1. Introduction

The construction industry plays a pivotal role in the global economy, accounting for 10-12% of the global economic output and providing substantial employment opportunities (Domljan and Domljan, 2024). This sector not only drives significant economic activity but also consumes about 50% of the total use of raw materials and 36% of the global final energy use, highlighting its massive resource demand (Norouzi et al., 2021). The substantial consumption of resources by the construction industry is coupled with high waste production, making it one of the primary contributors to environmental degradation. Specifically, construction and demolition activities are responsible for approximately one-third of the total waste generated in the EU, much of which ends up in landfills, creating serious environmental problems (Elhegazy et al., 2023). This high level of resource consumption and waste production underscores the industry's profound environmental impact, necessitating a shift towards sustainability. In response, recent international agreements and policies are pressing for the adoption of 'net zero' and sustainability-focused practices, aiming to align the industry with global environmental targets (Bulkeley et al., 2023). These initiatives emphasize the adoption of innovative, green building techniques and materials, which are essential for transforming construction into a more environmentally responsible sector.

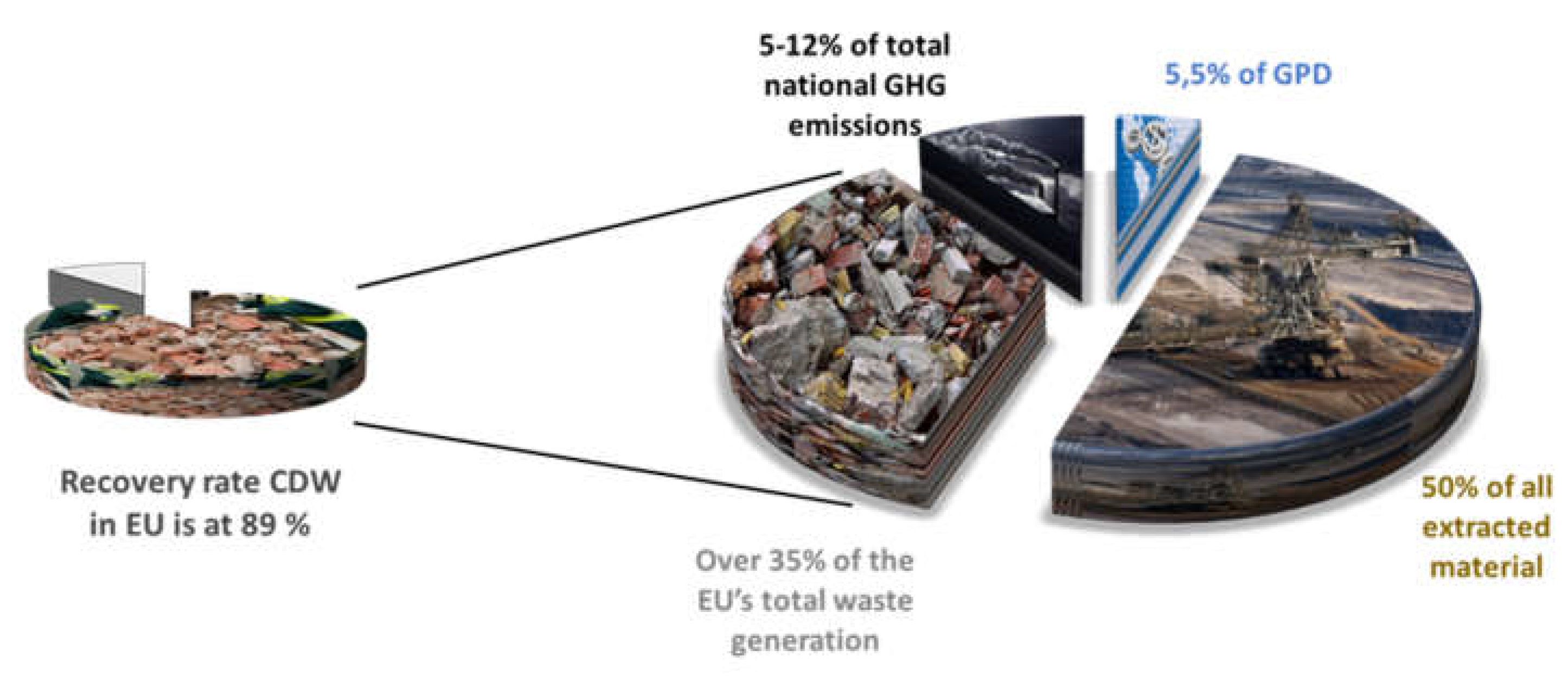

Figure 1 shows key figures related to the construction sector, emphasizing its global economic importance and environmental impact.

The concept of a circular economy is particularly relevant in this context, offering a model where resource input, waste, emission, and energy leakage are minimized by slowing, closing, and narrowing material and energy loops (Husgafvel and Sakaguchi, 2023). This can be achieved through long-lasting design, maintenance, repair, reuse, remanufacturing, refurbishing, and recycling. In the construction sector, applying these principles means rethinking how building materials are sourced, processed, and utilized. Particularly noteworthy are the materials derived from construction and demolition processes. Recycled concrete, for example, demonstrates not only environmental but also economic viability, potentially offering a net benefit of approximately 31 million US dollars per year through resource conservation and energy reductions (Purchase et al., 2022). Other recycled materials such as ceramics are also being integrated to enhance the properties of construction materials, further promoting sustainability (Xu et al., 2023). The inclusion of recycled glass, known for its thermal insulation properties, contributes significantly to energy savings in buildings (Cozzarini et al., 2023). Additionally, the use of recycled PET and marble waste in concrete has shown promise in enhancing compressive and flexural strengths while reducing water absorption, illustrating the diverse possibilities of using recycled materials in construction (Bostanci, 2020). These practices not only support resource efficiency but also contribute to the sector's shift towards environmental conservation (Papamichael et al., 2023).

Beyond the specific challenges associated with construction and demolition waste (CDW), the escalating impacts of climate change and resource depletion amplify the urgency to adopt more sustainable practices across all sectors. This transition focuses particularly on the utilization of secondary materials from a variety of sectors—resources that were once considered waste but are now recognized for their potential to reduce the industry's environmental footprint. Among these materials, cellulose waste, mining tailings and metallurgy slags are particularly noteworthy due to their abundance and the significant volume of waste they represent. In 2022, approximately 265.7 million tons of cellulose pulp were produced globally, which were transformed into 430.5 million tons of paper and cardboard (Valois, 2024). This production reflects the widespread availability of cellulose as a secondary material, which can be recycled and used in new manufacturing contexts. Mining tailings, which are the waste materials remaining after the processing and separation of the valuable fractions of an ore, are generated in a range of 5–7 billion tons per year throughout the world (Bamigboye et al., 2021). This vast quantity of tailings presents significant environmental challenges and opportunities for reuse. In the case of slags, according to statistics, just from steel slags alone, the world produces about 190 to 290 million tons every year (Ji et al., 2022), and much of this byproduct is either left in open-air stockpiles or disposed of in landfills. These data clearly demonstrate that these materials are generated in vast quantities globally, with millions of tons produced annually, posing serious environmental challenges but also presenting substantial opportunities for reuse within the construction industry. Their reuse can significantly reduce the reliance on virgin materials, decrease landfill use, and promote greater resource efficiency.

Sourced from segments like paper manufacturing, agricultural production, textile industry and wastewater treatment plants, cellulose waste offers unique characteristics that are ideal for various building materials (Rbihi et al., 2024; Wang et al., 2021). In the paper industry, cellulose waste mainly originates from the sludge produced during papermaking. This sludge is rich in high-quality cellulose fibers, which are increasingly being repurposed to manufacture eco-cement (Kumar and Verma, 2024), insulation panels and fiberboards (Kethiri et al., 2024). These products are prized for their excellent thermal and acoustic properties, aligning well with modern building standards that prioritize energy efficiency. Agricultural residues such as straw, hemp, and bagasse also serve as valuable sources of cellulose waste. These materials can be transformed into composites used for wall panels, roofing, and flooring solutions, leveraging their lightweight and durable nature for eco-friendly construction projects (Khalife et al., 2024). For example, hempcrete, a composite made from hemp fibers and lime, is renowned for its sustainability, excellent thermal insulation, and moisture-regulating properties, making it a superior alternative to conventional building materials (Sharma et al., 2024). Additionally, textile waste, particularly from cotton and linen, provides another substantial source of cellulose. Recycled fabrics can be processed into fibers that enhance the mechanical properties of concrete, such as tensile strength and durability, thereby extending the lifespan of concrete structures and contributing to more sustainable construction practices (Baloyi et al., 2024).

