Submitted:

04 April 2025

Posted:

08 April 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results and Discussion

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Cybersecurity & Infrastructure Security Agency. Available online: https://www.cisa.gov/sites/default/files/publications/pt_active_shooter_how-to-respond-508.pdf (accessed on 14 October 2023).

- Puryear, B.; Gnugnoli, D.M. Emergency Preparedness. In StatPearls [Internet]; StatPearls Publishing: Treasure Island, FL, USA, 2023. Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/30725727/ (accessed on 15 October 2023).

- Schwerin, D.L.; Thurman, J.; Goldstein, S. Active Shooter Response. National Center for Biotechnology Information, National Library of Medicine. 2024. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK519067/ (accessed on 14 October 2024).

- Capellan, J.A. Lone wolf terrorist or deranged shooter? A study of ideological active shooter events in the United States, 1970–2014. Stud. Confl. Terror. 2015, 38, 395–413. (accessed on 6 November 2023). [CrossRef]

- Skerlak, R.D. Massacres Escolares e Cultura: Um Estudo do Massacre de Columbine com Base em Artigos Jornalísticos e do Documentário Tiros em Columbine; Course Completion Work to obtain a bachelor's degree in psychology. Pontifícia Universidade Católica de São Paulo: São Paulo, Brazil, 2020.

- ElPaís. Columbine, Realengo e Suzano, os mais sangrentos massacres nas escolas de Brasil e EUA. ElPaís 2019. Available online: https://brasil.elpais.com/brasil/2019/03/13/internacional/1552503550_809750.html (accessed on 19 November 2024).

- DW Made for Minds. O que se sabe sobre o atentado a faca em São Paulo. DW Made for Minds 2023. Available online: https://www.dw.com/pt-br/o-que-se-sabe-sobre-o-ataque-a-faca-em-escola-de-sp/a-65144511 (accessed on 19 November 2024).

- Lima, A.H.S.; Coelho, F.M. Aprimoramento da defesa pessoal como último recurso para lutar contra agressores ativos em escolas do Paraná. Recima21-Rev. Cient. Multidiscip. 2023, 4, 1–14. [CrossRef]

- Zullig, K.J. Active Shooter Drills: A Closer Look at Next Steps. J. Adolesc. Health 2020, 67, 465–466. (accessed on 15 October 2023). [CrossRef]

- Moore-Petinak, N.; Waselewski, M.; Patterson, B.A.; Chang, T. Active Shooter Drills in the United States: A National Study of Youth Experiences and Perceptions. J. Adolesc. Health 2020, 67, 509–513. Available online: https://www.jahonline.org/article/S1054-139X(20)30320-7/fulltext (accessed on 20 November 2023). [CrossRef]

- Berglund, D. When The Shooting Stops: Recovery From Active-Shooter Events For K-12 Schools. 2017. Available online: https://www.hsaj.org/articles/14382 (accessed on 18 December 2023).

- Liu, R.; Becerik-Gerber, B.; Lucas, G.M. Effectiveness of VR-based training on improving occupants’ response and preparedness for active shooter incidents. Saf. Sci. 2023, 164, 106175. (accessed on 6 November 2023). [CrossRef]

- Zhu, R.; Lucas, G.M.; Becerik-Gerber, B.; et al. The impact of security countermeasures on human behavior during active shooter incidents. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 929. (accessed on 15 October 2023). [CrossRef]

- Lavalle-Rivera, J.; Ramesh, A.; Harris, L.M.; Chakraborty, S. The effectiveness of naive optimization of the egress path for an active-shooter scenario. Heliyon 2023, 9, e13695. (accessed on 15 October 2023). [CrossRef]

- Livingston, C.; Grombly, A. Thinking About the Unthinkable: Active Shooter Preparedness in Library Environments. Libr. Lead. Manag. 2020, 35, 10.5860/llm.v35i1.7426. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/348443601 (accessed on 20 November 2023). [CrossRef]

- Arteaga, C.; Park, J.W.; Morris, B.T.; Sharma, S. Effect of Trained Evacuation Leaders on Victims’ Safety During an Active Shooter Incident. SSRN 2023. Available online: https://ssrn.com/abstract=4171892 (accessed on 6 November 2023).

