1. Introduction

Dementia is a degenerative disorder affecting language, memory, and cognition (McCurry & Drossel, 2011), which presents uniquely for each individual but typically with behavioural changes (Buchanan et al., 2008). Data from the World Health Organisation (2023) suggests that over 55 million of the world’s population have a diagnosis of dementia, with 10 million new cases diagnosed per year. Dementia is also recognised as a disability by the United Nations Convention on the Rights of People with Disabilities (UNCRPD, 2024), meaning that the human rights and fundamental freedoms of people living with dementia (PLwD) are recognised and protected under the convention. This includes people’s right to access appropriate psychosocial supports that allow them to live independent, engaged, and fulfilled lives for as long as possible (Alzheimer Society of Ireland, 2016; UNCRPD, 2024).

A decline in functional abilities in dementia is commonly observed and may occur before a formal diagnosis (Karr et al., 2018). Functional decline can negatively impact one’s ability to independently perform activities of living (ADLs) (Cipriani et al., 2020), and is associated with an increased risk of hospitalisation and admission into long-term care (Brown et al., 2019). Whilst independence and functional ability is often dependent on disease-type and stage, functional decline can also be attributable to “excess disability” (Reifel & Larson, 1990; Yates et al., 2019). Excess disability arises when disempowerment and restricted perceptions of what PLwD can do reduces their opportunities to function to the best of their ability (Kitwood, 1990). McGowan et al. (2019) outlined the importance of supporting PLwD to engage in meaningful daily activities, such as personal grooming and household tasks, and identified ‘meaningful activities’ as an evidence-based intervention for the non-cognitive symptoms of dementia. Creating opportunities for engagement that support independence can also help to sustain good quality of life (Health Information and Quality Authority, 2016; Trahan et al., 2011) and maintain connectedness (A. Han et al., 2016) for PLwD in community and care settings. Estimates suggest that up to 72% of individuals in residential care are diagnosed with dementia with different levels of functionality (Pierse et al., 2019). The literature on activity engagement in residential care suggests that PLwD experience disempowerment (Hung & Chaudhury, 2011) and are rarely provided with adequate opportunities to engage independently in ADLs and instrumental ADLs (den Ouden et al., 2015; Tak et al., 2015).

Research on behavioural interventions with participants with dementia has shown positive outcomes in relation to engagement in recreational activities (Engstrom et al., 2015) and self-care tasks (Engelman et al., 2003). Supporting PLwD to continue to engage in activities and self-care can be challenging as individuals experience worsening cognitive symptoms over time, including a reduced capacity to learn (Sturmey et al., 2020; Fisher et al., 2007) and changes in stimulus control (Aggio et al., 2018). The PLwD experiences a decline in motivation to interact with discriminative stimuli (SD) due to a decrease in the reinforcing contingencies experienced (Skinner, 1983) even though reinforcement is still available (Brenske et al., 2008). The ability of an SD to evoke behaviour that once commenced or progressed a behaviour chain decreases in effectiveness (Sturmey et al., 2020; Fisher et al., 2007). This can mean that the ability of PLwD to engage in activities decreases over time; this may even occur for behaviours they want to engage in and have in their repertoire, but various levels of support would be required to support continued engagement as the condition progresses (Brenske et al., 2008). Non-socially mediated antecedent interventions, such as wayfinding signs to find the bathroom (Namazi & Johnson, 1991) and socially mediated antecedent interventions, such as staff prompting a PLwD to use the bathroom (Ouslander, 1995) may enhance the disparity and salience of stimuli evoking desired behaviour. These interventions should ideally be present in any long- or short-term care setting to promote independence and reduce excess disability, although research suggests this is often not the case (Orth et al., 2019).

Activities of daily living are examples of behaviour chains that PLwD complete throughout the day to function (Mlinac & Feng, 2016). ADLs include mobilising, eating and personal hygiene activities (Laver et al., 2021). ADLs are activities that PLwD have in their repertoire, but due to cognitive changes, they may be unable to commence or continue the chain of behaviour needed to complete the task independently (Mlinac & Feng, 2016). The inability to respond independently creates varying levels of dependency, often reducing the individual’s QoL (Lichtenstein et al., 1985; Millá N-Calenti et al., 2010). Research shows that PLwD can be supported to engage in ADLs when adapted appropriately, which in return can increase QoL, reduce caregiver burden and improve cognitive and functional outcomes (Gitlin et al., 2008; S. S. Han et al., 2022; Prizer & Zimmerman, 2018). The way in which healthcare staff communicate with PLwD can create a relationship of dependency (Baltes & Wahl, 1996; Slaughter et al., 2011). The methods of presenting the steps of ADLs by the healthcare worker are essential for promoting independence levels (Rogers et al., 2000). Baltes et al. (1994) described the “dependency-support script” as providing care according to expectation, i.e., due to age or diagnoses rather than individual ability and within context.

Prompting is a method used to increase independent engagement with activities (Engelman, 1999; Trahan, Kuo, et al., 2014; Zanetti et al., 2001). Prompting can act as an antecedent intervention delivered verbally or visually by another individual or technology that works as an SD to evoke a response within the behaviour chain, resulting in the PLwD interacting with the next step in the activity. Most-to-least prompting is effective for individuals when skills are absent from their repertoire, as it allows for fading prompts within a task when stimulus control is transferred, so the individual can complete a task independently (Libby et al., 2008). A least-to-most (L-M) approach may be more appropriate for individuals with the skill in their repertoire to increase their engagement with the task (Engelman et al., 1999). L-M prompting also creates effortful learning conditions, which support positive learning outcomes for PLwD (Clare & Jones, 2008). The delivery of instruction from staff should be simple, positive and direct (A. J. Buchanan et al., 2018), which could be achieved through gestures, pointing and verbal instruction. Research on prompting has demonstrated increased activity engagement (Brenske et al., 2008), independence with ADLs (Engelman, 1999), and decreasing occurrence of incontinence (Burgio et al., 1990; Lancioni et al., 2011). Prompt type, cognitive impairment and contextual variables are essential to consider when delivering prompts to the PLwD. While prompting has demonstrated some efficacy in increasing independence for PLWD, the research is somewhat limited. Examining maintenance and generalisation of prompt use is also required, as continued use of L-M prompting for PLwD could sustain engagement in ADLs for longer (Coyne & Hoskins, 1997; Kelly et al., 2019; Trahan, Kuo, et al., 2014; Zanetti et al., 2001).

To promote increased independence in ADLs for PLwD, healthcare staff could be trained in behavioural intervention techniques such as prompting, fading, shaping and task analysis (Baker et al., 2015; Trahan et al., 2011). Healthcare staff often receive dementia training through lectures and presentations but tend not to engage in role-play, modelling and feedback for skill development. The transfer of new information has been shown not to develop into practice (Burgio et al., 2002; Gardner, 1972) or only maintained for short periods (Aylward et al., 2003). The effectiveness of staff training can be measured through resident behaviour change, the ability of staff to apply the intervention across residents, settings, and activities (generalisation) and the continued use of the intervention over time (maintenance) (Jahr, 1998). Buchanan et al. (2011) state that it has yet to be identified how best to train the sustainable practices of healthcare staff to promote independence for PLwD.

Behaviour Skills Training (BST) is a well-researched method of training staff to implement behavioural support (Lerman et al., 2015) and has been used to improve staff performance in intervention delivery (Palmen et al., 2010; Sherman et al., 2021). Gormley et al. (2019) reported a significant positive effect of using BST to teach behavioural procedures to front-line staff, compared to a control group. Participants gained and generalised skills quickly when instruction, role-play, modelling, and feedback were combined. BST has been shown to be effective for teaching multiple skills to different groups of trainees (Courtemanche et al., 2021; Alaimo et al., 2018). Parsons et al. (2012) outline the six steps for BST when applying this model to staff who work in the care environment. These steps involve 1. Describing the target skill, 2. Providing staff with a written description of the skill, 3. Demonstrating the target skill for staff, 4. The staff member must practice the target skill, 5. A supervisor provides feedback during a practice session, and 6. Repeat steps 4 and 5 until the staff member reaches the mastery criteria. In their systematic review, Slane & Lieberman-Betz (2021) identified three essential components to quality research in BST: reporting primary outcomes, generalised outcomes, and the maintenance of outcomes. When examining the effects of interventions in settings with vulnerable populations, research design should also be a primary consideration. The Oxford Centre for Evidence-Based Medicine ranks single case experimental designs (SCEDs) as Level 1 evidence similar to randomised experiments (Howick et al., 2011). Although SCEDs have long been a central feature of behavioural research, SCEDs have only gained interest within the health (Tanious & Onghena, 2019) and rehabilitation sectors (Shadish, 2014) in more recent years. There is now recognition that SCEDs are especially important to optimise personalised, and person-centred intervention approaches (Dallery & Raiff, 2014).

