Submitted:

09 April 2025

Posted:

09 April 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

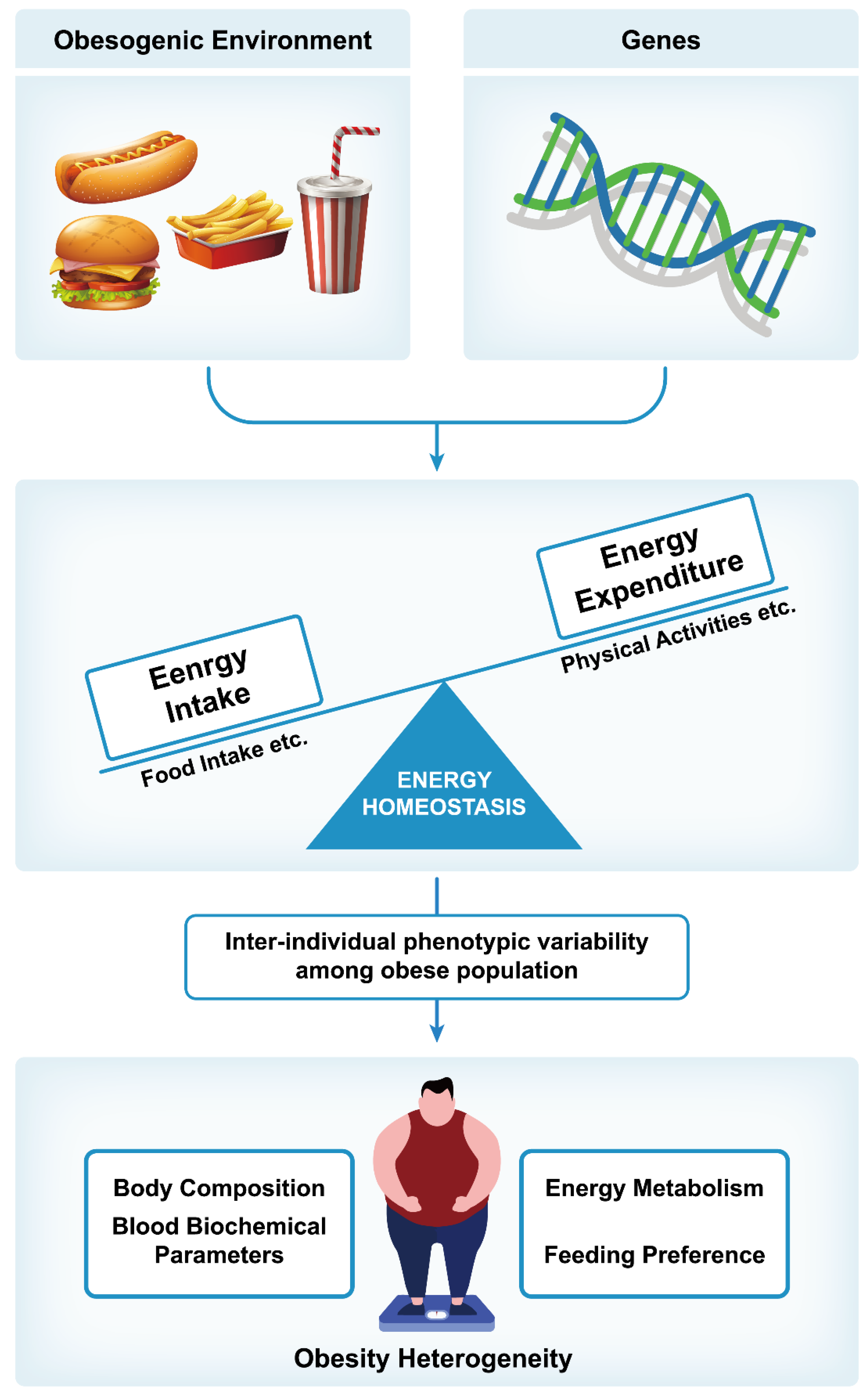

2. Regulation of Body Weight

3. Risk Factors for Obesity

3.1. Genetic Factors

3.2. Environmental Factors

4. Pathophysiology of Obesity

5. Heterogeneity of Obesity

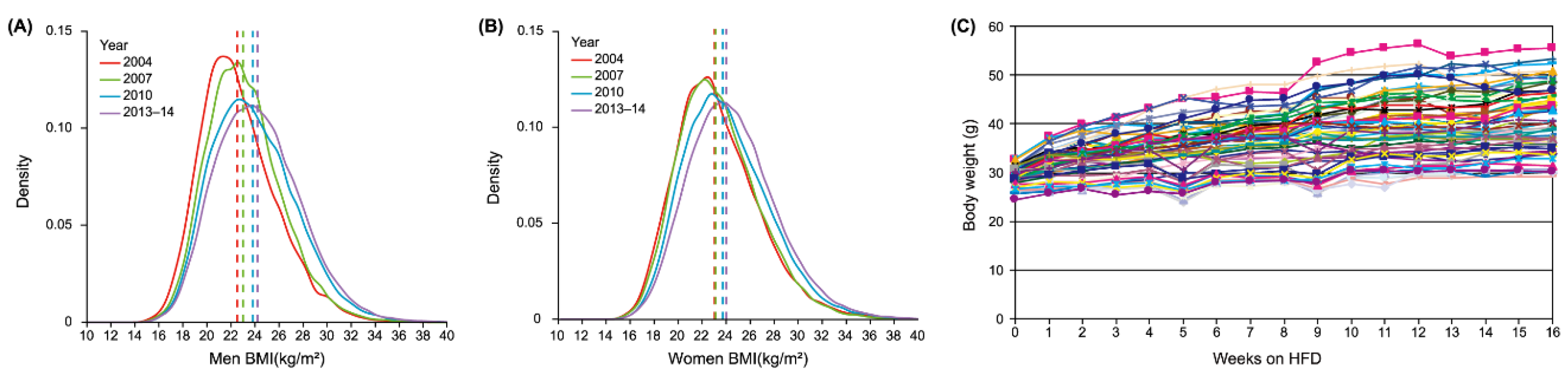

5.1. Obesity Heterogeneity in Human Population

5.2. Obesity Heterogeneity in Animals

6. Predictive Factors for Obesity Heterogeneity

6.1. Human Studies

6.2. Animal Studies

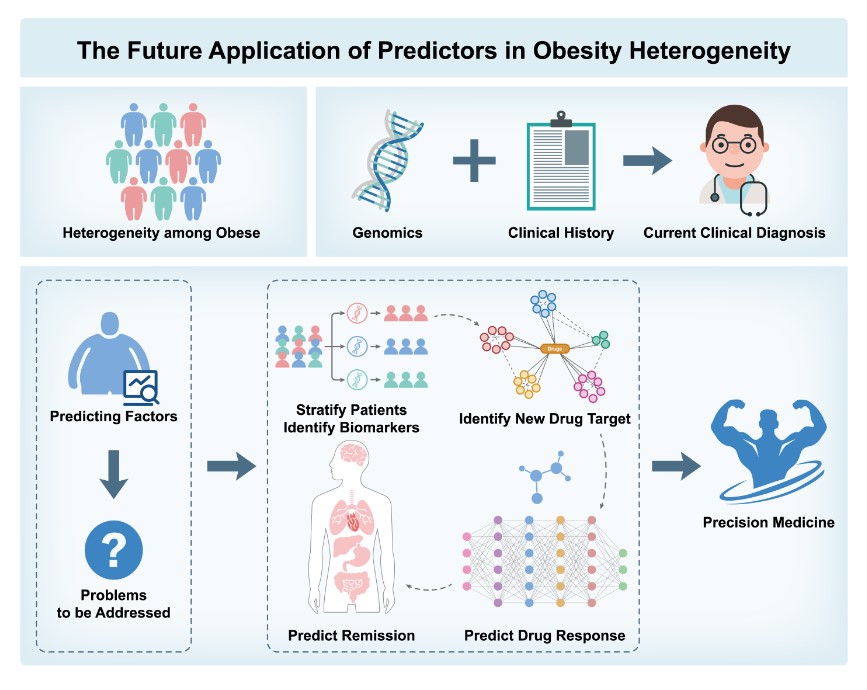

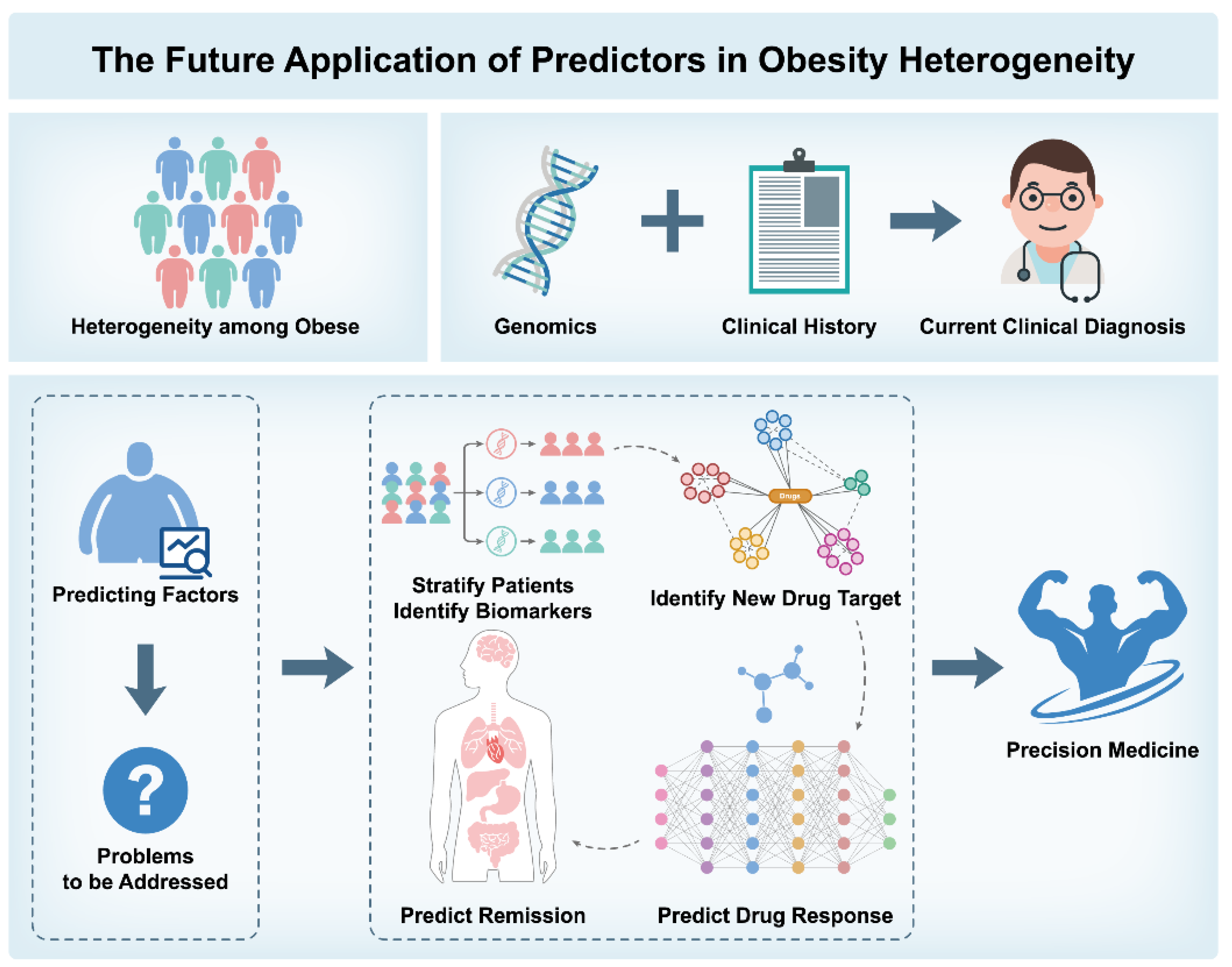

- 1.

- Patient Stratification and Biomarker Identification: Combining genetic and biochemical markers to identify high-risk individuals for personalized prevention;

- 2.

- Identification of Novel Drug Targets and Drug Response Prediction: Identifying therapeutic targets and predicting individual responses to treatments;

- 3.

- Application of Artificial Intelligence: Using machine learning to enhance obesity risk prediction accuracy;

- 4.

- Predicting Remission and Long-Term Management: Analyzing genetic and biochemical data to support personalized interventions and manage obesity progression.

7. Concluding Remarks and Future Perspectives

| Author year | Model | Design | Findings | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Xiong-Fei Pan 2021 | China's Chronic Disease and Risk Factors Surveys: 2004, 2007, 2010, 2013-14. | Cross-sectional Analysis | Obesity rates rose steadily among all groups. Overweight and obesity raise the risk of chronic diseases and early death | [71] |

| Janne S Tolstrup 2023 | 91,684 Danes | Cross-sectional Surveys | BMI distribution shifted right from 1987 to 2021, with higher values across all percentiles and socioeconomic groups | [72] |