- Haghpanah, F.; Ghobadi, K.; Schafer, B.W. Multi-Hazard Hospital Evacuation Planning During Disease Outbreaks Using Agent-Based Modeling. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct. 2021, 66, 102632. (accessed on 15 October 2023). [CrossRef]

- Kenney, K.; Nguyen, K.; Konecki, E.; Jones, C.; Kakish, E.; Fink, B.; Rega, P.P. What Do Emergency Department Patients and Their Guests Expect From Their Health Care Provider in an Active Shooter Event? WMJ 2020, 119(2), 96-101. Available online: https://wmjonline.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/119/2/96.pdf (accessed on 15 October 2023).

- Inaba, K.; Eastman, A.L.; Jacobs, L.M.; Mattox, K.L. Active-Shooter Response at a Health Care Facility. N. Engl. J. Med. 2018, 379(6), 583-586. (accessed on 16 October 2023). [CrossRef]

- Iserson, K.V.; Heine, C.E.; Larkin, G.L.; Moskop, J.C.; Baruch, J.; Aswegan, A.L. Fight or Flight: The Ethics of Emergency Physician Disaster Response. Ann. Emerg. Med. 2008, 51(4), 345-353. (accessed on 23 October 2023). [CrossRef]

- Jager, E.; Goralnick, E.; McCarty, J.C.; Hashmi, Z.G.; Jarman, M.P.; Haider, A.H. Lethality of Civilian Active Shooter Incidents With and Without Semiautomatic Rifles in the United States. JAMA 2018, 320(10), 1034-1035. (accessed on 15 October 2023). [CrossRef]

- Seebock, J.J. Responding to High-Rise Active Shooters. Defense Technical Information Center 2018. Available online: https://apps.dtic.mil/sti/citations/AD1069735 (accessed on 18 December 2023).

- Usero-Pérez, C.; González Alonso, V.; Orbañanos Peiro, L.; Gómez Crespo, J.M.; Hossain López, S. Implementación de las Recomendaciones del Consenso de Hartford y Tactical Emergency Casualty Care (TECC) en los Servicios de Emergencia: Revisión Bibliográfica. Emergencias 2017, 29(6), 416-421. Available online: https://emergencias.portalsemes.org/descargar/implementacin-de-las-recomendaciones-del-consenso-de-hartford-y-tactical-emergency-casualty-care-tecc-en-los-servicios-de-emergencia-revisin-bibliogrfica/ (accessed on 23 October 2023).

- Jacobs, L.M.; McSwain, N.E. Jr.; Rotondo, M.F.; Wade, D.; Fabbri, W.; Eastman, A.L.; Butler, F.K. Jr.; Sinclair, J.; Joint Committee to Create a National Policy to Enhance Survivability from Mass Casualty Shooting Events. Improving Survival from Active Shooter Events: The Hartford Consensus. J. Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2013, 74(6), 1399-1400. (accessed on 6 November 2023). [CrossRef]

- Blair, J.P.; Schweit, K.W. A Study of Active Shooter Incidents, 2000-2013; Texas State University and Federal Bureau of Investigation, U.S. Department of Justice: Washington D.C., USA, 2014. Available online: https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED594362.pdf (accessed on 19 February 2024).

- Anklam, C.; et al. Mitigating Active Shooter Impact; Analysis for Policy Options Based on Agent/Computer-Based Modeling, 2014. Available online: https://foac-illea.org/uploads/reports_studies/2014-09-Dealing_With_Active_Shooters-Purdue_Research_Paper-Compr.pdf (accessed on 26 February 2024).

- Kelleher, M.D. Perfil do Funcionário Letal: Estudos de Caso de Violência no Local de Trabalho; Bloomsbury Publishing USA: 1997.

- Cohen, A.P.; Azrael, D.; Miller, M. Rate of Mass Shootings Has Tripled Since 2011. Mother Jones, 14 October 2014. Available online: https://www.motherjones.com/politics/2014/10/mass-shootings-increasing-harvard-research/. (accessed on 26 February 2024).

- Blair, J.P.; Schweit, K.W. A Study of Active Shooter Incidents, 2000-2013; Texas State University and Federal Bureau of Investigation, U.S. Department of Justice: Washington D.C., USA, 2014. Available online: https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED594362.pdf (accessed on 19 February 2024).