In addition to the applications mentioned for cellulose waste, mining tailings are also finding a valuable place in the construction industry. Traditionally seen as an environmental issue due to their management and storage, these residues are being transformed into useful resources for building infrastructure. For instance, tailings can be processed to create lightweight aggregates used in concrete blocks and tiles, offering a sustainable alternative to conventional materials and reducing the extraction of virgin natural resources (Yang et al., 2022). Their ability to enhance the thermal and acoustic insulation properties of construction materials also makes them an attractive option for projects aimed at improving energy efficiency in buildings (Deng et al., 2023). Furthermore, soil stabilization with tailings has proven effective for constructing roads and other infrastructure, providing a solid and durable base that can withstand adverse weather conditions and heavy use (Lage et al., 2024).

Similarly, slags from the mining and metallurgy industry, previously regarded only as a byproduct to be disposed of, are now being explored for their potential in producing concrete, road foundations, and other structural materials (Kurniati et al., 2023). These applications not only help in reducing the environmental impact associated with the extraction and processing of virgin materials but also support global sustainability goals by lowering emissions and reducing resource depletion (Meshram et al., 2023). Originating from the intensive activities of the mining sector and the metal smelting processes in the metallurgy industry, slag is now recognized for its robust properties such as durability and thermal resistance, making it highly suitable for construction uses (Ramón-Álvarez et al., 2024). For example, copper slag, a byproduct of the copper smelting process, has been effectively utilized as a partial replacement for sand in concrete and mortar mixtures. This substitution not only helps conserve natural sand reserves but also enhances the strength and durability of the concrete due to the higher hardness of copper slag compared to traditional sand (Wang et al., 2023). Another innovative application is the use of slag from nickel and platinum processing for road construction. The high density and abrasiveness of this slag make it an ideal material for high-traffic road surfaces, offering better longevity and less maintenance than conventional materials (Gaus et al., 2024). These progressive uses of mining slag demonstrate the broad potential of these materials to contribute to more sustainable construction practices and resource management.

These practices enhance both the environmental and economic efficiency of the sectors involved by turning waste into wealth and reducing the overall industrial footprint. However, the integration of these secondary materials into mainstream construction practices is not without challenges. Economic feasibility, technological limitations, and regulatory frameworks often act as barriers to the widespread adoption of these innovative practices (Ababio and Lu, 2023). This review will examine these challenges, exploring the technological innovations that facilitate the recovery and reuse of these materials, and discuss the strategies needed to overcome existing barriers. Despite the growing body of literature on the use of secondary materials in construction, this review aims to bridge gaps by providing a novel synthesis of up-to-date technological innovations, comprehensive economic analyses, and current regulatory frameworks. By doing so, it endeavors to shed light on the multifaceted benefits and the transformative potential of these materials, ultimately contributing to the evolution of a more sustainable and circular construction industry.

2. The Role of Cellulose Waste in Sustainable Construction

Cellulose waste is emerging as a critical resource in the field of sustainable construction practices, offering a renewable and abundant alternative to traditional building materials. Derived from various industrial processes, cellulose waste has the potential to be repurposed into a wide range of construction materials that contribute to reducing the environmental impact of the building industry (Jing et al., 2024). By leveraging the inherent properties of cellulose - such as its strength, durability, and thermal insulation capabilities - innovative applications are being developed that not only improve material efficiency but also support the principles of a circular economy. The utilization of cellulose waste in construction can be categorized into several key areas, each demonstrating unique advantages and applications. These include the development of cellulose-based composites and bio-based materials, the production of high-performance insulation products, and the creation of sustainable concrete alternatives, as summarized in

Table 1. Each of these applications harnesses the potential of cellulose waste to enhance the sustainability of construction practices, reduce reliance on non-renewable resources, and contribute to a more eco-friendly-built environment. The following sub-sections will explore these applications in detail.

2.1. Cellulose-Based Composites and Bio-Based Materials

Cellulose waste serves as a fundamental building block in the development of advanced composites and bio-based materials that are gaining traction in the construction industry. These materials leverage the natural properties of cellulose, such as its high tensile strength, biodegradability, and renewability, to create alternatives to conventional, often synthetic, building materials. Agricultural residues, such as straw and hemp, are particularly valuable in this context. Straw-based panels, for example, offer a sustainable alternative to traditional wood products. These panels are lightweight, durable, and can be produced with minimal energy input, significantly reducing the environmental impact associated with conventional wood processing. Furthermore, these insulating panels exhibit a high specific heat capacity of over 1600 J/(kg·K), leading to a volumetric specific heat capacity of approximately 0.35 MJ/(m³·K), despite their low density of around 210 kg/m³, enhancing their thermal performance and making them highly efficient for energy conservation in buildings (Czajkowski et al., 2022). Hemp fibers, combined with lime, are used to create hempcrete, a biocomposite that is highly valued for its excellent thermal insulation, moisture regulation, and carbon-sequestration capabilities. Hempcrete not only serves as a sustainable alternative to conventional construction materials but also contributes to reducing the carbon footprint of buildings, as the hemp plant absorbs significant amounts of CO₂ during its growth, effectively capturing carbon that remains stored in the building material (Parmar et al., 2024). Furthermore, hempcrete is a carbon-negative material itself; for example, 1 m² of hemp–lime wall (260 mm thick) requires 370–394 MJ of energy for production and sequesters 14–35 kg of CO₂ over its 100-year lifespan, compared to an equivalent Portland cement concrete wall that requires 560 MJ of energy and releases 52.3 kg of CO₂ (Walker and Pavía, 2014). Additionally, hemp-silica panels have demonstrated a thermal conductivity of 0.101 W/mK and an excellent moisture buffering value of 3.49, further enhancing their suitability for energy-efficient and moisture-regulating construction applications (Ayati et al., 2024). Cellulose from textile waste, particularly recycled cotton and linen, is being repurposed into fibers that enhance the mechanical properties of construction materials (Fernando et al., 2023). These fibers are used in concrete and other composites to improve tensile strength and durability, offering a sustainable solution for managing textile waste while contributing to the development of more resilient and long-lasting building products. Nonwoven composites produced from textile waste have demonstrated excellent acoustic and thermal performance. With air flow resistivity lower than 100 kN s/m⁴, these materials achieve sound absorption coefficients higher than 0.6 starting at 500 Hz for 2.5 cm thick panels. Their thermal conductivity, lower than 0.05 W/(m·K), also makes them an ideal choice for improving the energy efficiency of building envelopes, contributing to both indoor comfort and sustainability (Rubino et al., 2023).

2.2. Cellulose Insulation Products

Cellulose waste is increasingly being utilized to produce highly effective insulation products, which align with the growing demand for energy-efficient building solutions. Derived from recycled paper (Abdulmunem et al., 2013), agricultural residues (Sangmesh et al., 2023), and even textile waste (Ayed et al., 2023), cellulose-based insulation materials are treated and processed to create products that can be used in various insulation applications. The natural properties of cellulose fibers, when processed appropriately, result in insulation materials that significantly reduce heat transfer, thereby improving the energy efficiency of buildings (Petcu et al., 2023). This is especially critical in sustainable construction, where reducing the energy required for heating and cooling is a key objective. In addition to their thermal properties, cellulose insulation products derived from both paper and agricultural waste offer excellent soundproofing capabilities (Song and Ripoll, 2023). This makes them ideal for use in a wide range of building types, from residential homes to commercial spaces. Moreover, these materials can be treated with non-toxic fire retardants, making them a safer and more environmentally friendly alternative to conventional insulation products that often rely on harmful chemicals (Jefferson et al., 2024).

