Introduction

Faecal indicator bacteria have been used for one and a half centuries to indicate faecal contamination of water and associated health risks (Holcomb & Stewart, 2020). While useful as indicators of potential faecally transmitted pathogens, reliance on E. coli and Enterococci as proxies can miss out the presence of other pathogens and importantly for pathogens of non-faecal origin. The WHO guidelines (WHO 2021) recommend a risk-based approach to consider pathogens that are not necessarily and almost exclusively associated with faecal contamination. Non-faecally transmitted bacteria in recreational waters pose significant health risks to users, underscoring the limitations of relying solely on faecal indicator bacteria (FIB) to assess water quality. These bacteria, which originate from sources other than faecal contamination, can include environmental pathogens such as Vibrio spp., Pseudomonas aeruginosa, and Legionella spp., as well as opportunistic bacteria that thrive in aquatic ecosystems (Boehm & Soller. 2013, Fewtrell & Kay. 2015, Rodrigues et al. 2017). In fact, a recent report from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) (Hlavsa et al. 2021) shows that these organisms were the main waterbone illness provoking agents in treated recreational water between 2015-2019. All these pathogens can enter recreational waters through various sources and pathways. For instance, Vibrio species thrive in warm, brackish, or marine environments, with their populations often peaking during the summer months (Sampaio et al., 2022). Climate change with increased water temperatures is also an emerging factor for increases in Vibrio spp. abundance. Similarly, bacteria such as Pseudomonas aeruginosa can persist in sediments or biofilms, where they are shielded from environmental stressors (Brandão et al. 2022). Human activity also plays a role; the introduction of skin flora and the use of improperly treated recreational water features, such as pools or water parks, can amplify the presence of these bacteria. (Ayi B. 2015)

Exposure to non-fecally transmitted bacteria can lead to a range of health problems for recreational water users. These bacteria are often associated with skin and soft tissue infections, such as cellulitis, dermatitis, or, in severe cases, necrotising infections caused by pathogens like Vibrio vulnificus or Pseudomonas aeruginosa. (Guida et al., 2016). Contact with contaminated water can also result in ear, eye, and respiratory issues, including swimmer’s ear (otitis externa) (Pantazidou et al. 2022) and respiratory illnesses linked to Legionella exposure (National Academy of Sciences et al. 2019). For immunocompromised individuals, these pathogens may lead to systemic infections, including sepsis, particularly if the skin barrier is compromised through cuts or abrasions.

The presence of these pathogens presents a challenge for water quality monitoring, which relies on FIB such as E. coli or enterococci. (WHO, 2021; European Parliament and Council, 2006). As a result, a water body considered safe based on FIB levels may still harbour significant health risks from environmental bacteria. Additionally, the standard culture methods for determining FIB for water quality assessment take over 24h for results, meaning water quality is only known after exposure (ISO 7899-1 or ISO 7899-2 for enterococci and ISO 9308-3 or ISO 9308-1 for E. coli). Moreover, the last revision of these standards recommends their use in either very clean or very dirty waters for enterococci. In addition, sampling is not performed continuously so discrete points are all that regulators can use (Wade et al., 2010). Moreover, by focussing solely on FIB it is possible that other pathogens that are not necessarily of faecal nature, may go undetected (Topić et al. 2021). These drawbacks to the current culture-based approaches highlight the need for not only rapid, but also more complete solutions with the ability to monitor water quality at many locations and at different times and to better indicate a broader set of pathogens.

A rapid and simple test of bacterial water quality would therefore be a very useful tool. Previous studies have suggested that measuring endotoxin (lipopolysaccharide (LPS)), present in the outer membrane of Gram-negative bacteria and some cyanobacteria, may be a useful technique for rapidly determining bacterial biomass and quality of water (Evans et al., 1978; Jorgensen et al., 1979; Haas et al., 1983). Previous work by our group has shown the applicability of using endotoxin as a marker of faecal contamination of seawater (Sattar et al., 2014, Good et al., 2024) and that measuring endotoxin correlates with inflammatory effects of contaminated water samples (Sattar et al., 2019). Researchers at Molendotech have developed a near real-time assay (Bacterisk®) to assess bacterial water quality based on endotoxin, which can be conducted by non-specialist staff in situ. The advantage of measuring endotoxin as an indicator for contaminated water is that the test is specific for LPS, a compound which only naturally occurs in the cell walls of Gram-negative bacteria. LPS comprises a relatively constant proportion of a Gram-negative bacterial cell and Gram-negative bacteria account for 80 to 95% of the prokaryotes found in waters (Anwar and Choi, 2014). Moreover, endotoxin could indicate the presence of Gram-negative pathogens not detected by current culture of total coliforms or E. coli. Therefore, this novel assay would allow near real-time assessment of water quality and the flexibility to sample at several locations and at different time points. It would thus provide a more complete assessment of water quality and also allow rapid testing in remote and disaster areas where access to laboratories and water testing facilities is challenging.

The presence of AntiMicrobial Resistance (AMR) genes is also not covered by FIB monitoring. Recreational waters, including coastal bathing areas, urban lakes, and estuarine environments, act as reservoirs and transmission pathways for antimicrobial resistance genes (ARGs). Leonard et al. (2015) emphasise the risk of human exposure to antibiotic-resistant bacteria during recreational activities in coastal waters, where the dissemination of ARGs is influenced by anthropogenic pollution. In this perspective, Farrell et al. (2023) link recreational water use to an increased carriage of antimicrobial-resistant organisms and Singh et al. (2022) describe how wastewater and natural water systems act as vectors for the spread of ARGs into recreational waters. Variations in ARG profiles across different recreational water sources, shaped by local microbial communities and water management practices have been demonstrated by Han et al. (2022) and Li et al. (2022). These findings underscore the critical need to monitor and mitigate ARG contamination to protect both environmental and public health.

Previous reports have highlighted the usefulness of the rapid Bacterisk technology in determining coastal water quality. The present study was undertaken to assess the use of Bacterisk as a rapid method to determine bacterial contamination in fresh (inland) waters and to provide evidence for the detection on non-faecal pathogens by this method. This study therefore challenges the sole use of FIB detection for the assessment of water quality.

Materials and Methods

Water Sampling

A total of 36 inland water samples were collected from various river locations in the southwest of England. Briefly, 500 mL samples were taken using sterile bottles 30 cm below the water’s surface in water at least one meter deep. The samples were then transported in the dark and tested within 4 hours or stored in a fridge (2-8 °C) and tested no later than 24 hours after collection.

