1. Introduction

By nature, wind and solar energy generation are volatile and only partly predictable. As long as they contribute only a small part of the total energy supply, the remaining traditional power stations, such as coal, gas, and nuclear in conjunction with pumped storage, can compensate for this volatility.

Since there are times with no sun or wind power, the backup power stations must be able to provide 100% of the required energy load, and otherwise compensate for the difference between renewable supply and grid demand.

With increasing photovoltaics (PV) and wind power plants (WPP), there are more and more situations when renewable production exceeds the demand. When PV devices cannot be automatically switched off or ramped down, overproduction may occur, which must be avoided at any cost. This situation is the reason for regularly occurring negative revenue at the German electricity exchange to encourage pumped hydro power stations in Austria and Switzerland to absorb the surplus energy.

With the goal of eventually achieving a close to 100% renewable electricity supply, storage devices are introduced. Traditionally, there are pumped storage hydro power stations for this purpose. Their availability depends on the geographic situation, limiting their storage capacity [

1]. As there are no plans for further exploring new sites in Germany for pumped hydro storage, we assume no changes to that capacity in the future.

As Germany’s transition to renewable energy is far advanced, we take the measured electricity data of 2023 or 2024 as a statistical basis for the exploration of further expansion of renewable energy [

2], to investigate the occurring problems due to energy volatility and their possible solution by introducing storage systems. Therefore, we restrict our investigation on Germany and neglect the effects of imports and exports.

Apart from the existing pumped storage infrastructure, we will investigate the use of batteries as well as hydrogen gas storage at various degrees of renewable contribution. We assume that today’s load patterns have to be covered by power supply at all times, implying that the industry’s demand flexibility cannot be expanded substantially. Further, we imply that temporal load patterns remain statistically valid in an all-electric society. By making transparent assumptions about the technical properties and the involved costs, we can achieve realistic future scenarios as extrapolations of the current data.

The purpose of this study is not to deliver an exact model of the future sustainable power supply, but mainly to evaluate the effect of storage systems on the real volatility of renewable energy production. In doing so, we are going to quantitatively assess the validity of various scenarios published by other authors.

Most importantly, we discuss the feasibility study from the institutes Prognos, Agora Energiewende, Öko Institute and Wuppertal Institute, which guides the current political decisions in Germany, “Klimaneutrales Deutschland 2045” (climate neutral Germany 2045, in the following “KND2045”) [

3]. This will be the main reference for our investigation, in particular for the energy requirements and the plans for expanding renewable energy. There have been further investigations worth mentioning, “dena Leitstudie Aufbruch Klimaneutralität” from 2021 [

4] and a study of the Umweltbundesamt (Federal office of the environment) “Strommarkt und Klimaschutz: Transformation der Stromerzeugung bis 2050” [

5]. These and others are referenced in a meta-study of the scientific service of the German parlament “Zur Deckung des zusätzlichen Strombedarfs durch erneuerbare Energien im Zuge der Energiewende” (About the supply of additional electrical power requirements by renewable energies in the course of the energy transition) [

6].

There have also been critical voices who raised doubts about the feasibility of the energy transition presented in the KND2045 report. In 2017 Hans-Werner Sinn analysed the German energy transformation, which is founded on volatile power sources [

7]. He pointed out that not only the energy deficit phases as a key problem of renewable energy that is not easily solvable, but also the phases of overproduction. It is astonishing, that his warnings have not been taken seriously since then. Many of the problems that we have with negative prices at the electricity exchange now, could have easily been solved by making solar power inverters better controllabe. A group of academic and industry energy experts from the initiative AKEN ("Aktionskreis Energie & Naturschutz") analysed the main study from Prognos and Agora Energiewende immediately after its publication [

8], and asked questions, which, according to the AKEN authors, have not been adequately answered [

9].

The most elaborate scenario has been developed by Klaus Maier and Andreas Geisenheiner [

10], together with a companion study by Klaus Maier, focusing on the actual requirements of the energy transition from an engineering point of view [

11], which carefully analyses many details of the energy transition, its conflicting goals, questioning the assumptions made in KND2045 and similar reports that served as a basis for political decision-making.

Most quoted publications are in German language. This has to do with the fact that only the energy transition in Germany is investigated. There are a few publications in international journals, with similar arguments as the cited studies [

12]. An open-access article gives a general overview of the German energy transition without detailed computations [

13].

An interesting investigation has been made for Switzerland [

14]. Only photovoltaics is considered as a renewable energy source. The study investigates three possible storage media, battery storage, hydrogen gas storage, and synthetic hydrocarbons. The authors state clearly that the optimal storage combination greatly depends on the country’s precondition, and they seem to favour the synthetic hydrocarbons as long term storage for Switzerland. This preference is based on documented and comprehensible calculations and also involves economical aspects. A more recent study of the same group has been reported [

15], which came to the conclusion, that the preferrable path to climate neutrality for Switzerland is by means of the construction of 6 new nuclear power plants.

This study has a limited scope and focuses solely on the combined effects of the envisaged expansion of wind and solar energy production in Germany, the expected electricity demand, and the planned expansion of storage systems, mainly batteries and gas storage. To our knowledge, this approach based on real data has only been followed once before by one of us, Björn Peters, in the context of financing storage projects. Unfortunately, it has not been published, except as a brief overview in chapter 2 of his recent book [

16], and in an analysis of the economic effects of nuclear energy in [

17]. Regarding the question of storage size there is a remarkable investigation based on a statistical model of the weather data [

18], with an important practical implication about the sizing of a combinded system of volatile energy production and storage - such a system can only provide a safe base load, when the inflow after downscaling due to storage efficiency is 20% larger than the outflow.

The key result of each scenario in this investigation will be the residual requirements for conventional power generation. The target of the energy transition is to reduce this to 0. All details of grid limitations, startup and shutdown times of power plants, etc., are neglected here. Therefore, the results may be considered too optimistic. As the study is accompanied by an interactive program [

19], it may serve as a tool of communication and fact-checking some relevant issues of the energy transition.

2. Methods and Assumptions

Volatile power sources such as wind and photovoltaics contribute considerably to German electric energy. The detailed energy supply and demand are measured by the Fraunhofer Institute for Solar Energy Systems ISE [

2] at a time resolution of 15-minute intervals.

