1. Introduction

China has long implemented a dual urban-rural land ownership system, with state ownership in urban areas and collective ownership in rural and suburban areas, under which collective land can only enter the market after being requisitioned and converted into state-owned land. In recent years, the requisition-based development model has been weakened due to policies like the Occupation⁃compensation Balance of Farmland, the Increase-decrease Linkage between Urban and Rural Construction Land , and the Narrowing the Scope of Land Requisition. Instead, the stock-based development model has become an alternative approach, with one key breakthrough being the legalization of collective-owned construction land (COCL) entry into the market. This reform aims to fill the gap in construction land quatos, improve the efficiency of rural land allocation, expand the scope of government’s land revenue, increase farmers’ income, and promote urban-rural integration(Wang et al., 2017;Zhou et al., 2020).

The marketization reform of COCL was officially launched in 15 pilot counties (cities/districts) in February 2015 and expanded to 33 regions in September 2016. Then, the pilot period of this reform was extended until the end of 2019. In January 2020, the revised “Land Management Law” was implemented, allowing rural collective land designated for industrial, commercial, and other business purposes to be used for enterprises or individuals on a paid basis through methods such as transfer, equity participation, leasing, and transfer. The goal of this reform is to establish an integrated urban-rural construction land market and achieve “equal rights and equal prices” for both types of land(Huang,2019). “Equal rights” refers to the legal unity of the use rights of collective and state-owned construction land, while “equal prices” refers to the same price formation mechanism for both(Jin,2017).

As this reform deepens and expands, studies on COCL has increased significantly, with one key issue being the impact of ownership on construction land prices. Scholars mostly believe that the factors influencing construction land prices can be categorized into five types. The first type is natural environment factors, including elevation, slope, and water bodies(Gao et al., 2014;Gao et al., 2020). The second type is geographic location factors, including distance to city centers, commercial hubs, schools, parks, and water sources(Fitzgerald et al., 2020;Yang et al., 2020). The third type is socio-economic condition factors, including population, GDP, fiscal revenue, and per capita income(Yuan et al., 2019; Lu and Wang, 2020). The fourth type is land parcel characteristic factors, including Land area, usage duration, land-use type, transaction method, transaction timing, and floor area ratio (Qin and Sun, 2010;Huang and Du, 2018). The fifth type is land policy factors, including land supply policies and spatial planning regulations (Tu et al., 2017;Tu et al., 2020). In addition to these factors, property rights is another crucial factor influencing construction land prices. Wu et al (2022) argued that the type and extent of land rights transferred by property owners lead to variations in realized land value. Huang and Du (2020) analyzed the impact of property rights on the transfer prices of construction land using micro-level land transaction data from Deqing County, finding a significant negative effect of collective ownership. Ye et al (2018) examined the impact of property rights on the utilization efficiency of construction land based on survey data from Wuxi City, revealing that collective ownership substantially lowers land prices.

However, previous studies rarely quantitatively verified the impact of ownership on construction land prices, and failed to consider the role of government decision-making. To further explain the mechanism of the formation of construction land price, it is necessary to address the following questions: How does ownership affect construction land prices? What role do government decision-making play in this process?

Based on the theoretical framework of property rights affecting the realization of land value, this paper analyzed the impact of ownership on construction land prices using the Spatial Durbin Model (SDM) based on micro-level land transaction data from Wujin District, Changzhou City from 2015 to 2021. Besides, this study introduced spatial planning and supply plan as moderating variables to comprehensively analyze their role in the relationship between ownership and construction land prices.