| Aditi Krishna 2015 | 3,050,992 non-Hispanic white, non-Hispanic black, and Hispanic men and women | Longitudinal Analysis | Growing inequalities in BMI at the population level are not driven by these socioeconomic and demographic factors | [73] |

| In Sil Park 2021 | 2,708,938 Korean women | Retrospective Cohort | The impact of obesity on the risk of female-specific cancers varies with cancer type and menopausal status | [74] |

| Min Gao 2021 | 6,910,695 British people | Prospective Cohort | The risk of severe COVID-19 hospitalization and death rises linearly from a BMI of 23 kg/m² upwards | [75] |

| Rémy Burcelin 2002 | Male C57BL/6J mice (IFFACREDO, L'Arbresle, Franc) at 4-to 5-weeks age |

Feeding a high fat diet (HFD) for 9 months | Approximately 50% of the mice became obese and diabetic, 10% lean and diabetic, 10% lean and non-diabetic, and 30% showed intermediate phenotypes | [77] |

| Sarah L.Johnston 2012 | Female C57BL/6J mice (n=147; Harlan United Kingdom, Oxon, United Kingdom) at 6 weeks of age | Laboratory chow (Rat and Mouse Breeder Grower diet CRM; Special Diet Services, Essex, United Kingdom); A low-fat (10% kcal fat; n=47), medium fat (45% kcal fat; n=50) and high-fat diet (60% kcal fat, n=50; Research Diets, New Brunswick, NJ) | Female mice on a high-fat diet experienced weight gains ranging from 1.4% to 65% |

[78] |

| Robert A Koza 2006 | Fale C57BL/6J mice(n=219;the Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, Maine, United States). | Low-fat chow diet 5053 ad libitum (From weaning until 8 wk of age); High saturated fat diet D12331(At 8 wk of age) |

Body weights of 219 mice fed a high-fat diet for 4 wk were distributed in a bell-shaped curve ranging from 24–37 g | [79] |

