Submitted:

19 April 2025

Posted:

21 April 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Geological Setting and Study Area

3. Field Relationship and Petrography

3.1. Trachy Basalt

3.2. Alkali Basalt

3.3. Basanite

4. Analytical Technique

4.1. Whole Rock

4.2. Electron Probe Micro-Analyzer (EPMA)

4.3. Test for Equilibrium in Mineral-Liquid Geothermobarometry

4.4. Programs to Calculate Temperature and Pressure

5. Results

5.1. Whole Rock Composition

5.2. Mineral Chemistry

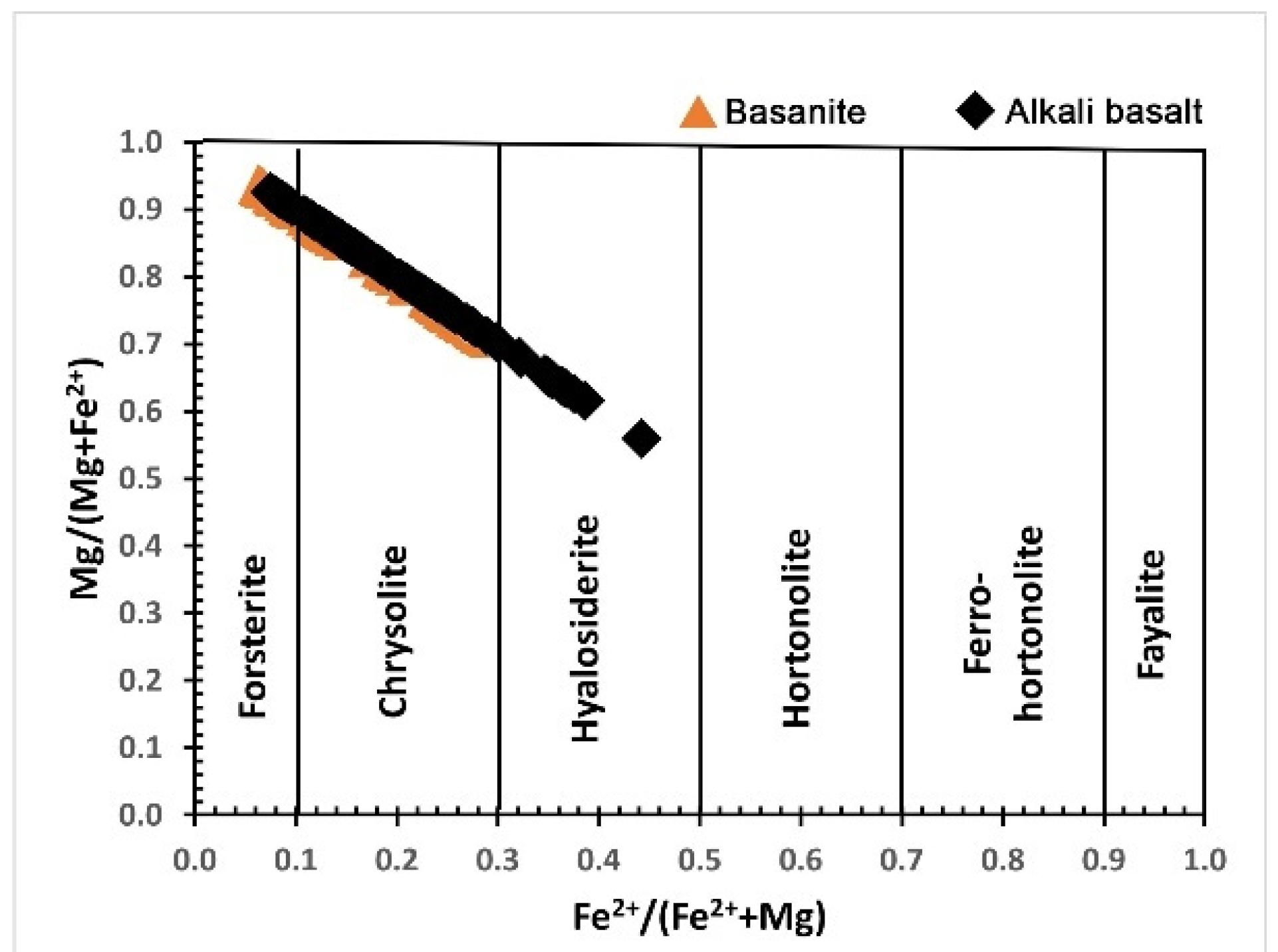

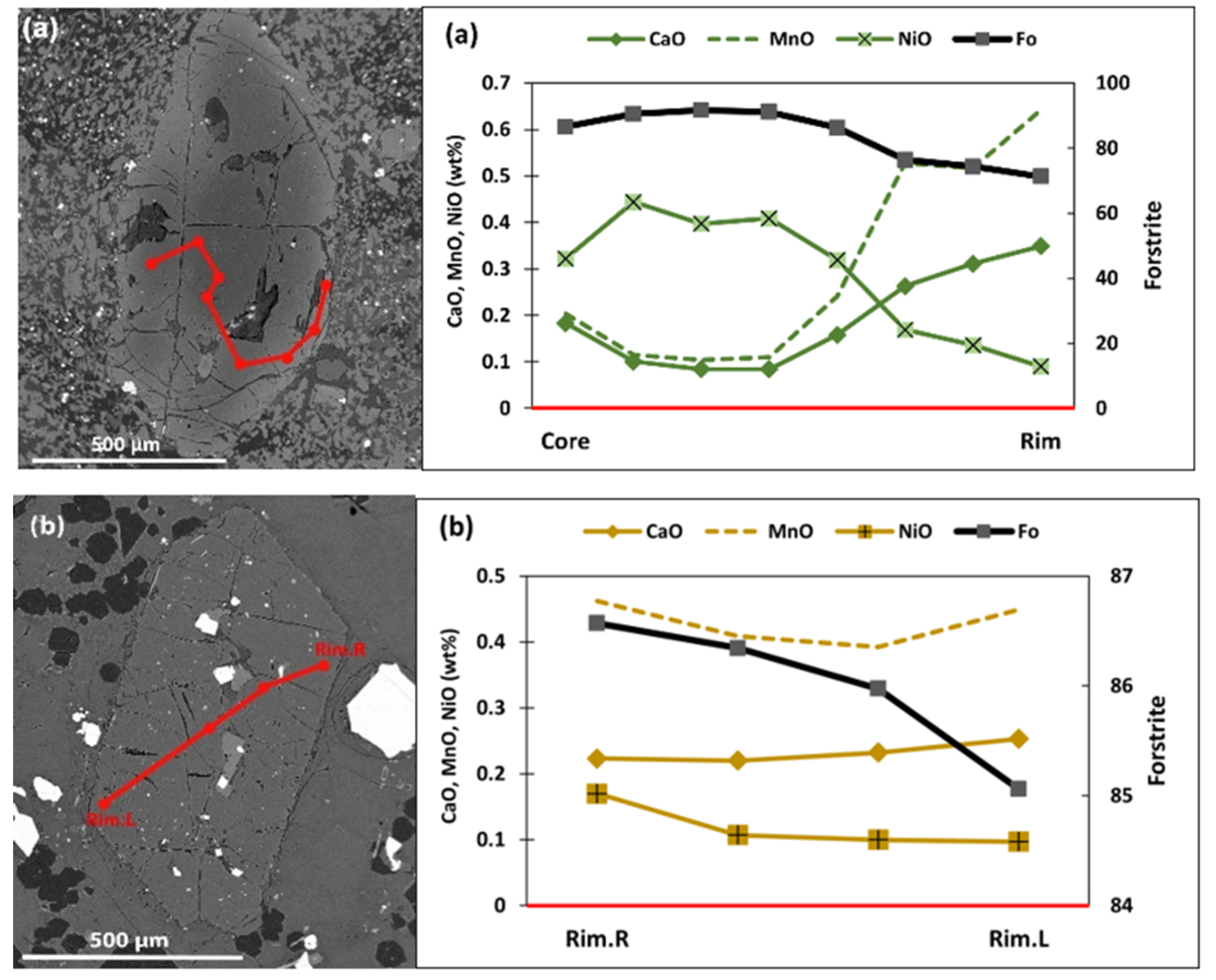

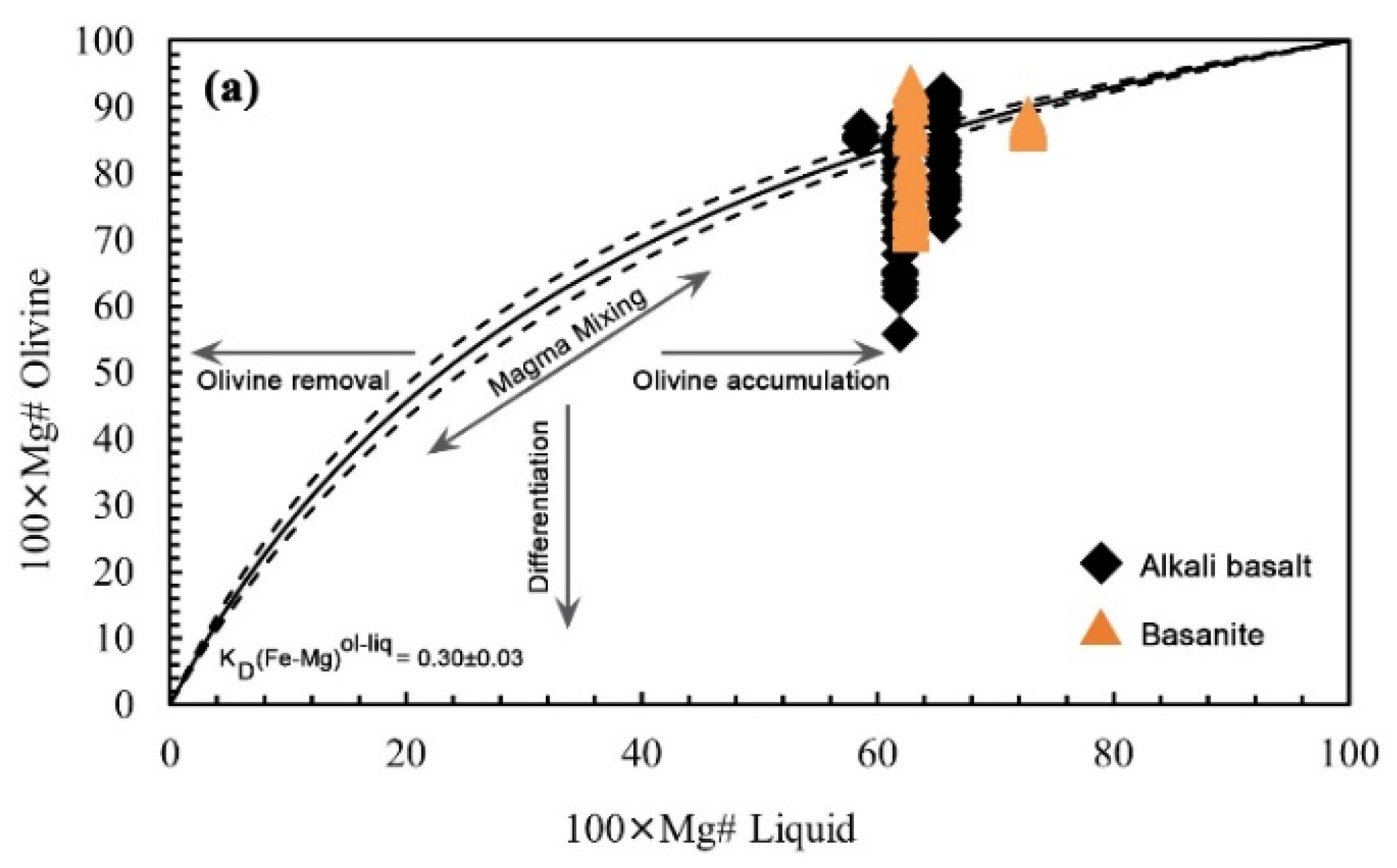

5.2.1. Olivine

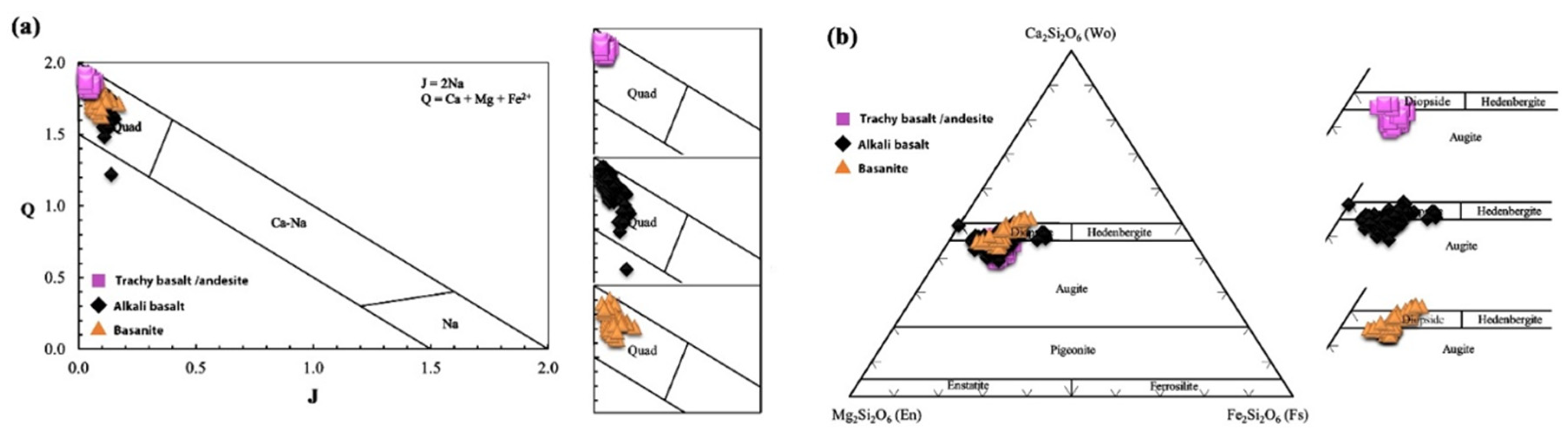

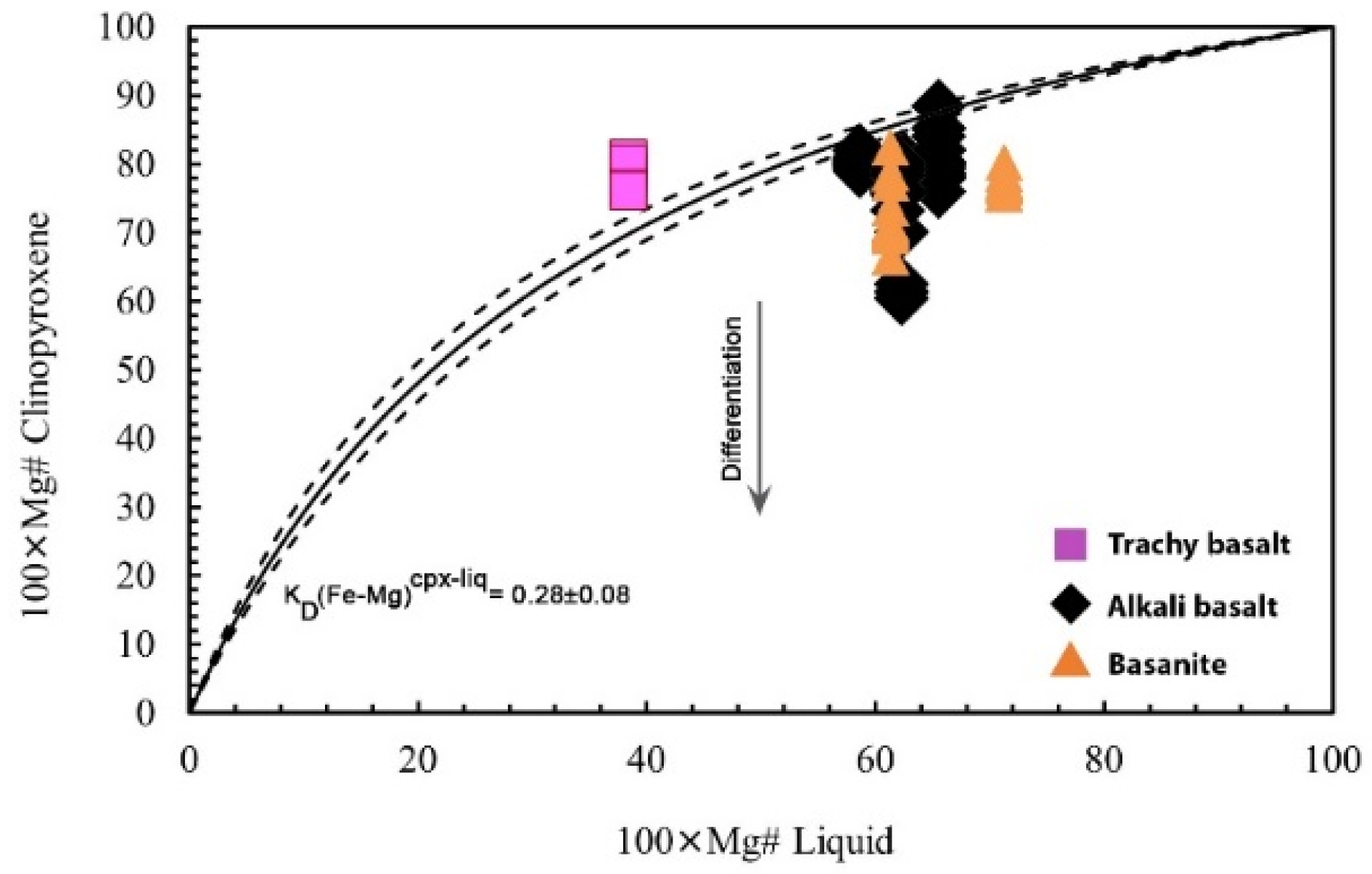

5.2.2. Clinopyroxene

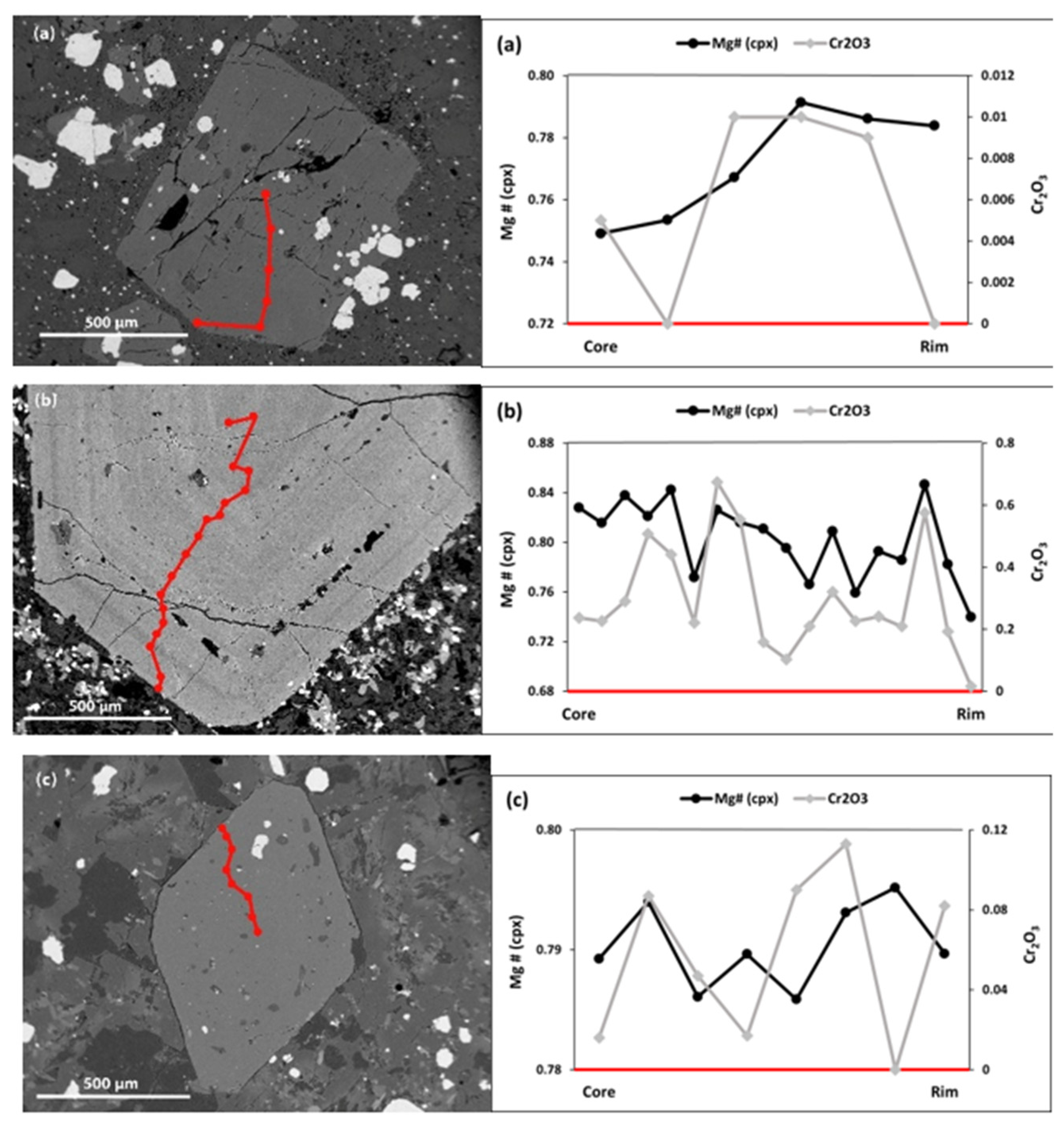

- Cpx Mega-phenocrysts

- Cpx Phenocrysts

- Cpx Micro-phenocrysts

6. Discussion

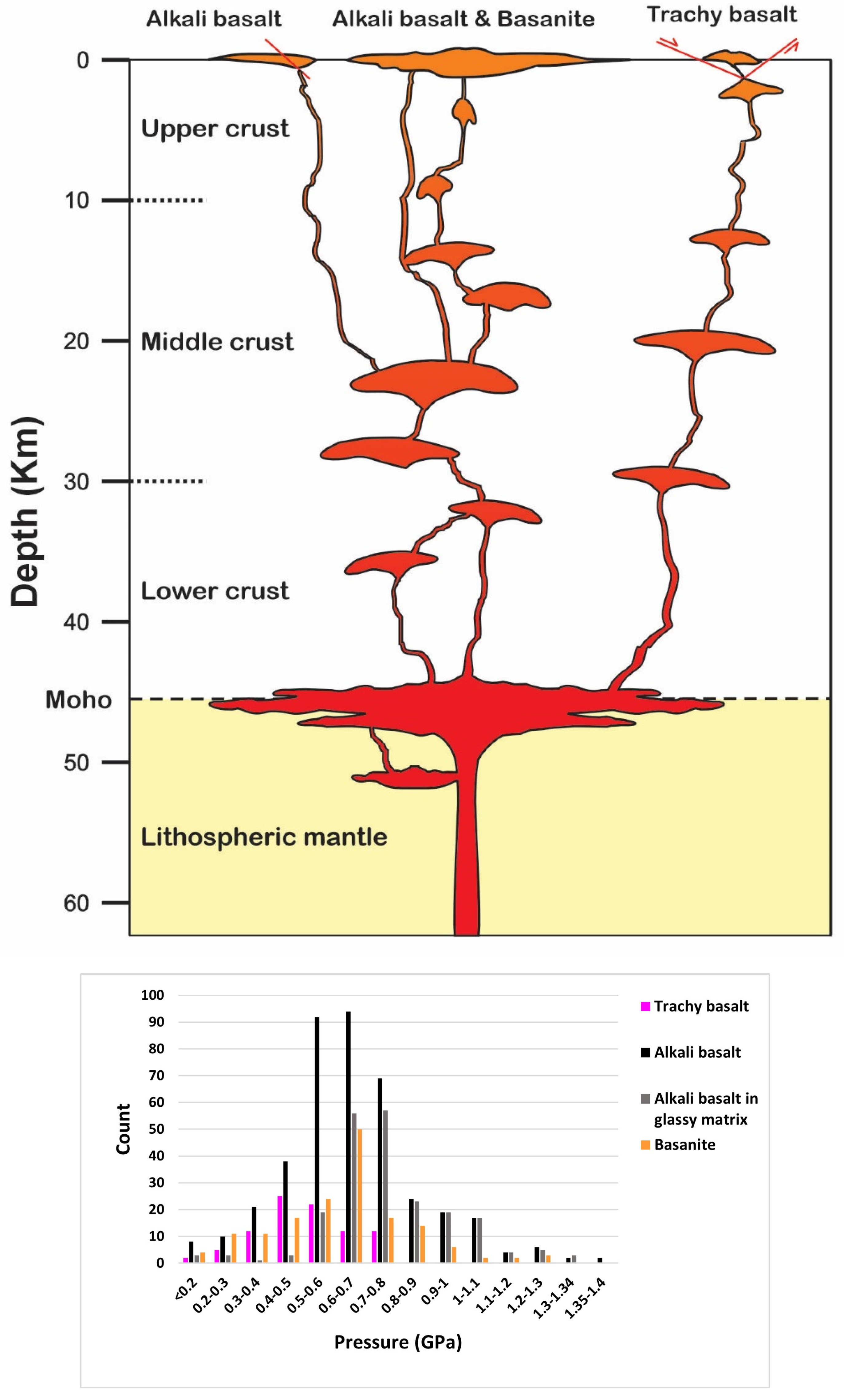

6.1. Crystallization Conditions

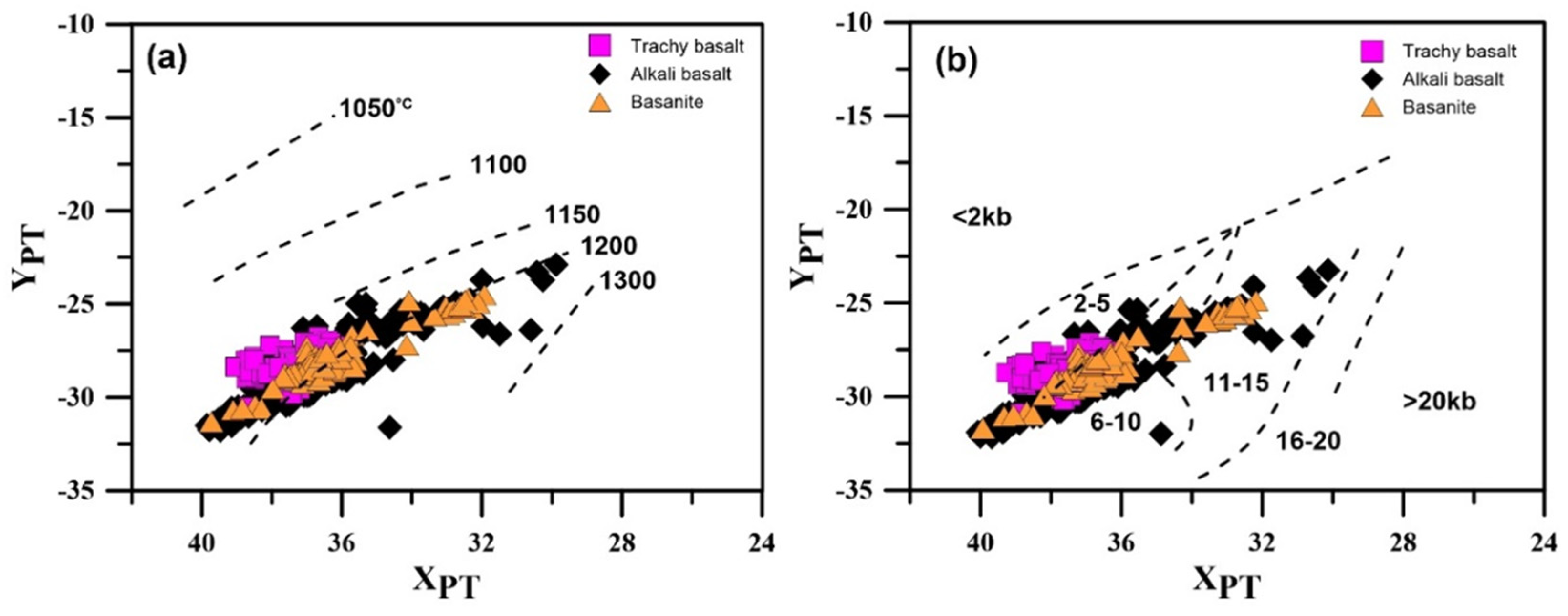

6.1.1. Whole Rock/Glass Geothermometry

6.1.2. Olivine Geothermometry

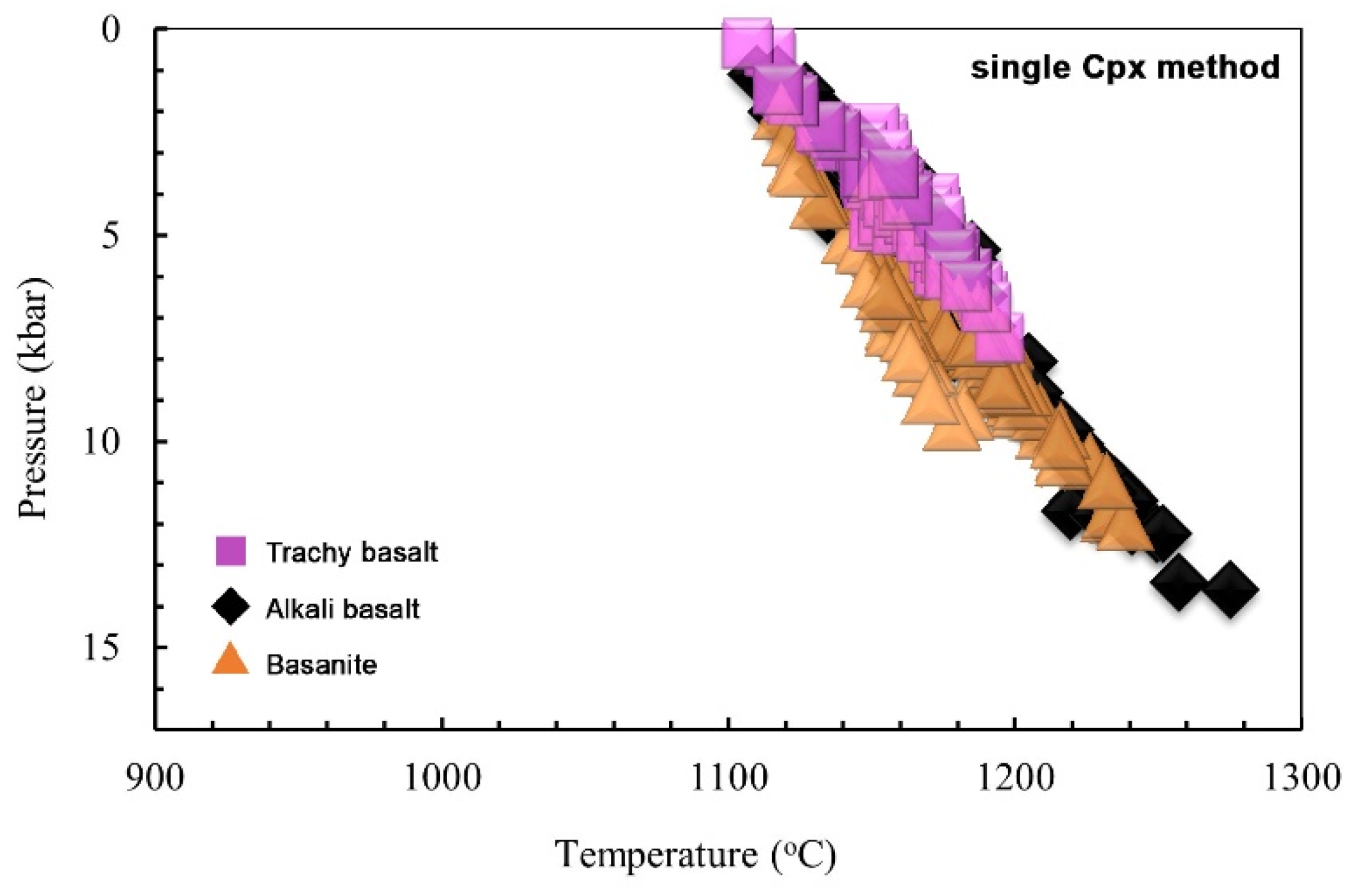

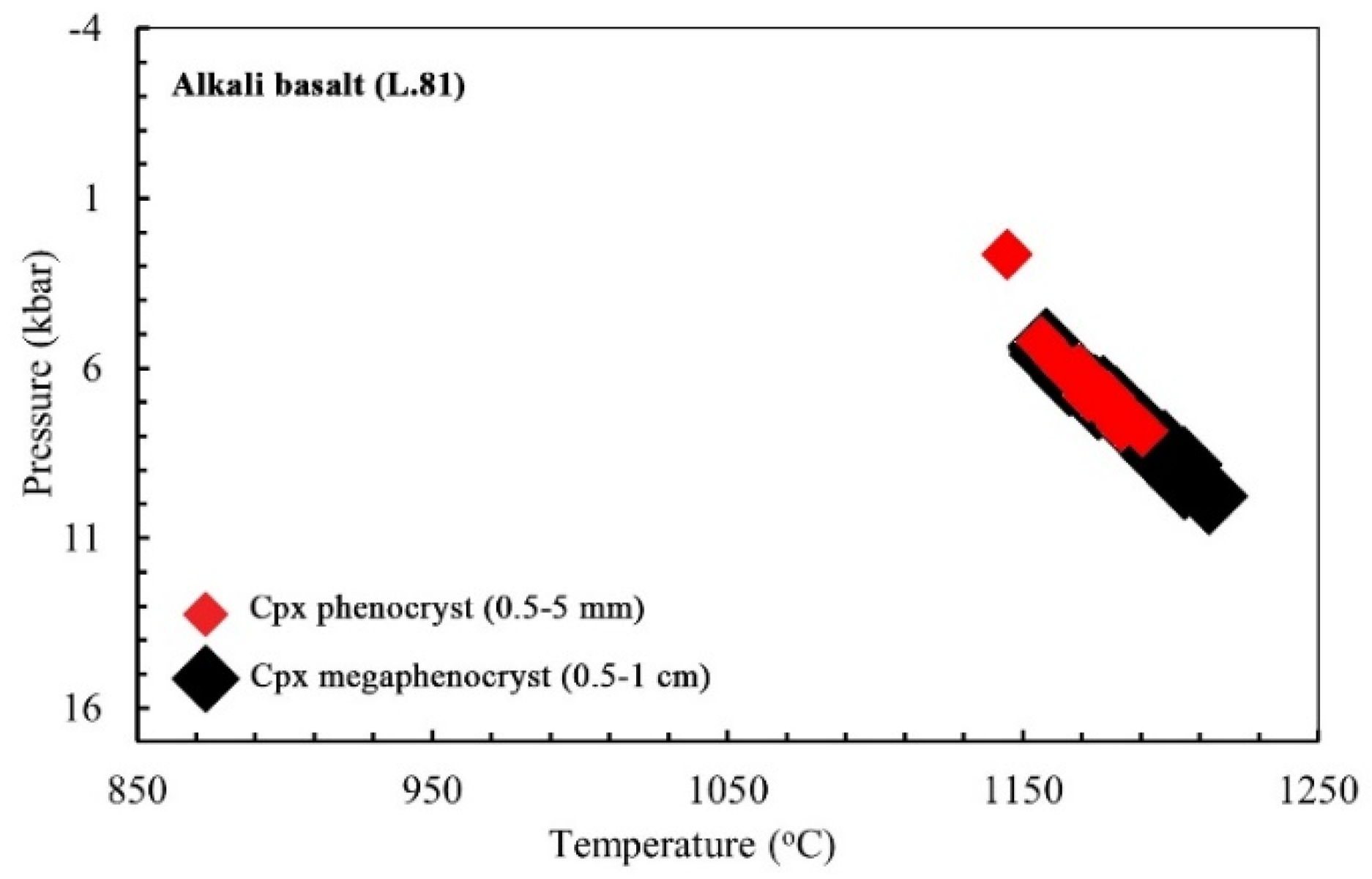

6.1.3. Clinopyroxene Geothermobarometry

6.2. Magma Crystallization Evolution Modeling

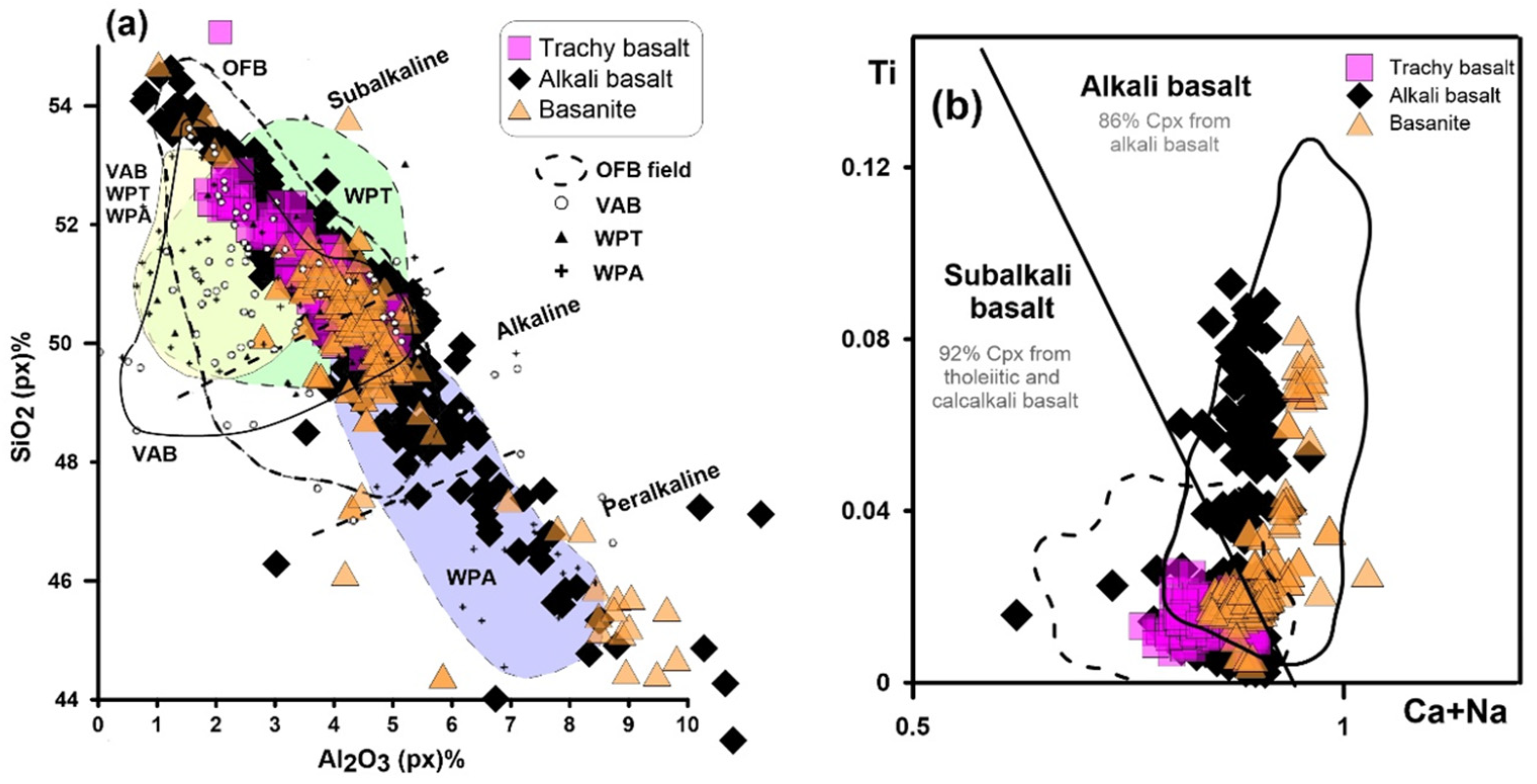

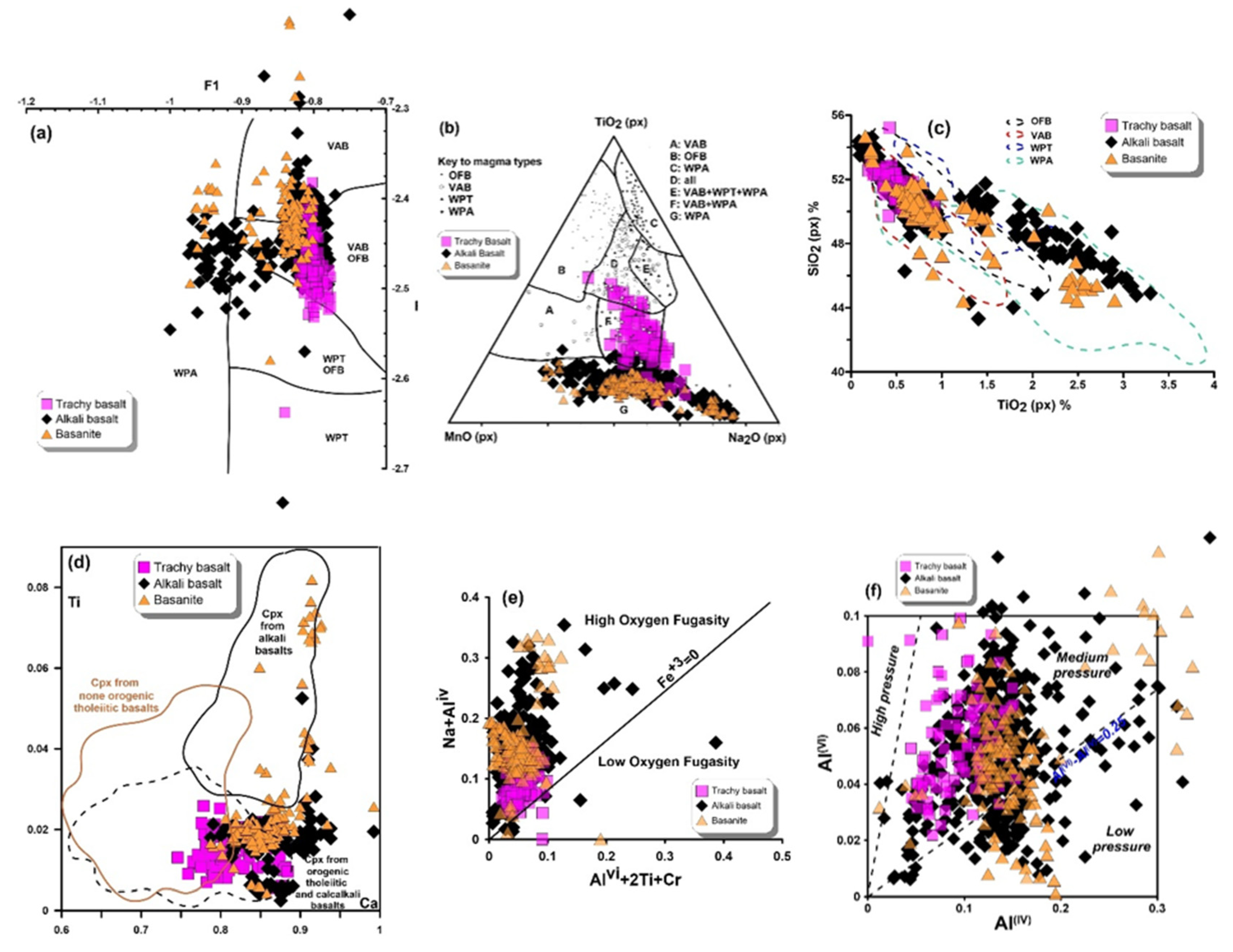

6.3. Magma Type and Tectonic Setting Based on Clinopyroxene Composition

7. Conclusions

- The whole rock geothermometry for the basanites are estimated to be 1286-1294 °C and for the alkali basalts to be 1173.5-1249.5 °C (SEE= ±71 °C, independent to pressure).

- The glass thermometry for alkali basalts is calculated 1048.7 ±71 °C independent to pressure.

- The olivine-liquid thermometry obtained 1380-1390 °C for basanites, and 1299-1336 °C for alkali basalts at a constant pressure of 1.4 GPa.

- Using different thermobarometry methods based on single clinopyroxene chemistry indicates magma crystallization for bazanite in ~1120–1240 °C at ~0.2–1.2 GPa, at depths of ~7.7–46 km. The clinopyroxene crystallization conditions for alkali basalt are determined in about 1110 to 1260 °C and 0.1 to 1.35 GPa at depths of ~3.8 to 51 km, and for trachy basalt, at temperatures of 1110 to 1190 °C and low to moderate pressures (0.05 to 0.75 GPa) at depths of 2 to 29 km.