2. Theoretical Framework

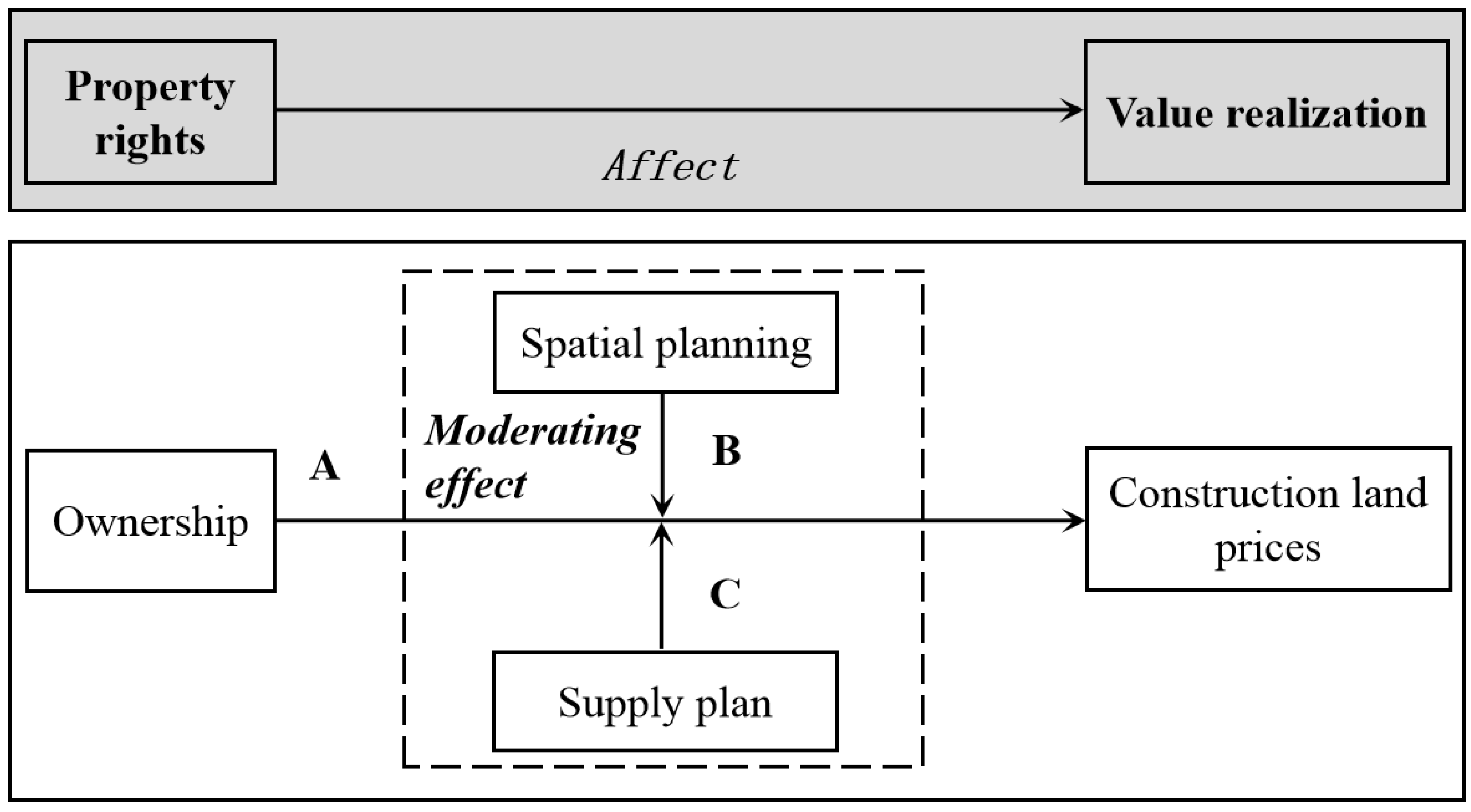

Property rights is the foundation for the realization of land value, and its completeness affects the extent to which land value is realized (Wu et al., 2022). Under national law, the use rights of collective and state-owned construction land are granted equal status and can enter the market on an equal footing. However, in actual economic activities, the use rights of COCL remain subject to greater restrictions compared to that of state-owned construction land, leading to more severe deficiencies in property rights and hindering the realization of their values. Following the fundamental logic that property rights systems influence the realization of land value, this paper quantitatively analyzed the impact of ownership on construction land prices under the context of the marketization reform. Building on this foundation, we introduced spatial planning and supply plan as variables to analyze the role of government decision-making in the relationship between ownership and construction land prices.The theoretical framework and hypotheses for this paper are illustrated in

Figure 1.

Ownership serves as the prerequisite for exercising the four rights of land: possession, use, disposition, and income generation (Long et al., 2022). The use rights of COCL is subject to administrative interventions from both the government and the collective, resulting in its insufficient exclusivity and stability, which inevitably constrains its market value. Under such circumstances, the usufructuary rights of collective-owned land are comparatively weaker than that of state-owned land. Therefore, this study proposes Hypothesis A: Compared to state ownership, collective ownership tends to lower construction land prices.

With the advancement of urbanization, the continuous expansion of urban space has resulted in gradual scarcity of construction land, thus compels the government to impose restrictions on urban development boundaries. The Urban Planning Compilation Measures (2006 Version) explicitly stipulates that urban growth boundaries must be delineated in downtown area planning to limit urban sprawl and define construction zones. This makes spatial planning a core component of urban planning (Cao, 2001). Land-use planning serves as the basis for land-use regulation and a tool to control land utilization behaviors, aiming to achieve rational allocation of land resources (Zheng,2004). The distinction between urban and rural areas, manifested in differences in planning and land-use regulation, is the root cause of the inequality in rights between collective and state-owned construction land (Wu,2020). As the architects of territorial spatial planning, local governments spatially constrain urban land development by demarcating downtown areas. Some studies revealed that COCL prices are significantly lower than that in state-owned land, with the price gap within downtown areas exceeding that in rural regions (Zhou et al., 2021). By extension, this price gap may be larger within downtown areas than areas outside. Thus, this paper proposes Hypothesis B: The boundaries of downtown areas defined by spatial planning exert a negative moderating effect on the impact of collective ownership on construction land prices, amplifying the downward pressure of collective ownership on land values.

As managers of the land market, local governments regulate the market through the formulation of land supply plan, which distorts the supply-demand dynamics and suppresses the premium potential. Under the policy guidance of Narrowing the Scope of Land Requisition, local governments tend to integrate both collective and state-owned construction land into their land supply plan. When total land supply increases, competition among land demanders becomes weaker, which leads to lower its prices (Huang and Du, 2018). Similarly, when the proportion of collective-owned land in the total construction land supply rises, competition among collective-owned land demanders becomes weaker, which further depresses its prices. Therefore, this study proposes Hypothesis C: The proportion of collective-owned land in the annual total land supply, as determined by land supply plan, exerts a negative moderating effect on the relationship between collective ownership and construction land prices, amplifying the negative impact of collective ownership on land values.

