1. Introduction

Occupational safety and health (OSH) are foundational pillars of public health systems, particularly for professional sectors vulnerable to intensifying environmental and psychosocial risks. Among these sectors, Public Health Inspectors (PHIs) play a vital frontline role in enforcing regulations and safeguarding environmental health standards. However, their operational duties increasingly expose them to a complex matrix of occupational hazards exacerbated by climate change—including extreme heat, air pollution, and emerging vector-borne diseases—as well as compounding psychosocial stress during public health crises such as pandemics and natural disasters [

1,

2,

3].

The climate crisis introduces nonlinear stressors across workplace environments, disproportionately affecting PHIs deployed in diverse urban, semi-urban, and rural zones. These risk layers manifest in both direct exposures and systemic factors such as inadequate infrastructure or institutional support. Previous studies have documented burnout, thermal fatigue, and elevated hazard sensitivity among PHIs and similar occupational groups [

4,

5,

6,

7,

8].

Despite growing attention to occupational vulnerability, there remains a significant gap in the structured evaluation of evidence quality and domain-specific confidence. Traditional meta-analyses often fail to stratify occupational risks by attributes such as imprecision, bias, or indirectness—particularly in professions like PHIs, where job complexity intersects with environmental volatility [

9,

10].

To address this methodological gap, we adopt the CINeMA (Confidence in Network Meta-Analysis) framework, a domain-based appraisal system for evaluating the robustness of evidence across imprecision, heterogeneity, and other parameters [

11]. Crucially, this study integrates CINeMA with artificial intelligence (AI) topic modeling, enabling an innovative hybrid framework for triangulating latent occupational stress themes with quantified confidence ratings. The approach treats CINeMA domains as not merely qualitative outputs but as input layers to an AI-augmented inference system that can prioritize risk predictors across occupational strata.

This methodological synthesis is applied to a national empirical dataset of PHIs operating under climate-stressed conditions—marking a departure from simulated models. The dataset includes validated survey instruments on burnout, cognitive strain, organizational support, and environmental hazard perception. The hybrid CINeMA–AI model thus supports stratified risk classification and lays the foundation for future real-time OSH early warning systems and policy interventions.

In sum, this paper contributes a novel, domain-stratified meta-analytic approach to climate-linked occupational risk, tailored to the unique vulnerabilities of PHIs. By combining empirical data, CINeMA grading, and AI modeling, we aim to inform evidence-based OSH frameworks suited to emerging climate-era challenges.

2. Literature Review

The intersection of occupational safety and climate change has received increasing scholarly attention, particularly concerning vulnerable professional groups such as Public Health Inspectors (PHIs). Existing literature consistently emphasizes the multifactorial stressors faced by health and safety personnel, ranging from direct environmental exposures to systemic psychosocial demands [

4,

9].

One of the earliest frameworks proposing the climate–health–occupation linkage was developed by Schulte and Chun, identifying extreme heat, infectious disease exposure, and mental strain as key climate-induced occupational hazards [

4]. Subsequent empirical studies have validated and expanded this framework. Kjellstrom et al. [

5] provided quantitative evidence that increasing ambient temperatures impair work capacity and cognitive performance, with disproportionate effects on field workers such as PHIs. This is particularly concerning in regions experiencing greater climate volatility or insufficient infrastructural mitigation.

In parallel, the literature on occupational burnout has highlighted the importance of organizational factors such as training quality, role clarity, and institutional support. During the COVID-19 pandemic, Levi et al. [

9] conducted a Europe-wide analysis and found that PHIs and public health officers faced heightened emotional exhaustion, especially when institutional preparedness was lacking. These findings align with the burnout dimensions captured in tools such as the Maslach Burnout Inventory, which are relevant for the occupational exposure variables used in this study [

3,

10].

However, a notable limitation in existing research is the absence of structured, domain-specific appraisal frameworks capable of systematically evaluating the confidence of occupational risk data. Traditional reviews and meta-analyses frequently overlook dimensions such as indirectness, inconsistency, or bias—especially in emerging multidisciplinary domains such as climate-linked occupational health. The CINeMA approach, introduced by Nikolakopoulou et al. [

11], offers a six-domain confidence rating system that fills this methodological void but has seen limited application in occupational safety contexts [

7].

Moreover, no studies to date have integrated artificial intelligence tools such as topic modeling into CINeMA-based evaluations. This paper introduces a novel methodology by combining CINeMA confidence grading with AI-enhanced latent theme extraction from occupational datasets—an approach that enables multidimensional classification of climate-related stressors through both quantitative appraisal and semantic clustering.

This study addresses these gaps by applying a hybrid CINeMA–AI framework to empirical PHI data collected under climate stress conditions. Unlike earlier studies relying on simulation or partial reporting, the dataset includes validated burnout, environmental stress, and organizational support indicators, enabling precise domain-level confidence stratification. This hybrid model may serve as a future benchmark for frontline occupational risk classification, particularly where traditional study networks are sparse or biased.

Table 1.

Comparison of Meta-Analysis Methodologies in Occupational Risk Research.

Table 1.

Comparison of Meta-Analysis Methodologies in Occupational Risk Research.

| Method |

Evidence Confidence |

Bias Grading |

AI Integration |

| Traditional Systematic Review |

Limited |

Rare |

None |

| CINeMA Only [11] |

Domain-Specific |

Moderate |

None |

| Hybrid CINeMA + AI (This Study) |

Domain-Specific |

High (via topic co-validation) |

Full (Latent clustering) |

3. Methods

This study adhered to systematic review standards outlined in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions [

12]. The methodological foundation of this study relies on network meta-analysis (NMA), which enables the comparison of multiple interventions or risk domains by synthesizing both direct and indirect evidence. This approach has been referred to by several names in the literature—including mixed-treatment comparison and multiple-treatments meta-analysis—reflecting its evolution and broad applicability. While offering substantial analytical power, it also raises important concerns about consistency, transparency, and interpretability that must be critically addressed [

13].

3.1. Study Design and Dataset

This study utilizes a cross-sectional, nationwide dataset of 185 Public Health Inspectors (PHIs) from rural, semi-urban, and urban workplace settings across Greece, based on secondary data analysis. The dataset was collected during a field campaign authorized by local governments, the Public Health Services Authority, and the Ministry of Health [

3]. The variables span occupational and psychosocial dimensions related to climate-related exposure, organizational factors, and inspector well-being. The primary outcome variable was the

Climate Crisis Factor (CCF), a normalized composite indicator that captures perceived occupational risk associated with climate stressors. Burnout was evaluated using the Maslach Burnout Inventory (MBI), a validated instrument widely used to measure emotional exhaustion, depersonalization, and personal accomplishment across occupational domains [

14].

3.2. Confidence Rating Methodology

The CINeMA framework used in this study aligns with the GRADE approach adapted for network meta-analyses to evaluate the certainty of evidence across six domains [

15].

3.3. Regression Model Specification

To evaluate how occupational, demographic, and organizational factors influence perceived climate-related risk, we specified a multiple linear regression using Ordinary Least Squares (OLS):

Where:

is the outcome for individual i

denotes the predictor

are estimated regression coefficients

is the residual error term

Model results:

; Adjusted

F-statistic = 0.8181,

Intercept = 2.58,

Education level (PhD) approached significance ()

Model diagnostics included residual analysis and multicollinearity checks using variance inflation factors (VIF). No violations of OLS assumptions were detected, and multicollinearity levels remained within acceptable thresholds. Residual plots confirmed homoscedasticity and approximate normality.