Bacterial Culture Identification (ISO Methods)

Appropriate volumes of each water sample (1, 10, and 100 mL) were aseptically filtered through a 0.45 µm membrane (Whatman, UK) using a 6-branch vacuum manifold (Sartorius, UK). Following ISO 9308-1:2014 and ISO 7899-2:2000, Membranes were placed on membrane TBX agar (Oxoid, UK) and incubated at 30°C for 4 hours, then at 37°C for 14 hours for the detection of presumptive E. coli or on Slanetz and Bartley medium (Oxoid, UK) and incubated at 36°C for 44 hours for the detection of presumptive intestinal enterococci. The numbers of colony-forming units (CFU) were then calculated and expressed as CFU/100mL.

Bacterisk Assay

The Bacterisk assay (Molendotech Ltd., Brixham, UK;

www.molendotech.com) was performed following the manufacturer’s instructions. Briefly, the samples were diluted 1 in 40 in dilution buffer and then 200µL was transferred to a reaction tube containing the lyophilised detection reagent. The samples were then incubated at 37°C for 13 minutes using the integrated Bacterisk incubator and reader. An Endotoxin Risk Unit (ERU) score was then calculated by the device based on the absorbance of the sample at 405 nm. Both a negative control (endotoxin-free water) and a positive control (Endotoxin from

E. coli 055:B5) was run with every assay.

Sequencing Analysis

Bacterial gene sequencing was performed by Eurofins using the INVIEW Microbiome Profiling package with amplification and Illumina MiSeq sequencing of the hypervariable regions in the 16S rRNA gene. This method amplifies and sequences three targets from all DNA samples (16S V1-V3, 16S V3-V4 or 16S V3-V5).

qPCR

Species-specific quantitative real-time PCR and subsequent amplicon detections were performed on inland water samples from the river Dart by Friends of the Dart and Surfers Against Sewage UK.

Determination of Uncertainty of Measurement (UoM)

Data on samples using the Bacterisk methodology were analysed in duplicate (A and B). Analysis for Measurement of Uncertainty was performed following the guidelines for expanded uncertainty (Magnusson et al., 2017), often referred to as the square root of the sum of the squares multiplied by a coverage factor (k) to the desired confidence.

Sum ((log10B-log10A)2) n = total variance (T)

Standard Deviation (SD) = T/n

To calculate the expanded uncertainty, the relative SD is calculated by dividing the standard deviation by the mean of the Log10 observed values, and represented as a percentage. To calculate the expanded uncertainty this relative standard deviation is multiplied by a coverage factor (k) at the required confidence limit. Various values have been suggested for confidence limits both fixed and variable. A standard approach is to use a fixed k value of 2 for a 95% confidence.

Statistical Analysis

Statistical analyses on the distribution of samples and the correlation between Bacterisk data and culture-derived water quality were performed with Fisher’s exact test and Chi-square test using GraphPad prism version 9 for Windows, GraphPad Software, Boston, Massachusetts USA,

www.graphpad.com. Receiver Operating Characteristics (ROC) curve, was used to determine the optimal threshold ERU value used to discriminate the water quality groups. The ROC curve uses 1 – specificity on the x-axis, as calculated:

and sensitivity (true positive) on the y-axis, as calculated:

The ROC curve also provides an area under the curve (AUC) value between 0 and 1. The closer the AUC value is to 1 the better the model is at predicting a correct classification, whereas a value of 0.5 represents a model with no ability to predict a correct classification. A model with an AUC of greater than 0.8 is considered acceptable (Nahm 2022).

Results

Use of Expanded Uncertainty was used to provide a limit of quantification for the Bacterisk method, i.e. a value where we could provide confidence in the observed result. To aid this, the observed values were plotted as pairs in a low-high format. This data appeared to demonstrate that values begin to show greater significance between 20 and 30 Endotoxin Risk Units (ERU). The expanded uncertainty was calculated for values of 20 ERU, 25ERU, and 30ERU; to be included in assessment only one of the pairs of results required to satisfy this limit. Results obtained at the 3 different

k values are shown in

Table 1.

From the results obtained in

Table 1, the Expanded Uncertainty of Measurement decreases as the lower limit of inclusion increases. Comparing this to results obtained from culture-based microbiology methods (in house testing) values range from 12% to around 25%. Therefore, there is a limit of accurate quantification of 25 ERU.

A total of 36 inland water samples were analysed in parallel by the Bacterisk assay to calculate Endotoxin Risk Units (ERU) and by membrane filtration to enumerate the levels of E. coli and intestinal enterococci (CFU/100 mL), according to ISO 9308-1:2014 and ISO 7899-2:2000, respectively. The results were compared with data obtained for coastal water samples collected and analysed by the same methods as published previously (Good et al., 2024).

