Introduction

Advanced heart failure (AdvHF) therapies have continued evolving, but heart transplantation remains the gold standard of surgical care for AdvHF in the current era [

1]. Durable mechanical circulatory support (DMCS) devices have become new-generation choices that improve patients’ survival and quality of life from AdvHF but have been hindered by adverse event profiles. Since the first introduction of DMCS support, significant advances have been achieved in ventricular assist device (VAD) technology, including smaller and more reliable intrapericardial pump designs, improved hemocompatibility, and patient outcomes; however, transcutaneous driveline (DL) continues to remain a potential port for infection, challenging to treat and also limits patients’ freedom [

2,

3,

4].

DMCS-specific infections are the leading cause of morbidity and mortality [

3,

5,

6,

7]. Most VAD-specific infections occur around the driveline exit site (DLES), an entry point for pathogens, and are caused by skin colonization, stress, or trauma. Driveline infections (DLIs) may sometimes spread deeper than subcutaneous fascia, as defined by the International Society for Heart and Lung Transplantation (ISHLT) guidelines [

8]. They may progress to DL tunnel, pocket, or pump infections. ISHLT proposed consensus on DLI categorization as superficial and deep infections [

8]. Data obtained from the Interagency Registry for Mechanically Assisted Circulatory Support (INTERMACS) Registry; Goldstein

et al. reported a DLI rate of 19% within the first 12 months after VAD implantation [

9]. Recently, Simpson

et al. [

10] reported cumulative incidence of deep device infection as 11% (7%-18%) at 5 years.

Previous reports suggest that the risk of DLIs is increased with diabetes, obesity, malnutrition, renal dysfunction, younger age, DLES trauma, higher heart failure score, prolonged intensive care unit stay, history of depression, no partnership, T-cell dysfunction, hypogammaglobulinemia, presence of intravascular lines, surgical tunneling techniques and exposed velour at the DL [

4,

7,

11,

12,

13,

14].

Implementation of standardized DLES care protocols, including proper DL positioning and tunneling strategies, DLES immobilization using a binder or anchoring device, improved patient and caregiver education, improved personal hygiene and adequate nutrition are essential for preventing DLIs [

3,

4,

15,

16,

17,

18]. Treatment strategies for DLIs include targeted hospital antimicrobial therapy in combination with surgical resection of DLES, outpatient parenteral antimicrobial therapy, surgical debridement combined with removal of the biofilm or velour, local installation of absorbable antibiotic beads, vacuum-assisted strategies and delayed closure, closed catheter irrigation, DL relocation with omentoplasty, muscle flaps, DL relocation to available muscles, and device exchange [

3,

4,

5,

7,

10,

17,

19,

20,

21]. Antibiotics may be administered either as short-term treatment or as lifelong chronic suppressive therapy within the framework of destination therapy. Nevertheless, standardized treatment algorithms for DLIs are limited and generally based on expert consensus and clinical experience of the high-volume centers [

7,

19]. Currently, the gold standard therapeutic solution for deep DLI in VAD patients is heart transplantation, but the limited donor pool does not allow this option as a viable option, at least in our region. This study aimed to define the risk factors for DLIs and microbiologic profiles and discuss surgical treatment approaches and outcomes.

Materials and Methods

Setting

This study was approved by the Institutional Ethics Committee of Ankara University Faculty of Medicine (May 24, 2024 - No: 2024/286). Prior to the procedures, patients were provided with detailed information regarding the associated risks and potential therapeutic benefits. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants or their legal guardians. The study was conducted in adherence to the ethical standards set forth in the World Medical Association Declaration of Helsinki.

Study Population and Protocol

We retrospectively reviewed all patients who underwent continuous-flow VADs, either left ventricular assist device (LVAD) or biventricular assist device (BiVAD) implantation at a single center. A total of 90 patients received VAD for AdvHF either as a bridge to transplantation or as destination therapy between March 01, 2011, and May 30, 2023. Demographic and clinical information was extracted from an electronic patient health record system (Avicenna). Data were gathered about demographic information, comorbidities, VAD device type, time from VAD implantation to infection, microbiology results, number of surgical procedures, antibiotic therapy time, infectious symptoms, numbers of hospital readmissions, postoperative complications, reinfection rates, and overall survival. The baseline characteristics of the study cohort are listed in

Table 1.

Prophylactic Antibiotic Regimen and Driveline Protocol

Nasal decolonization with preoperative mupirocin ointment is applied intranasally to patients who are S. aureus carriers, regardless of the methicillin resistance. Standard perioperative antimicrobial prophylaxis includes cefazolin and in case of screening positive for methicillin-resistant S. aureus (MRSA) receive vancomycin for prophylaxis. Antimicrobial prophylaxis is continued for a maximum of 24-48 hours postoperatively.

Intraoperatively, we tunneled the DL in the sheath of the rectus muscle in the umbilical direction from the mediastinum and used a transfixing suture using 3/0 prolene at the level of the linea alba. Then, tunnel the DL again from the rectus muscle to subcutaneous tissue to the right upper quadrant. We routinely applied strict perioperative glycemic control, avoidance of transfusion of blood products if possible, and DLES immobilization using anchoring sutures and appropriate dressings. We avoided exposing polyester velour at the exit site, and the silicone portion of the DL always interfaced with the exit site. Due to unavailability, we could not use any anchoring device in this cohort.

