1. Introduction

In the last decades, relative humidity (RH) sensors have earned a lot of attention due to their various applications in areas such as buildings ventilation control, health monitoring (biomedical analysis), food & beverage storage, cosmetics, agriculture, pharmaceuticals, microelectronics (clean rooms for manufacturing and testing electronic devices), automotive (cabin moisture control), weather stations, soft robotics, paper industry, etc. [

1,

2]. The global RH sensors market was valued at USD 1.41 billion in 2024 and is anticipated to grow continuously in the coming years [

3].

Commercially available RH sensors must meet features such as linearity, high sensitivity, reproducibility, low hysteresis, fast response time, long–term stability, simple design, small size, and low cost [

4]. Typically, RH sensors include three main components: a rigid (ceramic, silicone, etc.) or flexible (polyimide, polyethylene terephthalate) substrate, a sensitive material, and peripheral electronic circuits [

5]. Among these components, RH sensing materials play a cardinal role, being the core of an RH detector. The outstanding attributes of an appropriate RH-sensing material are high sensitivity to water vapors, facile and low–cost synthesis, low cross-sensitivity, long operating life, rapid and reversible interaction with water molecules, low drift, uniform and strong adhesion to the surface of the substrate [

6].

Recently, numerous types of materials have been explored as potential RH sensing layers: metal oxide semiconductors [

7,

8], polyelectrolytes [

9,

10], and perovskites [

11,

12]. Carbon-based sensing layers were also employed as RH sensing layers: carbon dots [

13], amorphous carbon [

14], hydrogenated amorphous carbon [

15], carbon nanofibers [

16], nanodiamonds [

17], fullerenes [

18], graphene [

19], graphene oxide [

20], reduced graphene oxide [

21], carbon nanohorns (CNHs), their nanocomposites and nanohybrids [

22,

23,

24], oxidized carbon nano-onions (CNOs) and their nanocomposites [

25].

At the same time, due to their low-cost synthesis, large-scale manufacturing capability, versatile functionalization, low density, structural flexibility, and facile deposition on different substrates, polymers have also received significant attention in the last decades as RH sensing layers. Organic polymers used as hygroscopic materials in RH sensing films include hydrophobic polymers, such as fluorinated polyimide [

26], poly (methyl methacrylate) (PMMA) [

27] and cellulose acetate butyrate [

28], conductive polymers, such as polythiophene [

29] and polyaniline [

30], polymer electrolytes [

31], hydrophilic polymers, like gelatin [

32], polyvinylpyrrolidone (PVP) and polyvinyl alcohol (PVA) [

33]. Finally, biopolymers have also gained increased interest for being used within RH sensing layers due to their excellent biodegradability and non-toxicity. Examples of such materials include polylactic/glycolic acid [

34], chitosan [

35], polyglutamic acid and polylysine [

36].

However, RH sensing layers based only on polymers typically exhibit drawbacks, such as low RH sensitivity, substantial backbone mechanical dissolution, restricting temperature range, and long response time [

37]. Consequently, many polymer-based nanocomposites and nanohybrids have been designed, focusing on optimizing the physico-chemical properties of polymers and improving their water molecules detection capability. Polymer–metal nanohybrids [

38], polymer-polymer nanocomposites [

39], metal oxide semiconducting-polymer [

40], and metal-organic framework-polymer [

41] are just a few examples of nanocomposite materials that have been used as sensing layers for RH monitoring.

At the same time, nanocomposites and nanohybrids, including polymers and nanocarbon materials, have also been demonstrated as RH sensing films [

42]. Several examples of such nanocomposites and nanohybrids and their associated sensing technologies are presented in

Table 1.

This study presents the synthesis and characterization of RH sensing films based on a nanocomposite comprising CNOs and PVA at 1:1 and 2:1 w/w ratios. The room temperature (RT) RH sensing response of a chemiresistive sensor using the RH synthesized sensing layer is investigated. This is the first time a nanocomposite based on CNOs and PVA is reportedly used for RH sensing. The experimental RH detection data is analyzed and compared with the previously published RH sensing results measured on RH detectors employing, as sensing layers, nanocomposites comprising CNHox - PVP, CNHox - PVA, and MWCNTs – PVA.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

CNOs (

Figure 1a) were procured from Shanghai Epoch Material Co. Ltd., while PVA powder (87-90% hydrolyzed, average mol wt 30,000-70,000 – (

Figure 1b) was acquired from Sigma Aldrich (Bucharest, Romania). The chemicals were of the highest available grade and were used as received without additional purification.

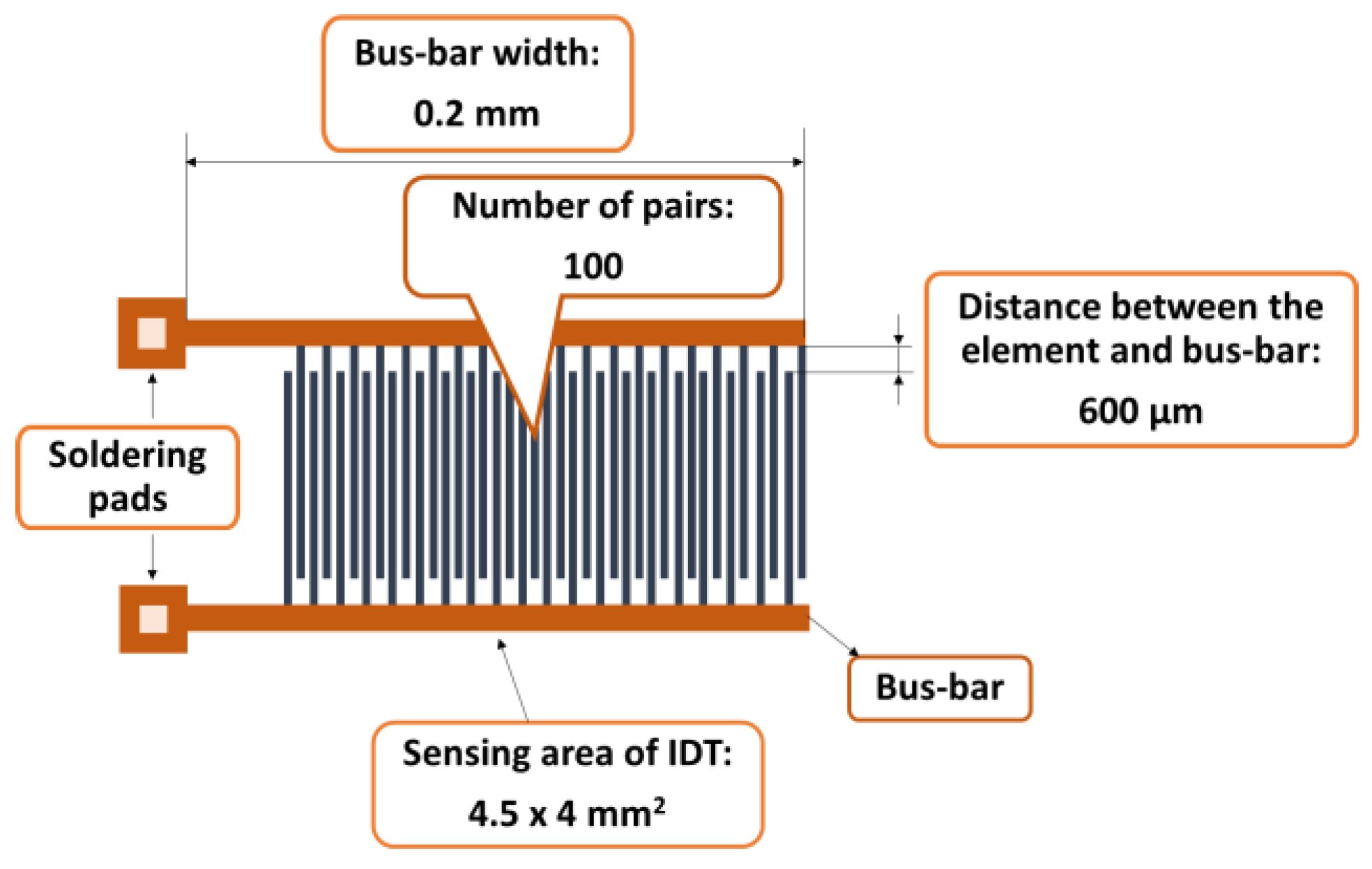

2.2. Synthesis of the Nanocarbon Composite Sensing Layer and Experimental Set-Up

The synthesis of the sensitive film based on the CNOs-PVA nanocomposite at a 1/1 mass ratio started with preparing the PVA solution. The hydrophilic polymer solution was prepared by gradually dissolving 6 mg of PVA in 12 ml of deionized water for 6 hours at 90

0C in an ultrasonic bath (FS20D Fisher Scientific, Germany), working at 42 kHz (70 W output power). CNOs (6 mg) were dispersed in a clear water-based PVA solution and subjected to intensive stirring in an ultrasonic bath for 6 hours, maintaining the temperature at 50-60

0C. The dispersion was drop-cast over a metallic interdigitated (IDT) structure while the contact area was masked [

56]. The IDT dual-comb structure was manufactured on a Si substrate (470 µm thickness), covered by a SiO

2 layer (1µm thickness) (

Figure 2). The sensing film was heated at 70

0C, for 2 hours in vacuum, and, finally, the whole RH sensing device was dried at 70

0C for 2 hours [

57]. The synthesis of the sensitive film based on the CNOs-PVA nanocomposite at 2/1 mass ratio was performed similarly, except for the CNO/ PVA mass ratio.

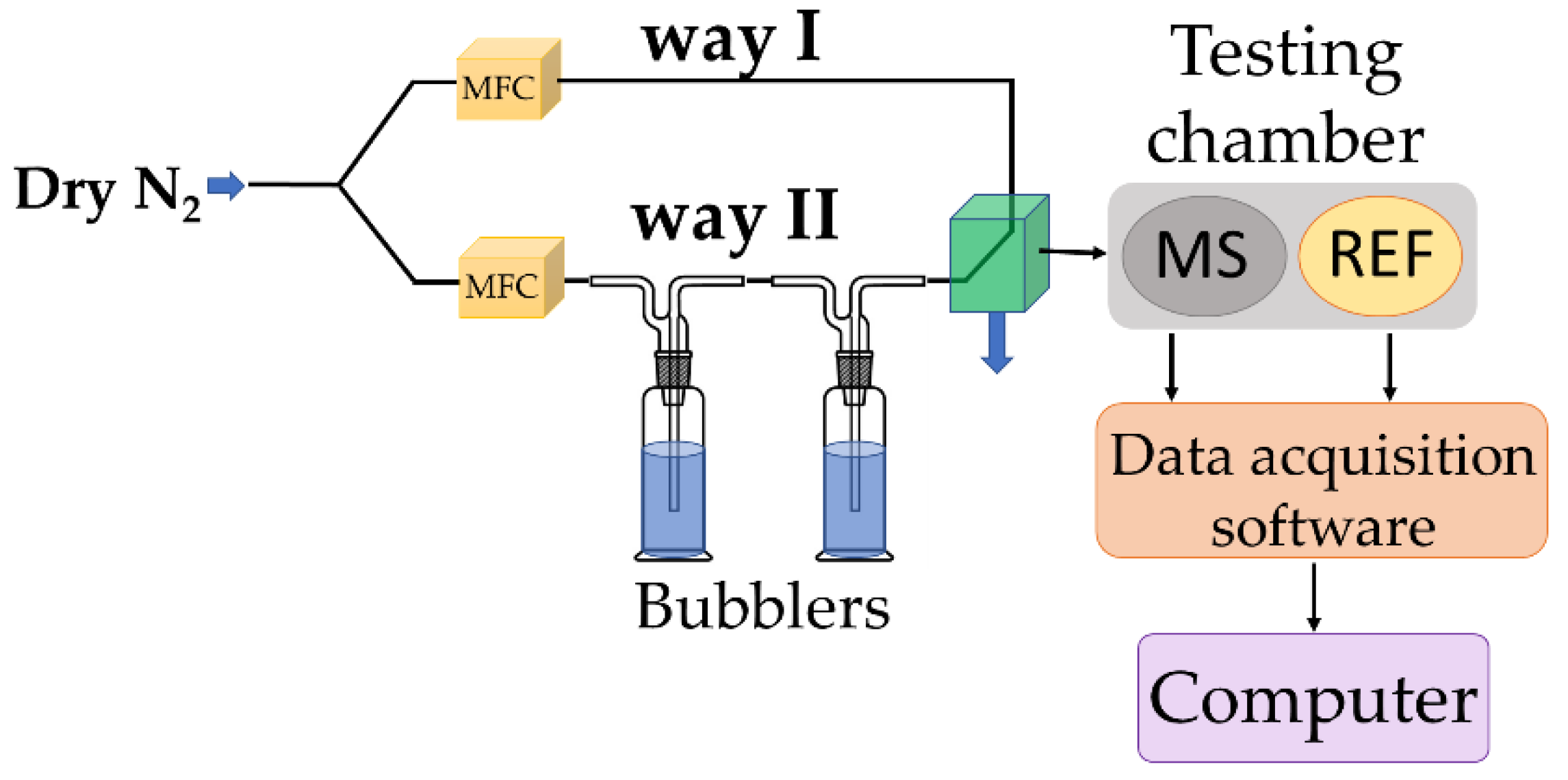

To assess its RH monitoring performance, the chemiresistive manufactured sensor (MS), utilizing, for the first time, the CNOs-PVA nanocomposite (in 1:1 and 2:1 w/w ratios) as RH sensing film, was tested in parallel with a capacitive, commercially available, RH sensor (REF), which acted as a reference device. Both devices were placed inside a testing box depicted in

Figure 3.