The current study aimed to teach healthcare staff how to increase opportunities for independent responding for PLwD by using task analyses and L-M prompting during ADLs. The intervention assessed the impact of BST on healthcare staff delivery of L-M prompting on the steps of the task (as dictated by the task analysis) during standing, drinking and brushing teeth, and assessed if performance was maintained over time. Staff behaviour was evaluated to determine whether the skills learned generalised to other ADLs without direct training and feedback. The What Works Clearinghouse (WWC) (Kratochwill et al., 2010) Technical Documentation was adhered to which outlines design standards for SCDs. The Single-Case Reporting Guideline in BEhavioural Interventions (SCRIBE) were referenced for reporting outcomes (Tate et al., 2016). A randomised multiple-baseline design (MBD) was used to determine whether a functional relationship exists between the intervention (BST) and the outcome of staff implementing L-M prompting during service user ADLs. Within-case (phase) randomisation was included per the recommendations of Levin et al. (2019). Per the WWC guidelines, an effect replication was assessed across at least three goals per participant, with at least 3-5 data points per phase (baseline and intervention). A social validity questionnaire examined staff experiences with BST and whether they would engage in this type of training in the future.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

Participants were three healthcare assistants employed to work with PLwD in a dementia-specific respite centre (mean age of 42.67, SD = 16.82) with an average of 14.4 years of working there. Participants were required to have a minimum six-month experience carrying out care duties for at least 12 hours a week in the centre. All participants had completed a Further Education and Training Awards Council (FETAC) level 5 in Care of the Older Person and had attended in-house training that included Dementia Awareness, Behaviours that Challenge, and Stress Management.

2.2. Setting

The study took place in a dementia-specific respite centre. PLwD came to the centre from living in the community with their family or caregiver, availed of two weeks of respite care, and returned home again. All training sessions occurred in a large dayroom, and staff observations occurred during daily work routines throughout the respite centre.

2.3. Experimental Design

A randomised single-case experimental MBD across participants was used to measure the effects of BST on the participant’s target behaviours. The dependent variable (DV) was the proportion of correct responses when staff were required to use L-M prompting with a task analysis for supporting ADLs (assistance to stand, assistance to drink, brushing teeth). As per guidelines for conducting randomised SCEDs, participants were randomly assigned to predetermined baseline and intervention lengths for each ADL (

Table 1) (Kratochwill et al., 2013; Levin et al., 2019). The BST intervention was implemented in a staggered manner for each participant using case-randomisation procedure as described by Levin & Kratochwill (2021). The ADLs that participants engaged in with the PLwD occurred during the day within their natural work routine. The MBD (n=3) was replicated across three ADLs: ADL 1: assistance to stand, ADL2: assistance with drinking, and ADL3: assistance to brush teeth. The multiple baseline allowed participants to act as a control for themselves and to facilitate the measurement of the BST effect across participants on each task (Horner et al., 2005).

2.4. Measurement

The DV was the percentage of correct responses the participant achieved within the task analysis using L-M prompting during each ADL. This percentage was calculated by giving each step a percentage value. Ten steps in the task analysis would mean 10% per step where L-M prompting was correctly used, and six correct responses correspond to 60% correct overall (Courtemanche et al., 2021; Alaimo et al., 2018). The L-M prompting sequence used was: verbal prompt → verbal and gestural prompt → model prompt → physical prompt (Engelman et al., 2003; Miltenberger, 2016) with a three-second time delay between prompts (Wolery et al., 1990). That is, if the PLwD did not respond within three seconds of the first level prompt (verbal), the next prompt level was offered. Data was recorded on the following: the consistent use of the L-M prompting on each step of the task analysis, the 3-second delay between prompt levels, using a total task chaining method so that all steps of the task analysis were complete while allowing the PLwD to chain behaviours where they could independently, i.e., without any prompting (Miltenberger, a2016). Participants were expected to use social reinforcement through appropriate communication and verbal encouragement.

A step on the task analysis was marked correct if the following occurred: L-M prompting was used at each step with the 3-second time delay. If the resident chained steps of the task together independently without prompting when they could, each step on the task analysis was marked as correct for the participant (i.e., the participant facilitated fully independent responding from the resident). If the resident did not engage in a step and the participant used L-M prompting, this was marked as correct. A step on the task analysis was marked as incorrect if one of the following occurred: not using the L-M prompting levels, not allowing for the 3-second time delay, or not allowing the PLwD to chain steps independently without prompting when they could. The correct answers were added, and a percentage represented the number of steps on the task analysis that the participant delivered correctly.

2.5. Procedure

2.5.1. Baseline

The researcher used a task analysis data collection sheet (available upon request) to gather baseline data on the participant’s use of L-M prompting during each step of the task when assisting a resident to stand, drink, and brush their teeth. Baseline observations occurred in the natural environment and as part of the participant’s daily routine with a PLwD. Participants did not receive the task analysis for baseline data observations; they were asked to carry out the ADL as they usually would with a PLwD, and no instruction or feedback was given at this time (Sarokoff & Sturmey, 2004; Sherman et al., 2021).

2.5.2. Intervention

BST used the following six steps 1. describe the target skill, 2. provide a succinct, written description of the skill, 3. demonstrate the target skill, 4. Require the trainee to practice the target skill, and 5. provide feedback during practice (Parsons et al., 2012). Steps 4 and 5 were repeated until the participant completed their assigned intervention data points. Steps 1 and 2 were verbal and written training, steps 3 and 4 were rehearsal training, and steps 5 and 6 were performance-based training (Reid et al., 2021). Steps 1 – 5 were the intervention, while step 6 is where data was taken on participants post-intervention, i.e., receiving feedback for improvement following observation.

Step 1. Describe the Target Skill. Participants learned to implement the target behaviour using the L-M prompting hierarchy during each task analysis step. The target behaviours that participants were required to engage in through the behaviour skills training were: (1) Assisting a PLwD to stand occurs when a resident sitting in a chair stood up under a participant’s prompting (e.g., verbal suggestion) to move from that chair to another location. This did not include the participant placing their hand on a resident to guide or lift them from the chair as a first action; (2) Assisting a PLwD to take a drink occurred when a resident asked for and was offered a drink; they accepted and took a drink. This did not include the participant lifting the cup to the resident’s mouth as a first action; and (3) Assisting a PLwD to brush their teeth occurred when the resident brushed their teeth under when directed to do so. This did not include the participant brushing the resident’s teeth for them.

Step 2. Provide a Written Description of the Skill. Staff received a written description of their expected responses while undergoing direct observations for each target behaviour (Sarokoff & Sturmey, 2004). Participants received an information sheet that included their target behaviour, an operational definition of their target behaviour, the task analysis steps, and a description of the least to most prompting.

Step 3. Demonstrate the Target Skill. In a role-play scenario, the researcher demonstrated the L-M prompting on each task analysis step with another staff member, and participants were allowed task questions (Courtemanche et al., 2021).

Step 4. The Trainee is Required to Practice the Target Skill. Observations of participants began when they performed the target skill in a role-play scenario where they received feedback and had the opportunity to ask questions (Sawyer et al., 2017). Data on observations commenced when participants were observed in their interactions with a PLwD using L-M prompting during the ADLs.

Step 5. Provide Feedback During Practice. The researcher adopted the use of an evidence-based protocol for feedback. 1. Open with a positive statement, 2. Reflect on what was performed correctly, 3. State what was performed incorrectly, 4. State how the incorrectly performed steps need to be performed, 5. Allow time for questions, and 6. End on a positive statement (Reid et al., 2021).

2.5.3. Generalisation

Observations of assisting a resident to take a piece of food and putting on a jumper were observed under the same conditions as the baseline phase after participants completed all three ADLs baseline and intervention phases (Palmen et al., 2010). These observations allowed the researcher to assess for generalisation of participant learning to break down activities and apply L-M prompting across ADLs that the intervention did not directly target. One of the ADLs to test for generalisation was purposefully similar to assisting with a drink, and the other was not similar to assess for skills transfer. Participants were not given a written description of the skill.

