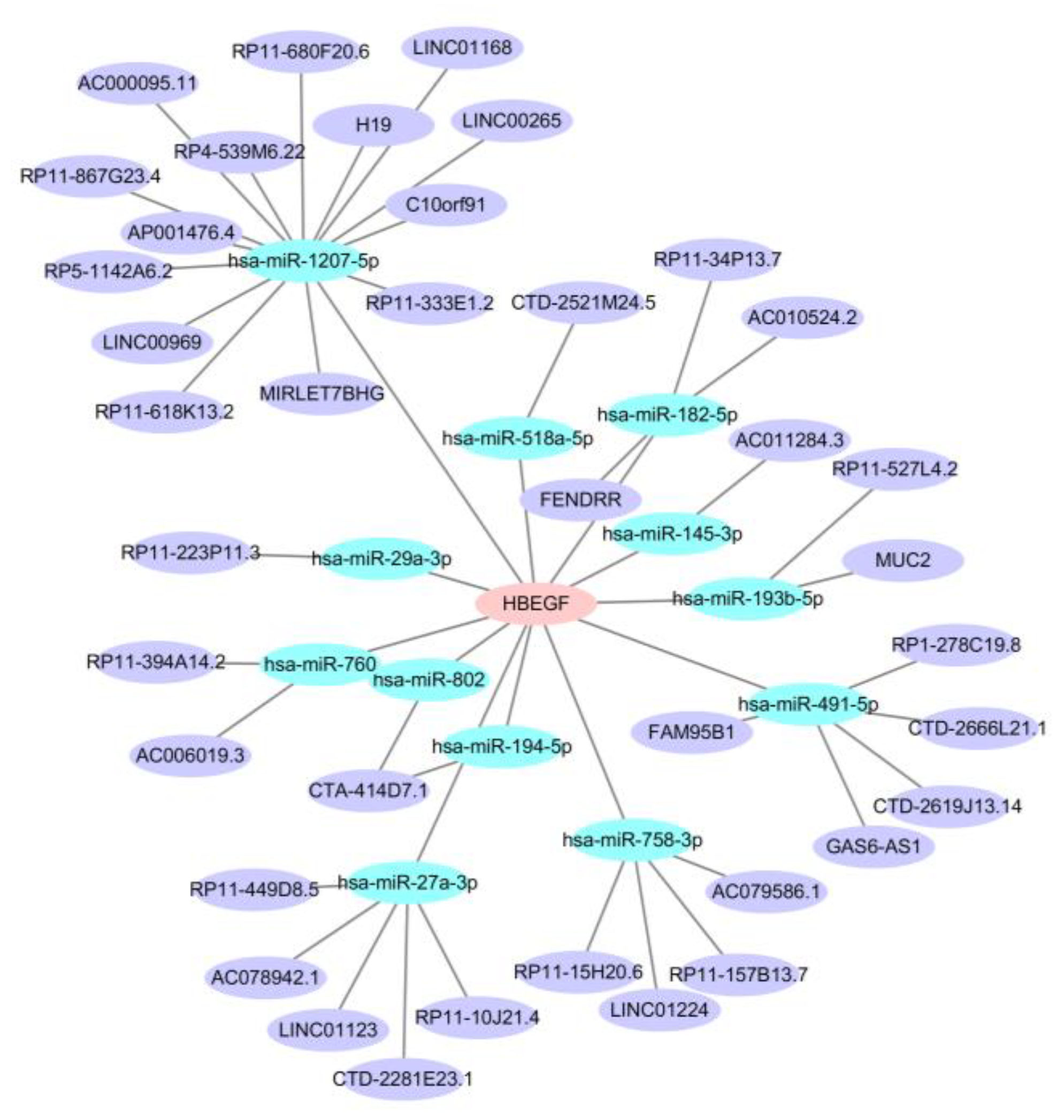

2.8. Construction of mRNA-miRNA-lncRNA ceRNA Network

3. Discussion

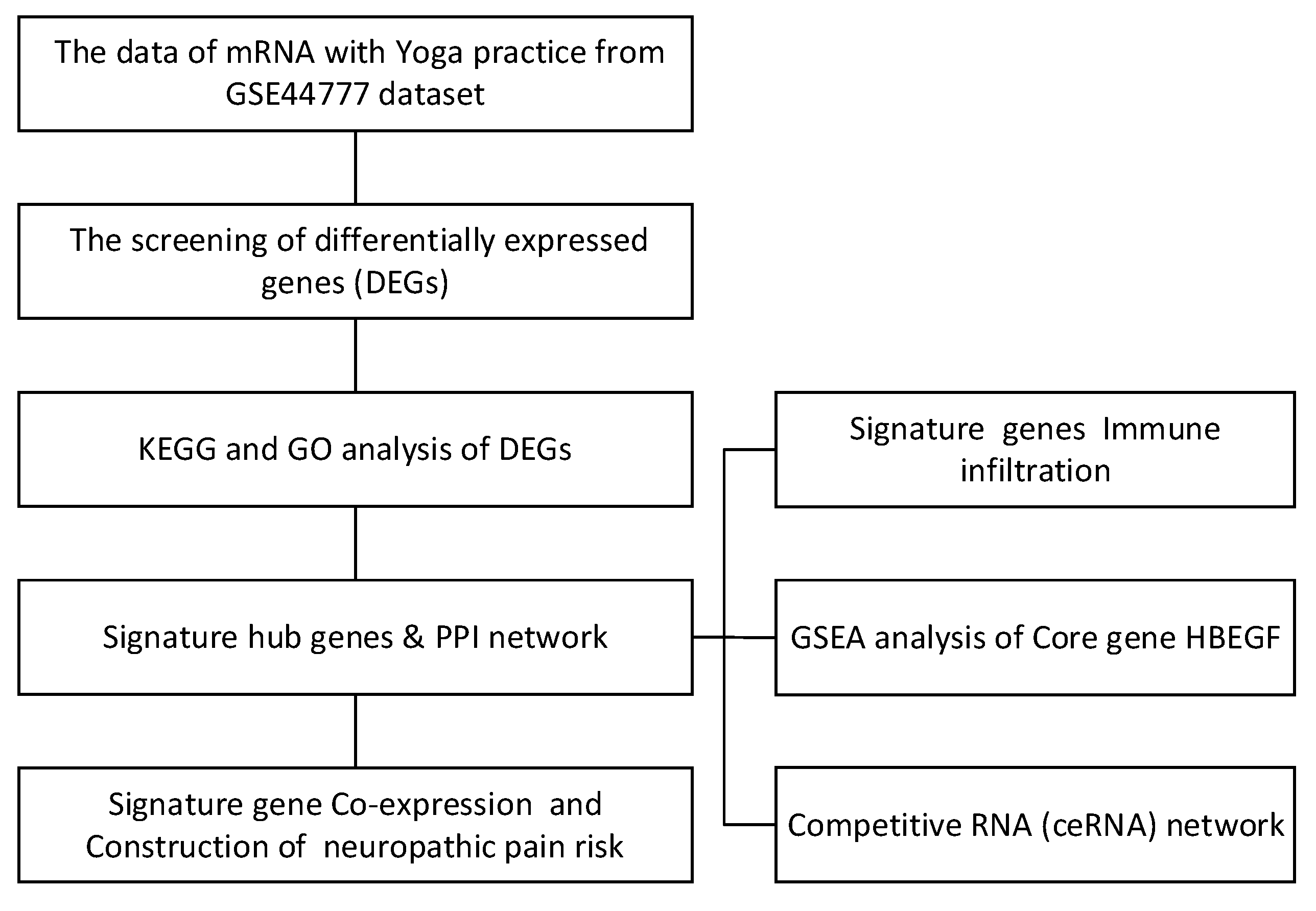

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Acquisition of Yoga Data

4.2. Identification of DEGs

4.3. Differential Gene GO/KEGG Enrichment Analysis

4.4. Hub Gene Selection via the PPI Network

4.5. Construction of Nomograph Models

4.6. Gene Set Enrichment Analysis

4.7. Immune Infiltration Analysis

4.8. Competitive RNA (ceRNA) Network Construction

4.9. Statistical Analysis

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| DEGs | Differentially expressed genes |

| PPI | Protein-protein interaction |

| ceRNA | Competitive endogenous RNA |

| GEO | Gene Expression Omnibus |

| KEGG | Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes |

| GO | Gene Ontology |

| ROC | Receiver operating characteristic |

| PBMCs | Peripheral blood mononuclear cells |

| GSEA | Gene Set Enrichment Analysis |

| lncRNAs | Long non-coding RNAs |

| HPA | Hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis |

| CRP | C-reactive protein |

| IL | Interleukin |

| TNF | Tumor necrosis factor |

References

- Sharma, H.; Swetanshu; Singh, P. Role of Yoga in Cardiovascular Diseases. Curr. Probl. Cardiol. 2024, 49, 102032. [CrossRef]