| Li-Na Zhang 2012 | Male C57BL/6J mice (n=60; Charles River UK, Kent) and female C57BL/6J mice (n=40; Charles River UK) | Male:low-fat control diet (D12450B, 10% kcal/fat and HFD (D12451, 45% kcal/fat; Female: laboratory chow (Rat and Mouse Breeder Grower diet CRM) | Male mice from the same strain, after consuming a high-fat diet with 45% of calories from fat for 16 weeks, exhibited body weights ranging from 29.17g to 55.44g | [80] |

| Anne Kammel 2016 | Male C57BL/6J mice (n=324;Charles River, Germany) | Pre-weaning: a standard chow (sniff) Post-weaning: HFD (60 kcal% fat, 21.9 kJ/g, D12492, Research Diets, Inc., USA) |

324 male C57BL/6J mice on a 60 kcal% high-fat diet for 20 weeks exhibited body weights ranging from 27.2g to 52.7g |

[81] |

| Yongbin Yang,2014 | C57BL/6J mice (n=277 males and n=278 females) from the Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, ME) at 6 weeks of age | A low-fat diet (LFD, 10% calories from fat; n=15 male, n=15 female) or high-fat diet (HFD, 45% calories from fat; n=277 male, n=278 female) | Males and females exhibit substantial fat mass variation, which grows over time, contrasting with the stable fat-free mass | [82] |

| Wu,2022 | C57BL/6N, DBA/2, BALB/c, FVB, And C3H mouse strains | Series 1: D14071601–D14071606 and series 2: D14071607–D14071612 fixed the level of fat 60 or 20% by energy and Varied the protein content from 5 to 30% (5, 10, 15, 20, 25 and 30%, respectively) by energy; Series 3: D14071613–D14071618 and series 4: D14071619–D14071624 fixed the level of protein at 10% (series 3) (10,30, 40, 50, 70, and 80%, respectively) or 25% (series 4) (8.3, 25,33.3, 41.7, 58.3, and 66.6%, respectively) by energy and varied the fat content from 8.3 to 80% by energy | The variations in food intake and body weight changes increased with the elevation of dietary fat levels | [83] |

| Xue-Ying Zhang, Wei Shen,2018 | Male and female Brandt’s voles (3-4 mouth of age) |