Assisting a PLwD to take a piece of food during a meal occurred when the PLwD had their meal at the table, and used their utensils to take food into their mouths independently. This did not include the participant bringing a utensil to the resident’s mouth as a first action.

Assisting a PLwD to put on a jumper occurred when the resident chose what to wear, held the jumper the right way up, put their arms and head through, and fixed it to sit on their body independently. This did not include the participant placing the jumper on the PLwD as a first step.

2.5.4. Maintenance

Maintenance observations occurred two weeks after each intervention stage was completed for each ADL. Maintenance sessions were under the same conditions as the baseline phase, where participants were instructed to implement each step of the task analysis with a PLwD, and no further instruction or feedback was given (Schmidt, 2016).

2.5.5. Social Validity

A brief ‘social validity’ questionnaire was given to participants to get feedback on their experience with BST in the dementia care setting and the impact the intervention had on their overall care skills during the workday. The questionnaire was anonymous and used eight open-ended questions; including for example “Is there anything that you would like to change if this was to become part of staff training”?

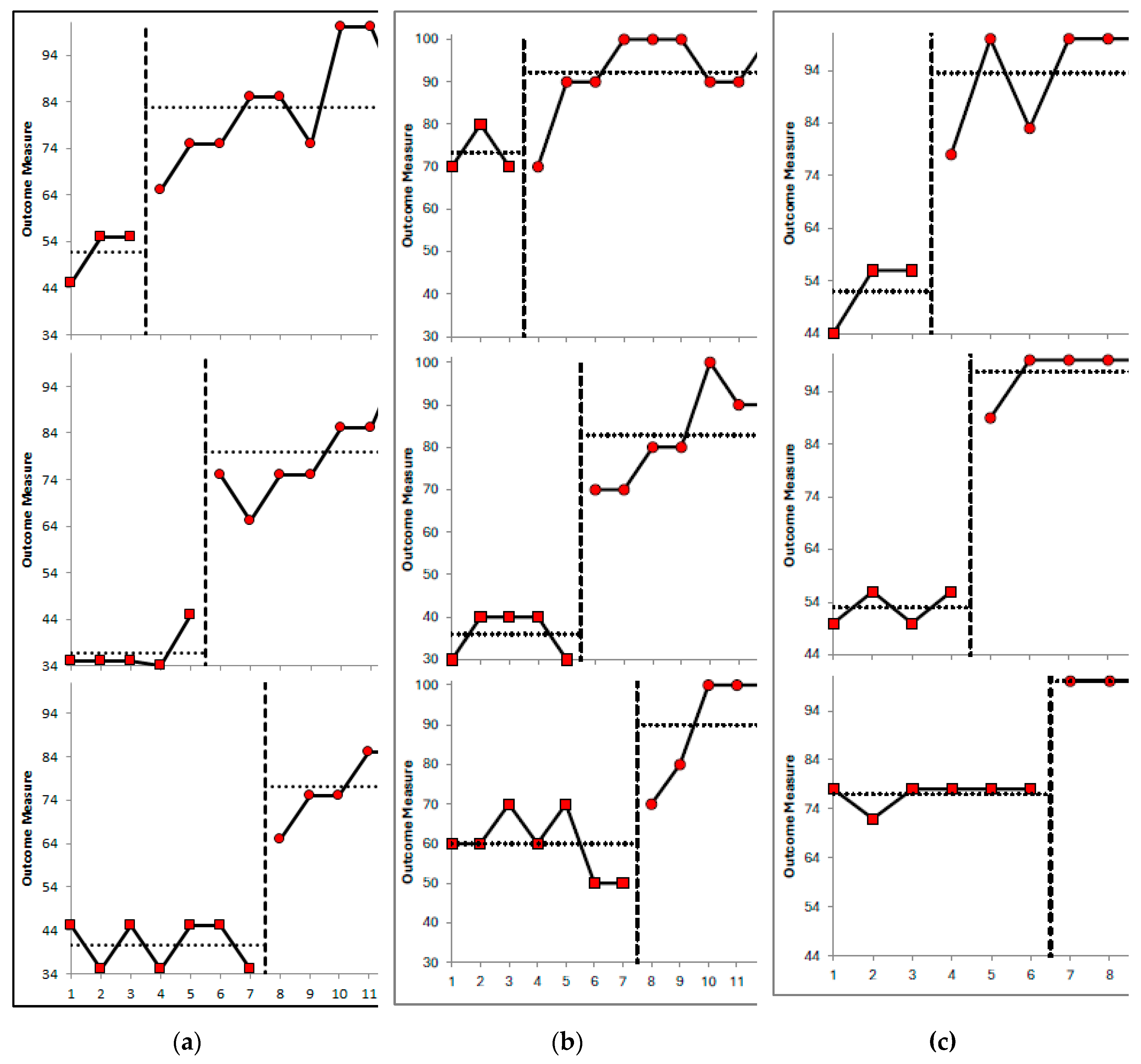

2.6. Analytic Approach

Visual analysis was used to assess the effects of the independent variable (IV) on the DV to determine if a functional relationship exists. Within and between condition analyses examined the trend, level and stability of the data (Lane & Gast, 2014). A stability envelope was used to assess stability: the stability criterion was 80% of the data points falling on or within +/- 25% of the median value at baseline, with the same envelope applied for the intervention phase (see Lane & Gast, 2014). Parallel lines were drawn above and below the median line and the distance between the two lines demonstrates the amount of variability permitted for the data to be considered stable (Gast, 2010; Lane & Gast, 2014). The percentage of non-overlapping data was calculated by taking the number of intervention points that are greater than the highest baseline data point and dividing this by the total number of intervention points and multiplying by 100 (Scruggs & Mastropieri, 1998).

Manolov & Moeyaert (2017) suggested that quantitative analysis can be helpful in complementing visual analysis. Similarly, Levin et al. (2019) state that visual analysis should take precedent with statistical analysis subsequently conducted to demonstrate probabilistically based conclusions and effect-size estimates. Statistical analysis was conducted using the Excel Package of Randomization Tests (ExPRT) programme (Gafurov & Levin, 2021). A summary across-cases effect-size (d) measure was calculated, which was the simple average of the individual case ds.

3. Results

3.1. Visual Analysis

3.1.1. ADL1: Assistance to Stand

Within Condition Analysis. Evaluation of relative and absolute level change within conditions indicated performance was improving during baseline and intervention for P3 (+10 and +10 respectively at baseline; +17.5 and +35 respectively at intervention) and P1 (+5.5 and +11 at baseline; +10 and +25 at intervention) and deteriorating during baseline and improving during intervention for P2 (0 and -10 at baseline; +10 and +20 at intervention). The split middle method of trend estimation showed an increasing therapeutic trend during baseline and intervention for P3 and P1, and a level trend at baseline and increasing therapeutic trend during intervention for P2. A stability envelope was applied to trend lines and showed that the data were stable at baseline for P3 but variable at intervention, while data were stable at both phases for P1 and P2. P3s mean accuracy scores increased from 51.67% in baseline (range 55% - 45%) to 83.33% (range 100% - 65%) at intervention, and maintenance was 100%. P1s mean accuracy scores increased from 36.8% (range 45% - 35%) at baseline to 80% (range 100% - 65%) at intervention, and maintenance was 100%. P2s mean accuracy scores increased from 40.71% (range 45% - 35%) at baseline to 82% (range 85% - 65%) at intervention, and maintenance was 75%.

Between Condition Analysis. Evaluation of behaviour change between conditions indicated improvements for the intervention relative to baseline for all three participants. For P2, a change in performance across conditions went from a level, deteriorating trend at baseline to an accelerating, improving trend at intervention. For P3 and P1, performance was accelerating and improving across both conditions. All level change measures indicated positive improving behaviour change across conditions for all participants. The relative level change, absolute level change, mean level change, and median level change were calculated to demonstrate between condition effects: P3 scores were +20, +10, +30, and +31.13 respectively. P1 scores were +34.5, +30, +40, and +43.2 respectively. P2 scores were +26, +30, +30, and +36.29 respectively.

Figure 1 provides a visual display of the data. No overlapping data (

Table 2) is present for any participants for ADL1 (PND = 100%), indicating that the intervention was very effective (Scruggs & Mastropieri, 1998).