3. Data and Methodology

3.1. Study Area

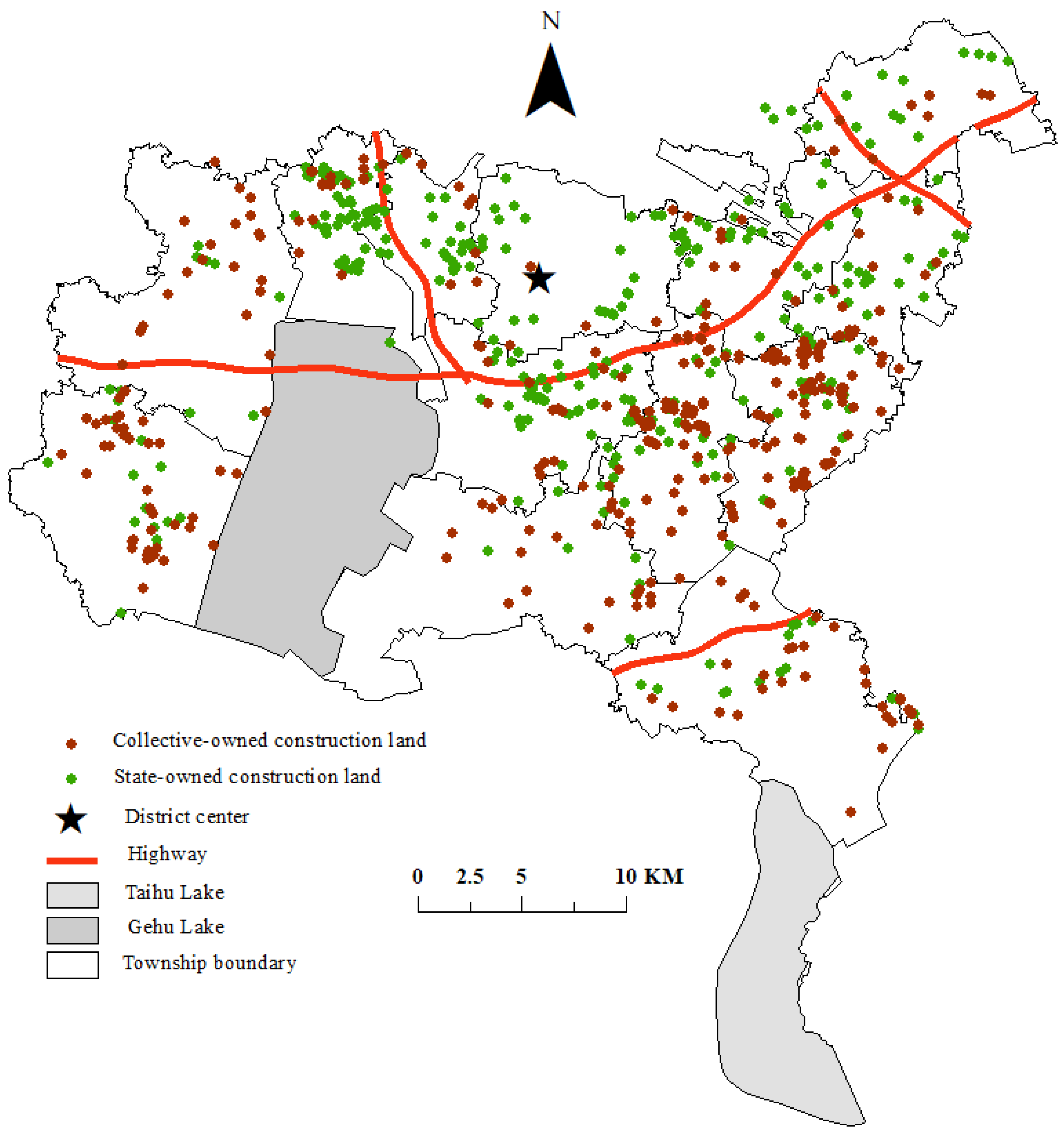

Wujin District, Changzhou City is located in the highly developed core area of the Yangtze River Delta, governs 11 towns and 5 sub-districts (

Figure 2). In 2019, the secondary and tertiary industries accounted for 98.4% of the total GDP in Wujin District, with the urbanization rate being 68.14% (CMBS, 2019). Meanwhile, the yearly per capita disposable income of rural residents in Wujin District was 32,400 yuan (CMBS, 2019). This shows that its industrialization, urbanization, and income levels are significantly higher than the national average. As one of the birthplaces of the “Southern Jiangsu Model” of economic development, Wujin District has a large number of collective and private-owned enterprises, leading to a significant potential demand for COCL. In September 2016, Wujin District was selected as one of the second batch of pilots for the marketization reform of COCL, implementing the same transaction platform for collective and state-owned construction land. With a longer implementation period and a relatively mature market, Wujin District is at the forefront of this reform and serves as an ideal area for this study.