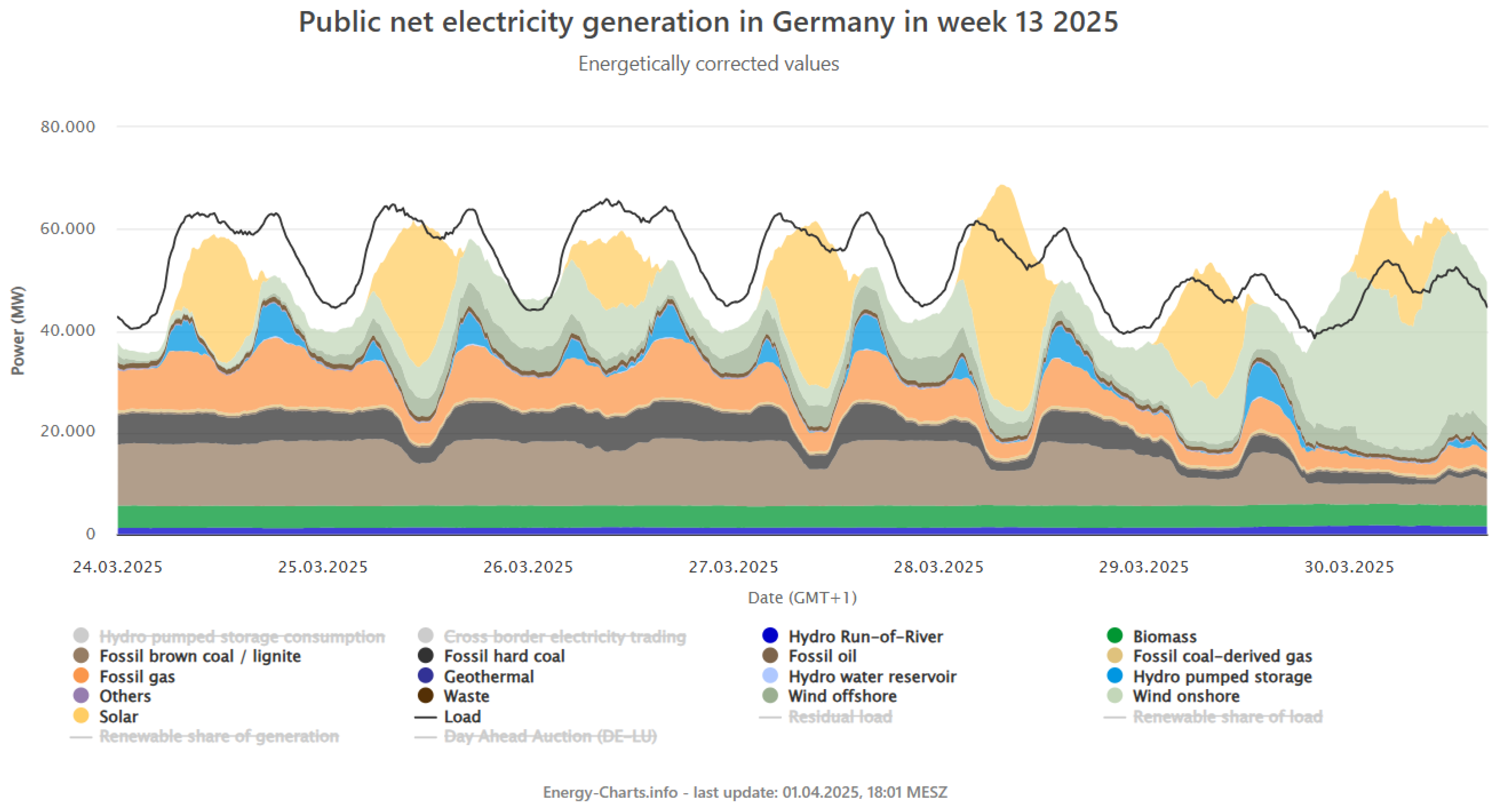

Figure 1 shows the composition of the energy supply and the energy load in week 13 of 2025. The remaining differences between supply and demand were balanced by imports resp. exports.

The energy supply and demand data from the two years 2023 and 2024 serve as a representative dataset, from which the simulation tool will produce new future scenarios while keeping the statistical variability of supply and demand. Since renewable energy has the highest feed-in priority in the German electricity grid, we are fairly safe in the assumption that the provided data are representative of future conditions. Only during times of extreme overproduction has there been a slight deviation from the true supply data, due to rules for switching off PV or wind power plants in times of grid instability.

2.1. Storage System Simulation

For evaluating the cost of the storage system, the costs of all four aspects – capacity, storage efficiency, inflow, and outflow – have to be considered. They differ to a great degree, depending on the specific storage technology. These aspects are discussed in detail for each storage system.

2.1.1. Simulation of Battery Storage

Battery storage is mainly characterized by its storage capacity

. The inflow power

and outflow power

are characterized by the “C”-rating [

20], which relates battery capacity to inflow and outflow power. Typical C-rates for Li-Ion batteries are 0.5–1 W/Wh. A rate of 0.5 means that a battery with 1 kWh capacity can be charged or discharged with 0.5 kW, resulting in a total charge or discharge time of 2 hours.

The price of battery storage is dominantly determined by the amount of energy it can store. Currently, we can assume a price of 100–200 € per kWh capacity, and we use 100 € as an optimistic default setting in the simulation, and assume a life span of 10 years. Inflow and outflow require hardly any conversion effort besides inverters and voltage converters. For this study, we do not assume extra costs for inflow or outflow, assuming that the required grid costs can be neglected, and therefore are included in the price per MWh capacity. The underlying assumption here is that batteries will be installed mainly in a grid-supporting way, i.e., at locations where batteries help overcome grid bottlenecks. This may have to be corrected in the future when large distances have to be bridged for either loading batteries or discharging them.

The short-term efficiency of batteries

can be up to 90%, but long-term measurements confirm the 80% efficiency published by the U.S. Energy Information Administration (EIA) [

21]. We use this value as the default, but the interactive simulation program allows a change of all calculation parameters.

The price of batteries suggests their use as short-term storage, mostly to balance the intra-day volatility. The simulation will show that for large enough storage capacities, enabling long-term storage, costs will explode. Batteries require about 100 full load cycles per year to be financially viable.

2.1.2. Simulation of Chemical Storage by Hydrogen in Caverns

The situation is qualitatively different when using gas as chemical storage. Actual storage capacity comes at a rather low price, and in the case of methane, it has been used for many years in Germany, with a capacity

of appr. 250 chemical TWh [

22]. These caverns can also be partly used for storing hydrogen. The current plans are building this capacity up to 73 TWh [

23]. We do not assume storing hydrogen as a liquid or under pressure, but the framework of the simulator would allow this by adjusting the efficiency and cost fields.

Furthermore, there are two conversions involved. Initially, the hydrogen has to be produced by electrolysis from electric, volatile energy, and when using the energy, hydrogen or methane have to be converted back to electric energy by gas power plants or gas engines. In the case of hydrogen, fuel cells may be an option in some cases. Therefore the inflow is limited by the available electrolysers, and the outflow is limited by the available gas power stations or gas engines.

We do not consider fuel cells here. Although they have a higher efficiency, they are far too expensive for a nationwide scale.

The total chain of conversions imply significant losses at each stage of the process [

24,

25,

26], which are electrolysis, transport, storage, and back-conversion to power, so that total storage efficiency for the most likely hydrogen storage with gas power stations for back-conversion is as low as 13%, but according to other voices could be up to 23% [

10]. Due to the intermittent nature of both electrolysis and back-conversion, the theoretical optimum of the chosen technology can rarely be reached. As a default, we will optimistically use 20% for

in the simulation, but we are aware that this efficiency may be a game-changing factor for the feasibility of the entire concept. As of today, no reliable data is available regarding the long-term and large scale system efficiency. Furthermore, the inflow power is restricted by the available electrolysers, and the outflow power is restricted by the available gas power plants.

The price of storage is composed of the total cost of the electrolysers, which scale with the inflow power, the relatively small cost of the actual storage scaling with storage capacity, and the cost of the gas power stations for generating the electric energy from the stored gas, which is proportional to the maximum outflow [

27]. We apply the rather optimistic value of 1

investment cost with a lifetime of 10 years for electrolysers, 50

as yearly storage costs, and 200

((review)) investment cost with a life span of 20 years for the gas turbines or gas engines. Furthermore, we assume 5% of the total investment as a yearly cost for operations, administration, maintenance, security, and insurance.

2.1.3. Simulation of Pumped Storage

Pumped storage (P) requires a suitable geological constellation with two possible large water reservoirs close to each other but at different heights. In Germany, there is currently a capacity

of appr. 40 GWh [

1], with a maximum inflow power

and a maximum outflow power

. The storage efficiency

is 80%. As there is no room for expanding pumped storage in Germany, the cost of expanding this type of storage (around 150 €/kWh) is not a relevant parameter for our simulation.

2.1.4. Demand-Side Management, Import and Export to the European Grid

There are two more options for energy balancing. The first is demand side management, which means reducing consumption of or switching off large consumers during times of short supply, e.g. aluminum production plants [

22,

28]. This type of flexibility exists in the range of several GW for a maximum of a few hours, and no usable numbers for future estimations exist. In a scenario that avoids massive de-industrialization, we believt that demand-side management will not play a dominant factor. Data centers, metal and ammonia producers, as well as most industry plants, will not be able to stop their activities for days and weeks during longer dark doldrums (dunkelflaute).

Germany exchanges energy through imports and exports with its European neighbours. In recent years, the typical pattern has become that Germany exports at low, even negative, prices when renewable energy sources create an uncontrolled overproduction, and it imports power at high prices when renewable production is low. Since the shutdown of the last nuclear power plants in 2023, Germany has become a net importer of power, while exporting mainly the volatility of German energy production to its European neighbours, creating substantial stress in their grid [

29]. As this situation is unsustainable and cannot be expected to be accepted over longer periods, this investigation does not assume energy imports or exports to be a relevant factor in the future.

2.2. Simulation of the Process

The simulation of the described storage devices and the following process is implemented in an interactive online program [

19]. This includes the preconfigured scenarios described in this paper. The parameters of the process can be adapted easily to simulate new conditions.

The main data to be analyzed are the projected PV power during time unit

i,

, onshore wind power

, and offshore wind power

. We assume a possible change of the mixture relative to the reference year. Therefore, PV power is scaled with factor

a, wind onshore power is scaled with

b, and wind offshore power is scaled with

c. We assume the two other renewable sources, hydropower and bio-fuels, to be a constant term

(currently 7 GW), which is added to the other renewable energy sources:

The power demand during time unit

i is

, where each time unit represents a quarter of an hour. The simulation allows for upscaling the power demand by a factor

d. The underlying assumption of the approach is that the two years 2023 and 2024 are statistically representative for both the variability of renewable power generation and power consumption. To optimally align with the KND2045 study on the energy transformation, the final calculations will be made on the basis of the 2023 measurements. With the availability of the accompanying online tool, tests can be done on the basis of other reference years.

