Submitted:

07 April 2025

Posted:

07 April 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

Introduction

Cases Presentation

Case 1

Case 2

Case 3

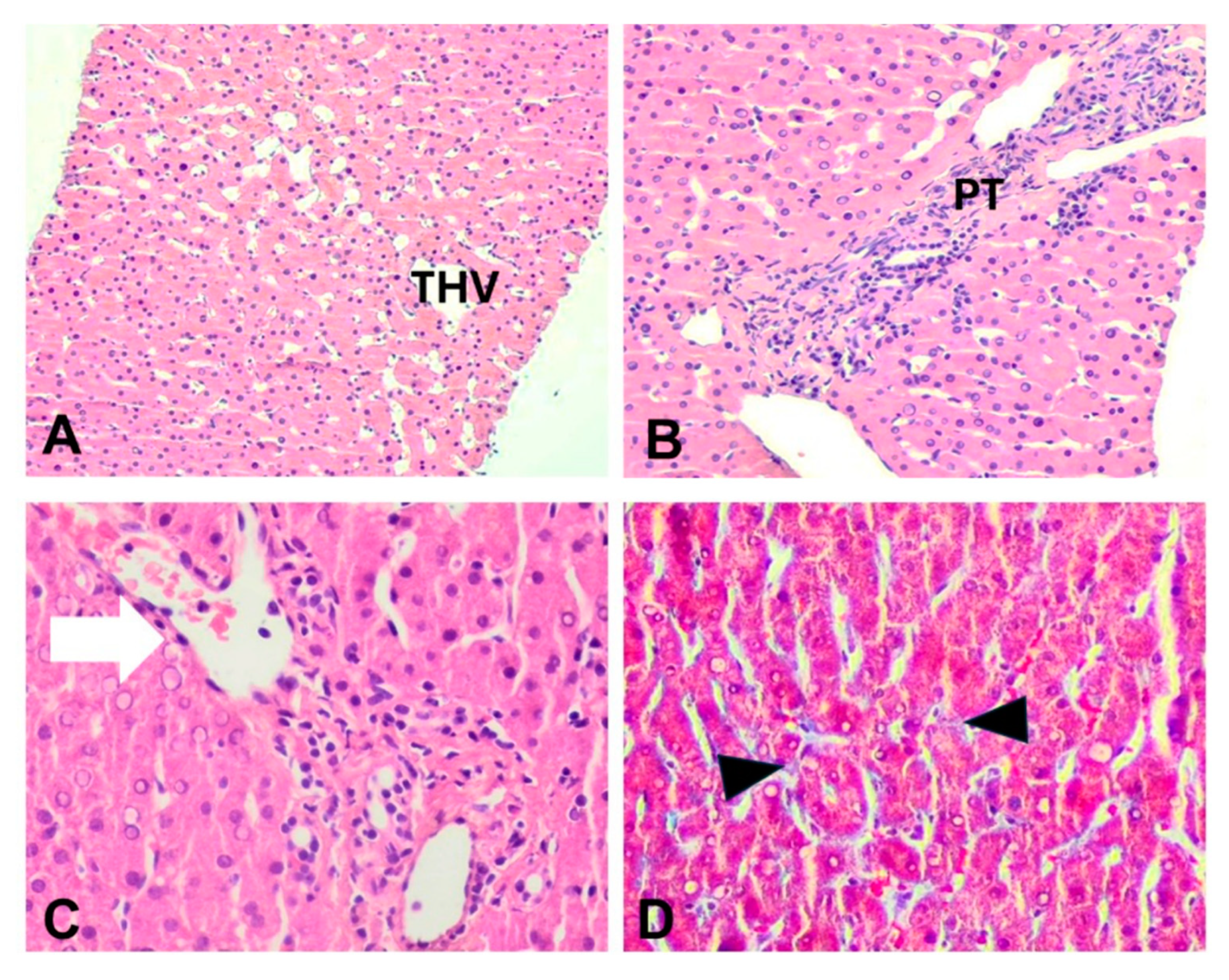

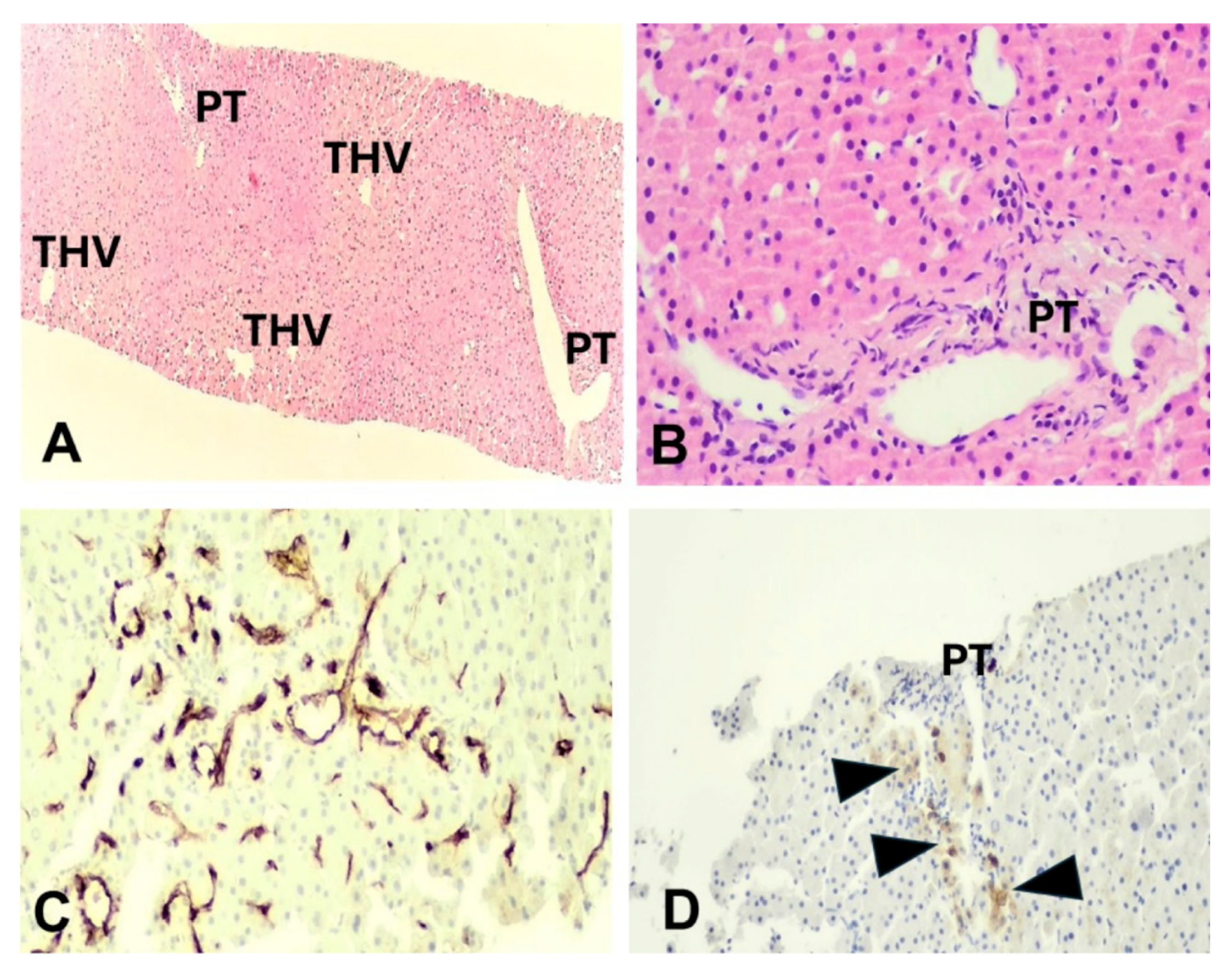

Diagnostic Assessment

Discussion

Conclusions

Conflicts of Interest statement

Funding statement

Financial support statement

Ethics approval

Acknowledgments

Abbreviations

References

- Gravholt, C.H.; Andersen, N.H.; Conway, G.S.; et al. Clinical practice guidelines for the care of girls and women with Turner syndrome: proceedings from the 2016 Cincinnati International Turner Syndrome Meeting. Eur J Endocrinol. 2017, 177, G1–G70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gravholt, C.H.; Viuff, M.; Just, J.; Sandahl, K.; Brun, S.; van der Velden, J.; Andersen, N.H.; Skakkebaek, A. The Changing Face of Turner Syndrome. Endocr. Rev. 2022, 44, 33–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gravholt, C.H.; Viuff, M.H.; Brun, S.; Stochholm, K.; Andersen, N.H. Turner syndrome: mechanisms and management. Nat. Rev. Endocrinol. 2019, 15, 601–614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pimblett, A.C.; La Rosa, C.; King, T.F.J.; Davies, M.C.; Conway, G.S. The Turner syndrome life course project: Karyotype-phenotype analyses across the lifespan. Clin. Endocrinol. 2017, 87, 532–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Calanchini, M.; Moolla, A.; Tomlinson, J.W.; Cobbold, J.F.; Grossman, A.; Fabbri, A.; Turner, H.E. Liver biochemical abnormalities in Turner syndrome: A comprehensive characterization of an adult population. Clin. Endocrinol. 2018, 89, 667–676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Mansoury, M.; Berntorp, K.; Bryman, I.; Hanson, C.; Innala, E.; Karlsson, A.; Landin-Wilhelmsen, K. Elevated liver enzymes in Turner syndrome during a 5-year follow-up study. Clin. Endocrinol. 2007, 68, 485–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bourcigaux, N.; Dubost, E.; Buzzi, J.-C.; Donadille, B.; Corpechot, C.; Poujol-Robert, A.; Christin-Maitre, S. Focus on Liver Function Abnormalities in Patients With Turner Syndrome: Risk Factors and Evaluation of Fibrosis Risk. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2023, 108, 2255–2261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viuff, M.H.; Stochholm, K.; Grønbæk, H.; Berglund, A.; Juul, S.; Gravholt, C.H. Increased occurrence of liver and gastrointestinal diseases and anaemia in women with Turner syndrome – a nationwide cohort study. Aliment. Pharmacol. Ther. 2021, 53, 821–829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, I.; Noel, G.; Barker, J.M.; Chatfield, K.C.; Furniss, A.; Khanna, A.D.; Nokoff, N.J.; Patel, S.; Pyle, L.; Nahata, L.; et al. Hepatic abnormalities in youth with Turner syndrome. Liver Int. 2022, 42, 2237–2246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koulouri, O.; Ostberg, J.; Conway, G.S. Liver dysfunction in Turner's syndrome: prevalence, natural history and effect of exogenous oestrogen. Clin. Endocrinol. 