3.1.2. ADL2: Assistance with Drinking

Within Condition Analysis. Evaluation of relative and absolute level change within conditions indicated that performance was level during baseline and improving during intervention for P1 (0 and 0 respectively at baseline; +10 and +30 respectively at intervention) and P3 (0 and 0 at baseline; +20 and +20 at intervention), and performance was deteriorating during baseline and improving during intervention for P2 (-10 and -10 at baseline; +25 and +30 at intervention). The split middle method of trend estimation indicated that there was a level, stable trend during baseline and an accelerating therapeutic trend during intervention for P1 and P3, and a decelerating contra-therapeutic trend at baseline and increasing therapeutic trend during intervention for P2. A stability envelope was applied to trend lines and showed that the data were stable at baseline and intervention for all three participants. P1s mean accuracy scores increased from 73.33% in baseline (range 70% -80%) to 92.22% (range 90% - 100%) at intervention, and maintenance was 90%. P3s mean accuracy scores increased from 36% (range 30% - 40%) at baseline to 82.86% (range 70% - 100%) at intervention, and maintenance was 100%. P2s mean accuracy scores increased from 60% (range 50% - 70%) at baseline to 90% (range 70% - 100%) at intervention, and maintenance was 90%.

Between Condition Analysis. Evaluation of behaviour change between conditions indicated improvements for the intervention relative to baseline for all three participants. For P1 and P3, a change in performance across conditions went from a stable, level trend at baseline to an accelerating, improving trend at intervention. For P2, performance went from a decelerating, deteriorating trend at baseline to an accelerating, improving trend at intervention. The relative level change, absolute level change, mean level change, and median level change were calculated to demonstrate between condition effects: P1 scores were +20, 0, +20, and +18.89 respectively. P3 scores were +35, +40, +40, and +46.86 respectively. P2 scores were +25, +20, +40, and +30 respectively. See

Figure 1. P1 had one overlapping data point (PND = 88.8%), P3 had no overlapping data points (PND = 100%), and P2 had one overlapping data point (PND = 80%). The PND scores indicate that the intervention was very effective (

Table 2).

3.1.3. ADL3: Assistance to Brush Teeth

Within Condition Analysis. Evaluation of relative and absolute level change within conditions indicated that performance was accelerating and improving during baseline and intervention for P3 (+12 and +12 respectively at baseline; +17 and +22 respectively at intervention); level and improving at baseline and accelerating and improving at intervention for P2 (0 and +6 at baseline; +5.5 and +11 at intervention); and level and stable at baseline and intervention for P3 (relative and absolute level change was zero within each condition). The split middle method of trend estimation indicated that there was an accelerating therapeutic trend at baseline and intervention for P3; a level therapeutic trend during baseline and an accelerating therapeutic trend during intervention for P2; and a level trend at baseline and intervention for P1. A stability envelope was applied to trend lines and showed that the data were stable at baseline and intervention for all three participants. P3s mean accuracy scores increased from 52% (range 44% - 564%) at baseline to 94% (range 78% - 100%) at intervention, and maintenance was 94%. P2s mean accuracy scores increased from 53% (range 56% - 60%) at baseline to 98% (range 100% - 89%) at intervention, and maintenance was 100%. P1s mean accuracy scores increased from 77% (range 72% - 78%) at baseline to 100% (range 100% - 100%) at intervention, and maintenance was 89%.

Between Condition Analysis. Evaluation of behaviour change between conditions indicated better performance during the intervention phase relative to baseline for all three participants. For P3, data were accelerating and improving at baseline and intervention phases. For P2, a change in performance across conditions went from a level, improving trend at baseline to an accelerating, improving trend at intervention. For P1, data were level with a stable trend at both baseline and intervention. The relative level change, absolute level change, mean level change, and median level change were calculated to demonstrate between condition effects: P3 scores were +27, +22, +44, and +41.5 respectively. P2 scores were +41.5, +33, +47, and +44.8 respectively. P1 scores were +22, +22, +22, and +23 respectively. See

Figure 1. All participants had no overlapping data for ADL3 (PND = 100%), suggesting that the intervention was very effective.

3.2. Statistical Analysis

Within the ExPRT package, the Wampold-Worsham model (within-case comparison) procedure was selected. Each case was assigned to a single predetermined intervention start point, and the cases were randomly assigned to stagger positions within the multiple-baseline design (see Gufarov & Levin, 2023). Outputs from ExPRT included summary data (as seen in

Figure 1) including plotted data, individual case means and standard deviations, and effect sizes. We intended to include

p-values for A-to-B phase mean differences, but the study was statistically underpowered and unable to produce conventional

p-values. Instead, we report the across-cases mean B-A difference (raw score), and a summary across-cases d measure, which is the simple average of the individual case ds (i.e., average standardised effect size). Parker and Vannest’s (2009) NAP index, is also reported for each case. NAP indicates the proportion of A- and B-phase observation outcomes that are non-overlapping. ExPRT’s individual case NAP indices are rescaled from Parker and Vannest’s original NAP measure (NAPPV), which ranges from .50 to 1.00, so that the rescaled NAP measure (NAPR) ranges from .00 to 1.00.

For behaviour 1 (assistance to stand), across-cases mean B-A difference was 36.86 raw-score units. The average effect size was d = 5.85 (i.e., the average mean increase between Phase A and Phase B amounted to almost six A-phase standard deviations). The average effect size of NAP was 1.00. For behaviour 2 (assistance with drinking), across-cases mean B-A difference was 31.92 raw-score units, the average effect size was d=5.17, and the average effect size of NAP was 0.932. For behaviour 3 (assistance to brush teeth), across-cases mean B-A difference was 36.43 raw-score units, the average effect size was d= 9.44, and the average effect size of NAP was 1.00.

3.3. Interobserver Agreement

Two healthcare staff members (not otherwise involved with the research) were trained to take interobserver agreement (IOA) data. Data were collected simultaneously in different locations in the same room. IOA data was collected once per condition (baseline and intervention) for each participant during the three ADLs. IOA was calculated using exact agreement IOA: the number of exact agreement trials/ the total number of trials x 100. The number of ‘trials’ per ADL depended on the number of steps on the task analysis. Staff used the task analysis data collection sheet to gather this data. The overall average IOA was 94%, with scores ranging from 77.8% to 100%.

3.4. Generalisation

Generalisation probes for assisting an individual with eating were 90% for participant one, 100% for participant two and 90% for participant three. Helping a PLwD put on a jumper was 80% for P1, 90% for P2 and 70% for P3.

3.5. Social Validity

The responses to the social validity questionnaire are displayed in

Table 3. Overall, participants identified an increased awareness of how to promote higher levels of independence and a willingness to use this in activities outside of what was directly taught but also recognised that time was an issue. Participants stated that they would recommend the training to others but mixed results for wanting to engage in the same type of training in the future.

4. Discussion

This study incorporated BST as an intervention to train healthcare staff in a dementia care facility to increase opportunities for independent responding for PLwD during ADLs. Specifically, staff were trained how to use a task analysis to identify the steps in a chain of behaviours required to complete ADLs, and to use L-M prompting procedures to ensure that PLwD were given the opportunity to complete ADLs as independently as possible. The environment was still supportive in that staff were available to guide PLwD as needed, but instead of staff defaulting to completing ADLs for PLwD (e.g. full physical prompting), the staff were encouraged to assume that residents could engage in their ADLs independently, and then only offered graded prompts as needed. The visual within and between condition analysis demonstrated improvements in the intervention phase relative to the baseline phase for the three participants and for each ADL, with level change measures demonstrating relative, absolute, mean, and median improvements between phases. For most participants, there was an abrupt and immediate intervention effect observed with no overlapping data-points; but on ADL2 there was overlapping data for P1 and for P2. Overall, visual analysis of the data suggested positive behaviour change in the expected direction. The visual analysis was supported by statistical data from the ExPRT package of randomisation tests (Levin et al., 2019) which showed positive pre-post intervention changes for each participant across the three ADLs, with effect sizes ranging from 3.97 to 12.93 (average effect size of 7.10).