A study carried out by Wand and Wang (2023), set in the context of the UK's climate and landfill crises, explored the potential of cellulose derived from recycled paper as an insulating material to address the country’s inadequate recycling rates. In a case study of the retrofit and new-build project in London, their research examined the performance of cellulose insulation compared to other conventional materials. The findings showed that, although cellulose insulation from recycled paper may not offer the highest thermal performance, it meets the requirements for most applications. Furthermore, this type of cellulose insulation emits significantly less carbon dioxide over its life cycle compared to other insulation materials, making it a highly sustainable option. While traditional paper recycling can sometimes result in lower carbon emissions, converting waste paper into cellulose insulation presents a viable alternative that not only improves the recycling rate but also provides sufficient insulation for energy-efficient buildings. In exploring the use of agricultural waste for construction insulation, several innovative cases demonstrate both environmental and functional viability. For instance, insulation boards made from pineapple leaves have shown thermal conductivity values between 0.043 and 0.057 W/mK, highlighting their potential as effective and sustainable insulation materials (Ali et al., 2024). Similarly, boards crafted from coconut husk and bagasse—by-products of coconut and sugar production - employ no chemical binders and exhibit thermal conductivity values ranging from 0.046 to 0.068 W/mK, underscoring their eco-friendliness (Rodríguez et al, 2024). Additionally, innovative boards combining wheat bran and banana peels offer promising properties suitable for building applications, with thermal conductivity ranging between 0.050 and 0.066 W/m·K and mechanical properties comparable to those of commercial insulation boards (Di Canto et al., 2023). Agricultural cellulose sources, such as straw and hemp, are also particularly effective in creating insulation products that offer superior thermal performance. For example, hemp-based lightweight concrete exhibits a thermal conductivity of 0.09 W/m·K, while straw-based concretes show values as low as 0.078 W/m·K, making both materials excellent options for thermal insulation in sustainable construction (Babenko et al., 2022). These examples showcase how agricultural residues can be transformed into valuable, sustainable building materials, contributing to reduced environmental impact and enhanced building performance. Textile waste, which includes discarded garments, industrial scraps, and end-of-life textile products, provides a rich source of cellulose fibers that can be repurposed into high-quality insulation. Textile-based cellulose insulation is particularly valued for its excellent thermal properties, moreover, these materials can be treated to offer fire resistance and reduce noise pollution, making them suitable for a wide range of applications in both residential and commercial construction (Agnihotri et al., 2024). One notable example is the initiative carried out by Samardzioska et al. (2023), which effectively demonstrated that insulation material made from recycled textile waste can achieve a thermal conductivity as low as 0.039 W/m·K. This level of performance makes it highly competitive with traditional insulation options, emphasizing its potential to improve energy efficiency in buildings significantly.

2.3. Sustainable Concrete Alternatives

The construction industry is also exploring the use of cellulose waste in the development of sustainable concrete alternatives. Traditional concrete, while essential for modern construction, has a significant environmental footprint, particularly due to the high carbon emissions associated with cement production. By incorporating cellulose fibers, including those derived from waste streams, into concrete, researchers and engineers aim to develop materials that maintain the strength and durability of conventional concrete while reducing its environmental impact. Rhihi et al. (2024) used cellulose fibers as additives in concrete blocks to enhance their insulation properties, specifically improving their ability to limit heat transfer. Unlike other fillers, such as rubber particles, which can reduce the thermal insulating performance of cementitious composites, the use of cellulose fibers offers an ecological and environmentally sustainable alternative. Experimental results demonstrated that the incorporation of bio-cellulose significantly impacts the porous matrix structure, effectively reducing heat transfer and thermal conductivity. Cellulose-based composites can achieve thermal conductivities as low as 0.20 W/mK, which can be further optimized to 0.15 W/mK under specific conditions, such as temperature and the use of condensed phosphates. Similarly, Salahuddin (2022) explored the potential of waste paper concrete by incorporating waste paper into concrete mixtures, substituting fine aggregate, coarse aggregate, and cement in varying proportions (0%, 5%, 10%, 15%, and 20%). The study found that the fresh, structural, and durability properties of concrete improved with the addition of waste paper at 5% and 10%, while a decline was observed beyond 10%. At 10% incorporation, the concrete showed an increase in strength due to the presence of hydrated cement particles, outperforming standard concrete without paper. Cellulose-reinforced concrete exhibits improved tensile strength and reduced brittleness, which are critical factors in prolonging the lifespan of concrete structures (Wang et al., 2021). The incorporation of cellulose fibers helps to distribute stresses more evenly within the concrete, reducing the likelihood of cracking and other forms of degradation. This not only enhances the structural integrity of buildings but also reduces the need for frequent repairs and maintenance, leading to lower lifecycle costs. However, the majority of researchers have reported that the mechanical performance of concrete increased with the addition of fibers only up to a 1.0% concentration, while further additions of fibers decreased the mechanical performance of concrete due to reduced workability (Ahmad and Zhou, 2022). Building on the innovative uses of cellulose waste in concrete, another example of its application comes from a project at a hydropower station in China, where cellulose fiber-reinforced concrete was employed for its durability and enhanced mechanical properties. The study utilized four different fiber contents (0.6, 0.9, 1.2, and 1.5 kg/m3) to determine the optimal mix for concrete slabs exposed to extreme conditions. Particularly, the concrete with a fiber content of 0.9 kg/m3 demonstrated superior compressive, splitting tensile, and flexural strengths compared to plain concrete. This optimized cellulose fiber content not only improved the concrete’s structural integrity but also its energy absorption capacity and toughness, making it highly suitable for the dam’s face slab in challenging environments. The implementation of his modified concrete in this project showcased significant benefits, as the dam face slab maintained a stable working condition through varying temperatures and even during seismic activities. These results underline the potential of cellulose fibers to enhance the resilience and longevity of concrete structures, particularly in hydroelectric projects where durability and performance under stress are paramount (Ma et al., 2020). Additionally, cellulose-reinforced concrete often requires less energy to produce than traditional concrete, further contributing to its sustainability (Rbihi et al., 2024).

Over the past decade, there has been a focused effort to explore the incorporation of agricultural waste products as alternative aggregates in both traditional concrete and bio-aggregate concrete. A wide range of these materials, including hemp, coconut shells, oil palm shells, corncob, straw, bamboo, and cork, have been explored for this purpose (Dias et al., 2024). Kilani et al. (2021), analyzed specific mechanical properties of concrete integrated with hemp fibers, noting improvements in tensile strength and reductions in density, which offered lightweight construction benefits. They found that adding 5% hemp fiber to the concrete mixture increased the tensile strength by 10% while reducing the overall weight of the concrete by 15%. Rice husks are another agricultural by-product being utilized in concrete. Each kilogram of milled white rice generates roughly 0.28 kg of rice husks, which are typically used in energy generation or composting. However, studies have shown that rice husks can be incorporated into concrete for their insulating properties. Chabannes et al. (2014) compared rice husk concrete with hemp concrete and found that while rice husk concrete showed lower mechanical performance, it offered superior thermal insulation, with thermal conductivity values ranging between 0.10 and 0.14 W/mK, making it a viable eco-friendly material for filling walls. Additionally, Marques et al. (2020) also demonstrated the suitability of rice husk concrete for use in acoustic barriers and thermal insulation in multilayer systems, highlighting its versatility and environmental benefits. Hemp shiv, another agricultural by-product, is widely recognized for its ecological benefits in construction, especially in the form of hempcrete. Hemp shiv, the woody core of the hemp stalk, is mixed with a binder such as lime to form hempcrete, which is valued for its excellent insulation properties and carbon sequestration capabilities. Hempcrete has been used in both prefabricated masonry blocks and as an in-situ cast material, offering advantages such as lower thermal conductivity and improved sustainability compared to traditional concrete. The use of lime-based binders further enhances hempcrete's environmental impact by reducing its carbon footprint (Babenko et al., 2022).