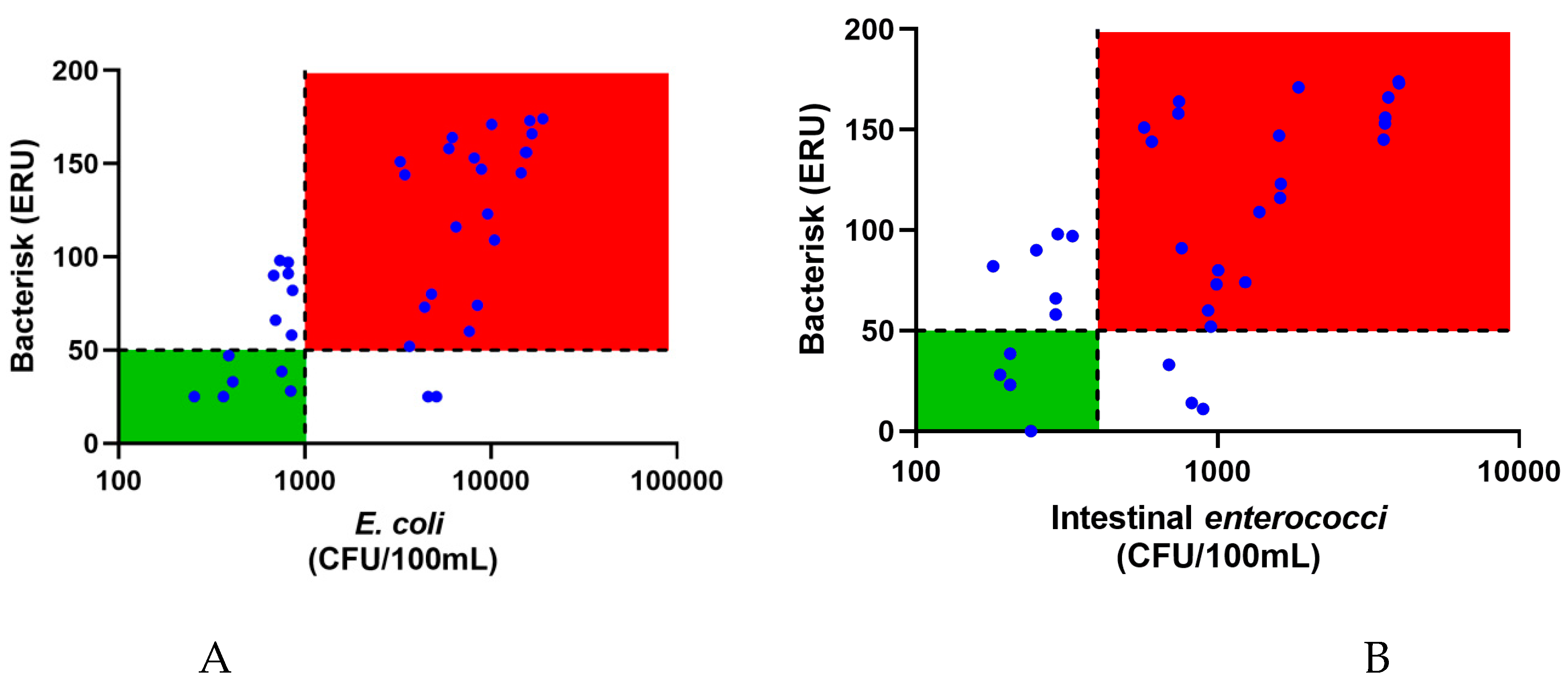

Figure 1 shows the water quality of inland water samples determined by Bacterisk and compared with culture of

E. coli and enterococci by membrane filtration method. As can be seen, many of the samples of inland waters are seen to be of poor quality as assessed by the EU bathing water directive. All the data are presented in

Table S1 in supplementary data.

The ROC analysis of the data from

Figure 1A gave an area under the curve of 0.826 (p=0.0013) and sensitivity of 91.3% and specificity of 46.2%. The low specificity is due to the Bacterisk assay detecting all Gram-negative bacteria not just

E. coli and hence alerting to the presence of potential pathogens.

Though intestinal

enterococci are also used as a FIB it is a Gram-positive bacterium, and in fact the only current parameter recommended by the most recent WHO guidelines for recreational water quality; there was a correlation between intestinal

enterococci and ERU. As can be seen from

Figure 1, Bacterisk ERU values could track enterococci and ERU data were a good proxy for enterococci levels.

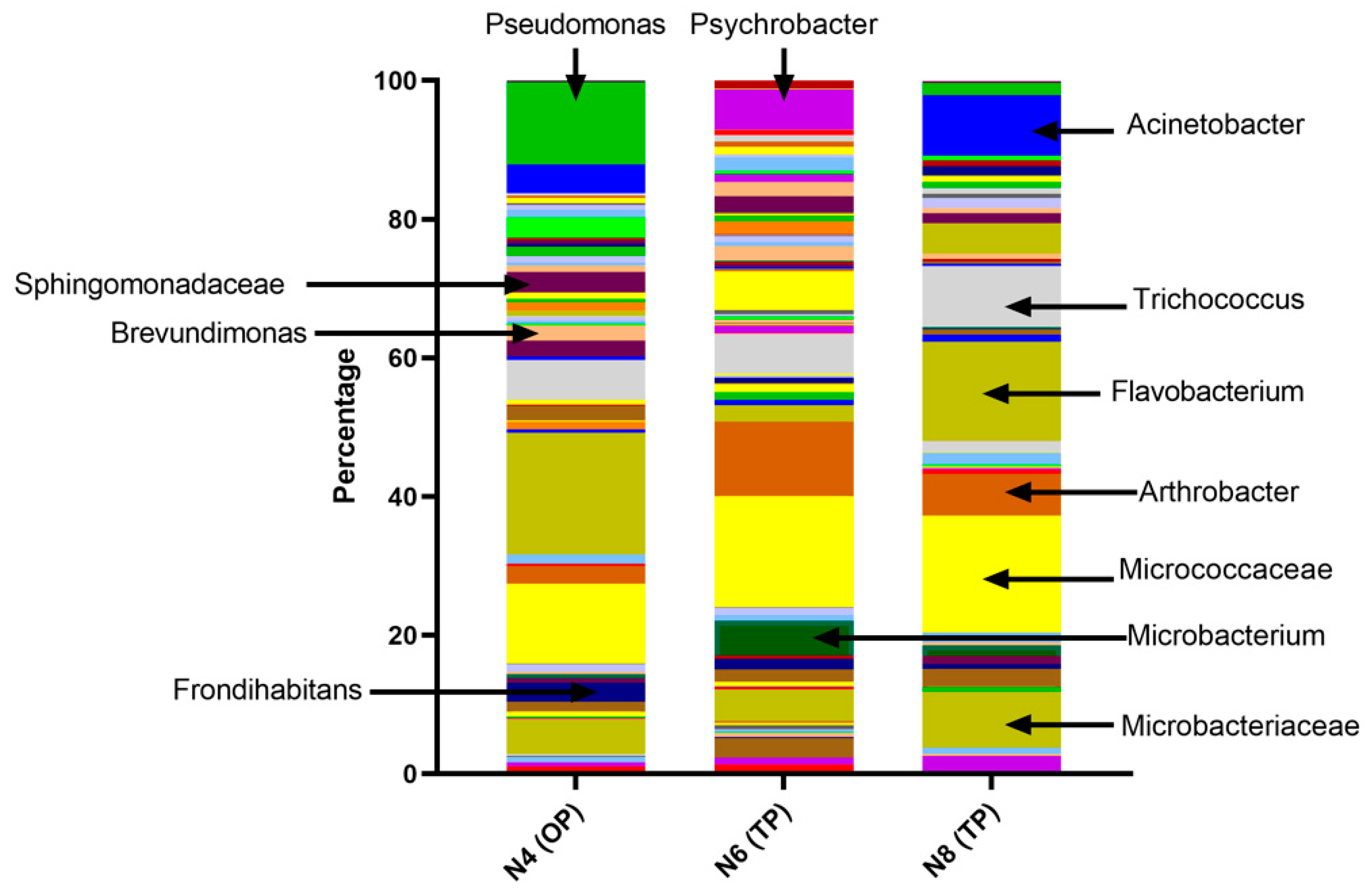

Due to Bacterisk determining the levels of a Gram-negative molecule (endotoxin) as a marker of water contamination, it not only provides good correlation with