- Nourollahimoghadam, E.; Gorji, S.; Gorji, A.; Khaleghi, G.M. Therapeutic role of yoga in neuropsychological disorders. World J. Psychiatry 2021, 11, 754–773. [CrossRef]

- Voss, S.; Cerna, J.; Gothe, N.P. Yoga Impacts Cognitive Health: Neurophysiological Changes and Stress Regulation Mechanisms. Exerc. Sport Sci. Rev. 2023, 51, 73–81. [CrossRef]

- Yeun, Y.R.; Kim, S.D. Effects of yoga on immune function: A systematic review of randomized controlled trials. Complement. Ther. Clin. 2021, 44, 101446. [CrossRef]

- Kwok, J.; Chan, L.; Lai, C.A.; Ho, P.; Choi, Z.Y.; Auyeung, M.; Pang, S.; Choi, E.; Fong, D.; Yu, D.; et al. Effects of Meditation and Yoga on Anxiety, Depression and Chronic Inflammation in Patients with Parkinson’s Disease: A Randomized Clinical Trial. Psychother. Psychosom. 2025, 1–18. [CrossRef]

- Estevao, C. The role of yoga in inflammatory markers. Brain Behav. Immun. Health 2022, 20, 100421. [CrossRef]

- Nagarathna, R.; Kumar, S.; Anand, A.; Acharya, I.N.; Singh, A.K.; Patil, S.S.; Latha, R.H.; Datey, P.; Nagendra, H.R. Effectiveness of Yoga Lifestyle on Lipid Metabolism in a Vulnerable Population-A Community Based Multicenter Randomized Controlled Trial. Medicines 2021, 8, 7. [CrossRef]

- Loewenthal, J.; Innes, K.E.; Mitzner, M.; Mita, C.; Orkaby, A.R. Effect of Yoga on Frailty in Older Adults: A Systematic Review. Ann. Intern. Med. 2023, 176, 524–535. [CrossRef]

- Cahn, B.R.; Goodman, M.S.; Peterson, C.T.; Maturi, R.; Mills, P.J. Yoga, Meditation and Mind-Body Health: Increased BDNF, Cortisol Awakening Response, and Altered Inflammatory Marker Expression after a 3-Month Yoga and Meditation Retreat. Front. Hum. Neurosci. 2017, 11, 315. [CrossRef]

- Simon, N.M.; Hofmann, S.G.; Rosenfield, D.; Hoeppner, S.S.; Hoge, E.A.; Bui, E.; Khalsa, S. Efficacy of Yoga vs Cognitive Behavioral Therapy vs Stress Education for the Treatment of Generalized Anxiety Disorder: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Psychiatry 2021, 78, 13–20. [CrossRef]

- Kaushik, D.; Shah, P.K.; Mukherjee, N.; Ji, N.; Dursun, F.; Kumar, A.P.; Thompson, I.J.; Mansour, A.M.; Jha, R.; Yang, X.; et al. Effects of yoga in men with prostate cancer on quality of life and immune response: a pilot randomized controlled trial. Prostate Cancer Prostatic Dis. 2022, 25, 531–538. [CrossRef]

- Harkess, K.N.; Ryan, J.; Delfabbro, P.H.; Cohen-Woods, S. Preliminary indications of the effect of a brief yoga intervention on markers of inflammation and DNA methylation in chronically stressed women. Transl. Psychiatry 2016, 6, e965. [CrossRef]

- Qu, S.; Olafsrud, S.M.; Meza-Zepeda, L.A.; Saatcioglu, F. Rapid gene expression changes in peripheral blood lymphocytes upon practice of a comprehensive yoga program. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e61910. [CrossRef]

