Submitted:

09 April 2025

Posted:

10 April 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

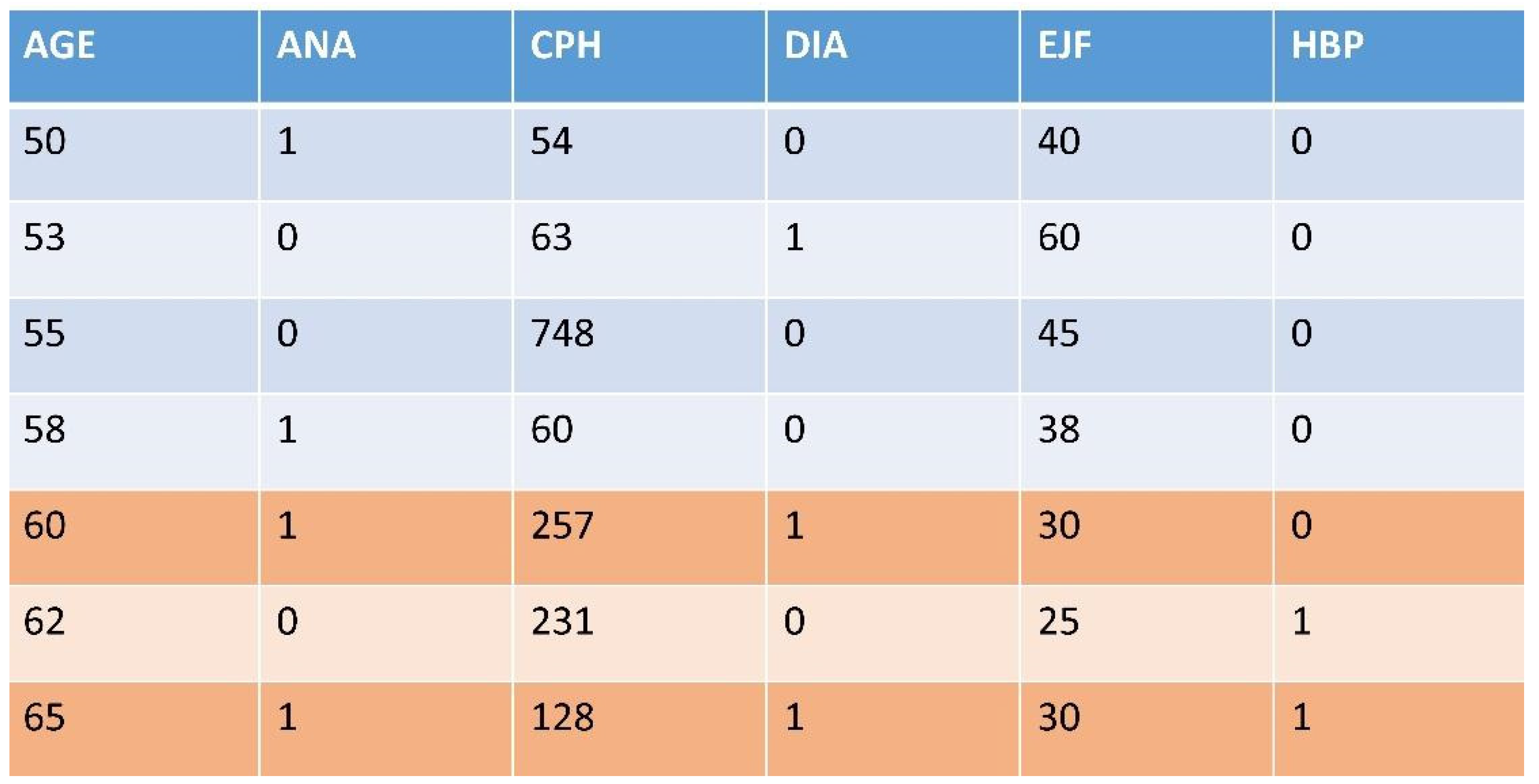

2.1. Dataset Generation over a Probability Distribution: Dataset Feature Splitting (DFS)

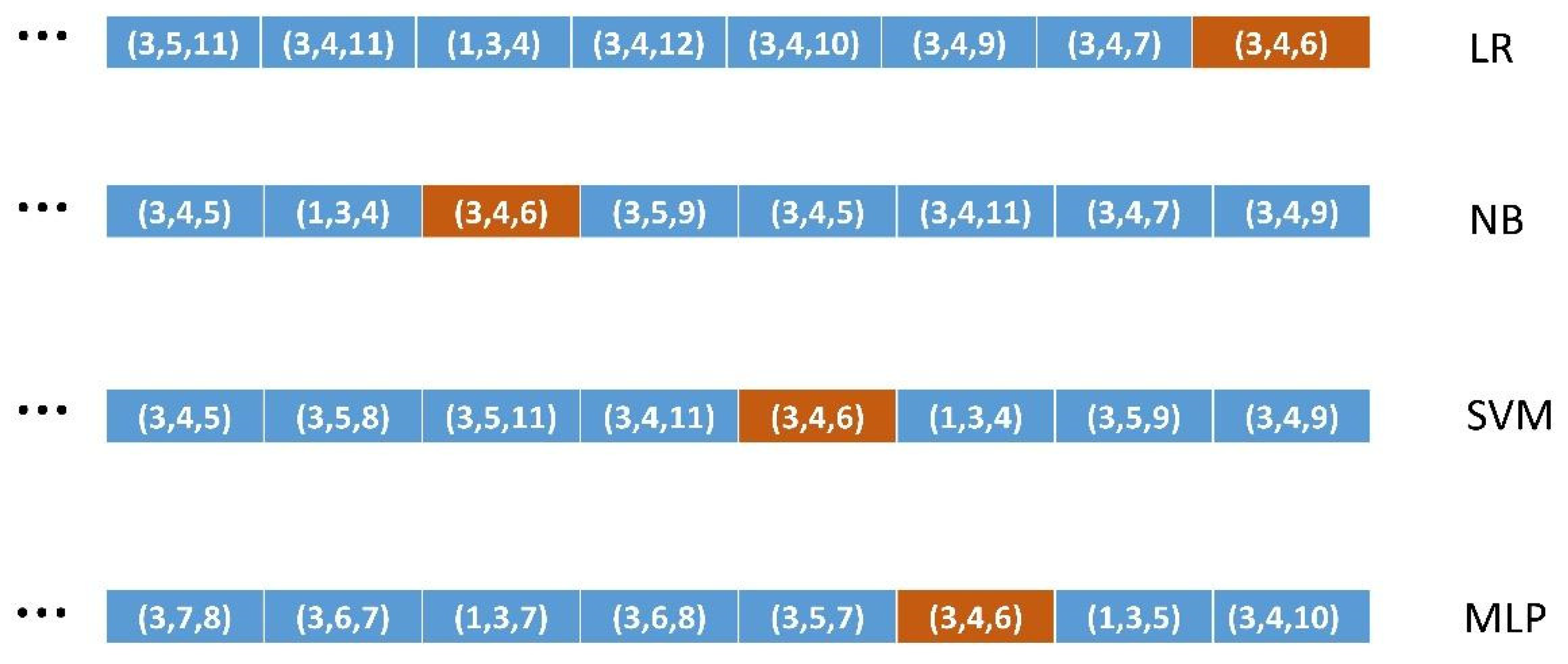

2.2. An Objective Measure of Classification performance: Ordered Lists of All Combinations of FS of a Given Size

2.3. Encoding Knowledge Relevance: Using Medical Expertise from LLMs

2.4. How Well Classify the Different ML Algorithms the Most Relevant Binary FSs

2.5. Validation Methodology

2.5.1. Validation of Method 1 (DFS)

2.5.2. Validation of Methods 2, 3 and 4

2.6. Application of the Methodology: Knowledge Extraction from the Original Datasets

3. Results

3.1. Results of Methods

| HP-UCI | HF-UCI | ||

| AGE H | (4,5,6,7,10,11) | AGE H | (2,3,4,6,7,9,10,11) |