In the proposed experimental framework, dry nitrogen was purged through bubblers containing demineralized water to achieve RH values within the 5%–95% range. Digital mass flow controllers (MFC) were utilized to mix dry and wet nitrogen in several ratios. Before starting the experiments, the devices were exposed to dry nitrogen for 6 hours to achieve an almost free-moisture environment. MS and REF were positioned near the gas inlet to be subject to quasi-identical testing environments. Current variations were induced using a Keithley 6620 current source. The output voltage was recorded, and the electrical resistance was computed with a PicoLog data logger. The total electrical power consumption of MS was less than 2 mW, its low power consumption being a significant advantage of this type of sensor.

3. Results

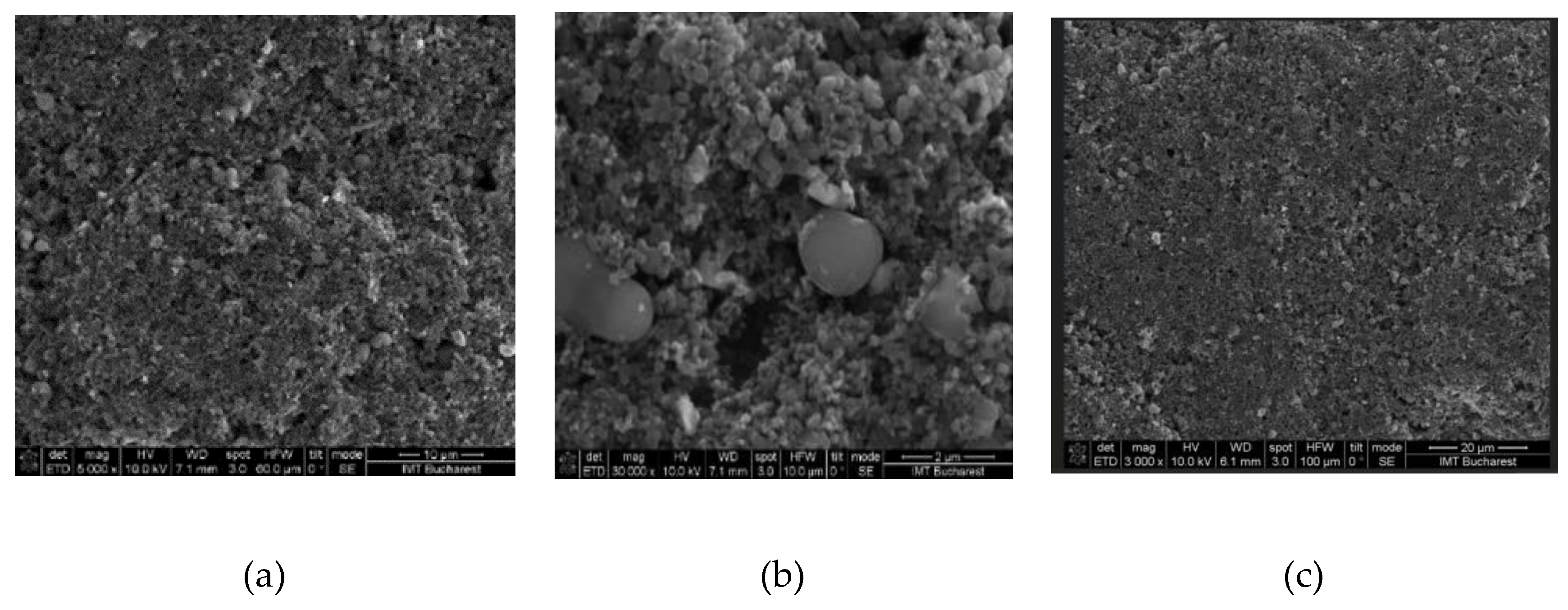

3.1. Surface Topography

The surface topography of the sensing films based on the CNOs-PVA nanocomposite was investigated by scanning electron microscopy (SEM). The images showed a relatively inhomogeneous CNOs PVA film within islands of agglomerated CNOs nanoparticles (

Figure 4).

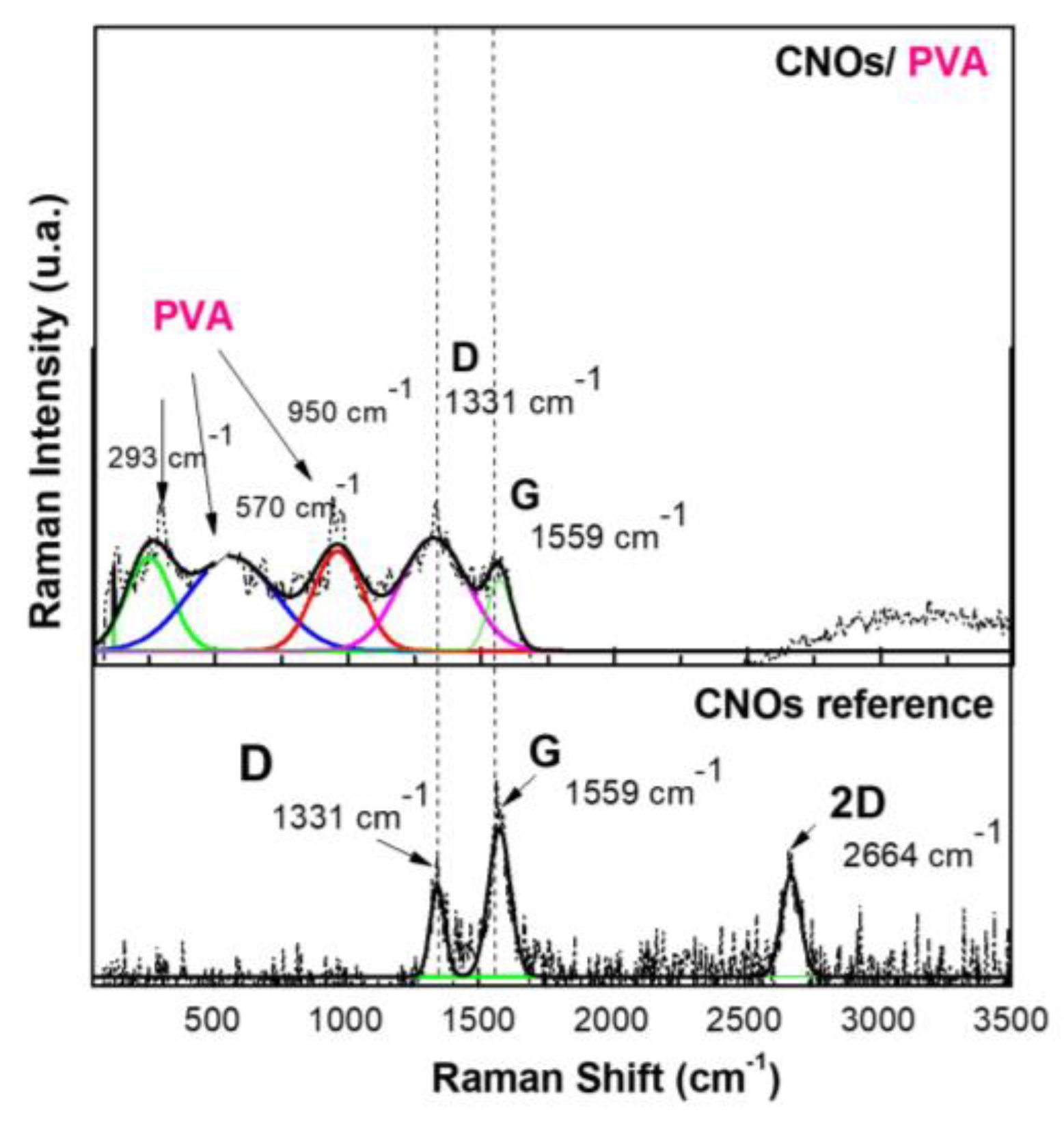

3.2. Raman Spectroscopy

Raman spectroscopy measurements were carried out at RT using a WiTec Raman spectrometer (Alpha-SNOM 300 S, WiTec GmbH, Germany) with an excitation wavelength of 532 nm. A diode-pumped solid-state laser emitting at 532 nm and delivering a maximum power of 145 mW was directed onto the sample through an objective lens with a 6 mm working distance, integrated into a Thorlabs MY100X-806 microscope. The laser beam was concentrated into a spot size of nearly 1.0 µm.

The Raman spectra (

Figure 5) were acquired with an exposure time of 20 seconds, and the scattered light was gathered in backscattering geometry using the same objective lens. A 600 grooves/mm diffraction grating was employed for spectral resolution. The Raman system was calibrated using the 520 cm⁻¹ Raman peak of a silicon wafer. The entire process, including spectral acquisition, data processing, and analysis, was managed through WiTec Project Five software.

The Raman spectrum of CNOs displays two distinct bands, between 1,300 and 1,600 cm⁻¹, attributed to the D mode (1,331 cm⁻¹) and G mode (1,559 cm⁻¹) [

58]. These vibrational features are commonly observed in carbon-based materials and provide crucial insights into their structural characteristics and degree of order.

The G mode at 1559 cm⁻¹ corresponds to C–C bond stretching vibrations within the sp²-hybridized layers of the carbon framework. This band is linked to the E₂g vibrational mode of sp²-hybridized carbon, indicating well-ordered carbon structures. In the CNOs-PVA nanocomposite, the presence of the G band signifies the existence of carbon layers arranged in a spherical pattern.

Conversely, the D mode at 1331 cm⁻¹ is associated with structural defects in the sp² carbon lattice. This mode originates from the breathing vibrations of sp² carbon rings and is influenced by defects, impurities, dopants, or functional groups within the material. In CNOs-PVA, the D band intensity is affected by structural imperfections within the nanocomposite matrix. An increase in D band intensity reflects a higher level of disorder in the carbon network.

The intensity ratio of the D and G bands (I_D/I_G) serves as a quantitative measure of defect density and structural disorder. For CNO_reference, this ratio is I_D/I_G = 0.558, whereas for CNO_PVA, it rises to I_D/I_G = 1.126. The doubling of this ratio indicates a notable increase in structural defects and disorder, which is attributed to the incorporation of PVA within the composite matrix.