- The single pyroxene thermobarometry, as the most practical method, illustrate some magma storages from lower crust to upper crust for basanites and alkali basalts, while trachy basalts are related to magma chambers located in middle crust to upper crust. Also, the chemical compositions of phenocrysts in the studied basaltic lavas reflect evidence of magma recharge through multi pulses of new magma injected into the existing reservoir prior to eruptions.

- The relative amount of ferric iron present reflects more oxidizing conditions and high oxygen fugacity during pyroxene crystallization for LABL.

Data availability

Author Contributions

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| LABL | Lavarab Alkaline Basaltic Lavas |

| GSI | Geological Survey of Iran |

References

- Camp, V.E.; Griffis, R.J. Character, Genesis and Tectonic Setting of Igneous Rocks in the Sistan Suture Zone, Eastern Iran. Lithos 1982, 15, 221–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tirrul, R.; Bell, I.R.; Griffis, R.J.; Camp, V.E. The Sistan Suture Zone of Eastern Iran. GSA Bulletin 1983, 94, 134–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pang, K.-N.; Chung, S.-L.; Zarrinkoub, M.H.; Mohammadi, S.S.; Yang, H.-M.; Chu, C.-H.; Lee, H.-Y.; Lo, C.-H. Age, Geochemical Characteristics and Petrogenesis of Late Cenozoic Intraplate Alkali Basalts in the Lut–Sistan Region, Eastern Iran. Chemical Geology 2012, 306–307, 40–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pang, K.-N.; Chung, S.-L.; Zarrinkoub, M.H.; Khatib, M.M.; Mohammadi, S.S.; Chiu, H.-Y.; Chu, C.-H.; Lee, H.-Y.; Lo, C.-H. Eocene–Oligocene Post-Collisional Magmatism in the Lut–Sistan Region, Eastern Iran: Magma Genesis and Tectonic Implications. Lithos 2013, 180–181, 234–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammadi, A.; Burg, J.