3. The Role of Mining Tailings in Advancing Sustainable Construction Practices

Mining tailings, the byproducts of mineral processing operations, are increasingly being recognized not merely as waste, but as valuable resources for sustainable construction (Maruthupandian et al., 2021). The existence of critical minerals and rare earth elements in discarded mine tailings also suggests that reprocessing these materials could yield both economic and technological benefits (Araujo et al., 2022). Historically, these materials have been relegated to storage facilities or waste dumps, posing environmental and safety risks. However, with advances in technology and a shift towards more sustainable practices, mining tailings are now being repurposed into a variety of construction materials. This approach not only mitigates the environmental hazards associated with tailings storage but also contributes to resource conservation by reducing the demand for virgin raw materials. This section explores the diverse applications of mining tailings in the construction industry, ranging from common uses such as aggregates in concrete to less common but innovative applications like ingredients in glass manufacturing.

Table 2 provides a summary of various construction applications for mining tailings, detailing the next sections their technical benefits and environmental impacts and highlighting the versatility and potential of these materials in the construction sector.

3.1. Mining Tailings as Aggregates in Concrete

Mining tailings are commonly used as aggregates in concrete production but their application varies significantly depending on the type of mine from which these tailings are sourced. This distinction is crucial as the chemical composition, particle size, and overall suitability for concrete production can differ dramatically, influencing both the environmental impact and the mechanical properties of the resulting concrete. For instance, tailings from iron ore mines have been successfully used in concrete as they typically possess high density and few deleterious materials, which can enhance the strength and weight of the final product (Huang et al., 2024). This makes iron ore tailings particularly suitable for heavy-duty applications such as foundations and load-bearing structures (Zhang et al., 2021). A case study from an iron ore processing facility in China demonstrated that replacing up to 30% of traditional aggregates with iron tailings could significantly increase the compressive strength and durability of dam concrete for hydraulic engineering applications. Furthermore, the concrete prepared with iron ore tailings exhibited superior durability compared to that prepared with normal aggregate, with the abrasion resistance being higher by 1.32–2.90 h m2/kg. Due also to the higher compressive strength, lower saturated-surface-dry water absorption, and angular shape of the iron ore tailing aggregates raw rock, the modified concrete showed overall durability performance. Significant economic and environmental benefits were also noted, including a cost saving of approximately 8.98 million USD in two practical hydraulic engineering applications. Additionally, the use of the modified aggregate resulted in a reduction of occupied land space, CO2 emissions, and water consumption by 151,900 m2, 8,157 tons, and 942,000 m3, respectively, with relative reductions in CO2 emissions and water consumption of 15.7% and 27.4% compared to normal aggregate (Lv et al., 2022). Conversely, tailings from copper and zinc mines often contain higher levels of sulfides, which can lead to durability issues such as acid generation and expansion when exposed to moisture and air (Vallejos et al., 2023). This makes them less suitable for use in environments exposed to water or in marine construction. However, these tailings have been effectively utilized in controlled low-strength materials for backfill and non-structural applications, where such limitations are less critical (Lam et al., 2020). Research from a copper mine in Chile explored the use of these tailings for paving paths and lightweight concrete blocks, where they performed well within the acceptable limits for non-structural use (Junior and Franks, 2022). In the study conducted by Adiguzel et al. (2022), the use of process tailings in the concrete industry was closely examined with several key outcomes identified. It was reported that the compressive and flexural strength of concrete decreases as the proportion of tailings increases, with optimal substitution levels found to be between 10% and 40% for fine aggregates and 5% to 20% for cement. Tailings were shown to enhance the mechanical and environmental properties of concrete when used in place of fine aggregates. Additionally, due to their filler effect, tailings positively affect the permeability and freeze-thaw resistance of concrete. However, if tailings exceed 10% of the mix, water permeability issues arise. High SiO2 content tailings (≥75%) proved beneficial as cement substitutes, particularly when the combined content of SiO2, Al2O3, and Fe2O3 in the tailings exceeded 75%. The particle size of tailings also plays a crucial role; those greater than 1 mm can enhance the compressive strength of the concrete. Despite these advantages, concrete containing tailings exhibited reduced carbonation resistance compared to normal concrete and could present environmental risks such as potential heavy metal mobilization and acid mine drainage. Nevertheless, according these authors, employing tailings in concrete production can lead to significant reductions in CO2 emissions from cement production and lower concrete production costs. The study emphasized the lack of extensive research on the environmental impacts of concrete with tailings, suggesting the need for more thorough investigations to widen the application of tailings in concrete production while considering both mechanical and environmental factors.

3.2. Mining Tailings in Cement Production

Mining tailings, typically composed of silica (SiO2), alumina (Al2O3), iron oxide (Fe2O3), and lime (CaO), offer a valuable resource for the cement industry (Gou et al., 2019). These chemical components are crucial for the formation of cement clinker, which is the core ingredient in cement production. By substituting or supplementing traditional raw materials with tailings, cement manufacturers can utilize a waste product beneficially while maintaining the essential chemical reactions required for high-quality cement. One of the primary advantages of using mining tailings in cement production is the potential to lower the sintering temperature needed for clinker formation (Jian et al., 2020). Typically, the process of sintering cement clinker requires temperatures up to 1450°C. However, when tailings rich in iron oxide and alumina are introduced, they can act as fluxing agents, reducing the temperature required to between 1300°C and 1350°C (Faria et al., 2023). This reduction is particularly effective when tailings are used in conjunction with medium calcium limestone, which is a common raw material in cement production (Wang et al., 2022). By decreasing the sintering temperature, the cement production process becomes significantly more energy-efficient, which not only reduces operational costs but also lessens carbon emissions -both critical factors in the industry's push towards sustainability. Additionally, the incorporation of tailings has been shown to enhance the mechanical properties of cement. Specifically, tailings can improve the burnability of the raw mix (Jian et al., 2020), which refers to the ease with which the raw materials combine to form clinker minerals under high temperatures. Improved burnability leads to a more consistent and complete reaction, enhancing the overall quality of the clinker. Furthermore, tailings can promote the formation of tricalcium silicate (C3S), the mineral primarily responsible for the strength developed in the early stages of cement setting (Da et al., 2022). The specific mineral compositions in tailings can vary depending on the source and type of mining activity, providing unique benefits in cement production. The presence of certain trace elements in tailings, such as manganese (Barbosa et al., 2024), or vanadium or titanium (Tian et al., 2024), can act as mineralizers, facilitating the formation of C3S and improving the speed of clinker formation. Tailings from iron ore mining, which are high in Fe2O3, can contribute to early strength development in cement (Tai et al., 2024). In contrast, tailings from aluminum ore processing might offer advantages in terms of durability and resistance to chemical attack (Eid and Saleh, 2021).

3.3. Mining Tailings in Ceramic and Brick Manufacturing

Mining tailings, utilized in ceramic and brick manufacturing, serve as substitutes or supplements for conventional raw materials such as clay and sand, which are typically extracted through environmentally costly mining processes (Pell et al., 2021). These tailings are primarily composed of silica, alumina, and iron oxide. These components are particularly valued in the ceramics and brick industries for their ability to enhance the physical and aesthetic properties of the final products. Silica, for example, plays a critical role in the formation of the glass phase during the firing process in ceramics production (DeCeanneet al., 2022). This phase is essential for creating the desired hardness and durability in ceramic products. Alumina, also abundant in tailings, contributes to the structural integrity of ceramics, enhancing their resistance to wear and tear and their ability to withstand high temperatures without deforming (Smirnov et al., 2023). Iron oxide, another significant component of many mining tailings, imparts a natural pigment to bricks, producing a range of earthy tones from reds to browns, which are highly sought after in building aesthetics (Khanam et al., 2023). Additionally, iron oxide influences the thermal properties of bricks, improving their insulative qualities and overall durability, which is crucial for structural applications where strength and longevity are required (Ozturk, 2023).