Standard Driveline Dressing Protocol

Our patients are evaluated weekly for one month, then monthly for 1 to 3 months, then at the sixth month, and every year afterward at the follow-up period. Patients are advised to perform daily DL dressing changes, adhering to strict aseptic techniques, including proper hand hygiene, mask usage, and glove application. The DLES should be cleansed using a chlorhexidine-based solution and subsequently covered with a sterile dressing to minimize infection risk. Silver-impregnated gauzes are used in the presence of localized skin reactions to chlorhexidine.

Case Definitions

The onset of an infectious episode is defined as the time of its initial documentation in the medical record, while its resolution is marked by the completion of treatment. Recurrent infections are characterized as either new infections occurring after the cessation of therapy or as the need for therapy escalation in patients receiving long-term suppressive antibiotic treatment. Clinical signs of DLIs are presented in

Table 2.

Imaging and Surgical Management

An initial evaluation of the extent of DLI was performed using ultrasonography in this cohort. Radiologists performed ultrasound-guided fluid aspiration around the DL for gram stain and cultures. We used a 2-week course of targeted antimicrobial therapy for superficial DLES infections. Computed or positron emission tomography imaging was used in patients with suspected deep DLIs. (

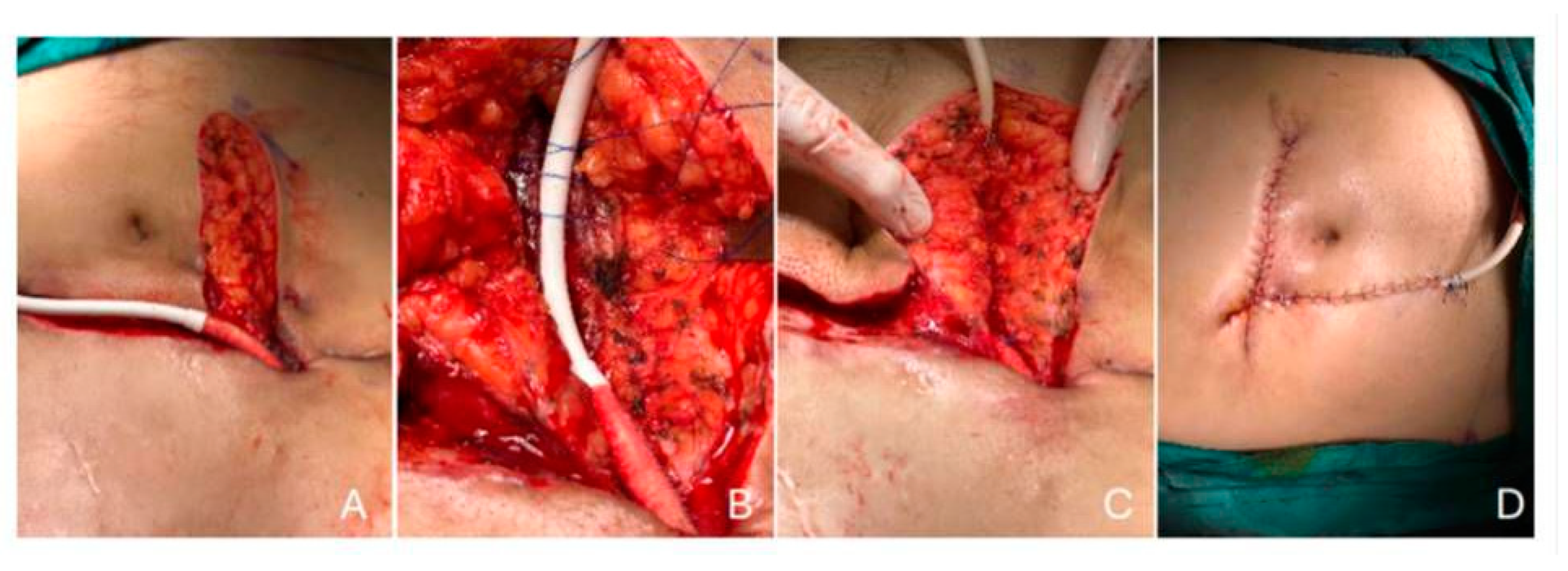

Figure 1). If imaging confers localized abscesses associated with the DL, we performed surgical drainage, exposed the DL, and applied vacuum-assisted closure. Once the DLI was resolved, we performed DL rectus muscle relocation.