| SEX H | (5) | ANA H | (1,3,4,6,7,9,10,11) |

| SEX L | (3,10) | CPH H | (1,2,4,6,9,11) |

| ALB L | (4,5,6,7,11,12) | DIA H | (1,2,3,6,7,9,10,11) |

| ALP H | (1,3,5,6,7,9,10,11,12) | EJF L | (1,2,3,4,6,7,8,10,11) |

| ALT H | (1,2,3,4,6,7,9,10,11,12) | HBP H | (1,2,3,4,7,9,10,11) |

| BIL H | (1,3,4,5,6,11,12) | PLA H | (1,2,4,6,10,11) |

| CHO L | (4,5,6,11) | SCR H | (1,2,3,4,5,6,7,11) |

| CRE H | (1,4,5,6,12) | SSO H | (1,2,3,4,6,10,11) |

| PRO H | (3,4,5,6, 7,10,11) | SEX H | (6,7) |

| SEX L | (1,2,4,9,11) | ||

| HD-UCI | SMO H | (1,2,3,4,6,7,9,10) | |

| AGE H | (2,3,4,5,7,8,9,10,11,12) | ||

| SEX H | (5,8,10,11,12) | CKD-UCI | |

| SEX L | (1,4,6,7,9) | AGE H | (2,3,4,6,7,8) |

| BPS H | (1,2,5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12) | URE H | (1,3,4,5,6,7) |

