Submitted:

07 April 2025

Posted:

08 April 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Data Sources and Search Strategy

2.2. Study Selection

2.3. Data Extraction

2.4. Methodological Quality Assessment

2.5. Risk of Bias Assessment

2.6. Grade of Recommendation

3. Results

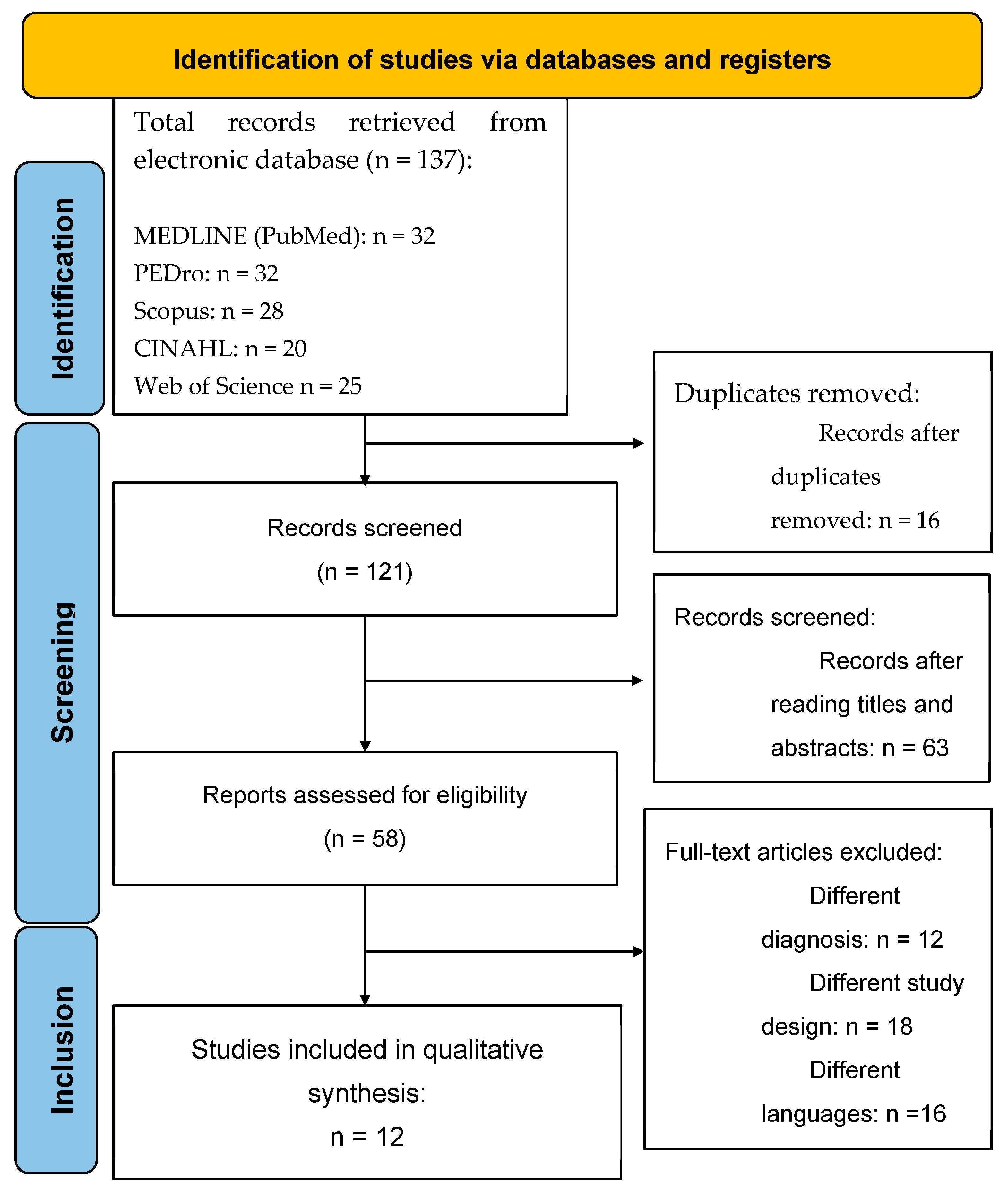

3.1. Study Selection

3.2. Characteristics of the Included Studies

3.3. Methodological Quality Assessment

| Year, Author | Score | Quality | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 |