In the ceramics industry, the unique chemical makeup of mining tailings facilitates diverse applications, enhancing both the performance and aesthetic qualities of ceramic products. Solid tailings, especially those that are inert and non-sulfidic, are becoming increasingly popular as primary materials in ceramics. The similarity in chemical properties allows tailings to seamlessly replace clay in various ceramic manufacturing processes. Furthermore, the granular size of these tailings plays a crucial role in the ceramic production, affecting key characteristics such as plasticity, density, sintering rates, and porosity (Yilmaz et al., 2023). The use of finely sized tailings can significantly influence the manufacturing of porcelain, improving the end-product's quality and durability (Suvorova et al., 2020). This substitution is not only a matter of maintaining quality but also enhancing it, as the physiochemical interactions during the sintering process can lead to improved hardness and structural integrity of the ceramic items. Hua et al. (2023) utilized iron tailings as the primary raw material to develop a type of lightweight and high-strength ceramsite. By combining these iron tailings with dolomite and a small amount of clay, and processing them at 1150 °C in a nitrogen atmosphere, a new material was synthesized that exhibited enhanced mechanical strength, thermal stability, and significant adsorption capacity, making it ideal for diverse engineering applications. Ceramic floors and tiles are exemplary materials where industrial wastes like tailings can be utilized effectively. These products benefit from the enhanced properties provided by tailings, meeting the high standards required for modern construction and architectural designs. Paiva et al. (2021) investigated using sulfidic mine tailings in ceramic roof tiles, finding that incorporating 20% of theses tailings not only improved the tiles' properties but also reduced firing temperatures, thus saving energy and costs. The study also proposed a method to manage sulfate emissions, enhancing sustainability in construction material production. Additionally, the high-temperature and pH-resistant nature of ceramics made with tailings is crucial for applications in challenging industrial environments. The inherent chemical bonds in ceramics, predominantly covalent or ionic, are less reactive under extreme conditions, preserving the integrity and functionality of the ceramic products in oxidative and corrosive settings (Kinnunen et al., 2018).

Brick has long been an essential material in the construction and building industry, with its usage expanding continuously alongside the growing global population and increased structuring. This surge in demand is rapidly depleting the natural raw materials traditionally required for brick production. In response, researchers are actively seeking alternative materials for brick manufacturing. Kang et al. (2023) and Li et al., (2018) showed that iron ore tailings, due to their high density and mechanical strength, are effective for making bricks. Weishi et al. (2018) explored using fine-grained, low-silica iron ore tailings along with a non-cement curing system to create environmentally friendly bricks, incorporating a triethanolamine hardening accelerator and a stearic acid emulsion for waterproofing. Chen et al. (2020) developed high-strength autoclaved bricks from hematite tailings and investigated a hematite tailings-lime-sand mixture to guide their production. Nikvar-Hassani et al. (2022) found that copper tailings with low silica content are suitable for producing autoclaved sand-lime bricks that comply with building standards. Huang et al. (2024) demonstrated the potential of feldspar, quartz, and kaolin tailings in the ceramics industry, particularly in the manufacture of building clay-bricks fired at 1200 °C. To meet the mechanical resistance requirements of bricks, a binding agent is crucial due to its ability to durably adhere the primary materials together. Traditionally, clay and shale serve as natural binding agents in brick manufacturing, necessitating high-temperature firing between 800°C and 1000°C to produce bricks. However, mine tailings, rich in aluminum and silicon oxide, can substitute for clay in the production of bricks through geopolymerization (Das et al., 2024).

3.4. Tailings-Based Geopolymer

Geopolymers are synthesized from a complex three-dimensional network primarily composed of Si-O-Si and Al-O-Si bonds. These networks typically form through the reaction of aluminosilicate minerals (like fly ash or slag) with a concentrated alkali hydroxide or silicate salt solution. The geopolymerization process begins with the formation of Si(OH)4 or Al(OH)4 oligomers in the presence of an alkali solution enriched with Al and Si. This process progresses until the condensation of metal-oxygen bonds occurs, ultimately forming the geopolymer structure. During alkali activation, it is also possible to form hydrated C-S-H or C-A-S-H cementing gels (Zhang et al., 2023). The geopolymerization process is influenced by numerous factors, including the type and concentration of the alkali activator, the curing conditions, and the mineralogical composition of the aluminosilicates used. Other variables that can impact the process include the SiO2/Al2O3 ratio, the concentration of the alkali solution, the curing time and temperature, the liquid-to-solid ratio, and the pH (Zhang et al., 2024). These variables allow for the utilization of geopolymers in various applications such as in cement and concrete, fire-resistant materials, and toxic waste containment (Kriven et al., 2024).

Given their silica/aluminosilicate-based mineral composition, mine tailings are considered potential candidates for the geopolymer industry (Palma et al., 2024). However, unlike pozzolanic materials like slag, which mainly consist of amorphous minerals (e.g., SiO2), mine tailings typically have a more crystalline mineral structure. This crystallinity is due to the fact that mine tailings are usually produced through wet chemical processes (like flotation), unlike other by-products formed at high temperatures (like slag). This makes mine tailings less chemically reactive in the geopolymerization process. For instance, silica (-SiO2), an inert mineral in mine tailings, reacts less with alkali solutions due to its ordered crystalline structure (Manaviparast et al., 2024). Therefore, pretreatment (such as thermal) or blending with other aluminosilicates might be necessary to enhance the reactivity of mine tailings in geopolymer applications. Nonetheless, the formation of a silica polymer (Si-O-Si derived from silica sol) around the tailings’ particles can help stabilize and build the tailings-based geopolymer structure (Yilmaz et al., 2023). Recent applications of tailings-based geopolymers have included iron tailings/fly ash-based geopolymers used as binder materials due to their high thermal conductivities, low porosity, and microcracks, as well as enhanced setting times and ultimate compressive strength (Das et al., 2024). Phosphate tailings-based geopolymers also serve as binder materials due to their characteristics (Wang et al., 2023). Slag/metakaolin/gold tailings-based geopolymers are used for lightweight aggregates thanks to their high strength characteristics (Asadizadeh et al., 2024). Copper tailings-based geopolymers find application in road base construction materials (Nikvar-Hassani, 2022) and bricks (Krishna et al., 2023), with copper tailings/cement kiln dust-based geopolymers noted for their stability and enhanced ultimate compressive strength. Silica-rich vanadium tailings/fly ash-based geopolymers are employed in fire-resistant materials due to their stability over a wide range of temperatures (Yilmaz et al., 2023).

3.5. Mining Tailings: Other Uses

In addition to all the applications discussed in the previous sections, mining tailings are finding expanded uses in the construction industry. One novel application is in glass manufacturing, where tailings rich in silica provide a perfect raw material. Okereafor et al. (2020) evaluated raw, water-treated, nitric acid-treated, and sulfuric acid-treated gold mine tailings to determine their effectiveness in glass production. The findings revealed that sulfuric acid-treated tailings yielded satisfactory quality for green glass, whereas raw, water-treated, and nitric acid-treated tailings exhibited white residues that compromised glass quality. The research suggested further refining of sulfuric acid-treated tailings to decrease iron oxide content, potentially extending their use beyond green and amber glass production. Alfonso et al. (2020) investigated the use of tailings from fluorite mines, which are rich in calcium, to produce commercial glass by adding varying amounts of soda. The study revealed that glasses with a lower soda content displayed increased stability against crystallization but were more challenging to produce due to stricter temperature constraints during processing. These findings demonstrated that fluorite mine tailings could be transformed into commercial glass that effectively encapsulates potentially toxic elements, thereby mitigating environmental risks associated with tailings disposal. The glass containing 20% Na2CO3 proved particularly effective in this capacity, though economic considerations must be taken into account to balance cost against environmental benefits. This method offers a promising avenue for repurposing hazardous mine waste into useful and environmentally friendly products. Lu et al. (2024) explored the creation of lightweight glass ceramics using phosphorus tailings and coal gangue, focusing on developing eco-friendly building materials. The study analyzed the effects of different proportions of phosphorus tailings and heat-treatment temperatures on the ceramics' properties and environmental safety. Findings indicated that increased phosphorus tailings led to larger pore sizes and improved insulation properties, while higher heat-treatment temperatures enhanced the material's resistance to water and corrosion. Optimal conditions were identified as 80 wt% phosphorus tailings at a heat-treatment temperature of 1160°C, producing ceramics with excellent porosity, strength, and durability.