- Khokhar, M.; Tomo, S.; Gadwal, A.; Purohit, P. Multi-omics integration and interactomics reveals molecular networks and regulators of the beneficial effect of yoga and exercise. Int. J. Yoga 2022, 15, 25–39. [CrossRef]

- Ritchie, M.E.; Phipson, B.; Wu, D.; Hu, Y.; Law, C.W.; Shi, W.; Smyth, G.K. limma powers differential expression analyses for RNA-sequencing and microarray studies. Nucleic Acids Res. 2015, 43, e47. [CrossRef]

- Sun, J.; Zhao, J.; Jiang, F.; Wang, L.; Xiao, Q.; Han, F.; Chen, J.; Yuan, S.; Wei, J.; Larsson, S.C.; et al. Identification of novel protein biomarkers and drug targets for colorectal cancer by integrating human plasma proteome with genome. Genome Med. 2023, 15, 75. [CrossRef]

- Subramanian, A.; Tamayo, P.; Mootha, V.K.; Mukherjee, S.; Ebert, B.L.; Gillette, M.A.; Paulovich, A.; Pomeroy, S.L.; Golub, T.R.; Lander, E.S.; et al. Gene set enrichment analysis: a knowledge-based approach for interpreting genome-wide expression profiles. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2005, 102, 15545–15550. [CrossRef]

- Newman, A.M.; Liu, C.L.; Green, M.R.; Gentles, A.J.; Feng, W.; Xu, Y.; Hoang, C.D.; Diehn, M.; Alizadeh, A.A. Robust enumeration of cell subsets from tissue expression profiles. Nat. Methods 2015, 12, 453–457. [CrossRef]

- Mao, M.; Zhang, J.; Xiang, Y.; Gong, M.; Deng, Y.; Ye, D. Role of exosomal competitive endogenous RNA (ceRNA) in diagnosis and treatment of malignant tumors. Bioengineered 2022, 13, 12156–12168. [CrossRef]

- Alfaddagh, A.; Martin, S.S.; Leucker, T.M.; Michos, E.D.; Blaha, M.J.; Lowenstein, C.J.; Jones, S.R.; Toth, P.P. Inflammation and cardiovascular disease: From mechanisms to therapeutics. Am. J. Prev. Cardiol. 2020, 4, 100130. [CrossRef]

- Tan, A.; Thomas, R.L.; Campbell, M.D.; Prior, S.L.; Bracken, R.M.; Churm, R. Effects of exercise training on metabolic syndrome risk factors in post-menopausal women - A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. Clin. Nutr. 2023, 42, 337–351. [CrossRef]

- Patil, S.G.; Sobitharaj, E.C.; Chandrasekaran, A.M.; Patil, S.S.; Singh, K.; Gupta, R.; Deepak, K.K.; Jaryal, A.K.; Chandran, D.S.; Kinra, S.; et al. Effect of Yoga-Based Cardiac Rehabilitation Program on Endothelial Function, Oxidative Stress, and Inflammatory Markers in Acute Myocardial Infarction: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Int. J. Yoga 2024, 17, 20–28. [CrossRef]

- Sarvottam, K.; Magan, D.; Yadav, R.K.; Mehta, N.; Mahapatra, S.C. Adiponectin, interleukin-6, and cardiovascular disease risk factors are modified by a short-term yoga-based lifestyle intervention in overweight and obese men. J. Altern. Complement. Med. 2013, 19, 397–402. [CrossRef]

- Kaliman, P.; Alvarez-Lopez, M.J.; Cosin-Tomas, M.; Rosenkranz, M.A.; Lutz, A.; Davidson, R.J. Rapid changes in histone deacetylases and inflammatory gene expression in expert meditators. Psychoneuroendocrinology 2014, 40, 96–107. [CrossRef]

- Bishop, J.R.; Lee, A.M.; Mills, L.J.; Thuras, P.D.; Eum, S.; Clancy, D.; Erbes, C.R.; Polusny, M.A.; Lamberty, G.J.; Lim, K.O. Corrigendum: Methylation of FKBP5 and SLC6A4 in Relation to Treatment Response to Mindfulness Based Stress Reduction for Posttraumatic Stress Disorder. Front. Psychiatry 2021, 12, 642245. [CrossRef]