HFD (22.9 kJ/g, which consisted of 27% fat [soybean oil], 18% protein, 12% crude fiber, and 23% carbohydrate; Beijing HFK Bioscience Co.); A standard rabbit pellet chow (low-fat control diet [LFD]; 17.5 kJ/g, which consisted of 2.7% fat, 18% protein, 12% crude fiber, and 47% carbohydrate) | Diversity of Thermogenic Capacity Predicts Divergent Obesity Susceptibility in a Wild Rodent | [84] |

| Levin,1985 | Male Sprague-Dawley rats (n=40; Charles River) at 3-mo of age | Purina rat chow caloric content by bomb calorimetry 4.0 kcal/g); A semisynthetic diet (“condensed milk;” CM diet) composed of chow, corn oil, sweetened condensed milk containing 16.3% fat, 14.7% protein, and 56.3% carbohydrate | After 15 wk on a moderately high-calorie high-fat (CM) diet, 43% of 40 3mo-old male Sprague-Dawley rats developed diet-induced obesity (DIO) (29% more weight gain), whereas 57% of diet-resistant (DR) rats gained no more weight than 20 chow-fed controls | [88] |

| Chang,1990 | Female Wistar rats (n=70; Harlan Madison, WI) | A low-fat diet (20% of calories from fat, 20% from protein, and 60% from carbohydrate), the HFD diet (60% of calories from fat) | OP (obesity prone) rats gained approximately twice as much weight as OR (obesity resistant) rats, OR rats had a significantly lower 24h respiratory quotient, and Insulin sensitivity was significantly higher in OR than OP rats | [89] |

| Claude Bouchord 2013 | 24 young lean men (12 pairs of identical twins) | A standardized 353 MJ (84 000 kcal) overfeeding protocol:15 percent from protein, 35 percent from lipid, and 50 percent from carbohydrate | The 100-day overfeeding protocol resulted in an average weight gain of 8.1 kg, ranging from 4.3 to 13.3 kg | [93] |

| Amit V. Khera 2019 | A polygenic predictor comprised of 2.1 million common variants | Using a Bayesian approach to calculate a posterior mean effect for all variants based on a prior and subsequent shrinkage based on linkage disequilibrium, with the optimal predictor chosen based on maximal correlation with BMI in the UK Biobank validation dataset (N = 119,951 Europeans) | Among middle-aged adults, there was a 13-kg gradient in weight and a 25-fold gradient in risk of severe obesity across polygenic score deciles. In a longitudinal birth cohort, minimal differences in birthweight were noted across score deciles, but a significant gradient emerged in early childhood, reaching 12 kg by 18 years | [108] |

| K L Leibowitz 2007 | Ten-day pregnant Sprague–Dawley rats (200–225 g; Charles iver Breeding Labs, Kingston, NY, USA) | a high-fat diet (5.15 kcal/g) consisting of 50% fat (80% lard, 20% vegetable oil), 25% carbohydrates (30% dextrin, 30% cornstarch, 40% sucrose), 25% protein (casein with 0.03% L-cysteine hydrochloride), plus 4% minerals and 3% vitamins | Among rats, there is a variability in the rate of weight gain, with those exhibiting a rapid rate reaching up to 8-10 g per day. Rats with a slower rate of weight gain achieve increments of 5-7 g per day | [94] |

Author Contributions

Acknowledgments

Conflict of Interest

Abbreviations

| EI | Energy Intake |

| BMI | Body Mass Index |

| NPY/AgRP | The Neuropeptide Y/Agouti-related peptide neurons |

| POMC/CART | The Pro-opiomelanocortin/Cocaine amphetamine-regulated transcript |

| PA | Physical Activity |

| HFD | High-Fat Diet |

| LFD | Low-Fat Diet |

| FM | Fat Mass |

| FFM | Fat-Free Mass |

| VO2max | Maximal Oxygen Uptake |

| NST | Non-Shivering Thermogenesis |

| GPS | Genome-Wide Polygenic score |

References

- Lingvay I, Cohen RV, Roux CW le, et al. Obesity in adults. Lancet 2024;404(10456):972–987; [CrossRef]

- Anderer, S. One in 8 People Worldwide Are Obese. JAMA 2024;331(14):1172; [CrossRef]

- Ward ZJ, Bleich SN, Cradock AL, et al. Projected U.S. state-level prevalence of adult obesity and severe obesity. N Engl J Med 2019;381(25):2440–2450; [CrossRef]

- Anonymous. Obesity Atlas 2024 | World Obesity Federation Global Obesity Observatory. n.d. Available from: https://data.worldobesity.org/publications/?cat=22 [Last accessed: 10/27/2024].