| Tran et al. (2016) [40] | 10 | Excellent | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Haugue et al. (2015) [41] | 7 | Good | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Araki et al. (2012) [42] | 6 | Good | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | No | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Skovbjerg et al. (2012) [43] | 5 | Acceptable | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | No | No | No | No | Yes |

| Sampalli et al. (2009) [44] | 3 | Low | Yes | No | No | Yes | No | No | No | No | No | Yes | Yes |

3.3.1. Case Series

| Year, Author | Score | Quality | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 |

| Amin & Forslund (2018) [39] | 7/9 | Good | + | + | + | ? | + | + | + | + | ? | NA |

| Guglielmi et al. (1994) [48] | 5/9 | Acceptable | - | ? | ? | + | + | + | - | + | + | NA |

3.3.2. Case Reports

| Year, Author | Score | Quality | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 |

| Woolfolk et al (2018) [38] | 9/9 | Good | + | + | + | + | + | + | ? | + | + | + |

| Elberling et al. (2010) [44] | 6/9 | Acceptable | + | + | + | ? | ? | - | - | + | + | + |

| Busse et al (2008) [46] | 7/9 | Good | + | + | + | + | - | - | - | + | + | + |

| Stenn et al (1998) [47] | 7/9 | Good | + | + | + | + | ? | ? | - | + | + | + |

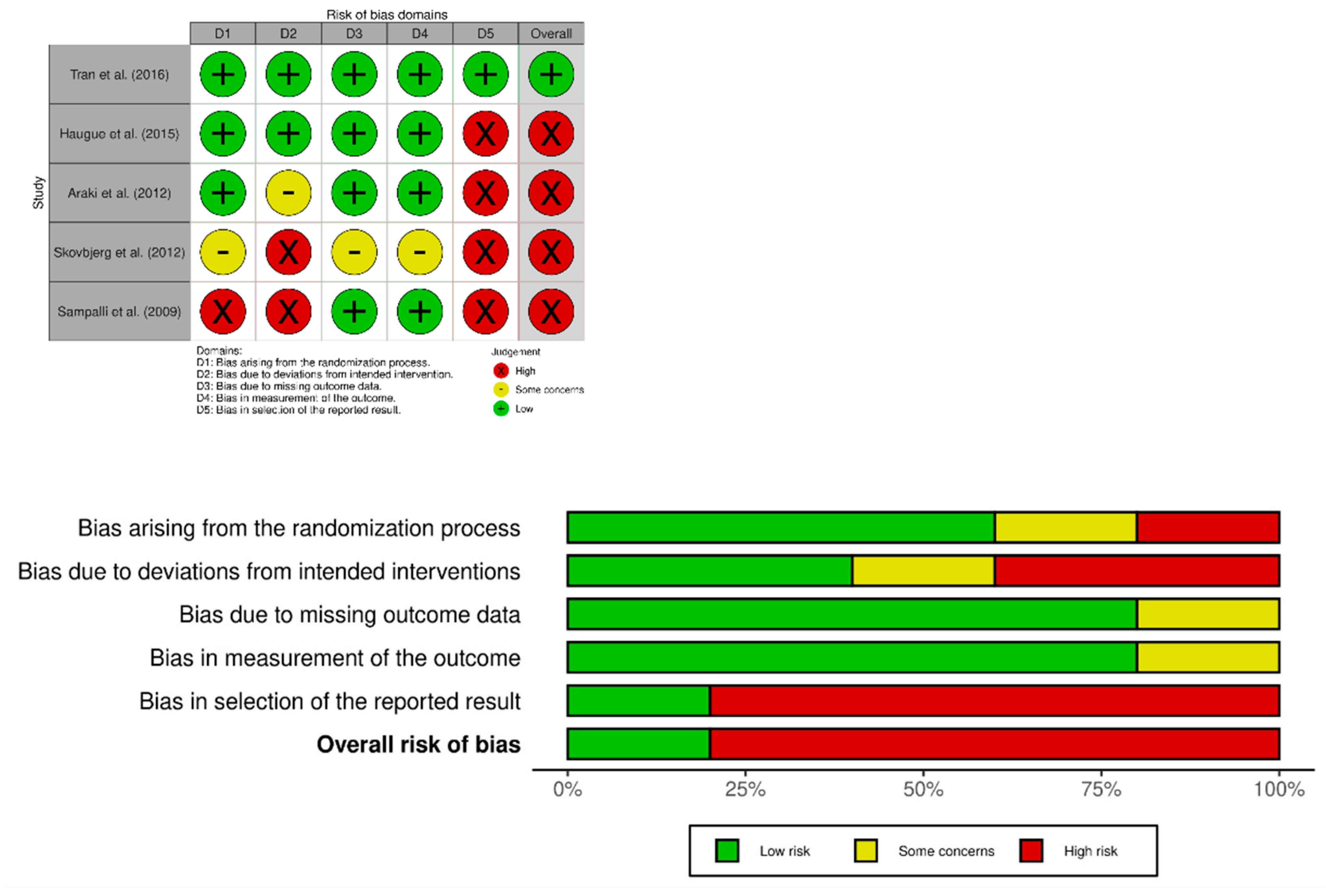

3.4. Risk of Bias Analysis

3.5. Synthesis of Main Results

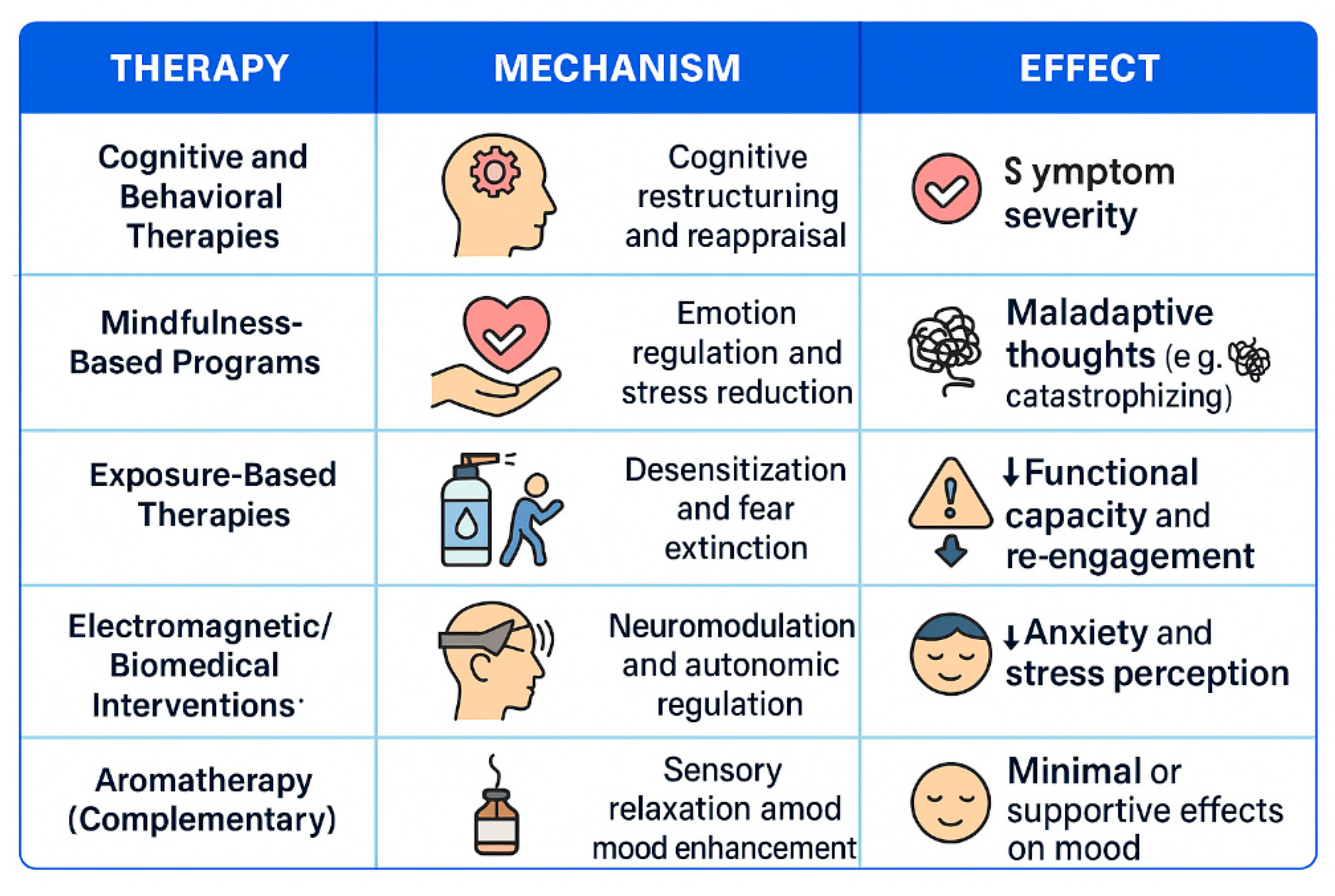

3.5.1. Cognitive Behavioral Therapy in Reducing MCS Symptoms

3.5.2. Mindfulness-Based Therapy in Reducing MCS Symptoms

3.5.3. Exposure-Based Therapies in Reducing MCS Symptoms

3.5.4. Electromagnetic and Biomedical Therapies

3.5.5. Complementary Interventions in Reducing MCS Symptoms

4. Discussion

4.1. Clinical Implications and Future Research Directions

4.2. Limitations

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Rossi, S.; Pitidis, A. Multiple Chemical Sensitivity: Review of the State of the Art in Epidemiology, Diagnosis, and Future Perspectives. J. Occup. Environ. Med. 2018, 60, 138–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Del Casale, A.; Ferracuti, S.; Mosca, A.; Pomes, L.M.; Fiaschè, F.; Bonanni, L.; Borro, M.; Gentile, G.; Martelletti, P.; Simmaco, M. Multiple Chemical Sensitivity Syndrome: A Principal Component Analysis of Symptoms. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 6551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacques, L. Multiple Chemical Sensitivity: A Clinical Perspective. Brain Sci. 2024, 14, 1261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cullen, M.R. The Worker with Multiple Chemical Sensitivities: An Overview. Occup. Med. (Chic. Ill.) 1987, 2, 655–661. [Google Scholar]