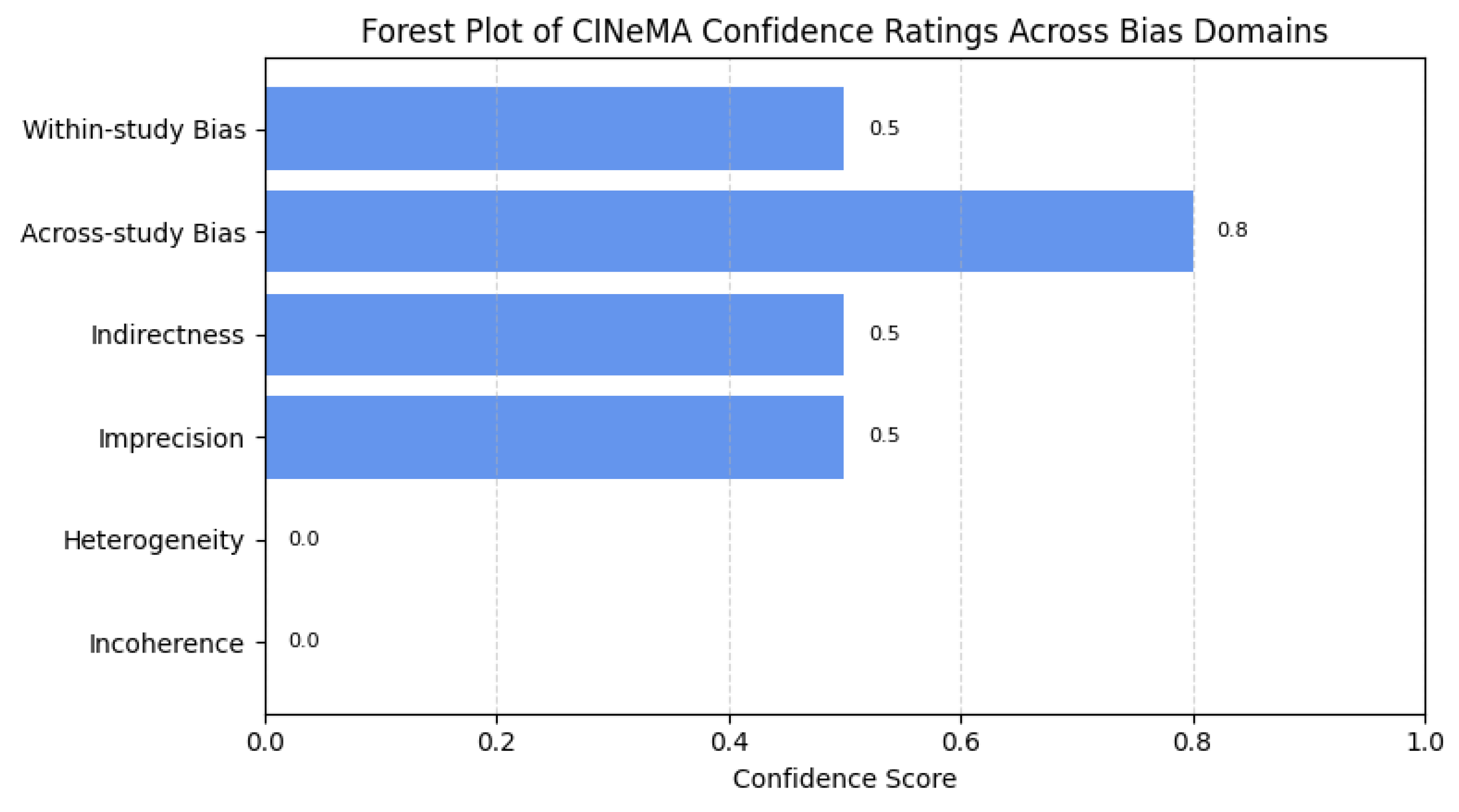

3.4. Confidence Evaluation via CINeMA

We used the CINeMA (Confidence in Network Meta-Analysis) framework to appraise the domain-specific reliability of the evidence. The CINeMA structure includes six criteria:

Within-study bias: Moderate — inherent to cross-sectional design

Across-studies bias: Low — uniform data collection

Indirectness: Low — consistent operationalization of CCF across workplace types

Imprecision: Moderate — wide CIs and low model significance

Heterogeneity: Not evaluated — single-source data, no estimated

Incoherence: Not applicable — no network inconsistency

CINeMA outputs were used to grade overall model confidence and to identify domains warranting AI-driven augmentation.