| FBS H | (1,2,4,7,9,10,11,12) | CRE H | (1,2,4,5,6,8) |

| ECG H | (2,4,7,8,9,10) | SOD L | (1,2,3,5,6,8) |

| MHR H | (1,2,4,5,6,8,9,10,11,12) | POT H | (2,3,4,6,8) |

| ANG H | (1,2,4,6,7,9,10,12) | HEM L | (1,2,3,4,5,7,8) |

| STD H | (1,2,4,5,6,7,8,10,11,12) | WHI H | (1,2,6,8) |

| SLO H | (1,2,4,5,6,7,8,9,11,12) | RED L | (1,3,4,5,6,7) |

| CA H | (1,2,4,5,7,9,10,12) | ||

| CHO H | (1,2,4,5,7,8,9,10,11) |

| HP-UCI | → | HF-UCI | → |

| AGE H | KN,NB,SVM,MLP,DT,LR | AGE H | DT,NB,LR,KN,MLP,SVM |

| SEX H | SVM,NB,KN,DT,MLP,LR | ANA H | DT,NB,LR,KN,SVM,MLP |

| SEX L | MLP,DT,KN,LR,NB,SVM | CPH H | DT,LR,KN,MLP,NB,SVM |

| ALB L | SVM,KN,NB,MLP,LR,DT | DIA H | NB,DT,LR,KN,MLP,SVM |

| ALP H | SVM,KN,MLP,DT,LR,NB | EJF L | NB,DT,KN,MLP,LR,SVM |

| ALT H | LR,KN,DT,SVM,MLP,NB | HBP H | NB,DT,KN,MLP,LR,SVM |

| BIL H | SVM,KN,MLP,NB,DT,LR | PLA H | NB,DT,LR,MLP,KN,SVM |

| CHO L | SVM,MLP,KN,NB,LR,DT | SCR H | DT,SVM,NB,LR,KN,MLP |

| CRE H | SVM,DT,MLP,LR,NB,KN | SSO H | NB,LR,DT,MLP,KN,SVM |

| PRO H | KN,SVM,MLP,LR,NB,DT | SEX H | NB,DT,LR,MLP,KN,SVM |

| SEX L | LR,NB,DT,MLP,KN,SVM | ||

| HD-UCI | → | SMO H | NB,LR,DT,MLP,KN,SVM |

| AGE H | DT,NB,SVM,MLP,LR,KN | ||

| SEX H | KN,DT,SVM,MLP,LR,NB | CKD-UCI | → |

| SEX L | NB,KN,DT,SVM,MLP,LR | AGE H | KN,LR,SVM,MLP,NB,DT |

| BPS H | DT,NB,SVM,KN,MLP,LR | URE H | DT,LR,KN,MLP,SVM,NB |

| FBS H | DT,KN,MLP,SVM,LR,NB | CRE H | DT,KN,MLP,SVM,LR,NB |

| ECG H | NB,MLP,LR,SVM,KN,DT | SOD L | SVM,KN,LR,MLP,NB,DT |

| MHR H | DT,NB,KN,SVM,MLP,LR | POT H | SVM,LR,NB,KN,MLP,DT |

| ANG H | LR,KN,DT,SVM,NB,MLP | HEM L | DT,SVM,MLP,NB,KN,LR |

| STD H | LR,DT,NB,MLP,SVM,KN | WHI H | DT,MLP,LR,KN,SVM,NB |