Tailings are also utilized as versatile fill material in various construction and landscaping endeavors. Their utility ranges from serving as sub-base materials for roads to filling voids or being used to reclaim unused land areas. Employing tailings in these capacities effectively manages large volumes of these materials, which helps in diminishing the need for extracting and processing new raw materials. This method not only provides a sustainable solution to waste management but also supports environmental conservation efforts. For instance, Sangiorgi et al. (2016) highlighted the use of mine waste as raw materials for infrastructure, potentially impacting local communities and broader European mining activities positively. This initiative explored the economic and social benefits of recycling mine tailings into new materials that could replace commonly used substances in infrastructure projects. The focus was on developing a design method for alkali-activated materials that utilize mine and quarry wastes, aiming to create less porous and more durable materials than traditional road paving options. Further research has categorized the use of mining wastes in road construction into several forms: direct use without treatment, stabilization with hydraulic binders like cement or lime, stabilization through geopolymerization, and use with asphalt (Segui et al., 2023). Untreated coarse coal wastes, for example, have been adapted for use as gravel in various applications, including pipeline ditch refills and parking lot surfaces. The fine tailings have found use as aggregates in cobbling and even as fillers in the cement industry due to their suitable particle sizes and compositions (Jahandari et al., 2023). Moreover, tailings that contain gypsum are increasingly being processed for use in the production of plaster and drywall (Prasad, 2024). These diverse applications of mining tailings not only extend the lifecycle of mined materials but also contribute to more sustainable and cost-effective resource management within the construction industry.

4. The Role of Metallurgy Slags in Sustainable Construction

Metallurgy slags, the by-products of the metal smelting process, are increasingly being viewed not just as waste but as valuable resources for sustainable construction practices (Randhawa, 2023). These slags are composed of a mixture of oxides, silicates, and other metal derivatives, which have significant potential in various construction applications. Historically considered a disposal challenge, these materials are now recognized for their potential in reducing the construction industry's reliance on virgin raw materials, thereby supporting environmental sustainability (Baalamurugan et al., 2024). In the iron and steel industry, the production of metallurgy slags is particularly notable, as the sector generates large quantities of this material during the steelmaking process. In 2023, global production of iron slag was estimated to range between 330 million and 390 million tons, while steel slag production was estimated to be between 190 million and 290 million tons (USGS, 2024). The rising production of these slags highlights the need for effective management and reuse, particularly in the construction sector, where they can serve as substitutes for traditional materials, reducing environmental impacts and enhancing the sustainability of construction practices.

Table 3 provides a summary of various construction applications for metallurgy slags, while the next sections detail their technical benefits and environmental impacts, underscoring the versatility and potential of these materials in the construction sector.

4.1. Metallurgy Slags in Concrete Production

Slags have versatile applications across different industries, with concrete production being one of the most common (Piemonti et al., 2021). Their reuse as replacements for binders, fine, or coarse aggregates depends on the slags' physical, chemical, and mechanical properties, as well as the specific treatments they undergo before being utilized. Among these, the reuse of iron and steel slags in concrete production stands out for its significant potential to enhance the properties of concrete mixtures while also offering environmental benefits. These slags, including blast furnace slag, basic oxygen furnace slag, electric arc furnace slag, and ladle furnace slag, have unique physical, chemical, and mechanical properties that make them suitable for various applications as substitutes for cement, fine, or coarse aggregates. Specifically, blast furnace slag is commonly used as a partial replacement for cement in concrete due to its hydraulic properties, which improve the strength and durability of the concrete mix. Studies have shown that these slags can replace between 20% and 70% of cement, leading to reduced CO2 emissions and cost savings (Shumuye et al., 2021). Optimal performance is observed with replacement levels between 20% and 30% (Ahmad et al., 2022), enhancing compressive and tensile strengths while maintaining good workability. However, challenges such as increased setting times and higher autogenous shrinkage need further investigation, particularly concerning long-term durability and resistance to chloride and sulfate attacks (Asaad et al., 2022). On the other hand, basic oxygen furnace slag exhibits good mechanical properties, but its use in concrete is limited due to its high volumetric expansion caused by free-CaO and MgO content. Treatments such as carbonation and scrubbing processes have been developed to reduce these components, making these slags a viable option for replacing natural aggregates or as a binder (Omur et al., 2023). However, due to the lower hydraulic activity compared to cement clinker, basic oxygen furnace slag is more suitable for unbound applications, such as road construction, and further research is needed to optimize its use in concrete (Zago et al., 2023). Similarly, electric arc furnace slag is widely used as a replacement for natural aggregates in concrete production, improving the mechanical properties of full-scale elements like beams and columns (Diotti et al., 2021). However, when used as a cement replacement, issues such as slower strength development, increased setting times, and greater autogenous shrinkage have been observed (Kurecki et al., 2024). While these slags show promise for enhancing the density and durability of concrete, further studies are needed to address its performance under freeze/thaw cycles, water permeability, and behavior in aggressive environments. Finally, ladle furnace slag has low hydraulic properties and is prone to volumetric instability, which complicates its reuse in concrete. Some studies have explored using these slags as a partial cement replacement in low-strength civil engineering applications, often requiring activation with alkali treatments. However, concerns regarding its workability, shrinkage, and long-term durability persist, necessitating more comprehensive research before real-world applications can be realized (Araos et al., 2024).

In addition to iron and steel slags, other slags from various metallurgical processes also have significant applications in concrete production. Copper slag, for example, is generated during the smelting process of copper and contains high levels of iron, silicon, and aluminum oxides, making it suitable as a substitute for aggregates in concrete. These slags enhance abrasion resistance and the density of concrete, and have been successfully used in applications such as pavements and building blocks. However, their use is limited by the potential leaching of heavy metals, which requires strict environmental controls (Ahmad et al., 2023). Copper slag specifically has demonstrated credibility for partial utilization in concrete, either as a binding material or as sand. Studies have shown that the optimal percentage of these slags in concrete can significantly impact its strength, with typical substitution rates ranging from 50 to 60% by weight of fine aggregate (Sahu et al., 2024). This variability in optimal use is often due to differences in the slag’s source. Despite its ability to enhance the mechanical properties of concrete, copper sag usage faces limitations in tensile strength. Ongoing research suggests incorporating various types of fibers to enhance the ductility of concrete mixtures containing these slags (Casagrande et al., 2023). Nickel slag is another valuable by-product that can be used in construction. Rich in silicate and magnesium, nickel slags have been employed as a partial replacement for fine aggregates in concrete, improving wear resistance and thermal stability (Yanning et al., 2024). Additionally, nickel slag has been shown to increase the concrete's resistance to aggressive environments, such as marine conditions, due to its dense microstructure and reduced permeability (Nguyen and Castel, 2023). Chen et al. (2023) demonstrated that the highest flexural and compressive strength for concrete using nickel slag sand was achieved at an optimal dosage of 30%. Phosphorous slag, a by-product of phosphoric acid production, also shows promise in concrete applications. Due to its high glass content and latent hydraulic properties, it can be used as a supplementary cementitious material, similar to ground granulated blast furnace slag. Phosphorous slag currently utilized in concrete industries with a low cement replacement rate of 20-30%, due to its low pozzolanic activity (He et al., 2024). But this material has been found to improve the durability of concrete, particularly its resistance to sulfate attack and alkali-silica reaction, making it a suitable material for infrastructures exposed to harsh chemical conditions (Jia et al., 2023). These alternative slags expand the range of sustainable materials available for concrete production, helping to reduce the environmental footprint of construction while enhancing the performance of concrete in various applications.