- Chong B, Jayabaskaran J, Kong G, et al. Trends and predictions of malnutrition and obesity in 204 countries and territories: an analysis of the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. EClinicalMedicine 2023;57:101850; [CrossRef]

- Hall KD, Farooqi IS, Friedman JM, et al. The energy balance model of obesity: beyond calories in, calories out. Am J Clin Nutr 2022;115(5):1243–1254; [CrossRef]

- Müller TD, Blüher M, Tschöp MH, et al. Anti-obesity drug discovery: advances and challenges. Nat Rev Drug Discov 2022;21(3):201–223; [CrossRef]

- Stunkard AJ, Foch TT, Hrubec Z. A twin study of human obesity. JAMA 1986;256(1):51–54.

- Bray MS, Loos RJF, McCaffery JM, et al. NIH working group report-using genomic information to guide weight management: From universal to precision treatment. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2016;24(1):14–22; [CrossRef]

- Loos RJF, Yeo GSH. 10 The genetics of obesity: From discovery to biology. Nat Rev Genet 2022;23(2):120–133; [CrossRef]

- Hall, KD. Did the food environment cause the obesity epidemic? Obesity (Silver Spring) 2018;26(1):11–13; [CrossRef]

- Blüher, M. Obesity: global epidemiology and pathogenesis. Nat Rev Endocrinol 2019;15(5):288–298; [CrossRef]

- O’Rahilly S, Farooqi IS. Human obesity: a heritable neurobehavioral disorder that is highly sensitive to environmental conditions. Diabetes 2008;57(11):2905–2910; [CrossRef]

- Norgan NG, Durnin JV. 14 The effect of 6 weeks of overfeeding on the body weight, body composition, and energy metabolism of young men. Am J Clin Nutr 1980;33(5):978–988; [CrossRef]

- De Francesco PN, Cornejo MP, Barrile F, et al. Inter-individual Variability for High Fat Diet Consumption in Inbred C57BL/6 Mice. Frontiers in Nutrition 2019;6:67; [CrossRef]

- Lister NB, Baur LA, Felix JF, et al. Child and adolescent obesity. Nat Rev Dis Primers 2023;9(1):24; [CrossRef]

- Chaptini L, Peikin S. Physiology of Weight Regulation. In: Practical Gastroenterology and Hepatology Board Review Toolkit. (Wallace MB, Aqel BA, Lindor KD, et al. eds) Wiley; 2016; pp. 1–4; [CrossRef]

- Becetti I, Bwenyi EL, de Araujo IE, et al. The neurobiology of eating behavior in obesity: Mechanisms and therapeutic targets: a report from the 23rd annual harvard nutrition obesity symposium. Am J Clin Nutr 2023;118(1):314–328; [CrossRef]

- Makaronidis J, Batterham RL. Control of Body Weight: How and Why Do We Gain Weight Easier Than We Lose It? In: Textbook of Diabetes. (Holt RIG, Flyvbjerg A. eds) Wiley; 2024; pp. 142–154; [CrossRef]

- Mitoiu BI, Nartea R, Miclaus RS. Impact of Resistance and Endurance Training on Ghrelin and Plasma Leptin Levels in Overweight and Obese Subjects. Int J Mol Sci 2024;25(15):8067; [CrossRef]

- Grosse J, Heffron H, Burling K, et al. Insulin-like peptide 5 is an orexigenic gastrointestinal hormone. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2014;111(30):11133–11138; [CrossRef]

- Cao J, Belousoff MJ, Liang Y-L, et al. A structural basis for amylin receptor phenotype. Science 2022;375(6587):eabm9609; [CrossRef]

- Kim K-S, Seeley RJ, Sandoval DA. Signalling from the periphery to the brain that regulates energy homeostasis. Nat Rev Neurosci 2018;19(4):185–196; [CrossRef]

- Steuernagel L, Lam BYH, Klemm P, et al. HypoMap-a unified single-cell gene expression atlas of the murine hypothalamus. Nat Metab 2022;4(10):1402–1419; [CrossRef]

- Dodd GT, Kim SJ, Méquinion M, et al. Insulin signaling in AgRP neurons regulates meal size to limit glucose excursions and insulin resistance. Sci Adv 2021;7(9):eabf4100; [CrossRef]

- De Solis AJ, Del Río-Martín A, Radermacher J, et al. Reciprocal activity of AgRP and POMC neurons governs coordinated control of feeding and metabolism. Nat Metab 2024;6(3):473–493; [CrossRef]

- Frayn M, Livshits S, Knäuper B. Emotional eating and weight regulation: a qualitative study of compensatory behaviors and concerns. J Eat Disord 2018;6:23; [CrossRef]

- Berthoud H-R, Münzberg H, Morrison CD. Blaming the Brain for Obesity: Integration of Hedonic and Homeostatic Mechanisms. Gastroenterology 2017;152(7):1728–1738; [CrossRef]

- Van Baak MA, Mariman ECM. Mechanisms of weight regain after weight loss — the role of adipose tissue. Nat Rev Endocrinol 2019;15(5):274–287; [CrossRef]

- Pillon NJ, Loos RJF, Marshall SM, et al. Metabolic consequences of obesity and type 2 diabetes: Balancing genes and environment for personalized care. Cell 2021;184(6):1530–1544; [CrossRef]

- Kaisinger LR, Kentistou KA, Stankovic S, et al. Large-scale exome sequence analysis identifies sex- and age-specific determinants of obesity. Cell Genom 2023;3(8):100362; [CrossRef]

- Israeli H, Degtjarik O, Fierro F, et al. Structure reveals the activation mechanism of the MC4 receptor to initiate satiation signaling. Science 2021;372(6544):808–814; [CrossRef]

- Namjou B, Stanaway IB, Lingren T, et al. Evaluation of the MC4R gene across eMERGE network identifies many unreported obesity-associated variants. Int J Obes (Lond) 2021;45(1):155–169; [CrossRef]