Maintenance data suggested that the intervention effects were maintained at a 2-week follow-up with scores ranging from 75% to 100%. The percentage of correct responses in generalisation probes ranged from 80% to 100%. The generalisation of the skills learned during training courses is an important consideration for those who provide training to healthcare staff to promote independence for those in their care. In our study, we incorporated the intervention using an MBD across participants, and we repeated this training and testing across three separate ADL's. The advantage of this was to ensure to programme for generalisation, by promoting skill development across multiple exemplars and contexts (Erhard et al., 2022; Hartley & Whiteley, 2024). An examination of the data suggests that training on two to three separate ADL's may be required for staff to be able to generalise this skill to other ADLs. The data varied somewhat across participants, but we can see from P1s data, that in ADL2 and ADL3, there may be learning carryover effects from ADL1 (either that, or the participant was already facilitating independent responding for these ADLs). However, for P2 and P3, repeated exposure to the BST training across three ADL's seemed to be necessary/sufficient in order to promote generalisation to other ADLs. Our findings have implications for those planning staff training, specifically, that training in varied contexts or using different exemplars may be optimal for promoting maintenance and generalisation of the learned skill. This is in line with previous research (Erhard et al., 2022; Hartley & Whiteley, 2024). Future studies should examine specific strategies to ensure maintenance and generalisation of trained skills in healthcare settings.

The strength of a multiple baseline design is that threats to internal validity can be controlled for, and the MBD can determine if a functional (casual) relationship exists between the intervention and outcome (Slocum et al., 2022). A functional relationship is typically inferred if the data (visually) demonstrated experimental control through prediction, replication and verification; specifically, does the intervention produce a change in the outcome variable in a precise and reliable fashion (Byiers et al., 2012). Slocum et al. (2022) explains that in (traditional non-randomised) MBD research, baseline stability is important for prediction; a stable baseline predicts that the data path would continue as observed without the intervention. Verification happens when there is no change in the data trends in other staggered baseline tiers, also not subjected to the intervention, and replication is observed when an intervention effect occurs across multiple tiers (Slocum et al., 2022). However, to achieve case randomisation for a randomized MBD, cases are randomly assigned to predetermined intervention start-points/baseline lengths (Levin et al., 2019). In practical terms, this meant that baseline stability did not determine when our intervention commenced, intervention commencement was pre-determined. The impact of the predetermined baseline lengths can be seen in our data, where there were ascending trends evident during baseline phases for ADLs one and three. In a traditional non-randomised design, researchers would continue to gather baseline data until a stable pattern emerged, but this response-guided approach does not occur with case randomisation and start-point randomisation. Some may consider this a limitation to the current study (e.g., see Kazdin, 1980), however, more recent literature provides important insights into the importance of randomization for reducing/controlling for threats to internal validity (Kratochwill & Levin, 2010; Tanious & Onghena, 2019), removing researcher bias (Levin et al., 2019) and facilitating the use of randomisation statistical tests (Craig & Fisher, 2019). As Hwang et al. (2016) aptly stated, “randomization is the hallmark of scientifically credible intervention research” (p.11). Overall, the benefits of randomization in SCED appear to outweigh the caveats, and SCED researchers should continue to purposefully explore the utility of randomized designs in their work.

Visual analysis of SCED data has been commonplace for over 60 years (Kratochwill & Levin, 2014). More recently, researchers are advocating for the use of statistical analysis to supplement visual outcome data (Hwang & Levin, 2016; Levin et al., 2019). Another advantage of using randomised designs in single-case research is to facilitate the use of appropriate randomisation tests, like those described by Gufarov & Levin (2023). While a strength of our study was the incorporation of randomisation and statistical data, a limitation of our study is the fact that – with only three participants and case randomisation, the study was underpowered and ExPRT was unable to return meaningful p-values for the within-case comparisons. The Wampold-Worsham (1986) model was used in ExPRT as this was deemed appropriate for single fixed intervention start-points in MBD (Gufarov & Levin, 2023; Levin et al., 2019). If, however, we had incorporated start-point randomization between two (or more) possible intervention start-points, the statistical power of the design would have increased. With start-point randomisation, a statistical model like the Koehler-Levin (1998) model could be adopted (Gufarov & Levin, 2023), which is more powerful with respect to detecting immediate abrupt intervention effects (Levin et al., 2018), as seen with our data. Future studies should consider the use of multiple randomisation procedures (see Hwang et al., 2016 for an example) to improve credibility and statistical power. Using both case and start-point randomisation is a good starting point at least.

With a view to further improving the quality of this research, we designed the study in accordance with the recommendations of the WWC guidelines (Kratochwill et al., 2010; 2013). There are four criteria used to determine whether a study design meets design standards, either with or without reservations. First, we systematically manipulated an IV (BST training), which meets design standards. Second, we measured the outcome variable in a systematic manner and calculated IOA data on each case for each outcome variable. IOA data should be calculated for more than 20% of the data points within each condition to fully meet the design standards. For our study, IOA was gathered once per condition, meaning that conditions with up to five data points had sufficient IOA data gathered to meet the design standards, but the IOA gathered for conditions with 6+ data points do not meet the design standards. Third, our study included at least three attempts to demonstrate an intervention effect at different time-points; MBDs like ours, with at least three baseline conditions meet the design standards. A further strength of our study was that we also replicated the MBD across participants for three separate ADLs. Finally, our MBD included a minimum of six phases (at least three A and three B phases) with at least three data points per phase. This aspect of the design meets standards with reservations (to fully meet the design standards, a minimum of five data points per phase was required). While we found the design standards generally achievable, there were some challenges, particularly in taking a minimum of five data points in the first baseline phase (which would mean quite an extended baseline, e.g., for the third baseline phase), and in the availability of staff for gathering IOA data. To gather IOA data for this study, the researcher needed to train other staff members, who were not familiar with task analysis and L-M prompting, to be able to identify ‘correct/incorrect’ responding. The staff did not wish to participate in the research but did attend training to support the researcher with gathering IOA data. While not impossible, this can create tensions and barriers within already busy work environments. More detailed concerns/criticisms of the WWC guidelines have been noted elsewhere (Wolery, 2013). Despite this, the guidelines offer clear and useful information to support researchers to implement standardised approaches and improve overall design quality.

While our research demonstrates that training can transform staff behaviour to support PLwD to reach their potential functioning, the contingencies that maintain staff behaviour of disempowerment require consideration. The literature is clear that creating opportunities for independent engagement is for PLwD is crucial (Yates et al., 2019), yet care settings often that do not provide those opportunities (den Ouden et al., 2015; Tak et al., 2015). The creation of dependency for PLwD can directly result from a cycle of positive reinforcement on the healthcare worker created by the workplace environment. Healthcare staff who complete high volumes of tasks in short time frames can receive praise from management and be perceived as hard-working. Those who take longer may receive positive punishment, decreasing their actions to promote independence as this requires more time with the PLwD (Buchanan et al., 2011). If independence levels of the PLwD are contingent on staff delivery of the activity, and staff delivery of the activity is contingent on the reinforcing and punishing agents within the work environment, it is essential to examine where the responsibility of promoting quality care lies (Megan Josling, 2015). A strong link exists between the maintained outcomes in behavioural gerontology and organisational behavioural management (Megan Josling, 2015).

Due to the nature of the respite centre and the high number of admission/discharges of residents, participants implemented the intervention with different PLwD. No data was recorded on the impact of the prompting procedure on the PLwD and whether their independence increased over time. Due to the project’s duration, time restrictions were a limitation; longer maintenance phases would give better data on skill maintenance. The possibility of observer reactivity of care staff proves to be a limitation which may be addressed where onsite cameras are in place or with video observations. A strength of the current study is the randomised design. Although some disagree about the necessity for randomisation within SCDs (Levin et al., 2019), particularly where more traditional behavioural studies may only begin an intervention on a stable baseline (as discussed above), others suggest that if SCDs are to be comparable to RCTs as Level 1 evidence, randomisation is required to reduce threats to internal validity and improve causal inference (Kratochwill et al., 2013; Kratochwill & Levin, 2010; Levin et al., 2019).