-P.; Bouilhol, P.; Ruh, J. U–Pb Geochronology and Geochemistry of Zahedan and Shah Kuh Plutons, Southeast Iran: Implication for Closure of the South Sistan Suture Zone. Lithos 2016, 248–251, 293–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bröcker, M.; Hövelkröger, Y.; Fotoohi Rad, G.; Berndt, J.; Scherer, E.E.; Kurzawa, T.; Moslempour, M.E. The Magmatic and Tectono-Metamorphic History of the Sistan Suture Zone, Iran: New Insights into a Key Region for the Convergence between the Lut and Afghan Blocks. Journal of Asian Earth Sciences 2022, 236, 105313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biabangard, H.; Sepidbar, F.; Palin, R.M.; Boomeri, M.; Whattam, S.A.; Homam, S.M.; Shahraki, O.B. Neogene Calc-Alkaline Volcanism in Bobak and Sikh Kuh, Eastern Iran: Implications for Magma Genesis and Tectonic Setting. Miner Petrol 2023, 117, 63–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Behruzi, A. Geological Quadrangle Map of Zahedan 1973.

- Aghanabati, A. Geological map of Kuh-e Do Poshti 1987.

- Aghanabati, A. Geological quadrangle map of Daryacheh-Ye-Hamun 1991.

- Gill, R. Igneous Rocks and Processes: A Practical Guide; Wiley-Blackwell, 2010; ISBN 978-1-4443-3065-6.

- Leterrier, J.; Maury, R.C.; Thonon, P.; Girard, D.; Marchal, M. Clinopyroxene Composition as a Method of Identification of the Magmatic Affinities of Paleo-Volcanic Series. Earth and planetary science letters 1982, 59, 139–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nisbet, E.G.; Pearce, J.A. Clinopyroxene Composition in Mafic Lavas from Different Tectonic Settings. Contrib. Mineral. and Petrol. 1977, 63, 149–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wood, B.J.; Banno, S. Garnet-Orthopyroxene and Orthopyroxene-Clinopyroxene Relationships in Simple and Complex Systems. Contr. Mineral. and Petrol. 1973, 42, 109–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wells, P.R.A. Pyroxene Thermometry in Simple and Complex Systems. Contr. Mineral. and Petrol. 1977, 62, 129–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schweitzer, E.L.; Papike, J.J.; Bence, A.E. Statistical Analysis of Clinopyroxenes from Deep-Sea Basalts. American Mineralogist 1979, 64, 501–513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindsley, D.H. Pyroxene Thermometry. American Mineralogist 1983, 68, 477–493. [Google Scholar]