- Zhao Y, Chukanova M, Kentistou KA, et al. Protein-truncating variants in BSN are associated with severe adult-onset obesity, type 2 diabetes and fatty liver disease. Nat Genet 2024;56(4):579–584; [CrossRef]

- Trang K, Grant SFA. Genetics and epigenetics in the obesity phenotyping scenario. Rev Endocr Metab Disord 2023;24(5):775–793; [CrossRef]

- Saeed S, Bonnefond A, Froguel P. Obesity: Exploring its connection to brain function through genetic and genomic perspectives. Mol Psychiatry 2024; [CrossRef]

- Frayling TM, Timpson NJ, Weedon MN, et al. A common variant in the FTO gene is associated with body mass index and predisposes to childhood and adult obesity. Science 2007;316(5826):889–894; [CrossRef]

- Locke AE, Kahali B, Berndt SI, et al. Genetic studies of body mass index yield new insights for obesity biology. Nature 2015;518(7538):197–206; [CrossRef]

- Congdon, P. Obesity and Urban Environments. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2019;16(3):464; [CrossRef]

- Strain T, Flaxman S, Guthold R, et al. National, regional, and global trends in insufficient physical activity among adults from 2000 to 2022: a pooled analysis of 507 population-based surveys with 5·7 million participants. Lancet Glob Health 2024;12(8):e1232–e1243; [CrossRef]

- Pineda E, Stockton J, Scholes S, et al. Food environment and obesity: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ Nutr Prev Health 2024;7(1):204–211; [CrossRef]

- Godfray HCJ, Aveyard P, Garnett T, et al. Meat consumption, health, and the environment. Science 2018;361(6399):eaam5324; [CrossRef]

- Pineda E, Atanasova P, Wellappuli NT, et al. Policy implementation and recommended actions to create healthy food environments using the Healthy Food Environment Policy Index (Food-EPI): a comparative analysis in South Asia. The Lancet Regional Health - Southeast Asia 2024;26; [CrossRef]

- Willett W, Rockström J, Loken B, et al. Food in the Anthropocene: the EAT-Lancet Commission on healthy diets from sustainable food systems. Lancet 2019;393(10170):447–492; [CrossRef]

- Elmaleh-Sachs A, Schwartz JL, Bramante CT, et al. Obesity Management in Adults: A Review. JAMA 2023;330(20):2000–2015; [CrossRef]

- Trang K, Grant SFA. Genetics and epigenetics in the obesity phenotyping scenario. Rev Endocr Metab Disord 2023;24(5):775–793; [CrossRef]

- Zhang X, Zhang G, Zhang H, et al. Hypothalamic IKKbeta/NF-kappaB and ER stress link overnutrition to energy imbalance and obesity. Cell 2008;135(1):61–73; [CrossRef]

- Muñoz, JP. The impact of endocrine-disrupting chemicals on stem cells: Mechanisms and implications for human health. Journal of Environmental Sciences 2025;147:294–309; [CrossRef]

- Champagne, FA. Epigenetics and developmental plasticity across species. Dev Psychobiol 2013;55(1):33–41; [CrossRef]

- Ma K, Yin K, Li J, et al. The Hypothalamic Epigenetic Landscape in Dietary Obesity. Advanced Science 2024;11(9):2306379; [CrossRef]

- Keller M, Yaskolka Meir A, Bernhart SH, et al. DNA methylation signature in blood mirrors successful weight-loss during lifestyle interventions: the CENTRAL trial. Genome Med 2020;12(1):97; [CrossRef]

- Wang G, Speakman JR. Analysis of Positive Selection at Single Nucleotide Polymorphisms Associated with Body Mass Index Does Not Support the “Thrifty Gene” Hypothesis. Cell Metab 2016;24(4):531–541; [CrossRef]

- Blüher, M. Obesity: global epidemiology and pathogenesis. Nat Rev Endocrinol 2019;15(5):288–298; [CrossRef]

- Ouchi N, Parker JL, Lugus JJ, et al. Adipokines in inflammation and metabolic disease. Nat Rev Immunol 2011;11(2):85–97; [CrossRef]

- Hill JO, Wyatt HR, Peters JC. Energy Balance and Obesity. Circulation 2012;126(1):126–132; [CrossRef]

- Lee SJ, Shin SW. Mechanisms, Pathophysiology, and Management of Obesity. N Engl J Med 2017;376(15):1491–1492; [CrossRef]

- Chau Y-Y, Bandiera R, Serrels A, et al. Visceral and subcutaneous fat have different origins and evidence supports a mesothelial source. Nat Cell Biol 2014;16(4):367–375; [CrossRef]

- Zacharia A, Saidemberg D, Mannully CT, et al. Distinct infrastructure of lipid networks in visceral and subcutaneous adipose tissues in overweight humans. Am J Clin Nutr 2020;112(4):979–990; [CrossRef]

- Lindhorst A, Raulien N, Wieghofer P, et al. Adipocyte death triggers a pro-inflammatory response and induces metabolic activation of resident macrophages. Cell Death Dis 2021;12(6):579; [CrossRef]

- Wernstedt Asterholm I, Tao C, Morley TS, et al. Adipocyte inflammation is essential for healthy adipose tissue expansion and remodeling. Cell Metab 2014;20(1):103–118; [CrossRef]

- Chavakis T, Alexaki VI, Ferrante AW. Macrophage function in adipose tissue homeostasis and metabolic inflammation. Nat Immunol 2023;24(5):757–766; [CrossRef]

- Scheja L, Heeren J. The endocrine function of adipose tissues in health and cardiometabolic disease. Nat Rev Endocrinol 2019;15(9):507–524; [CrossRef]