5. Conclusions

Creating environments that support activity engagement and independence in ADLs has important implications for reducing excess disability for PLwD and encouraging a rights-based approach in line with the UNCRPD. This research adds important insights into how staff can create more independent environments for those PLwD in their care. We suggest that training on task breakdown (task analysis), task presentation and L-M prompting should be part of staff continuous education, and this should ideally be followed with supervision and positive feedback to increase staff implementation of supportive practices into their work. BST may be more socially valid for staff if it is part of their training and work routine, and if it is supplemented with supportive feedback. BST could also be used to teach other important skills relevant for positive dementia care environments, such as training staff to conduct functional assessments of behavioural symptoms of dementia (Moniz-Cook et al., 2012). Future research should gather data on the responses and feedback of PLwD where BST is used to train healthcare staff to support increased opportunities for independence. It would also be interesting to examine the effects of increased independence on behaviours such as refusal during personal care. Time and workload requirements for care staff may pose barriers to supportive intervention implementation (Baker et al., 2015); ensuring staff are afforded the time and space to support PLwD to be independent is crucial. In future research, social validity should focus on feedback from PLwD on the impact that staff training has on their lived experience. Social validity could also focus on staff experience of BST training and compare BST to other traditional training approaches. Openness to learning ‘new’ ways of doing things may require a review of values and values actions within the health care environment.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at:

www.mdpi.com/xxx/s1, Table S1-S3: complete visual analysis data.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.H. and M.K.; methodology, M.K. and J.H.; software, M.K.; validation, J.H. and M.K.; formal analysis, M.K. and J.H.; investigation, J.H.; resources, J.H. and M.K.; data curation, J.H.; writing—original draft preparation, J.H. and M.K.; writing—review and editing, M.K.; supervision, M.K.; project administration, J.H. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Institutional Review Board (or Ethics Committee) of the University of Galway, Galway, Ireland (application number code XXX and date of approval).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

We wish to thank the residents, staff and management in the respite center where this research was completed.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| PLwD |

Person Living with Dementia |

| ADL |

Activity of Daily Living |

| BST |

Behavioural Skills Training |

| L-M |

Least to most |

| WWC |

What Works Clearing House |

| MBD |

Multiple baseline design |

| IV |

Independent variable |

| DV |

Dependent variable |

| UNCRPD |

United Nations Convention on the Rights of People with Disabilities |

| SD |

Discriminative stimulus |

| QoL |

Quality of life |

| SCED |

Single case experimental design |

| SCRIBE |

Single-Case Reporting Guideline in BEhavioural Interventions |

| FETAC |

Further Education and Training Awards Council |

| ExPRT |

Excel Package of Randomization Tests |

| PND |

Percentage of non-overlapping data |

| P1 |

Participant one |

| P2 |

Participant two |

| P3 |

Participant three |

References

- Aggio, N. M. , Ducatti, M., & de Rose, J. C. (2018). Cognition and Language in Dementia Patients: Contributions from Behavior Analysis. In Behavioral Interventions (Vol. 33, Issue 3, pp. 322–335). John Wiley and Sons Ltd. [CrossRef]

- Alaimo, C. , Seiverling, L., Sarubbi, J., & Sturmey, P. (2018). The Effects of a Behavioral Skills Training and General-Case Training Package on Caregiver Implementation of a Food Selectivity Intervention. Behavioral Interventions, 33(1), 26–40. [CrossRef]

- Aylward, S. , Stolee, P., Keat, N., & Johncox, V. (2003). Effectiveness of Continuing Education in Long-Term Care: A Literature Review. The Gerontologist, 43(2), 259–271. [CrossRef]

- Baker, J. C. , Fairchild, K. M., & Seefeldt, D. A. (2015). Behavioral Gerontology: Research and Clinical Considerations. In Clinical and Organisational Applications of Applied Behavior Analysis (pp. 425–450). Elsevier. [CrossRef]

- Baltes, M. M. , & Wahl, H. W. (1996). Patterns of Communication in Old Age: The Dependence-Support and Independence-Ignore Script. Health Communication, 8(3), 217–231. [CrossRef]

- Brenske, S., Rudrud, E. H., Schulze, K. A., & Rapp, J. T. (2008). Increasing Activity Attendance and Engagement in Individuals with Dementia Using Descriptive Prompts. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 41(2), 273–277. [CrossRef]

- Brown, R. T. , Diaz-Ramirez, L. G., Boscardin, W. J., Lee, S. J., Williams, B. A., & Steinman, M. A. (2019). Association of Functional Impairment in Middle Age with Hospitalization, Nursing Home Admission, and Death. JAMA Internal Medicine, 179(5), 668. [CrossRef]

- Buchanan, A. J., Christenson, A., Houlihan, D., & Ostrom, C. (2011). The Role of Behavior Analysis in the Rehabilitation of Persons with Dementia. Behavior Therapy, 42, 9–21. [CrossRef]

- Buchanan, A. J., DeJager, B., Garcia, S., Houlihan, D., Sears, C., Fairchild, K., & Sattler, A. (2018). The Relationship Between Instruction Specificity and Resistiveness to Care During Activities of Daily Living in Persons with Dementia. Clinical Nursing Studies, 6(4), 45. [CrossRef]

- Buchanan, J. , Husfeldt, J., Berg, T., & Houlihan, D. (2008). Publication Trends in Behavioral Gerontology in the Past 25 Years: Are the Elderly Still an Understudied Population in Behavioral Research? Behavioral Interventions, 23(1), 65–74. [CrossRef]

- Burgio, L. D., Engel, B. T., Hawkins, A., McCormick, K., Scheve, A., & Jones, L. T. (1990). A Staff Management System for Maintaining Improvements in Continence with Elderly Nursing Home Residents. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 23(1), 111–118. [CrossRef]

- Burgio, L. D. Burgio, L. D., Stevens, A., Burgio, K. L., Roth, D. L., Paul, P., & Gerstle, J. (2002). Teaching and Maintaining Behavior Management Skills in the Nursing Home. The Gerontologist, 42(4), 487–496. [CrossRef]

- Cipriani, G. , Danti, S., Picchi, L., Nuti, A., & Fiorino, M. Di. (2020). Daily Functioning and Dementia. Dementia & Neuropsychologia, 14(2), 93–102. [CrossRef]

- Cooper, J. O. , Heron, T. E., & Willian, H. L. (2020). Applied Behavior Analysis (3rd ed.). Pearson Education Limited.

- Courtemanche, A. B. , Turner, L. B., Molteni, J. D., & Groskreutz, N. C. (2021). Scaling Up Behavioral Skills Training: Effectiveness of Large-Scale and Multiskill Trainings. Behavior Analysis in Practice, 14(1), 50. [CrossRef]

- Coyne, M. L., & Hoskins, L. (1997). Improving Eating Behaviors in Dementia Using Behavioral Strategies. Clinical Nursing Research, 6(3), 275–290. [CrossRef]

- Craig, A. R. , & Fisher, W. W. (2019). Randomization tests as alternative analysis methods for behavior-analytic data. Journal of the Experimental Analysis of Behavior, 111(2), 309–328. [CrossRef]

- Dallery, J. , & Raiff, B. R. (2014). Optimising Behavioral Health Interventions with Single-Case Designs: From Development to Dissemination. Translational Behavioral Medicine, 4(3), 290–303. [CrossRef]

- Engelman, K. K., Altus, D. E., & Mathews, R. M. (1999). Increasing Engagement in Daily Activities by Older Adults with Dementia. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 32(1), 107–110. [CrossRef]

- Engelman, K. K., Altus, D. E., Mosier, M. C., & Mathews, R. M. (2003). Brief Training to Promote the Use of Less Intrusive Prompts by Nursing Assistants in a Dementia Care Unit. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 36(1), 129–132. [CrossRef]

- Engstrom, E. , Mudford, O. C., & Brand, D. (2015). Replication and Extension of a Check-in Procedure to Increase Activity Engagement Among People with Severe Dementia. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 48(2), 460–465. [CrossRef]

- Erhard, P. , Falcomata, T. S., Oshinski, M., & Sekula, A. (2022). The effects of multiple-exemplar training on generalization of social skills with adolescents and young adults with autism: A systematic review. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 11(1). [CrossRef]

- Fisher, J. E. , Drossel, C., Yury, C., & Cherup, S. (2007). A Contextual Model of Restraint-Free Care for Persons with Dementia. In Functional Analysis in Clinical Treatment (pp. 211–237). Elsevier. [CrossRef]

- Gardner, J. M. (1972). Teaching Behavior Modification to Nonprofessionals. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 5(4), 517–521. [CrossRef]

- Gitlin, L. N. , Winter, L., Burke, J., Chernett, N., Dennis, M. P., & Hauck, W. W. (2008). Tailored Activities to Manage Neuropsychiatric Behaviors in Persons With Dementia and Reduce Caregiver Burden: A Randomised Pilot Study. The American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 16(3), 229–239. [CrossRef]

- Gormley, L. , Healy, O., O’Sullivan, B., O’Regan, D., Grey, I., & Bracken, M. (2019). The Impact of Behavioural Skills Training on The Knowledge, Skills and Well-Being of Front Line Staff in the Intellectual Disability Sector: A Clustered Randomised Control Trial. Journal of Intellectual Disability Research, 63(11), 1291–1304. [CrossRef]

- Gafurov, B. S. , & Levin, J. R. (2021). ExPRT (Excel Package of Randomization Tests): Statistical analyses of single-case intervention data (Version 4.2) [Computer software]. Retrieved from http://ex-prt.weebly.com.