3.2. Data Sources

This study used web scraping technology to collect data on collective and state-owned construction land transactions in Wujin District from 2017 to 2021 from the Jiangsu Land Market Network. The data included land location, total transfer price, area, usage period, use purpose, planning indicators, transaction mode and transaction time. The Geocoding tool was used to obtain the latitude and longitude coordinates corresponding to each land parcel’s location. From 2017 to 2021, there were 1,430 parcels of COCL transferred with a total area of 1104.8 ha in Wujin District, of which more than 90% were industrial and commercial land. This indicates that industrial and commercial land dominate the collective-owned land market in Wujin District. Since COCL can’t be used for commercial residence development, the intersection of use purposes between collective and state-owned land mainly lies in industrial and commercial uses. Therefore, this study excluded residential land from the sample data and used industrial and commercial land as representatives for the regression analysis of construction land prices.

Additionally, vector and raster data of administrative boundaries and centers, transport routes and stations, schools, parks, lakes, rivers, population density and GDP density were driven from the Data Center of Resources and Environment Science, built by the Institute of Geographic Sciences and Natural Resources Research at the Chinese Academy of Sciences (CAS, 2019). Data on the planning scope of downtown areas were obtained from the Changzhou City Urban Master Plan (2011-2020) (CMBNRP, 2019), and were spatially delineated using Google Earth.

3.3. Model Construction

To verify the hypotheses, this study employed a hedonic price model to analyze the impact of ownership on construction land prices, and used a Moderating effect model to analyze the role of spatial planning and supply plan in this relationship.

3.3.1. Hedonic Price Model

The hedonic price model is widely used for analyzing the influencing factors of land prices (Dong et al.,2011;Ploegmakers and de Vor,2015). It decomposes the research object into multiple component attributes and obtains the coefficients of each attribute through spatial regression models (Rosen, 1974;Chau and Chin, 2002). In this model, land is a comprehensive commodity affected by land parcel attributes, geographic locations, and socio-economic factors, and its prices are determined by these factors combined. The conceptual formula of the hedonic price model can be expressed as follows:

Where is the land price, is the land parcel attribute, is the geographic location, and is the neighborhood characteristic.

The Ordinary Least Squares (OLS) model is widely used for analyzing the influencing factors of land prices, but it ignores the spatial dependence between observations, leading to potential bias in the analysis results. The Spatial Durbin Model (SDM) considers the spatial dependence between observations and provides more accurate analysis results than the OLS model. The parameter results of these two models are the same for all spatial units, i.e., globally unified. Therefore, this study uses the SDM model to explain the influencing factors of land prices.

The SDM is a combined and extended form of Spatial Lag Model (SLM) and Spatial Error Model (SEM), constructed by imposing specific constraints on both models. It not only accounts for interaction effects between explained variables, but also incorporates interaction effects between explained and explanatory variables. Its econometric formulation is expressed as:

Here, the meanings of ,, α, , and are consistent with those in formula 2. and respectively represent the spatial contiguity weight matrices for the explained and explanatory variables, which are the same in this formula. denotes the spatial autocorrelation coefficients of the explanatory variables, with values ranging between -1 and 1, reflecting the influence relationship between the explanatory variables of neighboring spatial units and the explained variable of the focal unit. When =0, the model retains the spatially lagged explained variable while excluding the spatially lagged explanatory variables, thereby reducing to SLM. When =0, , the model incorporates the spatially lagged explanatory variables but removes the spatially lagged explained variable, evolving into SLM for explanatory variables . When both =0 and =0, the spatial lag effects of both the explained and explanatory variables are disregarded, and the model simplifies to OLS model. If a spatially lagged random error term is further introduced, the model transforms into SEM.