- Davidson, P.M. Thermodynamic Analysis of Quadrilateral Pyroxenes. Part 1: Derivation of the Ternary Nonconvergent Site-Disorder Model. Contr. Mineral. and Petrol. 1985, 91, 383–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davidson, P.M.; Lindsley, D.H. Thermodynamic Analysis of Quadrilateral Pyroxenes. Part II: Model Calibration from Experiments and Applications to Geothermometry. Contr. Mineral. and Petrol. 1985, 91, 390–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bertrand, P.; Mercier, J.-C.C. The Mutual Solubility of Coexisting Ortho- and Clinopyroxene: Toward an Absolute Geothermometer for the Natural System? Earth and Planetary Science Letters 1985, 76, 109–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soesoo, A. A Multivariate Statistical Analysis of Clinopyroxene Composition: Empirical Coordinates for the Crystallisation PT-estimations. GFF 1997, 119, 55–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nimis, P.; Taylor, W.R. Single Clinopyroxene Thermobarometry for Garnet Peridotites. Part I. Calibration and Testing of a Cr-in-Cpx Barometer and an Enstatite-in-Cpx Thermometer. Contrib Mineral Petrol 2000, 139, 541–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Putirka, K.D. Thermometers and Barometers for Volcanic Systems. Reviews in Mineralogy and Geochemistry 2008, 69, 61–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wieser, P.E.; Kent, A.J.R.; Till, C.B.; Donovan, J.; Neave, D.A.; Blatter, D.L.; Krawczynski, M.J. Barometers Behaving Badly I: Assessing the Influence of Analytical and Experimental Uncertainty on Clinopyroxene Thermobarometry Calculations at Crustal Conditions. Journal of Petrology 2023, 64, egac126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, R.; Liu, Y. Al-in-Olivine Thermometry Evidence for the Mantle Plume Origin of the Emeishan Large Igneous Province. Lithos 2016, 266–267, 362–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herzberg, C. Basalts as Temperature Probes of Earth’s Mantle. Geology 2011, 39, 1179–1180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herzberg, C.; Asimow, P.D. PRIMELT3 MEGA. XLSM Software for Primary Magma Calculation: Peridotite Primary Magma MgO Contents from the Liquidus to the Solidus. Geochemistry, Geophysics, Geosystems 2015, 16, 563–578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Hong, L.