- Han, A. , Radel, J., McDowd, J. M., & Sabata, D. (2016). Perspectives of People with Dementia About Meaningful Activities. American Journal of Alzheimer’s Disease & Other Dementias, 31(2), 115–123. [CrossRef]

- Han, S. S. , White, K., & Cisek, E. (2022). A Feasibility Study of Individuals Living at Home with Alzheimer’s Disease and Related Dementias: Utilisation of Visual Mapping Assistive Technology to Enhance Quality of Life and Reduce Caregiver Burden. Clinical Interventions in Aging, Volume 17, 1885–1892. [CrossRef]

- Hartley, C. , & Whiteley, H. A. (2024). Do multiple exemplars promote preschool children’s retention and generalisation of words learned from pictures? Cognitive Development, 70, 101459. [CrossRef]

- Health Information and Quality Authority. (2016). National Standards for Residential Care Settings for Older People in Ireland. https://www.hiqa.ie/sites/default/files/201701/National-Standards-for-Older-People.pdf.

- Horner, R. H. , Carr, E. G., Halle, J., McGee, G., Odom, S., & Wolery, M. (2005). The Use of Single-Subject Research to Identify Evidence-Based Practice in Special Educatio. Exceptional Children, 71(2), 165–179.

- Howick, J. , Chalmers, I., Glasziou, P., Greenhalgh, T., Heneghan, C., Liberati, A., Moschetti, I., Phillips, B., Thornton, H., Goddard, O., & Hodgkinson, M. (2011). Oxford Centre for Evidence-Based Medicine 2011 Levels of Evidence.

- Hwang, Y., Levin, J. R., & Johnson, E. W. (2016). Pictorial mnemonic-strategy interventions for children with special needs: Illustration of a multiply randomized single-case crossover design. Developmental Neurorehabilitation, 21(4), 223–237. [CrossRef]

- Jahr, E. (1998). Current Issues in Staff Training. Research in Developmental Disabilities, 19(1), 73–87. [CrossRef]

- Karr, J. E. , Graham, R. B., Hofer, S. M., & Muniz-Terrera, G. (2018). When Does Cognitive Decline Begin? A systematic Review of Change Point Studies on Accelerated Decline in Cognitive and Neurological Outcomes Preceding Mild Cognitive Impairment, Dementia, and Death. Psychology and Aging, 33(2), 195–218. [CrossRef]

- Kelly, M. E. , Lawlor, B. A., Coen, R. F., Robertson, I. H., & Brennan, S. (2019). Cognitive Rehabilitation for Early Stage Alzheimer’s Disease: A Pilot Study with an Irish Population. Irish Journal of Psychological Medicine, 36(2), 105–119. [CrossRef]

- Kimberly, K. Engelman. (1999). Using Graduated Prompts to Increase Dressing Independence by Older Adults with Dementia. Thesis.

- Koehler, M. J. , & Levin, J. R. (1998). Regulated randomization: A potentially sharper analytical tool for the multiple-baseline design. Psychological Methods, 3(2), 206–217. [CrossRef]

- Kratochwill, T. R. , Hitchcock, J. H., Horner, R. H., Levin, J. R., Odom, S. L., Rindskopf, D. M., & Shadish, W. R. (2013). Single-Case Intervention Research Design Standards. Remedial and Special Education, 34(1), 26–38.

- Kratochwill, T. R. , Hitchcock, J., Horner, R. H., Levin, J. R., Odom, S. L., Rindskopf, D. M., & Shadish, W. R. (2010). Single-Case Designs Technical Documentation. http://ies.ed.gov/ncee/wwc/pdf/wwc_scd.pdf.

- Kratochwill, T. R. , & Levin, J. R. (2010). Enhancing the Scientific Credibility of Single-Case Intervention Research: Randomization to the Rescue. Psychological Methods, 15(2), 124–144. [CrossRef]

- Lancioni, G. E. , Singh, N. N., O’reilly, M. F., Sigafoos, J., Bosco, A., Zonno, N., & Badagliacca, F. (2011). Persons with Mild or Moderate Alzheimer’s Disease Learn to Use Urine Alarms and Prompts to Avoid Large Urinary Accidents. Research in Developmental Disabilities, 32, 1990–2004. [CrossRef]

- Laver, K. , Piersol, C. V., & Wiley, R. (2021). Optimising Independence in Activities of Daily Living. In Dementia Rehabilitation: Evidence-Based Interventions and Clinical Recommendations (pp. 81–96). Elsevier. [CrossRef]

- Lerman, D. C. , LeBlanc, L. A., & Valentino, A. L. (2015). Evidence-Based Application of Staff and Caregiver Training Procedures. In Clinical and Organisational Applications of Applied Behavior Analysis (pp. 321–351). Elsevier. [CrossRef]

- Levin, J. R. , Ferron, J. M., & Gafurov, B. S. (2018). Comparison of randomization-test procedures for single-case multiple-baseline designs. Developmental Neurorehabilitation, 21(5), 290-311. [CrossRef]

- Levin, J. R. , & Kratochwill, T. R. (2021). Randomised Single-Case Intervention Designs and Analyses for Health Sciences Researchers: A Versatile Clinical Trials Companion. Therapeutic Innovation & Regulatory Science, 55, 755–764. [CrossRef]

- Levin, J. R. , Kratochwill, T. R., & Ferron, J. M. (2019). Randomization Procedures in Single-Case Intervention Research Contexts: (Some of) “The Rest of the Story.” Journal of the Experimental Analysis of Behavior, 112(3), 334–348. [CrossRef]

- Libby, M., Weiss, Julie. S., Bancroft, S., & Ahearn, W. H. (2008). A Comparison of Most-to-Least and Least-to-Most Prompting on the Acquisition of Solitary Play Skills. Behavior Analysis in Practice, 1(1), 37–43. https://europepmc.org/backend/ptpmcrender.fcgi?accid=PMC2846579&blobtype=pdf.

- Lichtenstein, M. J. , Federspiel, C. F., & Schaffner, W. (1985). Factors Associated with Early Demise in Nursing Home Residents: A Case Control Study. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, 33(5), 315–319. [CrossRef]

- Manolov, R. , & Moeyaert, M. (2017). How Can Single-Case Data Be Analysed? Software Resources, Tutorial, and Reflections on Analysis. Behavior Modification, 41(2), 179–228. [CrossRef]

- McCurry, Susan., & Drossel, Claudia. (2011). Treating Dementia in Context: A Step-by-Step Guide to Working with Individuals and Families. American Psychological Association. https://www.apa.org/pubs/books/4317254.

- McGowan, B. , Gibb, M., Cullen, K., & Craig, C. (2019). Non-Cognitive Symptoms of Dementia (NCSD): Guidance on Non-pharmacological Interventions for Healthcare and Social Care Practitioners. https://dementia.ie/wp-content/uploads/2020/01/Non-cognitive_Symptoms_of_Dementia1.pdf.

- Megan Josling. (2015). A Review of Behavioural Gerontology and Dementia Related Interventions. Studies in Arts and Humanities, 1(5), 39–51. [CrossRef]

- Millá N-Calenti, J. C. , Tubío, J., Pita-Ferná Ndez, S., Gonzá Lez-Abraldes, I., Lorenzo, T., Ferná Ndez-Arruty, T., & Maseda, A. (2010). Prevalence of Functional Disability in Activities of Daily Living (ADL), Instrumental Activities of Daily Living (IADL) and Associated Factors, as Predictors of Morbidity and Mortality. Archives of Gerontology and Geriatrics, 50, 306–310. [CrossRef]

- Miltenberger, R. G. (2016). Behavior Modification: Principles and Procedures. In Behavior Modification : Principles and Procedures (6th ed.). Cengage Learning.