At lower frequencies, the Raman spectrum exhibits vibrational modes corresponding to Polyvinyl Alcohol (PVA), specifically C–H, C–O, and C–C bonds. The spectral peak at 950 cm⁻¹ is attributed to C–O stretching vibrations, while the band at 570 cm⁻¹ corresponds to out-of-plane hydroxyl bending vibrations. Additionally, peaks detected within the 100–300 cm⁻¹ range are linked to C–C bond stretching and C–H bending modes.

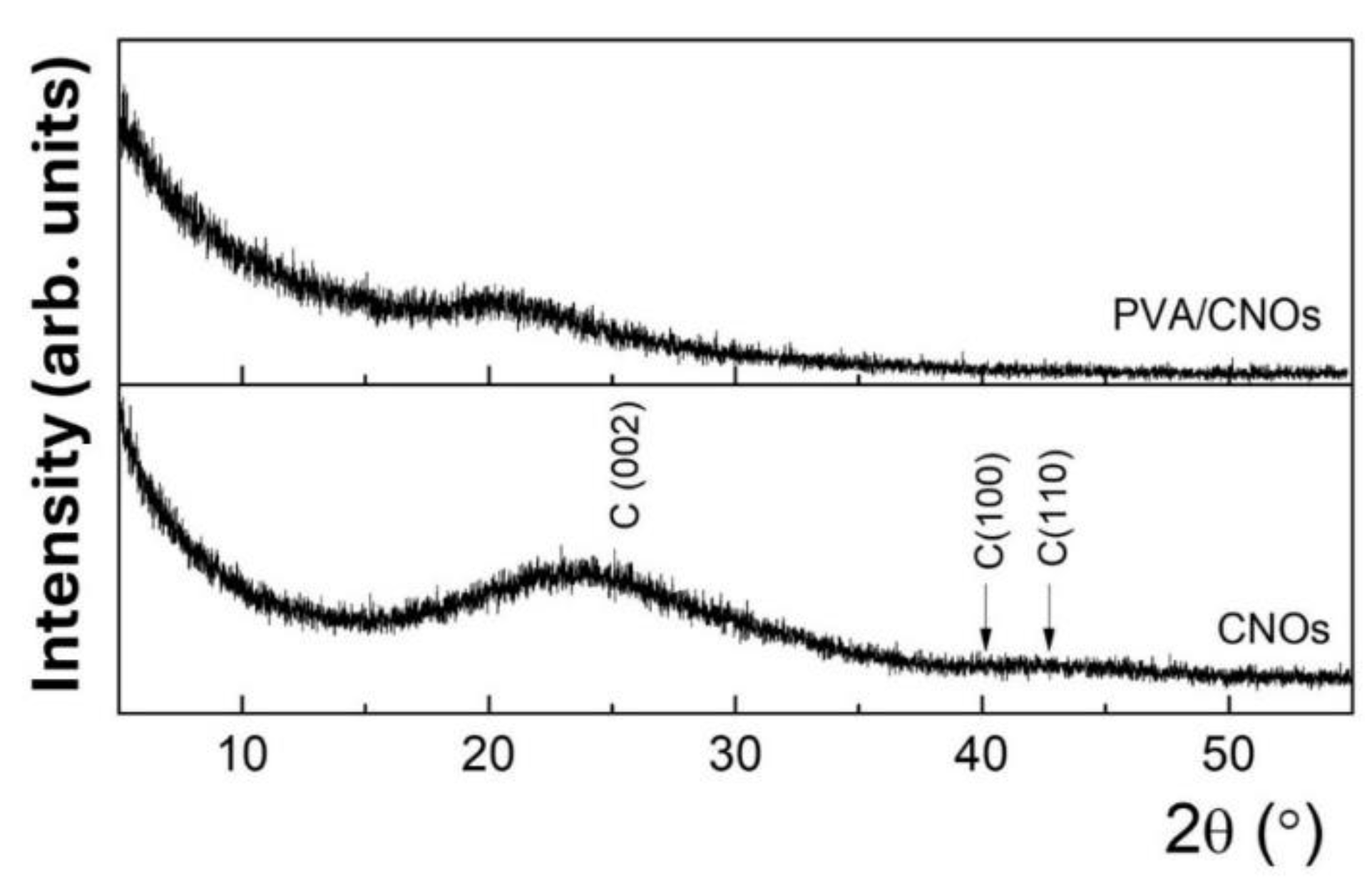

3.3. X-ray Diffraction Results

The RH sensing layer's morphology and crystal structure were also explored by employing X-ray diffraction (XRD). In this respect, an X-ray diffractometer with a nominal power of 9 kW (Rigaku SmartLab) was used. A θ/2θ configuration was utilized to analyze the CNOs pristine powder and the CNOs-PVA nanocomposite deposited on the Si substrate. The latter sample was examined at a low incidence angle, i.e., small X-ray penetration depth, to minimize the signal from the Si substrate.

Figure 6 shows the diffractograms for the CNOs powder and the CNOs-PVA nanocomposite deposited on the Si substrate. The characteristic broad feature between 15 and 30

0, centered at 23.2

0, corresponds to the (0 0 2) plane of the graphitic carbon peak. The broadening in the (0 0 2) peak is typical for the CNOs [

59,

60]. Additionally, the broad overlapped features around 42

0 and 45°, attributed to (100) and (110), emphasize the disordered structure of the graphene rings within the CNOs, in agreement with the rather reduced height of the G peak with respect to the D peak from the Raman spectra of CNOs-PVA nanocomposite.

These patterns agree with other studies on the microstructure of CNO-based composites [

25]. For CNOs-PVA nanocomposite deposited on a Si substrate, only a low-intensity band is observed, which is correlated with the semi-crystalline nature of pure PVA [

61].