In an electrical grid, the supply – represented by

– should ideally be identical to the demand

at each time interval

i. Their difference

is the volatile discrepancy, the key guiding variable for the storage process. This is split into the surplus component

and the deficit component

Storage aims to bring

as close as possible to 0, which is equivalent to minimizing both the surplus component

as well as the deficit component

. Storage implies that at each time interval

i the energy charge state

of all storage systems is initially updated with their previous charge state, with the initial charge

for

:

. When energy is measured in GWh, power in GW, then with the time unit 0.25h, the energy transferred into the storage system

s with its specific storage efficiency

during time interval

i is

The limiting difference

prevents overcharging of the storage system. By charging the storage, the surplus component of the volatile discrepancy is reduced to

With this equation we assume that the total loss of the storage system happens during charging. The distributed loss in the case of gas storage requires a separate discussion. Discharge happens only when there is a deficit. The discharge energy is restricted by the maximal outflow power from the storage and also by the current charge status – you cannot take out more from a store than its charge:

The deficit power is correspondingly reduced to To adequately consider the different storage systems, a sequence of operations has to be defined. The optimal process is starting from the most established process, which is pumped storage, followed by battery storage. Gas storage is meant to be for long-term storage and is thus the last stage.

2.3. Simplifications in This Investigation

To keep our simulation manageable, many aspects of the complex energy supply system must be neglected. Some of them imply that our scenarios are over-optimistic, some are . These simplifications are the following.

It is assumed that the grid can transfer arbitrary amounts of energy from one location to another – the copper plate assumption – which is known to be much too optimistic [

30]. In reality, the transport of wind energy from the Northern German coast to southern Germany is severely impeded by a lack of grid capacity.

The power generation by hydropower, bioenergy, and waste burning (i.e., must-run capacity) is relatively small and does not vary much with time. They currently deliver a relatively constant amount of 7 GW. This corresponds with their yearly approximate contribution of 60 TWh. They are not assumed to contribute to balancing the volatility of wind and solar energy. Therefore, they are subsumed in a constant contribution, which effectively reduces the energy production by residual sources by a constant amount, the default of which is 7 GW. Ideas to flexibilize the production of bioenergy are being discussed, but is not yet clear when such technologies will be widely available.

Within our model, we assume electrical self-sufficiency of Germany. We thus do not allow for the European grid to balance German energy volatility. This assumption is motivated by considering reactions of Germany’s European neighbours during a period in 2024 when electricity prices exploded on the spot market in the autumn of 2024 because of a German Dunkelflaute exporting power scarcity to its neighbours [

29].

The backup power stations are assumed to react immediately to the volatility. This is not the practice case, but with the growing availability of battery storage, the assumption is acceptable, because of hybridization batteries that can smooth out the starting and stopping process of coal power plants and make gas power plants more efficient, see e.g. [

31].

3. Results

3.1. The Key Scenarios

To make this investigation compatible, we try to align it as much as possible to the key parameters of the KND2045 study, which has been at the foundation of the energy transition [

3].

The milestone years are 2023 as the start, 2030 as an intermediate milestone, and 2045 as the end point of the transition.

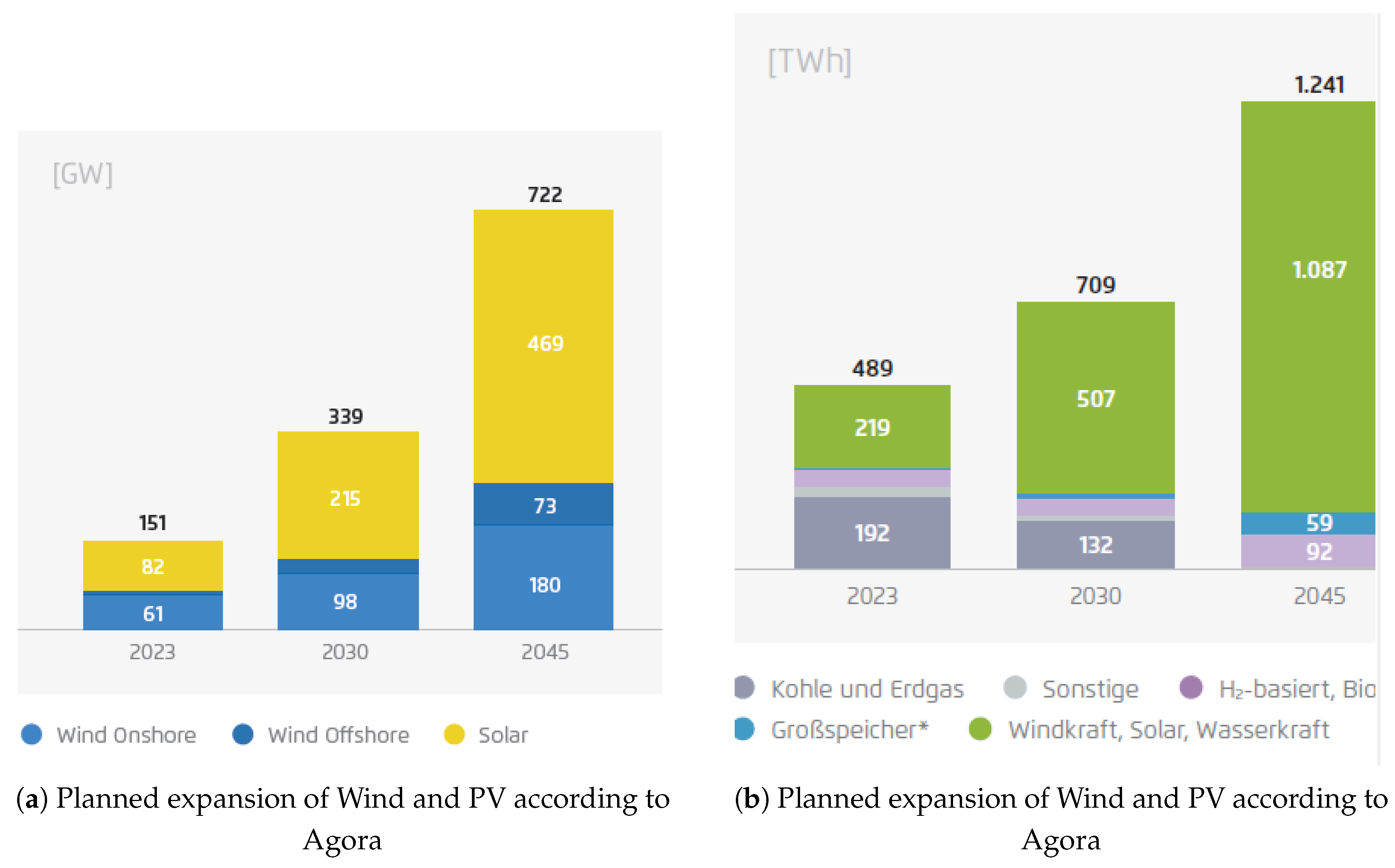

The given or planned installed renewable power is 161 GW in 2023, 339 GW in 2030, and 722 GW in 2045, as displayed in

Figure 2(a).

The expected net energy output is displayed in

Figure 2(b), 489 TWh in 2023, 219 of which are from wind and solar. In 2030, 709 TWh are planned, with a contribution of 509 TWh of renewables. And finally in 2045, 1241 TWh are planned, with 1087 TWh assumed to come from wind and solar. Furthermore, 59 TWh are assumed to come from battery storage, and 92 GWh from gas storage, see the right bar of

Figure 2(b).