- Brasil. Ministério da Educação. Relatório: Ataque às Escolas no Brasil. Available online: https://www.gov.br/mec/pt-br/acesso-a-informacao/participacao-social/grupos-de-trabalho/prevencao-e-enfrentamento-da-violencia-nas-escolas/resultados/relatorio-ataque-escolas-brasil.pdf (accessed on 1 December 2024).

- BRASIL. Ministério da Educação. Relatório: ataque às escolas no Brasil. Available online: https://www.gov.br/mec/pt-br/acesso-a-informacao/participacao-social/grupos-de-trabalho/prevencao-e-enfrentamento-da-violencia-nas-escolas/resultados/relatorio-ataque-escolas-brasil.pdf (accessed on 1 December 2024).

- BRASIL. Ministério da Educação. Relatório: ataque às escolas no Brasil. Available online: https://www.gov.br/mec/pt-br/acesso-a-informacao/participacao-social/grupos-de-trabalho/prevencao-e-enfrentamento-da-violencia-nas-escolas/resultados/relatorio-ataque-escolas-brasil.pdf (accessed on 1 December 2024).

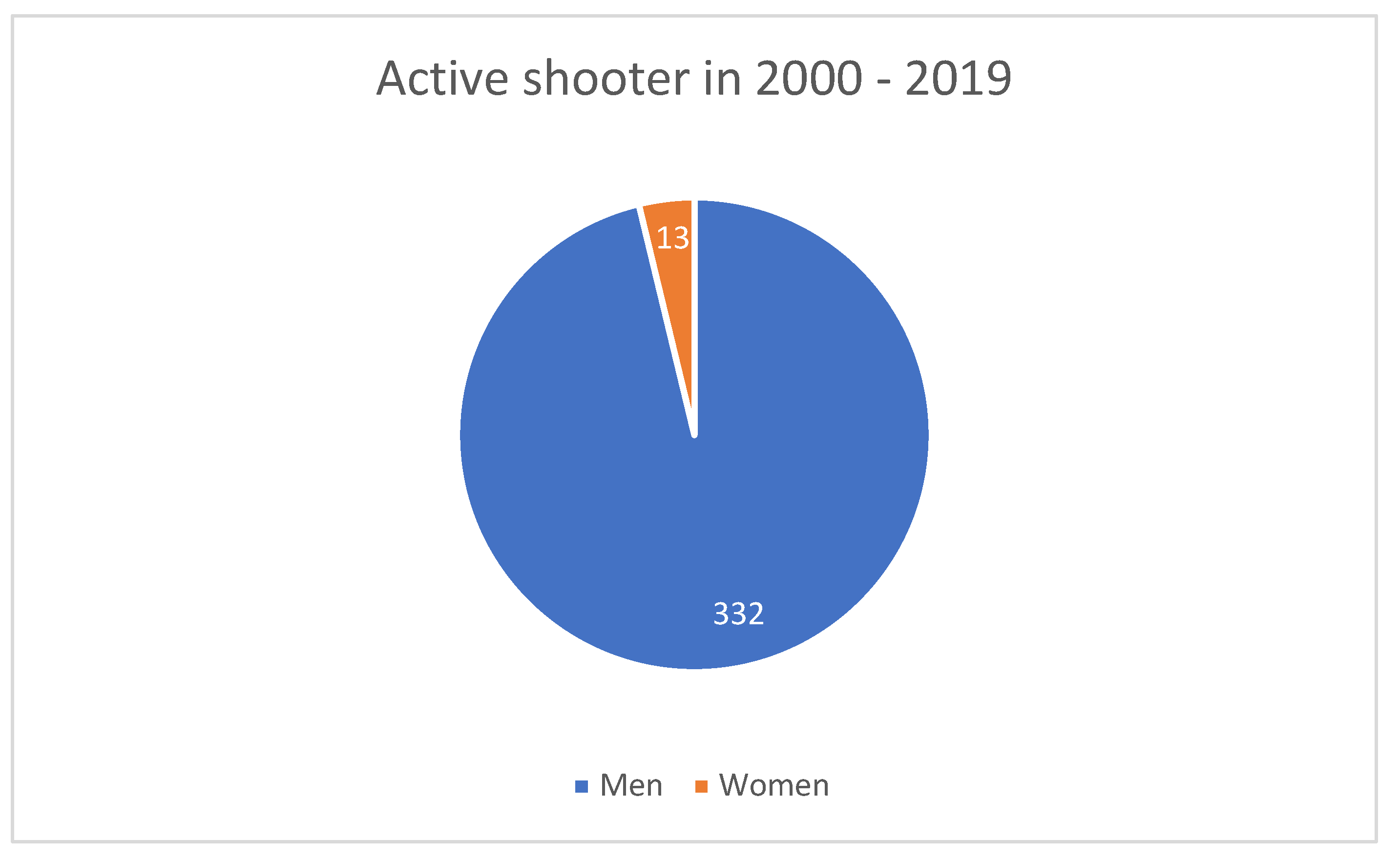

- Federal Bureau of Investigation. Active Shooter Incidents 20-Year Review, 2000–2019. Available online: https://www.fbi.gov/file-repository/active-shooter-incidents-20-year-review-2000-2019-060121.pdf/view (accessed on 18 March 2024).

- Bonanno, C.M.; Levenson Jr, R.L. School shooters: History, current theoretical and empirical findings, and strategies for prevention. Sage Open 2014, 4, 2158244014525425. Available online: https://scispace.com/pdf/school-shooters-history-current-theoretical-and-empirical-29nv5dwrik.pdf (accessed on 18 March 2024).

- Duque, R.B.; LeBlanc, E.J.; Rivera, R. Prevendo eventos de atiradores ativos: homogeneidade regional, intolerância, vidas monótonas e mais armas são dissuasão suficiente? Crime & Delinquency 2019, 65, 1218–1261. (accessed on 18 March 2024). [CrossRef]

- Twenge, J.M. iGen: Why today's super-connected kids are growing up less rebellious, more tolerant, less happy—and completely unprepared for adulthood—and what that means for the rest of us; Simon and Schuster: New York, NY, USA, 2017.