Statistical Analysis

Statistical analyses were conducted using descriptive statistics, including mean, standard deviation, median, and minimum and maximum values. Group comparisons for categorical variables were performed using the chi-square test or Fisher’s exact test, while continuous variables were analyzed using the Student’s t-test. For non-normally distributed continuous or ordinal variables, the Mann–Whitney U test was employed. Kaplan–Meier survival analysis and the log-rank test were applied for univariate analysis, whereas multivariate analysis was conducted using Cox proportional hazards regression. Variables with a p-value < 0.25 in the univariate Cox regression, along with known independent risk factors for driveline infections, were included as candidates in the multivariate model. The final model incorporated variables with a p-value < 0.05, which was deemed statistically significant. Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves were utilized to evaluate the diagnostic performance of the methods. An area under the curve (AUC) of 0.50 indicates no discriminatory ability. Youden’s index was applied to identify the optimal cut-off values for the diagnostic methods. The AUC and corresponding 95% confidence intervals (CIs) for each variable were calculated and statistically compared. Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS version 29.0 (IBM SPSS Statistics, Chicago, IL, USA).

Results

During the study period, a total of 90 patients underwent VAD implantation, with 39 receiving HeartWare HVAD (Medtronic, MN), 38 receiving HeartMate 3 (HM3, Abbott, Inc.), 10 receiving HeartMate 2 (HM2, Abbott, Inc.), and three receiving HVAD or HM3 as BiVAD configuration.

In the follow-up of VAD patients, DLIs were detected in 20 (%21.5) patients. The mean age of all patients was 43.6 ± 17.7, and the mean age was 31.5 ± 15.9 in DLI’s group (p<0.05). In 15 (%75) patients, dilated cardiomyopathy is the etiology for AdvHF in the DLI group. However, 27 (% 38.7) of patients had dilated cardiomyopathy, 39 (57.14) patients had ischemic cardiomyopathy, and 3 (% 4.2) of patients had other reasons for their etiology of AdvHF in non-DLI groups (p<0.05). Only 2 (%10) of patients had hyperlipidemia in the DLI group, and 40 (%57.1) of patients had hyperlipidemia in the non-DLI group (p<0.05).

The mean plasma albumin level was detected at 28.8 ± 2.4 g/dl in the DLI group and 33.6 ± 5.3 in the non-DLI group (p<0.05). In the ROC analysis, the cut-off values were 52 years old for age and 30.4 g/dl for plasma albumin level. In the Cox proportional hazard model, younger age and plasma albumin levels were independent predictive factors for the risk of DLI with a hazard ratio of 9.77 (95% CI: 1.3 – 74.5) and 10.55 (95% CI: 1.40 – 79.35), respectively (

Table 3).