3.3.2. Moderating Effect Model

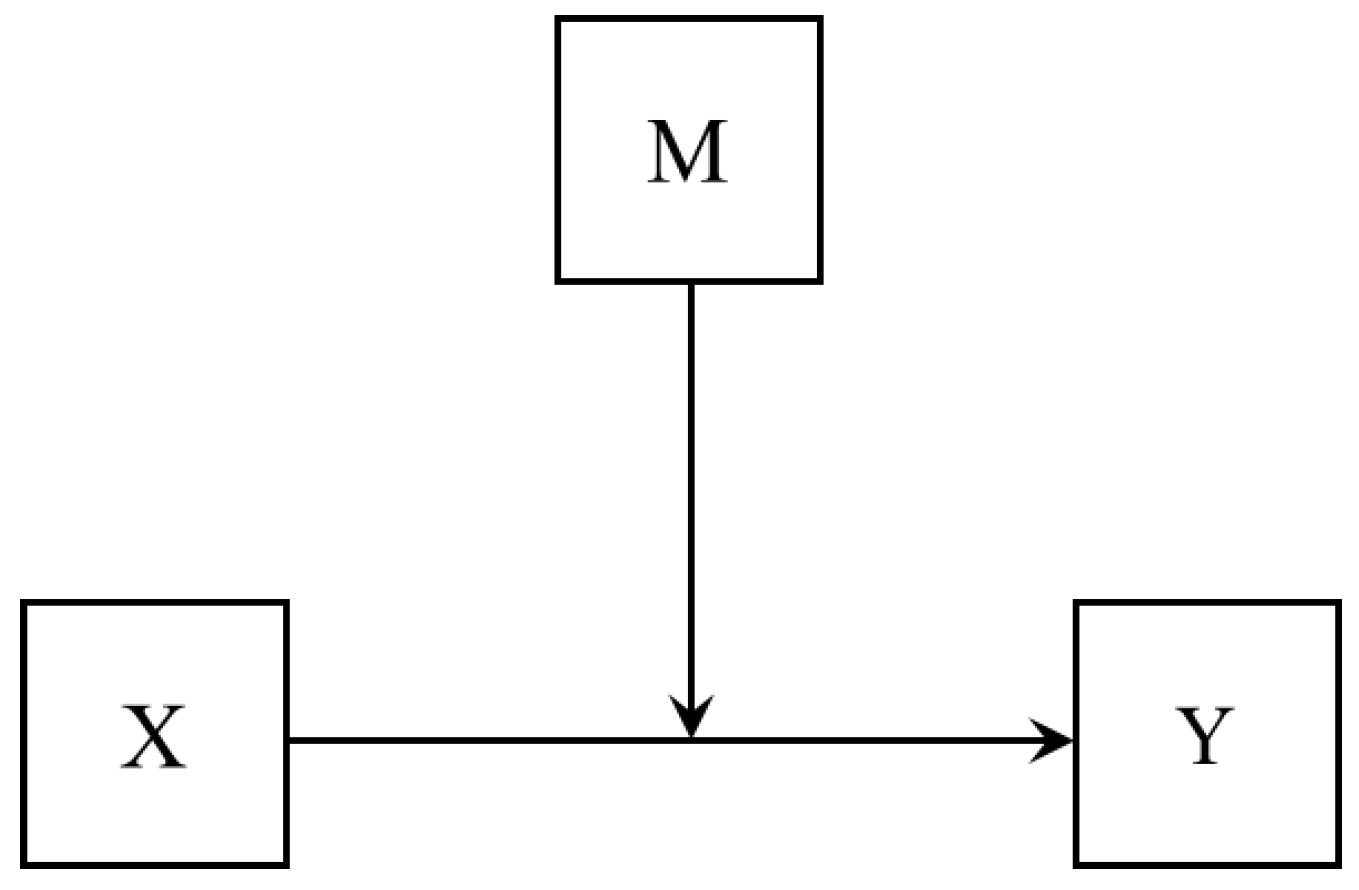

The Moderating Effect Model is a commonly used method in social science research, and an important tool for exploring the relationships between multiple variables. As shown in

Figure 3, if the relationship between the explanatory variable

and the explained variable

is influenced by a third variable

, it is considered that

has a moderating effect on the relationship between

and

, and

is referred to as the moderator variable (Wen et al., 2005). The moderator variable affects the direction and strength of the relationship between the explanatory and explained variables, meaning that the sign and magnitude of the regression slope between the explanatory and explained variables will change under different values of the moderator variable (Baron and Kenny, 1996). By constructing interaction terms between the explanatory and moderator variable, the moderating effect of the moderator variable can be evaluated. The Moderating effect model can be finally established as follows:

If the regression coefficient of the interaction term XM is significant, it indicates that the moderating effect of variable M is significant, and the regression coefficient can measure the moderating effect of variable M.

There are four situations for the moderating effects:

- (1)

The main effect (the regression coefficient of the explanatory variable when the interaction term is not introduced) is positive, and the coefficient of the interaction term is positive, indicating that the moderator variable M has a positive moderating effect. This means that M strengthens the positive impact of X on Y, i.e., when M has a high value, it enhances the positive impact.

- (2)

The main effect is positive, and the coefficient of the interaction term is negative, indicating that the moderator variable M has a negative moderating effect. This means that M weakens the positive impact of X on Y, i.e., when M has a high value, it reduces the positive impact.

- (3)

The main effect is negative, and the coefficient of the interaction term is positive, indicating that the moderator variable M has a positive moderating effect. This means that M weakens the negative impact of X on Y, i.e., when M has a high value, it reduces the negative impact.

- (4)

The main effect is negative, and the coefficient of the interaction term is negative, indicating that the moderator variable M has a negative moderating effect. This means that M strengthens the negative impact of X on Y, i.e., when M has a high value, it enhances the negative impact.

This study introduces interaction terms between explanatory and moderator variables to analyze the moderating effect of the moderator variables on the relationship between explanatory and explained variables.

3.4. Variable Selection and Descriptive Statistics

3.4.1. Variable Selection

To analyze the impact of ownership on construction land prices and the role of government decision-making in the relationship, this study used SPSS 19.0 software to perform VIF tests on construction land prices and potential influencing factors. After eliminating factors with the VIF over 10 and collinearity, 1 core explanatory variable, 14 control variables, and 2 moderating variables were selected

(1) Explained variable

The explained variable of this study is land price (Y), which equals the total transfer price of divided by the total area. In addition, the Consumer Price Index (CPI) was used to adjust the land price to the same period in 2019 to eliminate the impact of inflation, thereby enhancing the comparability of land price data from different years.

(2) Core explanatory variable

Under the dual urban-rural land ownership system, collective and state-owned land have unequal legal status, and the property rights of collective land are more incomplete, hindering the realization of their value. This study selected ownership (E) as the core explanatory variable to analyze its impact on construction land prices. If the land is collective-owned, it is assigned a value of 1, indicating relatively incomplete property rights. If the land is state-owned, it is assigned a value of 0, indicating relatively complete property rights.