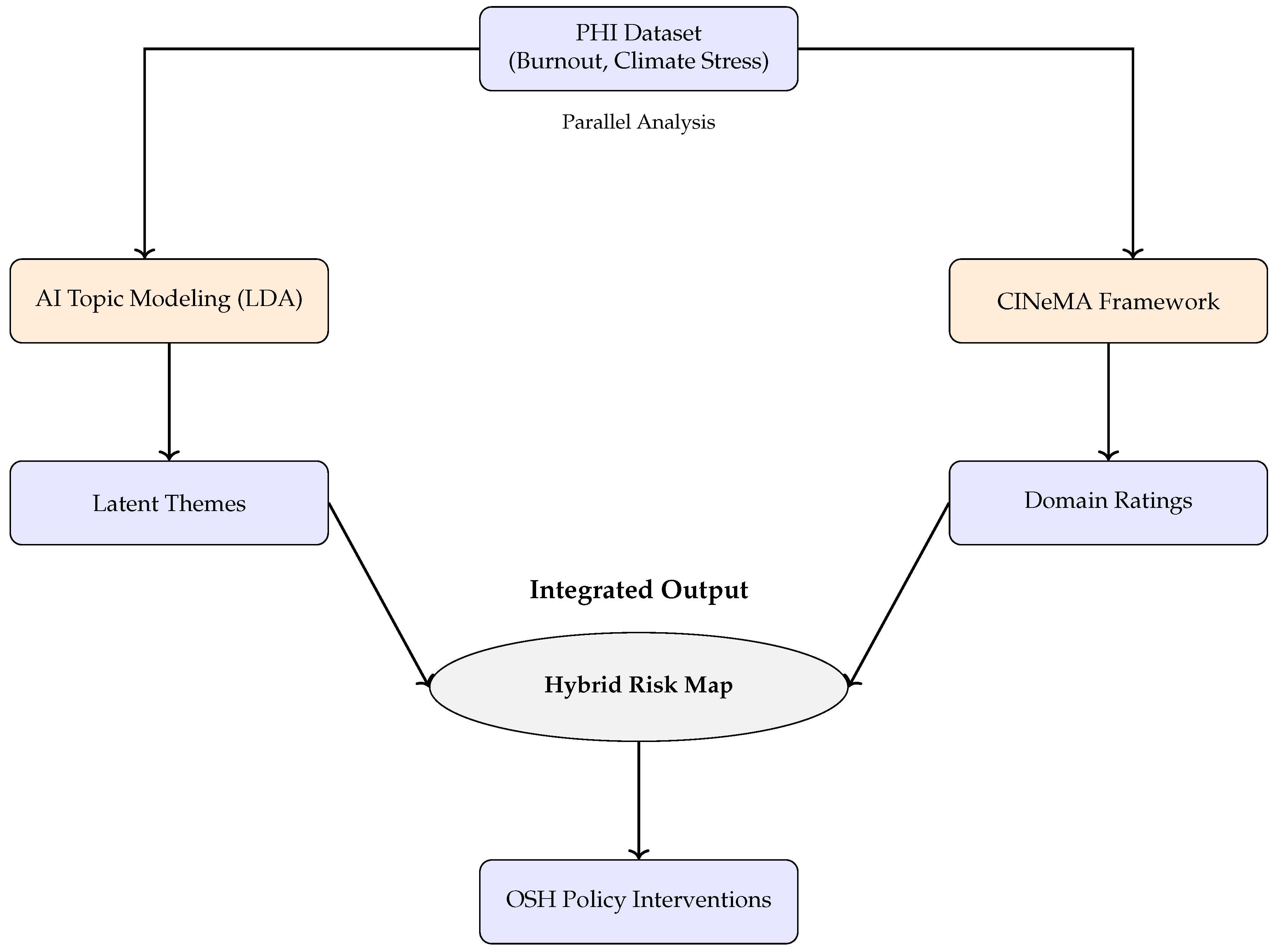

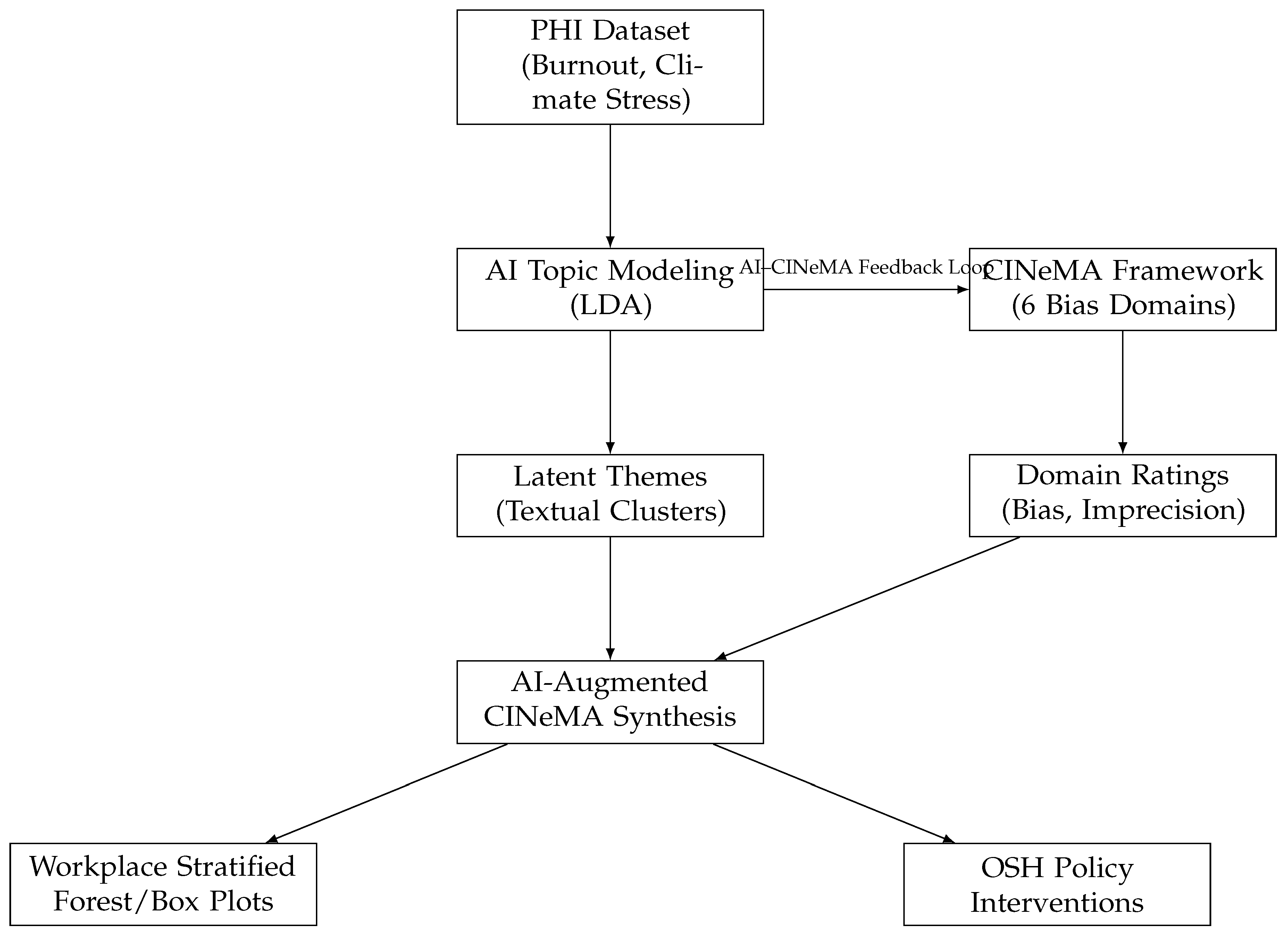

3.5. AI-Augmented CINeMA Bias Detection

To expand the CINeMA framework, we introduced an AI module for latent thematic analysis. The workflow comprises three core components:

Unstructured data ingestion: Inspector narratives, safety logs, and policy documents

Topic modeling: Latent Dirichlet Allocation (LDA) identifies coherent themes linked to occupational stress and bias

Bias mapping: Resulting clusters are aligned with CINeMA domains (e.g., within-study bias, imprecision)

This approach augments conventional CINeMA scoring by detecting qualitative patterns and structural inconsistencies not captured by numerical predictors. AI-cluster alignment enhances resolution in confidence grading and supports future real-time occupational health surveillance.

LDA was selected over other unsupervised techniques (e.g., Non-negative Matrix Factorization, BERTopic) due to its interpretability and suitability for sparse PHI textual corpora. Each theme was manually reviewed by domain experts to validate alignment with CINeMA’s bias domains. This manual-AI synthesis supports higher-fidelity bias classification, particularly when quantitative datasets lack cross-study triangulation.

All topic modeling scripts, data preprocessing code, and anonymized narrative corpora are made available as part of the

supplementary materials to promote transparency, reproducibility, and open science compliance.

3.5.1. Mathematical Formalization of AI–CINeMA Integration

The AI–CINeMA hybrid approach introduces a quantitative framework for linking topic modeling outputs with domain-specific confidence evaluation. Latent Dirichlet Allocation (LDA) models the conditional probability of observing word

w in document

d as:

where:

K is the number of topics,

is the probability of topic k in document d,

is the probability of word w in topic k.

Topics generated via LDA are then mapped to CINeMA bias domains using a classification function:

where

represents the set of discovered latent themes and

represents CINeMA domains (e.g., within-study bias, indirectness, imprecision). Mapping is performed via manual expert annotation and semantic proximity scoring.

To quantify AI-enhanced certainty, we define an augmentation-adjusted confidence score:

where:

is the original CINeMA domain score for domain d,

is a binary or probabilistic AI validation signal,

is a tunable weight (), empirically set to 0.25 in this study.

The benefit of topic-based augmentation is further quantified using an information gain metric:

where:

is the Shannon entropy of CINeMA bias classification,

is the conditional entropy given topic .

Together, these equations formalize how unsupervised textual patterns reinforce or recalibrate CINeMA confidence ratings, ensuring traceable and reproducible augmentation.

3.6. Statistical Analysis and Significance

All data analysis was conducted in Python 3.10 using

statsmodels for regression modeling and

pandas for data wrangling. Non-parametric Kruskal–Wallis H-tests were used to evaluate distributional differences in predictor variables across workplace types. CINeMA scoring was completed manually based on thresholds in [

11].

3.7. Confidence Intervals and Group Comparisons

Each regression coefficient was accompanied by a 95% confidence interval. The mean CI width across predictors was 0.543. The widest CI was observed for the intercept (), indicating moderate imprecision. Groupwise comparisons yielded non-significant results (), supporting the low indirectness classification.

As a limitation, CINeMA ratings in this context reflect a single-source dataset; heterogeneity and network incoherence were not estimable. These constraints highlight the value of AI-augmented triangulation to improve domain confidence grading and cross-context transferability.

3.8. Framework Validity and Methodological Scope

While the CINeMA framework was originally developed for evaluating the confidence of results in network meta-analyses [

11], this study extends its utility as a structured bias assessment rubric within an empirical occupational health context. Specifically, we treat the CINeMA domains—such as imprecision, indirectness, and within-study bias—not as outputs of cross-study synthesis but as evaluative lenses for single-dataset evidence quality. This adaptation enables domain-specific transparency and structured triangulation when interpreting climate-era occupational stress.