E. coli but will respond to other Gram-negative bacteria including non-FIB. These may be pathogenic and of concern for human health. These have been included in our data as ‘other’ or ‘off-target’ positives. It is important to understand what these other bacteria are and how they may contribute to the Bacterisk data. To accomplish this, 10 water samples from known ‘off-target’ positive results together with water samples giving low or high

E. coli results, were DNA-sequenced to determine the bacterial flora composition. Representative results are shown in

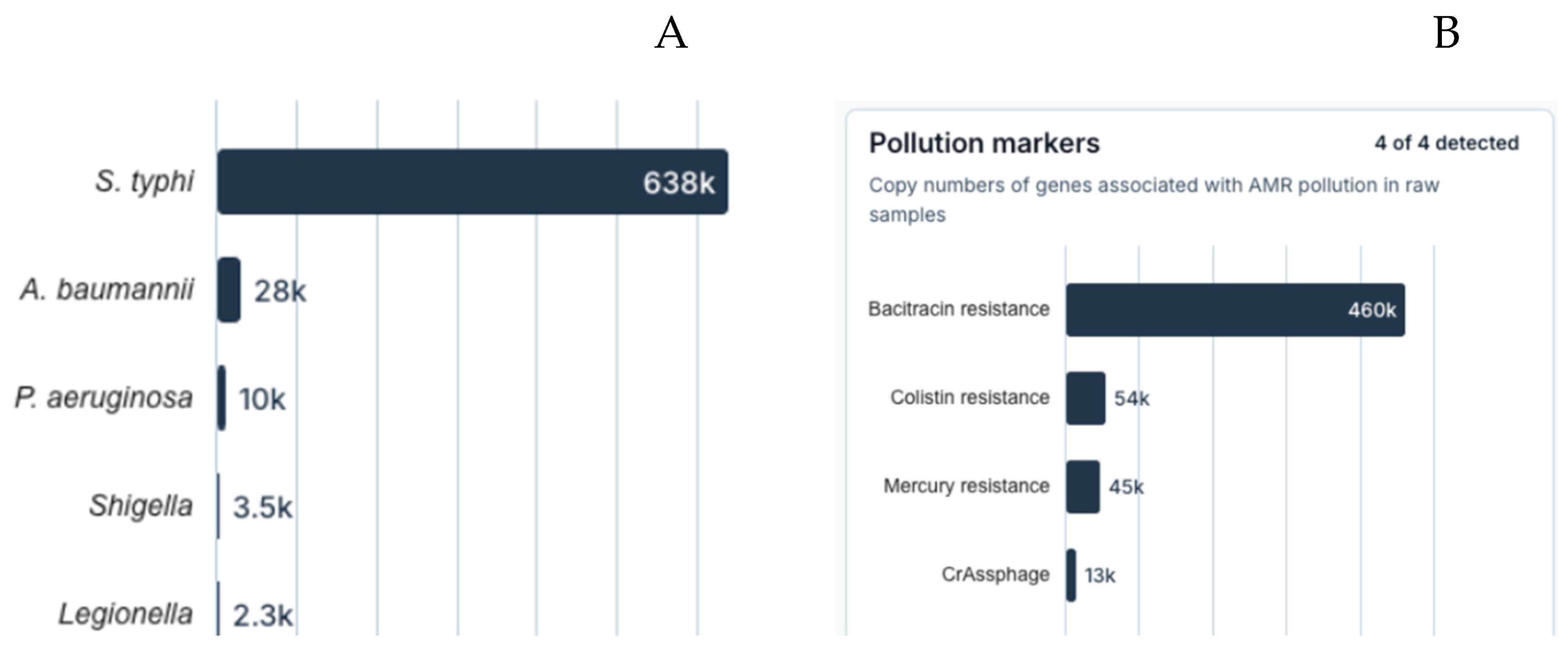

Figure 2. In addition, we obtained qPCR data from samples from one of the river locations. The qPCR data (