(3) Moderator variables

This study analyzed the moderating role of spatial planning and supply plan in the relationship between the ownership and construction land prices.

This study introduced spatial planning (E1) as a variable to analyze its moderating role in the impact of ownership on construction land prices. Spatial planning is the core content of urban planning and land-use planning(曹荣林,2022). Local governments develop land-use planning to delineate the planning scope of downtown areas, which constrains urban land development behaviors. Within the planning scope of downtown areas, local governments tend to prioritize land requisition and large-scale development, which imposes more restrictions on the entry and development of COCL. Driven by the pursuit of land appreciation and risk-aversion, enterprises incline to avoid investing in COCL with poorer investment attributes and higher potential risks, which may have different impacts on the expected returns of COCL inside and outside the planning scope of downtown areas. Therefore, this study selected the planning scope of downtown areas as the measurement of local government’s spatial planning policies. If the land parcel is located within the planning scope of downtown areas, it is assigned a value of 1. If the land parcel is located outside the scope, it is assigned a value of 0.

Besides, this study introduced supply plan (E2) as a variable to verify its moderating role in the impact of ownership on construction land prices. Land supply plan is an important tool for local governments to regulate the land market. Increasing the supply of land typically leads to lower land prices(屠帆等,2017;Huang and Du, 2018). Local governments regulate the land market through the formulation of supply plan that takes consideration of both state and collective-owned construction land, which distorts the supply and demand relationship in the land market and may affect the expected returns of COCL supplied through market-driven and non- market-driven ways. Therefore, this study selected the proportion of COCL in the total annual land supply as a measurement of supply plan made by local governments.

(4) Control variables

The control factors influencing land prices can be categorized into three types: parcel attributes, location attributes, and neighborhood attributes. Land parcel attributes include area (X1), term (X2), and time (X3). Location attributes include the distance to district center (X4), the distance to township or sub-district center (X5), the distance to highway exit (X6), the distance to major road (X7), the distance to train station (X8), the distance to park (X9), the distance to school (X10), the number of schools (X11), and the distance to water source (X12). Neighborhood attributes include population density (X13) and GDP density (X14).

3.4.2. Descriptive Statistics of Main Variables

Compared to state-owned construction land, COCL exhibits significantly lower prices, smaller plots, longer distances to the district center and roads at various levels, and notably lower population density and GDP density (

Table 2). These findings indicate that COCL has lower use value, poorer locations, and weaker potential demand compared to state-owned construction land.

4. Analysis Results

4.1. Impact of Ownership on Construction Land Prices

This study used SDM to analyze the impact of ownership on construction land prices. The main effect (Main) results of SDM shows that the regression coefficient of ownership (

E) is negative at the 1% significance level (

Table 3), indicating that collective ownership lowers construction land prices, which supports Hypothesis A. This is because COCL is subject to administrative interventions from both the government and the collective, resulting in weaker exclusivity and stability compared to state-owned construction land, thereby limiting its market prices. Besides, construction land prices are also influenced by plot attributes and location attributes. From the perspective of plot attributes, area (

X1) has a positive impact on construction land prices at the 1% significance level, while term (

X2) has a negative impact at the 1% significance level. This indicates that bigger plots are conducive to the formation of larger-scale industrial clusters, which is beneficial for land appreciation. The investment intensity of commercial land is usually higher than that of industrial land, but the corresponding use term is generally shorter, presenting the phenomenon of longer use term corresponding to lower land prices. From the perspective of location attributes, the distances to main roads (

X7) and schools (

X9) both have negative impacts on construction land prices at the 1% significance level. This indicates that advanced mobility systems and convenient educational facilities can attract more enterprises to buy land, driving up its prices.

The spatial effect (Wx) results of SDM (

Table 3) show that the spatial effect regression coefficient of construction land prices (

Y) is at the 1% significance level, indicating that it has a significant positive spatial spillover effect. This demonstrates that spatially adjacent land parcels, when classified into comparable land grades through zoning practices, tend to develop approximating prices through the market, leading to positive mutual impact between adjacent parcels. In addition, the spatial effect regression coefficient of ownership (

E) is positive at the 1% significance level, with the opposite sign to the main effect regression coefficient, indicating that the spatial effect of ownership on construction land prices is opposite to the main effect. This means that the entry of adjacent COCL into the market has a positive impact on local land prices. This can be attributed to the agglomeration economies generated through the development of adjacent COCL, which stimulates coordinated infrastructure investment and economic densification in the region, consequently creating a positive externality effect on local land market.

Notes: ***, **, and * indicate statistical significance at the 1%, 5%, and 10% levels, respectively; the same notation applies throughout subsequent analyses.

4.2. Moderating Effect of Spatial Planning on the Impact of Ownership on Construction Land Prices

This study further introduced spatial planning and used SDM to analyze its

moderating role in the relationship between ownership and construction land prices. The main effect (Main) results of SDM show that the regression coefficient of the interaction term between ownership and spatial planning (

E*M1) is negative at the 1% significance level (

Table 4). This indicates that the planning scope of downtown areas, determined by spatial planning, enhances the negative impact of collective ownership on construction land prices, which supports Hypothesis B. In other words, compared to areas outside the downtown areas, the price gap between state and collective-owned construction land is larger within. Because local governments tend to prioritize land requisition and large-scale development within the downtown areas , while imposing more restrictions on the development of COCL. Driven by the pursuit of land appreciation and risk-aversion, enterprises tend to avoid investing in COCL with poor investment attributes and weaker exclusivity, which widens the price gap between state collective-owned construction land.