-B.; Qian, S.-P.; He, P.-L.; He, M.-H.; Yang, Y.-N.; Wang, J.-T.; Zhang, Y.-Q.; Ren, Z.-Y. The Effect of Elemental Diffusion on the Application of Olivine-Composition-Based Magmatic Thermometry, Oxybarometry, and Hygrometry: A Case Study of Olivine Phenocrysts from the Jiagedaqi Basalts, Northeast China. American Mineralogist 2023, 108, 1449–1460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herzberg, C.; Asimow, P.D.; Arndt, N.; Niu, Y.; Lesher, C.M.; Fitton, J.G.; Cheadle, M.J.; Saunders, A.D. Temperatures in Ambient Mantle and Plumes: Constraints from Basalts, Picrites, and Komatiites. Geochemistry, Geophysics, Geosystems 2007, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herzberg, C.; O’Hara, M.J. Plume-Associated Ultramafic Magmas of Phanerozoic Age. Journal of Petrology 2002, 43, 1857–1883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Putirka, K.D.; Perfit, M.; Ryerson, F.J.; Jackson, M.G. Ambient and Excess Mantle Temperatures, Olivine Thermometry, and Active vs. Passive Upwelling. Chemical Geology 2007, 241, 177–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coogan, L.A.; Saunders, A.D.; Wilson, R.N. Aluminum-in-Olivine Thermometry of Primitive Basalts: Evidence of an Anomalously Hot Mantle Source for Large Igneous Provinces. Chemical Geology 2014, 368, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falloon, T.J.; Danyushevsky, L.V.; Ariskin, A.; Green, D.H.; Ford, C.E. The Application of Olivine Geothermometry to Infer Crystallization Temperatures of Parental Liquids: Implications for the Temperature of MORB Magmas. Chemical Geology 2007, 241, 207–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Şengör, A.M.C.; Altıner, D.; Cin, A.; Ustaömer, T.; Hsü, K.J. Origin and Assembly of the Tethyside Orogenic Collage at the Expense of Gondwana Land. Geological Society, London, Special Publications 1988, 37, 119–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berberian, M. Generalized Tectonic Map of Iran. In Berberian M (Ed) Continental Deformation in the Iranian Plateau; Geological Survey of Iran. 1983. [Google Scholar]