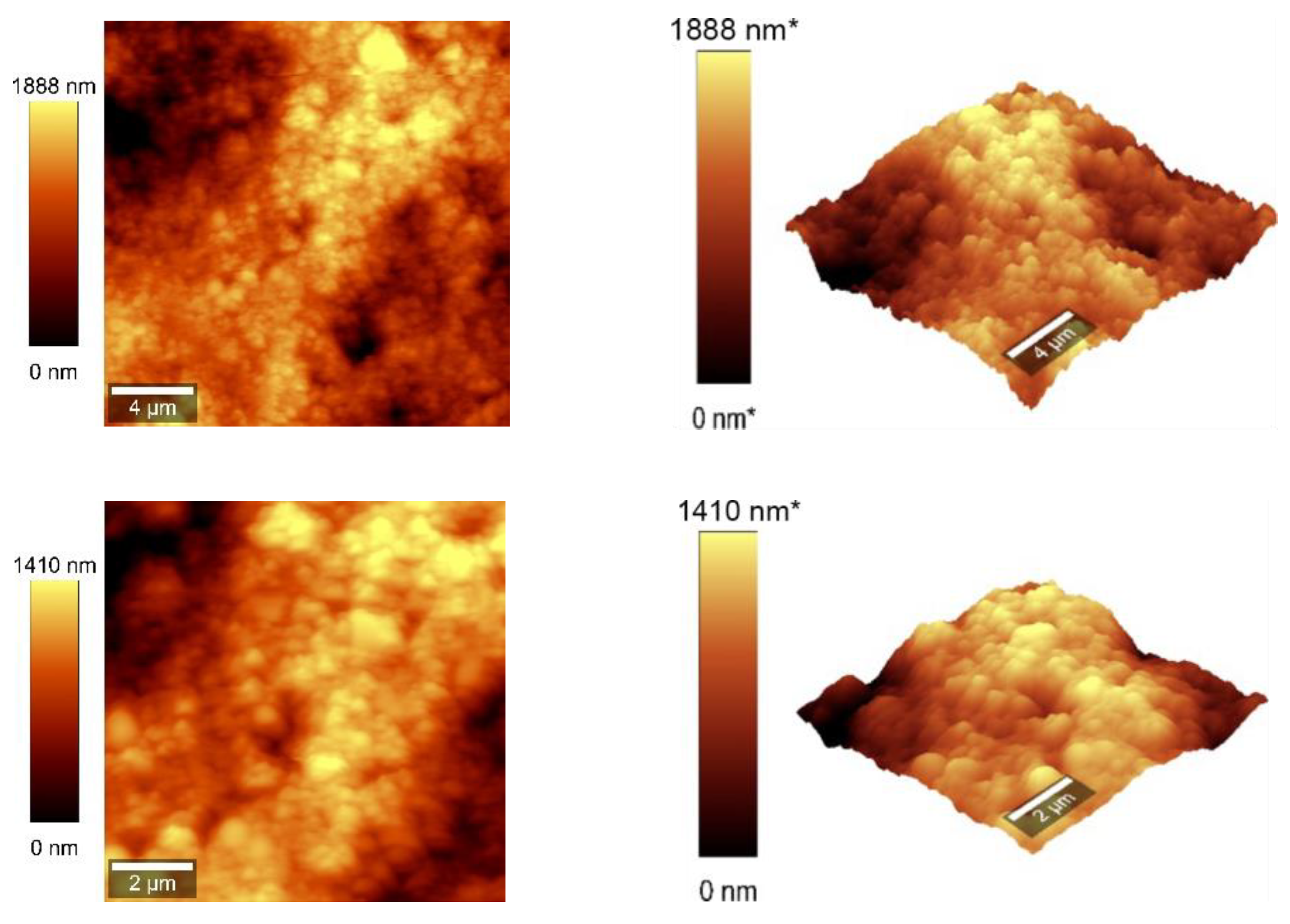

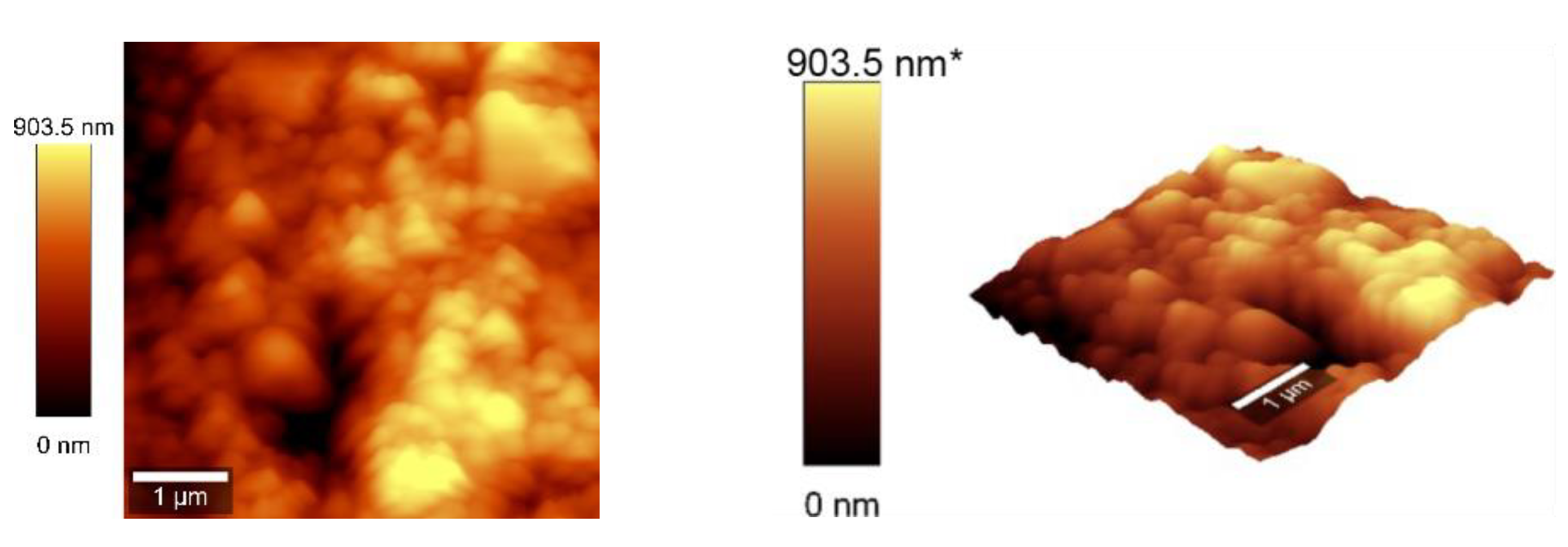

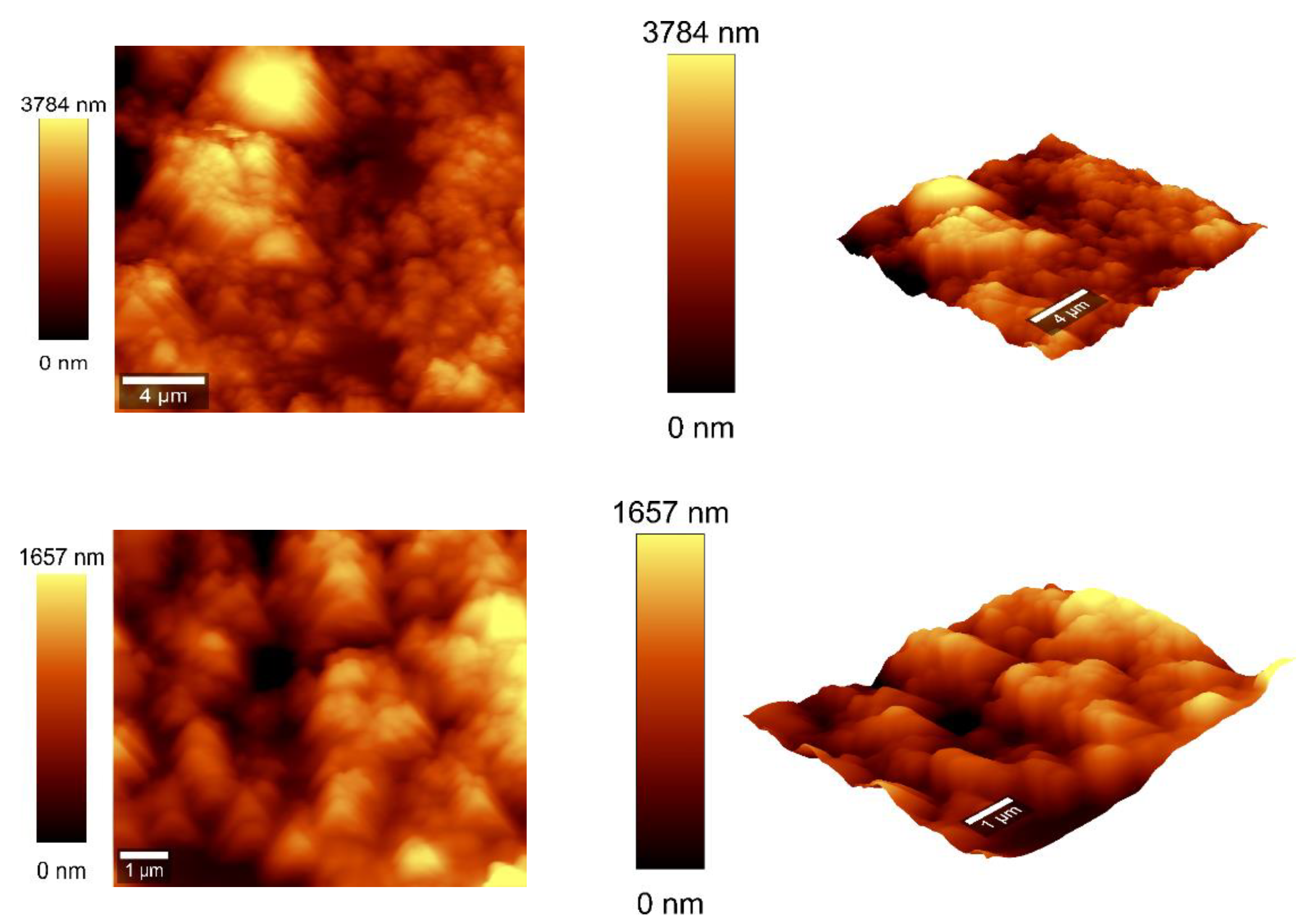

3.4. AFM Measurements

Atomic force microscopy (AFM) analysis (

Figure 7 and

Figure 8) was conducted using a WITec Scanning Near-field Optical Microscope operating in the tapping mode for CNOs-PVA layer with both 1/1 and 2/1 w/w ratios. The analysis employed a Si

3N

4 AFM cantilever with a length of 125 µm, a force constant of 40 N/m, and a frequency of 300 kHz. The surface parameters were calculated using Project FIVE 5.0 Witec software.

The values of the roughness parameters for CNOs-PVA 1/1 w/w were SDQ (Root mean square gradient) = 0.759 nm, SA (Arithmetic average) = 353.83 nm and SQ (Root mean square average) = 435.40 nm. The high values of SA and SQ roughness parameters indicate that the surface was not smooth and had a pronounced topography. The moderate value of SDQ suggests that, while the surface was rough, the slopes were not excessively steep, implying that the roughness distribution was relatively uniform rather than jagged or highly irregular.

The values for the roughness parameters for CNOs-PVA 2/1 w/w were SDQ =1.12 nm, SA = 366.35 nm, and SQ = 461.59 nm.

3.5. RH Monitoring Capability

The RT RH sensing performance of MS using CNOs-PVA as sensing layer, at 1:1 and 2:1 w/w ratio, was explored by applying a continuous electric current between the interdigitated electrodes and measuring the voltage as the RH was varied from 5% to 95%.

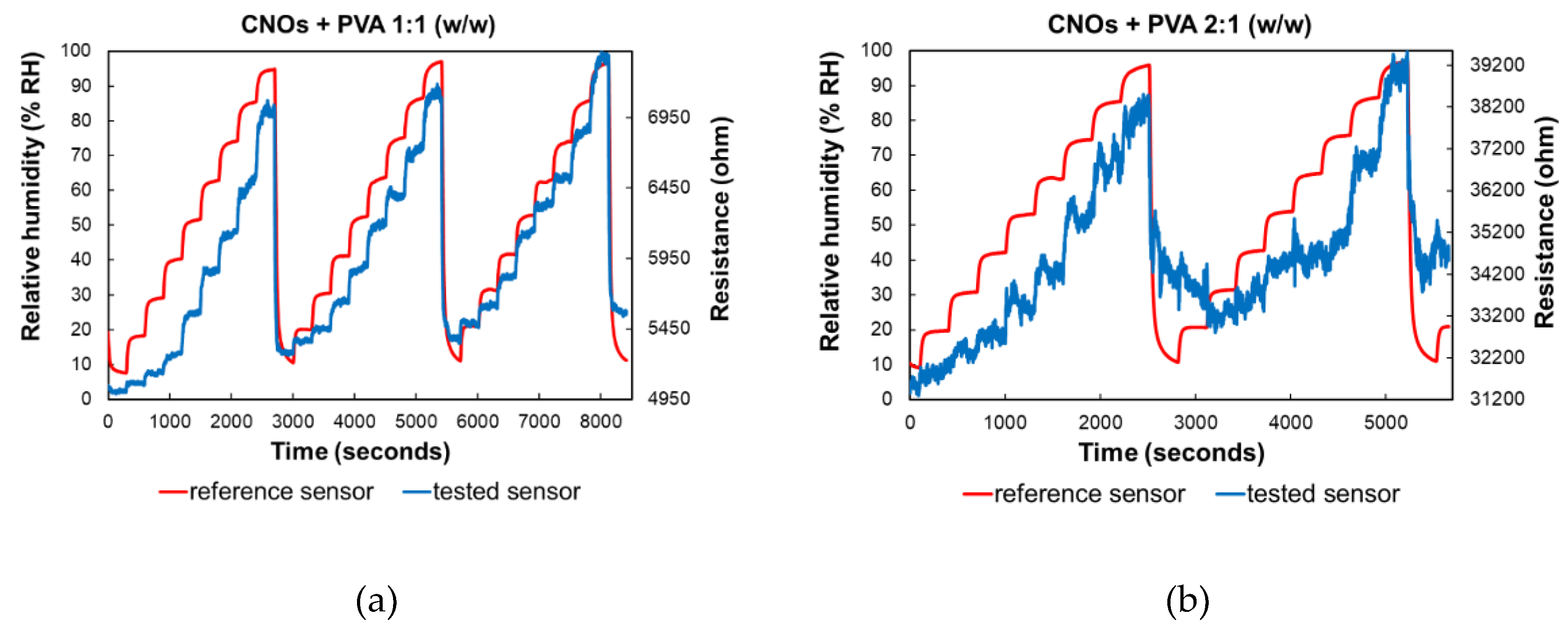

As depicted in

Figure 9, altering the ratio between CNOs and PVA significantly affects the resistance variation with RH in the test chamber. For the sensing layer with a higher CNOs content, the resistance exhibits continuous fluctuations across a wide range, even when the humidity levels remain relatively stable.

Significant differences in resistance variation were observed when comparing the two RH sensing layers. The sensor employing CNOs-PVA at 1:1 (w/w) exhibited resistance values between 5 and 7.7 kΩ when varying RH in the 5%–95% range, whereas the structure using CNOs-PVA at 2:1 (w/w) showed a much higher resistance variation, ranging from 31 to 40 kΩ, under the same RH variation conditions (

Figure 9).

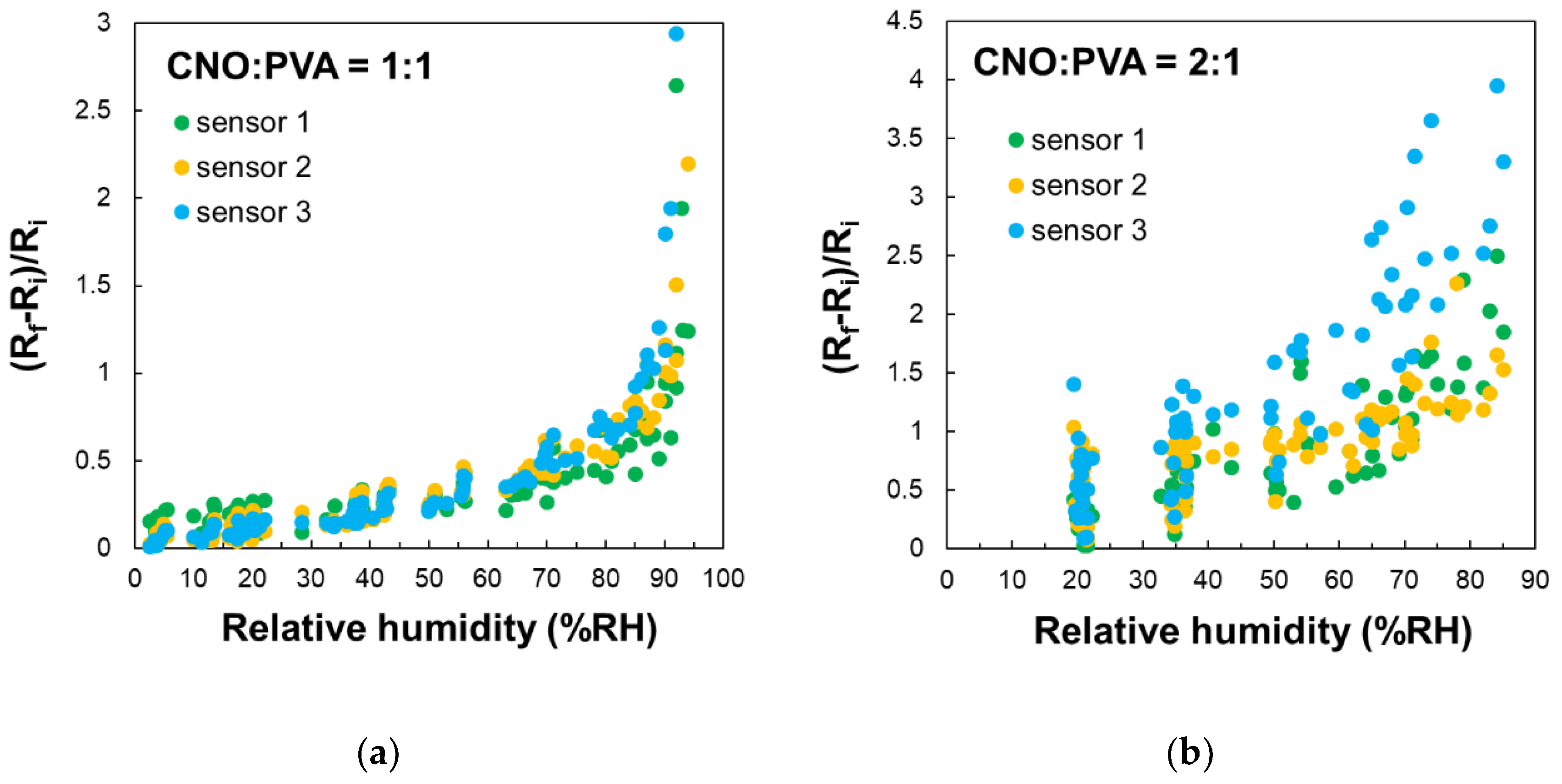

The stability of the proposed RH sensing materials was evaluated by measuring the substrate resistance over multiple operating cycles for three identically manufactured sensors, which were subjected to repeated RH variations across the 5%-95% range.