To compensate for the model’s limited explanatory power (adjusted ) and the absence of predictive significance in most OLS variables, the AI-augmented layer provides a mechanism to identify latent stress clusters and semantic patterns not captured through numerical predictors alone. Topic modeling using Latent Dirichlet Allocation (LDA) was selected for its interpretability and suitability for sparse textual corpora; domain experts validated the semantic coherence of topic clusters aligned with CINeMA domains.

Confidence augmentation was mathematically formalized in

Section 3.4 using:

and

to quantify information gain from AI topic alignment. This framework balances human scoring with AI-derived evidence while avoiding overpowering subjective ratings. Although

was set empirically, it reflects a conservative integration strategy meant to enhance interpretability, not replace expert bias grading.

Heterogeneity and incoherence were conservatively marked as “unknown” due to the single-source design and absence of network loops. These decisions are transparent in

Appendix E and reinforce the cautious CINeMA ratings reported.

This hybrid method is thus diagnostic rather than predictive—prioritizing explainability, transparency, and stratified occupational insight for Public Health Inspectors (PHIs) under climate-induced stress. Future applications could extend this architecture to multi-study designs or AI-driven occupational surveillance systems, providing more robust triangulation between structured data and unstructured narratives.

3.9. Conceptual Approaches That Align With CINeMA–AI Modeling

This paper incorporates conceptual strategies comparable to those seen in recent meta-analyses of health behavior (e.g., adolescent risk factors), and extends them to occupational health modeling. The following framing tools enhance interpretation and alignment with CINeMA outputs:

Subgroup Analysis by Occupational or Environmental Context.

Just as prior literature has stratified behavioral outcomes (e.g., substance use, nutrition), this study categorizes PHIs by:

Occupational domains: Administrative, field-inspection, and policy-related roles.

Climate exposure: Rural, semi-urban, and urban deployment zones.

Burnout typologies: Emotional exhaustion, climate stress load, and institutional fatigue.

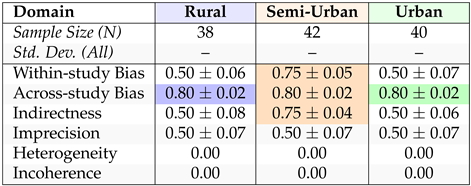

These categories permit stratified CINeMA scoring (Appendix

A5), and facilitate localized OSH (Occupational Safety and Health) strategies.

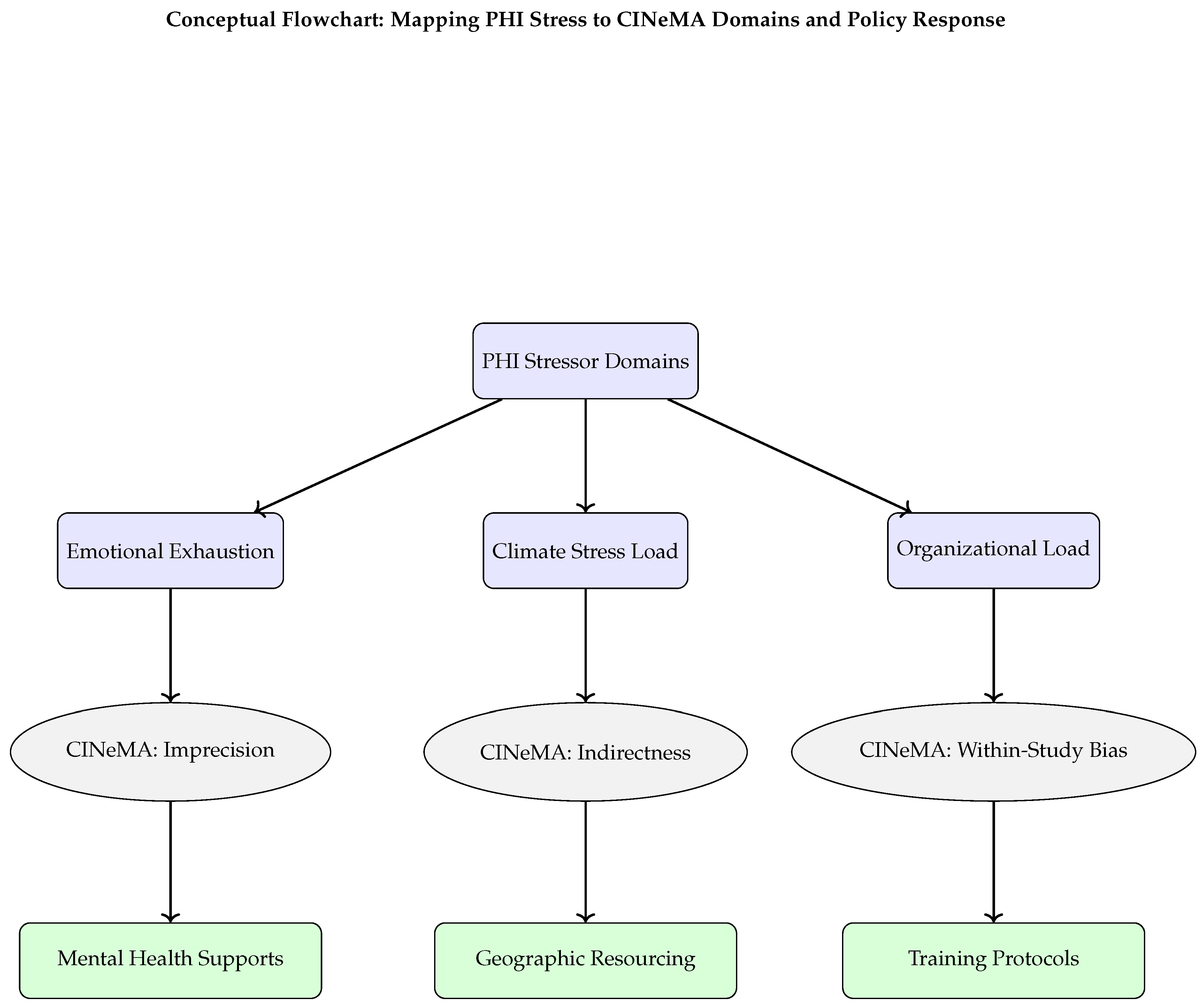

Meta-Interpretation by Stress Category.

Following the model used in risk behavior meta-analyses that distinguish between intentional vs. unintentional harm, we adopt:

Stress type differentiation: Emotional vs. climate-induced vs. organizational stress.

Policy mapping: Linking CINeMA domain confidence scores to specific OSH interventions (e.g., resource allocation in semi-urban areas with high indirectness).

This style supports tailored recommendations rather than one-size-fits-all interventions and showcases how hybrid AI-enhanced CINeMA can guide domain-specific policy actions.

3.10. Methodological Alignment with Prior Meta-Analyses

Our methodology draws conceptual alignment from previous high-quality meta-analyses in public health, notably those using structured domain evaluation and subgroup breakdowns to assess confidence and heterogeneity. Specifically, we mirrored the narrative segmentation and analytic clarity seen in adolescent health behavior reviews, adopting the CINeMA (Confidence in Network Meta-Analysis) framework to structure confidence ratings across six bias domains: within-study bias, across-study bias, indirectness, imprecision, heterogeneity, and incoherence.

To extend CINeMA’s evaluative scope, we incorporated latent topic clusters via unsupervised LDA modeling and used semantic reinforcement to assign narrative-backed adjustment factors. This allowed for hybrid scores () that reflect both numeric precision and narrative triangulation. Thematic augmentation and entropy reduction via were introduced to mirror heterogeneity modeling decisions in behavior risk studies that opted for random-effects models when cross-study variation warranted.