The spatial effect (Wx) results of SDM (

Table 4) show that the regression coefficient of the interaction term between ownership and spatial planning

(E1*M1) is positive at the 10% significance level, with the opposite sign to the main effect regression coefficient, indicating that the moderating effect of spatial planning presents a positive spatial spillover effect. This means that the positive radiation effect of the development of adjacent COCL on local land prices within the downtown areas is stronger than that outside. This may be because downtown areas have better infrastructure and higher land appreciation space, providing greater promotion to nearby land prices.

4.3. Moderating Effect of Supply Plan on the Impact of Ownership on Construction Land Prices

This study further introduced supply plan

and used SDM to analyze its moderating role in the relationship between ownership and construction land prices. When considering spatial correlation, the main effect (Main) results of SDM (Table 5) show that the regression coefficient of the interaction term between ownership and supply plan (E*M

2) is negative at the 1% significance level. This indicates that the proportion of COCL in the annual land supply, determined by land supply plan, weakening the negative impact of collective ownership on construction land prices, which supports Hypothesis C. In other words, an increase in the proportion of COCL in the annual land supply further widens the price gap between state and collective-owned construction land. This may be because COCL has weaker competitiveness due to more incomplete property rights and worse location conditions. When the proportion of COCL in the annual land supply increases, the situation of oversupply will escalate, leading to further downward pressure on land prices.

The spatial effect (Wx) results of SDM (

Table 5) show that the regression coefficient of the interaction term between ownership and supply plan

(E*M2) is no longer significant, indicating that the moderating effect of supply plan does not have a spatial spillover effect. This means that the impact of ownership on construction land prices is limited to the local parcel and does not affect the prices of adjacent parcels, regardless of changes in land supply plan.

5. Discussion and Conclusion

Under China’s dual urban-rural land ownership system, the unequal legal status of collective and state-owned land hinders the realization of “equal rights and equal prices” for both. Based on the theoretical framework of property rights affecting the realization of land value, this study analyzed the impact of ownership on construction land prices in China using micro-level land transaction data from Wujin District, Changzhou City from 2015 to 2021, employing SDM. Then, this study introduced spatial planning and supply plan as moderating variables to comprehensively analyze their role in the relationship between ownership and construction land prices. The research results show that collective ownership has a negative impact on land prices, and the development of adjacent COCL has a positive impact on land prices. Besides, the planning scope of downtown areas determined by spatial planning enhances the negative impact of collective ownership on land prices, thus widening the price gap between state and collective-owned land within the downtown areas. Furthermore, the proportion of COCL in the annual land supply determined by land supply plan strengthens the negative impact of collective ownership on land prices, meaning that a increase in COCL supply leads to further downward pressure on land prices. The findings not only confirm the negative impact of collective ownership on land prices (Ye et al., 2018; Wen et al., 2024), but also discover the moderating role of spatial planning and supply plan in this relationship.

The findings can provide policy implications for promoting “equal rights and equal prices” for urban and rural construction land in China. The first policy suggestion is that equivalent development control indicators should be established for collective and state-owned land within the same zoning district and for the same intended use. The second policy suggestion is that the supply of COCL should be coordinated based on market demand and policy momentum to achieve rational price regulations. The third policy suggestion is that the restrictions imposed by territorial spatial planning on COCL development within the downtown areas should be relaxed to grant collective and state-owned land with “equal rights” in approval processes. The findings can also provide policy implications for optimizing land pricing system in other countries with a dual land ownership system.

Acknowledgments

This research was funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant 42301219).

References

- Baron, R.M.; Kenny, D.A. The moderator-mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: Conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 1986, 51(6), 1173-1182.

- Cao, R.L. Views on the coordination between urban planning and land use planning. Economic Geography, 2001, 5, 605-608 (in Chinese).

- CAS (Chinese Academy of Sciences). Institute of Geographic Sciences and Natural Resources Research, 2019. EB/OL. http://www.resdc.cn/, (accessed 2024.12.22).

- Chau, K.W.; Chin, T.L. A critical review of literature on the hedonic price model. International Journal for Housing Science and Its Applications, 2002; 27(2), 145-165.

- CMBNRP (Changzhou Municipal Bureau of Natural Resources and Planning). Changzhou City Urban Master Plan (2011-2020), 2019. http://zrzy.jiangsu.gov.cn/, (accessed 2024.12.22).

- CMBS (Changzhou Municipal Bureau of Statistics). Changzhou Statistical Yearbook. China Statistics Press (in Chinese), 2019. https://tjj.changzhou.gov.cn/, (accessed 2024.12.22).

- Dong, G.P.; Zhang, W.Z.; Wu, W.J.; Guo, T.Y. Spatial heterogeneity in determinants of residential land price: Simulation and prediction. Acta Geographica Sinica, 2011, 66(6), 750-760 (in Chinese).

- Fitzgerald, M.; Hansen, D.J.; Mcintosh, W.; Slade, B.A. Urban land: Price indices, performance, and leading indicators. The Journal of Real Estate Finance and Economics, 2020, 60(3), 396-419.