4.2. Slags in Road Construction

Slags have found extensive use in road construction, primarily as a base material for roads and as an aggregate for asphalt. Their rough texture and high density provide excellent mechanical properties, such as stability and durability, essential for heavy-duty applications (Wang et al., 2024). Steel slag, for example, offers numerous benefits as a material for road construction, thanks to its advantageous physical and chemical properties (Aquib et al., 2023). Steel slag exhibits superior performance compared to natural aggregates, with abrasion values ranging from 15% to 25%, significantly lower than those of typical natural aggregates, which can exceed 30% (Díaz-Piloneta et al., 2021). Its crushing strength is higher, often above 200 MPa, compared to around 150 MPa for natural aggregates, and its soundness index is less than 12%, indicating better resistance to weathering (Kim et al., 2018). Its rough, angular texture provides excellent interlocking, improving skid resistance by up to 50% compared to conventional aggregates (Passeto et al., 2023). Steel slag also enhances resistance to moisture damage, with tensile strength ratios often exceeding 90%, compared to 70-80% for natural aggregates, and it shows reduced rut depth in asphalt mixtures, often measuring less than 2.5 mm in repeated load tests (Wang et al., 2024). Studies have consistently shown that incorporating steel slag into road pavements significantly improves durability and fatigue resistance, with fatigue life increasing by up to 30% compared to mixes without slag (Liu et al., 2022). Additionally, its versatility allows it to serve as both a coarse and fine aggregate, optimizing the performance of asphalt and concrete mixtures.

Similarly, phosphorus slag has also been proven both theoretically and experimentally to be a feasible additive in asphalt concrete mixtures for road construction, enhancing the operational properties of road surfaces. Yang et al. (2023) have showed that the significant porosity of phosphorus slag improves asphalt concrete's structure, increasing strength, density, and waterproofness by up to 20%, while reducing bitumen consumption by 15%. These authors also found that the slag’s interaction with bitumen is similar to limestone, and it has comparable effects on bitumen aging. Additionally, the coarse texture of slag enhances the internal friction angle, stability, and resistance of asphalt concrete, particularly in high temperatures, making it an excellent alternative to conventional materials like limestone. Extending the exploration of alternative slag materials, Kong et al. (2024) successfully applied iron tailing slag in road subbase construction, demonstrating the material's potential when integrated with optimal additives. Their research found that a mixture containing 6:1 slag to fly ash ratio, 4% calcium oxide, 5% cement, and 0.02% water-resistant base stabilizer achieved an impressive 7-day unconfined compressive strength of 1.97 MPa and an elastic modulus of 286 MPa. Copper slag, another promising alternative material, has also been explored for its potential in road construction, especially as a substitute for fine aggregates in asphalt and structural fill applications. Soni et al. (2022) investigated the use of fine copper slag in road embankments, subgrades, and subbases, demonstrating its potential to enhance the mechanical properties of road layers. The study revealed that copper slag, due to its high specific gravity and angular particle shape, significantly improves the compaction characteristics and stability of road materials. The incorporation of 60% fine copper slag as a replacement for sand resulted in increased California Bearing Ratio (CBR, parameter that measures the shear strength and load-bearing capacity of a soil or granular material) values, reaching up to 15%, compared to traditional soil-sand mixtures with CBR values of 8-10%. This improvement not only enhances the load-bearing capacity of subgrade layers but also reduces swelling and moisture susceptibility, making copper slag a cost-effective and environmentally sustainable alternative to natural aggregates in road construction.

4.3. Innovative Uses in Bricks and Ceramics

Beyond conventional uses, metallurgy slags are being explored as primary materials in the manufacture of bricks and ceramics. The high silica and alumina content in these slags make them suitable for the production of heavy clay products. Incorporating slag into brick manufacturing can reduce the firing temperature needed, thus saving energy and reducing emissions. Furthermore, bricks made with slag exhibit enhanced durability and better thermal insulation properties compared to traditional clay bricks (Zakaria et al., 2024). Several types of slag are currently utilized in brick. Liu et al. (2024) explored the performance and reaction mechanisms of alkali-activated clay bricks incorporating steel slag and fly ash. Steel slag enhanced early compressive strength, while clay brick provided silicon and aluminum, aiding the reaction process. Fly ash dissolved quickly at higher temperatures, supplying additional silicon and aluminum, and together with clay brick, promoted calcium dissolution from steel slag. The optimal mix, with 30% steel slag, formed calcium-alumino-silicate-hydrate (C-A-S-H) and sodium-alumino-silicate-hydrate (N-A-S-H) gels that strengthened the system by wrapping partially hydrated clay brick. In another study, Ren et al. (2022) conducted a comprehensive evaluation of aluminum ash and calcium carbide slag for brick manufacturing under ultra-high pressure conditions. The optimal conditions were a 1:9 ratio of aluminum ash to calcium carbide slag, 300 MPa pressure, 5-day curing time, and natural curing. The resulting bricks showed high compressive (75 MPa) and flexural strength (3.6 MPa), excellent waterproof properties, and met environmental standards for leaching toxicity, demonstrating a viable approach to recycling these industrial wastes into high-performance building materials. Hou et al. (2021) examined the microstructure and mechanical properties of CO2-cured steel slag bricks at a pilot scale, while Wang et al. (2021) investigated how moisture content affects bio-carbonated steel slag bricks. Both investigations demonstrated innovative uses of CO₂ and microbial carbonation in steel slag brick production. Hou et al. found that bricks with 25% steel slag achieved the highest CO₂ uptake (7.5%) and a compressive strength of 27.7 MPa, meeting standards for load-bearing bricks, with excellent volume stability and freeze-thaw resistance. Wang et al. showed that moisture content significantly influences the carbonation process, with optimal water levels enhancing CO₂ diffusion and bacterial activity, improving carbonation efficiency, while too much moisture reduced these effects, impacting the final carbonation depth. Chen et al. (2022) studied the impact of electric arc furnace slag on enhancing the quality and environmental safety of fired bricks that include municipal solid waste incineration fly ash. The slag increased density and reduced porosity and water absorption by over 50%, enhanced compressive strength by 50%, and lowered thermal conductivity. It also promoted chemical reactions and significantly reduced heavy metal leaching, making the bricks safer and more durable, addressing the drawbacks of using fly ash in brick manufacturing. Maierdan et al. (2020) focused on recycling waste river sludge into unfired green bricks stabilized with phosphogypsum, slag, and cement. The study used hemihydrate phosphogypsum to dehydrate the sludge and combined it with cement, sodium metasilicate, and slag. The optimal mix achieved a compressive strength of 31 MPa, meeting quality standards, with 96% waste utilization. The microstructural analysis confirmed the formation of calcium silicate hydrate and ettringite, enhancing brick strength. Fuchs et al. (2023) developed CO₂-cured, carbon-reducing slag-based masonry bricks at a pre-industrial scale, replacing conventional hydraulic binders with steel industry slags. The CO₂-curing process at 15 bar, 50 °C, and 6 hours resulted in compressive strengths of 24 to 49 MPa, surpassing those of traditional sand-lime bricks. The lifecycle assessment revealed a CO₂-saving potential of 337 kgCO₂ per cubic meter of brick compared to conventional methods, highlighting the significant environmental benefits and industrial feasibility of CO₂-curing slag-based bricks. Guo et al. (2024) analyzed the corrosion behavior of CaO–Al₂O3–SiO₂–MgO-Cr₂O3 slag on MgO refractory bricks used in chromite smelting. Their study investigated the reaction mechanisms between the slag and the refractory, revealing that the main slag phases were pyroxene, chromium spinel, and magnesium olivine. SEM-EDS analysis showed that at the contact surface, calcium magnesium olivine and magnesium olivine were predominant, with calcium magnesium olivine increasing as slag basicity rose. Thermodynamic calculations indicated that higher slag basicity lowered melting temperature and viscosity, allowing molten slag to infiltrate the brick pores, accelerating corrosion. Chinyama et al. (2023) assessed the mechanical performance and contaminant leaching behavior of cement-based and fired bricks containing ferrochrome slag. The study compared these slag-containing bricks with conventional ones, revealing that bricks with 20–30% ferrochrome slag had higher compressive strength and lower water absorption. Contaminant leaching of trace metals and chloride was similar or lower than controls, except for higher manganese and chromium leaching in slag-containing debris due to their elevated concentrations in the slag. Cement-based bricks provided the highest strength, while fired bricks showed the least contaminant leaching. However, not all studies have yielded positive results. Gao et al. (2023) examined the effect of slag composition on the corrosion resistance of high-chromia refractory bricks used in industrial entrained-flow gasifiers. Their study found that slag types influenced corrosion severity, with high-Ca/Na slag causing the most damage, followed by high-Fe slag, and high-Si/Al slag being the least corrosive. High-Ca/Na slag reacted with the refractory, forming low melting point phases that disrupted the brick’s matrix. High-Fe slag led to iron phase precipitation and spinel layer formation at the interface. The interaction of ZrO₂ in the refractory with CaO from the slag formed calcium zirconate, which weakened the refractory's structure and increased corrosion. After the analysis, it is observed that although most studies highlight the benefits of using slag in bricks and ceramics manufacturing, such as improved mechanical properties and environmental advantages, it is essential to carefully assess the slag composition to mitigate potential negative effects, such as increased corrosion or contaminant leaching.