Figure 3) reveals the presence of several pathogenic species including

S. typhi.

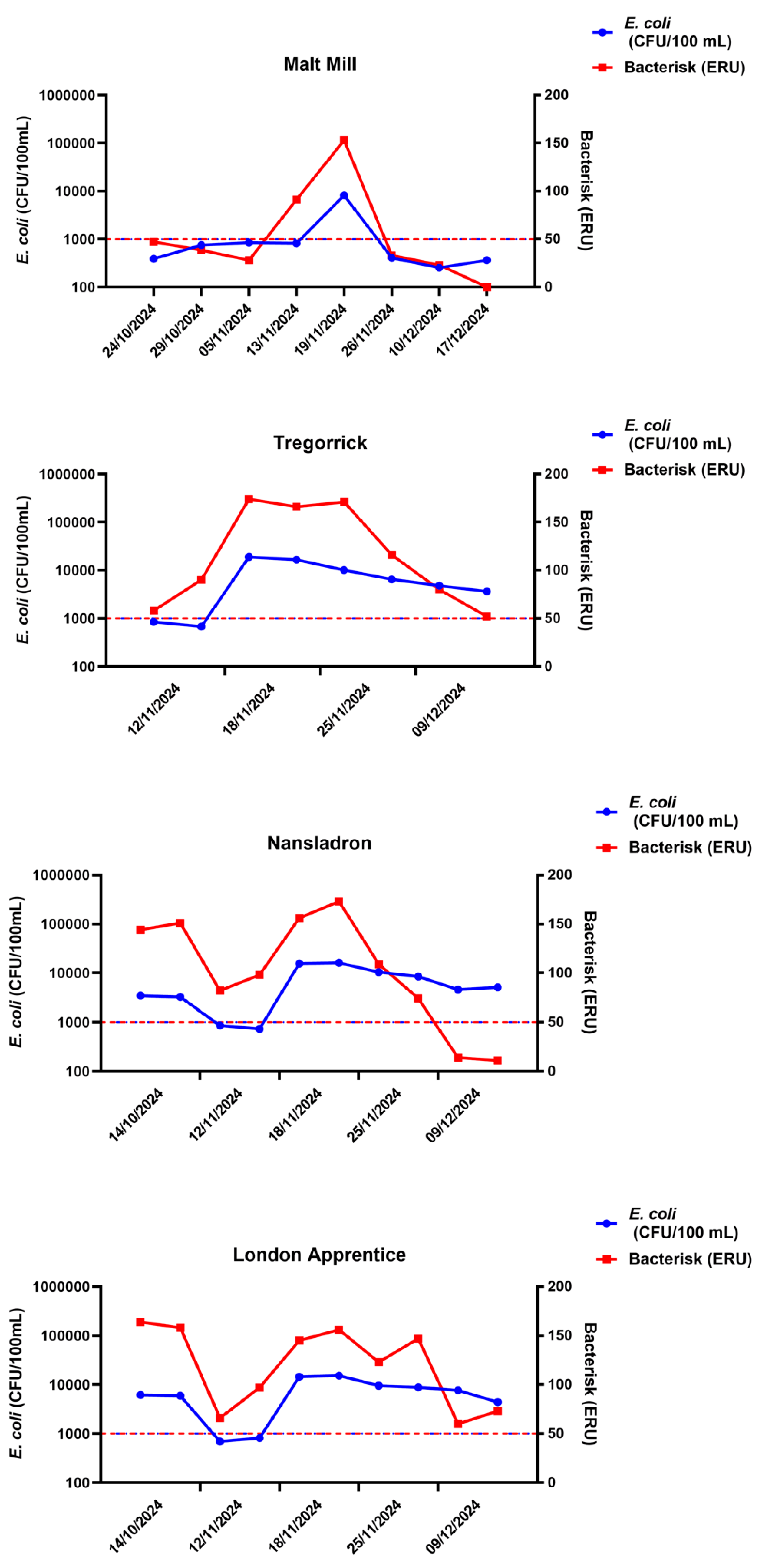

A disadvantage of current methods of water quality monitoring, in addition to the time to result delays, is the restriction to single sites and infrequent sampling. We took samples at different times from the river locations we had sampled for the data in

Figure 1,

Figure 2 and

Figure 3 to determine how water quality might vary with time and location. Results are shown in

Figure 4. It should be noted that water quality assessed by Bacterisk correlates well with

E. coli culture and that the water quality varies greatly on different dates of sampling highlighting the flux in water contamination within rivers.

Discussion

While FIB remain an essential tool for assessing faecal contamination, they are insufficient for evaluating the broader spectrum of waterborne health risks. A more holistic approach to monitoring and managing recreational water quality is needed to ensure the safety of all users and to address the emerging challenges posed by non-faecally transmitted pathogens. Also, the current ISO reference methods of enteric pathogenic bacteria detection are time-consuming, expensive, and often insensitive even in fresh faeces (Liu et al., 2014). Considering that many beach recreational and professional users may suffer from a certain degree of immunological compromise, it is crucial for beach managers to inform the public as thoroughly as possible of any risks associated with exposure to pathogens and opportunists at the beach (Stec et al. 2022). There is thus an urgent need for validated rapid methods to assess bacterial water quality that can be used in situ and cover a broader range of potential pathogens. This will enable proactive measures to be taken in the event of water contamination thereby protecting human health before use. Additionally, the recent water reuse policies regulated, for example, in the European Union by the recast of the Directive (EU) 2024/3019 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 27 November 2024 concerning urban wastewater treatment, aims at the protection of the environment from pathogens and is based on the same slow reference ISO methods. These methods show an incomplete picture and take up time, which sometimes does not exist, when facing an extreme weather event or an environmental disaster assessment (Halcomb et al. 2020).

The current study utilised a rapid bacterial assessment method (Bacterisk) and compared it with E. coli and enterococci culture to determine the bacterial water quality at different inland river and coastal sites in SW England. Bacterisk, which detects the endotoxin present in Gram-negative bacteria, has been used extensively and validated as a useful method to assess the bacterial contamination of coastal recreational waters (Sattar et al., 2022; Good et al., 2024). In the latter reference, we have shown that while Bacterisk assay results could be used to obtain risk groups that differentiate different levels of water quality, we have used it as a binary classification model to determine whether a water source is either polluted (‘poor’) or clean (‘sufficient or better’), based on the regulatory levels of E. coli (EU bathing directive 2006) from thresholds of the ERU data from Bacterisk. Statistical analysis in the present study showed that the uncertainty of measurement for Bacterisk assay gave a 95% confidence in measurements above 25ERU and this level was set as the lower limit of detection for this method. From ROC analysis, compared with E. coli detection by membrane filtration, the assay provides a high sensitivity (92%) but a lower specificity (46%) – this is expected as the assay is not specific for E. coli but will also detect other Gram-negative bacteria including potential pathogens that are abundant in river water.

The present study has shown the applicability of this method for the analysis of recreational freshwaters as was shown previously for coastal waters (Good et al., 2024). In each case, the detection of endotoxin correlates well with conventional FIB E. coli and enterococci and can provide thresholds or cut-offs using the EU bathing water directive guidelines (EU, 2006). Bacterisk results, obtained in 15 minutes in situ, correlated well with conventional membrane filtration culture results. As Bacterisk is not restricted to detect only E. coli or enterococci, the present faecal indicator bacteria, it highlighted the presence of appreciable levels of other Gram-negative bacteria in river water. DNA sequence and qPCR analysis of the river water samples testing positive by Bacterisk endotoxin detection but low for E. coli by culture confirmed the presence of pathogenic bacteria including Pseudomonas aeruginosa and Salmonella typhi (Mena and Gerba, 2009) This shows the advantage of being able to detect bacteria other than the current FIB, as other pathogens might be present in water identified as ‘good or sufficient’ by current regulatory standards. Moreover, evidence is presented for the presence of antimicrobial resistance genes in these water samples, highlighting the need to be able to detect the presence of such bacteria.