3.2. Current Situation

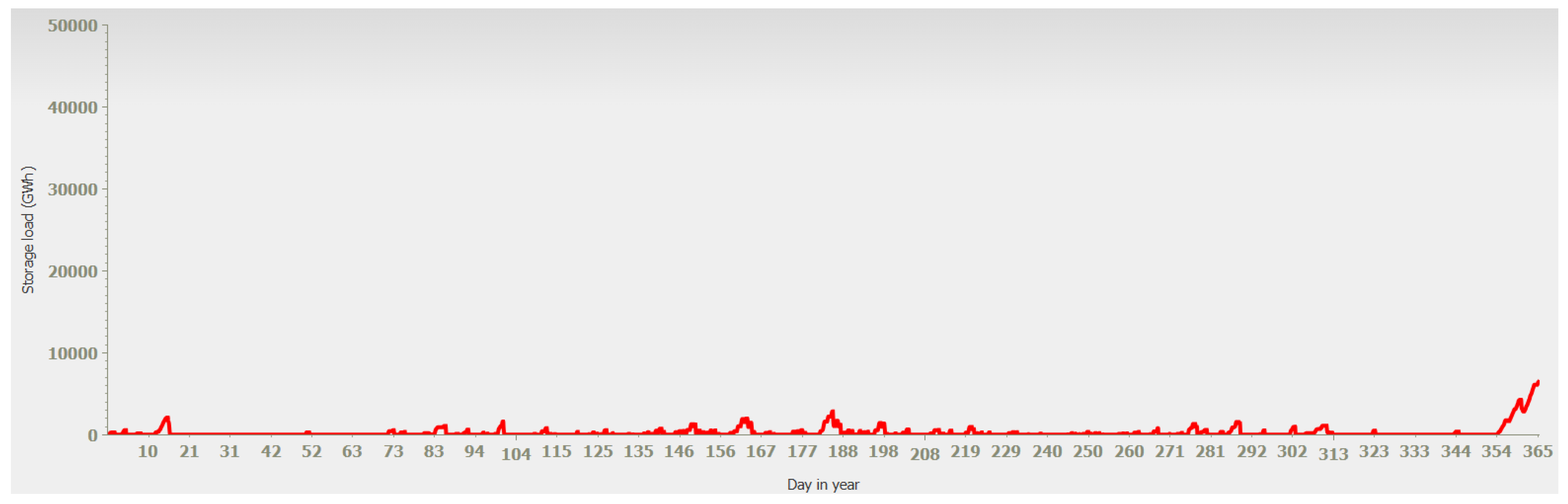

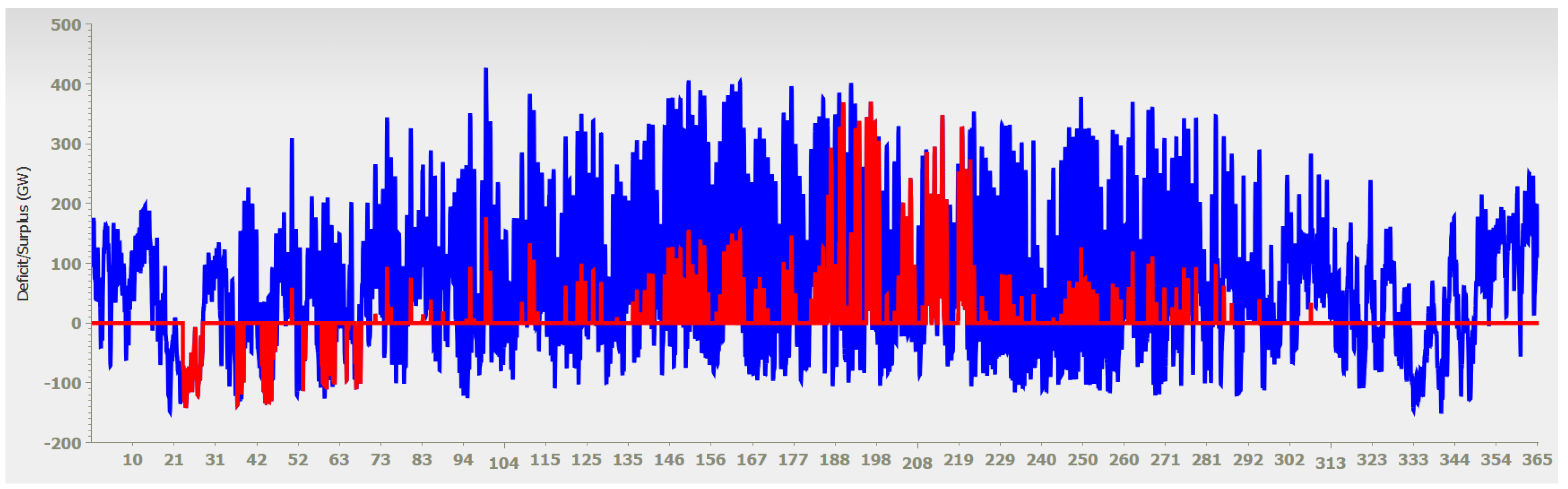

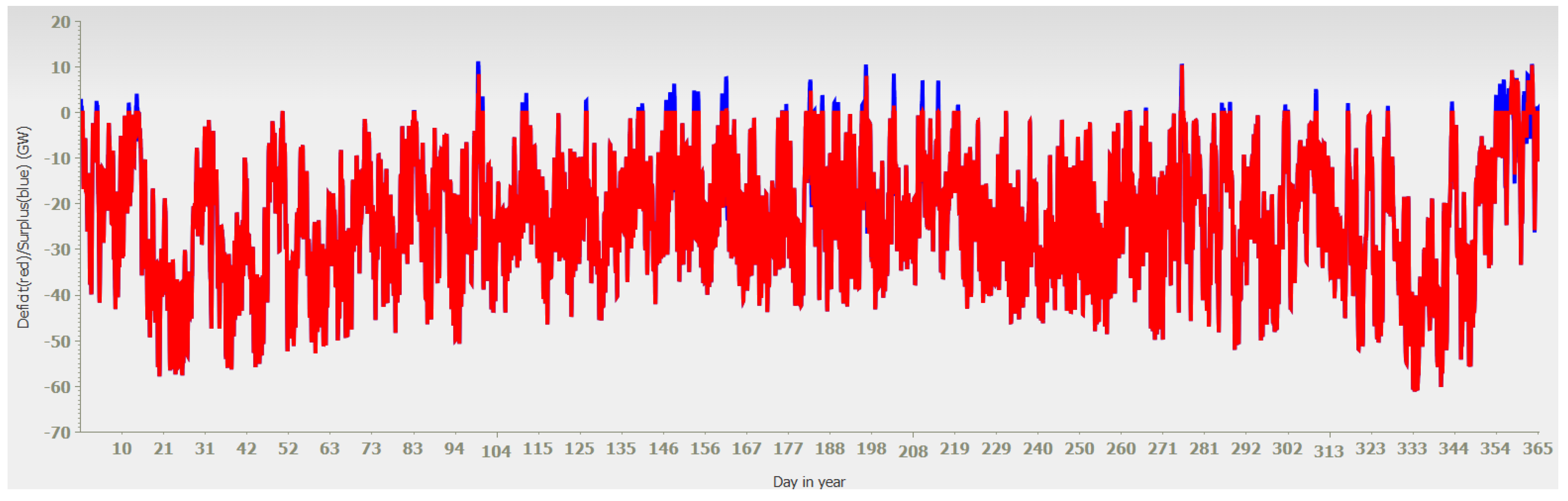

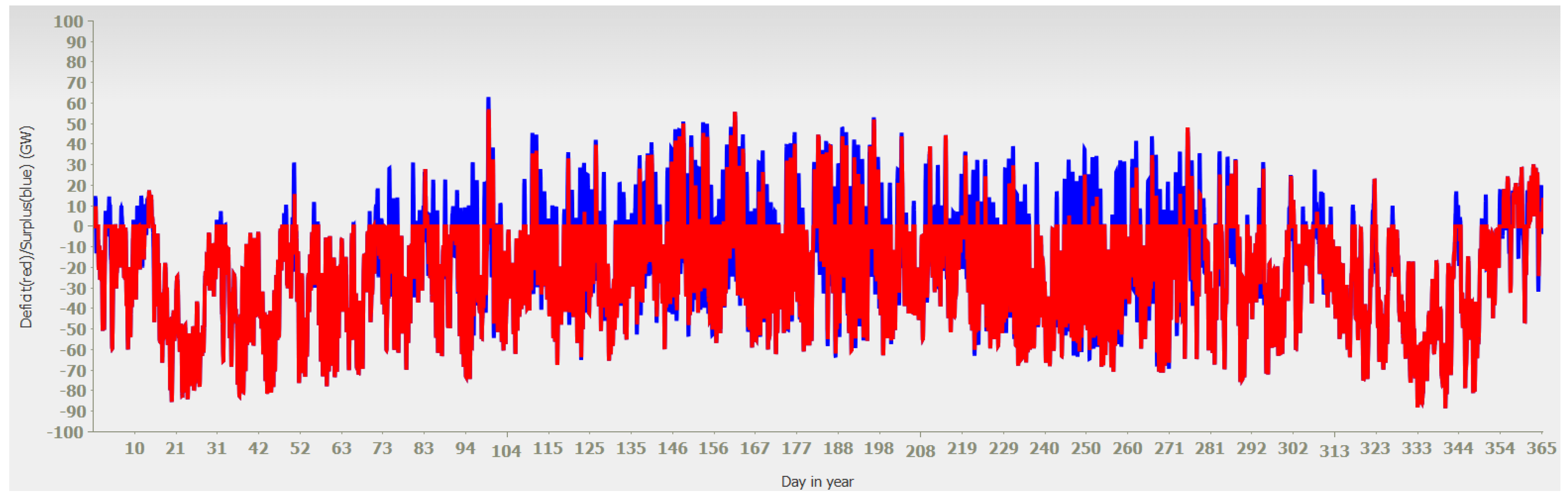

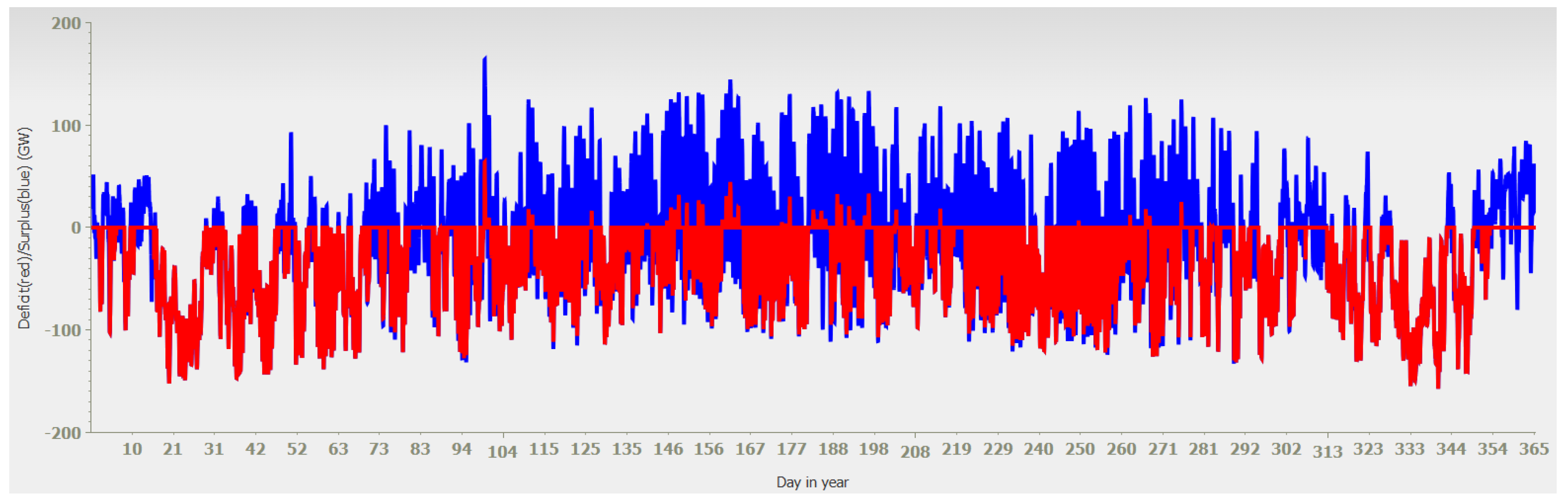

In 2023, the volatile discrepancy was mostly negative as displayed in

Figure 3, i.e., there were hardly any overshoots of renewable supply over demand, theoretically only 86 GWh. In contrast, volatility was substantial, with the volatility discrepancy ranging from +5 to -60 GW. The blue curve in