Figure 10 presents the variation with RH of the ratio (Ri - Rf) / Ri. The results indicate that the CNOs-PVA 1:1 (w/w) sensing layer demonstrates significantly larger stability compared to the CNOs-PVA 2:1 (w/w) sensing layer.

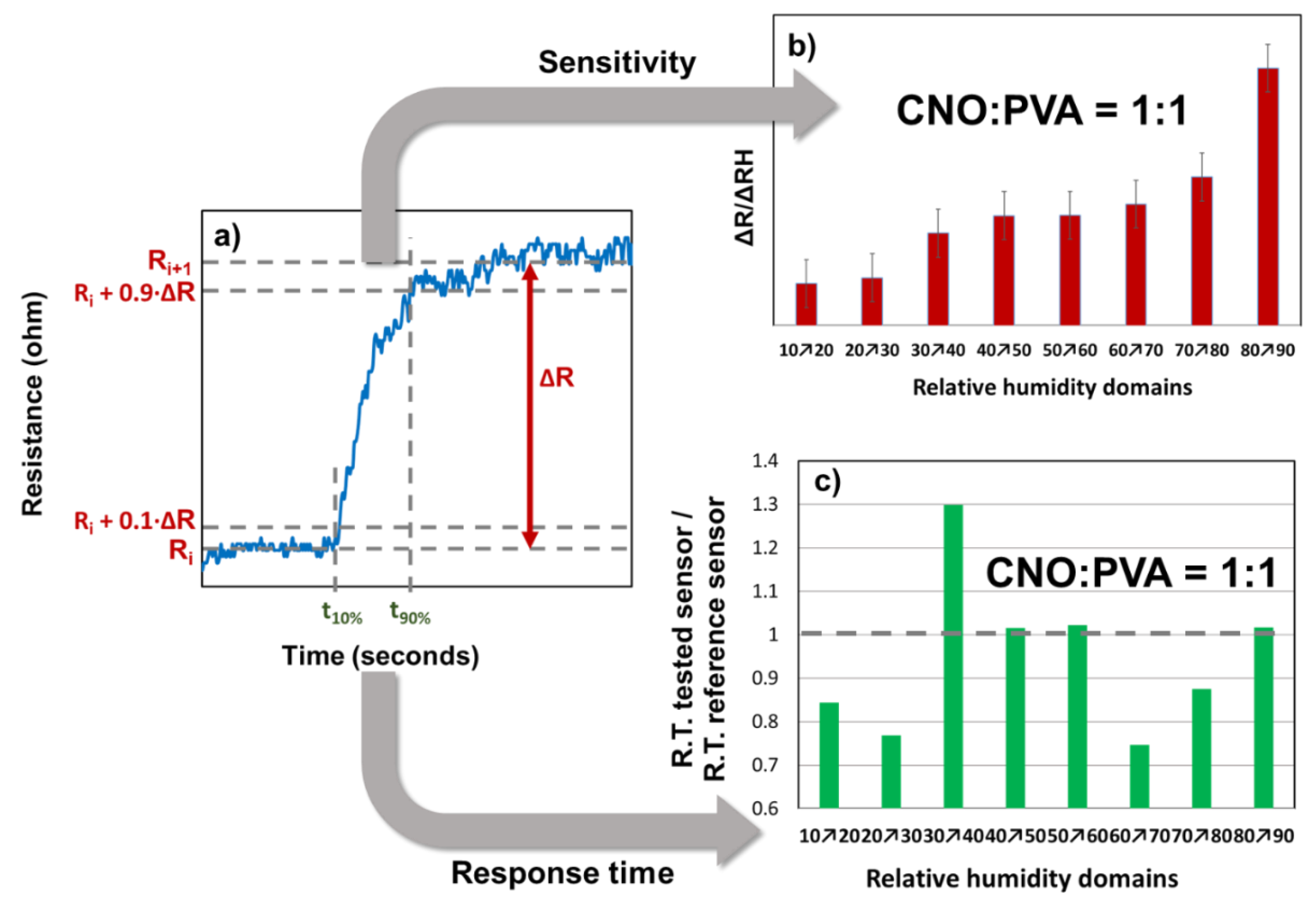

The response time and sensitivity analysis were conducted only for the sensor with the CNOs-PVA at 1:1 (w/w) sensing layer, as presented in

Figure 11.

From the graph of the stepwise evolution of the sensor resistance, the response times were calculated according to the following formula:

For each RH step, the sensitivity was calculated as follows:

The variation of ΔR/ΔRH for different RH steps indicated that the CNOs-PVA layer at 1:1 (w/w) exhibited distinct behavior at RH levels above 80%. The t

90% and t

10% values were determined for each RH step, as shown in

Figure 9. The response times of MS ranged from 40 to 100 seconds, with the longest times recorded when RH decreased to 70%, a trend also observed for REF. The ratio of the response times (

Figure 11 c) demonstrated that MS employing CNOs-PVA at 1:1 (w/w) generally performed comparably or better than REF, except for RH between 30% and 40%, where MS was slower than REF for all three cycles of testing. The recovery time of MS during the RH drop from 95% to 10% was approximately 30 seconds, which was half the recovery time of REF (~65 seconds).

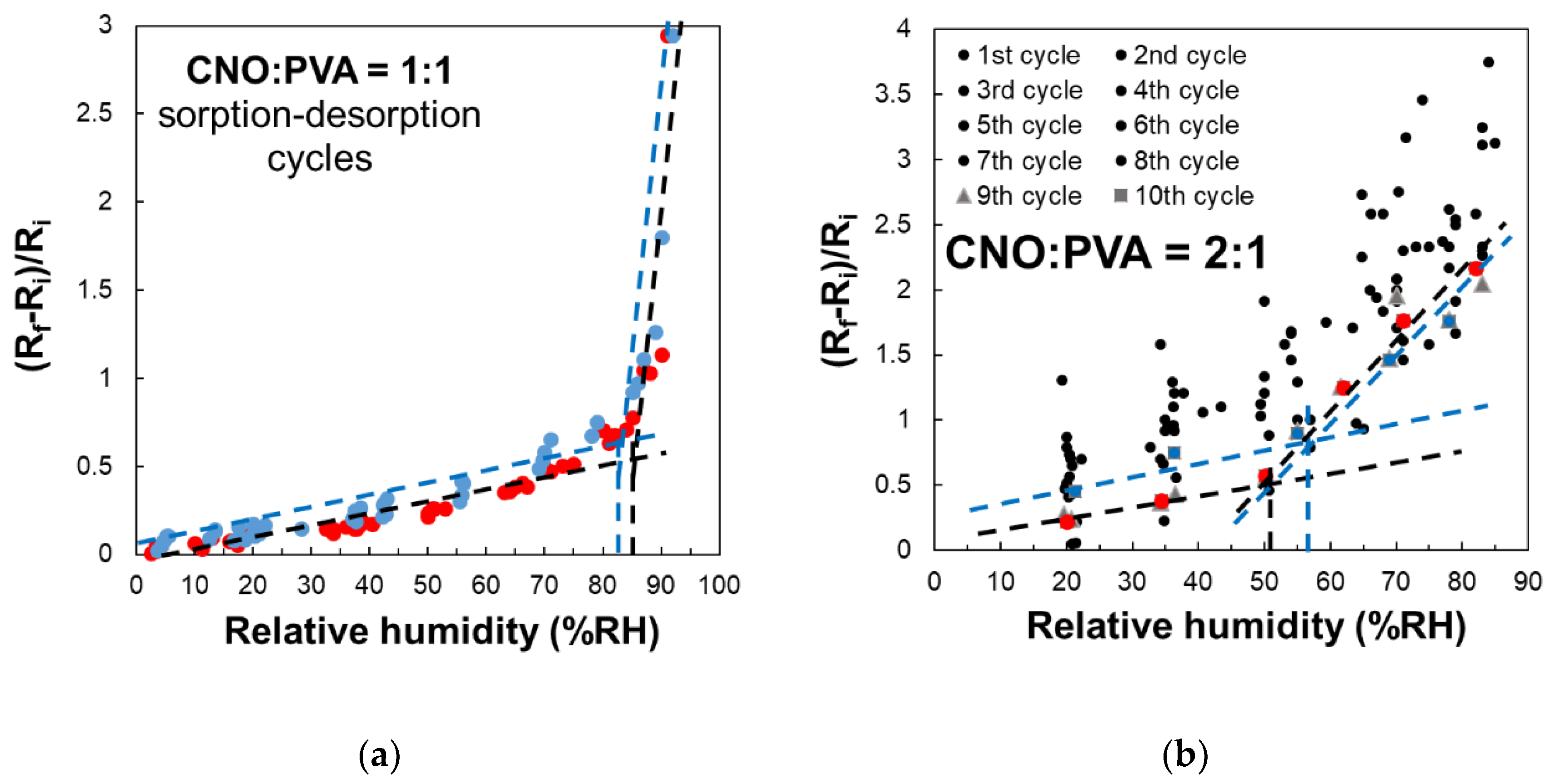

A key characteristic of the sensor employing CNOs-PVA at 1:1 (w/w) is the presence of an inflection point in the evolution of the (Rf - Ri) / Ri factor in the 80 – 85% RH domain, as shown in

Figure 12. This behavior is observed during both the water molecules sorption and desorption stages.

In the case CNOs-PVA at 1:1 (w/w) ratio, RH monitoring was performed during successive operating cycles (

Figure 12a). The results emphasize that the resistance of MS increased with RH over the entire RH range considered. For RH below 85%, the resistance variation with RH was linear, with a moderate slope, while for RH values above the 85% threshold, the slope got significantly steeper, thus a significantly higher sensitivity was measured. The response of MS was reproducible, the variation of the resistance and the differences between the sorption and desorption curves being around ± 5%.

In the case of the CNOs-PVA at 2:1 (w/w) sensing layer, RH monitoring was performed for 10 operating cycles (

Figure 12b). In this case, the sensing layer based stabilized significantly slower compared to the CNOs-PVA at 1:1 (w/w) sensing layer. The adsorption curve approached the desorption curve only after 8 adsorption-desorption cycles. At the same time, the inflection point during adsorption showed at approximately RH = 50.5% (black line), compared to the one for desorption which occurred at approximately RH = 56.5% (blue line) (

Figure 12b). The inflection points are determined only for operating cycles 9 (red square) and 10 (blue square), since during the first 8 cycles there are too large differences between the desorption and adsorption curves and between cycles. A possible explanation for the much significantly slower stabilization of the sensing layer and increased hysteresis in the case of the sensing layer based on CNOs-PVA at 2:1 (w/w) ratio may rely on the fact that an increased percent of nanocarbon material in the matrix nanocomposite yielded a less homogeneous RH sensing layer, with more “islands” of agglomerated nanocarbon particles surrounded by hydrophilic polymer.