- Zhou L, Yu M, Arshad M, et al. Coordination Among Lipid Droplets, Peroxisomes, and Mitochondria Regulates Energy Expenditure Through the CIDE-ATGL-PPARα Pathway in Adipocytes. Diabetes 2018;67(10):1935–1948; [CrossRef]

- Grabner GF, Xie H, Schweiger M, et al. Lipolysis: cellular mechanisms for lipid mobilization from fat stores. Nat Metab 2021;3(11):1445–1465; [CrossRef]

- Brandão I, Martins MJ, Monteiro R. Metabolically Healthy Obesity-Heterogeneity in Definitions and Unconventional Factors. Metabolites 2020;10(2):48; [CrossRef]

- Sulc J, Winkler TW, Heid IM, et al. Heterogeneity in Obesity: Genetic Basis and Metabolic Consequences. Curr Diab Rep 2020;20(1):1; [CrossRef]

- Hu H, Song J, MacGregor GA, et al. Consumption of Soft Drinks and Overweight and Obesity Among Adolescents in 107 Countries and Regions. JAMA Netw Open 2023;6(7):e2325158; [CrossRef]

- Pedersen MM, Ekstrøm CT, Sørensen TIA. Emergence of the obesity epidemic preceding the presumed obesogenic transformation of the society. Sci Adv 2023;9(37):eadg6237; [CrossRef]

- Ogden CL, Fryar CD, Martin CB, et al. Trends in obesity prevalence by race and hispanic origin-1999-2000 to 2017-2018. JAMA 2020;324(12):1208–1210; [CrossRef]

- Mu L, Liu J, Zhou G, et al. Obesity prevalence and risks among Chinese adults: Findings from the China PEACE million persons project, 2014-2018. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes 2021;14(6):e007292; [CrossRef]

- Pan X-F, Wang L, Pan A. Epidemiology and determinants of obesity in China. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol 2021;9(6):373–392; [CrossRef]

- Tolstrup JS, Bramming M, Davidsen M, et al. Time trends in body mass index distribution in the general population in Denmark from 1987 to 2021. Dan Med J 2023;70(10):A03230139.

- Krishna A, Razak F, Lebel A, et al. Trends in group inequalities and interindividual inequalities in BMI in the United States, 1993-2012. Am J Clin Nutr 2015;101(3):598–605; [CrossRef]

- Park IS, Kim SI, Han Y, et al. Risk of female-specific cancers according to obesity and menopausal status in 2•7 million Korean women: Similar trends between Korean and Western women. Lancet Reg Health West Pac 2021;11:100146; [CrossRef]

- Gao M, Piernas C, Astbury NM, et al. Associations between body-mass index and COVID-19 severity in 6·9 million people in England: a prospective, community-based, cohort study. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol 2021;9(6):350–359; [CrossRef]

- Surwit RS, Kuhn CM, Cochrane C, et al. Diet-induced type II diabetes in C57BL/6J mice. Diabetes 1988;37(9):1163–1167; [CrossRef]

- Burcelin R, Crivelli V, Dacosta A, et al. Heterogeneous metabolic adaptation of C57BL/6J mice to high-fat diet. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 2002;282(4):E834-842; [CrossRef]

- Johnston SL, Souter DM, Tolkamp BJ, et al. Intake compensates for resting metabolic rate variation in female C57BL/6J mice fed high-fat diets. Obesity (Silver Spring, Md) 2007;15(3):600–606; [CrossRef]

- Koza RA, Nikonova L, Hogan J, et al. Changes in gene expression foreshadow diet-induced obesity in genetically identical mice. PLoS genetics 2006;2(5):e81; [CrossRef]

- Zhang L-N, Morgan DG, Clapham JC, et al. Factors predicting nongenetic variability in body weight gain induced by a high-fat diet in inbred C57BL/6J mice. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2012;20(6):1179–1188; [CrossRef]

- Kammel A, Saussenthaler S, Jähnert M, et al. Early hypermethylation of hepatic Igfbp2 results in its reduced expression preceding fatty liver in mice. Hum Mol Genet 2016;25(12):2588–2599; [CrossRef]

- Yang Y, Smith DL, Keating KD, et al. Variations in body weight, food intake and body composition after long-term high-fat diet feeding in C57BL/6J mice. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2014;22(10):2147–2155; [CrossRef]

- Wu Y, Hu S, Yang D, et al. Increased Variation in Body Weight and Food Intake Is Related to Increased Dietary Fat but Not Increased Carbohydrate or Protein in Mice. Frontiers in Nutrition 2022;9:835536; [CrossRef]

- Zhang X-Y, Shen W, Liu D-Z, et al. Diversity of Thermogenic Capacity Predicts Divergent Obesity Susceptibility in a Wild Rodent. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2018;26(1):111–118; [CrossRef]

- Levin BE, Comai K, Sullivan AC. Metabolic and sympatho-adrenal abnormalities in the obese Zucker rat: effect of chronic phenoxybenzamine treatment. Pharmacol Biochem Behav 1981;14(4):517–525; [CrossRef]

- Schemmel R, Mickelsen O, Gill JL. Dietary obesity in rats: Body weight and body fat accretion in seven strains of rats. J Nutr 1970;100(9):1041–1048; [CrossRef]

- Mickelsen O, Takahashi S, Craig C. Experimental obesity. I. Production of obesity in rats by feeding high-fat diets. J Nutr 1955;57(4):541–554; [CrossRef]

- Levin BE, Finnegan M, Triscari J, et al. Brown adipose and metabolic features of chronic diet-induced obesity. Am J Physiol 1985;248(6 Pt 2):R717-723; [CrossRef]