Figure 1 represents the volatility without storage, whereas the red line considers the existing pumped storage of 50 GWh.

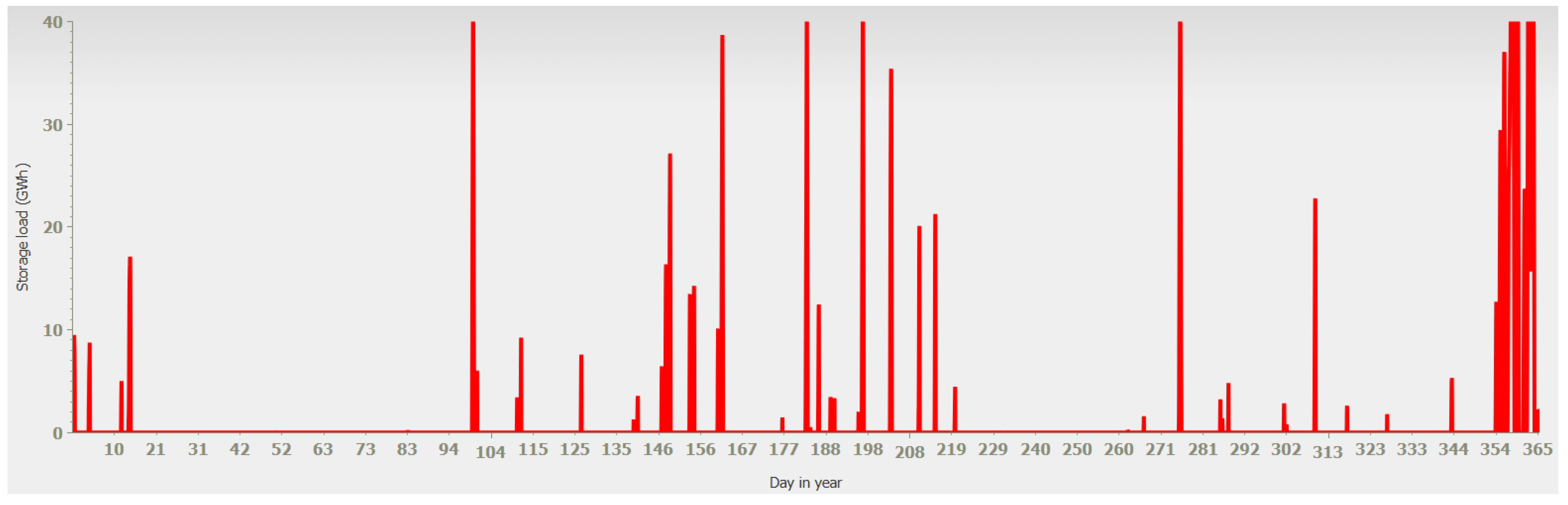

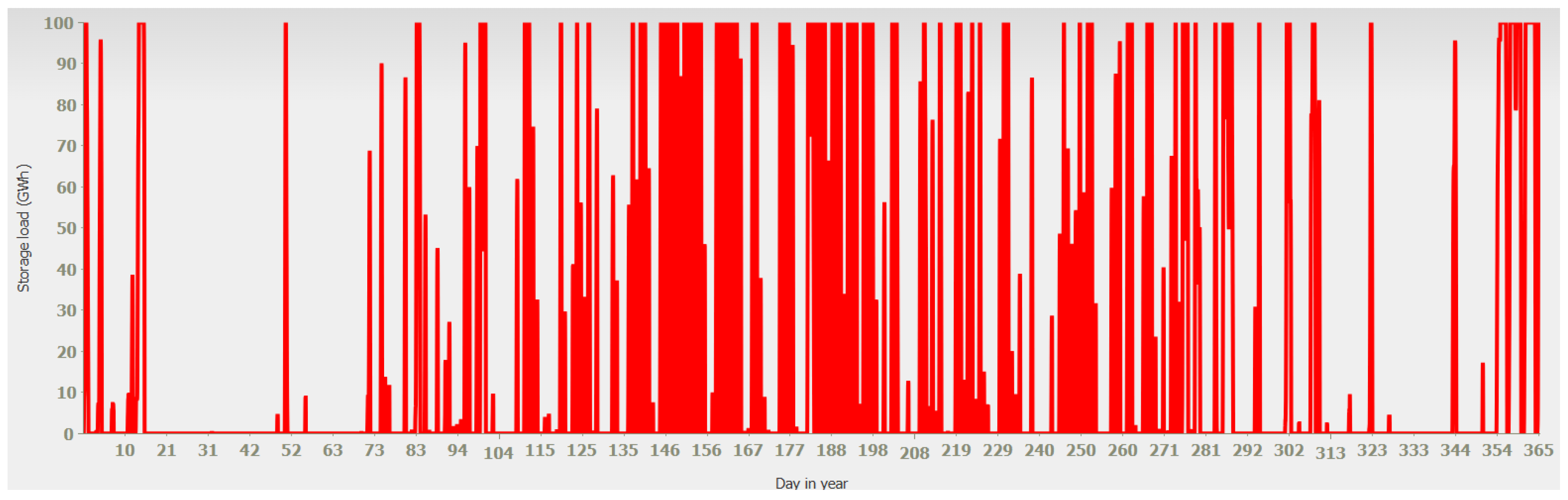

In

Figure 3, blue graph, we see that pumped storage can absorb in principle most of the overshooting RE energy, but for most of the time, there is a systematic deficit of renewable energy. This is reflected in

Figure 4, which shows the load state of the sum of all German pumped storage systems. If pumped storage was filled only by surplus renewable energy, as we postulate in our model, the storage hardly ever gets charged.