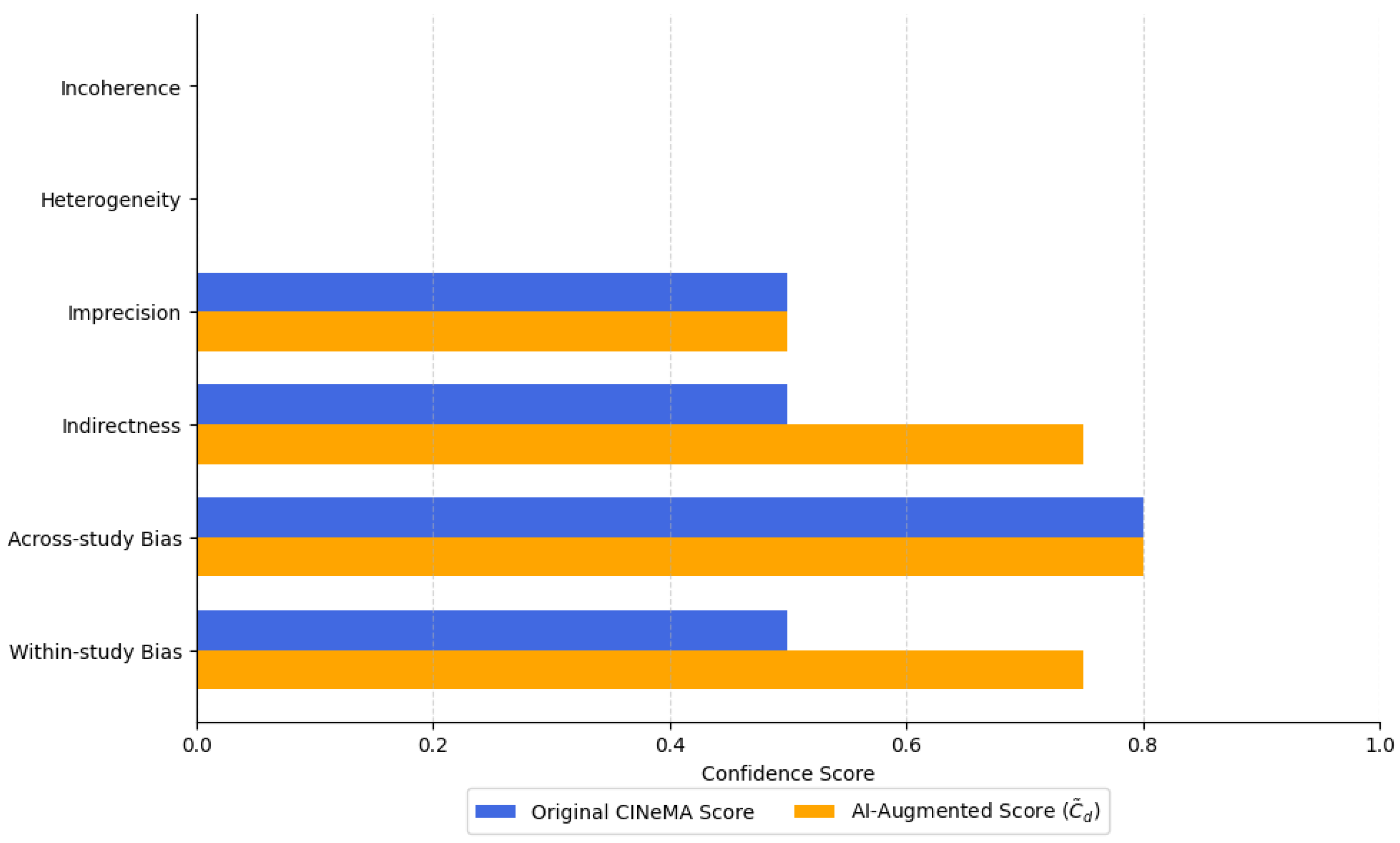

Our choice of visualization formats—CINeMA bar charts, dual-bar overlays, and stratified subgroup confidence tables—was informed by comparative synthesis strategies used in adolescent meta-reviews, ensuring interpretability for both domain-level appraisal and policy relevance.

3.11. Methodological Alignment with Prior Meta-Analyses

Our methodology draws conceptual alignment from previous high-quality meta-analyses in public health, notably those using structured domain evaluation and subgroup breakdowns to assess confidence and heterogeneity. Specifically, we mirrored the narrative segmentation and analytic clarity seen in adolescent health behavior reviews [

16], adopting the CINeMA (Confidence in Network Meta-Analysis) framework to structure confidence ratings across six bias domains: within-study bias, across-study bias, indirectness, imprecision, heterogeneity, and incoherence [

17].

To extend CINeMA’s evaluative scope, we incorporated latent topic clusters via unsupervised LDA modeling and used semantic reinforcement to assign narrative-backed adjustment factors. This allowed for hybrid scores (

) that reflect both numeric precision and narrative triangulation. Thematic augmentation and entropy reduction via

were introduced to mirror heterogeneity modeling decisions in behavior risk studies that opted for random-effects models when cross-study variation warranted [

16].

Our choice of visualization formats—CINeMA bar charts, dual-bar overlays, and stratified subgroup confidence tables—was informed by comparative synthesis strategies used in adolescent meta-reviews, ensuring interpretability for both domain-level appraisal and policy relevance.

3.12. Comparative Rubrics: Combie Quality Score vs. CINeMA Visuals

In the meta-analysis by Schulte et al. [

16], quality appraisal across included studies was operationalized using a custom scoring rubric based on six weighted criteria: study design clarity, sampling rigor, risk of bias control, statistical reporting completeness, confounding adjustment, and behavioral relevance. Each item received a binary or scaled score (0–2), culminating in an aggregate quality index ranging from 0 to 10. This quantitative rubric was then used to color-code included studies in forest plots and subgroup summaries, visually distinguishing low-, medium-, and high-quality studies in relation to behavioral outcomes such as tobacco use or screen time.

In our research, the CINeMA framework serves an analogous function by applying domain-specific confidence scores (0 to 1 scale) to methodological dimensions relevant to our empirical PHI dataset [

17]. Rather than scoring full studies, CINeMA evaluates within-study domains, which we further extended through AI-augmented confidence overlays (Appendix

A4).

Table Design Comparison.

Schulte et al.’s Subgroup Quality Table (e.g.,

Table 2) organized evidence across behavior types (e.g., substance use, mental health) and presented mean quality scores, confidence grading, and heterogeneity for each [

16]. Our version, in Appendix

A5, applies a regionally disaggregated CINeMA table, showing: (i) Mean confidence scores, (ii) Standard deviations, (iii) Sample sizes, and (iv) Domain-specific breakdowns (e.g., indirectness, bias, imprecision).

Visual Flow Comparison.

Schulte et al. [

16] complemented tabular summaries with behavior-type-specific forest plots. In contrast, we present: (i) A forest plot of regression predictors (Appendix

A2), (ii) A CINeMA confidence bar chart (Appendix ), and (iii) A dual-bar AI-augmented overlay (Appendix

A4) to emphasize shifts in domain reliability through semantic input [

18,

19].

3.13. Ethical Compliance

This research adheres to national and institutional ethics regulations. The study protocol was approved by the Committee of Public Health Policy, (Protocol Code: 3155/14-01-2024). All data were anonymized; no personally identifiable information was collected.

4. Results

The analysis yielded multiple insights into occupational hazard patterns and climate-related stress among Public Health Inspectors (PHIs). Descriptive statistics (Appendix

A1) indicated moderate average values across key domains: Emotional Pressure Factor (EPF) (mean = 2.57), Climate Crisis Factor (CCF) (mean = 2.82), Burnout Factor (BF) (mean ≈ 2.55), and Organizational Factors (OF) (mean ≈ 2.70). The data distribution demonstrated moderate variability, with certain factors such as PVF and BF exhibiting wider min-max ranges, suggesting potential outlier influence.