| SLO H | SVM,KN,NB,MLP,LR,DT | RED L | DT,LR,SVM,NB,KN,MLP |

| CA H | NB,LR,MLP,SVM,KN,DT | ||

| CHO H | DT,KN,MLP,SVM,NB,LR |

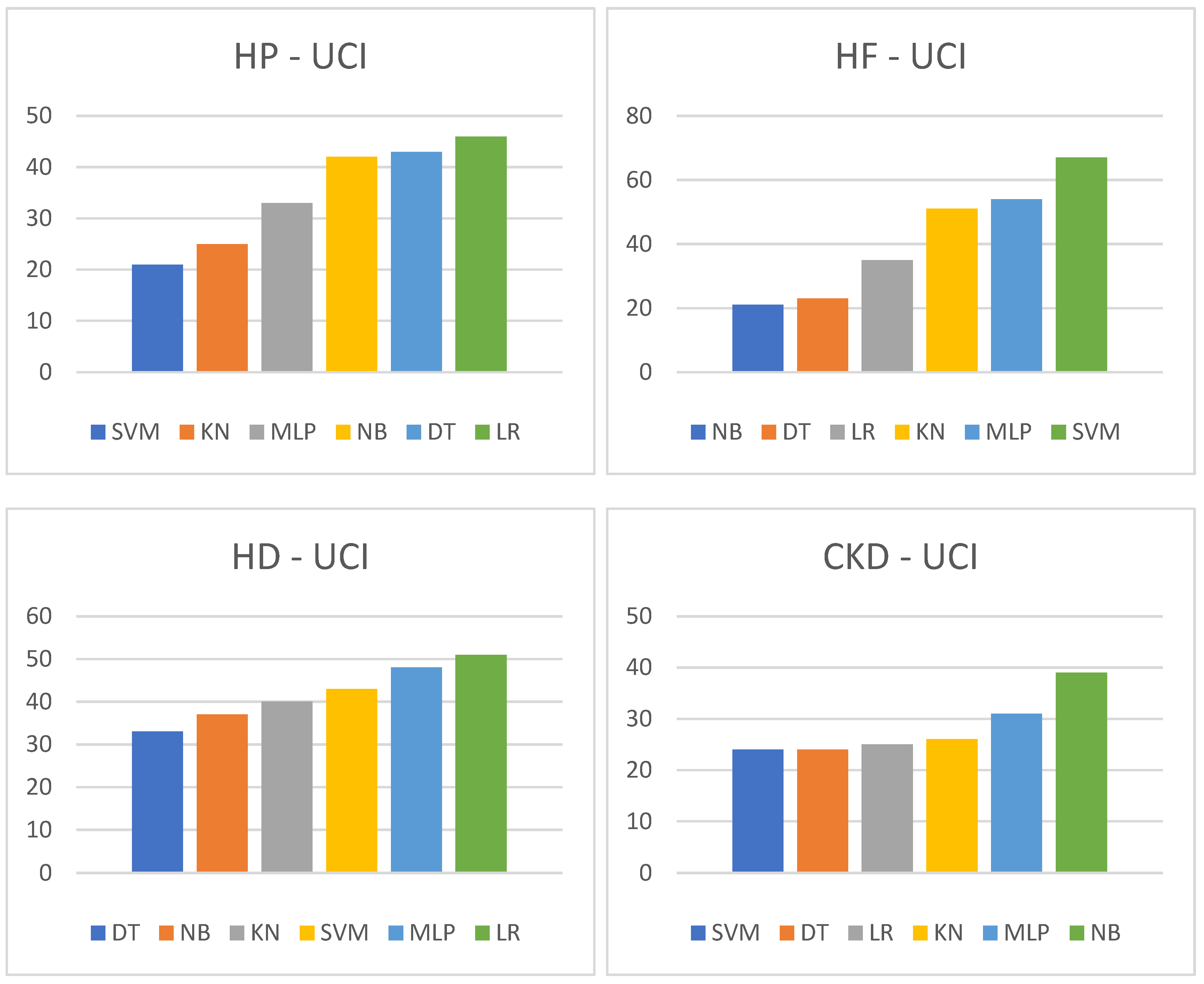

| HP-UCI | → | HF-UCI | → | ||||||||

| SVM | KN | MLP | NB | DT | LR | NB | DT | LR | KN | MLP | SVM |

| 21 | 25 | 33 | 42 | 43 | 46 | 21 | 23 | 35 | 51 | 54 | 67 |

| HD-UCI | → | CKD-UCI | → | ||||||||

| DT | NB | KN | SVM | MLP | LR | SVM | DT | LR | KN | MLP | NB |

| 33 | 37 | 40 | 43 | 48 | 51 | 24 | 24 | 25 | 26 | 31 | 39 |

3.2. Validation of Methods

3.2.1. Validation of Method 1 (DFS)

| HP-UCI | 4 out of 10 | HF-UCI | 10 out of 12 |

| AGE H | 1.0892849424e-05 | AGE H | 0.00058360217226 |

| SEX H | 5.1118124321e-06 | ANA H | 0.00352660750438 |

| SEX L | 1.9878513331e-19 | CPH H | 0.59033279794372 |

| ALB L | 9.6008360198e-26 | DIA H | 0.00765360026050 |

| ALP H | 1.1394834474e-05 | EJF L | 4.7648532405e-07 |

| ALT H | 4.3517379024e-46 | HBP H | 0.00058360217226 |

| BIL H | 1.4937625445e-05 | PLA H | 0.00018288992313 |

| CHO L | 1.8795587161e-19 | SCR H | 0.59033279794372 |

| CRE H | 4.2769255669e-26 | SSO H | 4.7648532405e-07 |

| PRO H | 2.2151976407e-22 | SEX H | 0.00018288992313 |

| SEX L | 0.00178955624413 | ||

| HD-UCI | 9 out of 12 | SMO H | 0.12566168302727 |

| AGE H | 0.66297421392268 | ||

| SEX H | 0.01899680622953 | CKD-UCI | 0 out of 8 |

| SEX L | 1.4733907068e-08 | AGE H | 4.6913601105e-31 |

| BPS H | 0.00468751862537 | URE H | 1.6302989587e-33 |

| FBS H | 0.01116685752824 | CRE H | 2.0841286358e-30 |

| ECG H | 0.00204213738762 | SOD L | 1.6087231294e-42 |

| MHR H | 8.6014095603e-11 | POT H | 2.0841286358e-30 |