2008, 69, 306–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gravholt, C.H.; Juul, S.; Naeraa, R.W.; Hansen, J. Morbidity in Turner Syndrome. J. Clin. Epidemiology 1998, 51, 147–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fuchs, M.M.; Jost, C.A.; Babovic-Vuksanovic, D.; Connolly, H.M.; Egbe, A. Long-Term Outcomes in Patients With Turner Syndrome: A 68-Year Follow-Up. J. Am. Hear. Assoc. 2019, 8, e011501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fedor, I.; Zold, E.; Barta, Z. Liver Abnormalities in Turner Syndrome: The Importance of Estrogen Replacement. J. Endocr. Soc. 2022, 6, bvac124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Gottardi, A.; Sempoux, C.; Berzigotti, A. Porto-sinusoidal vascular disorder. J. Hepatol. 2022, 77, 1124–1135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Gottardi, A.; Rautou, P.-E.; Schouten, J.; Rubbia-Brandt, L.; Leebeek, F.; Trebicka, J.; Murad, S.D.; Vilgrain, V.; Hernandez-Gea, V.; Nery, F.; et al. Porto-sinusoidal vascular disease: proposal and description of a novel entity. Lancet Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2019, 4, 399–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roulot, D.; Degott, C.; Chazouillères, O.; Oberti, F.; Calès, P.; Carbonell, N.; Benferhat, S.; Bresson-Hadni, S.; Valla, D. Vascular involvement of the liver in Turner's syndrome. Hepatology 2004, 39, 239–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gioia, S.; Baiocchini, A.; D'Amati, G.; Tavano, D.; Ridola, L.; Nardelli, S.; de Felice, I.; Lapenna, L.; Merli, M.; Pellicelli, A.; et al. Porto-sinusoidal vascular disorder (PSVD): Application of new diagnostic criteria in a multicenter cohort of patients. Dig. Liver Dis. 2023, 56, 291–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guido, M.; Alves, V.A.F.; Balabaud, C.; Bathal, P.S.; Bioulac-Sage, P.; Colombari, R.; Crawford, J.M.; Dhillon, A.P.; Ferrell, L.D.; Gill, R.M.; et al. Histology of portal vascular changes associated with idiopathic non-cirrhotic portal hypertension: nomenclature and definition. Histopathology 2018, 74, 219–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciriaci, N.; Bertin, L.; Rautou, P.-E. Genetic predisposition to porto-sinusoidal vascular disorder. Hepatology 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jørgensen, K.T.; Rostgaard, K.; Bache, I.; Biggar, R.J.; Nielsen, N.M.; Tommerup, N.; Frisch, M. Autoimmune diseases in women with Turner's Syndrome. Arthritis Rheum. 2010, 62, 658–666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lleo, A.; Moroni, L.; Caliari, L.; Invernizzi, P. Autoimmunity and Turner’s syndrome. Autoimmun. Rev. 2012, 11, A538–A543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gatti, S.; Gelzoni, G.; Catassi, G.N.; Catassi, C. The Clinical Spectrum of Inflammatory Bowel Disease Associated With Specific Genetic Syndromes: Two Novel Pediatric Cases and a Systematic Review. Front. Pediatr. 