The lower values of the electrical resistance measured at RT for the RH detector based on the sensing layer employing CNOs-PVA at 2:1 w/w ratio compared to the device using CNOs-PVA at 1:1 w/w ratio can also be explained by the higher percentage of conductive nanocarbon material. For both sensing films (CNOs-PVA 2/1 and 1/1 (w/w) ratio, respectively), the CNOs concentration is above the percolation threshold of the nanocarbon material in the hydrophilic matrix of PVA. Therefore, electrically percolating paths between the two metal electrodes of the proposed RH sensor make it easy to measure electrical resistance.

4. Discussion

The experimental RH detection capabilities of the proposed MS structure can be understood by considering several distinct RH sensing mechanisms.

The first RH detection mechanism relies on CNOs being p-type semiconductors [

62]. Once the contact between CNOs and water molecules occurs, the latter donate their electrons pair, thus decreasing the concentration of holes in the CNOs structure. As RH level increases, holes concentration in CNOs decreases and, thus, the CNOs-PVA nanocomposites become less conductive.

Another RH sensing mechanism is related to the interaction between CNOs and water which can be explained considering the hard-soft acid-base (HSAB) principle [

63]. This concept is widely used in nanotechnology to explain the stability of compounds, reaction mechanisms and plausible interactions [

64]. Positively charged carriers found in pristine CNOs are quite similar to a hard acid, while water molecules, through their electron pairs, can be assimilated to hard bases. The HSAB theory principle states that between hard acids and hard bases chemical interaction is possible. Therefore, the chemical interaction between CNOs and water seems to be feasible.

A third RH sensing mechanism which can be considered is the one proposed by Dhonge et al. [

65]. According to these authors, for RH > 27.9%, CNOs may change their semiconducting behavior, switching from p-type to n-type. In order to explain the phenomenon, the authors proposed the mechanism described by the reactions below:

V- and V2- represent vacancies which can trap one or two electrons within the CNOs. The electrons generated in the absorption process depicted above neutralize the positive charge carriers from the CNOs. Moreover, according to Dhonge et al., as RH increases, the concentration of electrons increases, leading to changing CNOs to n-type semiconducting behavior. Should this process occur, a decrease of the sensor resistance while increasing RH should be experimentally measured. However, this type of behavior was not measured for the MS investigated in this study.

A fourth RH sensing mechanism considers the self-ionization of water into protons and hydroxyl anions on the surface of the nanocarbon structure, occurring at high RH levels. These ions produced by the dissociation of water (and proton hoping from one water molecule to another) may increase the overall electrical conductivity of the thin sensing film. This fourth sensing mechanism seems plausible, but, overall, it is clear that proton conduction cannot play a significant role in the resistive RH monitoring.

Given the above discussed RH sensing mechanism, lowering CNOs holes concentration in interaction with water molecules seems to be the most significant RH sensing mechanism for RH < 82% (when employing CNOs-PVA at 1:1 (w/w) as RH sensing layer) and for RH < 50% (when employing CNOs-PVA at 2:1 (w/w) as RH sensing layer).

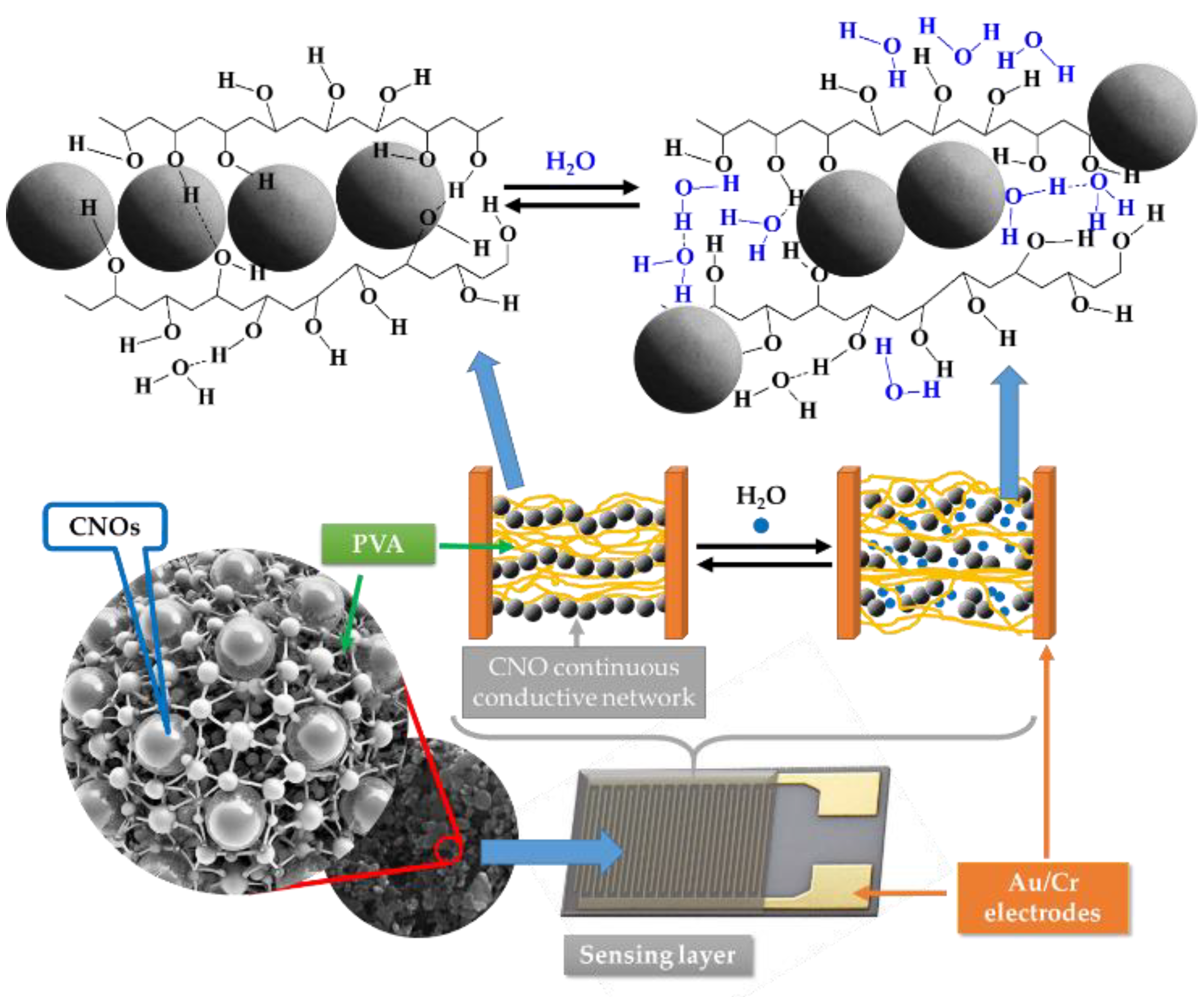

However, a significantly more substantial decrease in the electrical conductivity of the sensing film with the RH was measured for RH higher than the above listed threshold values. This might be due to a fifth RH sensing mechanism. PVA is a dielectric polymer with hydrophilic properties. When RH is low, the CNOs-PVA nanocomposites absorbs a tiny quantity of moisture, and the contact points between CNOs do not change significantly. However, at higher RH levels, the adsorbed water can cause a volumetric expansion of the polymer (swelling) by disrupting many of the hydrogen bonds established between its alcoholic groups (

Figure 14). Consequently, the contact points between CNOs decrease rapidly, percolating pathways are strongly diminished, and CNOs-PVA-based RH sensitive layers become more resistive. Thus, for RH > 82% (for CNOs-PVA at 1:1 w/w-based sensing layer) and for RH >50% (for CNOs-PVA at 2:1 w/w-based sensing layer), one can assume that the swelling of the hydrophilic polymer is the most significant RH sensing mechanism.

The swelling of the PVA molecular backbones via the adsorption of moisture was broadly exploited in manufacturing RH sensors. Holey CNHs-PVA [

55], SWCNTs-PVA [

66], MWCNTs-PVA composite yarn [

67], GO-PVA are just few examples [

68]. Obviously, each of the listed nanocomposites exhibits a RH threshold (value of RH corresponding to a dramatic increase of the resistance vs RH dependence) which can be modulated through several parameters, such as PVA polymerization degree, cross–linking degree, mutual interaction with nanocarbon material, PVA-nanocarbon material w/w ratio, alcoholysis degree etc. [

67].

It is interesting to point out the major difference between these nanocomposites and PVP/ nanocarbon materials-based nanocomposites used as RH sensing layers within the architecture of resistive sensors. While all the discussed PVA-based nanocomposites exhibit the RH threshold value at high RH, CNOs-PVP nanocomposite have a RH threshold value occurring at lower RH, around 50% (B Serban et al, Carbon Nano-Onions-Based Matrix Nanocomposite as Sensing Film for Resistive Humidity Sensor, ROMJIST accepted for publication), while CNHox-PVP nanocomposite does not show any threshold value at all [

55].

A first possible explanation for this phenomenon is related to the uncommonly low value of the water vapor permeability of PVA compared with to that of PVP and of other hydrophilic polymers [

69]. It is clear that water penetrates PVA only at high RH and only at this point enough quantity of water penetrates the polymers and expand their volume (swelling). In the case of CNHox-PVP, the higher water vapor permeability of PVP in comparison with PVA goes together with the mutual interaction, through hydrogen bonds, between PVP and nanocarbon materials. Thus, water penetrates continuously and linearly the matrix nanocomposite.

5. Conclusions

This paper presents several preliminary investigations regarding the RH detection response of a chemiresistive sensor that uses a novel sensing layers based on CNOs and PVA at 1/1 and 2:1 w/w ratio. The sensing device, including a Si/SiO2 substrate and gold electrodes, is obtained by drop casting the CNOs–PVA aqueous suspension on the Si/SiO2 substrate. The morphology and composition of the synthesized sensing layers are investigated by SEM, Raman spectroscopy, AFM and XRD. The RH performance of the designed sensors at RT was explored by applying a continuous flow of the electric current between the interdigitated electrodes and measuring the voltage as the RH was varied from 5% to 95%. For an RH threshold below 82% (in the case of CNOs–PVA at 1/1 w/w ratio) or below 50.5% (in the case of CNOs–PVA at 2/1 w/w ratio), the resistance showed a linear variation with RH, with a moderate slope, while for RH values above these thresholds significantly steeper slopes were measured. The change in relative resistance (ΔR/ΔRH) across different humidity steps showed that the CNOs-PVA sensor was more sensitive at humidity levels above 80%. The newly developed sensor using CNOs-PVA in a 1:1 (w/w) ratio showed response times that were similar to or better than those of the reference sensor. Its recovery time was about 30 seconds, roughly half that of the reference sensor. The decrease of the hole concentration in the CNOs in interaction with an electron donor molecule, such as water, and the swelling of the hydrophilic PVA polymer were demonstrated to be the main RH sensing mechanisms explaining the experimental results. The experimental data were analysed and compared with the previously published RH sensing behavior of sensing layers based on CNHox-PVP, CNHox-PVA and CNOs-PVP.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, B.C.S., N.D., and Octavian Buiu; methodology, B.C.S., N.D., Mihai Brezeanu, and Octavian Buiu; validation, B.C.S., and Marius Bumbac; formal analysis, B.C.S., C.D., and Marius Bumbac; investigation, N.D., C.P., C.T., and Oana Brancoveanu.; resources, Octavian Buiu.; data curation, B.C.S., and Marius Bumbac.; writing—original draft preparation, B.C.S., N.D., Octavian Buiu, Marius Bumbac, C.D., Mihai Brezeanu, C.P., C.M.N., C.R. and Oana Brancoveanu; writing—review and editing, B.C.S., Marius Bumbac; visualization, B.C.S., and Marius Bumbac; supervision, B.C.S., and Octavian Buiu.; project administration, Octavian Buiu; funding acquisition, Octavian Buiu. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The authors from IMT Bucharest would like to acknowledge the financial support of Contract No. 673 PED/2022 (PN-III-P2-2.1-PED-2021-4158) – UEFISCDI.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article/supplementary material. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author(s).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| CNH |

Carbon nanohorn |

| CNHox |

Oxidized carbon nanohorn |

| CNO |

Carbon nano onion |

| GO |

Graphene oxide |

| IDT |

Interdigitated |

| MWCNT |

Multi walled carbon nanotube |

| MS |

Manufactured sensor |

| PVA |

Polyvinyl alcohol |

| PVP |

Polyvinyl pyrrolidone |

| PMMA |

Poly(methyl methacrylate) |

| REF |

Reference sensor |

| RGO |

Reduced graphene oxide |

| RH |

Relative humidity |

| SAW |

Surface Acoustic Wave |

| SWCNT |

Single walled carbon nanotube |

References

- Alam, N.; Abid; Islam, S. S. Advancements in trace and low humidity sensors technologies using nanomaterials: A review. ACS Applied Nano Materials, 2024, 7.12, 13836-13864.