- Chaix, R.; Fagny, M.; Cosin-Tomas, M.; Alvarez-Lopez, M.; Lemee, L.; Regnault, B.; Davidson, R.J.; Lutz, A.; Kaliman, P. Differential DNA methylation in experienced meditators after an intensive day of mindfulness-based practice: Implications for immune-related pathways. Brain Behav. Immun. 2020, 84, 36–44. [CrossRef]

- Verzili, B.; Valerio, D.A.M.; Herrmann, F.; Reyes, M.B.; Galduroz, R.F. A systematic review with meta-analysis of Yoga’s contributions to neuropsychiatric aspects of aging. Behav. Brain Res. 2023, 454, 114636. [CrossRef]

- Gautam, S.; Kumar, R.; Kumar, U.; Kumar, S.; Luthra, K.; Dada, R. Yoga maintains Th17/Treg cell homeostasis and reduces the rate of T cell aging in rheumatoid arthritis: a randomized controlled trial. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 14924. [CrossRef]

- R, P.; Kumar, A.P.; Dhamodhini, K.S.; Venugopal, V.; Silambanan, S.; K, M.; Shah, P. Role of yoga in stress management and implications in major depression disorder. J. Ayurveda Integr. Med. 2023, 14, 100767. [CrossRef]

- Greaney, S.K.; Amin, N.; Prudner, B.C.; Compernolle, M.; Sandell, L.J.; Tebb, S.C.; Weilbaecher, K.N.; Abeln, P.; Luo, J.; Tao, Y.; et al. Yoga Therapy During Chemotherapy for Early-Stage and Locally Advanced Breast Cancer. Integr. Cancer Ther. 2022, 21, 1553452421. [CrossRef]

- Kwon, R.; Kasper, K.; London, S.; Haas, D.M. A systematic review: The effects of yoga on pregnancy. Eur. J. Obstet. Gynecol. Reprod. Biol. 2020, 250, 171–177. [CrossRef]

- Shidhaye, R.; Bangal, V.; Bhargav, H.; Tilekar, S.; Thanage, C.; Gore, S.; Doifode, A.; Thete, U.; Game, K.; Hake, V.; et al. Feasibility, acceptability, and preliminary efficacy of yoga to improve maternal mental health and immune function during the COVID-19 crisis (Yoga-M (2) trial): a pilot randomized controlled trial. Front. Hum. Neurosci. 2023, 17, 1115699. [CrossRef]

- Vollbehr, N.K.; Stant, A.D.; Hoenders, H.; Bartels-Velthuis, A.A.; Nauta, M.H.; Castelein, S.; Schroevers, M.J.; de Jong, P.J.; Ostafin, B.D. Cost-effectiveness of a mindful yoga intervention added to treatment as usual for young women with major depressive disorder versus treatment as usual only: Cost-effectiveness of yoga for young women with depression. Psychiatry Res. 2024, 333, 115692. [CrossRef]

- Nalbant, G.; Lewis, S.; Chattopadhyay, K. Characteristics of Yoga Providers and Their Sessions and Attendees in the UK: A Cross-Sectional Survey. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 4. [CrossRef]

- Lachance, C.C.; McCormack, S. Mindfulness Training and Yoga for the Management of Chronic Non-malignant Pain: A Review of Clinical Effectiveness and Cost-effectiveness. Canadian Agency for Drugs and Technologies in Health: Ottawa, ON, Canada, 2019.

- Nagarhalli, M. Yoga for the primary prevention of cardiovascular disease: Summary of a Cochrane review. Explore 2021, 17, 96. [CrossRef]

- Bennetts, A. How does yoga practice and therapy yield psychological benefits? A review and model of transdiagnostic processes. Complement. Ther. Clin. 2022, 46, 101514. [CrossRef]

- Anheyer, D.; Haller, H.; Lauche, R.; Dobos, G.; Cramer, H. Yoga for treating low back pain: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Pain 2022, 163, e504–e517. [CrossRef]

- Mooventhan, A.; Nivethitha, L. Role of yoga in the prevention and management of various cardiovascular diseases and their risk factors: A comprehensive scientific evidence-based review. Explore 2020, 16, 257–263. [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).