- Steinemann, A. National Prevalence and Effects of Multiple Chemical Sensitivities. J. Occup. Environ. Med. 2018, 60, e152–e156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caress, S.M.; Steinemann, A.C. National Prevalence of Asthma and Chemical Hypersensitivity: An Examination of Potential Overlap. J. Occup. Environ. Med. 2005, 47, 518–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alameda Cuesta, A.; Pazos Garciandía, Á.; Oter Quintana, C.; Losa Iglesias, M.E. Fibromyalgia, Chronic Fatigue Syndrome, and Multiple Chemical Sensitivity: Illness Experiences. Clin. Nurs. Res. 2021, 30, 32–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meggs, W.J. Mechanisms of Allergy and Chemical Sensitivity. Toxicol. Ind. Health 1999, 15, 331–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bell, I.R. Clinically Relevant EEG Studies and Psychophysiological Findings: Possible Neural Mechanisms for Multiple Chemical Sensitivity. Toxicology 1996, 111, 101–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zucco, G.M.; Doty, R.L. Multiple Chemical Sensitivity. Brain Sci. 2022, 12, 46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suzuki, K.; Okamura, M.; Haruyama, Y.; Suzuki, S.; Shiina, T.; Kobashi, G.; Hirata, K. Exploring the Contributing Factors to Multiple Chemical Sensitivity in Patients with Migraine. J. Occup. Health 2022, 64, e12328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Molot, J.; Sears, M.; Marshall, L.M.; Bray, R.I. Neurological Susceptibility to Environmental Exposures: Pathophysiological Mechanisms in Neurodegeneration and Multiple Chemical Sensitivity. Rev. Environ. Health 2022, 37, 509–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Winder, C. Mechanisms of Multiple Chemical Sensitivity. Toxicol. Lett. 2002, 128, 85–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Driesen, L.; Patton, R.; John, M. The Impact of Multiple Chemical Sensitivity on People's Social and Occupational Functioning: A Systematic Review of Qualitative Research Studies. J. Psychosom. Res. 2020, 132, 109964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koch, L.; Vierstra, C.; Penix, K. A Qualitative Investigation of the Psychosocial Impact of Multiple Chemical Sensitivity. J. Appl. Rehabil. Couns. 2006, 37, 33–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molot, J.; Sears, M.; Anisman, H. Multiple Chemical Sensitivity: It's Time to Catch Up to the Science. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 2023, 151, 105227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palmieri, B.; Corazzari, V.; Vadalà, M.; Vallelunga, A.; Morales-Medina, J.C.; Iannitti, T. The Role of Sensory and Olfactory Pathways in Multiple Chemical Sensitivity. Rev. Environ. Health 2021, 36, 319–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viziano, A.; Micarelli, A.; Alessandrini, M. Noise Sensitivity and Hyperacusis in Patients Affected by Multiple Chemical Sensitivity. Int. Arch. Occup. Environ. Health 2017, 90, 189–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aguilar-Aguilar, E.; Marcos-Pasero, H.; de la Iglesia, R.; Espinosa-Salinas, I.; de Molina, A.R.; Reglero, G.; Loria-Kohen, V. Characteristics and Determinants of Dietary Intake and Physical Activity in a Group of Patients with Multiple Chemical Sensitivity. Endocrinol. Diabetes Nutr. 2018, 65, 564–570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark, I. When Avoiding Chemicals Means Avoiding Others: Relational Exposures and Multiple Chemical Sensitivity. Soc. Sci. 2024, 13, 528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gargano, D.; Appanna, R.; Santonicola, A.; De Bartolomeis, F.; Stellato, C.; Cianferoni, A.; et al. Food Allergy and Intolerance: A Narrative Review on Nutritional Concerns. Nutrients 2021, 13, 1638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serrat, M.; Sanabria-Mazo, J.P.; Almirall, M.; Musté, M.; Feliu-Soler, A.; Méndez-Ulrich, J.L.; et al. Effectiveness of a Multicomponent Treatment Based on Pain Neuroscience Education, Therapeutic Exercise, Cognitive Behavioral Therapy, and Mindfulness in Patients with Fibromyalgia (FIBROWALK Study): A Randomized Controlled Trial. Phys. Ther. 2021, 101, pzab200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van den Bergh, O.; Bräscher, A.K.; Witthöft, M. Idiopathic Environmental Intolerance: A Treatment Model. Cogn. Behav. Pract. 2021, 28, 281–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lavric, C.E.; Migueres, N.; de Blay, F. Multiple Chemical Sensitivity: A Review of Its Pathophysiology. Explor. Asthma Allergy 2024, 2, 350–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Binkley, K.E. Multiple Chemical Sensitivity/Idiopathic Environmental Intolerance: A Practical Approach to Diagnosis and Management. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. Pract. 2023, 11, 3645–3649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pigatto, P.D.; Rossi, V.; Guzzi, G. Dietary factors and endocrine consequences of multiple chemical sensitivity. Endocrinol. Diabetes Nutr. 2020, 67, 353–354. [Google Scholar]