- Li, J., Fang, Z., Wei, D., Liu, Y. Flexible pressure, humidity, and temperature sensors for human health monitoring. Advanced Healthcare Materials, 2024, 13(31), 2401532.

- Humidity Sensor Market Size, Share & Trends Analysis Report By Type (Absolute Humidity Sensor, Relative Humidity Sensor), By End Use (Automotive, Industrial), By Region, And Segment Forecasts, 2025 – 2030, Grand View Research, Market Analysis Report. https://www.grandviewresearch.com/industry-analysis/humidity-sensor-market, accessed March 2025.

- Arman Kuzubasoglu, B. Recent studies on the humidity sensor: A mini review. ACS Applied Electronic Materials, 2022, 4(10), 4797-4807.

- Ku, C. A., Chung, C. K. Advances in humidity nanosensors and their application. Sensors, 2023, 23(4), 2328.

- Korotcenkov, G. Based Humidity Sensors as Promising Flexible Devices: State of the Art: Part 1. General Consideration. Nanomaterials, 2023, 13(6), 1110.

- Steele, J. J., Taschuk, M. T., Brett, M. J. (2008). Nanostructured metal oxide thin films for humidity sensors. IEEE Sensors Journal, 2008, 8(8), 1422-1429.

- Lee, J., Din, H. U., Ham, M. J., Song, Y., Lee, J. H., Kwon, Y. J., Jeong, Y. K. A Facile Way to Simultaneously Improve Humidity-Immunity and Gas Response in Semiconductor Metal Oxide Sensors. ACS sensors, 2024, 9(12), 6441-6449..

- Czajkowski, M., Guzik, M. Humidity-sensitive luminescent dye-doped polyelectrolyte films: Fabrication, characterization, and potential application as colorimetric moisture sensor. Dyes and Pigments, 2024, 231, 112390.

- Dai, J., Zhao, H., Lin, X., Liu, S., Liu, Y., Liu, X., Zhang, T. Ultrafast response polyelectrolyte humidity sensor for respiration monitoring. ACS applied materials & interfaces, 2019, 11(6), 6483-6490.

- Cho, M. Y., Kim, S., Kim, I. S., Kim, E. S., Wang, Z. J., Kim, N. Y., ... & Oh, J. M. Perovskite-induced ultrasensitive and highly stable humidity sensor systems prepared by aerosol deposition at room temperature. Advanced Functional Materials, 2020, 30(3), 1907449.

- Pi, M., Wu, D., Wang, J., Chen, K., He, J., Yang, J., ... & Tang, X. Real-time and ultrasensitive humidity sensor based on lead-free Cs2SnCl6 perovskites. Sensors and Actuators B: Chemical, 2022, 354, 131084.

- Rivadeneyra, A., Salmeron, J. F., Murru, F., Lapresta-Fernández, A., Rodríguez, N., Capitan-Vallvey, L. F., ... & Salinas-Castillo, A. Carbon dots as sensing layer for printed humidity and temperature sensors. Nanomaterials, 2020, 10(12), 2446.

- Duan, Z., Yuan, Z., Jiang, Y., Yuan, L., Tai, H.Amorphous carbon material of daily carbon ink: Emerging applications in pressure, strain, and humidity sensors. Journal of Materials Chemistry C, 2023, 11(17), 5585-5600.

- Epeloa, J., Repetto, C. E., Gómez, B. J., Nachez, L., Dobry, A. Resistivity humidity sensors based on hydrogenated amorphous carbon films. Materials Research Express, 2018, 6(2), 025604.

- Meng, J., Liu, T., Meng, C., Lu, Z., Li, J. Porous carbon nanofibres with humidity sensing potential. Microporous and Mesoporous Materials, 2023, 359, 112663.

- Yao, Y., Chen, X., Ma, W., Ling, W. Quartz crystal microbalance humidity sensors based on nanodiamond sensing films. IEEE Transactions on Nanotechnology, 2014, 13(2), 386-393.

- Wu, X., Wu, H., Jin, F., Ge, H. L., Gao, F., Wu, Q., ... & Yang, H. Facile preparation of fullerenol-based humidity sensor with highly fast response. Fullerenes, Nanotubes and Carbon Nanostructures, 2023, 31(12), 1132-1136.

- Liang, R., Luo, A., Zhang, Z., Li, Z., Han, C., Wu, W. Research progress of graphene-based flexible humidity sensor. Sensors, 2020, 20(19), 5601.

- Borini, S., White, R., Wei, D., Astley, M., Haque, S., Spigone, E., ... & Ryhänen, T. Ultrafast graphene oxide humidity sensors. ACS nano, 2013, 7(12), 11166-11173.

- Ghosh, R., Midya, A., Santra, S., Ray, S. K., Guha, P. K. Humidity sensing by chemically reduced graphene oxide. In Physics of Semiconductor Devices: 17th International Workshop on the Physics of Semiconductor Devices 2013, 2014, pp. 699-701, Springer International Publishing.

- Serban, B. C., Cobianu, C., Buiu, O., Bumbac, M., Dumbravescu, N., Avramescu, V., ... & Comanescu, F. Quaternary Oxidized Carbon Nanohorns—Based Nanohybrid as Sensing Coating for Room Temperature Resistive Humidity Monitoring. Coatings, 2021, 11(5), 530.

- Serban, B. C., Cobianu, C., Buiu, O., Bumbac, M., Dumbravescu, N., Avramescu, V., ... & Radulescu, C. Ternary nanocomposites based on oxidized carbon nanohorns as sensing layers for room temperature resistive humidity sensing. Materials, 2021, 14(11), 2705.

- Serban, B. C., Cobianu, C., Buiu, O., Bumbac, M., Dumbravescu, N., Avramescu, V., ... & Comanescu, F. C. Quaternary Holey Carbon Nanohorns/SnO2/ZnO/PVP Nano-Hybrid as Sensing Element for Resistive-Type Humidity Sensor. Coatings, 2021, 11(11), 1307.

- Serban, B. C., Dumbravescu, N., Buiu, O., Bumbac, M., Brezeanu, M., Pachiu, C., ... & Diaconescu, V. Resistive Humidity Sensor Based on Onion-Like Carbon-PVA Composite Sensing Film. In 2024 International Semiconductor Conference (CAS), 2024, pp. 65-68, IEEE.

- Memon, M. M., Hongyuan, Y., Pan, S., Wang, T., Zhang, W. Surface acoustic wave humidity sensor based on hydrophobic polymer film. Journal of Electronic Materials, 2022, 51(10), 5627-5634.

- Irawati, N., Abdullah, T. N. R., Rahman, H. A., Ahmad, H., Harun, S. W. PMMA microfiber loop resonator for humidity sensor. Sensors and Actuators A: Physical, 2017, 260, 112-116.

- Xu, W., Huang, W. B., Huang, X. G., Yu, C. Y. A simple fiber-optic humidity sensor based on extrinsic Fabry–Perot cavity constructed by cellulose acetate butyrate film. Optical Fiber Technology, 2013, 19(6), 583-586.

- Sears, W. M. The effect of humidity on the electrical conductivity of mesoporous polythiophene. Sensors and Actuators B: Chemical, 2008, 130(2), 661-667.

- Serban, B., Bercu, M., Voicu, S., Mihaila, M., Nechifor, G., Cobianu, C. Calixarene-doped polyaniline for applications in sensing. In 2006 International Semiconductor Conference, 2006, Vol. 2, pp. 257-260). IEEE.

- Dai, J., Zhao, H., Lin, X., Liu, S., Fei, T., Zhang, T. Design strategy for ultrafast-response humidity sensors based on gel polymer electrolytes and application for detecting respiration. Sensors and Actuators B: Chemical, 2020, 304, 127270.

- Yang, J., Guan, C., Yu, Z., Yang, M., Shi, J., Wang, P., ... & Yuan, L. High sensitivity humidity sensor based on gelatin coated side-polished in-fiber directional coupler. Sensors and Actuators B: Chemical, 2020, 305, 127555.

- Fei, T., Zhao, H., Jiang, K., Zhou, X., Zhang, T. Polymeric humidity sensors with nonlinear response: Properties and mechanism investigation. Journal of Applied Polymer Science, 2013, 130(3), 2056-2061.

- Soomro, A. M., Jabbar, F., Ali, M., Lee, J. W., Mun, S. W., Choi, K. H. All-range flexible and biocompatible humidity sensor based on poly lactic glycolic acid (PLGA) and its application in human breathing for wearable health monitoring. Journal of Materials Science: Materials in Electronics, 2019, 30, 9455-9465.

- Chen, L. H., Li, T., Chan, C. C., Menon, R., Balamurali, P., Shaillender, M., ... & Leong, K. C. Chitosan based fiber-optic Fabry–Perot humidity sensor. Sensors and Actuators B: Chemical, 2012, 169, 167-172.

- Akita, S., Sasaki, H., Watanabe, K., Seki, A. A humidity sensor based on a hetero-core optical fiber. Sensors and Actuators B: Chemical, 2010, 147(2), 385-391.

- Qian, J., Tan, R., Feng, M., Shen, W., Lv, D., Song, W. Humidity Sensing Using Polymers: A Critical Review of Current Technologies and Emerging Trends. Chemosensors, 2024, 12(11), 230.

- Mahapure, P. D., Gangal, S. A., Aiyer, R. C., Gosavi, S. W. Combination of polymeric substrates and metal–polymer nanocomposites for optical humidity sensors. Journal of Applied Polymer Science, 2019, 136(5), 47035.

- Tang, M., Liu, X., Zhang, D., Zhang, H., Xi, G. Ultra-sensitive humidity QCM sensor based on sodium alginate/polyacrylonitrile composite film for contactless Morse code communication. Sensors and Actuators B: Chemical, 2024, 407, 135429.

- Feng, D., Zheng, H., Sun, H., Li, J., Xi, J., Deng, L., ... & Zhao, J. SnO2/polyvinyl alcohol nanofibers wrapped tilted fiber grating for high-sensitive humidity sensing and fast human breath monitoring. Sensors and Actuators B: Chemical, 2023, 388, 133807.

- Seo, Y. K., Chitale, S. K., Lee, U., Patil, P., Chang, J. S., Hwang, Y. K. Formation of polyaniline-MOF nanocomposites using nano-sized Fe (III)-MOF for humidity sensing application. Journal of Nanoscience and Nanotechnology, 2019, 19(12), 8157-8162.

- Tulliani, J. M., Inserra, B., Ziegler, D. Carbon-based materials for humidity sensing: A short review. Micromachines, 2019, 10(4), 232.

- Cai, C., Zhao, W., Yang, J., Zhang, L. Sensitive and flexible humidity sensor based on sodium hyaluronate/MWCNTs composite film. Cellulose, 2021, 28, 6361-6371.

- Zhang, R., Huang, J., Guo, Z. Functionalized paper with intelligent response to humidity. Colloids and Surfaces A: Physicochemical and Engineering Aspects, 2022, 633, 127844.