In addition to the long time to results for bacterial culture, limitations of the faecal indicator paradigm have long been acknowledged (Field et al., 2007; Stewart et al., 2008). Researchers have identified many challenges and limitations to the effective use of both traditional and alternative faecal indicators to characterize risk, identify sources, and evaluate interventions (Stewart et al., 2013; Fewtrell and Kay 2015). Arguably, one of the most significant limitations is the inconsistent relationships between FIB occurrence, enteric pathogens, and health risks (Fewtrell and Kay, 2015; Korajkic et al., 2018).

The FIB found to correlate with health risks vary widely by site (Griffith et al., 2016). Our data presented here (

Figure 4) show that the levels of bacterial contamination vary greatly by site and by date. The co-occurrence of enteric pathogens and FIB in ambient waters is inconsistent at best (

Korajkic et al., 2018; Wu et al., 2011) and commonly used FIB are known to persist and grow in the environment (Byappanahalli et al., 2003; Oh et al., 2012). Upon introduction to the environment, microbial contaminants are subject to highly variable dispersal and decay processes (Korajkic et al., 2019; Stewart et al., 2013). Pathogens aside, there is also propagation of resistance genes via recreational water; some of which in

E. coli. (Farrell et al., 2023; Leonard et al., 2015; Singh et al., 2022; Han et al.,2022; Li et al., 2022) This study also highlighted the presence of AMR genes in the river samples and Farrell et al. (2023) link recreational water use to an increased carriage of antimicrobial-resistant organisms and Singh et al. (2022) describe how wastewater and natural water systems act as vectors for the spread of ARGs into recreational waters.

The need to differentiate faecal sources in recreational waters led to the emergence of microbial source tracking (MST) methods in the early 2000s, most notably the PCR-based assays that target the 16S rRNA gene in Bacteroides spp. (Bernhard et al., 2000; Dick et al., 2005; Schriewer et al., 2013). Some studies have found strong relationships between the MST markers and enterococci (Schriewer et al 2010), while other studies have found either weak or no relationships (Flood et al., 2010; Santoro and Boehm, 2007), many of which are discussed in a review by Harwood et al. (Harwood et al., 2014). One main factor affecting the relationship between enterococci and the relative strength of different sources of fecal contamination is that enterococci can persist and grow in the environment, which can significantly influence their concentrations in recreational water (Byappanahalli et al., 2012). Enterococci have been shown to persist in fresh water sediments and marine sediments and in some cases, their relative concentrations in sediments are several orders of magnitude higher than that in the overlying water (Anderson et al., 2005; Ferguson et al., 2005).

Previous studies have shown that Bacterisk ERU data also correlates well with enterococci culture data (Good et al., 2024). Results presented here also confirm that Bacterisk ERU data correlate with enterococci data from fresh waters. While enterococci do not contain endotoxin, this relationship probably reflects the decay of E. coli and other Gram-negative bacteria providing endotoxin that is detected while enterococci persist. Thus, detection of endotoxin is a useful indirect proxy for the presence of enterococci.

There is clearly a need for more comprehensive water quality monitoring that extends beyond traditional FIB assessments. Techniques such as nanofluidic quantitative real-time PCR (qPCR) could allow simultaneous detection of multiple FIB, MST, and pathogen genes in under 4 hours (Shahraki et al., 2019). However, the expense, complexity and necessary expertise likely preclude the routine application of such methods for direct pathogen detection. Protecting public health in recreational waters remains an important goal.

While FIB remain an essential tool for assessing faecal contamination, they are insufficient for evaluating the broader spectrum of waterborne health risks. A more holistic approach to monitoring and managing recreational water quality is needed to ensure the safety of all users and to address the emerging challenges posed by non-fecally transmitted pathogens. Results from the current study confirm the applicability of endotoxin detection as a rapid method for the risk assessment of recreational water quality. It is not only rapid (15 minutes) but will alert to the presence of non-FIB pathogens vital to the protection of human health. We suggest that such a method could form a key component in the development of Quantitative microbial risk assessment (QMRA) to provide a comprehensive evaluation of recreational water quality.

Conclusion

Faecal contamination of water continues to be a major public health concern, with new challenges necessitating a renewed urgency in developing rapid and reliable methods to detect contamination and prevent human exposures. Non-faecally transmitted bacteria in recreational waters pose significant health risks to users, underscoring the limitations of relying solely on faecal indicator bacteria (FIB) to assess water quality. Outbreaks linked to these bacterial pathogens often expose gaps in standard monitoring practices, which can leave recreational users unaware of potential dangers. As a result, a water body considered safe based on FIB levels may still harbour significant health risks from environmental bacteria. This study highlights the need for more comprehensive water quality monitoring to extend beyond traditional FIB quantifications. Following the rapid screening and detection especially of ‘non-FIB’, pathogen-specific testing should be incorporated in monitoring programmes, particularly in high-risk recreational waters. Environmental surveillance is also crucial, with factors such as temperature, salinity, and nutrient levels monitored to predict conditions conducive to pathogen proliferation. This study has shown that bacterial endotoxin, measured in near real-time with the Bacterisk assay, is a reliable marker not only of faecal contamination but also of the presence of potential pathogens of non-faecal origin. The portability and ease of use of this assay allows its convenient use to provide data on water quality at different locations and at different times providing a comprehensive surveillance tool.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org.

Acknowledgements

We gratefully acknowledge Kirsty Davies, Surfers Against Sewage UK, Kit Cregan, Friends of the Dart and Rachel salvage, Watershed Investigations for the qPCR data.

References

- Anderson KL, Whitlock JE, Valerie J, Harwood VJ. 2005. Persistence and differential survival of fecal indicator bacteria in subtropical waters and sediments. Appl Environ Microbiol 71:3041–3048. [CrossRef]

- Anwar, M.A.; Choi, S. Gram-negative marine bacteria: Structural features of lipopolysaccharides and their relevance for economically important diseases. Mar. Drugs 2014, 12, 2485–2514. [CrossRef]

- Ayi B. Infections Acquired via Fresh Water: From Lakes to Hot Tubs. Microbiol Spectr. 2015 Dec;3(6). [CrossRef]

- Bernhard AE, Field KG. 2000. A PCR assay to discriminate human and ruminant feces on the basis of host differences in Bacteroides-Prevotella genes encoding 16S rRNA. Appl Environ Microbiol 66:4571–4574. [CrossRef]

- Boehm, A.B., Soller, J.A. (2013). Recreational Water Risk: Pathogens and Fecal Indicators. In: Laws, E. (eds) Environmental Toxicology. Springer, New York, NY.