- Dewey, J.F. Suture Zone Complexities: A Review. Tectonophysics 1977, 40, 53–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Damani Gol, Sh.; Bagheri, S. Paleogene Thrust system in the Eastern Iranian Ranges.; Kharazmi University, Tehran, 2021.

- Ghassemi, M.R.; Aghanabati, A.; Saeidi, A. Orogenic and epeirogenic events in Iran. علوم زمین 2023, 33, 87–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadeghiyan, M. Magmatism, Metallogeny and Emplacement Mechanism of Zahedan Granitoid, science faculty, Tehran University: Tehran, Iran, 2004.

- Ghasemi, H.; Sadeghian, M.; Kord, M.; Khanslizadeh, A. The evolution mechanism’s of Zahedan granitoidic batholith, southeast Iran. Iranian Journal of Crystallography and Mineralogy 2010, 17, 551–578. [Google Scholar]

- Rezaei-Kahkhaei, M.; Corfu, F.; Galindo, C.; Rahbar, R.; Ghasemi, H. Adakite Genesis and Plate Convergent Process: Constraints from Whole Rock and Mineral Chemistry, Sr, Nd, Pb Isotopic Compositions and U-Pb Ages of the Lakhshak Magmatic Suite, East Iran. Lithos 2022, 426–427, 106806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Houshmand-Mananvi, S.; Rezaei-Kahkhaei, M.; Ghasemi, H. Whole Rock Geochemistry and Tectonic Setting of Oligocene-Miocene Lavarab Lava (North Zahedan). Scientific Quarterly Journal of Geosciences 34, 67–85. [CrossRef]

- Rezaei-Kahkhaei, M.; Esmaeily, D.; Sahraei, H. Evaluation of Impact Processes in the Formation of Neshveh Volcanic Rocks, NW Saveh. Scientific Quarterly Journal of Geosciences 2018, 28, 285–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gündüz, M.; Asan, K. MagMin_PT: An Excel-Based Mineral Classification and Geothermobarometry Program for Magmatic Rocks. MinMag 2023, 87, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nimis, P. A Clinopyroxene Geobarometer for Basaltic Systems Based on Crystal-Structure Modeling. Contrib Mineral Petrol 1995, 121, 115–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Putirka, K.D.; Mikaelian, H.; Ryerson, F.; Shaw, H. New Clinopyroxene-Liquid Thermobarometers for Mafic, Evolved, and Volatile-Bearing Lava Compositions, with Applications to Lavas from Tibet and the Snake River Plain, Idaho. American Mineralogist 2003, 88, 1542–1554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Putirka, K.; Ryerson, F.J.; Mikaelian, H. New Igneous Thermobarometers for Mafic and Evolved Lava Compositions, Based on Clinopyroxene + Liquid Equilibria. Am Mineral 2003, 88, 1542–1554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yavuz, F. WinPyrox: A Windows Program for Pyroxene Calculation Classification and Thermobarometry. American Mineralogist 2013, 98, 1338–1359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neave, D.A.; Putirka, K.D. A New Clinopyroxene-Liquid Barometer, and Implications for Magma Storage Pressures under Icelandic Rift Zones. American Mineralogist 2017, 102, 777–794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winchester, J.A.; Floyd, P.A. Geochemical Discrimination of Different Magma Series and Their Differentiation Products Using Immobile Elements. Chemical Geology 1977, 20, 325–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peate, D.W.; Hawkesworth, C.J. Lithospheric to Asthenospheric Transition in Low-Ti Flood Basalts from Southern Paraná, Brazil. Chemical Geology 1996, 127, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simon, S.B.; Sutton, S.R. Valences of Ti, Cr, and V in Apollo 17 High-Ti and Very Low-Ti Basalts and Implications for Their Formation. Meteoritics & Planetary Science 2018, 53, 2138–2154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, M. Igneous Petrogenesis; Springer Netherlands: Netherlands, 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Morimoto, N.; Kitamura, M. Q-J Diagram for Classification Ofpyroxenes. Joumal ofthe Japanese Association ofMineralogy, Petrology and Economical Geolog 78.

- Morimoto, N.; Fabrise, J.; Ferguson, A.; Ginzburg, I.V.; Ross, M.; Seifert, F.A.; Zussman, J.; Akoi, K.; Gottardi, G. Nomenclature of Pyroxenes. American Mineralogist 173, 1133; 1123–1133. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, X.; Hou, T.; Wang, M.; Zhang, C.; Zhang, Z.; Pan, R.; Marxer, F.; Zhang, H. A New Clinopyroxene Thermobarometer for Mafic to Intermediate Magmatic Systems. European Journal of Mineralogy 2021, 33, 621–637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arabzadeh Baniasadi, M.; Ghasemi, H.; Angiboust, S.; Rezaei Kahkhaei, M.; Papadopoulou, L. Application of clinopyroxene geothermobarometers on the gabbro/dioritic rocks associated with the Gowd-e-Howz (Siah-Kuh) granitoid stock, Baft, Kerman. Scientific Quarterly Journal of Geosciences 2024, 34, 117–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Helz, R.T.; Thornber, C.R. Geothermometry of Kilauea Iki Lava Lake, Hawaii. Bull Volcanol 1987, 49, 651–668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montierth, C.; Johnston, A.D.; Cashman, K.V. An Empirical Glass-Composition-Based Geothermometer for Mauna Loa Lavas. In Mauna Loa Revealed: Structure, Composition, History, and Hazards; American Geophysical Union (AGU), 1995; pp. 207–217 ISBN 978-1-118-66433-9.

- Yang, H.-J.; Frey, F.A.; Clague, D.A.; Garcia, M.O. Mineral Chemistry of Submarine Lavas from Hilo Ridge, Hawaii: Implications for Magmatic Processes within Hawaiian Rift Zones. Contrib Mineral Petrol 1999, 135, 355–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roeder, P.L.; Emslie, R.F. Olivine-Liquid Equilibrium. Contr. Mineral. and Petrol. 1970, 29, 275–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toplis, M.J. The Thermodynamics of Iron and Magnesium Partitioning between Olivine and Liquid: Criteria for Assessing and Predicting Equilibrium in Natural and Experimental Systems. Contrib Mineral Petrol 2005, 149, 22–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rhodes, J.M.; Dungan, M.A.; Blanchard, D.P.; Long, P.E. Magma Mixing at Mid-Ocean Ridges: Evidence from Basalts Drilled near 22° N on the Mid-Atlantic Ridge. Tectonophysics 1979, 55, 35–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nimis, P.; Ulmer, P. Clinopyroxene Geobarometry of Magmatic Rocks Part 1: An Expanded Structural Geobarometer for Anhydrous and Hydrous, Basic and Ultrabasic Systems. Contrib Mineral Petrol 1998, 133, 122–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Putirka, K.; Johnson, M.; Kinzler, R.; Longhi, J.; Walker, D. Thermobarometry of Mafic Igneous Rocks Based on Clinopyroxene-Liquid Equilibria, 0–30 Kbar. Contrib Mineral Petrol 1996, 123, 92–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tormey, D.R.; Grove, T.L.; Bryan, W.B. Experimental Petrology of Normal MORB near the Kane Fracture Zone: 22°–25° N, Mid-Atlantic Ridge. Contr. Mineral. and Petrol. 1987, 96, 121–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berndt, J.; Koepke, J.; Holtz, F. An Experimental Investigation of the Influence of Water and Oxygen Fugacity on Differentiation of MORB at 200 MPa. Journal of Petrology 2005, 46, 135–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thy, P.; Lesher, C.E.; Nielsen, T.F.D.; Brooks, C.K. Experimental Constraints on the Skaergaard Liquid Line of Descent. Lithos 2006, 92, 154–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Botcharnikov, R.E.; Koepke, J.; Holtz, F.; McCammon, C.; Wilke, M. The Effect of Water Activity on the Oxidation and Structural State of Fe in a Ferro-Basaltic Melt. Geochimica et Cosmochimica Acta 2005, 69, 5071–5085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Husen, A.; Almeev, R.R.; Holtz, F. The Effect of H2O and Pressure on Multiple Saturation and Liquid Lines of Descent in Basalt from the Shatsky Rise. Journal of Petrology 2016, 57, 309–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hossein-Zadeh, S. Estimation of Moho Depth in Iran by Combination of Gravity and Seismic Data, Institude for advanced studies in basic sceineces, Gava Zang: Znajan, Iran, 2012.

- Sepahvand, M.R. Variations of Moho Depth and Vp/Vs Ratio in Central and Eastern Iran Using the Zhu and Kanamori Method, Kerman Graduate University of Technology (KGUT): Kerman, Iran, 2016.