- Bjerregaard, A.A.; Petersen, M.W.; Skovbjerg, S.; Gormsen, L.K.; Cedeño-Laurent, J.G.; Jørgensen, T.; Linneberg, A.; Dantoft, T.M. Physiological Health and Physical Performance in Multiple Chemical Sensitivity—Described in the General Population. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 9039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark, I. When Avoiding Chemicals Means Avoiding Others: Relational Exposures and Multiple Chemical Sensitivity. Soc. Sci. 2024, 13, 528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skovbjerg, S.; Hauge, C.R.; Rasmussen, A.; Winkel, P.; Elberling, J. Mindfulness-Based Cognitive Therapy to Treat Multiple Chemical Sensitivities: A Randomized Pilot Trial. Scand. J. Psychol. 2012, 53, 233–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fjorback LO, Arendt M, Ørnbøl E, Fink P, Walach H. Mindfulness-based stress reduction and mindfulness-based cognitive therapy: a systematic review of randomized controlled trials. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2011, 124, 102–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D'Souza, J. Patient Expert Perspectives on Multiple Chemical Sensitivities and the Validity of Access Needs. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. Pract. 2024, 12, 267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 Statement: An Updated Guideline for Reporting Systematic Reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maher, C.G.; Sherrington, C.; Herbert, R.D.; Moseley, A.M.; Elkins, M. Reliability of the PEDro scale for rating quality of randomized controlled trials. Phys. Ther. 2003, 83, 713–721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute. National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute. Quality Assessment Tool for Case Series Studies; National Institutes of Health: Bethesda, MD, USA. Quality Assessment Tool for Case Series Studies; National Institutes of Health: Bethesda, MD. Available online: https://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/health-topics/study-quality-assessment-tools (accessed on April 6, 2025).

- Centre for Evidence-Based Management (CEBMa). Critical Appraisal of a Case Study. Case Study Evaluation Tool. Available online: https://www.cebma.org (accessed on April 6, 2025).

- Higgins, J.P.T.; Altman, D.G.; Gotzsche, P.C.; Juni, P.; Moher, D.; Oxman, A.D.; et al. The Cochrane Collaboration’s tool for assessing risk of bias in randomised trials. BMJ 2011, 343, d5928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guyatt, G.H.; Oxman, A.D.; Vist, G.E.; Kunz, R.; Falck-Ytter, Y.; Alonso-Coello, P.; Schünemann, H.J. GRADE: An Emerging Consensus on Rating Quality of Evidence and Strength of Recommendations. BMJ 2008, 336, 924–926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woolfolk, R.L. Cognitive-Behavioural Exposure Therapy for Multiple Chemical Sensitivity: A Case Study. Psychol. Psychother. Res. Stud. 2018, 1, 000507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amin, J.; Forslund, S. Cognitive Behavior Therapy for Multiple Chemical Sensitivity: A Single Case Experimental Design [Dissertation]. Örebro University, 2019. Available online: https://urn.kb.se/resolve?urn=urn:nbn:se:oru:diva-73356 (accessed on April 6, 2025).