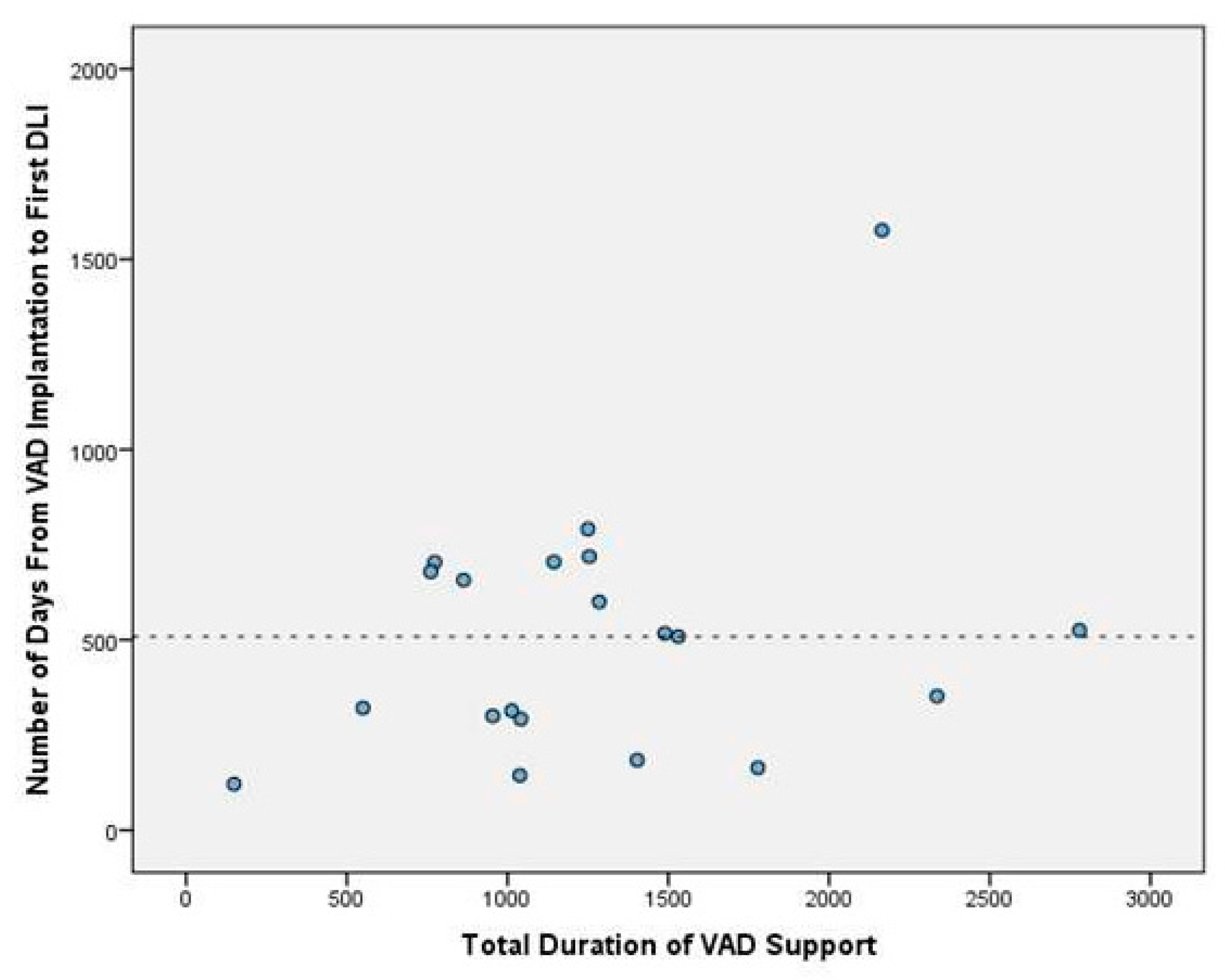

Our mean duration of VAD time was 561.1 ± 833.2 days in all patient groups. On the other hand, the mean duration of VAD time was 1277.9 ± 621.6 days in the DLIs group. This shows a statistically significant relation between the risk of DLI infection and the total duration of VAD time (p<0.05). The relation between the total duration of VAD time and DLIs is presented in

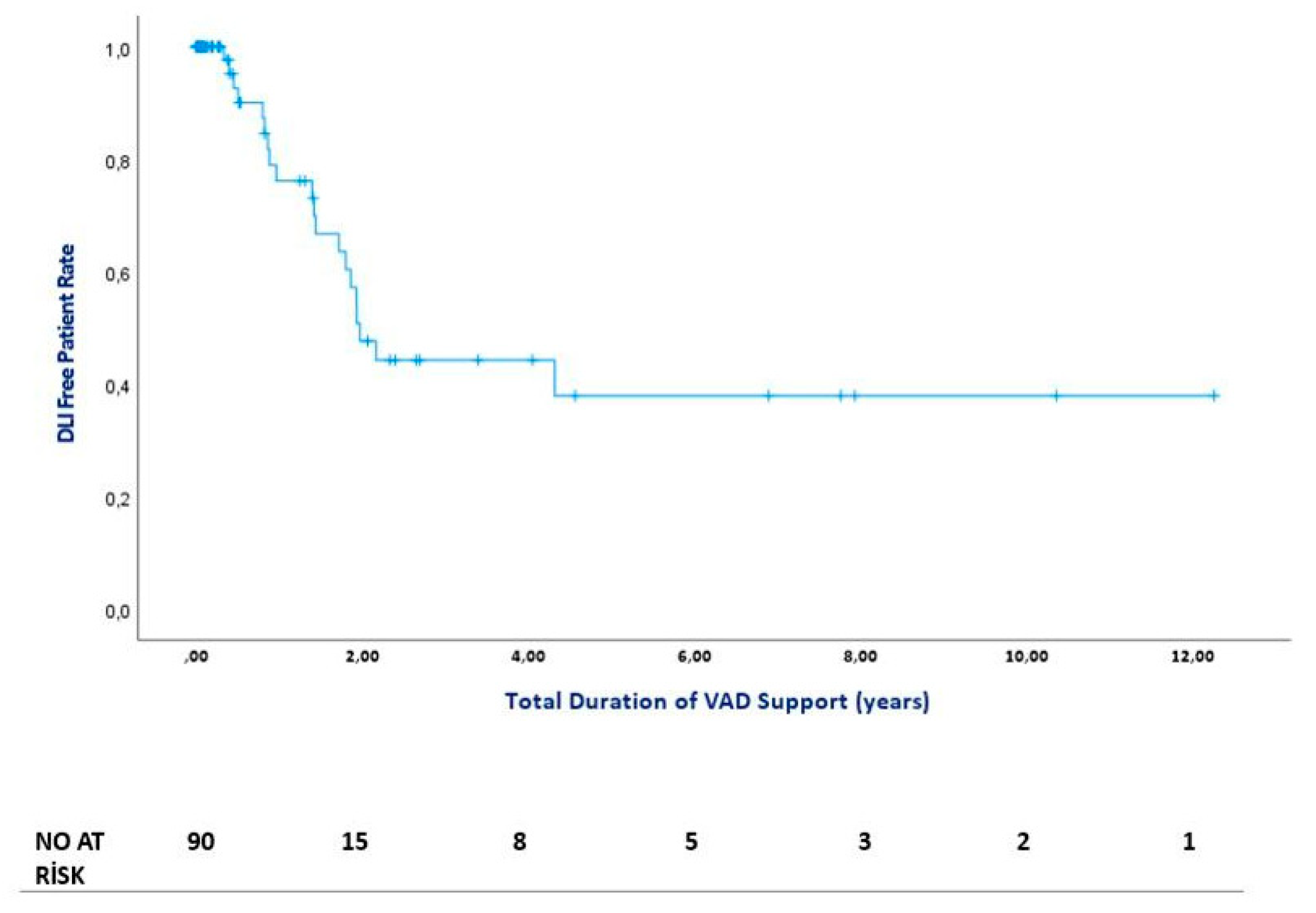

Figure 2. The median time from VAD implantation to first DLI admission was 513 days (IQR = 404). The figure of DLI-free days is presented in

Figure 3.