- LeBas, M.J. The Role of Aluminium in Igneous Clinopyroxenes with Relation to Their Parentage. Am. J. Sci. 1962, 260, 267–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kilinc, A.; Carmichael, I.S.E.; Rivers, M.L.; Sack, R.O. The Ferric-Ferrous Ratio of Natural Silicate Liquids Equilibrated in Air. Contr. Mineral. and Petrol. 1983, 83, 136–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kress, V.C.; Carmichael, I.S.E. The Compressibility of Silicate Liquids Containing Fe2O3 and the Effect of Composition, Temperature, Oxygen Fugacity and Pressure on Their Redox States. Contr. Mineral. and Petrol. 1991, 108, 82–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moretti, R. Polymerisation, Basicity, Oxidation State and Their Role in Ionic Modelling of Silicate Melts. Annals of Geophysics 2005, 48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ottonello, G.; Moretti, R.; Marini, L.; Vetuschi Zuccolini, M. Oxidation State of Iron in Silicate Glasses and Melts: A Thermochemical Model. Chemical Geology 2001, 174, 157–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- France, L.; Ildefonse, B.; Koepke, J.; Bech, F. A New Method to Estimate the Oxidation State of Basaltic Series from Microprobe Analyses. Journal of Volcanology and Geothermal Research 2010, 189, 340–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chinner, G.A. Pelitic Gneisses with Varying Ferrous/Ferric Ratios from Glen Clova, Angus, Scotland. Journal of Petrology 1960, 1, 178–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rumble, D. Fe-Ti Oxide Minerals from Regionally Metamorphosed Quartzites of Western New Hampshire. Contr. Mineral. and Petrol. 1973, 42, 181–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Powell, R.; Sandiford, M. Sapphirine and Spinel Phase Relationships in the System FeO-MgO-Al2O3-SiO2-TiO2-O2 in the Presence of Quartz and Hypersthene. Contr. Mineral. and Petrol. 1988, 98, 64–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clarke, G.L.; Powell, R.; Guiraud, M. Low-Pressure Granulite Facies Metapelitic Assemblages and Corona Textures from MacRobertson Land, East Antarctica: The Importance of Fe203and TiOz in Accounting for Spinel-Bearing Assemblages. Journal of Metamorphic Geology 1989, 7, 323–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ague, J.J.; Baxter, E.F.; Eckert, J.O. , JR High fO2 During Sillimanite Zone Metamorphism of Part of the Barrovian Type Locality, Glen Clova, Scotland. Journal of Petrology 2001, 42, 1301–1320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evans, K.A. Redox Decoupling and Redox Budgets: Conceptual Tools for the Study of Earth Systems. Geology 2006, 34, 489–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diener, J.F.A.; Powell, R. Influence of Ferric Iron on the Stability of Mineral Assemblages. Journal of Metamorphic Geology 2010, 28, 599–613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eugster, H.P. Reduction and Oxidation in Metamorphism. Researches in Geochemistry (ed. Ableson, P.H.), 1959; 397–426. [Google Scholar]

- Huebner, J.S. Buffering Techniques for Hydrostatic Systems at Elevated Pressures. In Research Techniques for High Pressure and High Temperature; Ulmer, G.C., Ed.; Springer: Berlin, Heidelberg, 1971; ISBN 978-3-642-88097-1. [Google Scholar]

- Spear, F.S. Metamorphic Phase Equilibria and Pressure–Temperature–Time Paths; Mineralogical Society of America: Washington DC, 1993; ISBN 939950. [Google Scholar]

- Aoki, K.-I.; Shiba, I. Pyroxenes from Lherzolite Inclusions of Itinome-Gata, Japan. Lithos 1973, 6, 41–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Sample No. | L.10 | L.37 | L.51 | L.52 | L.61 | L.75 | L.81 | L.86 | L.87 | L.92 | L.100 | L.13 | L.44 | L.42 | L.53 | L.64 | L.80 | L.57 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Long (UTM) | 295337 | 287369 | 287867 | 288842 | 292059 | 288618 | 290812 | 290912 | 291176 | 291988 | 289589 | 295701 | 290228 | 289305 | 288842 | 290065 | 290812 | 279830 |

| Lat (UTM) | 3316272 | 3322675 | 3329220 | 3329609 | 3318618 | 3318762 | 3319096 | 3319286 | 3319136 | 3317670 | 3326702 | 3317073 | 3323539 | 3323532 | 3329609 | 3323967 | 3319096 | 3342786 |

| Rock type | TA | AB | AB | AB | AB | AB | AB | AB | AB | AB | AB | Bs | Bs | Bs | Bs | Bs | Bs | Bs |

| SiO2 | 52.7 | 49.65 | 47.37 | 48.58 | 46.93 | 49.6 | 49.33 | 51.27 | 48.72 | 48.9 | 49.9 | 49.2 | 49 | 47.92 | 48.72 | 49.14 | 49.66 | 42.37 |

| TiO2 | 0.85 | 0.79 | 0.64 | 0.75 | 1.71 | 0.77 | 0.78 | 0.72 | 0.83 | 0.69 | 0.73 | 0.69 | 0.68 | 0.45 | 0.63 | 0.78 | 0.7 | 1.67 |

| Al2O3 | 17.48 | 13.52 | 15.46 | 12.53 | 15.91 | 13.23 | 13.13 | 13.64 | 15.22 | 15.71 | 13.17 | 14 | 13.01 | 13.66 | 12.41 | 12.81 | 13.4 | 14.42 |

| Fe2O3T | 8.31 | 8.33 | 9.09 | 9.21 | 9.12 | 8.63 | 8.57 | 7.73 | 8.87 | 8.29 | 8.19 | 8.61 | 7.59 | 9.33 | 337.59 | 9.35 | 8.19 | 11.66 |

| MnO | 0.13 | 0.15 | 0.19 | 0.19 | 0.11 | 0.13 | 0.16 | 0.15 | 0.15 | 0.16 | 0.13 | 0.18 | 0.16 | 0.18 | 0.14 | 0.13 | 0.16 | 0.19 |

| MgO | 2.94 | 7.72 | 9.69 | 8.15 | 8.32 | 7.55 | 6.81 | 7.7 | 8.45 | 6.69 | 7.91 | 8.87 | 10.16 | 13 | 11.45 | 7.87 | 8.3 | 11.12 |

| CaO | 9.49 | 8.32 | 9.61 | 9.92 | 8.38 | 8.4 | 9.04 | 7.15 | 9.55 | 8.97 | 8.11 | 7.95 | 8.32 | 8.94 | 7.35 | 8.85 | 8.13 | 10.48 |

| Na2O | 3 | 3.88 | 3.05 | 4.53 | 3.56 | 4.1 | 4.04 | 4.12 | 1.9 | 4.25 | 4.83 | 3.39 | 3.46 | 2.3 | 3.31 | 4.26 | 3.87 | 4.47 |

| K2O | 2.77 | 3.1 | 1.97 | 1.24 | 1.48 | 1.68 | 3.38 | 3.73 | 3.08 | 2.58 | 1.9 | 3.24 | 3.64 | 1.71 | 3.49 | 2.35 | 3.41 | 0.59 |

| P2O5 | 0.6 | 0.85 | 0.37 | 0.8 | 0.8 | 0.87 | 0.89 | 0.98 | 0.54 | 0.57 | 0.88 | 0.75 | 0.95 | 0.27 | 1.01 | 0.89 | 0.93 | 0.63 |

| LOI | 1.35 | 3.09 | 1.98 | 3.4 | 3.35 | 4.46 | 3.36 | 2.32 | 2.42 | 2.85 | 3.63 | 2.65 | 2.39 | 1.7 | 3.26 | 2.92 | 2.56 | 2.08 |

| Mg# | 53.6 | 75.55 | 76.6 | 73.74 | 73.66 | 73.67 | 72.87 | 77.63 | 74.66 | 72.69 | 76.18 | 77.19 | 81.69 | 80.59 | 83.24 | 73.42 | 77.36 | 73.96 |

| A/NK | 3.03 | 1.94 | 3.08 | 2.17 | 3.16 | 2.29 | 1.77 | 1.74 | 3.06 | 2.3 | 1.96 | 2.11 | 1.83 | 3.4 | 1.82 | 1.94 | 1.84 | 2.85 |

| A/CNK | 1.15 | 0.88 | 1.06 | 0.8 | 1.19 | 0.93 | 0.8 | 0.91 | 1.05 | 0.99 | 0.89 | 0.96 | 0.84 | 1.05 | 0.88 | 0.83 | 0.87 | 0.93 |

| K2O+Na2O | 5.77 | 6.97 | 5.03 | 5.77 | 5.04 | 5.78 | 7.42 | 7.84 | 4.97 | 6.83 | 6.73 | 6.63 | 7.11 | 4.01 | 6.8 | 6.61 | 7.28 | 5.06 |

| K2O/Na2O | 0.92 | 0.8 | 0.65 | 0.27 | 0.42 | 0.41 | 0.84 | 0.91 | 1.62 | 0.61 | 0.39 | 0.96 | 1.05 | 0.75 | 1.06 | 0.55 | 0.88 | 0.13 |

| Cs | 0.65 | 7.67 | 0.95 | 7.26 | 0.97 | 7.54 | 4.77 | 4.68 | 1.74 | 11.98 | 9.07 | 3.66 | 3.52 | 0.65 | 6.13 | 6.35 | 3.79 | 1.19 |

| Ba | 991 | 1387 | 442 | 902 | 748 | 1271 | 1123 | 1542 | 957 | 989 | 1160 | 1235 | 1547 | 409 | 1462 | 1259 | 1475 | 822 |

| Rb | 75 | 173 | 66 | 108 | 40 | 168 | 216 | 79 | 64 | 51 | 158 | 77 | 100 | 27 | 75 | 145 | 125 | 24 |

| Sr | 800 | 1010 | 1130 | 1121 | 913 | 819 | 840 | 789 | 507 | 674 | 811 | 812 | 843 | 518 | 718 | 952 | 954 | 698 |

| Pb | 11.69 | 19.49 | 5.38 | 15.28 | 2.71 | 17.61 | 17.4 | 18.44 | 9.57 | 10.98 | 16.81 | 16.41 | 17.32 | 6.61 | 17.73 | 18.37 | 17.91 | 5.08 |

| Th | 5 | 9.34 | 2.64 | 7.41 | 4.24 | 9.83 | 9.62 | 10.59 | 4.03 | 4.57 | 8.25 | 7.67 | 8.53 | 2.21 | 8.89 | 8.68 | 10.87 | 8.3 |

| U | 1.4 | 2.77 | 0.71 | 2.22 | 0.91 | 3.23 | 3.16 | 2.43 | 1.09 | 1.41 | 2.47 | 2.15 | 2.39 | 0.64 | 2.66 | 2.63 | 2.88 | 1.64 |