- Tran, M.T.D.; Skovbjerg, S.; Arendt-Nielsen, L.; Christensen, K.B.; Elberling, J. A Randomised, Placebo-Controlled Trial of Transcranial Pulsed Electromagnetic Fields in Patients with Multiple Chemical Sensitivity. Acta Neuropsychiatr. 2017, 29, 267–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hauge, C.R.; Bonde, P.J.E.; Rasmussen, A.; Skovbjerg, S. Mindfulness-Based Cognitive Therapy for Multiple Chemical Sensitivity: A Study Protocol for a Randomized Controlled Trial. Trials 2012, 13, 179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skovbjerg, S.; Hauge, C.R.; Rasmussen, A.; Winkel, P.; Elberling, J. Mindfulness-Based Cognitive Therapy to Treat Multiple Chemical Sensitivities: A Randomized Pilot Trial. Scand. J. Psychol. 2012, 53, 233–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Araki, A.; Watanabe, K.; Eitaki, Y.; Kawai, T.; Kishi, R. The Feasibility of Aromatherapy Massage to Reduce Symptoms of Idiopathic Environmental Intolerance: A Pilot Study. Complement. Ther. Med. 2012, 20, 400–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elberling, J.; Gulmann, N.; Rasmussen, A. Electroconvulsive Therapy Substantially Reduces Symptom Severity and Social Disability Associated with Multiple Chemical Sensitivity: A Case Report. J. ECT 2010, 26, 231–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sampalli, T. A Controlled Study of the Effect of a Mindfulness-Based Stress Reduction Technique in Women with Multiple Chemical Sensitivity, Chronic Fatigue Syndrome, and Fibromyalgia. J. Multidiscip. Healthc. 2009, 53, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Busse, J.; Reid, S.; Leznoff, A.; Barsky, A.; Qureshi, R.; Guyatt, G. Managing Environmental Sensitivity: An Overview Illustrated with a Case Report. J. Can. Chiropr. Assoc. 2008, 52, 88–95. [Google Scholar]

- Stenn, P.; Binkley, K. Successful Outcome in a Patient with Chemical Sensitivity: Treatment with Psychological Desensitization and Selective Serotonin Reuptake Inhibitor. Psychosomatics 1998, 39, 547–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guglielmi, S.R.; Cox, D.J.; Spyker, D.A. Behavioral Treatment of Phobic Avoidance in Multiple Chemical Sensitivity. J. Behav. Ther. Exp. Psychiatry 1994, 25, 197–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Institut National de la Santé Et de la Recherche Médicale (INSERM). Study of Cognitive and Behavioural Biases in People With Idiopathic Environmental Intolerance (IEI) Versus Healthy Controls (BELIEFS VS). ClinicalTrials.gov. 2025. Available online: https://clinicaltrials.gov/study/NCT06800976 (accessed on 6 April 2025).

- Fonzo GA, Ramsawh HJ, Flagan TM, Sullivan SG, Simmons AN, Paulus MP, Stein MB. Cognitive-behavioral therapy for generalized anxiety disorder is associated with attenuation of limbic activation to threat-related facial emotions. J Affect Disord. 2014, 169, 76–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karanassios G, Schultchen D, Möhrle M, Berberich G, Pollatos O. The effects of a standardized cognitive-behavioural therapy and an additional mindfulness-based training on interoceptive abilities in a depressed cohort. Brain Sci. 2021, 11, 1355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hillert L, Musabasic V, Berglund H, Ciumas C, Savic I. Odor processing in multiple chemical sensitivity. Hum Brain Mapp. 2007, 28, 172–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Del Casale, A.; Ferracuti, S.; Mosca, A.; Pomes, L.M.; Fiaschè, F.; Bonanni, L.; Borro, M.; Gentile, G.; Martelletti, P.; Simmaco, M. Multiple Chemical Sensitivity Syndrome: A Principal Component Analysis of Symptoms. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 6551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andersson L, Claeson A-S, Ledin L, Wisting F, Nordin S. Reduced olfactory performance and 5-HT₁A receptor binding potential in multiple chemical sensitivity. Hum Psychopharmacol Clin Exp. 2014, 29, 548–557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azuma K, Uchiyama I, Tanigawa M, et al. Chemical intolerance: involvement of brain function and networks after exposure to extrinsic stimuli perceived as hazardous. Environ Health Prev Med, 24. [CrossRef]

- Lim JA, Choi SH, Lee WJ, Jang JH, Moon JY, Kim YC, Kang DH. Cognitive-behavioral therapy for patients with chronic pain: implications of gender differences in empathy. Medicine (Baltimore), 2018; 97, e10867. [CrossRef]