- Chang S, Graham B, Yakubu F, et al. Metabolic differences between obesity-prone and obesity-resistant rats. Am J Physiol 1990;259(6 Pt 2):R1103-1110; [CrossRef]

- Clegg DJ, Benoit SC, Reed JA, et al. Reduced anorexic effects of insulin in obesity-prone rats fed a moderate-fat diet. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 2005;288(4):R981-986; [CrossRef]

- Levin BE, Dunn-Meynell AA, Balkan B, et al. Selective breeding for diet-induced obesity and resistance in Sprague-Dawley rats. Am J Physiol 1997;273(2 Pt 2):R725-730; [CrossRef]

- Elmaleh-Sachs A, Schwartz JL, Bramante CT, et al. Obesity Management in Adults: A Review. JAMA 2023;330(20):2000–2015; [CrossRef]

- Bouchard C, Tchernof A, Tremblay A. Predictors of body composition and body energy changes in response to chronic overfeeding. Int J Obes (Lond) 2014;38(2):236–242; [CrossRef]

- Leibowitz KL, Chang G-Q, Pamy PS, et al. Weight gain model in prepubertal rats: prediction and phenotyping of obesity-prone animals at normal body weight. Int J Obes (Lond) 2007;31(8):1210–1221; [CrossRef]

- Nishikawa S, Yasoshima A, Doi K, et al. Involvement of sex, strain and age factors in high fat diet-induced obesity in C57BL/6J and BALB/cA mice. Exp Anim 2007;56(4):263–272; [CrossRef]

- Hwang L-L, Wang C-H, Li T-L, et al. Sex differences in high-fat diet-induced obesity, metabolic alterations and learning, and synaptic plasticity deficits in mice. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2010;18(3):463–469; [CrossRef]

- Ingvorsen C, Karp NA, Lelliott CJ. The role of sex and body weight on the metabolic effects of high-fat diet in C57BL/6N mice. Nutr Diabetes 2017;7(4):e261; [CrossRef]

- Bailey KR, Rustay NR, Crawley JN. Behavioral phenotyping of transgenic and knockout mice: practical concerns and potential pitfalls. ILAR J 2006;47(2):124–131; [CrossRef]

- Hu S, Togo J, Wang L, et al. Effects of dietary macronutrients and body composition on glucose homeostasis in mice. Natl Sci Rev 2021;8(1):nwaa177; [CrossRef]

- Hu S, Wang L, Yang D, et al. Dietary Fat, but Not Protein or Carbohydrate, Regulates Energy Intake and Causes Adiposity in Mice. Cell Metab 2018;28(3):415-431.e4; [CrossRef]

- Petro AE, Cotter J, Cooper DA, et al. Fat, carbohydrate, and calories in the development of diabetes and obesity in the C57BL/6J mouse. Metabolism 2004;53(4):454–457; [CrossRef]

- Lathe, R. The individuality of mice. Genes Brain Behav 2004;3(6):317–327; [CrossRef]

- As M, M S, A S. Hypothalamic phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase pathway of leptin signaling is impaired during the development of diet-induced obesity in FVB/N mice. Endocrinology 2008;149(3); [CrossRef]

- Huang Y, Osorio Mendoza J, Li M, et al. Impact of graded maternal dietary fat content on offspring susceptibility to high-fat diet in mice. Obesity 2021;29(12):2055–2067; [CrossRef]

- Armitage JA, Khan IY, Taylor PD, et al. Developmental programming of the metabolic syndrome by maternal nutritional imbalance: how strong is the evidence from experimental models in mammals? J Physiol 2004;561(Pt 2):355–377; [CrossRef]

- Holmes A, le Guisquet AM, Vogel E, et al. Early life genetic, epigenetic and environmental factors shaping emotionality in rodents. Neurosci Biobehav Rev 2005;29(8):1335–1346; [CrossRef]

- Vucetic Z, Kimmel J, Totoki K, et al. Maternal high-fat diet alters methylation and gene expression of dopamine and opioid-related genes. Endocrinology 2010;151(10):4756–4764; [CrossRef]

- Khera AV, Chaffin M, Wade KH, et al. Polygenic Prediction of Weight and Obesity Trajectories from Birth to Adulthood. Cell 2019;177(3):587-596.e9; [CrossRef]

| Predictors | Relationship with BW change | Research object | Methods | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SFRP5 | Positive | Mice | Microarray analysis and qRT-PCR | [79] |

| MEST | Positive | Mice | Microarray analysis and qRT-PCR | [79] |

| BMP3 | Positive | Mice | Microarray analysis and qRT-PCR | [79] |

| Fat Mass | Positive | Mice | Transmitter and dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry | [80,82] |

| Physical Activity | Negative | Mice | Transmitter and dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry | [80] |

| Energy intake | Positive | Mice | HFD:4.73kcal/g; LFD:3.85kcal/g | [82] |

| Non-shivering thermogenesis | Positive | Voles | Induced by a subcutaneous injection of NE around the interscapular BAT | [84] |

| Plasma Leptin | Positive | Population | Specific enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay | [93] |

| Muscle Oxidative capacity | Negative | Population | Enzyme Activity Measurement | [93] |

| Maximal oxygen uptake | Negative | Population | Open gas circuit system | [93] |

| Androgen | Negative | Population | Ethanol extraction, enzymatic hydrolysis, Sephadex chromatography. | [93] |

| Fat Free Mass | Positive in mice Negative in population |

Mice and Population | Transmitter and dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry;Standardized equations for body weight and percentage of fat mass | [80,82,93] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).