| Zr | 167 | 213 | 103 | 174 | 280 | 204 | 203 | 200 | 131 | 147 | 175 | 185 | 203 | 97 | 178 | 200 | 221 | 278 |

| Ta | 2.37 | 1.21 | 0.46 | 1.05 | 3.6 | 1.39 | 1.19 | 1.05 | 0.93 | 1.32 | 0.92 | 0.84 | 0.93 | 0.5 | 1 | 1.19 | 2.16 | 3.63 |

| Hf | 5.77 | 6.23 | 3.38 | 5.38 | 7.83 | 5.88 | 5.84 | 5.36 | 3.95 | 4.33 | 5 | 5.53 | 5.88 | 3.03 | 5.55 | 6.01 | 6.39 | 7.55 |

| Y | 26.4 | 23.93 | 16.55 | 22.56 | 20.38 | 22.08 | 22.14 | 21.2 | 21.66 | 23.06 | 20.75 | 22.37 | 24.24 | 14.87 | 21.5 | 23.24 | 23.62 | 24.68 |

| Nb | 23.4 | 18.5 | 14.2 | 15.3 | 38.9 | 19.8 | 18.1 | 20.6 | 17.9 | 19.7 | 18.2 | 19 | 20.6 | 12.6 | 18.7 | 17.9 | 20.2 | 47 |

| La | 20.74 | 30.2 | 14.19 | 25.22 | 32.18 | 28.61 | 26.91 | 27.1 | 15.98 | 17.54 | 25.62 | 25.87 | 28.35 | 13.06 | 28.3 | 27.28 | 29.54 | 51.61 |

| Ce | 35.28 | 49.82 | 23.97 | 43.12 | 53.87 | 46.69 | 44.23 | 45.33 | 27.06 | 29.34 | 43.24 | 42.22 | 47.74 | 22.16 | 46.61 | 45.56 | 49.12 | 83.62 |

| Pr | 5.16 | 7.07 | 3.64 | 6.15 | 8.18 | 6.72 | 6.23 | 6.18 | 3.95 | 4.38 | 6.19 | 5.92 | 7.04 | 3.19 | 6.39 | 6.5 | 7 | 11.28 |

| Nd | 20.05 | 27.56 | 13.66 | 25.28 | 31.18 | 25.02 | 24.07 | 24.19 | 16.3 | 17.92 | 23.94 | 22.8 | 26.23 | 11.92 | 24.67 | 25.95 | 25.99 | 40.94 |

| Sm | 6.1 | 7.29 | 3.27 | 6.27 | 7.1 | 6.44 | 6.69 | 6.58 | 4.76 | 5.27 | 6.58 | 6.32 | 6.93 | 2.95 | 6.89 | 7.07 | 7.12 | 7.17 |

| Eu | 2.21 | 2.61 | 1.01 | 1.92 | 2.48 | 2.24 | 2.23 | 2.12 | 1.5 | 1.8 | 2.01 | 2.22 | 2.45 | 0.98 | 2.55 | 2.42 | 2.5 | 2.15 |

| Gd | 3.88 | 4.65 | 2.49 | 4.32 | 4.96 | 4.41 | 4.45 | 4.37 | 3.07 | 3.67 | 4.07 | 4.11 | 4.67 | 2.35 | 4.42 | 4.64 | 4.46 | 5.83 |

| Tb | 0.74 | 0.76 | 0.48 | 0.81 | 0.88 | 0.71 | 0.75 | 0.74 | 0.64 | 0.69 | 0.76 | 0.7 | 0.72 | 0.4 | 0.78 | 0.78 | 0.71 | 0.99 |

| Dy | 4.01 | 4.23 | 2.66 | 4.11 | 3.94 | 3.6 | 3.68 | 3.56 | 3.4 | 3.89 | 3.82 | 3.53 | 4.19 | 2.28 | 3.92 | 4.19 | 3.76 | 5.5 |

| Ho | 0.99 | 0.86 | 0.59 | 0.8 | 0.81 | 0.79 | 0.8 | 0.68 | 0.8 | 0.84 | 0.75 | 0.83 | 0.87 | 0.54 | 0.74 | 0.9 | 0.82 | 0.9 |

| Er | 2.63 | 2.47 | 1.61 | 2.16 | 2 | 2.29 | 2.04 | 2.04 | 2.11 | 2.44 | 2.05 | 2.18 | 2.43 | 1.46 | 2.09 | 2.27 | 2.42 | 2.4 |

| Tm | 0.48 | 0.42 | 0.31 | 0.36 | 0.3 | 0.4 | 0.36 | 0.37 | 0.34 | 0.42 | 0.38 | 0.39 | 0.4 | 0.25 | 0.38 | 0.38 | 0.41 | 0.4 |

| Yb | 2.86 | 2.43 | 1.4 | 1.83 | 1.62 | 2.32 | 2.2 | 1.71 | 1.73 | 2.17 | 1.84 | 2.37 | 2.44 | 1.49 | 1.82 | 2.4 | 2.4 | 1.61 |

| Lu | 0.55 | 0.46 | 0.28 | 0.39 | 0.3 | 0.38 | 0.4 | 0.4 | 0.38 | 0.44 | 0.36 | 0.4 | 0.48 | 0.28 | 0.36 | 0.46 | 0.47 | 0.36 |

| Ga | 19.54 | 12.91 | 11.82 | 9.99 | 18.65 | 12.62 | 12.33 | 12.18 | 12.37 | 13.56 | 11.03 | 13.3 | 12.43 | 10.33 | 12.08 | 12.22 | 12.72 | 15.13 |

| Sc | 34.03 | 34.78 | 35.67 | 35.49 | 20.7 | 28.79 | 32.93 | 27.18 | 32.46 | 36.25 | 29.66 | 33.96 | 37.52 | 29.21 | 31.17 | 34.34 | 32.05 | 27.29 |

| V | 327.09 | 217.86 | 204.78 | 184.8 | 193.05 | 224.91 | 207.33 | 227.39 | 240.89 | 265.85 | 214.23 | 240.73 | 227.47 | 176.06 | 220.26 | 213.95 | 226.78 | 234.31 |

| Cr | 59.6 | 524.2 | 428.5 | 526.8 | 256.8 | 417.5 | 384.8 | 372.9 | 321 | 378.9 | 690.3 | 450.7 | 736 | 632.2 | 542.7 | 671.5 | 346.4 | 432.3 |

| Co | 28.29 | 39.2 | 44.97 | 35.07 | 34.86 | 32.64 | 31.49 | 30.81 | 30.71 | 34.43 | 33.04 | 37.19 | 34.96 | 53.29 | 32.55 | 38.92 | 32.45 | 45.91 |

| Ni | 31.41 | 190.59 | 356.86 | 186.95 | 114.44 | 130.53 | 122.14 | 130.2 | 78.56 | 77.23 | 188.87 | 190 | 200.64 | 537.26 | 185.03 | 208.87 | 127.5 | 267.22 |

| Cu | 77.53 | 126.4 | 65.22 | 91.69 | 62.15 | 134.93 | 115.26 | 130.57 | 66.68 | 112.75 | 107.08 | 114.46 | 119.87 | 71.42 | 122.49 | 105.72 | 115.45 | 77.98 |

| Zn | 91.43 | 71.29 | 64.71 | 68.79 | 91.25 | 68.4 | 64.58 | 68.27 | 70.21 | 74.31 | 69.02 | 73.24 | 70.78 | 63.38 | 66.69 | 70.72 | 70.6 | 85.38 |

| Ti | 6490.43 | 5274.53 | 4809.65 | 4688.33 | 12425.2 | 4728.06 | 4965.11 | 4929.6 | 4929.6 | 5581.54 | 4700.39 | 5362.5 | 5390.8 | 3542.09 | 4700.39 | 4935.31 | 4972.23 | 10551.2 |

| Mn | 1138.84 | 1201.86 | 1100.56 | 1102.14 | 1026.95 | 1095.78 | 1056.61 | 1001.35 | 1014.64 | 1083.29 | 1015.75 | 1143.2 | 1090.14 | 1064.18 | 995.81 | 1132.2 | 1035.97 | 1212.9 |

| W | 0.86 | 1.8 | 0.18 | 1.66 | 0.11 | 1.81 | 1.79 | <0.10 | <0.10 | <0.10 | 1.86 | 0.55 | 0.76 | <0.10 | 0.34 | 1.79 | 1.47 | 0.47 |

| Clinopyroxene-only Thermobarometry | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nimis (1995) (SEE*= ±0.16 GPa) | Nimis and Ulmer (1998) (SEE= ±0.15 GPa) | Seosoo (1997) | Putirka (2008) RiMG | ||||

| Equation (32a) (SEE= ±0.26 GPa) |

Equation (32b) (SEE= ±0.26 GPa) |

Equation (32d) (SEE= ±58 °C) |

|||||

| P (GPa) | P (GPa) | T ( °C) | P (GPa) | P (GPa) | P (GPa) | T( °C) | |

|

Trachy basalt n = 93 |

0.007-0.27 (avg=0.11) |

0.0024-0.27 (avg=0.1) |

1150-1200 | 0.3-0.6 | 0.12-0.9 (avg=0.55) |

0.13-0.9 (avg=0.51) |

1156-1223 (avg=1190) |

|

Alkali basalts n = 418 |

0.003-1.19 (avg=0.2) |

0.002-1.23 (avg=0.2) |

1165-1270 | 0.4-1.45 | 0.03-1.99 (avg=0.74) |

0.1-1.4 (avg=0.65) |

1135-1287 (avg=1209) |

|

Basanites n = 169 |

0.003-0.5 (avg=0.19) |

0.005-0.52 (avg=0.18) |

1170-1230 | 0.5-1.25 | 0.1-1.57 (avg=0.8) |

0.15-1.34 (avg=0.71) |

934-1278 (avg=1200) |

| Clinopyroxene- Whole Rock Equilibrium Thermobarometry | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Putirka et al. (2003) | Putirka (2008) | Putirka (2008) |

Neave and Putirka (2017) | ||

| T ( °C) | P (GPa) | P (GPa) | T ( °C) | P (GPa) | |

| (SEE*= ±61 °C) | (SEE= ±0.48 GPa) |

Equation (32c) (SEE= ±0.5 GPa) |

Equation (33) (SEE= ±46 °C) |

(SEE= ±0.14 GPa) | |

| Trachy basalt | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A |

|

Alkali basalt n = 15 |

1071-1215 (avg=1197.8) |

0.77-1 (avg=0.87) |

0.55-1.05 (avg=0.78) |

1132-1206 (avg=1159) |

0.21-0.67 (avg=0.44) |

| Basanite | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).