4.4. Slags in Cement Production

The use of slag in cement production is well-established, with its ability to substitute a portion of the clinker in Portland cement, known as slag cement. This substitution not only conserves limestone and reduces the energy required for clinker production but also significantly diminishes CO2 emissions. The resulting slag cement generally shows improved performance characteristics such as lower heat of hydration, better workability, and increased resistance to aggressive environments, making it highly desirable for marine and hydraulic constructions (Amran et al., 2021). Several examples illustrate how different types of slag, with varying compositions and processing techniques, contribute to the performance and sustainability of eco-cements. Kurniati et al. (2023) investigated the use of steel slag, ferronickel slag, and copper mining waste, in cement production, highlighting their potential to partially replace traditional cement materials and enhance sustainability. Steel slag, with its high calcium oxide content and chemical properties similar to Portland cement, replaced up to 30% of traditional cement, significantly reducing CO₂ emissions and enhancing mechanical properties such as compressive strength and durability. Ferronickel slag, rich in silicon dioxide (up to 40%), exhibited pozzolanic activity, contributing to the formation of secondary calcium silicate hydrates and improving long-term strength in blended cements. Copper slag, characterized by high iron oxide (around 40%) and low calcium content, also showed promise as a pozzolanic material, particularly when rapidly cooled to maintain an amorphous silica state, allowing effective participation in the hydration process. When used at replacement levels of about 15-20%, copper slag contributed similar compressive strength gains as traditional pozzolans, demonstrating its value in cement formulations. Ryu et al. (2024) successfully demonstrated that steelmaking slag, enriched with noncarbonated CaO from the decarbonization of limestone during steel production, can effectively replace a portion of natural limestone in cement clinker production. Their findings revealed that this substitution not only contributes to a significant reduction in CO2 emissions but also enhances the overall material properties of the cement. The slag’s rich calcium content proved beneficial in maintaining the necessary lime saturation factor for optimal clinker formation. Through their detailed analysis, these authors also confirmed that the adjusted slag, when processed with targeted grinding and chemical stabilization, integrates well into cement mixtures, providing improved performance characteristics such as increased durability and strength of the final cement product. Demarco et al. (2024) investigated eco-sustainable cements made from iron-making slags and gypsum waste, with formulations containing 80-90% blast furnace slag, 10-20% gypsum, and 10-15% basic oxygen furnace slag. The best-performing eco-cement achieved compressive strengths greater than 50 MPa at 28 days and over 80 MPa at 180 days. This high performance was attributed to its composition, which included basic oxygen furnace slag with high basicity (3.1), a significant content of brownmillerite (19%), and dicalcium silicate (21%), along with blast furnace slag rich in aluminum (15%). These factors contributed to enhanced hydration, the formation of ettringite, and consistent strength growth throughout the curing process. Xie et al. (2024) explored a large-scale industrial method for using modified magnesium slag in cement production to address the disposal challenges of magnesium slag waste. The study found that cement produced with modified magnesium slag met the standards for general Portland cement. The hydration process revealed a unique interaction between magnesium slag and clinker, enhancing early hydration and contributing to the cement’s performance. Additionally, using modified magnesium slag reduced carbon emissions by 7.95% and production costs by over 10% per ton of cement, demonstrating significant environmental and economic benefits.

5. Overcoming Barriers to Integration

As deduced from the previous sections, the integration of secondary resources like cellulose waste, mining tailings, and metallurgy slags into the construction sector offers substantial environmental and economic benefits. However, significant barriers impede their widespread use, including economic challenges, technological limitations, restrictive regulations, and the need for innovative business models. Among them, economic challenges are a major obstacle to integrating secondary resources in construction (Amarasinghe et al., 2024). The high costs associated with processing these materials, such as mining tailings and metallurgy slags, often involve specialized treatments, like grinding, chemical stabilization, or thermal activation, which require significant investments in technology and infrastructure. According to recent studies, despite the low cost or availability of these secondary materials, the processing expenses can be prohibitive, especially for small and medium-sized companies that lack access to the necessary capital and technological resources (Sajid et al., 2024). The inconsistent supply and variable quality of these materials further complicate cost-benefit analyses, making their integration less economically attractive (Shooshtarian et al., 2024a). Specific examples highlight the economic barriers associated with metallurgy slags, where steel slags need stabilization to reduce free lime content and prevent volumetric expansion, while copper slags must be rapidly cooled to retain their pozzolanic properties. The costs associated with these treatments can significantly impact the economic viability of using such materials. Similarly, cellulose derived from industrial processes like paper manufacturing requires extensive cleaning and refinement, which can outweigh the benefits if not optimized. Economic incentives, such as carbon pricing mechanisms like carbon taxes or emissions trading systems, can further encourage the use of secondary resources by making traditional, carbon-intensive construction materials comparatively more expensive. Government subsidies, or tax breaks targeted at offsetting these initial processing costs could be instrumental in making the use of secondary resources more feasible economically (Jayalath, 2024).

Technological limitations also present substantial barriers. The varied composition of secondary materials with potential applications in the construction sector requires different processing techniques to ensure they meet the standards necessary for construction applications. Tailings, for instance, may contain hazardous elements like heavy metals, which necessitate complex management strategies, including innovative treatments such as thermal activation or blending with other materials to mitigate environmental risks. Similarly, cellulose waste, sourced from paper mills or agricultural residues, requires tailored treatments like refining or enzymatic processing to optimize fiber quality for use in construction, but these processes can be costly and resource-intensive. Additionally, metallurgy slags used in cement production face challenges due to variable compositions that can affect hydration and stability, requiring further refinement of activation methods. However, these advanced techniques are not yet widely adopted due to their complexity, cost, and the need for further research and development (Giorgi et al., 2022). The lack of sufficient data and standardized processes further inhibits the broader use of these materials (Munaro y Tavares, 2023). Innovative business models are also key to overcoming economic and logistical barriers. Industrial symbiosis, where companies collaborate to utilize each other’s by-products, can optimize resource use and supply chains for secondary materials. For instance, direct partnerships between steel manufacturers and cement producers can streamline the incorporation of steel slags into cement production, reducing transportation and processing costs while ensuring a consistent supply of high-quality materials (Chen et al., 20223).

The regulatory environment is another significant barrier, often rooted in outdated classifications and standards that fail to accommodate the innovative use of secondary materials (Babalola and Harinarain, 2024). For example, the classification of industrial by-products like slags and tailings as waste imposes strict handling and disposal regulations, increasing compliance costs and discouraging their reuse in construction (Sorvari and Wahlström, 2024). There is a pressing need for the modernization of regulatory frameworks, which should recognize secondary materials as valuable resources rather than mere waste. By establishing comprehensive guidelines and standards, such as defining precise minimum quality requirements and acceptable levels of contamination, governments can significantly facilitate their broader adoption. This role is crucial in refining these frameworks to mirror the advancements in technology and adapt to the evolving market needs. Furthermore, policy adjustments that reclassify certain industrial by-products from waste to resources could lead to substantial reductions in compliance costs, thereby incentivizing companies to explore their use. In addition, the introduction of quality standards specifically designed for secondary materials could bridge the gap caused by market hesitancy, ensuring that these materials comply with the necessary performance and safety standards required for construction applications.