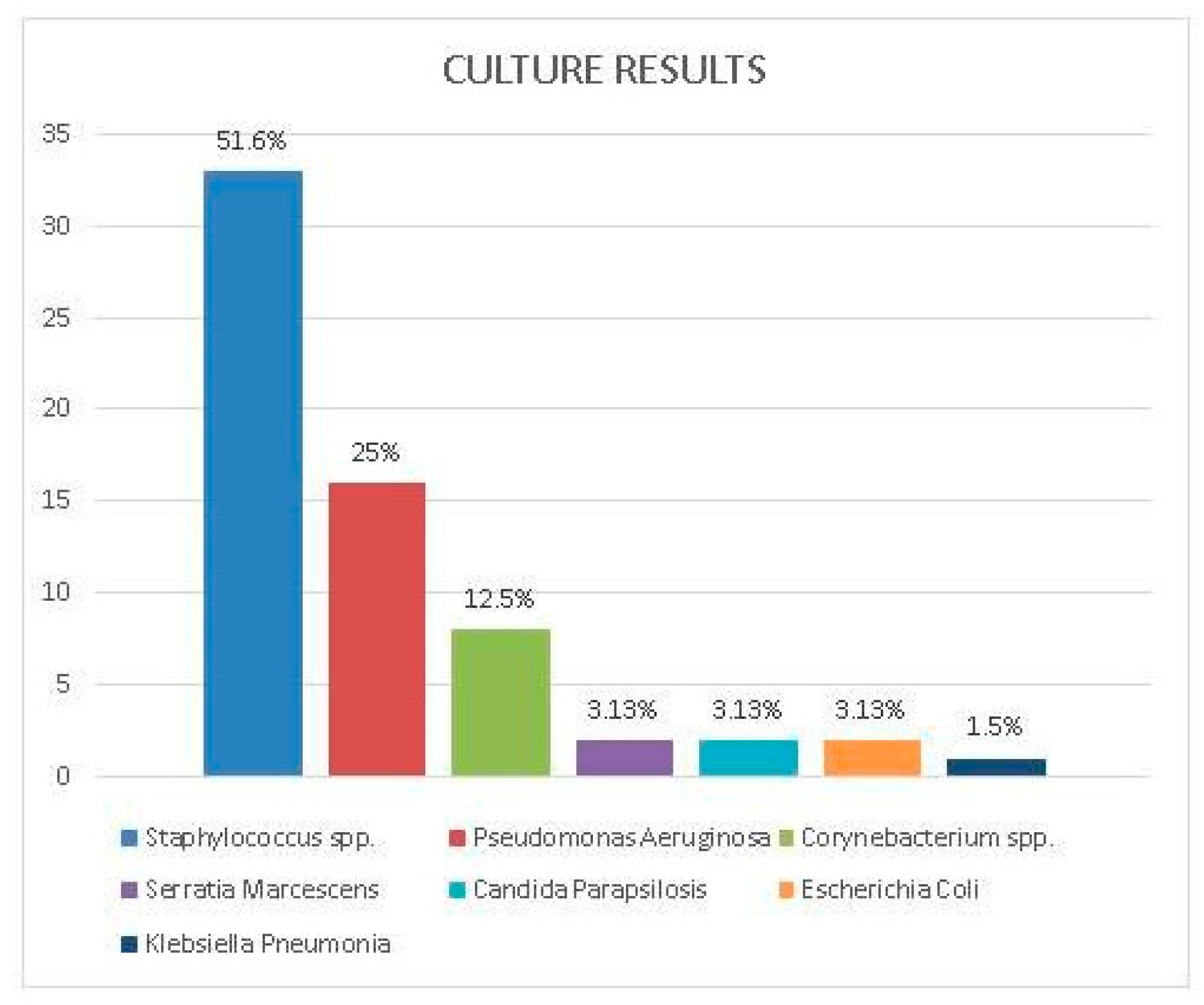

Culture Results

Sixty-four isolates were identified from 55 drainage cultures of 20 patients clinically diagnosed with DLI. The most common isolated microorganisms were

Staphylococcus spp. 33 (51.6%) and Pseudomonas aeruginosa 16 (25.0%). Among staphylococcal isolates,

Staphylococcus aureus accounted for 23 (69.7%), while coagulase-negative

staphylococci (CoNS) represented 10 (30.3%). The prevalence of methicillin resistance was observed to be 36% (14/23) in

S. aureus and 20% (2/10) in

CoNS. Pseudomonas aeruginosa, identified as the second most frequently detected microorganism, was isolated from only from three patients’ cultures. However,

Pseudomonas spp. accounted for recurrent and persistent DLIs. Other detected pathogens were

Corynebacterium spp. (8, 12.5%) and

Enterobacterales (5, 7.8%) including

Serratia marcescens, Escherichia coli and

Klebisella spp. Candida parapsilosis (2, 3.1%) was isolated in two cases following recurrent DLI. Bloodstream infection was observed in only two patients as a complication of DLIs. Identified microorganisms from DL cultures are presented in

Figure 4.