- Brandão, João et al. “Climate Change Impacts on Microbiota in Beach Sand and Water: Looking Ahead.” International journal of environmental research and public health vol. 19,3 1444. 27 Jan. 2022. [CrossRef]

- Byappanahalli M, Fowler M, Shively D, Whitman R. Ubiquity and persistence of Escherichia coli in a Midwestern coastal stream. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2003;69:4549–4555. [CrossRef]

- Byappanahalli MN, Nevers MB, Korajkic A, Staley ZR, Harwood VJ. 2012. Enterococci in the environment. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev 76:685–706. [CrossRef]

- Dick LK, Simonich MT, Field KG. 2005. Microplate subtractive hybridization to enrich for Bacteroidales genetic markers for fecal source identification. Appl Environ Microbiol 71:3179–3183. [CrossRef]

- European Parliament and Council. (2006). Directive 2006/7/EC concerning the management of bathing water quality and repealing Directive 76/160/EEC. Official Journal of the European Union, L 64, 37–51.

- Evans, T.M.; Schillinger, J.E.; Stuart, D.G. Rapid determination of bacteriological water quality by using imulus lysate. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 1978, 35, 376–382. [CrossRef]

- Farrell, M. L., Chueiri, A., O'Connor, L., Duane, S., Maguire, M., Miliotis, G., Cormican, M., Hooban, B., Leonard, A., Gaze, W. H., Devane, G., Tuohy, A., Burke, L. P., & Morris, D. (2023). Assessing the impact of recreational water use on carriage of antimicrobial resistant organisms. The Science of the total environment, 888, 164201. [CrossRef]

- Farrell, M. L., Chueiri, A., O'Connor, L., Duane, S., Maguire, M., Miliotis, G., Cormican, M., Hooban, B., Leonard, A., Gaze, W. H., Devane, G., Tuohy, A., Burke, L. P., & Morris, D. (2023). Assessing the impact of recreational water use on carriage of antimicrobial resistant organisms. The Science of the total environment, 888, 164201. [CrossRef]

- Ferguson DM, Moore DF, Getrich MA, Zhowandai MH. 2005. Enumeration and speciation of enterococci found in marine and intertidal sediments and coastal water in southern California. J Appl Microbiol 99:598–608. [CrossRef]

- Fewtrell L, Kay D. Recreational Water and Infection: A Review of Recent Findings. Curr Environ Health Rep. 2015 Mar;2(1):85-94. [CrossRef]

- Field KG, Samadpour M. Fecal source tracking, the indicator paradigm, and managing water quality. Water Res. 2007;41:3517–3538. [CrossRef]

- Flood C, Ufnar J, Wang S, Johnson J, Carr M, Ellender R. 2011. Lack of correlation between enterococcal counts and the presence of human specific fecal markers in Mississippi creek and coastal waters. Water Res 45:872–878. [CrossRef]

- Good CR, White A, Brandao J, Jackson S. Endotoxin, a novel biomarker for the rapid risk assessment of faecal contamination of coastal and transitional waters. J Water Health. 2024 Jun;22(6):1044-1052. [CrossRef]

- Griffith JF, Weisberg SB, Arnold BF, Cao Y, Schiff KC, Colford JM. Epidemiologic evaluation of multiple alternate microbial water quality monitoring indicators at three California beaches. Water Res. 2016;94:371–381. [CrossRef]

- Guida, M., Di Onofrio, V., Gallè, F., Gesuele, R., Valeriani, F., Liguori, R., Romano Spica, V., & Liguori, G. (2016). Pseudomonas aeruginosa in Swimming Pool Water: Evidences and Perspectives for a New Control Strategy. International journal of environmental research and public health, 13(9), 919. [CrossRef]

- Haas, C.N.; Meyer, M.A.; Paller, M.S.; Zapkin, M.A. The utility of endotoxins as a surrogate indicator in potable water microbiology. Water Res. 1983, 17, 803–807. [CrossRef]

- Han, Q., Wang, Y., Li, Y., Qiao, W., & Wu, X. (2022). Antimicrobial resistance genes and bacterial communities in recreational coastal waters and adjacent estuaries: Evidence from Qinhuangdao, China. Frontiers in Marine Science, 9, 976438.

- Harwood VJ, Staley C, Badgley BD, Borges K, Korajkic A. 2014. Microbial source tracking markers for detection of fecal contamination in environmental waters: relationships between pathogens and human health outcomes. FEMS Microbiol Rev 38:1–40. [CrossRef]

- Hlavsa MC, Aluko SK, Miller AD, et al. Outbreaks Associated with Treated Recreational Water — United States, 2015–2019. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2021;70:733–738. [CrossRef]

- Holcomb, D. A., & Stewart, J. R. (2020). Microbial Indicators of Fecal Pollution: Recent Progress and Challenges in Assessing Water Quality. Current environmental health reports, 7(3), 311–324. [CrossRef]

- Jeng HC, Sinclair R, Daniels R, Englande AJ. 2005. Survival of Enterococci faecalis in estuarine sediments. Int J Environ Stud 62:283–291. [CrossRef]

- Jorgensen, J.H.; Lee, J.C.; Alexander, G.A.; Wolf, H.W. Comparison of Limulus assay, standard plate count, and total coliform count for microbiological assessment of renovated wastewater. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 1979, 37, 928–931. [CrossRef]

- Korajkic A, McMinn B, Harwood V. Relationships between microbial indicators and pathogens in recreational water settings. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2018;15:2842. [CrossRef]

- Korajkic A, Wanjugi P, Brooks L, Cao Y, Harwood VJ. Persistence and decay of fecal microbiota in aquatic habitats. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev. 2019;83. [CrossRef]

- Leonard, A. F., Zhang, L., Balfour, A. J., Garside, R., & Gaze, W. H. (2015). Human recreational exposure to antibiotic resistant bacteria in coastal bathing waters. Environment international, 82, 92–100. [CrossRef]

- Li, Y., Zhang, C., Mou, X., Zhang, P., Liang, J., & Wang, Z. (2022). Distribution characteristics of antibiotic-resistant bacteria and related genes in urban recreational lakes replenished by different supplementary water sources. Water Science & Technology, 85(4), 1176–1190. [CrossRef]

- Liu J, Kabir F, Manneh J, Lertsethtakarm P, Begum S, Gratz J, et al. Development and assessment of molecular diagnostic tests for 15 enteropathogens causing childhood diarrhoea: a multicentre study. Lancet Infect Dis. 2014;14:716–724. [CrossRef]

- Magnusson,B, T. Näykki, H. Hovind, M. Krysell, E. Sahlin, Handbook for calculation of measurement uncertainty in environmental laboratories, Nordtest Report TR 537 (ed. 4) 2017.