- Navarro, J.N.; Jasinski, J.L. Going cyber: Using routine activities theory to predict cyberbullying experiences. Sociological Spectrum 2012, 32, 81–94. (accessed on 17 March 2024). [CrossRef]

- Blair, J.P.; Schweit, K.W. A Study of Active Shooter Incidents, 2000–2013; Texas State University and Federal Bureau of Investigation, U.S. Department of Justice: Washington, DC, USA, 2014. Available online: https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED594362.pdf (accessed on 19 February 2024).

- Sanchez, L.; Young, V.B.; Baker, M. Active Shooter Training in the Emergency Department: A safety initiative. J. Emerg. Nurs. 2018, 44, 598–604. (accessed on 24 November 2024). [CrossRef]

- Huskey, M.G.; Connell, N.M. Preparation or Provocation? Student Perceptions of Active Shooter Drills. Crim. Justice Policy Rev. 2020, 32, 3–26. (accessed on 24 November 2024). [CrossRef]

- Mazer, J.P.; Thompson, B.; Cherry, J.; Russell, M.; Payne, H.J.; Kirby, E.G.; Pfohl, W. Communication in the face of a school crisis: Examining the volume and content of social media mentions during active shooter incidents. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2015, 53, 238–248. (accessed on 14 November 2024). [CrossRef]

- Department of Homeland Security. Active Shooter Preparedness. Available online: https://www.dhs.gov/active-shooter-preparedness (accessed on 24 November 2024).

- Martins, J.A.S.; Martins, F.S.F. A importância da aplicação do protocolo “Fugir, Esconder ou Lutar” como resposta ao incidente de atirador ativo. Rev. Inst. Bras. Segur. Pública 2023, 6, 1–28. Available online: https://revista.ibsp.org.br/index.php/RIBSP/article/view/200/162 (accessed on 14 November 2024).

- Kerr, S.E.M. Managing Active Shooter Events in Schools: An Introduction to Emergency Management. Laws 2024, 13, 42. (accessed on 18 March 2025). [CrossRef]

- Sousa, J.E.P.; Neto, O.G.O.; De Oliveira, J.V.; Sales, R.C.C. Atirador em Massa: Ações para Sobrevivência de Civis; Editora In Vivo: Fortaleza, Brazil, 2021.