2021, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yamaguchi, N.; Tokushige, K.; Haruta, I.; Yamauchi, K.; Hayashi, N. Analysis of adhesion molecules in patients with idiopathic portal hypertension. J. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 1999, 14, 364–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kotani, K.; Kawabe, J.; Morikawa, H.; Akahoshi, T.; Hashizume, M.; Shiomi, S. Comprehensive Screening of Gene Function and Networks by DNA Microarray Analysis in Japanese Patients with Idiopathic Portal Hypertension. Mediat. Inflamm. 2015, 2015, 349215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roulot, D. Liver involvement in Turner syndrome. Liver Int. 2012, 33, 24–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gravholt, C.H. Turner Syndrome and the Heart. Am. J. Cardiovasc. Drugs 2002, 2, 401–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zilz, C.K.; Brenner, J.K.; Elnecave, R.H. Portal Vein Thrombosis and High Factor VIII in Turner Syndrome. Horm. Res. Paediatr. 2006, 66, 89–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jobe, S.; Donohoue, P.; Di Paola, J. Deep Venous Thrombosis and Turner Syndrome. J. Pediatr. Hematol. 2004, 26, 272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pinto, R.B.; Silveira, T.R.; Bandinelli, E.; Röhsig, L. Portal vein thrombosis in children and adolescents: The low prevalence of hereditary thrombophilic disorders. J. Pediatr. Surg. 2004, 39, 1356–1361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hutchison, A.L.; Tavaglione, F.; Romeo, S.; Charlton, M. Endocrine aspects of metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease (MASLD): Beyond insulin resistance. J. Hepatol. 2023, 79, 1524–1541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singeap, A.-M.; Stanciu, C.; Huiban, L.; Muzica, C.M.; Cuciureanu, T.; Girleanu, I.; Chiriac, S.; Zenovia, S.; Nastasa, R.; Sfarti, C.; et al. Association between Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease and Endocrinopathies: Clinical Implications. Can. J. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2021, 2021, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Piantanida, E.; Ippolito, S.; Gallo, D.; Masiello, E.; Premoli, P.; Cusini, C.; Rosetti, S.; Sabatino, J.; Segato, S.; Trimarchi, F.; et al. The interplay between thyroid and liver: implications for clinical practice. J. Endocrinol. Investig. 2020, 43, 885–899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burt, A.D.; Gouw, A.S.H.; Callea, F.; Clouston, A.D.; Dienes, H.; Goodman, Z.D.; Kakar, S.; Kleiner, D.E.; Lackner, C.; Park, Y.N.; et al. Making Sense of ‘Porto-Sinusoidal Vascular Disorder’: What Does It Mean for the Pathologist and the Patient? Liver Int. 2024, 45, e16196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wöran, K.; Semmler, G.; Jachs, M.; Simbrunner, B.; Bauer, D.J.M.; Binter, T.; Pomej, K.; Stättermayer, A.F.; Schwabl, P.; Bucsics, T.; et al. Clinical Course of Porto-Sinusoidal Vascular Disease Is Distinct From Idiopathic Noncirrhotic Portal Hypertension. Clin. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2022, 20, e251–e266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Xiong, Q.; Zhong, Y.; Liu, D.; Liu, H.; Wang, L.; Du, Z.; Chen, M.; Zheng, Y.; Yang, Y. Clinical characteristics and natural history of porto-sinusoidal vascular disease: A cohort study of 234 patients in China. Liver Int. 2024, 44, 2329–2340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cazals-Hatem, D.; Hillaire, S.; Rudler, M.; Plessier, A.; Paradis, V.; Condat, B.; Francoz, C.; Denninger, M.-H.; Durand, F.; Bedossa, P.; et al. Obliterative portal venopathy: Portal hypertension is not always present at diagnosis. J. Hepatol. 2010, 54, 455–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siramolpiwat, S.; Seijo, S.; Miquel, R.; Berzigotti, A.; Garcia-Criado, A.; Darnell, A.; Turon, F.; Hernandez-Gea, V.; Bosch, J.; Garcia-Pagán, J.C. Idiopathic portal hypertension: Natural history and long-term outcome. Hepatology 2013, 59, 2276–2285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hollande, C.; Mallet, V.; Darbeda, S.; Vallet-Pichard, A.; Fontaine, H.; Verkarre, V.; Sogni, P.; Terris, B.; Gouya, H.; Pol, S. Impact of Obliterative Portal Venopathy Associated With Human Immunodeficiency Virus. Medicine 2016, 95, e3081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schouten, J.N.L.; Van der Ende, M.E.; Koëter, T.; Rossing, H.H.M.; Komuta, M.; Verheij, J.; van der Valk, M.; Hansen, B.E.; Janssen, H.L.A. Risk factors and outcome of HIV-associated idiopathic noncirrhotic portal hypertension. Aliment. Pharmacol. Ther. 2012, 36, 875–885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guido, M.; Sarcognato, S.; Sonzogni, A.; Lucà, M.G.; Senzolo, M.; Fagiuoli, S.; Ferrarese, A.; Pizzi, M.; Giacomelli, L.; Colloredo, G. Obliterative portal venopathy without portal hypertension: an underestimated condition. Liver Int. 2015, 36, 454–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kawabata, S.; Sakamoto, S.; Honda, M.; Hayashida, S.; Yamamoto, H.; Mikami, Y.; Inomata, Y. Liver transplantation for a patient with Turner syndrome presenting severe portal hypertension: a case report and literature review. Surg. Case Rep. 2016, 2, 68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elsheikh, M.; Hodgson, H.J.F.; Wass, J.A.H.; Conway, G.S. Hormone replacement therapy may improve hepatic function in women with Turner's syndrome. Clin. Endocrinol. 2001, 55, 227–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wójcik, M.; Ruszała, A.; Januś, D.; Starzyk, J.B. Liver Biochemical Abnormalities in Adolescent Patients with Turner Syndrome. J. Clin. Res. Pediatr. Endocrinol. 2019, 11, 395–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santi, M.; Flück, C.E.; Hauschild, M.; Kuhlmann, B.; Kuehni, C.E.; Sommer, G. Health behaviour of women with Turner Syndrome. Acta Paediatr. 2021, 110, 2424–2429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Case 1 | Case 2 | Case 3 | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age(years) | 22 | 30 | 23 | ||||||