- Simons LE, Harrison LE, Boothroyd DB, Parvathinathan G, Van Orden AR, O'Brien SF, Schofield D, Kraindler J, Shrestha R, Vlaeyen JWS, Wicksell RK. A randomized controlled trial of graded exposure treatment (GET living) for adolescents with chronic pain. Pain. 2024, 165, 177–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jensen KB, Kosek E, Wicksell R, Kemani M, Olsson G, Merle JV, Kadetoff D, Ingvar M. Cognitive Behavioral Therapy increases pain-evoked activation of the prefrontal cortex in patients with fibromyalgia. Pain. 2012, 153, 1495–1503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Draganov M, Galiano-Landeira J, Doruk Camsari D, Ramírez JE, Robles M, Chanes L. Noninvasive modulation of predictive coding in humans: causal evidence for frequency-specific temporal dynamics. Cereb, 2023; 3. [CrossRef]

- Yasoda-Mohan A, Vanneste S. Development, Insults and Predisposing Factors of the Brain's Predictive Coding System to Chronic Perceptual Disorders-A Life-Course Examination. Brain Sci. 2024, 14, 86. [CrossRef]

- Ceko M, Eippert F, Moayedi M, Bushnell MC, Schweinhardt P. Brain activity underlying pain-related attention and reappraisal in fibromyalgia. Neuroimage. 2024, 291, 120408. [Google Scholar]

- Keng SL, Smoski MJ, Robins CJ. Effects of mindfulness on psychological health: a review of empirical studies. Clin Psychol Rev. 2011, 31, 1041–1056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van den Bergh O, Witthöft M, Petersen S, Brown RJ. Symptoms and the body: Taking the inferential leap. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2017, 74, 185–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rathore M, Verma M, Nirwan M, Trivedi S, Pai V. Functional connectivity of prefrontal cortex in various meditation techniques: a mini-review. Int J Yoga, 15. [CrossRef]

- Craske, M.G.; Treanor, M.; Conway, C.C.; Zbozinek, T.; Vervliet, B. Maximizing Exposure Therapy: An Inhibitory Learning Approach. Behav. Res. Ther. 2014, 58, 10–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gatzounis, R.; den Hollander, M.; Meulders, A. Optimizing Long-Term Outcomes of Exposure for Chronic Primary Pain from the Lens of Learning Theory. J. Pain 2021, 22, 1315–1327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knowles, K.A.; Olatunji, B.O. Enhancing Inhibitory Learning: The Utility of Variability in Exposure. Cogn. Behav. Pract. 2019, 26, 186–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flatscher, J.; Pavez Loriè, E.; Mittermayr, R.; Meznik, P.; Slezak, P.; Redl, H.; Slezak, C. Pulsed Electromagnetic Fields (PEMF)—Physiological Response and Its Potential in Trauma Treatment. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 11239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, H.; Yang, W.; Zeng, Q.; Chen, W.; Zhu, Y.; Liu, W.; Wang, S.; Wang, B.; Shao, Z.; Zhang, Y. Promising Application of Pulsed Electromagnetic Fields (PEMFs) in Musculoskeletal Disorders. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2020, 131, 110767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tran, M.T.D.; Skovbjerg, S.; Arendt-Nielsen, L.; Bech, P.; Lunde, M.; Elberling, J. Two of Three Patients with Multiple Chemical Sensitivity Had Less Symptoms and Secondary Hyperalgesia after Transcranially Applied Pulsed Electromagnetic Fields. Scand. J. Pain 2014, 5, 104–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van Thriel, C.; Kiesswetter, E.; Schäper, M.; Juran, S.A.; Blaszkewicz, M.; Kleinbeck, S. Odor annoyance of environmental chemicals: Sensory and cognitive influences. J. Toxicol. Environ. Health A 2008, 71, 776–785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).