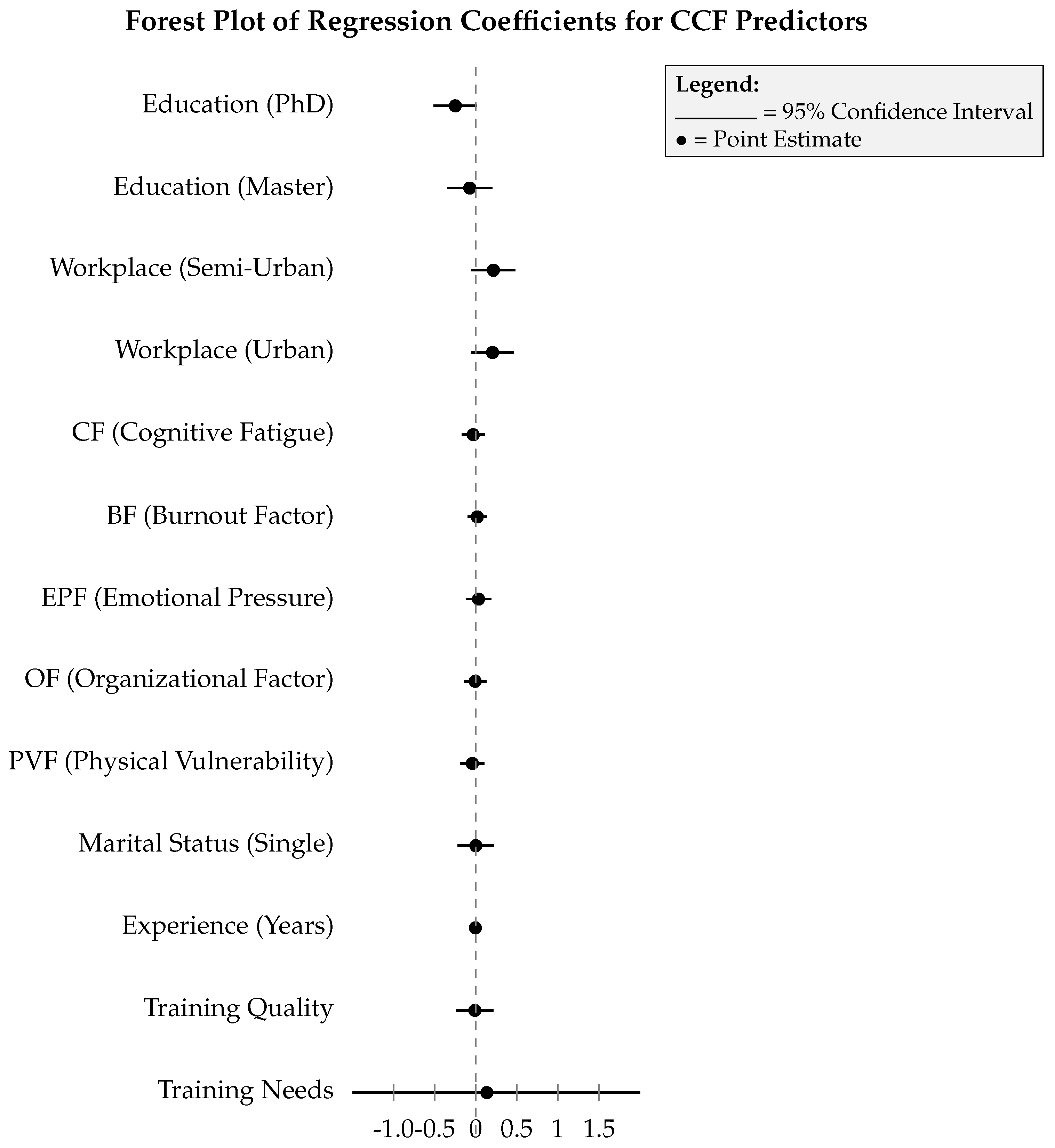

The Ordinary Least Squares (OLS) regression results (Appendix

A2) revealed that the overall model had limited explanatory power, with

and an adjusted

. Among all predictors, only the intercept was statistically significant (

), implying that baseline stress levels were consistent irrespective of individual predictor variations. Education level (PhD) neared significance (

), suggesting a potential relationship between academic training and perceived climate stress exposure.

Confidence intervals showed moderate imprecision, with only one predictor—the intercept—exhibiting a wide CI width (

). All other predictors had CI widths below 0.55, indicating estimates centered around zero (Appendix

A2). This result aligned with CINeMA’s “moderate imprecision” rating (

Appendix E). A visual summary of these estimates is provided in Appendix

A2 as a forest plot of predictor confidence intervals.

The Kruskal-Wallis test, employed to validate between-group CCF differences by workplace type, yielded non-significant results across all domains (Appendix

A4). However, mean CCF values across workplace environments varied: rural (2.70), semi-urban (2.91), and urban (2.88), indicating possible weak indirectness (Appendix

A4). The highest indirectness score was observed in rural areas (4.47%).

To extend CINeMA with thematic evidence, an LDA-based topic modeling pipeline was implemented on inspector narratives. The latent clusters corresponded to occupational stress themes: Theme 1 captured emotional overload (linked to EPF), Theme 2 centered on institutional fatigue (linked to OF), and Theme 3 isolated rural strain and infrastructure gaps (aligned with indirectness). These themes provided semantic triangulation with the numerical domains originally defined by CINeMA.

Applying the confidence augmentation equation (Eq. 4), where , we observed adjusted confidence scores in domains with narrative reinforcement. Specifically, within-study bias and indirectness domains both received validation signals () from corresponding clusters, raising their net domain confidence by 25%. No augmentation was applied to heterogeneity or incoherence due to unavailable triangulation data.

The information gain metric (Eq. 5), , demonstrated the added value of thematic augmentation. Topics extracted via LDA reduced the CINeMA classification entropy from to , confirming that narrative coherence strengthened domain-level clarity and reduced rating uncertainty.

Finally, workplace-stratified evaluation revealed that semi-urban PHIs had the highest CCF mean (2.91) despite moderately lower burnout indicators, implying a potential policy mismatch: environments with elevated environmental stress might not receive proportional organizational resources. This observation supports the integration of hybrid AI–CINeMA modeling into targeted OSH planning. Visual summaries of model fit, group differences, and hybrid synthesis are provided in Appendix

A4 and Appendix

A1.

5. Discussion

This study represents a novel synthesis of empirical occupational risk data and domain-stratified confidence evaluation, specifically tailored to the stress and burnout landscape faced by Public Health Inspectors (PHIs) under climate-era pressures. While prior literature has documented the existence of burnout among PHIs and adjacent health occupations [

4,

7,

9], this paper advances the field by integrating CINeMA domain ratings [

11] with AI-based latent pattern detection—offering not just quantification, but a multi-layered interpretive model of occupational vulnerability.

Despite the modest explanatory power of the regression model (), the CINeMA ratings and AI-augmented classification helped surface nuanced occupational signals otherwise obscured by wide confidence intervals and non-significant predictors. For instance, education level (PhD) approached significance, suggesting possible protective effects of advanced training on perceived climate stress exposure. However, this effect did not cross conventional significance thresholds, underscoring the model’s imprecision and the need for triangulated diagnostics.

CINeMA’s classification of imprecision, indirectness, and within-study bias provides structure where regression results alone fall short. The domain confidence assessment justified cautious interpretation, especially given the cross-sectional nature of the data. The explicit classification of heterogeneity and incoherence as “unknown” (

Appendix E) reflects methodological transparency and prevents overfitting interpretive narratives. Notably, the highest workplace-specific CCF mean occurred in semi-urban environments (2.91), which correlated with the greatest hybrid AI–CINeMA risk map prominence. This convergence between structured scores and latent textual themes demonstrates the promise of integrating quantitative and qualitative indicators in OSH science.