| Labor(weeks) | 38 | 41 | 40 | ||||||

| Menarche (years) | 12 | 17 | 12 (induction) | ||||||

|

Puberty (Tanner stages) |

AH=III, PH=V, B=V | AH=II, PH=IV, B=III | AH=III, PH=V, B=V | ||||||

| Body height (cm) | 145 | 153 | 150 | ||||||

| Medical history | astigmatism hypermetropia strabismus iron deficiency anemia |

astigmatism hypermetropia strabismus osteopenia dyslipidemia |

constriction of aorta chronic autoimmune thyroiditis gonadal dysgenesis osteopenia insulin resistance hearing loss |

||||||

| Karyotype test | 45,XO | 45,XO/46,XX (fragment 80%/20%) |

45,XO | ||||||

| Phenotype characteristics | short stature, broad short neck, low hairline, deformity of external ears, broad chest | short stature, short, webbed neck, low hairline, low-set ears | short stature, short, webbed neck, low hairline, ear deformity, shield-shaped thorax, widely spaced nipples | ||||||

| Ht (%) | 38 | 38.6 | 39.4 | ||||||

| Hb (g/dl) | 11.5 | 12.8 | 13.7 | ||||||

| WBC (cells/μl) | 7620 | 6930 | 4630 | ||||||

| PLTs (cells/μl) | 528000 | 190000 | 189000 | ||||||

| AST (5-32U/L) | 86 | 34 | 53 | ||||||

| ALT (5-31 U/L) | 106 | 37 | 130 | ||||||

| γ-GT (5-36 U/L) | 98 | 58 | 87 | ||||||

| ALP (35-120 U/L) | 125 | 149 | 71 | ||||||

| Total bilirubin (mg/dl) | 0,8 | 0.5 | 0.4 | ||||||

| Ferritin (ng/ml) | 13 | 120 | 32 | ||||||

| Glucose (mg/dl) | 81 | 92 | 93 | ||||||

| HBsAg | (-) | (-) | (-) | ||||||

| Anti-HBc | (-) | (-) | (-) | ||||||

| Anti-HBs | (+) | (+) | (+) | ||||||

| Anti-HCV | (-) | (-) | (-) | ||||||

| ANA | (-) | (-) | (-) | ||||||

| AMA | (-) | (-) | (-) | ||||||

| ASMA | (-) | (-) | (-) | ||||||

| IgG | N | N | N | ||||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).