- Briggs, T.W.; Kennedy, W.G. Active shooter: An agent-based model of unarmed resistance. Proceedings of the 2016 Winter Simulation Conference (WSC), [S.L.], 3521–3531, December 2016; IEEE. (accessed on 15 November 2024). [CrossRef]

| 1 |

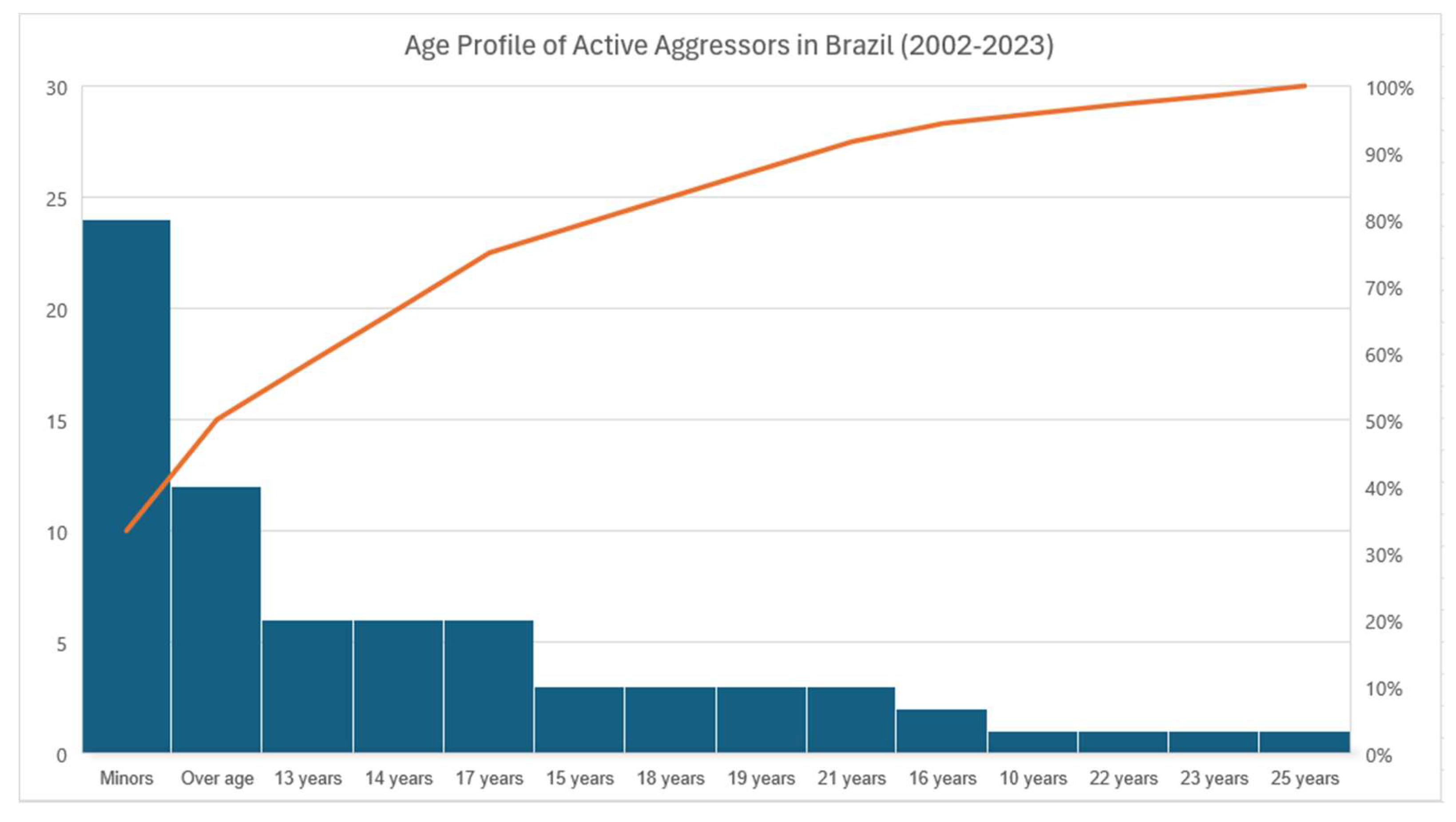

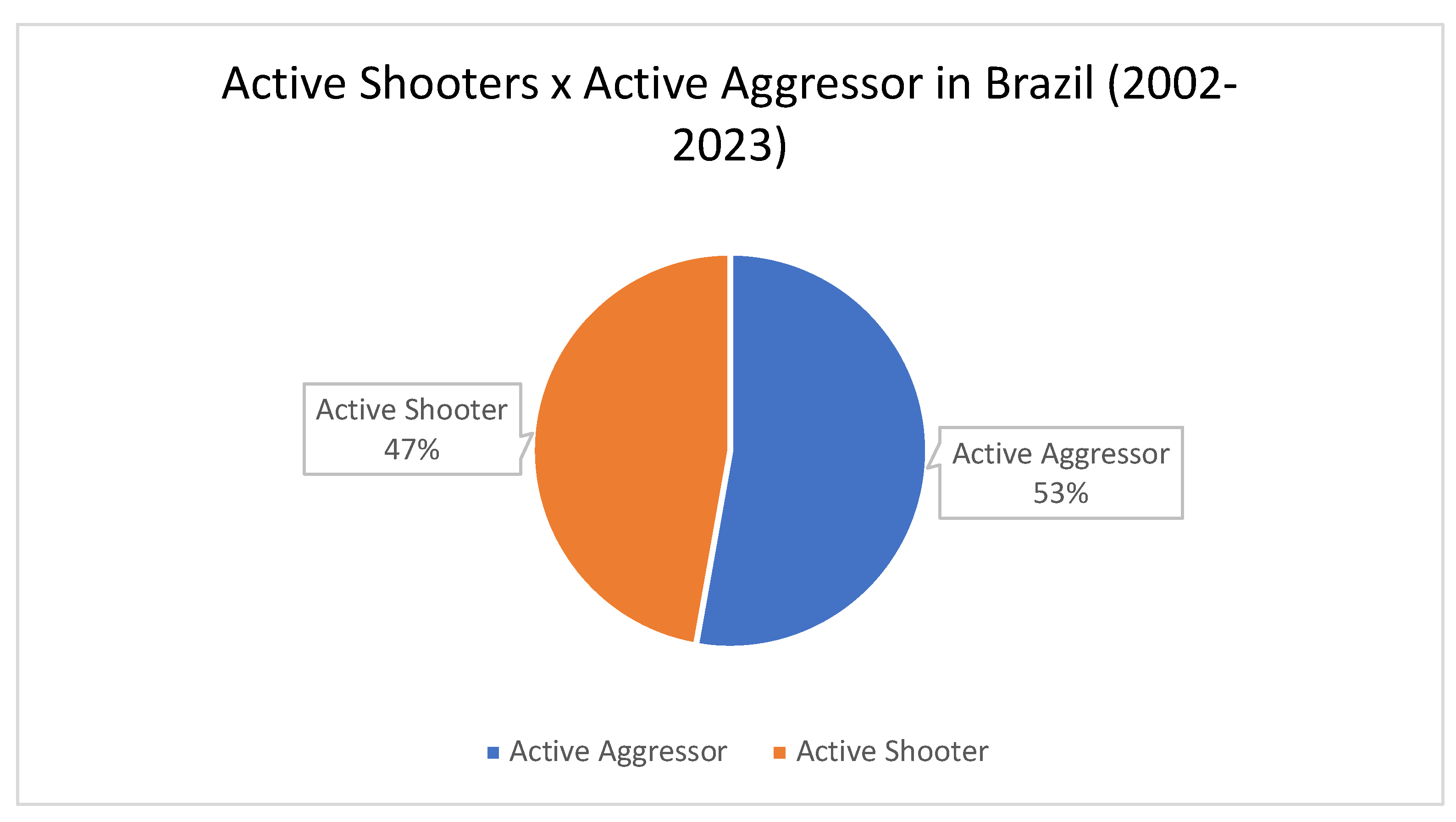

| Year | UF | City | Main weapon | Dead | Injured | Age of the attacker | Type of Aggressor | Total | |