Outcomes and Infection Management

Driveline infections were managed in collaboration with the DMCS team, which included infectious disease specialists. According to swab culture results, 20 patients had targeted antibiotic therapy. The clinical response guided the duration of antimicrobial treatment, type of infection (superficial or deep), pathogen(s), and the opinion of an infectious disease expert. The duration of antimicrobial treatment was meticulously determined, with at least two weeks for superficial DLIs and at least six weeks for deep DLIs. In addition to antibiotic treatment, surgical debridement was performed in 10 patients. Nine of them had DL relocation and were followed with vacuum assisted closure (VAC) until their culture results were negative. Additionally, muscle relocation defines the repositioning and embedding of the driveline inside the rectus muscle fibers beneath the rectus fascia. The surgical team cleansed the DLES with chlorhexidine and hypochlorous acid and dressed it daily, ensuring the highest standards of care (

Figure 5). All patients responded to DL relocation and VAC therapy except one patient who had a resistant DLI despite the recurrent surgical and antibiotic therapies. This one patient received a heart transplant.

Discussion

DMCS has proven to be a highly effective treatment for AdvHF patients [

2]. As the number of cases and the duration of VAD support increase, a new spectrum of long-term complications, including late infections, has emerged. DLI is the most frequent infectious complication on long-term follow-up, with a prevalence of %14-28 [

9,

10,

22,

23,

24]. In this study, we examined the incidence of DLIs in a single institutional cohort of 90 patients with VAD.

The DLI incidence rates observed in our analysis, which was %21.5, are in line with the previous studies [

9,

10,

22,

23,

24]. Gordon et al. [

11] reported that the risk of VAD infection peaked at 18 days post-surgery and was lower and constant after 60 days. Goldstein

et al. [

9] showed that the peak incidence of percutaneous site infections occurred at 6 months, and Spano

et al. [

22] reported the peak incidence of VAD-specific/related infection at 4 months postoperatively. In contrast to the discrepancies observed between observational studies regarding the peak DLI incidence, our data indicate that peak DLI incidence occurred approximately 18 months after VAD implantation. The median number of days from LVAD implantation to first DLI was 513 (IQR=404). We found a clear relationship between the risk of DLIs and the total duration of VAD time (p<0.05). In this context, extended duration of VAD support was associated with higher incidence rates of late-onset DLIs.

Advanced age does not appear to be a risk factor for VAD-specific complications. However, Goldstein et al. found that younger age was a significant risk factor for DLI [

9]. Similarly, we also identified a significant relation between younger age and the risk of DLI (p<0.05). Age under 52 years was an independent risk factor for DLI [H.R.: 9.77 (1.28-74.51)] in our study population. This finding is thought to be due to higher activity rates and, therefore, increased risk of DLES microtrauma in the younger population because of shearing traction or torsion injury.

Raymond et al. [

25] reported a strong correlation between higher body mass index (BMI) and continued weight gain throughout LVAD therapy and the risk of DLIs. However, we could not detect a similar correlation in our cohort (p>0.05). Furthermore, based on the DLI and non-DLI group comparison, the presence of diabetes, hypertension, and renal dysfunction was not found to serve as a risk factor for the development of DLI after VAD support. However, we found that plasma albumin level under 30.4 g/dl was a device-independent risk factor for DLI. It may indicate the essential role of adequate plasma albumin levels for better wound healing, as they support tissue repair and immune function.

Previous microbiological studies revealed predominance of

Staphylococcus and

Pseudomonas aeruginosa in patients with DLIs during DMCS [

10,

11,

22,

24,

26]. Biofilm dissemination and migration along the DL are critical in deep DLI’s. As demonstrated previously,

Staphylococcus spp. is recognized as a biofilm producer and accounts for a higher percentage of initial pathogens in the DLES [

11,

27], which correlates with our findings.

Pseudomonas aeruginosa became more common and complex to treat over time, accounting for mostly progressive, deep DLIs and pump pocket infections. Although

P. aeruginosa was identified in the cultures of three patients, it was isolated in 25% of swab cultures despite all treatment modalities. Failure to achieve sufficient microbiological and clinical response in

P. aeruginosa infections, the second most frequently detected pathogen in this study, due to its biofilm formation capacity despite treatment is quite concerning. In cases where antibiotic treatment for DLIs was ineffective or inadequate, surgical debridement or transposition of the driveline was achieved. Simple incision and drainage with circumferential tissue and biofilm removal around the DL were performed in one of ten patients. However, the remaining nine required rectus muscle relocation in situ or with transposition of the driveline ipsilateral or contralateral site. Following the removal of the coating with biofilm – with velour coating for HVAD patients – the placement of the driveline into the sheath of the rectus muscle was established. They were followed with vacuum-assisted closure (VAC) until their culture results were negative. One of these nine patients was readmitted due to recurrent infection after a 1-year follow-up (11.1%). As stated, similar studies of rectus muscle relocation with or without wound VAC therapy may provide better outcomes. Juraszec et al. [

21] also reported promising results that only 20% of patients treated surgically developed reinfection during follow-up.