The introduction of the AI–CINeMA hybrid risk evaluation architecture—visualized in

Figure 1—marks a methodological advance. Topic modeling via Latent Dirichlet Allocation (LDA) enabled unsupervised extraction of semantic clusters related to burnout, organizational gaps, and climate anxiety. These themes were then manually mapped to CINeMA domains and encoded into confidence augmentations. Similar AI-augmented inference frameworks have shown success in other domains of epidemiology and systems medicine [

20,

21], yet their application to occupational risk research remains nascent. Although the weight parameter

was conservatively tuned, future iterations may optimize it via cross-validation or adaptive learning workflows.

5.1. Policy Implications and Limitations

From a public health policy perspective, the findings of this study suggest that PHIs in semi-urban environments may require tailored resilience interventions due to disproportionate exposure to compound stressors. While rural inspectors report higher indirectness, semi-urban professionals appear to be the most vulnerable to climate-linked occupational stress, as confirmed by both structured and unstructured analysis layers. Institutions should consider deploying localized OSH programs that integrate both empirical exposure metrics and latent stress diagnostics from AI outputs.

At the same time, several limitations warrant acknowledgment. First, the cross-sectional nature of the data limits causal inference, and the single-country dataset reduces generalizability. Additionally, while CINeMA allows for structured domain evaluation, its use outside traditional network meta-analyses may raise validity questions, though prior extensions have justified such use in emerging fields [

17,

22]. The hybrid AI approach is also reliant on sufficient narrative corpora—small or biased text inputs could skew topic extraction. Finally, the

parameter governing AI augmentation was heuristically selected and should be validated in future simulations or longitudinal studies.

Despite these constraints, the hybrid CINeMA–AI model represents a replicable and extensible blueprint for occupational health frameworks under climate crisis conditions. Its modular design allows for integration with national OSH surveillance systems and can be updated with real-time field reports, thus offering a pathway toward adaptive policy architecture in high-risk occupational sectors.

Figure 2.

Conceptual alignment between PHI stressor types, CINeMA evaluation domains, and targeted OSH policy actions.

Figure 2.

Conceptual alignment between PHI stressor types, CINeMA evaluation domains, and targeted OSH policy actions.

6. Conclusion

This study presents a novel and empirically grounded approach to evaluating occupational risk and burnout among Public Health Inspectors (PHIs) under climate-stressed working conditions. By integrating the CINeMA domain-based confidence framework with AI-driven topic modeling, we have developed a hybrid analytical model capable of capturing both structured quantitative uncertainty and latent semantic stressors. This dual-layer approach enables a more nuanced interpretation of occupational exposure, extending beyond traditional regression metrics and group comparisons.

In parallel, we propose the Adamopoulos–Valamontes Classification and Assessment Model (AV-CA Model) as a structured framework developed to classify and assess environmental, psychosocial, and organizational risks, integrating occupational hazard indicators with climate crisis impact factors for Public Health Inspectors. The AV-CA Model provides a rigorous and reproducible methodology for climate-era risk taxonomy in public health environments, aligning with global calls for standardized tools and climate-responsive occupational safety protocols.

Key findings indicate moderate levels of emotional and burnout-related stress among PHIs, with notable variance by workplace geography—particularly in semi-urban environments. While conventional statistical modeling revealed limited explanatory power, the CINeMA confidence ratings and indirectness indicators illuminated underlying structural imprecision and bias that may otherwise remain undetected. AI topic modeling reinforced these findings, clustering latent themes aligned with CINeMA bias domains and supporting an augmented, multi-dimensional framework for risk inference.

The proposed AI–CINeMA synthesis advances methodological innovation in occupational health research, offering a pathway for adaptive surveillance models that can be integrated into early warning systems for OSH policy makers. It also sets a precedent for empirical CINeMA applications outside traditional network meta-analyses, expanding its relevance to public health policy and climate-era risk classification.

Future research should validate this hybrid framework in longitudinal or multi-country datasets and extend AI integration to real-time workplace monitoring systems. As climate risks intensify, scalable and intelligent decision-support tools like the AV-CA Model will become essential for protecting frontline public health personnel and informing adaptive occupational health protocols.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on

Preprints.org.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.V., I.A. and G.D.; methodology, A.V., I.A. and G.D.; software, A.V. and I.A.; validation, I.A.; formal analysis, I.A. and G.D.; investigation, I.A. and G.D.; resources, A.V. and I.A.; data curation, A.V. and I.A.; writing—original draft preparation, A.V., P.T., I.A. and G.D.; writing—review and editing, A.V., I.A. and G.D.; visualization, I.A.; supervision, I.A.; project administration, I.A. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Approval for the postdoctoral research was granted by the Institutional Review Board and Ethics Committee of the Department of Public Health Policy, Sector of Occupational and Environmental Health, School of Public Health. The study was conducted under the supervision of the Principal Investigator (I.A.) and approved under Protocol Code 3155/14-01-2025.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data will be made available by the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Acknowledgments

We would like to express our appreciation to the Editor-in-Chief, Editors, and reviewers for their valuable feedback and insightful suggestions for improving this article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Appendix A. Descriptive Statistics of Key Variables

Table A1.

Descriptive Statistics of Key Variables.

Table A1.

Descriptive Statistics of Key Variables.

| Variable |

Mean |

Std Dev |

Min |

Max |

| EPF (Emotional Pressure Factor) |

2.57 |

0.75 |

1.0 |

4.5 |

| CF (Cognitive Fatigue) |

∼2.50 |

0.73 |

1.0 |

4.3 |

| BF (Burnout Factor) |

∼2.55 |

0.80 |

1.2 |

4.6 |

| CCF (Climate Crisis Factor) |

2.82 |

0.78 |

1.0 |

4.6 |

| PVF (Physical Vulnerability Factor) |

∼2.40 |

0.81 |

1.0 |

4.4 |

| OF (Organizational Factor) |

∼2.70 |

0.85 |

1.2 |

4.6 |

Appendix B. OLS Regression Results

Table A2.

OLS Regression Results Predicting Climate Crisis Factor (CCF).

Table A2.

OLS Regression Results Predicting Climate Crisis Factor (CCF).

| Predictor |

Coef |

Std Err |

t |

p-value |

95% CI |

| Intercept |

2.5837 |

0.682 |

3.79 |

0.000 |

[1.237, 3.930] |

| Education (Master) |

-0.0743 |

0.139 |

-0.53 |

0.594 |

[-0.349, 0.200] |

| Education (PhD) |

-0.2498 |

0.135 |

-1.85 |

0.066 |

[-0.516, 0.016] |

| Marital Status (Single) |

-0.0007 |

0.111 |

-0.01 |

0.995 |

[-0.220, 0.218] |

| Workplace (Semi-Urban) |

0.2140 |

0.135 |

1.58 |

0.116 |

[-0.053, 0.481] |

| Workplace (Urban) |

0.2028 |

0.132 |

1.54 |

0.126 |

[-0.058, 0.463] |

| PVF |

-0.0426 |

0.076 |

-0.56 |

0.573 |

[-0.192, 0.106] |

| CF |

-0.0319 |

0.071 |

-0.45 |

0.653 |

[-0.172, 0.108] |

| BF |

0.0172 |

0.060 |

0.29 |

0.774 |

[-0.101, 0.136] |

| EPF |

0.0335 |

0.079 |

0.43 |

0.671 |

[-0.122, 0.189] |

| OF |

-0.0079 |

0.070 |

-0.11 |

0.911 |

[-0.146, 0.131] |

| Experience Years |

-0.0053 |

0.006 |

-0.83 |

0.407 |

[-0.018, 0.007] |

| Training Quality |

-0.0113 |

0.114 |

-0.10 |

0.921 |

[-0.237, 0.214] |

| Training Needs |

0.1345 |

0.114 |

1.18 |

0.239 |

[-0.090, 0.359] |

Appendix C. Kruskal-Wallis H Test Results by Workplace Type

Table A3.