| 1 | 2002 | BA | Salvador | Firearm | 2 | 0 | 17 years | Active Shooter | 2 |

| 2 | 2003 | SP | Taiuva | Firearm | 1 | 8 | 18 years | Active Shooter | 9 |

| 3 | 2011 | RJ | Realengo | Firearm | 13 | 22 | 23 years | Active Shooter | 35 |

| 4 | 2011 | SP | São Caetano do Sul | Firearm | 1 | 1 | 10 years | Active Shooter | 2 |

| 5 | 2012 | PB | Santa Rita | Firearm | 0 | 3 | 21 years | Active Shooter | 3 |

| 6 | 2017 | GO | Alexânia | Firearm | 1 | 0 | 19 years | Active Shooter | 1 |

| 7 | 2017 | GO | Goiânia | Firearm | 2 | 4 | 14 years | Active Shooter | 6 |

| 8 | 2018 | PR | Medianeira | Firearm | 0 | 2 | 15 years | Active Shooter | 2 |

| 9 | 2019 | SP | Suzano | Firearm | 9 | 11 | 17 years | Active Shooter | 20 |

| 10 | 2019 | MG | Caraí | Firearm | 0 | 2 | 17 years | Active Shooter | 2 |

| 11 | 2019 | RS | Charqueadas | Bladed Weapon | 0 | 7 | 17 years | Active Aggressor | 7 |

| 12 | 2021 | SP | Americana | Air gun | 0 | 1 | 13 years | Active Shooter | 1 |

| 13 | 2021 | SC | Saudades | Bladed Weapon | 5 | 2 | 18 years | Active Aggressor | 7 |

| 14 | 2022 | RJ | Rio de Janeiro | Bladed Weapon | 0 | 4 | 14 years | Active Aggressor | 4 |

| 15 | 2022 | ES | Vitória | Crossbow | 0 | 1 | 18 years | Active Aggressor | 1 |

| 16 | 2022 | BA | Morro do Chapéu | Bladed Weapon | 0 | 1 | 13 years | Active Aggressor | 1 |

| 17 | 2022 | BA | Barreiras | Firearm | 1 | 1 | 14 years | Active Shooter | 2 |

| 18 | 2022 | CE | Sobral | Firearm | 1 | 2 | 15 years | Active Shooter | 3 |

| 19 | 2022 | ES | Aracruz | Firearm | 4 | 12 | 16 years | Active Shooter | 16 |

| 20 | 2022 | SP | Ipaussu | Bladed Weapon | 0 | 2 | 22 years | Active Aggressor | 2 |

| 21 | 2023 | SP | Monte Mor | Explosive | 0 | 0 | 17 years | Active Aggressor | 0 |

| 22 | 2023 | PA | Belém | Bladed Weapon | 0 | 1 | 17 years | Active Aggressor | 1 |

| 23 | 2023 | SP | São Paulo | Bladed Weapon | 1 | 5 | 13 years | Active Aggressor | 6 |

| 24 | 2023 | SC | Blumenau | Bladed Weapon | 4 | 5 | 25 years | Active Aggressor | 9 |

| 25 | 2023 | AM | Manaus | Bladed Weapon | 0 | 3 | 13 years | Active Aggressor | 3 |

| 26 | 2023 | GO | Santa Tereza de Goiás | Bladed Weapon | 0 | 3 | 13 years | Active Aggressor | 3 |

| 27 | 2023 | CE | Farias Brito | Bladed Weapon | 0 | 2 | 14 years | Active Aggressor | 2 |

| 28 | 2023 | SP | Morungaba | Bladed Weapon | 0 | 0 | 19 years | Active Aggressor | 0 |

| 29 | 2023 | MS | Campo Grande | Bladed Weapon | 0 | 1 | 19 years | Active Aggressor | 1 |

| 30 | 2023 | MA | Caxias | Firearm | 0 | 0 | 16 years | Active Shooter | 0 |

| 31 | 2023 | RJ | Rio de janeiro | Bladed Weapon | 0 | 1 | 15 years | Active Aggressor | 1 |

| 32 | 2023 | AL | Arapiraca | Glass | 0 | 1 | 21 years | Active Aggressor | 1 |

| 33 | 2023 | PR | Cambé | Firearm | 2 | 0 | 21 years | Active Shooter | 2 |

| 34 | 2023 | MG | Poços de Caldas | Bladed Weapon | 1 | 3 | 14 years | Active Aggressor | 4 |

| 35 | 2023 | SP | São Paulo | Firearm | 1 | 3 | 13 years | Active Shooter | 4 |

| 36 | 2023 | CE | Fortaleza | Bladed Weapon | 0 | 1 | 14 years | Active Aggressor | 1 |