Considering that most surplus “overshoots” are absorbed by the pumped storage capacity, there should not have been the necessity to export electricity with negative prices to the European neighbours. But in reality, the conventional power stations, which are balancing the deficit of renewables, cannot reduce their production to more than a third of their nominal capacity. Therefore, the real overshoot of the volatile sources is substantially larger than this diagram suggests, leading to 301 hours of negative prices at the German power exchange in 2023 (increasing to 457 hours in 2024) [

32], section “Wholesale electricity prices”.

The direct contribution of wind and solar is 55%, with hydropower and biofuels this increases to a 62% RE share in 2023, in agreement with the left bar in

Figure 2(a).

The storage charge status is an important characteristic for evaluating the system behaviour. Following the above equations, overshoots are avoided when the storage charge is less than 100%, and deficits are avoided when the storage charge remains larger than 0. Currently, there are no significant battery or gas stores. Therefore, we consider only pumped storage for balancing demand and supply volatility. The existing pumped storage applied only to the renewables has little effect. This is partly explained by the fact that the data from the past is the result of complex grid management aiming at minimizing the gap between supply and demand.

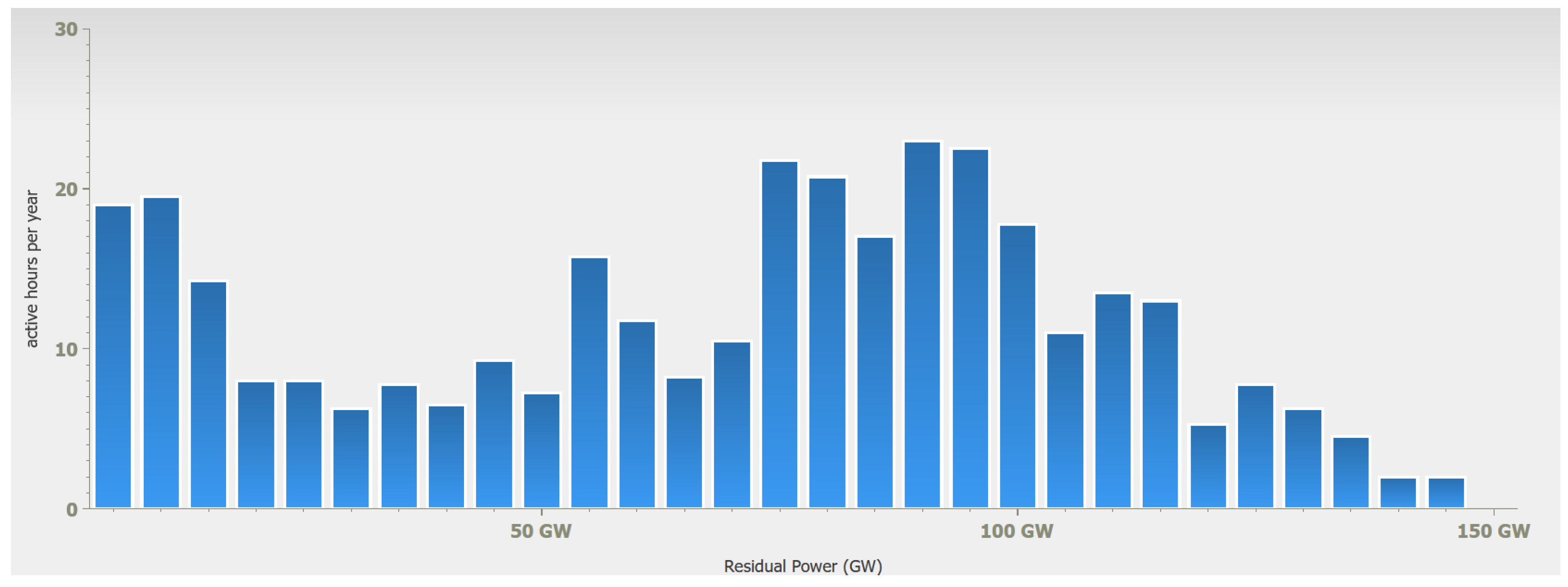

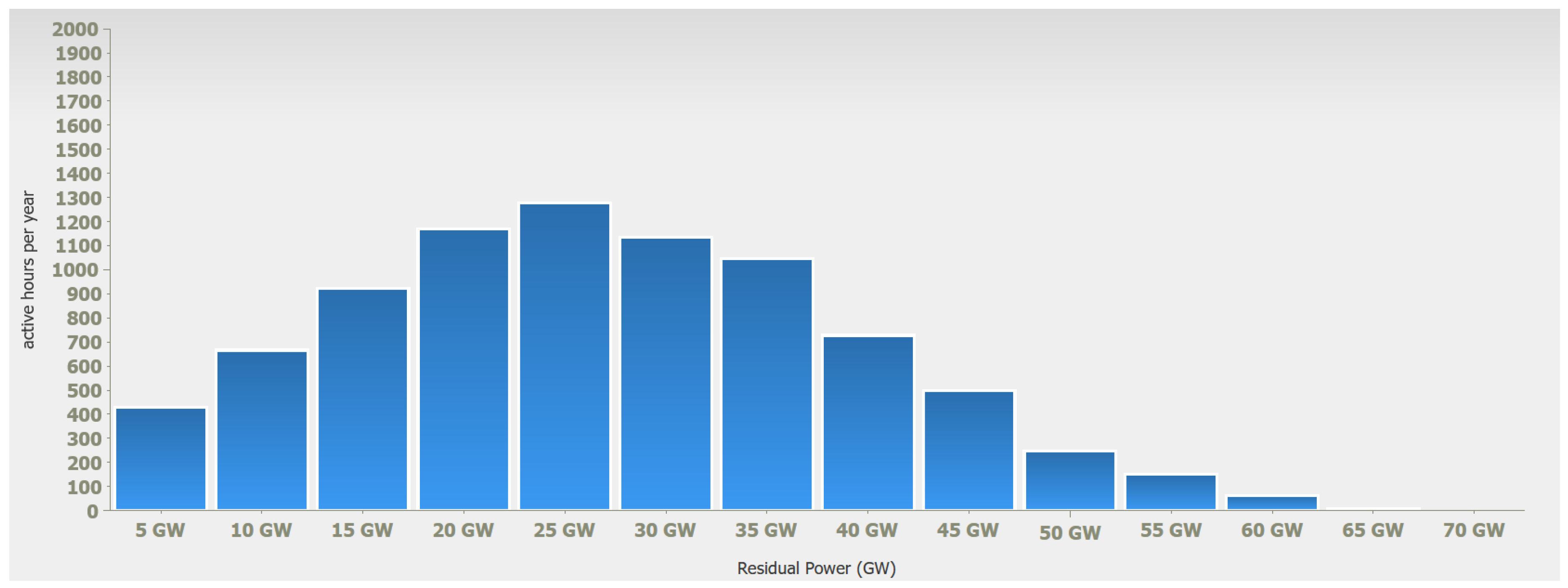

A key question in each scenario is how much residual conventional power is still required. This is shown in

Figure 5.

The overall number matches the value of KND2045 (

Figure 2) quite well. The detailed requirements for the residual power system are displayed as a histogram indicating the number of hours the conventional power stations had to run, as a function of their capacity. The bar on the right determines the maximum power-generating capacity required. In 2023, this used to be 60 GW, operating for some 200 hours a year.

3.3. The Plan for 2030

For constructing the model parameters for 2030 we need to determine the expansion factors for renewable energy and demand. According to

Figure 2(a), middle bar, the planned expansion of photovoltaics is by a factor of 2.6 from 2023 until 2030, wind power offshore by 3.25, and wind power onshore by 1.6. The development of total energy generation and, assumingly, also consumption according to

Figure 2(b) from 2023 (489 TWh) to 2030 (709 TWh) is by a factor of 1.45.