Early clinical diagnosis of DLI is supported by laboratory data, microbiology, and imaging findings, on which stage-related management of DLI depends. Bedside ultrasound may help detect the presence of abscess or localized purulent collection along the DL. Computer tomography (CT) is the reference imaging method for staging DLI’s. Positron emission tomography (18F-FDG PET-CT) allows precise localization of infection and assessment of the extent of DLI [

4,

28].

A prior meta-analysis conducted by Bauer et al. [

19] demonstrated that by 12 months post-VAD implantation, device exchange offered no significant benefit in reducing overall mortality or infection recurrence compared to non-exchange approaches. In this series, we tried most non-exchange modalities, including targeted antibiotics, recurrent debridement procedures, removal of velour and biofilm, DL relocation through rectus muscle, and VAC strategies where needed. Repeated counseling of patients and caregivers was ensured after combined surgical management.

Limitations

The presented study has limitations. Firstly, our study is limited by a small sample size, and the research is a single-center retrospective analysis. This caused statistical limitations in calculating associations, such as the relation between DLI state and comorbidities, BMI, and device types. The study also needed an over-presentation of men in our cohort, as in most cohorts treated by VAD. However, these limitations provide valuable insights for future research in this field.

Conclusions

DLIs are common infectious complications after VAD implantation. Currently, prevention and control of DLIs are essential for the management of VAD patients. Surgical resection of the DLES, removal of biofilm and velour, vacuum-assisted strategies, rectus muscle relocation, or omentoplasty have emerged as essential adjuncts to treating DLI in addition to targeted antibiotics. However, no comprehensive guideline exists for diagnosing and surgically treating DLIs. We believe this cohort will pave the way for future randomized trials, offering hope for improved therapy for DLIs; however, future technological evolutionary solutions may eliminate all the drivelines and associated complications.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest with the contents of this article.

Acknowledgements

We sincerely thank Prof. Atilla Elhan, Ankara University School of Medicine for statistical review of the manuscript, and Tuğba Altuntaş Yıldız and Özlem Bektaş as VAD coordinator for patients and caregivers education.

Financial Disclosure Statement

Data extracted from the Avicenna hospital database founded by Ankara University Hospitals and a specified cardiac surgery research database.

Author Contributions

Mehmet Cahit Saricaoglu: Conceptualization, Data curation, Resources, Methodology, Formal analysis, Investigation, Writing—review & editing; Melisa Kandemir: Data curation, Methodology, Formal analysis, Writing – original draft; Elif M. Saricaoglu: Methodology, Formal analysis, investigation, review & editing; Ali Fuat Karacuha: Data curation, Methodology, Formal analysis; Ezel Kadiroglu: Data curation, Methodology, Formal analysis; Mustafa Farah Abdullahi: Data curation, Methodology, Formal analysis; Mustafa Bahadir Inan: Conceptualization, Methodology, Project administration, Formal analysis; Ahmet Ruchan Akar: Conceptualization, Project administration, Resources, Methodology, Supervision, Validation, Writing—review & editing.

Abbreviations

| AdvHF |

Advanced heart failure |

| BiVAD |

Biventricular assist device |

| BMI |

Body mass index |

| CoNS |

Coagulase-negative staphylococci |

| DL |

Driveline |

| DLES |

Driveline exit site |

| DLIs |

Driveline infections |

| DMCS |

Durable mechanical circulatory support |

| HM2 |

HeartMate 2 |

| HM3 |

HeartMate 3 |

| HVAD |

HeartWare |

| ISHLT |

International Society for Heart and Lung Transplantation |

| LV |

Left ventricle |

| LVAD |

Left ventricular assist device |

|

MRSA

|

Methicillin-Resistant Staphylococcus Aureus

|

|

MSSA

|

Methicillin-Sensitive Staphylococcus Aureus

|

| PAP |

Pulmonary artery pressure |

| VAC |

Vacuum assisted closure |

| VAD |

Ventricular assist device |

References

- Peled, Y.; Ducharme, A.; Kittleson, M.; et al. International Society for Heart and Lung Transplantation Guidelines for the Evaluation and Care of Cardiac Transplant Candidates-2024. J Heart Lung Transplant 2024, 43, 1529–628 e54. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Aslam, S.; Cowger, J.; Shah, P.; et al. The International Society for Heart and Lung Transplantation (ISHLT): 2024 infection definitions for durable and acute mechanical circulatory support devices. J Heart Lung Transplant 2024, 43, 1039–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Potapov, E.V.; Antonides, C.; Crespo-Leiro, M.G.; et al. 2019 EACTS Expert Consensus on long-term mechanical circulatory support. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg 2019, 56, 230–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bernhardt, A.M.; Schloglhofer, T.; Lauenroth, V.; et al. Prevention and early treatment of driveline infections in ventricular assist device patients - The DESTINE staging proposal and the first standard of care protocol. J Crit Care 2020, 56, 106–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leuck, A.M. Left ventricular assist device driveline infections: recent advances and future goals. J Thorac Dis 2015, 7, 2151–7. [Google Scholar]