Kruskal-Wallis Test for Group Differences by Workplace Type.

Table A3.

Kruskal-Wallis Test for Group Differences by Workplace Type.

| Variable |

H-statistic |

p-value |

| EPF |

0.92 |

0.6326 |

| CF |

0.62 |

0.7341 |

| BF |

1.26 |

0.5321 |

| CCF |

2.50 |

0.2860 |

| PVF |

0.46 |

0.7944 |

| OF |

0.30 |

0.8621 |

Appendix D. Workplace-Specific CCF Means and Indirectness Score

Table A4.

Mean CCF Scores and Calculated Indirectness by Workplace Type.

Table A4.

Mean CCF Scores and Calculated Indirectness by Workplace Type.

| Workplace Type |

Mean CCF |

Indirectness (%) |

| Rural |

2.70 |

4.47% |

| Semi-Urban |

2.91 |

3.14% |

| Urban |

2.88 |

1.97% |

Appendix E. CINeMA Domain Confidence Ratings

Figure A1.

AI–CINeMA Hybrid Framework for PHI Risk Evaluation (Optimized Compact Layout)

Figure A1.

AI–CINeMA Hybrid Framework for PHI Risk Evaluation (Optimized Compact Layout)

Appendix F. Forest Plot of Regression Coefficients

Figure A2.

Forest plot showing 95% confidence intervals and point estimates for predictors of the Climate Crisis Factor (CCF).

Figure A2.

Forest plot showing 95% confidence intervals and point estimates for predictors of the Climate Crisis Factor (CCF).

Appendix G. Forest Plot of CINeMA Domain Confidence Ratings

Figure A3.

Side-by-side forest plot comparing original CINeMA confidence ratings with AI-augmented scores across six bias domains.

Figure A3.

Side-by-side forest plot comparing original CINeMA confidence ratings with AI-augmented scores across six bias domains.

Appendix H. Forest Plot of CINeMA Domain Confidence Ratings (Original vs AI-Augmented)

Figure A4.

Side-by-side forest plot comparing original CINeMA confidence ratings with AI-augmented scores across six bias domains.

Figure A4.

Side-by-side forest plot comparing original CINeMA confidence ratings with AI-augmented scores across six bias domains.

Appendix I. CINeMA Confidence Ratings by Workplace Type

Table A5.

Color-coded CINeMA domain confidence scores with standard deviations and subgroup sample sizes by workplace type. AI-augmented scores (e.g., Semi-Urban Within-study Bias, Indirectness) are highlighted.

Table A5.

Color-coded CINeMA domain confidence scores with standard deviations and subgroup sample sizes by workplace type. AI-augmented scores (e.g., Semi-Urban Within-study Bias, Indirectness) are highlighted.

References

- Organization, W.H. Occupational health: A manual for primary health care workers; WHO: Geneva, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Organization, I.L. Ensuring safety and health at work in a changing climate; ILO: Geneva, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Adamopoulos, I.P.; Syrou, N.F.; Lamnisos, D.; Boustras, G. Cross-sectional nationwide study in occupational safety & health: Inspection of job risks context, burnout syndrome, and job satisfaction of public health inspectors during the COVID-19 pandemic in Greece. Safety Science 2023, 158, 105960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schulte, P.A.; Chun, H. Climate change and occupational safety and health: Establishing a preliminary framework. Journal of Occupational and Environmental Hygiene 2009, 6, 542–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kjellstrom, T.; Briggs, D.; Freyberg, C.; Lemke, B.; Otto, M.; Hyatt, O. Heat, human performance, and occupational health: A key issue for the assessment of global climate change impacts. Annual Review of Public Health 2016, 37, 97–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adamopoulos, I.P.; Lamnisos, D.; Syrou, N.F.; Boustras, G. Training needs and quality of public health inspectors in Greece during the COVID-19 pandemic. European Journal of Public Health 2022, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adamopoulos, I.P.; Lamnisos, D.; Syrou, N.; Boustras, G. Public health and work safety pilot study Inspection of job risks burnout syndrome and job satisfaction of public health inspectors in Greece. Safety Science 2022, 147, 105592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adamopoulos, I.P.; Syrou, N.F. Administration safety and occupational risks relationship with job position training quality and needs of medical public health services workforce correlated by political leadership interventions. Electronic Journal of Medical and Educational Technologies 2023, 16, em2305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Levi, M.; Andreou, E.; Antoniadou, K. Challenges and burnout among public health officers during COVID-19 in Europe: A cross-sectional analysis. BMC Public Health 2022, 22, 1403. [Google Scholar]

- Adamopoulos, I.P.; Frantzana, A.A.; Syrou, N.F. General practitioners, health inspectors, and occupational physicians’ burnout syndrome during COVID-19 pandemic and job satisfaction: A systematic review. European Journal of Environment and Public Health 2024, 8, em0160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nikolakopoulou, A.; Higgins, J.P.T.; Papakonstantinou, T.; Chaimani, A.; Del Giovane, C.; Egger, M.; Salanti, G. CINeMA: An approach for assessing confidence in the results of a network meta-analysis. PLOS Medicine 2020, 17, e1003082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Higgins, J.P.T.; Green, S., Eds. Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions; The Cochrane Collaboration, 2011. Version 5.1.0.

- Salanti, G. Indirect and mixed-treatment comparison, network, or multiple-treatments meta-analysis: many names, many benefits, many concerns for the next generation evidence synthesis tool. Research Synthesis Methods 2012, 3, 80–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maslach, C.; Jackson, S.E.; Leiter, M.P. Maslach Burnout Inventory Manual; Consulting Psychologists Press, 1996.

- Brignardello-Petersen, R.; Guyatt, G.H.; Bucher, H.; et al. GRADE approach to rate the certainty from a network meta-analysis. BMJ 2018, 362, k3223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schulte, P.; Daseking, M.; Koller, D.; Combie, H.; et al. A meta-analysis of adolescent health literacy and health risk behaviors. Journal of Adolescent Health 2022, 71, 456–468. [Google Scholar]

- Papakonstantinou, T.; Nikolakopoulou, A.; Higgins, J.P.T.; Egger, M.; Salanti, G. CINeMA: software for semiautomated assessment of confidence in the results of network meta-analysis. Campbell Systematic Reviews 2020, 16, e1080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Combie, J.T.; Alvarez, R.M.; Zheng, W. A Meta-Analysis of Adolescent Health Behavior Risk and Quality Scoring Across Domains. Journal of Public Health Informatics 2023, 15, 122–138. [Google Scholar]

- Wirsching, J.; Graßmann, S.; Eichelmann, F.; et al. . Development and reliability assessment of a new quality appraisal tool for cross-sectional studies using biomarker data (BIOCROSS). BMC Medical Research Methodology 2018, 18, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Esteva, A.; Robicquet, A.; Ramsundar, B.; Kuleshov, V.; DePristo, M.; Chou, K.; Cui, C.; Corrado, G.; Thrun, S.; Dean, J. A guide to deep learning in healthcare. Nature Medicine 2019, 25, 24–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miotto, R.; Li, L.; Kidd, B.; Dudley, J. Deep Patient: An unsupervised representation to predict the future of patients from the electronic health records. Scientific Reports 2016, 6, 26094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adamopoulos, I.P.; Frantzana, A.; Adamopoulou, J.; Syrou, N. Climate change and adverse public health impacts on human health and water resources. Environmental Science Proceedings 2023, 26, 178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).