| ANG H | 0.01899680622953 | HEM L | 3.0897650452e-47 |

| STD H | 1.1199214677e-06 | WHI H | 2.1831400120e-21 |

| SLO H | 0.22253198035961 | RED L | 3.4672730092e-40 |

| CA H | 6.8454149810e-09 | ||

| CHO H | 0.07620693805287 |

3.2.2. Validation of Methods 2, 3, and 4

| size 3 | size 4 | size 5 | size 6 | |

| HP | 0.0036986186 | 0.0009519294 | 0.0035663982 | 0.0187894355 |

| HF | 1.872461e-06 | 2.896402e-07 | 1.002365e-06 | 4.600115e-07 |

| HD | 0.4014911860 | 0.2505481941 | 0.3300802933 | 0.2256578590 |

| CKD | 0.2993305380 | 0.3203686985 | 0.3203686985 | 0.1119473455 |

4. Discussion

4.1. Limitations and Further Work

Conclusions

Funding

Authors’ contributions:

Acknowledgments

Availability of data and material:

Ethics approval:

Consent to participate:

Consent for publication:

Competing interests:

Appendix 1. The Four Original Datasets Used

References

- Guyon, I., Elisseeff, A. An Introduction to Variable and Feature Selection. J Mach Learn Res 3 2003; 1157-1182. [CrossRef]

- Blum, A. L. , Langley, P. Selection of relevant features and examples in machine learning. Artif Intell 97 1997; 245-271.

- Kohavi, R. , John, G. H. Wrappers for feature selection. Artif Intell 97 1997; 273-324.

- Bishop, C. M. Pattern Recognition and Machine Learning. Springer; 2006.

- Swallow, D.M. Genetic influences on lactase persistence and lactose intolerance. Annual Review of Genetics 2003.

- UC Irvine Machine Learning Repository. https://archive.ics.uci.edu/ Accessed. 26 March.

- Witten, I. H. , Frank, E., Hall, M. A., Pal, C. J. Data Mining: Practical Machine Learning Tools and Techniques. Morgan Kaufmann; 2016.