- Patel, C.B.; Blue, L.; Cagliostro, B.; et al. Left ventricular assist systems and infection-related outcomes: A comprehensive analysis of the MOMENTUM 3 trial. J Heart Lung Transplant 2020, 39, 774–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krzelj, K.; Petricevic, M.; Gasparovic, H.; Biocina, B.; McGiffin, D. Ventricular Assist Device Driveline Infections: A Systematic Review. Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 2022, 70, 493–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hannan, M.M.; Husain, S.; Mattner, F.; et al. Working formulation for the standardization of definitions of infections in patients using ventricular assist devices. J Heart Lung Transplant 2011, 30, 375–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldstein, D.J.; Naftel, D.; Holman, W.; et al. Continuous-flow devices and percutaneous site infections: clinical outcomes. J Heart Lung Transplant 2012, 31, 1151–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simpson, M.T.; Ning, Y.; Kurlansky, P.; et al. Outcomes of treatment for deep left ventricular assist device infection. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 2024, 167, 1824–32 e2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gordon, R.J.; Weinberg, A.D.; Pagani, F.D.; et al. Prospective, multicenter study of ventricular assist device infections. Circulation 2013, 127, 691–702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- John, R.; Aaronson, K.D.; Pae, W.E.; et al. Drive-line infections and sepsis in patients receiving the HVAD system as a left ventricular assist device. J Heart Lung Transplant 2014, 33, 1066–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Contreras, F.J.; Pinsker, B.L.; Katz, J.N.; et al. Value of nutritional indices in predicting survival free from pump replacement and driveline infections in centrifugal left ventricular assist devices. JTCVS Open 2024, 19, 175–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dettbarn, E.; Prenga, M.; Stein, J.; et al. Driveline infections in left ventricular assist devices-Incidence, epidemiology, and staging proposal. Artif Organs 2024, 48, 83–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pagani, F.D. Driveline Infections Associated With Durable Left Ventricular Assist Device Support: An Ounce of Prevention is Worth a Pound of Cure. ASAIO J 2022, 68, 1459–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cagliostro, B.; Levin, A.P.; Fried, J.; et al. Continuous-flow left ventricular assist devices and usefulness of a standardized strategy to reduce drive-line infections. J Heart Lung Transplant 2016, 35, 108–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yarboro, L.T.; Bergin, J.D.; Kennedy, J.L.; et al. Technique for minimizing and treating driveline infections. Ann Cardiothorac Surg 2014, 3, 557–62. [Google Scholar]

- Kusne, S.; Mooney, M.; Danziger-Isakov, L.; et al. An ISHLT consensus document for prevention and management strategies for mechanical circulatory support infection. J Heart Lung Transplant 2017, 36, 1137–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bauer, T.M.; Choi, J.H.; Luc, J.G.Y.; et al. Device exchange versus nonexchange modalities in left ventricular assist device-specific infections: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Artif Organs 2019, 43, 448–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wadiwala, I.; Garg, P.; Alamouti-Fard, E.; et al. Absorbable antibiotic beads for treatment of LVAD driveline infections. Artif Organs 2024, 48, 559–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Juraszek, A.; Smolski, M.; Kolsut, P.; et al. Prevalence and management of driveline infections in mechanical circulatory support - a single center analysis. J Cardiothorac Surg 2021, 16, 216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spano, G.; Buffle, E.; Walti, L.N.; et al. Ten-year retrospective cohort analysis of ventricular assist device infections. Artif Organs 2023, 47, 898–905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Puschel, A.; Skusa, R.; Bollensdorf, A.; Gross, J. Local Treatment of Driveline Infection with Bacteriophages. Antibiotics (Basel) 2022, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Topkara, V.K.; Kondareddy, S.; Malik, F.; et al. Infectious complications in patients with left ventricular assist device: etiology and outcomes in the continuous-flow era. Ann Thorac Surg 2010, 90, 1270–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raymond, A.L.; Kfoury, A.G.; Bishop, C.J.; et al. Obesity and left ventricular assist device driveline exit site infection. ASAIO J 2010, 56, 57–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koval, C.E.; Stosor, V.; Practice, AICo. Ventricular assist device-related infections and solid organ transplantation-Guidelines from the American Society of Transplantation Infectious Diseases Community of Practice. Clin Transplant 2019, 33, e13552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toba, F.A.; Akashi, H.; Arrecubieta, C.; Lowy, F.D. Role of biofilm in Staphylococcus aureus and Staphylococcus epidermidis ventricular assist device driveline infections. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 2011, 141, 1259–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernhardt, A.M.; Pamirsad, M.A.; Brand, C.; et al. The value of fluorine-18 deoxyglucose positron emission tomography scans in patients with ventricular assist device specific infections dagger. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg 2017, 51, 1072–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).