- Mena, K. D., & Gerba, C. P. (2009). Risk assessment of Pseudomonas aeruginosa in water. Reviews of environmental contamination and toxicology, 201, 71–115. [CrossRef]

- Nahm, F. S. 2022 Receiver operating characteristic curve: Overview and practical use for clinicians. Korean Journal of Anesthesiology 75 (1), 25–36. [CrossRef]

- National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine; Health and Medicine Division; Division on Earth and Life Studies; Board on Population Health and Public Health Practice; Board on Life Sciences; Water Science and Technology Board; Committee on Management of Legionella in Water Systems. Management of Legionella in Water Systems. National Academies Press (US), 14 August 2019.

- Oh S, Buddenborg S, Yoder-Himes DR, Tiedje JM, Konstantinidis KT. Genomic diversity of Escherichia isolates from diverse habitats. PLoS One. 2012;7:e47005. [CrossRef]

- Pantazidou, G., Dimitrakopoulou, M. E., Kotsalou, C., Velissari, J., & Vantarakis, A. (2022). Risk analysis of otitis externa (swimmer's ear) in children pool swimmers: A case study from Greece. Water, 14(13), 1983. [CrossRef]

- Rodrigues, C., Cunha, M.Â. Assessment of the microbiological quality of recreational waters: indicators and methods. Euro-Mediterr J Environ Integr 2, 25 (2017). [CrossRef]

- Sampaio, A.; Silva, V.; Poeta, P.; Aonofriesei, F. Vibrio spp.: Life Strategies, Ecology, and Risks in a Changing Environment. Diversity 2022, 14, 97. [CrossRef]

- Santoro AE, Boehm AB. 2007. Frequent occurrence of the human-specific Bacteroides fecal marker at an open coast marine beach: relationship to waves, tides and traditional indicators. Environ Microbiol 9:2038–2049. [CrossRef]

- Sattar, A.A., Good, C.R., Saletes, M.; Brandao, J.; Jackson, S.K. Endotoxin as a Marker for Water Quality. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19. [CrossRef]

- Sattar, A.A.; Abate, W.; Fejer, G.; Bradley, G.; Jackson, S.K. Evaluation of the proinflammatory effects of contaminated bathing water. J. Toxicol. Environ. Health A 2019, 82, 1076–1087. [CrossRef]

- Sattar, A.A.; Jackson, S.K.; Bradley, G. The potential of lipopolysaccharide as a real-time biomarker of bacterial contamination in marine bathing water. J. Water Health 2014, 12, 105–112. [CrossRef]

- Schriewer A, Goodwin KD, Sinigalliano CD, Cox AM, Wanless D, Bartkowiak J, Ebentier DL, Hanley KT, Ervin J, Deering LA, Shanks OC, Peed LA, Meijer WG, Griffith JF, SantoDomingo J, Jay JA, Holden PA, Wuertz S. 2013. Performance evaluation of canine associated Bacteroidales assays in a multi-laboratory comparison study. Water Res 47:6909–6920. [CrossRef]

- Schriewer A, Miller WA, Byrne BA, Miller MA, Oates S, Conrad PA, Hardin D, Yang HH, Chouicha N, Melli A, Jessup D, Dominik C, Wuertz S. 2010. Presence of Bacteroidales as a predictor of pathogens in surface waters of the central California coast. Appl Environ Microbiol 76:5802–5814. [CrossRef]

- Shahraki AH, Heath D, Chaganti SR. Recreational water monitoring: nanofluidic qRT-PCR chip for assessing beach water safety. Environ DNA. 2019. [CrossRef]

- Singh, A., Srivastava, A., Pandey, S., & Shukla, R. (2022). Antimicrobials and antimicrobial resistance genes in the environment: A review on their occurrence and spread through wastewater and natural water. Frontiers in Environmental Science, 10, 830861. [CrossRef]

- Stec, J., Kosikowska, U., Mendrycka, M., Stępień-Pyśniak, D., Niedźwiedzka-Rystwej, P., Bębnowska, D., Hrynkiewicz, R., Ziętara-Wysocka, J., & Grywalska, E. (2022). Opportunistic Pathogens of Recreational Waters with Emphasis on Antimicrobial Resistance-A Possible Subject of Human Health Concern. International journal of environmental research and public health, 19(12), 7308. [CrossRef]

- Stewart JR, Boehm AB, Dubinsky EA, Fong T-T, Goodwin KD, Griffith JF, et al. Recommendations following a multi-laboratory comparison of microbial source tracking methods. Water Res. 2013;47:6829–6838. [CrossRef]

- Stewart JR, Gast RJ, Fujioka RS, Solo-Gabriele HM, Meschke JS, Amaral-Zettler LA, et al. The coastal environment and human health: microbial indicators, pathogens, sentinels and reservoirs. Environ Health. 2008;7:S3. [CrossRef]

- Topić, N., Cenov, A., Jozić, S., Glad, M., Mance, D., Lušić, D., Kapetanović, D., Mance, D. and Vukić Lušić, D. 2021. Staphylococcus aureus-An Additional Parameter of Bathing Water Quality for Crowded Urban Beaches. Int J Environ Res Public Health 18(10), 5234. [CrossRef]

- Wade, T. J., Sams, E., Brenner, K. P., Haugland, R., Chern, E., Beach, M., Wymer, L., Rankin, C. C., Love, D., Li, Q., Noble, R., & Dufour, A. P. (2010). Rapidly measured indicators of recreational water quality and swimming-associated illness at marine beaches: a prospective cohort study. Environmental health: a global access science source, 9, 66. [CrossRef]

- WHO Guidelines on recreational water quality. Volume 1: coastal and fresh waters. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2021.

- Wu J, Long SC, Das D, Dorner SM. Are microbial indicators and pathogens correlated? A statistical analysis of 40 years of research. J Water Health. 2011;9:265. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).