- Mlinac, M. E. , & Feng, M. C. (2016). Assessment of Activities of Daily Living, Self-Care, and Independence. Archives of Clinical Neuropsychology, 31(6), 506–516. [CrossRef]

- Namazi, K. H. , & Johnson, B. D. (1991). Environmental Effects on Incontinence Problems in Alzheimer’s Disease Patients. American Journal of Alzheimer’s Care and Related Disorders & Research, 6(6), 16–21. [CrossRef]

- Orth, J. , Li, Y., Simning, A., & Temkin-Greener, H. (2019). Providing Behavioral Health Services in Nursing Homes Is Difficult: Findings From a National Survey. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, 67(8), 1713–1717. [CrossRef]

- Ouslander, J. G. (1995). Predictors of Successful Prompted Voiding Among Incontinent Nursing Home Residents. JAMA: The Journal of the American Medical Association, 273(17), 1366. [CrossRef]

- Palmen, A. , Didden, R., Korzilius, H., & Kannerhuis, L. (2010). Effectiveness of Behavioral Skills Training on Staff Performance in a Job Training Setting for High-Functioning Adolescents with Autism Spectrum Disorders. Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders, 4, 731–740. [CrossRef]

- Parsons, M. B. , Rollyson, J. H., & Reid, D. H. (2012). Evidence-Based Staff Training: A Guide for Practitioners. Behavior Analysis in Practicee, 5(2), 2–11. [CrossRef]

- Pierce, M. , Cahill, S., & O’Shea, E. (2013). Planning Dementia Services: New Estimates of Current and Future Prevalence Rates of Dementia for Ireland. Irish Journal of Psychological Medicine, 30(1), 13–20. [CrossRef]

- Pierse, T., O’ Shea, E., & Carney, P. (2019). Estimates of the Prevalence, Incidence and Severity of Dementia in Ireland. Irish Journal of Psychological Medicine, 36(2), 129–137. [CrossRef]

- Prizer, L. P. , & Zimmerman, S. (2018). Progressive Support for Activities of Daily Living for Persons Living With Dementia. The Gerontologist, 58(suppl_1), S74–S87. [CrossRef]

- Reid, D. H. , O’Kane, N. P., & Macurik, K. M. (2011). Staff Training and Management. In W. W. Fisher, C. C. Piazza, & H. S. Roane (Eds.), Handbook of Applied Behavior Analysis (2nd ed., pp. 281–294). The Guilford Press.

- Reid, D. H. , Parsons, M. B., & Green, C. W. (2021). The Supervisor’s Guidebook: Evidence-Based Strategies for Promoting Work Quality and Enjoyment Among Human Service Staff (2nd ed.). Charles C Thomas Pub Ltd. Kindle Edition.

- Rogers, J. C., Holm, M. B., Burgio, L. D., Hsu, C., Hardin, J. M., & Mcdowell, B. J. (2000). Excess Disability During Morning Care in Nursing Home Residents With Dementia. International Psychogeriatrics, 12(2), 267–282. [CrossRef]

- Sarokoff, R. A. , & Sturmey, P. (2004). The Effects of Behavioral Skills Training on Staff Implementation of Discrete-Trial Teaching. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 37(4), 535–538. [CrossRef]

- Sawyer, M. R. , Andzik, N. R., Kranak, M. P., Willke, C. P., Curiel, E. S. L., Hensley, L. E., & Neef, N. A. (2017). Improving Pre-Service Teachers’ Performance Skills Through Behavioral Skills Training. Behaviour Skills Training, 10, 296–300. [CrossRef]

- Schmidt, A. L. (2016). Using Behavior Skills Training to Teach Effective Conversation Skills to Individuals with Disabilities. MSU Graduate Theses. https://bearworks.missouristate.edu/theses/3044.

- Scruggs, T. E. , & Mastropieri, M. A. (1998). Summarising Single-Subject Research. Behavior Modification, 22(3), 221–242. [CrossRef]

- Shadish, W. R. (2014). Analysis and Meta-analysis of Single-Case Designs: An Introduction. Journal of School Psychology, 52(2), 109–122. [CrossRef]

- Sherman, J., Richardson, J., & Vedora, J. (2021). The Use of Behavioral Skills Training to Teach Components of Direct Instruction. Behavior Analysis in Practice, 14, 1085–1091.

- Skinner, B. F. (1983). Intellectual Self-Management in Old Age. American Psychologist, 239–244. [CrossRef]

- Slane, M. , & Lieberman-Betz, R. G. (2021). Using Behavioral Skills Training to Teach Implementation of Behavioral Interventions to Teachers and Other Professionals: A Systematic Review. Behavioral Interventions, 36(4), 984–1002. [CrossRef]

- Slaughter, S. E. , Eliasziw, M., Morgan, D., & Drummond, N. (2011). Incidence and Predictors of Excess Disability in Walking Among Nursing Home Residents with Middle-Stage Dementia: A Prospective Cohort Study. International Psychogeriatrics, 23(1), 54–64. [CrossRef]

- Tak, E. , Kuiper, R., Chorus, A., & Hopman-Rock, M. (2015). Prevention of onset and progression of basic ADL disability by physical activity in community-dwelling older adults: A meta-analysis. Ageing Research Reviews, 24, 166-177. [CrossRef]

- Tanious, R. , Onghena, P. (2019). Randomized Single-Case Experimental Designs in Healthcare Research: What, Why, and How? Healthcare. 2019; 7(4):143. [CrossRef]

- Tate, R. L. , Perdices, M., Rosenkoetter, U., Shadish, W., Vohra, S., Barlow, D. H., Horner, R., Kazdin, A., Kratochwill, T., Mcdonald, S., Sampson, M., Shamseer, L., Togher, L., Albin, R., Backman, C., Douglas, J., Evans, J. J., Gast, D., Manolov, R., … Barlow, D. H. (2016). The Single-Case Reporting Guideline In BEhavioural Interventions (SCRIBE) 2016 Statement. Physical Therapy, 96(7), 1. [CrossRef]

- Tate, R. L. , Perdices, M., Rosenkoetter, U., Wakim, D., Godbee, K., Togher, L., & Mcdonald, S. (2013). Revision of a Method Quality Rating Scale for Single-Case Experimental Designs and n-of-1 Trials: The 15-Item Risk of Bias in N-of-1 Trials (RoBiNT) Scale. Neuropsychological Rehabilitation An International Journal, 23(5), 619–638. [CrossRef]

- The World Health Organisation. (2023). Dementia: Key Facts. https://www.who.

- Trahan, M. A. , Donaldson, J. M., Mcnabney, M. K., & Kahng, S. (2014). Training and Maintenance of a Picture-Based Communication Response. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 47, 404–409.

- Trahan, M. A. , Fisher, A. B., & Hausman, N. L. (2011). Behavior-Analytic Research on Dementia in Older Adults. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 44, 687–691. [CrossRef]

- Trahan, M. A. , Kuo, J., Carlson, M. C., & Gitlin, L. N. (2014). A Systematic Review of Strategies to Foster Activity Engagement in Persons With Dementia. Health Education & Behavior, 41(1_suppl), 70S-83S. [CrossRef]

- Wolery, M. (2013). A commentary: Single-case design technical document of the What Works Clearinghouse. Remedial and Special Education, 34(1), 39–43. [CrossRef]

- Wolery, M. , Griffen, A. K., Jones Ault, M., Gast, D. L., & Munson Doyle, P. (1990). Comparison of Constant Time Delay and the System of Least Prompts in Teaching Chained Tasks. Education and Training in Mental Retardation, 25(3), 243–257. https://about.jstor.org/terms.

- Wampold, B. , & Worsham, N. (1986). Randomization tests for multiple-baseline designs. Behavioral Assessment, 8, 135-143.

- Yates, L. , Csipke, E., Moniz-Cook, E., Leung, P., Walton, H., Charlesworth, G., Spector, A., Hogervorst, E., Mountain, G., & Orrell, M. (2019). The development of the Promoting Independence in Dementia (PRIDE) intervention to enhance independence in dementia. Clinical Interventions in Aging, 14, 1615-1630. [CrossRef]

- Zanetti, O. , Zanieri, G., Giovanni, G. Di, De Vreese, L. P., Pezzini, A., Metitieri, T., & Trabucchi, M. (2001). Effectiveness of Procedural Memory Stimulation in Mild Alzheimer’s Disease Patients: A Controlled Study. Neuropsychological Rehabilitation, 11(3–4), 263–272. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).