According to the Fraunhofer Institute for solar energy systems (ISE), it is planned to have 100 GWh of battery storage capacity in 2030. Together with the 40 GWh of pumped storage, we can assume a total storage size of 140 GWh. We do not believe that significant gas storage systems will be available by then. Regarding volatility, the overshoot energy is significantly reduced, but far from 0, as shown in

Figure 6. There is hardly any change in the energy deficit situation.

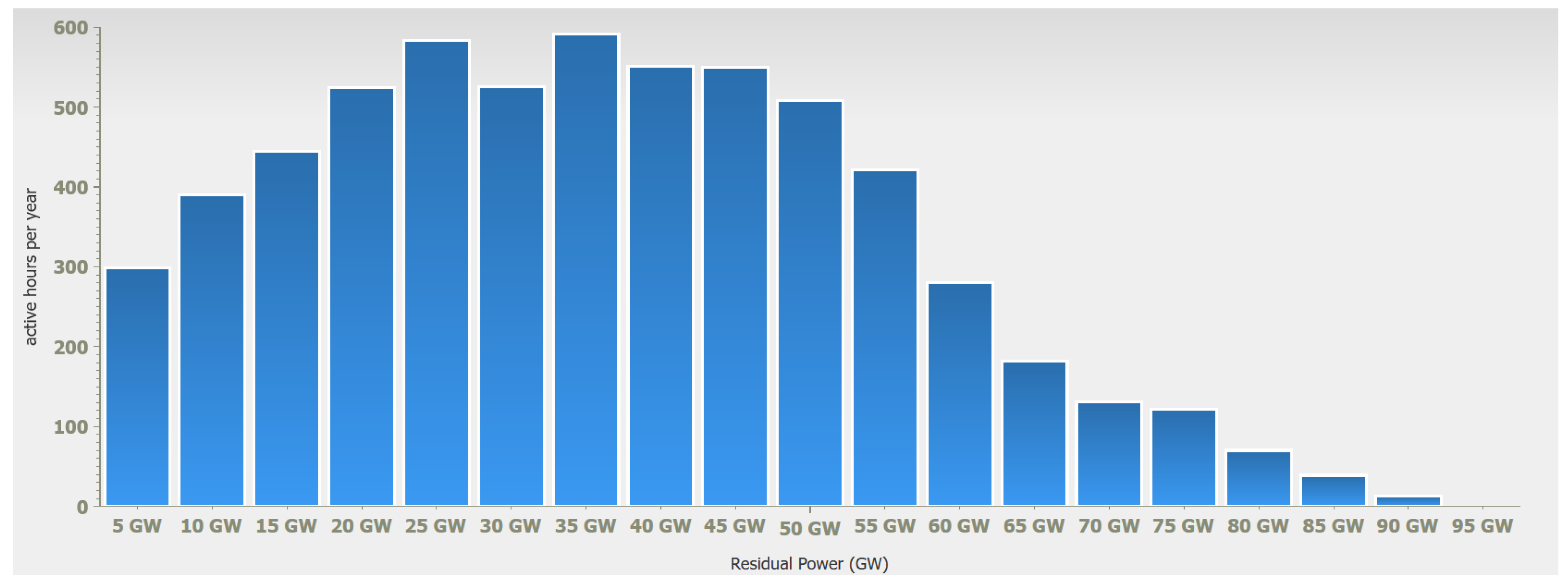

The storage activity according to

Figure 7 has significantly increased compared to 2023.

The degree of direct usage of renewable energy increases to 67%, pumped storage and battery storage deliver together 16 TWh, not 20 TWh as claimed in

Figure 2(b). Both storage types deliver 3% of the energy load, raising the total renewable contribution to 70%. While the absolute deficit has slightly decreased to 196 TWh, the residual power distribution has widened, making simultaneous conventional backup power plants of 85 GW necessary, as shown in

Figure 8.

As a consequence, instead of reducing conventional power plants, in particular coal power plants, it will be necessary to increase their number and availability if the electrification of German society remains the Government’s goal.

3.3.1. Two Options to Cure the Shortfall of the KND2045 Concept

One possibility of reducing the energy load of conventional power plants to the claimed 132 TWh is to increase the factors

a,

b, and

c, which scale the total expansion of solar, wind onshore, and wind offshore, by a factor of 1.35 from the values of

Figure 2(a, factor from first to middle column) to the values

. This is 35% more than claimed by KND2045. It must be noted that even this increase in RE installations doesn’t reduce the requirement of having 85 GW of backup power plants. It just reduces the number of hours of their active operation.

The other possibility of reaching the goal of the reduction of conventional backup power is to reactivate the 8 to 9 nuclear power plants that have recently been shut down [

33]. This would provide a carbon-free base load of 11 GW with better output flexibility (down to 3 GW in 1-2 hours), which is faster than coal power and combined cycle gas power plants allow. Therefore, the conventional backup power plants only need to provide 74 GW.

3.4. Scenario for 2045 – Energy Transformation

2045 is supposed to be the "target year" for completing the energy transition. The Agora plan is to reach 722 GW of installed RE power, of which 469 GW is PV, 180 GW is onshore wind, and 73 GW is offshore wind power. This means that in comparison to 2023, PV has to be expanded by 5.72, wind onshore by 2.95, and wind offshore by 9.13. Electricity demand is expected to increase by a factor of 2.54. The expected renewable energy according to

Figure 2(b) is 1087 TWh, 95 TWh from biomass, hydropower, and geothermal, and 59 TWh from batteries, achieving a total of 1,241 TWh as overall demand. Let’s look at the results. Again, we begin with the volatility graph in

Figure 9.

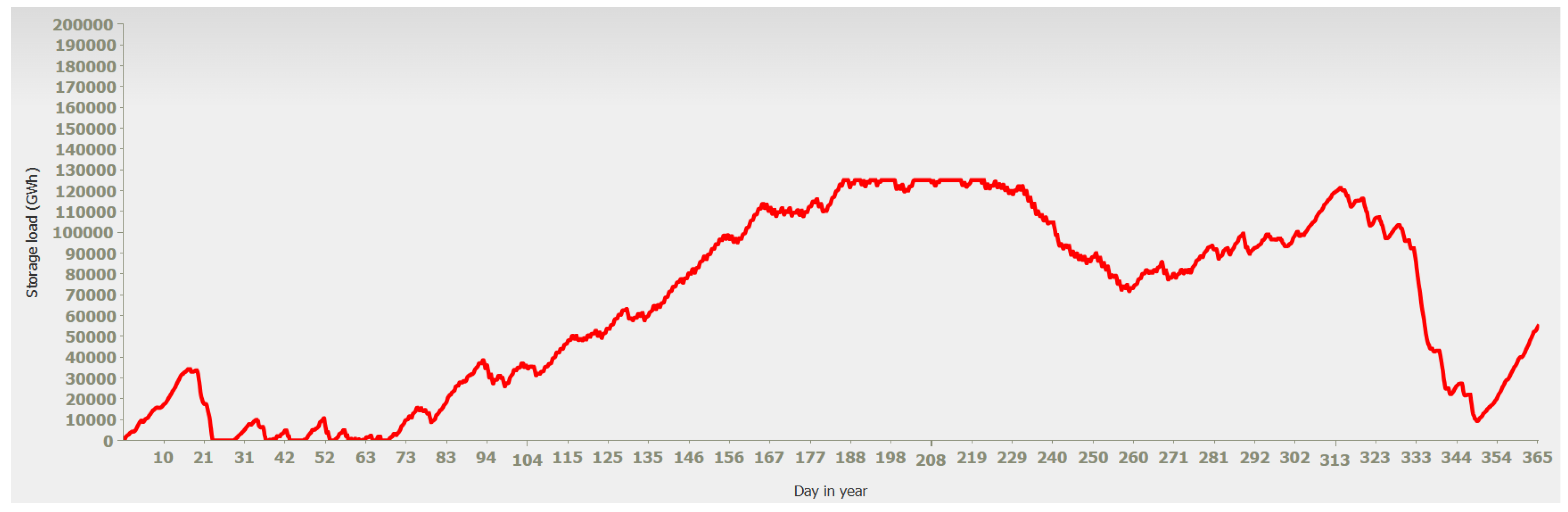

Gas storage of 50 TWh can balance most of the overshoot energy, but there remains a vast deficit. This is confirmed by the gas storage load state for the 2045 scenario:

Figure 10.