- Pedregosa, F. , Varoquaux, G., Gramfort, A., Michel, V., Thirion, B., Grisel, O., Blondel, M., Prettenhofer, P., Weiss, R., Dubourg, V., Vanderplas, J., Passos, A., Cournapeau, D., Brucher, M., Perrot, M., Duchesnay, E. Scikit-learn: Machine learning in Python, J Mach Learn Res 12. 2011.

- Zhou, S., Xu, Z., Zhang, M. et al. Large Language Models for Disease Diagnosis: A Scoping Review. 2024. https://arxiv.org/abs/2409.00097 Accessed 26 March 2025.

- Nazi, Z. A. , Peng, W. Large Language Models in Healthcare and Medical Domain: A review. 2024. https://arxiv.org/abs/2401.06775 Accessed. 26 March.

- OpenAI. ChatGPT (v2.0) [Large language model]. OpenAI. 2025. https://openai.com/chatgpt Accessed 26 March 2025.

- Google, AI. Gemini: A Tool for Scientific Writing Assistance. 2025. https://gemini.google.com/ Accessed. 26 March.

- Smirnov, N. (1948). Table for estimating the goodness of fit of empirical distributions. Annals of Mathematical Statistics, 19(2), 279-281.

- Benjamini, Y., Hochberg, Y. (1995). Controlling the false discovery rate: A practical and powerful approach to multiple testing. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society: Series B (Methodological), 57(1), 289-300. [CrossRef]

- Pearson, K. (1900). On the criterion that a given system of deviations from the probable in the case of a correlated system of variables is such that it can be reasonably supposed to have arisen from random sampling. Philosophical Magazine, 50(302), 157-175. [CrossRef]

- Dunn, O. J. (1961). Multiple comparisons among means. Journal of the American Statistical Association, 56(293), 52-64. [CrossRef]

|

Method 1. Dataset feature splitting Select a column (feature) from the set of features of the dataset Sort the dataset using that column Set a threshold in the ordered column Divide the dataset into two parts (higher and lower datasets) |

|

Method 2. Ordered list building For each ML algorithm For each FS size 3 through 6 Compute the weighted F measure of the supervised ML execution Add it to the sorted list corresponding to each combination (ML algorithm, FS size) |

|

Method 3. Medical knowledge encoding For each working dataset generated using DFS having one driving feature Fi For each remaining feature in the dataset Fj Query a LLM to check if the pair (Fi, Fj) is medical knowledge relevant or not If yes, add Fj to the list of relevant features with respect to Fi |

| ALP H | (1,3,5,6,7,9,10,11,12) |

| CRE H | (1,4,5,6,12) |

|

Method 4. ML algorithms relevance power For each of the 6 ML algorithms For each working dataset and its driving medical feature Fi For each feature Fj in its list of medical knowledge relevant features For each of the 4 sizes F-measure-sorted lists Obtain and accumulate the position of Fj in the F-measure-sorted list Accumulate the positions of all the Fj for each size Return the ML algorithm with the maximum accumulated for each size |

| CRE H | ||||||

| size 3 | 161.8 (SVM) | 141.1 (LR) | 136.6 (MLP) | 135.0 (DT) | 134.8 (KN) | 132.0 (NB) |

| size 4 | 477.5 (SVM) | 432.4 (DT) | 412.9 (LR) | 406.6 (MLP) | 404.1 (NB) | 392.4 (KN) |

| size 5 | 942.2 (SVM) | 879.8 (DT) | 839.8 (MLP) | 819.6 (NB) | 815.5 (LR) | 787.4 (KN) |

| size 6 | 1299.4(SVM) | 1229.5 (DT) | 1174.3(MLP) | 1157.6 (NB) | 1144.8 (LR) | 1119.2 (KN) |