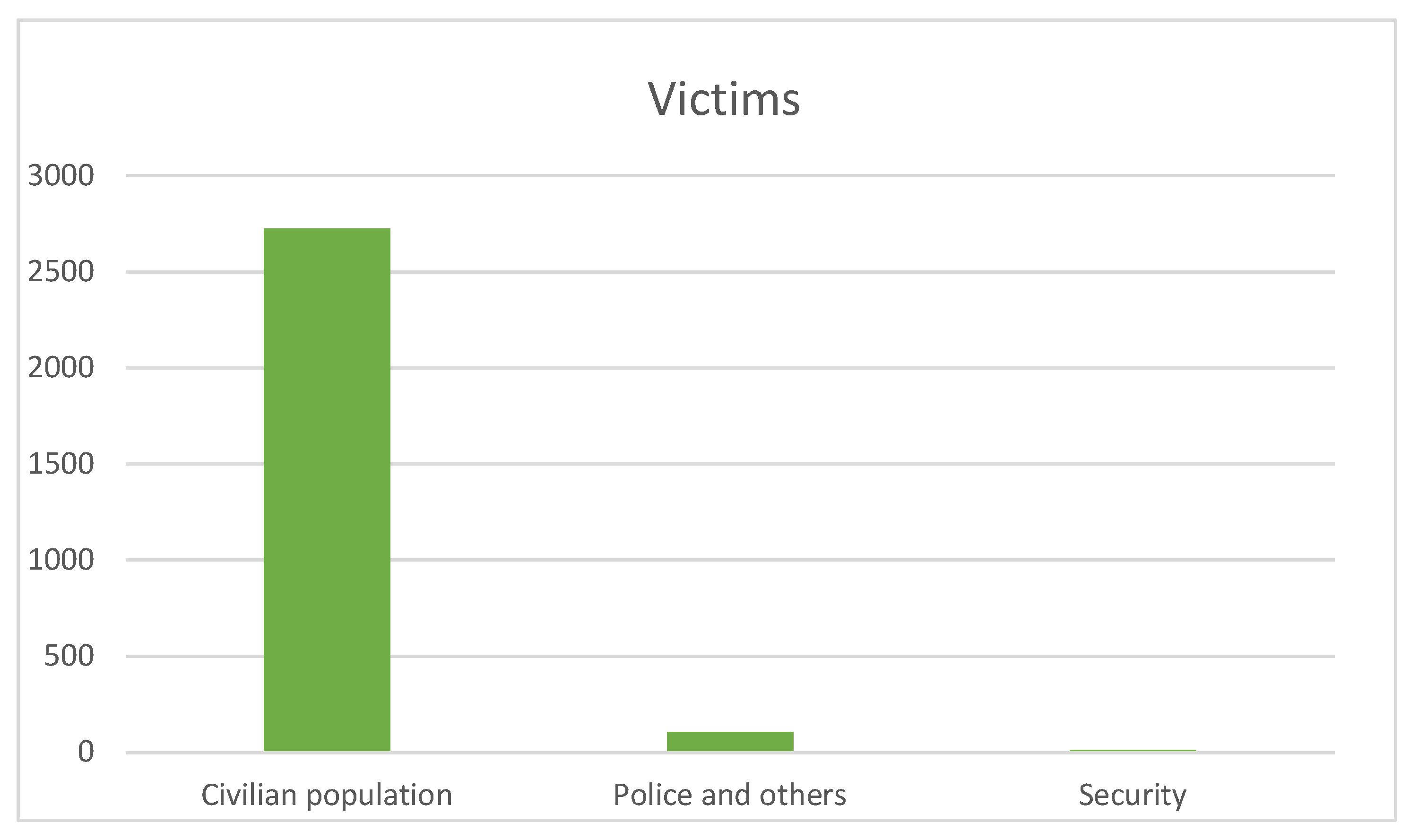

| Total | 49 | 115 | - | 164 | |||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).