Gas storage load state in the 2045 scenario.

Figure 10.

Gas storage load state in the 2045 scenario.

Indeed, the gas storage capacity is unused/empty for most of the time.

The achievable renewable yield under the same statistical conditions as 2023 is 947 TWh, of which 842 TWh are directly usable, that is 72% of the required demand. With the three storage systems, 40 GWh pumped storage (80% storage efficiency), 250 GWh of batteries (80% storage efficiency) and 50 TWh of hydrogen gas storage (20% storage efficiency) most of the 12% unusable overshoot energy is stored, delivering together 54 TWh, adding 5% to a total of 77% renewable supply rate. This is reflected in the conventional backup requirement, which, according to Figure 11, is larger than the one in 2023.

Figure 11.

Required backup power plants in 2045.

Figure 11.

Required backup power plants in 2045.

This is far from the goal of 100% renewable energy supply, falling short by nearly 250 TWh with respect to the self-set goal of 1,100 TWh for an all-electric society. As questionable as the goal may be, compared to the total primary energy consumption of 3000 TWh in 2023, which is already only half of the world average with equal economic performance. Even this extremely reduced goal is not achievable with the proposed concept.

3.4.1. Why Is the Agora Estimation Flawed?

There is one common estimation error, already occurring in 2023, which is only 2 years from the date of the Agora study, and which gets worse for more distant future scenarios. It is the energy yield for a given nominal installation power of both wind and solar. There are several possibilities how this error might have occurred:

Energy yield varies from year to year. Maybe their choice of modeling year, 2012, has been a year of extraordinary energy yield. 2020 was a year of exceptionally high photovoltaic yield. With careful statistics, however, and using different years for the estimation, such errors can be minimized. Ideally, at least 30 consecutive weather years should be used for modeling a strongly weather-dependent energy system! This is especially important when an estimation has so far-reaching consequences.

Could it be that the average wind speed is slowing down in Germany? Considering the official statistics of installed wind power vs. energy yield, it must be noted that the average wind power production is growing considerably slower than the installed nominal power. [

34]. There are many speculations about the possible root cause of this phenomenon, one of which is that the possible extraction of wind power is entering a saturation point ("wind stilling"). A scientific investigation has been made specifically for an important location dedicated to German offshore wind parks. It clearly states that the wake vortices behind wind power plants can be detectable as far as 20 to 100 km behind wind parks, where turbulence is reducing the usable wind energy much more than would be expected by the amount of energy extracted by the wind power plant. The paper summarizes that "The extractable energy per wind turbine is much smaller for large wind farms than for small wind farms due to the reduced wind speed inside the wind farms". With the high density of wind power plants near the North Sea coast and in Eastern Germany, it is not surprising that additional wind power plants take away a significant fraction of the energy that other wind power plants produce.

In this investigation, we ignore electric grid constraints. It is, however, an obvious fact that wind power plants in northern Germany often have to be shut down because there is an energy surplus locally, while in southern Germany, there is an energy deficit. The grid bandwidth between Northern and South Germany is far too small and can not be extended easily: Immense costs and social resistance are still delaying the further construction of a powerful north-south power link.

An important factor is that institutions involved in discussing the energy transition are not independent but have a financial interest in its implementation. Such a lobby attitude might foster ignorance over critical issues and problems, most importantly when critical voices are systematically ignored or silenced, as frequently happens in the German public discussion. Notwithstanding, the whole country will have to bear the consequences of decisions based on such questionable estimations.

3.4.2. Is There a Bridge Between KND2045 and the Real World?

Technically, with the simulation tool the extreme shortfalls of KND2045 could be bridged in a similar way as we have done in the 2030 scenario, by substantial overbuild, approximately doubling the photovoltaics as well as both wind installations, using the factors , and . Additionally, gas storage would need to be be enlarged to 150 TWh and there would have to be 250 GW of electrolysers, providing the input energy into the gas storage. Even then there would be a few days when the demand is higher than the supply, see Figure 12 and Figure 13. The direct supply of RE together with the stored supply only reach 98% of the demand. The residual load requires gas power stations with power up to 120 GW, as displayed in Figure 14. Due to the fact that the storage requirements demand 120 GW of gas power stations, these would also be used as backup. Their fuel would have to be provided from abroad.

Figure 12.

Volatility of the adapted renewable energy scenario for 2045.

Figure 12.

Volatility of the adapted renewable energy scenario for 2045.

Figure 13.

Gas storage load state of the adapted renewable.

Figure 13.

Gas storage load state of the adapted renewable.

Figure 14.

Required backup power for the adapted renewable energy scenario.

Figure 14.

Required backup power for the adapted renewable energy scenario.

From the online tool [

19] we observe that the storage and production subsidy cost per MWh rise with the renewable installed power.

We believe that several severe environmental concerns and wind stilling will make such a scenario prohibitive.

From the online tool follows that the production price of electricity is more than 250 /MWh. In a world, where many countries remain focussed on affordable power prices between 30 and 50 /MWh, such a value is prohibitively expensive. The obvious argument that subsidies, which are the main price driver, should be cut, is easily met with the fact that nobody would invest in wind farms if there were no subsidies.

The immense expansion of technologies with such a small areal energy density as solar and wind damands huge areas of land. There is growing resistance in the population against the industrialisation of nature, in particular when it comes to new wind farms. There is hardly a project where there is not a lot of resistance from the population against it.

The relatively short life span of devices for renewable energy – from 10 to 25 years – implies that they have to be replaced on such time span. Vast amounts of resources such as rare earth minerals, which are not readily available, would be required.

A technology that requires vast amounts of subsidies more than 35 years after its introduction raises doubts if this is an economically sustainable path into the future. In 2024, the operational subsidies for wind and solar plants have amounted to approximately 20 Billion Euros of German taxpayer money.

4. Discussion

The purpose of this investigation was to introduce a solid computational foundation into the discussion about the German energy transition. When plans are made, they should be based on diligence, facts, resource projections, time estimates, and a thorough risk assessment.

We found out a few critical issues that should find serious consideration in the decision-making processes to come.

The first point is that attention should be given to a reliable relation between installed solar or wind power and the expected energy production. We are not claiming that our projection is absolutely correct, but we are claiming that it is within a 30% error margin. Therefore its predictions must be considered. So this investigation may invite to build future projections on a broad statistical basis, which will then predict an expected value and a variance of it.

Gradually the understanding grows that weather-dependent volatility may lead to either extreme overproduction or close to zero yield for nearly arbitrarily long times respectively. This phenomenon is known from turbulent processes, and the weather is such a hard-to-predict turbulent process. The decisions to turn off more and more conventional power stations in the hope of replacing them with weather-dependent power plants combined with batteries will is questionable. As we showed in this paper, affordable batteries can only bridge rather small gaps, typically a few hours. A battery needs to have more than 100 full load cyles per year to be economically viable. This forbids by definition battery storage for more than 3 days. Even with the extremely large gas batteries of 100 TWh or more there is still the need for backup power stations. They may need to be swichted on for a few hours and again, but unless these hours are covered by a power plant, someone is not gettng the required electric energy, potentially causing a catastrophic standstill of society.

With the provided interactive Companion tool [

19], we hope to contribute to a reality- and fact-based discussion. Each parameter can be adjusted by the user, so different information about costs or other parameters can quickly be incorporated. So the tool can serve as a constructive medium of qualified conversation, and may help decision makers to get answers from a transparent context.

We have identified a fundamental problem – the gaps in the electricity supply of an all-electric future society cannot be bridged by weather-dependent energy combined with storage devices. So what can we do about this seemingly unsolvable problem? We have indicated the way out in the discussion of the 2030 scenario. Fact is, we cannot resolve the problems of 2045 today. But we know how to solve the same type of problem that already becomes apparent in 2030. The least-cost solution to bridge the power gap within the KND2045 scenario in 2030 is the reactivation of 8 to 9 nuclear power plants that were recently shut down. All 9 nuclear power plants can be reactivated for the amount of 1 year of RE subsidies. They will make it possible to reach the 2030 goal.

Maybe we will have a different perspective then, possibly on new technologies, such as carbon capture and storage for existing coal power plant, domestic gas production, or more fundamentally the carbon reduction targets.

I would be wise not to block new energy options by destroy the existing ones.

And the most important question – whether Germany can survive as an industrialized nation – can be derived from neither the KND2045 nor our study. Should severe doubts arise on the latter question, it can be assumed that the German electorate will vote political forces into power that make substantial changes to current energy policies.