- Rahman, S. A., Khan, S. A., Rehman, M. M., Kim, W. Y. Highly sensitive and stable humidity sensor based on the bi-layered PVA/graphene flower composite film. Nanomaterials, 2022, 12(6), 1026.

- Bhangare, B., Jagtap, S., Ramgir, N., Waichal, R., Muthe, K. P., Gupta, S. K., ... & Gosavi, S. Evaluation of humidity sensor based on PVP-RGO nanocomposites. IEEE Sensors Journal, 2018, 18(22), 9097-9104.

- Wang, Y., Shen, C., Lou, W., Shentu, F. Fiber optic humidity sensor based on the graphene oxide/PVA composite film. Optics Communications, 2016, 372, 229-234.

- Kafy, A., Akther, A., Shishir, M. I., Kim, H. C., Yun, Y., Kim, J. Cellulose nanocrystal/graphene oxide composite film as humidity sensor. Sensors and Actuators A: Physical, 2016, 247, 221-226.

- Yoo, K.P.; Lima, L.-T.; Min, N.-K.; Lee, M.J.; Lee, C.J.; Park, C.-W. Novel resistive-type humidity sensor based on multiwall carbon nanotube/polyimide composite films. Sens. Actuators B Chem. 2010, 145, 120–125.

- Zhou, G.; Byun, J.H.; Oh, Y.; Jung, B.-M.; Cha, H.-J.; Seong, D.G.; Um, M.K.; Hyun, S.; Chou, T.W. High sensitive wearable textile-based humidity sensor made of high-strength, single-walled carbon nanotube (SWCNT)/Poly(Vinyl Alcohol) (PVA) filaments. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces, 2017, 9, 4788–4797.

- Jlassi, K., Mallick, S., Ali, A. B., Mutahir, H., Salauddin, S. A., Ahmad, Z., ... & Chehimi, M. Polyvinylpyridine–carbon dots composite-based novel humidity sensor. Applied Physics A, 2023, 129(10), 691.

- Chen, Q., Mao, K. L., Yao, Y., Huang, X. H., Zhang, Z. Nanodiamond/cellulose nanocrystals composite-based acoustic humidity sensor. Sensors and Actuators B: Chemical, 2022, 373, 132748.

- Tian, S., Wen, F., Qian, L., Li, C., Wang, L., Li, D., ... & Li, M. Surface acoustic wave humidity sensor based on Flake-like nanodiamond-chitosan composite sensitive film. IEEE Sensors Journal, 2023, 23(17), 19127-19136.

- Serban, B. C., Cobianu, C., Buiu, O., Bumbac, M., Dumbravescu, N., Avramescu, V., ... & Radulescu, C. Ternary nanocomposites based on oxidized carbon nanohorns as sensing layers for room temperature resistive humidity sensing. Materials, 2021, 14(11), 2705.

- Serban, B. C., Buiu, O., Dumbravescu, N., Cobianu, C., Avramescu, V., Brezeanu, M., ... & Nicolescu, C. M. Oxidized carbon nanohorn-hydrophilic polymer nanocomposite as the resistive sensing layer for relative humidity. Analytical Letters, 2021, 54(3), 527-540. Resistive.

- Serban, B. C., Dumbravescu, N., Buiu, O., Bumbac, M., Brezeanu, M., Pachiu, C., ... & Diaconescu, V. Resistive Humidity Sensor Based on Onion-Like Carbon-PVA Composite Sensing Film. In 2024 International Semiconductor Conference (CAS), 2024, pp. 65-68, IEEE.

- Serban, B. C., Buiu, O., Dumbravescu, N., Cobianu, C., Avramescu, V., Brezeanu, M., ... & Nicolescu, C. M. Oxidized Carbon Nanohorns as Novel Sensing Layer for Resistive Humidity Sensor. Acta Chimica Slovenica, 2020, 67(2).

- Pinto, R. M., Nemala, S. S., Faraji, M., Fernandes, J., Ponte, C., De Bellis, G., ... & Capasso, A. Material jetting of carbon nano onions for printed electronics. Nanotechnology, 2023, 34(36), 365710.

- Tomita, S., Burian, A., Dore, J.C., LeBolloch, D., Fujii, M., Hayashi, S., Diamond nanoparticles to carbon onions transformation: X-ray diffraction studies, Carbon, 2002, 40, 1469–1474.

- Zou, Q., Li, Y. G., Lv, B., Wang, M. Z., Zou, L. H., Zhao, Y. C. Transformation of onion-like carbon from nanodiamond by annealing. Inorganic Materials, 2010, 46, 127-131.

- Gupta, S., Pramanik, A. K., Kailath, A., Mishra, T., Guha, A., Nayar, S., Sinha, A. Composition dependent structural modulations in transparent poly (vinyl alcohol) hydrogels. Colloids and Surfaces B: Biointerfaces, 2009, 74(1), 186-190.

- Alancherry, S., Bazaka, K., Levchenko, I., Al-Jumaili, A., Kandel, B., Alex, A., ... & Jacob, M. V. Fabrication of nano-onion-structured graphene films from citrus sinensis extract and their wetting and sensing characteristics. ACS applied materials & interfaces, 2020, 12(26), 29594-29604.

- Pearson, R. G. Hard and soft acids and bases, HSAB, part II: Underlying theories. Journal of Chemical Education, 1968, 45(10), 643.

- Serban, B. C., Brezeanu, M., Cobianu, C., Costea, S., Buiu, O., Stratulat, A., Varachiu, N. Materials selection for gas sensing. An HSAB perspective. In 2014 International Semiconductor Conference (CAS), 2014, pp. 21-30, IEEE.

- Dhonge, B. P., Motaung, D. E., Liu, C. P., Li, Y. C., Mwakikunga, B. W.Nano-scale carbon onions produced by laser photolysis of toluene for detection of optical, humidity, acetone, methanol and ethanol stimuli. Sensors and Actuators B: Chemical, 2015, 215, 30-38.

- Zhou, G., Byun, J. H., Oh, Y., Jung, B. M., Cha, H. J., Seong, D. G., ... & Chou, T. W. Highly sensitive wearable textile-based humidity sensor made of high-strength, single-walled carbon nanotube/poly (vinyl alcohol) filaments. ACS applied materials & interfaces, 2017, 9(5), 4788-4797.

- Li, W., Xu, F., Sun, L., Liu, W., Qiu, Y. A novel flexible humidity switch material based on multi-walled carbon nanotube/polyvinyl alcohol composite yarn. Sensors and Actuators B: Chemical, 2016, 230, 528-535.

- Wang, Y., Shen, C., Lou, W., Shentu, F. Fiber optic humidity sensor based on the graphene oxide/PVA composite film. Optics Communications, 2016, 372, 229-234.

- Bui, T. D., Wong, Y., Thu, K., Oh, S. J., Kum Ja, M., Ng, K. C., ... & Chua, K. J. Effect of hygroscopic materials on water vapor permeation and dehumidification performance of poly (vinyl alcohol) membranes. Journal of Applied Polymer Science, 2017, 134(17).

Figure 1.

The structure of: (a) CNOs, and of (b) PVA.

Figure 1.

The structure of: (a) CNOs, and of (b) PVA.

Figure 2.

The metal stripes of the IDT.

Figure 2.

The metal stripes of the IDT.

Figure 3.

RH measurements experimental set-up.

Figure 3.

RH measurements experimental set-up.

Figure 4.

SEM of CNOs-PVA, 1:1 (w/w) layer at: (a) x 5,000, (b) x 30,000, and (c) x 3,000 magnification.

Figure 4.

SEM of CNOs-PVA, 1:1 (w/w) layer at: (a) x 5,000, (b) x 30,000, and (c) x 3,000 magnification.

Figure 5.

Raman spectra of a solid-state film of CNOs-PVA (1/1 w/w mass ratio) deposited on the Si substrate.

Figure 5.

Raman spectra of a solid-state film of CNOs-PVA (1/1 w/w mass ratio) deposited on the Si substrate.

Figure 6.

XRD pattern for CNOs-PVA 1/1 w/w ratio (above) and CNOs (below).

Figure 6.

XRD pattern for CNOs-PVA 1/1 w/w ratio (above) and CNOs (below).

Figure 7.

AFM images of the CNOs-PVA RH sensing layer (1/1 w/w ratio).

Figure 7.

AFM images of the CNOs-PVA RH sensing layer (1/1 w/w ratio).

Figure 8.

AFM images of the CNOs-PVA RH sensing layer 2:1 w/w mass ratio.

Figure 8.

AFM images of the CNOs-PVA RH sensing layer 2:1 w/w mass ratio.

Figure 9.

RH and resistance variation vs. time for two types of CNOs-PVA sensing layers: (a) 1:1 (w/w), and (b) 2:1 (w/w).

Figure 9.

RH and resistance variation vs. time for two types of CNOs-PVA sensing layers: (a) 1:1 (w/w), and (b) 2:1 (w/w).

Figure 10.

– RH variation in repeated sorption-desorption cycles of three identically manufactured sensors employing as sensing layer: a) CNOs-PVA 1:1 (w/w), and b) CNOs-PVA 2:1 (w/w).

Figure 10.

– RH variation in repeated sorption-desorption cycles of three identically manufactured sensors employing as sensing layer: a) CNOs-PVA 1:1 (w/w), and b) CNOs-PVA 2:1 (w/w).

Figure 11.

Response time and relative resistance for each RH variation step: a) calculated parameters for a single RH variation step, b) ΔR/ΔRH values (red bars), and c) response time (green bars).

Figure 11.

Response time and relative resistance for each RH variation step: a) calculated parameters for a single RH variation step, b) ΔR/ΔRH values (red bars), and c) response time (green bars).

Figure 12.

Relative variation of the resistance (Rf-Ri)/Ri as a function of RH for MS employing as sensing layer: (a) CNOs-PVA at 1:1 (w/w), and (b) CNOs-PVA at 1:1 (w/w) (sorption – red dots, desorption – blue dots).

Figure 12.

Relative variation of the resistance (Rf-Ri)/Ri as a function of RH for MS employing as sensing layer: (a) CNOs-PVA at 1:1 (w/w), and (b) CNOs-PVA at 1:1 (w/w) (sorption – red dots, desorption – blue dots).

Figure 14.

The swelling effect occurring in the PVA in contact with water molecules leading to the disruption of hydrogen bonds between hydroxyl groups of PVA and the percolating pathways of the CNOs.

Figure 14.

The swelling effect occurring in the PVA in contact with water molecules leading to the disruption of hydrogen bonds between hydroxyl groups of PVA and the percolating pathways of the CNOs.

Table 1.

Nanocarbon materials-based nanocomposites and nanohybrids used as RH sensing films.

Table 1.

Nanocarbon materials-based nanocomposites and nanohybrids used as RH sensing films.

| Type of nanocomposite/nanohybrid |

Type of sensor |

Reference |

| Sodium hyaluronate (SH) - Multi-walled carbon nanotubes (MWCNTs) |

Resistive |

[43] |

| Nitrocellulose - MWCNTs |

Resistive |

[44] |

| PVA - Graphene flower |

Capacitive |

[45] |

| PVP – Reduced graphene oxide (RGO) |

Resistive |

[46] |

| Graphene oxide (GO) - PVA |

Optical |

[47] |

| Cellulose nanocrystals – GO |

Capacitive |

[48] |

| MWCNTs - Polyimide |

Resistive |

[49] |

| Single-walled carbon nanotubes (SWCNTs) - PVA filaments |

Resistive |

[50] |

| PVP – Carbon dots |

Resistive |

[51] |

| Nanodiamond - Cellulose nanocrystals |

Surface Acoustic Wave (SAW) |

[52] |

| flake-like nanodiamond-chitosan composite |

SAW |

[53] |

| GO – Oxidized carbon nanohorns (CNHox) - PVP |

Resistive |

[54] |

| CNHox - PVP |

Resistive |

[55] |

| CNHox - PVA |

Resistive |

[55] |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).