- Gao, B.Y.; Luo, H.L.; Huang, Z.J.; Xu, F.Y.; Liu, B.H. Research on the spatial layout of and factors affecting the price of industrial land in China. Journal of Geoinformation Science, 2020, 22(6), 1189-1201 (in Chinese).

- Gao, J.L.; Chen, J.L.; Su, X. Influencing factors of land price in Nanjing Proper during 2001-2010. Progress in Geography, 2014, 33(2), 211-221 (in Chinese).

- Huang, X.J. Establishment of the integrated urban-rural construction land market system. China Land Science, 2019, 33(8), 1-7 (in Chinese).

- Huang, Z.H.; Du, X.J. Holding the market under the stimulus plan: Local government financing vehicle’s land purchasing behavior in China. China Economic Review, 2018, 50, 85-100. [CrossRef]

- Huang, Z.H.; Du, X.J. Does the marketization of collective-owned construction land affect the integrated urban-rural construction land market? An empirical research based on micro-level land transaction data in Deqing County, Zhejiang Province. China Land Sciences, 2020, 4(2), 18-26 (in Chinese).

- Jin, X.M. The scientific connotation and realization of “equal rights and equal prices” between collective and state-owned land. Issues in Agricultural Economy, 2017, 38(9), 12-18 (in Chinese).

- Long, D.G.; Chen, Y.Y.; Li, Y.W. Between the ownership and the right to use: The possession of land and its realization. China Economic Quarterly, 2022, 22(6), 2107-2124 (in Chinese).

- Lu, S.; Wang, H. Local economic structure, regional competition, and the formation of industrial land price in China: Combining evidence from process tracing with quantitative results. Land Use Policy, 2020, 97, 104704. [CrossRef]

- Ploegmakers, H.; de Vor, F. Determinants of industrial land prices in The Netherlands: A behavioural approach. Journal of European Real Estate Research, 2015, 8(3), 305-326.

- Qin, B.; Sun, L. The impacts of floor area ratio and transfer modes on land prices: Based on hedonic price model. China Land Sciences, 2010, 24(3), 70-74 (in Chinese).

- Rosen, S. Hedonic prices and implicit markets: Product differentiation in pure competition. Journal of Political Economy, 1974, 82(1), 34-55. [CrossRef]

- Tu, F.; Ge, J.W.; Liu, D.X.; Zhong, Q. Determinants of industrial land price in the process of land marketization reform in China. China Land Sciences, 2017, 31(12), 33-41 (in Chinese).

- Tu, F.; Zou, S.L.; Ding, R. How do land use regulations influence industrial land prices? Evidence from China. International Journal of Strategic Property Management, 2020, 25(1), 76-89. [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Zhang, X.L.; Wang, H.Z.; Skitmore, M. The right-of-use transfer mechanism of collective construction land in new urban districts in China: The case of Zhoushan City. Habitat International, 2017, 61, 55-63.

- Wen, L.J.; Yang, S.J.; Qi, M.N.; Zhang, A.L. How does China’s rural collective commercialized land market run? New evidence from 26 pilot areas, China. Land Use Policy, 2024, 136, 106969. [CrossRef]

- Wen, Z.L.; Hou, J.T.; Zhang, L. A comparison of moderator and mediator and their applications. Acta Psychologica Sinica, 2005, 2, 268-274 (in Chinese).

- Wu, Y.L. Difficult position and theoretical error of collective business construction land market with the dimension of “same rights for same land”. Academic Monthly, 2020, 52(4), 118-128 (in Chinese).

- Wu, Y.L.; Yu, Y.Y.; Hong, J.G. Property rights transfer, value realization and revenue sharing of rural residential land withdrawal: An analysis based on field surveys in Jinzhai and Yujiang. Chinese Rural Economy, 2022, 4, 42-63 (in Chinese).

- Yang, Z.H.; Li, C.X.; Fang, Y.H. Driving factors of the industrial land based on a geographically weighted regression model: Evidence from a rural land system reform pilot in China. Land, 2020, 9(1), 7. [CrossRef]

- Ye, L.F.; Huang, X.J.; Yang, H.; Chen, Z.G.; Zhong, T.Y.; Xie, Z.L. Effects of dual land ownerships and different land lease terms on industrial land use efficiency in Wuxi City, East China. Habitat International, 2018, 78, 21-28. [CrossRef]

- Yuan, F.; Wei, Y.D.; Xiao, W. Land marketization, fiscal decentralization, and the dynamics of urban land prices in transitional China. Land Use Policy, 2019, 89, 104208. [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Z.Y. Reform of comprehensive land use planning. China Land Sciences, 2004, 4, 13-18 (in Chinese).

- Zhou, X.P.; Feng, Y.Q.; Yu, S.Q. On optimization of land income distribution in transaction of rural commercial collective-owned construction land: A case study of the reform pilot in Beiliu City. Journal of Nanjing Agricultural University (Social Sciences Edition), 2021, 21(2), 116-125 (in Chinese).

- Zhou, Y.; Li, X.H.; Liu, Y.S. Rural land system reforms in China: History, issues, measures and prospects. Land Use Policy, 2020, 91, 104330. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).