| ALP H | SVM,KN,MLP,DT,LR,NB |

| CRE H | SVM,DT,MLP,LR,NB,KN |

| SVM | KN | MLP | NB | DT | LR |

| 21 | 25 | 33 | 42 | 43 | 46 |

| ALP H | 1.1394834474e-05 |

| CRE H | 4.2769255669e-26 |

| HP-3 | AGE H | SEX H | SEX L | ALB L | ALP H | ALT H | BIL H | CHO H | CREH | PRO H |

| LR | 260.97 | 22.72 | 46.02 | 181.25 | 254.82 | 284.44 | 191.44 | 101.17 | 141.08 | 205.61 |

| NB | 267.32 | 26.46 | 46.17 | 182.02 | 248.15 | 263.85 | 203.93 | 130.34 | 132.04 | 205.65 |

| SVM | 267.09 | 31.51 | 46.24 | 188.25 | 261.16 | 275.26 | 217.63 | 138.53 | 161.76 | 208.95 |

| MLP | 262.86 | 23.11 | 49.42 | 181.16 | 251.13 | 273.78 | 201.84 | 132.26 | 136.59 | 206.89 |

| DT | 200.54 | 29.81 | 51.44 | 150.72 | 236.03 | 275.34 | 189.28 | 100.22 | 134.95 | 177.27 |

| KN | 270.33 | 29.71 | 46.17 | 187.93 | 257.04 | 280.88 | 210.11 | 139.65 | 134.83 | 216.31 |

| size 3 | size 4 | size 5 | size 6 | |

| HP | 0.0036986186 | 0.0009519294 | 0.0035663982 | 0.0187894355 |

| HP-UC | ||||||

| size 3 | 213.0 (DT) | 209.3 (SVM) | 207.2 (KN) | 201.9 (LR) | 200.7 (MLP) | 199.0 (NB) |

| size 4 | 934.1 (SVM) | 928.8 (DT) | 925.0 (MLP) | 917.2 (KN) | 889.4 (LR) | 887.5 (NB) |

| size 5 | 2450.6 (SVM) | 2436.5 (DT) | 2413.9 (KN) | 2365.2 (MLP) | 2340.1 (NB) | 2335.2 (LR) |

| size 6 | 4218.5 (SVM) | 4206.7 (DT) | 4173.9 (KN) | 4058.8 (NB) | 4049.6 (MLP) | 4036.0 (LR) |

| Order | SVM | DT | KN | MLP | NB | LR |

| HF-UC | ||||||

| size 3 | 268.9(DT) | 244.5 (KN) | 227.0 (NB) | 218.8 (SVM) | 211.9 (MLP) | 203.5 (LR) |

| size 4 | 1208.5(DT) | 1072.8 (KN) | 1022.9 (NB) | 1008.2 (SVM) | 968.1 (MLP) | 937.9 (LR) |

| size 5 | 3179.7 (DT) | 2776.2 (KN) | 2744.1 (SVM) | 2706.2(NB) | 2600.5 (MLP) | 2553.0 (LR) |

| size 6 | 5481.8(DT) | 4872.2 (SVM) | 4826.8(KN) | 4712.2(NB) | 4587.9 (MLP) | 4547.1 (LR) |

| Order | DT | KN | SVM | NB | MLP | LR |

| HP-UCI | SVM | DT | KN | MLP |

| FS size 3 | (5, 6, 10) | (5, 6, 12) | (5, 6, 7) | (3, 6, 7) |

| FS size 4 | (5, 6, 7, 10) | (4, 5, 6, 12) | (5, 6, 7, 10) | (6, 7, 10, 12) |

| FS size 5 | (4, 5, 6, 7, 10) | (5, 6, 7, 8, 12) | (4, 5, 6, 7, 10) | (4, 5, 6, 11, 12) |

| FS size 6 | (5, 6, 7, 9, 11, 12) | (1, 5, 6, 7, 8, 12) | (4, 5, 6, 7, 10, 11) | (4, 5, 6, 10, 11, 12) |

| HF-UCI | DT | KN | SVM | NB |

| FS size 3 | (5, 8, 11) | (5, 8, 9) | (4, 5, 12) | (1, 5, 12) |

| FS size 4 | (4, 5, 8, 11) | (2, 5, 8, 9) | (1, 5, 8, 10) | (2, 3, 5, 12) |

| FS size 5 | (2, 4, 5, 8, 11) | (2, 5, 8, 9, 11) | (1, 5, 7, 8, 10) | (2, 5, 8, 10, 12) |

| FS size 6 | (1, 3, 4, 5, 8, 11) | (2, 3, 5, 7, 8, 9) | (1, 5, 7, 8, 10, 11) | (1, 2, 5, 8, 9, 12) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).